Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

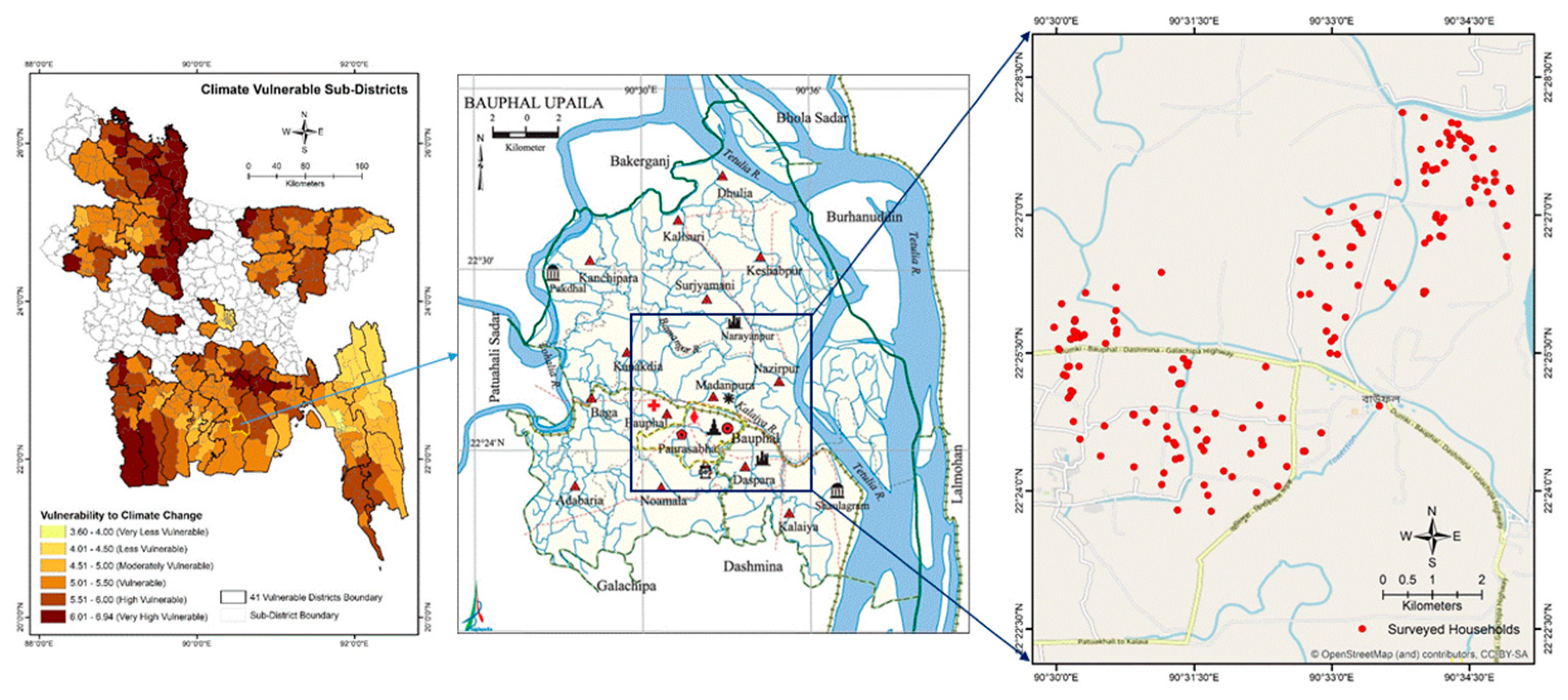

2.1. Study Area

2.2. About the Target Group

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Index Calculation

3. Results and Analysis

