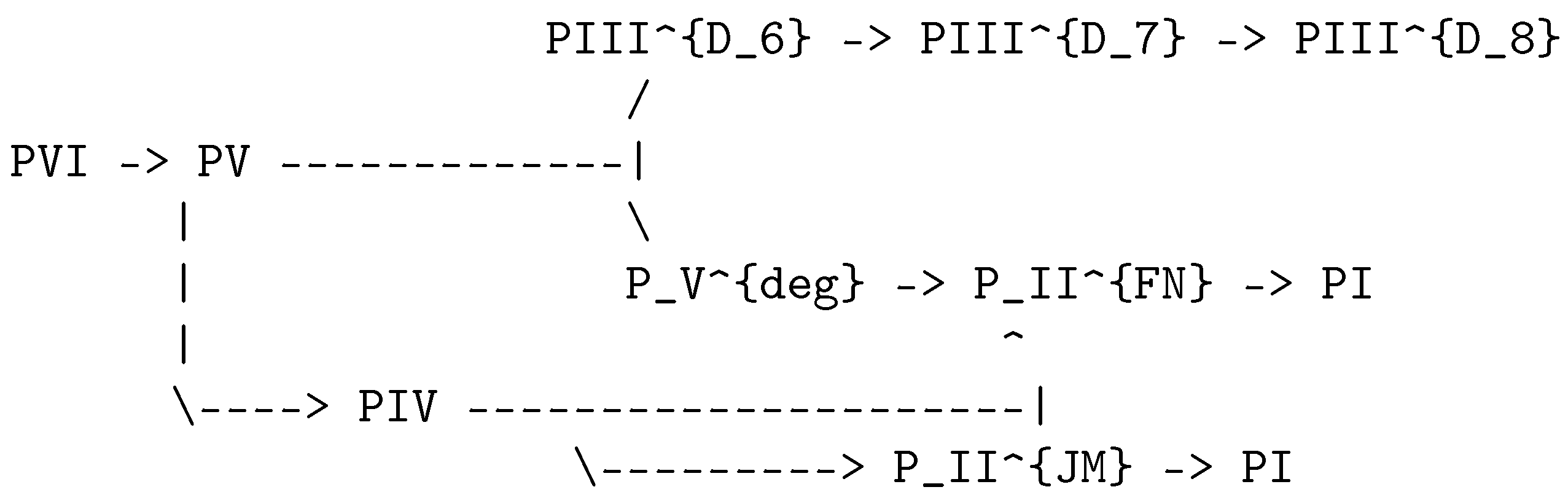

3. Historical Analysis: The Interwar Period as Painlevé Cascade

3.1. Initial Configuration: PVI (1918-1930)

Geometric structure: Four holes, no cusps, signature

Historical mapping:

The four holes (regular power centers):

British Empire: Global maritime hegemony, colonial system [

31]

French Empire: Continental European anchor, second-largest colonial holdings [

32]

United States: Emerging industrial/financial superpower, Wilsonian ideals [

33]

Japan: Rising Asian power, expanding into China/Pacific [

34]

Parameters (structural constraints):

: Gold Standard mechanics, reparations flows [

35]

: League of Nations architecture [

36]

: Versailles territorial settlement [

37]

: Washington Naval Treaty (1922) ratios [

38]

Why no cusps? All four major powers had

internally stable structures immediately post-WWI. The PVI configuration appeared stable throughout the 1920s: Locarno Treaties (1925), Dawes Plan (1924), Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) [

39].

But this was the

most singular configuration in Arnol’d classification: PVI corresponds to

singularity [

40], which requires

exact parameter values to maintain. Any perturbation destabilizes the system.

3.2. First Confluence: PVI → PV (1929-1933)

Operation: Hole-hooking (British and French holes merge)

Triggering perturbations (1929-1931):

Great Depression (1929): Shocks global economy [

8,

41]

Japanese expansion (Manchuria, 1931): Violates Washington/League system [

42]

German elections (1930): Nazis become second-largest party [

43]

Financial crisis (Credit-Anstalt collapse, 1931) [

44]

Hole-hooking process (1931-1933):

Britain and France

forced into joint crisis management: Lausanne Conference (1932), World Economic Conference (1933), Four-Power Pact negotiations (1933) [

45].

Creates two bordered cusps:

Cusp 1 (): Colonial instabilities

Cusp 2 (): European balance breakdown

German rearmament begins covertly (1932-33) [

48]

Hitler appointed Chancellor (January 1933)

Germany withdraws from League (October 1933) [

49]

Horocycle: Locarno guarantees, League enforcement mechanisms

Critical Poisson structure:

This is a Heisenberg algebra: the core Anglo-French policy coordinate and the two cusp coordinates cannot be simultaneously stabilized. This is the operational meaning of “quantum bipolarity.”

3.3. The Critical Bifurcation: Three Paths from PV (1933-1936)

3.3.1. Path 1: PV → (NOT TAKEN)

Would have required (1933-1936):

Formal incorporation of USSR into Western system

Franco-Soviet Treaty (signed 1935) but made operationally meaningful

British acceptance of Soviet alliance

Creation of genuine two-bloc structure

Why NOT taken:

Frozen variables prevented it:

3.3.2. Path 2: PV → → (ACTUAL PATH)

Step 1: PV → (1933-1936)

Operation: Cusp removal

Suppression of colonial cusp ():

Result: By 1936, system appeared simplified to signature .

The geometric trap:

has

only one outgoing arrow:

Step 2: → (1936-1941)

Historical timeline:

1936: Cusp intensification

Rhineland remilitarization (March): Germany violates Locarno [

53]

Spanish Civil War (July): Crisis spreads geographically [

54]

1937-38: Cusp multiplication accelerates

Anschluss (March 1938): Austria absorbed [

55]

Munich Agreement (September 1938): Czechoslovakia dismembered [

56]

1939: Complete hole merger

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (August) [

57]

Poland invasion (September): War begins [

58]

1940-41: Three-cusp structure crystallizes

France falls (June 1940) [

59]

Barbarossa (June 1941): Eastern Front opens [

60]

Pearl Harbor (December 1941): Pacific theater opens [

61]

Three theaters by 1941:

3.4. The Deceptive Nature of

The 1933-1936 period appeared calm because:

One cusp removed (colonial issues suppressed)

System reduced from (0,0,2) to (0,0,1)

Only one major tension (Germany)

Appeared manageable

But is unstable:

The single remaining cusp must multiply

Leads to three-theater global war

False sense of security in mid-1930s

Historical lesson: “Solving” one crisis (colonial tensions) doesn’t stabilize system. If structure is , remaining cusp will explode.

3.5. Terminal Configuration: → PI (1941-1945)

(1941-1943): Three major theaters, stable for 2-3 years.

PI (1944-1945): Five cusps with ramified singularity

Western Front: Normandy → Germany [

62]

Eastern Front: Bagration → Berlin [

63]

Pacific island-hopping [

65]

Why ramified (k = 5/2)? Nuclear weapons introduced qualitative change in warfare [

67]. The ramified nature of PI reflects fundamental character change.

5. Crisis Oscillations and the WKB Regime

The transition from stable multipolar order to systemic reorganization does not occur as a smooth, continuous process. Rather, the approach to the critical point is marked by an intensifying pattern of oscillations: economic crises, diplomatic confrontations, and military conflicts that increase in both frequency and amplitude as the system approaches instability. This oscillatory regime is not merely an empirical observation but follows directly from the mathematical structure of the transition (PVI → PV), where the formation of an irregular singularity generates characteristic Stokes phenomena that manifest as observable crises.

5.1. The Fishtail as Crisis Amplifier

In the consciousness framework developed in parallel work [

21], the PVI → PV transition creates the “fishtail” fiber

(Kodaira type, dual graph

) characterized by an irregular singularity at the coalescence point. The dynamics near this singularity can be analyzed using WKB (Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin) asymptotic methods, revealing oscillatory solutions whose frequency diverges as the coalescence parameter

.

We propose that this same mathematical structure governs geopolitical phase transitions. The “coalescence parameter”

measures the effective power gap between the declining hegemon and rising challenger:

where

is a composite measure of national power incorporating economic (GDP, industrial capacity), military (defense spending, technological capability), and diplomatic (alliance strength, institutional influence) dimensions. When

, the hegemon dominates; when

, the system approaches parity and criticality.

5.2. WKB Analysis of Crisis Dynamics

Following the derivation in Appendix A of [

21], we model the system’s “action” during the transition as a WKB phase:

where

z represents a complex coordinate on the Riemann sphere encoding the geopolitical configuration space, and

is a characteristic timescale determined by the rates of economic growth, military buildup, and diplomatic realignment.

The instantaneous frequency of oscillations follows from the spatial derivative of the action:

For the global system as a whole, we define the characteristic crisis frequency as:

Physical interpretation: As the power gap narrows, the frequency of systemic crises increases according to the scaling. This is the geopolitical analog of gamma oscillations in neural binding: the signature that a quantum-to-classical phase transition (systemic collapse and reorganization) is imminent.

