1. Introduction

Rubber trees (

Hevea brasiliensis) are perennial tropical trees that are the primary source of natural rubber, an important industrial raw material [

1]. Anthracnose of rubber tree caused by the genus

Colletotrichum is one of the main diseases restricting rubber output [

2]. The disease mostly affects the leaves, stems and fruits, causing leaf shedding, stem spotting, branch drying, fruit rot, and eventually resulting in reduced yield of rubber trees [

3]. Currently, the disease has been reported to occur in several countries, including Sri Lanka, China [

4], India [

5], and Brazil [

6], and

C. gloeosporioides and

C. acutatum were considered to be the main causative agents [

7]. In recent years, researchers have gradually discovered and identified some new and dominant species. For instance,

C. acutatum and

C. gloeosporioides causing anthracnose of rubber trees, were recorded for the first time in India [

8]. Four novel pathogenic species of

C. laticiphilum,

C. nymphaeae,

C. citri, and

C. simmondsii, all belonging to the

C. acutatum complex, were found in Sri Lanka [

9].

C. siamense [

10],

C. australisinense [

10],

C. wanningense [

7], and

C. cliviae [

11], which can cause leaf anthracnose in rubber trees, were found in China.

C. siamense and

C. australisinense are thought to be the main causal species of anthracnose in Hainan province where is one of the main rubber tree growing areas in China [

10]. The classification of species complexes associated with anthracnose of rubber tree is complicated, and the dominant species in different regions have great differences [

3], which brings certain difficulties to the disease control, therefore, the development of effective control measures has become a key priority.

The control of anthracnose causing rubber trees mainly focuses on chemical controls, breeding for disease resistance, agricultural, and biological controls. Generally, chemical controls are effective, but also cause some problems such as environmental pollution and the emergence of drug resistance. Disease-resistant breeding is economical and effective but requires a long research and development process [

12]. Agricultural strategies focus on land management and environmental improvement [

6], which is economical but slow in effect, and has geographical and seasonal characteristics. In contrast, biological controls have brighter application prospects due to the advantages of strong selectivity and environmental friendliness [

13]. Some antagonistic strains derived from actinomycete, bacterial and fungal sources were effective in controlling anthracnose of rubber trees. Three strains of

Streptomyces YQ-33, QZ-9, and WZ-2 with high antagonistic activity against

C. siamense were isolated and identified [

14]. The lipopeptide produced by

Bacillus subtilis Czk1, could significantly control anthracnose of rubber trees [

15], and it was more effective when combined with "Rootcon" [

16] a common chemical antiseptic. An endophytic fungal strain of

Dendrobium gloeosporioides was found to have a highly antagonistic effect on

C. gloeosporioides [

17]. Therefore, the identification of novel antagonistic strains against species of

Colletotrichum will provide more microbial resources for the biological control of anthracnose causing rubber trees.

The aim of this study is to identify the biocontrol strain that has effective control effect on leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China. In this study, we obtained a Bacillus velezensis strain SF334 that exhibited significant antagonistic activity against both of C. australisinense and C. siamense, two major pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China, from 69 candidate strains from a pool of 223 bacterial strains using paper filtering method. SF334 exhibited a great biocontrol potential in the prevention of leaf anthracnose of rubber trees. we explored the mechanism of SF334 inhibiting the mycelial growth of C. australisinense and C. siamense, and analyzed the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) characterizations and antagonistic spectrum of SF334. In addition, we completed the whole genome sequencing and conducted the comparative genomic analysis of SF334 with its closely related B. velezensis strains. it was indicated that SF334 has genes associated with antimicrobial and plant growth promotion. These works provide a new microbial resource for the biological control of leaf anthracnose of rubber trees, and laid a preliminary foundation for the subsequent application in forest and field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

All bacterial strains were cultured in nutrient agar (NA), nutrient broth (NB) or Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 28 ◦C. The fungal pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber tree, C. siamense CS-DZ-1 and C. australisinense CA-DZ-5 were isolated from experimental fields from National Rubber Germplasm Repository in Hainan, and were grown on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or in PDB (PDA without agar) medium at 25 ◦C. Other fungal strains including Magnaporthe oryzae causing rice blast, Fusarium oxysporum f. spcucumerinum causing root rot disease of cucumber, F. graminearum causing fusarium head blight, Alternaria solani causing early blight of potato, Phytophthora capsici causing pepper phytophthora blight, Botrytis cinerea causing gray mold disease of vegetables were cultured on PDA medium at 25 ◦C.

2.2. Screening and identification of SF334 strain

A library that includes 223 bacterial isolates has been established in our previous work [

18].

C.

siamense CS-DZ-1 and

C.

australisinense CA-DZ-5 were used to screen antagonistic strains. The fungal piece was placed in the center of the PDA media, and the filter papers were placed 2 centimeters away from the center. A 5 μL of the bacterial solution (OD

600=2.0) was added on the filter papers located in the left and right direction, and the same volume NB medium was added to the top and bottom as negative control. Three replicates in each group were cultured at 28℃ for 5-7 days. The inhibition rates were calculated according to the growth diameters, and SF334 with strong antagonistic activity against both of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense were screened. SF334 was isolated from the orchard soil sample that collected from Haidian Harbor Garden in Haikou city of Hainan province, China, on November 8, 2018.

The 16S rDNA sequences of SF334 were amplified using the universal primers of 27F and 1492R according to our previous protocol [

19]. The sequenced sequence was used to search in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, and the sequence of

16s rDNA of 39 strains with the lowest E-value were selected as the reference sequences. The results were finally imported into MEGA 11 soft to construct a phylogenetic tree by NJ (1200 bootstrap) method. The Genome-wide phylogenetic trees were constructed through the TYGS platform (

https://tygs.dsmz.de/). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis and DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) analysis were performed through the online website (

http://jspecies.ribohost.com/jspeciesws/) and (

https://ggdc.dsmz.de/), respectively.

2.3. Genomic sequencing, assembly and annotation of SF334

A single colony of SF334 was inoculated in NB medium, and incubated overnight at 28℃, 200 rpm min-1. The resulting bacterial solution was transferred to a new NB medium at a ratio of 1:100 for further incubation until the liquid reached the logarithmic stage (OD600 is between 0.4-0.8). The bacterial solution of SF334 was centrifuged at 4℃, 6000 rpm min-1 for 10 min and collected, then washed with 1×PBS buffer twice, finally were removed the supernatant. The resulting bacterial precipitates were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 15 min, then sent to The Beijing Genomics Institute for whole genome sequencing through PacBio Sequel II platform 4.

After obtaining raw data, the low-quality sequences, joint sequences, etc. were removed. Genome assembly was performed by the company. Open reading frames were predicted by GeneMark S (

http://exon.gatech.edu/GeneMark/); non-coding RNAs were predicted by tRNAscan-SE v1.3.3, Barrnap and Rfam databases; tandem repeats were predicted by Tandem Repeats Finder, prophages were predicted by PHASTER (

http://phaster.ca). The assembled sequences were annotated in GO (Gene Ontology), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups), Swiss-Prot, NR (Non-Redundant Protein Database), TCDB (Transporter Classification Database), CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database), CARD (The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database), antiSMASH and signal P6.0 databases for functional gene analysis and annotation.

The complete genome sequence of B. velezensis SF334 was deposited in GenBank under accession number CP125289.

2.4. Comparative genomic analysis

2.5. Biocontrol assays

For in vitro biocontrol assays, total 36 leaves from 1-meter-high Brazilian rubber trees that were obtained from the sprout of the ‘RRIM600’ cultivar were inoculated with agar disk containing mycelium of C. siamense and C. australisinense. Six agar disks were inoculated on each leaf, and cultured at 28℃ for 72 h. The diameters of the lesions were measured. The similar experiments were conducted on live Brazilian rubber trees using the106 conidium mL-1 suspension of C. siamense and C. australisinense. SF334 treatment (Tre) strategy meant that leaves were sprayed with the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 (OD600 = 1.0) 24 h after inoculation with C. siamense and C. australisinense SF334 preventive (Pre) strategy indicated that leaves were sprayed with the CS of SF334 24 h before inoculation with C. siamense and C. australisinense. The inhibitory percentages (IPs) were calculated by the formula: IP = (1- diameters of treatment/ diameters of control) × 100. The IP was calculated by using 36 technical replicates per assay.

2.6. Hyphal digestion observations

Three 50 μL of bacterial solution of SF334 with different concentration (OD600=1.0, 2.0, and 4.0) were dropped on the PDA medium covered with the mycelium of C. siamense and C. australisinense at a distance of about two centimeters away from the center, and the same volume NB medium was added to the top as negative control. The degradation condition of the mycelium was photographed every 30 min.