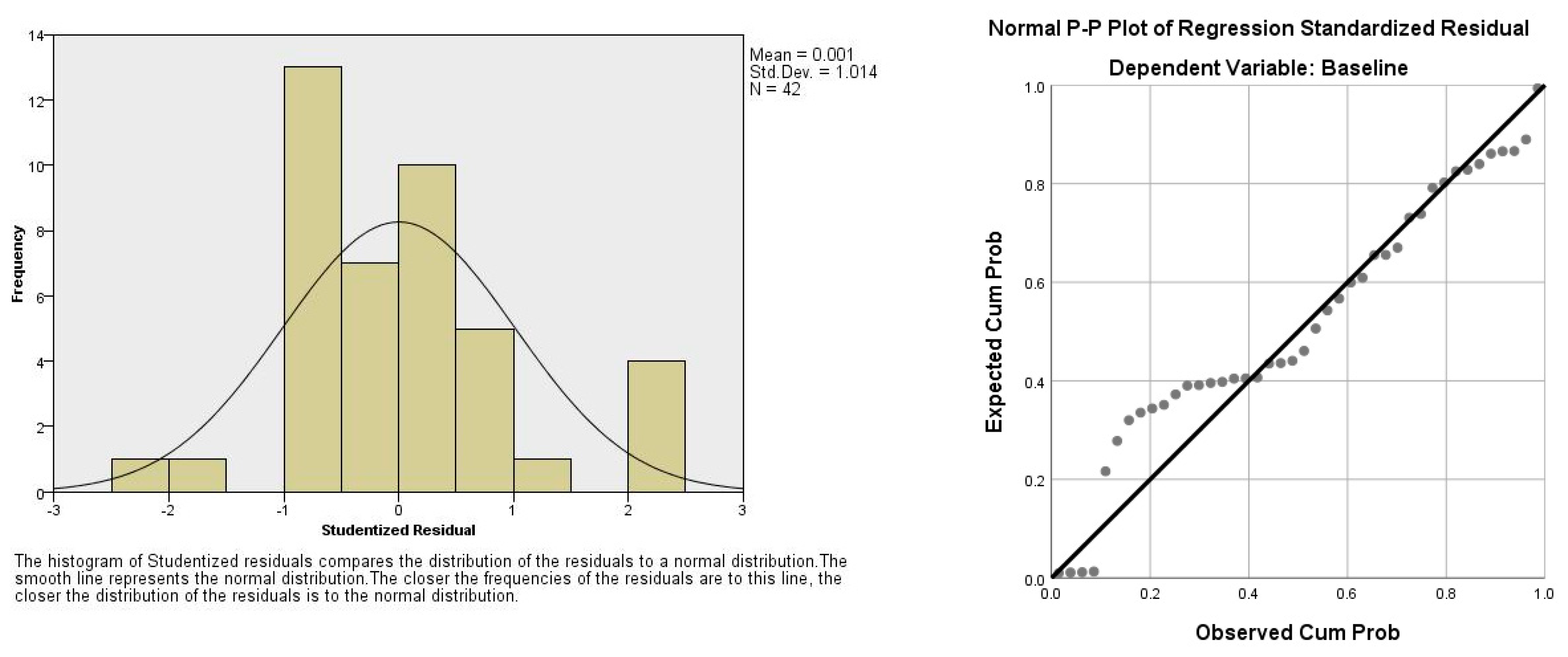

3.1. Histogram Analysis

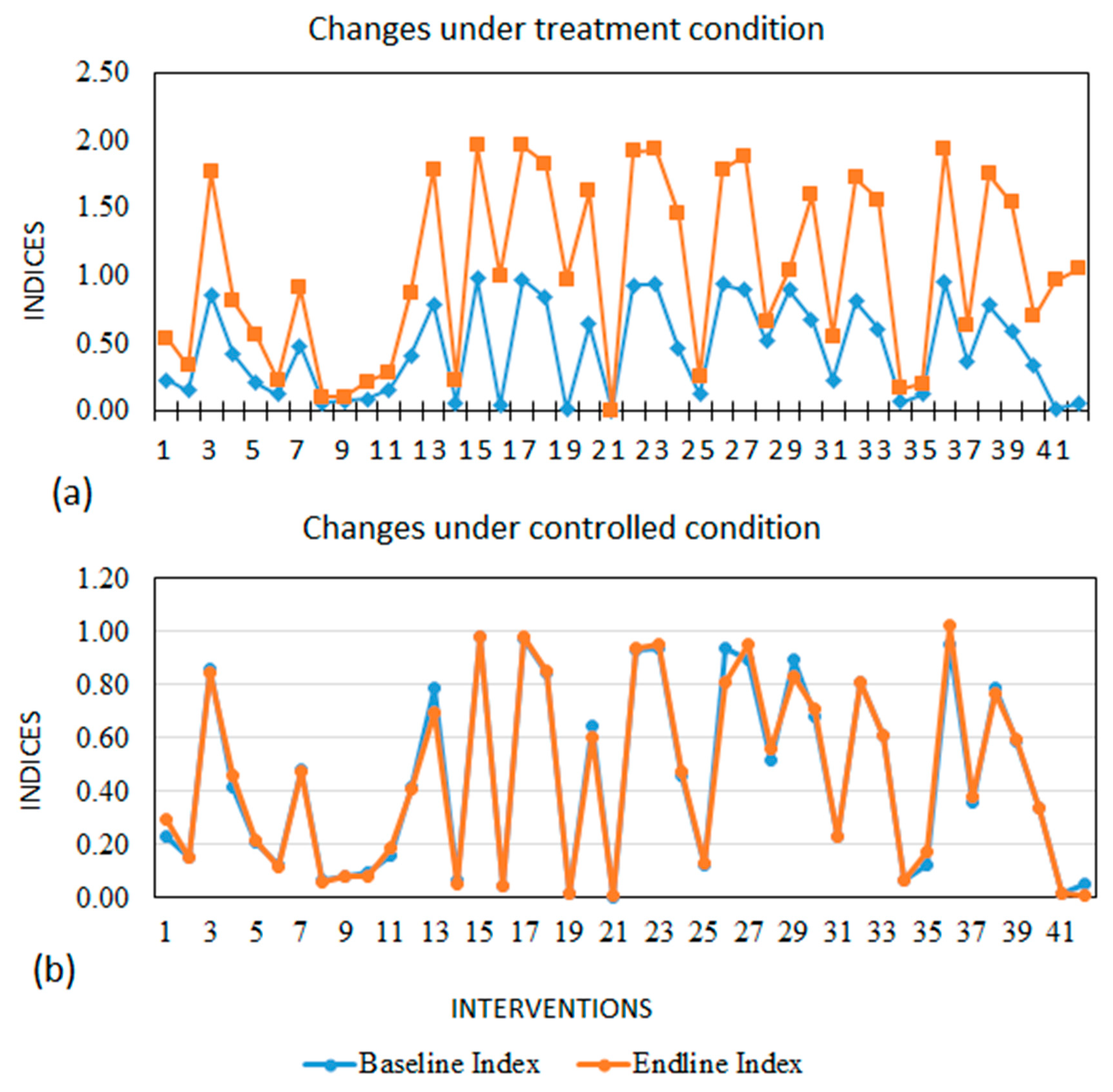

3.2. Analysis of Data Under Treatment Condition

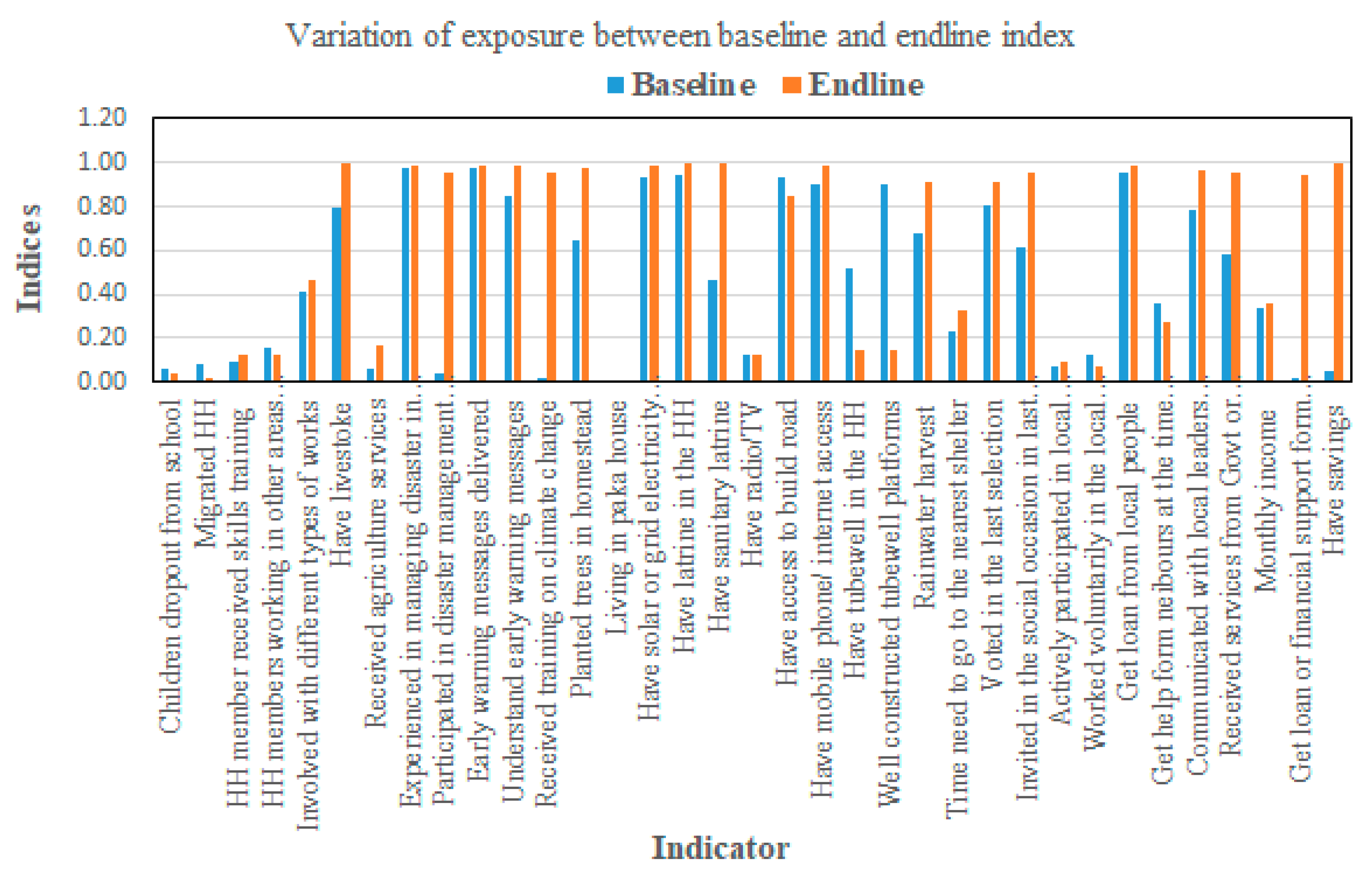

3.2.1. Exposure Assessment

| No | Indicators | Index difference from baseline to endline | Index increment (%) | Categorization of increment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Participated in disaster management events organized by GoB or NGOs | 0.912 | % | |

