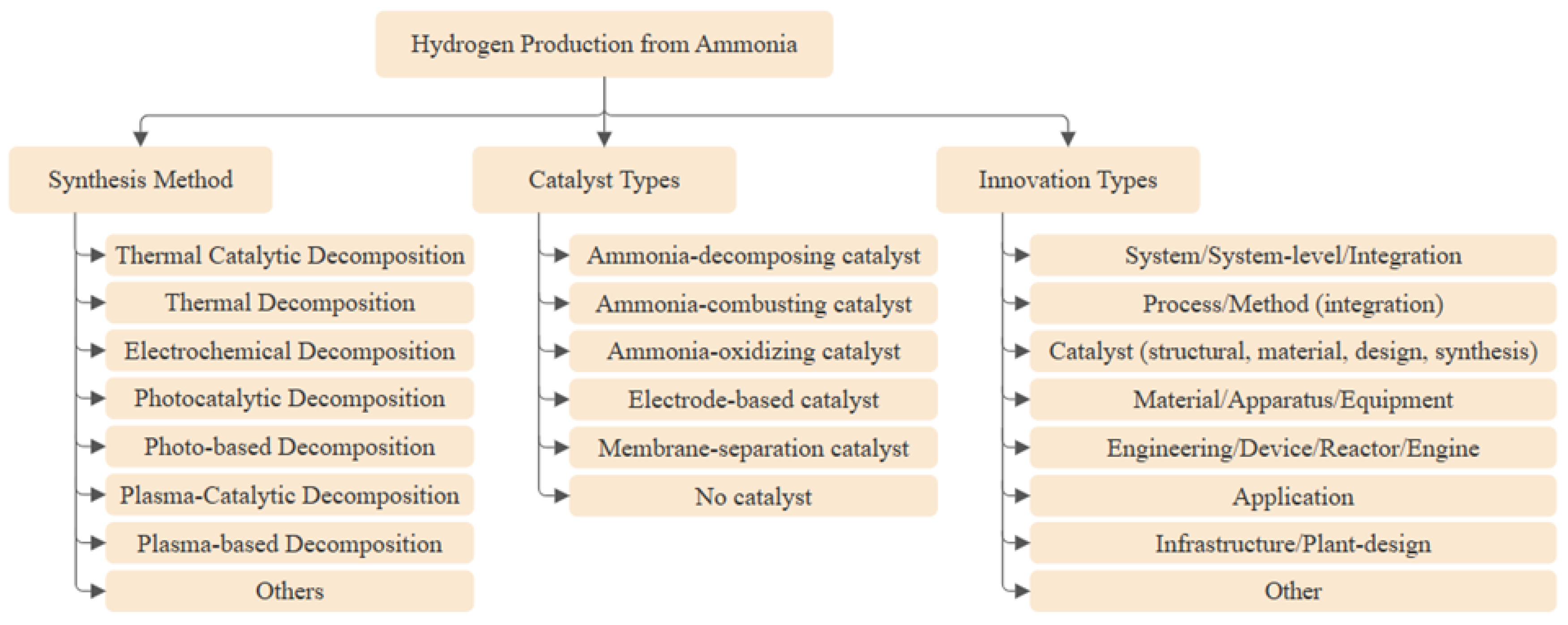

The technology updates from selected patents on hydrogen production from ammonia were organized by synthesis pathway: thermal, thermal-catalytic, plasma-based, plasma-catalytic, electrochemical, and photocatalytic, as well as a set of unique routes (e.g., photo-driven, mechanochemical ammonolysis, and chemical-chain methods). The analysis identifies key inventions, and process advances to illuminate technological progress.