2.7. Microscopic observation

The fungal pieces of C. siamense and C. australisinense were added into PDB media, and cultured at 28℃, 180 rpm/min for 2 days, then were mixed with the bacterial solution of SF334 (OD600=1.5) for further incubating. The samples from the mixture at 1 hr post incubation (hpi), 3 hpi, and 6 hpi were stained with 0.05% Evans blue for 2 hr, then were observed under an optical microscope. The same experiments were conducted as above using the cell-free supernatants (CFSs) of SF334 prepared from the bacterial solution of OD600=1.5.

The samples at 1 hpi and 6 hpi were chose for observation by scanning electron microscope (SEM). First, the samples were treated overnight by 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and were fixed by 1% osmium acid, then were dehydrated by 30% ethanol, 50% ethanol, 70% ethanol, 90% ethanol, and anhydrous ethanol in turn, finally were dried by CO2 critical point dryer. The samples were observed by SEM (NOVA NanoSEM 230 ) at Instrumental Analysis Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University。

2.8. Analysis of plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) characteristics

The cellulose assay medium (20 g carboxymethyl cellulose, 2 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 6 g NaCl, 0.1 g CaCl2, 0.1 g MgSO4·7H2O, 20 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water, pH 7.0-7.5), the chitinase assay medium (15 g chitin colloid, 1.36 g KH2PO4, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.3 g MgSO4·5H2O, 3 g yeast extract, 15 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water, pH 7.0), the protease assay medium (A solution: 10% defatted milk, B solution: 3% agar solution; C solution: 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH= 7.0, A, B, and C were fully mixed), the PKO medium (0.5 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.2 g KC1, 0.2 g NaC1, 4 g Ca2(PO4)3, 0.1 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.0004 g MnSO4, 0.0002 g F eSO4, 0.5 g yeast extract, 10 g sucrose, 15 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water, pH: 7.0), the potassium-solubilizing medium (1 g potassium feldspar powder, 1 g CaCO3, 2 g Na2HPO4, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O:, 10 g sucrose, 0.5 g yeast extract, 15 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water, pH: 7.0), and the ferritin secretion capacity assay medium (3 g casein acids hydrolysate:, 1 mL 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mL 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mL CAS A solution(1 mM CAS,4 mM HDTMA,0.1 mM FeCl3), 5 mL CAS B solution (0.1 mM phosphate buffer, pH=7.0), 2 g sucrose, 20 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water) were prepared for the analyses of cellulose activity, pectinase activity, protease activity, phosphorus solubilizing activity, potassium solubilizing activity and siderophore production, respectively. A 50 μL bacterial solution of SF334 (OD600=2.0) was filled into the Oxford cup located in the middle of plate, and the plate was incubated at 28°C for 48 h to observe whether the hydrolysis circle was produced.

For IAA analysis, the bacterial solution of SF334 was directly inoculated into the YM medium (5 g mannitol, 0.05 g NaCl, 0.25 g K2HPO4, 1.5 g yeast extract, 0.05 g L-tryptophan, pH 7.0, 1000 mL distilled water) then incubated at 28°C,135 rpm min-1 for 96 h. The supernatant was mixed with the colorimetric solution (1.5 mL 0.5 M FeCl3, 30 mL H2SO4, 50 mL distilled water) to observe the changes in color.

2.9. Antifungal activity assays

M.

oryzae causing rice blast,

F.

oxysporum f.

spcucumerinum causing root rot disease of cucumber,

F.

graminearum causing fusarium head blight,

A.

solani causing early blight of potato,

P.

capsici causing pepper phytophthora blight,

B.

cinerea causing gray mold disease of vegetables were used as the target pathogens. The antifungal activity of SF334 was measured as our previous protocol [

20].

3. Results

3.1. Screening and identification of strain SF334 that exhibits highly antagonistic activity against C. siamense and C. australisinense

To screen antagonistic strains of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense, which are major pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China, we obtained 69 candidate strains from a pool of 223 bacterial strains using filtering paper method. Among these strains, we found a strain designated as SF334 that exhibited significant antagonistic activity against both of

C.

siamense strain CS-DZ-1 and

C.

australisinense stain CA-DZ-5 with an average inhibition rate of 66.17% and 68.15%, respectively (

Figure 1A and

Supplementary Figure S1).

To clarify the taxonomic status of SF334, we carried out the sequence alignment analysis of

16S rDNA gene, and constructed the corresponding phylogenetic tree (1200 bootstrap). The results indicated a 99.94% homology between SF334 and

Bacillus velezensis FZB42, a model strain of

B. velezensis [

21], and the phylogenetic tree showed that SF334 and

B. velezensis FZB42 were in the same branch (

Supplementary Figure S2), tentatively confirming that SF334 is

B. velezensis. We further sequenced the whole genome of SF334 (

Figure 1B), and subsequently selected 13

Bacillus strains including 5 strains of

B. velezensis for ANI and DDH analyses. The ANI values of SF334 with 5 strains of

B. velezensis exceeded 95%, the threshold for species demarcation, and the DDH values also exceeded the accepted species threshold of 70% (

Figure 1C). The ANI and DDH values did not go above the critical classification value for species when SF334 compared to the other strains (

Figure 1C). These results further confirmed that SF334 belongs to

B. velezensis.

3.2. Assessment of SF334 as an effective biocontrol agent for leaf anthracnose of rubber tree caused by C. siamense and C. australisinense

We used SF344 to perform biocontrol tests on Brazilian rubber trees. In the experiments based on detached leaves, we sprayed the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 on the leaves

in vitro of rubber trees, and implemented the prevention (Pre) and treatment (Tre) strategies. Compared with the control group (CK), the prevention efficacy of the CS of SF334 for leaf anthracnose caused by

C.

siamense was 60.08% and the control efficacy was 39.74% (

Figure 2A and

Figure 2C). The prevention and control effect of the CS of SF334 for leaf anthracnose caused by

C. australisinense was 72.15% and 40.6% (

Figure 2B and

Figure 2D), respectively.

Further, we conducted the similar experiments on live Brazilian rubber trees, and found that the prevention efficacies of the CS of SF334 for anthracnose caused by

C.

siamense and

C. australisinense were 79.60% and 71.96% (

Figure 3), whereas, the control efficacies were 39.60% and 40.54% (

Figure 3), respectively, which was consistent with the results

in vitro. These results suggested that SF334 is an effective biocontrol agent for protection of rubber trees against leaf anthracnose.

3.3. B. velezensis SF334 inhibits C. siamense and C. australisinense by disrupting the growth of mycelium

To further explore the antagonistic mechanism of SF334 against

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense, we attempted to drop the bacterial solution of SF334 to the growing hyphae of

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense on PDA media. The hyphae of both

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense were gradually degraded with the extension of interaction time (

Supplementary Figure S3), and were completely disrupted at about 3 hr post interaction (hpi) (

Figure 4A). The rate of hyphal degradation of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense was generally accelerated with the increase of bacterial concentration, however, the difference was weak when the OD

600 of bacterial concentration of SF334 was either 2.0 or 4.0 (

Figure 4A and

Supplementary Figure S3), suggesting that the ability of SF334 to cause hyphal degradation may be close to its peak.

The observation by optical microscopy showed that SF334 caused mycelial expansion of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense (mainly in the apical part and a few in the middle) (

Supplementary Figure S4). The Evans blue staining showed that the expanded mycelia were stained blue after interaction with SF334, indicating the death of mycelia (

Figure 4B). With the prolongation of interaction time, the mycelial expansion became more obvious, and the proportion of mycelial death gradually increased (

Figure 4B and

Supplementary Figure S4).

