1. Introduction

Plant height (PH) and internode length (IL) are key determinants of ideal plant architecture and are closely associated with crop yield and plant adaptability. In maize, optimizing plant architecture has become a major focus in breeding programs to enhance productivity and resilience under varying environmental conditions [

1]. As one of the world’s most important cereal crops, maize is frequently subjected to abiotic stresses that can compromise structural stability and ultimately limit yield [

2].

Genetic studies have identified several genes that regulate maize internode elongation and plant stature. For example, the dwarf gene

Brachytic2 (

br2) shortens lower internodes and alters stem morphology [

3], while its allele

qpa1 reduces PH and ear height (EH) and increases stem thickness [

4]. The

gif1 gene promotes cell proliferation in stems, and its mutant exhibits shortened internodes [

5]. Similarly, transcription factors such as

BLH12 and

BLH14 interact with

KNOTTED1 to maintain meristem activity and ensure normal stem elongation [

6]. These findings underscore the genetic complexity underlying internode development and its importance in shaping plant architecture.

Internode elongation is coordinately regulated by a network of hormone signaling pathways, including auxin, gibberellin (GA), brassinosteroids (BR), ethylene, jasmonic acid (JA), and strigolactone (SL) [

7]. For instance, the

GRAS42 gene modulates internode development through BR-mediated signaling and cell wall biosynthesis [

8]. Mutants of

GRAS42 exhibit a dwarf phenotype, with plant height reduced to approximately 60% of the wild type due to shortened internodes [

9]. This effect is further enhanced in the

nana plant1-1 and

gras42-mu1021149 double mutant, underscoring the gene’s role in internode regulation [

9]. Similarly, disrupted GA signaling inhibits internode elongation and reduces plant height [

10], while the jasmonate analog Coronavirin suppresses maize internode elongation by downregulating the cell wall-associated gene

ZmXTH1 [

11]. Ethylene also contributes to this process, as evidenced by the

ZmACS7 gene, which influences the elongation of both internode and auricle cells [

12]. Additionally, strigolactone biosynthesis is critical for normal stem development; mutations in

ZmCCD8, which encodes a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase, impair SL production and lead to reduced stem diameter, compromised internode elongation, and overall plant dwarfism [

13]. Collectively, these findings illustrate the sophisticated hormonal crosstalk that integrates multiple pathways to coordinately control stem growth and architecture.

Despite advances in understanding PH genetics, the genetic basis of specific internode proportions - particularly those above the ear - remains underexplored. Traditional studies often focus on overall PH or ear height, yet the proportional length of individual internodes may offer more precise targets for architectural improvement. For example, the first internode above the ear (U1) has been noted for its structural importance and susceptibility to environmental stress [

14,

15]. Studies have demonstrated that knockout of the

ZmD1 gene suppresses longitudinal elongation while promoting transverse expansion of internode cells, leading to reduced plant height and shortened internodes [

16]. The

ZmTE1 gene plays a crucial role in maintaining internode meristem formation and cell division, and regulates internode elongation by promoting cell extension [

17]. Notably, in maize breeding research, three quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with internode length have been identified, from which 303 related genes have been annotated [

18]. These genes influence internode elongation primarily by mediating phytohormone signaling, modulating receptor activity, and regulating carbon metabolism pathways. Among them,

ZmIL1,

ZmIL2 and

ZmIL3 have been highlighted as key candidate regulators of internode length [

18].

In this study, we employed a GWAS approach using a diverse association panel of 288 inbred lines genotyped with 1.25 M SNPs to dissect the genetic architecture of internode proportion traits, with a particular focus on U1/HAE and U1/PH. Our objectives were to: (1) characterize phenotypic variation in internode-related traits across two environments; (2) identify significant SNPs and stable QTL associated with internode proportions; and (3) pinpoint candidate genes through integrated bioinformatic and haplotype analyses. This work provides new insights into the genetic regulation of maize plant architecture and offers candidate loci for molecular breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

The association mapping panel consisted of 288 maize inbred lines, including 131 tropical/subtropical and 157 temperate accessions. In 2024, the panel was planted at two field locations: Yuanyang Modern Agricultural Science and Technology Park (35°N, 113°E; designated as 24YY; average altitude: 74 m; mean annual temperature: 14.3 °C; mean annual precipitation: 550 mm; soil organic matter: 10.6 g·kg⁻¹; total nitrogen: 1.1 g·kg⁻¹) and Zhangye, Gansu (39°N, 100°E; designated as 24GS; 39°N, 100°E; designated 24GS; average altitude: 1400–1500 m; mean annual temperature: 8.4 °C; mean annual precipitation: 197.4 mm; soil organic matter: 18.0 g·kg⁻¹; total nitrogen: 1.1 g·kg⁻¹). Each inbred line was replicated twice per location in a full randomized block design, with a row length of 3.0 m, plant spacing of 0.25 m, and row spacing of 0.67 m. Standard field management practices were followed throughout the growing season.

2.2. Phenotypic Data Collection

At physiological maturity, five representative plants per row were selected for phenotyping. Plant height (PH) and ear height (EH) were measured in the field for each plant. Subsequently, whole stalks were harvested and transferred to the laboratory for detailed internode measurements. Internode traits included the length of the ear-position internode (designated Zero), the lengths of the five internodes above the ear (U1–U5), and the five below the ear (B1–B5). (

Supplementary Figure S1)

2.3. Phenotypic Data Analysis

For each trait, the mean value per inbred line was first calculated from five plants within each environment. General descriptive statistics, including range, mean, standard deviation (SD), skewness, kurtosis, and coefficient of variation (CV), were computed using WPS Office 12.1.0. To assess environmental effects, Pearson correlation between traits across the two locations was evaluated in R (v4.3.1). Best linear unbiased predictions (BLUP) for each trait across the two environments (24GS and 24YY) were then estimated using the lme4 package, with genotype as a random effect and environment as a fixed effect. Both the environment-specific line means and the across-environment BLUP were used as phenotypic inputs in the subsequent genome-wide association analysis. Frequency distributions of phenotypic data were visualized with GraphPad Prism 10.1.2.

2.4. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS)

Genotype data for the association panel consisting of approximately 1.25 million (1.25M) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers (B73 RefGen_V4) were obtained from the publicly available dataset of Prof. Jianbing Yan (Huazhong Agricultural University) [

19]. After rigorous quality control of each dataset, genotypes from four genotyping platforms (600K, 50K, RNA-seq, and GBS) were merged. Conflicting locus calls were resolved by prioritizing platforms in the order 600K > 50K > RNA-seq > GBS. Genotype imputation was performed using Beagle v4.0 [

20]. To optimize imputation parameters and validate accuracy, chromosome 10 markers were used as a reference set [

21]. A total of 15,000 known genotypes (approximately 3% of chromosome 10 loci, with three individuals per locus) were randomly masked as missing, and imputation reliability was assessed by comparing the masked true genotypes with the imputed values. Testing multiple parameter combinations identified the optimal settings: window = 50,000, overlap = 5,000, ibd = true. Two imputation strategies were compared: the “remove-then-impute” strategy (filtering SNPs with >90% missing rate before imputation) achieved an average accuracy of 96.93%, whereas the “impute-then-remove” strategy (filtering after imputation) yielded a lower accuracy of 95.89% [

21]. Accordingly, the former strategy was adopted for final analyses [

21]. An integrated genetic map comprising 2.65 million loci was constructed for 540 individuals; of these, 1.25 million loci with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 5% were retained for downstream studies [

21]. The final merged HapMap-format genotype dataset is available at

www.maizego.org/Resources. GWAS was performed in Tassel 5.2.81 using the Q + K mixed linear model to correct for population structure and kinship. The significance threshold was set at

p ≤ 1.0 × 10⁻⁵ [

18]. Result visualization-including Manhattan plots, quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots, and composite figures-was conducted in RStudio (2025.9.2.0) with the CMplot, ggplot2, ggridges, and corrplot packages.

