1. Introduction

Reducing or avoiding greenhouse gas emissions and the associated limitation of global warming or the so-called climate risk index are some of the most important current goals of the global community. On the other hconsideringal and economic situation, the desire of many countries to be less dependent on their own energy supplies, the limited and geographically constrained availability of fossil fuels, and the globally uncertain and highly dynamic markets and prices are further increasing the need for energy independence, taking into account the possibilities for the various forms of energy for different application.

A sustainable and economically viable transformation to so called general energy system (GES), considering all usable forms of final energy such as electricity, heat, and gas for different consumer groups such as industry, commerce, households, and transport, is essential and must be viewed as a very long-term process [

1].

Various levels of government, including the European Union (EU) and individual countries such as Germany, already have sustainability strategies in place. These strategies outline methods for reducing greenhouse gases and establish different timelines for achieving greenhouse gas neutrality.

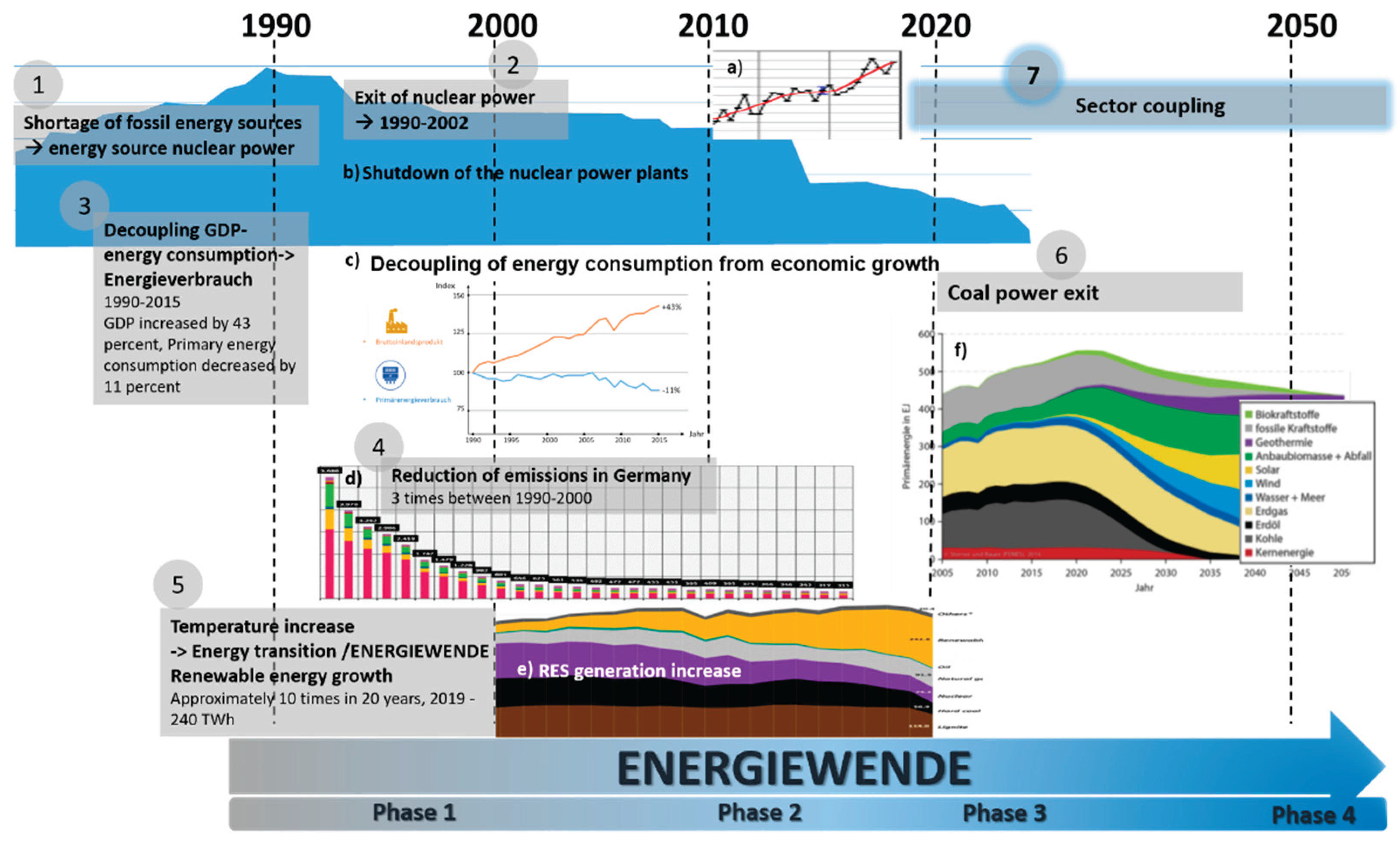

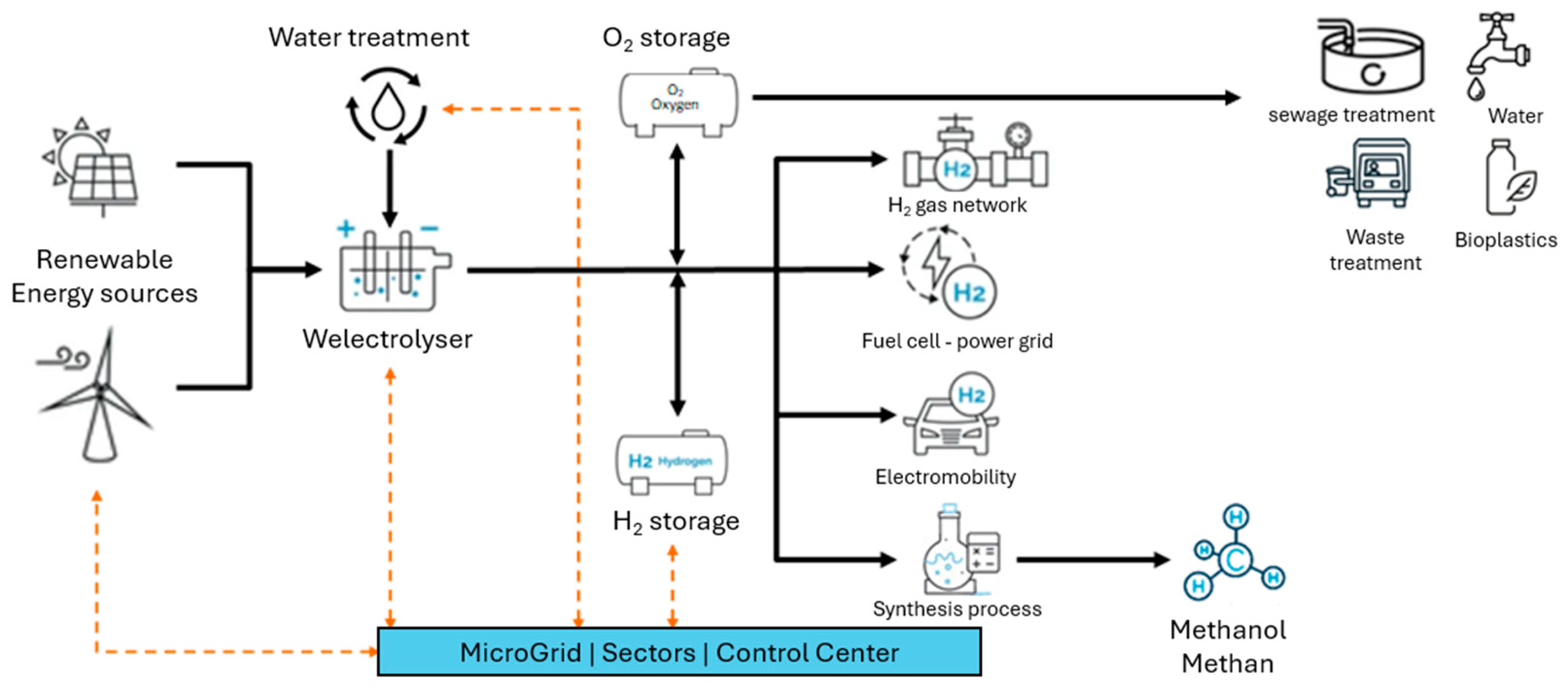

The EU, for example, wants to achieve greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045 with its “Green Deal” program. In some federal states in Germany, such as Saxony-Anhalt, there are concrete sub-strategies, such as the hydrogen strategy, to implement the energy transition, also known as the “Energiewende”, which is a lengthy process that began in the 20th century and continues to this day (see

