Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Binder Raw Materials

| Coarse aggregate size (mm) | Percentage composition |

| 10 | 30 |

| 12 | 20 |

| 14 | 30 |

| 20 | 20 |

2.2. Aggregates

2.3. Superplasticizer

2.4. Sample Designation

2.5. Experimental Design

2.5.1. Workability

| Mixes | Flyash %FAs | Waste glass %WG | OPC % |

w/b ratio |

OPC Kg/m3 | Flyash Kg/m3 |

WG Kg/m3 | Fine agg. Kg/m3 |

Coarse Agg. Kg/m3 |

water SSD | SP | Total density | |

| C100FA0G0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.4 | 350 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 753 | 1120 | 175 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

| C80FA20G0 | 20 | 0 | 80 | 0.4 | 280 | 70.0 | 0.0 | 760 | 1120 | 168 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

| C80FA15G5 | 15 | 5 | 80 | 0.4 | 280 | 52.5 | 17.5 | 760 | 1120 | 168 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

| C80FA10G10 | 10 | 10 | 80 | 0.4 | 280 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 760 | 1120 | 168 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

| C80FA5G15 | 5 | 15 | 80 | 0.4 | 280 | 17.5 | 52.5 | 760 | 1120 | 168 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

| C80FA0G20 | 0 | 20 | 80 | 0.4 | 280 | 0.0 | 70 | 760 | 1120 | 168 | 1.80 | 2400 | |

2.5.2. Water Absorption

2.5.3. Compressive Strength Test

2.5.4. Characterization and Morphology of the Specimens

2.6. Mix Design and Sample Preparations

2.6.1. Mix Design

2.6.2. Sample Preparation

3. Discussion of Results

