1. Introduction

Water is a strategic resource for the sustainability and advancement of developing countries [

1,

2]. However, climate-induced stressors such as drought increasingly threaten the well-being of communities and the sustainability of socioeconomic progress, disrupting core systems that support livelihoods, public health, ecosystems and socioeconomic development [

3]. In Zambia, water is a vital resource that sustains agriculture, hydropower generation, public health, natural ecosystems and livelihoods [

4,

5]. Yet, recurrent drought events with increasing frequency and severity threaten to undermine these essential services while compromising long-term development goals [

6,

7,

8].

The 2023/2024 drought in Zambia illustrated this vulnerability in strong terms. For instance national reports estimated crop losses of more than 40%, exacerbating hunger, increasing malnutrition, and pushing many rural households deeper into poverty [

6,

9]. Described as the worst drought in 40 years, prolonged water deficits led to severe hydropower shortages, resulting in daily blackouts lasting up to 18 hours across much of the country [

5,

10]. The energy disruptions hindered industrial productivity, escalated the cost of living, and exposed systemic weaknesses in existing infrastructure planning and emergency response [

6,

9]. These interconnected impacts demonstrate how drought in Zambia is not only a natural hazard but also a significant socioeconomic and institutional challenge [

7,

11].

Globally, the situation is no less severe. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), drought is a frequent billion-dollar disaster in the United States (U.S.) costing an estimated

$361.5 billion in losses between 1980 to 2024, and rendering it the second most expensive natural disaster in the country [

12]. Between 2008 and 2018, drought caused over

$37 billion in agricultural losses in developing nations [

11]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where the socioeconomic burden of drought is magnified by fragile infrastructure and limited adaptive capacity, at least one person is estimated to die every 48 seconds due to drought-related starvation [

3,

13]. In Zambia, these conditions are expected to worsen as climate outlooks suggest more intense and frequent droughts across the continent [

2,

14]. As a result, heightened pressure on water systems, especially for populations already struggling with food insecurity and poor access to resources is predicted [

15].

Despite the clear and growing risks posed by recurrent droughts, there remains limited understanding of the actual state of drought management in Zambia. While the country has adopted several national-level policies and strategies to address drought, their implementation has often been reactive and fragmented [

5,

7,

8,

16]. There is a tendency toward top-down approaches that prioritize short-term emergency response over long-term localized and sector-based preparedness [

17,

18]. As a result, each successive drought tends to leave deeper and more widespread impacts, particularly in rural areas where institutional capacity and resources are limited [

19,

20]. Addressing this gap requires a shift toward more integrative, inclusive, context-specific, and decentralized research and policy approaches that reflect local realities and foster long-term resilience [

3,

21,

22,

23].

A majority of existing literature on drought in Zambia and the broader Sub-Saharan Africa largely emphasizes the biophysical and climatological dimensions, such as rainfall deficits, El Niño effects, and hydrological variability [

16,

24,

25,

26]. While this research focus is essential for understanding drought hazards, it often overlooks the human and institutional factors that influence how droughts are perceived and managed on the ground [

19,

27,

28]. In particular, there is a noticeable gap in the understanding of local government entities and sector participation in key aspects of drought management [

17,

19]. This lack of insight limits the ability to design targeted interventions that leverage local knowledge, enhance institutional coordination, and build adaptive capacity at the community level [

7,

18].

Understanding the state of drought management in Zambia through the lens of local participation is important for several reasons. First, local government institutions and sector players are often the first responders to drought impacts and are uniquely positioned to interpret and act on early warning information in ways that are timely and culturally relevant [

8]. Second, meaningful participation fosters ownership of drought initiatives, increases the legitimacy of interventions, and enhances the likelihood of sustained community engagement [

28]. Third, decentralized insights can inform the design of more adaptive and responsive national policies that are better aligned with ground-level realities [

8,

17]. Without integrating the perspectives and capacities of those most affected by drought, national policies risk being misaligned, underutilized, or ineffective in practice [

22,

29].

This paper contributes to the literature by assessing the state of drought management in Zambia through the lens of the 2023/2024 drought. Specifically, it investigates the participation of local governments and sectors in drought management activities. The goal is to generate actionable insights that can guide the development of more effective, localized, inclusive, and sustainable strategies for managing drought in Zambia, sub-Sahara and southern Africa, and other similar developing-country contexts globally.

1.2. Study Area

Zambia is a landlocked country located in southern Africa, positioned between longitudes 22°E and 34°E and latitudes 8°S and 18°S. Covering a total area of approximately 752,610 km

2, the country has an estimated population of 20.8 million as of 2024, with about 61% living in rural and 39% in urban areas [

30,

31]. Zambia’s socioeconomic systems are closely tied to natural resource availability, particularly because of the country’s significant dependence on precipitation, which governs agricultural output, hydropower generation, water supply, and ecosystem health − highlighting the country’s sensitivity to drought [

4,

16,

32].

Zambia’s climate is classified under the Köppen system as primarily humid subtropical (Cwa), with stretches of tropical savanna (Aw) and semi-arid steppe (BSh) conditions. It has two main seasons: a rainy season from late October or early November to April, and a dry season from May to October. The dry season is further divided into a cool dry period (May - August) and a hot dry period (September - October) [