Figure 1).

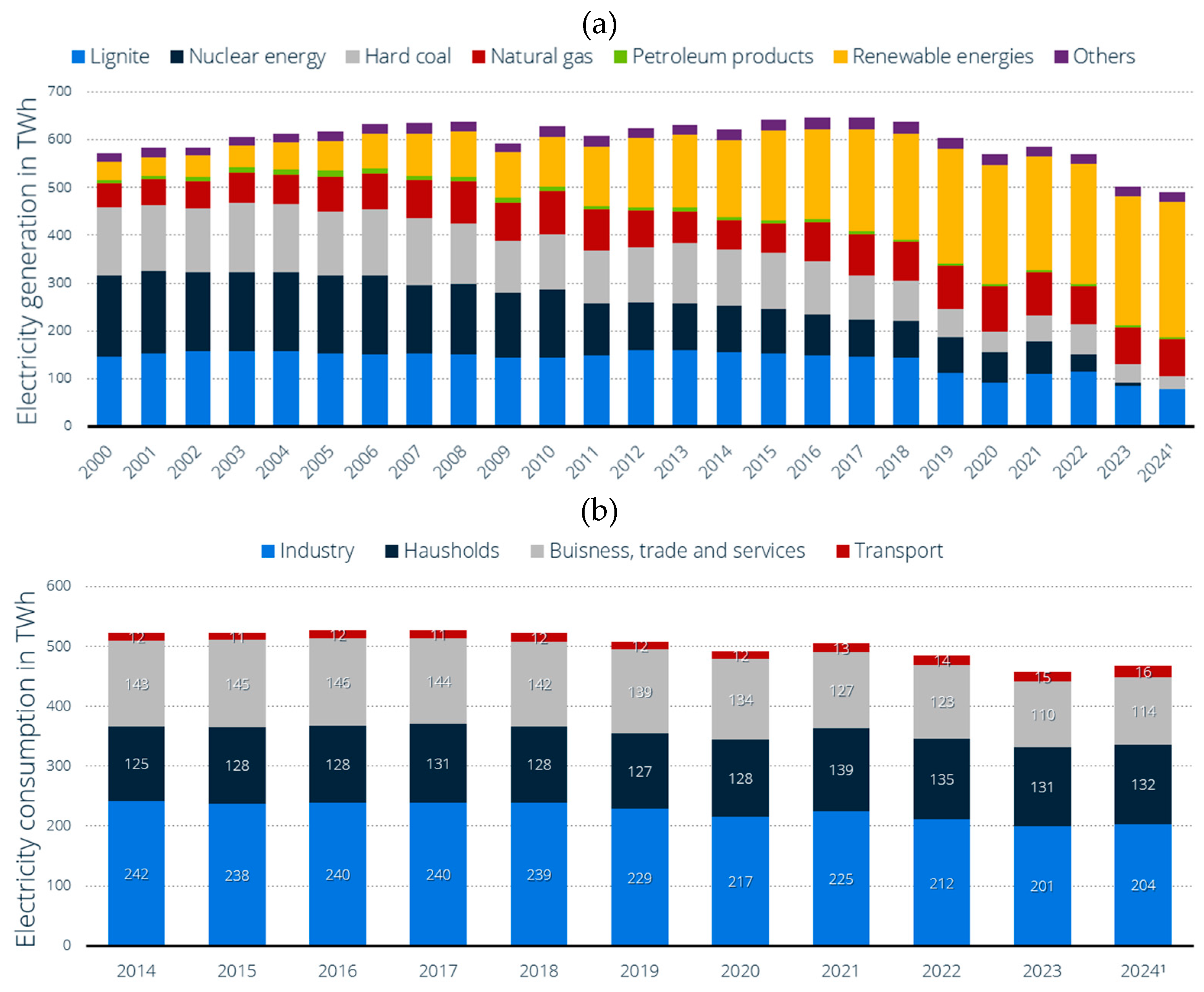

Generation by renewable energy plants, transport and distribution via the power grids, flexible loads, and storage (stationary and mobile) play a decisive role in the supply of electrical energy of the future and will continue to be expanded [

2,

3,

4]. On the other hand, other sustainable and necessary forms of energy use, such as green heat for households or green gases for industry, are not being developed and integrated into the system in a way that is comparable to renewable electricity generation. In 2024, the share of renewable energies in the electricity sector in Germany were 54,4%, in the heating sector 18,1%, and in the transport sector 7,2% [

5]. This development can certainly be explained by the initial focus on the electricity sector in the 2000s, among other things through the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG). Nevertheless, profound energy transformation is also necessary in the household and commercial sectors (especially heating) as well as in industry, including energy-intensive industries such as chemicals and steel (especially as a substitute for gas supplies) [

6]. In the future, this will be possible through so-called sector coupling—Phase 3 Measure 7 on

Figure 1 of the overall energy transformation from around 2020, which basically produces sustainable, further usable forms of energy such as hydrogen from green electricity through various processes.