4.2.1. Thermal Catalytic Decomposition

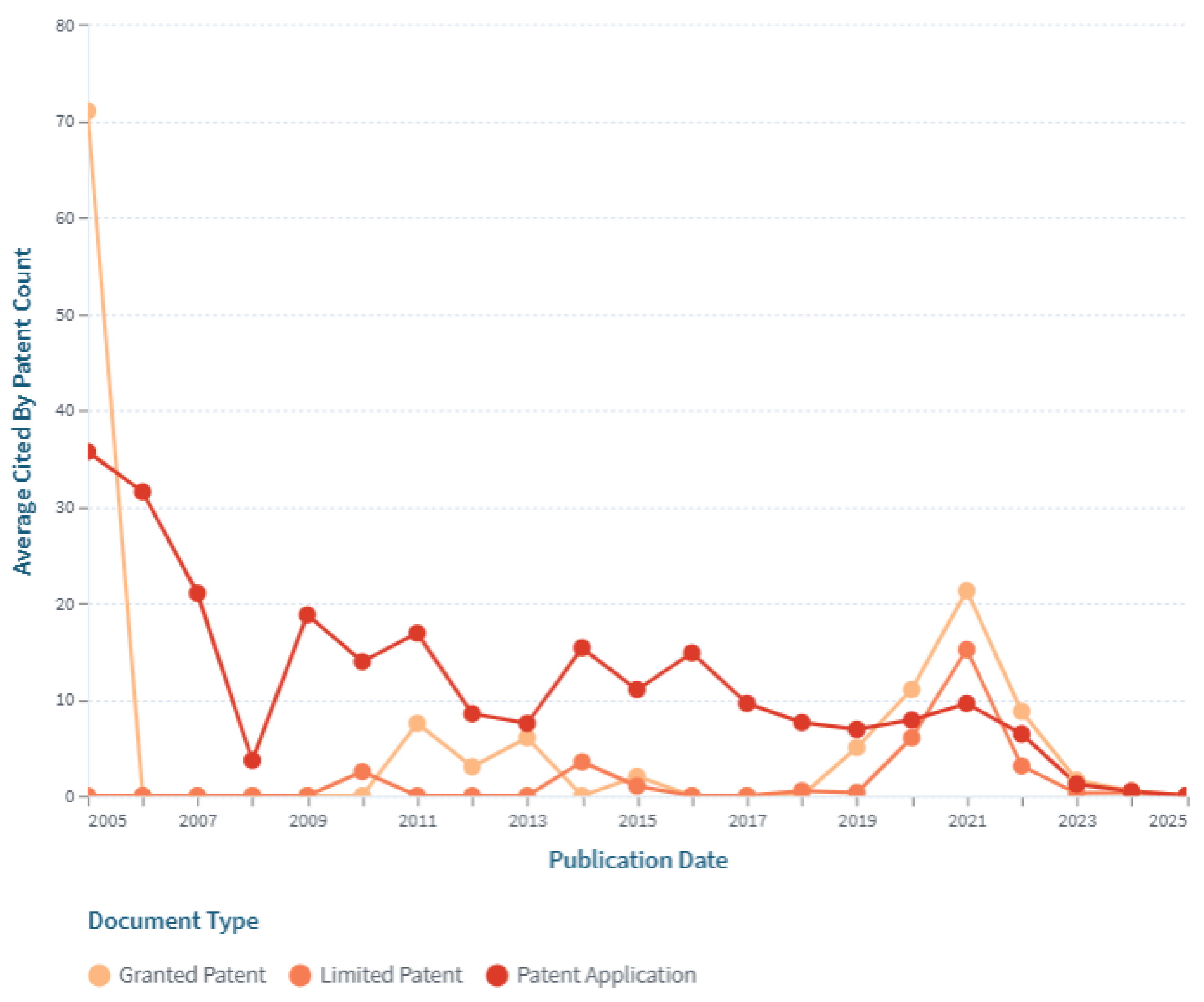

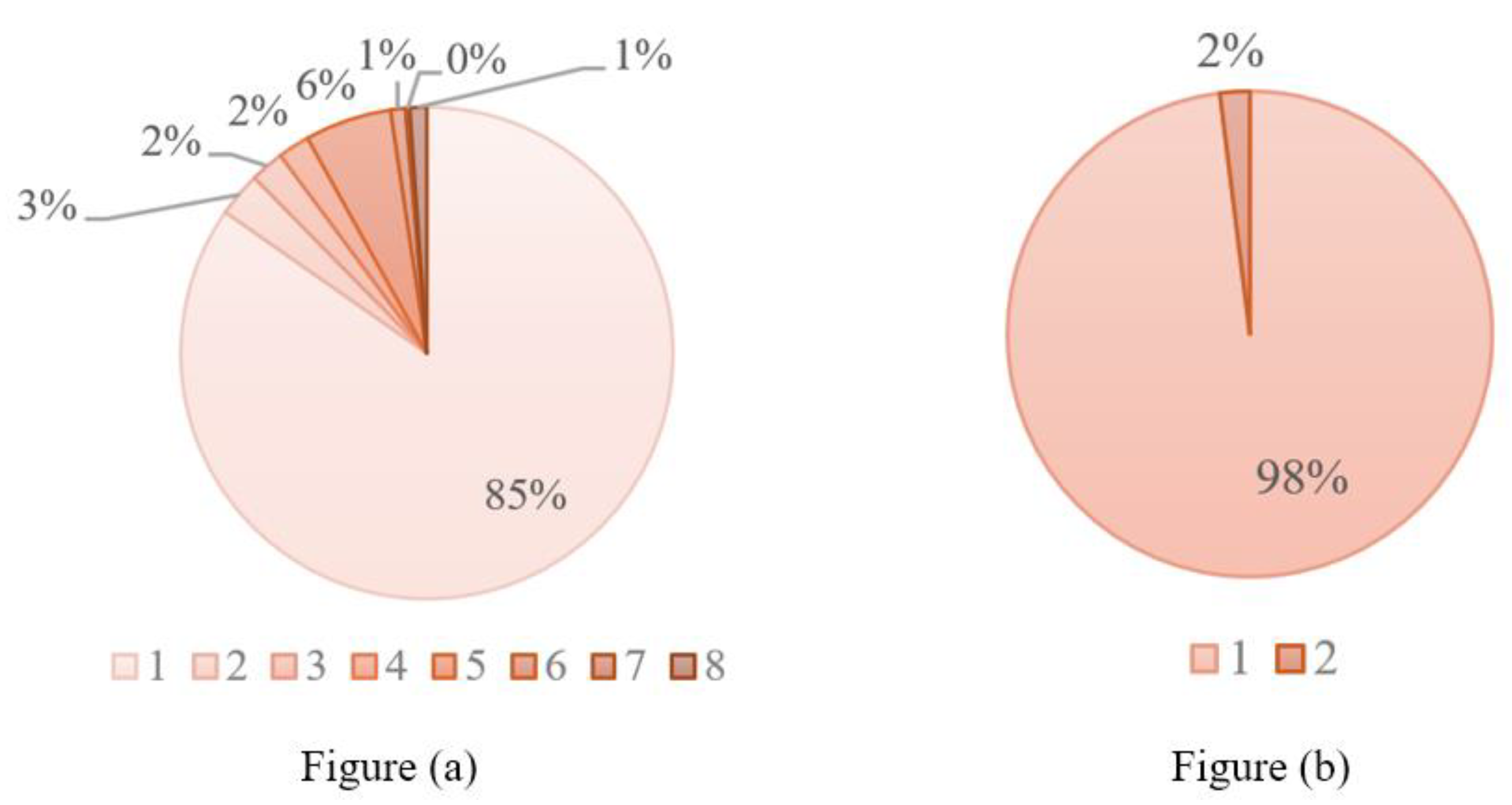

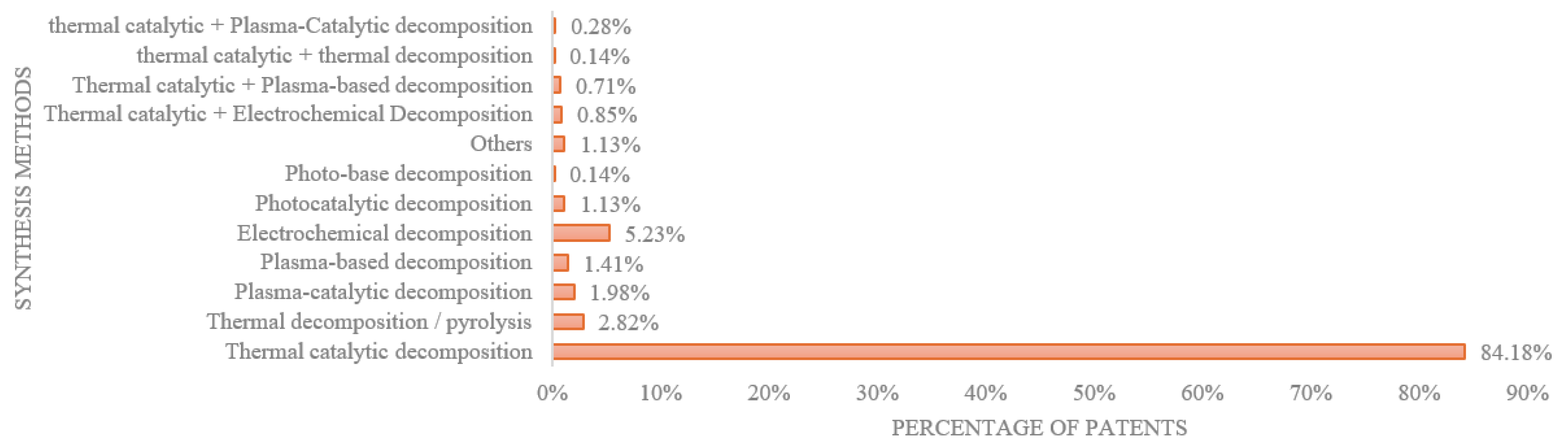

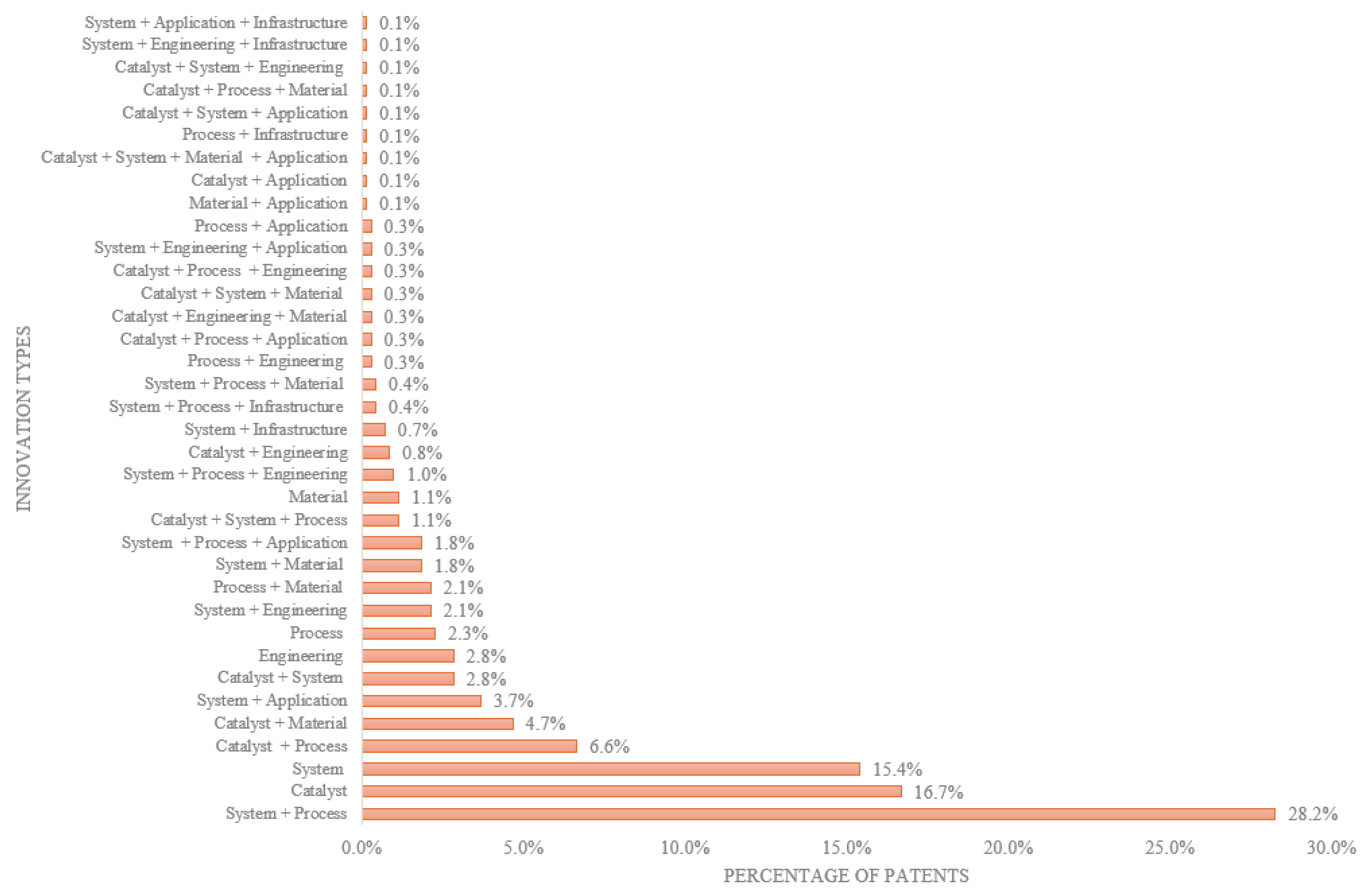

This method found that 84.1% of the patents chosen are for thermal catalytic decomposition. The oldest patent is from 2005 and the newest is from 2025. The first patent for this method, US6936363B2, was filed in January 2003 and has 70 forward citations and seven references to previous patents. In August 2005, it got its first granted patent. A small hydrogen-generation system makes H₂ by speeding up the breaking up of warmed ammonia (NH₃) from liquid or degassed water storage. At 500 to 750 °C, alumina pellets that have been treated with Ni, Ru, or Pt catalysts are used. An electric heater or a catalytic or lean-gas burner that runs on fuel-cell anode off-gas provides heat. The polymer-electrolyte fuel cells need to be cleaned up after they are used, but alkaline fuel cells can use the hydrogen–nitrogen mix [

27].

On the other hand, The US12442324B1 patents, on the other hand, use the ammonia cracker as part of the vehicle’s thermal system for internal combustion engines. A high-surface-area Inconel® 625 heat-exchange catalyst is activated by the heat from the engine’s exhaust. This catalyst can be 3D-printed as a TPMS lattice or tube-bundle core. A secondary electrically heated catalyst downstream makes sure that hydrogen is made when the engine is cold-started or under low load. Electronic control handles temperature, pressure, and expansion. It coordinates plate heat exchangers and valves to send a controlled H₂/N₂ mixture, with optional NH₃ co-feeding, to hydrogen and ammonia fuel rails and injectors without using fossil fuel promoters. The technology makes hydrogen and uses ammonia as a heat-transfer fluid on the cool side. Radiator bypass channels and active grille louvers help with thermal management, making it possible to make the radiator smaller or remove it to improve aerodynamics. This new design is a vehicle-integrated ammonia-to-hydrogen combustion and thermal-management system for spark- and compression-ignition engines. The old design had an externally heated ammonia cracker for fuel-cell applications [

28].

JP2005145748A is the second most cited patent (49) and the second earliest patent filed, in November 2003. This patent shows a hydrogen generator for vehicles that use liquid ammonia as a hydrogen carrier for fuel cells. Liquid NH₃ is stored, turned into gas, preheated with heat from the reactor, and broken down over a cheap Ni/Al₂O₃ catalyst at 800–900 °C. The system can provide hydrogen for a 102 kW PEFC while keeping the residual NH₃ in the reformate below ~300 ppm. It has about 10 L of catalyst and a space velocity of ~3000 h⁻¹. A water-based ammonia remover then takes up most of the NH₃ that is left, bringing its concentration down to a few ppm, which is safe for PEFC operation. The design also captures heat, re-evaporates NH₃ that has been absorbed so it can be sent back to the storage tank, and uses the water from the fuel cell product again. Overall, this is a thermally heated, catalytic NH₃ cracker with built-in NH₃ scrubbing and recycling that is designed to provide low-ammonia hydrogen to automotive PEFCs [

29].

The patent CN201395510Y was filed in March 2009. It was granted in February 2010. This is the third oldest patent. This patent is for a big hydrogen-rich gas generator that uses catalytic ammonia decomposition in long alloy reaction tubes that are heated by burning natural gas or LPG. This makes the heat flow faster than electric heaters. Adding ammonia to steam makes the reaction go faster and makes cracking work better. The gas mix is about 75% H₂ and 25% N₂, and it flows at rates of more than 1 × 10⁵ Nm³/h and pressures of up to 2.0 MPa. The system has a two-step heat exchange and a loop for washing and soaking up demineralized water to get rid of more NH₃. This keeps the NH₃ level below 1 × 10⁻⁵ v/v and sends ammonia back into the circulation system. The heat that is wasted from the cracking furnace is used to make more steam. This makes the whole system work better when it comes to heat. All of these parts work together to make a good ammonia cracking system that burns the ammonia to heat it up and has good heat integration and purification. This system can always make very pure mixtures of hydrogen and nitrogen gas, which are used to break down industrial catalysts [

30].

CN201512408U is the 4th earliest filing, filed in June 2009 and granted in June 2010. They relate to a small ammonia cracking furnace heated by combustion, which may be used for the supply of hydrogen in catalyst reduction on factory scales. Ammonia in liquid form is pumped to an evaporation heat-exchange vessel/vaporized/ and then introduced into a vertical reaction tube containing a nickel catalyst for thermal decomposition of the ammonia. A diesel- or natural-gas-fired burner located at the bottom of the reactor generates elevated temperatures necessary for catalytic NH₃ decomposition (2NH₃ → 3H₂ + N₂). The unit has a double-layered evaporator that extracts heat from cracked gas to preheat incoming ammonia to enhance thermal efficiency. A thermocouple is attached to control the temperature, and a simple outlet tube leads away the hydrogen–nitrogen mixture formed. The system has a small start-up cost and does not require storing hydrogen or supplying it from externally, being safe and low-cost for generating hydrogen in the field. All in all, it is an easily constructed, applied ammonia cracker based on a common Ni catalyst and designed for ruggedness [

31].

