1. Introduction

The main target of several studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] is to adopt alternative-binder systems with such advantages as lower cost and environmental friendliness. It is important to use materials that also can improve the mechanical properties of cementitious materials without the need to increase the amount of cement, because of high CO

2 emissions in cement manufacturing and higher cost of product.

Various pozzolanic additives can be used to accelerate cement hydration and to improve the structure, mechanical and other characteristics of hardened cement paste. These pozzolanic additives include silicates or aluminates [

6], which react with calcium hydroxide (CH) and produce calcium silicate hydrates (CSH), calcium aluminosilicate hydrates (CASH) [

7,

8]. Pozzolanic additives also can increase chemical resistance of concrete because less soluble CH leaches during a chemical attack [

9]. Incorporation of industrial waste, such as silica fume, fly ash from coal industry, blast furnace slag, rice husk ash, spent catalytic cracking catalysts (FCCW) from oil refineries, and other types of waste in addition to pozzolanic materials of natural origin, such as volcanic rocks and clays [

10], is even a more significant contribution to scaling up circular economy and addressing the climate change [

11,

12,

13].

More than 800 thousand tonnes of such aluminosilicate waste as FCCW, which is composed of approx. 40% Al

2O

3 and 50% SiO

2, are generated worldwide per year [

14,

15]. Many studies have shown that FCCW improves the properties of different kinds of cement. Therefore, the research on FCCW recovery in cementitious materials is ongoing [

4,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. FCCW has been shown to accelerate cement hydration already in the initial stage [

21,

22], and the replacement of 5%–10% cement with FCCW promotes cement hydration. However, higher levels of FCCW reduce the heat of hydration. FCCW, like other pozzolanic additives, improves mechanical properties of cementitious materials. The results obtained in different studies [

23,

24,

25] show that the maximum strength of the cementitious material was obtained when FCCW content was 10%. Basing on the results of authors [

26] studies 15%–20% of cement can be replaced with FCCW without compromising the performance of cement mortar.

Another aluminosilicate material as metakaolin is made from kaolin fired at temperatures 550–850°C. The right amount of this pozzolanic additive in the mix can effectively improve the physical and mechanical properties of concrete [

27,

28,

29]. Researchers [

30,

31] state that 10%–15% is the optimum content of metakaolin in cement mixes. If a cementitious material contains a high content of metakaolin, its particles agglomerate and the CSH formation process is nearly stagnant during the early period of cement hydration [

32]. The pozzolanic effect of metakaolin on the properties of concrete and mortars depends on its type. It was also found [

33] that high quality metakaolin, which contains more than 90% Al

2O

3·SiO

2, accelerates cement hydration. Conversely, lower grade metakaolin (31%–36% Al

2O

3·SiO

2) slows down cement hydration [

34].

The analysis showed that by using several pozzolanic additives, with each having a different effect on cement hydration mechanism, new positive effects on cement properties can be achieved. Soriano et al. [

35] found that the use of less active fly ash together with FCCW, which has a significantly higher pozzolanic activity, can increase the efficiency of fly ash. Such a binder has a higher strength compared to a material with only one pozzolanic additive. Other authors [

23,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] also confirmed that FCCW is the second pozzolanic additive that can activate fly ash effectively. FCCW was found to accelerate cement hydration in composite binders with fly ash and initiate pozzolanic reactions faster than fly ash used only.

As FCCW has a sufficient activity in the early hydration of cement, this additive may be effective not only in combination with mineral additives of low activity but also with sufficiently active pozzolanic additive as lower grade metakaolin or metakaolin waste, which often retards cement hydration.

The aim of this work is to analyse the impact of aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives (spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst and metakaolin waste from expanded glass industry) on the cement hydration, formation of microstructure of the binder and physical, mechanical properties of hardened cement paste.

2. Materials and Methods

Portland cement CEM I 42.5 R (PC) produced by Heidelberg Cement (Slite, Sweden) was used for the tests. The chemical composition of cement is presented in

Table 1. Mineral composition of cement was as follows: C

3S – 56.6%, C

2S – 16.7%, C

3A – 9.0%, C

4AF – 10.6%. Cement properties: specific surface area of 356 m

2/kg, bulk density 1150 kg/m

3, compressive strength 28.9 MPa at 7 days, 54.6 MPa at 28 days.

Part of cement in the mixtures was replaced with pozzolanic additives: spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst from JSC Orlen Lietuva (Mažeikiai, Lithuania) and metakaolin waste (MK) from expanded glass manufacturer JSC Stikloporas, (Druskininkai, Lithuania). Chemical compositions of the additives are presented in

Table 1. According to chemical composition FCCW and MK are mainly composed of SiO

2 and Al

2O

3, 91.4% and 88.3% respectively.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of PC, FCCW and MK, (mass, %).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of PC, FCCW and MK, (mass, %).

| Material |

SiO2

|

Al2O3

|

Fe2O3

|

MgO |

K2O |

Na2O |

SO3

|

CaO |

Mn2O3

|

TiO2

|

Cl |

LOI |

| PC |

20.4 |

4.00 |

3.60 |

2.40 |

0.90 |

0.20 |

3.10 |

63.2 |

– |

– |

0.05 |

2.15 |

| FCCW |

50.1 |

41.3 |

1.30 |

0.49 |

0.07 |

0.20 |

2.30 |

0.50 |

0.06 |

– |

– |

1.90 |

| MK |

54.3 |

34.0 |

1.14 |

0.51 |

0.80 |

3.26 |

0.15 |

1.94 |

– |

0.53 |

– |

3.37 |

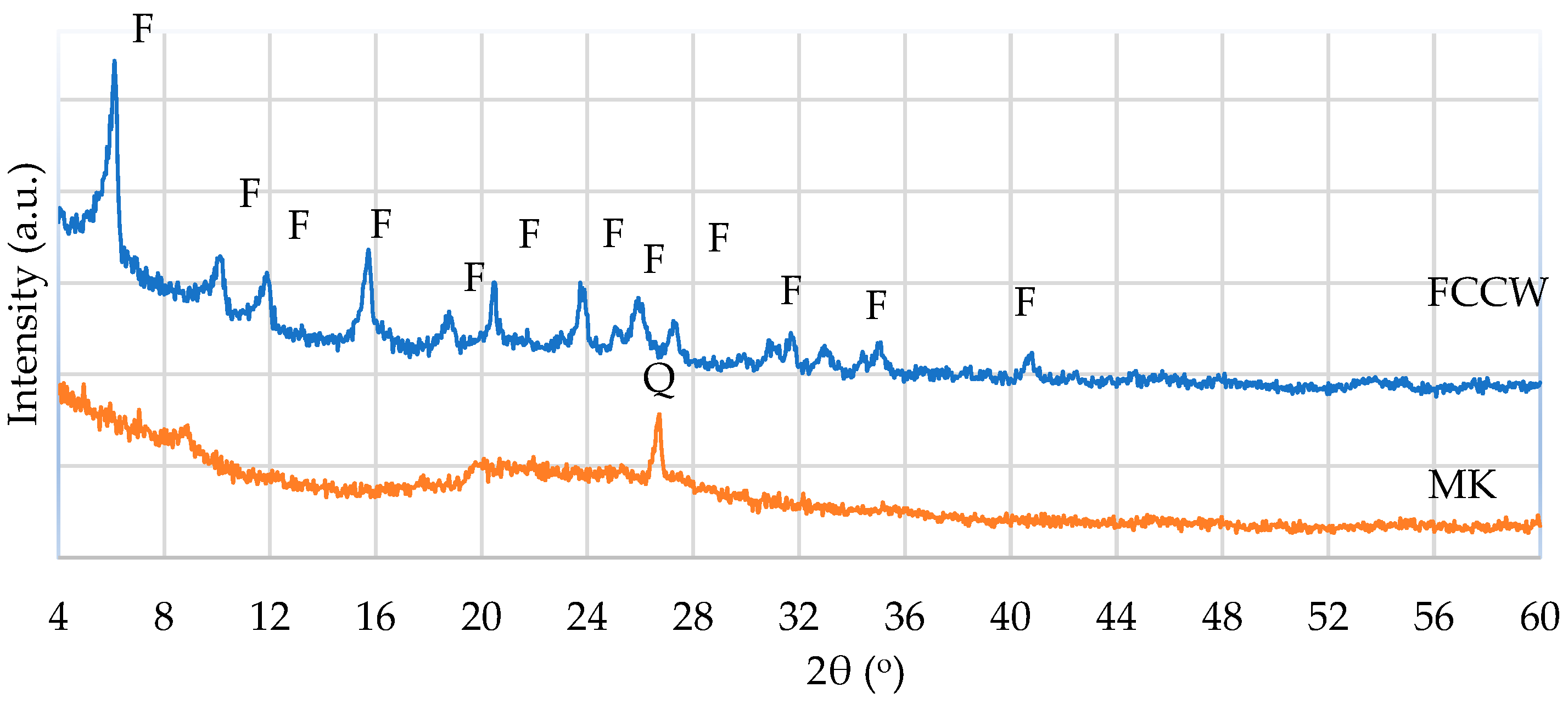

FCCW is Y type zeolite having a crystal structure characteristic of faujasite. MK is an amorphous material with quartz impurities identified in the X-ray image (

Figure 1).

