1. Introduction

The world construction sector is undergoing the most unprecedented challenges triggered by the rising demand for sustainable, durable and resilient infrastructure. Conventional Portland cement systems are another key factor that leads to degradation of the environment despite their wide usage, with an estimated contribution of about 7–8% of the total anthropogenic CO 2 emission in the atmosphere [

1,

2]. The manufacturing of Portland cement is very energy consuming since it releases about 0.81 kg of CO 2 per kilogram of cement with certain analyses comparing the manufacture of one ton of cement to the release of one ton of CO 2 [

3,

4]. The fact that the carbon footprint is very huge and the fact that non-renewable products like limestone and natural sand continue to be depleted is evidence of why more sustainable cementitious products should be developed [

2].

As a measure to reduce these effects, numerous studies have investigated alternative binder systems that have minimized carbon footprints. Among them, eco-sustainable cementitious systems, alkali-activated materials (AAMs), have become the materials that can use various industrial by-products like fly ash and slag [

5,

6]. It is recorded that AAMs cut down CO 2 emissions by about 50-80% in comparison with the normal Portland cement concrete [

2]. These materials also have greater engineering performance compared to traditional ones, such as high levels of mechanical strength, acid resistance, sulfate resistance, and performance at high temperatures, in addition to having positive environmental characteristics. In most instances, it has also been re-ported to have better chloride resistance and abrasion life in comparison to the normal Portland cement (OPC) systems [

2,

7,

8]. However, AAMs continue to experience issues to do with quick setting, drying contraction, endurance of doubt in particular formulae, environmental issues concerning activated alkali, and absence of universally recognized design standards [

2].

Fly ash, a by-product of coal burning, is still one of the most widely researched precursors of alkali-activated binders as it has an aluminosilicate composition and can be geopolymerized [

9]. The reactivity of it is highly dependent on the chemical composition, especially the level of calcium content, distinguishing between high-calcium fly ash (HCFA) and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA). Because of the existence of calcium-bearing phases, HCFA tends to have an increased early reactivity and enhances faster strength growth [

10,

11]. Conversely, LCFA is slower in response, but can offer a better performance stability in the alkaline activation case [

5,

12]. The significance of optimizing binder synergy between slag, activators, and various types of fly ash is shown by these compositional differences to provide balanced and efficient performance.

In addition to its being used as a binder precursor, fly ash may also be used as a fine-aggregate replacement that has other sustainability advantages of eliminating the need to use natural sand resources whose extraction has important environmental implications. Fine-aggregate replacement influences particle packing density, rheological behavior and early age reaction kinetics. Spherical morphology of fly ash particles can also confer a ball-bearing effect, so that they improve flowability and decrease water requirement [

13,

14,

15]. This effect, however, interacts with the enhanced surface area of smaller particles which could inhibit flowability at higher replacement levels [

16]. Previous studies have demonstrated that moderate replacement level can be beneficial in general performance, but excessive substitution can have negative consequences on workability and mechanical response [

17,

18,

19]. Nevertheless, there are few systematic comparisons of HCFA and LCFA on different replacement levels in controlled conditions of activation.

Fresh-state performance is a key factor in practice which controls casting, pumpability, casting finishing and early-age cracking resistance. Although qualitative methods of assessing workability, which are usually based on the qualitative measurement of slump, have been widely used, quantitative indices like the Initial Flow Index and Flow Retention Index give a more credible and reproducible account of the rheological behavior. Improved flowability and workability retention in alkali-activated systems are especially evaluated by such indices; nevertheless, their use to replace fly ash with fi-ne-aggregates is not a sufficiently examined area.

Compressive strength of alkali-activated composites has mostly been used as a measure of mechanical performance with a Strength Activity Index (SAI) that has been defined in ASTM C618 [

20]. Compressive strength is one of the key performance parameters, but it does not reflect tensile- and flexural-related performance, which is of paramount importance to the cracking resistance and load redistribution in cementitious composites. As a result, there is an increased desire to have composite performance-based frameworks that go beyond compressive strength to include several mechanical indices that have the capability to characterize the complete structural response.

Therefore, the objectives of the present study include researching the synergistic nature of the blending of slag-based binders and fly ash reactivity by using HCFA and LCFA as the alternative fine-aggregated material within the proportions of FA/S ratio (0, 10, 20, and 30%) in replacing the mixture parameters of water-to-slag ratio (W/SL = 50%), and the activator-to-slag ratio (AL/SL = 20%). The quantitative parameters of fresh-state performance include the initial flow Index (IFI) and the flow retention Index (FRI), whilst the quantitative parameters of mechanical performance are Strength Activity Index (SAI), established in ASTM C618 [

20] which is the analogous parameters in tensile and flexural, i.e., Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI), pro-posed in this study as the counterparts of SAI. It is a multi-index performance-based framework that offers a holistic foundation of explaining binder synergy and fly ash reactivity and aid in the optimization of eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC) in alkali-activated systems.

2. Materials and Methods

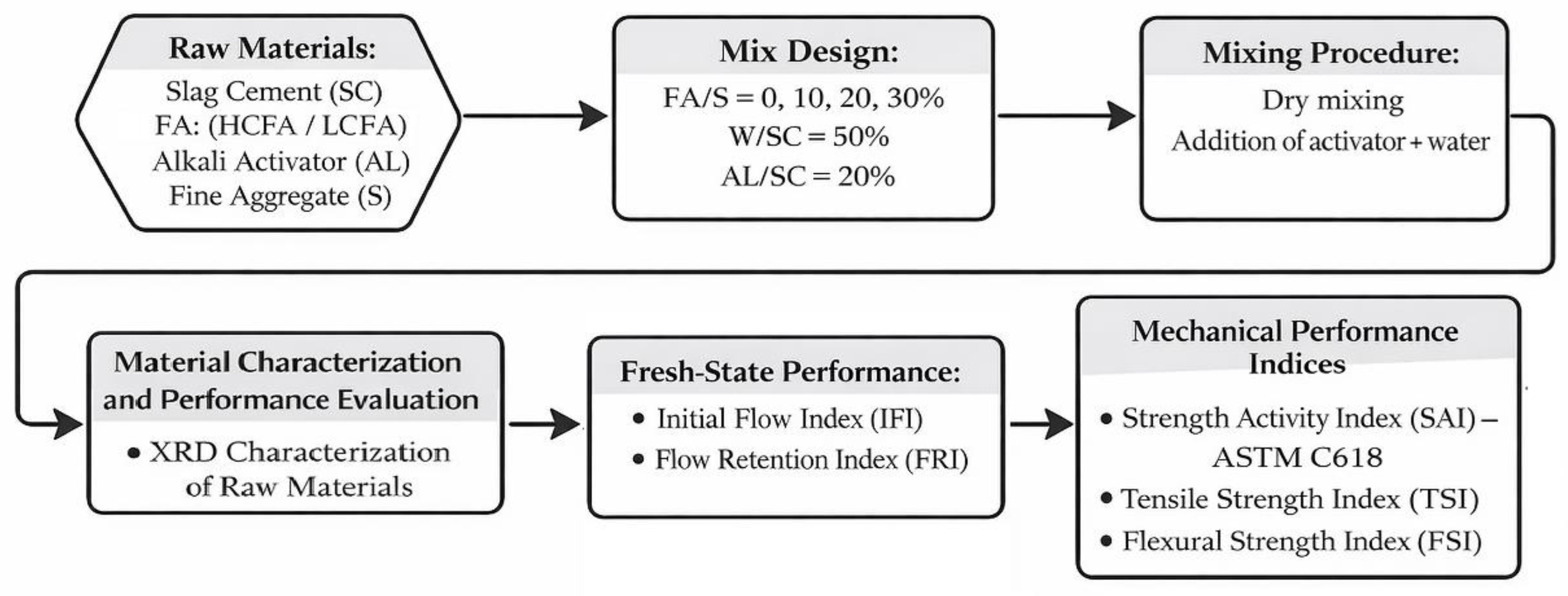

Figure 1 shows a schematic description of the experimental framework used in the current study showing the sequence of raw material selection, mix design, and testing methodology used to test the binder synergy and fly ash reactivity in eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC). The structure melds mineralogical description of raw materials by X-ray dispersion (XRD), quantitative measurement of fresh-state performance by the Initial Flow Index (IFI) and Flow Retention Index (FRI), and mechanical performance measurement based on the Strength Activity Index (SAI), as defined in ASTM C618 [

20], and also complemented by tensile- and flexural-based indices, i.e. the Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and the Flexural Strength Index (FSI).

2.1. Materials

Slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) were used as the main constituents of this study. Their simultaneous application allowed the systematic analysis of the synergetic effect of slag binders, alkali-activated, and fly ash activeness on the formation of eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC). SC is a by-product of municipal waste, and it contains high proportions of amorphous materials. It was selected as a green option since it can minimize the environmental impact that is usually associated with the production of Portland cement. The sources of the HCFA and LCFA were coal power plants, which utilize a wide variety of fuels. HCFA is rich in CaO, and LCFA is rich in amorphous silica and alumina. The variation in the oxide structure, fineness, and content of the glassy phase is directly related to the reactivity and expected contribution to the alkali-activation process. The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was observed to determine the chemical composition of SC, HCFA, and LCFA, and the loss on ignition (LOI) was obtained by burning the samples at 950 °C in a muffle furnace. The air-permeability method of the Blaine method was also used to determine the specific surface area of the powders, and the particle size distributions were also attained using the laser diffraction method. The chemical compositions of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) are presented in

Table 1, and the physical properties of these substances are presented in

Table 2.

2.2. Mix Proportions

Table 3 shows the mix proportions that were investigated in the eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC). All of the composite mixtures of the ESCC were pre-prepared in a curing room at 20 ± 1 °C, and 65 ± 5% RH. Parameters which were examined were slag cement (SC) with constant quantity as core binder. Part of the addition of HCFA and LCFA was to replace the fine aggregates in fly ash with ratios of FA/S of 0,10,20 and 30

%. The mixtures were all fine aggregate (crushed sandstone) having specific gravity (2.58) and fineness modulus (2.83). Na

2SiO

3 (SiO

2/ Na

2O = 1.0) (50% SiO

2 and 50% Na

2O) was selected due to its balanced mass ratio. The mixtures were kept at the same level of activation and rheological properties of the mixture were kept at the level of activator-to-slag ratio (AL/SL) kept at 20% and water-to-slag ratio W/SL was kept at 50%.

2.3. Test Methods and Procedures

To evaluate the multi-index structure of fresh-state and mechanical properties of the eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC), an experimental program was constructed. This experimental procedure is a combination of mineralogical description of the raw materials, quantitative fresh-state indices, and mechanical indices on the basis of strengths to investigate the binder synergy and fly ash reactivity of the controlled laboratory procedures.

