Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

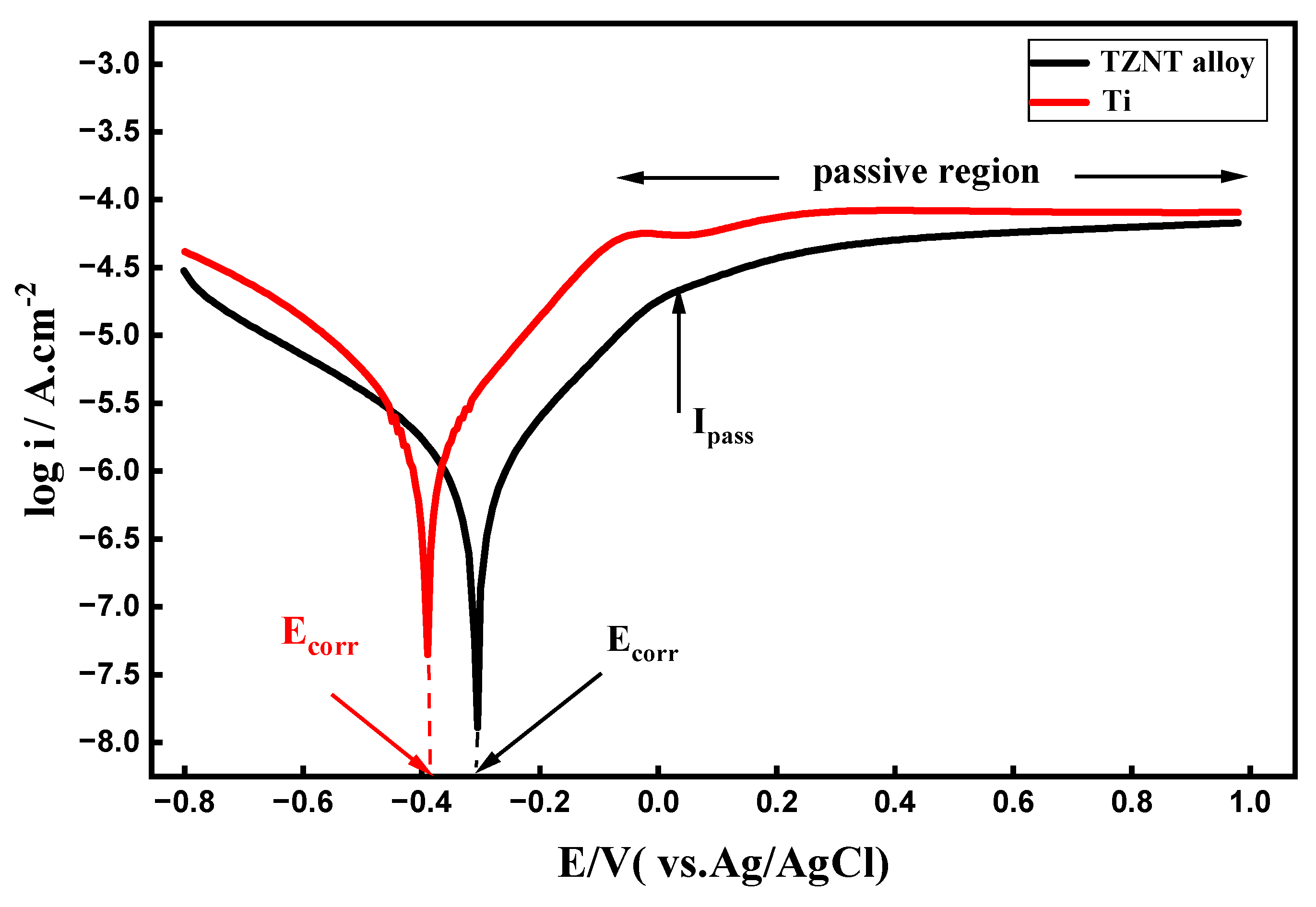

3.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization (PDP) Curves

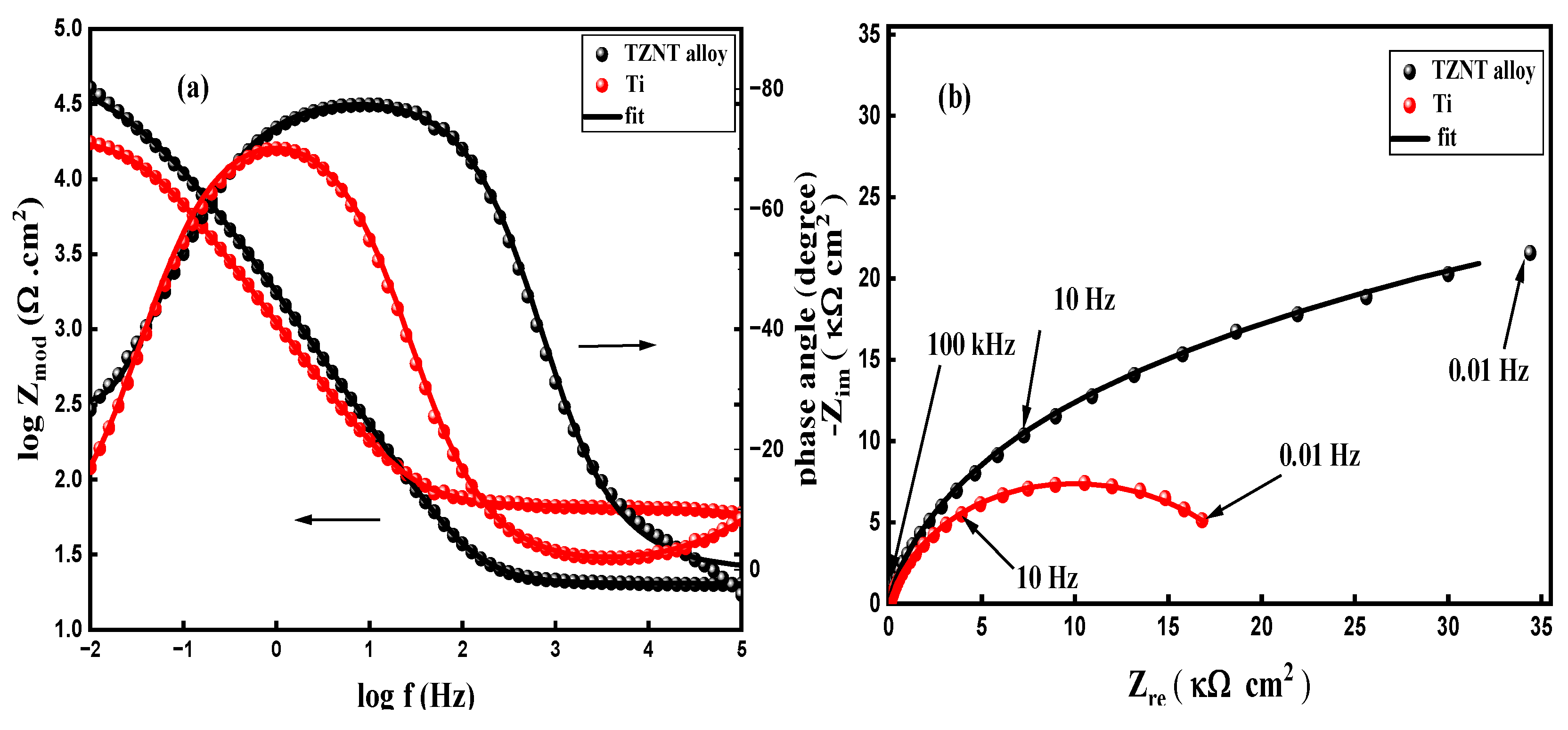

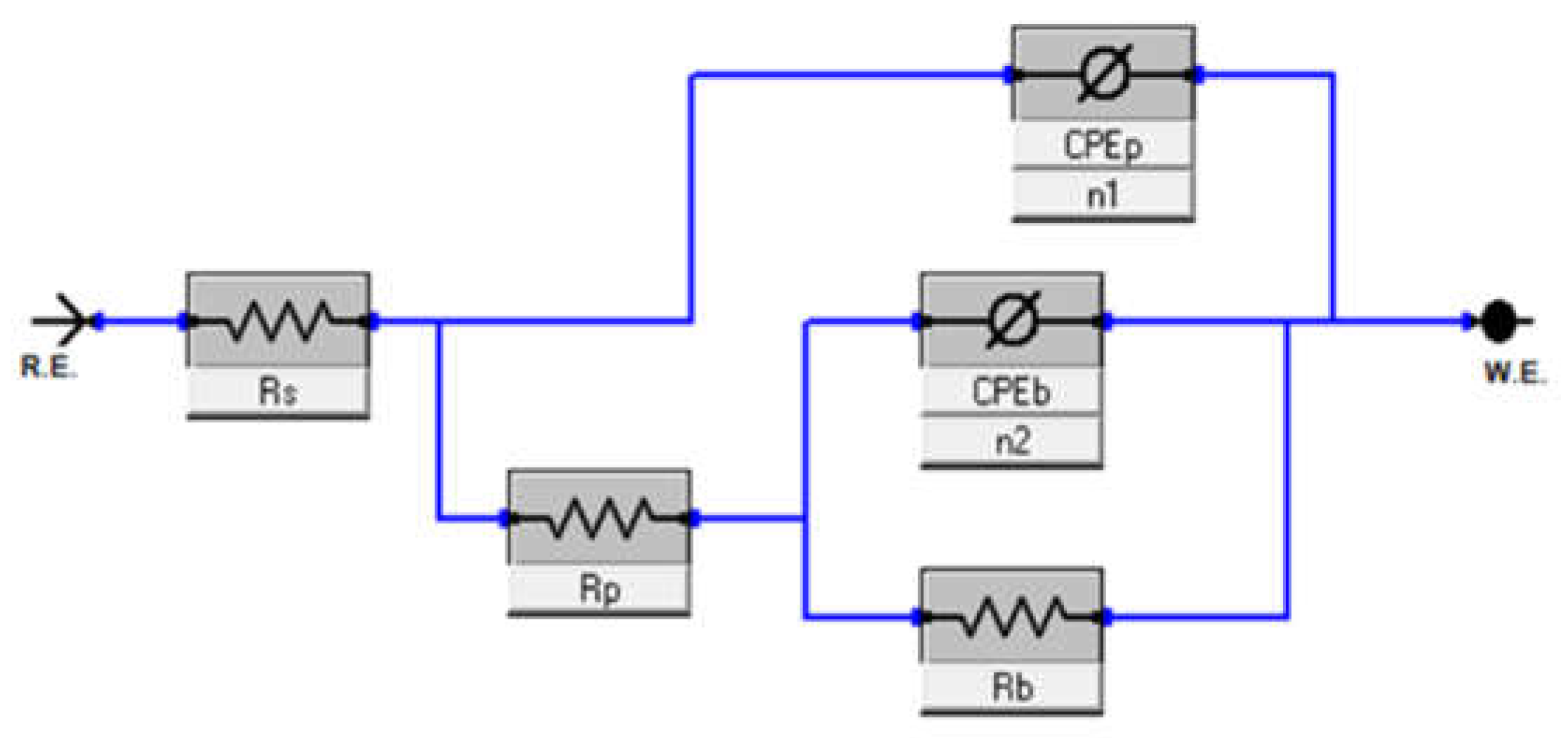

3.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

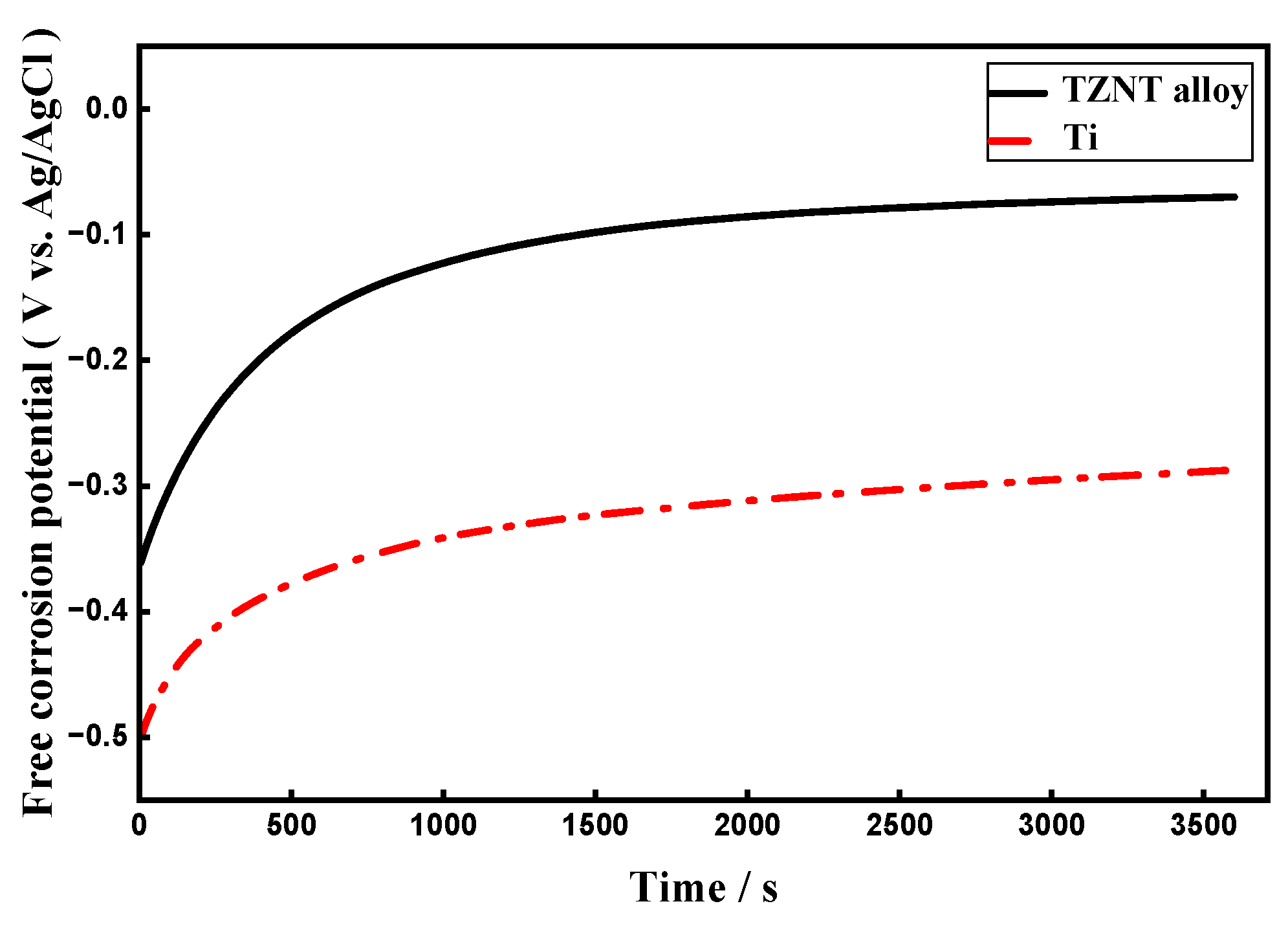

3.3. OCP Measurements

3.4. Effect of pH

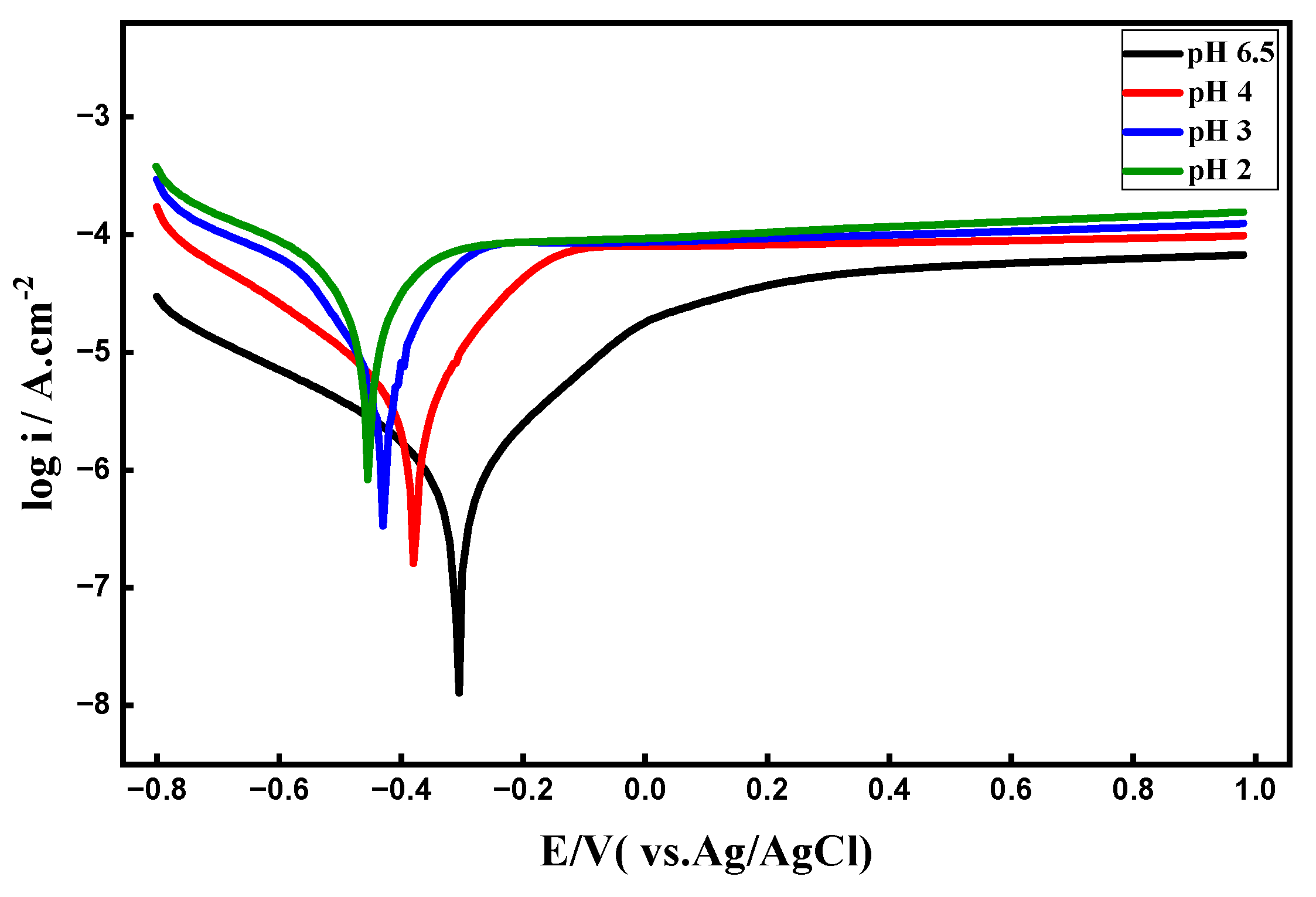

3.4.1. PDP Curves

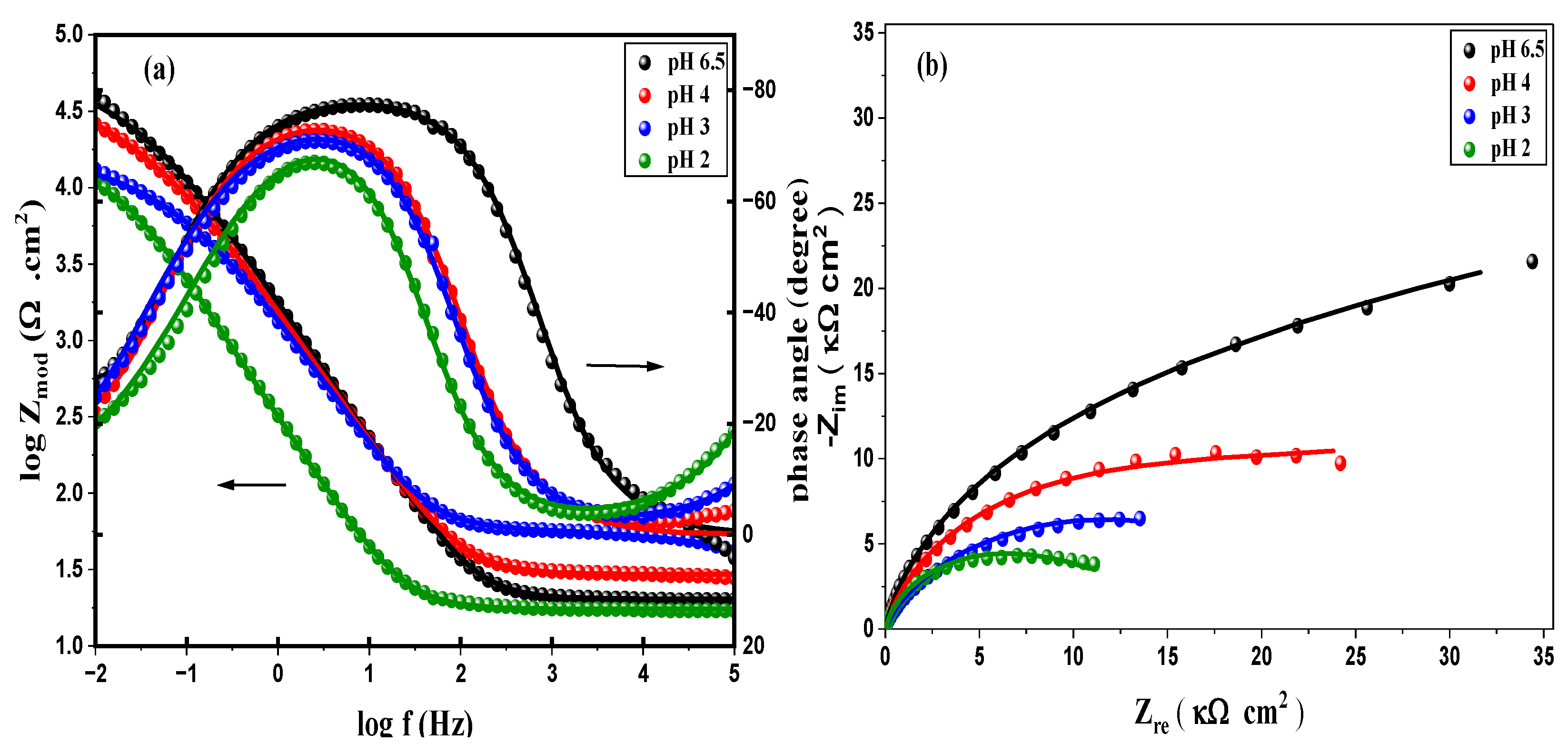

3.4.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

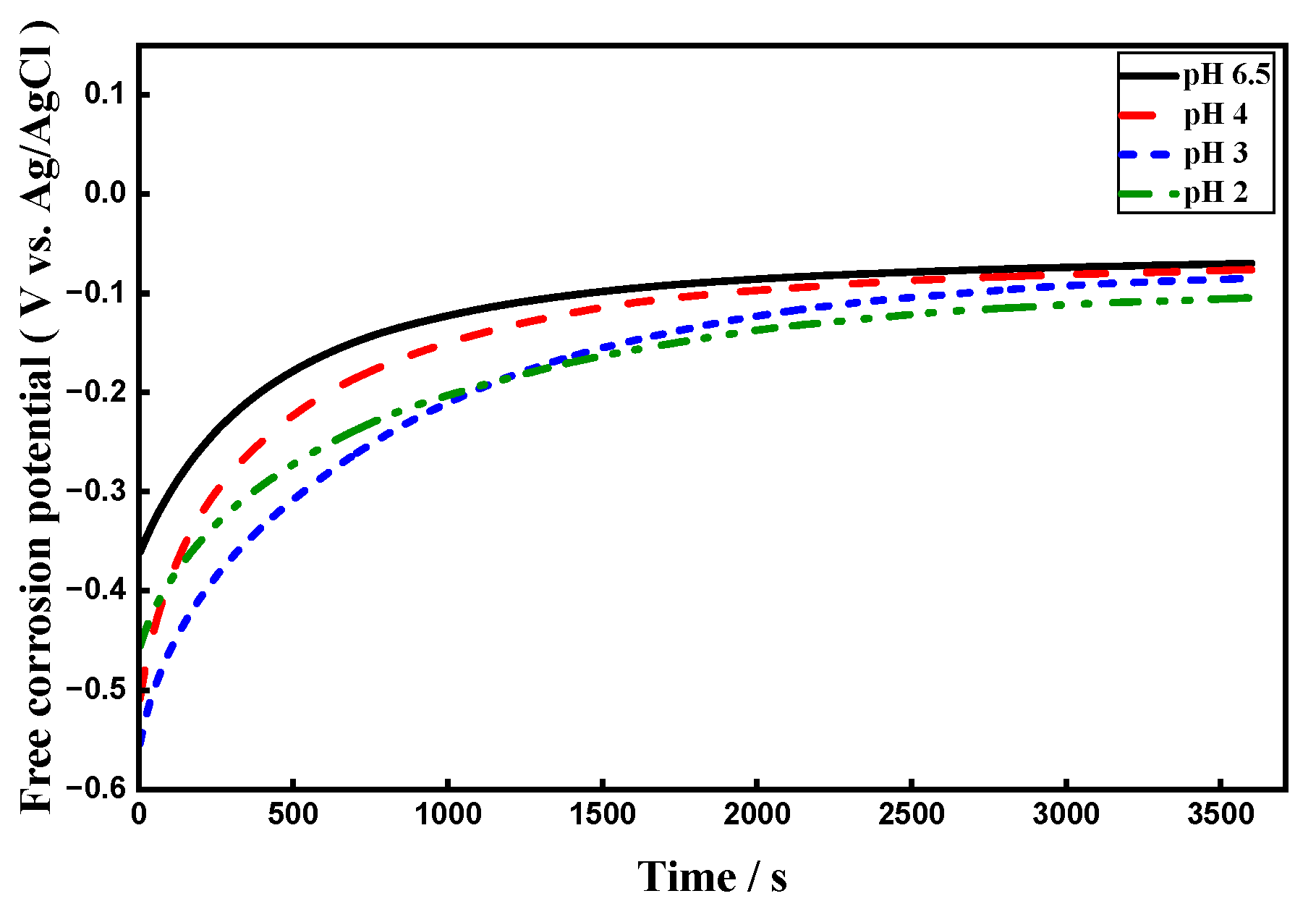

3.4.3. OCP Assessments

3.5. F- Ion Concentration’s Effect

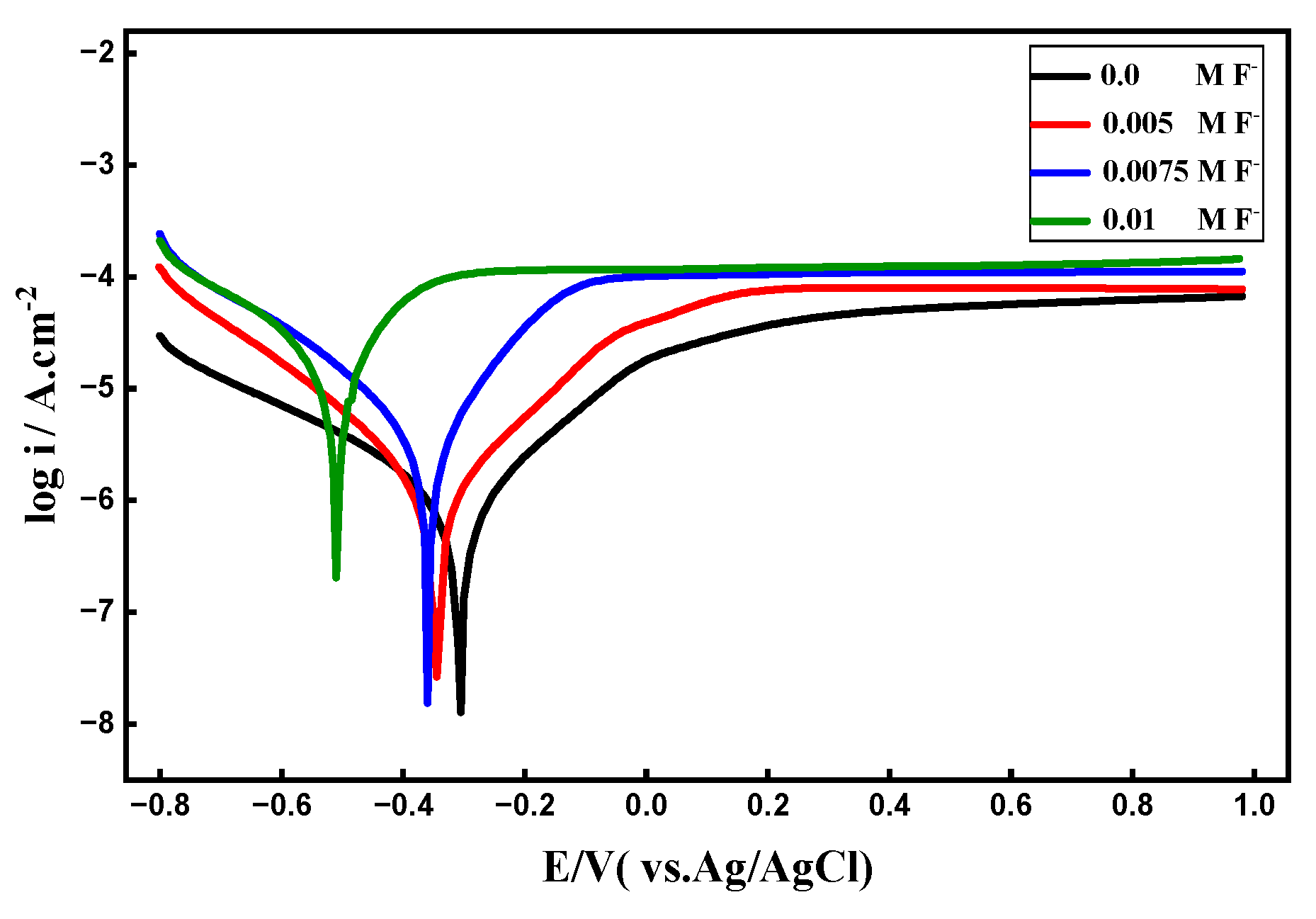

3.5.1. PDP Curves

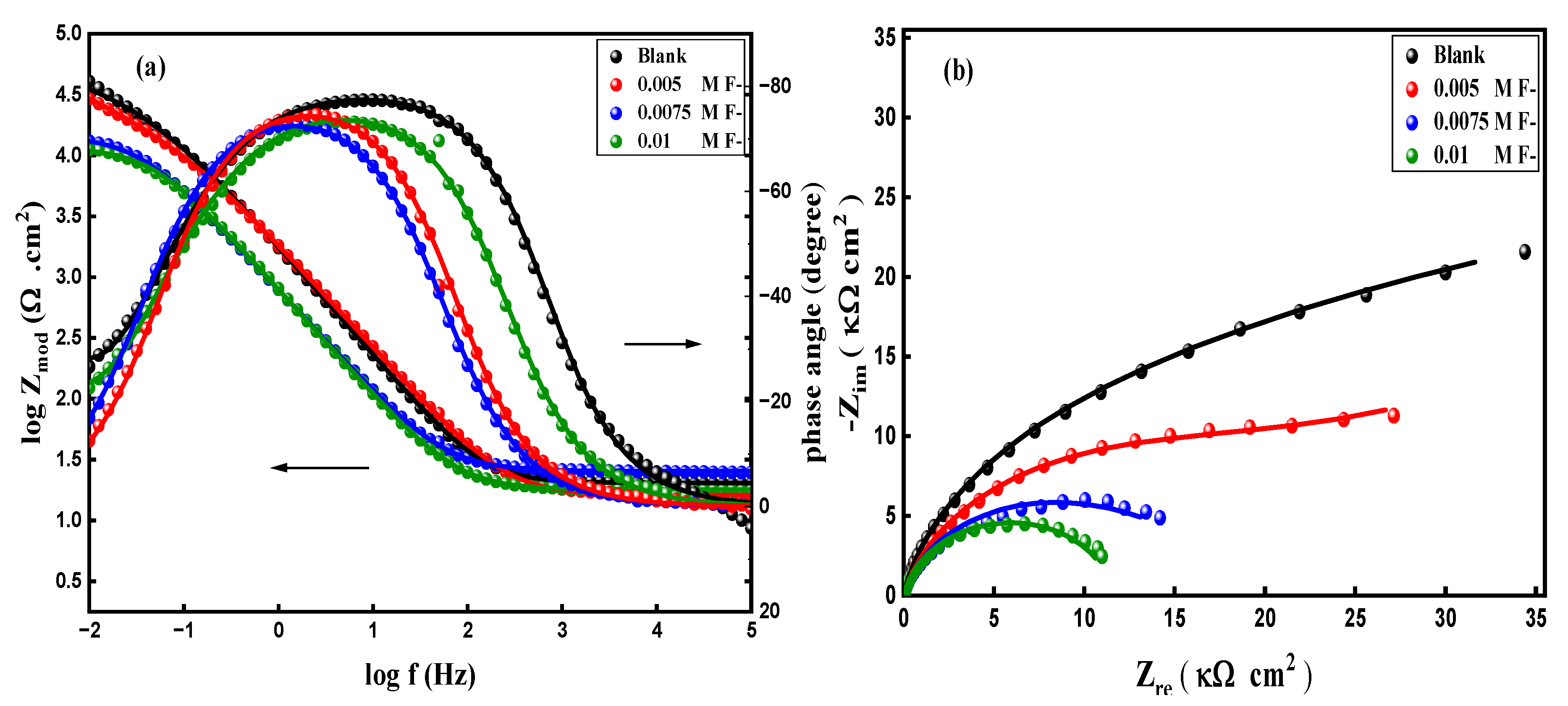

3.5.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

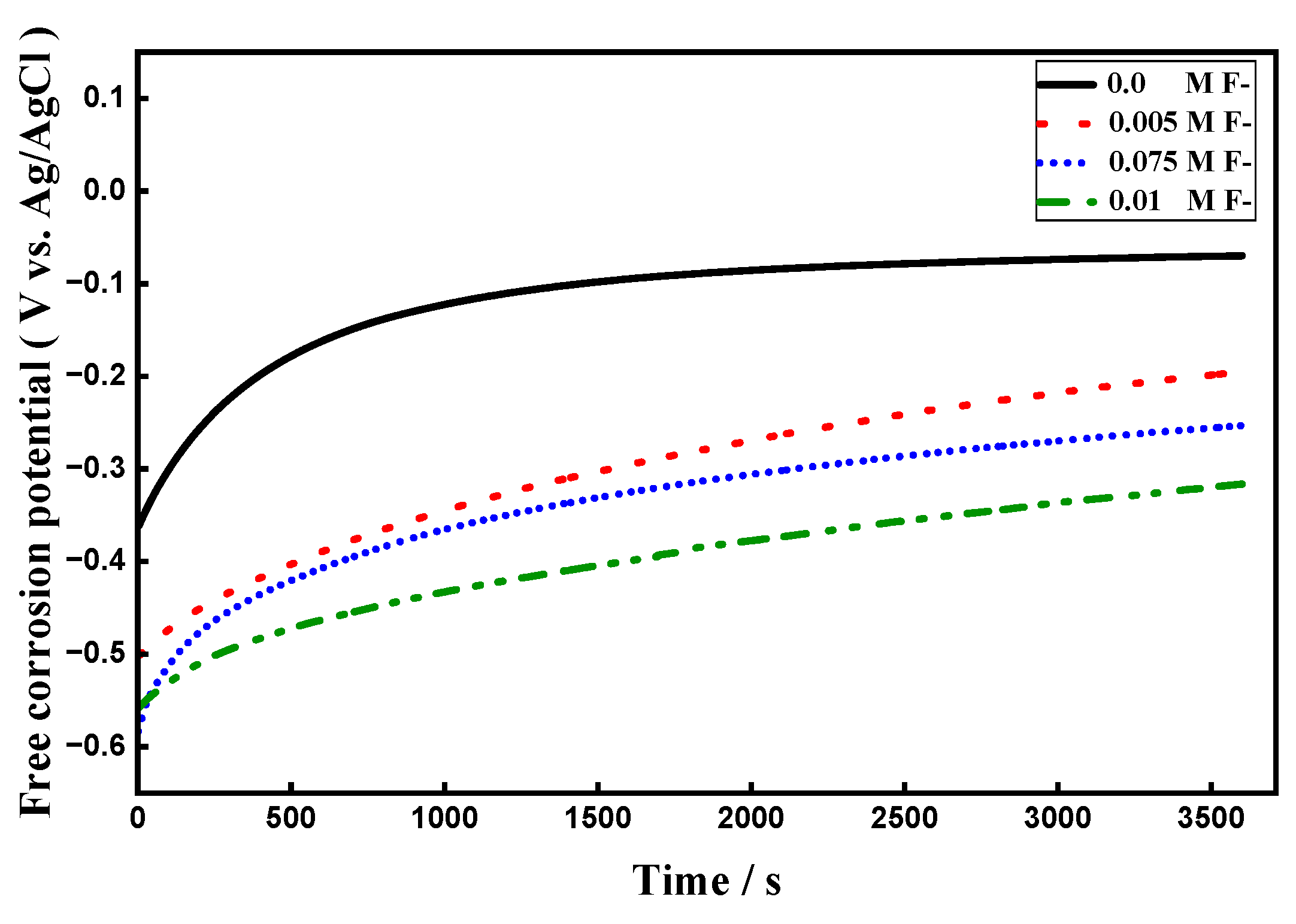

3.5.3. OCP Measurements

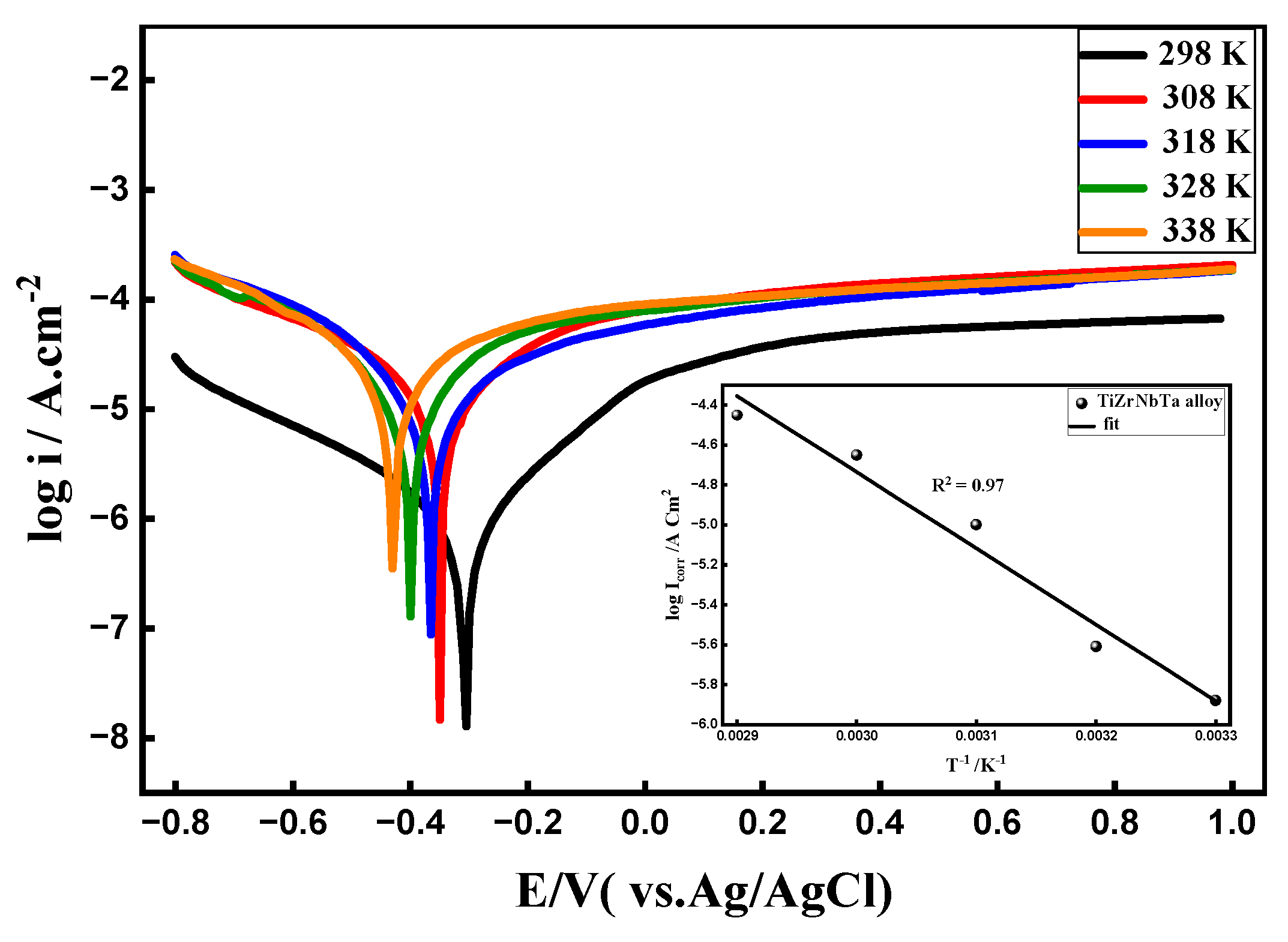

3.6. Effect of Temperature

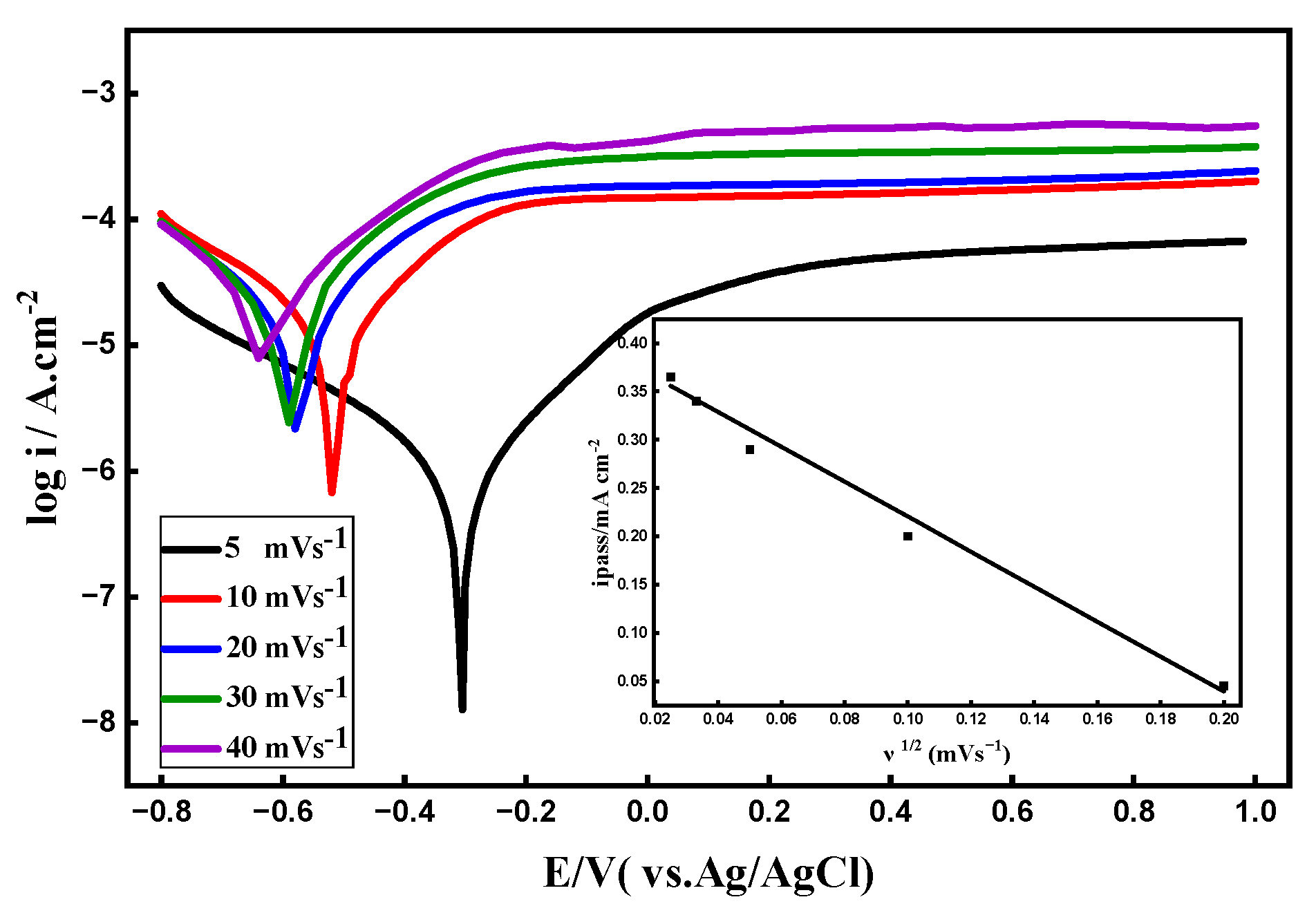

3.7. Potential Scan Rate’s Impact

3.8. Effect of Immersion Time

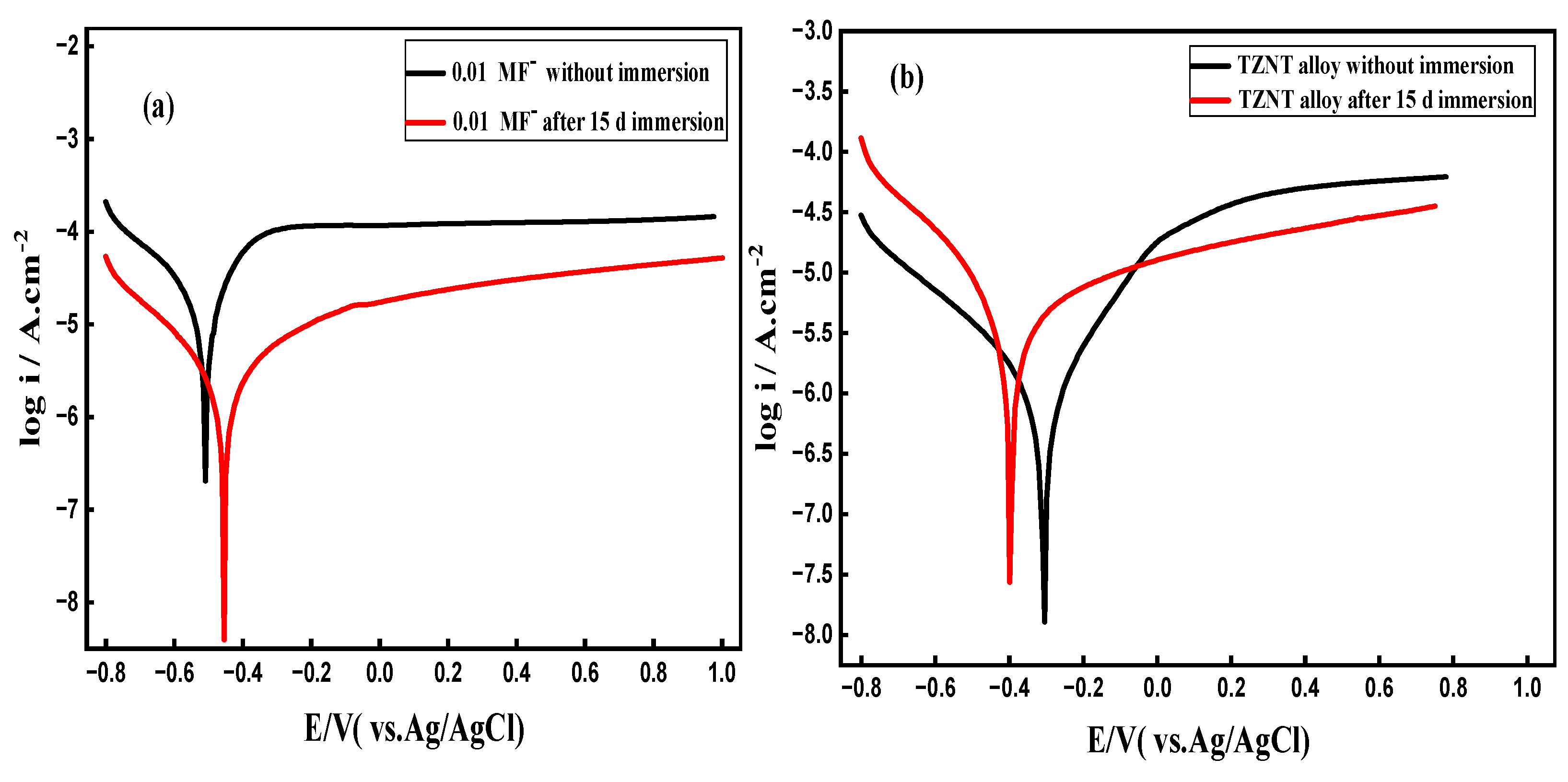

3.8.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization (PDP) Curves

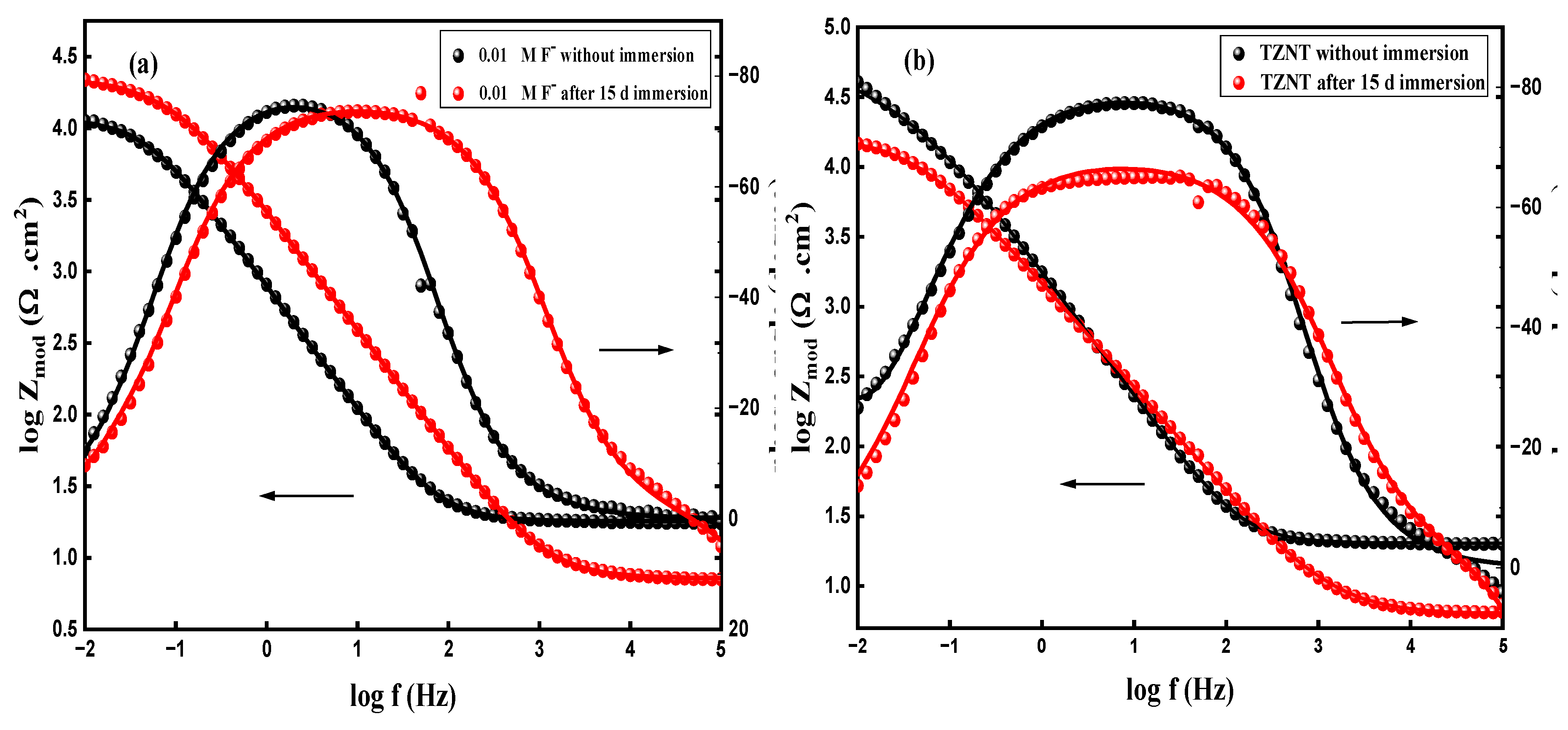

3.8.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

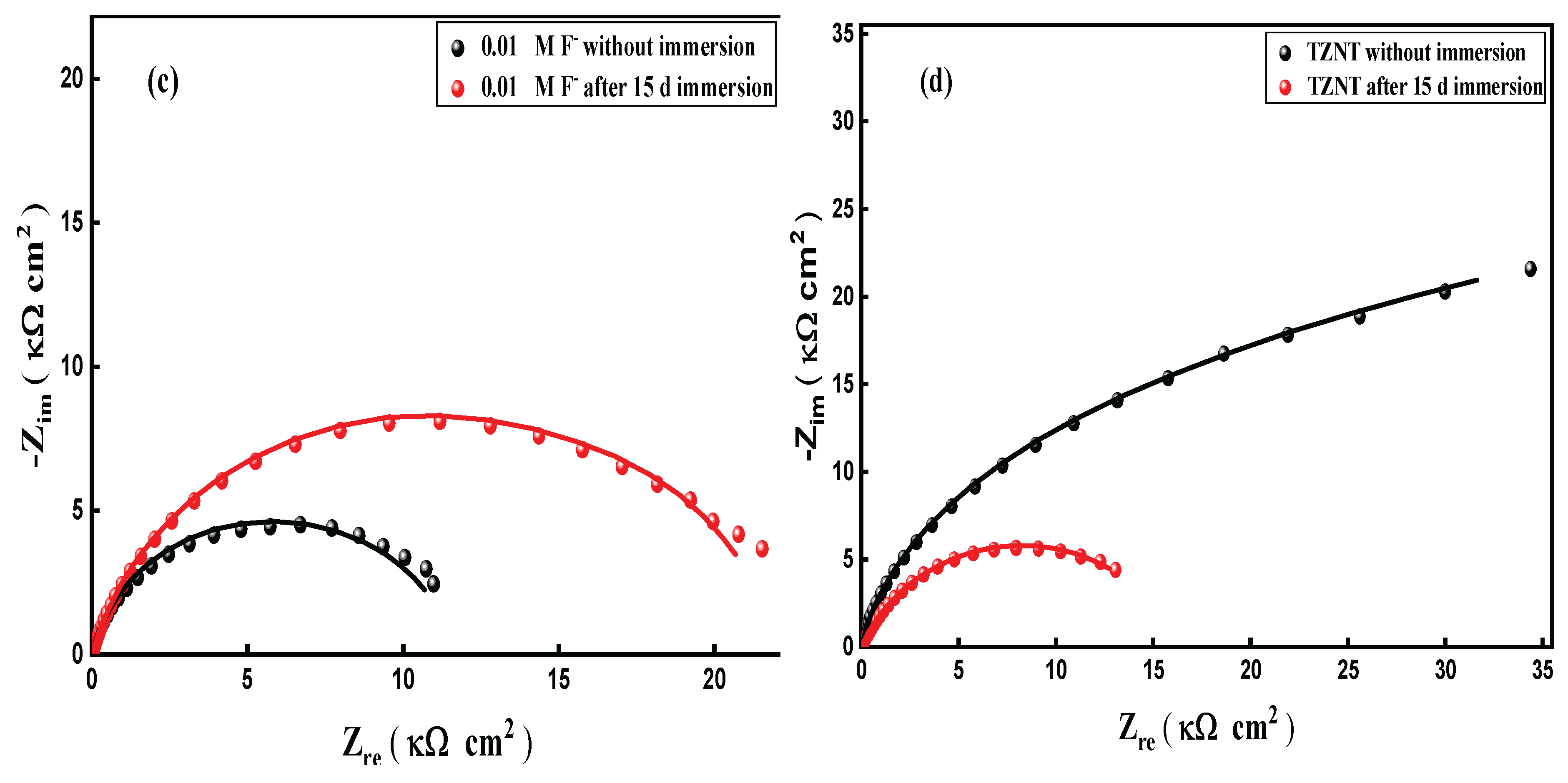

3.9. Surface Characterization

3.9.1. Surface Morphology

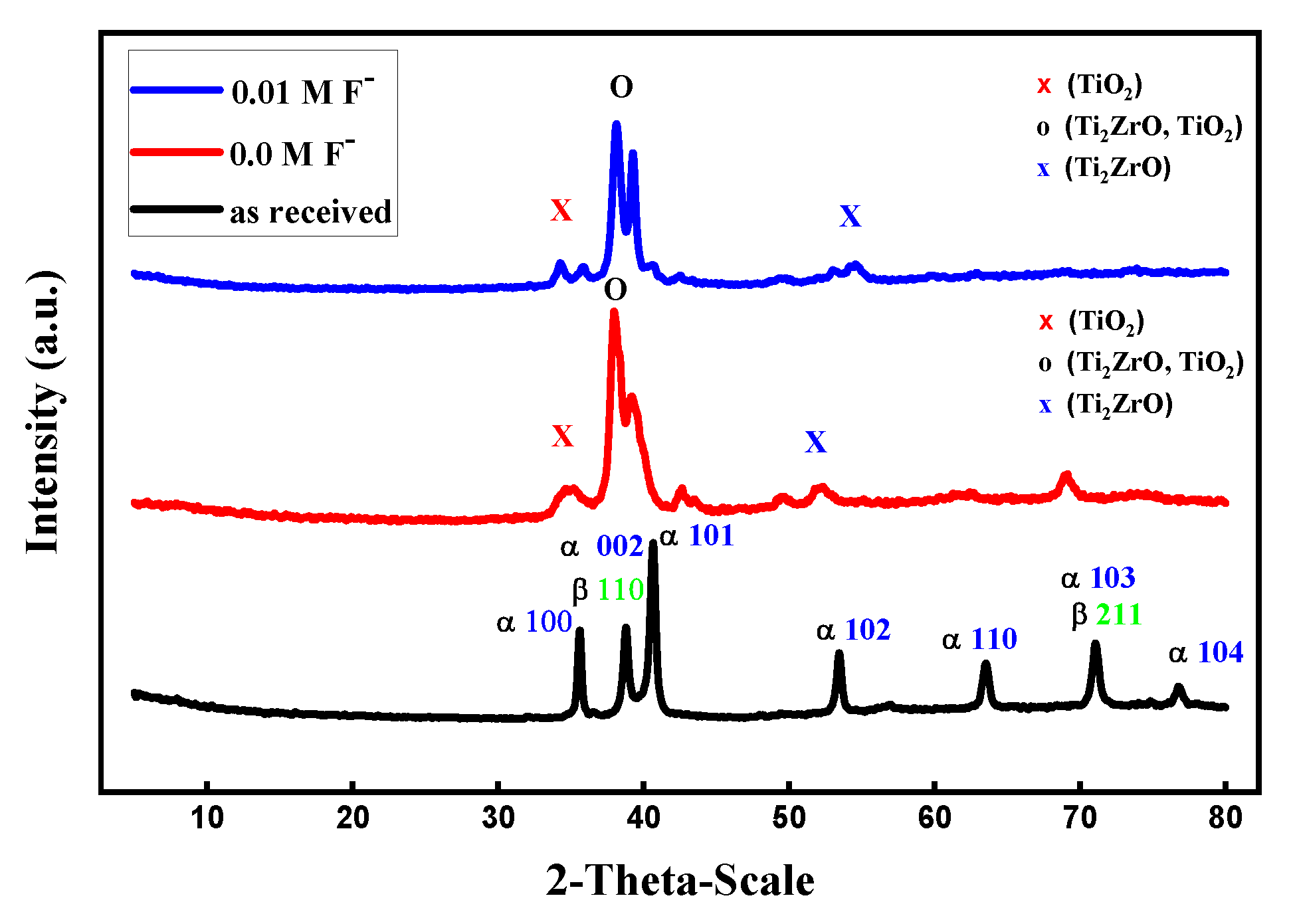

3.9.2. X-ray Diffraction

4. Conclusions

- Superior baseline corrosion resistance: As demonstrated by lower corrosion current densities, higher polarization resistance, and more noble OCP values, the β-TZNT alloy demonstrated significantly greater corrosion resistance than commercially pure titanium in fluoride-free artificial seawater at near-neutral pH. The development of a stable passive film enriched with oxides based on Nb, Zr, and Ta is responsible for this improved performance.

- pH-dependent passive-film stability: The corrosion rate significantly increased, and the passive-film resistance decreased as the seawater environment became more acidic. Even at low pH, passivity was preserved, but the oxide layer's protective effectiveness significantly declined because of faster chemical dissolution.

- Detrimental role of fluoride ions: The integrity of the passive film was seriously jeopardized by fluoride ions, which led to notable decreases in impedance parameters and increases in corrosion current density. The main mechanism for passive-film breakdown was found to be the formation of soluble titanium-fluoride complexes and HF/HF₂⁻ species.

