Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample and Research Context

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Measurement Model

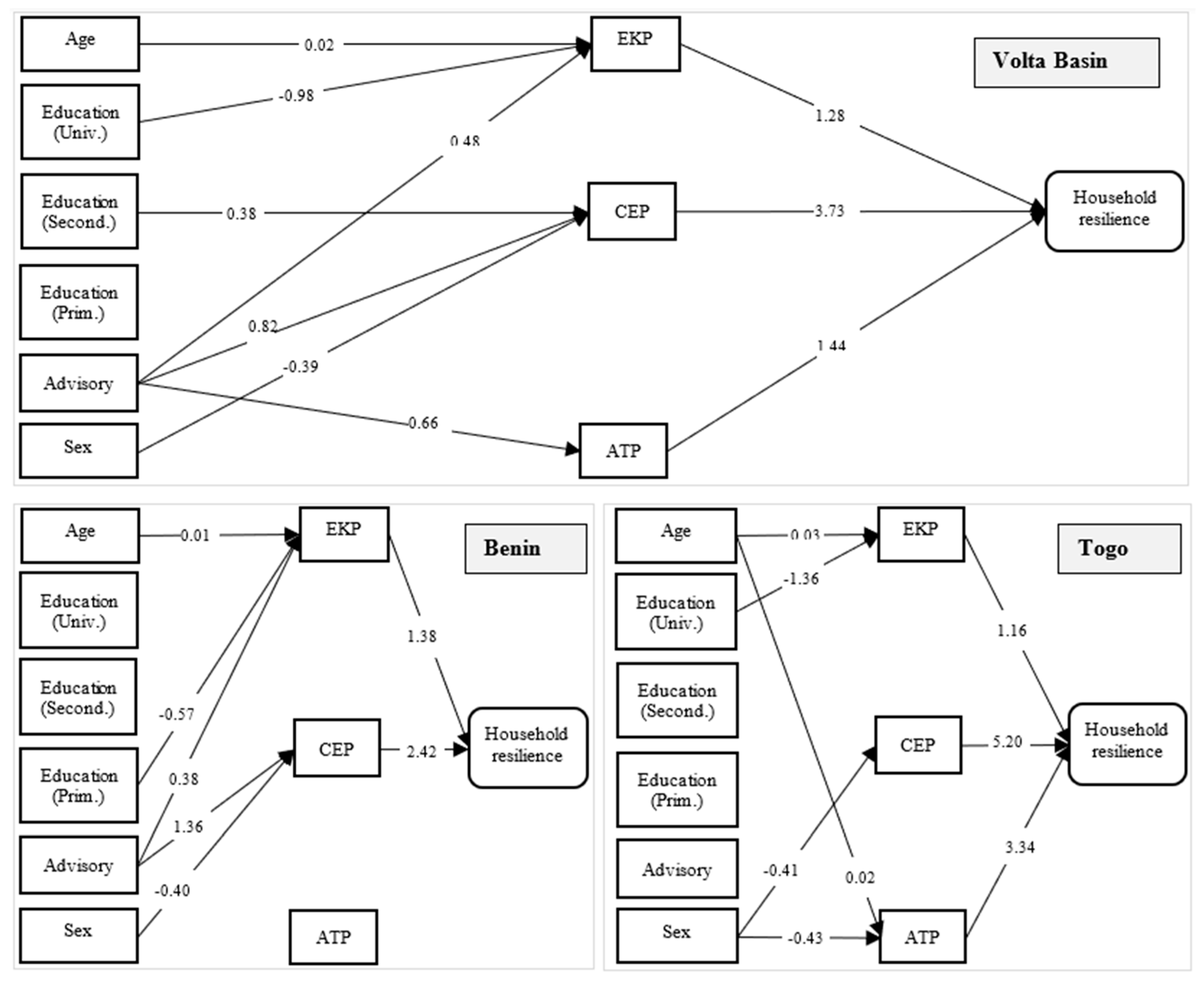

3.3. Structural Relationships

| Dep | Pred | Volta Basin | Benin | Togo | |||

| Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | ||

| EKP | Sex1 (Male) | -0.01 | 0.971 | 0.02 | 0.93 | -0.06 | 0.783 |

| EKP | Education1 (Primary) | -0.26 | 0.144 | -0.57 | 0.023 | 0.04 | 0.871 |

| EKP | Education2 (Secondary) | -0.10 | 0.647 | -0.15 | 0.616 | -0.38 | 0.353 |

| EKP | Education3 (University) | -0.98 | 0.036 | -0.48 | 0.527 | -1.36 | 0.022 |