| 2 | Received training on climate change | 0.941 | 11.91% |

High |

| 3 | Get loan or financial support from bank or society | 0.927 | ||

| 4 | Have savings | 0.941 | ||

| 5 | Have sanitary latrine | 0.532 | ||

| 6 | Have livestock | 0.205 |

11.91% |

Medium |

| 7 | Planted trees in homestead | 0.337 | ||

| 8 | Rainwater harvest | 0.234 | ||

| 9 | Invited in the social occasion in last 1 year | 0.341 | ||

| 10 | Received services from Govt or non-govt organizations | 0.371 | ||

| 11 | Number of HH members | 0.136 |

11.91% |

Considerable |

| 12 | Received agriculture services | 0.107 | ||

| 13 | Understand early warning messages | 0.141 | ||

| 14 | Voted in the last selection | 0.102 | ||

| 15 | Communicated with local leaders for getting help | 0.180 | ||

| 16 | Dependent member (<15 years) | 0.070 |

0.33% |

Low |

| 17 | Dependent member (>65 years) | 0.027 | ||

| 18 | Husband is the household head | 0.039 | ||

| 19 | Involved with different types of works | 0.046 | ||

| 20 | Experienced in managing disaster in last 30 years | 0.005 | ||

| 21 | Early warning messages delivered | 0.015 | ||

| 22 | Living in paca house | - | ||

| 23 | Have solar or grid electricity connection | 0.054 | ||

| 24 | Have latrine in the HH | 0.054 | ||

| 25 | Have mobile phone/ internet access | 0.088 | ||

| 26 | Time needs to go to the nearest shelter | 0.091 | ||

| 27 | Actively participated in local meetings in last 1 year | 0.029 | ||