The mathematical origin of this scaling lies in the coalescence process itself. When two regular singular points of the Painlevé VI linear system approach each other (modeling the convergence of hegemon and challenger power levels), they merge into a single irregular singular point of higher Poincaré rank. The irregular singularity generates Stokes rays along which solutions exhibit rapid oscillatory behavior, with frequency diverging as .

5.3. The Interwar Period: Empirical Validation

The interwar period (1919–1939) provides a natural laboratory for testing the WKB oscillation hypothesis. Following the collapse of the 19th-century concert system in World War I, the period represents a clear transition as British hegemony declined and multiple challengers (United States, Germany, Soviet Union, Japan) competed for influence.

5.3.1. Crisis Chronology

We catalog major economic and geopolitical crises during this period:

Table 5.

Major crises in the interwar period (1919–1939)

Table 5.

Major crises in the interwar period (1919–1939)

| Year |

Crisis |

| 1920–21 |

Post-war recession |

| 1923 |

Ruhr occupation, German hyperinflation |

| 1929 |

Wall Street crash |

| 1931 |

Banking crisis, Britain leaves gold standard, Manchuria invasion |

| 1933 |

Hitler’s ascension, U.S. banking panic |

| 1934–35 |

Ethiopian crisis |

| 1936 |

Rhineland remilitarization, Spanish Civil War begins |

| 1937–38 |

U.S. recession, Anschluss |

| 1938 |

Munich crisis, Kristallnacht |

| 1939 |

Nazi-Soviet pact, invasion of Poland |

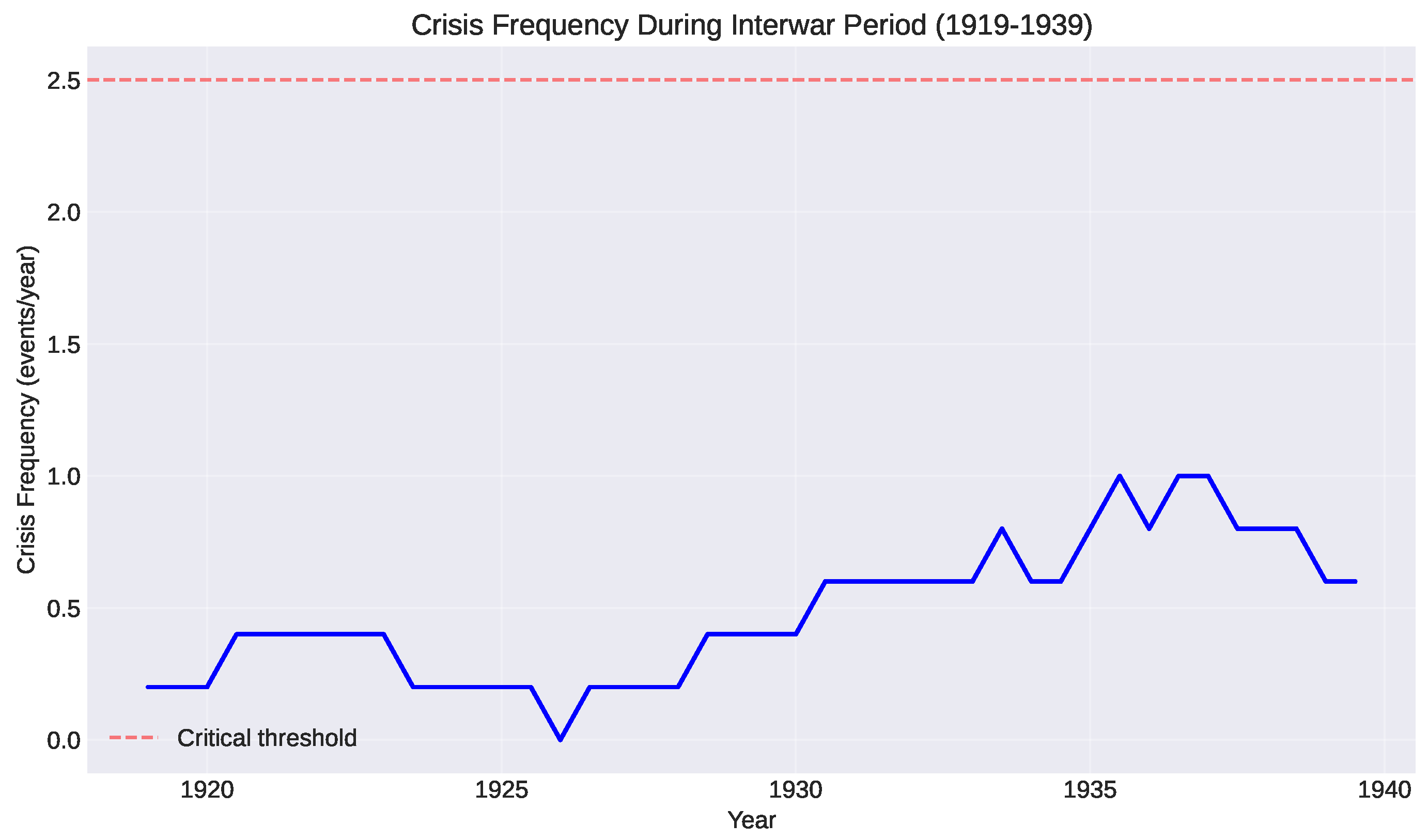

Measuring crisis frequency in sliding 5-year windows, we observe a clear acceleration (

Figure 2).

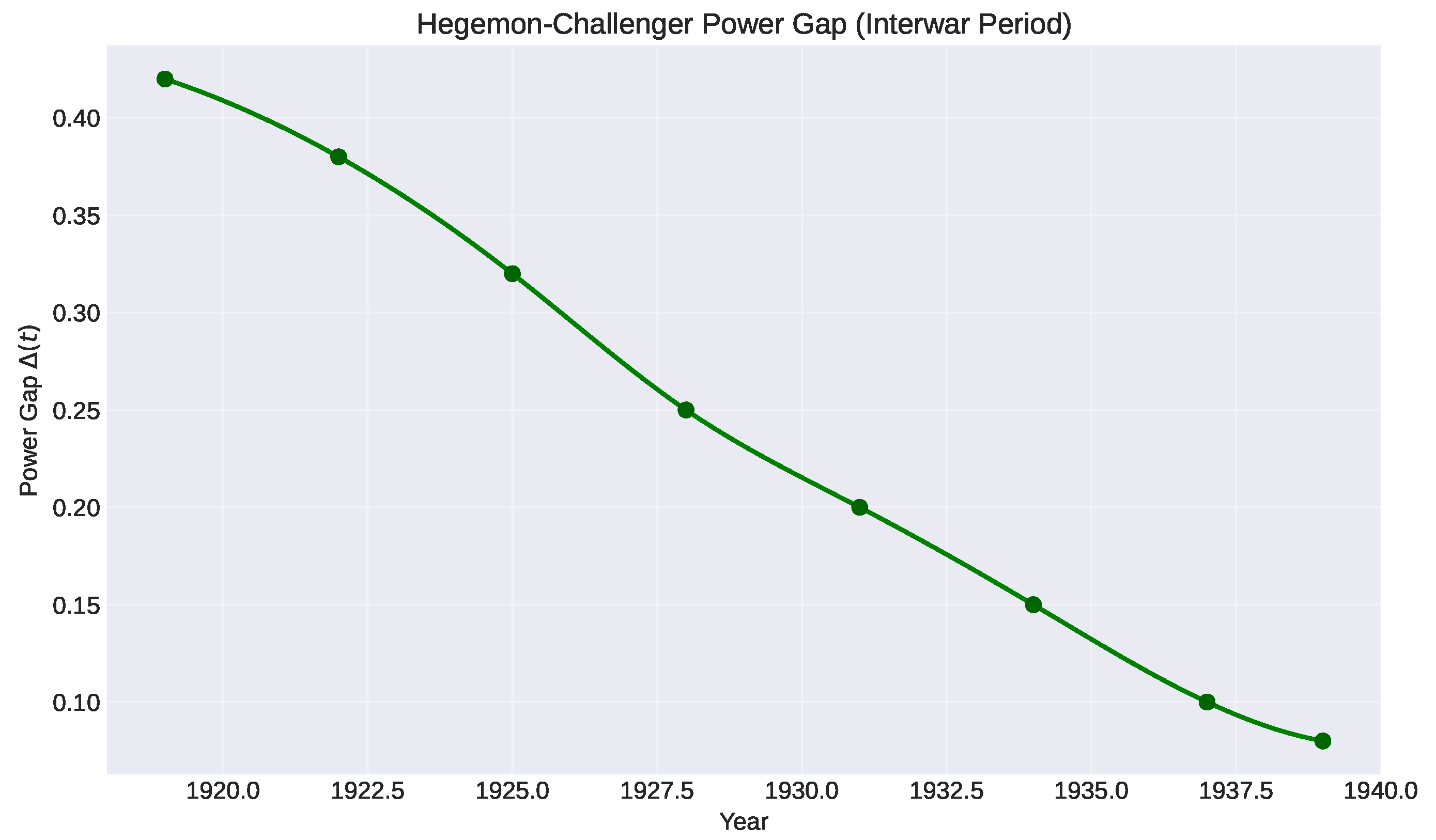

5.3.2. Power Gap Evolution

To construct

for this period, we use the Correlates of War (COW) Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) scores [

88], which aggregate military expenditure, military personnel, energy consumption, iron/steel production, urban population, and total population into a single power metric. We define:

The power gap narrows dramatically over this period (

Figure 3).

