Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

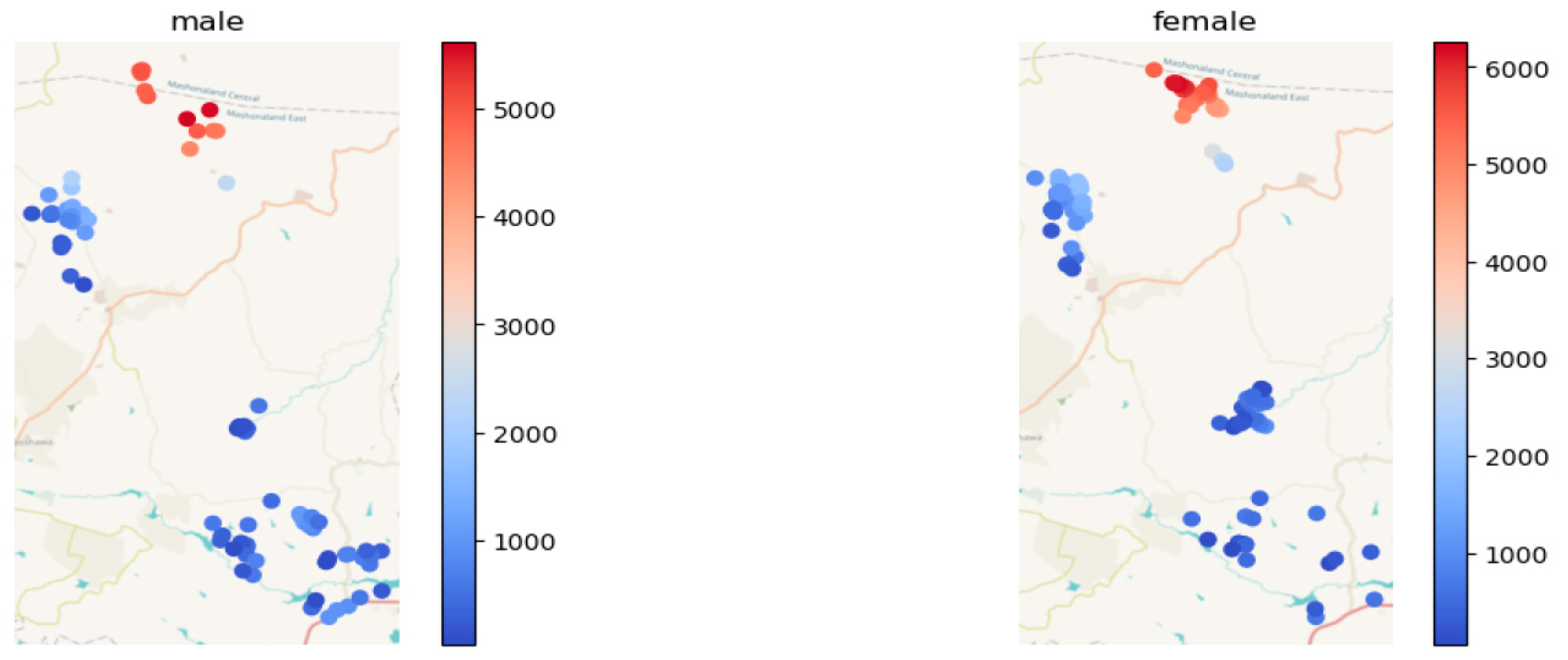

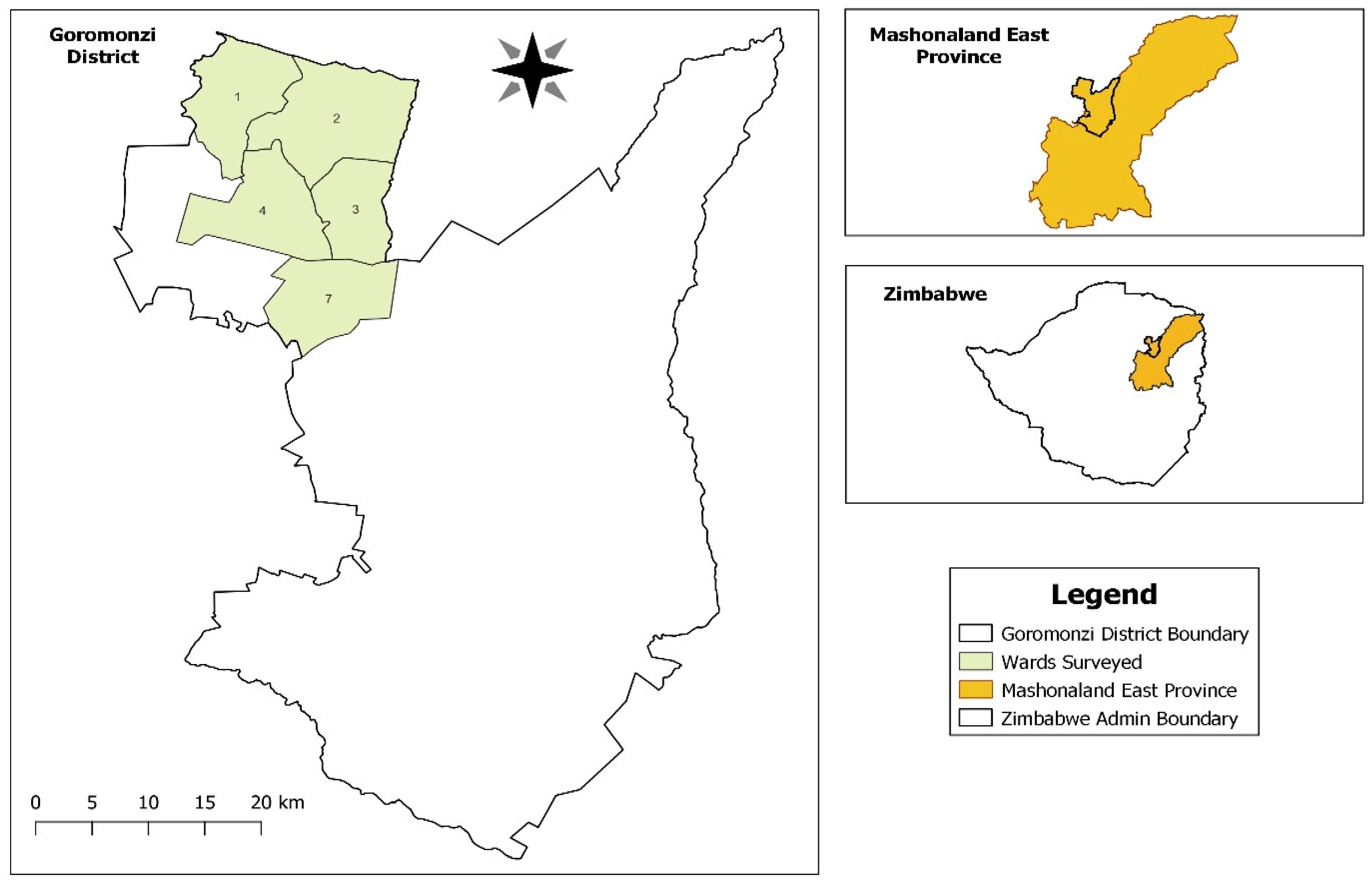

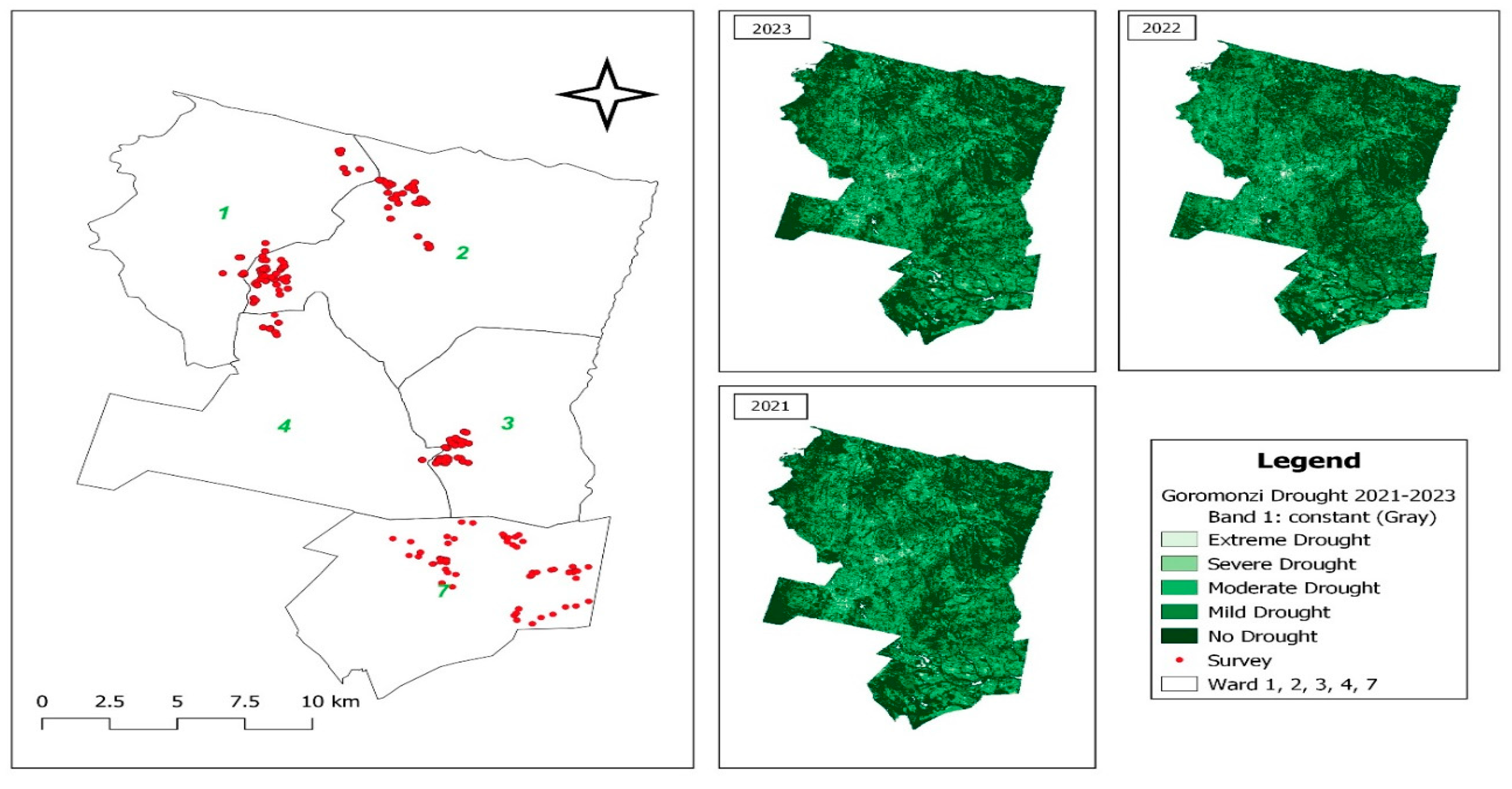

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

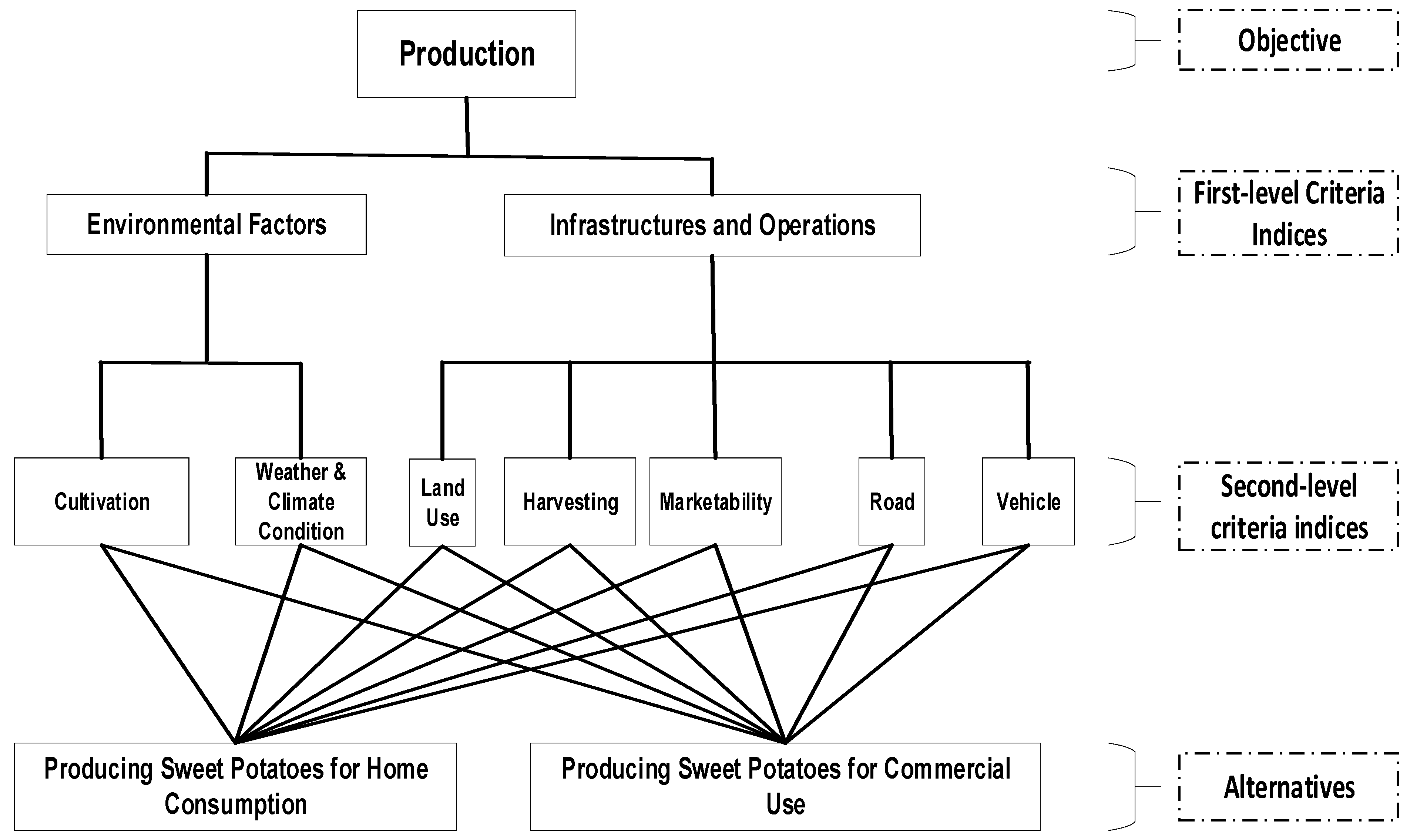

- Firstly, it delineated a series of criteria indices relevant to sweet potato production, setting these against alternatives within the context of available resources.

- Subsequently, through a detailed comparison of location-specific criteria using AHP, the study assigned weights (scores) to these criteria.

- Lastly, a comparative analysis was conducted between the sweet potato production criteria indices and their respective scores, utilizing a fuzzy MCDM approach.