| 28 | Get loan from local people | 0.039 | ||

| 29 | Monthly income | 0.028 | ||

| 30 | Education of HH head | 0.023 |

26.19% |

Negative indicator |

| 31 | HH members involved in income | 0.016 | ||

| 32 | Highest educated HH member | 0.048 | ||

| 33 | Children dropout from school | 0.024 | ||

| 34 | Migrated HH | 0.054 | ||

| 35 | HH members working in other areas for livelihood | 0.033 | ||

| 36 | Have radio/TV | 0.005 | ||

| 37 | Have access to build road | 0.088 | ||

| 38 | Have tubewell in the HH | 0.371 | ||

| 39 | Well-constructed tubewell platforms | 0.751 | ||

| 40 | Worked voluntarily in the local development initiatives | 0.054 | ||

| 41 | Get help form neighbors at the time of disaster | 0.083 |

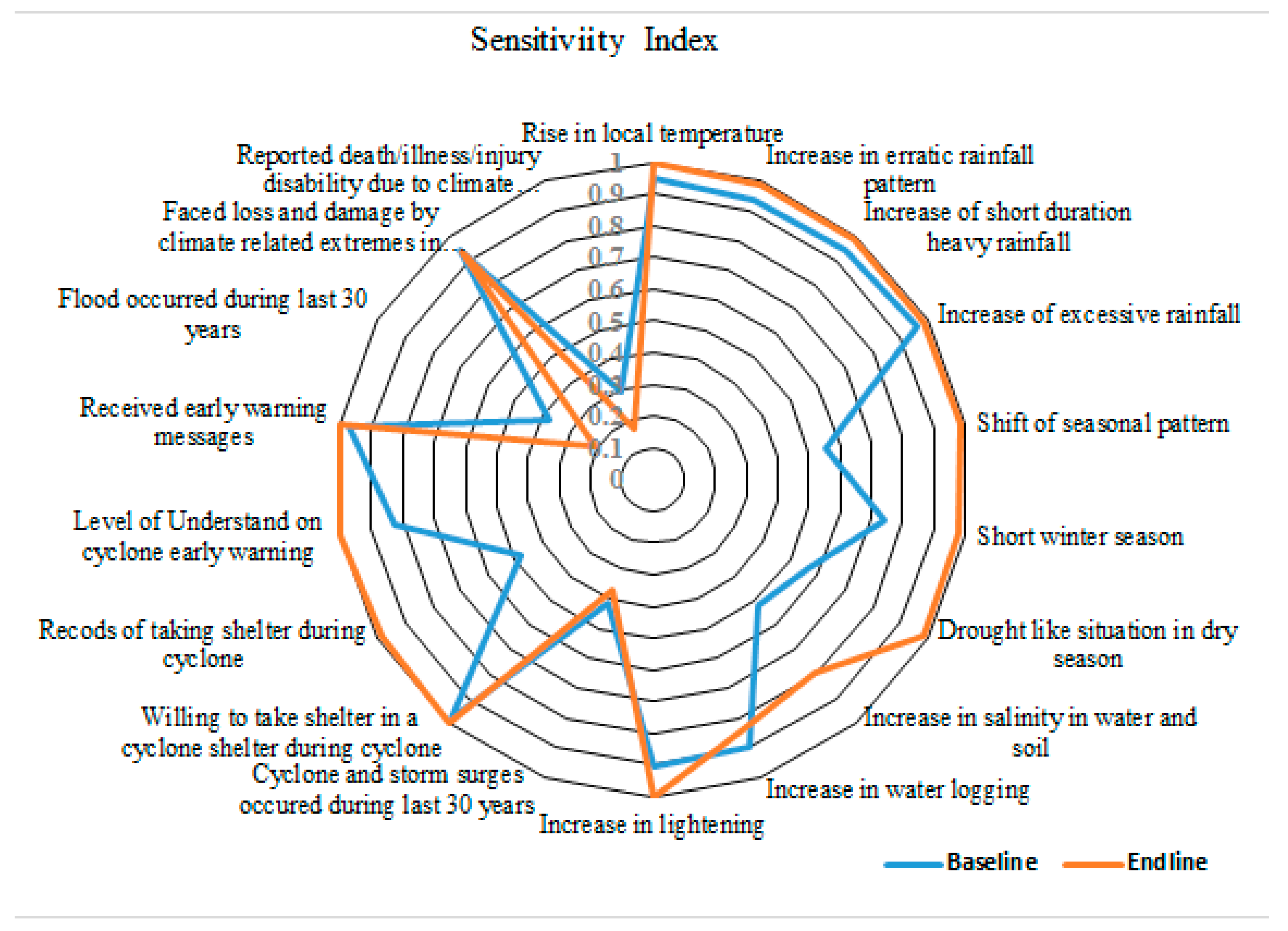

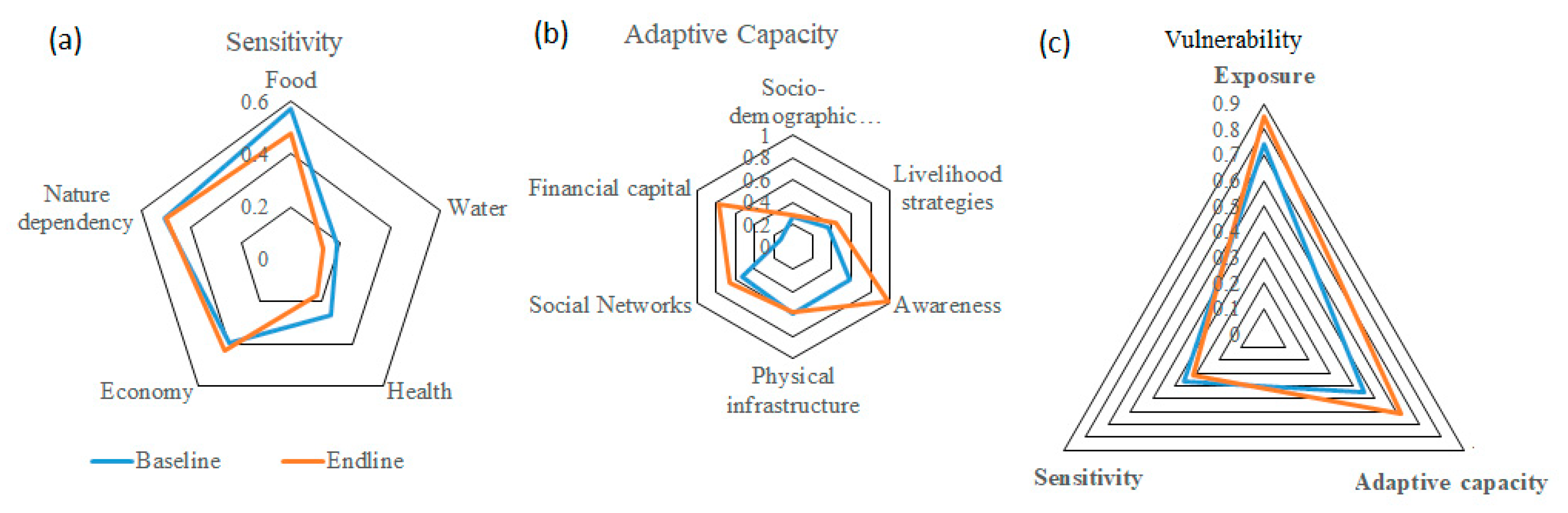

3.2.2. Sensitivity Assessment

3.2.2.1. Climate Change Intensity

3.2.2.3. Health Condition

3.2.2.4. Economic Condition

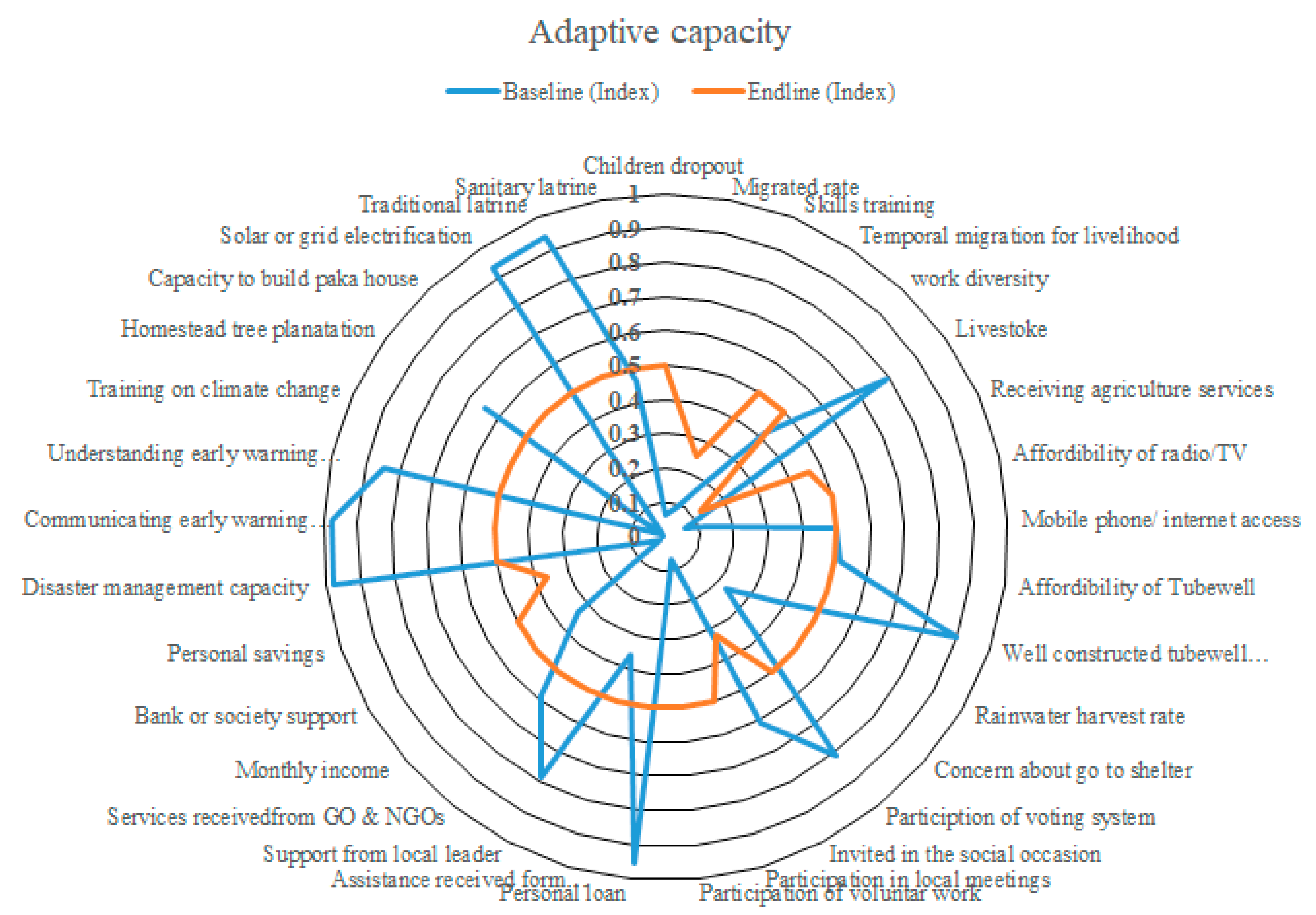

3.2.3. Adaptive Capacity Assessment

3.2.3.1. Sociodemographic Profile

3.2.3.2. Livelihood Strategies Development

3.2.3.3. Awareness Development

3.2.3.4. Physical Infrastructure Growth

3.2.3.5. Social Networks Development

3.2.3.6. Financial Capital Development

3.3. Results Under Controlled Environment

3.3.1. Socio -Demographic Profile

| ID | Components | Indicator | Baseline Index | Endline Index | Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dependent member (<15 years) | 0.233 | 0.294 | 26.18 | |

