Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. P. expansum and Preparation of Spore Suspension

2.2. Resuscitation of Bacillus subtilis and Preparation of Cell-Free Supernatant

2.3. Fruit Preparation and the Effect of CFS on Blue Mould Disease of Grape and Citrus Fruits

2.4. Spore Germination, Germ Tube Elongation Test

2.5. Mycelial Growth and Dry Weight

2.6. Mycelial Activity Measurement

2.7. Morphology and Microstructure Examination

2.8. ROS Detection

2.9. Cell Leakage Detection

2.10. Cell Membrane Integrity Detection

2.11. RNA Extracted and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

2.12. Data Statistics and Analysis

3. Result

3.1. CFS Inhibited Spore Germination and Germ Tube Elongation of P. expansum

3.2. CFS Inhibit Mycelial Growth and Activity

3.3. Inhibitory Effect of CFS on the Pathogenicity of P. expansum in Inoculated Grape and Citrus Fruits

3.4. CFS Upregulated the Expression of Genes and Induced ROS Accumulation in the Mycelium of P. expansum

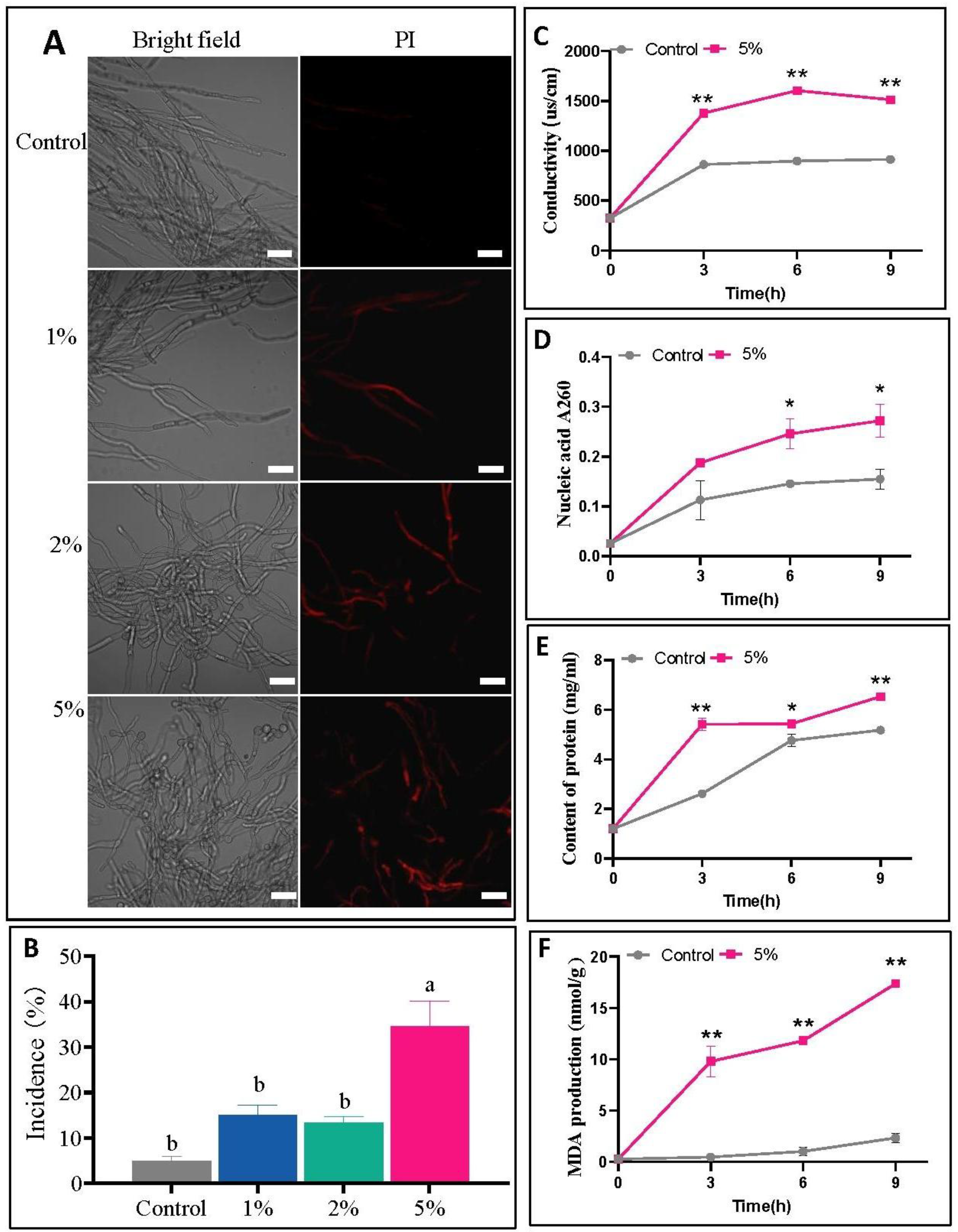

3.5. CFS Destroyed the Cell Membrane Integrity, Resulted in the Release of Cytoplasmic Components and Triggered Lipid Peroxidation in the Cell Membrane of P. expansum