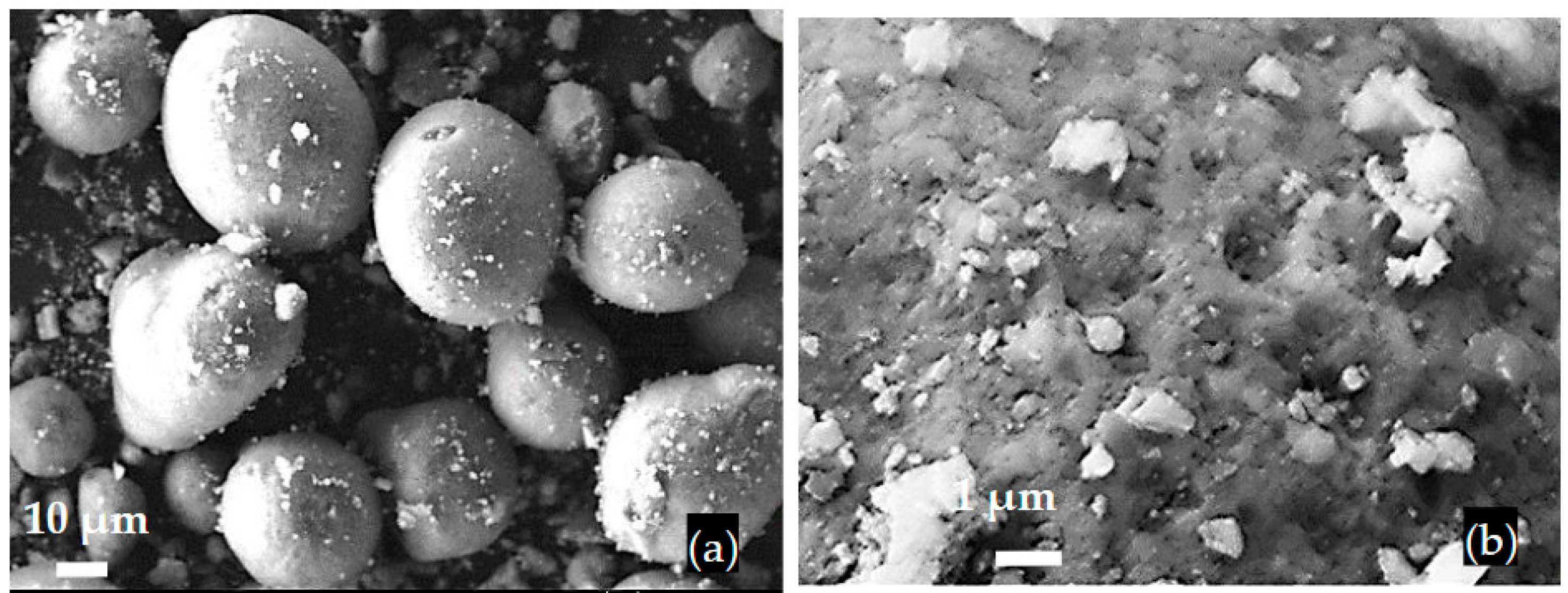

FCCW particles have a sphere shape with a diameter of approximately 40μm and uneven surface (

Figure 2), the bulk density of FCCW is 945kg/m

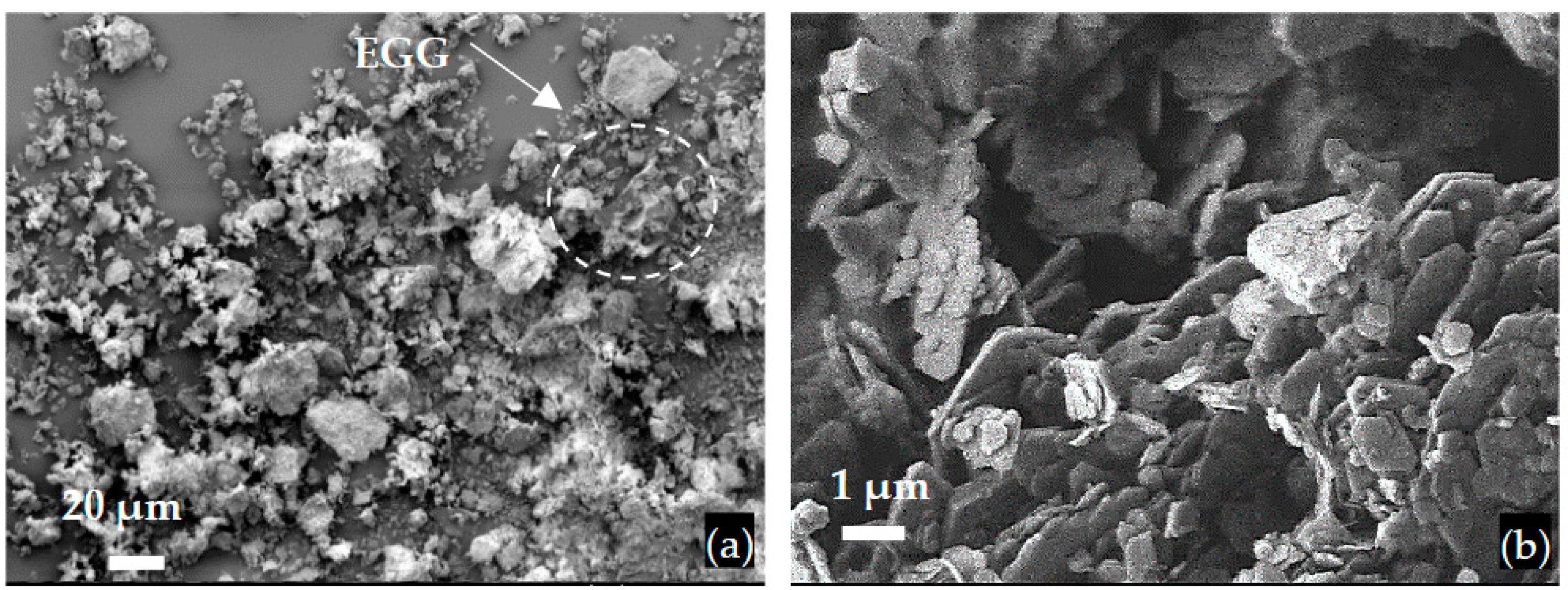

3. MK additive is the mixture of metakaolin and expanded glass scrap (EGG) (

Figure 3), bulk density of MK is 480 kg/m

3.

FCCW and MK have good pozzolanic activity of 1017mg/g and 1148mg/g respectively that was determined according to NF P18-513.

Superplasticizer (SP) Melment F10 produced by German manufacturer BASF (Trostberg, Germany) Construction Polymers was used. It is sulphonated melamine formaldehyde condensate in the form of white powder with the bulk density of 650kg/m3.

Cement pastes with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives and water to binder ratio (W/B) of 0.35 and cement paste of the same composition with 1% of superplasticiser added and W/B of 0.25 were tested (

Table 2). The composite pozzolanic additive consists of FCCW and MK at the ratio 1:1. The designations of cement pastes were as follows: C-0, C-CW, C-MK, C-CMK; cement pastes with superplasticiser CP-0, CP-CW, CP-MK, CP-CMK (

Table 2). Control specimens C-0 and CP-0 contained no pozzolanic additives.

Cement paste components were mixed in a Hobart mixer for 2 min. After adding the required amount of water, the mixture was mixed for 2 more minutes. Afterwards the mixture was poured into 160 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm forms and compacted on the vibration table for 10 s. After 24 hours the demoulded specimens were cured till 28 days in water at 20±1°C.

The qualitative analysis of phase composition of the materials (XRD) was done on X-ray diffractometer DRON-7 (Bourevestnik, Saint Petersburg, Russia). A graphite monochromator was used to obtain the X-ray Cu Kα spectrum (λ = 0,1541837 nm). Test parameters: anode voltage 30 kV; anode current 12 mA; diffraction angle 2θ interval from 5° to 60°, detector step 0.02°; intensity measuring span 2s. The phases were decoded from the X-ray diffraction patterns using ICDD diffraction database. Quantitative changes in minerals on the X-ray diffraction patterns were assessed by the height of the main diffraction peak of the mineral. Anatase was used as an internal standard for the tests at the ratio 9:1 substance/anatase.

Thermogravimetric and differential thermal analysis (TG, DTG) was conducted by the equipment Linseis STA PT-1600 (Selb, Germany). A platinum crucible with a specimen of 60-70 mg was heated in air up to 1000 °C at the heating rate 10°C/min.

Portlandite (CH) content in hardened cement paste was calculated from the mass loss recorded on the TG curve in CH decomposition temperature range 430°C–550°C according to Wang et al. [

41] as follows:

Where 74 and 18 are molar mass of CH and H2O respectively.

The microstructure of concrete specimens and mineral admixtures was tested with the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) device JEOL JSM-7600F (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The following electron microscopy parameters were used: power 10 kV and 20kV, distance to specimen surface from 6 mm to 10 mm. Before testing, the splitting surface was coated with electrically conductive thin layer of gold by evaporating the gold electrode in the vacuum using the instrument QUORUMQ150R ES (Quorum Technologies Ltd., Lewes, UK).