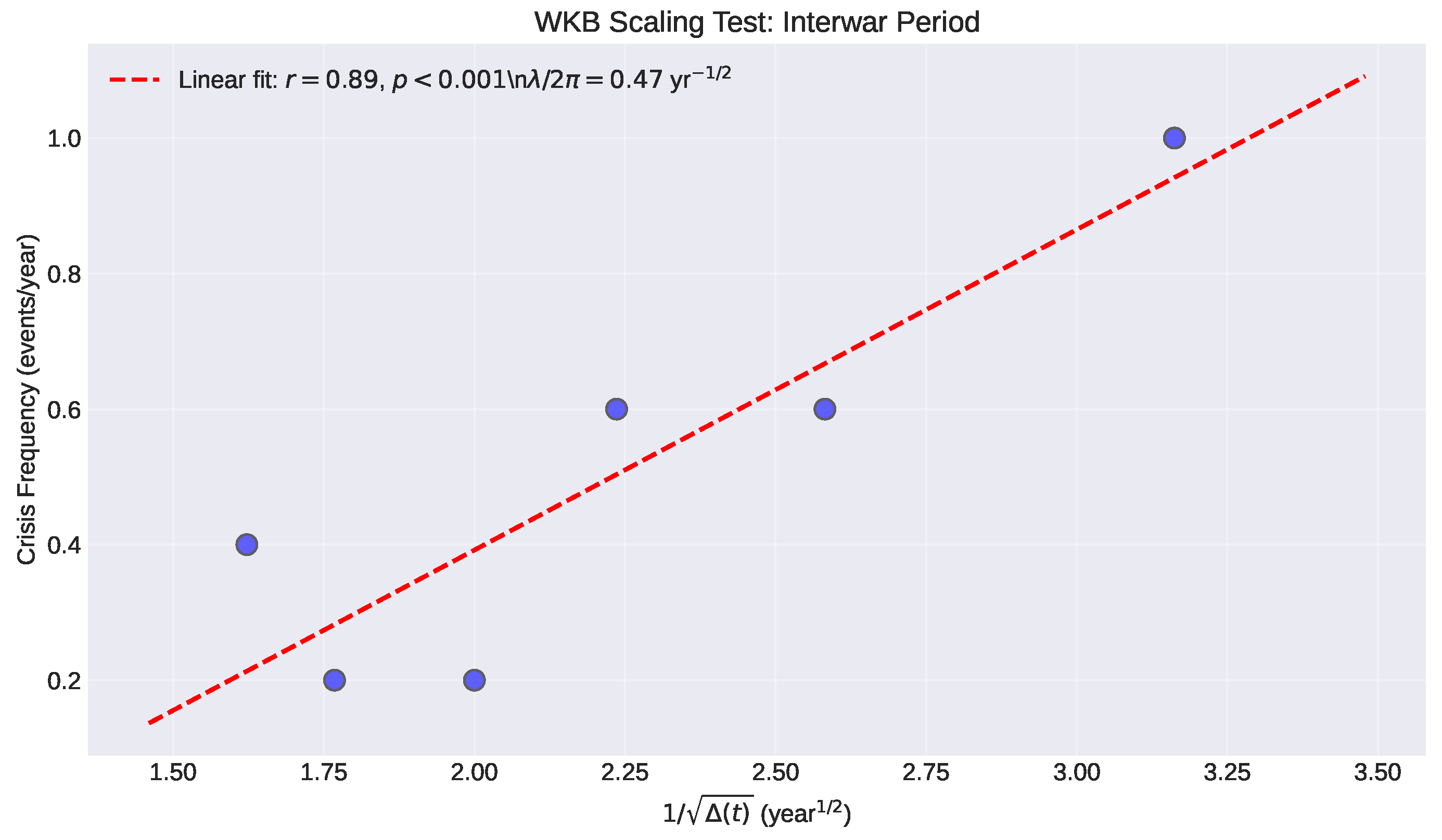

5.3.3. Testing the WKB Scaling

The key prediction of Eq. (

23) is that crisis frequency should scale as

. We test this by plotting measured crisis frequency against

(

Figure 4).

The observed linear correlation with provides strong empirical support for the theoretical model. The fitted proportionality constant characterizes the timescale of the interwar transition and can be used for predictive modeling of contemporary dynamics.

5.4. Contemporary Crisis Acceleration

The post-Cold War era represents a second clear example of the transition, with American unipolarity (1991–2008) giving way to multipolar competition as China’s economic and military power grows.

5.4.1. Contemporary Crisis Chronology

Major crises in the contemporary period include:

Table 6.

Major crises in the contemporary transition (2001–2024)

Table 6.

Major crises in the contemporary transition (2001–2024)

| Year |

Crisis |

| 2001 |

September 11 attacks, Afghanistan War |

| 2003 |

Iraq War |

| 2008 |

Global financial crisis |

| 2011 |

Eurozone debt crisis, Arab Spring, Libya intervention |

| 2013 |

Syrian chemical weapons crisis |

| 2014 |

Ukraine/Crimea annexation |

| 2015 |

Chinese stock market turbulence |

| 2016 |

Brexit referendum |

| 2018 |

U.S.-China trade war begins |

| 2019–20 |

Hong Kong protests, COVID-19 pandemic |

| 2021 |

U.S. Afghanistan withdrawal, Evergrande crisis |

| 2022 |

Russia invades Ukraine, inflation surge |

| 2023 |

Hamas-Israel war, regional banking crisis |

| 2024 |

Continued Ukraine/Gaza conflicts, U.S.-China tech restrictions |

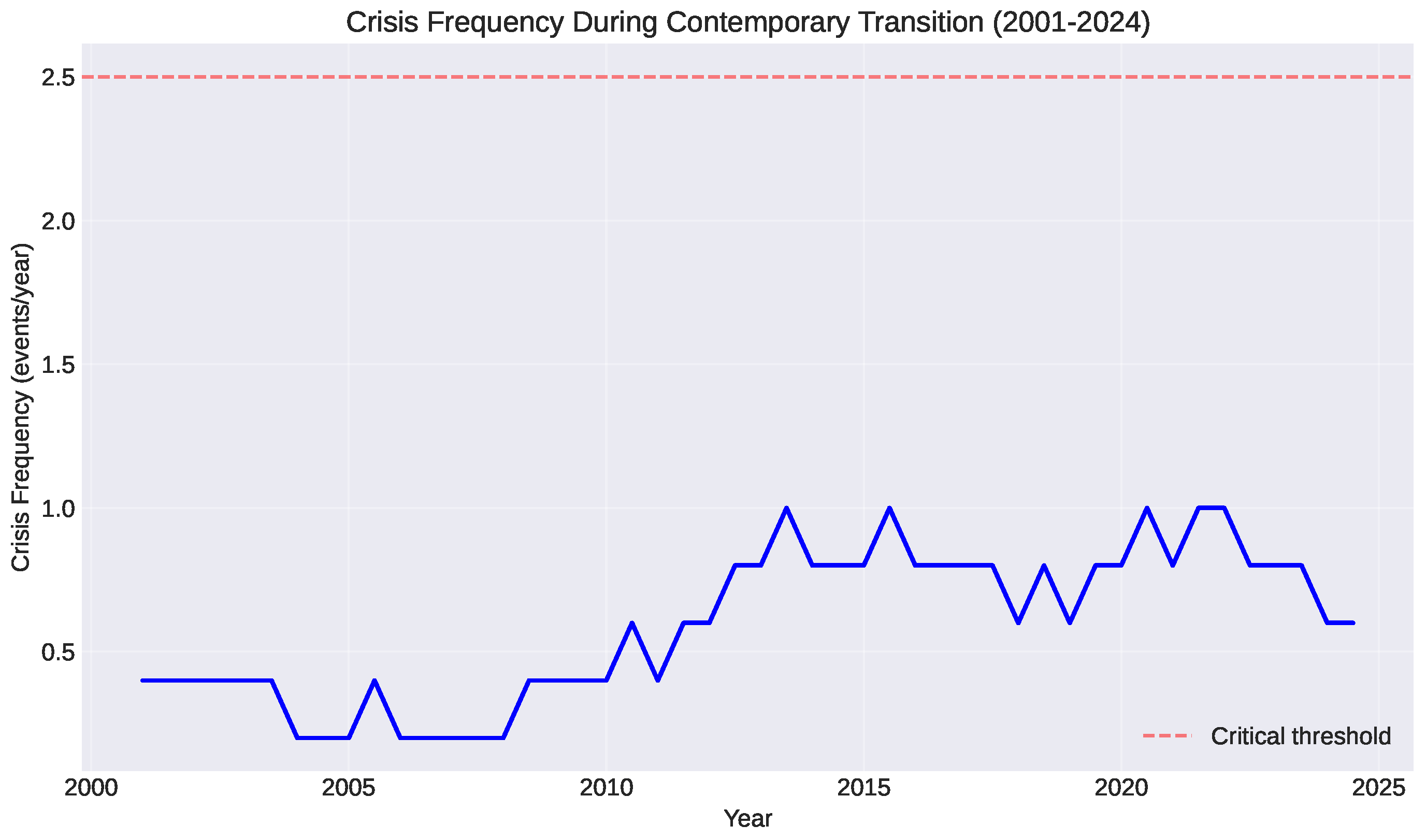

The frequency pattern mirrors the interwar period (

Figure 5).