2.5. Candidate Gene Identification

For each significantly associated SNP, a 100-kb window (50 kb upstream and downstream) was defined as the QTL interval, corresponding to the average linkage disequilibrium decay distance (~50 kb) in this population [

22]. Gene annotations within these regions were retrieved from the MaizeGDB database (B73 RefGen_V4,

https://maizegdb.org/). Functional descriptions and expression profiles of candidate genes were examined, and expression heatmaps were generated using the Omicshare online platform (

https://www.omicshare.com/tools/Home/Task).

2.6. Haplotype Analysis

Haplotype analysis was carried out with Tassel 5.2.81. For candidate genes, gene-based association analysis was performed by extracting gene sequences from the association panel and subsequently evaluating their statistical associations with the target phenotypic traits. Significant SNPs were used to construct haplotypes. Haplotypes represented by fewer than 10 accessions were excluded from further analysis. Phenotypic differences among haplotypes were assessed for statistical significance using a two-tailed t-test.

3. Result

3.1. Phenotypic Variation in Internode-Related Traits

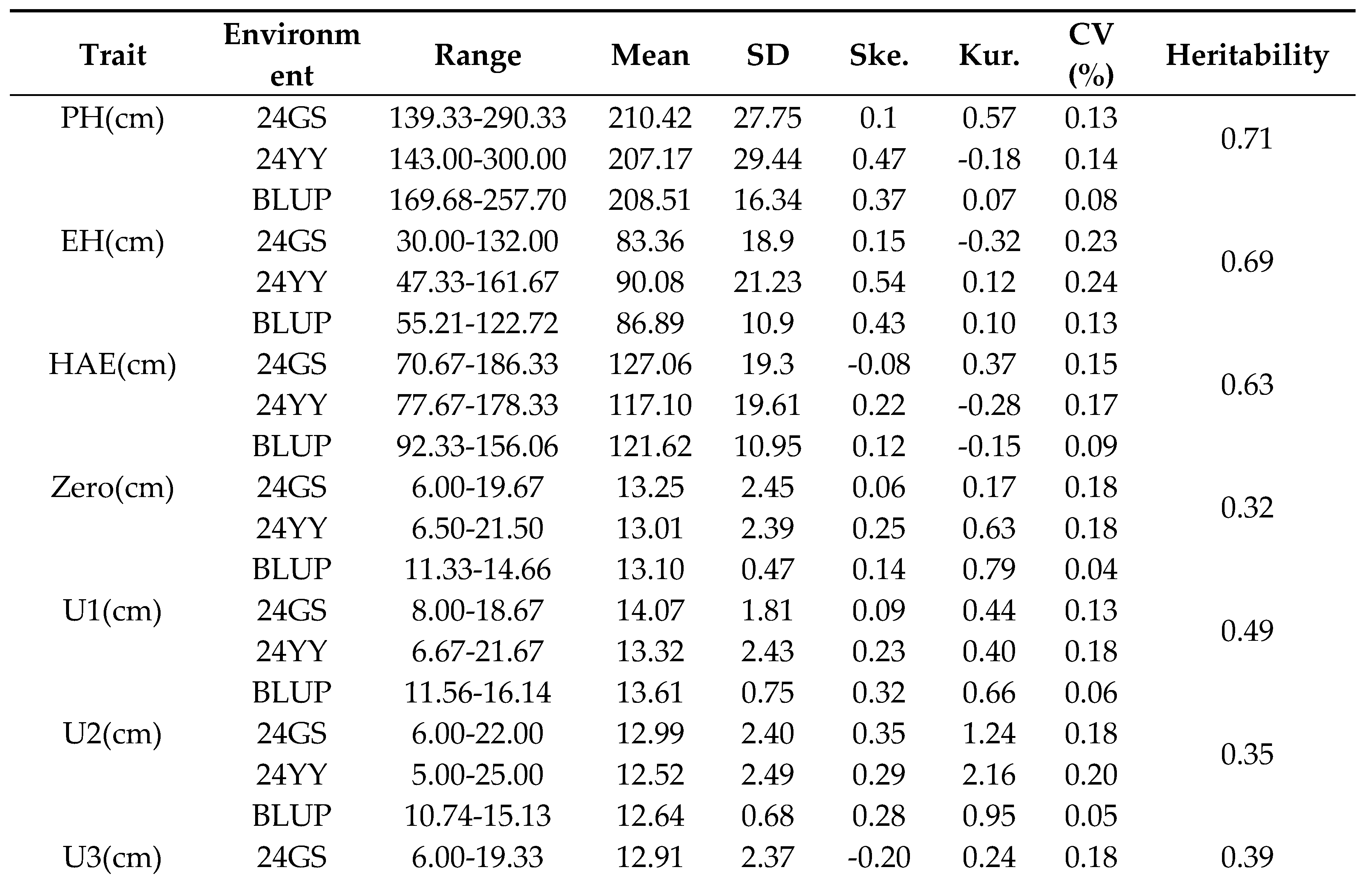

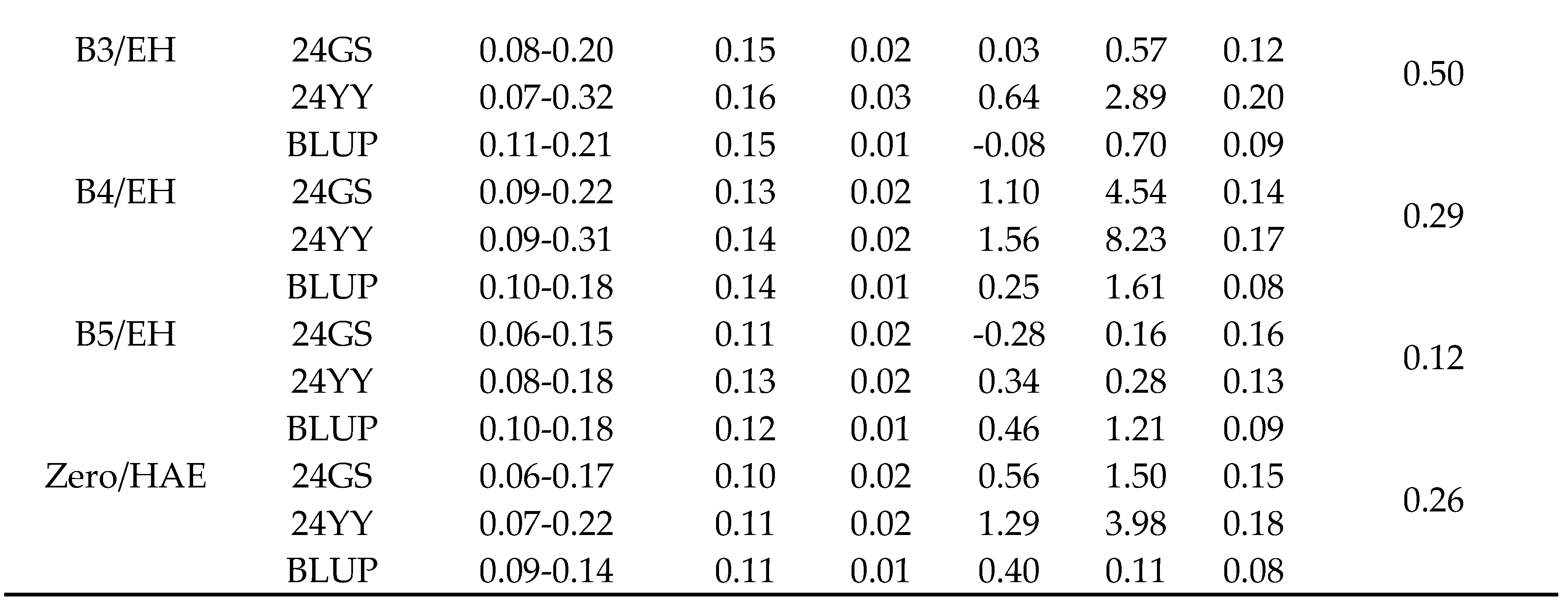

A total of 28 internode-related traits were investigated in this study, including plant height (PH), ear height (EH), height above ear (HAE), lengths of internodes above the ear (U1–U5), lengths of internodes below the ear (B1–B5), the ear-position internode (Zero), the average length of the five internodes above the ear (U_AVE), and a series of proportional traits: U1-U5 to HAE, B1-B5 to EH, Zero to HAE, U_AVE to HAE, and U1 to PH. All traits exhibited considerable phenotypic variation across the association panel. Coefficients of variation (CV) ranged from 0.02 to 0.28 under the two environments and their best linear unbiased predictions (BLUP) (

Table 1). Skewness and kurtosis values for each trait were generally between -1 and 1, indicating that the phenotypic distributions were approximately normal (

Supplementary Figure S2) and consistent with quantitative inheritance controlled by multiple genes. Heritability was estimated for all traits under two environments, and the results showed that the heritability of different traits exhibited significant high-low differentiation characteristics between the two environments. These results confirm that the panel captures broad genetic diversity suitable for genome-wide association mapping of internode architecture.