The density of the specimens was calculated from the specimen’s mass (0.01 g accuracy) and volume determined from the specimen’s dimensions (0.01 mm accuracy). The compressive strength after 7 and 28 days was measured by hydraulic press H200KU (Tinius Olsen, Redhill, UK) according to EN 1015-11:2007 requirements.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure characteristics

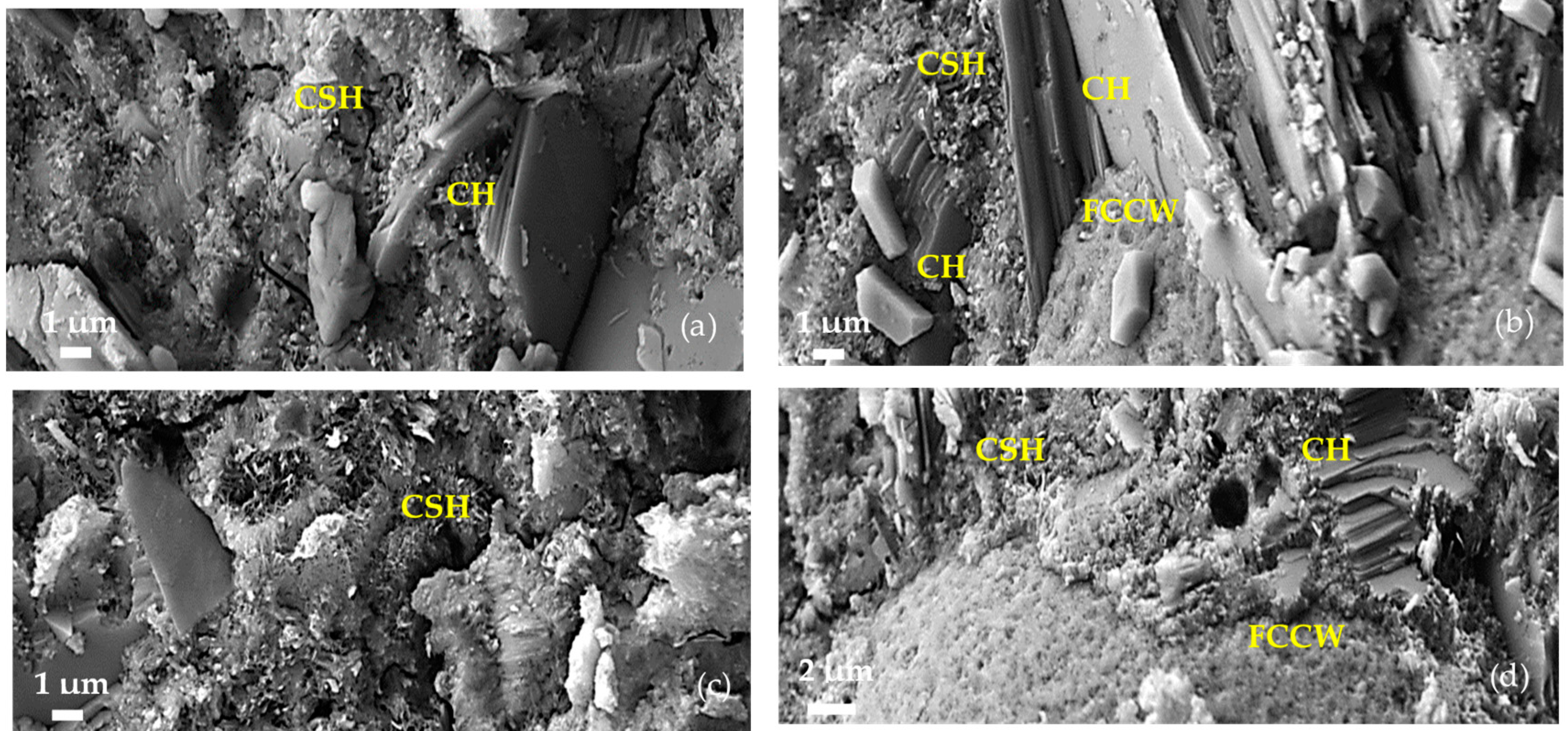

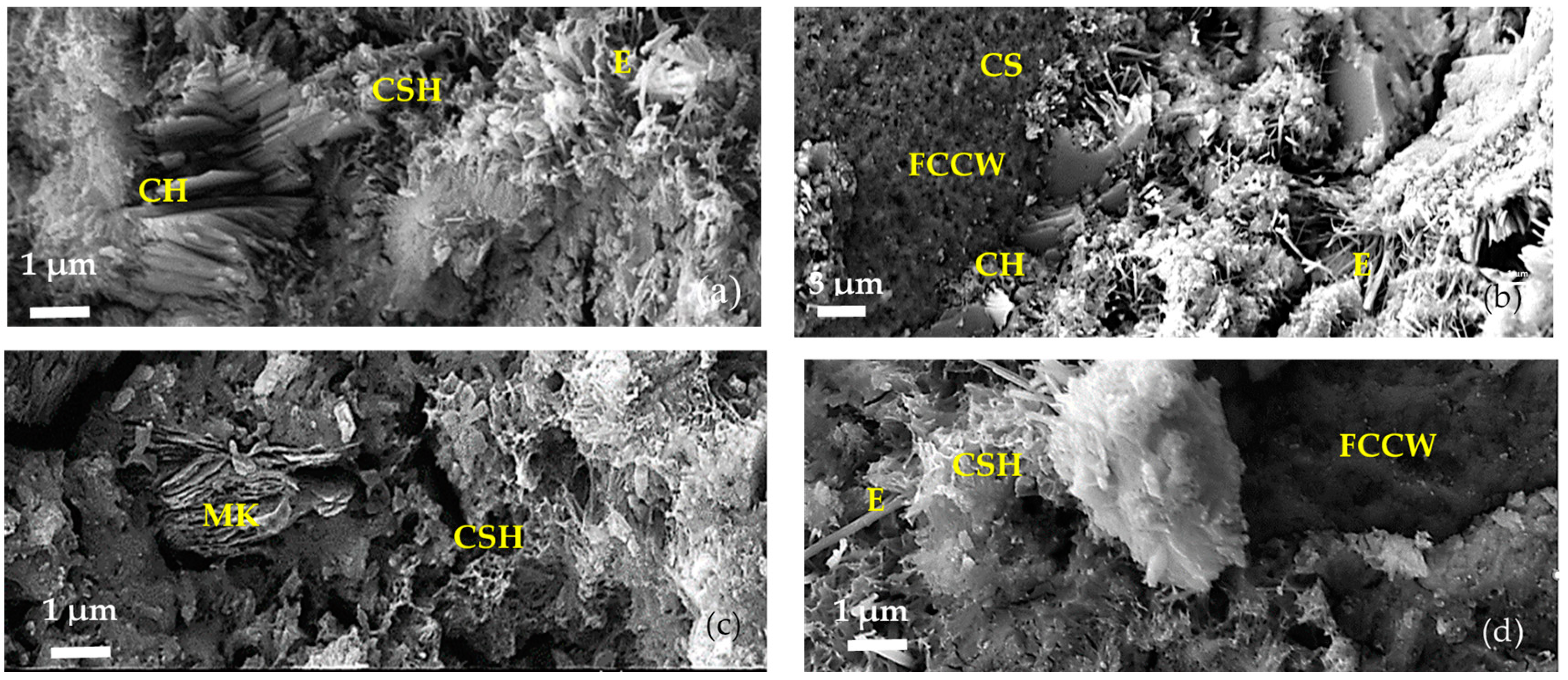

SEM images of the microstructure of hardened cement paste of C composition at 7 days are presented in

Figure 4.

The microstructure of the control specimen (C-0,

Figure 4a) clearly shows the following hydration products: clusters of platy crystals of portlandite (CH), single needle-shaped ettringite crystalline hydrates (E) and small particles of amorphous CSH. In C-CW composition (

Figure 4b), there is a relatively abundant formation of plate-shaped portlandite positioned perpendicularly to the surface of spent catalyst particle, and fine CSH interspersed between portlandite crystals. A relatively large amount of amorphous CSH phase is observed in compositions containing MK (C-MK,

Figure 4c and C-CMK,

Figure 4d). No clusters of portlandite crystals were observed on FCCW particles in compositions with a composite additive (

Figure 4d), presumably due to the activating (pozzolanic) effect of MK.

After 28 days the microstructure of the specimens of all compositions became denser as a result of cement hydration. In compositions with FCCW, the quantity and size of portlandite clusters on FCCW surface increased (

Figure 5b). In composition with a composite additive, the surface of FCCW particles is covered with a dense CSH layer with smaller size inclusions of hydrated portlandite crystals (

Figure 5d). Presumably, the size and amount of portlandite crystals decreases due to the pozzolanic reactions, during which CH is depleted by active MK, which is fine and well distributed in the entire cementitious matrix. As a result, more CSH and CASH is formed. It has been shown [

42] that the effect of pozzolanic material commonly occurs between 7 and 28 days when portlandite is consumed in the reaction.