- Bilayer passive-film structure: The passive film on the β-TZNT alloy is made up of an outer porous layer and an inner compact barrier layer, according to EIS analysis. The resistance and thickness of both layers were decreased by increasing fluoride concentration, lowering pH, and raising temperatures, which eventually caused film destabilization.

- Effects of temperature, scan rate, and immersion time: With an apparent activation energy of about 31.75 kJ mol⁻¹, higher temperatures accelerated corrosion processes and decreased passive-film stability. Diffusion-controlled oxide growth was demonstrated by the dependence of passive current density on the square root of scan rate. In fluoride-containing media, prolonged immersion encouraged film stabilization; however, in fluoride-free seawater, it caused gradual degradation.

- Surface and structural confirmation: While XRD analysis revealed partial amorphization of the passive layer after fluoride-induced attack, SEM observations supported electrochemical findings, showing severe surface degradation in fluoride-containing environments.

- In conclusion, the β-TZNT alloy exhibits outstanding resistance to corrosion in typical seawater settings, but it is extremely vulnerable to fluoride-induced deterioration, especially in acidic and hot conditions. The safe application of β-TZNT alloys in marine, offshore, and desalination systems exposed to fluoride-contaminated seawater is made possible by these findings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nahiduzzaman; Ji, X. Tribocorrosion of Titanium Alloys in Seawater: Recent Advances and Strategies. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2025, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, F.; Adkins, J.; Corradi, M. A Review of the Use of Titanium for Reinforcement of Masonry Structures. Materials 2022, 15, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrsalović, L.; Gudić, S.; Talijančić, A.; Jakić, J.; Krolo, J.; Danaee, I. Corrosion Behavior of Ti and Ti6Al4V Alloy in Brackish Water, Seawater, and Seawater Bittern. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbati-Sarraf, H.; Ding, L.; Khakpour, I.; Daviran, G.; Poursaee, A. Unraveling the Corrosion of the Ti–6Al–4V Orthopedic Alloy in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) Solution: Influence of Frequency and Potential. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudić, S.; Vrsalović, L.; Kvrgić, D.; Nagode, A. Electrochemical Behaviour of Ti and Ti-6Al-4V Alloy in Phosphate Buffered Saline Solution. Materials 2021, 14, 7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, I.M.A.; Elshamy, I.H.; Halim, S.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.M. Electrochemical and Computational Analyses of Thiocolchicoside as a New Corrosion Inhibitor for Biomedical Ti6Al4V Alloy in Saline Solution: DFT, NBO, and MD Approaches. Surfaces 2025, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Elshamy, I.H.; I Elshamy, M.; Elaraby, A. An experimental and computational investigation on the performance of cefotaxime in mitigating Ti6Al4V alloy corrosion. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H. Effect of hydrogen charging on microstructural evolution and corrosion behavior of Ti-4Al-2V-1Mo-1Fe alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 60, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Lin, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Guo, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, W. Performance of different microstructure on electrochemical behaviors of laser solid formed Ti–6Al–4V alloy in NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2021, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, L.; Fan, L.; Zhong, M.; Cheng, L.; Cui, Z. Understanding the effect of fluoride on corrosion behavior of pure titanium in different acids. Corros. Sci. 2021, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boraei, N.F.E. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of β-Ti alloy in a physiological saline solution and the impact of H2O2 and albumin. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2024, 28(7), 2243–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Pongkao, D.; Yoshimura, M. The electrochemical behavior and characterization of the anodic oxide film formed on titanium in NaOH solutions. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2001, 6, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Zheng, Y. Synergistic effects of fluoride and chloride on general corrosion behavior of AISI 316 stainless steel and pure titanium in H2SO4 solutions. Corros. Sci. 2018, 130, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Man, C.; Dong, C.