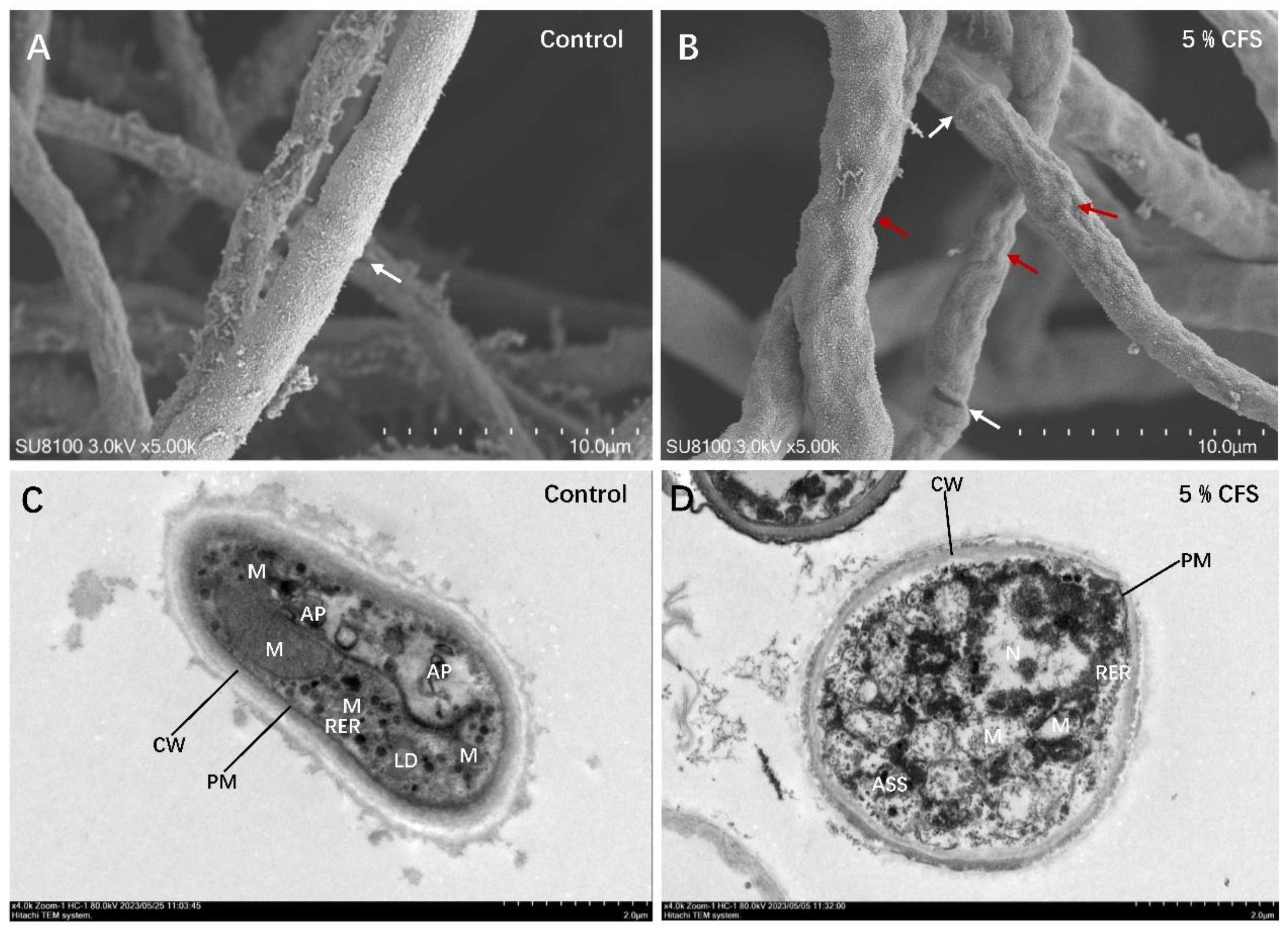

3.5. CFS Causes Mycelial Shrinkage and Deformation, Leading to the Breakdown of Cellular Organelles

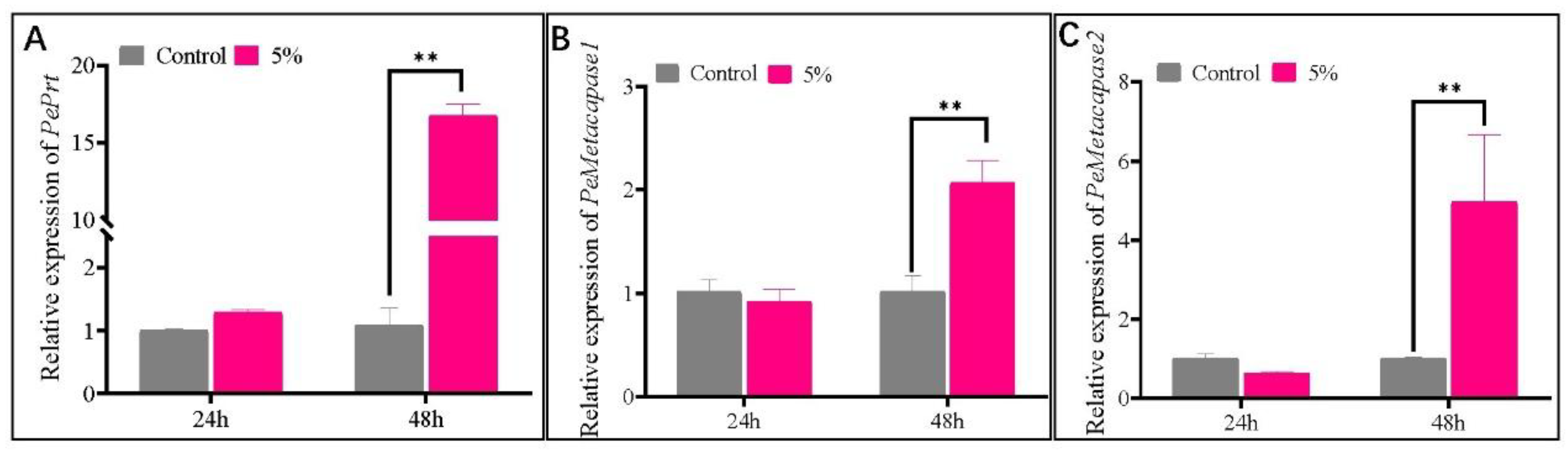

3.6. Alterations in the Expression Levels of Genes Associated with Autophagy Following CFS Treatment

4. Discussion

Funding

References

- Ackah, M.; Boateng, N.A.S.; Foku, J.M.; Ngolong Ngea, G.L.; Godana, E.A.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q. Genome-wide analysis of the PG gene family in Penicillium expansum: Expression during the infection stage in pear fruits (Pyrus bretschneideri). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 131, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zheng, X.; Su, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lanhuang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Godana, E.A.; et al. A glycoside hydrolase superfamily gene plays a major role in Penicillium expansum growth and pathogenicity in apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 198, 112228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano-Rosario, D.K.; Nancy, P.; Jurick, II; Wayne, M. Penicillium expansum: biology, omics, and management tools for a global postharvest pathogen causing blue mould of pome fruit. Mol. Plant Pathol 2020, 21, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimadadi, N.p.; Zahra Nasr; Shaghayegh, Fazeli; Seyed Abolhassan, Shahzadeh. Screening of antagonistic yeast strains for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum causing blue mold decay in table grape. Fungal Biol. 2023, 127, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Tong, Z.; Guo, D.; Sun, P.; An, D. Analysis and Evaluation of the Flagellin Activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Ba168 Antimicrobial Proteins against Penicillium expansum. Molecules 2022, 27, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droby, S. Improving quality and safety of fresh fruits and vegetables after harvest by the use of biocontrol agents and natural materials. Acta Hortic. 2006, 709, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Riachy, R.; Strub, C.; Durand, N.; Chochois, V.; Lopez-Lauri, F.; Fontana, A.; Schorr-Galindo, S. The Influence of Long-Term Storage on the Epiphytic Microbiome of Postharvest Apples and on Penicillium expansum Occurrence and Patulin Accumulation. Toxins 2024, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.H.; Bazioli, J.M.; de Moraes Pontes, J.G.; Fill, T.P. Penicillium digitatum infection mechanisms in citrus: What do we know so far? Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Apaliya, M.T.; Ianiri, G.; Zhang, H.; Castoria, R. Biocontrol Agents Increase the Specific Rate of Patulin Production by Penicillium expansum but Decrease the Disease and Total Patulin Contamination of Apples. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8–2017, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.; Gelezoglo, R.; Garmendia, G.; González, M.L.; Magnoli, A.P.; Arrarte, E.; Cavaglieri, L.R.; Vero, S. Role of Antarctic yeast in biocontrol of Penicillium expansum and patulin reduction of apples. Environ. Sustainability 2019, 2, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zheng, L.; Xia, F.