Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study aimed to develop a comprehensive typology of Sudanese sorghum-farming households within their food security status to inform targeted agricultural policy and rural development strategies. Using survey data from 392 households across 11 Sudanese states, the research captures the structural, socio-economic, and geographical diversity of farming systems and scrutinizes the relationship between socioeconomic characteristics of farmer households and related probability of constituting a specific farmer type. To assert this, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), hierarchical clustering, and Multinomial logistic regression analysis were applied. Through PCA and hierarchical clustering, three types of farmers were identified: The first type (Vulnerable Farmers), characterized by low education levels, small landholdings, high food insecurity, and reliance on subsistence farming; The second type (Well-off Remote farmers), operating larger landholdings meant for commercial purposes, yet facing challenges related to geographic isolation and limited market access; The third type (Educated Farmers with access to urban areas), consisting of households with higher education, diversified income sources, and proximity to markets, though still experiencing persistent food insecurity. Multinomial logistic regression analysis confirmed that household size, age, education, land size, market distance, and income structure are significant predictors of respective types of farmers. Thus, the study stands as a tool to enlighten intended/future policies, in providing input support and credit for vulnerable farmers, infrastructure and market access for remote commercial farmers, and land tenure security with innovative-geared incentives for farmers interacting with urban areas to foster inclusive, adaptive agricultural policies, and sustainable development across Sudan’s diverse farming communities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