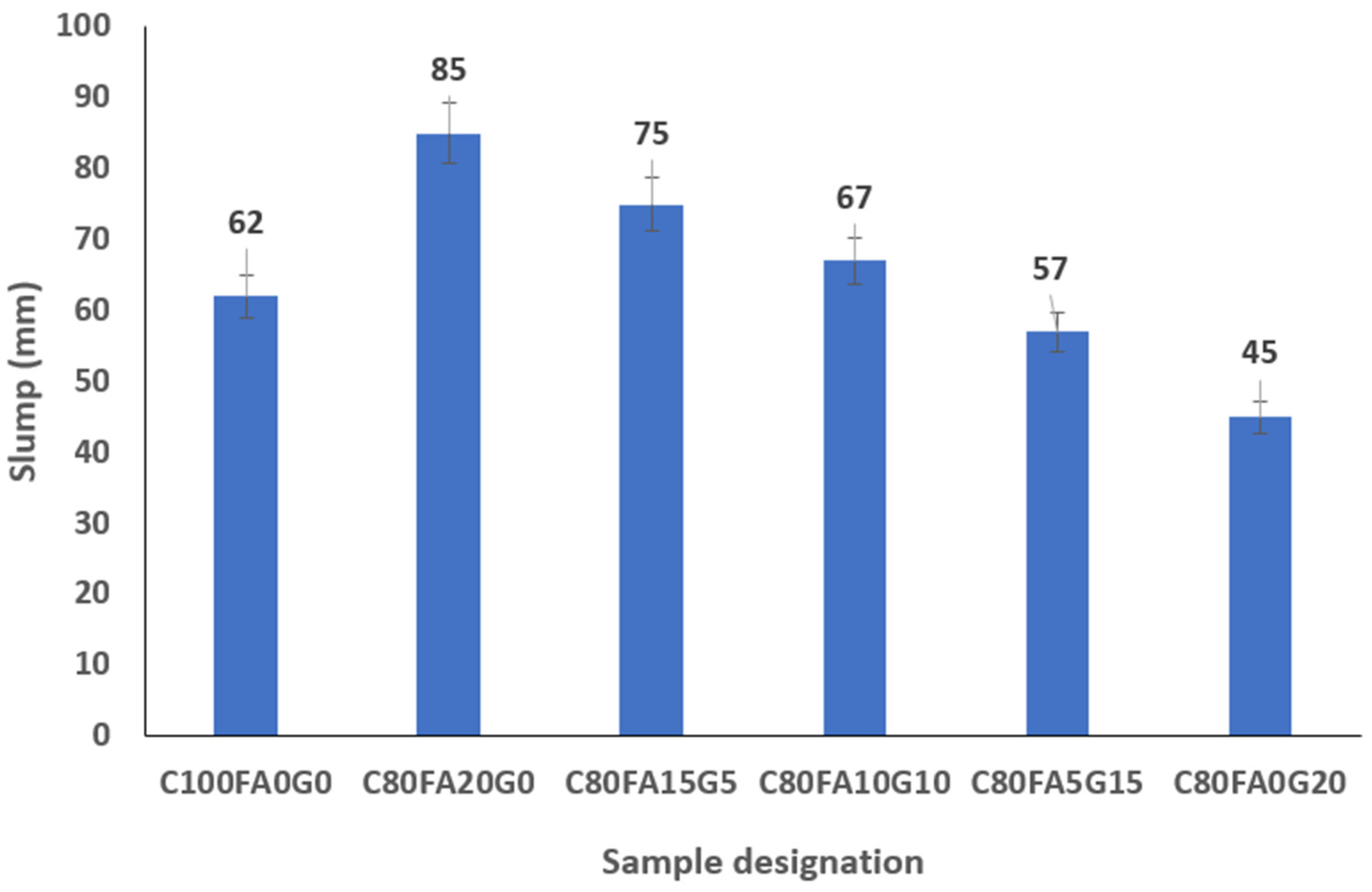

3.1. Workability of Glass-Flyash Ternary Blended Concrete

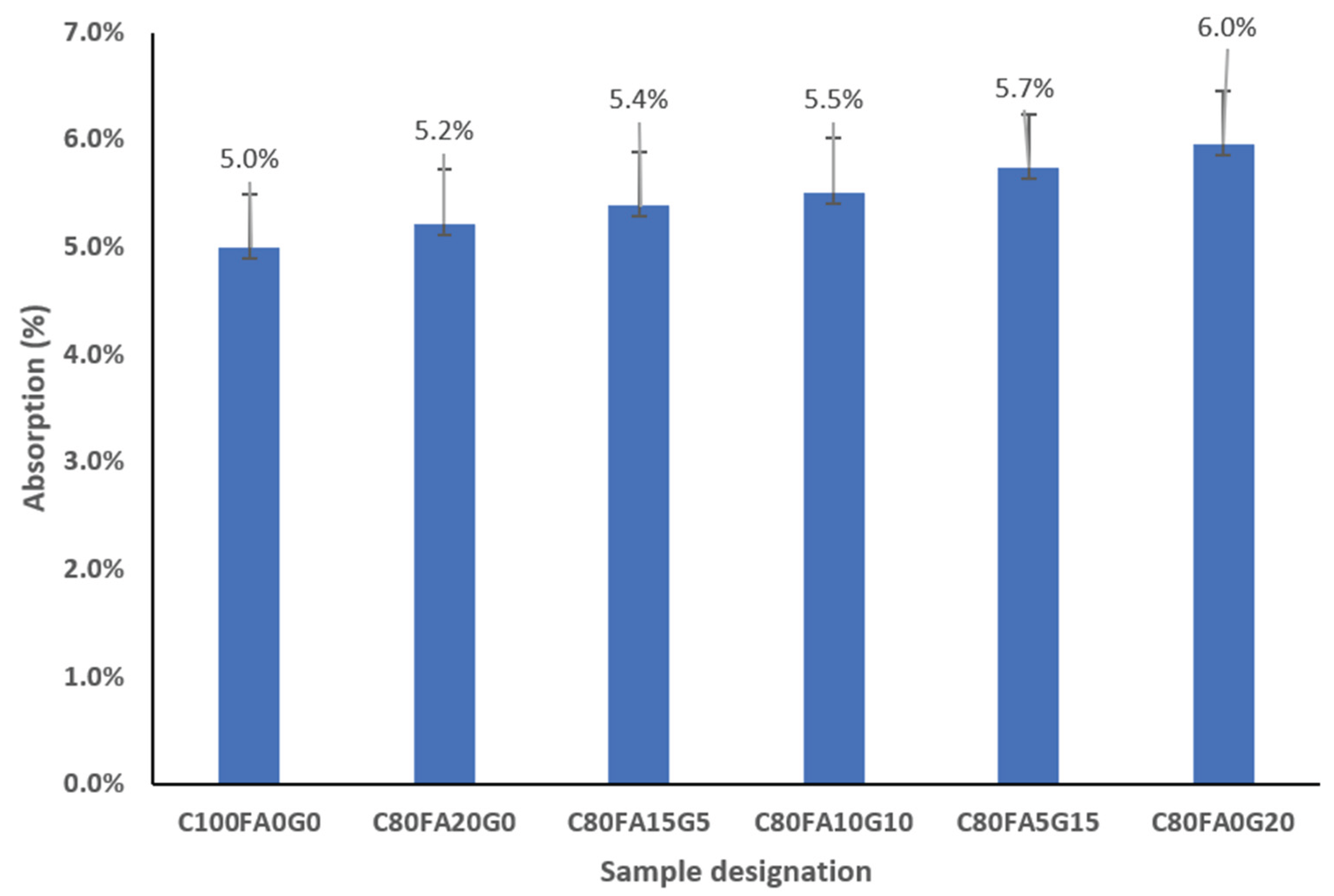

3.2. Absorption of Flyash-Waste Glass Ternary Blended Concrete

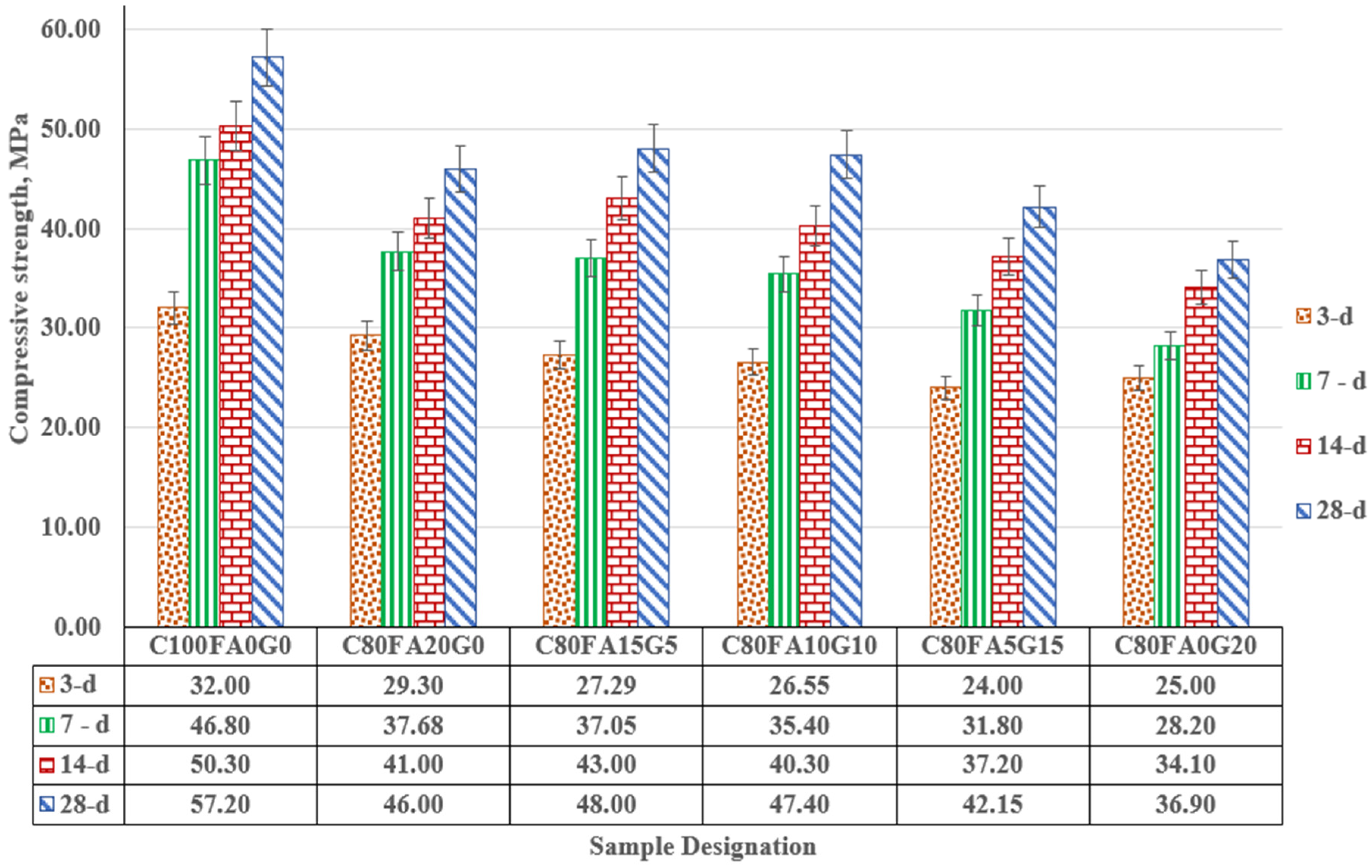

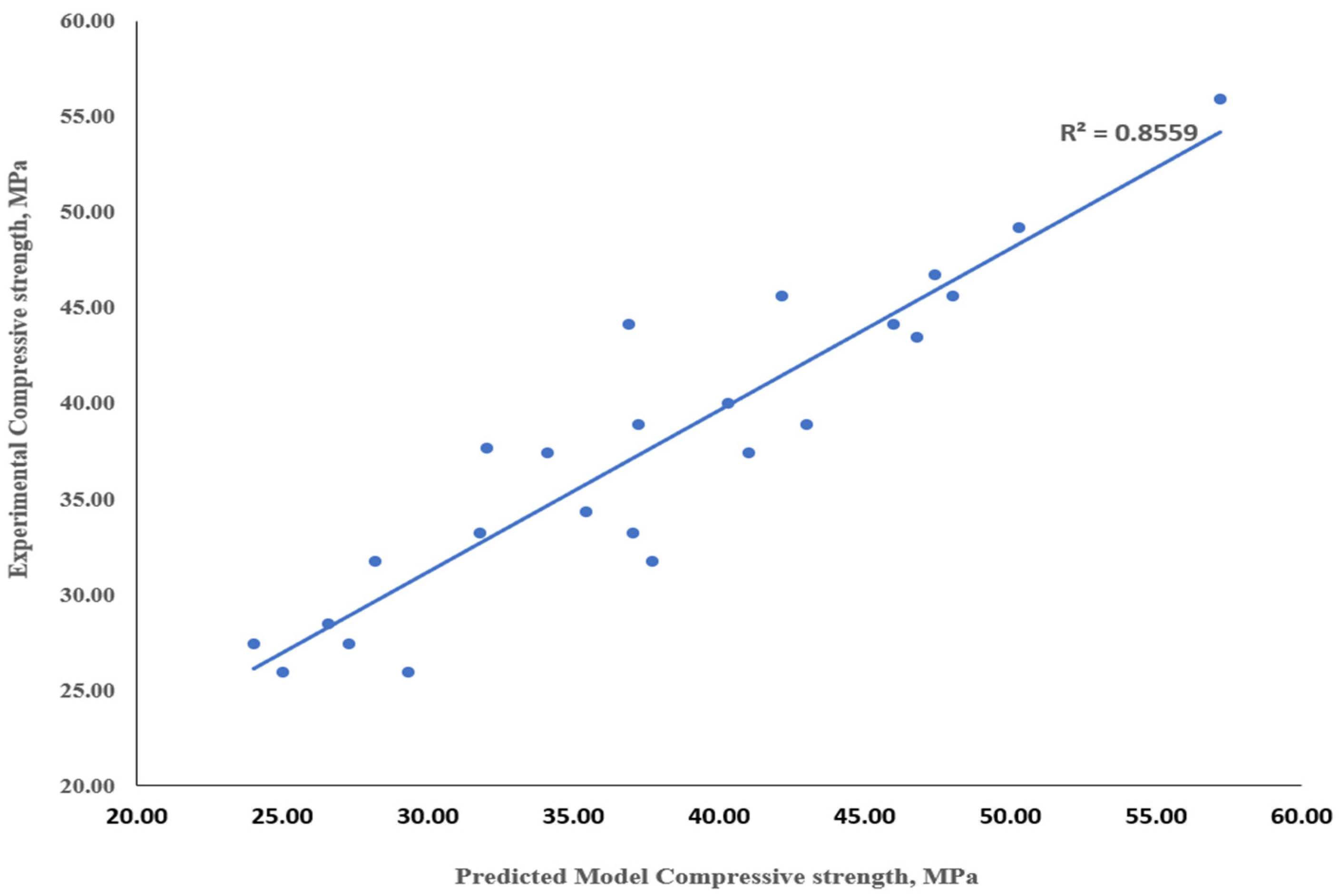

3.3. Compressive Strength of Glass-Flyash Ternary Blended Concrete