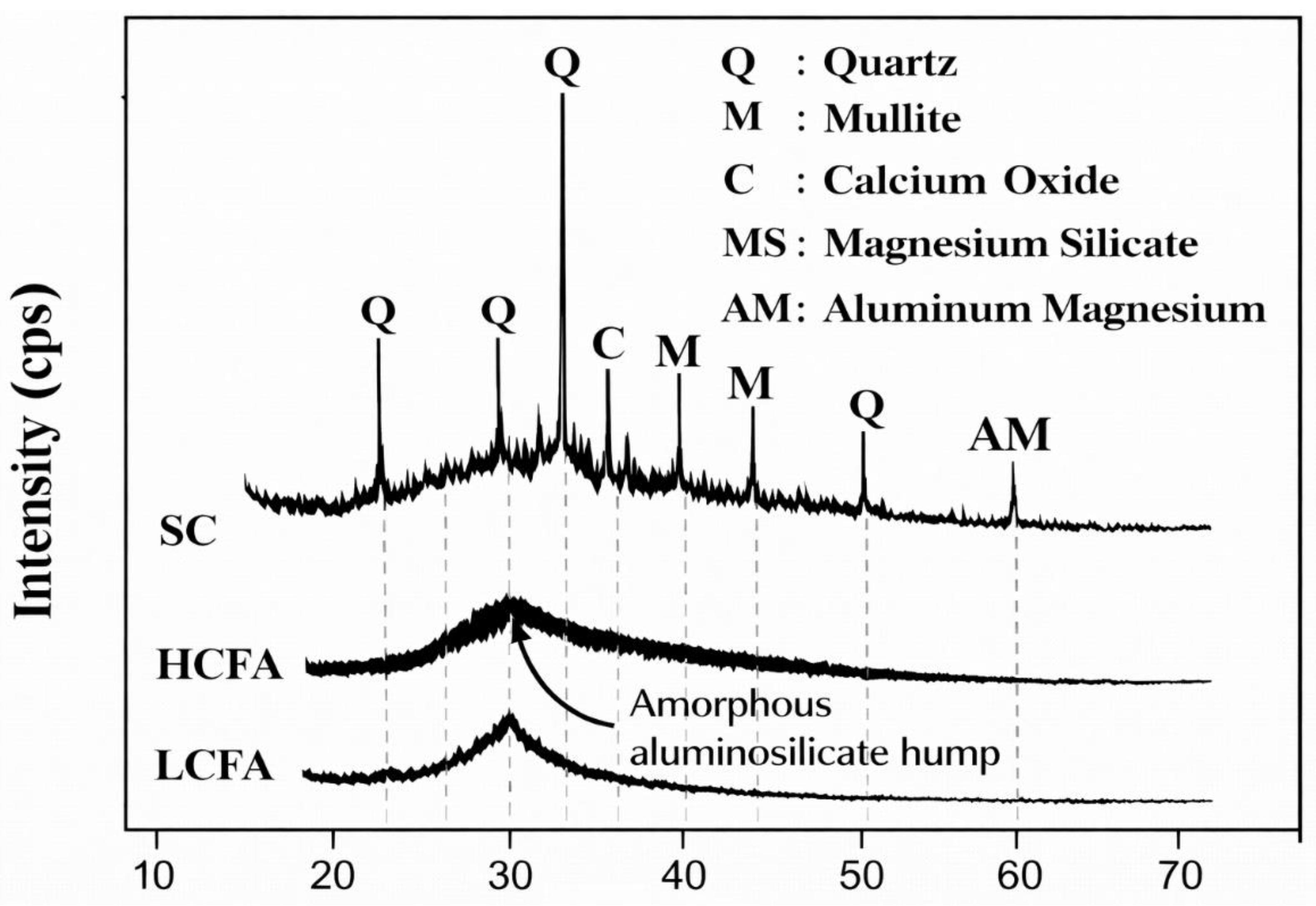

2.3.1. Mineralogical Characterization of Raw Materials

The mineralogical characterization of raw materials was examined to find the fundamental basis that can be used in controlling their reactivity and interaction in the eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC) system. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze the slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) to determine the crystalline composition and the amorphous composition. An analysis of the differentiation of calcium-rich and aluminosilicate stages between alkali activation and binder synergy was studied. The following mineralogical description provides the crucial definition of the variation in fly ash reactivity and interprets fresh-state and mechanical performance.

2.3.2. Fresh-State Performance Tests

Quantifying workability and flow retention behavior in fresh-state was done based on flow-based indices that measure flow performance. The measurement of the Initial Flow Index (IFI) was done immediately after mixing with a standard flow-table test according to JIS A1150-JSA 2014 [

21], whereby the spread diameter is normalized with the reference mixture (FA/S = 0%). The determination of the Flow Retention Index (FRI) was done after 15 minutes of casting to determine the capacity of the mixtures to sustain the flowability for a certain duration. The two indices were determined using standardized procedures that allow comparison of mixtures that use various types of fly ash and their replacement levels.

2.3.3. Mechanical Performance Tests

Multi-index was used to assess mechanical performance through measurement of strength behavior other than compressive strength. The compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength tests were performed per the provisions in JIS A1108-JSA 2006a [

22], JIS A1113-JSA 2006c [

23], and JIS A1106-JSA 2006b [

24], respectively. The experiments were carried out at a curing age of 1, 3, 7 and 28 days under steam-curing environment with a calibrated universal testing machine (UTM). Tests of compressive and splitting tensile strength were performed on cylindrical specimens measuring (50 x 100) mm; flexural strength test was test on prismatic specimens with measurements (40 x 40 x 160) mm.

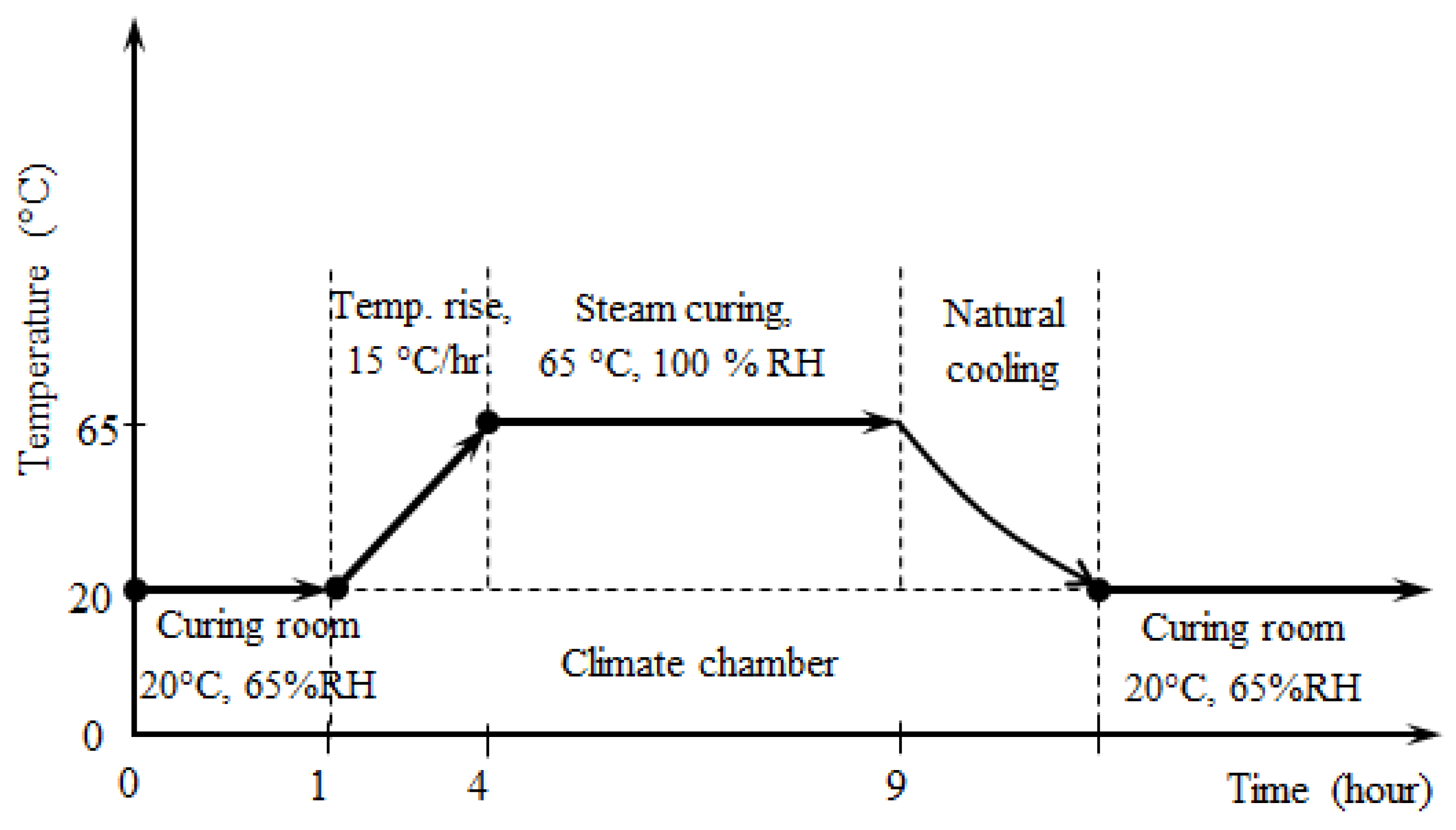

Figure 2 [

25] shows the steam-curing regime to which all specimens of ESCC are subjected. Plastic sheets were applied immediately after casting, and the molds were kept in a curing room with 20 ± 1 °C, and 65 ± 5% RH. The specimens were then placed under control conditions in a steam chamber as the temperature was brought up to 65 °C with a 15 °C/h increment. The temperature was kept at this level throughout 5 h and then the specimens were left to cool naturally to 20 °C. Demolding was performed on the day after casting and all the specimens were then kept at 20 °C and 65% RH until the required ages of testing. Three specimens were used in each mixture and each curing age. All mixtures were subjected to the same conditions of curing and testing to make a meaningful comparison.