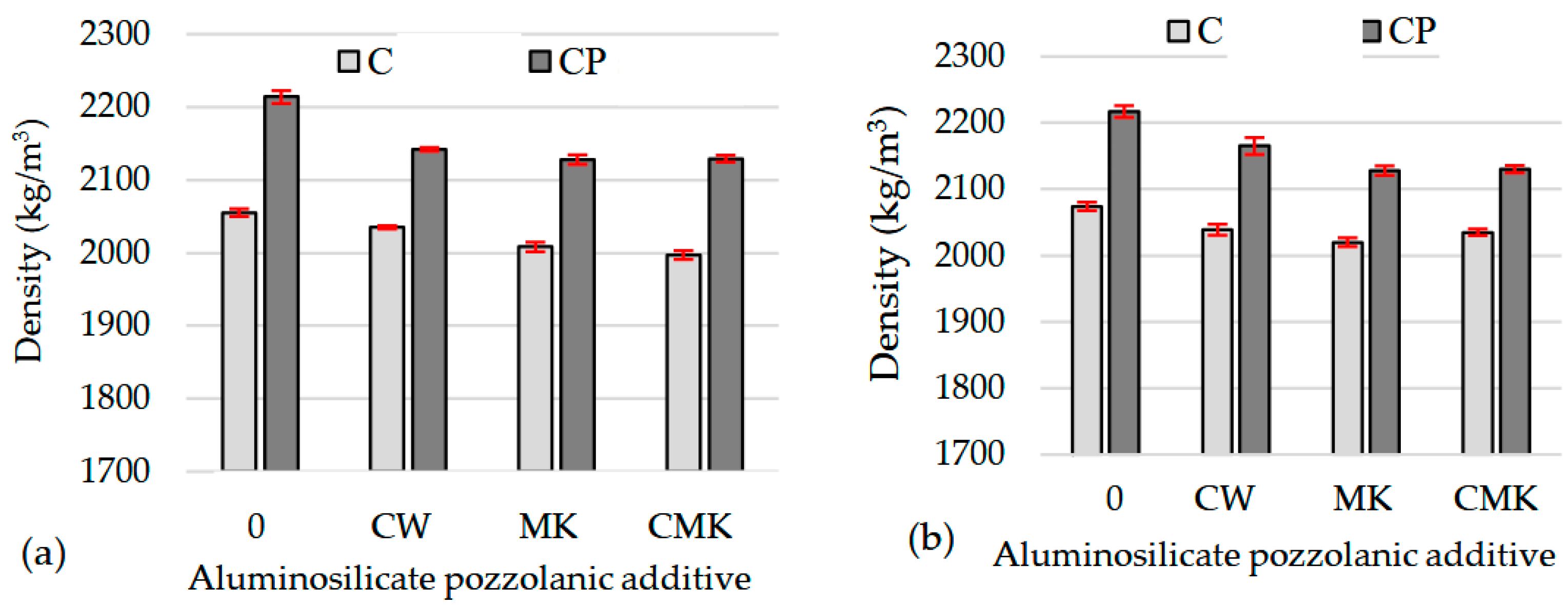

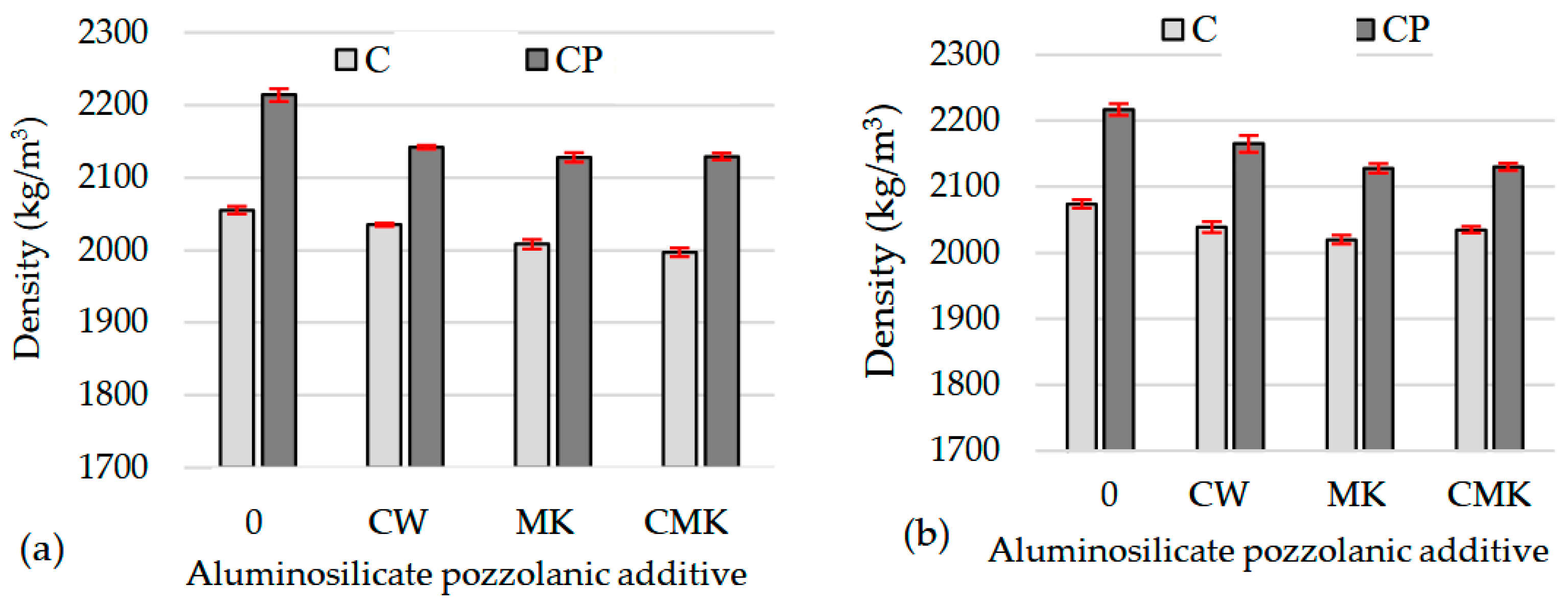

However, this has no effect on the density of hardened cement paste with additives after 28 days of curing (

Figure 6b) compared to the density after 7 days (

Figure 6a): in some compositions, it remains practically unchanged, while in other it increases only by up to 2%.

Figure 5.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste specimens of C composition after 28 days: a) – C-0, b) – C-CW, c) – C-MK, d) – C-CMK; CH – portlandite, E – ettringite, CSH – calcium silicate hydrate.

Figure 5.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste specimens of C composition after 28 days: a) – C-0, b) – C-CW, c) – C-MK, d) – C-CMK; CH – portlandite, E – ettringite, CSH – calcium silicate hydrate.

At 7 and at 28 days, the density of hardened specimens containing superplasticiser (CP composition) (

Figure 6) is from 5% to 7% higher than the density of specimens of C composition due to reduced W/B ratio. The density of control specimens with a superplasticiser was 2-4% higher than the density of specimens with pozzolanic additives due to the lower density of pozzolanic aluminosilicate additives compared to cement density and the formation of hydrated crystals of lower density.

Figure 6.

Density of hardened cement paste specimens: after 7 days (a) and after 28 days (b).

Figure 6.

Density of hardened cement paste specimens: after 7 days (a) and after 28 days (b).

Similar microstructure features of the specimens of C composition were also determined in specimens CP at 28 days (

Figure 7): There are evident formations of clusters of portlandite crystals around the spherical FCCW particles in specimen CP-CW (

Figure 7a). The interfacial zone between cement matrix and FCCW particles is very dense in the compositions with composite additive and portlandite crystals are not observed in this zone (

Figure 7b).