| EKP | Advisory1 (Yes) | 0.48 | < .001 | 0.38 | 0.019 | 0.24 | 0.368 |

| EKP | Age | 0.02 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.023 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| CEP | Sex1 (Male) | -0.39 | 0.002 | -0.40 | 0.021 | -0.41 | 0.026 |

| CEP | Education1 (Primary) | 0.13 | 0.373 | -0.01 | 0.961 | 0.18 | 0.384 |

| CEP | Education2 (Secondary) | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.109 | 0.20 | 0.528 |

| CEP | Education3 (University) | 0.16 | 0.654 | 0.18 | 0.687 | -0.08 | 0.875 |

| CEP | Advisory1 (Yes) | 0.82 | < .001 | 1.36 | < .001 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| CEP | Age | -3.81e−4 | 0.929 | 0.00 | 0.568 | 0.00 | 0.531 |

| ATP | Sex1 (Male) | -0.25 | 0.087 | 0.15 | 0.132 | -0.43 | 0.047 |

| ATP | Education1 (Primary) | -0.26 | 0.131 | -0.21 | 0.071 | 0.12 | 0.596 |

| ATP | Education2 (Secondary) | 0.18 | 0.373 | -0.07 | 0.701 | -0.07 | 0.839 |

| ATP | Education3 (University) | -0.58 | 0.184 | 0.32 | 0.184 | -0.69 | 0.153 |

| ATP | Advisory1 (Yes) | 0.66 | < .001 | -0.08 | 0.315 | 0.45 | 0.062 |

| ATP | Age | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.755 | 0.02 | 0.039 |

| Resilience | EKP | 1.28 | 0.001 | 1.38 | 0.011 | 1.16 | 0.042 |

| Resilience | CEP | 3.73 | < .001 | 2.42 | < .001 | 5.20 | < .001 |

| Resilience | ATP | 1.44 | 0.002 | -1.50 | 0.194 | 3.34 | < .001 |

4. Concluding Discussion

4.1. Factors Affecting Flood Management Practices in the Volta Basin

4.2. Impacts of Flood Management Practices on Household Resilience in Volta Basin

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adelekan, I. Vulnerability Assessment of an Urban Flood in Nigeria: Abeokuta Flood 2007. Natural Hazards 2010, 56, 215–231, doi:10.1007/s11069-010-9564-z. [CrossRef]

- Salami, R.O.; Meding, J.K. v.; Giggins, H. Vulnerability of Human Settlements to Flood Risk in the Core Area of Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria. Jàmbá Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2017, 9, doi:10.4102/jamba.v9i1.371. [CrossRef]

- Olajide, O.; Lawanson, T. Climate Change and Livelihood Vulnerabilities of Low-Income Coastal Communities in Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 2014, 6, 42–51, doi:10.1080/19463138.2013.878348. [CrossRef]

- Bwanali, W.; Manda, M. The Correlation Between Social Resilience and Flooding in Low-Income Communities: A Case of Mzuzu City, Malawi. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2023, 14, 495–513, doi:10.1108/ijdrbe-09-2022-0093. [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, A.; Birkmann, J.; Feldmeyer, D.; Rana, I.A. A Conceptual Framework to Understand the Dynamics of Rural–Urban Linkages for Rural Flood Vulnerability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2894, doi:10.3390/su12072894. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.M.; James, H. Measuring Household Resilience to Floods: A Case Study in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta. Ecology and Society 2013, 18, doi:10.5751/es-05427-180313. [CrossRef]

- Owusu, K.; Obour, P.B. Urban Flooding, Adaptation Strategies, and Resilience: Case Study of Accra, Ghana. In African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation; Oguge, N., Ayal, D., Adeleke, L., Da Silva, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 2387–2403 ISBN 978-3-030-45105-9.