KR102247199B1 is the third most cited by patent (40) applied for in December 2020. This patent discloses a non-site, modular technology for high-purity hydrogen generation through the traditional thermal catalytic decomposition of ammonia and subsequent PSA purification. The liquid ammonia is pumped, waste-heat-vaporized, and preheated to 300–500 °C prior to being fed into a packed-bed reformer equipped with supported metal catalysts (Ru, Pt, Pd, Rh, Ir, or Ni/Co/Fe/Cu/W/Mo oxides). Ammonia is then decomposed at a temperature of 500–700 °C, producing hydrogen and nitrogen, the product being cooled and fed to TSA or PSA towers containing zeolite or activated charcoal to eliminate any remaining ammonia down to 1 ppm. A succeeding PSA or VPSA stage discharges nitrogen and yields, at 70–90% of the theoretical yield, hydrogen with a purity higher than 99.999%. Extensive heat integration, including reformer exhaust for vaporization and preheating of ammonia, and regeneration of adsorbents, contributes to a low external energy requirement. The system is constructed as compact box-type modules that can be conveniently installed and scaled up for the production of high-purity hydrogen [

32].

The most referenced patent (375 references) applied in 2022 is US11795055B1. The present invention is, in general, related to a burner-heated ammonia cracker with an integrated fuel cell for low/medium H2 demand. Liquid or gas NH 3 (<2bar) is then fed to a thermal catalytic cracker (500–750 °C) where it can be cracked to H₂/N₂, which can be directly introduced into an alkaline fuel cell; in case of PEM, just a simple polishing step (Pd membrane/activated carbon) has been considered after the cracker in order to Ds remove NH₃ from the feed. Crucial to the system is an energy cycle; some of the fuel-cell H2 off-gas is combusted in a catalytic/lean-gas burner, and used for endothermic cracking heat generation, enabling fast start-up and low specific weight per kW. Besides the catalysts, two reactor geometries (stackable plate-type cracker and tubular cracker) are suggested by the patents for efficient heat transfer at a 500–650 °C temperature level. The burner position, along with the use of ammonia preheating to stabilize the catalyst bed properly [

33].

The 2nd most cited patent (119) applied in September 2020 and granted in February 2025 is US12227414B2. The invention discloses a small, electrically heated reactor for cracking ammonia into hydrogen as needed. Traditional Ru/Fe/Co ammonia-decomposing catalysts are supported on a conductive metallic monolith (e.g., FeCrAl) with a ceramic wash coat (Al₂O₃, ZrO₂, MgAl₂O₃, CaAl₂O₃), and by direct Joule heating can be brought rapidly to ~300–700 °C and optionally up to 1300 °C without the need for a fired furnace. The reactor is characterized by close thermal coupling, a pressure shell with an interspace, an optional design of the bayonet heat recovery, and power-controlled temperature regulation. Through modulation of the electrical input and flow rate, the system can rapidly switch between different operating conditions, providing flexibility to decentralized NH₃-to-H₂ conversion. It forms, in combination with PSA/TSA or membrane purification and fuel cells or gas engines, a flexible, highly effective thermal catalytic cracker as an alternative to the electrochemical unit [

34].

WO2007/119262A2 has the broadest territorial coverage in terms of the number of all possible jurisdictions: 13 (Japan, Eurasian Patent Organization, Canada, Mexico, Australia, United States, European Patent Office, South Korea, Italy, China, Brazil, Israel, WIPO. This patent describes a self-contained ammonia-to-hydrogen supply for the alkaline fuel cells. Liquid NH₃ (≈10 bar) is split into three cascaded steps: two electrically heated thermocatalytic reactors (MA alloy body first, CoO/Cr₂O₃ ring stack second, 500–750 °C) carry out the main part of NH₃ decomposition, and a microwave waveguide with hot high-potential alloy wires completes dissociation of remaining NH₃ by EM resonance. The trace amount of NH₃ is then removed by a wet absorption scrubber so that the H₂/N₂ stream is hydrocarbon-free and low on ammonia, which makes it suitable for alkali fuel cell vehicle application [

35].

US2025/0121344A1 (filed December 2024) has the most extended families of those with jurisdictions in Saudi Arabia, Eurasia, the United States, Europe, China, and WIPO (45). An electrically (Joule) heated structured catalyst for endothermic reactions such as the NH₃ cracking to H₂ is described by this patent. As heater and carrier, a 3D-printed or extruded conductive monolith is selected; this is coated with an insulating wash coat of ceramic onto which conventional NH₃-decomposition catalysts (Fe, FeCo, Ru/Al₂O₃) are deposited. As heating is internal and very near to the active phase, the reactor can be rapidly started up for uniform operation at 400–700 °C, and then fabricated into a small, high-pressure (2–200 bar) device, thus meeting the decentralized applications of H₂-from-NH₃. And so, instead of a new catalytic material, the innovation is system/reactor integration [

36].

US10753276B2 tied for the second highest number of extended families (17*) among its 9 distinct office jurisdictions, CA, KR, US, AU, GB, JP, INPCOSG, and WIPO. The system of a gas turbine based on a UJSP generally includes a power generator driven by such a turbine. The structure comprises a first ammonia-cracking chamber and a second ammonia-cracking chamber filled with noble-metal catalysts [e.g., Ru, Rh, Pt, Pd], where the ammonia is thermally decomposed into hydrogen-rich gas. This internal hydrogen source stabilizes and intensifies the burning of ammonia in two stages of a combustion chamber. The first chamber carries out primary combustion and turbine driving, and the second operates at a higher equivalence ratio to form NH₂⁻ species for the NOx reaction to minimize emissions. The turbine exhaust heat rejected, which would otherwise be wasted, is carried through the cracker chambers (16) to keep the catalyst at a high temperature without any other outside heat source, and may also be employed as process steam in an independent expander (37) to produce additional power. Thus, the invention is a highly-efficient ammonia-fired power system with integrated capabilities that utilizes catalytic ammonia-cracking for clean combustion and NOx reduction, as well as for maximizing heat recovery [

37].

CA2883503A1, filed August 2013, which is the third highest number of extended families (15) and family jurisdiction of 7: Europe/Korea/US/CN/JP/WIPO/CA. A high-performance ammonia-decomposition catalyst employing dormerite type support (C12A7), whether hostile electrons or a hydrogen negative ions system, is provided by this invention. Reactive transition metals, including Ru, Ni, and Co, are highly dispersed over this support and can perform the NH₃ conversion more effectively at temperatures of ~350–600 °C (at higher space velocity) than typical Ru/Al₂O₃ or Ru/CaO. Electrons or hydride species are accommodated in the mayenite cages that, when occupying its active site, can modulate the behaviour of the active metal and facilitate ammonia decomposition to achieve effective CO/CO₂-free H₂ + N₂ production across a broad range of NH₃ concentrations. As the support is abundant, nontoxic Ca–Al–O oxide, the catalyst possesses high activity with approaching lower cost and better resource efficiency for NH 3 hydrogen production [

38].

CN120155131A is a 2nd recent invention and was applied by the University of Shanghai Jiaotong in Mar. 2025. A type of small-sized, high-efficiency self-heating ammonia decomposition reactor, which combines burning, heat recovery, and catalysis cracking system by a three-level nested structure, is disclosed. As an internal heat source, ammonia-hydrogen co-combustion is employed, with which the problem of ammonia’s poor ignitability is resolved, and the requirement for external furnaces is removed. Hot exhaust gases from the reaction zone are recirculated around the reaction layer, allowing heat to be used more efficiently and maintaining a high reactor temperature, which results in energy savings. Ammonia is fed into the catalytic reaction layer (Q) (catalytic filled with); a Ru-based granular catalyst that can be converted, at 450° C, by more than 99%, and travels upward through spiral flaps that enhance mixing (mixing), residence time (residence period of time), and decomposition completeness (decomposition entirety). With a hydrogen productivity of 50 Nm³·(m³·h)⁻¹, the reactor design may find application for mobile or decentralized ammonia-to-hydrogen processes like onboard marine engines and refueling stations. In general, the present patent discloses a system-level innovation of autothermal ammonia cracking, showing relatively more compactness and improved combustion stability with a high heat recovery focus rather than a novel catalyst material [

39].

At the same time as the application of CN120155131A by the same applicants, patent CN119951503A discloses a low-Ru, low-temperature, and high-activity Ru-based catalyst for thermal catalytic ammonia decomposition to hydrogen based on a core-shell Ru/CeOx@N-doped porous carbon structure. A Ce-based metal-organic framework (Ce-BTC) is initially prepared via a hydrothermal method from Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, H₃BTC, and PVP in the mixed solvent of ethanol/DMF and further transformed by argon calcination into a CeOx@porous carbon composite with a large surface area and adjustable porosity. The Ru precursors (Ru₃(CO)₁₂, Ru(NO)(NO₃)₃, Ru(acac) 3 or RuCl₃) are first deposited by impregnation (3 wt % Ru compared to the calcined support), and then heat-treated under Ar (300 °C then 550 °C); highly dispersed sub-nanometric sized of active nanoparticulates are obtained, which are confined in a carved cavern CeOx@N-doped porous carbon. The catalyst particles that are obtained (40–60 mesh) are then screened for the NH₃ decomposition in a quartz-tube, fixed-bed flow reactor under NH₃ flow (GHSV ≈ 2000 mL·h⁻¹·g_cat⁻¹). Detailed studies reveal that Ru₃(CO)₁₂/CeOx@PCN exhibits the highest activity and selectivity, with approximately 80–88% of NH₃ conversion at 350 °C and >98% of NH₃ conversion recorded after reaction at 400 °C, benefiting from improved intrinsic activity, outperforming both conventional Ru/oxide or Ru/carbon catalysts in terms of stability and reducing Ru consumption. The improved reaction rate is proposed to stem from the synergistic interaction between CeOx (containing oxygen vacancies and variable valence state Ce³⁺/Ce⁴⁺), N-doped porous carbon shell, and Ru electronic structure modifications, therefore suggesting a promising MOF-derived, low-Ru-content catalyst strategy for NH3-based efficient LT H2 production [

40].

CN120268340A is the most recent invention applied for in June 2025, by Hebei Academy of Sciences, Institute of Energy, and Shijiazhuang Tiedao University. This patent relates to an integrated ammonia-cracking hydrogen generation apparatus in which the cryogenic energy of liquid ammonia is effectively utilized to improve the overall process heat efficiency. Ammonia vaporization, catalytic cracking, hydrogen purification, compression, and storage, scaled down to refueling, are integrated into one single unit. Ammonia is then decomposed into hydrogen and nitrogen by thermal dissociation, and the gas is purified and compressed in a multistage process with recovered cold integrated as an intercooler to go through a near-isothermal compression process with lower power demands. This system, charged by the off-peak electricity, can store hydrogen and cold energy, which would be utilized for a BF-natural gas mixture during refueling in higher temperatures of daytime. It enhanced performance efficiency, safety, stability, and economic feasibility at the same time. On the whole, it is a system-level innovation that focuses on multistage energy recycling and integrated operation rather than catalyst development [

41].