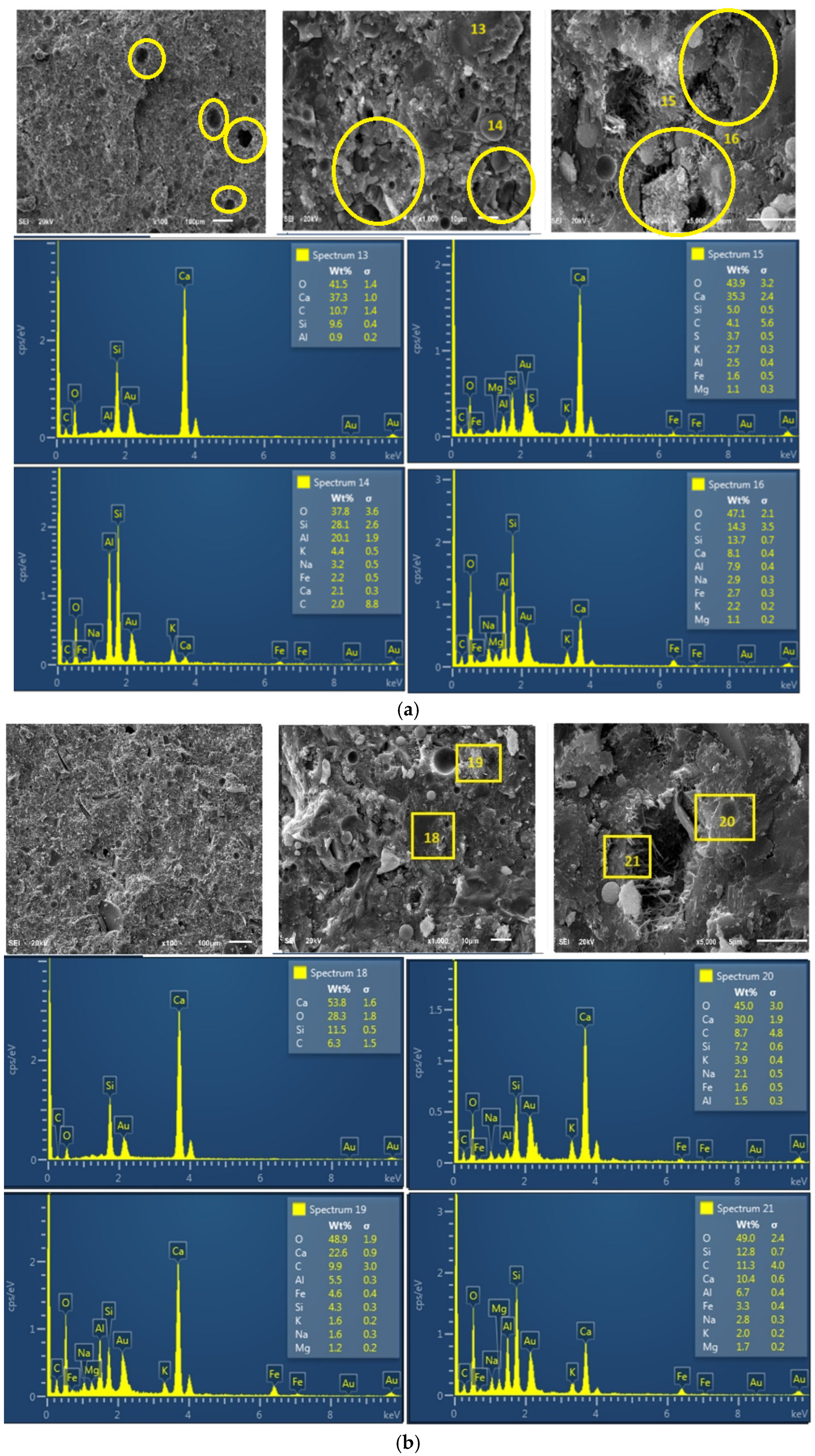

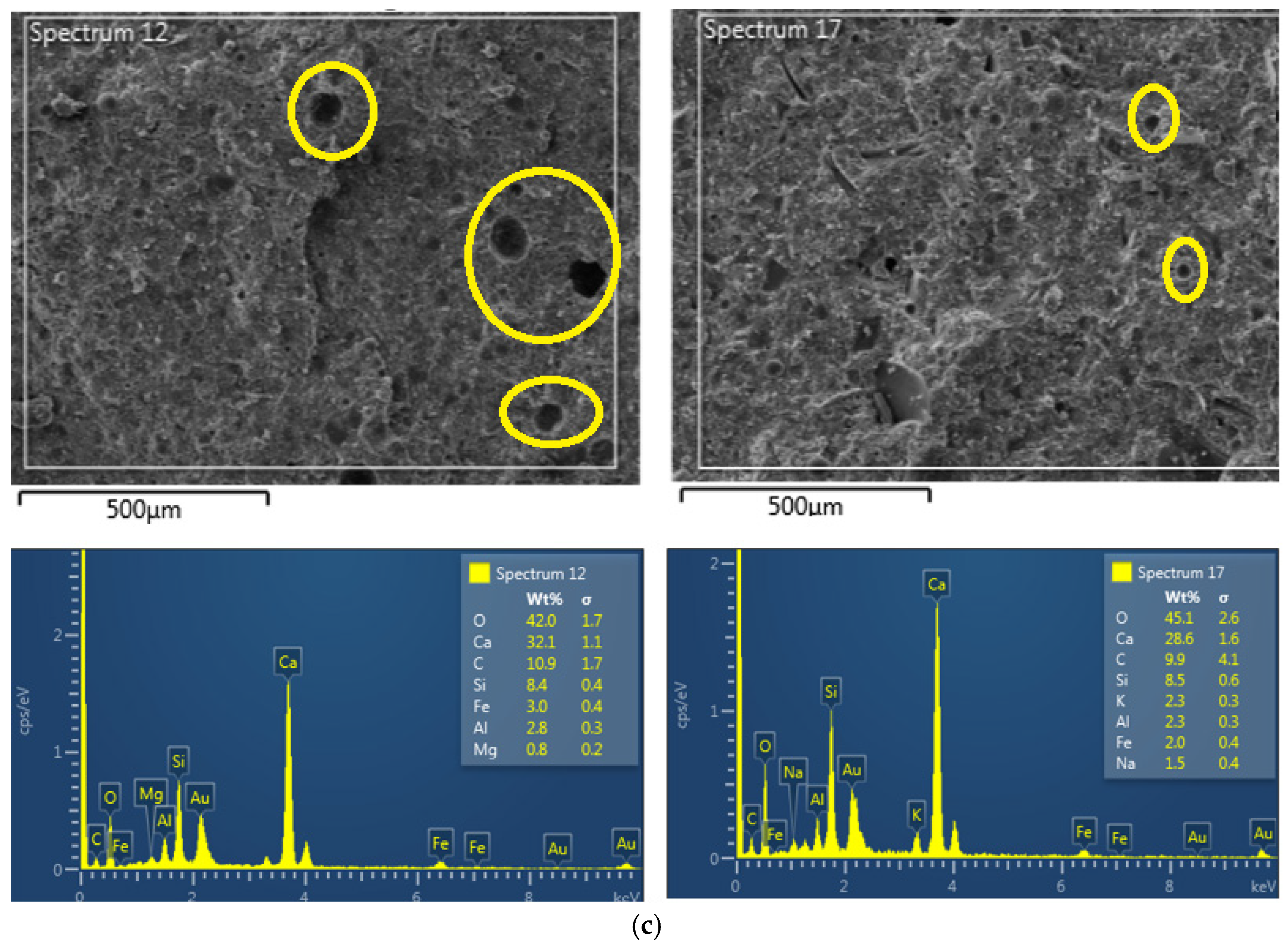

3.4. Microstructural Characteristics and Elemental Analyses of the Products

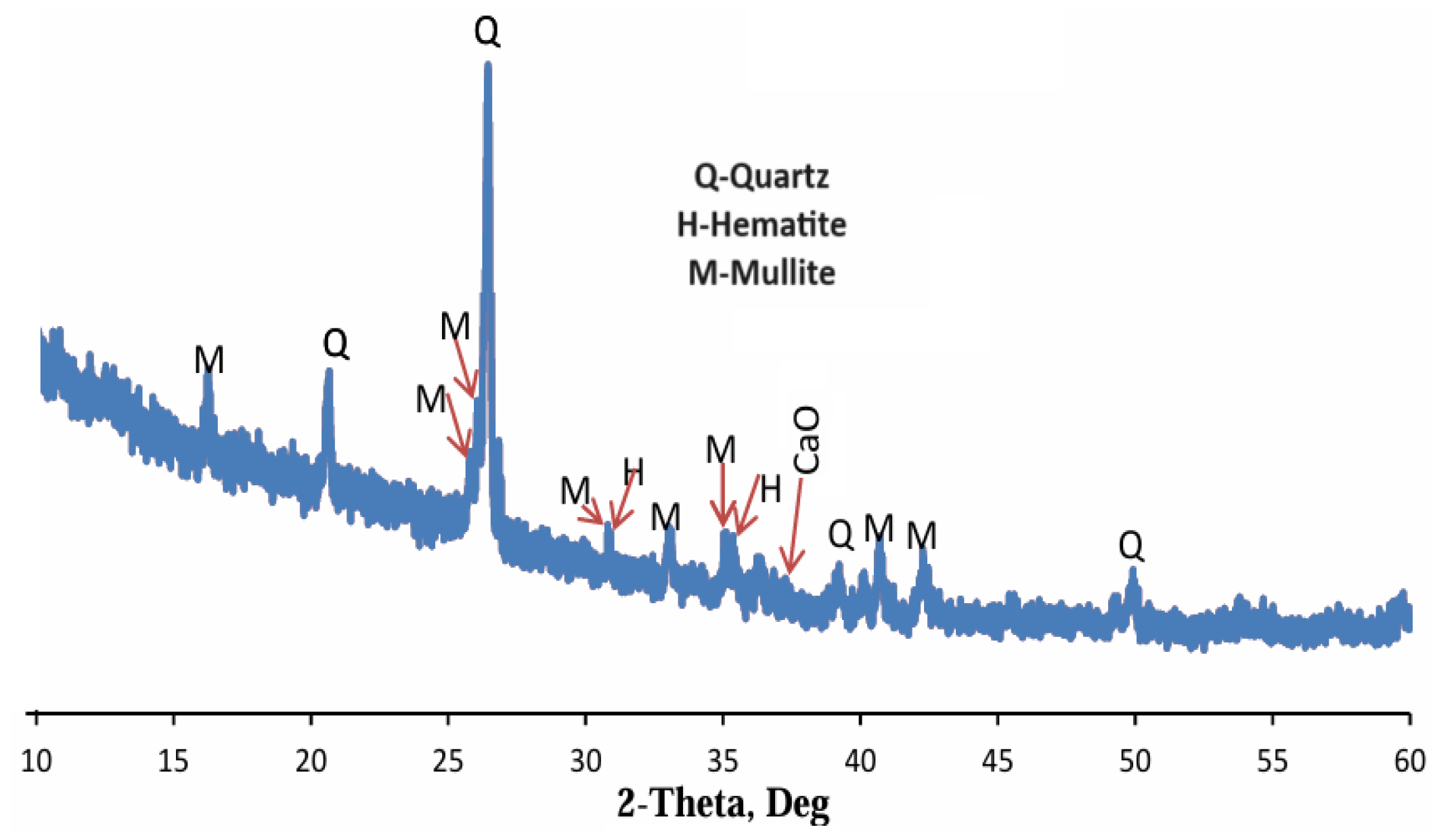

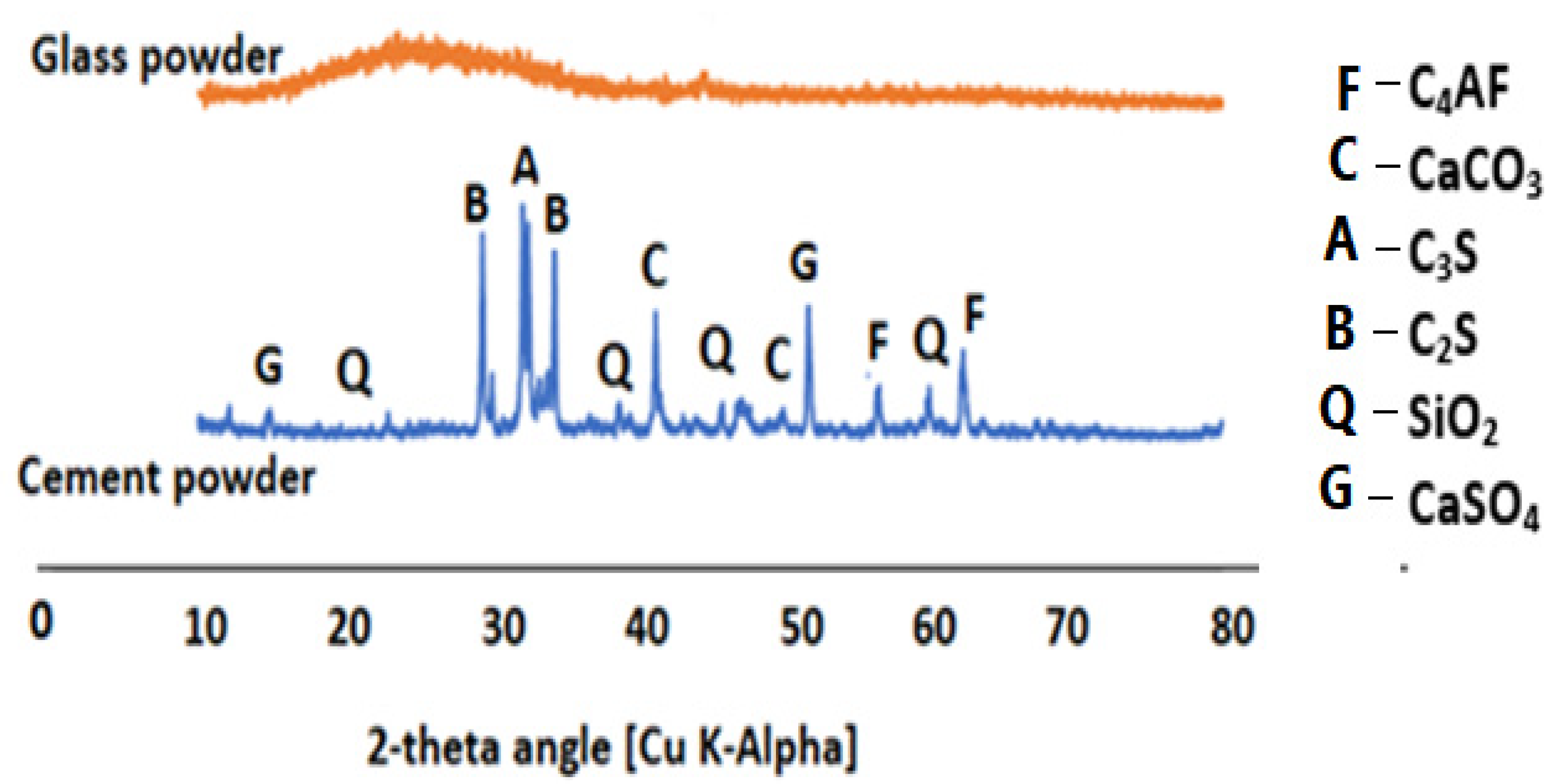

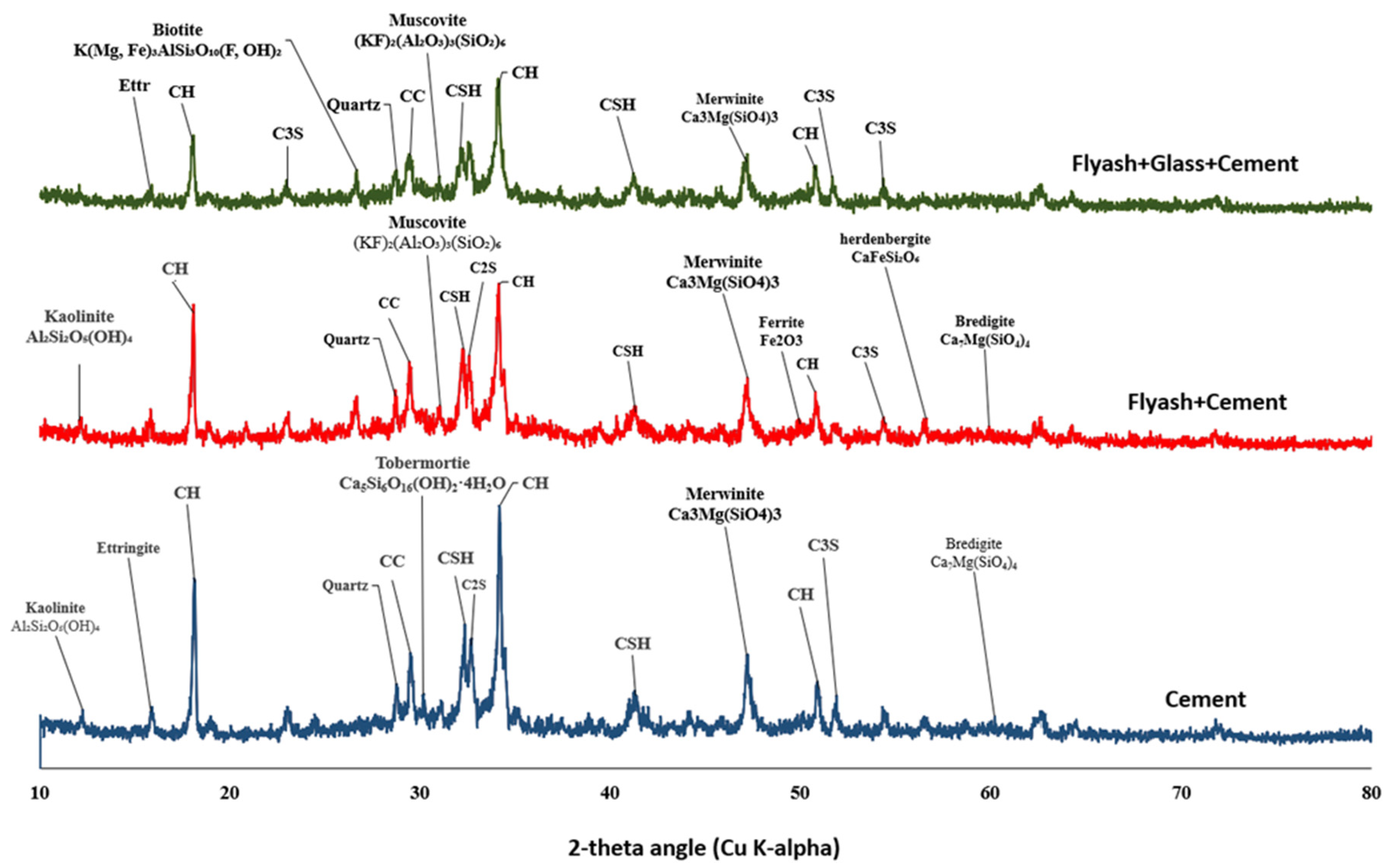

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction of the Flyash-Glass Ternary Blended Binder