Notably, within the same environment, internode lengths (IL) at different positions above the ear were strongly positively correlated (

Supplementary Figures S3A–C), suggesting shared genetic regulation or linkage among underlying loci. In contrast, correlations for the same IL trait across different environments were markedly lower (

Supplementary Figures S3D–F), highlighting the environmental sensitivity of upper-ear internodes and the dominant role of environment in shaping their phenotypic expression.

To further evaluate the architectural role of internodes above the ear, we examined the proportional contributions of individual internodes. The ratio of the first internode length (U1) to both height above ear (HAE) and plant height (PH) was consistently and significantly higher than that of the other four internodes across environments and BLUP (

Supplementary Figure S4). This stable, dominant proportional role suggests that U1 is a structural cornerstone of the upper-plant profile and likely exerts a major influence on overall above-ear morphology. Given its pronounced and consistent phenotypic contribution [

14,

15].we focused subsequent genetic analyses on the traits U1/HAE and U1/PH.

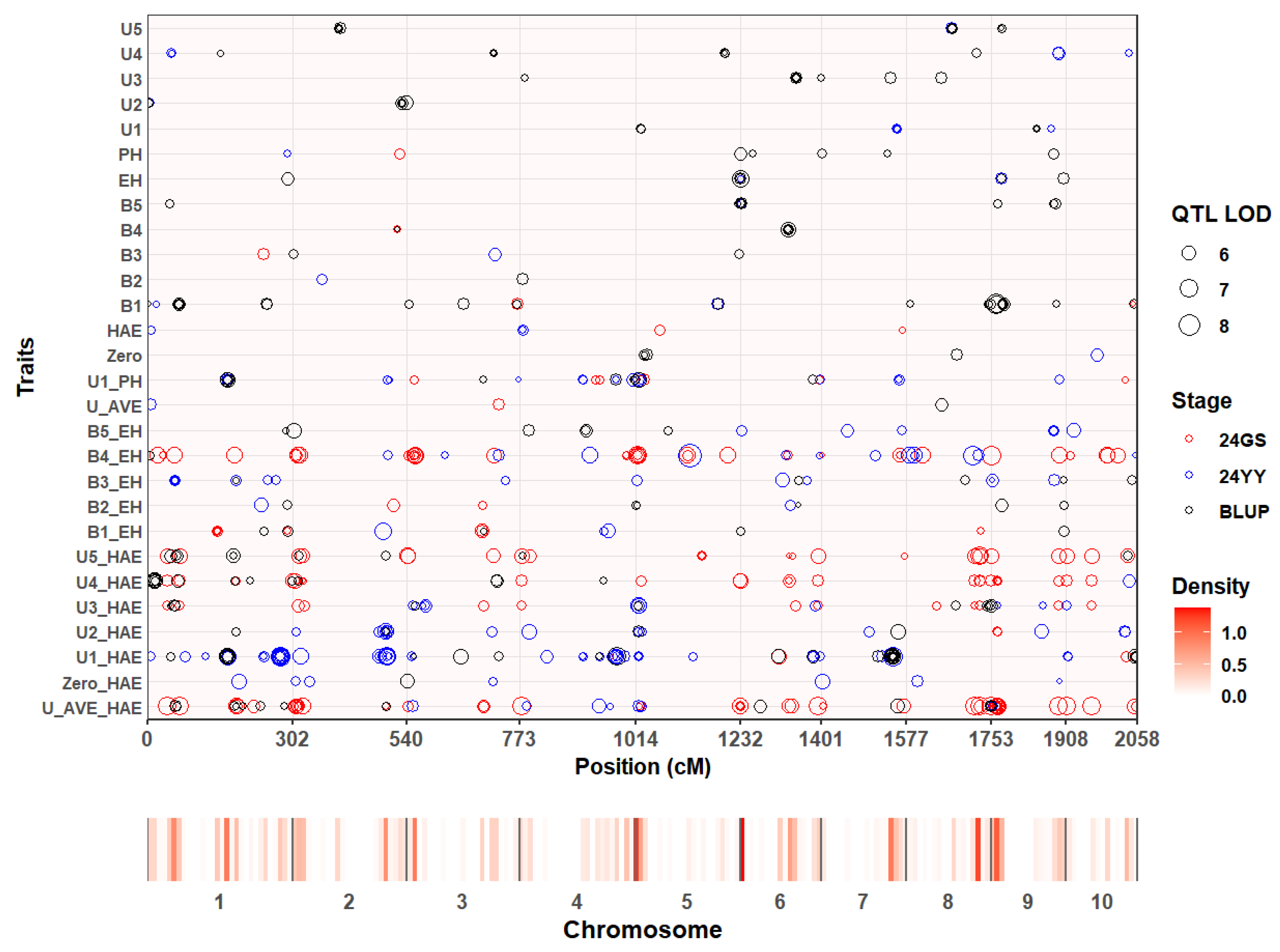

3.2. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Internode-Related Traits

We performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on maize internode length (IL) and internode-ratio traits using approximately 1.25 million SNP markers and the Q + K mixed linear model. Analyses were conducted separately for each of the two environments (24GS and 24YY) and for across-environment best linear unbiased predictions (BLUP) (Supplementary

Figures S5–S8;

Supplementary Table S1). After accounting for population structure and kinship, 821 SNPs exceeded the significance threshold of −log₁₀(

p) > 5.0 (

p < 1 × 10⁻⁵). These SNPs were grouped into 417 non-redundant quantitative trait loci (QTL) based on a 50-kb linkage-disequilibrium (LD) window. QTL were distributed across all ten maize chromosomes, with notable enrichment on chromosomes 1, 2, 5, and 7 (

Figure 1). Among all the identified QTL, 13 stable QTL were screened through colocalization analysis across at least two environments, and these QTL intervals contained a total of 60 internode-related candidate genes (

Supplementary Table S2). These associated regions provide a foundation for subsequent candidate-gene identification related to internode proportion.