The reference compressive strength-based indicator was the Strength Activity Index (SAI) introduced in ASTM C618 [

20] and was determined as the ratio of compressive strength of fly ash modified mixtures to the strength of the reference mixture (FA/S = 0%). To supplement SAI, Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) were suggested in this research as tensile- and flexural-based indices similar to SAI. The values of normalized tensile and flexural strength were used to derive these indices, which gave a complete view of mechanical performance and binder synergy as opposed to compressive strength.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Integrated IFI–FRI Fresh-State Performance Analysis

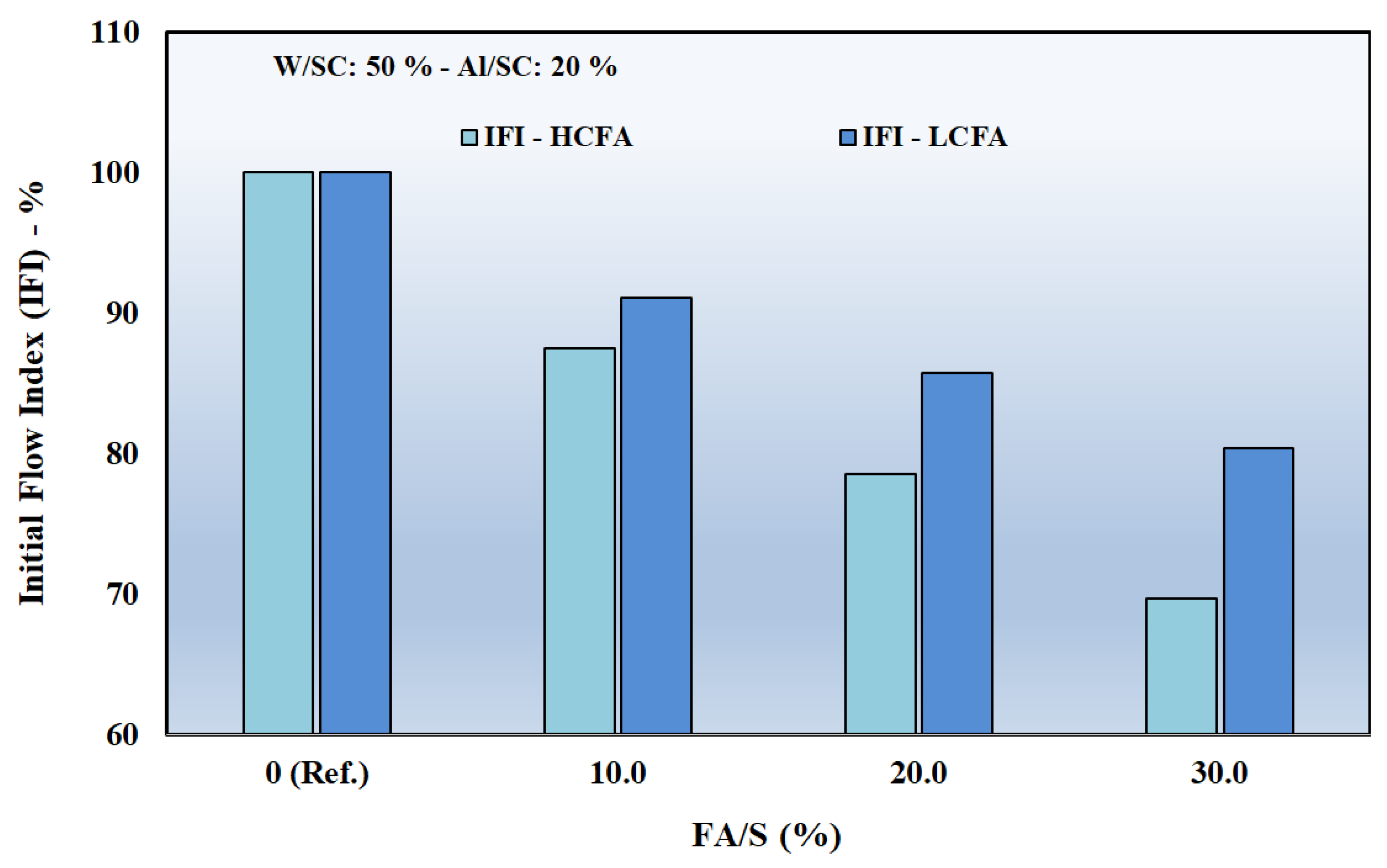

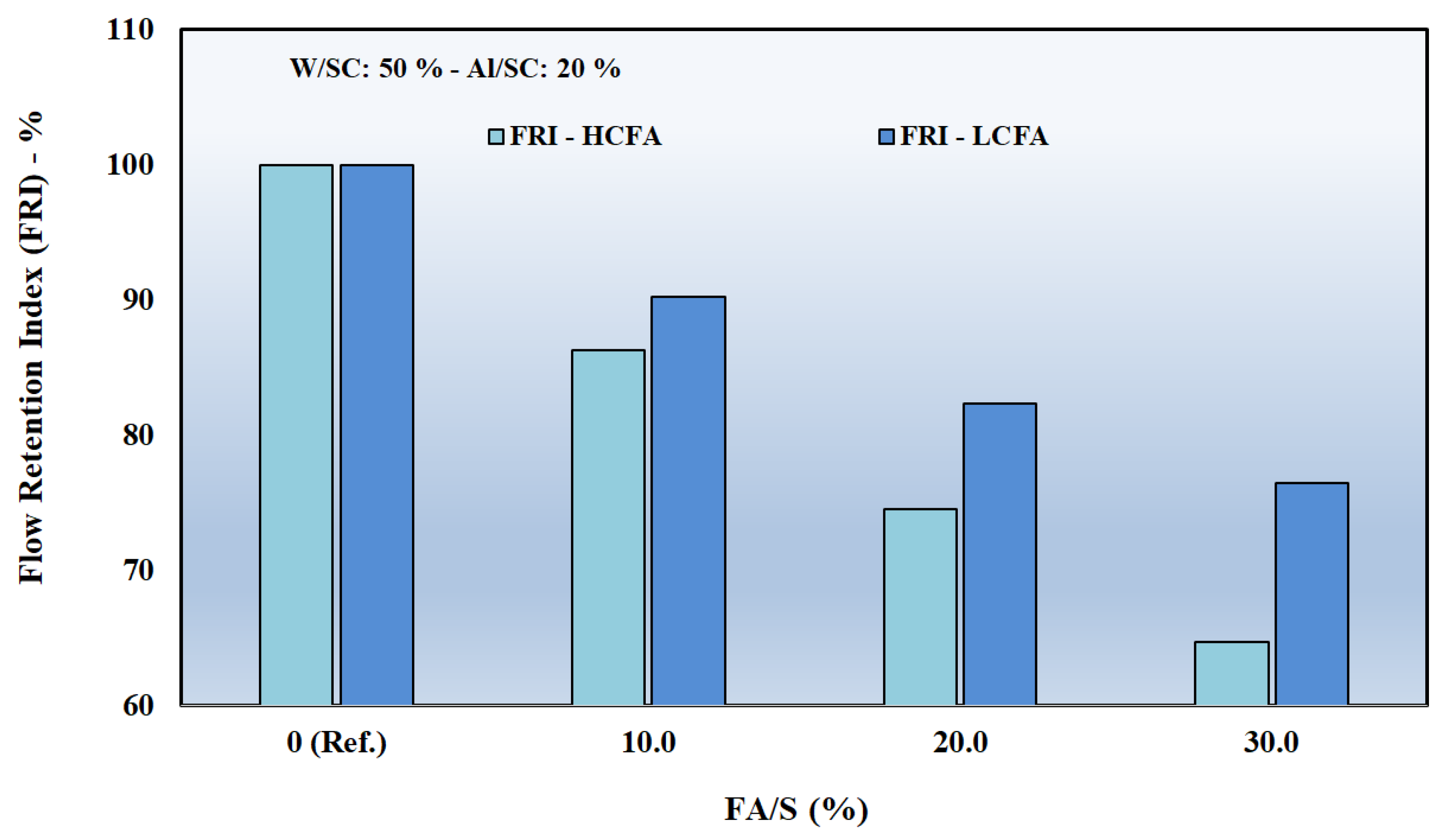

To quantitatively measure the fresh-state performance of the ESCC mixtures, the Initial Flow Index (IFI) and Flow Retention Index (FRI) were used to measure the performance of the mixtures in terms of initial flowability and time-dependent workability retention as a function of the FA/S ratio, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

In both HCFA and LCFA based systems, there was a systematic reduction in fresh-state performance with increasing levels of fly ash replacement. The mixtures of reference (FA/S = 0%) had defined IFI and FRI values of 100% as normalization baselines to be used in comparative evaluation and not as indicators of absolute performance.

At 10% FA/S, IFI values reduced to about 87% in the case of HCFA and 91% in the case of LCFA as the increasing solid content and surface area with the addition of fly ash became apparent. An additional decrease was observed at 20% FA/S where IFI decreased to approximately 78% of HCFA and 85% of LCFA, which implies higher internal friction and partial blockage of particle packing. On the maximum replacement (30% FA/S), IFI obtained minimum values of almost 70% of HCFA and 80% of LCFA, which indicated a significant loss of original flowability.

The same tendency was observed with a more significant trend towards flow retention behavior. FRI values were relatively high in 10% FA/S, and this was around 86% of HCFA and 90% of LCFA, indicating that there was minimal loss of workability with time. Nevertheless, as FA/S increased to 20%, FRI decreased more significantly to approximately 74% in the case of HCFA and 82% in the case of LCFA. HCFA mixtures suffered a severe impoverishment of workability retention at 30% FA/S with FRI values falling to just under 65% compared to the relatively more stable LCFA mixtures with FRI values of around 76%.

In general, the IFI-FRI analysis indicates that the fresh-state performance of the LCFA-incorporated mixtures was better at the intermediate and high replacement rates. The prolonged flowability of LCFA is due to its low calcium content and late reactivity at early ages. In comparison, higher availability of calcium in the HCFA systems leads to faster responses and hence greater loss of flowability and reduced workability retention at high FA/S ratios.

3.2. Mechanical Performance Indices

Mechanical performance of the ESCC mixtures was measured on the basis of a multi-index framework in which compressive, tensile, and flexural responses were determined separately, and the results were discussed as a whole to explain the overall mechanical performance. The main compressive-strength reference indicator was assumed to be Strength Activity Index (SAI), which is given in ASTM C618 [

20]. It is defined to be the product of the compressive strength of the fly ash modified mixtures divided by the compressive strength of the reference mixture (FA/S = 0%), normalized by definition to 100. It is not a performance standard, though it is a computation standard. Trying to assess the compressive behavior more, tensile-based and flexural-based indices were applied to assess other mechanical impacts that may have taken place due to the addition of the fly ash at various replacement levels. The multi-index method of this strategy with a synergistic approach can offer the capability to identify the development of strength in a localized and performance-based evaluation and continuously measure the definite roles of binder synergy and fly ash reactivity.