CN223127277U was submitted in Sep 2024, and the 3rd most recent patent (July 2025). It reveals a type of integrated coupled dual-source hydrogen production system by combining alkaline water electrolysis with ammonia catalytic decomposition. Alkaline electrolyte from electrolysis is recycled in an ammonia distillation column, where it decomposes readily, volatilizing ammonia over Ni or Ru catalysts to form H2 and N2. Hydrogen coming from both electrolysis and decomposition is purified (adsorption) and mixed in order to be utilized downstream. The system is hybrid at the level of system/integration and not at the conventional catalytic cracking (like ammonia decomposition in a usual reactor), since it combines electrochemical with thermal catalytic hydrogen production [

42].

GB2633197A is the second latest granted patent (Oct 2025). An additional system-level innovation in industrial ammonia cracking is also offered for patenting, where two reactors are employed- a primary furnace-heated catalytic cracker and a secondary, smaller ammonia cracker. The secondary reactor makes a hydrogen-rich cracked gas, which can be used to: (1) reduce oxide catalyst in the reformer during start-up; (2) provide a hydrocarbon rich fuel stream for lighting the burners if ammonia alone will not sustain flame formation; (3) suppress nitriding by having a lower partial pressure of ammonia entering and remaining on surfaces in the reformer tubes; and/or during continual operation. The primary reactor uses standard Ni- or Ru-based NH3 decomposing catalysts, in furnace-heated tubes such as those used for steam reforming. The secondary reactor may be adiabatic, electric, or gas-fired, allowing separated synthesis of cracked gas when the main plant is operating below full scale. Other possible attributes are PSA hydrogen purification, tail add gas recycle as fuel, and double feed (fresh vs pre-cracked ammonia). In conclusion, the system has the reduced risk of operation at start-up, the ability to more effectively activate the catalyst, an extended operating range, and enhanced process efficiency for large-scale production of hydrogen from ammonia [

43].

The latest patent is CN117509537A (October 2025). The present invention relates to a method for dissociating NH₃ at low temperatures by the use of electric energy. This is an improvement over conventional thermal catalytic cracking, which occurs only during temperatures above 400 degrees Celsius. (1) Synthesizing the Ni/Co/Fe–CeₓZr₁₋ₓO₂catalyst through solution combustion and activating its low temperature performance using an indirect electric field can convert a considerable amount of NH3 at temperatures less than 250-300 °C without requiring external heat sources. When the new process described here uses very stable electric fields, a little nano-SiC (a few %) is used as an assistant material. When an electric field is applied at 250 °C, some of the catalysts convert with a rate of 50–60%, which contrasts markedly with thermal-only conversion efficiencies (less than 10%). Based on the design, the ammonia cracking could be substantially enhanced by the electric field, even at low pressures. The little bit that it might be useful is if one has a small hydrogen plant of 3-10 Nm/h, which should be expanded in the future when heating with natural heating no longer works (i.e., too hard to reach the temperature)[

44].

The first and only patent is CN120325293A, which was filed in March 2025. This report presents a novel series of Pd–transition-metal core–shell nanocatalysts (Pd@M, where M = Co, Fe, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, and Mn) that facilitate low-temperature continuous hydrogen production through the oxidative dehydrogenation of ammonia. Microwave-assisted microemulsion–gas-induced synthesis is used, and Pd as the core is strengthened by a uniform transition-metal shell that makes it more stable, better at transferring hydrogen, and less likely to oxidize. When reduced, catalysts are very active between 75 and 300 °C (the actual bed temperature is 90 and 350 °C), with Pd₀.₇Co₀.₃ at ~90 °C beating those of Pd-only or single-metal controls. The core-shell structure makes it possible to convert NH₃ at low temperatures, well below the standard ≥400 °C thermolysis. This is a step forward for the O₂-promoted route of NH₃ decomposition. Ammonia will be a promising way to make hydrogen on a large scale at low temperatures because it only uses cheap commercial precursors and is easy to make [

45].

The earliest invention, most cited patent (107), and highest number of extended families (19) is US7875089B2, which was filed in 2004. Its nine family jurisdictions cover the US, Japan, Europe, Korea, Australia, China, Mexico, and WIPO. This patent describes a small, portable NH₃→H₂ generator for small fuel cells. It uses thermal catalytic ammonia cracking in a micro-channel/finned reactor that runs at a moderate temperature (about 550–650 °C). This means it can be made of stainless steel or titanium and doesn’t need high-temperature alloys. A small burner (butane) makes most of the heat, but there are also options for electric or autothermal NH₃ heating. The unit adds a small, acid-impregnated carbon adsorber that is cooled by the incoming liquid NH₃. This is because lower-temperature cracking lets some NH₃ slip through. As a result, the outlet H₂/N₂ is fuel-cell grade (<1 ppm NH₃). Ammonia-decomposing catalysts (Ru/Al₂O₃ or Ni) are used, and the new idea is to combine systems and reactors to make portable fuel cell power [

46].

The most cited by patent (58) is WO2011/107279A1, which was filed in March 2011. A small, heat-integrated ammonia cracking system that uses solid ammonia storage (metal ammine salts) to make hydrogen for fuel cells that work at low temperatures. The solid cartridge gives off ammonia, which is then broken down by heat in a “jacket-cracker” reactor. The inner chamber (Pt/Al₂O₃) burns NH₃ or recycled H₂ to make heat, and the outer chamber (Ru/Al₂O₃) breaks down NH₃ into H₂ and N₂. A heat-recovery jacket warms up the ammonia feed and sends extra heat back to the storage module. This makes the system work better. PEM fuel cells need an NH₃ absorber to clean up the gas stream, and dual-cartridge reactor modules let them run all the time. The new technology is not about new catalyst materials; it’s about combining reactors and controlling heat. This makes it possible to safely and efficiently get hydrogen from solid ammonia [

47].

CN111957270A, which was filed in September 2020, is the second most cited by patent (47). This patent describes a whole system for making hydrogen by breaking down ammonia. It is supposed to be used at hydrogen refueling stations. The system uses old-fashioned catalysts made of Ni, Fe, or Ru to break down ammonia by heat. This makes a mixture of hydrogen and nitrogen that is cleaned up in three steps: ammonia adsorption, pressure-swing adsorption (PSA), and membrane separation. One of the most important new features is that it can run on its own. A catalytic combustion unit uses some of the product gas to make all the heat needed for ammonia cracking. It doesn’t need any outside fuel. The patent also makes the process use less energy by using a two-stage heat exchange process in which hot combustion exhaust heats up the ammonia feed that is coming in and regenerates the ammonia adsorption bed. The hydrogen that has been cleaned is stored in tanks that can handle both low and high pressures. This lets you fill up with hydrogen at pressures between 350 and 700 bar. Most of the patent is about integrating systems at the system level. It uses regular catalysts to make hydrogen production more efficient, improve heat recovery, and make it easier to use at refueling stations. This makes it a good design guide for making hydrogen in a decentralized way using ammonia [

48].

The most recent invention to be filed is CN119015872A. There is a small ammonia-to-hydrogen system that uses catalytic combustion heating to break down ammonia. It has a dual-zone catalytic burner (Pd/Pt for ignition, Cu/Ni for sustained combustion), a heat exchanger, and a Fe-based ammonia-cracking reactor. After startup, the system heats itself and doesn’t need any fuel because some of the hydrogen it makes is used as burner fuel. The countercurrent heat exchange makes the system more thermally efficient, and the waste heat recovery warms up the ammonia that is coming in. It runs at about 550 °C and converts about 99% of ammonia. Its lightweight, efficient, and easy-to-monitor design makes it good for hydrogen generation on-site or on the go [

49].

JP2010180098A was the first patent filed in February 2009 and has been cited the most (5). This patent describes a hybrid autothermal ammonia-to-hydrogen generator that uses carbon nanotubes to combine partial oxidation and catalytic decomposition. The CNTs have different areas for Pt oxidation and Ru/Rh/Ni/Fe decomposition catalysts, which makes it possible for H₂ to be produced without any external assistance. The design eliminates the need for external heating and enhances system efficiency by utilizing nanoscale thermal conduction. This example of autothermal thermal catalytic ammonia decomposition using bifunctional nanostructured catalysts is meant for use in automotive fuel cells or ammonia engines [

50].

In November 2009, WO2010/058807A1 was filed. It has the most extended families (10), with family jurisdictions in Japan, China, Europe, the United States, and WIPO. It has the most forward citations (15). This patent suggests an ammonia engine system where a Pt-based ammonia-oxidizing unit is put between the engine and the ammonia cracker to raise the exhaust temperature when the engine is running at a low load. The exhaust gets hotter and then goes into a plate-type ammonia cracker (Ru/Rh/Ni/Fe) that breaks down NH₃ into H₂ and N₂. This means that hydrogen is always available, even when the engine exhaust is too cold. This is a system-level, hybrid thermal-catalytic NH₃-to-H₂ architecture for an ammonia engine. It uses exhaust to heat the engine, oxidation to help it, and optional electric heaters to help it [

51].

KR20240010242A is the most recent application filed in July 2022 by Hydrochem Inc. The present invention provides a process for the production of high-purity hydrogen from ammonia employing dual-step selective oxidation. Ammonia is initially thermocatalytically decomposed (500–650 °C) over Ru, Co, Ni or Mo containing catalysts. Residual NH₃ in the product stream is next a) selectively oxidized at 300–650 °C over an Fe- or Cu–zeolite catalyst to form N2 + H₂O (≫95% selectivity, while NOx production <150 ppm). Stable full-scale NH₃ removal is cost-effectively achieved in concurrent operation with controlled O₂ injection and without power-consuming adsorbers while supply of NH₃ (1–3× stoichiometry) was required. The sequence may include a TSA/PSA clean-up for ultra-pure hydrogen (<1ppb NH₃). In contrast to typical adsorption–desorption cycling, this strategy can minimize energy loss and may therefore offer an alternative way to achieve efficient low-emissions ammonia-based hydrogen production and purification [

52].

JP2011204418A is filed in March 2010. This invention is about SOFCs that run on ammonia but have a problem starting up: when they shut down, the Ni/ceria/zirconia anode oxidizes and can’t break down NH₃, so NH₃/NOₓ could get out. The patent adds a step before the main process where a hot, H2-rich reformate is sent to the anode to (1) heat it up to the right temperature and (2) reduce it back to its metallic, NH3-decomposing state. The anode exhaust is burned at the same time, and the hot gas is sent to the air side. This keeps the anode and cathode from getting too hot and causing thermal stress. After that, the system switches to ammonia and recycles anode exhaust to get rid of any leftover NH₃. This keeps NH₃ in the vent at ≤ 5 ppm and makes the stack last longer [

53].

The most recent one is CN120332944A in March 2025. A STE-H2 refueling station of an ammonia-decomposition-integrated type (solar hydrogen pilot system) and high-temperature SOEC water electrolysis are detailed. Through solar panels, a steam turbine and molten salt storage system, the SOEC can be fed from with high quality heat and power. The hot SOEC/anode/burner gases are then passed through a reactor, in which the heating-gas line is thermally connected to a catalytic NH₃-decomposition line including an ammonia-decomposition catalyst. The cracked gas is cooled, passed through one to two adsorptions stages for the removal of any unconverted NH₃ and N₂, followed by compressing, cooling and dispensing. The overall energy-use efficiency of the system is enhanced, and the capability to refuel even when the sun is not shining is maintained by allowing solar heat BN exhaust, SOEC waste heat, and NH₃ cracking to share a single temperature ladder [

54].