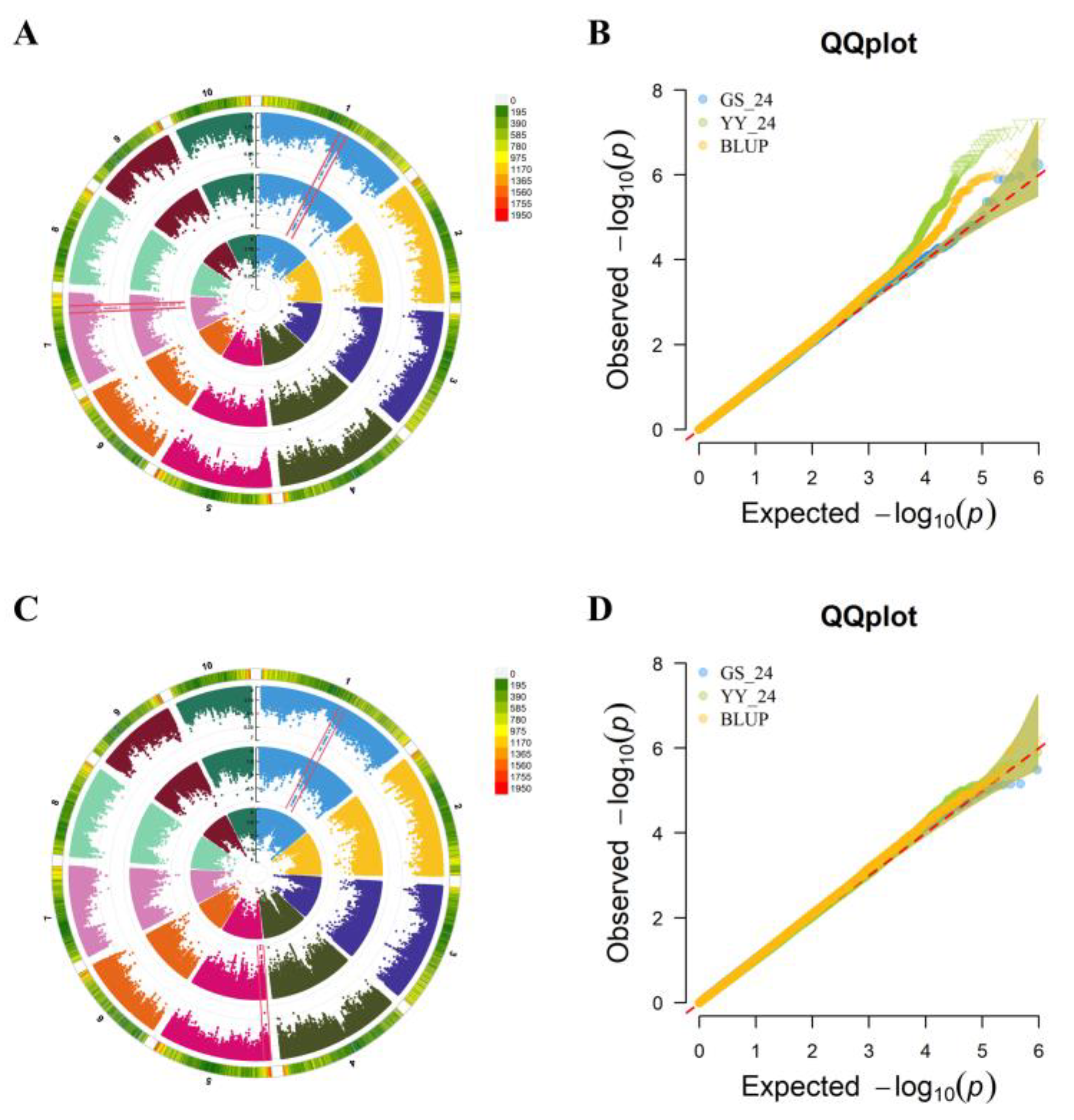

To further dissect the genetic basis of the first-internode proportion in shaping above-ear architecture, we focused GWAS on the traits U1/HAE and U1/PH. For U1/HAE, 128 significant SNPs were detected across environments and BLUP (−log₁₀(

p) > 5.0). Based on the population LD decay distance (~50 kb), these SNPs defined 44 QTL, distributed on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10. Integration of signals from the 24YY environment and the BLUP dataset revealed two consistently detected, stable QTL:

qU1 (chr1: 165.32–165.52 Mb) and

qU2 (chr7: 148.32–148.51 Mb) (

Figure 2A-B). For U1/PH, 37 significant SNPs were identified, corresponding to 27 QTL located on all chromosomes except chromosome 8. Through combined analysis of the 24YY environment and BLUP data, two stable QTL were consistently mapped:

qU3 (chr1: 165.38–165.52 Mb) and

qU4 (chr5: 6.71–6.81 Mb) (

Figure 2C-D). The repeated detection of these QTL across independent datasets indicates that they represent genomic regions with stable genetic effects on internode proportion.