Sector coupling, currently one of the most important measures for driving forward the energy transition, particularly in other sectors, is a bundle of technical and organizational measures that will result in the majority of the energy consumed in the future being generated from renewable sources. In order to use this renewable energy (mostly wind or solar energy) effectively, it is first converted into electrical energy in highly efficient plants. Depending on demand, green electricity or products made from green electricity through Power-to-X processes are made available to the sectors that use them [

7]. P2X distinguishes between the following areas, which represent a direct link and dependency between renewable energy and all sectors [

8]:

Power-to-Gas: Generation of energy gases from surplus renewable electricity through electrolysis and, if necessary, subsequent methanation (production of renewable natural gas by attaching hydrogen atoms to carbon atoms) as a central coupling element [

9].

Power-to-Heat: Use of surplus electricity in the heating market through the using controllable heating elements in local heat storage systems, district heating systems, or the connection of heat pumps [

10].

Power-to-Chemicals: Use of surplus electricity in industry for the targeted production of basic chemicals for chemical products [

11].

Power-to-Liquids: Process for producing fuels from surplus electricity via electrolysis/hydrogen production to usable basic chemicals (methanol) or fuels from synthetic hydrocarbons (dimethyl ester, kerosene, etc.) [

12].

Power-to-Mobility: Use of surplus electricity to charge electric vehicles, which in theory would also enable the battery content to be fed back into the grid [

13,

14]. Alternative use of methane produced from power-to-gas processes for CNG and LNG mobility or hydrogen for mobility.

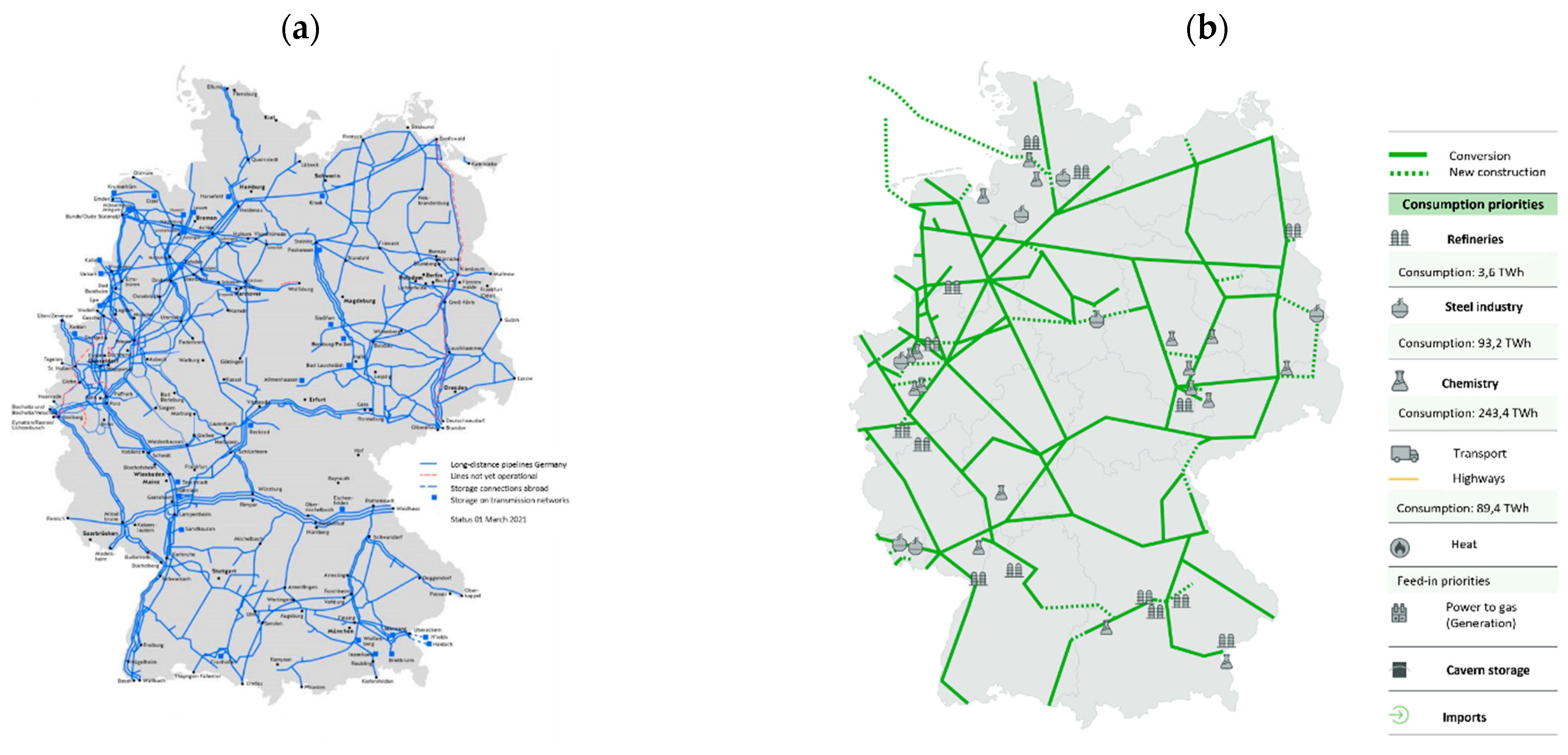

Power2Gas technology, which enables green hydrogen production based on renewable energy generation and water, is one of the most important branches, particularly for industry, transport, and private households, in making them more sustainable and less dependent on energy imports. Hydrogen is already an indispensable raw material today and is also necessary as an energy source in various industrial processes. In the future, climate-friendly hydrogen is expected to replace fossil fuels to drive decarbonization forward and, especially for energy-intensive and gas-based industries, it often offers the only way to advance energy transition. In the chemical industry, it is used as a means of producing ammonia (for fertilizers), methanol, and other chemicals, and in petroleum refineries, it is necessary for use in the “cracking” of hydrocarbons. In steel production, it can already be used as an additive to natural gas in direct iron reduction to produce emission-free steel in the future (complete gas replacement also relevant for other industries such as copper). In addition, hydrogen enables the provision of high-temperature heat for energy-intensive industries and building heating and can be used directly in the transport sector as a propellant (hydrogen mobility) [

15] or as a substrate for the production of synthetic fuels. Since hydrogen is versatile, could play a crucial role in the industrial, heating, and transportation sectors in the future (emission reduction), and is generally produced in a relatively costly and complex manner using renewable electricity and water, it is necessary to take a closer look at this challenge from both a technical application perspective (production process, transport and storage, safety and reliability) and economic perspective (costs, profits, business and operating models).