| 2 | Dependent member (>65 years) | 0.154 | 0.151 | -1.95 | |

| 3 | Husband is the household head | 0.863 | 0.844 | -2.20 | |

| 4 | Socio -Demographic Profile | Education of HH head | 0.419 | 0.458 | 9.31 |

| 5 | Number of HH members | 0.212 | 0.215 | 1.42 | |

| 6 | HH members involved in income | 0.123 | 0.116 | -5.69 | |

| 7 | Highest educated HH member | 0.480 | 0.471 | -1.88 | |

| 8 | Children dropout from school | 0.063 | 0.059 | -6.35 | |

| 9 | Migrated HH | 0.078 | 0.084 | 7.69 | |

| 10 | HH member received skills training | 0.093 | 0.082 | -11.83 | |

| 11 | HH members working in other areas for livelihood | 0.160 | 0.187 | 16.88 | |

| 12 | Livelihood strategies | Involved with different types of works | 0.415 | 0.408 | -1.71 |

| 13 | Have livestock | 0.790 | 0.695 | -13.66 | |

| 14 | Received agriculture services | 0.063 | 0.051 | -23.52 | |

| 15 | Experienced in managing disaster in last 30 years | 0.980 | 0.984 | ||

| 16 | Participated in disaster management events | 0.044 | 0.046 | 4.54 | |

| 17 | Awareness | Early warning messages delivered | 0.976 | 0.980 | 1.03 |

| 18 | Understand early warning messages | 0.844 | 0.854 | 1.18 | |

| 19 | Received training on climate change | 0.015 | 0.016 | 6.66 | |

| 20 | Planted trees in homestead | 0.644 | 0.605 | -6.44 | |

| 21 | Living in Paka house | 0.005 | 0.006 | 20.00 | |

| 22 | Have solar or grid electricity connection | 0.932 | 0.937 | 0.54 | |

| 23 | Have latrine in the HH | 0.941 | 0.951 | 1.06 | |

| 24 | Physical infrastructure | Have sanitary latrine | 0.463 | 0.472 | 1.94 |

| 25 | Have radio/TV | 0.127 | 0.132 | -3.94 | |

| 26 | Have access to build road | 0.937 | 0.809 | -13.66 | |

| 27 | Have mobile phone/ internet access | 0.898 | 0.954 | 6.24 | |

| 28 | Have tubewell in the HH | 0.517 | 0.563 | 8.90 | |

| 29 | Well-constructed tubewell platforms | 0.898 | 0.83 | -8.19 | |

| 30 | Rainwater harvest | 0.683 | 0.707 | 3.51 | |

| 31 | Time needs to go to the nearest shelter | 0.233 | 0.232 | -0.43 | |

| 32 | Voted in the last selection | 0.810 | 0.812 | 0.25 | |

| 33 | Invited in the social occasion in last 1 year | 0.610 | 0.612 | 0.33 | |

| 34 | Actively participated in local meetings in last 1 year | 0.068 | 0.067 | -1.47 | |

| 35 | Worked voluntarily in the local development initiatives | 0.127 | 0.173 | 36.22 | |

| 36 | Social Networks | Get loan from local people | 0.951 | 1.024 | 7.68 |

| 37 | Get help form neighbors at the time of disaster | 0.361 | 0.378 | 4.71 | |

| 38 | Communicated with local leaders for getting help | 0.785 | 0.766 | -2.42 | |

| 39 | Received services from Govt or non-govt organizations | 0.585 | 0.598 | 2.22 | |

| 40 | Monthly income | 0.336 | 0.341 | 1.49 | |

| 41 | Financial capital | Get loan or financial support from bank or society | 0.020 | 0.015 | -25.00 |

| 42 | Have savings | 0.054 | 0.012 | -77.78 |

3.3.2. Livelihood Strategies Development

3.3.3. Awareness Development

3.3.4. Physical Infrastructures Growth

3.3.5. Social Networks Development

3.3.6. Financial Capital Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- M. S. Ul Din et al., “World nations priorities on climate change and food security,” in Building Climate Resilience in Agriculture: Theory, Practice and Future Perspective, 2021, pp. 265–284. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Adger, S. Huq, K. Brown, C. Declan, and H. Mike, “Adaptation to climate change in the developing world,” Prog. Dev. Stud., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 179–195, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. A. A. Hoque, B. Pradhan, N. Ahmed, B. Ahmed, and A. M. Alamri, “Cyclone vulnerability assessment of the western coast of Bangladesh,” Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 198–221, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Dasgupta, M. S. Islam, M. Huq, and H. Khan, “Z., & Hasib, M,” R. Quantifying Prot. Capacit. mangroves from storm surges Coast, vol. 14, 2019, [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- M. A. H. Bhuiyan, S. M. D.-U. Islam, and G. Azam, “Exploring impacts and livelihood vulnerability of riverbank erosion hazard among rural household along the river Padma of Bangladesh,” Environ. Syst. Res., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 1, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rakib, “Export Trend of the Leather Industry of Bangladesh: Challenges to Sustainable Development A R TI C LE I N F O Article History,” BUFT J. Bus. Econ. (BJBE, vol. 1, pp. 163–187, 2020.

- UNDP, “Cyclone Aila: Joint Multi-Sector Assessment and Response Framework. Retrieved,” Bur. Cris. Prev., 2010.