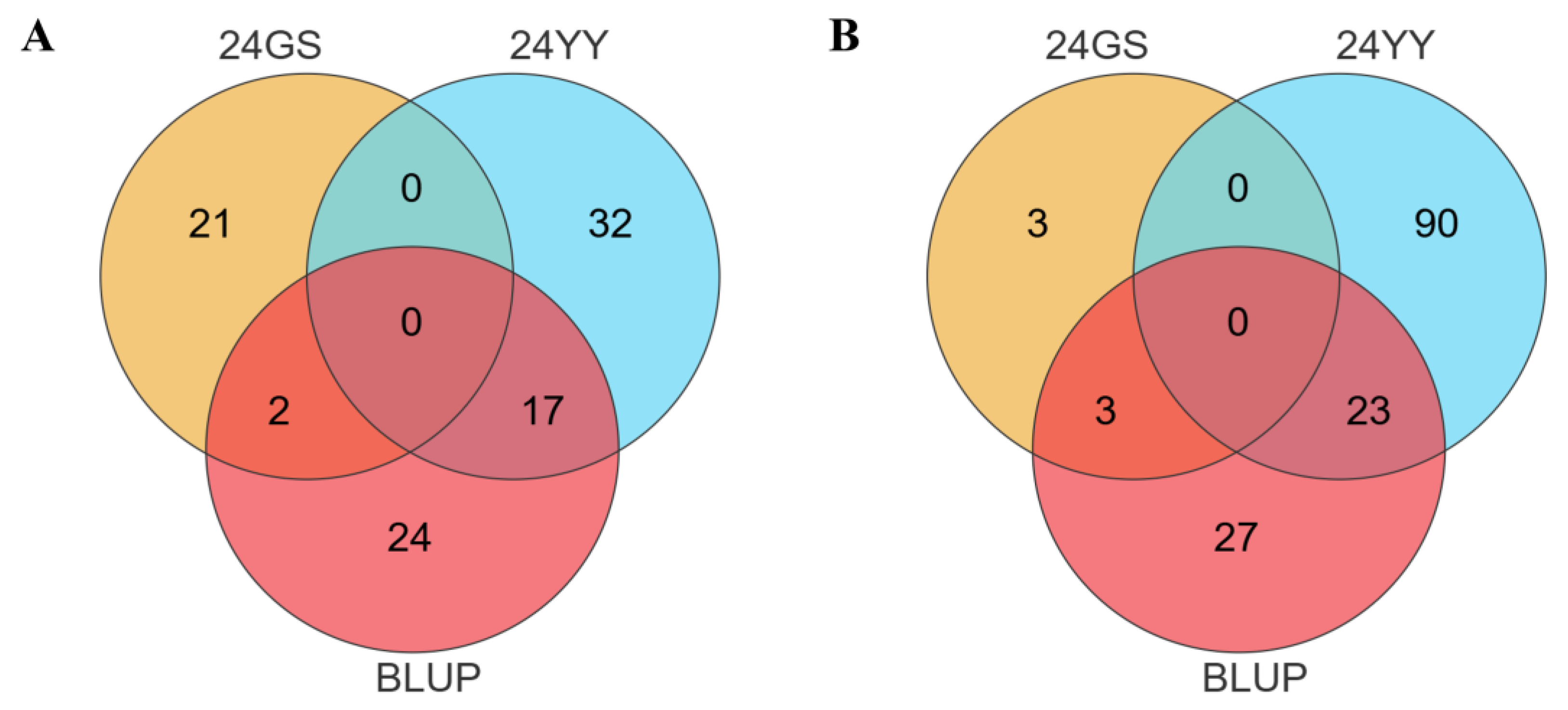

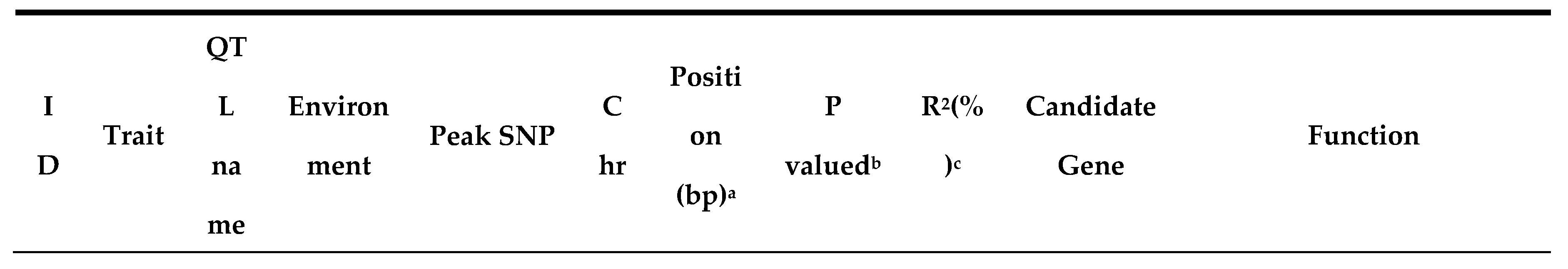

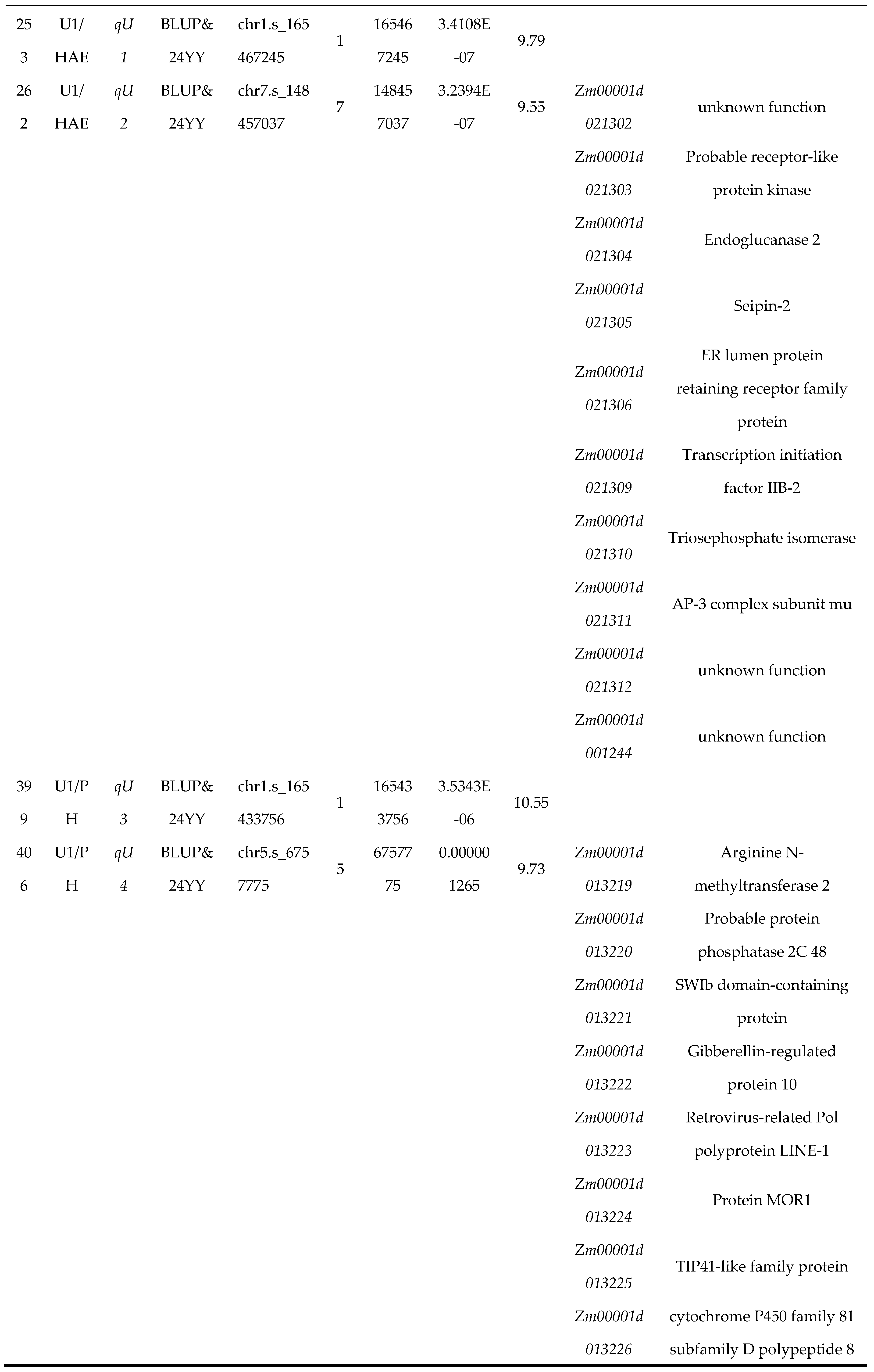

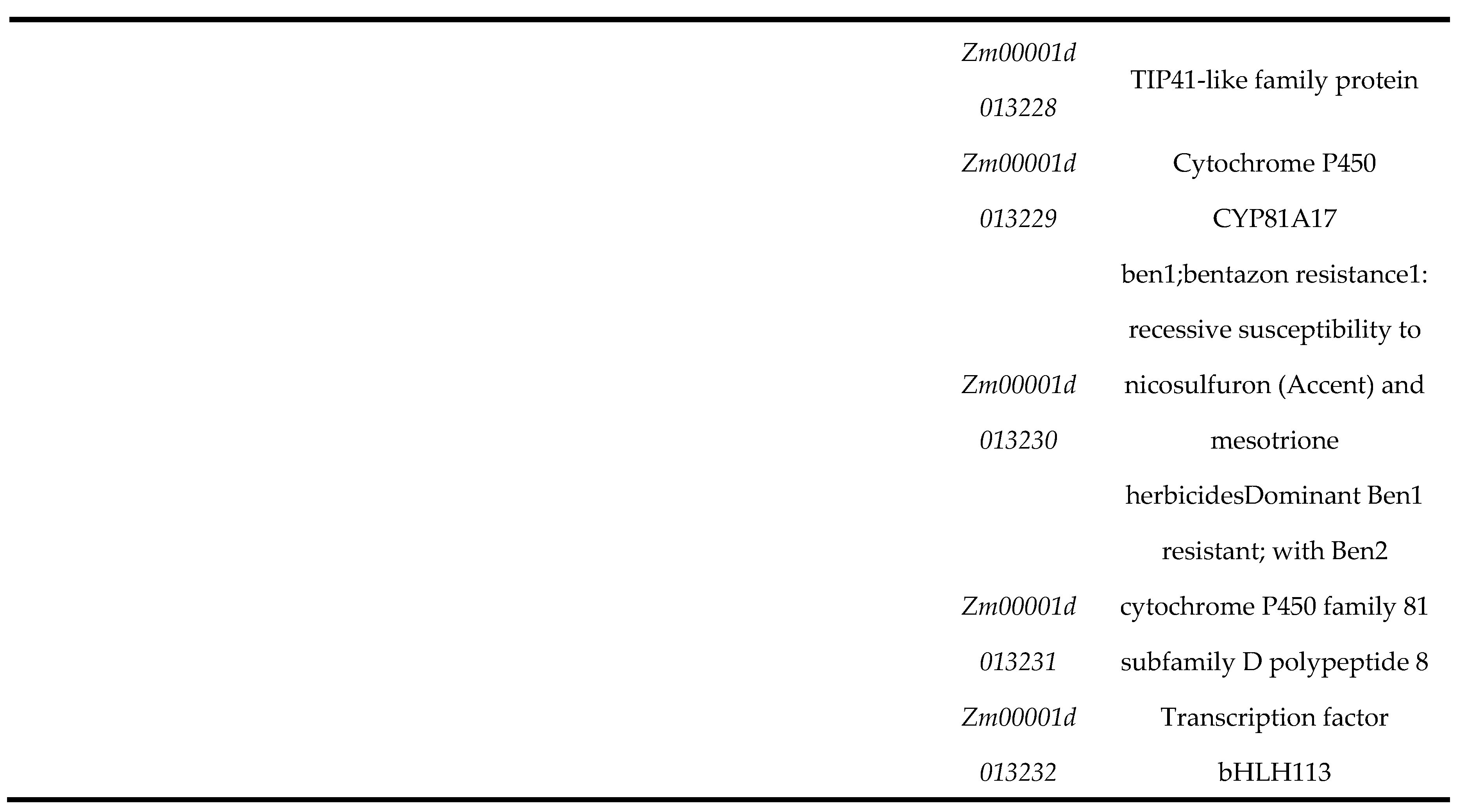

3.3. Analysis of Candidate Genes for U1/HAE and U1/PH Traits

To identify candidate genes underlying U1/HAE and U1/PH, we performed colocalization analysis using phenotypic data from both individual environments and their BLUP . For U1/HAE, 23 genes were consistently identified between the 24YY environment and BLUP, and three genes overlapped between 24GS and BLUP (