- Ashenefe, B.; Wubshet, M.; Shimeka, A. Household Flood Preparedness and Associated Factors in the Flood-Prone Community of Dembia District, Amhara National Regional State, Northwest Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2017, Volume 10, 95–106, doi:10.2147/rmhp.s127511. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Ajiang, C.; Khan, N.A.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Muhammad Atiq Ur Rehman Tariq Flood Risk Perception and Its Attributes Among Rural Households Under Developing Country Conditions: The Case of Pakistan. Water 2022, 14, 992, doi:10.3390/w14060992. [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Morgan, G.B. A Comparison of Diagonal Weighted Least Squares Robust Estimation Techniques for Ordinal Data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2014, 21, 425–438, doi:10.1080/10705511.2014.915373. [CrossRef]

- Izah, S.C.; Sylva, L.; Hait, M. Cronbach’s Alpha: A Cornerstone in Ensuring Reliability and Validity in Environmental Health Assessment. ES Energy & Environment 2023, 23, 1057.

- Savalei, V. Improving Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling with Categorical Data. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2021, 56, 390–407, doi:10.1080/00273171.2020.1717922. [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural Equations Modeling: Fit Indices, Sample Size, and Advanced Topics. Journal of consumer psychology 2010, 20, 90–98.

- Bwambale, B.; Muhumuza, M.; Nyeko, M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Flood Risk Management: A Preliminary Case Study of the Rwenzori. Jàmbá Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2018, 10, doi:10.4102/jamba.v10i1.536. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.L.; Basnet, A. Managing Disasters Integrating Traditional Knowledge and Scientific Knowledge Systems: A Study From Narayani Basin, Nepal. Disaster Prevention and Management an International Journal 2022, 31, 361–373, doi:10.1108/dpm-04-2021-0136. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, J.; Sadiq, A.; Noonan, D.S. A Review of the Community Flood Risk Management Literature in the USA: Lessons for Improving Community Resilience to Floods. Natural Hazards 2019, 96, 1223–1248, doi:10.1007/s11069-019-03606-3. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.P.; Biesbroek, R.; Trí, V.P.Đ.; Kummu, M.; Michelle T. H. van Vliet; Leemans, R.; Kabat, P.; Ludwig, F. Managing Flood Risks in the Mekong Delta: How to Address Emerging Challenges Under Climate Change and Socioeconomic Developments. Ambio 2018, 47, 635–649, doi:10.1007/s13280-017-1009-4. [CrossRef]

- Echendu, A.J. Women, Development, and Flooding Disaster Research in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. Environmental and Earth Sciences Research Journal 2021, 8, 147–152, doi:10.18280/eesrj.080401. [CrossRef]

- Ochola, E. Impact of Floods on Kenyan Women: A Critical Review of Media Coverage, Institutional Response and Opportunities for Gender Responsive Mitigation. Ardj 2022, 5, doi:10.61538/ardj.v5i1.1050. [CrossRef]

- Giri, S. Seed Priming: A Strategy to Mitigate Flooding Stress in Pulses. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2024, 14, 42–55, doi:10.9734/ijecc/2024/v14i34018. [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Feng, K.; Lin, N. Predicting Support for Flood Mitigation Based on Flood Insurance Purchase Behavior. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 054014, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab195a. [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Khan, S.I.; Anum, N.; Qadir, Z.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Mahmud, A. Post-Flood Risk Management and Resilience Building Practices: A Case Study. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4823, doi:10.3390/app11114823. [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. Approaches in Research on Flood Risk Perception and Their Importance in Flood Risk Management: A Review. Natural Hazards 2021, 111, 2343–2378, doi:10.1007/s11069-021-05140-7. [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Dou, W.; Lu, X.; Mao, J. Understanding Risk Perception From Floods: A Case Study From China. Natural Hazards 2021, 105, 3119–3140, doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04458-y. [CrossRef]