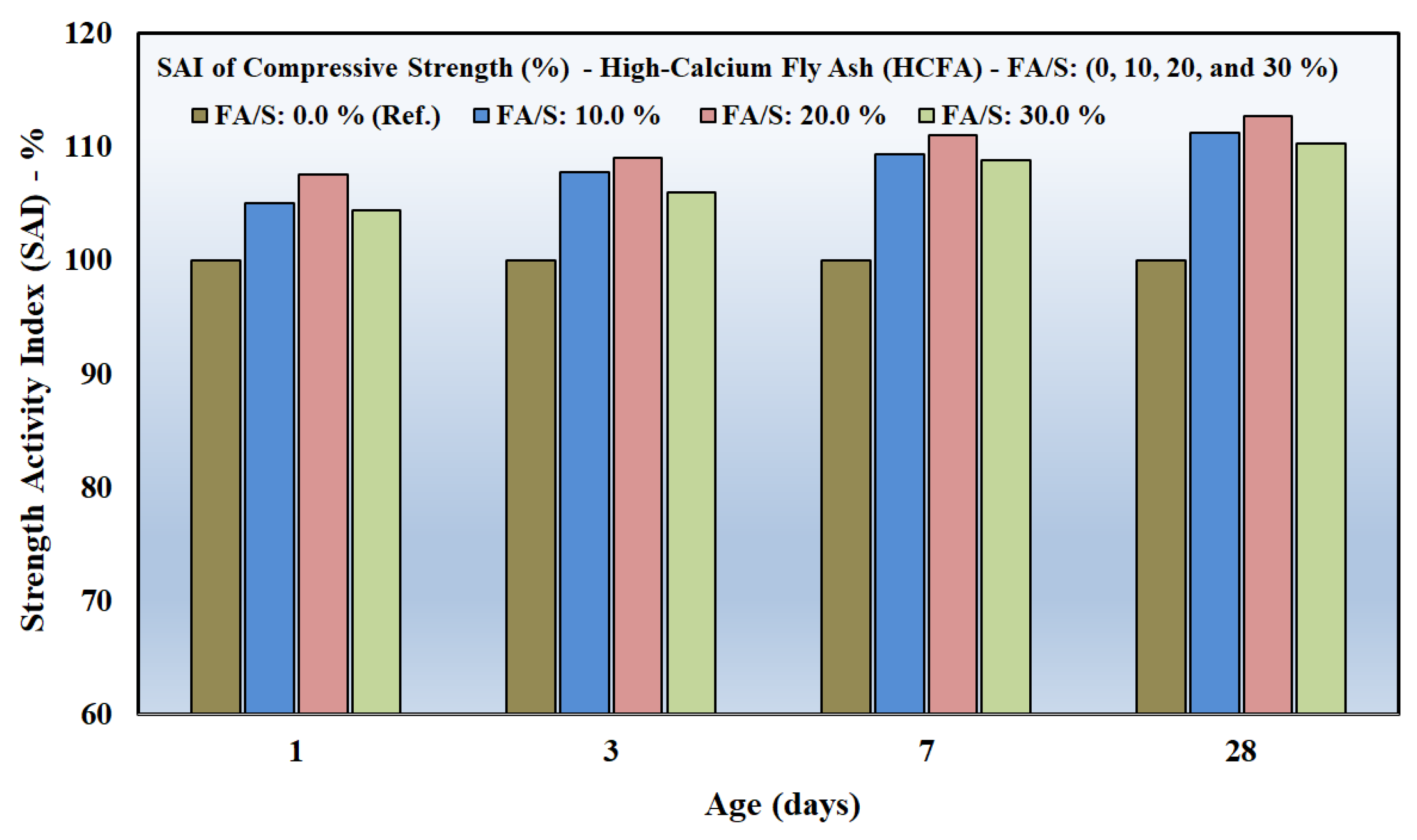

3.2.1. Strength Activity Index (SAI)

The Strength Activity Index (SAI) was initially analyzed to provide a compressive-strength standard in accordance with which the effect of fly ash replacement level and calcium content could be measured quantitatively. SAI, being a standardized value set in ASTM C618 [

20] is a normalized ratio of the compressive strength development compared to the reference mixture (FA/S = 0%), which can therefore be directly compared across various mixture compositions and curing ages. The development of SAI thus presents an important observation in the efficiency of the binder synergy and the degree to which HCFA and LCFA behave as load-bearing factors in conditions of steam-curing.

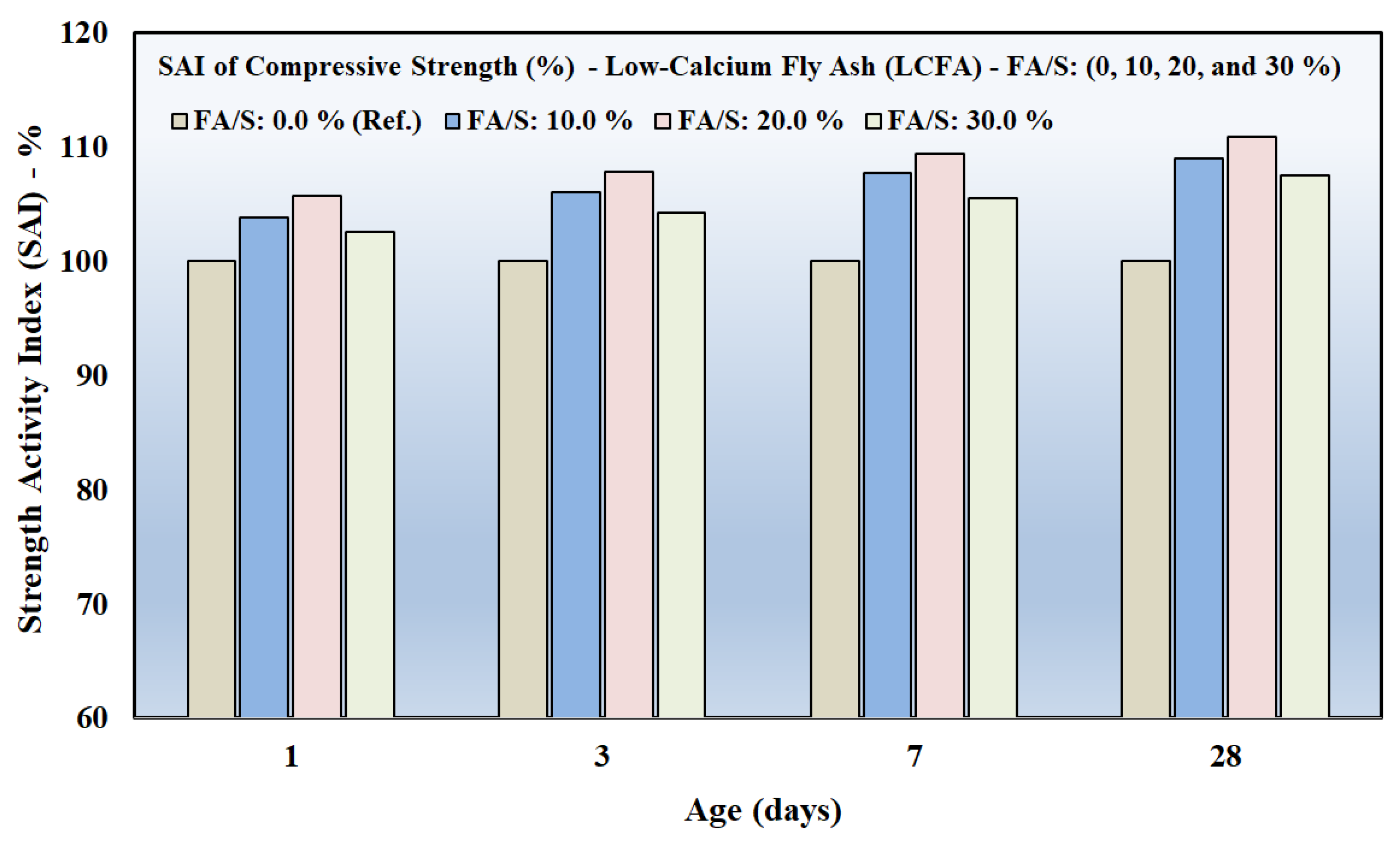

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 indicate the variation of the Strength Activity Index (SAI) with the curing age of mixtures using high-calcium fly ash (HCFA) and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), respectively, at different fly ash to sand ratios (FA/S), cured in steam.

In the case of HCFA-based mixtures (

Figure 5), compressive performance has a distinct dependence on replacement level. Mixtures with FA/S ratios of 10% and 20% already exceed the reference mixture at early ages (105% and 107%) at 1 day, respectively. This initial growth signifies the rapid growth of the HCFA. The beneficial effect increases at intermediate replacement levels as the curing progresses. At 3 and 7 days, the 20% FA/S blend has an SAI of around 109% and 111%, respectively, which is evidence of continued strength growth as a result of effective binder activation and a positive packing environment. This mixture achieves the maximum SAI value of about 112% at 28 days, which implies that the compressive strength gains are sustained with time.

Conversely, a compressive response is moderated when the replacement level is increased to 30% FA/S. The values of the SAI are above the reference level, 104% at 1 day and 110% at 28 days, but the relative improvement is not as significant. This trend implies that too much fly ash replacement also starts to neutralize the advantages of the availability of calcium by means of dilution effects and lower load-bearing matrix formation efficiency.

The overall pattern of mixtures with LCFA (

Figure 6) is the same, but the strength evolution is less rapid. The value of SAI rises with a steady level from 105% at 1 day to about 110% in 28 days at 20% FA/S. The maximum SAI values are slightly smaller than those observed with HCFA, which is due to the lower amounts of calcium and the slower kinetics of the process when using LCFA. However, the steady increase that is seen at the intermediate replacement levels proves that LCFA can be successfully used to increase compressive strength when in the right proportions. SAI values are close to the reference mixture at the 30% FA/S concentration and increase by 102%–107% in 1 and 28 days, respectively, and do not show a significant increase in values at the higher replacement ratios.