3. System Modeling and Practical Project Development—Technical and Economic Requirements and Potential

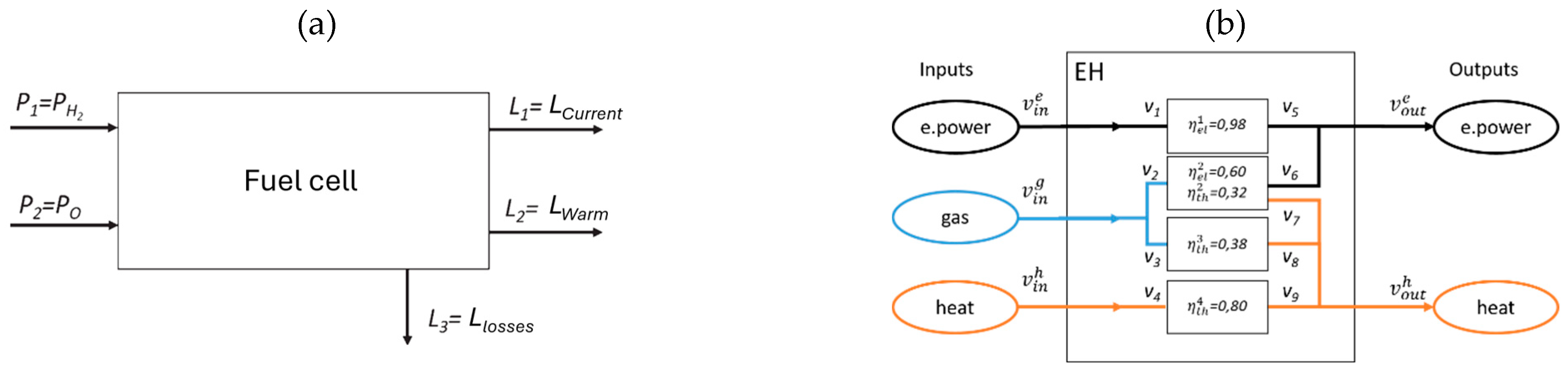

The models and associated simulations are used to investigate and verify the properties of the system and its components and interrelationships, and to map their physical and technical characteristics. A fundamental distinction is made between static and dynamic simulations, whereby the aim of dynamic simulations is to verify the control behavior of the system under investigation, i.e., its operation. During the planning phase, static models are used to describe the physical properties of the individual operating resources, the so-called design values, and are then expanded to include economic and financial aspects. Individual models, see

Figure 5, are connected as so-called black boxes (simplified/usable or complete models) in overall system structures, even across sectors, as energy hub models, whereby the interfaces, i.e., energy or coupling parameters, play a binding role.

The application of the energy hub modeling method allows highly complex structures of a multimedia energy conversion system to be represented in the form of a graph. Nodes of the graph represent the conversion processes, while media flows are represented by edges. Graph theory allows the relationships between input and output values (vectors) to be formulated mathematically. The input and output nodes enable the energy hub to be connected to other external structures and/or other energy nodes [

8].

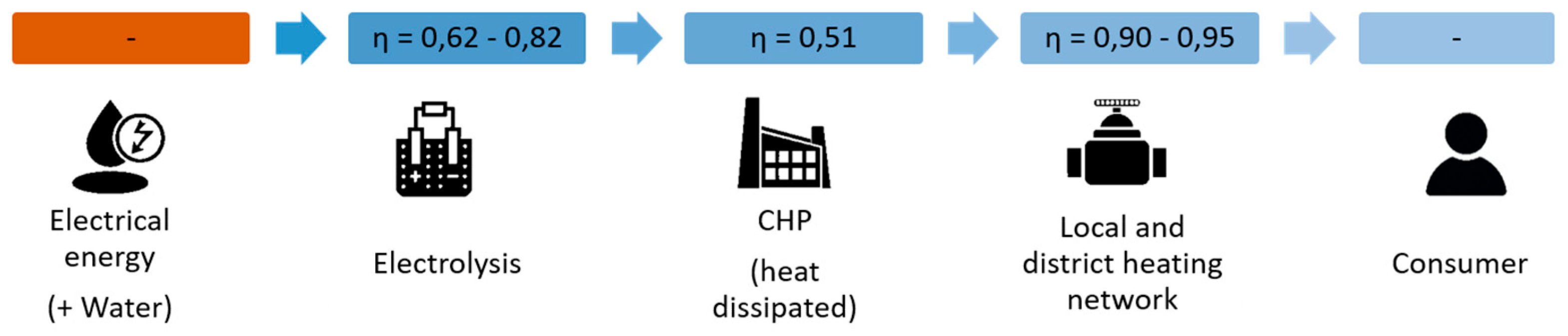

Depending on the application, the models can be highly complex, e.g., including replication via differential equations, which also contain Laplace transforms to enable the dynamic behavior of the plants or subsystems. For the planning of plants or, in this case, hydrogen infrastructures, it is sufficient to use static models that represent the individual plants and thus represent the overall system via the coupling point with the aid of, for example, efficiency factors, see

Figure 6.

In addition to the technical models that represent the physical properties of the individual plants and the overall infrastructure, their economic properties (in this case, CAPEX and OPEX in particular) are also taken into account in order to derive an overall model of the infrastructure and thus be able to drive the project development forward. CAPEX stands for “capital expenditures” and refers to the investments a company makes to acquire, improve, or maintain long-term assets such as buildings, land, machinery, or equipment. CAPEX includes expenditures for physical assets that are necessary for the company’s business activities and are expected to provide benefits over a longer period of time. Investments in assets are usually significant and can affect the company’s financial position, future growth, and profitability. Therefore, they are often carefully planned and evaluated before decisions are mad [

37]. OPEX, on the other hand, refers to the general operating expenses associated with the day-to-day operations of the company. These include expenses such as rent, salaries, utilities, marketing and sales, office supplies, and other similar costs. These expenses are typically recorded in the company’s income statement and have a direct impact on the company’s profit in a given fiscal year [

38].

When developing a hydrogen infrastructure project, all phases of the plant’s life cycle are generally considered, starting with idea development, design and planning, installation and commissioning, as well as operation and management, including maintenance and servicing, where cross-sector characteristics (electricity, water, gas) with a higher degree of complexity are to be expected. Not only technical requirements such as reliability and safety must be considered, but also economic factors, in particular CAPEX and OPEX, i.e., for example, investment, H2 production, and operating costs for the entire infrastructure.