3.2. Analysis of hydration products (XRD and TG, DTG)

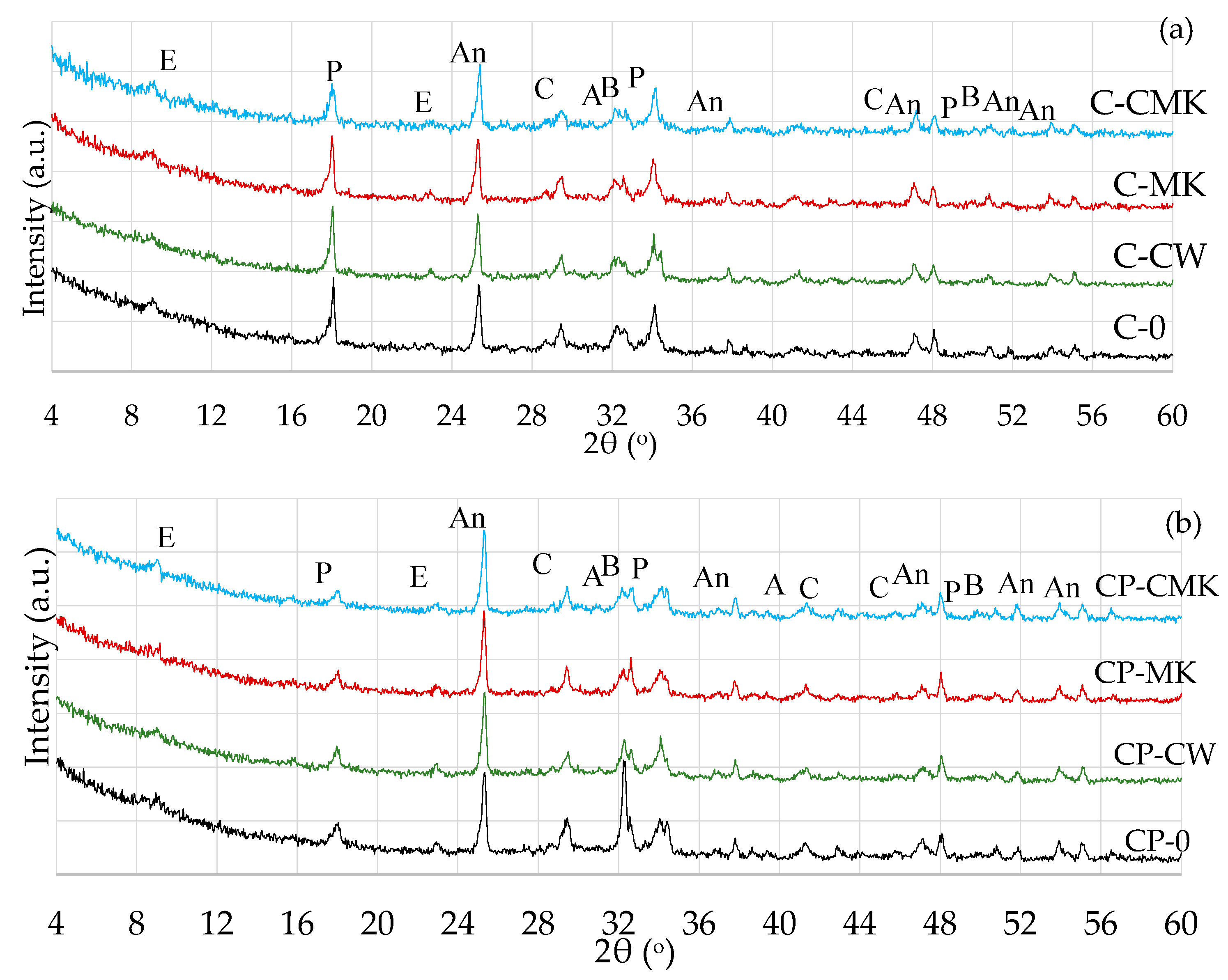

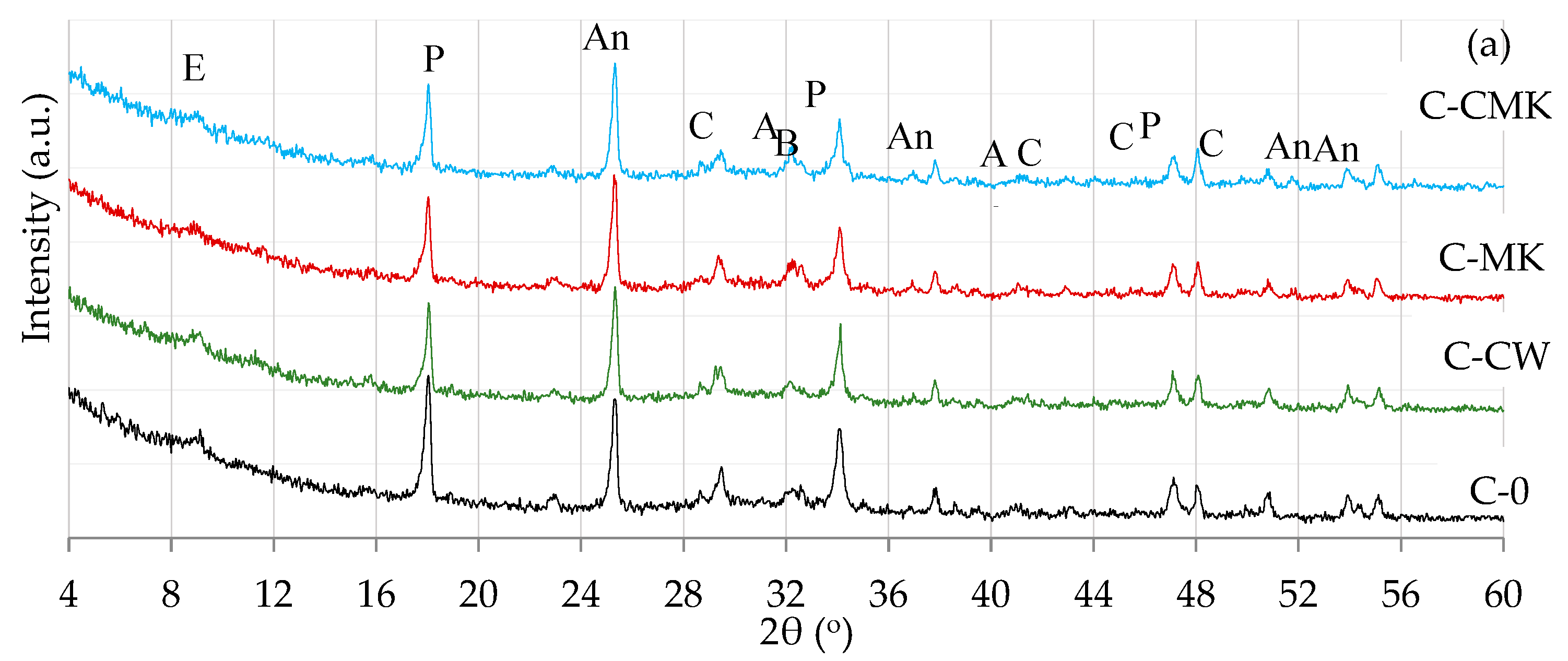

The effect of aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives on the phase composition of Portland cement hydration products was determined by X-ray and thermal analysis methods. XRD test results (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) showed the presence of the same compounds, namely ettringite (Ca

6Al

2(SO

4)

3(OH)

12·26(H

2O), portlandite (Ca(OH)

2) and calcite (CaCO

3), in hardened cement paste of all compositions after 7 and 28 days of curing.

CSH and CASH, the key products of cement hydration, were not identified in any X-ray diffraction curves irrespective of cement paste composition and curing time (7 and 28 days) because of their amorphous nature [

43,

44,

45]. The unreacted cement minerals alite and belite were also identified in the X-ray diffraction curves, as well as anatase, the external standard used for the preparation of the test mixtures. Anatase was used for the calibration of cement mixture curves in order to compare the intensities of newly formed components in different compositions.

It should be noted that the lower peak intensity of portlandite was obtained in compositions with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) (card No. 44-1481, the main peak at 34.1

o) compared to control specimens. It can be explained by the reduced cement content in the mixture as the compositions with pozzolanic additives contained 9% less cement than control compositions.

The comparison of portlandite peak intensities in compositions with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives only showed that the highest intensity of portlandite in all cases was recorded in the compositions with spent catalyst (C-CW and CP-CW) and the lowest peak intensity was observed in the compositions with a composite pozzolanic additive (C-CMK and CP-CMK). The obtained results could suppose that FCCW not only accelerates early cement hydration [

46], but also encourages the formation of hydration products (portlandite) in later cementitious material curing periods. Uniformly distributed fine MK particles in the cementitious material react with portlandite during the ozzolanic reaction to produce products such as CSH, CAH and CASH.

It should be noted that the relative intensity of portlandite peaks in CP compositions with a superplasticiser is much lower than in C compositions (

Figure 8a and

Figure 9a). According to [

43], this is caused by the retarding effect of the superplasticiser on cement hydration and subsequently lower amounts of hydration products. A lower W/B ratio also has an effect on the degree of hydration in CP compositions. Similar findings were confirmed by M. Pereira et al. [

45], who observed lower intensity of portlandite peaks in cement compositions with a lower W/B ratio.