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, L.; Rao, S.; Yang, Z. Biological control of blue mold rot in apple by Kluyveromyces marxianus XZ1 and the possible mechanisms of action. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 196, 112179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; Jia, Z.; Song, S.; Guan, J.; Shang, Z. Volatile organic compounds produced by Bacillus aryabhattai AYG1023 against Penicillium expansum causing blue mold on the Huangguan pear. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 278, 127531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, N.; An, J.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, C. Isolation and identification of Bacillus mojavensis YL-RY0310 and its biocontrol potential against Penicillium expansum and patulin in apples. Biol. Control 2023, 182, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qiao, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, F.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Postharvest control of Penicillium expansum in fruits: A review. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yao, M.; Chang, P.; Sun, Y.; Li, R.; Meng, D.; Xia, X.; Wang, Y. Isolation and characterization of a Pseudomonas poae JSU-Y1 with patulin degradation ability and biocontrol potential against Penicillium expansum. Toxicon 2021, 195, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi-Saiedlou, S.R.-S.; Mirhassan, Fattahi; Mohammad Ghosta, Youbert. Biosynthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles fabricated using cell-free supernatant of Pseudomonas fluorescens for antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.; Saladino, F.; Luciano, F.B.; Mañes, J.; Maca, G. In vitro antifungal activity of bioactive peptides produced by Lactobacillus plantarum against Aspergillus parasiticus and Penicillium expansum. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 81, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, B.; Liu, J. Identification of the Fungal Pathogens of Postharvest Disease on Peach Fruits and the Control Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis JK-14. Toxins 2019, 11, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, P.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Gong, H.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y. In vitro inhibition and in vivo induction of defense response against Penicillium expansum in sweet cherry fruit by postharvest applications of Bacillus cereus AR156. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 101, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Wang, J.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y. Bacillus cereus AR156 induces resistance against Rhizopus rot through priming of defense responses in peach fruit. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, T.; Chaouachi, M.; Sharma, A.; Jallouli, S.; Mhamdi, R.; Kaushik, N.; Djébali, N. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani using volatile organic compounds of solanaceae seed-borne endophytic bacteria. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzynski, J.; Jakubowska1, Z.; Kulkova, I.; Kowalczyk, P.; Kramkowski, K. Biocontrol of fungal phytopathogens by Bacillus pumilus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1194606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedretti, N.; Iseppi, R.; Condò, C.; Spaggiari, L.; Messi, P.; Pericolini, E.; Di Cerbo, A.; Ardizzoni, A.; Sabia, C. Cell-Free Supernatant from a Strain of Bacillus siamensis Isolated from the Skin Showed a Broad Spectrum of Antimicrobial Activity. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Jiang, J.M.; Sun, K.Y.; Ye, S.H. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LJ1 from Nanguo Pear: Suppressing Penicillium expansum colonization and degrading patulin in postharvest disease management. Food Control 2026, 179, 111564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, W.; Liu, M. Biocontrol potential of endophytic Bacillus velezensis strain QSE-21 against postharvest grey mould of fruit. Biol. Control 2021, 161, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.Y.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Q.Y.; Zuo, X.F.; Guo, A.L.; Lv, J. Characteristics of inhibition of Aspergillus flavus growth and degradation of aflatoxin B1 by cell-free fermentation supernatant of Bacillus velezensis 906. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirozawa, M.T.; Ono, M.A.; Suguiura, I.M.D.; Bordini, J.G.; Hirooka, E.Y.; Ono, E.Y.S. Antifungal effect and some properties of cell-free supernatants of two Bacillus subtilis isolates against Fusarium verticillioides. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, K.; Fan, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Song, W.; Liu, Y.; Miao, M. Cell-free supernatant of Bacillus velezensis suppresses mycelial growth and reduces virulence of Botrytis cinerea by inducing oxidative stress. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 980022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, K.; Lu, R.; Gao, J.; Song, W.; Zhu, H.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Miao, M. Cell-Free Supernatant of Bacillus subtilis Reduces Kiwifruit Rot Caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea through Inducing Oxidative Stress in the Pathogen. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Onaolapo, A.O.; Ibaba, A.L. Cell free supernatant for sustainable crop production. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1549048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Oudemans, P.; Hillman, B.; Kobayashi, D. Use of the tetrazolium salt MTT to measure cell viability effects of the bacterial antagonist Lysobacter enzymogenes on the filamentous fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2013, 103, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Su, Q.; Huang, Z.; Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Miao, M. Calcium Chloride Enhances Defense Response Against Diaporthe nobilis by Eliciting Reactive Oxygen Species in Kiwifruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2025, 2025, 8135751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Du, Y.; Li, Y.; Yue, F.; Dong, X.; Fu, M. Epsilon-poly-l-lysine (ε-PL) exhibits antifungal activity in vivo and in vitro against Botrytis cinerea and mechanism involved. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Tian, S. Antifungal effects of hinokitiol on development of Botrytis cinerea in vitro and in vivo. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 159, 111038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.; Kishore, A.; Ballester, A.R.; Raphael, G.; Feigenberg, O.; Liu, Y.; Norelli, J.; Gonzalez-Candelas, L.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S. Identification of pathogenicity-related genes and the role of a subtilisin-related peptidase S8 (PePRT) in authophagy and virulence of Penicillium expansum on apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 149, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zong, Y.; Gong, D.; Yu, L.; Sionov, E.; Bi, Y.; Prusky, D. NADPH Oxidase Regulates the Growth and Pathogenicity of Penicillium expansum. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 696210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, S.; Qin, G. NADPH Oxidase Is Crucial for the Cellular Redox Homeostasis in Fungal Pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2019, 32, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiatsiani, L.; Van Breusegem, F.; Gallois, P.; Zavialov, A.; Lam, E.; Bozhkov, P.V. Metacaspases. Cell Death and Differentiation 2011, 18, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.-y.; Wang, W.-w.; Jie, X.-r.; Gao, Z.-x.; Wang, H.-z. The metacaspase TaMCA1-mediated crosstalk between autophagy and PCD contributes to the defense response of wheat seedlings against powdery mildew. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilayh, O.A.; Hamed, K.E.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Abdelaal, K.; Omar, A.F. Characterization of Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of tomato grey mould, and its biocontrol using Bacillus subtilis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Chen, M.; Long, X.; Yang, H.; Zhu, D. Biological potential of Bacillus subtilis BS45 to inhibit the growth of Fusarium graminearum through oxidative damage and perturbing related protein synthesis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14–2023, 1064838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Li, R.; Kong, Z.Q.; Zhu, H.; Dai, X.F.; Han, D.F.; Wang, D. Genome Resource of Bacillus subtilis KRS015, a Potential Biocontrol Agent for Verticillium dahliae. Phytofrontiers 2024, 4, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Ma, D.T.; He, X.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.R.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, J.Y.; Deng, J. Bacillus subtilis KLBC BS6 induces resistance and defence-related response against Botrytis cinerea in blueberry fruit. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 114, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, B.; Citterico, M.; Kimura, S.; Stevens, D.M.; Coaker, G.L. Stress-induced reactive oxygen species compartmentalization, perception and signalling. Nat. Plants 403–412. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigam, M.; Punia, B.; Dimri, D.B.; Mishra, A.P.; Radu, A.-F.; Bungau, G. Reactive oxygen species: A double-edged sword in the modulation of cancer signaling pathway dynamics. Cells 2025, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monier, B.; Suzanne, M. The Morphogenetic Role of Apoptosis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2015, 114, 335–362. [Google Scholar]