2.3. Data Analysis

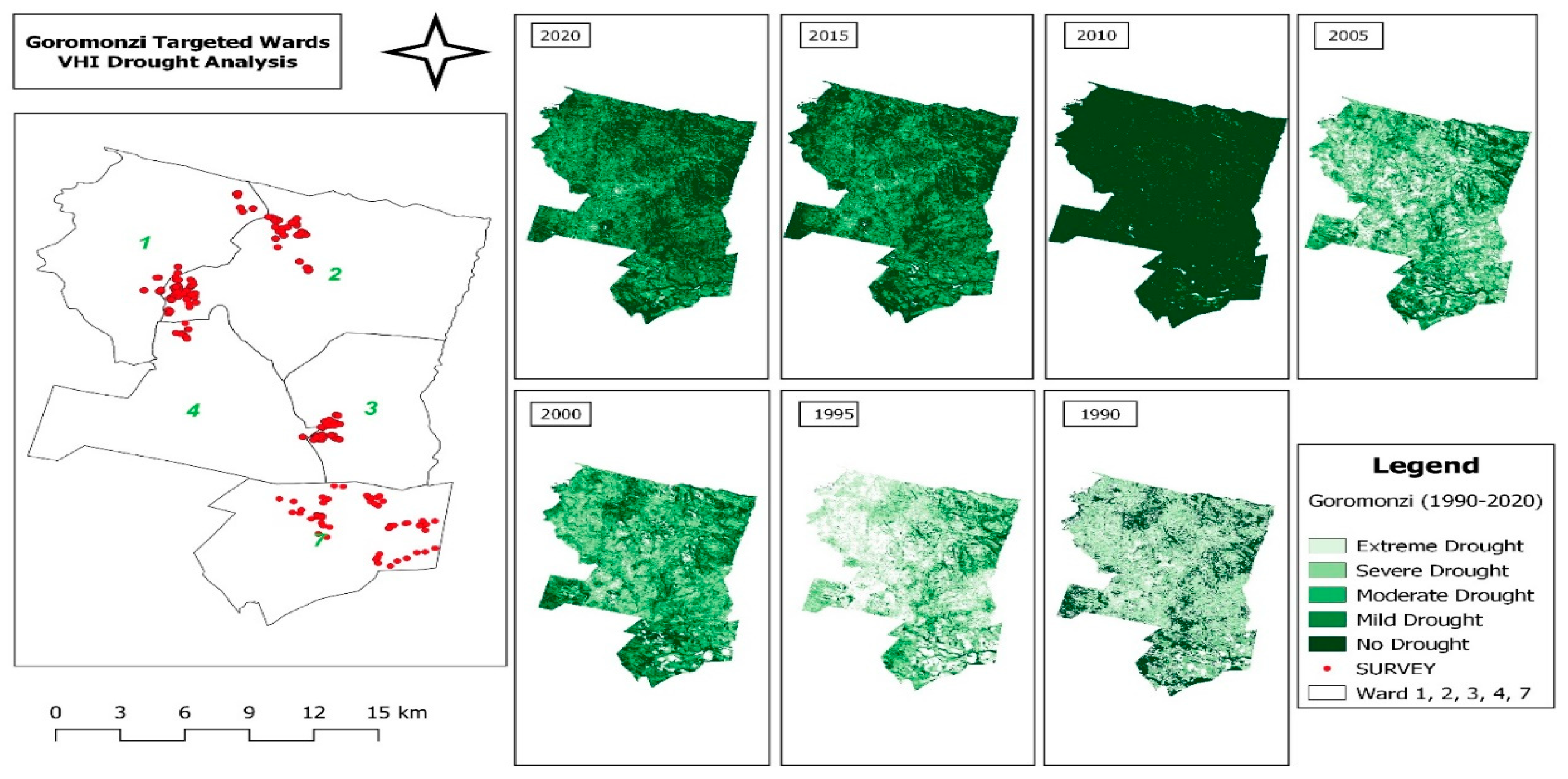

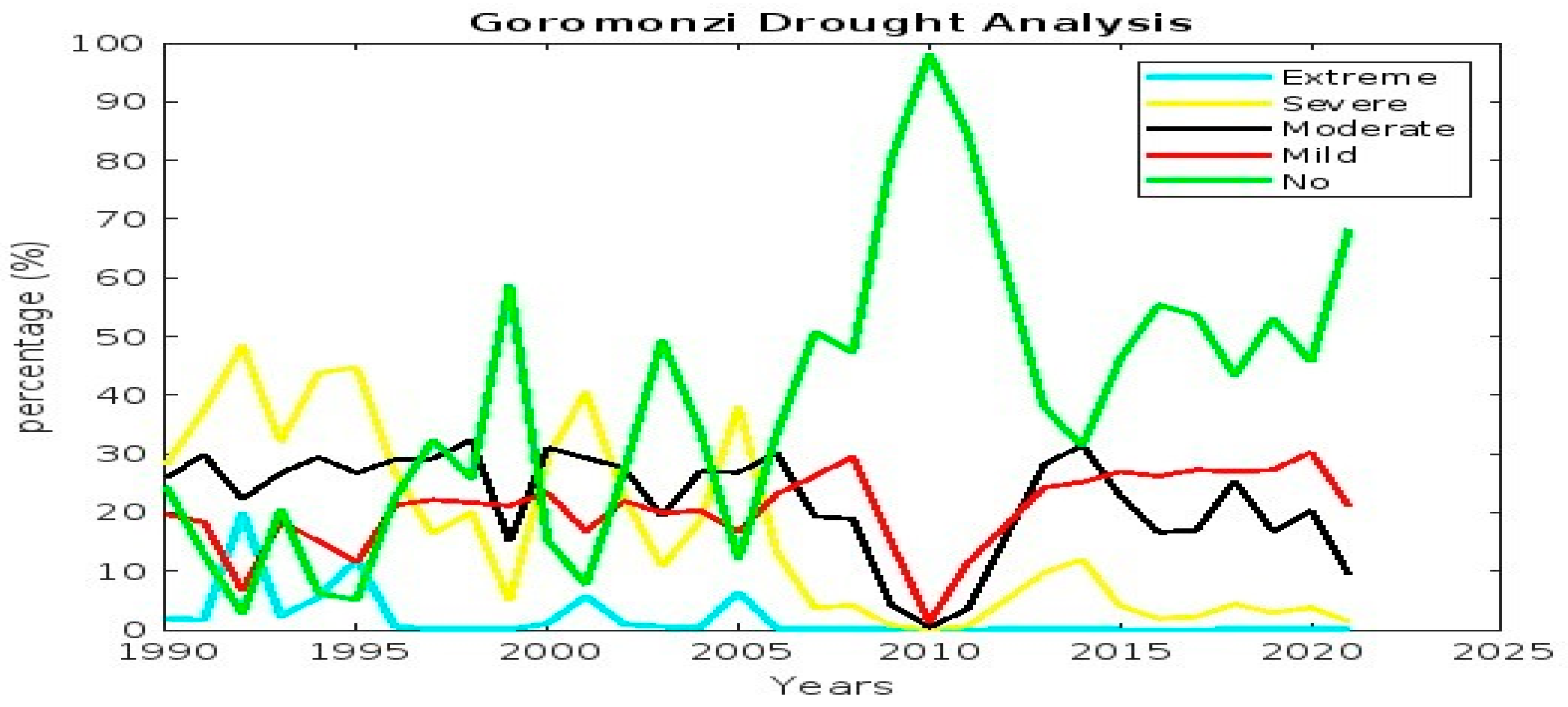

2.3.2. VHI

2.3.3. Multi Criteria Decision-Making Model

- 1.

- Selection of criteria indices

- 2.

- Weighting the criteria indices

- 2.a.

- Utilization of Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs)

- 2.b.

- Formulating f-AHP Comparison Matrices

- 2.c.

- Evaluating Fuzzy Synthetic Extent

- 3.