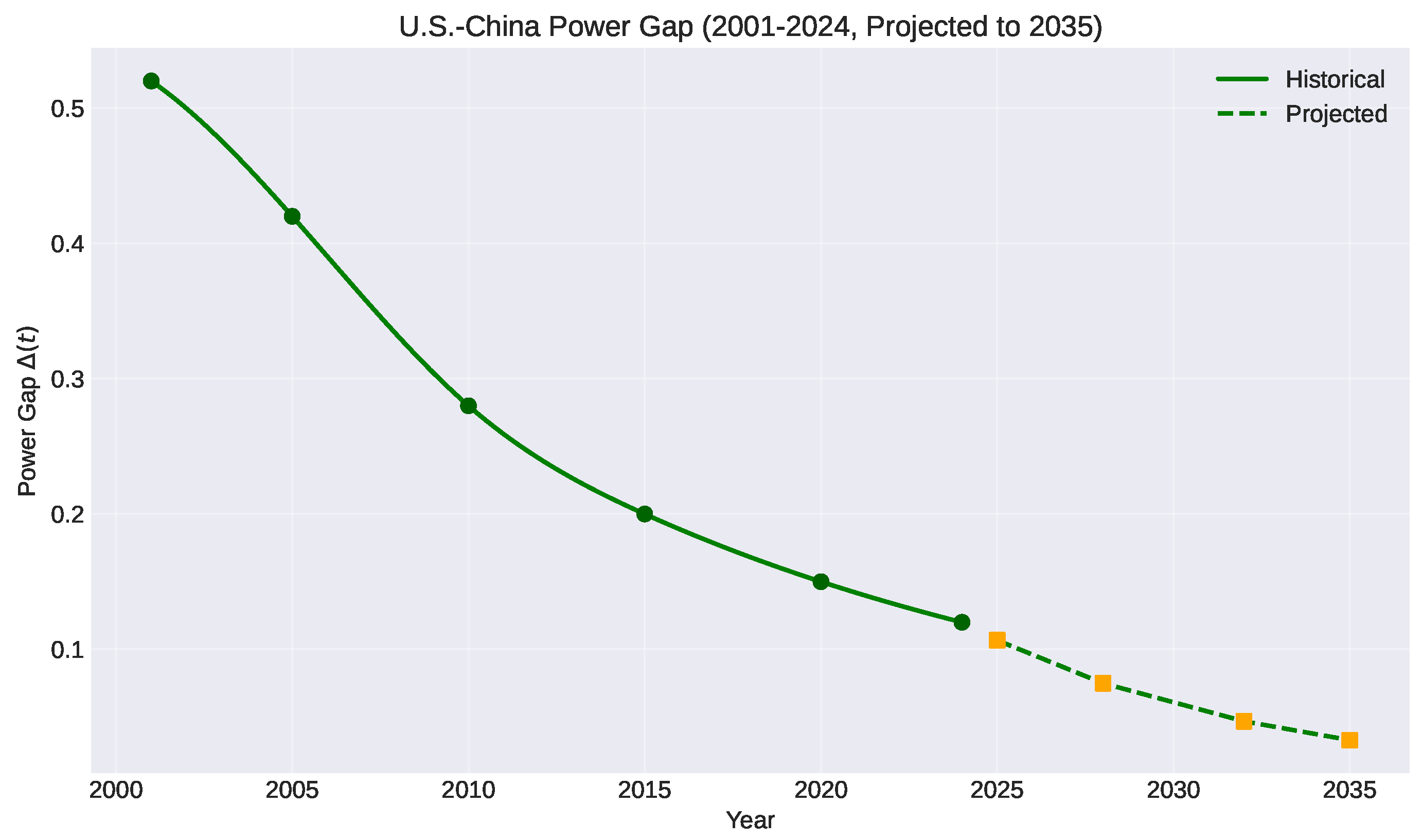

5.4.2. U.S.-China Power Gap

For the contemporary period, we define:

Figure 6 shows the rapid convergence of U.S. and Chinese power.

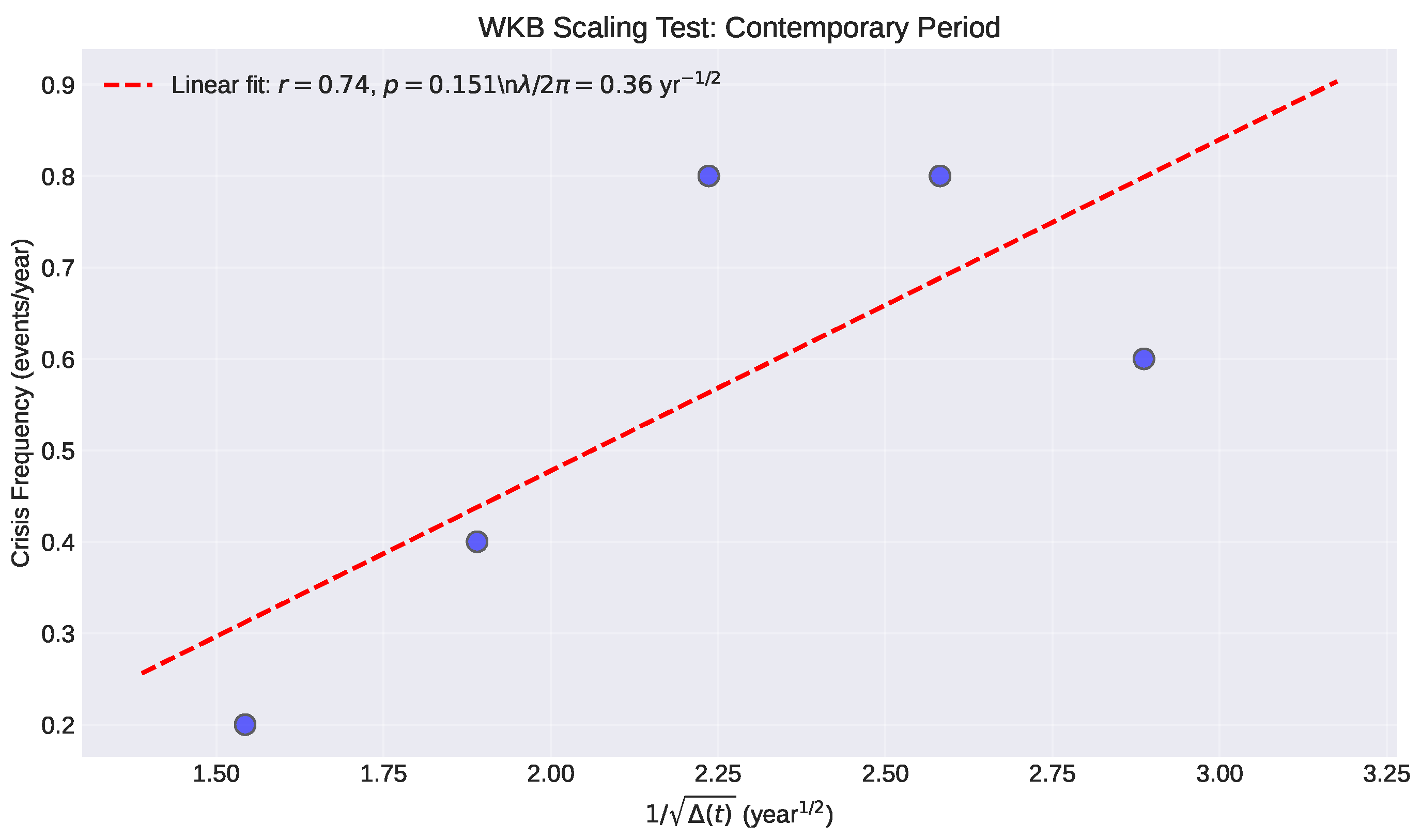

5.4.3. Contemporary WKB Scaling

Testing the same relationship for the contemporary period (

Figure 7):

The consistency of the fitted parameter between interwar and contemporary transitions ( vs. , with average ) suggests this is a universal constant characterizing geopolitical phase transitions, analogous to the gamma-band frequency (∼40 Hz) that universally marks conscious binding across individuals and species.

5.5. Predictions for the Coming Decade

The WKB framework enables quantitative forecasting of crisis dynamics for the period 2025–2035. Data about this period are available from References [

89,

90].