Technical requirements already play a major role when considering electricity and water sources, i.e., it makes a technical and economic difference whether the electricity comes directly from renewable sources (required area, volatility, energy storage requirements to ensure continuous supply, electrical distance to the electrolyzer, fixed or variable electricity price PPA or direct sales) or the energy supply grid (note electricity mix, significantly higher stability of supply vs. renewable energy sources, possibly higher electricity transmission costs, grid effects, fixed or variable electricity price). These technical requirements regarding the electrical energy supply are reflected in the direct but also indirect costs (direct consumers or a hydrogen storage facility required, what volumes of hydrogen can be purchased when, and what quantities of hydrogen are required). In addition, there are direct technical requirements that may arise from the construction and operation of the electrolyzer on the part of the investor, such as technology (typically AEM or PEM), production efficiency (hydrogen and oxygen production capacity, nominal pressure, operating temperature, e.g.,: 80 kgH2/h, operating temperature 90+/-5 degrees Celsius), plant availability (e.g., 97% of the time), hydrogen purity (before and after purification, e.g.,: 99,995% and depending on further use, e.g.,: directly in the chemical industry or for mobility, which must first be transported further), electrolyzer power (e.g.,: 5 MW or 10 MW modules), electrolyzer supply voltage (depending on power and grid, but typically medium voltage 10, 20 kV), Cooling system (closed and self-sufficient or open), electrolyzer design (redundant, modular, or singular, pressure stages, e.g.,: 30 bar/g, and compressors), and operating options (standby, island, load-controlled, emergency operation).

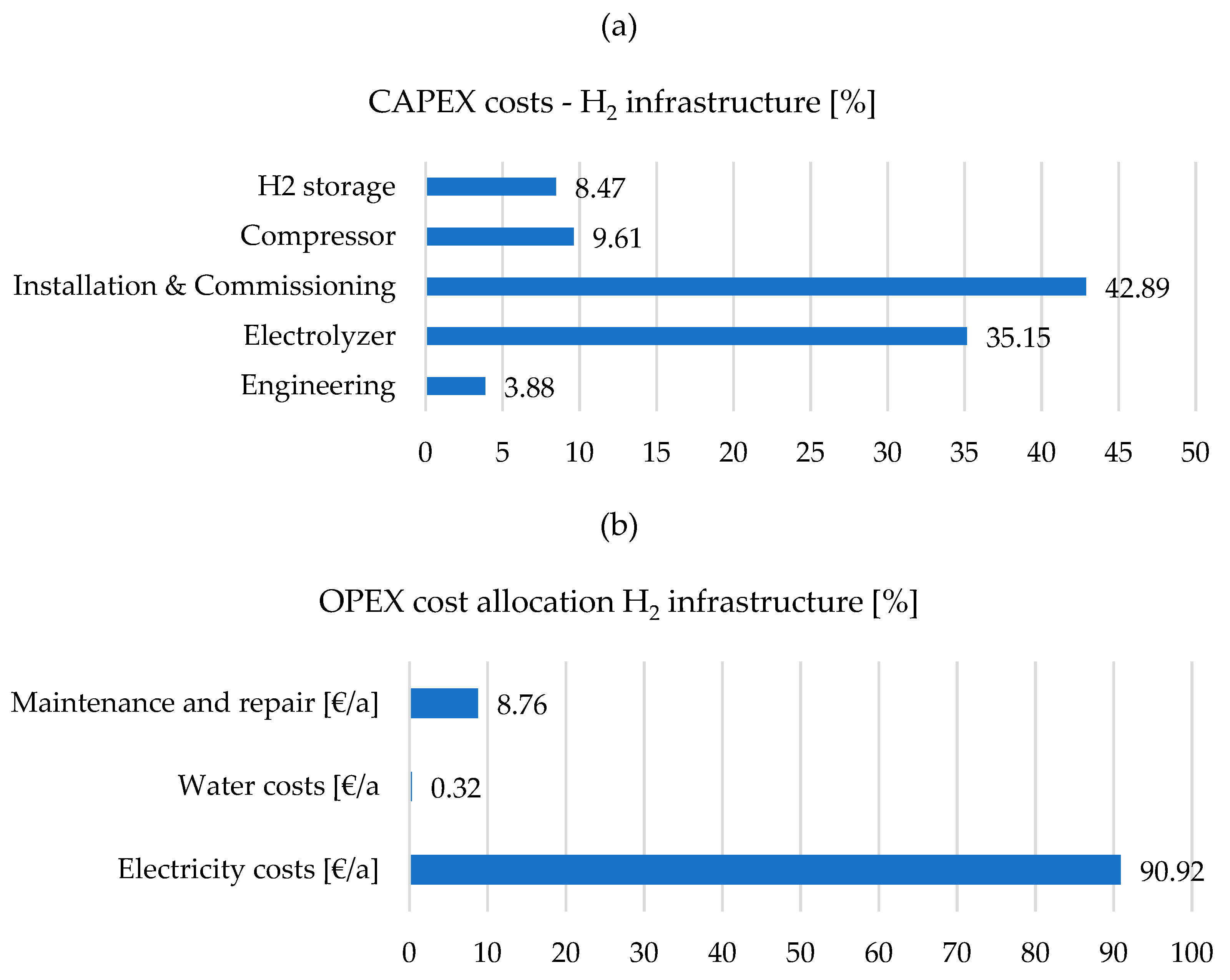

The costs (CAPEX) defined in the idea development, design, and planning phase must be supplemented by initially estimated operating costs (OPEX), take technical and specific requirements into account, and estimate uncertain risks (costs). For a practical hydrogen infrastructure with an electrolyzer (including power − 10 MW, production capacities of 800 Nm3/h, efficiency of 0,85, plant availability of 8200 h/a] and a compressor with a mass flow of 90 kg/h coupled with an H

2 storage tank (capacity 2000 kg), a cost model was developed taking into account all relevant parameters (including water consumption and costs, electricity consumption and price). Construction, installation, and commissioning play a decisive role in the investment costs (more than 40% of the total investment costs), followed by the electrolyzer as the system delivered to the installation site (more than 35% of the total investment costs). This cost structure for construction and commissioning is mainly due to the costs of the engineers and material costs (foundations), which have not yet been optimized, especially for new technologies, but this is expected to happen in the future. The costs of the technology are, on the one hand, the plant costs, which are also not yet widely used systems with long experience in planning and operation, as well as transport and insurance see

Figure 7a. The costs for hydrogen storage and any compressors that may be necessary to achieve higher pressure levels are elements that can vary depending on the application (power supply to the electrolysis plant directly from renewable sources or from the grid, direct H

2 use, e.g.,: in the chemical industry as a substrate or as an energy source for mobility). Engineering costs of approximately 4% must always be taken into account and should be optimized as experience with the planning, construction, and operation of such infrastructure increases.