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Kong, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. The corrosion behavior of Ti6Al4V fabricated by selective laser melting in the artificial saliva with different fluoride concentrations and pH values. Corros. Sci. 2021, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshamy, I.H.; Ibrahim, M.A.M.; Rehim, S.S.A.; El Boraei, N.F. Electrochemical Characteristics of a Biomedical Ti70Zr20Nb7.5Ta2.5 Refractory High Entropy Alloy in an Artificial Saliva Solution. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2022, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhong, M.; Ge, F.; Gao, H.; Man, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Electrochemical Behavior and Surface Characteristics of Pure Titanium during Corrosion in Simulated Desulfurized Flue Gas Condensates. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, C542–C561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Du, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Xiong, J.; Li, S. Effect of fluoride ions on corrosion behaviour of commercial pure titanium in artificial seawater environment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Liu, C.; Zheng, Y. The effect of fluoride ions on the corrosion behavior of pure titanium in 0.05M sulfuric acid. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 135, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, W.; Grande, A.P. The influence of hydrofluoric acid and fluoride ion on the corrosion and passive behaviour of titanium. Electrochimica Acta 1987, 32, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, E.; Goetz-Grandmont, G. The behaviour of titanium in nitric-hydrofluoric acid solutions. Corros. Sci. 1990, 30, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, M.A.; Elshamy, I.H.; Ibrahim, M.A.M. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of Ti37Al Alloy in Simulated Artificial Seawater Environment and the Impact of Fluoride Ions and pH Values. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2024, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorhallsson, A.I.; Karlsdottir, S.N. Corrosion Behaviour of Titanium Alloy and Carbon Steel in a High-Temperature, Single and Mixed-Phase, Simulated Geothermal Environment Containing H2S, CO2 and HCl. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2021, 2, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; El Rehim, S.A.; Hamza, M. Corrosion behavior of some austenitic stainless steels in chloride environments. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 115, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, D.; Noël, J.; Annamalai, V. 10-corrosion of titanium and its alloys. In Shreir’s corrosion; Elsevier: Oxford, 2010; pp. 2042–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, A.; Meirelis, J.P. Influence of fluoride concentration and pH on corrosion behavior of titanium in artificial saliva. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2007, 37, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Chen, L.-Y.; Wang, L. Surface modification of titanium and titanium alloys: technologies, developments, and future interests. Advanced Engineering Materials 2020, 22(5), 1901258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladescu, A.; Braic, V.; Balaceanu, M.; Braic, M.; Parau, A.C.; Ivanescu, S.; Fanara, C. Characterization of the Ti-10Nb-10Zr-5Ta Alloy for Biomedical Applications. Part 1: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2013, 22, 2389–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard, A. D1141-98: Standard Practice for the Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vitelaru, C. Corrosion behaviour of Ti6Al4V alloy in artificial saliva solution with fluoride content and low pH value: Korrosionsverhalten der Legierung Ti6Al4V in künstlicher Speichelflüssigkeit mit Fluoridanteilen und geringem pH-Wert. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 2014, 45(2), 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, C.K.; Leach, J.S.L. Reversible Optical Changes Within Anodic Oxide Films on Titanium and Niobium. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1978, 125, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, A.S.; El-Shenawy, E.; El-Bitar, T. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study of the Corrosion Behavior of Some Niobium Bearing Stainless Steels in 3.5% NaCl. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2006, 1, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, F. The interaction of bacteria and metal surfaces. Electrochimica Acta 2007, 52, 7670–7680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, A.; Meirelis, J.P. EIS study of Ti–23Ta alloy in artificial saliva. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidia, B.; Nicoleta, S. Impact of hydrogen peroxide and albumin on the corrosion behavior of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) in saline solution. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2021, 16(2), 210244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, D.; Peter, L.; Williams, D. Stability and open circuit breakdown of the passive oxide film on titanium. Electrochimica Acta 1988, 33, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y.; Scully, J.R. Corrosion and Passivity of Ti-13% Nb-13% Zr in Comparison to Other Biomedical Implant Alloys. Corrosion 1997, 53, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, Y.; Dong, K.; Han, E.-H. Research progress on the corrosion behavior of titanium alloys. Corros. Rev. 2022, 41, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabilleau, G.; Bourdon, S.; Joly-Guillou, M.; Filmon, R.; Baslé, M.; Chappard, D. Influence of fluoride, hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid on the corrosion resistance of commercially pure titanium. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Mirza-Rosca, J. Study of the corrosion behavior of titanium and some of its alloys for biomedical and dental implant applications. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999, 471, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, S.L.; Wolynec, S.; Costa, I. Corrosion characterization of titanium alloys by electrochemical techniques. Electrochimica Acta 2006, 51, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira, L. Initiation and growth of self-organized TiO2 nanotubes anodically formed in NH4F∕(NH4) 2SO4 electrolytes. Journal of the Electrochemical Society 2005, 152(10), p. B405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-P.; Lee, J.-T.; Tsai, W.-T. Passivation of titanium in molybdate-containing sulphuric acid solution. Electrochimica Acta 1991, 36, 2069–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, A.; Meirelis, J.P. Influence of fluoride concentration and pH on corrosion behavior of titanium in artificial saliva. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2007, 37, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavos-Valereto, I.C.; Wolynec, S.; Ramires, I.; Guastaldi, A.C.; Costa, I. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy characterization of passive film formed on implant Ti–6Al–7Nb alloy in Hank's solution. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Thierry, D.; Leygraf, C. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of the passive oxide film on titanium for implant application. Electrochimica Acta 1996, 41, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattarin, S.; Musiani, M.; Tribollet, B. Nb electrodissolution in acid fluoride medium: steady-state and impedance investigations. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2002, 149(10), p. B457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frateur, I.; Cattarin, S.; Musiani, M.; Tribollet, B. Electrodissolution of Ti and p-Si in acidic fluoride media: formation ratio of oxide layers from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2000, 482, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, P. Modifications of Passive Films; CRC Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- El Rehim, S.S.A.; Hassan, H.H.; Ibrahim, M.A.M.; Amin, M.A. Electrochemical Behaviour of a Silver Electrode in NaOH Solutions. Monatshefte Fuer Chemie/chemical Mon. 1998, 129, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshamy, I.H.; El Rehim, S.S.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.M.; El Boraei, N.F. The bifunctional role played by thiocyanate anions on the active dissolution and the passive film of titanium in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boraei, N.F.; Ibrahim, M.A.M. Comparative study on the corrosion behaviour of Lord Razor Blade Steel (LRBS) in aqueous environments. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2020, 14, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, R.G.; Belinko, K.; Ambrose, J. Electrochemical Behavior of the Lead Electrode in HCl and NaCl Aqueous Electrolytes. Can. J. Chem. 1975, 53, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, V.; Villullas, H.; Teijelo, M.L. Potentiodynamic growth of anodic silver chromate layers. Electrochimica Acta 1999, 44, 4693–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boraei, N.F. The Effect of Annealing Temperature and Immersion Time on the Active–Passive Dissolution of Biomedical Ti70Zr20Nb7. 5Ta2. 5 Alloy in Ringer’s Solution. Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion 2023, 9(3), p. 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, G.; Mahdjoub, H.; Meunier, C. A study of the corrosion behaviour and protective quality of sputtered chromium nitride coatings. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2000, 126, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

-Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate mpy |

Rp (k Ω cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti |

6.26 x10-6 | 0.399 | 0.687 | 0.408 | 0.470 | 0.080 | 0.408 | 17.75 |

| TZNT alloy | 1.30 x10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.168 | 52.47 |

| Materials | Rs (Ω cm2) |

Rb (kΩ cm2) |

CPEb (F cm2 HZ1-n1) |

n 1 |

Rp (Ω cm2) |

CPEp (F cm2 HZ1-n2) |

n 2 |

Rp (kΩ cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti |

2.52 | 19.11 | 237.4x10-6 | 0.803 | 66.48 | 18.85x10-6 | 0.798 | 19.17 |

| TZNT alloy | 20.13 | 50.80 | 106.7x10-6 | 0..889 | 14.25 | 251.3x10-6 | 0.766 | 50.81 |

| pH | ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

-Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate Mpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.5 | 1.30x10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.168 |

| 4.0 | 4.66x10-6 | 0.378 | 0.175 | 0.296 | 0.0.34 | 0.080 | 0.600 |

| 3.0 | 8.89x10-6 | 0.429 | 0.143 | 0.204 | -0.179 | 0.085 | 1.145 |

| 2.0 | 4.14x10-5 | 0.454 | 0.345 | 0.312 | -0.129 | 0.089 | 5.334 |

| pH | Rs (Ω cm2) |

Rb (kΩ cm2) |

CPEb (F cm2 HZ1-n1) |

n 1 |

Rp (Ω cm2) |

CPEp (F cm2 HZ1-n2) |

n 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.5 | 20.13 | 50.80 | 106.7x10-6 | 0..889 | 14.25 | 251.3x10-6 | 0.766 |

| 4.0 | 28.95 | 26.65 | 146.3x10-6 | 0.840 | 62.90 | 345.8x10-6 | 0.699 |

| 3.0 | 44.35 | 19.07 | 189.4x10-6 | 0.832 | 29.07 | 410.2x10-6 | 0.915 |

| 2.0 | 24.11 | 12.63 | 281.0x10-6 | 0.820 | 16.14 | 476.1x10-6 | 0.862 |

| F- / M | ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate Mpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.30 x10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.168 |

| 0.005 | 2.59 x10-6 | 0.341 | 0.220 | 0.267 | 0.130 | 0.076 | 0.336 |

| 0.0075 | 3.59 x10-6 | 0.360 | 0.159 | 0.219 | 0.040 | 0.103 | 0.463 |

| 0.01 | 4.76 x10-5 | 0.557 | 0.279 | 0.582 | -0.239 | 0.142 | 6.129 |

| F- / M | Rs (Ω cm2) |

Rb (kΩ cm2) |

CPEb (F cm2 HZ1-n1) |

n 1 |

Rp (Ω cm2) |

CPEp (F cm2 HZ1-n2) |

n 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 20.13 | 50.80 | 106.7x10-6 | 0..889 | 14.25 | 251.3x10-6 | 0.766 |

| 0.005 | 15.76 | 27.50 | 178.3x10-6 | 0.768 | 59.12 | 389.1x10-6 | 0.836 |

| 0.0075 | 31.25 | 14.41 | 193.5x10-6 | 0.840 | 64.12 | 364.2x10-6 | 0.993 |

| 0.01 | 17.82 | 9.701 | 221.3x10-6 | 0.885 | 32.15 | 423.1x10-6 | 0.957 |

| Temperature/ K |

ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate Mpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 1.30x10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.168 |

| 308 | 2.43x10-6 | 0.350 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.090 | 0.085 | 0.313 |

| 318 | 9.79x10-6 | 0.365 | 0.266 | 0.194 | 0.100 | 0.072 | 1.261 |

| 328 | 2.23x10-5 | 0.399 | 0.449 | 0.372 | 0.120 | 0.098 | 2.873 |

| 338 | 3.54x10-5 | 0.430 | 0.703 | 0.340 | 0.130 | 0.094 | 4.559 |

| Scan Rate mVs-1 |

ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate mpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.30x10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.045 | 0.168 |

| 10 | 1.85x10-5 | 0.517 | 0.314 | 0.343 | 0.130 | 0.200 | 2.379 |

| 20 | 3.28x10-5 | 0.574 | 0.391 | 0.532 | 0.140 | 0.290 | 4.231 |

| 30 | 5.41x10-5 | 0.596 | 0.759 | 0.594 | 0.130 | 0.340 | 6.969 |

| 40 | 7.76x10-5 | 0.623 | 0.636 | 0.915 | 0.130 | 0.365 | 10.00 |

| Immersion Time | ICorr A cm-2 |

-ECorr / V |

βa (V dec-1) |

βc (V dec-1) |

-Epass / V |

ipass mA cm-2 |

Corr Rate mpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without F- | |||||||

| 15 days |

3.72 x 10-6 | 0.399 | 0.591 | 0.199 | 0.450 | 0.013 | 0.478 |

| 0.0 | 1.30 x 10-6 | 0.306 | 0.274 | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.168 |

| With F- | |||||||

| 15 days |

5.00x10-6 | 0.455 | 0.681 | 0.409 | 0.210 | 0.024 | 0.643 |

| 0.0 | 4.76x10-5 | 0.557 | 0.279 | 0.582 | -0.239 | 0.142 | 6.129 |

| Immersion Time | Rs (Ω cm2) |

Rb (kΩ cm2) |

CPEb (F cm2 HZ1-n1) |

n 1 |

Rp (Ω cm2) |

CPEp (F cm2 HZ1-n2) |

n 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without F- | |||||||

| 15 days |

23.16 | 15.90 | 135.1x10-6 | 0.875 | 6.23 | 264.5x10-6 | 0.759 |

| 0.0 | 20.13 | 50.80 | 106.7x10-6 | 0..889 | 14.25 | 251.3x10-6 | 0.766 |

| With F- | |||||||

| 15 days |

37.22 | 20.62 | 83.21x10-6 | 0..895 | 35.23 | 278.4x10-6 | 0.722 |

| 0.0 | 17.82 | 9.701 | 221.3x10-6 | 0.885 | 32.15 | 423.1x10-6 | 0.957 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.