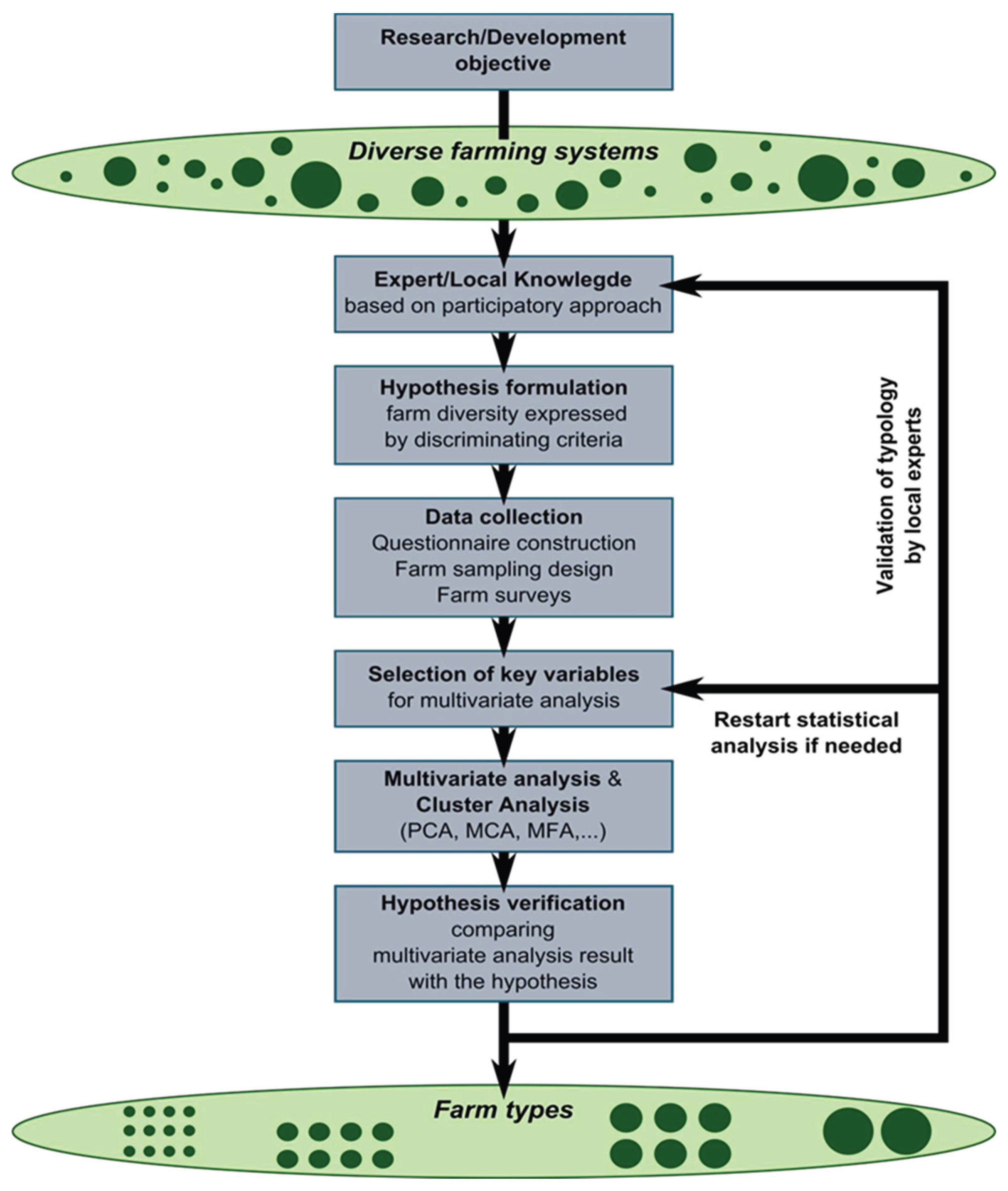

2.1. Theoretical Analytic Concept of Farmer Typology

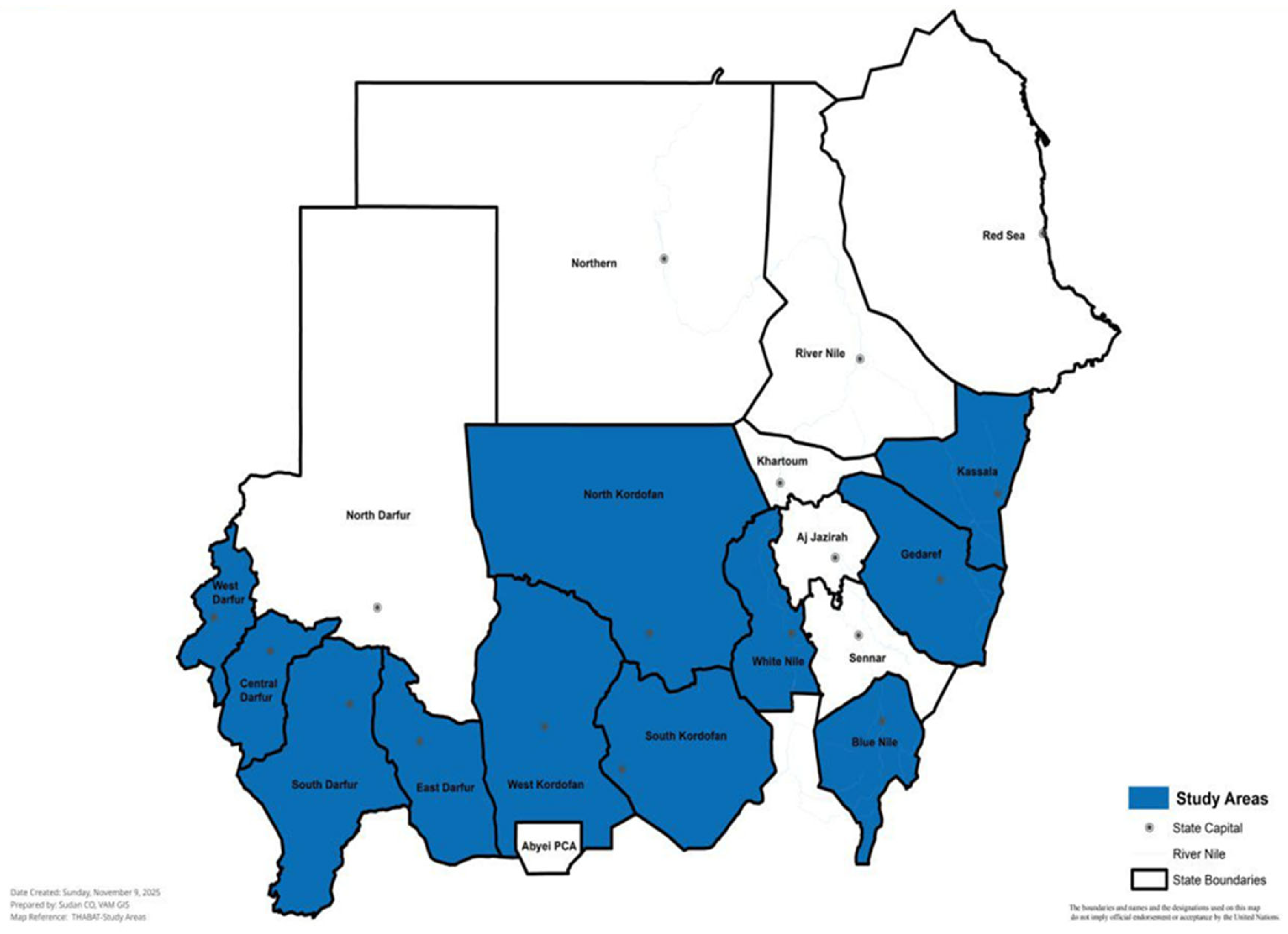

2.2. Study Areas and Sample

2.3. Empirical Model of PCA

2.3. Multinomial Logistic Regression

2.4. Variables and Related Measurements

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

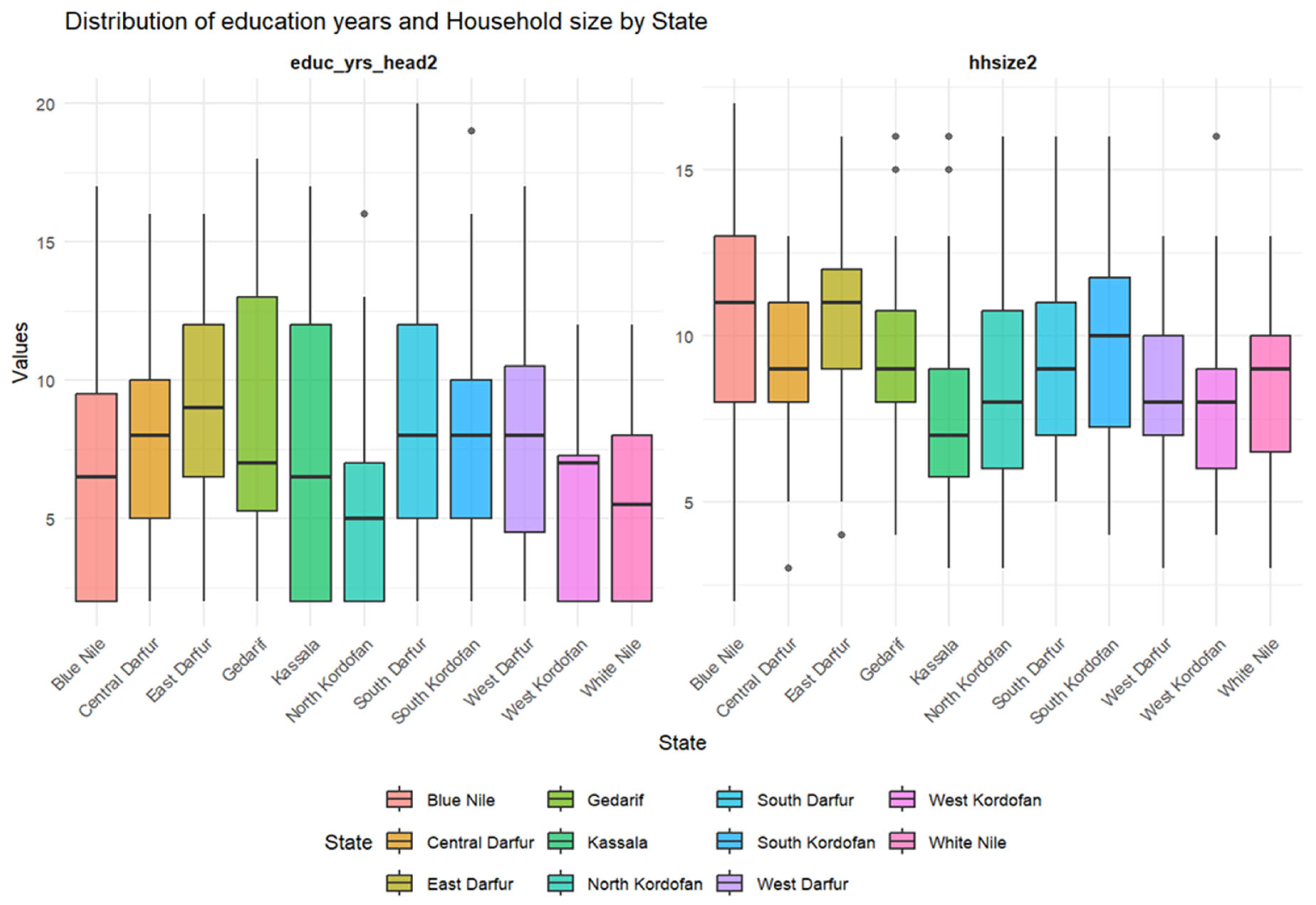

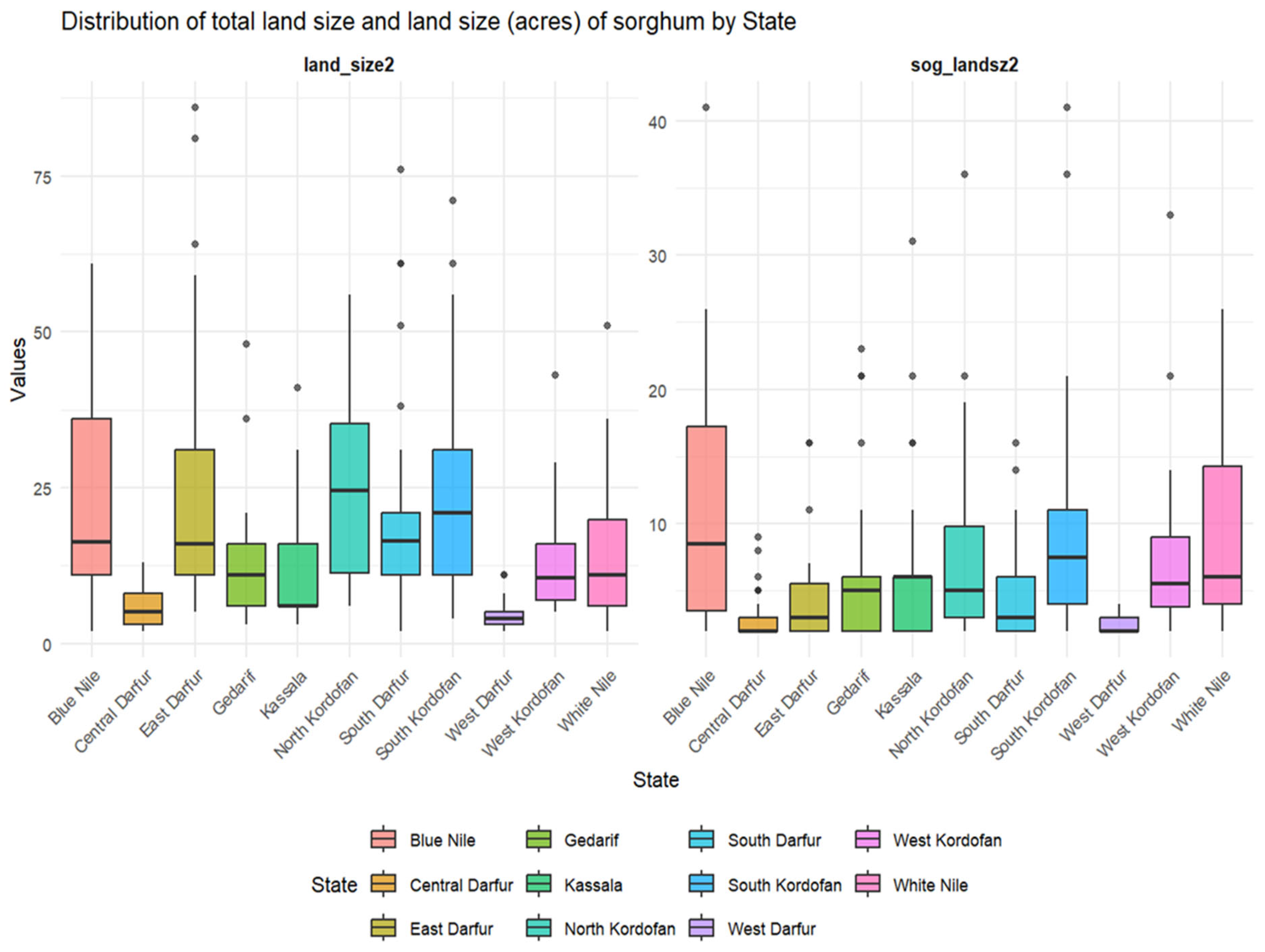

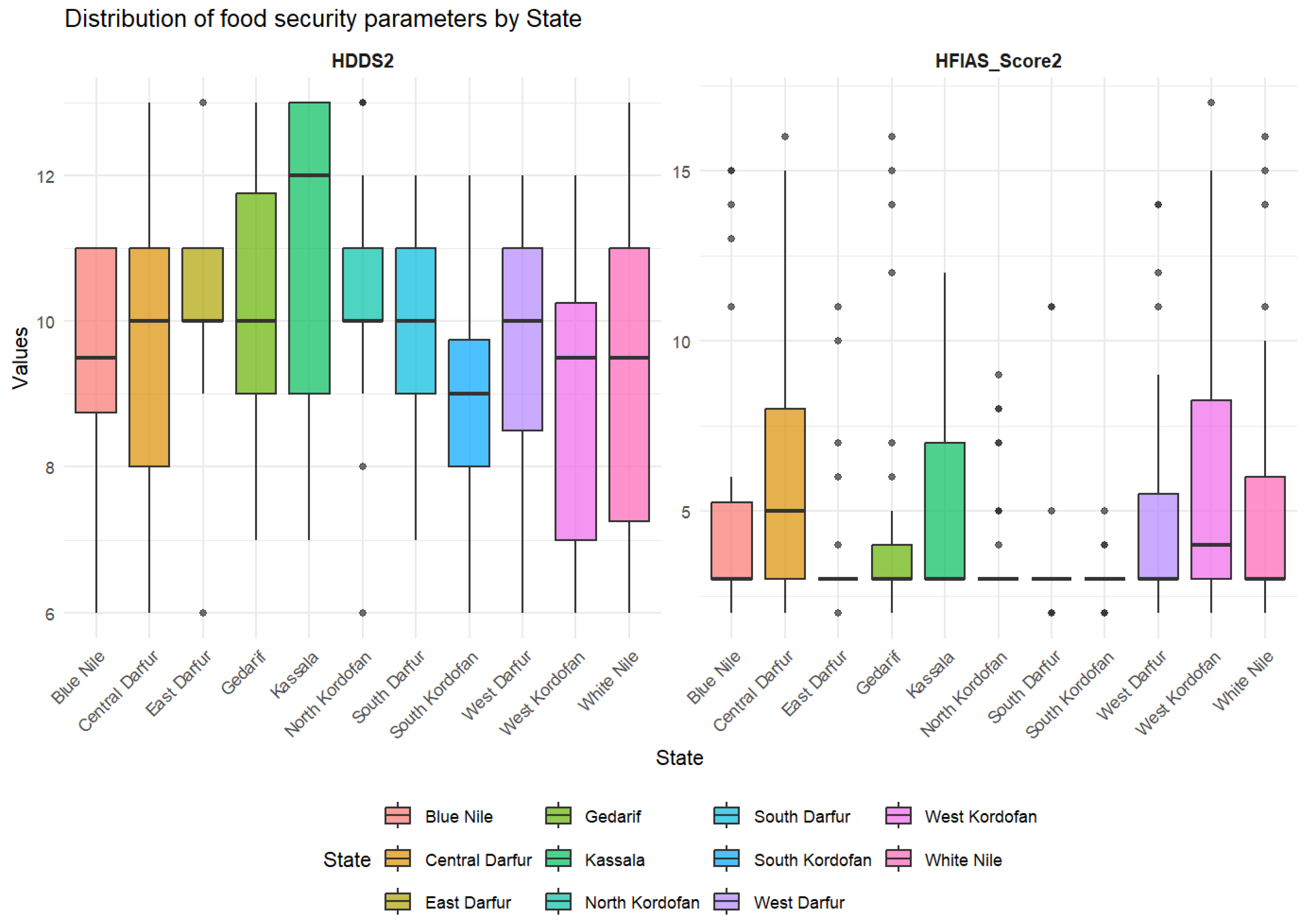

3.1. Cross-States’s Descriptive Statistics

| Variables/States | Blue Nile (N=28) |

Central Darfur (N=41) |

East Darfur (N=27) |

Gedarif (N=38) |

Kassala (N=36) |

North Kordofan (N=38) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hhsize2 | 10.75 (4.05) |