Electricity costs for supplying the electrolyzer play a decisive role (more than 90%) in the operating costs of a hydrogen infrastructure and can vary greatly depending on the supply concept (grid connection, length of the line) and the price of electricity (renewable, grid electricity mix, PPA contracts, exchange purchase). Maintenance and repair costs include, among other things, maintenance of the systems and necessary repair costs (e.g.,: age-related replacement of membranes), hedging of possible risks in connection with guaranteed system availability (guaranteed parameters according to contract) and amount to approximately 9% in the example shown. On the other hand, the costs for water procurement play a minor role (0,3%), but may increase significantly in the future due to various scenarios (water scarcity, climate change) see

Figure 7b.

When planning the hydrogen infrastructure, and in particular the electrolyzer, a technically viable solution must be found that meets the requirements and offers the most economical configuration between CAPEX and OPEX costs. On the one hand, there is the technological possibility of reducing the electrolyzer’s power consumption, which could clearly reduce OPEX, but on the other hand, this would increase the CAPEX of the plants due to reduced operating assets. On the other hand, increasing the hydrogen production capacity (operating hours) of a plant also means rising electricity costs and accelerated plant aging, and thus also the so-called maintenance CAPEX costs.

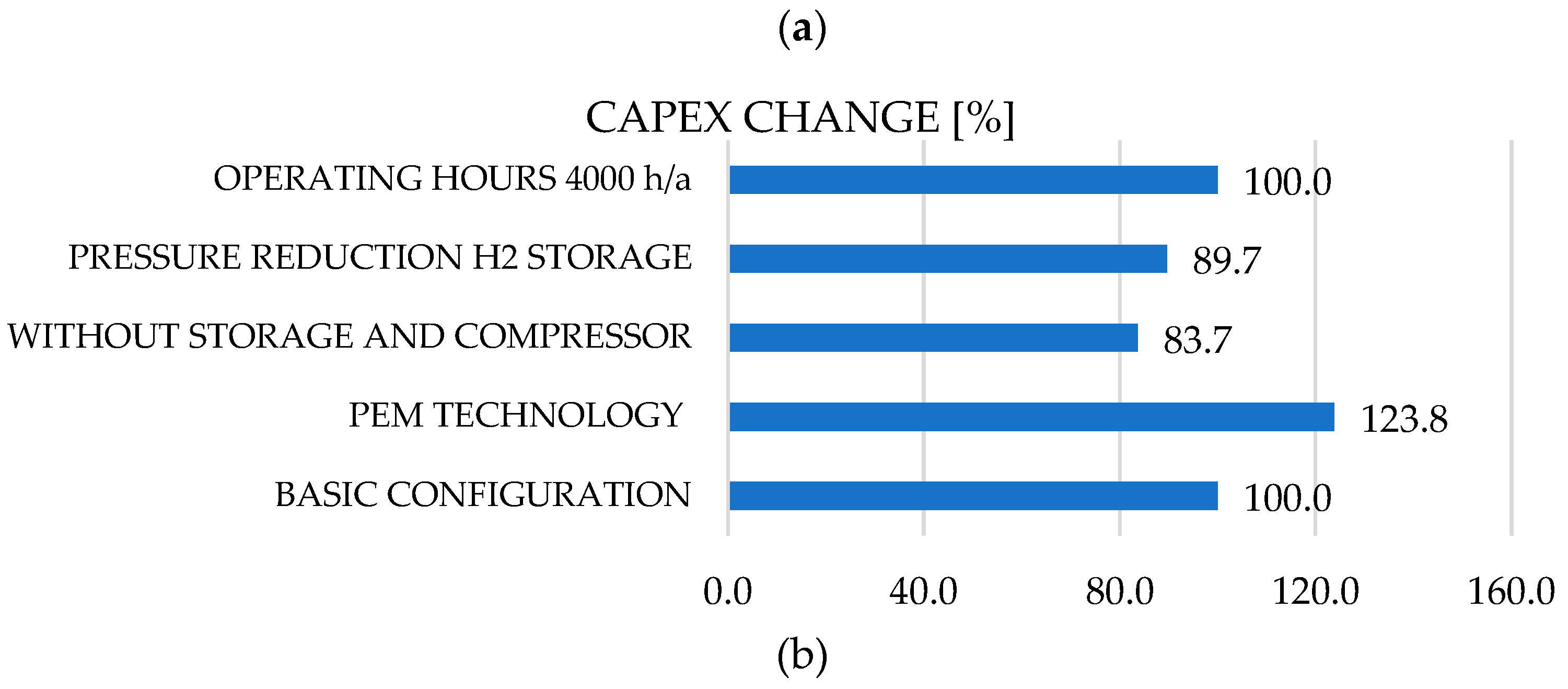

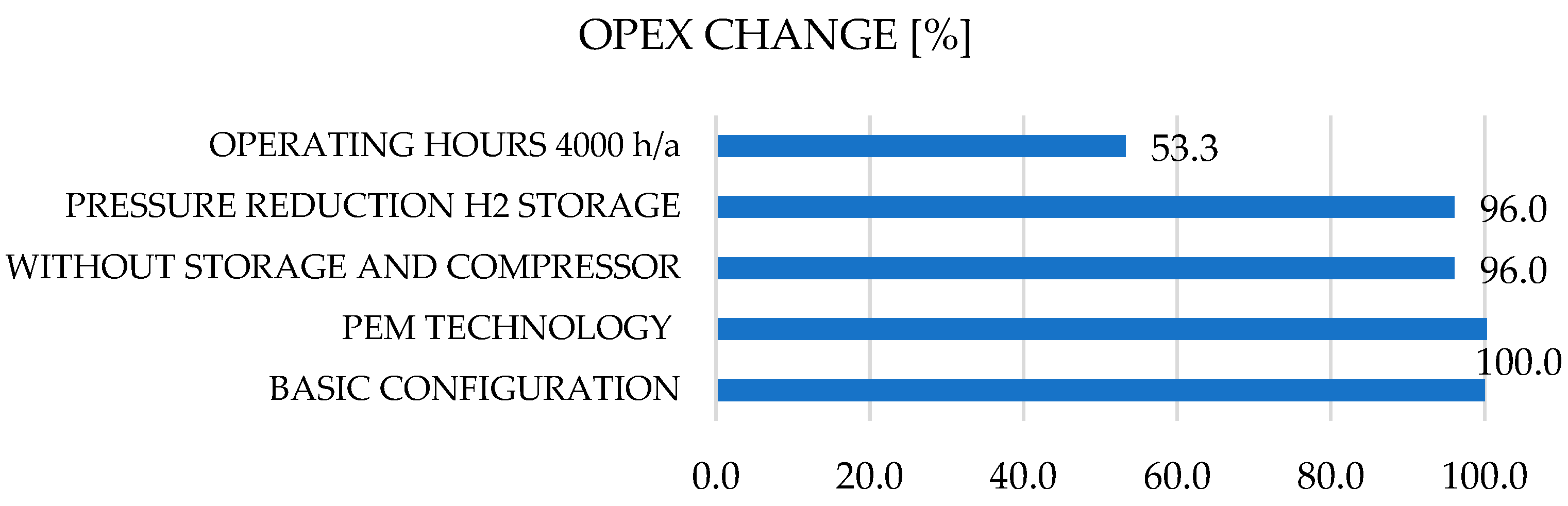

In the developed model of the overall hydrogen infrastructure, which takes into account both technical plant parameters such as efficiency, pressure stages, temperatures, and others, as well as economic parameters such as investment and operating costs, various scenario changes are calculated in order to investigate the possible influence on the cost structure.. Based on the base scenario system configuration (electrolysis capacity 10 MW, production capacity 800 Nm3/h, efficiency of 0,85, plant availability of 8200 h/a] and a compressor with a mass flow of 90 kg/h coupled with an H

2 storage tank (capacity 2000 kg), see

Figure 9, four further scenarios were developed and modeled:

1. Replacement of the AES with PEM technology for the electrolyzer,

2. System without H2 storage and necessary compressor,

3. Reduction of the pressure stage at the outlet from 700 bar to 350 bar,