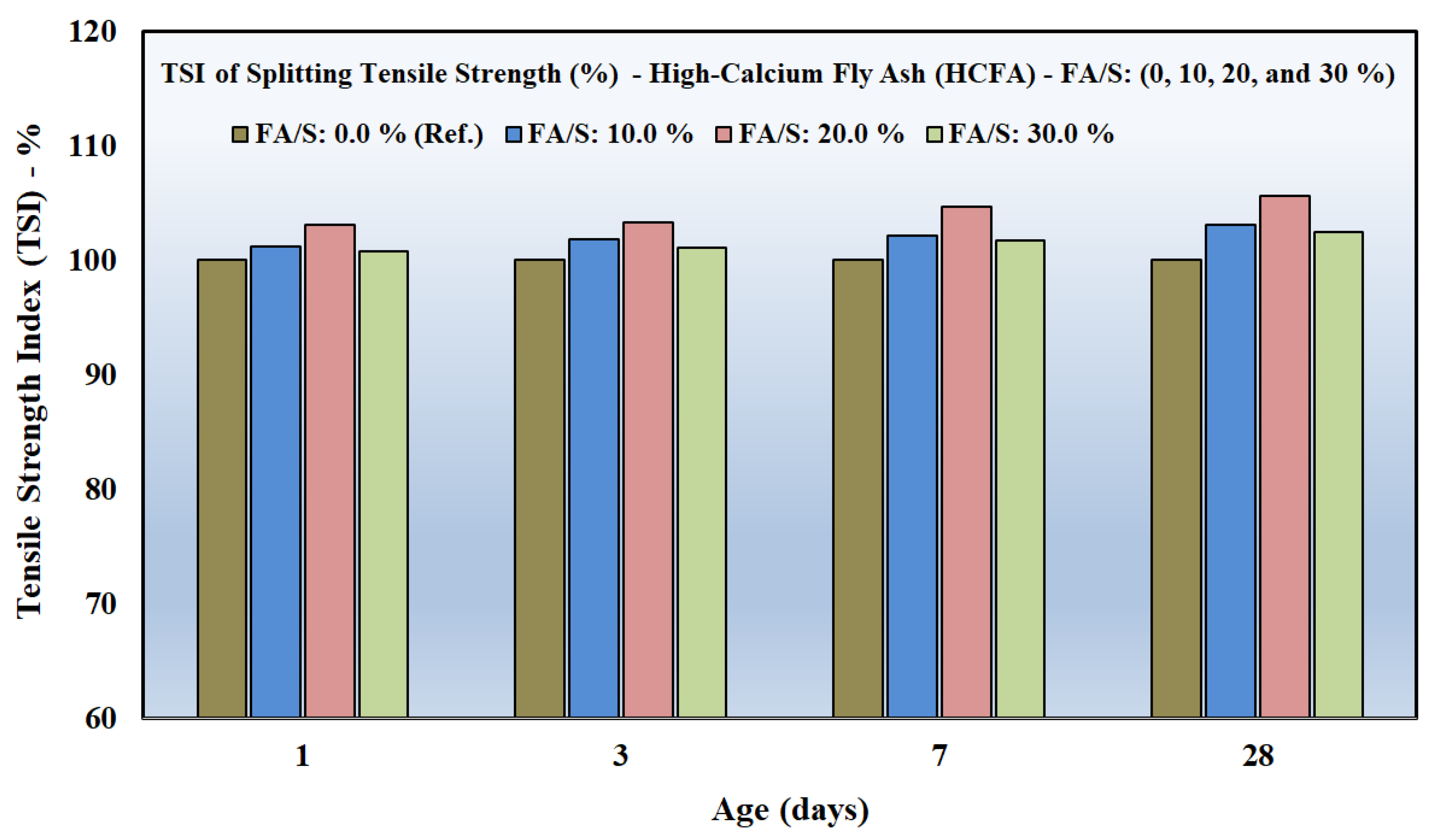

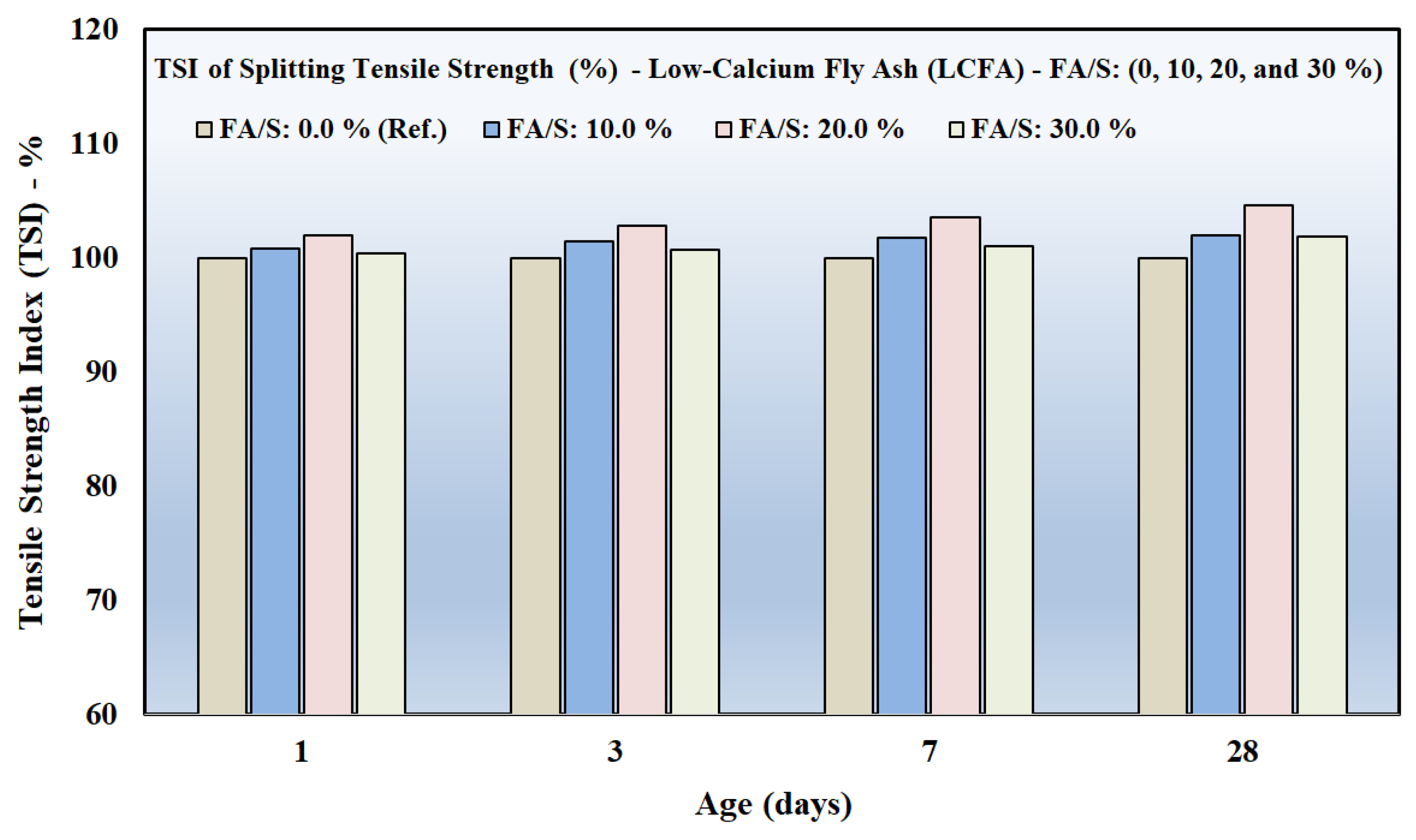

3.2.2. Tensile Strength Index (TSI)

Tensile strength shows a less sensitive response to fly ash replacement level than compressive strength, improvements being observed more at optimum proportion. Here, Tensile Strength Index (TSI) was utilized to assess the relative role of adding fly ash to splitting tensile performance vis-a-vis the reference mixture (FA/S = 0%). Through normalization of tensile strength development, TSI allows the direct comparison of the effect of fly ash type and replacement level on tensile resistance at various curing ages thus capturing mechanical effects that are not adequately reflected by compressive strength alone.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show how TSI changes with curing age in mixtures based on HCFA and LCFA respectively.

In the case of HCFA-based mixtures (

Figure 7), tensile improvement at low replacement concentration is modest. TSI values demonstrate that there is a small increase in TSI values between approximately 101% in 1 day and 103% in 28 days at 10% FA/S indicating that there are no significant improvements in tensile performance. There is a stronger improvement at the intermediate level of replacement of 20% FA/S where TSI levels are increased from about 103% in 1 day to 105% in 28 days. This tendency suggests that an optimized process of incorporating HCFA leads to better tensile load transfer in the hardened matrix due to better continuity of the matrix and redistribution of stress. On the other hand, mixtures with 30% FA/S do not exhibit any notable tensile strengthening, and TSI values do not vary significantly at different ages of curing, in the range of 101–102%, which implies that over-replacement does not contribute to tensile resistance enhancement.

Figure 8 shows that mixtures (LCFA-based) exhibit a similar pattern but are slightly smaller. TSI values at 20% FA/S grow consistently within a range of 102% at 1 day and 104% at 28 days, and this shows that LCFA can also improve tensile performance at optimum levels of incorporation. Nevertheless, with the higher replacement levels (30% FA/S), the tensile strength is improved only slightly, and TSI values appear the same as those of the reference mixture.

The tensile performance findings, in general, show that the positive influence of fly ash addition is optimized between a moderate replacement level of 20% FA/S of HCFA and LCFA that produce tensile performance results of about 105% and 104% at 28 days, respectively. The comparatively smaller scope of tensile improvement relative to compressive strength highlights the importance of tensile indices in isolation, which validates the fact that SAI in itself is a limited measure of the overall mechanical functionality of fly ash addition in alkali-activated eco-sustainable cementitious composites.