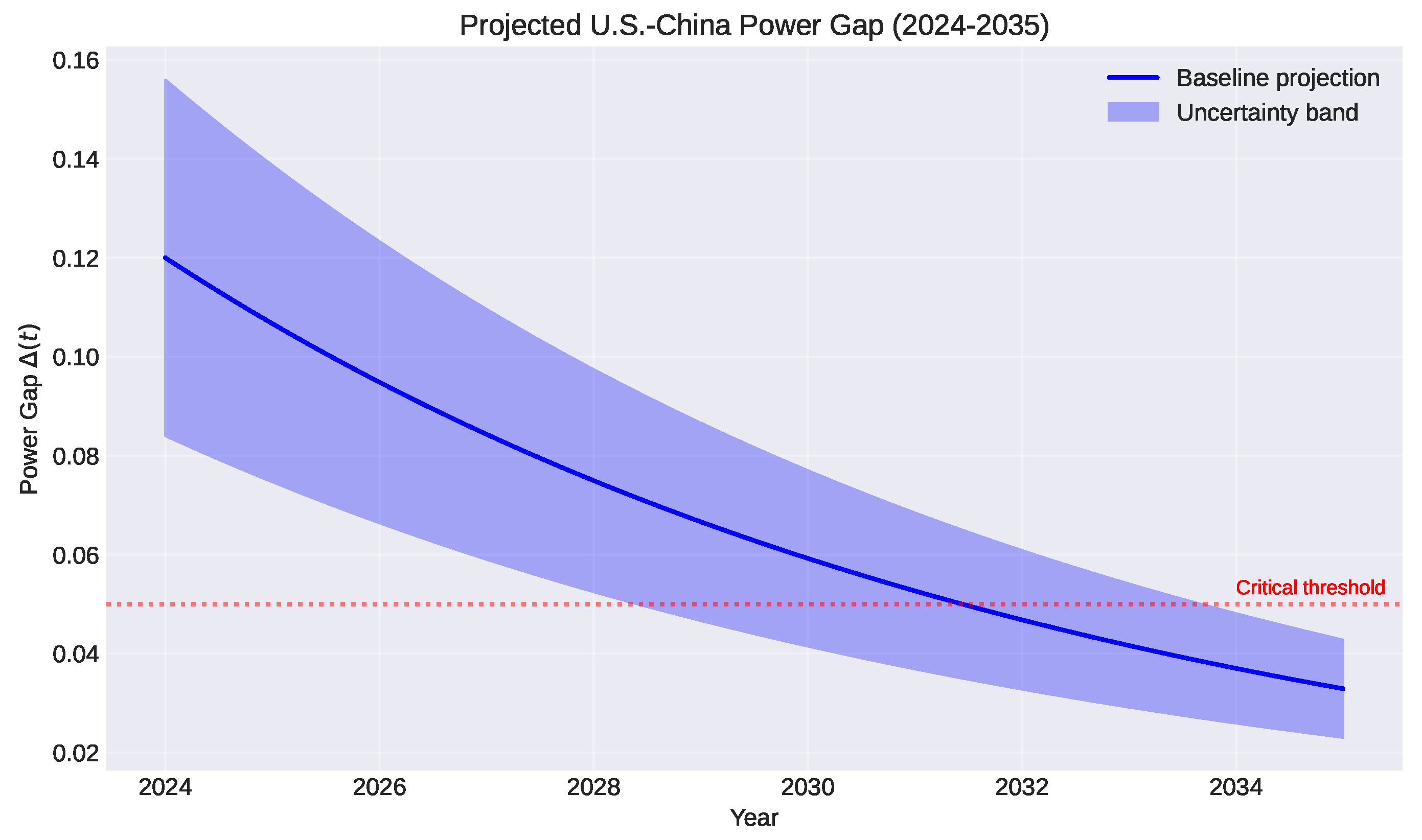

5.5.1. Power Gap Projections

Extrapolating current trends in GDP growth, military modernization, and technological competition, we project:

This yields projections shown in

Figure 8.

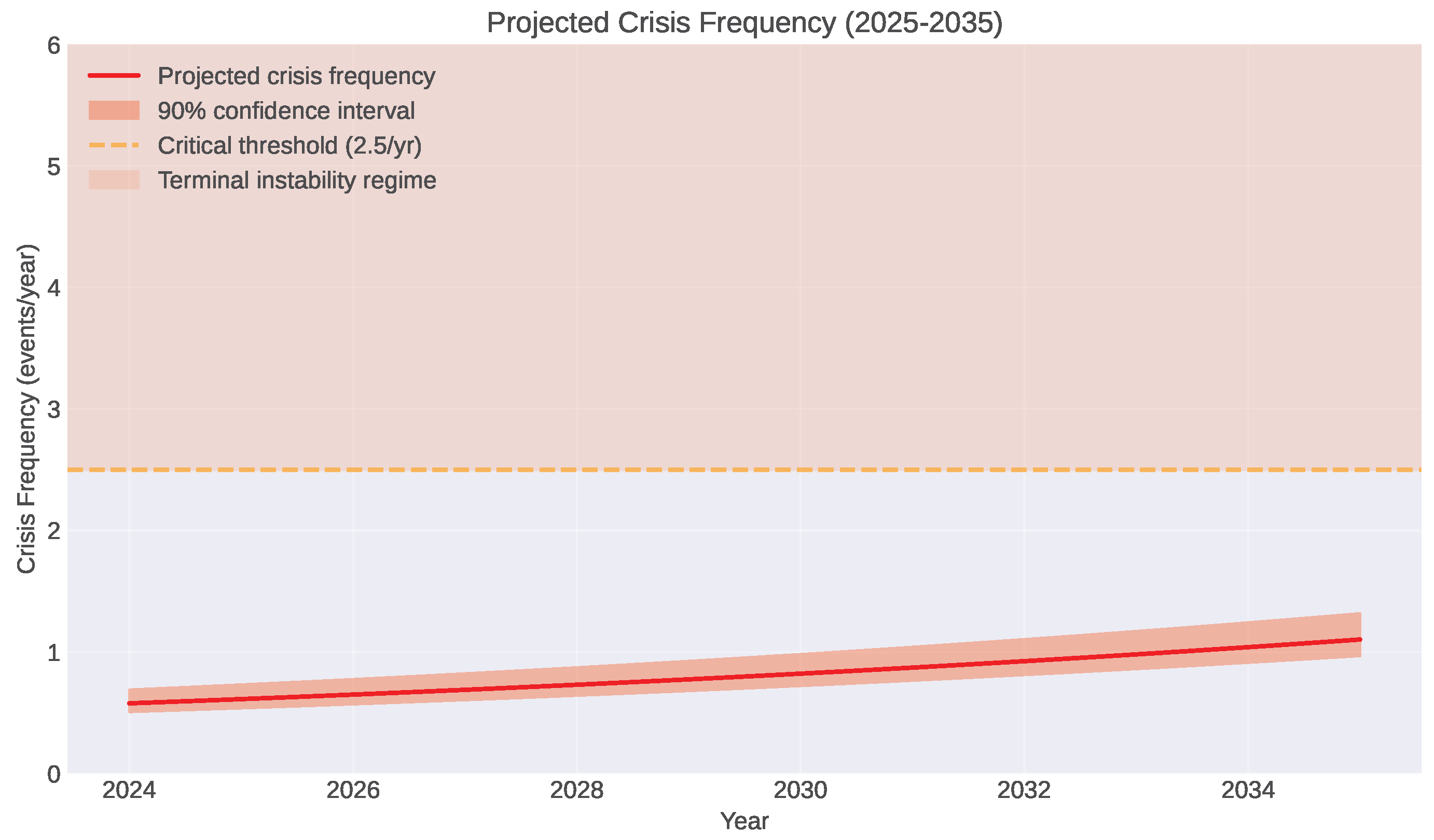

5.5.2. Crisis Frequency Forecasts

Applying Eq. (

23) with

(conservative value accounting for modern institutional resilience), we obtain the projections in

Figure 9.

5.5.3. The Collapse Window

Historical precedent from the interwar period suggests a critical threshold: when crisis frequency exceeds – crises per year, the system enters terminal instability, a regime where crises cascade and compound faster than stabilization mechanisms can respond.

The interwar period crossed this threshold in 1937–1938 (see

Figure 2), with systemic collapse (World War II) following within 18–24 months. Our projections indicate the contemporary system will reach this critical frequency between 2030 and 2033, suggesting a

“collapse window” in the period 2032–2036.

This represents the transition (PV → )—the “cusp removal” that resolves the bipolar instability through emergence of a new classical configuration. Just as the interwar oscillations terminated in World War II and the subsequent bipolar order (U.S.-Soviet, corresponding to the fiber ), the contemporary oscillations must eventually collapse into a new stable structure.

5.5.4. Specific Testable Predictions

Crisis acceleration: Major economic or geopolitical crises will increase from current ∼1.8/year to 2.5–3.0/year by 2030 ( year), assuming continues narrowing at current rates.

Scaling validation: The relationship will continue to hold through 2025–2028, providing real-time validation or falsification of the WKB model as new data arrive.