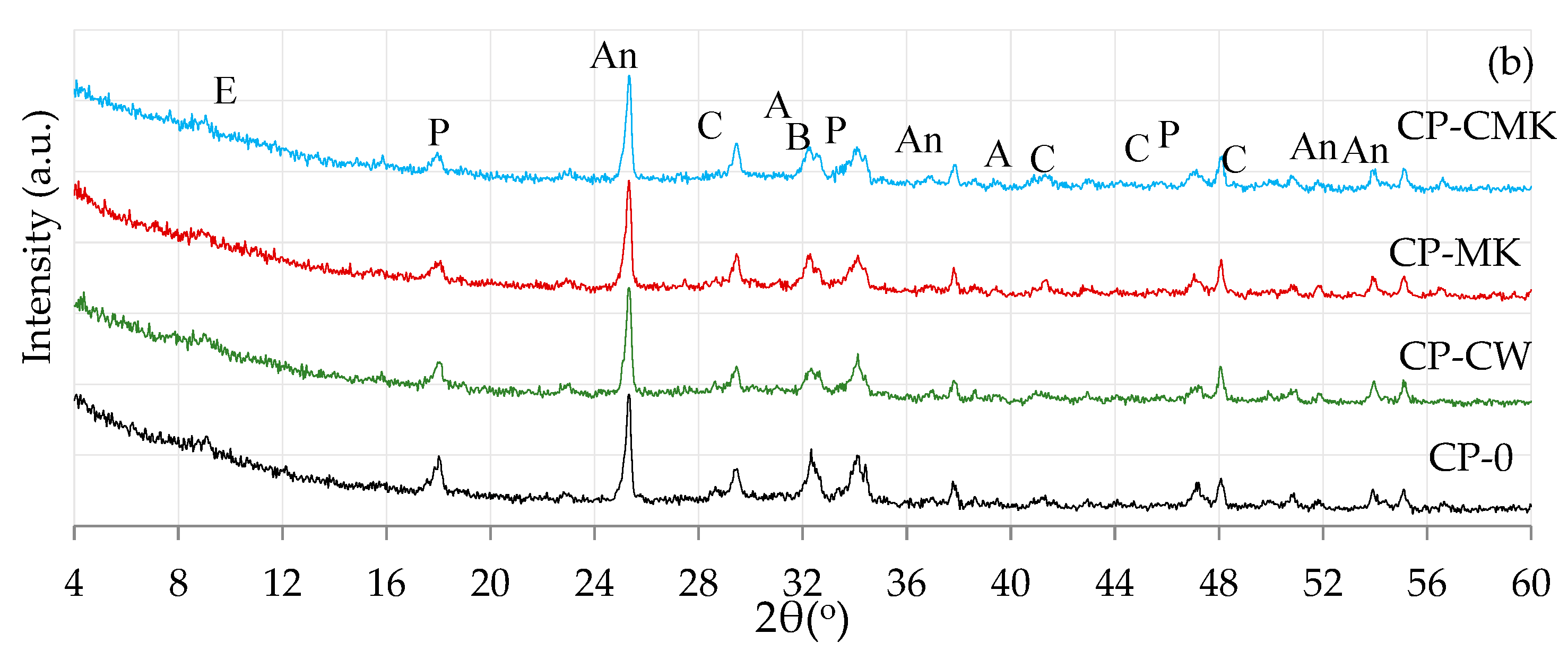

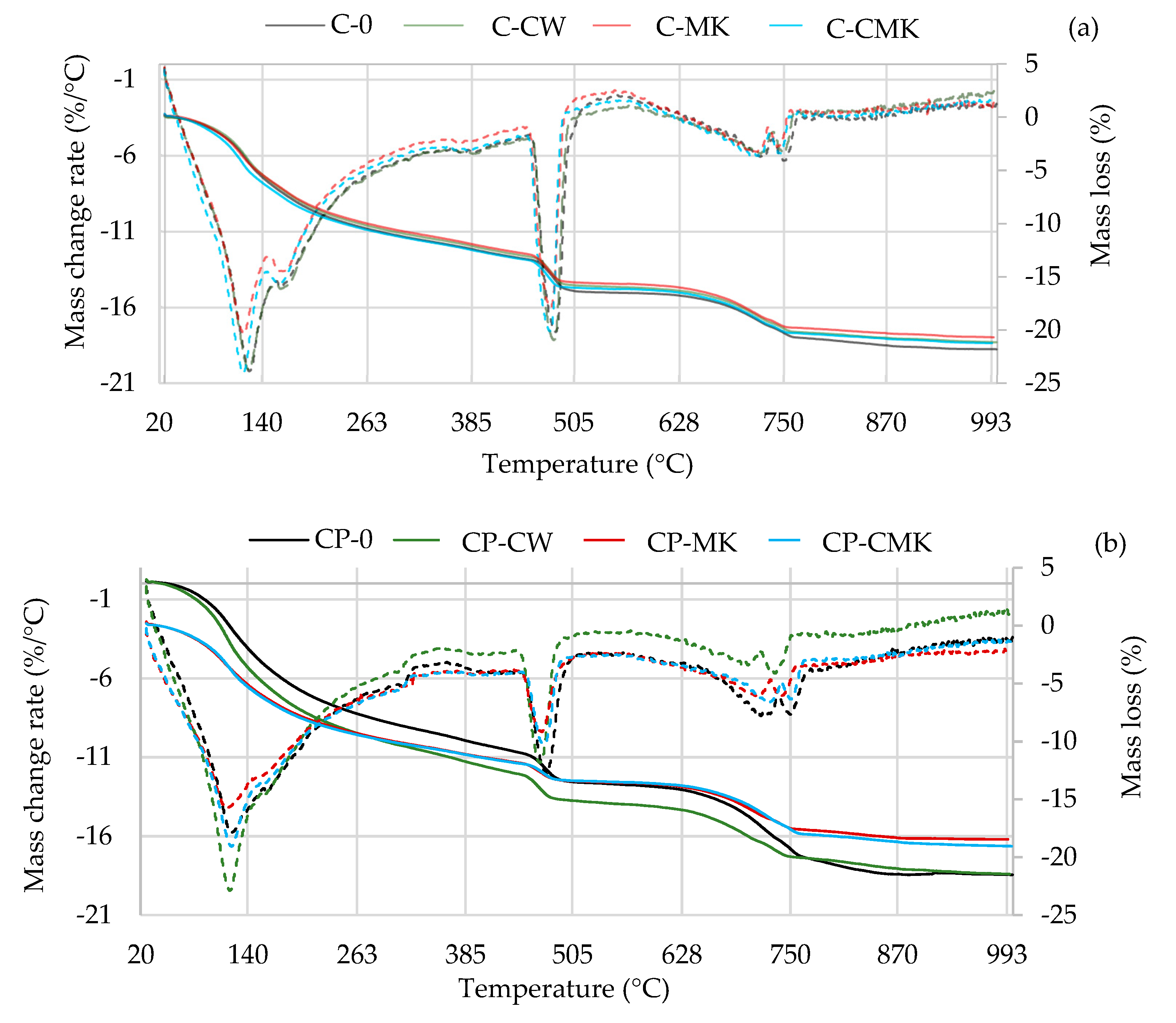

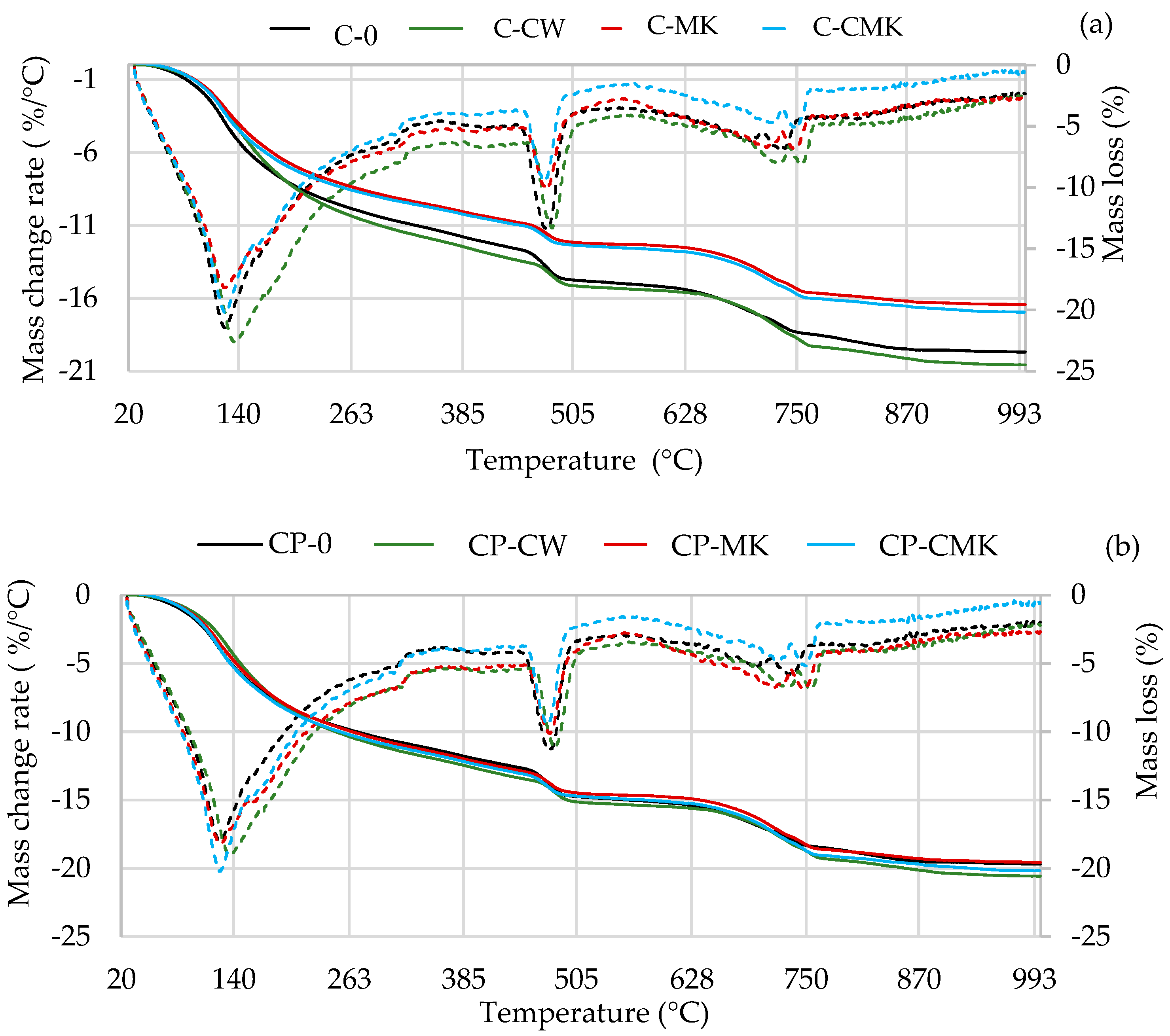

Thermogravimetric analysis is a more precise technique than XRD analysis to determine the amount of portlandite formed in hardened cement paste. TG-DTG curves of cement specimens after 7 and 28 days of curing are presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

TG–DTG curves reveal 3 endothermic peaks: the first one (30°C–300°C) is related to the processes that occur in this temperature range, namely evolution of free water (at 30°C–105°C), dehydration of CSH (at 115°C–120°C), ettringite (at 100°C–180°C), CAH and CASH (at 180°C–240°C); the second peak at 430°C~550°C is related to portlandite dissolution; and the third peak at 650°C~750°C is related to decarbonisation process [

47,

48,

49,

50].

Table 3 shows portlandite amount evaluation results in the temperature range 450°C–520°C according to Equation 1. Obtained results correlate with XRD analysis results (the intensity of CH peaks in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). At 7 days, portlandite content in compositions with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives was 9.5%–13.3%, while in C and CP compositions its was 9.3%–20.3% lower in comparison to the control composition. At 28 days it was 50% and 20% lower respectively.

The highest portlandite content among compositions containing aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives was observed in compositions with FCCW. The lowest amount of portlandite formed in compositions with MK and with a composite pozzolanic additive. Apparently, MK promotes pozzolanic reactions and more portlandite is consumed for the formation of CSH and CASH.

Table 3.

CH content in hydrated cement compositions (mass, %) and mass loss in the temperature range 110oC–350oC.

Table 3.

CH content in hydrated cement compositions (mass, %) and mass loss in the temperature range 110oC–350oC.

| Composition |

The amount of portlandite, wt. % |

Mass loss in the temperature range 110oC–350oC, % |

| After 7 days |

After 28 days |

After 7 days |

After 28 days |

| C-0 |

12.68 |

13.90 |

9.10 |

11.00 |

| C-CW |

11.47 |

6.96 |

8.98 |

9.58 |

| C-MK |

11.20 |

6.74 |

8.46 |

9.19 |

| C-CMK |

10.99 |

6.87 |

8.47 |

9.29 |

| CP-0 |

7.60 |

8.72 |

8.44 |

8.71 |

| CP-CW |

6.89 |

7.18 |

12.78 |

10.02 |

| CP-MK |

6.36 |

6.74 |

10.96 |

9.19 |

| CP-CMK |

6.06 |

6.85 |

11.96 |

9.20 |

The results of the TG tests show that at 110°C–350°C (

Table 3) the mass loss in compositions with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives plus superplasticiser was significantly higher compared to the control composition. These compositions contained 9% less cement and that could be the reason for the formation of more CSH and CASH phases during the pozzolanic reaction. However, it should be noted that ettringite also decomposes at this temperature, and ettringite content can be higher in control specimens without the superplasticiser, as can be seen in the X-ray diffraction curves (

Figure 8a and

Figure 9a).