4. Reduction of the expected operating hours from 8200h/a to 4000 h/a.

These scenario extensions correspond to real-world applications (e.g.,: direct H2 feed and therefore no H2 necessary because consumption is very high in relation to production, direct supply of the electrolyzer from renewable energy sources and therefore reduction of operating hours to 4000 h/a) and are evaluated in terms of possible CAPEX and OPEX impact.

Figure 8.

Cost allocation (CAPEX (a), OPEX (b)) for typical hydrogen infrastructure.

Figure 8.

Cost allocation (CAPEX (a), OPEX (b)) for typical hydrogen infrastructure.

It should be noted that the large CAPEX increase of approximately 23% of the total investment is caused by the change in technology from AES to PEM, which in practice is justified by, for example, increased requirements for dynamic operation of the electrolyzer, e.g., direct renewable feed. The largest reduction in total CAPEX investment, approx. 16%, can be achieved by dispensing with the installation of the hydrogen storage tank and associated compressor, which is understandable in terms of plant costs and feasible for certain applications see

Figure 8a. Operating costs (OPEX) can be significantly reduced by approximately 47% by halving the operating hours, which is due in particular to lower electricity costs and optimal operation of the systems (fewer cycles and less maintenance)

Figure 8b. It should be noted that the optimization of both CAPEX and OPEX costs are interrelated and must always be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, in the case of PEM electrolysers, CAPEX costs are generally reduced (e.g., by increasing the life cycle and durability of the plant, which reduces investment costs and, at the same time, operating costs), although there is a tipping point beyond which profits can decline. On the other hand, such complex and cross-sector hydrogen systems (power generation, water treatment, electrolyzer, storage, compressor, peripherals) are developed retrospectively, i.e., the system configuration is defined by end-use requirements (power, time and power gradients, limits, etc.).

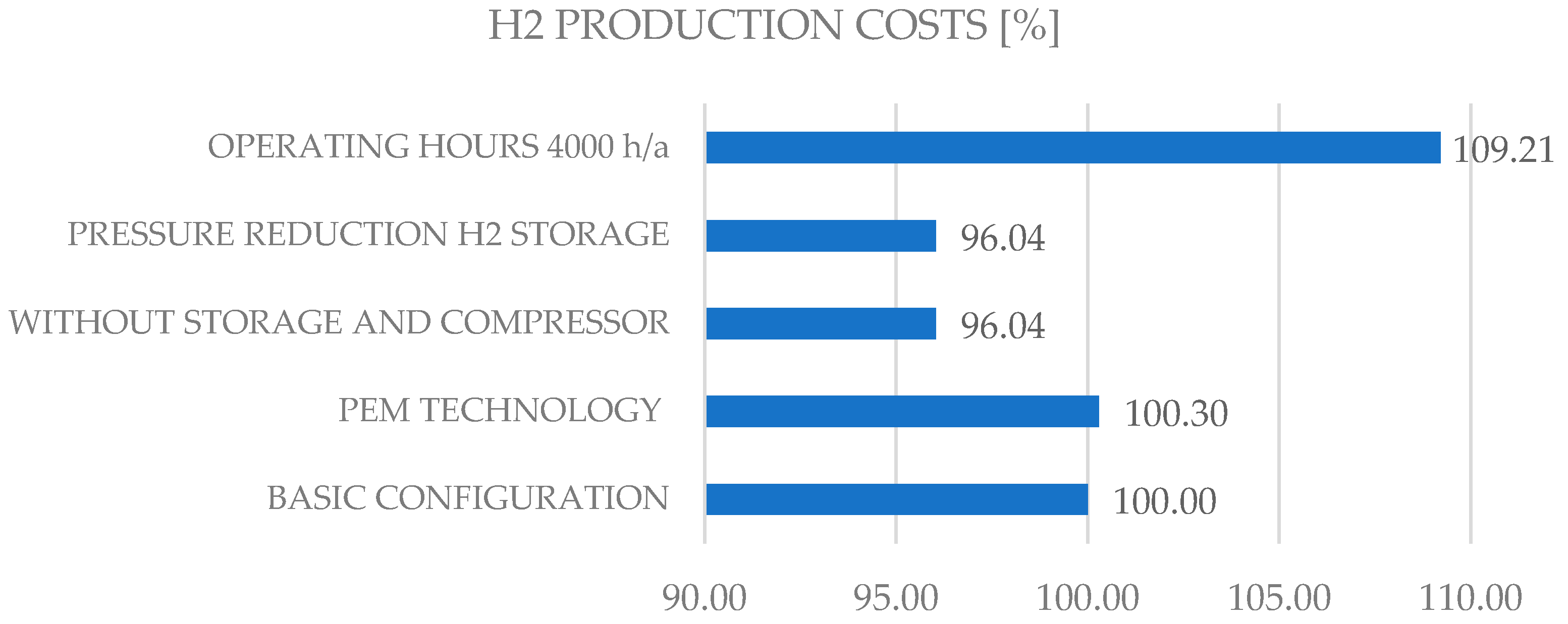

The final commercial and economic assessment of the overall system, including equipment and infrastructure, is reflected in the final price of the green hydrogen produced, so that competitive pricing can be achieved for customers, taking into account technical and environmental requirements, see