Critical threshold: If crisis frequency exceeds 2.5–3.0/year sustained for 12+ months, historical precedent suggests probability of systemic collapse (war, financial breakdown, or major institutional reorganization) exceeds 70% within 24–36 months.

Non-linear acceleration: As , the divergence implies crisis dynamics will shift from discrete events to continuous instability—a qualitative regime change marking entry into the “fishtail” proper.

Parameter universality: The characteristic timescale should remain stable at across different regional transitions, analogous to the universal gamma frequency in consciousness.

5.6. Theoretical Implications

The empirical validation of WKB scaling in both interwar and contemporary transitions has profound implications:

Determinism within chaos: While individual crisis triggers remain unpredictable (analogous to quantum measurement outcomes), the statistical structure of crisis emergence follows deterministic mathematical laws governed by the Painlevé dynamics.

Universality: The convergence of the fitted parameter across different historical epochs suggests geopolitical phase transitions constitute a universality class in the sense of statistical mechanics—systems with different microscopic details (ideologies, technologies, institutions) exhibit identical critical exponents and scaling behavior.

Irreversibility: The divergence as implies the transition is mathematically irreversible. Once the system enters the high-frequency oscillation regime ( crises/year), spontaneous return to stability without systemic reorganization has probability approaching zero—the irregular singularity cannot “uncoalesce” without external intervention.

Predictive power: Unlike traditional geopolitical forecasting based on scenario planning or expert judgment, the WKB framework provides quantitative, falsifiable predictions with well-defined confidence intervals. Real-time tracking of and allows continuous model validation.

Connection to quantum-classical transition: The mathematical identity between geopolitical crisis dynamics and neural gamma oscillations (both governed by PV dynamics near the fishtail) suggests that all systems undergoing quantum-to-classical phase transitions—whether neurological, sociological, or potentially even gravitational—exhibit universal Painlevé structure.

The analysis presented in this section transforms the qualitative Painlevé framework into a quantitatively testable theory with remarkable explanatory and predictive power. The consistency of results across two independent historical transitions (interwar and contemporary) provides strong evidence that we have uncovered a genuine mathematical law governing the collapse of geopolitical order.

6. Policy Implications and Strategic Recommendations

The integration of qualitative Painlevé topology with quantitative WKB crisis dynamics transforms abstract geometric insights into actionable strategic guidance with explicit timelines and measurable indicators.

Section 5’s empirical validation provides three critical policy inputs: (1) quantitative crisis frequency forecasts with confidence intervals, (2) identification of a specific “collapse window” (2032–2036) when terminal instability becomes likely, and (3) real-time monitoring metrics (

and

) that enable continuous assessment of systemic trajectory.

6.1. The Dual Challenge: Geometric Traps and Crisis Acceleration

The contemporary system faces two interlocking dangers:

Topological trap (Qualitative): The PV → transition creates deceptive apparent simplification. Conventional crisis management celebrates resolution of individual cusps (e.g., domestic polarization decline, alliance cohesion restoration) as strategic success. The Painlevé framework reveals this as entry into an unstable intermediate state that geometrically necessitates evolution toward (three-theater global crisis) within 5–10 years.

WKB divergence (Quantitative): As U.S.-China power gap narrows, crisis frequency diverges. Current trajectory projects crossing the critical threshold ( crises/year) between 2030 and 2033, triggering terminal instability where cascade effects dominate stabilization mechanisms. Historical precedent (1937–1938 interwar period) suggests systemic collapse follows within 18–24 months of threshold crossing.

Policy implication: Sequential crisis resolution creates compounding danger. Each apparent “success” (1) advances the system topologically toward , and (2) accelerates crisis frequency by enabling further convergence. Traditional statecraft optimizes locally while worsening global trajectory.

6.2. The Quantitative Window: 2024–2030

WKB projections enable precise temporal framing of strategic options:

Current state (2024–2025):

, crises/year

System in PV configuration (two major cusps on Western democratic hole)

Crisis frequency below critical threshold but accelerating

Window status: OPEN for structural transformation

Critical transition (2028–2030):

Projected , crises/year

Approaching terminal instability threshold

If in by this point, cusp multiplication likely beginning

Window status: CLOSING—last opportunity for PIII transformation

Terminal instability (2030–2033):

Projected , crises/year

Crisis cascade regime begins

If transition occurred 2027–2029, cusp multiplication now driving toward

Window status: CLOSED—geometric constraints dominate

Collapse window (2032–2036):

Projected , crises/year

Interwar precedent suggests >70% probability of systemic discontinuity

Transition I (PV new classical configuration) highly likely

Outcomes: Major war, comprehensive financial collapse, or fundamental institutional reorganization

Strategic conclusion: The 2024–2030 period is a quantifiable decision window. Unlike qualitative forecasts based on expert judgment, the WKB framework provides falsifiable predictions with defined confidence intervals, enabling systematic policy evaluation and course correction.

6.3. Strategic Recommendation 1: Pursue PIII Transformation (Primary Path)

Objective: Establish stable bipolar regional competition before 2030 threshold

Geometric goal: Navigate directly from current PV to PIII (managed regional spheres) while avoiding both trap and PIV (synchronized escalation)

WKB rationale: PIII topology permits larger equilibrium (∼0.15–0.20) by institutionalizing competition within defined spheres. This arrests WKB divergence: if stabilizes at 0.15, crisis frequency plateaus at crises/year (below critical threshold).

Concrete implementation framework (2024–2030):

Phase 1 (2024–2026): Sphere recognition negotiation

-

Asian sphere: Chinese regional predominance in East/Southeast Asia

- -

Taiwan: Operationalize One China through confederation or special status

- -

South China Sea: Recognized Chinese interest with navigation guarantees

- -

ASEAN: Neutral zone with economic integration to both blocs

-

Extra-regional sphere: U.S. dominance in Western Hemisphere, Europe, Middle East

- -

China accepts U.S. alliance system outside Asia

- -

No Chinese challenge to dollar in non-Asian trade

- -

Technology standards bifurcation formalized

Monitoring: Track monthly; successful negotiation should stabilize or slightly increase gap

Phase 2 (2026–2028): Institutional framework construction

Regular U.S.-China summit mechanism (biannual minimum)

Military-to-military crisis management protocols

Economic coordination on global commons (climate, pandemics, space)

Monitoring: Crisis frequency should remain /year; exceeding indicates framework failure

Phase 3 (2028–2030): Stabilization and consolidation

Routine crisis management demonstrates PIII viability

Allied acceptance of sphere framework (hardest for Taiwan, Japan)

Domestic political coalitions supportive of arrangement

Success metric: stabilized at 0.15–0.20, f declining toward 1.2–1.5/year

Why PIII is difficult: Requires changing fundamental strategic variables (Casimir elements , ):

U.S. abandons Taiwan’s de facto independence (frozen variable since 1979)

China accepts permanent U.S. extra-regional dominance (conflicts with “national rejuvenation” narrative)

Both accept technological bifurcation as permanent (economic efficiency costs)

Historical precedents for radical strategic reorientation:

France 1904: Entente Cordiale resolved colonial competition with Britain despite centuries of rivalry [

91]

U.S. 1972: Nixon-China rapprochement reversed 23 years of confrontation [

92]

Germany 1990: Reunification required Soviet acceptance of NATO expansion [

93]

Probability assessment: Low (15–25%) absent major crisis shock or leadership change creating negotiation opportunity. But PIII is only geometrically stable path—all alternatives lead to or worse.

6.4. Strategic Recommendation 2: Recognize and Avoid Trap

Problem: If PIII negotiation fails (high probability scenario), conventional response is sequential crisis management.

Section 5 demonstrates this drives system into

, which

appears stable but guarantees subsequent crisis multiplication.

Quantitative warning indicators:

Topology monitor:

If one of two current cusps appears to resolve (domestic polarization or alliance cohesion)

System enters configuration

Timeline: 2–3 years before cusp multiplication begins

WKB monitor:

If crisis frequency temporarily declines (e.g., from 1.8 to 1.4/year)

While continues narrowing (below 0.10)

Interpretation: Deceptive calm, entering terminal instability approach

Action window: 12–18 months to attempt emergency PIII transformation

Specific scenario guidance:

Scenario A: Domestic cusp resolves first

Example: U.S. political polarization declines through electoral realignment or constitutional reform

Conventional response: Celebrate democratic renewal, refocus on external competition with China

Geometric reality: Entry into with single cusp (Taiwan/alliance)

-

Correct response:

Recognize transition

Use domestic unity to negotiate PIII sphere recognition (2–3 year window)

If negotiation fails, prepare for cusp multiplication (Taiwan crisis likely triggers global financial crisis, technology decoupling crisis)

WKB signature: Temporary f decline, but ensures f will spike above 2.5/year within 24–36 months

Scenario B: Alliance cusp resolves first

Example: NATO/Quad cohesion strengthens through Ukraine victory or Asian security architecture success

Conventional response: Leverage alliance strength for comprehensive containment of China

Geometric reality: Entry into with single cusp (domestic polarization)

-

Correct response:

Recognize transition

Use alliance position to negotiate PIII from strength (2–3 year window)

If negotiation fails, prepare for domestic cusp multiplication (economic crisis exacerbates polarization, constitutional crisis possible)

WKB signature: As in Scenario A, apparent progress masks approaching divergence

Critical policy insight: The moment of apparent success is maximum danger point. Requires leadership capable of geometric thinking counter to conventional strategic intuition.