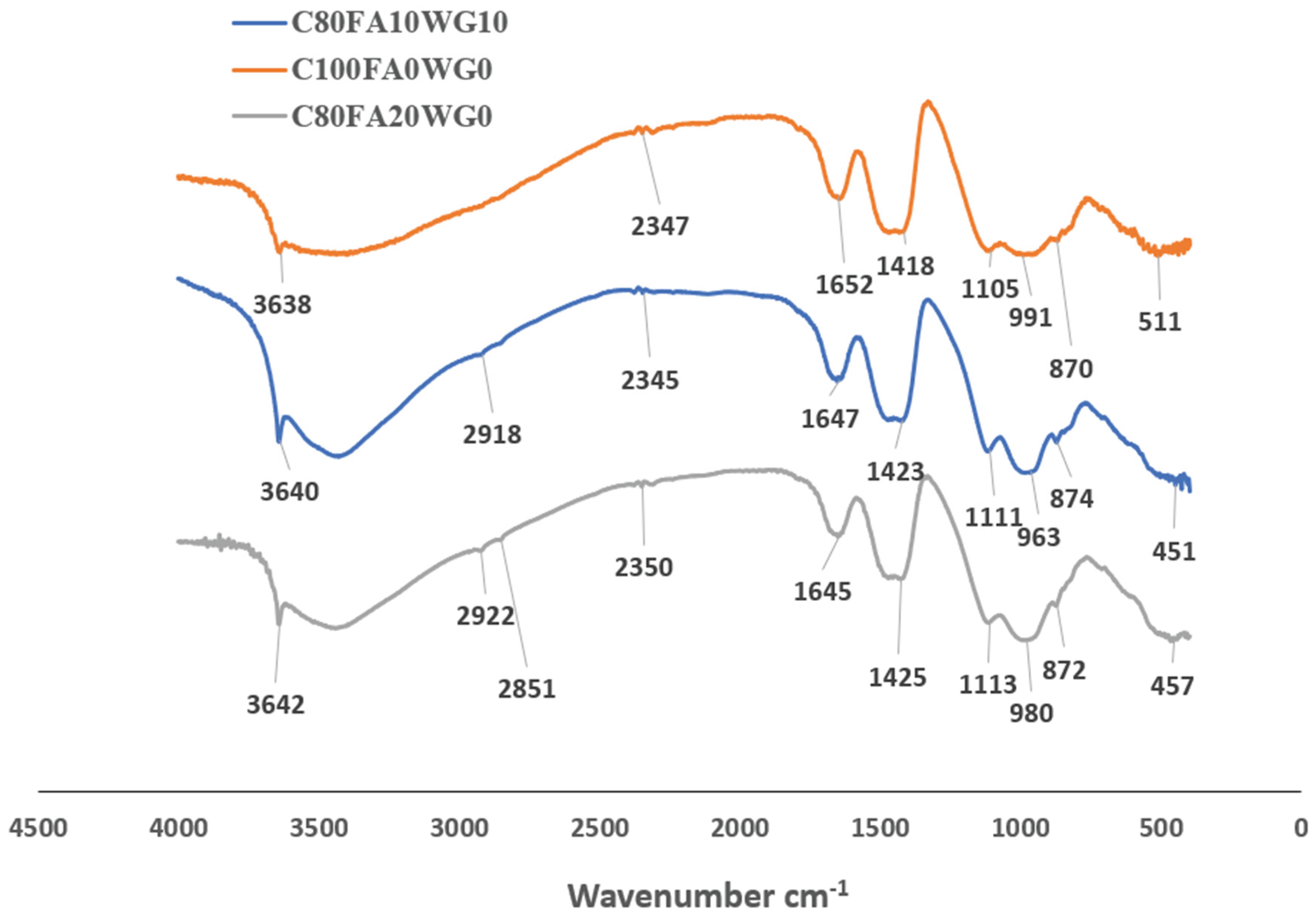

3.6. Bond Characteristics of Binary (FAP-OPC) and Ternary Blended (WGP/FAP/OPC) Binders

4. Conclusions

- The impact WG on FA blended concrete on workability performance of the ternary blended concrete could vary depending on the WG/FA ratios.

- The synergy of WG and FA in concrete production when WG preponderates FA enhanced the porosity and absorption of ternary blended concrete thereby making the use of these additives relevant in the production of porous concrete. However, this had negative impact on the compressive strength of the binder.

- Structural concrete of 28-day strength of 46-48 MPa could be obtained in ternary blended concrete if FA preponderates WG at the minimum percentage composition of 10-15% and 5-10%, respectively as the combined effect of WG and FA had positive correlation on the achievable strength coefficient.

- Ternary blended concrete of balanced WG and FG proportion (C80FA10WG10) had better morphological characteristics due to elimination of micro-pores, and better microstructural density compared to binary blended concrete without WG (C80FA20WG0).

- Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) indicates that silicate reorganization could be better in ternary blended concrete than the binary blended due to more Si/Al, Si/Ca and Ca/Al ratios in C80FA10WG10 in comparison with FA blended concrete (C80FA20G0). Therefore, the use of ternary blending concrete promotes reduction of environmental solid wastes.

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) reveals that the compressive strength is directly related to Si-O-Si asymmetric stretching vibrations. Bending of Si-O-Al band (511 cm-1) and adsorbed water (H-O-H) (1652 cm-1) vibrations within the capillary pores is higher in OPC binder system (C100FA0G0) compared to that of binary (FA-OPC, C80FA20G0) and ternary blended (FA-WG-OPC, C80FA10G10) binder systems.

- X-ray diffractogram (XRD) indicates the amorphous nature of the product achieve through ternary blending depends on WG/FA ratio. Incorporation of WG with FA-OPC blended binder led to the disappearance of hedenbergite phase (CaFeSi2O6) in C80FA10G10 (ternary blended system) despite their presence in C80FA20G0. There was also disappearance of poorly crystalline tobermorite (C-S-H) phase present in OPC binder in ternary binder system due to the formation of more amorphous product.

- Finally, the use of these additives (WG and FA) promotes valorization of solid waste thereby leading to the reduction of volume of landfills. It also promotes clean environment and economic concrete production in the areas where these wastes pose environmental challenges.

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- A.K. Parande, “Role of ingredients for high strength and high-performance concrete – a review,” Advances in Concrete Construction, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 151–162, Jun. 2013, Accessed: Apr. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: .

- H. S. Chore and M. P. Joshi, “Strength evaluation of concrete with fly ash and GGBFS as cement replacing materials,” Advances in concrete construction, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 223–236, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Imrose B. Muhit, Muhammad T. Raihan, and MD. Nuruzzaman, “Determination of mortar strength using stone dust as a partially replaced material for cement and sand. ,” Advances in Concrete Construction An Int’l Journal , vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 249–559, 2014.