9.15 (2.45) |

10.44 (3.00) |

9.13 (2.517) |

7.639 (3.01) |

8.55 (3.32) |

0.000 |

| age_head2 | 43.79 (10.30) |

47.54 (12.50) |

49.96 (10.63) |

49.42 (11.693) |

54.139 (12.01) |

48.18 (14.35) |

0.167 |

| educ_yrs_head2 | 6.79 (4.49) |

7.59 (3.95) |

9.41 (4.13) |

9.26 (4.914) |

7.083 (5.00) |

5.39 (3.91) |

0.000 |

| dist_mins2 | 67.11 (43.92) |

26.59 (32.29) |

104.89 (24.59) |

43.03 (33.837) |

21.889 (26.98) |

66.66 (42.41) |

0.000 |

| dist_town2 | 41.54 (26.75) |

8.24 (9.88) |

73.48 (21.10) |

21.79 (20.98) |

50.917 (30.18) |

39.18 (22.49) |

0.000 |

| annual_nonAgrInc2 | 346,038.44 (390,794.05) |

365,338.43 (311,799.30) |

528,297.47 (429,543.46) | 427,719.41 (508,879.391) | 183,744.018 (210,204.79) | 425,385.77 (416,092.69) |

0.002 |

| annual_Income2 | 419,286.71 (412,126.88) |

395,412.59 (315,291.23) |

645,350.33 (524,869.78) | 528,101.87 (523,697.576) | 282,142.172 (318,704.49) | 569,124.68 (383,581.32) |

0.000 |

| annual_hhd_exp2 | 550,802.43 (288,538.51) |

619,250.56 (353,319.97) |

1,321,342.93 (605,248.01) | 1,251,717.63 (566,672.480) | 921,200.11 (506,237.29) | 919,954.68 (450,956.41) |

0.000 |

| annual_food_exp2 | 378,373.86 (257,681.56) |

397,338.56 (210,200.39) |

893,689.89 (405,823.69) | 870,417.36 (445,687.607) | 676,749.33 (403,538.94) | 632,565.21 (346,476.56) |

0.000 |

| annual_exp_nonfd2 | 172,429.57 (105,687.25) |

221,913.00 (209,574.79) |

427,654.04 (246,744.54) | 396,802.89 (226,577.384) | 244,451.778 (190,432.59) | 287,390.47 (189,142.34) |