- K. M. Tasnim, T. Shibayama, M. Esteban, H. Takagi, K. Ohira, and R. Nakamura, “Field observation and numerical simulation of past and future storm surges in the Bay of Bengal: case study of cyclone Nargis,” Nat. Hazards, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 1619–1647, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ahamed, “Community based Approach for Reducing Vulnerability to Natural Hazards (Cyclone, Storm Surges) in Coastal Belt of Bangladesh,” Procedia Environ. Sci., vol. 17, pp. 361–371, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rakib et al., “Groundwater salinization and associated co-contamination risk increase severe drinking water vulnerabilities in the southwestern coast of Bangladesh,” Chemosphere, vol. 246, no. 125646, p. 125646, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Ur Rahman, M. Rasheduzzaman, M. A. Habib, A. Ahmed, S. M. Tareq, and S. M. Muniruzzaman, “Community Mitigation Approaches to Combat Safe Water Scarcity in the Context of Salinity Intrusion in Coastal Bangladesh,” in Springer Water, Cham: Springer, 2021, pp. 787–797. [CrossRef]

- M. R. R. Talukder, S. Rutherford, D. Phung, M. Z. Islam, and C. Chu, “The effect of drinking water salinity on blood pressure in young adults of coastal Bangladesh,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 214, pp. 248–254, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Das et al., “Social vulnerability to environmental hazards in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta, India and Bangladesh,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 53, no. 101983, p. 101983, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Ahsan, F. Khatun, P. Kumar, R. Dasgupta, B. A. Johnson, and R. Shaw, “Promise, premise, and reality: the case of voluntary environmental non-migration despite climate risks in coastal Bangladesh,” Reg. Environ. Chang., vol. 22, no. 1, p. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Bank, Inclusive Resilience: Inclusion Matters for Resilience in South Asia. World Bank, 2021.

- K. F. Austin and L. A. McKinney, “Disaster devastation in poor nations: The direct and indirect effects of gender equality, ecological losses, and development,” Soc. Forces, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 355–380, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Oktari, S. Kamaruzzaman, F. Fatimahsyam, S. Sofia, and D. K. Sari, “Gender mainstreaming in a Disaster-Resilient Village Programme in Aceh Province, Indonesia: Towards disaster preparedness enhancement via an equal opportunity policy,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 52, no. 101974, p. 101974, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Walters and J. C. Gaillard, “Disaster risk at the margins: Homelessness, vulnerability and hazards,” Habitat Int., vol. 44, pp. 211–219, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Ahsan and J. Warner, “The socioeconomic vulnerability index: A pragmatic approach for assessing climate change led risks-A case study in the south-western coastal Bangladesh,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 8, pp. 32–49, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Islam, M. S. Hossain, and M. A. B. Siddique, “Occupational health hazards and safety practices among the workers of tannery industry in Bangladesh,” Jahangirnagar Univ. J. Biol. Sci., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 13–22, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. W. Rabby, M. B. Hossain, and M. U. Hasan, “Social vulnerability in the coastal region of Bangladesh: An investigation of social vulnerability index and scalar change effects,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 41, no. 101329, p. 101329, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Saisana and S. Tarantola, State-of-the-art Report on Current Methodologies and Practices for Composite Indicator Development, vol. 214, no. July. European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for the Protection and~…, 2002.

- Kotzee and, B. Reyers, “Piloting a social-ecological index for measuring flood resilience: A composite index approach,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 60, pp. 45–53, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Valipour, “Future of agricultural water management in Africa,” Arch. Agron. Soil Sci., vol. 61, no. 7, pp. 907–927, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Valipour et al., “Agricultural water management in the world during past half century,” Arch. Agron. Soil Sci., vol. 61, no. 5, pp. 657–678, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Hinkel, “‘ Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity’: Towards a clarification of the science-policy interface,” Glob. Environ. Chang., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 198–208, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Scholes and R. Biggs, “A biodiversity intactness index,” Nature, vol. 434, no. 7029, pp. 45–49, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. X. Kasperson and R. E. Kasperson, “International Workshop on Vulnerability and Global Environmental Change,” Int. Hum. Dimens. Progr. Updat., vol. 01, no. 2001--01, pp. 2–3, 2001.

- H. M. Füssel and R. J. T. Klein, “Climate change vulnerability assessments: An evolution of conceptual thinking,” Clim. Change, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 301–329, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Izrael et al., The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Working Group II contribution, vol. 32, no. 9. Cambridge University Press, 2007. [CrossRef]

- The Core Writing Team IPCC, Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Ipcc, 2015.

- B. Smit and J. Wandel, “Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability,” Glob. Environ. Chang., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 282–292, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- N. Arnell, “Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,” IPCC, pp. 191–234, 2001.

- N. R. Das, “Human Development Report 2007/2008 Fighting Climate Change: Human Solidarity in a Divided World, UNDP, New York,” Soc. Change, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 154–159, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Shahzad et al., “Livelihood vulnerability index: a pragmatic assessment of climatic changes in flood affected community of Jhok Reserve Forest, Punjab, Pakistan,” Environ. Earth Sci., vol. 80, no. 7, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Suryanto and A. Rahman, “Application of livelihood vulnerability index to assess risks for farmers in the Sukoharjo regency and Klaten regency, Indonesia,” Jamba J. Disaster Risk Stud., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 739, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Hahn, A. M. Riederer, and S. O. Foster, “The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—A case study in Mozambique,” Glob. Environ. Chang., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 74–88, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Cook, “Detection of Influential Observation in Linear Regression,” Technometrics, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 15–18, 1977. [CrossRef]