WO2008/002593A2 is the first filed invention in 2007, with the highest number of extended families (10). For this family, jurisdiction was found in between the European Patent Office (EPO), Japan, Canada, Australia, the United States of America (USA), China, and WIPO. Disclosed is a system of a hydrogen fueling station constructed to produce hydrogen at point-of-use by autothermal catalytic cracking of ammonia using Ni-, Ru- or Pt-based catalysts between 500 and 800 °C wherein liquid NH₃ is stored, vapourized and decomposed in the presence of the catalyst, undissociated NH₃ being removed by cryogenic, adsorptive or membrane separation, filtered through appropriate filters so as not to clog said storage tank outlet valve and sent back to said storage tank for later use. The clean hydrogen is compressed and provided for use as a vehicle fuel. The novelty of this work is combining ammonia storage, catalytic cracking, purification, and compression at a fueling station to produce clean auto-produced H2, so as to act in a more safety-decentralized way (and reduce the demand for transported hydrogen) [

55].

The most cited patent (5) is US10906804B2, filed in 2018 and assigned to the Gas Technology Institute and the University of South Carolina. This ARPA-E–funded patent features a membrane-integrated ammonia cracker that combines a Ru-based NH₃ decomposition catalyst, an H₂-selective ceramic hollow fiber membrane for continuous removal of the H₂ product to achieve >99% conversion at T = 350−450 °C and P =10–15 bar, and in-situ catalytic burner using H₂ as fuel to provide heat for endothermic process. The small reactor supplies PEM-grade, high-purity H₂ (30bar) at ≈88% efficiency and

$4 kg⁻¹ cost, representing a thermal catalytic, membrane-assisted breakthrough at the systems level for distributed H₂ generation [

56].

US2020/0269208A1, filed 2020, has the highest citation by patent (23). The invention also provides a low-temperature catalytic membrane reactor for the simultaneous decomposition of ammonia and purification of hydrogen streams. The reactor consists of a porous yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) tube with a Ru catalyst loaded on its exterior mesoporous layer, and selective H2 permeation through a thin Pd membrane. In this study, internal surface cesium doping improves the N–N desorption that facilitates effective NH₃ cracking at ~ 400 °C and 1–5 bar flow rates without a sweep gas. It permits the full conversion of NH₃ (10× less catalyst use) and >30 mol m⁻³ s⁻¹ H₂ productivities with superior H₂ purity for PEM fuel cells. It is an exemplar of a novel thermal catalytic, membrane-assisted concept for ammonia-derived H2 production with compactness and high efficiency [

57].

CN113604813A is the most recent patent to be filed in August 2021 and has been cited by 17 patents. It discloses an integrated NH₃-to-H₂ compact system, including NH₃ vaporization, high-temperature electric/combustion-assisted decomposition, and a low-temperature gases purifying function in a single vessel. Liquid ammonia is gasified and decomposed at >800 °C by the Ni–Cr electric heater, and then a H₂-combustion tube with a catalyst helps to provide additional heat. The resultant mixed gases are then conducted through a Z-shaped Pd/molecular-sieve separator, cooled by a closed hot–cold circulation loop as depicted in Figure 53, and released into high-purity hydrogen and nitrogen tanks. The patent is related to thermal design as well as the integration of the purification efficiency, and is not focused on a new NH3 - cracking catalyst [

58].

That most-cited-by-patent (52) was invented by Goetsch, Duane A., and Schmit, Steve J. in 2004. US2005/0037244A1 describes an autothermal process for cracking ammonia, where a small amount of the product hydrogen is burned - sometimes with a little fuel and/or ammonia - within or adjacent to the reactor to provide endothermic heat. This avoids the necessity for external furnaces, and small, short-contact-time units (GHSV ≈3 × 10⁴–10⁶ h⁻¹) are able to operate in the range of 700–1000 °C. The patent presents three heat-integrated schemes: a mono-chamber configuration with radiative shields, a dual-compartment unit that heats up an inner cracker through a wall-containing outer combustor, and a coaxial two-pass reactor that warms up the feed by hot effluent. Catalysts Ru, Ni, Fe, and Pt on ceramic or FeCrAl monoliths with the oxide phase stabilized γ-Al₂O₃ produce a contaminated with CO-free H₂/N₂/H₂O stream for use in fuel cells using air as the oxidant and optionally recycling hydrogen [

59].

EP4417572A1 optimizes US2005/0037244A1 by dualizing between a single Ru-based bed half-catalytic combustion and NH3 decomposition at a time, with oxygen being fed through multi-perforated in-bed distributors so that a uniform temperature is maintained throughout and the bed is operated at less than 600-800 °C (most preferably about 600-700 °C). The controlled co-feeding of canned water (0.2–1.2 kg H 2 O per kg NH 3 ) can act as a heat sink and enable operation up to 20–40 bar without equilibrium penalties. Downstream, PSA produces pressurized H₂, and an adiabatic catalytic boiler oxidizes the PSA offgas to create fuel vaporization and preheat the NH₃/H₂O feed with heat recovery. Overall, the new design delivers a small volume low-NOₓ pressurized H₂ plant with reduced O2 consumption and increased H2 yield when compared to flame-assisted Ni-based systems [

60].

US2012/0015802A1, filed in 2010, has the most extended families (23) with jurisdictions in the US, Korea, Europe, China, and WIPO, and the highest cited patent (8). An autothermal ammonia-to-hydrogen system is introduced in the present patent, in which both ammonia combustion and decomposition catalysts are simultaneously located inside a reactor. A small portion of ammonia is catalytically oxidized over Mn–Ce/Mn–La oxides to supply heat, and the decomposition of ammonia over the Fe-based material transforms into that over Co-, Ni-, or Mo-containing materials during 300–1100 °C, which is driven by the generated heat. The dual-function catalyst design (Figure 56), developed in this study, enables standalone hydrogen production without an external heating for high-performance non-precious metal catalysts with providing a significant impact on overall efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and thermal stability for portable to industrial hydrogen generation [

61].

CN117693608A is the only invention so far that has 7 families of extension with coverage from Europe, Japan, Korea, the US, China, GB, and WIPO. shows an all-solid-state membrane–reactor system for hydrogen generation from NH₃ where porous Ni–BCZY cermet electrodes thermally decompose NH3 and dense BCZY protonic-conductor membrane extracts protons, compresses H2 electrochemically, and supplies external Joule heat to sustain the endothermic reaction. Developed for efficient operation between 600 and 650 °C, the process achieves a high NH₃ conversion without downstream PSA or mechanical compressors. The primary catalyst is a Ni-based ammonia-decomposition electrode, which also functions as the proton-conducting structure. The unique contribution is a compact, self-heated reactor that combines a catalyst, an electrode, and a proton-conductive membrane for reaction, separation, compression, and heat-management in an efficient system that continuously produces high-purity pressurized hydrogen from a variety of sources: either anhydrous ammonia or traditional dilute aqueous ammonia, with improved overall performance [

62].

EP1728290B1 is the earliest patent filed in 2005 and granted in December 2008. It has family jurisdictions from 9 countries: Germany, China, Spain, the United States, Europe, Austria, Japan, Poland, and WIPO. The invention provides an integrated power-generation system that employs a metal–ammine salt as a reversible solid ammonium storage and utilizes either direct (Ammonia-fed) ammonia fuel cells or a thermal catalytic ammonia decomposition reactor for hydrogen fuel cells. Metal–ammine complexes (e.g., Mg(NH₃)₆Cl₂, Li(NH₃) ₄Cl) have been discovered, which store 20–60 wt% ammonia and release it safely at moderate temperatures, with a significantly higher volumetric density and much lower vapor pressure compared to liquid ammonia. b NH₃ is applied either as such or it’s decomposed over transition-metal catalysts (Co₃Mo₃N, Ru, Co, Ni, and Fe particles on carriers). Residual NH₃ is extracted for PEM fuel cells by acid scrubbers or MaXz absorbents, or Pd hydrogen selective membranes (NH₃ <10 ppm). The patent also shows micro-fabricated Ru or Ba-Ru/Al2O3 reactors with approximately 98% conversion at 400 °C, which will enable compact NH3-to-H2 systems for MEMS. In general, the invention provides a system-level solution that integrates high-density solid NH₃ storage, catalytic cracking, separation, and a fuel cell into a single compact power unit [

63].

EP3607182B1 has the highest number of extended families (13) covering 6 jurisdictions: Brazil, the US, Japan, Europe, China, and Korea. A vehicle-integrated NH₃-to-H₂ generation system is described in this patent, wherein ammonia is phase-separated from an NH₃/organic-solvent solution and catalytically decomposed (Ru/silica) for H₂ formation, and may be further dehydrogenated through, for example, a Pd membrane. Thus, the obtained H2 is injected into the diesel exhaust in a pulsed manner for enhancing cold-start oxidation (CO/HC/NO) and regenerating DOC catalysts, as well as ammonia injection for SCR NOx reduction [

64].

The most recent invention, US11084012B2, filed in 2020, is the highest cited by patent (27) and cited patent (9). A two-stage ammonia decomposition process is disclosed in this patent invention, utilizing Ni- and Ru-based catalysts to achieve a NH3 conversion of greater than 99.9% along with high-purity H2. Heat supply is provided by a porous burner, and recuperators and coils are used to recover heat for preheating ammonia. Further purification is achieved through optional PSA and membrane units for hydrogen, as well as off-gas heat recycling with fuel-cell integration. The arrangement provides a small-scale, low-energy, and high-purity hydrogen production process that is particularly suited for onsite or fuel cell applications [

65].

4.2.3. Electrochemical Decomposition

The oldest filing among the selected patents is JP2005327638A (May 2004), which has been forward cited by six patents. The proposed device for PEM fuel-cell systems removes and recovers trace NH₃ from hydrogen-rich reformate using water. The ammoniated water is subsequently electrolyzed between stainless-steel/Ti-plated mesh electrodes to decompose NH₃ into H₂ and N₂. The generated gases are blended back into the cleansed reformate, delivering more hydrogen while producing no new waste streams. By merging washing and electrolysis in a single tank and removing ion-exchange resins, the design minimizes footprint, capital/operating expenses, and regeneration waste. An optional solar cell can power the DC supply, substantially lowering energy use. The patent does not claim a specific catalyst or membrane; its uniqueness rests in process integration and practical system engineering, not in catalytic materials [

70].

EP4570949A1, filed in 2024, has the most cited patent (5) and extended families (3) in the highest jurisdictions: the United States, Europe, and China. This patent suggests a catalyst-free, non-thermal electrochemical reactor that produces hydrogen directly from liquid ammonia for use aboard aircraft. A cylindrical chamber with the wall acting as the anode and a central rod serving as the cathode. Liquid NH₃ is injected tangentially, creating a helical flow. An electric field converts ammonia into H₂ and nitrogenous byproducts, which escape through separate outlets. Ultrasonic transducers remove gas bubbles from electrodes, whereas permanent magnets use the Lorentz force phenomenon to increase reaction speeds. Multiple reactors can be connected in sequence within a cooling structure, with the nitrogenous outflow of one stage serving as the NH₃ feed for the next. This design provides a small, cryogen-free hydrogen source that is ideal for aircraft propulsion and other transportable applications [

71].