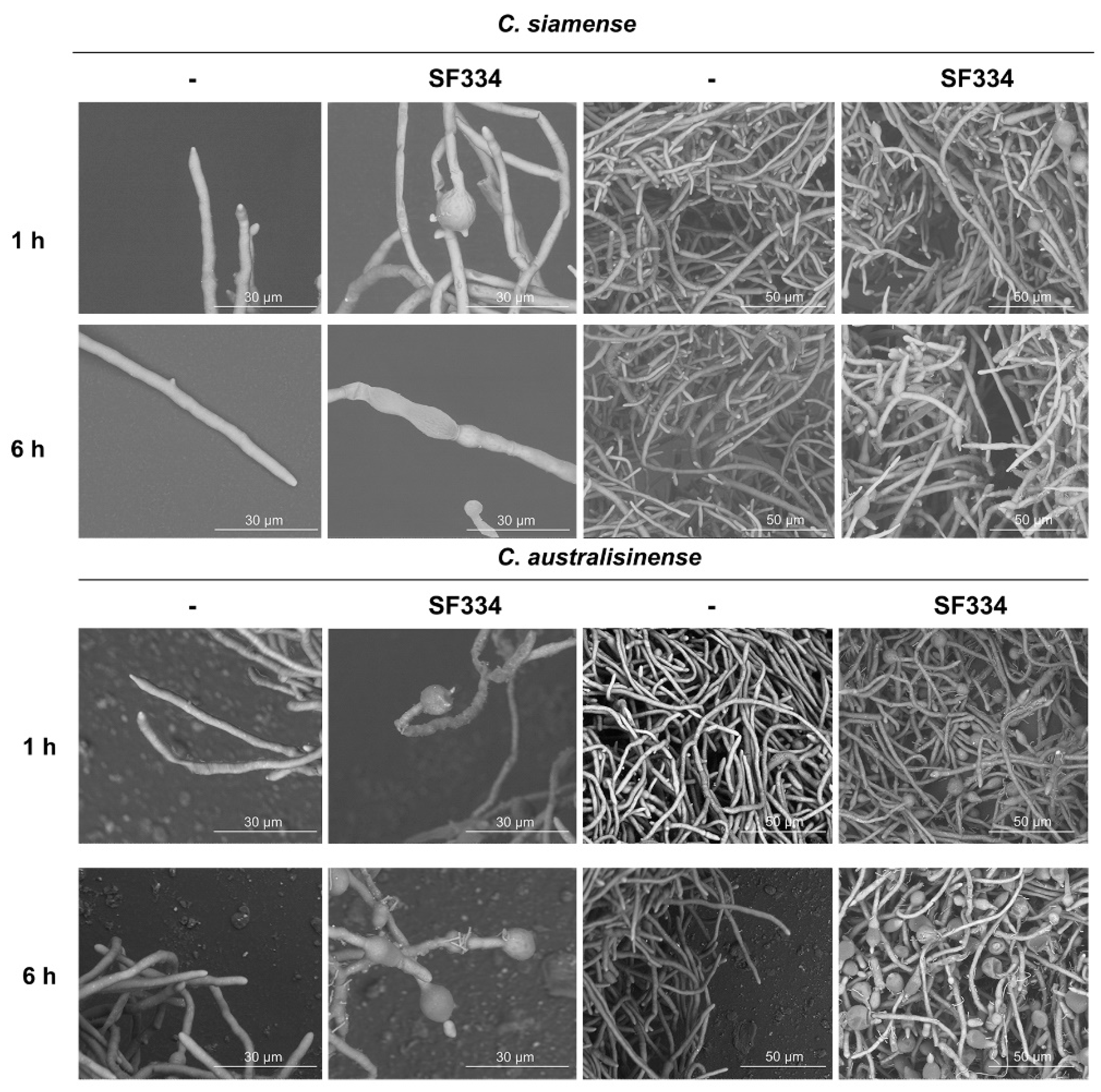

Since the mycelia of pathogenic

C. siamense and

C. australisinense depend on the apex growth, the apical expansions severely restrict the growth of mycelia. To further investigate the phenotype of mycelial death, we used scanning electron microscopy to observe the interactions of SF334 with

C. siamense and

C. australisinense. The observations showed that the mycelia of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense were regular in shape and full, with normal spore germination, the tip of single mycelium had a prominent growing point and could grow new mycelium continuously (

Figure 5). However, the tips of mycelia of

C. siamense and

C. australisinense were deformed and bulbous when interaction with SF334 for 1 h or 6 h (

Figure 5). The cell walls of the mycelia shrank and the contents of cells leaked obviously at 6 hpi (

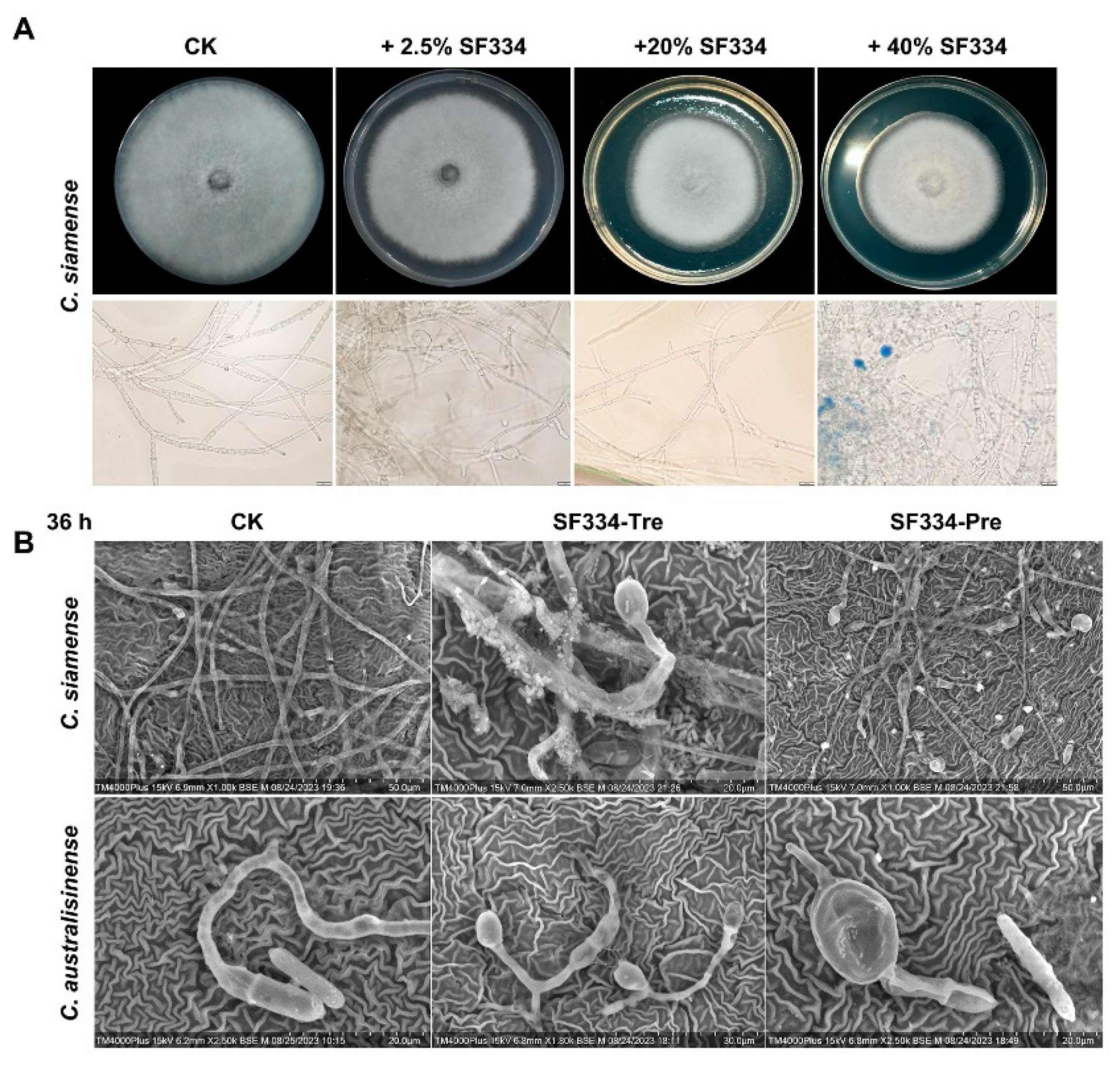

Figure 5). Similar mycelial expansion phenotypes were observed when we used the cell-free supernatants of SF334 to interact with

C. siamense (

Figure 6A), and when we sprayed the cell supernatant (CS) of SF334 on the live leaves of Brazilian rubber trees (

Figure 6B). From these results, we speculated that the extracellular active compounds secreted by SF344 may cause the deformations of mycelium, resulting in mycelial rupture and subsequent death.