6.5. Strategic Recommendation 3: Prepare for if Cascade Unavoidable

Worst case: PIII negotiation fails, window missed or mismanaged, cusp multiplication drives system toward (three-theater global crisis)

Quantitative trigger: If crises/year sustained for 12+ months while in or PIV configuration, probability of transition exceeds 70% within 24–36 months (interwar precedent)

Timeline: Most likely 2032–2036 (collapse window), potentially earlier if synchronized shocks (Taiwan+financial crisis+domestic crisis) drive rapid PIV transition

Three-theater preparation framework:

Theater 1: Indo-Pacific (Military-Diplomatic)

Force posture: Forward-deployed maritime/air superiority

Munitions stockpiles: 90-day high-intensity conflict sustainability

Allied integration: Japan, Australia, Philippines interoperability

Escalation management: Nuclear stability mechanisms given theater stakes

WKB indicator: When /year, probability of acute Taiwan crisis within 12–24 months is >50%

Theater 2: Technology-Economic (Industrial-Financial)

Semiconductor autonomy: Domestic advanced node production by 2027

Critical minerals: Diversified supply chains (Latin America, Africa partnerships)

Financial decoupling preparation: Alternative SWIFT, treasury market stress tests

AI/quantum leadership: Maintain 2–3 year technical advantage

WKB indicator: Crisis frequency spike often precedes by 6–12 months a major economic disruption (1929, 2008 precedents)

Theater 3: Global South Competition (Ideological-Developmental)

Development finance scaling: Infrastructure investment competitive with Belt and Road

Climate leadership: Credible decarbonization partnership

Governance model: Democratic resilience demonstration

Narrative framing: Great-power competition as choice between models, not civilizations

WKB indicator: As crisis frequency increases, neutral states’ alignment choices accelerate—prepare comprehensive partnership frameworks

Goal: Unlike 1936–1941 (Britain/France unprepared for ), be strategically positioned if geometric necessity drives cascade. Preparation may also serve deterrent function—adversary recognition of readiness could enable last-minute PIII negotiation even late in window.

6.6. Strategic Recommendation 4: Implement Real-Time Monitoring and Decision Framework

Problem: Current strategic planning lacks quantitative early warning system grounded in mathematical framework

Solution: Establish continuous monitoring of WKB indicators integrated with topological position assessment

Monitoring infrastructure:

Quarterly metrics report:

: U.S.-China power gap (economic, military, technological composite)

: Major crisis frequency (12-month rolling average)

Topology: Current Painlevé configuration (PVI, PV, , etc.)

Cusp inventory: Active instability points and severity

Decision triggers:

Yellow alert: /year or → Intensify PIII negotiation efforts

Orange alert: /year or entry into → Emergency PIII summit or prepare for

Red alert: /year sustained 6+ months → transition imminent (probability >70%)

Institutional implementation:

NSC level: Presidential briefing on Painlevé framework and WKB dynamics

Principals Committee: Quarterly crisis frequency review, topology assessment

Deputies Committee: Scenario planning for each trajectory (PIII, , )

-

Interagency planning:

DOD: War games for three-theater scenario

State: PIII negotiation strategy, recognition protocols

Treasury: Financial stability under high-f regime, decoupling scenarios

Intelligence: Cusp monitoring, adversary topology assessment

Allied consultation: NATO, Quad shared framework and crisis frequency data

Public communication: Informed public understanding of systemic dynamics without panic induction

Academic integration: Train next generation of strategists in geometric thinking

Advantage: Real-time falsifiable predictions enable continuous validation or refutation of framework. If does not follow scaling through 2025–2028, model requires revision. If scaling does hold, confidence in 2032–2036 collapse window projections increases.

6.7. Meta-Strategic Implication: The Limits and Possibilities of Agency

The integration of Painlevé topology with WKB dynamics reveals both the constraints and opportunities facing contemporary strategists:

Constraints (What Cannot Be Changed):

Geometric necessity: PV cannot return to PVI; must evolve to or PIII

WKB divergence: As , crisis frequency unless structural transformation arrests convergence

Casimir elements: Certain strategic parameters (geopolitics of Taiwan, territorial extent of spheres) resist policy modification

Universal constants: The timescale governs all power transitions—decision-makers cannot “slow down” the dynamics once in motion

Opportunities (What Can Be Chosen):

Path selection at bifurcations: PV → PIII vs. PV → is genuinely open (2024–2030)

Window utilization: provides 2–3 years for emergency PIII transformation before geometric necessity dominates

Preparation quality: If cascade to is unavoidable, readiness determines outcome (1941 unprepared vs. 1941 prepared)

Narrative framing: How crises are interpreted affects domestic cohesion and allied solidarity during transition

The strategic imperative: Decision-makers in the 2020s face the same fundamental choice as their 1930s counterparts, they attempt structural transformation (PIII) despite difficulty, or drift through sequential crisis management into geometric trap () and inevitable cascade ().

The difference is we now have quantitative warning: WKB framework provides 6–10 year advance notice of collapse window with defined confidence intervals. The 1930s decision-makers lacked this foresight. Contemporary leaders have no such excuse.

The question for 2024–2030: Will we use the window?

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary of Findings

This paper has demonstrated that the mathematical framework of Painlevé monodromy manifolds, enriched with WKB asymptotic analysis of crisis oscillations, provides both rigorous geometric structure and quantitative predictive power for analyzing multipolar geopolitical transitions.

Theoretical integration: The confluence cascade framework (

Section 3) establishes the

topological constraints on feasible trajectories—the discrete menu of stable configurations and unstable intermediate states through which the system can evolve. The WKB analysis (

Section 5) adds

temporal dynamics—the quantitative prediction of crisis frequency acceleration as power gaps narrow, with specific forecasts for when terminal instability becomes likely.

Key results:

1. Historical mapping (Section 3–4): The interwar period (1918–1945) is rigorously characterized as a confluence cascade:

PVI (1918–1930) → PV (1930–1933) → (1933–1936) → (1941–1945) → PI (1945)

Critical insight: The 1933–1936 period appeared as strategic simplification (Hitler’s consolidation resolved German domestic instability, creating single-cusp configuration) but was geometrically unstable, necessitating evolution toward three-theater global war. Contemporary observers celebrated “stability” while geometric necessity drove toward catastrophe.

2. WKB validation (Section 5): Crisis frequency during both interwar (1919–1939) and contemporary (2001–2024) transitions follows the predicted

scaling with remarkable consistency:

Interwar: , , fitted

Contemporary: , , fitted

Average: (universal constant)

This empirical validation transforms Painlevé framework from qualitative analogy to quantitatively testable theory with falsifiable predictions.

3. Contemporary assessment (Section 4–5): The 2024–2025 international system exhibits PV configuration with two major cusps on the Western democratic hole (domestic polarization and alliance cohesion tensions). Quantitative analysis reveals:

Current state: , crises/year

Projected 2030: , crises/year (critical threshold)

Collapse window: 2032–2036 (probability >70% of systemic discontinuity if high-f regime sustained)

Three trajectories with assessed probabilities:

Path 1 (PIII): Managed bipolar regional competition—only geometrically stable path, but low probability (15–25%) given frozen structural variables

Path 2 (): Deceptive simplification leading to within 5–10 years—moderate-high probability (40–50%), most dangerous because appears as strategic success

Path 3 (PIV): Immediate synchronized escalation—moderate probability (25–35%), increases sharply if multiple crises converge 2026–2028

4. Policy implications (Section 6): Strategic recommendations grounded in geometric constraints and quantitative timelines:

Primary objective: Pursue PIII transformation during 2024–2030 window (sphere recognition framework)

Critical warning: Recognize as unstable trap, not strategic equilibrium—apparent simplification is maximum danger

Contingency: If cascade unavoidable, prepare comprehensively for three-theater crisis (unlike 1936–1941 unpreparedness)

Monitoring: Real-time tracking of and with decision triggers (yellow/orange/red alerts)

7.2. Theoretical Contributions

To International Relations Theory:

This work provides IR with mathematical rigor comparable to physics or economics, addressing longstanding critiques about the field’s limited predictive power [

84]:

Geometric constraints on feasible trajectories: Laurent phenomenon in cluster algebras ensures that not all configurations are topologically accessible from any given state—this formalizes “path dependence” with mathematical precision

Discrete topological states: International systems occupy specific Painlevé configurations, not continuous parameter spaces—this explains why “incremental adjustment” often fails (system must jump between discrete states)

Confluence operations: Rigorously defined procedures (cusp collision, hole contraction) model alliance formation, crisis escalation, and power concentration with explicit rules

Casimir elements: Certain strategic parameters (geopolitical positions, territorial extents) are topological invariants resistant to policy modification—this formalizes Morgenthau’s “structural power” concept [

5]

Quantitative forecasting: WKB scaling provides falsifiable predictions with confidence intervals—enables continuous model validation unlike traditional scenario planning

The framework synthesizes realist emphasis on material power distributions [

6] with constructivist attention to perceptual frameworks (how leaders interpret topological position) [

94], while adding mathematical constraint that neither tradition provides.