0.000 |

| land_size2 | 23.87 (18.96) |

5.90 (3.25) |

26.57 (22.57) |

12.34 (8.936) |

11.056 (9.17) |

24.71 (14.42) |

0.000 |

| sog_landsz2 | 11.18 (9.68) |

3.00 (1.67) |

4.63 (3.95) |

6.13 (5.639) |

6.389 (6.10) |

7.79 (7.37) |

0.000 |

| labhire_totcost2 | 29,686.62 (131,813.61) |

623.00 (0.00) |

3,480.52 (11,296.56) |

228,839.81 (105,158.25) | 1,333.88 (6,114.84) | 14,713.96 (38,553.45) |

0.000 |

| HDDS2 | 9.29 (1.67) |

9.41 (1.79) |

10.22 (1.25) |

10.03 (1.952) |

11.000 (1.93) |

10.34 (1.36) |

0.000 |

| HFIAS_Score2 | 5.21 (4.16) |

6.29 (4.03) |

3.81 (2.17) |

4.47 (3.57) |

4.972 (2.58) |

3.82 (1.69) |

0.000 |

| unitcst_landrent2 | 3,861.08 (2,871.59) |

9,352.69 (11,940.74) |

8,397.42 (11,506.6) |

9,894.66 (14,904.29) | 5,268.6 (5,159.33) | 5,397.56 (5,847.83) |

0.000 |

| chicken_qnty_tlu2 | 2.05 (0.07) |