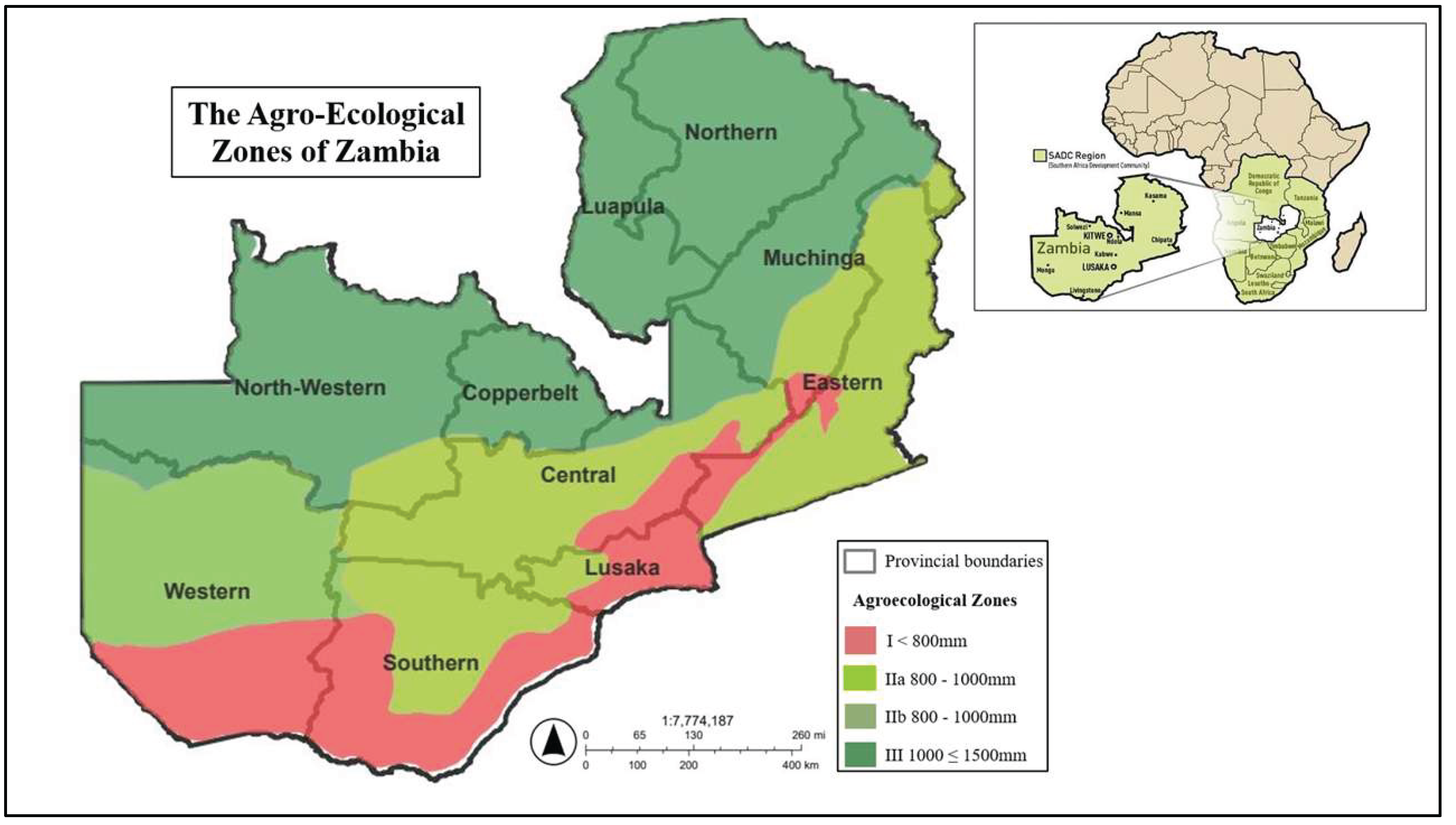

33]. Average annual precipitation ranges from 700 mm in the south to over 1,400 mm in the north (

Figure 1), with rainfall patterns largely influenced by the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone and, periodically, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [

10,

34].

To guide agricultural planning and natural resource management, Zambia is divided into three major agro-ecological zones (I, II, and III), with Zone II further subdivided into IIa and IIb based on soil type and precipitation (

Figure 1) [

10,

35]. In terms of precipitation, these zones exhibit varying vulnerabilities to drought. For example, Agro-ecological Zone I is the most drought-prone, while Zone III receives the highest precipitation and is generally more suitable for maize (staple) production and other high-yield crops [

34].

Zambia’s drought vulnerability stems from both environmental and anthropogenic factors [

32]. Seasonal and flash droughts often occur when the rainy season is delayed or delivers insufficient precipitation. Longer-term droughts are frequently associated with ENSO, which recur every four to five years and bring about prolonged dry spells across southern Africa [

4,

34]. These climatic events have been further intensified by rising temperatures, population growth, deforestation, and increasing demand on water resources [

24,

34].

Zambia’s population is currently expanding at an annual rate of 2.8% adding pressure on already stressed water systems, heightening the country’s exposure to climate-related shocks, and limiting capacity to face drought related challenges [

8,

31]. Drought conditions are further exacerbated by inadequate water storage infrastructure, overreliance on rainfed agriculture, and limited institutional capacity for climate adaptation [

4,

18,

20]. According to the World Bank and other regional assessments, Zambia is among the countries in sub-Saharan Africa most at risk from climate variability, with drought posing a top-tier threat alongside floods and epidemics [

13,

36,

37].

Historically, Zambia experiences recuring drought episodes with wide-ranging impacts. For instance, the 1981 - 1982 and 1991 - 1992 droughts caused major declines in maize production and widespread food insecurity [

38]. More recently, the 2015 -2016 and 2019 - 2020 El Niño-induced droughts resulted in severe crop failures and prolonged power shortages due to declining reservoir levels at key hydropower stations like the Kariba Dam [

39,

40]. The 2023/2024 drought (used as the reference event for this study) once again exposed the fragility of Zambia’s socio-ecological systems, as widespread agricultural losses, energy disruptions, and water shortages reverberated across the country [

6,

9].

1.3. Conceptual Background

Drought management encompasses all activities aimed at minimizing the adverse impacts of drought on people, ecosystems, and the economy [

21,

22,

41]. Unlike other natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, droughts often develop slowly over time (often described as “creeping phenomena”) making it difficult to determine their exact onset or end. This gradual nature renders drought particularly challenging to monitor and manage effectively [

16,

23]. Recently, the phenomena of “flash droughts” where drought conditions rapidly emerge in days to week with little lead time, further complicate early warning, monitoring and response efforts worldwide; in Zambia, these events are associated with delays or failures in the wet season [

34,

42]. Moreover, the widespread and cross or multi-sectoral impacts of drought, ranging from crop failure and energy shortages to food insecurity and public health crises demand integrated, and proactive approaches that cut across sectors and levels of governance [

22,

41,

42].

In practice, drought management can be reactive (response-based) or proactive (risk-based) [

21,

22,

43]. Reactive approaches focus on short-term relief during or after a drought event. While necessary, they often fail to address underlying vulnerabilities and contribute to recurring crises [

19]. Proactive approaches emphasize managing the drought risk before it becomes a disaster through deliberate mitigation and preparedness efforts [

19,

22,

43]. Although proactive approaches are preferred in literature, effective drought management requires the integration of multiple strategies to minimize impacts on communities and ecosystems [

21,

43]. A comprehensive drought strategy must balance immediate response efforts with proactive risk management measures to build long-term resilience [

43].

International frameworks, such as the Integrated Drought Management Programme (IDMP), promote a three-pillar model to guide effective drought management efforts [

22]:

Early warning and monitoring systems [

44].

Vulnerability and impact assessment [

41].

Mitigation, preparedness, and response [

21,

43].

In the Zambian context, operationalizing these three pillars is vital for balancing crisis-driven approaches with proactive drought governance [

7,

8,

19].

Using the IDMP framework, this study examines the state of drought management in Zambia by assessing local government and sector participation, with the 2023/2024 severe drought as a reference point. By focusing on participation, the study aims to contribute to the development of more proactive, integrative, inclusive, participatory, and locally grounded drought governance frameworks that can enhance resilience and long-term preparedness in Zambia and other developing countries.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a mixed-methods research design to investigate the state of drought management by assessing local/district government and sector participation in drought management activities during the 2023/2024 drought event [