- Liao, S. Balancing Flood Control and Economic Development in Flood Detention Areas of the Yangtze River Basin. Isprs International Journal of Geo-Information 2024, 13, 122, doi:10.3390/ijgi13040122. [CrossRef]

- Dewa, O.; Makoka, D.; Ayo-Yusuf, O.A. Measuring Community Flood Resilience and Associated Factors in Rural Malawi. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2022, 16, doi:10.1111/jfr3.12874. [CrossRef]

- Gould, J.A.; Kulik, C.T.; Sardeshmukh, S. Trickle-down Effect: The Impact of Female Board Members on Executive Gender Diversity. Human Resource Management 2018, 57, 931–945, doi:10.1002/hrm.21907. [CrossRef]

- Adéchian, S.A.; Baco, M.N.; Tahirou, A. Improving the Adoption of Stress Tolerant Maize Varieties Using Social Ties, Awareness or Incentives: Insights from Northern Benin (West-Africa). World Development Sustainability 2023, 3, 100112.

- Smiley, K.T.; Wehner, M.; Frame, D.; Sampson, C.; Wing, O. Social Inequalities in Climate Change-Attributed Impacts of Hurricane Harvey. Nature Communications 2022, 13, doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31056-2. [CrossRef]

- Yanadori, Y.; Kulik, C.T.; Gould, J.A. Who Pays the Penalty? Implications of Gender Pay Disparities Within Top Management Teams for Firm Performance. Human Resource Management 2021, 60, 681–699, doi:10.1002/hrm.22067. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Indicators Benin | Indicators Togo | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Knowledge-based Practices (EKP) | To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

A five-point Likert scale variable ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. |

| Community Engagement-based Practices (CEP) | To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

A five-point Likert scale variable ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. |

| Agricultural Technology-based Practices (ATP) | To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

To prevent and manage flooding, you rely on the following practices in your household:

|

A five-point Likert scale variable ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. |

| Household resilience (adapted from [6].) |

|

A five-point Likert scale variable ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. | |

| Household characteristics | Modalities | Benin | Togo | Study area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 41 | 26 | 40 | 26 | 81 | 26 |

| Male | 115 | 74 | 116 | 74 | 231 | 74 | |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 156 | 100 | 312 | 100 | |

| Formal education | None | 91 | 58 | 68 | 44 | 159 | 51 |

| Primary | 27 | 17 | 66 | 42 | 93 | 30 | |

| Secondary | 34 | 22 | 18 | 12 | 52 | 17 | |

| University | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 3 | |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 156 | 100 | 312 | 100 | |

| Advisory services | No | 57 | 37 | 91 | 58 | 148 | 47 |

| Yes | 99 | 63 | 65 | 42 | 164 | 53 | |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 156 | 100 | 312 | 100 | |

| Age | Young | 57 | 37 | 57 | 37 | 114 | 37 |

| Adult | 66 | 42 | 70 | 45 | 136 | 44 | |

| Old | 33 | 21 | 29 | 19 | 62 | 20 | |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 156 | 100 | 312 | 100 | |

| Country | Endogenous variables | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | EKP | 3.26 | 1 | 0.92 |

| CEP | 3.33 | 0.94 | 0.88 | |

| ATP | 4.14 | 0.51 | 0.86 | |

| Resilience | 2.93 | 0.58 | 0.89 | |

| Togo | EKP | 2.88 | 1.26 | 0.91 |

| CEP | 2.98 | 1.15 | 0.94 | |

| ATP | 2.96 | 1.21 | 0.89 | |

| Resilience | 2.87 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| Model | CFI | GFI | adj. GFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volta Basin scale (Overall SEM) | 0.915 | 0.999 | 0.993 | 0.048 | 0.08 |

| Multigroup factor analysis | 0.906 | 0.998 | 0.982 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).