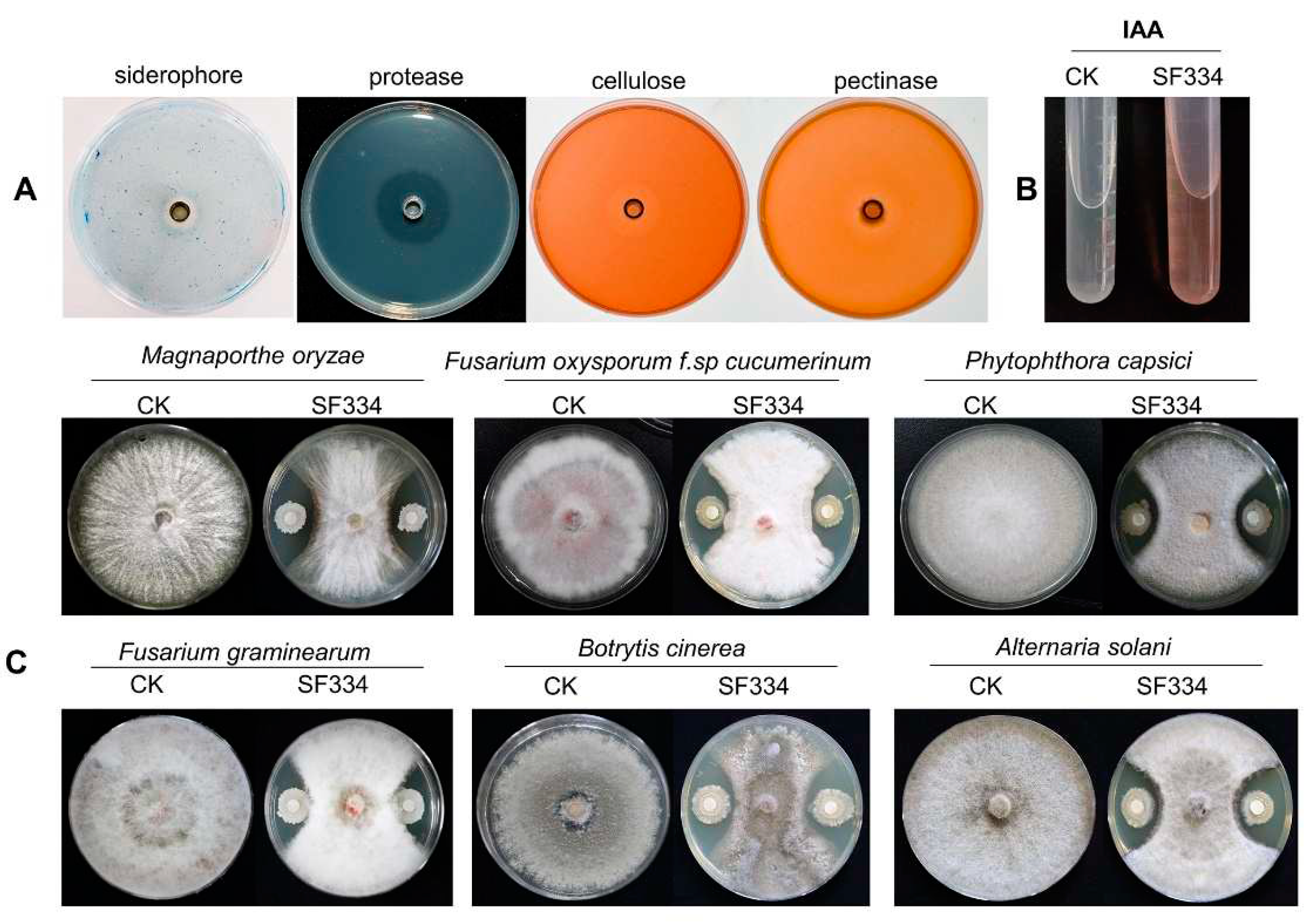

3.4. Analysis of the PGPR characterizations and antagonistic spectrum of B. velezensis SF334

To further examine the potential of SF334 for biocontrol applications, we conducted the analyses of PGPR characterizations and antagonistic spectrum against fungal pathogens. The analyses of some PGPR traits showed that SF334 could secrete siderophore and protease (

Figure 7A), however, does not have the ability to degrade inorganic phosphorus and potassium (data not shown). SF334 also could produce auxin of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (

Figure 7B), which is capable of stimulating plant growth. Our quantitative analysis showed that SF334 could produce IAA with 9.45 mg/L. SF334 also could secrete cellulose, and pectinase that can degrade the components of fungal cell walls (

Figure 7A), indicating that SF334 has the ability to degrade fungal cell walls. Whether the extracellular pectinase is responsible for the observed phenotypes of mycelial digestion remains to be determined. The antagonistic experiments based on the filter paper method showed that the inhibition rate of SF334 was 59.63% against

Magnaporthe oryzae causing rice blast, 50.93% agains

Fusarium oxysporum f.

spcucumerinum causing root rot disease of cucumber, 56.67% against

F.

graminearum causing fusarium head blight, 59.26% against

Alternaria solani causing early blight of potato, 51.48% against

Phytophthora capsici causing pepper phytophthora blight, and 61.85% against

Botrytis cinerea causing gray mold disease of vegetables (

Figure 7C). These results indicated that

B.

velezensis SF334 has broad-spectrum antifungal activity and is a versatile plant probiotic bacterium.

3.5. Genomic features and functional gene analysis of B. velezensis SF334

The genome of SF334 consists of a 4,078,641 bp circular chromosome without plasmid (

Figure 1B), with GC content of 46.5%, and 4,164 protein coding sequences (CDSs), occupying 88.76% of the total chromosome length. SF334 has 86 tRNA genes, 33 sRNA genes, 9 genes for 5S rRNA, 9 genes for 16S rRNA, and 9 genes for 23S rRNA (

Table 1).

The COG annotation results revealed that there are 3,022 genes annotated to the COG database in SF334 (

Table 1), accounting for 72.57% of the number of predicted genes. These genes were annotated to 24 COG entries, of which 18 entries had more than 100 annotated genes (

Supplementary Figure S5A). The most abundant genes are involved in amino acid transport and metabolism, followed by major functional, transcriptional, carbohydrate transport, and metabolic processes. SF334 has genes encoding peptidoglycan/xylan/gibberellin deacetylase (COG0726), β-glucanase (COG2273), and β-mannanase (COG4124), which may be associated with the hydrolysis of the fungal cell wall. Besides this, SF334 has two iron carrier transport systems (COG0609, COG1120) that facilitate competition for iron ions from environment to achieve competitive antibacterial purposes [

22].

The GO annotation results showed that 2376 genes were annotated to the GO database in SF334 (

Table 1), accounting for 57.06% of the number of predicted genes. Among them, 1297 genes are involved in cellular processes, followed by metabolic processes, catalytic activity, and binding processes (

Supplementary Figure S5B). SF334 has gene functions associated with fungal cell structure hydrolase activity such as carbohydrate metabolism (GO:0005975), chitin-binding domain (GO:0008061), and protease core complex (GO:0005839) predicting that SF334 may inhibit pathogenic fungi through antagonistic effects.

The KEGG analysis showed that SF334 has 2,554 genes annotated to 42 pathways, accounting for 61.33% of the total number of genes (

Supplementary Figure S5C), indicating that SF334 has abundant substance metabolic pathways and can use a variety of substances to meet its own needs, making it well-adapted to the environment. In addition, SF334 also has genes associated with growth hormone synthesis such as

trpA,

trpB,

trpC, and

aldh (

Supplementary Table S1), and it is assumed that SF334 may use tryptophan as a precursor substance to synthesize indole-3-acetic acid through the indole-3-pyruvate pathway (IPA pathway).

The CAzy analysis predicted that SF334 has 200 genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes, occupying 2.47% of the total number of genes, containing 59 genes related to carbohydrate synthesis and 141 genes related to hydrolysis (Supplementary S5D). Moreover, the SF334 genome contains 5 cellulose biohydrolases (EC 3.2.1.91), 9 tributylases (EC 3.2.1.14), 6 endoglucanases (EC 3.2.1.4), 15 lysozymes (EC 3.2.1.17), 3 mannanases (EC 3.2.1.78), and other related genes that may enable SF334 to have a strong ability to degrade the fungal cell wall. In addition, SF334 contains genes related to alglucan synthesis (EC 3.2.1.28), which are closely related to stress resistance of the strain [

23].

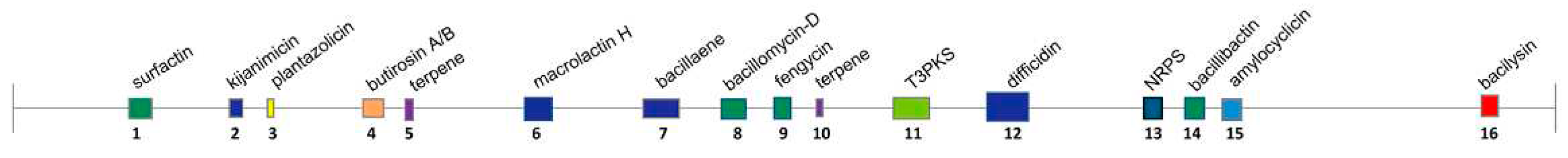

The antiSMASH analysis revealed that a total of 16 gene clusters related to secondary metabolite synthesis were obtained from SF334 (

Figure 8 and

Table 2), among which 8 known secondary metabolite gene clusters (macrolactin H, bacillaene, bacillomycin-D, fengycin, difficidin, bacillibactin, amylocyclicinand bacilysin) showed 100% similarity to known secondary metabolite synthesis gene clusters included in the database, and 10 reached more than 80% similarity, indicating that SF334 has a high probability of synthesizing these secondary metabolites. surfactin [

24], fengycin [

25], difficidin [

26], bacilysin [

27], and bacillibactin [

28] all possess antibacterial and antifungal activities, with antibacterial mechanisms involving direct inhibition, lysis, and competitive effects.