| Gene name | Accession No. | Primer name | Sequence of primer(5’-3’) |

| PePRT [36] | PEX2_027670 | Pe-prtF | CCGATGTTACCCCTAAGCAG |

| Pe-prtR | AGGATCTGAGTGTAATTGGCG | ||

| PeNoxA [37] | PEX2_053880 | Pe-NoxAF | CATTAGATGAGTCGGCGTGG |

| Pe-NoxAR | CAAGTTCTGGGCGGATATGG | ||

| PeNoxR [37] | PEX2_056490 | Pe-NoxRF | CTCTGAAGATGAAGGTGCAGG |

| Pe-NoxRR | AACGCTCTTCCACCCATATC | ||

| PeRacA [37] | PEX2_019970 | Pe-RacAF | GTACACAACGAATGCTTTCCC |

| Pe-RacAR | GATCGTAATCCTCTTGTCCAGC | ||

| PeMetacaspased1 | XM_016744186.1 | CASP1-F | TGATGTTTTCAGGGTCCAAGG |

| CASP1-R | CATTTCGGATCGTGTTCAGC | ||

| PeMetacaspased2 | XM_016742860.1 | CASP2-F | ACCAGCAAAACCCGATGAG |

| CASP2-R | TTCGTCACCATCCAAGTCG | ||

| Isy1 | PEX2-072240 | Isy1-F | CAAAGCCTGAGCGACTACCA |

| Isy1-R | CGCCCTTCATCGTCGTAAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).