Figure 9. As can be seen from the illustration, the price difference between different scenarios varies and can be influenced by CAPEX (e.g., without storage and compressor, the production price of 1 kgH

2 is reduced by approx. 4% compared to the base) or OPEX (reduction of operating hours leads to an increase in the price of the production price of 1 kgH

2 by approx. 9%), without taking into account possible transport costs, margins, and taxes. The future number for hydrogen costs to be achieved is 2 €/kg. Today, the cost of producing hydrogen from solar power plants is 6 €/kg and from wind power 4 €/kg. Regionally, green hydrogen can already be produced for 2.50 €/kg. For 2050, some scenarios simulated in various studies predict significantly lower costs for green hydrogen of up to 1.26 €/kg [

1].

Figure 9.

H2 production costs in relation to different system and operating configurations.

Figure 9.

H2 production costs in relation to different system and operating configurations.

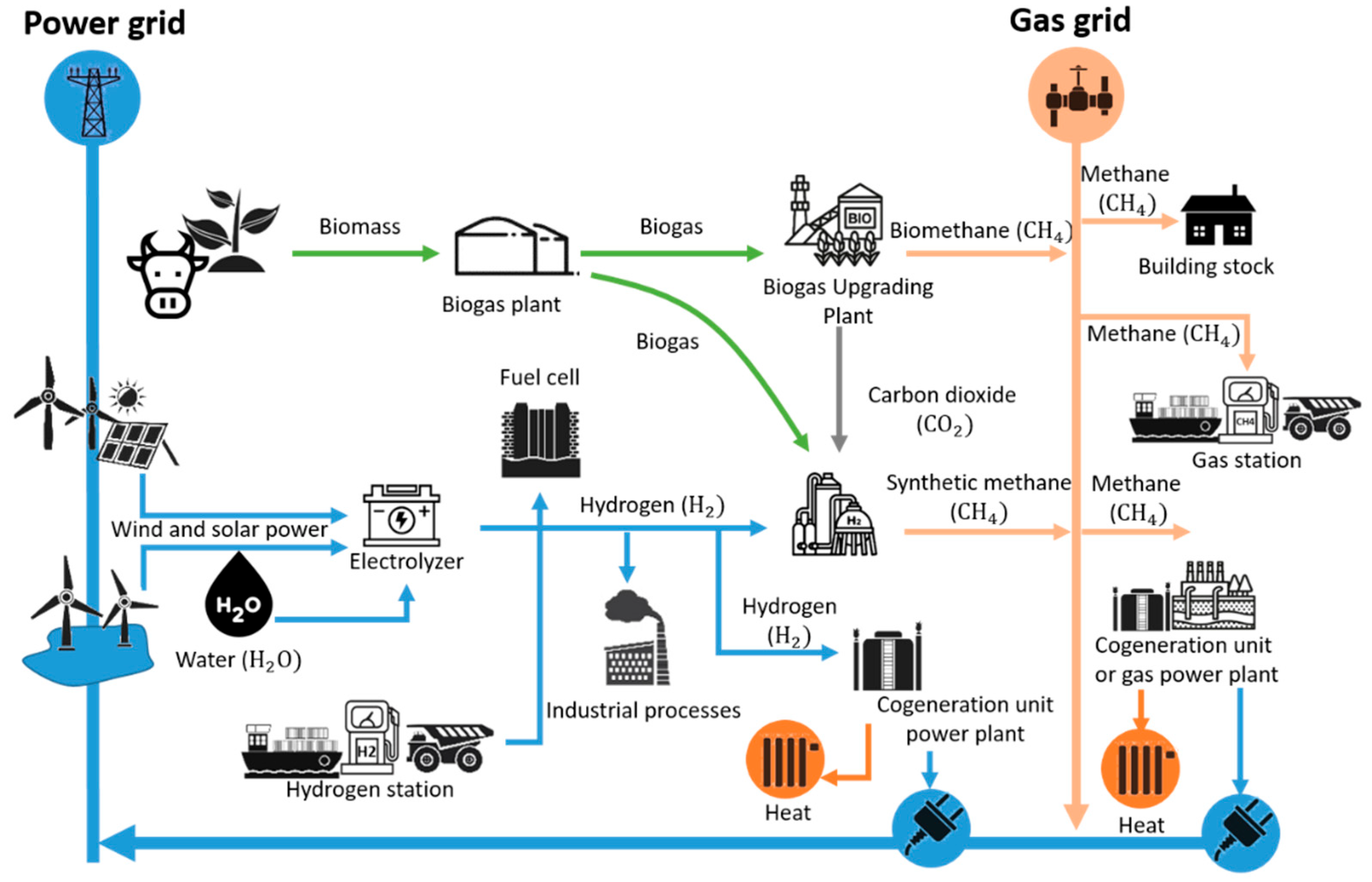

The planning, construction, and operation of such complex and relatively new infrastructures, including technologies, involve various technical and subsequent economic direct and indirect risks that can only be considered to a limited extent when drawing up the financing concept. These include, among other things, technology ordering and its delivery and transport route (loading, unloading, mode of transport, and length), including insurance, adherence to deadlines for construction and commissioning, ensuring a neutral cash flow for such long and cost-intensive investments, continuous optimization of detailed planning, and adaptation to conditions and situations encountered. As can be seen from the case study presented and described for implementation, various technical and economic factors play an important role in developing and implementing an optimal case. In addition, the cross-sector hydrogen infrastructure (electricity, water, gas) offers many potentials, such as electricity storage or supplying other structures with green heat, but also poses various risks (new technologies, complex risk assessment that must be considered across sectors). Furthermore, the future will involve planning, building, and operating individual H

2 infrastructures to create a continuous link beyond system boundaries and establish a hydrogen cycle, thereby exploiting various synergy effects (efficiency, flexibility, reliability) while ensuring technical feasibility and economic viability, see

Figure 10. The multifaceted application possibilities of green hydrogen should be taken into account, considering its properties such as energy density and storage, thereby developing an energy cycle economy with a focus on green hydrogen as a hub for the energy transition, which, depending on necessity and thanks to the flexibility of H2, allows the reliability of supply to be ensured in all energy sectors, see

Figure 10.