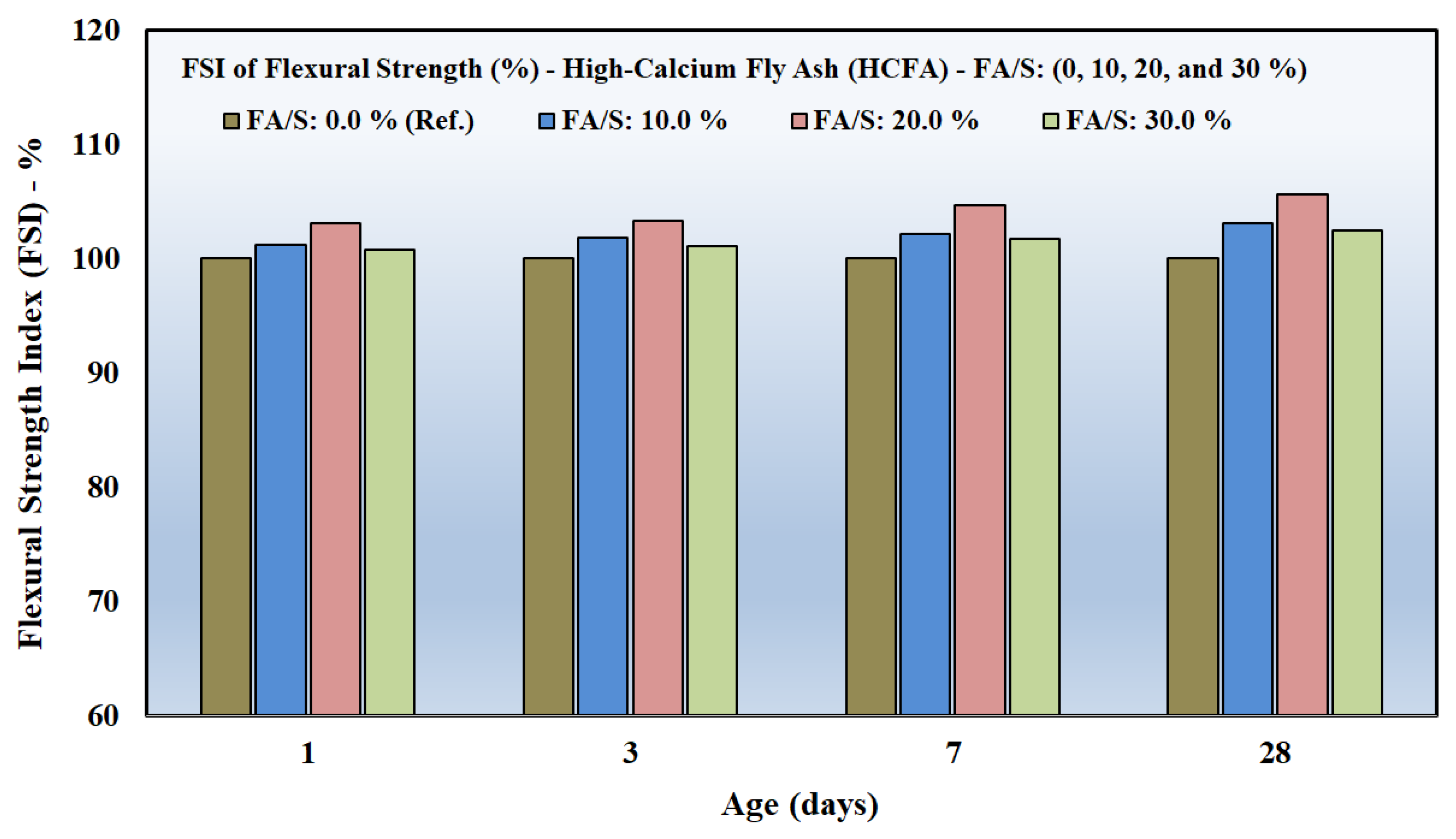

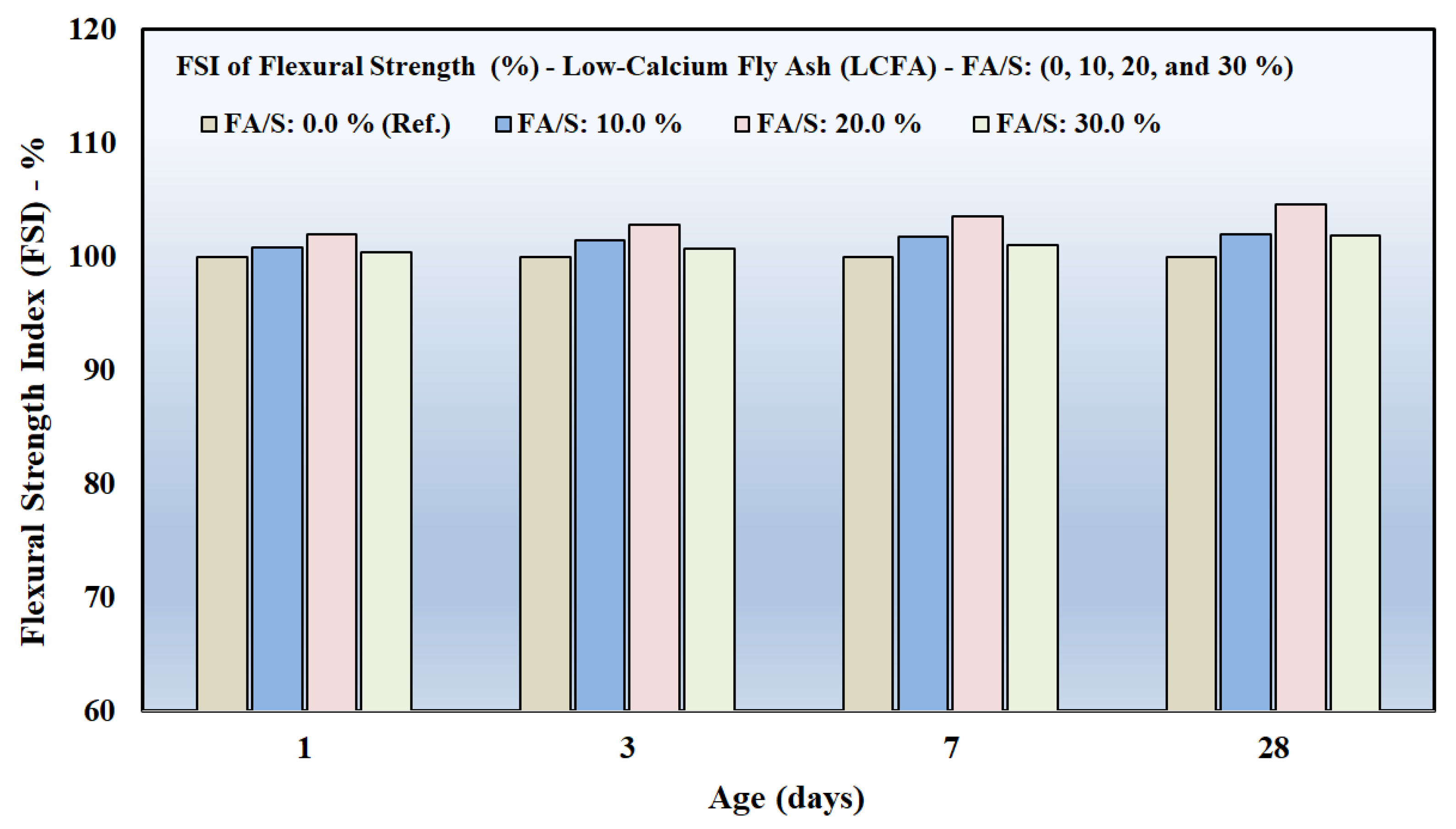

3.2.3. Flexural Strength Index (FSI)

Flexural strength is an expression of tensile resistance together with redistribution of stresses in the hardened matrix and thus is very sensitive to mixture composition. In this regard, the Flexural Strength Index (FSI) was used to assess the impact of fly ash addition on flexural performance when compared to the control mixture (FA/S = 0%). FSI allows the direct comparison of effects of binder synergy and replacement level by normalizing the effects on flexural strength development across curing ages.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the development of FSI to HCFA-based and LCFA-based mixtures, respectively.

In the HCFA-containing mixtures (

Figure 9), flexural performance grows progressively with the age of curing, particularly in the intermediate levels of replacement. At 10% FA/S, the FSI increases modestly in an average of 102% to 104% at 1 day and 28 days, respectively, and is not a notable enhancement in bending resistance. The highest growth is noted at the 20% FA/S, where the FSI values are growing from an average of about 104% at 1 day to about 106% at 28 days, which represents the best flexural performance of HCFA systems. Conversely, flexural gains are restricted in mixtures where 30% FA/S is involved and FSI values are between 101% and 103%, which means that flexural performance is restricted by over-substitution, dilution, and lack of maturity.

The same tendency is observed in LCFA-based mixtures (

Figure 10), but with a lower absolute value. Intermediate LCFA incorporation also improves flexural performance when in the right proportion, as FSI rises by about 102% at 1-day to about 105% at 28 days with a ratio of FA/S at 20%. Like the HCFA systems, increasing the replacement (30% FA/S) leads to marginal flexural enhancement, and the FSI values are near to the reference mixture.

Comprehensively, the flexural findings indicate that an FA/S ratio of about 20% generates the optimum balance in flexural strength development in both HCFA and LCFA systems with maximum FSI values of 106% and 105% at 28 days, respectively. The close correlation between flexural and tensile performance patterns shows the usefulness of intermediate fly ash inclusion in enhancing effective stress redistribution and the integrity of the matrix. These results also confirm the strength of the proposed multi-index system in covering mechanical contributions that are not limited to compressive strength assessment.

3.2.4. Integrated Multi-Index Performance Assessment

Multi-index mechanical analysis demonstrates that intermediate levels of fly ash replacement are conclusive in the optimization of compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths. Specifically, the uniformity in determining the optimum fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratio of about 20% in the Strength Activity Index (SAI), Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) is indicative of the soundness of balanced binder synergy at alkali-activated conditions. This can be noted in line with the trends that have been observed in past research on alkali-activated systems wherein moderate replacement of fly ash can increase the efficiency of the reaction and the formation of the strength, whereas excessive replacement may cause dilution effects and lower structural efficiency [

26,

27].

In addition to validating these established trends, the given study goes further to broaden existing knowledge by utilizing a systematized multi-index framework that assesses mechanical performance over and above the traditional compressive strength-based models [

28]. The framework, which is proposed by combining tensile-based index and flexural-based index in addition to the standardized SAI reference, allows the more comprehensive and performance-focused interpretation of fly ash reactivity, and binder interaction. By doing so, it becomes possible to better delineate high-calcium fly ash (HCFA) and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) systems and gain a better understanding of the mechanical implications of fly ash usage as a fine-aggregate substitute.