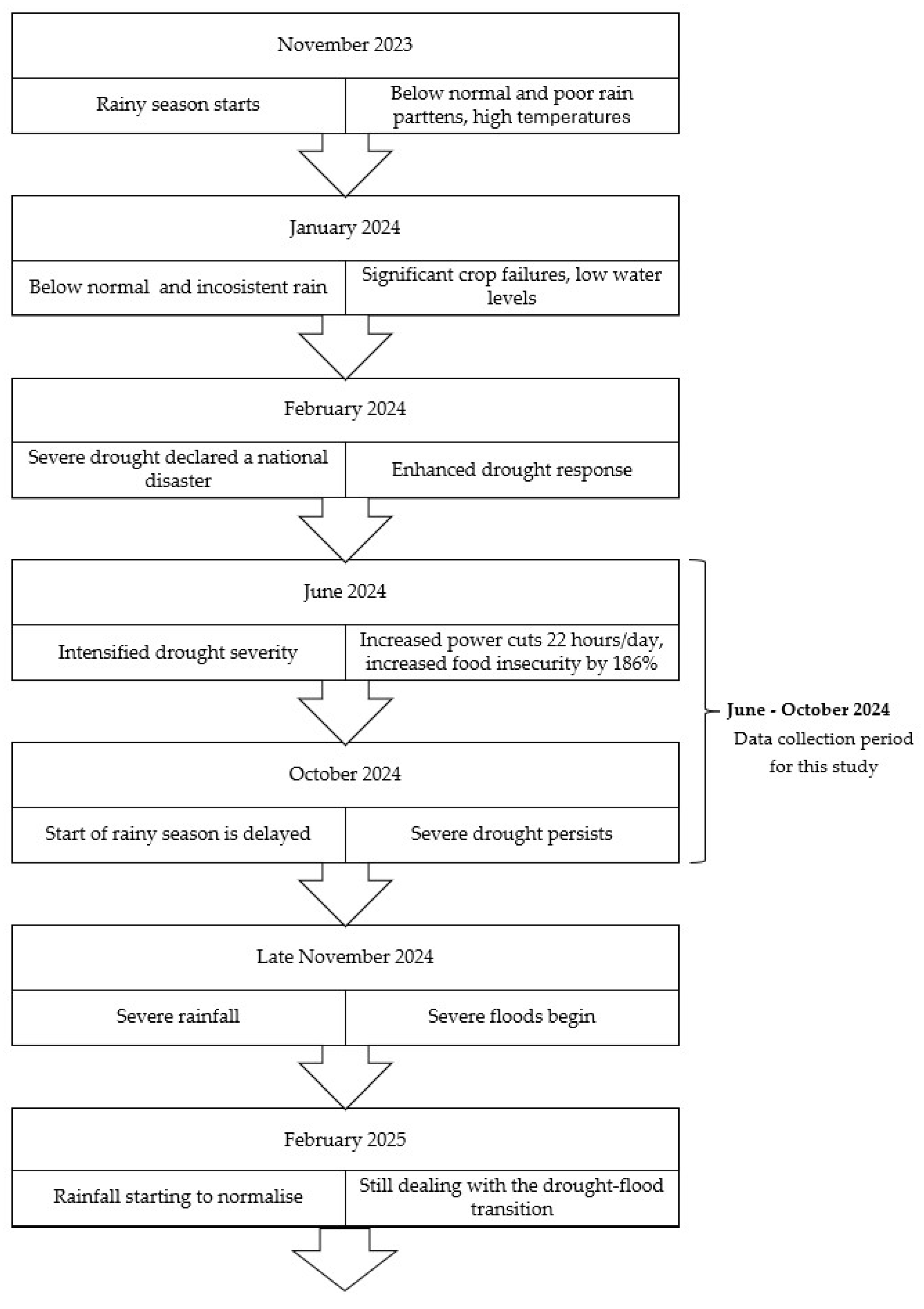

45]. Primary and secondary data were collected through interviews conducted across all 10 provinces, representing Zambia’s 4 agro-ecological zones. The qualitative approach captured real-time sector experiences and institutional perspectives during an ongoing drought (

Figure 2), while descriptive statistics complemented these findings with quantitative insights that provided a broader view of participation patterns and trends [

45]. Conducting the study amid an active drought allowed for the collection of timely, context-specific data, thereby enhancing the accuracy, reliability, and practical relevance of the findings [

45,

46].

2.1. Primary Data Collection

Primary data were obtained through semi-structured interviews conducted with 153 participants (67 district officers and 86 sector representatives) across 31 districts from all the 10 provinces of Zambia. A minimum of 3 districts were selected from each province, making up 10 urban and 21 rural districts. This rural majority was intentional, given that primary drought impacts in Zambia are predominantly rural (such as crop failures and reduced water levels in streams and rivers) [

17,

32]. Moreover, over 61% of the Zambian population resides in rural areas [

31].

To select participating districts, purposive and snowball sampling techniques were used [

45]. Initial prioritization was informed by consultations with experts from the Zambia Meteorological Department (ZMD), who identified seven provinces most impacted by the 2023/2024 drought, including Southern, Lusaka, Central, Copperbelt, Western, Eastern, and Northwestern. The remaining three, Luapula, Northern, and Muchinga provinces, while reportedly less impacted, were included to ensure national representativeness.

Both semi-structured interview questionnaires − one for district officers and one for sector representatives − were based on the three pillars of effective drought management: monitoring and early warning; vulnerability and impact assessment; and mitigation, preparedness, and response [

22,

43].

To identify district officers to participate in this study, further consultations were made with the ZMD, prioritizing officers involved in district planning, disaster management, agriculture, and water development (

Table 1). This consultation was essential to ensure the selection of officers with the most relevant responsibilities and contextual knowledge of drought management in their respective districts. ZMD’s familiarity with local institutional structures helped identify the most suitable participants. In cases where multiple officers jointly responded during an interview, their responses were recorded under a single entry.

To identify sector representatives, snowball sampling was used [

45]. During interviews with district officers, participants were asked to refer/recommend sectors and players believed to have been impacted by the 2023/2024 drought in their respective districts (

Table 1). In cases where referrals were unreachable due to communication challenges − such as discharged phones due to drought-induced power outages or unreachable remote locations − alternative participants from the same sector were recruited. This approach prioritized individuals directly impacted by drought.

2.2. Secondary Data Collection

To supplement the interpretation of primary data and provide a broader institutional context, unstructured follow-up interviews were conducted with key institutions identified through references during the primary data collection phase (

Table 2). This consultation was necessary to better understand institutional roles, coordination mechanisms, operational challenges, and perspectives on the state of existing drought risk management systems in Zambia. The insights gained were instrumental in triangulating findings, clarifying institutional references from the primary data, and contextualizing the broader policy and coordination landscape of drought risk management in Zambia.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

All participants were consulted about their willingness to participate in accordance with the University of Nebraska’s Institutional Review Board (IRB #20240623688EX, Project ID: 23688). Informed consent was obtained, and all data were anonymized to protect participant confidentiality.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis for this study was guided by a mixed-methods approach combining descriptive statistics with thematic and content analysis [

45,

47]. This analytical framework allowed for both quantitative summaries and qualitative insights from the data.

Interview responses were recorded as handwritten notes during data collection and subsequently digitized into Microsoft Excel. In accordance with ethical clearance guidelines from the University of Nebraska Institutional Review Board, all identifiable information was removed before analysis. The anonymized Excel files were uploaded into the QSR NVivo for thematic and content analysis, while descriptive statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel to compute basic frequencies and distributions.

Deductive codes were initially developed based on the three pillars of drought risk management. These codes provided a structured framework for organizing data in the QSR NVivo (

Table 3). Within each category, data were further analyzed to extract patterns and summarize key themes.

3. Results and Discussion

The main goal of this study was to assess the state of drought management by investigating the participation of government district officers and sector representatives in key areas of drought governance at the district level in Zambia. This section presents the results and discussions focusing on participation, institutional capacity, and barriers and opportunities to effective drought management in Zambia.