- Q. Li, H. Qiao, A. Li, and G. Li, “Performance of waste glass powder as a pozzolanic material in blended cement mortar,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 324, no. February, p. 126531, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 1991; EPA, “Environmental Protection Agency.”.

- N. Tamanna and R. Tuladhar, “Sustainable Use of Recycled Glass Powder as Cement Replacement in Concrete,” The Open Waste Management Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, J. Lu, L. Jiang, and Z. Wang, “Sinterability , microstructure and compressive strength of porous glass- ceramics from metallurgical silicon slag and waste glass,” Ceram Int, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 10079–10084, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Singh and R. Jain, “Use of waste glass in concrete : A review,” J Pharmacogn Phytochem, vol. 5, pp. 96–99, 2018.

- K. H. Tan and H. Du, “Use of waste glass as sand in mortar: Part i - Fresh, mechanical and durability properties,” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 109–117, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, C. S. Poon, and T. C. Ling, “Utilizing recycled cathode ray tube funnel glass sand as river sand replacement in the high-density concrete,” J Clean Prod, vol. 51, pp. 184–190, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. M. S. Islam, M. H. Rahman, and N. Kazi, “Waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement for sustainable concrete practice,” International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 37–44, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. X. Lu and C. S. Poon, “Use of waste glass in alkali activated cement mortar,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 160, pp. 399–407, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Rahma, N. El Naber, and S. I. Ismail, “strength and the workability of concrete Effect of glass powder on the compression strength and the workability of concrete,” Cogent Eng, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Perfilov and V. S. S. D. V. Oreshkin, “Environmentally Safe Mortar and Grouting Solutions with Hollow Glass Microspheres,” in International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Procedia Engineering 150: ICIE 2016, 2016, pp. 1479–1484.

- M. Mirzahosseini and K. A. Riding, “Effect of curing temperature and glass type on the pozzolanic reactivity of glass powder,” Cem Concr Res, vol. 58, pp. 103–111, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Mirzahosseini and K. A. Riding, “Influence of different particle sizes on reactivity of finely ground glass as supplementary cementitious material (SCM),” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 56, pp. 95–105, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Kamali and A. Ghahremaninezhad, “An investigation into the hydration and microstructure of cement pastes modified with glass powders,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 112, pp. 915–924, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Carsana, M. Frassoni, and L. Bertolini, “Comparison of ground waste glass with other supplementary cementitious materials,” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 45, pp. 39–45, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Kawalu, A. Naghizadeh, and J. Mahachi, “The effect of glass waste as an aggregate on the compressive strength and durability of fly ash-based geopolymer mortar,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 361, p. 05007, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Althoey, O. Zaid, A. Majdi, F. Alsharari, S. Alsulamy, and M. M. Arbili, “Effect of fly ash and waste glass powder as a fractional substitute on the performance of natural fibers reinforced concrete,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 14, no. 12, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Yusuf et al., “Performances of the Synergy of Silica Fume and Waste Glass Powder in Ternary Blended Concrete,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 13, 6637, pp. 1–16, 2022.

- B. , Clazer, C. , Garber, C. , Roose, P. , Syrett, and C. Youssef, “Fly ash in Concrete,” 2011.

- Sunil B.M, Manjunatha L.S., Lolitha Ravi, and Subhash C.Yaragal, “Potential use of mine tailings and fly ash in concrete.,” Advances in Concrete Construction, An Int’l Journal , vol. 3, no. 1, 2015.

- Y. Gökşen et al., “Synergistic effect of waste glass powder and fly ash on some properties of mortar and notably suppressing alkali-silica reac-tion,” Revista de la Construccion, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 419–430, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Jurczak and F. Szmatuła, “Evaluation of the possibility of replacing fly ash with glass powder in lower-strength concrete mixes,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Boccaccini, M. Bficker, J. Bossert2, and K. Marszalek, “Glass matrix composites from coal flyash and waste glass,” 1997.

- M. Erol, S. Küçükbayrak, and A. Ersoy-Meriçboyu, “The recycling of the coal fly ash in glass production,” in Journal of Environmental Science and Health - Part A Toxic/Hazardous Substances and Environmental Engineering, Sep. 2006, pp. 1921–1929. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Sunarsih, G. W. Patanti, R. S. Agustin, and K. Rahmawati, “Utilization of Waste Glass and Fly Ash as a Replacement of Material Concrete,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing Ltd., Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Ludwik. Golewski, “Assessing of water absorption on concrete composites containing fly ash up to 30% in regards to structures completely immersed in water,” Case Studies in Construction Materials , vol. 19, no. e02337., 2023.

- S. N. Ghosh and S. K. Handoo, “Infrared and Raman spectral studies in cement and concrete (review),” Cem Concr Res, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 771–782, 1980. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Yusuf, “Bond Characterization in Cementitious Material Binders Using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 3353, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

| Oxide composition | Glass | Flyash | OPC |

| SiO2 | 68.10 | 60.34 | 19.01 |

| Al2O3 | 0.90 | 28.11 | 4.68 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.60 | 3.71 | 3.20 |

| CaO | 14.50 | 1.34 | 66.89 |

| MgO | 1.80 | - | 0.81 |

| Na2O | 12.20 | 0.55 | 0.09 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | - | 0.22 |

| K2O | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.17 |

| P2O5 | - | - | 0.08 |

| SO3 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 3.66 |

| MnO2 | - | - | 0.19 |

| SiO2 + Al2O3 + Fe2O3 | 69.60 | 92.16 | 26.89 |

| SG | 2.48 | 2.38 | 3.14 |

| LOI (%) | 0.80 | 0.50 | 2.80 |

| Surface area (m2/g) | 0.223 | 420 | 0.33 |

| Materials | Specific gravity values |

| Cement | 3.14 |

| Glass | 2.48 |

| Flyash | 2.38 |

| Sand | 2.71 |

| Coarse | 2.54 |

| Elemental ratio | Flyash-OPC Paste C80FA20G0 |

Flyash-Glass-OPC Paste C80FA10G10 |

| Ca/Si | 3.82 | 3.39 |

| Ca/Al | 11.46 | 12.52 |

| Si/Al | 3.00 | 3.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).