2.08 (0.37) |

2.06 (0.08) |

2.01 (0.193) |

2.070 (0.20) |

1.90 (0.26) |

0.007 |

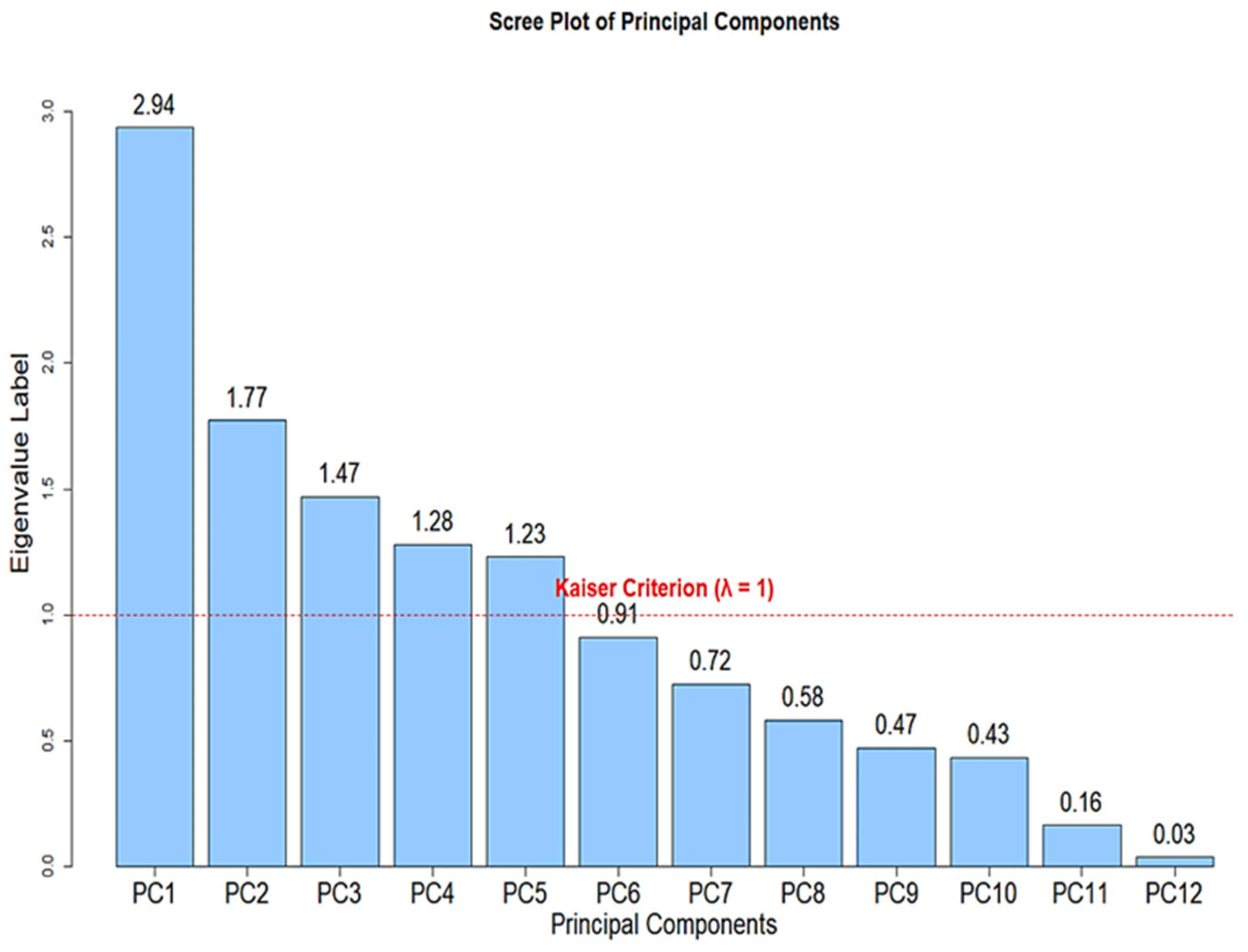

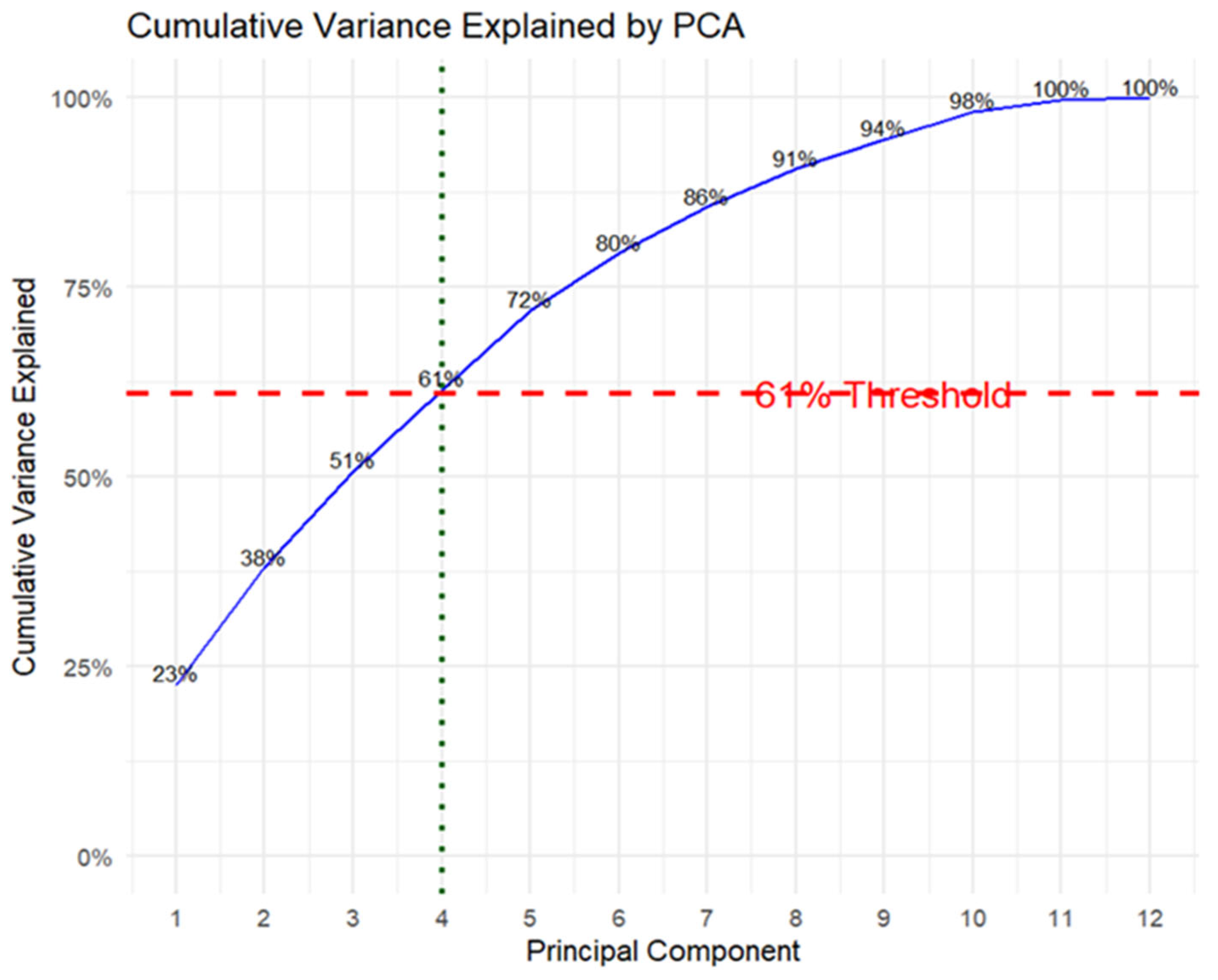

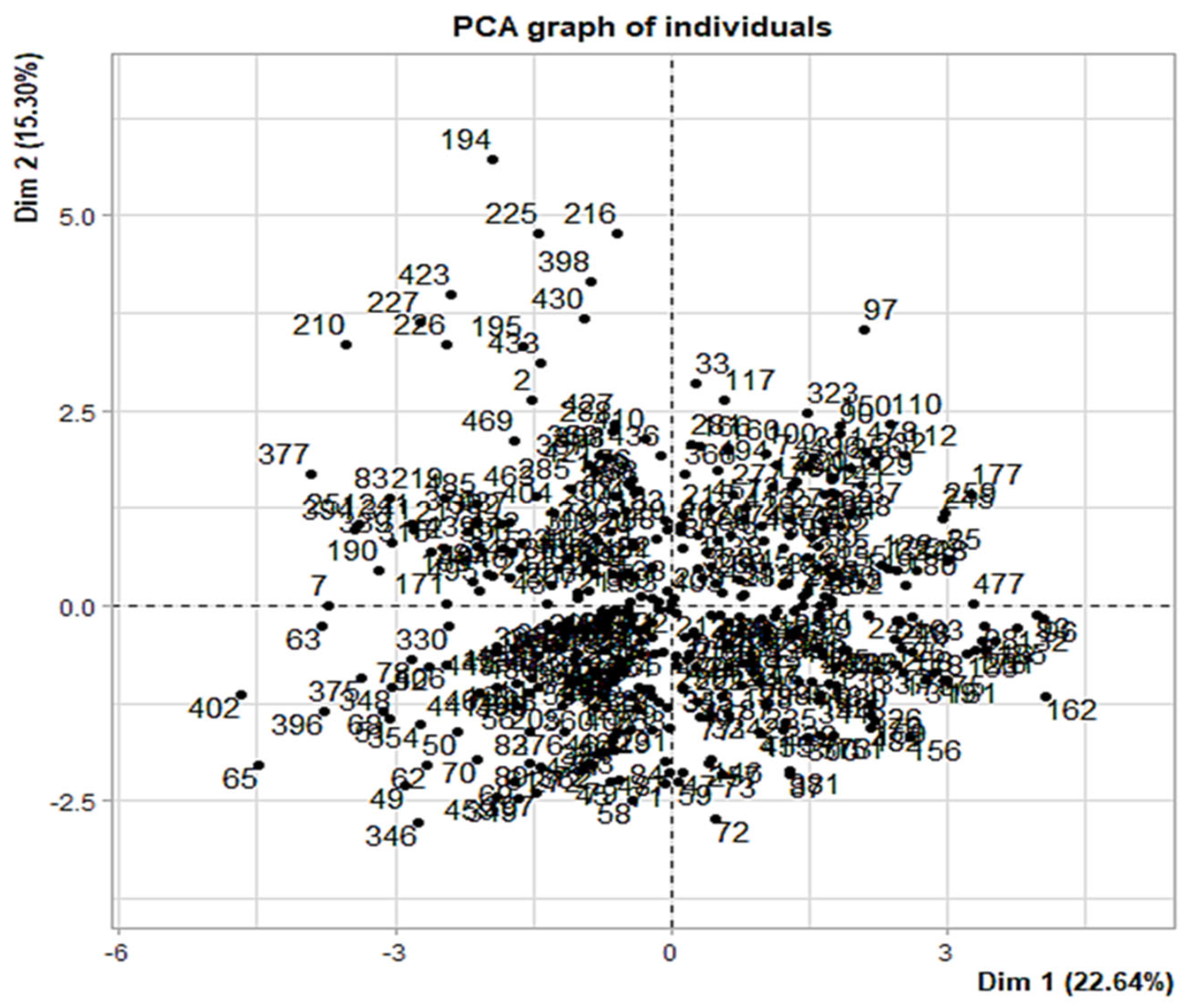

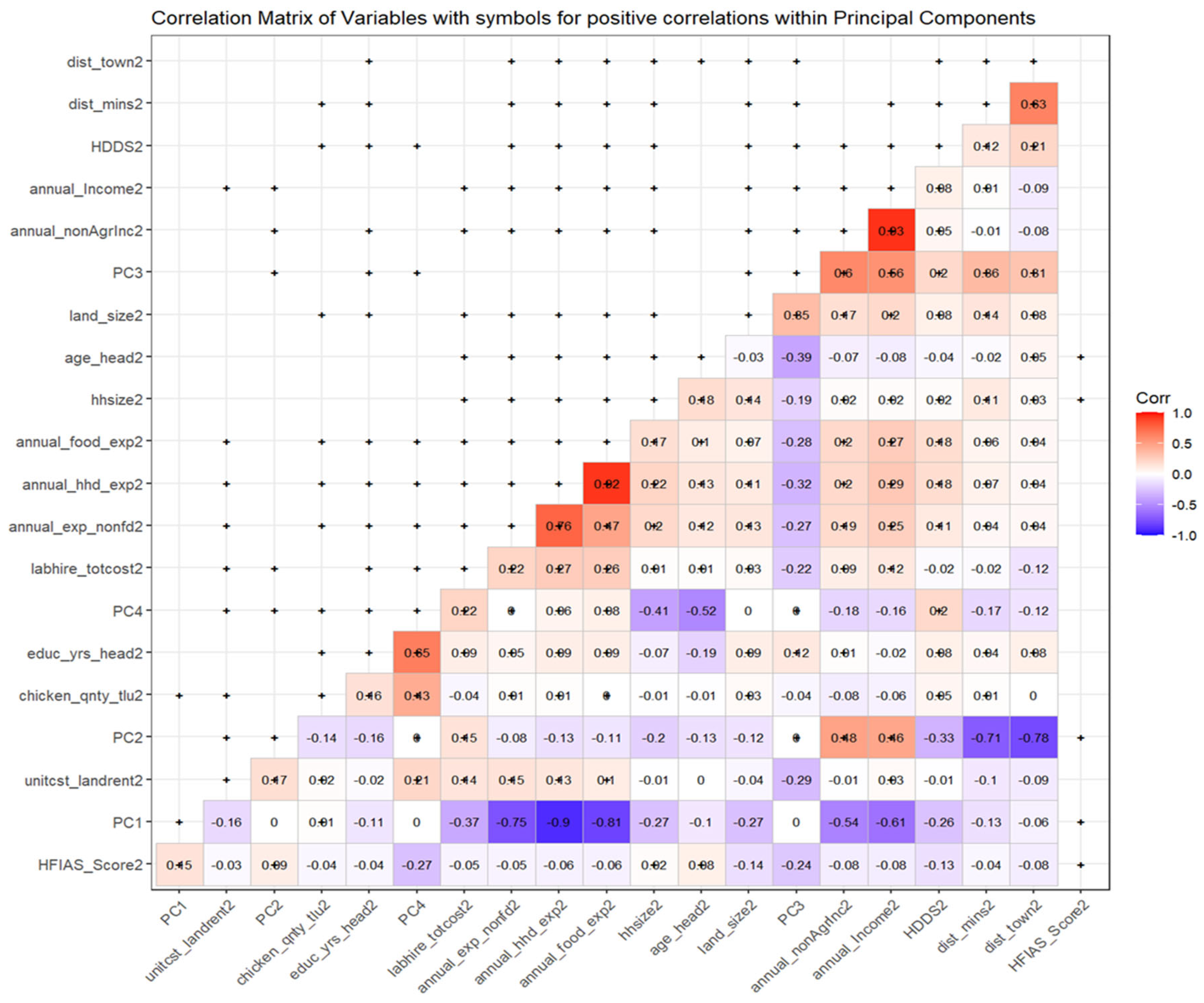

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

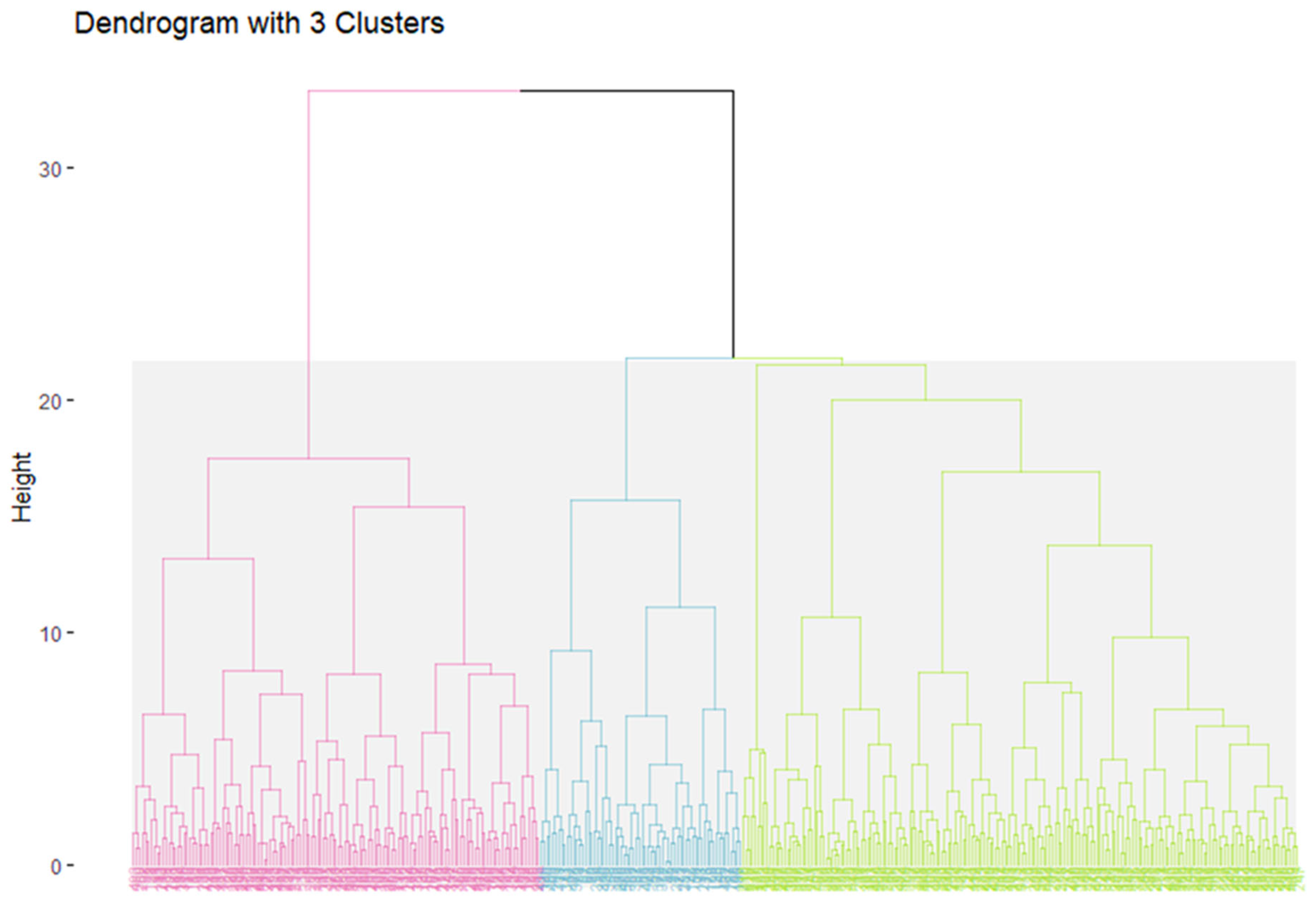

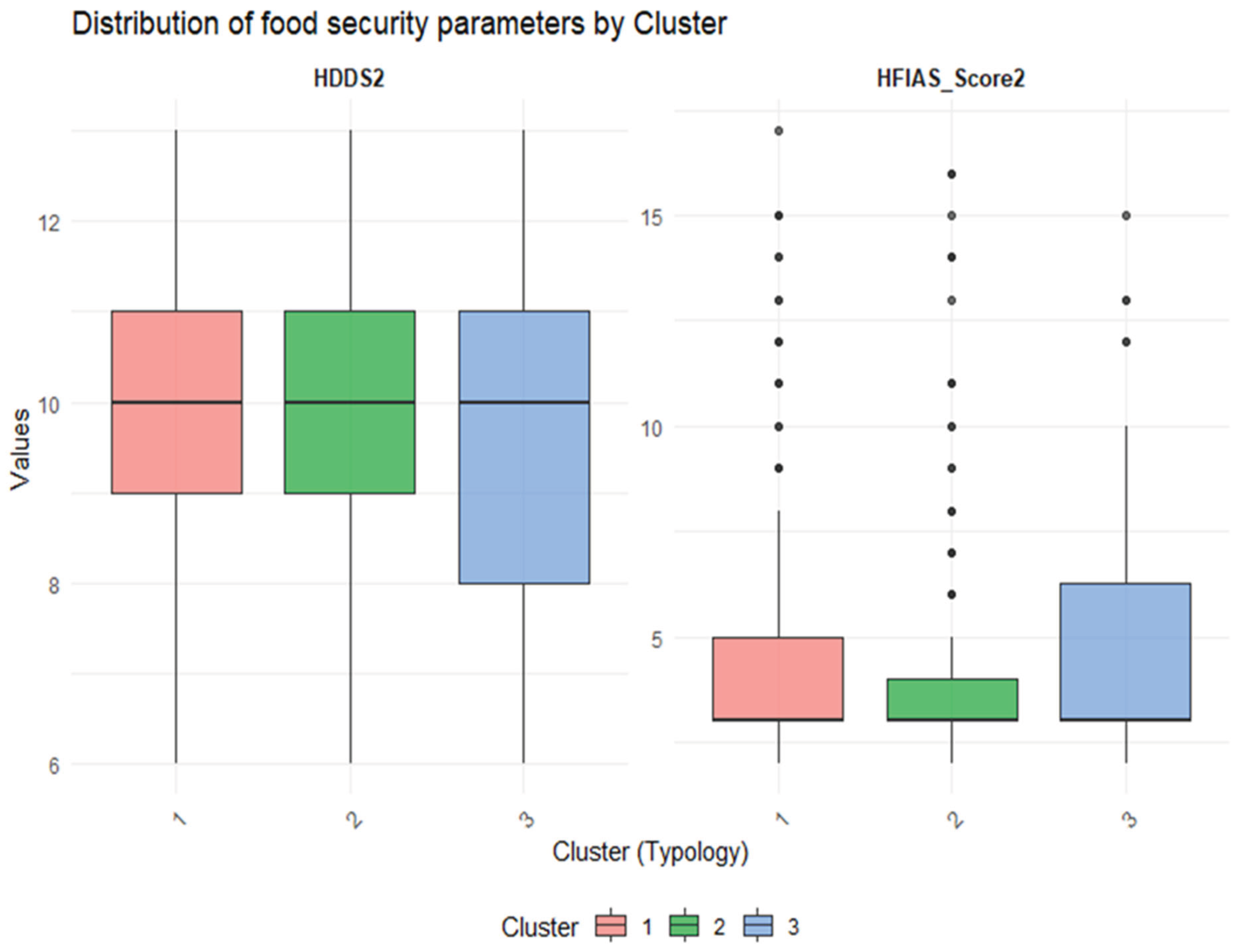

3.3. Cluster Analysis Results

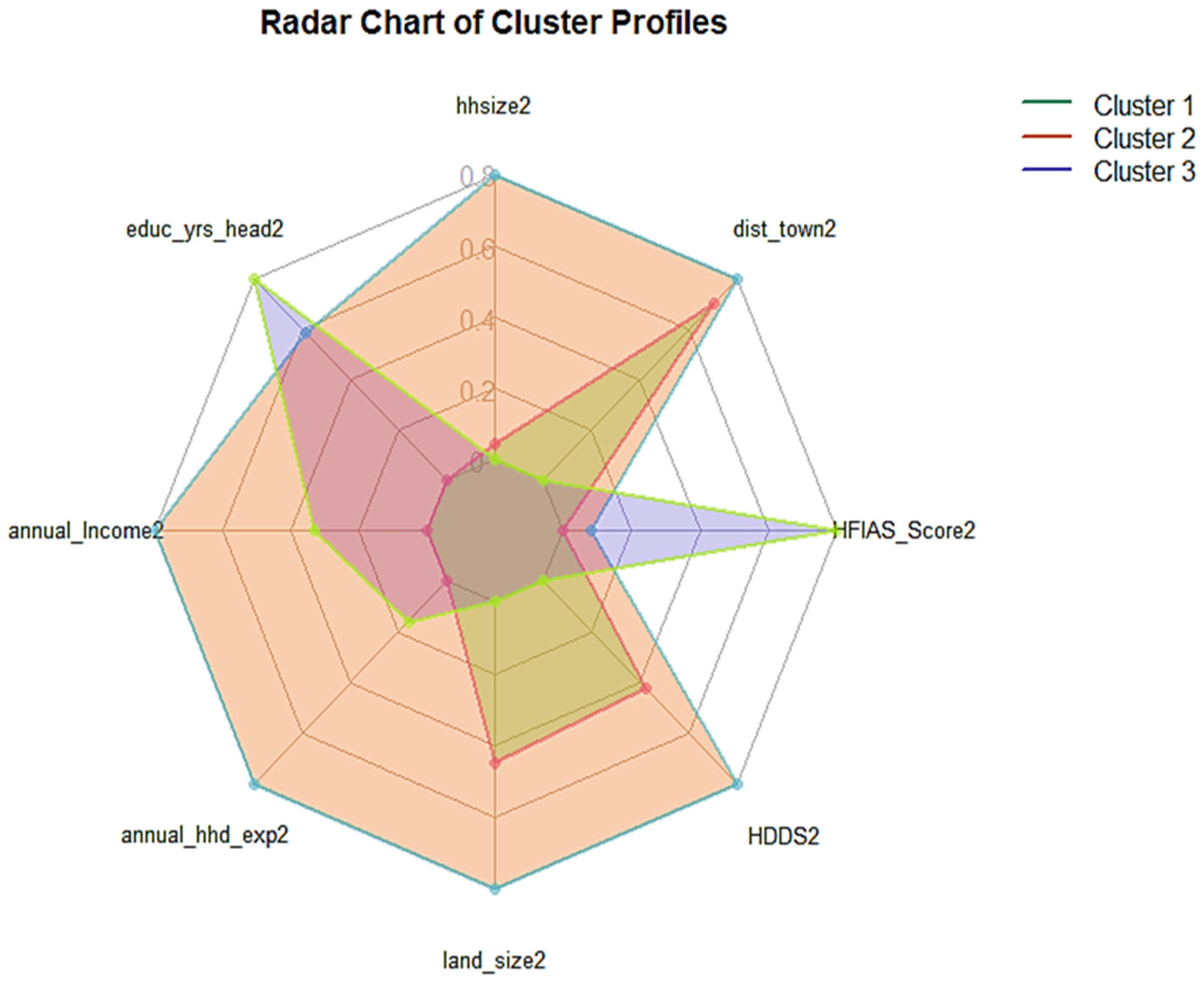

3.4. Radar Chart of Cluster Profiles

3.5. Multinomial Logistic Regression Results

4. Discussion

5. Methodological and Empirical Approach Contribution and Implications for Theory

6. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| MFA | Multiple Factorial Analysis |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| PC | Principal Component |