- Calculating f-AHP Weighted Values

3. Results

3.1. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model

3.1.1. Definition of Drought Impacts on Sweet Potato Production in Zimbabwe

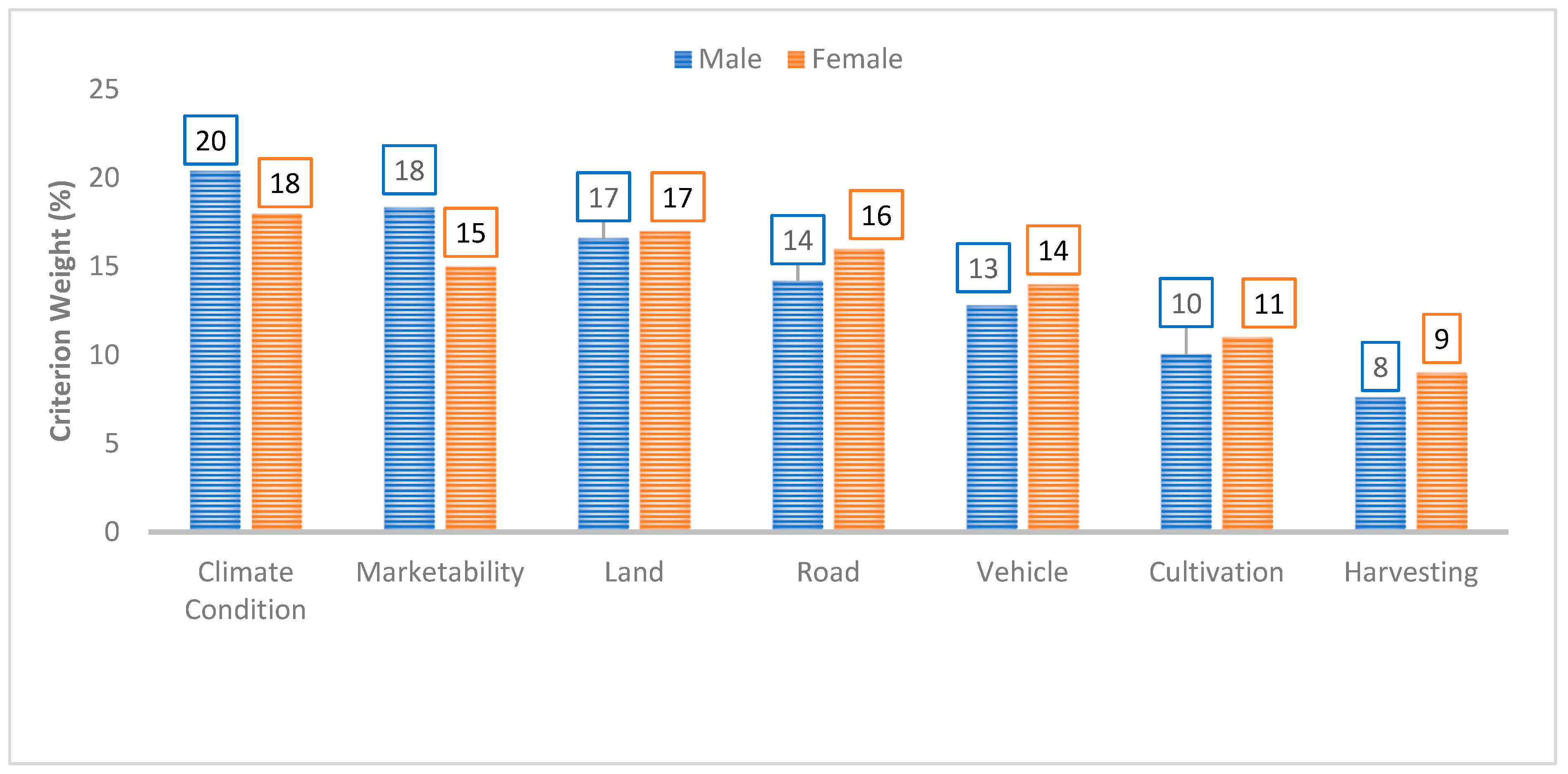