CN119956399A, filed in January 2025, is the most recent innovation, providing a high-temperature, electrode-based cathode catalyst for solid oxide ammonia electrolysis to generate hydrogen. The authors created a citrate-EDTA sol-gel to create a Co-doped double perovskite Sr₂Fe₁.₅₋ₓCoₓMo₀.₅O₆ (x = 0-0.3). During electrolysis in a reducing atmosphere, the material self-reconstructs into a layered perovskite, Sr₃Fe₂₋ₓ₋ᵧCoₓMoᵧO₇, and precipitates fine Co-Fe alloy particles on its surface. The reconstructed interface provides more active sites, oxygen vacancies, and better electron/ion transport, resulting in a higher ammonia-electrolysis current density than commercial LSM and LSCF cathodes at 750 °C (the best composition, Sr₂Fe₁.₃Co₀.₂Mo₀.₅O₆, reaches ≈1450 mA cm⁻² at 0.6 V vs 573-825 mA cm⁻² for LSM/LSCF). The idea is intended for SOEC/SOAE stacks that employ NH₃ as anode fuel yet require high-rate H₂ evolution at the cathode [

72].

CN116479465A, filed in May 2023, is the most cited patent (8) and describes a catalyst-level solution for room-temperature electrocatalytic breakdown of liquid ammonia/ammonium-salt mixtures. The process of manufacturing single-atom nanoparticle (SAs-NPs) composites of Ru, Rh, or Ir on carbon-nitride nanosheets using freeze-drying and high-temperature inert calcination (750-850 °C). When coated on conductive substrates and tested in 1 M NH₄PF₆ at RT (−0.3 to −1.4 V vs Ag/AgNO₃), the catalyst produces H₂ and N₂ at a H₂:N₂ ratio close to 3:1 and maintains activity for ~200 h, while also avoiding the Pt-anode corrosion/dissolution problem that limits existing RT liquid-ammonia electrolysis systems [

73].

CN119506969A is the most recent invention submitted in November 2024. It describes an improved Ru catalyst for electrochemical ammonia breakdown to hydrogen. The solution addresses the issue that Ru, while very active for NH₃ → N₂ + 3H₂, sinters under “electrothermal” conditions, resulting in decreased activity over time. The patent proposes making Ru particles from RuCl₃ and wrapping them with an organic-inorganic shell: polyimide (base), a N-acetyl amino acid (N-acetylcysteine or N-acetylglycine) as an adhesion/compatibility layer, and nano SiO₂, TiO₂, and Al₂O₃ as a high-Tm “skeleton.” After drying (70 °C) and calcining in inert gas at 450-550 °C, this shell keeps Ru in place, avoids agglomeration, and still allows for NH₃ breakdown. Electrochemical experiments (1 M KOH, 10,000 CV cycles) demonstrate lower overpotential and degradation rate than unprotected Ru, making the catalyst better suited for renewable-powered, stop-start electrochemical NH₃→H₂ systems with extended lifespan and low maintenance [

74].

WO2009/024185A1, filed in 2007, is the most highly cited patent (12). It introduces a low-temperature, on-board ammonia electrolyzer, using an anion-exchange membrane to generate a 3:1 H₂:N₂ mixture from an alkaline NH₃ solution for engine combustion enhancement. The device operates at ~0.5-0.6 V and exhibits greater than 100% Faradaic efficiency. It uses similar bifunctional Ni-based Pt/Ir/Rh-modified electrodes that invert polarity every 60-3000 seconds to self-clean and maintain continuous H₂ output. Classified as electrochemical (AEM-based) ammonia electrolysis, its novelty principally rests in the system design and operation, with secondary advances in catalysts [

75].

GB2571413A, filed in 2018, is the second-earliest invention, with the greatest 7 backward citations; it has 4 extended families with its jurisdiction from Germany. This patent offers a bio-electrochemical route for hydrogen synthesis that leverages waste-derived ammonia as a renewable feedstock. The process begins with the enzymatic conversion of urea into ammonia using urease generated from plants or bacteria, followed by ammonia stripping using alkali treatment to extract ammonia gas from cattle excreta, human sewage, and food waste. The recovered ammonia is then electrochemically degraded into hydrogen and nitrogen in an electrolyzer employing electrode-based catalysts such as thermally decomposed iridium oxide (IrO₂) for the anode and nickel-based materials for the cathode. The hydrogen created can be immediately employed in tiny fuel cells for combined heat and power generation or provided to national energy networks [

76]. Overall, the innovation presents an integrated and sustainable waste-to-hydrogen system that combines agricultural and municipal waste management with renewable hydrogen generation, decreasing environmental impact while avoiding dependency on fossil-fuel-based reforming.

KR102776600B1 was filed in October 2022, and the second latest granted in March 2025. The proposed graded ammonia-electrolysis anode is suitable for alkaline NH₃ electrolysis. The electrode stacks an ammonia-diffusion layer with a high-density PGM catalyst layer (2–8 mg cm⁻²) and a low-density PGM layer (0.5–3 mg cm⁻²) made from Pt, Ir, Ru, Pd, or their alloys. This graded structure maintains NH₃ supply channels, secures sufficient active sites, and prevents the cell from straying towards the oxygen-evolution reaction at high current density, a common failure mode of NH₃ electrolysis. In single-cell testing (1 M NH₃ + 1 M KOH, 100 mA cm⁻²), the composite electrode (1:4 low-density:high-density) maintained ≈95% of its initial H₂ production even after 30-60 min, while single-layer electrodes (only low-density or only high-density) declined to 50-60% or lower [

77].

KR20250101330A, filed in December 2023 and most recently granted in August 2025, describes a low-cost, high-efficiency method to Ni-based electrocatalysts for ammonia electrolysis. The method employs a liquid plasma reactor (Ni and Cu electrodes, 3 mM KCl) with low voltage pulses (350-450 V) to produce nanostructured nickel precipitates, which, after filtration/drying, Nafion-based ink preparation, ultrasonic dispersion, and electrochemical activation (CV in 0.5 M KOH), convert to NiOOH/NiCuOOH—the active ammonia-oxidation electrocatalysts. During operation, NH₃ is electro-oxidized to N₂ at the anode and H₂ evolves at the cathode, delivering hydrogen without the use of thermal crackers or precious metals. The primary advances are plasma-assisted catalyst synthesis under mild circumstances and a non-precious-metal Ni/NiCu AOR system, developed for efficient and scalable hydrogen production from ammonia via electrochemistry [

78].

CN119843312A, filed in Jan 2025, is the most recent invention. It shows a nickel-copper alloy nanoparticle electrocatalyst for effective hydrogen generation via ammonia electrooxidation. The Ni-Cu nanoparticles (5-7 nm, spherical) are manufactured by a one-pot oleylamine-assisted thermal reduction under nitrogen using tri-n-octylphosphine as a deoxygenating agent, yielding homogenous NiₓCuᵧ nanoparticles with adjustable ratios (Ni₀.₈Cu₀.₂ - Ni₀.₅Cu₀.₅). These are then placed onto a glassy carbon electrode, along with carbon black and Nafion, to create an active electrode catalyst. In an alkaline electrolyte (1 M KOH + NH₃), the alloy surface generates active NiOOH/Cu species, allowing for rapid ammonia electrooxidation and hydrogen evolution at a lower overpotential and with increased stability. The bimetallic catalyst outperforms pure Ni or Cu nanoparticles in terms of current density, kinetics, and durability, making it a viable low-cost electrocatalyst for producing carbon-free hydrogen from ammonia [

79].

The earliest invention, as well as the highly cited patent (4), CN106319555A, was filed in July 2015 and granted in June 2018. A low-temperature, pressure-resistant electrochemical method that directly electrolyzes anhydrous, oxygen-free liquid ammonia (with 1 mol L⁻¹ NH₄X as the supporting electrolyte) on Pt electrodes at 20 °C and 120 mA cm⁻² to produce H₂ and N₂ in a 3:1 ratio, achieving a current efficiency of up to ~94%. This eliminates the need for 400–600 °C reactors and noble-metal thermal catalysts that are typically needed for NH₃ cracking and showing that ammonia’s high hydrogen density can be accessed electrochemically for COₓ-free hydrogen supply [

80].

The fourth-most recent inventions applied by Huaneng Clean Energy Research Institute in 2018 are CN108360011A and CN208328127U. The low-energy ammonia electrolysis system in CN108360011A utilizes Ni–Co–Fe/Ni–Rh alloy electrodes in an alkaline NH₃–KOH electrolyte at ambient temperature and a low voltage of 0.8 V to produce high-purity hydrogen (99.9%). An integrated, clean, and renewable method of using green hydrogen is made possible by the direct supply of hydrogen to a coal liquefaction process. In line with the objectives of sustainable hydrogen production, the invention concurrently treats wastewater containing ammonia and lowers the energy need of traditional water electrolysis [

81].

Building upon this invention, CN208328127U, granted in 2019, translates the same principle into a practical system design, detailing component layout, electrode composition, and process flow. In short, the former defines the process innovation, and the latter protects the engineering embodiment of that process [

82].

The third most recent innovation, CN208183081U, was filed in April 2018 and received a grant in December 2018. The system is a combined ammonia electrolysis and wastewater treatment system that produces high-purity hydrogen (99.999%) for fuel cell vehicles from ammonia nitrogen wastewater. Using a Ni–Rh nanomaterial anode and a Ni–Co–Fe cathode, the technique generates clean hydrogen using renewable electricity while simultaneously removing up to 50% of the ammonia at room temperature and 0.6 V. This is an electrochemical innovation at the system level that connects sustainable hydrogen mobility and environmental remediation [

83].

The second most recent invention, CN210736904U, was filed in June 2019 and granted in June 2020. The solid-oxide electrolytic ammonia-to-hydrogen system receives liquid NH₃ from a storage tank, vaporizes and warms it through heat exchangers, and then sends it to an SOEC where it electrochemically oxidizes to N₂ at the anode and produces H₂ at the cathode, which is then collected after drying. Without the need for membrane H₂ separators or PSA, the system directly produces high-purity H₂ (≥99.99%) with a high yield (>93%) since N₂ and H₂ are generated on opposite sides of a thick electrolyte. Instead of using a new catalyst, the invention focuses on system integration (recycling anode off-gas, anode/cathode gas channels, two heat exchangers, and an optional expander) and aims to use less power than water electrolysis by using the chemical energy of NH₃ during electrolysis [

84].