In summary, these analyses suggest that SF334 may be a multifunctional plant probiotic strain with probiotic and biocontrol properties.

3.6. Comparative genomic analysis of B. velezensis SF334 with other representative Bacillus strains

To investigate the differences between SF334 and other genetically related

Bacillus species, we selected four nowadays widely studied bacteria,

B. velezensis FZB42,

B. velezensis SQR9,

B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7, and

B. subtilis 168, for comparative analysis with SF334. The genomic characteristics of SF334 and the reference strains showed that the genome size of SF334 is between

B. velezensis FZB42 and

B. velezensis SQR9 (

Supplementary Table S2). The genomic GC content, coding region density, tRNA, rRNA, and the number of repeat regions of SF334 are similar to those of FZB42 (

Supplementary Table S2). Further collinearity analysis of SF334, FZB42 and SQR9 showed that the genomes of SF334 are highly similar to those of SQR9 and FZB42, with direct linear correspondence for most genes and gene rearrangements such as translocations in a few cases (

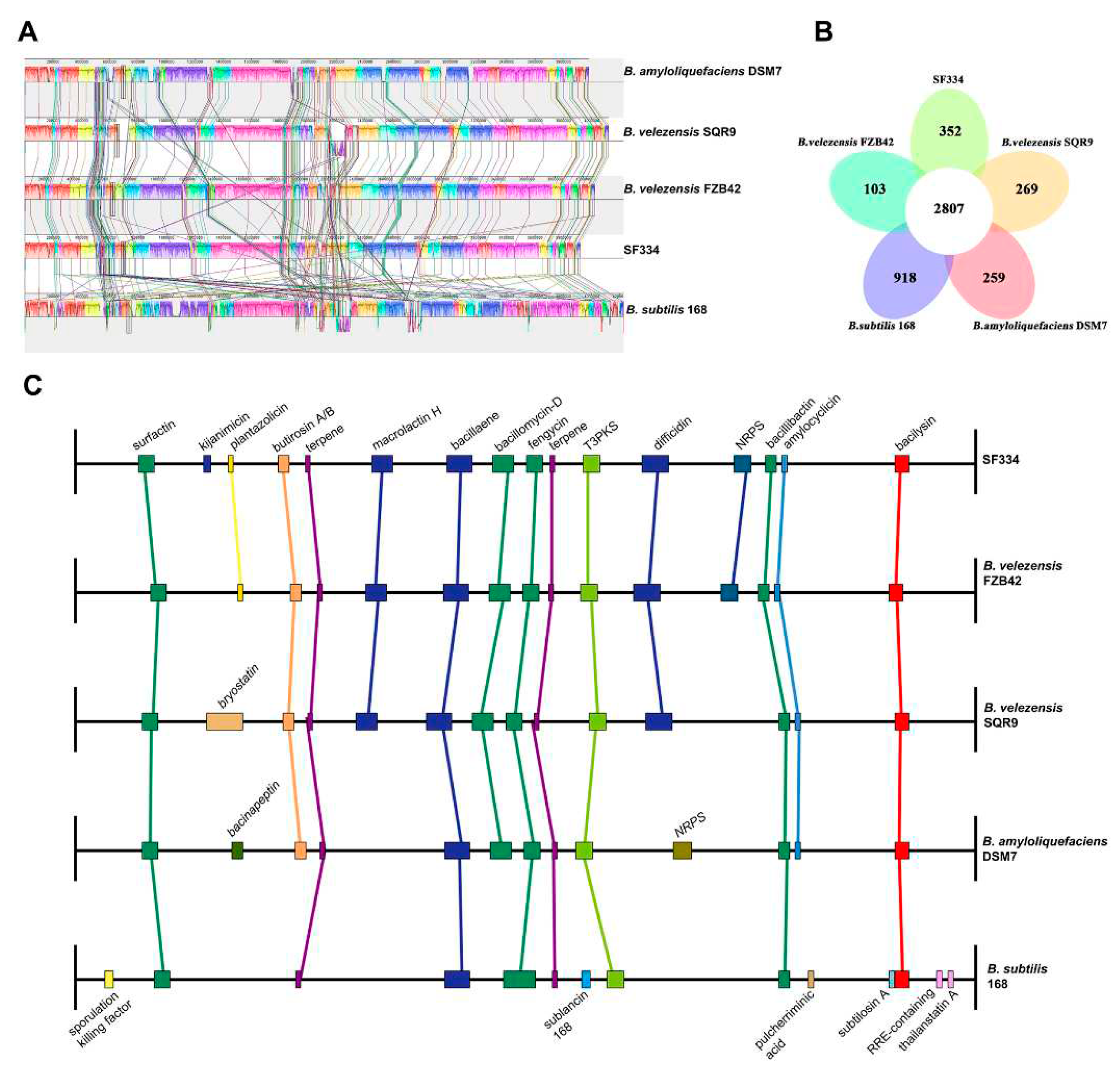

Figure 9A). The genomic similarity between SF334 and SQR9 is higher, indicating closer relativity.

Pan-genomic analysis by BPGA showed that SF334 has 2807 core genes and 352 endemic genes between SF334 and the four reference genomes, with high similarity among the five genomes (

Figure 9B). COG annotation results showed that the core genes are mainly distributed in the general functional cluster (R), amino acid transport and metabolism (E), and transcription (K) functional classifications, with the lowest proportion in cell cycle, division and chromosome assignment (D); endemic genes are mainly distributed in general functional clusters (R), transcription (K), and carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G) (

Supplementary Figure S6A). The results of KEGG annotation revealed that the core genes are mainly annotated to the carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism pathways, and only core genes are found in transcriptional and environmental adaptation pathways; the unique genes are mainly annotated to the carbohydrate metabolism and cell membrane transport pathways (

Supplementary Figure S6B). Combining the annotation results of COG and KEGG, the five strains have similar amino acid transport metabolic pathways, transcriptional pathways, and environmental adaptation pathways, which indicates functional similarity among strains. Each strain has its specific carbohydrate metabolic pathway and cell membrane transport pathway, suggesting that SF334 may have different functional properties such as unique carbohydrate-active enzymes.

We conducted the comparative analysis between SF334 and the other four

Bacillus species in the secondary metabolic gene clusters. Seven secondary metabolic gene clusters responsible for surfactin, terpene, bacillaene, fengycin, T3PKS, bacillibactin, and bacilysin are present in all three

Bacillus species (

Figure 9C). Thirteen of the 16 secondary metabolite gene clusters in SF334 are present in three

B.

velezensis strains (

Figure 9C). The secondary metabolic gene clusters contained by SF334 are highly similar to FZB42, with only one more synthesizing kijianimicin than FZB42. These results suggest that SF334 may have similar biocontrol functions with FZB42 in inhibiting microorganisms, inducing host resistance, and promoting plant growth.

4. Discussion

In this study, we isolated and identified a strain of B. velezensis SF334, which had a good prevention effect on leaf anthracnose of rubber tree caused by C. siamense and C. australisinense. In addition, we explored the antagonistic mechanism of SF344 against C. siamense and C. australisinense through microscopic observation including scanning electron microscopy under the interaction system between biocontrol bacteria and pathogenic fungi. This is the first time to report a B. velezensis as a potential biocontrol agent of leaf anthracnose of rubber tree caused by C. siamense and C. australisinense, which laid a good foundation for the green control of leaf anthracnose of rubber tree.