Figure 3A). For U1/PH, 17 genes overlapped in the 24YY-BLUP comparison, and two genes were shared between 24GS and BLUP (

Figure 3B). Based on peak SNPs from Manhattan plots, we further screened candidate genes within the stable QTL intervals

qU1,

qU2,

qU3 and

qU4 (

Table 2). No annotated genes were found in the

qU1 and

qU3 regions. Within the

qU2 interval (chr7: 148.32–148.51 Mb), ten candidate genes were identified, including the receptor-like protein kinase

Zm00001d021303 (putatively involved in cell signaling), endoglucanase 2

Zm00001d021304 (associated with cell-wall polysaccharide degradation), endoplasmic-reticulum lumen protein-retention receptor family protein

Zm00001d021306, and triosephosphate isomerase

Zm00001d021310 (implicated in glycolytic metabolism). The

qU4 interval (chr5: 6.71–6.81 Mb) contained thirteen candidate genes, such as gibberellin-regulated protein 10

Zm00001d013222 (a growth-related regulator), the microtubule-associated protein

Zm00001d013224 (

MOR1), the transcription factor

Zm00001d013232 (

bHLH113), and arginine N-methyltransferase 2

Zm00001d013219, along with several genes of unknown function. These candidate genes are significantly associated with the proportional traits of the first internode and are implicated in diverse biological processes, including hormone response, cell-wall dynamics, signal transduction, and metabolic regulation. Their identification provides a functional roadmap for further elucidation of the genetic networks controlling maize internode proportion and plant architecture.

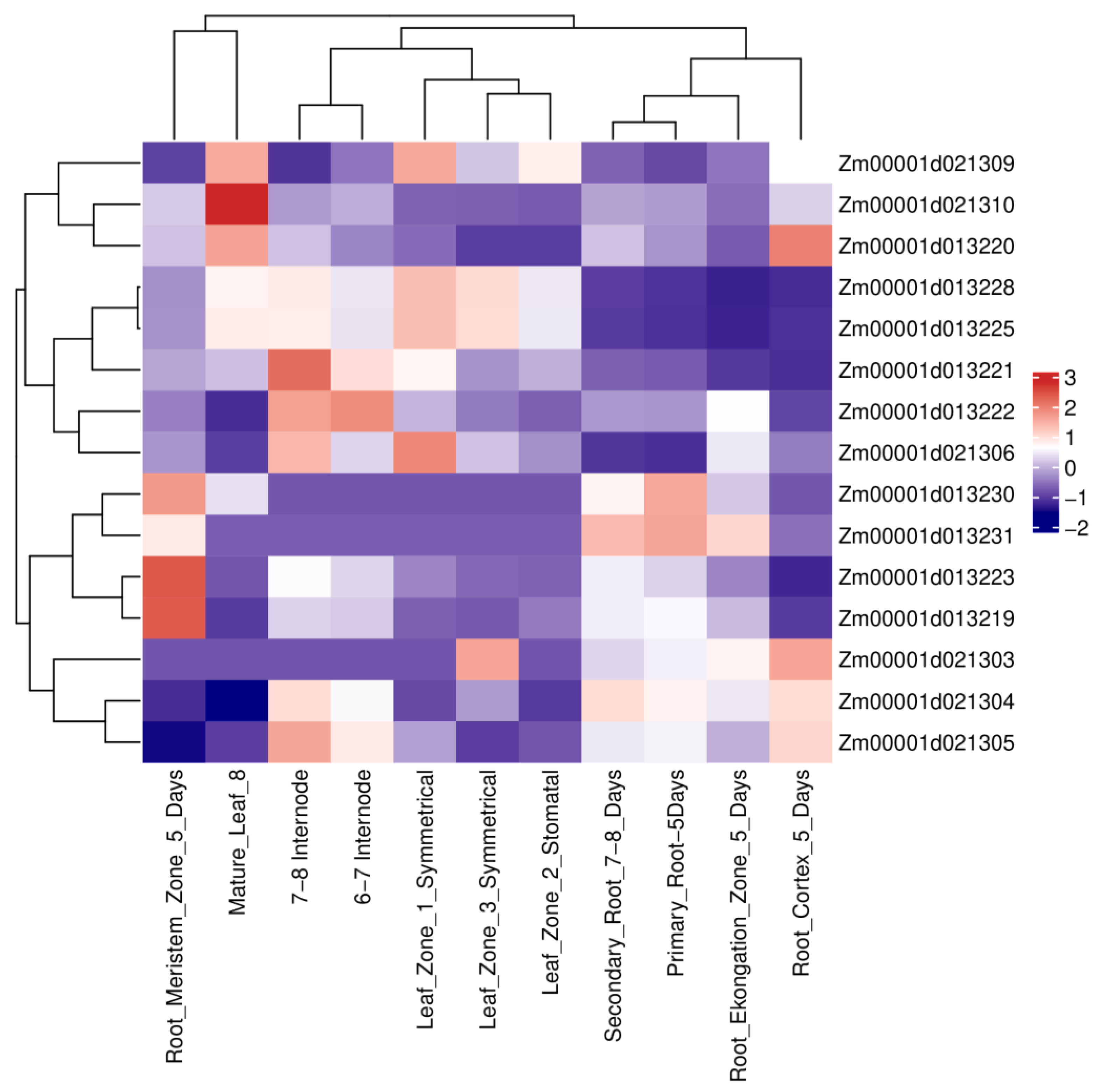

3.4. Expression Profiling and Haplotype Analysis of Key Candidate Genes

To evaluate the biological relevance of candidate genes underlying U1/HAE and U1/PH, we examined their expression patterns using publicly available transcriptome data (

Figure 4). Among the 23 genes located in colocalized intervals,

Zm00001d021304 (encoding endoglucanase 2),

Zm00001d013221 (a domain-containing protein),

Zm00001d013222 (gibberellin-stimulated-like 10), and

Zm00001d013223 (retrovirus-related Pol polyprotein) displayed notably higher expression in roots, stems, and leaves relative to other candidates, supporting their potential roles in vegetative growth and development.