The most recent innovation, CN115786967A, was filed in November 2022 and granted in May 2024. For use as a high-activity anode for ammonia electrolysis, it suggests a room-temperature electrosynthesis method for growing a bimetallic NiCu-NH₂-BDC MOF layer directly on conductive substrates (Ni foam, SS mesh, and carbon cloth). The catalyst forms in situ as 2D petal-like sheets when a three-electrode setup is used and a potential of –1.5 V is applied for approximately 100 s in a solution containing Ni²⁺, Cu²⁺, NH₂-BDC, and a surfactant/complexing agent. This results in a significantly higher NH₃-oxidation current than (i) plain Ni foam, (ii) electroplated NiCu, and even (iii) hydrothermally made NiCu-NH₂-BDC. The electrode works in alkaline NH₃ (pH 9–14) at only 0.5–0.7 V, targeting exactly the current bottleneck in ammonia electrolysis: high anode overpotential. Because it is a catalyst-level (Ni–Cu MOF anode) + scalable, low-T electrosynthesis approach, the innovation is appropriate for large-scale, dispersed ammonia-to-hydrogen systems [

85].

The first invention to be filed is KR101340492B1 in 2012. This invention presents a reversible solid oxide regenerative fuel cell (SORFC) system based on ammonia that is intended for the storage and conversion of renewable energy. It works in two ways: ammonia is created from nitrogen and water using excess renewable electricity in the electrolysis mode, and electricity is produced by electrochemically breaking down the stored ammonia into hydrogen and nitrogen in the fuel cell mode. Solid oxide electrolytes with noble metal or perovskite electrodes acting as ammonia-decomposing electrocatalysts are used in the system, which is controlled by a smart grid controller that automatically alternates between generation and storage in response to demand. This design, which is a system-level electrochemical breakthrough rather than a new catalyst discovery, makes it possible for a carbon-free, high-density, and economical ammonia–hydrogen energy cycle [

86].

This family, CN116472365A, is highly extended (10), with jurisdiction in the US, Japan, China, Korea, Europe, and Saudi Arabia. This US-original invention, which was filed in July 2020 and again in China in 2021, presents an electrochemical process akin to a fuel cell that produces compressed, high-purity hydrogen straight from ammonia: In order to provide compression, purification, and production in a single step without the need for mechanical compressors or downstream separations, NH₃ is electrocatalytically broken down at the anode over non-precious metal catalysts (Ni/Co/Fe/Ru) to N₂, protons, and electrons. Protons then pass through a proton-conducting solid oxide membrane (doped barium cerate/zirconate) and recombine with electrons at the cathode to form H₂ at a regulated pressure. The cell permits independent anode/cathode pressurization to adjust thermodynamics and reduce seal stresses, and the electrodes are standard porous composites (e.g., Ni–electrolyte anodes; LSCF/LSF/LSM perovskite cathodes). The outcome is a smaller, less expensive process that does not require external compression or precious metals, making electrochemical NH₃-to-H₂ conversion a viable choice for refueling stations and distributed hydrogen supply [

87].

Filed in December 2021, AU2021/468503A1 also has a large number of extended families (10), with the biggest number of distinct family jurisdictions (7) in the US, China, Korea, Japan, Australia, Europe, and WIPO (2023). This patent describes a solid-oxide electrochemical membrane reactor that uses no external electricity to create hydrogen from ammonia. Steam feeds the cathode, and ammonia or cracked ammonia feeds the anode. By transferring oxide ions and electrons, a co-doped ceria (CGO) mixed-conducting membrane facilitates the production of hydrogen at the cathode. Nickel-based cermet electrodes serve as both electrocatalysts and in-situ ammonia-cracking catalysts, allowing the process to function effectively without the need for a H₂/N₂ separation step. A burner and heat exchanger are included into the system to recycle thermal energy from the anode exhaust, creating a high-efficiency, self-sustaining loop. All things considered, the invention combines electrochemical and catalytic processes to produce a small, carbon-free, power-free system for localized hydrogen synthesis from ammonia [

88].

The most recent innovation, filed in October 2023, is WO2024/129246A1. The high-temperature electrochemical reactor proposed in this invention produces high-purity hydrogen in a single unit from ammonia (or NH₃-cracked gas, comprising H₂ and N₂). A porous, mixed-conducting catalytic layer (Ni, Co, Ru, LST, and doped La-chromite) serves as the anode and has the ability to provide H species and crack NH₃ in situ. Only hydrogen species can pass through a ceramic membrane that conducts both protons and electrons between the anode and cathode, keeping N₂ and any leftover NH₃ on the anode side. On the cathode, without a separate PSA or Pd membrane, the transported species recombine to produce ≈99.5% H₂ at reduced pressure or vacuum (and optionally steam). This is similar to water electrolysis. The reactor can be planar or tubular, operate between 500 and 800 °C, and is not equipped with current collectors or interconnects [

89].

In order to produce pure H₂ and in-situ separation (aided by pressure/vacuum), the first electrochemical NH₃-cracking patent (AU2021/468503A1) employs a mixed proton–electron conductor to break NH₃ directly at the anode and transfer H⁺ to the cathode. In contrast, NH₃/NH₃-cracked gas on the anode only provides the chemical energy and heat via a burner–ammonia–cracker loop, whereas WO 2023/063968 uses a mixed oxide–ion–electron conductor to produce H₂ from steam at the cathode.

The oldest invention, CN111321422A, was filed in April 2020 and granted in August 2021. It is the most cited patent (5) and the most cited by (6). This patent describes a room-temperature electrochemical liquid-ammonia-to-hydrogen system that uses Pt/Ru/Ir or transition-metal-nitride electrocatalysts to split liquid NH₃ containing ammonium salts into H₂ and N₂ at low overpotential. The mixed gas then passes through a condenser, a Pd-membrane purifier, and a secondary NH₃ absorber to deliver fuel-cell-grade hydrogen while returning NH₃ for recycling. By switching from high-temperature thermal NH₃ cracking to modular, distributed, low-energy electrocatalytic NH₃ decomposition, the patent contributes to the ammonia-to-hydrogen landscape by providing a route for on-site H₂ supply (e.g., refueling stations, remote telecom, and cold regions) where NH₃ serves as the transport/storage medium [

90].

KR20230131747A (May 2022), with the highest 9 extended families, presents a compact electrochemical NH₃-to-H₂ stack that merges the electrodes, gas-liquid diffusion layers, and separator into a single “composite electrode-separator” to reduce ohmic loss and size. The system uses a bipolar membrane to separate a neutral catholyte and alkaline anolyte, producing H₂ by HER when dissolved O₂ is ≤12% and switching to ORR-dominant power generation when O₂ increases. At >100 mA cm⁻², it uses ammonia-water electrolysis to increase H₂ generation. The stack employs standard Ni/Co/Fe/Cu and PGM catalysts on porous supports (e.g., Ni foam, Ti mesh), with its main innovation being oxygen-controlled mode switching and integrated hardware, enabling operation in power-only, power-plus-hydrogen, or hydrogen-only modes without heat cracking [

91].

The KR102602035B1 patent, filed in June 2023 and applied for by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology, depicts a solar-assisted non-aqueous photoelectrochemical cell that generates hydrogen from ammonia. Using acetonitrile and NaClO₄ as the electrolyte, ammonia is oxidized at a BiVO₄ photoanode under light to make N₂ and protons, which are reduced at a Pt cathode (via Nafion membrane) to generate H₂. At room temperature, the absence of water precludes side reactions, resulting in a Faradaic efficiency of approximately 89 percent. It is classified as electrochemical or photoelectrochemical ammonia oxidation, not thermal cracking [

92].

KR20250077260A is the most recent invention filed in November 2023. An ammonia liquefaction and electrolysis system that produces high-purity hydrogen without requiring high-temperature cracking or external purification. Ammonia gas is liquefied with salts containing ammonium ions (e.g., NH₄NO₃, NH₄PF₆, NH₄CF₃SO₃) and cycled through a flow-type electrolyzer equipped with a metal-oxide-treated anode, polymer electrolyte membrane, and cathode for hydrogen generation. The system converts NH₃ to N₂ at the anode and H₂ at the cathode. The membrane prevents NH₃ crossover [

93].

WO2022/010863A1 was filed in June 2021 and includes ten extended families from seven distinct family jurisdictions: the United States, Japan, China, Korea, Europe, Saudi Arabia, and WIPO. This invention shows an electrochemical ammonia-to-hydrogen system that creates and compresses hydrogen in a single proton-conducting fuel cell. Ammonia is fed to a metal-based decomposition anode (Ni, Co, Fe, Ru) and electrocatalytically oxidized to N₂, protons, and electrons. Protons migrate across a solid proton-conducting electrolyte (BaCeO₃/BaZrO₃) and recombine at the cathode to produce high-purity, pressurized H₂ without mechanical compressors. The process combines ammonia breakdown, hydrogen purification, and compression into one cell, demonstrating an energy-efficient, integrated electrochemical pathway for on-demand hydrogen synthesis and storage from ammonia [

94].

CN114104242A is the most recent invention filed in November 2021 and the most cited patent (12). A maritime hybrid power system that generates hydrogen electrochemically from liquid ammonia using an ammonia electrolyte battery. The cell uses Pt and Pt/C electrocatalysts in an alkaline electrolyte (KOH/NaOH) to oxidize NH₃ to N₂ at the anode and produce H₂ at the cathode. The generated H₂ is either pumped into a fuel cell or injected into a dual-fuel diesel engine to improve combustion. The system combines ammonia storage, buffering, electrolysis, and energy recovery in a single shipboard design, allowing for on-demand hydrogen production and propulsion without the need for external storage or thermal breaking catalysts [

95].

The National Engineering Research Center of Chemical Fertilizer Catalyst applied for both CN110295372A (invention) and CN210736903U (utility model), which were filed in June 2019. The most cited patent (7) is CN110295372A, which presents an integrated solid-electrolyte ammonia electrolysis hydrogen generation system that includes Ni-based anodes, perovskite-type cathodes, optional Ru/Ni ammonia-decomposition catalyst layers, and a heat-recycling combustion chamber. The invention patent CN110295372A offers a comprehensive theoretical and material framework, including oxygen-ion and proton-conductor configurations (YSZ, GDC, LSGM, BaCeO₃, BaZrO₃, etc.), full electrochemical reactions, and catalyst chemistry to achieve higher hydrogen purity and energy efficiency. The system feeds gaseous ammonia through a distribution chamber, preheats air and steam with waste heat, and electrochemically splits ammonia into nitrogen (at the anode) and high-purity hydrogen (at the cathode). Unreacted ammonia is directed to a catalytic or porous-media burner for complete conversion [

96].

Meanwhile, the utility model CN210736903U focuses on engineering optimization, fine-tuning the mechanical layout, preheating channels, and energy recovery design to improve system functionality. It arranges several solid-oxide electrolysis cells in a modular architecture that includes airflow and steam preheating channels, optional Ru/Ni catalytic pre-cracking layers, and dual heat exchangers to maximize heat consumption. These two patents offer a technology combination that bridges conceptual electrochemical innovation and practical device engineering, showcasing China’s evolution from fundamental solid-electrolyte research to scalable, integrated ammonia-to-hydrogen systems for sustainable energy generation [

97].