So far, there are few cases of biological control about anthracnose of rubber tree. However, some

B. velezensis strains for instance

B. velezensis CE100 [

29], PW192 [

30] and HN-2 [

31] have been reported to have the high potential as biocontrol agent for anthracnose diseases caused by

C.

gloeosporioides. In this study, we tested the control effect of SF334 on anthracnose of rubber tree by inoculating

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense with Pre and Tre strategies, respectively, and found that the efficacy could reach more than 70% by the Pre strategy, which was significantly higher than that by the Tre strategy. We speculated the reason for the low efficacy in the Tre strategy was due to our inoculation method, in which the inoculated mass may have provided a higher fungal initial source, resulting in a less effectiveness in subsequent spray or application of SF334. In the Pre strategy, SF334, which first existed on the leaves, killed part of the initial sources of fungi, meanwhile, blocked or delayed the infection of

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense on the leaves of rubber trees. Another speculation is that in this strategy, SF334 might trigger induced systemic resistance in rubber tree, as some cyclic lipopeptides (i.e., surfactin, fengycin, bacillomycin-D) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from two model strains of

B. velezensis FZB42 and SQR9 have been reported to induced resistance in plants [

28]. Therefore, the key to the prevention and control of leaf anthracnose lies in the early stage of the disease, when the initial number of fungi is not large. The preventive management of

B. velezensis as a biopesticide might have ideal effect.

In this study, we observed an interesting appearance that SF334 can cause the lysis of hyphae when interacting with

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense. Observations using microscope and scanning electron microscopy revealed that SF334 caused swollen structures of mycelium, especially the circular expansion at the growth point of mycelium is the most obvious. The swollen mycelium can be dyed blue by Evans blue, indicating the death of the mycelium. The similar results have been observed when the lipopeptide bacillomycin D, produced by

B. velezensis FZB42 and HN-2, was shown to interact with the hyphae of

F.

graminearum and

C.

gloeosporioides [

31,

32], indicating that bacillomycin D can cause the damage to the cell wall and membranes, resulting in leakage of the cytoplasm. However, some studies have also found that biosurfactants (i.e., fengycin A and fengycin B) and VOCs (i.e., 5-nonylamine and 3-methylbutanoic acid) produced by

B. velezensis exhibited antifungal activity against

C.

gloeosporioides, the causal agent of anthracnose disease of fruit trees [

29,

30]. We found that SF334 secretes cellulase and chitinase that can degrade the cell walls of fungi and oomycetes. Whether the malformed mycelium of

C.

siamense and

C.

australisinense treated by SF334 is due to bacillomycin D or other biosurfactants, as well as cellulase or chitinase remains to be further explored.

B. velezensis is a versatile plant probiotic Gram-positive bacterium that can produce 12 known bioactive molecules including cyclic lipopeptides (i.e., surfactin, fengycin, bacillomycin-D, and bacillibactin), polyketides (i.e., difficidin, bacillaene, and macrolactin), dipeptide antibiotics (bacilysin), and bacteriocins (i.e., plantazolicin and amylocyclicin), as well as VOCs (i.e., acetoin and 2,3-butandiol) [

28], which have been reported to exhibit a broad spectrum of antagonistic microbial activity. The antagonism of the model

B.

velezensis strain FZB42 against

Rhizoctonia solani causing bottom rot disease of lettuce, and

F. graminearum, a plant-pathogenic fungus of wheat and barley has been reported due to the presence of fengycin, and bacillomycin-D [

32,

33]. bacilysin and difficidin produced by FZB42 were reported to exert a biocontrol effect against bacterial blight and bacterial leaf streak caused by

Xoo and

Xoc, respectively [

26]. FZB42 was also reported to exert inhibitory effect against soybean pathogen

Phytophthora sojae and pear pathogen

Erwinia amylovora due to difficidin production [

27,

28]. Our comparative genomic analysis showed that SF334 is more closely related to FZB42 than SQR9, possessing 8 secondary metabolites gene clusters with 100% similarity with the ones of FZB42. In addition, we found that SF334 can secrete protease and siderophore, as well as produce IAA that can promote plant growth, and has antagonistic effects on some productively important plant pathogenic fungi (i.e.,

M.

oryzae,

B.

cinerea,

P.

capsici,

F.

graminearum, and

F.

oxysporum f.

spcucumerinum), suggesting that SF334 is also a multifunctional plant probiotic bacterium.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we isolated B. velezensis SF334 and demonstrated that it is a potential biocontrol agent for leaf anthracnose of rubber trees. This study not only found a new biocontrol effect of B. velezensis, but also provided ideas for the future green prevention and control of rubber tree diseases in field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Figure S1: Antagonistic effect of strain SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense, which are major pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China. Supplementary Figure S2. The phylogenetic tree of strain SF334 based on 16S rDNA sequences constructed through the TYGS platform. Supplementary Figure S3. Observation of the hyphal lysis of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 on PDA plates.Supplementary Figure S4. Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 for 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h in PDB medium by optical microscope. Supplementary Figure S5. Genomic analysis of B. velezensis SF334. The COG analysis (A), GO analysis (B), KEGG pathway analysis (C) and CAzy annotation (D) of B. velezensis SF334. Supplementary Figure S6. Comparative genomic analysis of B. velezensis SF334 with other related four Bacilus species. The COG analysis (A) and KEGG pathway analysis (B) of B. velezensis SF334 with B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168. Supplementary Table S1. The plant growth promotion associated genes in B. velezensis SF334. Supplementary, Table S2. General features of genomes of B. velezensis SF334, B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168.

Author Contributions

M.W., Y.Z., M.T. and L.Z. designed the research; Y.L. and G.C. (Gongyou Chen) supervised the study; M.W., Y.Z., X.Z., H.C. and Z.Z. analyzed the data and performed part of the experiments; M.W. and Y.Z. wrote the paper and generated the figures; Y.Y., Z.Z., K.Y., and G.C. (Guanyun Cheng) critically revised the manuscript; M.T. was responsible for funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1200204), Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2021XDNY291), and Special Fund for Hainan Excellent Team ‘Rubber Genetics and Breeding’ (20210203).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zou, Z.; Yang, L. F.; Wang, Z. H., Yuan, K. Biosynthesis and Regulation of Natural Rubber in Hevea. Plant Physiology Communications 2009, 45(12), 1231-8.

- Brown, Averil E., Soepena, H. Pathogenicity of Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides on leaves of Hevea spp. Mycological research 1994, 98(3), 264-6.

- Lin, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.B.; Li, X., Miao, W.G. Research Advances on Colletotrichum Leaf Fall Disease of Rubber Trees in China (in Chinese). Tropical Biology 2021, 12(03), 393-402+268.

- Liu, Xiujuan; Yang, Yetong, Leng, Huaiqiong. Identification Of Species And Forms Of Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides In Rubber Growing Regions In South China (in Chinese). Tropical Crops 1987, (01), 93-101.

- Forster, H., Adaskaveg, J. E. Identification of subpopulations of Colletotrichum acutatum and epidemiology of almond anthracnose in California. Phytopathology 1999, 89(11), 1056-65.

- Firmino, Ana Carolina; Magalhães, Izabela Ponso; Gomes, Marcela Eloi; Fischer, Ivan Herman; Junior, Erivaldo José Scaloppi, Furtado, Edson Luiz. Monitoring Colletotrichum Colonization and Reproduction in Different Rubber Tree Clones. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11(7), 905.

- Cao, X.R.; Xu, X.M.; Che, H.Y.; West, Jonathan S., Luo, D.Q. Three Colletotrichum Species, Including a New Species, are Associated to Leaf Anthracnose of Rubber Tree in Hainan, China. Plant Dis 2019, 103(1), 117-24.

- Saha, Thakurdas; Kumar, Arun; Ravindran, Minimol; Jacob, C. Kuruvilla; Roy, Bindu, Nazeer, M. A. Identification of Colletotrichum acutatum from rubber using random amplified polymorphic DNAs and ribosomal DNA polymorphisms. Mycol Res 2002, 106(2), 215-21.

- Hunupolagama, D. M.; Chandrasekharan, N. V.; Wijesundera, W. S. S.; Kathriarachchi, H. S.; Fernando, T. H. P. S., Wijesundera, R. L. C. Unveiling Members of Colletotrichum acutatum Species Complex Causing Colletotrichum Leaf Disease of Hevea brasiliensis in Sri Lanka. Curr Microbiol 2017, 74(6), 747-56.

- Liu, X.B.; Li, B.X.; Cai, J.M.; Zheng, X.L.; Feng, Y.L., Huang, G.X. Colletotrichum Species Causing Anthracnose of Rubber Trees in China. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 10435-14.

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, L. J.; Li, P. C.; Wang, M., Liang, X. Y. First Report of Colletotrichum cliviae Causing Anthracnose of Rubber Tree in China. Plant disease 2021, 105(12), 4163-PDIS04210814PDN.

- Cai, Z.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Zhai, L.G.; Cai, J.M.; Li, C.P.; Li, B.X.; Wang, Y.L., Huang, G.X. Evaluation of the resistance of 46 rubber tree clones to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (in Chinese). Plant Protection 2013, 39(06), 110-5.

- Stenberg, Johan A.; Sundh, Ingvar; Becher, Paul G.; Björkman, Christer; Dubey, Mukesh; Egan, Paul A.; Friberg, Hanna; Gil, José F.; Jensen, Dan F.; Jonsson, Mattias; Karlsson, Magnus; Khalil, Sammar; Ninkovic, Velemir; Rehermann, Guillermo; Vetukuri, Ramesh R., Viketoft, Maria. When is it biological control? A framework of definitions, mechanisms, and classifications. J Pest Sci 2021, 94(3), 665-76.

- Wang, J.H.; Wang, R.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.Q.; Tang, W.; Liu, Z.Q., Li, X.Y. Identification of three Streptomyces strains and their antifungal activity against the rubber anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum siamense. J Gen Plant Pathol 2023, 89(2), 67-76.