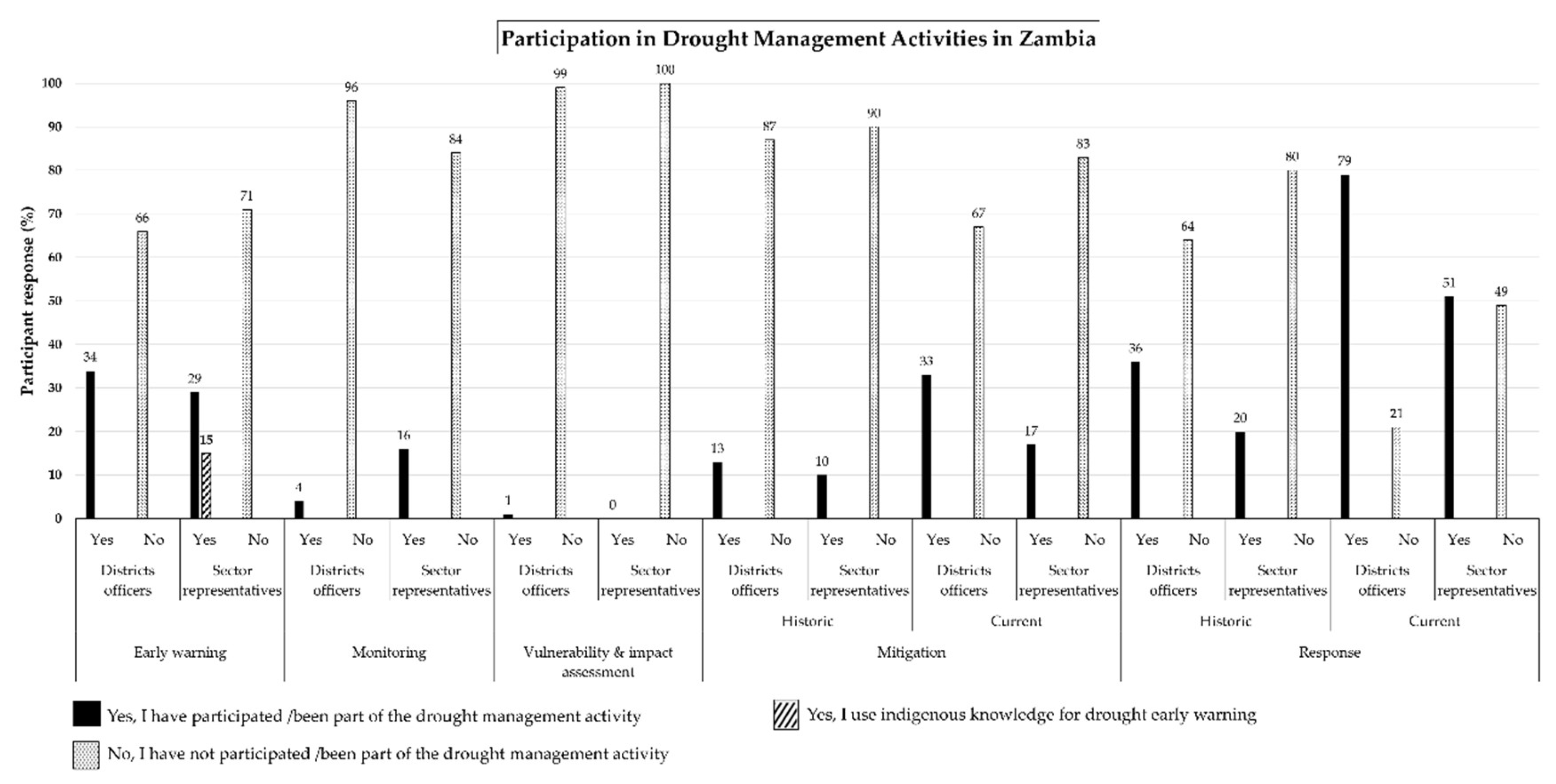

Figure 3 shows results from participant responses regarding their usage and/or participation in various drought management activities including drought early warning systems, monitoring, vulnerability and impact assessments, mitigation, response activities. Subsequent sub-sections 3.1 to 3.5, discusses the results presented in

Figure 3.

3.1. Drought Early Warning

Drought early warning systems are vital for reducing community vulnerabilities by enabling timely preparedness and proactive resource allocation [

27,

44]. However, only 34% of district officers and 29% of sector representatives reported using such systems in this study. Of the sector representatives, 15% (out of 29%) were village headmen relying on indigenous knowledge, such as:

More mosquitoes in the pre-rain season means less rain and more severe drought (Western Province).

More female human babies born in the pre-rain season means more rain and less severe drought (Southern and Central Provinces).

More seasonal wild fruits in the pre-rain season means less rain and more severe drought (Luapula, Muchinga, Northern, Northwestern, and Central Provinces).

Spiritual revelations through dreams and ancestral visitation (Western Province).

At the national level, the ZMD publishes seasonal forecasts 1-3 months ahead of the water year. Despite this effort, access and use remain limited. About 34% of district officers who reported using early warning systems noted that they accessed the ZMD forecast through their personal social media platforms or District Developmental Coordinating Committee meetings. However, there is no systematic delivery mechanism to ensure that these forecasts reach the relevant local authorities in a timely fashion. Additionally, both participant categories reported that the information in the ZMD forecast is often generalized and lacks the local district-level specificity needed for planning and decision making. Notably, the ZMD early warning forecasts do not incorporate any of the indigenous knowledge reported in this study, further limiting its resonance with local communities.

While government efforts are commendable, substantial barriers were reported, including logistical, human resources (expertise), and financial limitations. Additionally, the ZMD reported that, the lack of interest or coordination among district government offices compound existing challenges for the delivery of effective and relevant drought tools such as early warning systems. For instance, when drought information is made available via social media, such as public WhatsApp groups and Meta platforms managed by the ZMD, engagement from district officers is minimal, which undermines the potential influence of early warning tools.

Given the regional climate projections indicating more frequent and severe droughts across the continent, strengthening the reach, specificity, and usability of early warning systems is critical [

15,

44]. Enhancing collaboration among the ZMD, local/district governments, and sector players is essential to improve communication, trust, and usability of drought tools [

4,

28]. Integrating indigenous knowledge into existing early warning systems can further enhance their effectiveness, relevance and community acceptance [

48,

49]. If supported by an operational disaster risk management framework, Zambia has the opportunity to deliver more targeted, actionable early warning services that build community resilience [

7,

22].

3.2. Drought Monitoring

Drought monitoring is essential for tracking the onset, evolution, and severity of drought conditions, thereby enabling timely decisions and coordinated management of resources for response [

50,

51,

52]. This study has reviewed that local government and sector participation in drought monitoring remains extremely low in Zambia. Only 4% of district officers reported being involved in drought monitoring, primarily agricultural officers through agricultural camps and water development officers working with utility companies. Among sector representatives, only 16% reported participation, mostly limited to water supply companies tracking reservoir water levels and agricultural losses through agricultural camp stations.

While the ZMD reported that they were involved in monitoring drought using meteorological indicators and impact reports, a majority of the district officers and sector representatives reported that they were not part of any systematic drought monitoring system in their district or sector. This lack of a structured approach challenges the ability to identify when and where drought is occurring and how its severity is changing over time [

44]. Consequently, communities and decision-makers remain reactive rather than proactive, leading to delayed interventions and exacerbated social, economic, and environmental impacts. For instance, following the presidential emergency declaration during the 2023/2024 drought (

Figure 1), the Zambian government announced the allocation of funds for relief programs such as Cash for Work, aimed at providing income support to drought-affected communities. However, interview reports from this study revealed that the implementation of these relief efforts was delayed by several months. This delay meant that vulnerable households could not access critical financial assistance in time to buffer the economic shocks caused by crop losses and food price inflation. Such delays underscore how the absence of timely drought monitoring limits the ability to trigger early and efficient response mechanisms [

21].

The absence of reliable drought monitoring may also have contributed to the psychological burden of drought uncertainty, as communities struggle with anxiety stemming from a lack of actionable information [

6,

39,

50]. Similar to the early warning systems, this gap in monitoring limits the effectiveness of preparedness and response efforts. Establishing comprehensive and inclusive drought monitoring systems would strengthen the entire drought management cycle by supporting early warnings, informing mitigation strategies, and enabling coordinated responses [

42,

43,

50].

3.3. Drought Vulnerability and Impact Assessment

Assessing drought vulnerabilities is essential for identifying the specific risks, weaknesses, and adaptive capacities of communities, thereby supporting targeted and effective mitigation, preparedness, and response strategies [

41,

53]. Despite its importance, participation in drought vulnerability assessments at the local level remains critically low in Zambia. Less than 1% of district officers reported conducting some form of multi-hazard vulnerability assessment, and none of the sector representatives indicated participation. Even among the few district officers who conducted multi-hazard vulnerability assessments, outcomes from such assessments were not utilized to inform any decision making for drought management.

None of the participants were aware of any existing systematic or coordinated approach to understanding drought impacts and vulnerabilities in their districts or sectors. This lack of a structured approach creates a significant knowledge gap that weakens proactive drought preparedness [

22]. It also reflects missed opportunities to understand and address context-specific challenges, such as water shortages, crop failures, or livestock losses in the most affected areas [

53].

In 2015, the Zambian government enacted the Urban and Regional Planning Act, mandating all districts to develop and implement Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) as the principal instruments for strategic planning and resource management at the local level [

54]. Among other functions, IDPs were intended to include hazard-specific vulnerability assessments, including for drought. The Act emphasized a participatory approach, requiring input from various sector stakeholders to ensure comprehensive planning. However, findings from this study reveal a significant disconnect between policy and practice: none of the sector representatives interviewed were aware of, or had participated in, the development of IDPs in their districts. This disconnect points to policy implementation gaps, poor coordination, and a missed opportunity for proactive drought planning [

43].