| TLU | Tropical Livestock Unit |

| HFIAS | Household Food Insecurity Access Scale |

| HDDS | Household Dietary Diversity Score |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| SDG | Sudanese Pound |

| LRFPP | Local and Regional Food Procurement Policy |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

Appendix A

| ANOVA Table | |||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |||

| hhsize2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 313,912 | 10 | 31,391 | 3,913 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 3056,372 | 381 | 8,022 | ||||

| Total | 3370,283 | 391 | |||||

| age_head2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 2077,169 | 10 | 207,717 | 1,424 | ,167 |

| Within Groups | 55576,665 | 381 | 145,871 | ||||

| Total | 57653,834 | 391 | |||||

| educ_yrs_head2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 681,809 | 10 | 68,181 | 3,781 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 6869,813 | 381 | 18,031 | ||||

| Total | 7551,622 | 391 | |||||

| dist_mins2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 225454,322 | 10 | 22545,432 | 19,991 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 429689,178 | 381 | 1127,793 | ||||

| Total | 655143,500 | 391 | |||||

| dist_town2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 147883,650 | 10 | 14788,365 | 30,474 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 184890,381 | 381 | 485,277 | ||||

| Total | 332774,031 | 391 | |||||

| annual_nonAgrInc2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 3883265995997,460 | 10 | 388326599599,746 | 2,804 | ,002 |

| Within Groups | 52773480245812,300 | 381 | 138513071511,318 | ||||

| Total | 56656746241809,700 | 391 | |||||

| annual_Income2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 6837784626996,730 | 10 | 683778462699,673 | 4,644 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 56101605215890,700 | 381 | 147248307653,256 | ||||

| Total | 62939389842887,400 | 391 | |||||

| annual_hhd_exp2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 23993514186560,400 | 10 | 2399351418656,040 | 14,086 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 64896765087083,700 | 381 | 170332716763,999 | ||||

| Total | 88890279273644,100 | 391 | |||||

| annual_food_exp2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 11597119619935,200 | 10 | 1159711961993,520 | 12,818 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 34472103076024,800 | 381 | 90477960829,461 | ||||

| Total | 46069222695960,000 | 391 | |||||

| annual_exp_nonfd2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 2946301528208,590 | 10 | 294630152820,859 | 8,680 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 12932743782457,600 | 381 | 33944209402,776 | ||||

| Total | 15879045310666,200 | 391 | |||||

| land_size2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 22799,259 | 10 | 2279,926 | 13,649 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 63642,052 | 381 | 167,040 | ||||

| Total | 86441,312 | 391 | |||||

| sog_landsz2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 2470,726 | 10 | 247,073 | 7,111 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 13237,822 | 381 | 34,745 | ||||

| Total | 15708,548 | 391 | |||||

| labhire_totcost2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 1639250972358,830 | 10 | 163925097235,883 | 61,552 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 1014681920888,400 | 381 | 2663207141,439 | ||||

| Total | 2653932893247,230 | 391 | |||||

| HDDS2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 156,680 | 10 | 15,668 | 5,568 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 1072,167 | 381 | 2,814 | ||||

| Total | 1228,847 | 391 | |||||

| HFIAS_Score2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 407,519 | 10 | 40,752 | 4,176 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 3717,622 | 381 | 9,758 | ||||

| Total | 4125,140 | 391 | |||||

| unitcst_landrent2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 4098043294,633 | 10 | 409804329,463 | 4,903 | ,000 |

| Within Groups | 31845750662,325 | 381 | 83584647,408 | ||||

| Total | 35943793956,958 | 391 | |||||

| chicken_qnty_tlu2 * States | Between Groups | (Combined) | 1,111 | 10 | ,111 | 2,475 | ,007 |

| Within Groups | 17,105 | 381 | ,045 | ||||

| Total | 18,216 | 391 | |||||

References

- Ehab, E.A.M.F. ARIMA, Forecasting, Sorghum and Sudan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nkosi, Z.; Marwa, N.; Akinrinde, O.O. Exploring the Feasibility of Sorghum Farming in South Africa Using Garrett’s Ranking Technique. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.; Tsegay, Z.T.; Smaoui, S.; Elfalleh, W.; Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T.; Caraher, M. One Health Approaches to Ethical, Secure, and Sustainable Food Systems and Ecosystems: Plant-Based Diets and Livestock in the African Context. Foods 2025, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Sorghum | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0459200 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Grenier, C.; Bramel, P.J.; Dahlberg, J.A.; El-Ahmadi, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Peterson, G.C.; Rosenow, D.T.; Ejeta, G. Sorghums of the Sudan: Analysis of Regional Diversity and Distribution. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2004, 51, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ahmad, I.; Hussien Ibrahim, M.; Qin, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, G. Differential Responses of Two Sorghum Genotypes to Drought Stress at Seedling Stage Revealed by Integrated Physiological and Transcriptional Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, J.A.; Burke, J.J.; Rosenow, D.T. Development of a Sorghum Core Collection: Refinement and Evaluation of a Subset from Sudan. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, E.; Kuijpers, R.; Miteng, J.A.; Deng Chol, D.; Mono, T.T.; Francesconi, N. Is Seed Aid Distribution Still Justified in South Sudan? World Dev. Perspect. 2024, 36, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Timler, C.J.; Michalscheck, M.; Paas, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Tittonell, P.; Andersson, J.A.; Groot, J.C.J. Capturing Farm Diversity with Hypothesis-Based Typologies: An Innovative Methodological Framework for Farming System Typology Development. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P.; Bruzzone, O.; Solano-Hernández, A.; López-Ridaura, S.; Easdale, M.H. Functional Farm Household Typologies through Archetypal Responses to Disturbances. Agric. Syst. 2020, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Bartkowski, B.; Brown, C.; El Benni, N.; Feil, J.-H.; Grohmann, P.; Joormann, I.; Leonhardt, H.; Mitter, H.; Müller, B. Farm Typologies for Understanding Farm Systems and Improving Agricultural Policy. Agric. Syst. 2024, 213, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Altuna, F.; Trienekens, J.; Gaitán-Cremaschi, D. Categorizing the Sustainability of Vegetable Production in Chile: A Farming Typology Approach. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2202538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beza, E.; Steinke, J.; Van Etten, J.; Reidsma, P.; Fadda, C.; Mittra, S.; Mathur, P.; Kooistra, L. What Are the Prospects for Citizen Science in Agriculture? Evidence from Three Continents on Motivation and Mobile Telephone Use of Resource-Poor Farmers. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0175700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansma, J.E.; Veen, E.J.; Müller, D. Beyond Urban Farm and Community Garden, a New Typology of Urban and Peri-urban Agriculture in Europe. Urban Agric. Reg. Food Syst. 2024, 9, e20056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivanen, K.S.; Alvarez, S.; Michalscheck, M.; Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Descheemaeker, K.; Mellon-Bedi, S.; Groot, J.C.J. Characterising the Diversity of Smallholder Farming Systems and Their Constraints and Opportunities for Innovation: A Case Study from the Northern Region, Ghana. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priegnitz, U.; Lommen, W.J.M.; Onakuse, S.; Struik, P.C. A Farm Typology for Adoption of Innovations in Potato Production in Southwestern Uganda. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagagnan, A.R.; Berre, D.; Webber, H.; Lairez, J.; Sawadogo, H.; Descheemaeker, K. From Typology to Criteria Considered by Farmers: What Explains Agroecological Practice Implementation in North-Sudanian Burkina Faso? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1386143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, E.R.A. Fortified Sorghum as a Potential for Food Security in Rural Areas by Adaptation of Technology and Innovation in Sudan. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]