- Fan, L.Y.; He, C.P.; Zheng, F.C., Li, Q.J. Inhibition and resistance induction of anthracnose of rubber tree by crude extracts of Bacillus subtilis Czk1 lipopeptides (in Chinese); proceedings of the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Chinese Plant Protection Society, Xiamen, Fujian Province, China, F, 2014 [C].

- Xie, L.; He, C.P.; Liang, Y.Q.; Li, R.; Gong, J.L.; Zhai, C.X.; Wu, W.H., Yi, K.X. Antimicrobial activity of Bacillus subtilis Czk1 compounded with chemical fungicides against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (in Chinese). Southern Agriculture 2020, 51(10), 2480-7.

- Bian, J.Y.; Fang, Y.L.; Song, Q.; Sun, M.L.; Yang, J.Y.; Ju, Y.W.; Li, D.W., Huang, L. The Fungal Endophyte Epicoccum dendrobii as a Potential Biocontrol Agent Against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Phytopathology 2021, 111(2), 293-303.

- Yang, R.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zou, L., Chen, G. Bactericidal Effect of Pseudomonas oryziphila sp. nov., a Novel Pseudomonas Species Against Xanthomonas oryzae Reduces Disease Severity of Bacterial Leaf Streak of Rice. Front Microbiol 2021, 12759536.

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Chen, G., Zou, L. Isolation and identification of a Bacillus velezensis strain against plant pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. Acta Microbiologica Sinica 2019, 59(8), 1-15.

- Zhou, Q.; Tu, M.; Fu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Fang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yin, K.; Xiao, Y.; Zou, L., Chen, G. Antagonistic transcriptome profile reveals potential mechanisms of action on Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola by the cell-free supernatants of Bacillus velezensis 504, a versatile plant probiotic bacterium. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 131175446.

- Fan, B.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Ding, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Gao, X., Borriss, R. Bacillus velezensis FZB42 in 2018: The Gram-Positive Model Strain for Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol. Front Microbiol 2018, 92491.

- Kramer, J.; Ozkaya, O., Kummerli, R. Bacterial siderophores in community and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18(3), 152-63.

- Duan, J.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Heikkila, J. J., Glick, B. R. The complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Pseudomonas sp. UW4. PLoS One 2013, 8(3), e58640.

- Ali, S. A. M.; Sayyed, R. Z.; Mir, M. I.; Khan, M. Y.; Hameeda, B.; Alkhanani, M. F.; Haque, S.; Mohammad Al Tawaha, A. R., Poczai, P. Induction of Systemic Resistance in Maize and Antibiofilm Activity of Surfactin From Bacillus velezensis MS20. Front Microbiol 2022, 13879739.

- Hanif, A.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zubair, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J.; Majid, T.; Yan, J.; Farzand, A.; Wu, H.; Gu, Q., Gao, X. Fengycin Produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 Inhibits Fusarium graminearum Growth and Mycotoxins Biosynthesis. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11(5).

- Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, X.; Borriss, R., Gao, X. Difficidin and bacilysin from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 have antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas oryzae rice pathogens. Sci Rep 2015, 512975.

- Han, X.; Shen, D.; Xiong, Q.; Bao, B.; Zhang, W.; Dai, T.; Zhao, Y.; Borriss, R., Fan, B. The Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium Bacillus velezensis FZB42 Controls the Soybean Pathogen Phytophthora sojae Due to Bacilysin Production. Appl Environ Microbiol 2021, 87(23), e0160121.

- Rabbee, M. F.; Ali, M. S.; Choi, J.; Hwang, B. S.; Jeong, S. C., Baek, K. H. Bacillus velezensis: A Valuable Member of Bioactive Molecules within Plant Microbiomes. Molecules 2019, 24(6).

- Kim, T. Y.; Hwang, S. H.; Noh, J. S.; Cho, J. Y., Maung, C. E. H. Antifungal Potential of Bacillus velezensis CE 100 for the Control of Different Colletotrichum Species through Isolation of Active Dipeptide, Cyclo-(D-phenylalanyl-D-prolyl). Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(14).

- Jumpathong, W.; Intra, B.; Euanorasetr, J., Wanapaisan, P. Biosurfactant-Producing Bacillus velezensis PW192 as an Anti-Fungal Biocontrol Agent against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Colletotrichum musae. Microorganisms 2022, 10(5).

- Jin, P.; Wang, H.; Tan, Z.; Xuan, Z.; Dahar, G. Y.; Li, Q. X.; Miao, W., Liu, W. Antifungal mechanism of bacillomycin D from Bacillus velezensis HN-2 against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2020, 163102-7.

- Gu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Shi, G.; Wu, L.; Lou, Z.; Huo, R.; Wu, H.; Borriss, R., Gao, X. Bacillomycin D Produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Is Involved in the Antagonistic Interaction with the Plant-Pathogenic Fungus Fusarium graminearum. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83(19).

- Chowdhury, S. P.; Uhl, J.; Grosch, R.; Alqueres, S.; Pittroff, S.; Dietel, K.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Borriss, R., Hartmann, A. Cyclic Lipopeptides of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum Colonizing the Lettuce Rhizosphere Enhance Plant Defense Responses Toward the Bottom Rot Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2015, 28(9), 984-95.

Figure 1.

Screening and identification of strain SF334 that exhibits antagonistic activity against C. siamense and C. australisinense. (A) Antagonistic activity of strain SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense, which are major pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China. The average inhibition rates of SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense were indicated on the plates. (B) The genome features of strain SF334. The outer to inner circles respectively indicate genome side (1), forward strands (2) and reverse strands (3) colored according to the cluster of orthologous group (COG) category, sense strand non-coding RNAs (4), anti-sense strand non-coding RNAs (5), repeat sequence region (6), the GC content (7) and the GC skew in green (+) and purple (−) (8), respectively. (C) The ANI and DDH values of SF334 with 13 Bacillus strains including 5 strains of B. velezensis.

Figure 1.

Screening and identification of strain SF334 that exhibits antagonistic activity against C. siamense and C. australisinense. (A) Antagonistic activity of strain SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense, which are major pathogens causing leaf anthracnose of rubber trees in Hainan province of China. The average inhibition rates of SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense were indicated on the plates. (B) The genome features of strain SF334. The outer to inner circles respectively indicate genome side (1), forward strands (2) and reverse strands (3) colored according to the cluster of orthologous group (COG) category, sense strand non-coding RNAs (4), anti-sense strand non-coding RNAs (5), repeat sequence region (6), the GC content (7) and the GC skew in green (+) and purple (−) (8), respectively. (C) The ANI and DDH values of SF334 with 13 Bacillus strains including 5 strains of B. velezensis.

Figure 2.

The biocontrol assays of SF334 on Brazilian rubber trees based on detached leaves. The leaves in vitro of Brazilian rubber trees were inoculated with either C. siamense (A) or C. australisinense (B) for 72 h. The biocontrol efficiencies were calculated according to the lesion diameters by C. siamense (C) or C. australisinense (D). The treatment (Tre) strategy meant that leaves were sprayed with the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 (OD600 = 1.0) 24 h after inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense, the preventive (Pre) strategy indicated that leaves were sprayed with the CS of SF334 24 h before inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense. The Pre and Tre efficacies were indicated.

Figure 2.

The biocontrol assays of SF334 on Brazilian rubber trees based on detached leaves. The leaves in vitro of Brazilian rubber trees were inoculated with either C. siamense (A) or C. australisinense (B) for 72 h. The biocontrol efficiencies were calculated according to the lesion diameters by C. siamense (C) or C. australisinense (D). The treatment (Tre) strategy meant that leaves were sprayed with the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 (OD600 = 1.0) 24 h after inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense, the preventive (Pre) strategy indicated that leaves were sprayed with the CS of SF334 24 h before inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense. The Pre and Tre efficacies were indicated.

Figure 3.

The biocontrol effect of SF334 on Brazilian rubber trees against leaf anthracnose causing by C. siamense and C. australisinense. Leaf anthracnose were caused by C. siamense. (B) Leaf anthracnose were caused by C. australisinense. The biocontrol efficiencies of SF334 were calculated according to the lesion diameters caused by C. siamense and C. australisinense, respectively. The treatment (Tre) strategy meant that leaves were sprayed with the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 (OD600 = 1.0) 24 h after inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense, the preventive (Pre) strategy indicated that leaves were sprayed with the CS of SF334 24 h before inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense.

Figure 3.