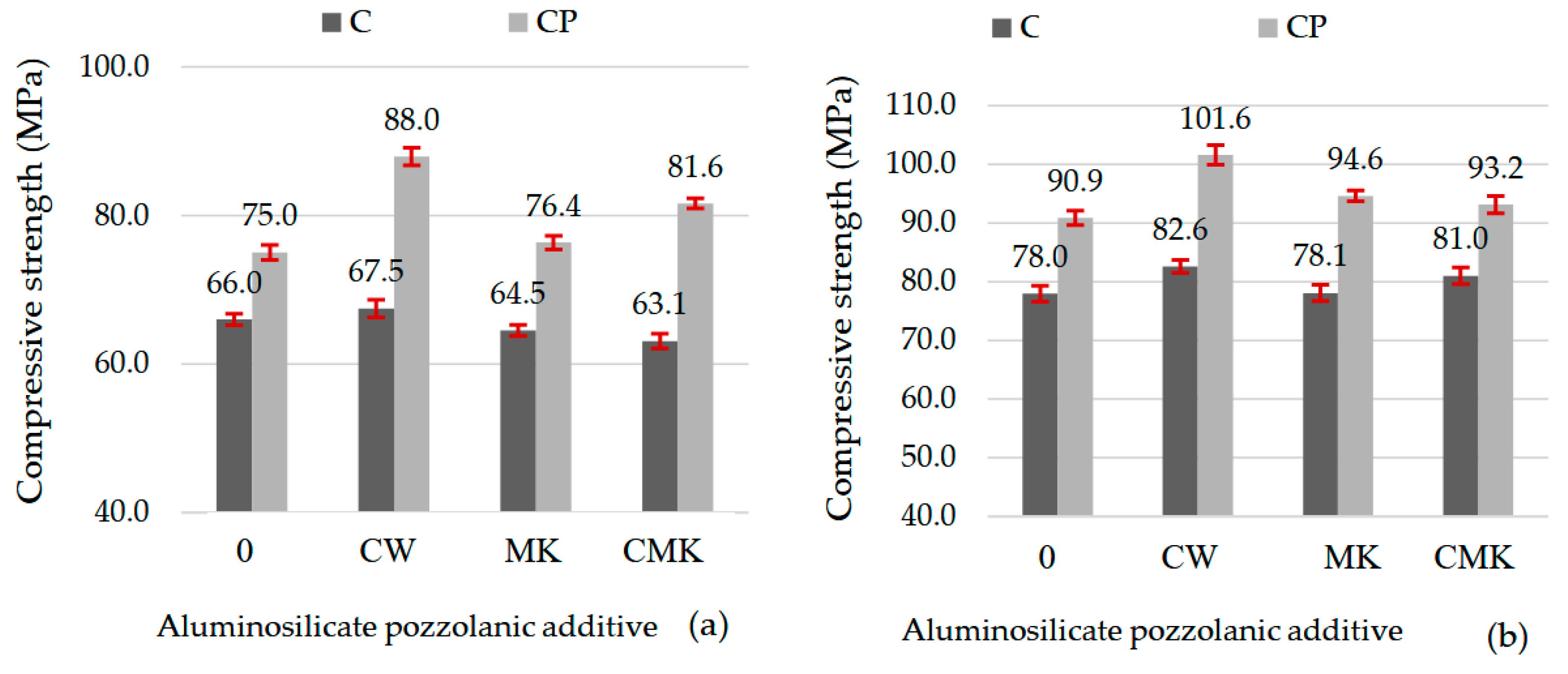

3.3. Effect of aluminosilicate additives on mechanical properties

Figure 12 illustrates the compressive strength results of hardened cement paste. These results indicate that the tested aluminosilicate additives are active pozzolanic materials. When a part of cement was replaced with these materials, the compressive strength at 28 days remained the same or increased in comparison to control specimen. Similar results of mechanical properties were reported by other authors: studies with the addition of FCCW in cementitious materials by authors [

21,

25] studies with the addition of metakaolin waste by Pundienė et al. [

51].

The use of a superplasticiser (CP composition) made it possible to produce a denser hardened cement paste, with approximately 15% higher compressive strength of the control specimen at both 7 and 28 days (

Figure 12), compared to the C composition control specimens. The compressive strength of the CP composition with aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives increased up to 15–30 %.

It should be also noted that all specimens with FCCW (

Figure 12) had the highest compressive strengths at 7 and 28 days in comparison to the specimens modified with MK and composite additive (FCCW+MK). There was little difference in the compressive strength of specimens with MK and with composite additive. There is a strong correlation of these results with the mass losses (

Table 3) in CSH and CASH decomposition temperature range 110

oC–350

oC. The highest mass loss was recorded in the composition containing FCCW and superplasticiser (CP-CW). At 7 days the strength of C composition specimens was similar and at 28 days the strength of control specimens was even lower than the strength of the specimens with the pozzolanic additives. It can be attributed to higher levels of ettringite formed in control specimens, as can be seen in the X-ray diffraction curves (

Figure 8a and

Figure 9a).

Figure 12.

Compressive strength of hardened cement pastes after 7 days (a) and 28 days (b).

Figure 12.

Compressive strength of hardened cement pastes after 7 days (a) and 28 days (b).

In summary, the results of the study show that FCCW used to replace part of cement in the mixture adds to the formation of a larger number of platy portlandite crystals. The effect of FCCW on cement hydration is related to its water absorption properties and pozzolanic activity. FCCW particles absorb part of the water during the binder mixing with water. Reactions during the early hydration period accelerate due to the local decrease in W/B ratio in the cement paste. Once the material has set, the water accumulated in FCCW particles is used for the further hydration process. The formation of portlandite crystal hydrates was observed around the catalyst particles up to 28 days. Therefore, structured elements are formed locally in the structure of hardened cement paste. The specimens modified with FCCW have higher compressive strength than the specimens made of cement only due to the higher degree of hydration and pozzolanic activity of FCCW.

Compositions with a composite pozzolanic additive have half content of FCCW compared to compositions containing only FCCW additive; therefore, the effect of FCCW on cement hydration is lower. A change in the structure of the interfacial area between the cement matrix and FCCW particles was observed with a prevalence of CSH phase with portlandite inclusions because the active additive MK consumes portlandite for the production of CSH and CASH. This effect was more obvious in compositions with a superplasticiser.

Conclusions

Intensive formation of clusters of portlandite crystals on the spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst particles even after 28 days was observed in compositions containing 9% of this additive. Such phenomenon can be explained by a large specific surface area of spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst particle, which retains water required for hydration. In the case of composite pozzolanic additive (4.5% spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst particle and 4.5% metakaolin waste from expanded glass industry) in compositions without a superplasticizer, portlandite crystals formed on the catalyst particles are of smaller size, different orientation, and in this composition lower content of portlandite was determined. In compositions with a superplasticizer, portlandite is more rapidly consumed for the formation of CSH and CASH due to the pozzolanic effect of metakaolin and is no longer identified on the spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst particles in SEM images, whereas XRD and DTG results show a reduced amount of portlandite in the entire cementitious paste.

The microstructure of specimens made of the mixture with the composite pozzolanic additive and the superplasticizer have the highest density, but it is about 3% lower than the density of control specimens because the density of aluminosilicate pozzolanic additives is lower than cement density and presumably the density of hydrated crystals formed is also lower. The compressive strength of the specimens modified with pozzolanic additives after 28 days of curing increased up to 6% and 12% when only the spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst was used and up to 2.5% and 4% when a composite pozzolanic additive was used, respectively for compositions with and without superplasticizer, although the cement content of the mixtures was 9% lower.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A. and J.M.; methodology, R.B. and A.K.; validation, V.A. and J.M.; formal analysis, V.A. and J.M.; investigation, D.S. and R.B.; resources, V.A.; data curation, V.A. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, V.A. and A.K.; visualization, V.A.; supervision, V.A. and R.S.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The equipment and infrastructure of Civil Engineering Scientific Research Center of Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (VILNIUS TECH) was employed for investigations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mohsen, A.; Kohail, M.; Alharbi, Y. R.; Abadel, A. A.; Soliman, A. M.; Ramadan, M. Bio-mechanical efficacy for slag/fly ash-based geopolymer mingled with mesoporous NiO. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02283. [CrossRef]

- Naqi, A.; Jang, J. G. Recent progress in green cement technology utilizing low-carbon emission fuels and raw materials: A review. Sustain. 2019, 11, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Imbabi, M. S.; Carrigan, C.; McKenna, S. Trends and developments in green cement and concrete technology. Int. J. Sustain. Built. Environ. 2012, 1, 194–216. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Pavia, S. Potential of spent fluid cracking catalyst (FCC) waste for low-carbon cement production. Effect of treatments to enhance reactivity. Cement, 2023, 14, 100081. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, A.; Chow, C.L.; Feo, L.; Penna, R.; Lau, D. Green Concrete: By-Products Utilization and Advanced Approaches. Sustain. 2019, 11, 5145. [CrossRef]

- Baltakys, K.; Siauciunas, R. Influence of gypsum additive on the gyrolite formation process. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40(3), 376–383. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.F.W. Cement chemistry. Second edition, London, UK, 1997; ISBN: 0727725920.

- Kurdowski, W. Chemia cementu i betonu. (english: Chemistry of cement and concrete). Wydawnictwo. Polski Cement. Kraków a Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 2010; ISBN: 978-83-91315-24-8.

- Bumanis, G.; Bajare, D.; Locs, J.; Korjakins, A. Alkali-silica reactivity of foam glass granules in structure of lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 274–281. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, K.; Ma, C. Portland cement concrete. Chapter 3. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2021, 59–204. [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.G.; Snellings, R.; Bernal, S. A. Supplementary cementitious materials: new sources, characterization, and performance insights. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 257–273. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Khan, M.N.N.; Karim, M. R.; Kaish, A.B.M.A.; Zain, M.F.M. Physical and chemical contributions of Rice Husk Ash on the properties of mortar, Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 128, 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Inan Sezer, G. Compressive strength and sulfate resistance of limestone and/or silica fume mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 26, 613–618. [CrossRef]

- Antonovič, V.; Boris, R.; Malaiškienė, J.; Kizinievič, V.; Stonys, R. Effect of milled fluidised bed cracking catalyst waste on hydration of calcium aluminate cement and formation of binder structure. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Pacewska, B.; Nowacka, M.; Aleknevičius, M.; Antonovič, V. Early hydration of calcium aluminate cement blended with spent FCC catalyst at two temperatures. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 844–850. [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; He, T.; Wang, M.; Shi, C.; Xu, R.; Yang, R. The effect of spent petroleum catalyst powders on the multiple properties in blended cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117–203. [CrossRef]

- Malaiskiene J.; Costa, C.; Baneviciene, V.; Antonovic, V.; Vaiciene, M. The effect of nano SiO2 and spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst on cement hydration and physical mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 124281. [CrossRef]

- Vaičiukynienė, D.; Mikelionienė A.; Kantautas A.; Radzevičius A.; Bajare D. The influence of zeolitic by-product containing ammonium ions on properties of hardened cement paste. Minerals. 2021; 11(2), 123. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Wong, T. N.; Qian, S. Mechanism and design of fluid catalytic cracking ash-blended cementitious composites for high performance printing. Additive Manuf. 2023, 61, 103286. [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; He, T.; Wang, M.; Shi, C.; Xu, R.; Yang, R. The effect of spent petroleum catalyst powders on the multiple properties in blended cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117203. [CrossRef]

- Pacewska, B.; Bukowska, M.; Wilińska, I.; Swat, M. Modification of the properties of concrete by a new pozzolan – a waste catalyst from the catalytic process in a fluidized bed. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32(1),145–152. [CrossRef]

- Paya, J.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M. V.; Velázquez, S. Evaluation of the pozzolanic activity of fluid catalytic cracking catalyst residue (FC3R). thermogravimetric analysis studies on FC3R- portland cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33(4), 603–609. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Marques, J. C. Feasibility of eco-friendly binary and ternary blended binders made of fly-ash and oil-refinery spent catalyst in ready-mixed concrete production. Sustain. 2018, 10, 3136. [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Fang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F. Reuse of waste catalysts from petro-chemical industries for cement substitution. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1773–1783. [CrossRef]

- Vaičiukynienė, D.; Grinys, A.; Vaitkevičius, V.; Kantautas, A. Purified waste FCC catalyst as a cement replacement material. Ceramics–Silikáty. 2015, 59(2), 103–108.