- BabekirElgali, M.; Mustafa, R.H.; Kirschke, D.; Khair, A.Y.M.; Maruod, M.E. SORGHUM PERFORMANCE UNDER CLIMATE CHANGE IN SUDAN. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mwadalu, R.; Mwangi, M. The Potential Role of Sorghum in Enhancing Food Security in Semi-Arid Eastern Kenya: A Review. J. Appl. Biosci. 2013, 71, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Elrasheed, M. Socioeconomic Factors Affecting Sorghum Productivity in the Rain-Fed Sector of Gadarif State, Sudan. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Paas, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Tittonell, P.; Groot, J. Constructing Typologies, a Way to Deal with Farm Diversity: General Guidelines for the Humidtropics. Report for the CGIAR Research Program on Integrated Systems for the Humid Tropics. Plant Sci. Group 2014, Report for, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Adzawla, W.; Atakora, W.K.; Kissiedu, I.N.; Martey, E.; Etwire, P.M.; Gouzaye, A.; Bindraban, P.S. Characterization of Farmers and the Effect of Fertilization on Maize Yields in the Guinea Savannah, Sudan Savannah, and Transitional Agroecological Zones of Ghana. EFB Bioeconomy J. 2021, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidogeza, J.C.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; Graaff, J.; Oude Lansink, a. G.J.M. Multivariate Typology of Farm Households Based on Socio-Economic Characteristics Explaining Adoption of New Technology in Rwanda. AAAE Ghana Conf. 2007, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Nabahungu, N.L.; Mirali, J.C.; Simbeko, G.; Amato, S.; Mirali, G.M.; Muhindo, P.M.; Kitangala, C.; Balangaliza, F.B.; Nguezet, P.-M.D.; Kintche, K.; et al. Farmer Typology and Adoption of Improved Cassava Production Technologies in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2025, 0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P.; Muriuki, A.; Shepherd, K.D.; Mugendi, D.; Kaizzi, K.C.; Okeyo, J.; Verchot, L.; Coe, R.; Vanlauwe, B. The Diversity of Rural Livelihoods and Their Influence on Soil Fertility in Agricultural Systems of East Africa – A Typology of Smallholder Farms. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Paas, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Tittonell, P.; Groot, J.C.J. Constructing Typologies, a Way to Deal with Farm Diversity: General Guidelines for the Humidtropics. Rep. CGIAR Res. Program Integr. Syst. Humid Trop. Plant Sci. Group Wagening. Univ. Neth. 2014, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tittonell, P.A. Farming Systems Ecology: Towards Ecological Intensification of World Agriculture; Wageningen Universiteit: Wageningen, 2013; ISBN 978-94-6173-617-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shifat, S. Sorghum Farming in Sudan: A Deep Dive into Its Impact on the Economy - The African Dreams ! 2025. [Google Scholar]

- M Elamin, E. Economic Consideration and Model Development Spatial Trade for Sorghum and Millet Staple Food in Sudan. Agric. Res. Technol. Open Access J. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP Celebrates Sorghum Harvest in Eastern Sudan under World Bank Managed THABAT Project | World Food Programme. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-celebrates-sorghum-harvest-eastern-sudan-under-world-bank-managed-thabat-project (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Abarca, R.M. Practical Guide to Principal Component Mathods in R:PCA, (M)CA, FAMD, MFA, HCPC, Factorextra. Nuevos Sist. Comun. E Inf. 2021, 2013–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simbeko, G.; Nguezet, P.-M.D.; Sekabira, H.; Yami, M.; Masirika, S.A.; Bheenick, K.; Bugandwa, D.; Nyamuhirwa, D.-M.A.; Mignouna, J.; Bamba, Z.; et al. Entrepreneurial Potential and Agribusiness Desirability among Youths in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sustainability 2023, 15, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Kumaranayake, L. Constructing Socio-Economic Status Indices: How to Use Principal Components Analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006, 21, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S. Application of Multinomial Logistic to Smallholder Farmers’ Market Participation in Northern Ghana. Int. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekabira, H.; Feleke, S.; Manyong, V.; Späth, L.; Krütli, P.; Simbeko, G.; Vanlauwe, B.; Six, J. Circular Bioeconomy Practices and Their Associations with Household Food Security in Four RUNRES African City Regions. PLOS Sustain. Transform. 2024, 3, e0000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, L.T. A Multinomial Logit Model Analysis of Farmers’ Participation in. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coscieme, L.; Da Silva Hyldmo, H.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Palomo, I.; Mwampamba, T.H.; Selomane, O.; Sitas, N.; Jaureguiberry, P.; Takahashi, Y.; Lim, M.; et al. Multiple Conceptualizations of Nature Are Key to Inclusivity and Legitimacy in Global Environmental Governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manners, R.; Hammond, J.; Umugabe, D.R.; Sibomana, M.; Schut, M. A Farm Typology Development Cycle: From Empirical Development through Validation, to Large-Scale Organisational Deployment. Agric. Syst. 2025, 224, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikowo, R.; Zingore, S.; Snapp, S.; Johnston, A. Farm Typologies, Soil Fertility Variability and Nutrient Management in Smallholder Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2014, 100, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudioTeam RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Cappellari, L.; Jenkins, S.P. Multivariate Probit Regression Using Simulated Maximum Likelihood. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2003, 3, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, L.O.; Baiyegunhi, L.J.S.; Mignouna, D.; Adeoti, R.; Dontsop-Nguezet, P.M.; Abdoulaye, T.; Manyong, V.; Bamba, Z.; Awotide, B.A. Impact of Youth-in-Agribusiness Program on Employment Creation in Nigeria. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamuzora, A.N. Exploring Youth Perceptions in Choosing Employment in the Agricultural Production Sector in Morogoro Municipality, Tanzania. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Prusty, A.K.; Ravisankar, N.; Panwar, A.S.; Shamim, M.; Walia, S.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Pasha, M.L.; Babu, S.; Jat, M.L.; et al. Farm Typology for Planning Targeted Farming Systems Interventions for Smallholders in Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, D.; Mburu, J.; Mignouna, D. Youth Agricultural Entrepreneurship : Assessing the Impact of Agricultural Training Programmes on Performance. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bidogeza, J.C.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; De Graaff, J.; Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M. A Typology of Farm Households for the Umutara Province in Rwanda. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.M.; Mozzon, M.; Omer, A.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovács, B. Major and Trace Elements of Baobab Leaves in Different Habitats and Regions in Sudan: Implication for Human Dietary Needs and Overall Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mahish, M.A.; Elzaki, R.; Sisman, M.Y. Food Security in Rural Sudan. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.H.; Sokout, S.; Nakajima, H.; Kumamoto, M.; Khan, G.D. Addressing Food Insecurity in South Sudan: Insights and Solutions from Young Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokros, N.; Woomer, J.; Schroeder, Z.; Kunduru, B.; Brar, M.S.; Seegmiller, W.; Stork, J.; McMahan, C.; Robertson, D.J.; Sekhon, R.S.; et al. Sorghum Bicolor L. Stalk Stiffness Is Marginally Affected by Time of Day under Field Conditions. Agriculture 2024, 14, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.M.; Gorafi, Y.S.A.; Abdeltwab, H.; Abdalla, I.; Tsujimoto, H.; Ghanim, A.M.A. A New Breeding Strategy towards Introgression and Characterization of Stay-Green QTL for Drought Tolerance in Sorghum. Agriculture 2021, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.C.; van de Ven, G.W.J.; van Ittersum, M.K.; Giller, K.E. The Production-Ecological Sustainability of Cassava, Sugarcane and Sweet Sorghum Cultivation for Bioethanol in Mozambique. GCB Bioenergy 2012, 4, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makate, C.; Makate, M.; Mango, N. Farm Types and Adoption of Proven Innovative Practices in Smallholder Bean Farming in Angonia District of Mozambique. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2018, 45, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP Evaluation of Local and Regional Food Procurement Pilot Programmes in Eastern Africa (2021-2023). 2024.

| Category | Code | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | hhsize2 | Household size | Number of people |

| age_head2 | Age of household head | Years | |

| educ_yrs_head2 | Years of education of the household head | Education years | |

| Accessibility | dist_mins2 | Distance to the nearby local market | Minutes |

| dist_town2 | Distance to the market in the city | Minutes | |

| Incomes | annual_nonAgrInc2 | Annual income from off-farm activities | SDG Currency |

| annual_Income2 | Total annual household income | SDG Currency | |

| Expenses | annual_hhd_exp2 | Total annual household expenses | SDG Currency |

| annual_food_exp2 | Annual food expenses | SDG Currency | |

| annual_exp_nonfd2 | Annual expenses excluding food | SDG Currency | |

| Agricultural Asset | land_size2 | Total area of household’s land cultivated | Acres |

| sog_landsz2 | Area of land cultivated to grow Sorghum | Acres | |

| Labor | labhire_totcost2 | Total cost of labor hired | SDG Currency |

| Food Security | HDDS2 | Household dietary diversity score | Nbr of food groups |

| HFIAS_Score2 | Household food insecurity score | Proxy (0–27) | |

| Market / production | unitcst_landrent2 | Unit cost of land rental | SDG Currency |

| Livestock | chicken_qnty_tlu2 | Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) | TLU |

| Variables/States | South Darfur (N=37) | South Kordofan (N=34) |

West Darfur (N=39) |

West Kordofan (N=40) |

White Nile (N=34) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hhsize2 | 9.05 (2.54) |