3.1.2. Weightage of Sweet Potato Production Criteria

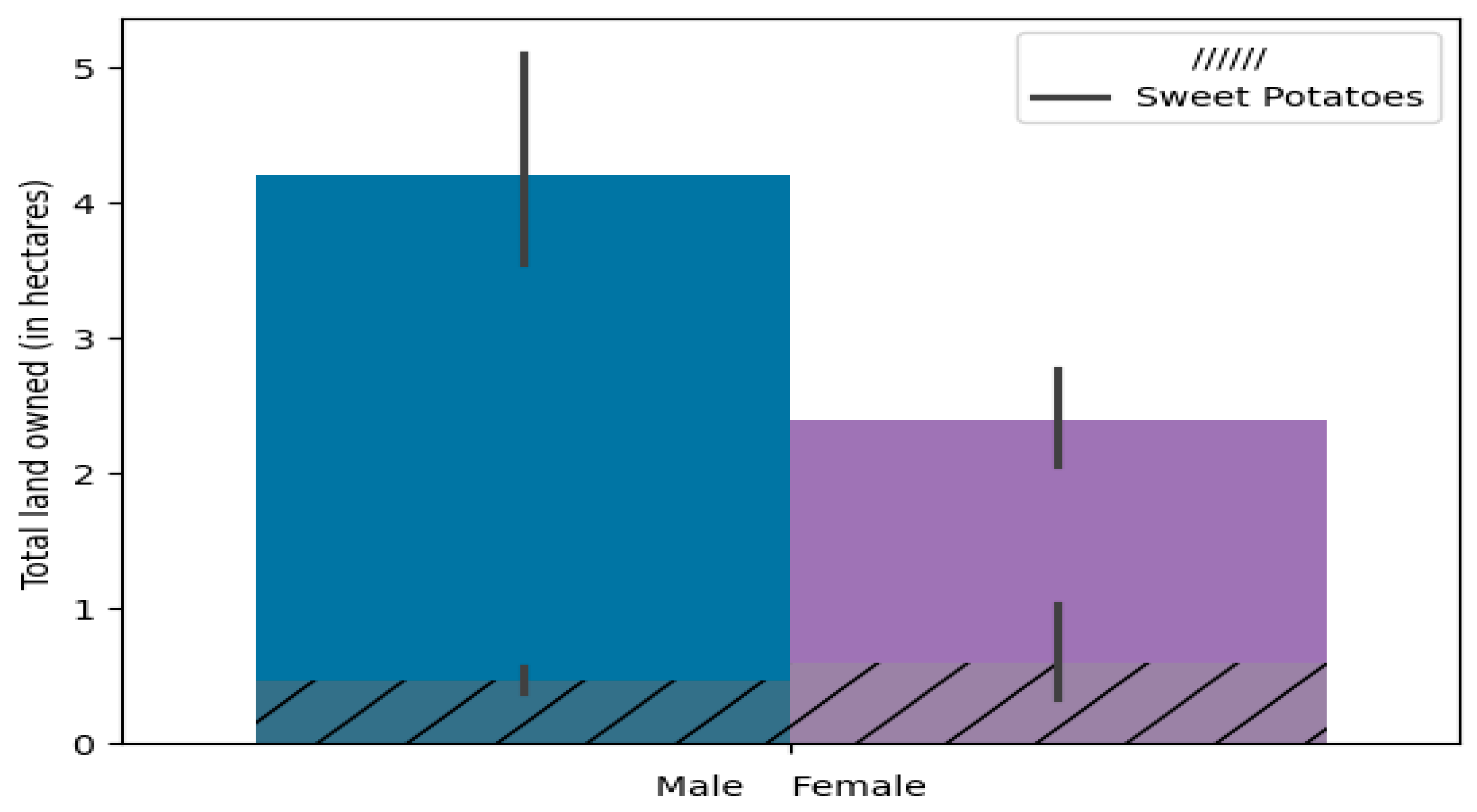

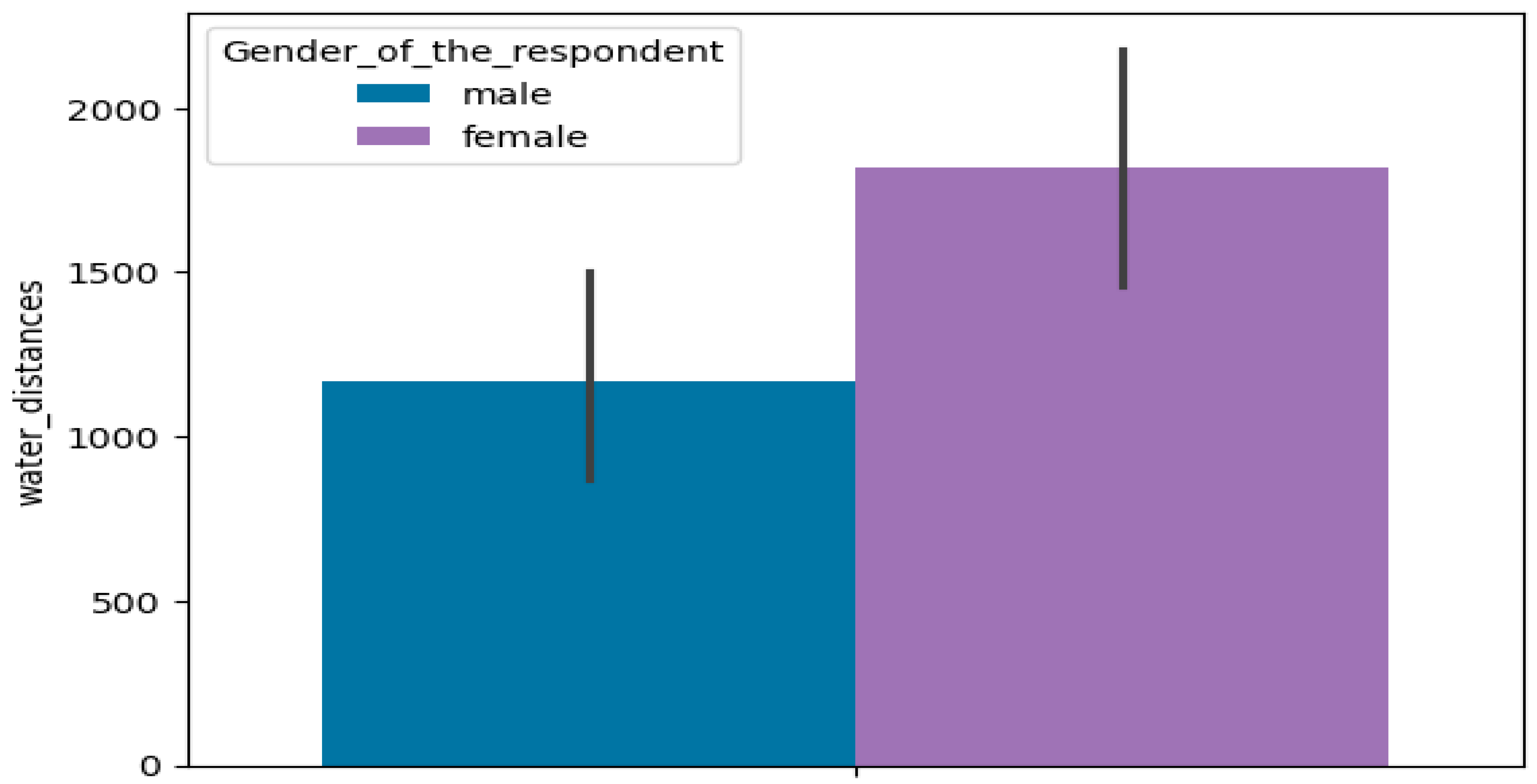

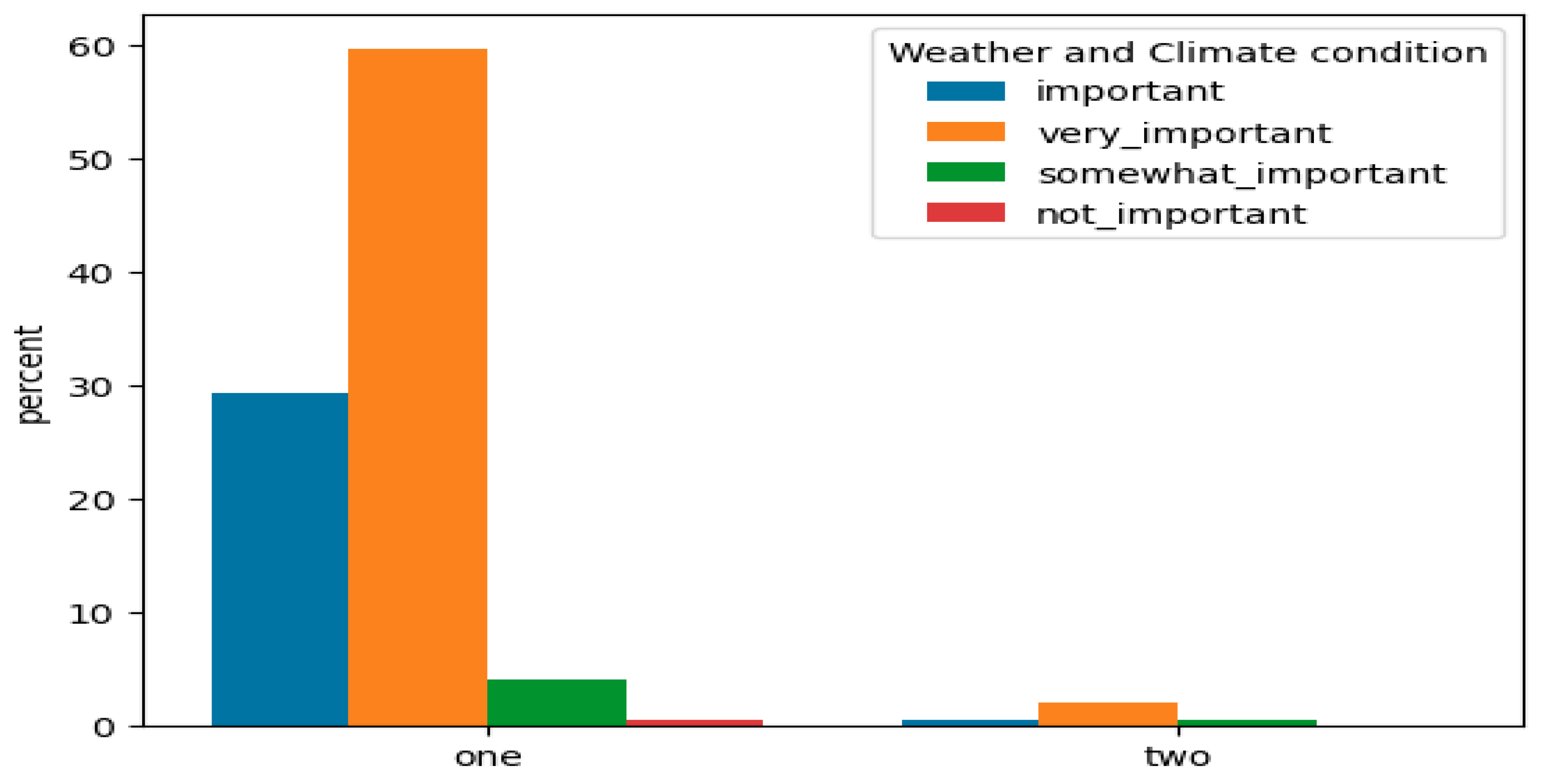

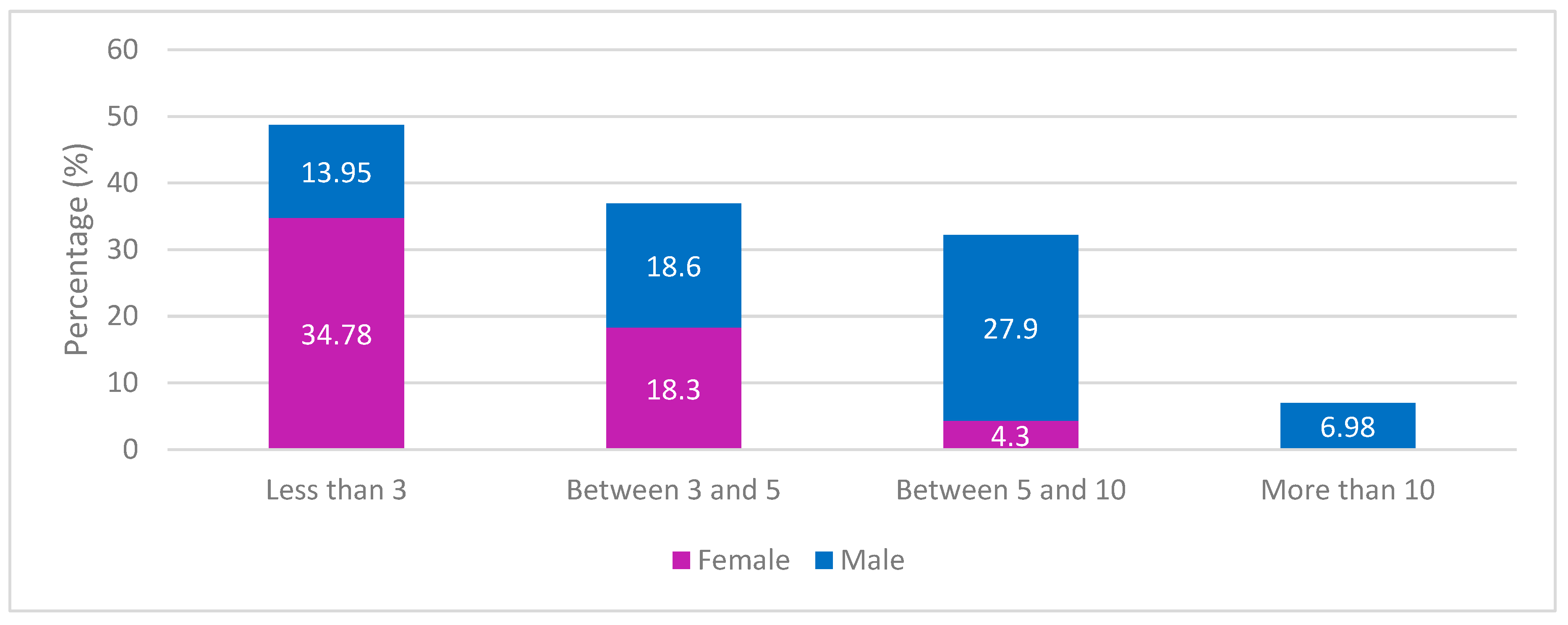

3.1.3. Determination of Scores for Sweet Potato Production Criteria

- Environmental Criteria: Cultivation and Weather/Climate Change

- Infrastructural and Operational Criteria: Land Use, Harvesting, Road Access, Vehicle Availability, and Marketability