The failure to utilize the IDP framework for drought vulnerability assessments may be partly attributed to the lack of immediate drought-related crises at the time of the Act’s implementation. As suggested by existing literature, communities and governments often struggle to prioritize drought preparedness in the absence of visible impacts [

38,

43,

55]. Nevertheless, Zambia has existing institutional structures at the district level, such as District Development Coordinating Committees (DDCCs), IDPs, and community-level disaster management committees, which could serve as effective platforms for assessing and addressing local drought risks. The challenge lies in operationalizing these frameworks with the intentionality and coordination necessary for building resilient Zambian communities.

3.4. Drought Mitigation and Preparedness

Drought mitigation and preparedness is critical for reducing the severity and long-term impacts of drought [

22,

43]. However, participation in mitigation efforts has historically been low in Zambia [

4,

8,

32]. In this study, only 13% of district officers participated in a drought mitigation program prior to the 2023/2024 drought. During the drought, this figure rose to 33%, indicating increased involvement spurred by the crisis. A similar pattern was observed among sector representatives, where participation increased from 10% before the drought to 17% during the event. As suggested in previous sections, this trend can be explained by the fact that, communities and governments often struggle to proactively prioritize drought mitigation and preparedness in the absence of impacts [

38,

43,

55]. Thus, participation often increases in response to the direct impacts of drought.

The reported mitigation activities include expanding water storage capacity, investing in solar energy, and promoting climate-smart agriculture through agricultural camp stations. To sustain and build on this recent momentum, systematic and localized drought planning is essential [

7,

43]. Such planning offers the structure and coordination needed to ensure that mitigation efforts are inclusive, effective, and sustainable [

22].

Further, district officer interviews revealed a concerning rise in deforestation across several provinces including Western, Central, Northwestern, Northern, and Muchinga. This deforestation is largely driven by:

Immigration of farmers from severely drought-impacted regions such as Southern Province (Agroecological Zone I) who relocate to other regions with better forage, water, and fertile land for their livestock and crops (Agroecological Zones IIa and III).

Increased reliance on charcoal as an energy source during drought-induced power outages. This trend is particularly concerning in the Northern region (Agroecological Zone III), which has extensive forest cover that plays a crucial role in maintaining Zambia’s water cycle [

16,

34,

56]. Due to widespread crop failures, many small-scale farmers have turned to charcoal production as a means of survival, accelerating environmental degradation and undermining long-term drought resilience efforts [

6,

20].

This situation underscores the importance of integrating environmental and economic sustainability into drought mitigation strategies [

32,

49]. Proactive planning can help Zambian communities anticipate such pressures and offer alternative livelihood strategies before crises escalate [

43]. For instance, protecting forests and watersheds not only safeguards biodiversity but also sustains rainfall patterns essential for agriculture and human consumption [

23,

34]. Without coordinated planning and support, reactive approaches are unlikely to address the root causes of vulnerability, making it harder to build long-term resilience [

7,

23,

28].

3.4.1. Drought Planning

Although Zambia has a national drought plan, none of the districts included in this study had developed a localized drought plan at the time of data collection. This gap highlights the predominantly top-down nature of Zambia’s drought management approach, in which districts are expected to depend on the national drought and water resource management plans for decision-making. Nevertheless, there is a strong impression for improvement; 93% of district officers and 97% of sector representatives expressed interest in developing localized drought plans that uniquely address their respective needs. Localized drought planning is vital because it promotes the incorporation of the three pillars of drought management and tailors management strategies to the unique social, economic, and ecological characteristics of individual communities [

22,

43].

Additionally, participants in this study identified a wide range of institutions involved in drought risk management at the district level, including government departments, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), private sector players, traditional authorities, and media outlets. However, collaboration among these groups was minimal and often fragmented. Localized drought planning would provide an opportunity to bring these actors together under a unified framework [

57]. District governments should consider taking a leading role in convening stakeholders, aligning efforts, avoiding duplication, and fostering more coherent and inclusive drought strategies [

57,

58].

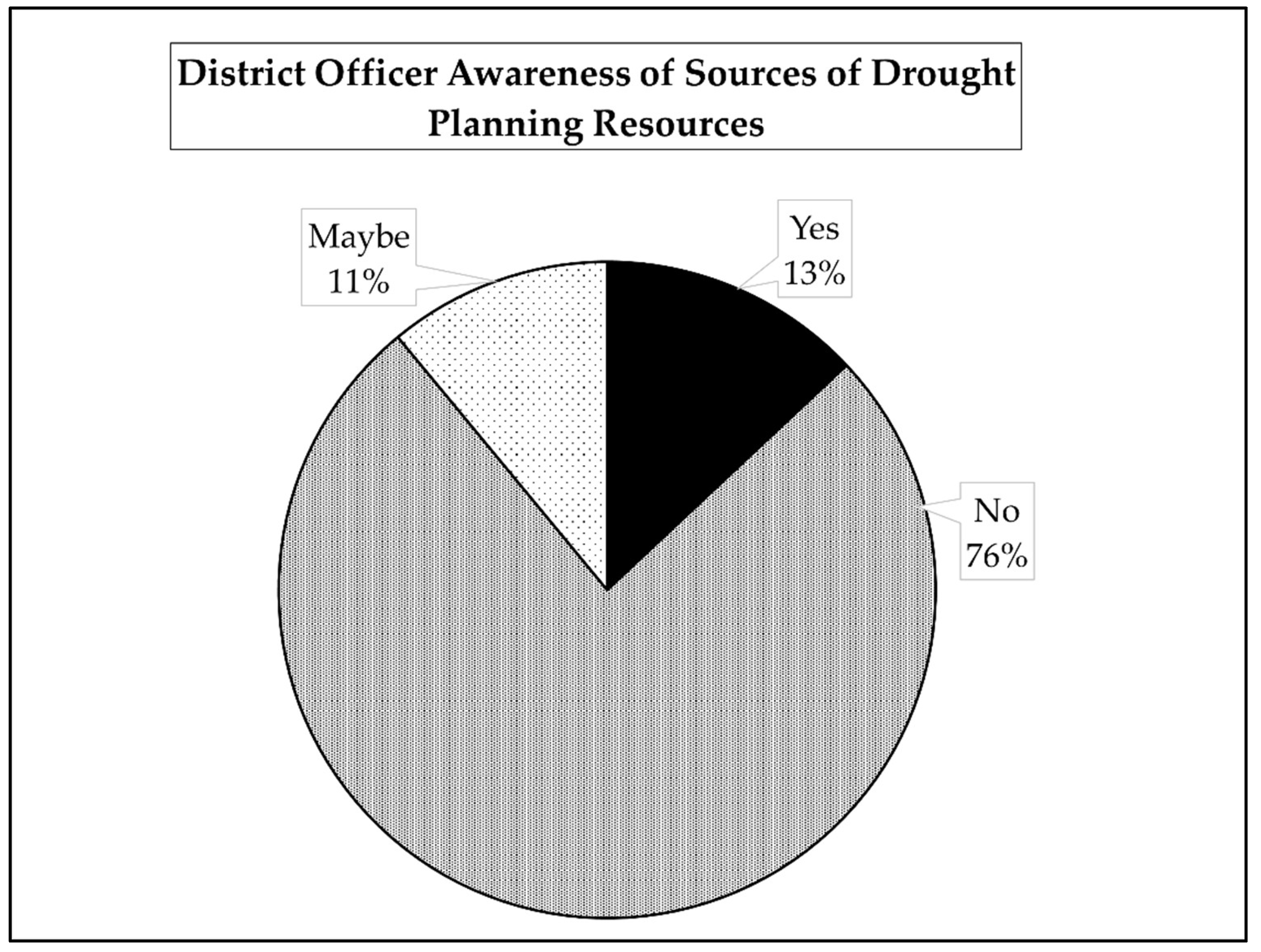

3.4.1.1. Barriers and Opportunities for Localized Drought Planning

Despite the high interest in developing local drought plans, key potential barriers were identified in this study. For instance, only 13% of district officers reported knowing where to find resources, such as funding or technical assistance for drought planning (

Figure 4). Other potential barriers include limited expertise, financial capacity, and government red tape through political interference.