The biocontrol effect of SF334 on Brazilian rubber trees against leaf anthracnose causing by C. siamense and C. australisinense. Leaf anthracnose were caused by C. siamense. (B) Leaf anthracnose were caused by C. australisinense. The biocontrol efficiencies of SF334 were calculated according to the lesion diameters caused by C. siamense and C. australisinense, respectively. The treatment (Tre) strategy meant that leaves were sprayed with the cell supernatants (CS) of SF334 (OD600 = 1.0) 24 h after inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense, the preventive (Pre) strategy indicated that leaves were sprayed with the CS of SF334 24 h before inoculation with either C. siamense or C. australisinense.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the antagonistic mechanism of B. velezensis SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense. (A) Observation of the hyphal lysis of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 on PDA plates. The mycelium of C. siamense and C. australisinense were inoculated with the indicated bacterial concentration for 0 h and 3 h. (B) Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 in PDB medium with or without 0.05% Evans blue staining by optical microscope. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the antagonistic mechanism of B. velezensis SF334 against C. siamense and C. australisinense. (A) Observation of the hyphal lysis of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 on PDA plates. The mycelium of C. siamense and C. australisinense were inoculated with the indicated bacterial concentration for 0 h and 3 h. (B) Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 in PDB medium with or without 0.05% Evans blue staining by optical microscope. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Figure 5.

Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 for 1 h, and 6 h in PDB medium by scanning electron microscope. Scale bars of 10 μm and 50 μm were indicated.

Figure 5.

Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 for 1 h, and 6 h in PDB medium by scanning electron microscope. Scale bars of 10 μm and 50 μm were indicated.

Figure 6.

The mycelial expansion phenotypes were observed when using the cell-free supernatants of SF334 to interact with C. siamense and when spraying the cell supernatant (CS) of SF334 on the live leaves of Brazilian rubber trees. (A) The inhibitory effect against C. siamense of the cell-free supernatants of SF334 The mycelium of C. siamense on PDA plates (upper), and in PDB medium (lower) with 0.05% Evans blue staining by optical microscope. The PDA plates or PDB medium were mixed with the cell-free supernatants of SF334 by indicated volume ratios. (B) Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 for 36 h on live leaves of Brazilian rubber trees by scanning electron microscope. Scale bars of 20 μm, 30 μm and 50 μm were indicated.

Figure 6.

The mycelial expansion phenotypes were observed when using the cell-free supernatants of SF334 to interact with C. siamense and when spraying the cell supernatant (CS) of SF334 on the live leaves of Brazilian rubber trees. (A) The inhibitory effect against C. siamense of the cell-free supernatants of SF334 The mycelium of C. siamense on PDA plates (upper), and in PDB medium (lower) with 0.05% Evans blue staining by optical microscope. The PDA plates or PDB medium were mixed with the cell-free supernatants of SF334 by indicated volume ratios. (B) Observation of mycelium morphology of C. siamense and C. australisinense when interacting with the CS of B. velezensis SF334 for 36 h on live leaves of Brazilian rubber trees by scanning electron microscope. Scale bars of 20 μm, 30 μm and 50 μm were indicated.

Figure 7.

Analyses of PGPR characteristics and antifungal activity of B. velezensis SF334. (A) The PGPR characteristics of B. velezensis SF334 including siderophore production, protease cellulose and pectinase activities were measured on agar plates. (B) The auxin of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production of B. velezensis SF334 were tested in YM medium. (C) The antifungal activities of B. velezensis SF334 against five plant pathogenic fungi were measured on PDA plates. M. oryzae causing rice blast, F. oxysporum f. spcucumerinum causing root rot disease of cucumber, P. capsici causing pepper phytophthora blight, F. graminearum causing fusarium head blight, B. cinerea causing gray mold disease of vegetables, A. solani causing early blight of potato were used as the target pathogens.

Figure 7.

Analyses of PGPR characteristics and antifungal activity of B. velezensis SF334. (A) The PGPR characteristics of B. velezensis SF334 including siderophore production, protease cellulose and pectinase activities were measured on agar plates. (B) The auxin of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production of B. velezensis SF334 were tested in YM medium. (C) The antifungal activities of B. velezensis SF334 against five plant pathogenic fungi were measured on PDA plates. M. oryzae causing rice blast, F. oxysporum f. spcucumerinum causing root rot disease of cucumber, P. capsici causing pepper phytophthora blight, F. graminearum causing fusarium head blight, B. cinerea causing gray mold disease of vegetables, A. solani causing early blight of potato were used as the target pathogens.

Figure 8.

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of

B.

velezensis SF334 predicted by AntiSMASH. The active molecules relate to the gene cluster (color boxes) and the cluster regions according to the

Table 2 were indicated above and below the horizontal line, respectively. T3PKS, type III polyketide synthases cluster; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthase cluster.

Figure 8.

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of

B.

velezensis SF334 predicted by AntiSMASH. The active molecules relate to the gene cluster (color boxes) and the cluster regions according to the

Table 2 were indicated above and below the horizontal line, respectively. T3PKS, type III polyketide synthases cluster; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthase cluster.

Figure 9.

Comparative genomic analysis of B. velezensis SF334 with other related four Bacilus species. (A) Genome-to-genome alignment of B. velezensis SF334 with B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168. Boxes with the same color indicate the syntenic regions. (B) Pan-genomic analysis showing the number of genes of orthologous CDSs shared and unique between five strains. (C) Comparison of the secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of B. velezensis SF334 with B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168. The same gene clusters are indicated by the same boxes and lines. T3PKS, type III polyketide synthases cluster; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthase cluster.

Figure 9.

Comparative genomic analysis of B. velezensis SF334 with other related four Bacilus species. (A) Genome-to-genome alignment of B. velezensis SF334 with B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168. Boxes with the same color indicate the syntenic regions. (B) Pan-genomic analysis showing the number of genes of orthologous CDSs shared and unique between five strains. (C) Comparison of the secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of B. velezensis SF334 with B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 and B. subtilis 168. The same gene clusters are indicated by the same boxes and lines. T3PKS, type III polyketide synthases cluster; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthase cluster.

Table 1.

General features of B. velezensis SF334 genome.

Table 1.

General features of B. velezensis SF334 genome.

| General features |

B. velezensis SF334 |

| Genome size (bp) |

4,078,641 |

| GC content (%) |

46.5 |

| Coding density (%) |

89.33 |

| Protein coding sequences (CDS) |

4,142 |

| tRNA |

86 |

| 5s rRNA |

9 |

| 16s rRNA |

9 |

| 23s rRNA |

9 |

| sRNA |

33 |

| Minisatellite DNA |

131 |

| Microsatellite DNA |

13 |

| Genes assigned to COGs |

3,022 |

| Genes assigned to GOs |

2,376 |

| Genes connected to KEGG pathways |

2,554 |

| Genes assigned to NR |

4,122 |

| Gene assigned to Swiss-Prot |

3,289 |

| Genes assigned to CAzy |

103 |

Table 2.

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of B. velezensis SF334 predicted by AntiSMASH.

Table 2.

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters of B. velezensis SF334 predicted by AntiSMASH.

| Cluster |

Type |

Location |

Most similar known cluster |

Similarity |

| Region 1 |

Lipopeptide (NRPS) |

308,479-373,284 |

Surfactin |

82% |

| Region 2 |

Polyketid (LAP) |

588,886-617,771 |

Kijanimicin |

4% |

| Region 3 |

Bacteriocin |

703,121-725,333 |

Plantazolicin |

91% |

| Region 4 |

Saccharide (PKS-like) |

937,179-978,423 |

Butirosin A/B |

7% |

| Region 5 |

Terpene |

1,063,300-1,080,597 |

Unknown |

ND |

| Region 6 |

Lipopeptide (NRPS) |

1,453,742-1,540,257 |

Macrolactin H |

100% |

| Region 7 |

Polyketid (NRPS/PKS) |

1,763,596-1,864,319 |

Bacillaene |

100% |

| Region 8 |

Lipopeptide (NRPS/PKS) |

1,951,281-1,995,921 |

Bacillomycin-D |

100% |

| Region 9 |

Lipopeptide (NRPS) |

2,004,711-2,054,255 |

Fengycin |

100% |

| Region 10 |

Terpene |

2,094,862-2,116,745 |

Unknown |

ND |

| Region 11 |

T3PKS |

2,226,268-2,267,374 |

Unknown |

ND |

| Region 12 |

Polyketid (NRPS) |

2,438,362-2,532,138 |

Difficidin |

100% |

| Region 13 |

NRPS |

3,021,959-3,071,468 |

Unknown |

ND |

| Region 14 |

Lipopeptide (NRPS) |

3,172,133-3,223,925 |

Bacillibactin |

100% |

| Region 15 |

Bacteriocin |

3,215,390 - 3,219,562 |

Amylocyclicin |

100% |

| Region 16 |

Dipeptide |

3,730,464-3,771,882 |

Bacilysin |

100% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).