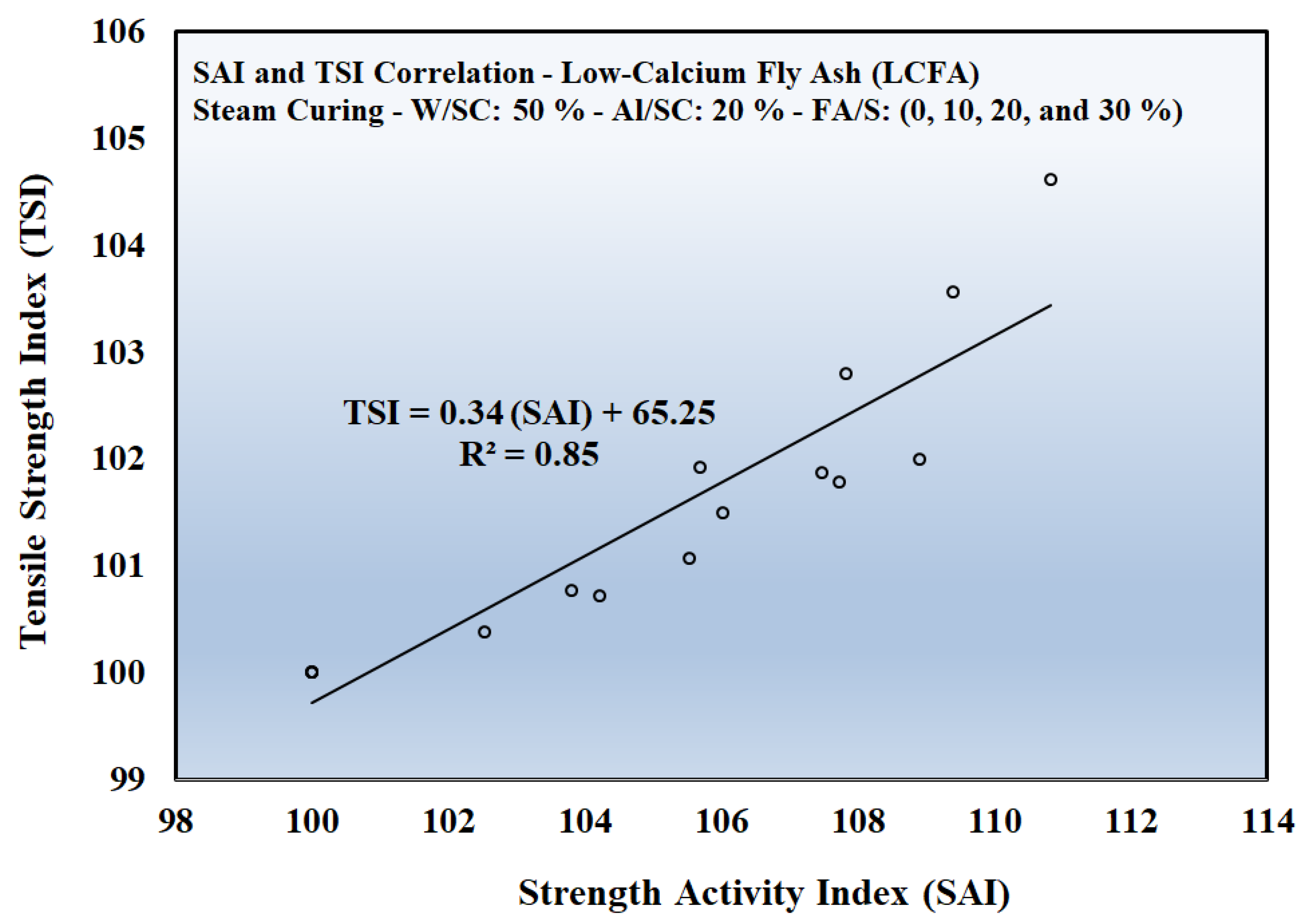

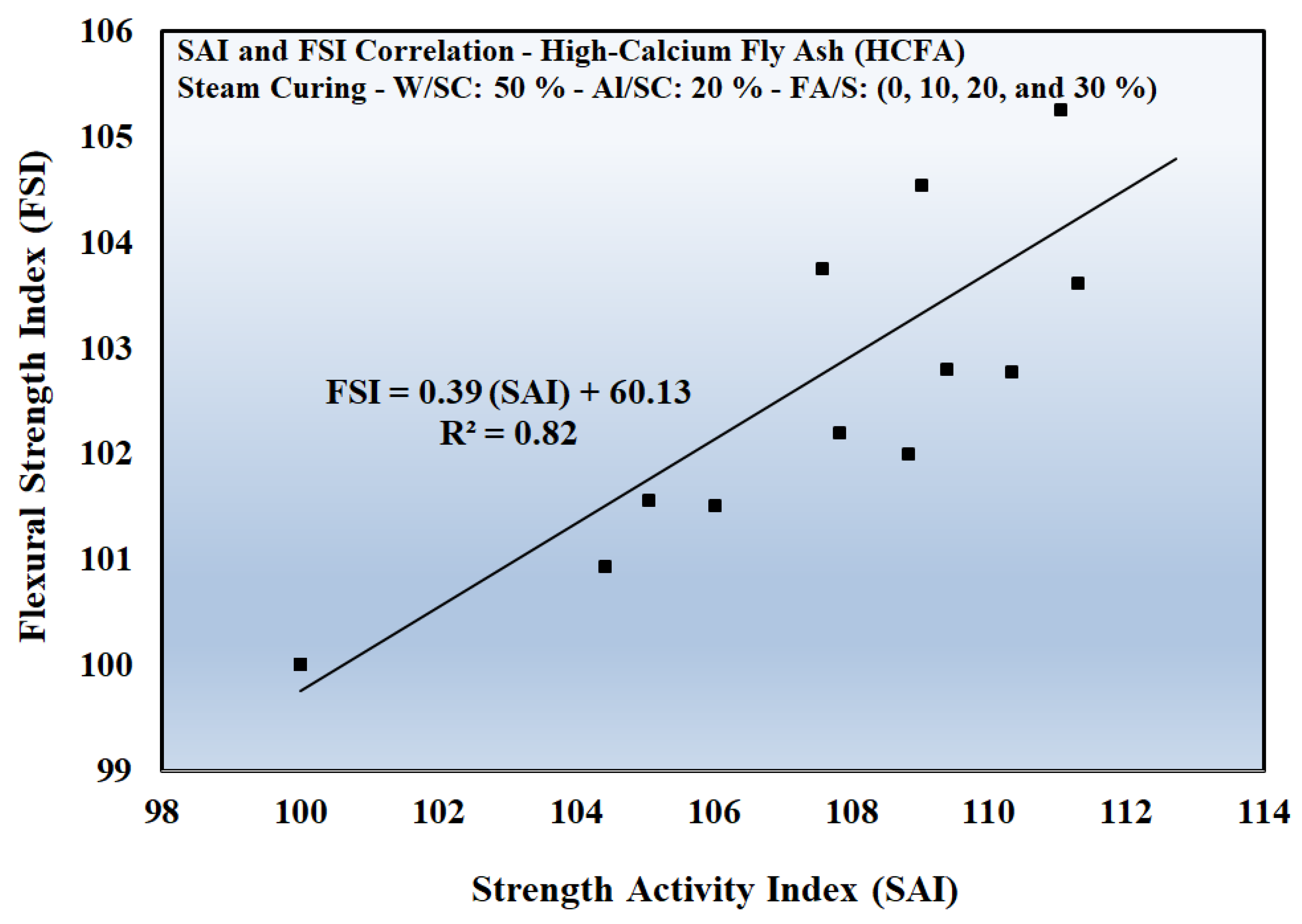

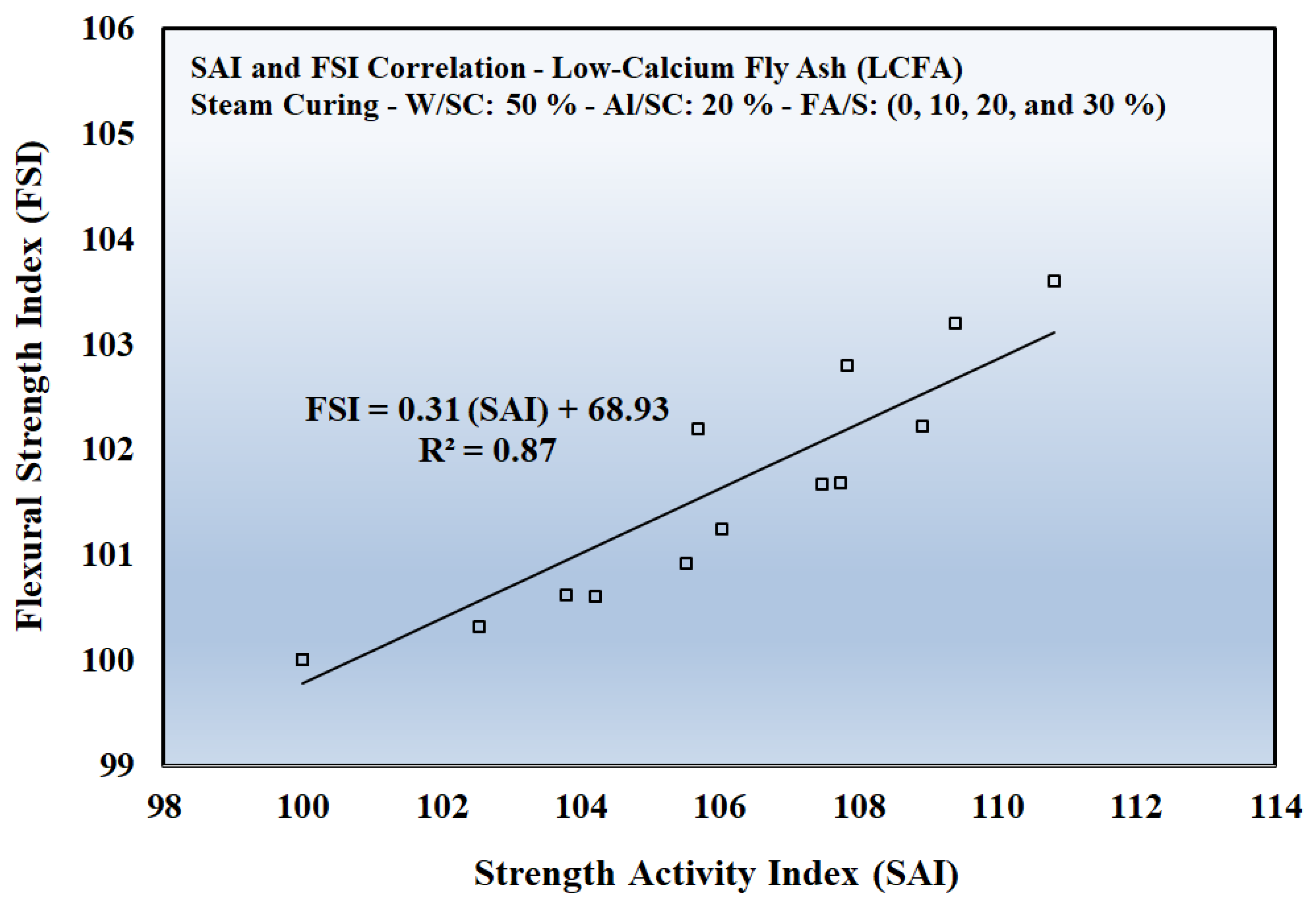

Correlation analyses were used to determine the quantitative relationship between SAI and the corresponding TSI and FSI value as a way of quantitatively exploring the relationship between compressive strength development and tensile-flexural performance.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the SAI-TSI relationships for the mixtures prepared with HCFA and LCFA, while

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the SAI-FSI relationships for the same mixtures.

Regarding the SAI-TSI relationship, there is a linear correlation between HCFA mixtures with an R

2 of 0.81 (

Figure 11), which implies that there is strong but moderately scattered relationship between compressive and tensile performance. This is an indication that compressive strength enhancement is important to tensile resistance, but other factors, including crack initiation behavior and stress transfer efficiency, also affect tensile performance in calcium-rich systems. Conversely, LCFA mixtures exhibit a somewhat greater correlation, supported by an R

2 value of 0.85 (

Figure 12), and a more consistent relationship between compressive and tensile strength development and controlled by the reaction products of aluminosilicate.

The same trend is found in flexural performance. According to

Figure 13, HCFA-based mixtures provide an SAI-FSI correlation, with the R

2 value equal to 0.82, meaning that flexural strength is still closely related to compressive strength enhancement in calcium-rich mixtures. In contrast, LCFA mixtures have a more consistent SAI-FSI relationship, and the R

2 of the model is 0.87 (

Figure 14), indicating a more gradual but consistent transition of compressive strength into flexural resistance.

Together, the SAI-TSI and SAI-FSI correlations indicate that tensile and flexural performance cannot be inferred with any reliability based on compressive strength only, especially in fly ash systems that are regulated by alternative reaction mechanisms. The variation in the behavior of mixtures of HCFA and LCFA underlines the importance of the reactivity of fly ash and its interaction with the binder in regulating the transfer of stress and redistribution of loads. These findings confirm the flaws of compressive strength-based evaluation and support the proposed multi-index framework as a useful and performance-based strategy for gauging the mechanical synergy of eco-sustainable cementitious composites.

3.3. Mineralogical Interpretation of Performance Trends

To justify the tendencies of fresh-state and mechanical performance, the mineralogical description of the constituent materials was investigated further regarding their reactivity and influence on strength development.

Figure 15 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) that indicate the mineralogical characteristics upon which reactivity variations are based and the implications on mechanical performance.