While these factors are important considerations for effective drought planning, waiting for all components to be in place may delay or prevent action altogether. Districts can initiate drought planning incrementally using existing resources, local data, and indigenous knowledge. For example, districts could begin by mapping vulnerable water sources or organizing public awareness campaigns through interactive programs such as local radio and social media initiatives. Over time, such efforts can evolve into comprehensive plans supported by central government, external technical partners, NGOs, or donor agencies.

To effectively leverage limited expertise and accelerate drought planning, district governments can identify and collaborate with existing community-led platforms. Rooted in Zambia’s strong communal culture, platforms, such as traditional establishments, farmers’ cooperatives, local disaster committees, and religious or social organizations embody collective action and mutual support [

3,

19]. These networks can offer accessible and trusted spaces for mobilizing knowledge, coordinating activities, and increasing community participation in drought planning.

Rather than initiating entirely new structures, districts can consider building on what already exists to co-develop grassroots drought planning committees and foster local ownership. This approach will also enhance chances of plan implementation [

57]. For instance, in urban areas, community-led platforms could manage basic drought monitoring tools like rain gauges or lead public awareness and education campaigns.

Planning efforts can also begin with simple, community-facilitated activities, such as mapping vulnerable areas, convening communities to review and document impacts from previous droughts, identifying shared priorities, or coordinating informal workshops on drought preparedness. These efforts can gradually evolve into comprehensive drought plans that reflect the unique values and interests of subject local communities [

48].

Additionally, leveraging existing community-based platforms can reduce costs [

28,

57]. Through local forums and networks, districts can access indigenous knowledge, gather critical data, and build partnerships with NGOs, cooperatives, and donors. By recognizing and resourcing these homegrown structures, district governments can activate the social capital already in place, making drought planning more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable [

48,

49].

Community-led platforms provide a vital and underutilized foundation for localized drought planning. Empowering these structures is not only a pragmatic step in the face of resource limitations but also a culturally aligned strategy for ensuring that Zambia’s drought management is locally grounded, participatory, and future-ready [

48,

49,

57].

3.5. Drought Response

Drought response is essential for providing immediate relief to affected communities, protecting lives, livelihoods, and essential services during crisis periods [

18,

22]. Before the 2023/2024 drought, only 36% of district officers and 20% of sector representatives reported participation in response programs, most of which included food relief and farmer support. However, participation increased significantly during the drought to 79% and 51%, respectively, largely due to the presidential declaration of the drought as a national emergency, which prompted an influx of international support [

5,

6,

20].

Despite the increase, delivery of drought relief support during the 2023/2024 drought was not timely. Participants reported that response interventions, such as food-for-work and cash-for-work programs, were implemented 1-2 months before the start of the 2024/2025 rainy season (the expected start of the 2023/2024 drought recovery). This delay meant that many communities endured prolonged impacts without adequate support. Beyond the lack of local drought plans, another significant contributing factor to the non-systematic and untimely delivery of relief was the bureaucracy in government systems. District officers reported that cumbersome procurement procedures, rigid financial disbursement protocols, and multiple layers of approval created bottlenecks that made it difficult to respond swiftly to community drought response needs. Even after resources were secured following the emergency declaration, districts struggled to deploy aid efficiently due to centralized decision-making and the limitation of delegated authority at the local level.

These inefficiencies highlight the urgent need for localized drought planning that empowers district governments to act quickly and decisively. A well-structured local drought plan could clearly outline processes for mobilizing and allocating resources in a drought crisis, reduce administrative delays, and enable communities to access support when they need it most. By decentralizing drought response authority and embedding action protocols within district-level planning, Zambia can improve the speed, coordination, and equity of relief delivery during future droughts [

22,

57].

Additionally, while most aid targeted agriculture and water supply, other critical sectors like small and medium enterprises (SMEs), tourism, health, and energy were overlooked. SME representatives described severe disruptions to their businesses due to power outages and water shortages, yet none were included in relief programs. For instance, a small metal fabrication business owner reported working for less than two hours after midnight due to erratic power supply, while a butchery owner had to close shop after failing to refrigerate their merchandise. These cases reveal a significant gap in inclusive response planning and underscore the need for vulnerability assessments to capture the full range of sectors affected by drought [

21,

41].

A comprehensive drought response strategy should not only deliver timely aid but also address the multidimensional impacts of drought across all sectors [

43,

48]. Building this capacity at the local level requires proactive drought planning, accurate vulnerability knowledge, and clear coordination mechanisms to improve community resilience [

28,

43,

57].

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study investigated the state of drought management in Zambia by assessing the participation of district officers and sector representatives across key components of drought management including early warning, monitoring, vulnerability and impact assessment, mitigation and preparedness, and response. Findings revealed a pattern of limited proactive participation in drought management, with most activities occurring only in reaction to severe impacts, such as those experienced during the 2023/2024 drought. This reactive approach is further characterized by a lack of systematic strategies to drought management, poor coordination, and systemic bureaucratic constraints that undermine effective response and long-term resilience.

Firstly, participation in drought early warning systems remained low, with only 34% of district officers and 29% of sector representatives indicating usage of any early warning mechanisms. Despite the availability of seasonal forecasts from the ZMD, their underutilization stems from issues related to accessibility, lack of local relevance, and poor coordination among government institutions. Furthermore, although 15% of sector representatives reported relying on indigenous knowledge for early warning, this resource is not included in existing formal systems, diminishing the local and cultural relevance, inclusivity, and practical reach of national early warning frameworks.

Similarly, participation in drought monitoring was notably low, with only 4% of district officers and 16% of sector representatives monitoring drought. The lack of systematic monitoring frameworks left communities exposed to drought hazards and weakened the ability to initiate timely and effective responses. Notably, during the 2023/2024 drought, government response interventions were significantly delayed, leaving communities to endure severe hardships. This demonstrates how poor monitoring, and inadequate planning can critically undermine the delivery of emergency support [

22,

41].

Drought vulnerability and impact assessments were nearly nonexistent at the district level, with fewer than 1% of district officers and 0% of sector representatives reporting participation. This critical gap contributes to an incomplete understanding of the impacts of drought across sectors and geographies and further weakens the ability to prioritize communities in the distribution of drought relief [

6,

18]. It also explains why certain sectors, like SMEs and tourism, were not considered in drought response programs despite experiencing significant disruptions.

Participation in drought mitigation activities was marginal before the 2023/2024 drought. Only 13% among district officers and 10% among sector representatives, but rose to 33% and 17%, respectively, during the drought. While this increase reflects heightened awareness triggered by the crisis, it also underscores Zambia’s heavy reliance on reactive rather than proactive strategies [

21]. The crisis-driven increase in mitigation efforts, combined with an increase in deforestation due to energy and income disruptions, points to the need for integrated planning that addresses both environmental sustainability and socioeconomic resilience [

7,

21,

22,

40].

Similarly, participation in drought response programs increased significantly from-before-and during the 2023/2024 drought, rising from 36% to 79% among district officers and from 20% to 51% among sector representatives. However, poor planning, red tape, and centralized decision-making significantly affected the delivery and equitable distribution of aid to local communities. For instance, the small and medium enterprises sector, widely acknowledged as a cornerstone of Zambia’s economy was among the most severely impacted sectors [

5,

20]. Yet, this study found that the sector was not included in the formal drought response programs. This omission highlights the consequences of not conducting vulnerability assessments and the absence of localized drought plans [

43,

57].

Additionally, none of the districts included in this study had localized drought plans. Although, 93% of district officers and 97% of sector representatives expressed a strong interest in developing local drought plans. Local drought planning is essential for tailoring risk management to community-specific vulnerabilities, fostering coordination among actors, reducing bureaucratic delays, and empowering communities through locally and culturally grounded, cost-effective, and participatory strategies [

7,

57].