- Al-Jabri, K.; Baawain, M.; Taha, R.;Al-Kamyani, Z. S.; Al-Shamsi, K.; Ishtieh, A. Potential use of FCC spent catalyst as partial replacement of cement or sand in cement mortars. Conctr. Build. Mater. 2013, 39, 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N. J.; Sengupta, P.; Gogoi, P. K.; Borthakur, P.C. Hydration behavior of lime-co-calcined kaolin-petroleum effluent treatment plant sludge. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32(2), 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A. M. Metakaolin as cementitious material: history, scours, production and composition – a comprehensive overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 41, 303–318. [CrossRef]

- Kamseu, E.; Cannio, M.; Obonyo, E. A.; Tobias, F.; Bignozzi, M. C.; Sglavo, V. B.; Leonelli, C. Metakaolin-based inorganic polymer composite: effects of fine aggregate composition and structure on porosity evolution, microstructure and mechanical properties. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2014, 53, 258–269. [CrossRef]

- Vejmelkova, E.; Pavlikova, M.; Keppert, M.; Kersner, Z.; Rovnanikova, P.; Ondracek, M. High performance concrete with Czech metakaolin: experimental analysis of strength, toughness and durability characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1404–11. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K. A.; Ramlochan, T.; Boddy, A.; Hooton, R. D.; Thomas, M.D.A. Increasing concrete durability with high reactivity metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2001, 23(6), 479–484. [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, J.; Kumar, A. Influence of pozzolanic additives on hydration mechanisms of tricalcium silicate. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101(8). [CrossRef]

- Menhosh, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Augusthus-Nelson, L. Long term durabil-ity properties of concrete modified with metakaolin and polymer admixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172(30), 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Krajci, L.; Mojumdar, S.C.; Janotka, I.; Puertas, F.; Palacios, M.; Kuliffayova, M. Performance of composites with metakaolin-blended cements. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 119, 851–863. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, L.; Payá, J.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M. V.; Tashima, M. M. High strength mortars using ordinary Portland cement–fly ash–fluid catalytic cracking catalyst residue ternary system (OPC/FA/FCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, E.; Payá, J.; Garcés, P. Chloride-induced corrosion of steel embedded in mortars containing fly ash and spent crackingcatalyst. Corrosion Sc. 2008, 50, 1567–1575. [CrossRef]

- Wilińska, I.; Pacewska, B. Calorimetric and thermal analysis studies on the influence of waste aluminosilicate catalyst on the hydration of fly ash–cement paste. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 116, 689–697. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, L.; Payá, J.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M. V.; Tashima, M. M. High strength mortars using ordinary Portland cement–fly ash–fluid catalytic cracking catalyst residue ternary system (OPC/FA/FCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, S.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M. V.; Soriano, L.; Payá, J. Evaluation of the pozzolanic activity of spent FCC catalyst/fly ash mixtures in Portland cement pastes. Thermochimica Acta. 2016, 632, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Gurdián, H.; García-Alcocel, E.; Baeza-Brotons, F.; Garcés, P.; Zornoza, E. Corrosion behavior of steel reinforcement in concrete with recycled aggregates, fly ash and spent cracking catalyst. Mater. 2014, 7, 3176–3197. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, F.; Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Tang, S. W. Comparison between the effects of phosphorous slag and fly ash on the C-S-H structure, longterm hydration heat and volume deformation of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118807. [CrossRef]

- Badogiannis, E.; Papadakis, V. G.; Chaniotakis, E.; Tsivilis, S. Exploitation of poor Greek kaolins: strength development of metakaolin concrete and evaluation by means of k-value. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34(6), 1035–1041. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, F.; Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Tang, S. W. Comparison between the effects of phosphorous slag and fly ash on the C-S-H structure, longterm hydration heat and volume deformation of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118807. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Comparison between the effects of superfine steel slag and superfine phosphorus slag on the long-term performances and durability of concrete. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 128(3), 1251–1263. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.M.L.; Souza, A.L.R.; Capuzzo, V.M. S.; Lameiras, R. Effect of the water/binder ratio on the hydration process of Portland cement pastes with silica fume and metakaolin. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. Mater. 2022, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Antonovič, V.; Sikarskas, D.; Malaiškienė, J.; Boris, R.; Stonys, R. Effect of pozzolanic waste materials on hydration peculiarities of Portland cement and granulated expanded glass-based plaster. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 4127–4137. [CrossRef]

- Agredo, J. T.; García, S. I.; Serna, J. T. Estudio comparativo de pastas de cemento adicionadas con catalizador de craqueo catalítico usado (FCC), y metacaolin (MK). Ciencia e Ingeniería Neogranadina. 2012, 22(1), 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Kaminskas, R.; Cesnauskas, V.; Kubiliute, R. Influence of different artificial additives on Portland cement hydration and hardening. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 95, 537–544. [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, P.; Cassagnabere, F.; Emam, A.; Lachemi, M. Influence of physico-chemical characteristics on the carbonation of cement paste at high replacement rates of metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 164–172. [CrossRef]

- Vaičiukynienė, D.; Pundienė, I.; Kantautas, A.; Augonis, A.; Janavičius, E.; Vaičiukynas, V.; Alobeid, J. Synergic effect of dry sludge from wastewater concrete plants and zeolitic by-product on ternary blended ordinary Portland cements properties. J. Cl. Prod. 2019, 244, 118493. [CrossRef]

- Pundienė, I.; Kligys, M.; Šeputytė-Jucikė, J. Portland cement based lightweight multifunctional matrix with different kind of additives containing SiO2. Eng. Mater. Tribol. XXII. Trans Tech Publications Ltd. Vol. 60. 2014, 305–308. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of FCCW and MK: F – faujasite, Q–quartz.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of FCCW and MK: F – faujasite, Q–quartz.

Figure 2.

SEM images of FCCW particles (a) and the surface of a single particle (b).

Figure 2.

SEM images of FCCW particles (a) and the surface of a single particle (b).

Figure 3.

SEM images of MK particles: a) general view of MK with scrap of expanded glass granules (EGG) , b) MK particles.

Figure 3.

SEM images of MK particles: a) general view of MK with scrap of expanded glass granules (EGG) , b) MK particles.

Figure 4.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste of C compositions after 7 days: a) C-0, b) C-CW, c) C-MK, d) C-CMK; CH – portlandite, E – ettringite, CSH – calcium silicate hydrate.

Figure 4.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste of C compositions after 7 days: a) C-0, b) C-CW, c) C-MK, d) C-CMK; CH – portlandite, E – ettringite, CSH – calcium silicate hydrate.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste of CP composition after 28 days: a) CP-CW, b) CP-CMK.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of hardened cement paste of CP composition after 28 days: a) CP-CW, b) CP-CMK.

Figure 8.

X-ray diffraction curves of hardened cement paste after 7 days of curing: a – C, b – CP; E – ettringite, P – portlandite, C – calcite, A – alite, B – belite, An – anatase.

Figure 8.

X-ray diffraction curves of hardened cement paste after 7 days of curing: a – C, b – CP; E – ettringite, P – portlandite, C – calcite, A – alite, B – belite, An – anatase.

Figure 9.

X-ray diffraction curves of hardened cement paste after 28 days of curing: a – C composition, b – CP composition; E – ettringite, P – portlandite, C – calcite, A – alite, B – belite, An – anatase.

Figure 9.

X-ray diffraction curves of hardened cement paste after 28 days of curing: a – C composition, b – CP composition; E – ettringite, P – portlandite, C – calcite, A – alite, B – belite, An – anatase.

Figure 10.

TG–DTG curves of hardened cement paste after 7 days of curing: a – C, b – CP.

Figure 10.

TG–DTG curves of hardened cement paste after 7 days of curing: a – C, b – CP.

Figure 11.

TG–DTG curves of hardened cement paste after 28 days of curing: a – C, b – CP.

Figure 11.

TG–DTG curves of hardened cement paste after 28 days of curing: a – C, b – CP.

Table 2.

Compositions of cement paste, (mass, %).

Table 2.

Compositions of cement paste, (mass, %).

| Composition |

Material |

W/B |

| PC |

FCCW |

MK |

SP* |

| C-0 |

100 |

– |

– |

– |

0.35 |

| C-CW |

91 |

9.0 |

– |

– |

0.35 |

| C-MK |

91 |

– |

9.0 |

– |

0.35 |

| C-CMK |

91 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

– |

0.35 |

| CP-0 |

100 |

– |

– |

1 |

0.25 |

| CP-CW |

91 |

9.0 |

– |

1 |

0.25 |

| CP-MK |

91 |

– |

9.0 |

1 |

0.25 |

| CP-CMK |

91 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

1 |

0.25 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).