5.2. Drought Impact Mitigation Approach for Sustainable Sweet Potato Production

3.2.1. Cultivation Practices and Climate Adaptability

3.2.2. Infrastructure and Market Access

3.2.3. Extension Services

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CRED. The interplay of drought-flood extreme events in Africa over the last twenty years (2002-2021). Crunch Newsletter, Issue No. 69. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge, C. Why was there no famine following the 1992 Southern African Drought? The Contributions and Consequences of Household Responses. IDS Bulletin 2002, 33, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaiwa, C. Zimbabwe Country Assessment Paper; SADC drought management workshop; SADC: Gaborone, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Zimbabwe Risk (Historical Hazards). 2021. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/zimbabwe/vulnerability (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Bhatasara, S. Rethinking climate change research in Zimbabwe. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2017, 7, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanza, N.; Mafongoya, P.L. Indigenous-based climate science from the Zimbabwean experience: From impact identification, mitigation and adaptation. Indigenous knowledge systems and climate change management in Africa 2017, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Nyahunda, L.; Tirivangasi, H.M. Challenges faced by rural people in mitigating the effects of climate change in the Mazungunye communal lands, Zimbabwe. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushore, T.D.; Mhizha, T.; Manjowe, M.; Mashawi, L.; Matandirotya, E.; Mashonjowa, E.; Mushambi, G.T. Climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies for small holder farmers: a case of Nyanga District in Zimbabwe. Frontiers in Climate 2021, 3, 676495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaison, C.; Reid, M.; Simatele, M.D. Asset portfolios in climate change adaptation and food security: Lessons from Gokwe South District, Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Studies 2023, 00219096231158340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Zimbabwe. National Development Strategy 1. 2023. Available online: www.zim.gov.zw.

- NDS1. National Development Strategy1 (January 2021 to December 2025), Republic of Zimbabwe. 2020.

- Mudombi, S. Adoption of agricultural innovations: the case of improved sweet potato in Wedza community of Zimbabwe. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 2013, 5, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamadzawo, G.; Wuta, M.; Nyamangara, J.; Nyamugafata, P.; Chirinda, N. Optimizing dambo (seasonal wetland) cultivation for climate change adaptation and sustainable crop production in the smallholder farming areas of Zimbabwe. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2015, 13, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makubhu, F.N.; Laurie, S.M.; Rauwane, M.E.; Figlan, S. Trends and gaps in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) improvement in sub-Saharan Africa: Drought tolerance breeding strategies. Food and Energy Security 2024, 13, e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Born-again crops give hope to Zimbabwean farmers: Ian Robertson and his colleagues have found a way to free staple crops from viruses, with dramatic results for their growers.—Free Online Library, 2004 (thefreelibrary.com).

- FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock products. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- Mudombi, S.; Mano, R.T. Analyzing incomes outcomes of incorporating improved sweet potato into the smallholder farming system: case study of Wedza community in Zimbabwe. Working Paper AEE. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zimbabwe: Harare, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mutandwa, E. Performance of Tissue-Cultured Sweet Potatoes among Smallholder Farmers in Zimbabwe. AgBioForum 2008, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, G., Ferguson, P.I., Herrera, J.E., Eds.; Product development for root and tuber crops. Volume III—Africa. Proceeding of the workshop on processing and marketing and utilization of Root and Tuber crops in Africa held October 26 to November 2, 1991 at IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria, CIP, Lima, Peru; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mpandeli, S.; Maponya, P. Constraints and challenges facing the small-scale farmers in Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibane, Z.; Soni, S.; Phali, L.; Mdoda, L. Factors impacting sugarcane production by small-scale farmers in KwaZulu-Natal Province-South Africa. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncoyini, Z.; Savage, M.J.; Strydom, S. Limited access and use of climate information by small-scale sugarcane farmers in South Africa: A case study. Clim. Serv. 2022, 26, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, F.F.; Adegbola, A.; Bamishaiye, E.I. Assessment of post-harvest challenges of small-scale farm holders of tomotoes, bell and hot pepper in some local government areas of Kano State, Nigeria. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2010, 3, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhura, M.N.; Wasike, W.S. Patterns of access to rural service infrastructure: The case of farming households in Limpopo Province. Agrekon 2003, 42, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, G.F.; King, R.P. Agricultural cooperatives II: Can they facilitate access of small-scale farmers in South Africa to input and product markets? Agrekon 2007, 46, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvediev, I.; Eliseyev, P.; Lebid, I.; Sakno, O. A modelling approach to the transport support for the harvesting and transportation complex under uncertain conditions. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 977, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaka, J.-C.B.; Gallay, O.; Hlal, M.; Mutandwa, E.; Chenal, J. Optimizing the Sweet Potato Supply Chain in Zimbabwe Using Discrete Event Simulation: A Focus on Production, Distribution, and Market Dynamics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramarico, C.L.; Mizuno, D.; Salomon, V.A.P.; Marins, F.A.S. Analytic Hierarchy Process and Supply Chain Management: a bibliometric study. Information Technology and Quantitative Management (ITQM 2015). Procedia Computer Science 2015, 55, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E.; Shu, B.; Sanchez, S.; Ray, T. Multi-criteria decision making: an operations research approach. In Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering; Webster, J.G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1998; Volume 51(1), pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sipahi, S.; Timor, M. The analytic hierarchy process and analytic network process: an overview of applications. Management Decision 2021, 48, 775–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, N.; Ganesan, K.; Srinivasan, K.; Chang, C.Y. Realizing sustainable development via modified integrated weighting MCDM model for ranking agrarian dataset. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degener, P.; Gösling, H.; Geldermann, J. Decision support for the location planning in disaster areas using multi-criteria methods. In Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference, Baden-Baden, Germany; 2013; Volume 10(1), pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Munyaka, J.-C.B.; Chenal, J.; Mabaso, S.; Tfwala, S.S.; Mandal, A.K. Geospatial Tools and Remote Sensing Strategies for Timely Humanitarian Response: A Case Study on Drought Monitoring in Eswatini. Sustainability 2024, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaka, J.C.B.; Yadavalli, V.S.S. Decision support framework for facility location and demand planning for humanitarian logistics. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag 2021, 12, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, F.; Mario, M.; Sandra, A.N. Regional landsat-based drought monitoring from 1982 to 2014. Climate 2015, 3, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, V.A.; Gouveia, C.M.; DaCamara, C.C.; Trigo, I. F A climatological assessment of drought impact on vegetation health index. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 259, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillevic, P.; Göttsche, F.; Nickeson, J.; Hulley, G.; Ghent, D.; Yu, Y.; Trigo, I.; Hook, S.; Sobrino, J.A.; Remedios, J.; et al. Land Surface Temperature Product Validation Best Practice Protocol. Version 1.1. In Good Practices for Satellite-Derived Land Product Validation; Guillevic, P., Göttsche, F., Nickeson, J., Román, M., Eds.; Land Product Validation Subgroup (WGCV/CEOS): Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.H.; Kang, C.S. Application of fuzzy decision-making method to the evaluation of spent fuel storage options. Prog Nucl Energy 2011, 39, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.Y. Applications of the extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP. Eur J Oper Res 1996, 95, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Lin, T. Application of the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process to the lead-free equipment selection decision. Bus Syst Res 2011, 5, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.J.; Jing, Y.; Chang, D.Y. A discussion on extent analysis method and applications of fuzzy AHP. Eur J Oper Res. 1999, 116, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytical hierarchy processes. McGraw Hill: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, D.; Prade, H. Fuzzy Sets and Systems: Theory and Applications. Academic Press: Boston, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Thokala, P. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health technology assessment. University of Sheffield, School of Health and Related Research,: Sheffield, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jogo, W.; Kudita, S.; Munda, E.; Chiduwa, M.; Pinkson, S.; Gwaze, T. Agronomic performance and farmer preferences for biofortified orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Zimbabwe. International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J.W.; Ortiz, R.; Vandamme, E.; Andrade, M.; Biazin, B.; Grüneberg, W.J. Nutrient-Dense Orange-Fleshed Sweetpotato: Advances in Drought-Tolerance Breeding and Understanding of Management Practices for Sustainable Next-Generation Cropping Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2020, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, N.; Mutetwa, M.; Mtaita, T. Effect of cutting position and vine pruning level on yield of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Journal of Aridland Agriculture 2019, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rethabile, K.M.; Jing, Z.; Mofolo, T.C.; Mwandiringana, E. Adaptation to Climate Change: Status, Household Strategies and Challenges in Lesotho. International Journal of Scientific Advances 2021, 2, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocher, T.; Low, J.W.; Sindi, K.; Rajendran, S. Gender-Sensitive Value Chain Intervention Improved Profit Efficiency among Orange-Fleshed Sweetpotato Producers in Rwanda. Open Agriculture 2017, 2, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, N.; Afionis, S.; Stringer, L.C.; Favretto, N.; Sakai, M.; Sakai, P. Benefits and Trade-Offs of Smallholder Sweet Potato Cultivation as a Pathway toward Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvokuomba, K.; Batisai, K. Veracity of women’s land ownership in the aftermath of land redistribution in Zimbabwe: the limits of western feminism. Agenda 2020, 34, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuriro, R.M. Land reform and local economic development: Elderly women farmers’ narratives in Shamva District, Zimbabwe. PhD Thesis, University of Johannesburg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Batisai, K. Women’s rights to own land should be prioritized. Available online: https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/opinion-analysis/womens-rights-to-own-land-should-be-prirotised-30108402 (accessed on 31 July 2019).

- Tirivangasi, H.; Dzvimbo, M.; Chitongo, L.; Mawonde, L. Present Environment and Sustainable Development. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGRITEX. Agricultural Marketing in Zimbabwe. AGRITEX: Harare, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chivinge, O.T.; Mudhara, M.; Mudzamiri, W. Sweet potato production in Zimbabwe: Constraints and opportunities. Journal of Root Crops 2000, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chivero, N.; Chirara, S. Post-harvest handling of sweet potatoes in Zimbabwe: Village and commercial practices. Zimbabwe Journal of Agricultural Research 2003, 41, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, G.J.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Ringler, C. Global projections for root and tuber crops to the year 2020. International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, D.C., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ezin, V. Sweet Potato Production and Market Potential in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Agricultural Research 2018, 12, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- ZINARA. Annual Report (2021). Enhancing Zimbabwe's Road Network. Zimbabwe National Road Administration, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MFA Transport Survey. MFA Transport Survey Report: Assessing the Challenges of Agricultural Produce Transportation in Zimbabwe. Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, E.E.; Motsa, M.M. Enhancing productivity and resilience of sweet potato farming systems in Southern Africa. Journal of Root Crops 2019, 45, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ewell, P.T.; Mutuura, J. Building the sweet potato subsector in East Africa: Technological innovation, public-private partnerships, and impact assessment. International Potato Center (CIP), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kapinga, R.E.; Zhang, D.; Mwanga, R.O.M.; Carey, E.E.; Ojiambo, P.S.; Yang, R.Y. Sweet potato: Breeding, physiology, and agronomy. In Crop Production Science in Horticulture; CAB International, 2013; Volume 18, pp. 421–459. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J.; Mwanga, R. Sweet potato: An untapped food resource. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources. 2011, 6(067), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mwanga, R.O.M.; Andrade, M. Sweet potato in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Sweet potato post-harvest assessment: Towards a research agenda; International Potato Center (CIP), 2006; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

| Drought | Values |

|---|---|

| Extreme | < 10 |

| Severe | ≥ 10, < 20 |

| Moderate | ≥ 20, < 30 |

| Mild | ≥ 30, < 40 |

| No | ≥ 40 |

| Series No | Criteria | Accronym | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Cultivation | C | This refers to the practice of propagating new plants from vine cuttings to develop new storage roots. |

| C2 | Land Use | LU | Encompasses the effective use of land for growing sweet potatoes, including preparation and cultivation techniques. |

| C3 | Harvesting | H | Involves the optimal timing and techniques for harvesting sweet potatoes to maximize yield and quality. |

| C4 | Marketability | M | Understanding market demands and standards necessary for the successful sale of sweet potatoes. |

| C5 | Road | R | Accessibility and quality of infrastructure, including roads and paths leading to and from production sites. |

| C6 | Vehicle | V | The availability and efficiency of vehicles for transporting sweet potatoes to markets or storage facilities. |

| C7 | Weather and Climate Condition | WCC | The effect of local weather patterns and climate conditions on the growth and yield of sweet potatoes. |

| Numerical values | Definition | Fuzzy triangular Scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equally Important (Eq. Imp) | (1,1,3) |

| 3 | Weakly Important (W. Imp) | (1,3,5) |

| 5 | Fairly Important (F. Imp) | (3,5,7) |

| 7 | Strongly Important (S. Imp) | (5,7,9) |

| 9 | Absolutely Important (A. Imp) | (7,9,11) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).