This study concludes that Zambia’s current drought management strategy is predominantly reactive, non-participatory, and vulnerable to administrative inefficiencies. To shift from the reactive to more integrative drought management approaches that incorporate proactive and risk-based strategies, Zambia should consider the following:

4.1. Strengthen and Localize Early Warning and Monitoring Systems

To improve drought preparedness, Zambia must strengthen the reach, specificity, and usability of early warning and monitoring systems [

44]. This includes increasing investment in the ZMD to enhance its technical capacity and operational reach. Stronger collaboration between ZMD, district authorities, and sector stakeholders is essential to build trust and improve communication [

14,

44]. Integrating indigenous knowledge into official warning systems will improve cultural relevance, increase community trust, and promote timely action [

48]. These efforts must be supported by a systematic and robust disaster risk management framework to ensure delivery of actionable, localized information.

4.2. Institutionalize Vulnerability and Impact Assessments

Drought vulnerability assessments should be institutionalized within district-level planning through facilities such as the IDP framework. These assessments are critical for identifying at-risk populations, understanding sector-specific vulnerabilities, and designing targeted interventions such as drought-tolerant crops or community reservoirs [

41,

58]. Institutionalizing this process will help Zambia align district development goals with climate risk reduction and ensure that resource allocation and planning are responsive to the realities on the ground.

4.3. Promote Decentralized and Risk-Based Drought Planning

Zambia should empower local governments to lead in drought planning and decision-making. This includes resourcing and institutionalizing localized drought planning that integrates the three core pillars of effective drought management; early warning and monitoring, vulnerability and impact assessments, and mitigation and response [

22,

43]. Districts should be supported to tailor plans to their unique social, economic, and ecological conditions. This local empowerment fosters faster decision-making, improves responsiveness, and reduces dependence on top-down directives.

4.4. Leverage Community Networks to Deepen Participation and Ownership

Zambia should harness the power of existing community-led platforms, traditional authorities, and grassroots networks as trusted and accessible entry points for drought planning and implementation. These structures not only offer practical avenues for collecting indigenous knowledge and facilitating dialogue but also enable more cost-effective and inclusive participation in decision-making processes [

49]. Strengthening local engagement fosters trust, builds legitimacy, and ensures that drought strategies reflect community realities. These platforms can enhance coordination between residents, sector stakeholders, and government institutions − reducing duplication of efforts and improving the quality of interventions [

48]. By leveraging these networks, Zambia can foster shared ownership of drought management while reinforcing the social fabric needed for long-term resilience [

57,

58].

4.5. Reduce Bureaucratic Bottlenecks in Drought Response

Reducing bureaucratic red tape will enhance the efficiency of drought responses at the local level [

27]. Clear delegation of authority, simplified procurement protocols, and transparent budget disbursement mechanisms are critical for ensuring timely delivery of relief. Empowering district administrations with financial and operational autonomy will allow communities to respond swiftly to drought emergencies and reduce delays in relief distribution.

4.6. Invest in Capacity Building and Infrastructure

National and district-level institutions require sustained investment to develop drought expertise and infrastructure [

57]. Increasing budgetary allocations to key actors like the ZMD and local planning units will enhance data quality, improve forecasting accuracy, and support decision-making. Training programs, equipment upgrades, and digital platforms can also improve coordination, data sharing, and operational readiness at all levels of government.

By adopting a more proactive, decentralized, and inclusive approach to drought management, Zambia can move from short-term crisis-based emergency responses to long-term resilience building, thereby strengthening communities, ecosystems, and institutions in the face of increasing climate variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., M.H., D.B., K.S., R.M., and E.J. ; methodology, A.M., M.H., D.B., and K.S.; software, A.M., and M.H. ; validation, A.M., M.H., D.B., K.S., R.M., and E.J. ; formal analysis, A.M., and M.H. ; investigation, A.M., M.H., D.B., K.S., R.M., and E.J. ; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. ; writing—review and editing, A.M., M.H., D.B., K.S., R.M., and E.J. ; visualization, A.M. ; supervision, M.H., D.B., K.S., R.M., and E.J.; funding acquisition, A.M., and M.H.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources (IANR), School of Natural Resources (SNR), National Drought mitigation Center (NDMC) of the University of Nebraska−Lincoln.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available due to their identifiable nature. This is in line with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Government of the Republic of Zambia, through its various ministries and departments, for granting the necessary permissions and providing institutional support that contributed to the successful execution of this study. Special thanks are extended to the Zambia Meteorological Department (ZMD) for their collaboration and valuable insights throughout the research process. The authors also sincerely thank the district officers and all sector representatives across the ten provinces for their time, openness, and willingness to participate in this study. Their contributions were essential to understanding the state of drought risk management in Zambia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agoungbome SMD, ten Veldhuis MC, van de Giesen N. Safe Sowing Windows for Smallholder Farmers in West Africa in the Context of Climate Variability. Climate. 2024 Mar;12(3):44.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 12]. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)). Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2022-impacts-adaptation-and-vulnerability/161F238F406D530891AAAE1FC76651BD.

- Machete KC, Senyolo MP, Gidi LS. Adaptation through Climate-Smart Agriculture: Examining the Socioeconomic Factors Influencing the Willingness to Adopt Climate-Smart Agriculture among Smallholder Maize Farmers in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Climate. 2024 May;12(5):74.

- Waldman KB, Vergopolan N, Attari SZ, Sheffield J, Estes LD, Caylor KK, et al. Cognitive biases about climate variability in smallholder farming systems in Zambia. Weather, Climate, and Society. 2019;11(2):369–383.

- ZNBC. Zambia to conclude drought emergency response programme in April 2025 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=122128258448636867&set=zambia-to-conclude-drought-emergency-response-programme-in-april-2025reported-by.

- ACAPS. Zambia: Update on the impact of drought. [Internet]. 2025 Jan. (Zambia: Update on the impact of drought). Available from: https://www.acaps.org/fileadmin/Data_Product/Main_media/20250116_ACAPS_Zambia_-_Update_on_the_impact_of_drought_.pdf.

- Banda B, van Niekerk D, Nemakonde L, Granvorka C. Legal and policy frameworks to harmonize and mainstream climate and disaster resilience options into municipality integrated development plans: A case of Zambia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022 Oct 15;81:103269.

- Ngoma H, Lupiya P, Kabisa M, Hartley F. Impacts of climate change on agriculture and household welfare in Zambia: an economy-wide analysis. Climatic Change. 2021 Aug 27;167(3):55.

- Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 11]. Zambia declares national disaster after drought devastates agriculture. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/29/zambia-declares-national-disaster-after-drought-devastates-agriculture.

- ZMD. Zambia Meteorological Department Weather [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61556313256348.

- FAO. www.fao.org. 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 13]. Damages and losses - Drought. Available from: https://www.fao.org/interactive/disasters-in-agriculture/en/.

- NCEI. U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980 - present (NCEI Accession 0209268) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.nodc:0209268.

- Oxfam. Oxfam International. 2022 [cited 2024 Dec 13]. One person likely dying from hunger every 48 seconds in drought-ravaged East Africa as world again fails to heed warnings. Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/one-person-likely-dying-hunger-every-48-seconds-drought-ravaged-east-africa-world.

- Tangney P. Understanding climate change as risk: a review of IPCC guidance for decision-making. Journal of Risk Research. 2020 Nov 1;23(11):1424–39.

- IPCC. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 13]. p. 1513–766. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2021-the-physical-science-basis/weather-and-climate-extreme-events-in-a-changing-climate/5BCB24C5699F1D42B2DE379BDD4E2119.

- Libanda B, Mie Z, Ngonga C. Spatial and temporal patterns of drought in Zambia. Journal of Arid Land. 2019 Mar 13;11.

- Nswana A, Simuyaba E. Challenges Which Hinder Citizen Participation in Governance Affairs in Nalusanga Zone, Mumbwa District, Zambia. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science. 2021 Jan 1;05:152–8.