9.59 (3.09) |

8.13 (2.15) |

7.93 (2.66) |

8.38 (2.35) |

0.000 |

| age_head2 | 48.84 (9.42) |

47.03 (11.58) |

50.36 (12.33) |

48.35 (13.81) |

49.32 (12.28) |

0.167 |

| educ_yrs_head2 | 8.68 (4.99) |

7.85 (4.40) |

7.85 (4.30) |

6.10 (3.15) |

5.44 (3.00) |

0.000 |

| dist_mins2 | 57.62 (27.61) |

28.94 (30.04) |

78.51 (53.45) |

42.25 (17.82) |

24.97 (15.16) |

0.000 |

| dist_town2 | 63.03 (30.78) |

8.29 (8.74) |

44.74 (32.24) |

34.80 (5.16) |

23.53 (13.53) |

0.000 |

| annual_nonAgrInc2 | 311,735.28 (344,703.16) |

414,929.61 (392,254.88) |

227,991.99 (179,838.39) |

223,439.82 (17,3957.19) |

418,904.47 (568,517.15) |

0.002 |

| annual_Income2 | 349,325.19 (339,680.89) |

466,350.27 (429,812.28) |

244,340.95 (184,528.97) |

251,816.80 (186,683.34) |

580,622.36 (502,320.97) |

0.000 |

| annual_hhd_exp2 | 674,155.59 (228,065.46) |

709,976.02 (417,996.48) |

565,305.21 (270,404.54) |

591,811.00 (203,580.64) |

813,986.88 (483,750.41) |

0.000 |

| annual_food_exp2 | 409,236.68 (137,088.13) |

531,798.11 (352,396.43) |

429,551.77 (178,082.02) |

432,916.00 (146,129.13) |

599,541.64 (265,524.76) | 0.000 |

| annual_exp_nonfd2 | 264,919.92 (173,228.97) |

178,178.91 (125,921.47) |

135,754.44 (122,013.29) |

158,896.00 (124,706.14) |

256,185.32 (247,603.71) |

0.000 |

| land_size2 | 20.58 (17.03) |

24.98 (17.25) |

4.23 (2.29) |

12.27 (7.20) |

13.98 (11.27) |

0.000 |

| sog_landsz2 | 4.76 (3.63) |

9.62 (8.82) |

2.41 (0.72) |

7.20 (5.81) |

8.12 (6.33) |

0.000 |

| labhire_totcost2 | 31,618.64 (7,164.63) |

16,895.34 (4,1875.61) |

6,277.56 (8,133.09) |

25,320.70 (17,726.72) |

4,467.65 (8,347.26) |

0.000 |

| HDDS2 | 9.86 (1.32) |

8.71 (1.27) |

9.69 (1.66) |

9.00 (1.84) |

9.26 (2.03) |

0.000 |

| HFIAS_Score2 | 3.38 (1.91) |

3.03 (0.52) |

4.77 (3.32) |

6.03 (4.04) |

5.26 (3.80) |

0.000 |

| unitcst_landrent2 | 5,365.22 (4,804.92) |

6,969.10 (9,170.56) |

4,660.91 (1,646.46) |

3,206.49( 1,466.83) |

14,916.27 (15,828.65) |

0.000 |

| chicken_qnty_tlu2 | 2.04 (0.19) |

2.07 (0.00) |

1.99 (0.20) |

1.97 (0.20) |

1.98 (0.24) | 0.007 |

| Test | Chi-Square | Df | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Sphericity Test | 1,911.201 | 66 | 0.000 |

| KMO | MSA = 0.78 |

| Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | Cumulative Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.717 | 22.643 | 22.643 |

| 1.836 | 15.302 | 37.946 |

| 1.532 | 12.768 | 50.713 |

| 1.291 | 10.754 | 61.468 |

| 1.252 | 10.435 | 71.902 |

| 0.913 | 7.604 | 79.507 |

| 0.728 | 6.070 | 85.577 |

| 0.605 | 5.040 | 90.617 |

| 0.464 | 3.868 | 94.485 |

| 0.442 | 3.686 | 98.171 |

| 0.181 | 1.509 | 99.680 |

| 0.038 | 0.320 | 100.000 |

| Variable | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 3 | PC 4 | PC 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hhsize2 | 0.334 | 0.155 | -0.067 | 0.062 | 0.448 |

| age_head2 | 0.136 | 0.283 | -0.248 | 0.044 | 0.668 |

| educ_yrs_head2 | 0.135 | -0.023 | 0.028 | -0.017 | -0.710 |

| dist_mins2 | 0.214 | 0.236 | 0.587 | -0.561 | 0.105 |

| dist_town2 | 0.160 | 0.471 | 0.501 | -0.493 | -0.017 |

| annual_nonAgrInc2 | 0.355 | -0.808 | 0.286 | -0.027 | 0.155 |

| annual_Income2 | 0.420 | -0.777 | 0.304 | -0.003 | 0.155 |

| annual_hhd_exp2 | 0.909 | 0.148 | -0.289 | -0.058 | -0.112 |

| annual_food_exp2 | 0.827 | 0.106 | -0.254 | -0.091 | -0.088 |

| annual_exp_nonfd2 | 0.734 | 0.079 | -0.226 | 0.059 | -0.141 |

| land_size2 | 0.360 | 0.214 | 0.559 | 0.514 | -0.013 |

| sorghum_landsz2 | 0.127 | 0.333 | 0.429 | 0.669 | -0.019 |

| Variance Explained (%) | 22.643 | 15.302 | 12.768 | 10.754 | 10.435 |

| Overall Mean (SD) | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | p.overall | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=392 | N=187 | N=137 | N=68 | |||

| Household size | 8.89 (2.94) | 8.25 (2.64) | 10.1 (3.05) | 8.13 (2.69) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Age of household head | 48.9 (12.1) | 47.8 (12.7) | 52.2 (11.0) | 45.2 (11.5) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Head of household's years of Education | 7.37 (4.39) | 6.67 (4.34) | 7.87 (4.43) | 8.29 (4.22) | 0.009 | 392 |

| Distance to the nearby local market | 49.7 (40.9) | 53.3 (41.2) | 62.9 (40.0) | 13.1 (8.49) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Distance to the market in the city | 36.2 (29.2) | 39.6 (27.7) | 43.4 (29.0) | 12.3 (20.4) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Annual income from non-agricultural activities | 346,119 (380,660) | 309,942 (342,319) | 378,062 (433,410) | 381,250 (363,350) | 0.189 | 392 |

| Total annual household income | 421,817 (401,211) | 370,598 (344,427) | 492,036 (473,508) | 421,199 (370,874) | 0.040 | 392 |

| Total annual household expenses | 802,685 (476,803) | 532,000 (196,986) | 1,236,464 (474,634) | 673,132 (394,246) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Annual food expenses | 561,652 (343,255) | 395,179 (159,051) | 832,792 (380,318) | 473,187 (296,908) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Annual expenses excluding food | 246,157 (201,523) | 144,602 (103,117) | 405,692 (220,428) | 204,015 (161,938) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Total area of household land cultivated | 15.8 (14.9) | 15.0 (14.8) | 21.0 (16.0) | 7.27 (5.93) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Area of Sorghum’s land cultivated | 6.33 (6.34) | 6.31 (5.79) | 8.00 (7.73) | 3.01 (1.84) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Total cost of labor engaged | 34,203 (82,387) | 15,533 (34,207) | 61,717 (116,301) | 30,115 (79,809) | <0.001 | 392 |

| Household dietary diversity score (HDDS) | 9.71 (1.77) | 9.68 (1.77) | 9.88 (1.77) | 9.46 (1.79) | 0.272 | 392 |

| Household food insecurity score (HFIAS) | 4.68 (3.25) | 4.58 (3.23) | 4.63 (3.34) | 5.07 (3.14) | 0.527 | 392 |

| Unit cost of land rental (acres) | 6,994 (9,588) | 5,783 (7,930) | 7,492 (10083) | 9,322 (12,061) | 0.042 | 392 |

| Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) | 2.02 (0.22) | 2.01 (0.20) | 2.03 (0.25) | 2.01 (0.18) | 0.845 | 392 |

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| hhsize2 | -0.00599 | 0.0244*** | -0.0184*** |

| (0.00611) | (0.00515) | (0.00468) | |

| age_head2 | -0.00128 | 0.00307** | -0.00180** |

| (0.00134) | (0.00126) | (0.000834) | |

| educ_yrs_head2 | -0.00807** | 0.00633** | 0.00175 |

| (0.00371) | (0.00322) | (0.00266) | |

| dist_mins2 | 0.00395*** | 0.00302*** | -0.00697*** |

| (0.00102) | (0.000601) | (0.00119) | |

| annual_food_exp2 | -0.000000465* | 0.000000123 | 0.000000342 |

| (0.000000282) | (0.000000239) | (0.000000213) | |

| land_size2 | 0.00111 | 0.00403*** | -0.00515*** |

| (0.00157) | (0.00123) | (0.00184) | |

| sog_landsz2 | 0.0114*** | 0.00963*** | -0.0210*** |

| (0.00419) | (0.00286) | (0.00520) | |

| dist_town2 | 0.000817 | 0.00131* | -0.00213*** |

| (0.000873) | (0.000747) | (0.000765) | |

| annual_hhd_exp2 | -8.75e-08 | 0.000000323 | -0.000000235 |

| (0.000000256) | (0.000000229) | (0.000000196) | |

| annual_Income2 | -1.23e-09 | 2.82e-08 | -2.70e-08 |

| (0.000000137) | (0.000000112) | (0.000000124) | |

| annual_exp_nonfd2 | -0.000000629** | 0.000000351 | 0.000000278 |

| (0.000000275) | (0.000000253) | (0.000000201) | |

| labhire_totcost2 | -0.000000876 | 0.000000257 | 0.000000619* |

| (0.000000562) | (0.000000437) | (0.000000350) | |

| annual_nonAgrInc2 | 8.54e-09 | -9.65e-08 | 8.79e-08 |

| (0.000000135) | (0.000000112) | (0.000000118) | |

| chicken_qnty_tlu2 | -0.0500 | 0.0445 | 0.00557 |

| (0.0915) | (0.0768) | (0.0651) | |

| unitcst_landrent2 | 0.00000154 | -0.00000232 | 0.000000777 |

| (0.00000195) | (0.00000189) | (0.000000919) | |

| HFIAS_Score2 | -0.00765 | 0.00607 | 0.00158 |

| (0.00504) | (0.00408) | (0.00435) | |

| HDDS2 | 0.00549 | -0.00659 | 0.00110 |

| (0.00895) | (0.00850) | (0.00699) | |

| Blue Nile | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| Central Darfur | -0.0129 | 0.0383 | -0.0254 |

| (0.0951) | (0.0885) | (0.0726) | |

| East Darfur | 0.240 | 0.0752 | -0.315 |

| (20.25) | (5.969) | (26.22) | |

| Gedarif | 0.0969 | 0.140 | -0.237** |

| (0.154) | (0.121) | (0.106) | |

| Kassala | 0.140 | 0.0407 | -0.180** |

| (0.0872) | (0.0727) | (0.0848) | |

| North Kordofan | 0.161** | 0.130* | -0.291*** |

| (0.0815) | (0.0733) | (0.0702) | |

| South Darfur | 0.228*** | 0.109* | -0.337*** |

| (0.0655) | (0.0600) | (0.0609) | |

| South Kordofan | 0.0927 | 0.0165 | -0.109 |

| (0.0727) | (0.0640) | (0.0720) | |

| West Darfur | 0.165** | -0.0243 | -0.141* |

| (0.0769) | (0.0665) | (0.0767) | |

| West Kordofan | 0.131* | 0.206*** | -0.337*** |

| (0.0670) | (0.0609) | (0.0609) | |

| White Nile | 0.0524 | 0.151** | -0.203*** |

| (0.0823) | (0.0698) | (0.0748) | |

| N | 392 | 392 | 392 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).