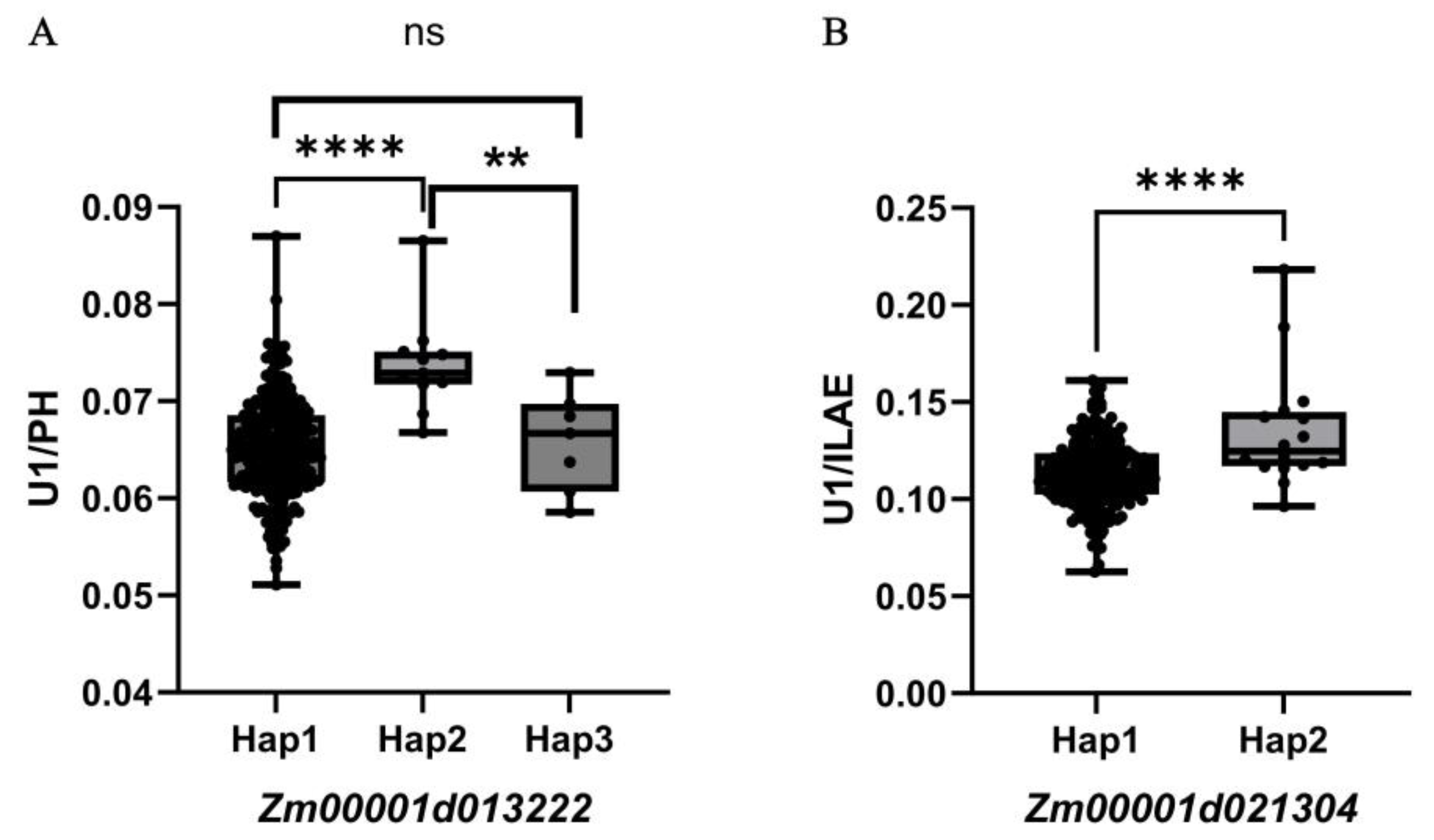

Given that internode elongation is coordinately regulated by multiple hormones, we focused on two functionally annotated genes:

Zm00001d013222, implicated in gibberellin signaling [

23] , and

Zm00001d021304, involved in cell-wall remodeling [

24]. Using BLUP phenotypes from both environments, we performed haplotype-based association analysis for these genes (

Figure 5,

Table 3 and

Table 4). For

Zm00001d013222, three haplotypes were identified, Hap1 (ATACAC), Hap2 (GCGAGG) and Hap3 (ATACAG), Hap1 and Hap3 did not differ significantly in U1/PH, but both produced significantly lower U1/PH values than Hap2 (

p < 0.01). This haplotype-dependent phenotypic variation supports

Zm00001d013222 as a candidate regulator of U1/PH. For

Zm00001d021304, two haplotypes were found, Hap1 (GGTA) and Hap2 (TTAG), Hap2 exhibited a significantly higher U1/HAE value compared to Hap1 (P < 0.001), confirming

Zm00001d021304 as a strong candidate for U1/HAE. These results highlight

Zm00001d013222 and

Zm00001d021304 as promising genetic determinants of internode proportion, operating through hormone-mediated growth regulation and cell-wall dynamics, respectively.

4. Discussion

Currently, with increasing demands for high-density planting in agriculture, maize production faces emerging challenges such as greater lodging susceptibility, highlighting an urgent need for moderately dwarf hybrid maize varieties [

25]. The maize “smart plant architecture” gene lac1, encoding a brassinosteroid C-22 hydroxylase, regulates upper leaf angle [

26]. Key QTL controlling compact plant architecture in maize (

UPA1/

brd1,

UPA2/

RAVL1) have been successfully cloned, and the introgression of teosinte ligule alleles has been used to modify plant architecture. These improvements reduce resource competition under dense planting and significantly increase maize yield under high-density conditions [

27]. In the present study, the ratios of U1 to HAE and to PH remained stable across two environments and BLUP values, and were significantly higher than those of the other upper internodes. This suggests that modulating the U1 proportion could reduce redundant growth of the upper internodes without altering overall plant height. For example, a moderate reduction in the U1 ratio may shorten the first internode above the ear, lower the plant’s center of gravity, and thereby decrease stalk lodging risk. Previous studies have frequently identified the first internode above the ear as a critical site prone to breakage during stalk failure [

14,

15]. Moreover, the “U1/HAE” and “U1/PH” ratios represent more stable genetic traits than individual phenotypic measurements. In summary, by focusing on U1-ratio traits, this study not only enriches the genetic understanding of maize plant architecture regulation but also provides directly applicable resources for lodging-resistance breeding through the identification of stable QTL and candidate genes.

Maize internode elongation is coordinately regulated by multiple hormonal pathways. Transcription factors such as

ZmABI7 and

ZmMYB117 directly bind to the promoters of target genes (

ZmCYC1,

ZmCYC3,

ZmCYC7 and

ZmCPP1) to modulate cell-cycle progression and cell-wall modification, thereby influencing internode development [

28]. Gibberellin (GA) shapes maize stem morphology by regulating peroxidase activity and thus cell-wall lignification [

29]. In rice,

ACE1, encodes a protein of unknown function that confers cell-division capacity in the intercalary meristem, leading to GA-dependent internode elongation [

30]. Another rice gene,

PINE1, encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor that reduces stem sensitivity to GA; the floral meristem enhances stem responsiveness to GA by down-regulating PINE1 expression [

31]. These studies collectively underscore the pivotal role of plant hormones, particularly GA, in internode development. Consistently, among our co-localized candidate genes,

Zm00001d013222 encodes a gibberellin-regulated protein 10 (GSL10), which has been implicated in growth and developmental regulation [

32]. Based on its functional annotation, we propose that

Zm00001d013222 is a key candidate gene regulating the U1/PH trait in this study, likely affecting stem growth and development by modulating gibberellin synthesis or metabolism in maize stems, ultimately leading to alterations in stem morphology.

During stem growth and development, the vascular cambium continuously proliferates, producing new cells. Xylem, which conducts water, differentiates inward from the cambium, while phloem-the main conduit for photoassimilate transport-differentiates outward. The completion of cell division relies on the precise assembly of a new cell wall between daughter cells [

33]. Cellulose microfibrils are crucial for the structural organization of plant cell walls, allowing plants to sustain turgor-driven growth habits [

34]. Endo-1,4-β-D-glucanases (EGases) are also speculated to function in cell expansion. Although their roles in cell-wall synthesis and remodeling are not fully resolved, these enzymes cleave β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in polysaccharides such as cellulose and xyloglucan [

35]. Together, these reports highlight the central importance of the cell wall in stem growth, development, and morphogenesis. In our study,

Zm00001d021304 (

EG2), a candidate gene co-localized with U1/HAE, encodes an endoglucanase belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 9 (GH9; also termed cellulase). It participates in multiple key processes of cell-wall metabolism in higher plants, including the regulation of cellulose biosynthesis and degradation, modification of other (1,4)-β-glucan-containing wall polysaccharides, and mediation of cell-wall loosening during cell elongation [

24]. Analysis of

EG2 expression profiles using the qTeller MaizeGDB platform (

https://qteller.maizegdb.org) revealed that its expression peaked 24 days before pollination and remained relatively stable during other periods, suggesting involvement in the stem-jointing stage of maize.

EG2 may promote the degradation of cell-wall polysaccharides to maintain wall plasticity, thereby facilitating stem elongation. Notably, the previously reported

stiff1 gene enhances stalk strength and lodging resistance by negatively regulating cellulose and lignin synthesis and influencing cell-wall thickness [

36]. This gene may act synergistically with

EG2 identified here to achieve a dynamic balance between “internode-proportion optimization” and “stem-strength enhancement” a core objective in lodging-resistant plant-architecture breeding.