4.2.6. Plasma-Catalytic Decomposition

CN114294130A is the earliest innovation submitted in February 2022, and it is the most cited by patent (6) held by the University of Shandong. A plasma-based integrated system that combines dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma with non-noble metal catalysts (Fe, Ni, Co, and Mn) to simultaneously decompose and ignite ammonia. Using a multi-frequency power supply, low-frequency plasma converts ammonia to hydrogen and nitrogen, while high-frequency plasma burns the ammonia-hydrogen combination. This plasma-catalyst interaction reduces the reaction temperature to 320–370 °C, allowing for effective in-situ hydrogen production and combustion. The design provides a zero-carbon, self-sustaining solution for both aboard and portable hydrogen fuel applications [

103].

The University of Zhejiang filed CN119701824A, the most recent invention and highest cited patent (9) in December 2024. A plasma–catalytic hybrid reactor is introduced in this invention to produce hydrogen from ammonia quickly and efficiently. An arc-temperature plasma zone and coaxial catalytic zones with a CeO₂/Ni reversed-phase catalyst—where Ni is encased by CeO₂ for improved stability and hydrogen selectivity—are integrated into the design. A three-dimensional plasma jet is maintained by a revolving spiral flow that is created when ammonia enters through tangential inlets. The catalyst is directly heated and activated by the jet, allowing for simultaneous catalytic breakdown and plasma excitation without the need for external heating. The reactor’s strong heat-mass transfer, quick starting, and great energy efficiency make it perfect for mobile and distributed hydrogen systems that run on renewable electricity. Combining heat, plasma, and catalytic interaction in a small, integrated system, it is an innovation in plasma-catalytic decomposition [

104].

This 2025 Chinese patent, CN119212789A, filed in 2023, has the highest number of extended families (19) with 5 different family Jurisdictions from Australia, China, Japan, Korea, and WIPO. It describes a low-temperature, non-noble plasma-catalytic method to make CO₂-free H₂ from NH₃. Instead of high-temperature (500–800 °C) Ru-based cracking, it uses a DBD cold-plasma reactor packed with an alumina-supported Ni catalyst promoted by Fe (typical 5 Ni–10 Fe/Al₂O₃), optionally with Co/Mn/Cu/Ag/La/Ce/Gd/Ba/K. The alumina support is chosen for its dielectric properties, so the plasma can polarize the catalyst, improve NH₃ adsorption, and form reactive NH/NH₂/H species, giving good NH₃ conversion and H₂/N₂ selectivity at ~atmospheric pressure, <400 °C, and modest plasma power (≤20–35 W g⁻¹). It also details scalable prep routes (impregnation, co-precipitation, sol-gel) and shows from GC that plasma alone is weak, but plasma + Ni–Fe/Al₂O₃ converts NH₃ effectively [

105].

The only invention in this category is CN118462383A, which Tongji University filed in April 2024. It describes an engine-integrated dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma jet-ignition system that can perform in-situ plasma-catalytic ammonia reforming for on-demand hydrogen generation. In this system, air and ammonia are added to a pre-combustion chamber where a high-voltage DBD plasma (5–10 kV, ~30 kHz) quickly breaks down ammonia into hydrogen and reactive radicals (NH, NH₂, H) in microseconds. A spark plug is then used to ignite these species, creating a jet flame that spreads into the main combustion chamber and guarantees stable ignition of the ammonia–air mixture. The plasma zone is coated with Fe-, Co-, or Ni-based catalysts to further increase the reforming efficiency and hydrogen yield, resulting in a potent plasma–catalyst interaction. A viable route to sustainable, ammonia-fueled power generation is provided by this small and effective system, which does away with the need for separate hydrogen storage, streamlines the fuel supply architecture, and greatly enhances ignition reliability and combustion performance in low-speed or marine ammonia engines [

106].

CN116854033A and CN116854034A were both filed in 2023, which is the earliest invention applied by University Xian Technology, which was invented by Zhao Ni and Tian Hao.

CN116854034A has the highest cited patent (9). It presents a plate-hole dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma-assisted device that integrates ammonia decomposition and hydrogen separation within a single, compact system. The upper reaction zone employs DBD plasma–catalytic ammonia decomposition using a Ni/MgO catalyst, where plasma-generated energetic electrons and radicals facilitate N–H bond dissociation to form hydrogen radicals. The lower section incorporates a Pd–Cu proton exchange membrane and zeolite molecular sieve, enabling in-situ hydrogen purification and simultaneous NH₃ adsorption. A surrounding magnetic coil stabilizes the discharge and enhances gas residence time, improving decomposition kinetics and plasma uniformity. This dual-stage plasma–catalyst–membrane configuration effectively minimizes NH₃–H₂ mixing and reverse reactions, achieving high hydrogen yield, purity, and energy efficiency in a compact and sustainable design [

107].

Meanwhile, CN116854033A designs a horizontal, sealed coaxial DBD membrane reactor that does NH₃ cracking, NH₃ clean-up, and H₂ separation in one pass. Gas first meets a plasma + Ni/MgO packed-bed zone that plasma-catalytically decomposes NH₃. The partially converted gas then goes through a plasma + zeolite zone that both finishes decomposition and adsorbs residual NH₃ to stop NH₃ carryover. Finally, the stream reaches a DBD hydrogen-separation unit where plasma splits H₂ to protons that permeate a Pd–Cu / proton-exchange membrane, so high-purity H₂ exits at the center while N₂ and unreacted NH₃ remain on the shell side. Continuous H₂ withdrawal suppresses the reverse reaction and mitigates “NH₃–H₂ mixing,” which is a weakness of ordinary plasma NH₃ crackers. The outer spiral coil adds a magnetic field that lengthens residence time and raises plasma utilization, so the device can run at a lower temperature and still give high NH₃ conversion plus purified hydrogen in a compact geometry [

108].

CN118807614A is the latest invention, filed in June 2024, and applied by the University of Hefei Technology. It discloses a concentric layered dielectric-barrier discharge (DBD) plasma reactor that enables simultaneous ammonia decomposition and hydrogen separation. The reactor comprises a quartz tube with successive layers: a porous support, a high-voltage electrode, a hydrogen-separation catalyst, a porous layer, a proton-conducting membrane, and an outer ammonia-decomposition catalyst (Fe-, Co-, Ni-, Fe–Co-, or Fe–Ni-based), all surrounded by a grounded copper mesh. When ammonia is introduced from the top, plasma generated between the electrodes activates NH₃, and the outer catalyst decomposes it into N₂ and H₂. The produced hydrogen permeates inward through the proton membrane and is collected via the central outlet, while unreacted gases exit through secondary outlets. Continuous hydrogen removal shifts the equilibrium toward complete conversion, achieving nearly 100% NH₃ decomposition under mild plasma conditions (~60 mL·min⁻¹ NH₃ feed, 80–90 mL·min⁻¹ H₂ output) [

109].

4.2.9. Hybrid (Combination of Synthesis Methods)

- a.

Thermal Catalytic and Electrochemical Decomposition

JP2013078716A, filed in Oct 2011 and granted in Nov 2015, is the earliest invention. It has the highest cited patent (15). It describes a system for compost/sewage plants that captures NH₃- and sulfur-containing biogas, concentrates it with a rotating porous sorption–heating unit, removes sulfur, and then cracks part of the ammonia in an electrically heated porous catalytic reactor (Ni or Ni–Cr on alumina) to produce H₂. The resulting NH₃–H₂ mixture is sent to a tubular solid-electrolyte power-generation cell (preferably BYZ) with a graded Ni–Fe anode—Fe-rich at the inlet for NH₃, more Ni downstream for H₂—so the gas is electrochemically decomposed while producing electricity. The power can be reused to heat the porous elements. Overall, it upgrades smelly, low-value NH₃ biogas into clean N₂/H₂O and on-site electricity without NOₓ/SOₓ and without big external furnaces [

120].

The US2014/0072889A1 patent, filed in September 2012, has been the most forward-cited by 19 other patents, presenting a system-level innovation for hydrogen production and utilization from ammonia within solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) and solid oxide regenerative fuel cell (SORFC) systems. Ammonia is used as the primary carbon-free fuel, decomposed either internally within the SOFC anode or externally in an ammonia-cracking reactor to produce hydrogen and nitrogen. The hydrogen is then electrochemically oxidized to generate electricity, while exhaust gases are recycled through hydrogen separators, water removal membranes, and cascaded pumps to increase overall fuel utilization. The system integrates multiple reactors, including an ammonia reactor, a Sabatier reactor, a molten carbonate fuel cell (MCFC), and an anode tail-gas oxidizer (ATO), to enable heat recovery, nitrogen removal, and minimization of greenhouse gases. The anode employs nickel-based cermet catalysts (Ni–YSZ or Ni–ceria) for ammonia decomposition and hydrogen oxidation, while a YSZ electrolyte serves as both an ionic membrane and a separator. Overall, this invention represents an advanced ammonia-fueled SOFC configuration that combines electrocatalytic hydrogen generation, thermal energy recovery, and emission-free power generation, making it suitable for stationary or industrial-scale carbon-free energy systems [

121].

US2023/0366109A1, a patent filed in 2023 with family Jurisdictions from the United States and WIPO, discloses a hybrid thermal–electrochemical cell designed for on-demand hydrogen production from ammonia at intermediate temperatures (~250 °C). The system couples thermochemical ammonia decomposition using Cs-promoted Ru/CNT catalysts with electrochemical hydrogen extraction across a solid-acid electrolyte (CsH₂PO₄). Hydrogen formed in the thermal layer is transported as protons through the membrane and recombines into ultra-pure H₂ at the cathode. This configuration eliminates the need for an external cracker or high-temperature reactor, achieving 100% Faradaic efficiency, low energy input, and ammonia tolerance up to 20% CO impurities. The innovation lies in combining catalytic and electrochemical processes within a single solid-state device, enabling compact and emission-free hydrogen conversion [

122].

Building on this, US2024/0425368A1, filed in Jan 2023, represents an advanced implementation of the same concept. It integrates a thermochemical Ru/CNT–Cs catalyst layer with an electrochemical solid-acid membrane cell operating around 250 °C, enhancing reaction efficiency and durability. The design further optimizes hydrogen separation and compression, removing the need for high-temperature cracking (>400 °C) or downstream purification while producing high-purity hydrogen. This patent has family Jurisdictions of Europe, Japan, the United States, and WIPO, with extended families of 4 [

123].

CN119677689A, filed in September 2023, is the latest invention and has the highest number of extended families (26), with 6 different jurisdictions: Japan, China, the United States, Europe, Mexico, and WIPO. It introduces a dual-stage, hybrid catalytic system for onboard hydrogen generation from ammonia in vehicles. The first stage is a thermal catalytic reactor that uses engine exhaust heat to crack ammonia on a 3D-printed TPMS or tube-bundle nickel-based catalyst, converting NH₃ → H₂ + N₂. When exhaust heat is insufficient (e.g., during cold start or idling), ammonia is redirected to a second-stage electrocatalyst unit, where a Ni-alloy heating element coated with catalyst electrically heats and decomposes ammonia. This design provides rapid startup, compact geometry, and efficient exhaust heat recovery, allowing vehicles to operate without compressed hydrogen storage while maintaining a stable hydrogen supply and clean, CO₂-free combustion [

124].

- b.

Thermal Catalytic and Plasma-based Decomposition