- K. A. BOLLEN and R. W. JACKMAN, “Regression Diagnostics: An Expository Treatment of Outliers and Influential Cases,” Sociol. Methods \& Res., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 510–542, 1985. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rakib, J. Sasaki, H. Matsuda, and M. Fukunaga, “Severe salinity contamination in drinking water and associated human health hazards increase migration risk in the southwestern coastal part of Bangladesh,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 240, pp. 238–248, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen and V. Mueller, “Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh,” Nat. Clim. Chang., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 981–985, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khan and A. J. Ali, “The role of training in reducing poverty: The case of the ultra-poor in Bangladesh,” Int. J. Train. Dev., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 271–281, 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, S. Roy, B. K. Behera, P. Bossier, and B. K. Das, “Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (Ahpnd): Virulence, pathogenesis and mitigation strategies in Shrimp aquaculture,” Toxins (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 8, p. 524, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Uddin, C. E. Haque, M. N. Khan, B. Doberstein, and R. S. Cox, “‘Disasters threaten livelihoods, and people cope, adapt and make transformational changes’: Community resilience and livelihoods reconstruction in coastal communities of Bangladesh,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 63, p. 10244, 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. S. Thathsarani and L. H. P. Gunaratne, “Constructing and Index to Measure the Adaptive Capacity to Climate Change in Sri Lanka,” Procedia Eng., vol. 212, pp. 278–285, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Baffour-Ata et al., “Assessing the adaptive capacity of smallholder cocoa farmers to climate variability in the Adansi South District of the Ashanti Region, Ghana,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 3, p. e13994, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Salam et al., “Nexus between vulnerability and adaptive capacity of drought-prone rural households in northern Bangladesh,” Nat. Hazards, vol. 106, no. 1, pp. 509–527, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Willems and K. A. Baumert, “Institutional capacity and climate actions,” OECD/IEA Clim. Chang. Expert Gr. Pap., 2003, [Online]. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:126897434.

- B. Shahbaz, “Risk, Vulnerability and Sustainable Livelihoods: Insights from Northwest Pakistan,” 2008. [Online]. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130404515.

- C. M. Hall, “Rethinking Collaboration and Partnership: A Public Policy Perspective,” J. Sustain. Tour., vol. 7, no. 3–4, pp. 274–289, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Fothergill, “An Exploratory Study of Woman Battering in the Grand Forks Flood Disaster: Implications for Community Responses and Policies,” Int. J. Mass Emergencies \& Disasters, vol. 17, pp. 79–98, 1999, [Online]. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:112431609.

- J. D. Morrow, “How Could Trade Affect Conflict?,” J. Peace Res., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 481–489, 1999. [CrossRef]

| No | Name of intervention | No | Name of intervention |

| 1 | Livestock support | 7 | Health care support |

| 2 | Agriculture input | 8 | Microfinancing |

| 3 | Seed capital | 9 | Drinking water (Rainwater harvesting) support |

| 4 | Partial food support/Food bank | 10 | Energy (Solar) system support |

| 5 | Help to create Saving account | 11 | Support of homestead gardening |

| 6 | Training/weekly coaching | 12 | Awareness camping |

| Components | Indicator (make correction in the text) | Baseline Index | Endline Index | Difference (Endline-Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio -Demographic Profile |

Dependent member (<15 years) | 0.233 | 0.303 | 0.070 |

| Dependent member (>65 years) | 0.154 | 0.181 | 0.027 | |

| Husband is the household head | 0.863 | 0.902 | 0.039 | |

| Education of HH head | 0.419 | 0.396 | -0.023 | |

| Number of HH members | 0.212 | 0.348 | 0.136 | |

| HH members involved in income | 0.123 | 0.106 | -0.016 | |

| Highest educated HH member | 0.480 | 0.433 | -0.048 | |

| Children dropout from school | 0.063 | 0.039 | -0.024 | |

| Migrated HH | 0.078 | 0.024 | -0.054 | |

| HH member received skills training | 0.093 | 0.122 | 0.029 | |

| Livelihood strategies |

HH members working in other areas for livelihood | 0.160 | 0.127 | -0.033 |

| Involved with different types of works | 0.415 | 0.461 | 0.046 | |

| Have livestock | 0.790 | 0.995 | 0.205 | |

| Received agriculture services | 0.063 | 0.171 | 0.107 | |

| Awareness |

Experienced in managing disaster in last 30 years | 0.980 | 0.985 | 0.005 |

| Participated in disaster management events organized by GoB or NGOs | 0.044 | 0.956 | 0.912 | |

| Early warning messages delivered | 0.976 | 0.990 | 0.015 | |

| Understand early warning messages | 0.844 | 0.985 | 0.141 | |

| Received training on climate change | 0.015 | 0.956 | 0.941 | |

| Planted trees in homestead | 0.644 | 0.980 | 0.337 | |

| Physical infrastructure |

Living in Paka house | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| Have solar or grid electricity connection | 0.932 | 0.985 | 0.054 | |

| Have latrine in the HH | 0.941 | 0.995 | 0.054 | |

| Have sanitary latrine | 0.463 | 0.995 | 0.532 | |

| Have radio/TV | 0.127 | 0.122 | -0.005 | |

| Have access to build road | 0.937 | 0.849 | -0.088 | |

| Have mobile phone/ internet access | 0.898 | 0.985 | 0.088 | |

| Have tubewell in the HH | 0.517 | 0.146 | -0.371 | |

| Well-constructed tubewell platforms | 0.898 | 0.146 | -0.751 | |

| Rainwater harvest | 0.683 | 0.917 | 0.234 | |

| Time needs to go to the nearest shelter | 0.233 | 0.323 | 0.091 | |

| Social Networks |

Voted in the last selection | 0.810 | 0.912 | 0.102 |

| Invited in the social occasion in last 1 year | 0.610 | 0.951 | 0.341 | |

| Actively participated in local meetings in last 1 year | 0.068 | 0.098 | 0.029 | |

| Worked voluntarily in the local development initiatives | 0.127 | 0.073 | -0.054 | |

| Get loan from local people | 0.951 | 0.990 | 0.039 | |

| Get help form neighbors at the time of disaster | 0.361 | 0.278 | -0.083 | |

| Communicated with local leaders for getting help | 0.785 | 0.966 | 0.180 | |

| Received services from Govt or non-govt organizations | 0.585 | 0.956 | 0.371 | |

| Financial capital |

Monthly income | 0.336 | 0.364 | 0.028 |

| Get loan or financial support from bank or society | 0.020 | 0.946 | 0.927 | |

| Have savings | 0.054 | 0.995 | 0.941 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).