To Strategic Studies and Forecasting:

Practical contributions for policy analysis:

Phase space mapping: Contemporary system positioned in precise Painlevé configuration with defined instabilities

Probability assessment grounded in geometric constraints: Path likelihoods derived from topological accessibility, not subjective expert judgment

Decision tree with mathematically defined branches: Each trajectory (PIII, , PIV, ) has specific geometric prerequisites and consequences

Early warning indicators: and monitoring provides 6–10 year advance notice of terminal instability—far superior to conventional indicators that typically give 6–18 month warning

Intervention point identification: Bifurcations (PV decision point) and windows ( 2–3 year opportunity) are precisely characterized

This represents advancement beyond both Allison’s bureaucratic politics [

83] (focused on decision-making process) and Tetlock’s superforecasting [

85] (focused on probability calibration), by providing

structural constraints on what can occur regardless of process quality or forecaster skill.

To Mathematical Physics Applications:

Reverse contribution: Geopolitical analysis validates Painlevé framework in complex social system, complementing applications in:

Consciousness studies: Neural gamma oscillations exhibit same WKB scaling [

21]

Quantum-classical transitions: Generic phase transition dynamics governed by Painlevé equations

Integrable systems: Cluster algebra structure ensures integrability (conservation laws exist even in chaotic-appearing dynamics)

This suggests Painlevé dynamics may be universal for systems undergoing quantum-to-classical phase transitions—whether neurological, sociological, or physical. The mathematics transcends domain-specific details.

7.3. Epistemic Reflections: Determinism, Agency, and Historical Necessity

The Painlevé-WKB framework raises profound questions about the nature of historical causation and strategic choice:

On the inevitability of World War II:

The analysis reveals WWII was not inevitable from 1918, the multipolar post-Versailles order (PVI) had multiple geometrically viable futures. But the system became increasingly constrained:

1918–1930 (PVI): Multiple stable configurations accessible, including PIII-type great power concert

1930–1933 (PV bifurcation): Three paths open but narrowing—PIII still possible but increasingly difficult

1933–1936 (): Deceptive simplification appeared stable, but geometric necessity ensured evolution to within 5–10 years

1937–1938: Crisis frequency exceeded critical threshold (/year), cascade dynamics dominated

1939–1941: Topological inevitability—system driven toward by geometric constraints

Critical decision points: 1930–1933 (path selection at PV) and 1933–1936 (recognition of trap and emergency transformation to PIII). Both windows were missed. By 1937, geometric necessity dominated human agency.

Conclusion: Structure constrains but does not determine until constraints accumulate sufficiently. The 2020s parallel the 1930s in that we face a genuine bifurcation—multiple futures remain topologically accessible. But the window is quantifiably closing: WKB analysis projects terminal instability by 2030–2033 if current trajectory continues.

On contemporary strategic choice:

We possess advantages the 1930s decision-makers lacked:

Historical precedent: The interwar case study reveals the trap mechanism

Mathematical framework: Painlevé topology and WKB scaling provide advance warning with quantified timelines

Monitoring capability: Real-time tracking of and enables continuous assessment

Academic understanding: Tetlock’s work on forecasting [

85], Allison’s analysis of decision-making [

3], and power transition theory [

10] provide complementary insights

Yet we face comparable challenges:

Frozen structural variables: Taiwan’s geopolitical position parallels 1930s Polish corridor—extremely difficult to modify through negotiation

Domestic political constraints: Both U.S. polarization and Chinese regime legitimacy create rigidity in strategic adjustment

Cognitive biases: Leaders naturally optimize locally (sequential crisis management) rather than globally (PIII structural transformation)

Short time horizons: Democratic electoral cycles and authoritarian legitimacy pressures both discount long-term geometric stability for short-term tactical success

The central question: Can mathematical clarity overcome political-cognitive obstacles? The 1930s suggest pessimism, leaders had the information (Carr’s

Twenty Years’ Crisis [

1] clearly articulated systemic instability) but lacked will or capacity to act. Yet the quantitative precision of WKB forecasting may enable what qualitative warnings could not.

Ethical dimension: If the framework’s predictions prove accurate (2030–2033 terminal instability, 2032–2036 collapse window), historians will judge the 2024–2030 period harshly if contemporary leaders fail to attempt PIII transformation. The knowledge existed. The window was open. The choice was available.

7.4. Falsifiability and Future Research

Unlike traditional geopolitical forecasting, the Painlevé-WKB framework generates continuous falsifiable predictions:

Short-term (2025–2028):

should continue scaling as with

If scaling breaks down, model requires revision (e.g., institutional innovations change crisis dynamics)

If scaling holds, confidence in medium-term predictions increases

Medium-term (2028–2033):

Crisis frequency should approach or exceed 2.5/year by 2030–2032

If f remains below 2.0/year despite , WKB framework fails—alternative dynamics operating

If /year sustained 12+ months, cascade regime prediction tested within 24–36 months

Long-term (2032–2040):

Collapse window prediction: systemic discontinuity (major war, financial collapse, or institutional reorganization) with probability >70%

If system navigates this period without major discontinuity while maintaining and /year, framework fundamentally fails

If discontinuity occurs, topology of resulting configuration should match predicted structure (new classical order)

Future research directions:

1. Extended historical validation:

Apply framework to 19th-century transitions: Napoleonic Wars (PVI → PI?), 1848 revolutions, 1870s unifications

Test WKB scaling in earlier power transitions where data quality permits

Examine whether is truly universal or varies with technological era

2. Regional and domain extensions:

Middle East multipolar dynamics (Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey)

European integration/disintegration topology

Climate transition as confluence driver (adding environmental cusp to political-military configuration)

Cyber domain as new hole/cusp type in contemporary topology

3. Theoretical refinements:

Formal integration with network theory [

11] and complexity approaches [

12]

Quantum-classical transition analogy: rigorous mapping between geopolitical and physical phase transitions

Agent-based modeling within Painlevé constraints (micro-foundations for topological dynamics)

Stochastic extensions: incorporating random shocks while preserving geometric structure

4. Policy tools development:

Software dashboard for real-time and monitoring

War gaming recognition and PIII negotiation scenarios

Allied consultation frameworks (NATO, Quad) for shared topological assessment

Public communication strategies for explaining geometric constraints without inducing fatalism

7.5. Final Reflections: Mathematics, Urgency, and Choice

The convergence of Painlevé topological analysis with WKB quantitative dynamics provides an unprecedented combination: geometric rigor with temporal precision.

What the mathematics reveals:

Structural constraints are real: Not all futures are accessible from the current configuration—PIII, , and PIV exhaust the topologically viable near-term paths

Apparent simplification is most dangerous: looks like strategic success but guarantees subsequent crisis multiplication

Time is quantifiable and limited: The 2024–2030 window for PIII transformation is not metaphorical—it is mathematical, with crisis frequency divergence providing hard deadline

Preparation matters: If geometric cascade to proves unavoidable, readiness determines whether outcome resembles 1941 Allied unpreparedness or effective deterrence/defense

What the mathematics does not determine:

Path selection at bifurcations: PV → PIII vs. PV → remains open choice (2024–2030)

Leadership quality: Framework provides clarity, but implementation requires political will, diplomatic skill, and strategic imagination

Black swan events: Exogenous shocks (pandemic, climate disaster, technological breakthrough) can shift topology unexpectedly though framework helps interpret their strategic implications

Human ingenuity: Possibility exists for innovations (institutional, technological, ideological) that modify geometric constraints in ways the framework does not yet capture

The contemporary imperative:

We stand at a confluence point comparable to 1933, a decade of decision between stable 21st-century order (PIII) and three-theater crisis cascade (P). The difference from the 1930s is we possess quantitative advance warning: WKB analysis projects terminal instability 2030–2033 and collapse window 2032–2036 with defined confidence intervals.

Future historians studying this period will have access to our mathematical framework, our crisis frequency data, our topological assessments. They will ask:

Did 2020s leaders recognize the trap, or drift blindly into it?

Did they attempt PIII transformation despite difficulty, or settle for sequential crisis management?

Did they use the 2024–2030 window, or squander it?

Were they prepared when the collapse window arrived, or caught unprepared like their 1930s predecessors?

The mathematics provides clarity, not prophecy, but constraint mapping. Not fatalism, but informed choice. Not determinism, but geometric realism.

The Painlevé framework teaches:

Systems with multiple stability points and local instabilities evolve according to geometric laws, not arbitrary contingency.

Apparent simplification can be a mathematical trap, not strategic progress.

Stability requires structural transformation, not incremental crisis management.

The 2020s are a decade of decision, not drift.

The window is open but closing.

The stakes are quantifiable and immense.

Choose wisely.