SC has a relatively crystalline nature, which is evidenced in the profiles of the diffractograms, making the material display large crystalline peaks, which are associated with the presence of various phases, such as quartz and calcium-bearing compounds. Both HCFA and LCFA, however, exhibit a diffuse hump in the 2θ range of about 25–35°, suggesting that it is composed of mostly discrete aluminosilicate glassy phases. The lower intensities and olivine formations of the crystalline peaks of the fly ash patterns reflect that the crystalline peaks are more amorphous than SC, which is a well-known dominant cause of alkali-activation reactivity.

This amorphous aluminosilicate hump and its presence give the mechanistic explanation to the differences in mechanical response observed in HCFA- and LCFA-based mixture. The presence of reactive amorphous phases together with other calcium-based constituents in the HCFA systems promotes the simultaneous generation of C–(A)–S–H and N–A–S–H type reaction products, which consequently leads to rapid strength build-up and improved compressive, tensile, and flexural behaviors at intermediate levels of replacements. On the other hand, the amorphous structure of LCFA is less homogeneous, and the amount of calcium is also lower, so its reaction kinetics is primarily determined by the polymerization of aluminosilicate. Such a mechanism helps to achieve better workability retention and slower and more stable development of mechanical properties, with relatively lower peak strength indices than HCFA systems.

Significantly, the XRD results also give an explanation as to why the best performance is seen at an FA/S ratio of about 20%. A positive trade-off between the availability of amorphous phases and good binder packing results in an effective densification of the matrix and the transfer of stress with minimal dilution of the reactants at this replacement level. Increased replacement levels cause the decreased contribution of crystalline slag phases and incomplete activation of the amorphous fly ash fraction to limit reaction efficiency as indicated by decreasing strength indices. Generally, the mineralogical data prove that amorphous material and the presence of calcium indicated by XRD are key parameters dictating fly ash activity, binder interaction, and the multi-index mechanical behaviors of eco-sustainable cementitious composites.

4. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that a multi-index performance framework is a robust and well-developed framework for synergistic interaction between binder composition and fly ash reactivity in eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC). The proposed framework, by incorporating fresh-state and mechanical indices, allows this performance-based assessment to go beyond the traditional compressive strength-based methods of assessment.

Fresh-state performance, as measured by Initial Flow Index (IFI) and Flow Retention Index (FRI), decreased in a systematic way with the fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratio of the two types of fly ash, where mixtures based on LCFA always showed better flow retention. Optimal mechanical performance was found at the mid-range replacement of about 20% FA/S that resulted in the most favorable compressive, tensile, and flexural response of HCFA and LCFA systems. Behavior at high replacement levels was shown to be less performance because of dilution effects and reduced binder packing performance.

Correlation analyses between the Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile and Flexural Strength Index (TSI and FSI) were found to demonstrate that tensile and flexural performance cannot be predicted reliably on compressive strength alone, especially in fly ash systems that follow different reaction mechanisms. These results indicate that a multi-index assessment is needed to measure mechanical synergy and load-transfer characteristics of alkali-activated composites.

The trends in the performance of mineralogical interpretation showed that the amplitude of availability of amorphous phases and calcium level, especially at 20% FA/S are critical factors that determine the efficiency of the reaction, the densification of the matrices, and the transfer of stress. High replacement levels inhibit mechanical performance because of the incomplete activation of the amorphous phases and a decreased contribution by crystalline slag constituents. All these results confirm the relevance of the proposed multi-index framework as a robust methodological basis for rational mixture optimization and development of eco-sustainable cementitious composites.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia under grant No. (IPP: 266-829-2025). The author, therefore, acknowledges with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Adak, D.; Kapoor, K.; Tabish, M. Low carbon concrete: advancements, challenges and future directions in sustainable construction. Discover Concr. Cem. 2025, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statkauskas, M.; Vaičiukynienė, D.; Grinys, A. Mechanical properties of low calcium alkali activated binder system under ambient curing conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheu, P.S.; Ellis, K.C.; Varela, B. Comparing the environmental impacts of alkali activated mortar and traditional Portland cement mortar using life cycle assessment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 96, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelekshmi, G.; Sankar, B.; D, R.K.; Kumar, A. Correlation of mechanical and durability properties of binary and ternary blended high-performance concrete. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 529, 01021. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Lima, L.M.; Sun, Y.; Dehn, F.; Provis, J.L.; Ye, G.; Schutter, G.D. Future perspectives for alkali-activated materials: from existing standards to structural applications. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2023, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.E. Alkali-activated materials: the role of molecular-scale research and lessons from the energy transition to combat climate change. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2020, 4, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batuecas, E.; Ramón-Álvarez, I.; Sánchez-Delgado, S.; Torres-Carrasco, M. Carbon footprint and water use of alkali-activated and hybrid cement mortars. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.K.; Kato, M.; Kurumisawa, K. Recent advances in X-ray computed tomography for alkali-activated materials: A review. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2023, 21, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, Z.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K. A review on durability of alkali-activated system from sustainable construction materials to infrastructures. ES Mater. Manuf. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hita, M.J.; Criado, M. Influence of the fly ash content on the fresh and hardened properties of alkali-activated slag pastes with admixtures. Materials 2022, 15, 992, https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/3/992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Wu, Z.; Han, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhou, Z.; Du, P.; Wu, F.; Du, S.; Huang, Y. Effects of calcium content of fly ash on hydration and microstructure of UHPC. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawsari, S.; Kampmann, R.; Harnisch, J.; Rohde, C. Setting time, microstructure, and durability of low-calcium fly ash/slag geopolymer: A review. Materials 2022, 15, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, S.; Baran, A.; Bicakci, S.N.; Turkmenoglu, H.N.; Atahan, H.N. Fresh, setting, and hardened properties of fly ash concrete with nano-silica. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, S. Optimizing the usage of fly ash in concrete mixes. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiddine, S.; Soualhi, H.; Benabed, B.; Belaïdi, A.S.E.; Kadri, E.-H. Rheological behavior of eco-friendly mortars with SCMs and superplasticizers. Epitoanyag 2021, 73, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, C.; Li, N.; Jiao, D.; Yuan, Q. Rheology of alkali-activated materials: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Shi, C.; Yuan, Q.; An, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Effect of constituents on rheological properties of fresh concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 83, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahhal, M.F.; Kim, T.; Hajimohammadi, A. Distinctive rheological and temporal viscoelastic behaviour of alkali-activated fly ash/slag pastes: A comparative study with cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 144, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, S.; Hu, J.; Wang, H. Fresh and hardened properties of alkali-activated fly ash/slag binders: Effect of fly ash source, surface area, and additives. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2022, 11, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-19: Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

-

JIS A1150; Method of Test for Slump Flow of Concrete. JSA (Japanese Standards Association): Tokyo, Japan, 2014.

-

JIS A1108; Method of Test for Compressive Strength of Concrete. JSA (Japanese Standards Association): Tokyo, Japan, 2006.

-

JIS A1113; Method of Test for Splitting Tensile Strength of Concrete. JSA (Japanese Standards Association): Tokyo, Japan, 2006.

-

JIS A1106; Method of Test for Flexural Strength of Concrete. JSA (Japanese Standards Association): Tokyo, Japan, 2006.

- El-Wafa, M.A. Eco-efficient alkali-activated slag–fly ash mixtures for early-strength enhancement. Eng. 2025, 6, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y. Durability properties of sustainable alkali-activated cementitious materials as marine engineering materials: A review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2022, 17, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, W.; Li, X.; Peng, H. Study of the mechanical properties and microstructure of alkali-activated fly ash–slag composite cementitious materials. Polymers 2023, 15, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, W.F.; Segadães, A.M.; Cruz, R.C.D. Assessing the drying sensitivity of alkali-activated binders through mechanical reliability: Effect of particle size and packing. Materials 2024, 17, 5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental methodology and sample preparation.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental methodology and sample preparation.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the steam-curing regime [

25].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the steam-curing regime [

25].

Figure 3.

Initial Flow Index (IFI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratios.

Figure 3.

Initial Flow Index (IFI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratios.

Figure 4.

Flow Retention Index (FRI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratios.

Figure 4.

Flow Retention Index (FRI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different fly ash-to-sand (FA/S) ratios.

Figure 5.

Strength Activity Index (SAI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 5.

Strength Activity Index (SAI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 6.

Strength Activity Index (SAI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 6.

Strength Activity Index (SAI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 7.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 7.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 8.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 8.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 9.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 9.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 10.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 10.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of LCFA-based mixtures at different FA/S ratios and curing ages under steam curing.

Figure 11.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile Strength Index (TSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating HCFA.

Figure 11.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile Strength Index (TSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating HCFA.

Figure 12.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile Strength Index (TSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating LCFA.

Figure 12.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile Strength Index (TSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating LCFA.

Figure 13.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating HCFA.

Figure 13.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating HCFA.

Figure 14.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating LCFA.

Figure 14.

Correlation between Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) for ESCC mixtures incorporating LCFA.

Figure 15.

XRD Patterns of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

Figure 15.

XRD Patterns of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

| Chemical Compositions (%) |

CaO |

SiO2

|

Al2O3

|

MgO |

Fe2O3

|

Na2O |

TiO2

|

P2O5

|

LOI |

Slag Cement

(SC) |

43.1 |

32.5 |

13.5 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

High-Calcium Fly Ash

(HCFA) |

18.8 |

48.8 |

19.8 |

1.5 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

1.7 |

Low-Calcium Fly Ash

(LCFA) |

6.3 |

57.6 |

26.5 |

1.2 |

4.2 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

0.3 |

1.5 |

Table 2.

Physical properties of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

Table 2.

Physical properties of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA).

| Physical Properties |

Specific gravity

(g/cm3) |

Specific surface area

(cm2/g) |

Average particle size D50 (μm) |

Slag Cement

(SC) |

2.8 |

3750 |

6.48 |

High-Calcium Fly Ash

(HCFA) |

2.8 |

3780 |

16.25 |

Low-Calcium Fly Ash

(LCFA) |

2.14 |

3630 |

18.35 |

Table 3.

Mix proportions of eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC).

Table 3.

Mix proportions of eco-sustainable cementitious composites (ESCC).

FA/S (%) -

HCFA - LCFA |

W/SC

(%) |

AL/SC

(%) |

Mix Proportioning (kg/m3) |

Slag

Cement

(SC) |

Water

(W) |

Alkali-

Activator

(AL) |

Fly Ash

(FA) |

Sand

(S) |

FA/S: 0.0% -

Reference |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

0 |

1200 |

FA/S: 10% -

HCFA |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

100 - HCFA |

1100 |

FA/S: 10% -

LCFA |

100 - LCFA |

1100 |

FA/S: 20% -

HCFA |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

200 - HCFA |

1000 |

FA/S: 20% -

LCFA |

200 - LCFA |

1000 |

FA/S: 30% -

HCFA |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

300 - HCFA |

900 |

FA/S: 30% -

LCFA |

300 - LCFA |

900 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).