4. Conclusion

Through a GWAS approach in a diverse maize panel, we identified stable QTL (qU1–qU4) and candidate genes governing the proportion of the first internode above the ear. Two functionally annotated genes, Zm00001d013222 (involved in gibberellin signaling) and Zm00001d021304 (a cell wall-modifying endoglucanase), exhibited significant haplotype-based associations with U1/PH and U1/HAE, respectively. These findings highlight the coordinated roles of hormone pathways and cell wall metabolism in shaping maize internode architecture. The stability of these loci across environments underscores their potential value for molecular breeding. This study provides novel genetic insights and precise targets for improving plant architecture and lodging resistance, supporting the development of high-yield maize varieties optimized for modern high-density cropping systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

D.D, J.H.T and X.H.Z designed the study. D.D and X.H.Z supervised the study. H.Z, X.Q.Q, H.L.X Y.H.Z and Z.B.D performed the experiments. X.Y.L, H.Z, K.Y.W, Q.K.X, G.M.G, X.Y.C and H.Y.C analyzed the data. X.Y.L, Q.K.X and X.H.Z wrote the manuscript, D.D and X.H.Z revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32272166, U21A20210), Natural Science Outstanding Youth Fund of Henan Province (252300421036), the Key research and development projects of Henan Province (251111111000), the Joint Foundation for Science and Technology Research and Development Program of Henan Province (242301420131), the Henan Province Science and Technology Attack Project, China (242102110307, 232102111108).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included. within the article (and its supplementary files). Genotypic data can be downloaded from http: //

www.maizego.org/Resources.html.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Jianbing Yan at Huazhong Agricultural University for providing the maize association mapping panel and genotype data.

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li Q, Song X, Meng X, et al. Shaping future sugarcane: Ideal plant architecture and breeding strategies[J]. Mol Plant, 2025,18(5):725-728.

- Wen W, Gu S, Xiao B, et al. In situ evaluation of stalk lodging resistance for different maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars using a mobile wind machine[J]. Plant Methods, 2019,15:96.

- Multani D S, Briggs S P, Chamberlin M A, et al. Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants[J]. Science, 2003,302(5642):81-84.

- Wei L, Zhang X, Zhang Z, et al. A new allele of the Brachytic2 gene in maize can efficiently modify plant architecture[J]. Heredity (Edinb), 2018,121(1):75-86.

- Zhang D, Sun W, Singh R, et al. GRF-interacting factor1 Regulates Shoot Architecture and Meristem Determinacy in Maize[J]. Plant Cell, 2018,30(2):360-374.

- Tsuda K, Abraham-Juarez M, Maeno A, et al. KNOTTED1 Cofactors, BLH12 and BLH14, Regulate Internode Patterning and Vein Anastomosis in Maize[J]. Plant Cell, 2017,29(5):1105-1118.

- Depuydt S, Hardtke C S. Hormone signalling crosstalk in plant growth regulation[J]. Curr Biol , 2011,21(9):R365-R373.

- Zhao J, Yuan B, Zhang H, et al. Phenotypic characterization and genetic mapping of the semi-dwarf mutant sdw9 in maize[J]. Theor Appl Genet, 2024,137(11):253.

- Kaur A, Best N B, Hartwig T, et al. A maize semi-dwarf mutant reveals a GRAS transcription factor involved in brassinosteroid signaling[J]. Plant physiol, 2024,195(4):3072-3096.

- Lawit S J, Wych H M, Xu D, et al. Maize DELLA proteins dwarf plant8 and dwarf plant9 as modulators of plant development[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2010,51(11):1854-1868.

- Wang X, Ren Z, Xie S, et al. Jasmonate mimic modulates cell elongation by regulating antagonistic bHLH transcription factors via brassinosteroid signaling[J]. Plant physiol, 2024,195(4):2712-2726.

- Li H, Wang L, Liu M, et al. Maize Plant Architecture Is Regulated by the Ethylene Biosynthetic Gene ZmACS7[J]. Plant physiol, 2020,183(3):1184-1199.

- Guan J C, Koch K E, Suzuki M, et al. Diverse roles of strigolactone signaling in maize architecture and the uncoupling of a branching-specific subnetwork[J]. Plant physiol, 2012,160(3):1303-1317.

- Wang X, Zhang R, Shi Z, et al. Multi-omics analysis of the development and fracture resistance for maize internode[J]. Sci Rep, 2019,9(1):8183.

- Wang X, Shi Z, Zhang R, et al. Stalk architecture, cell wall composition, and QTL underlying high stalk flexibility for improved lodging resistance in maize[J]. BMC Plant Biol, 2020,20(1):515.

- Le L, Guo W, Du D, et al. A spatiotemporal transcriptomic network dynamically modulates stalk development in maize[J]. Plant Biotechnol J, 2022,20(12):2313-2331.

- Wang F, Yu Z, Zhang M, et al. ZmTE1 promotes plant height by regulating intercalary meristem formation and internode cell elongation in maize[J]. Plant Biotechnol J, 2022,20(3):526-537.

- Duan H, Li J, Xue Z, et al. Genetic dissection of internode length confers improvement for ideal plant architecture in maize[J]. Plant J, 2025,121(3):e17245.

- Liu H, Wang F, Xiao Y, et al. MODEM: multi-omics data envelopment and mining in maize[J]. Database (Oxford), 2016,2016:baw117.

- Browning S R, Browning B L. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing-data inference for whole-genome association studies by use of localized haplotype clustering[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2007,81(5):1084-1097.

- Liu H, Luo X, Niu L, et al. Distant eQTLs and Non-coding Sequences Play Critical Roles in Regulating Gene Expression and Quantitative Trait Variation in Maize[J]. Mol Plant, 2017,10(3):414-426.

- Li H, Peng Z, Yang X, et al. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels[J]. Nat Genet, 2013,45(1):43-50.

- Zimmermann R, Sakai H, Hochholdinger F. The Gibberellic Acid Stimulated-Like gene family in maize and its role in lateral root development[J]. Plant physiol, 2010,152(1):356-365.

- Buchanan M, Burton R A, Dhugga K S, et al. Endo-(1,4)-β-glucanase gene families in the grasses: temporal and spatial co-transcription of orthologous genes[J]. BMC Plant Biol, 2012,12:235.

- Xiao S, Song W, Wang R, et al. Reinventing a sustainable Green Revolution by breeding and planting semi-dwarf maize[J]. Mol Plant, 2025,18(10):1626-1642.

- Tian J, Wang C, Chen F, et al. Maize smart-canopy architecture enhances yield at high densities[J]. Nature, 2024,632(8025):576-584.

- Tian J, Wang C, Xia J, et al. Teosinte ligule allele narrows plant architecture and enhances high-density maize yields[J]. Science, 2019,365(6454):658-664.

- Ren Z, Liu Y, Li L, et al. Deciphering transcriptional mechanisms of maize internodal elongation by regulatory network analysis[J]. J Exp Bot, 2023,74(15):4503-4519.

- de Souza I R, MacAdam J W. Gibberellic acid and dwarfism effects on the growth dynamics of B73 maize (Zea mays L.) leaf blades: a transient increase in apoplastic peroxidase activity precedes cessation of cell elongation[J]. J Exp Bot, 2001,52(361):1673-1682.

- Nagai K, Mori Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Antagonistic regulation of the gibberellic acid response during stem growth in rice[J]. Nature, 2020,584(7819):109-114.

- Gómez-Ariza J, Brambilla V, Vicentini G, et al. A transcription factor coordinating internode elongation and photoperiodic signals in rice[J]. Nat Plants, 2019,5(4):358-362.

- Niu L, Du C, Wang W, et al. Transcriptome and co-expression network analyses of key genes and pathways associated with differential abscisic acid accumulation during maize seed maturation[J]. BMC Plant Biol, 2022,22(1):359.

- Glass M, Barkwill S, Unda F, et al. Endo-β-1,4-glucanases impact plant cell wall development by influencing cellulose crystallization[J]. J Integr Plant Biol, 2015,57(4):396-410.

- Somerville C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants[J]. Annual review of cell and developmental biology, 2006,22:53-78.

- Lopez-Casado G, Urbanowicz B R, Damasceno C M B, et al. Plant glycosyl hydrolases and biofuels: a natural marriage[J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2008,11(3):329-337.

- Zhang Z, Zhang X, Lin Z, et al. A Large Transposon Insertion in the stiff1 Promoter Increases Stalk Strength in Maize[J]. Plant Cell, 2020,32(1):152-165.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).