- UN. United Nations Zambia. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 13]. Zambia: Drought Response Appeal May 2024 - December 2024 (May 2024) | United Nations in Zambia. Available from: https://zambia.un.org/en/268038-zambia-drought-response-appeal-may-2024-december-2024-may-2024, https://zambia.un.org/en/268038-zambia-drought-response-appeal-may-2024-december-2024-may-2024.

- Dumenu WK, Takam Tiamgne X. Social vulnerability of smallholder farmers to climate change in Zambia: the applicability of social vulnerability index. SN Appl Sci. 2020 Feb 18;2(3):436.

- WFP. WFP Zambia Country Brief, September 2024 - Zambia | ReliefWeb [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 23]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/wfp-zambia-country-brief-september-2024.

- Fu X, Svoboda M, Tang Z, Dai Z, Wu J. An overview of US state drought plans: Crisis or risk management? Natural Hazards. 2013 Dec;69(3):1607–27.

- IDMP. Integrated Drought Management Programme [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2024 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.droughtmanagement.info/.

- Vogel C, Koch I, Van Zyl K. “A persistent truth”-reflections on drought risk management in Southern Africa. Weather, Climate, and Society. 2010;2(1):9–22.

- Collins JM. Temperature variability over Africa. Journal of Climate. 2011;24(14):3649–3666.

- Novella NS, Thiaw WM. African rainfall climatology version 2 for famine early warning systems. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 2013;52(3):588–606.

- Tarekegn GB, Alaminie AA, Debele SE. Linking Climate Change Information with Crop Growing Seasons in the Northwest Ethiopian Highlands. Climate. 2023 Dec;11(12):243.

- Cravens AE, Henderson J, Friedman J, Burkardt N, Cooper AE, Haigh T, et al. A typology of drought decision making: Synthesizing across cases to understand drought preparedness and response actions. Weather and Climate Extremes. 2021 Sep 1;33:100362.

- Grainger S, Murphy C, Vicente-Serrano SM. Barriers and Opportunities for Actionable Knowledge Production in Drought Risk Management: Embracing the Frontiers of Co-production. Frontiers in Environmental Science [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Feb 20];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2021.602128.

- Hügel S, Davies AR. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: A review of the research literature. WIREs Climate Change. 2020 Jul;11(4):e645.

- Nkhuwa DC, Kang’omba S. British Geological Survey. 2018 [cited 2023 May 29]. Hydrogeology of Zambia - MediaWiki. Available from: https://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Hydrogeology_of_Zambia#Climate.

- Worldometer. Worldometer. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 11]. Zambia Population (2025). Available from: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/zambia-population/.

- Winton RS, Teodoru CR, Calamita E, Kleinschroth F, Banda K, Nyambe I, et al. Anthropogenic influences on Zambian water quality: hydropower and land-use change. Environ Sci: Processes Impacts. 2021 Jul 21;23(7):981–94.

- Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 2007 Oct 11;11(5):1633–44.

- Musonda B, Jing Y, Iyakaremye V, Ojara M. Analysis of Long-Term Variations of Drought Characteristics Using Standardized Precipitation Index over Zambia. Atmosphere. 2020 Dec;11(12):1268.

- O’Neill B. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Agro-ecological regions of Zambia. Available from: https://gaez.fao.org/datasets/99365aaf48824fef988c4c1f632b81c6_0/explore.

- OCHA UN. Southern Africa: El Niño Regional Humanitarian Overview, September 2024 | OCHA [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/mozambique/southern-africa-el-nino-regional-humanitarian-overview-september-2024.

- WBG. World Bank. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 16]. Water in Eastern and Southern Africa. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/brief/water-in-afe-eastern-southern-africa.

- Kajoba GM. The Impact of the 1991/92 Drought in Zambia. In: Ahmed AGM, Mlay W, editors. Environment and Sustainable Development in Eastern and Southern Africa: Some Critical Issues [Internet]. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 1998 [cited 2023 Jun 4]. p. 190–206. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26643-2_13.

- Plan International. Drought crisis has critical consequences for millions in Zambia [Internet]. Plan International Zambia. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://plan-international.org/zambia/news/2024/07/12/drought-crisis-critical-consequences-millions-zambia/.

- Tendai Marima. Drought adds fuel to fire as Zambia loses battle to save forests. Reuters [Internet]. 2016 Feb 25 [cited 2023 Jun 3]; Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-africa-drought-zambia-deforestation-idUKKCN0VY2A0.

- Hayes MJ, Wilhelmi OV, Knutson CL. Reducing Drought Risk: Bridging Theory and Practice. Natural Hazards Review. 2004;5(2):106–113.

- Otkin JA, Svoboda M, Hunt ED, Ford TW, Anderson MC, Hain C, et al. Flash Droughts: A Review and Assessment of the Challenges Imposed by Rapid-Onset Droughts in the United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2018 May 1;99(5):911–9.

- Wilhite D. Managing drought risk in a changing climate. Clim Res. 2016;70(2–3):99–102.

- Tadesse T, Wall N, Hayes M, Svoboda M, Bathke D. Improving national and regional drought early warning systems in the greater horn of Africa. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2018;99(8):ES135–ES138.

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2018. 305 p.

- Taylor JG, Stewart TR, Downton M. Perceptions of Drought in the Ogallala Aquifer Region. Environment and Behavior. 1988 Mar 1;20(2):150–75.

- Saldana J. Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life. SAGE Publications; 2016. 474 p.

- Ciocco TW, Miller BW, Tangen S, Crausbay SD, Oldfather MF, Bamzai-Dodson A. Indigenous knowledge in climate adaptation planning: reflections from initial efforts. Front Clim [Internet]. 2024 Nov 8 [cited 2025 Mar 19];6. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/climate/articles/10.3389/fclim.2024.1393354/full.

- Kasali G. Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge Systems for Climate Change Adaptation in Zambia. In: Leal Filho W, editor. Experiences of Climate Change Adaptation in Africa [Internet]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2011 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. p. 281–95. (Climate Change Management). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22315-0_18.

- Naumann G, Barbosa P, Carrao H, Singleton A, Vogt J. Monitoring drought conditions and their uncertainties in Africa using TRMM data. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 2012;51(10):1867–1874.

- Sheffield J, Wood EF, Chaney N, Guan K, Sadri S, Yuan X, et al. A drought monitoring and forecasting system for sub-sahara african water resources and food security. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2014;95(6):861–882.

- Svoboda M, LeComte D, Hayes M, Heim R, Gleason K, Angel J, et al. The Drought Monitor. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2002 Aug 1;83(8):1181–90.

- Funk C, Shukla S. Chapter 6 - Tools of the trade 3—mapping exposure and vulnerability. In: Funk C, Shukla S, editors. Drought Early Warning and Forecasting [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020 [cited 2023 Jul 31]. p. 83–99. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128140116000063.

- FAO. Urban and Regional Planning Act, 2015 (No. 3 of 2015). [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC171652/.

- Wlostowski AN, Jennings KS, Bash RE, Burkhardt J, Wobus CW, Aggett G. Dry landscapes and parched economies: A review of how drought impacts nonagricultural socioeconomic sectors in the US Intermountain West. WIREs Water. 2022;9(1): e1571.

- Sichingabula H. Rainfall variability, drought and implications of its impacts on Zambia, 1886-1996. 1998 [cited 2023 May 30]; Available from: http://dspace.unza.zm/handle/123456789/7208.

- Haigh T, Wickham E, Hamlin S, Knutson C. Planning Strategies and Barriers to Achieving Local Drought Preparedness. Journal of The American Planning Association. 2022 Jul 5;1–15.

- Wickham ED, Bathke D, Abdel-Monem T, Bernadt T, Bulling D, Pytlik-Zillig L, et al. Conducting a drought-specific THIRA (Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment): A powerful tool for integrating all-hazard mitigation and drought planning efforts to increase drought mitigation quality. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2019;39 (January): 101227.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).