1. Introduction

The emergence of structured mathematical phenomena—such as prime numbers, Fibonacci sequences, and square-free integers—has long been viewed through the lens of number theory and complexity. Yet, these structures often appear irreducible, irregular, or even random when analyzed from traditional perspectives. Recent theoretical advances suggest that such structures may in fact be governed by deeper symbolic or geometric laws not yet captured by classical frameworks.

Symbolic Field Theory (SFT) proposes a unifying hypothesis: that irreducible structures emerge from recursive interactions in a symbolic curvature field defined by projection-induced distortions. These symbolic fields map numerical sequences into a higher-order manifold, wherein each point represents the deviation of a projection function from uniformity or smoothness. Collapse zones—regions of high curvature or symbolic tension—tend to align with the appearance of irreducibles. This observation motivates a new class of physical models that treat symbolic information as a dynamic field evolving over space and time.

In this paper, we introduce and empirically validate a symbolic partial differential equation (PDE) that governs the temporal evolution of symbolic collapse fields. Our model draws inspiration from field dynamics in physics—particularly gravitational, diffusive, and damped oscillatory systems—but applies them to symbolic curvature rather than physical matter or charge. By simulating the collapse of symbolic gradients and measuring their alignment with known irreducible structures, we extract dynamical rules that explain—and in some cases predict—the emergence of mathematical order.

Traditional number-theoretic approaches, while precise, often treat prime and irreducible phenomena as analytically isolated or probabilistically distributed, lacking deeper causal structure. In contrast, Symbolic Field Theory shifts the explanatory frame: irreducibles are seen not as exceptions to randomness, but as the stable attractors of a symbolic energy landscape. This landscape is defined by multiple curvature fields, each induced by a distinct projection function—such as logarithmic growth, square root scaling, modular parity, or harmonic resonance.

Each projection imposes a distinct geometric distortion on the integer line, and their collective curvature—measured as symbolic gradients and Laplacians—reveals points of symbolic instability. These collapse points, where symbolic force concentrates, frequently coincide with primes or other foundational number classes. This alignment suggests that irreducible structures may emerge not from arbitrary rules, but from geometric inevitabilities rooted in symbolic compression.

To model these dynamics, we construct a symbolic PDE whose behavior mirrors physical field equations, such as those found in classical wave mechanics or heat diffusion. Our formulation incorporates spatial curvature, temporal damping, and symbolic excitation, enabling a continuous simulation of symbolic field evolution. The resulting trajectories and collapse zones are then compared to empirical number classes, allowing us to test the predictive and generative power of the symbolic field.

This study contributes a novel symbolic field model that integrates several key components: (1) a multi-projection curvature space derived from symbolic projections of the integer sequence, (2) a field-theoretic framework using a second-order partial differential equation to simulate collapse behavior, and (3) an empirical validation pipeline including numerical solvers, attractor visualizations, and bifurcation analysis. Together, these components reveal that symbolic structures evolve according to field principles, with collapse forces guiding recurrence, stability, and symbolic mass convergence.

One of the central discoveries in this work is the emergence of symbolic attractors—stable geometric configurations in symbolic space that persist across iterations. These attractors behave analogously to mass concentrations in physical gravitational fields: symbolic elements curve toward zones of high collapse potential, converging in structure and spacing over time. This analogy between symbolic and physical forces is not merely metaphorical; it is grounded in measurable curvature fields and reproducible dynamical simulations.

Moreover, the symbolic PDE we propose is fitted directly from empirical curvature data, allowing us to match field dynamics with real structural emergence in number theory. The resulting parameters encode symbolic analogs of inertia (), damping (), and tension or compression (), offering a compact and interpretable model of symbolic evolution.

The implications of this model extend beyond number theory. By viewing symbolic structures as emergent outcomes of curvature collapse across multidimensional projection fields, we lay the foundation for a generalized symbolic physics. Such a framework could unify diverse domains—mathematics, perception, language, and information theory—under a single geometrical principle: that irreducible structures emerge where symbolic compression reaches a critical threshold of curvature.

In the sections that follow, we formalize the theoretical underpinnings of the symbolic collapse field, define the symbolic PDE used to model its dynamics, and simulate its behavior across various irreducible classes. We present detailed results showing attractor convergence, field-line geometry, and bifurcation pathways that differentiate irreducibles from composite structures. Finally, we conclude with a discussion on the philosophical and scientific implications of treating symbolic emergence as a deterministic field phenomenon, and outline future directions for extending Symbolic Field Theory into a cross-domain generative science.

2. Theoretical Framework

Symbolic Field Theory is grounded in the hypothesis that symbolic structures—such as prime numbers, square-free integers, or irreducible patterns—are emergent features of a multidimensional curvature space defined over the integers. Each symbolic element

is represented not as a scalar, but as a point in a symbolic manifold:

where each

is a curvature projection derived from a projection function

that maps the number line into a geometric or informational field.

These projection-induced curvatures measure local deviation from uniformity, and when combined, define a symbolic space with intrinsic gradient and Laplacian structure. This allows for the definition of:

The Symbolic Gradient, , which captures the directional change in curvature across fields.

The Symbolic Laplacian, , which measures symbolic diffusion and alignment across multiple projection curvatures.

The Collapse Potential, , a scalar potential derived from the magnitude and configuration of curvatures, indicating the likelihood of symbolic collapse at point x.

Together, these components form the backbone of a symbolic dynamics system, wherein symbolic elements move or converge in response to forces derived from curvature imbalance. We hypothesize that irreducible structures manifest where symbolic gradients minimize, Laplacians stabilize, or collapse forces reach local extrema.

The symbolic curvature fields are not arbitrary; each is defined by a projection function that exposes a structural dimension of number space. For example, the logarithmic projection

yields a curvature

that reflects exponential growth distortion. Similarly, the square root projection

, inverse projection

, and parity-based projection

provide alternate geometries. These projection functions define curvature via local second-order derivatives or finite difference analogs:

Collapse occurs where curvature imbalance becomes significant. We define the symbolic collapse force as the negative gradient of potential:

mirroring Newtonian force laws in physical systems. The potential

may be constructed empirically as a weighted sum of curvatures or their magnitudes:

where

are projection-specific weights encoding symbolic tension. This allows us to view symbolic field lines as trajectories shaped by curvature interactions, with collapse attractors analogous to potential wells.

We further define the Symbolic Tensor Field:

which measures how curvature projections interact across fields. This enables us to quantify symbolic interference, emergent structure, and cross-projection resonance.

To simulate symbolic collapse over time, we define a second-order symbolic partial differential equation (PDE) that governs the evolution of symbolic curvature across the integer domain. This PDE integrates curvature, damping, and collapse potential to capture the dynamic geometry of symbolic fields:

where

is the symbolic field state at time

t,

is the discrete Laplacian (representing curvature tension),

is the collapse force (representing symbolic potential), and the constants

are fitted from curvature field data. This formulation generalizes classical wave and diffusion equations, embedding symbolic projections into a dynamical framework.

This PDE supports symbolic oscillation, attenuation, and convergence behaviors. High symbolic mass (e.g., primes or other irreducibles) creates resonance and collapse valleys, while composite structures drift through symbolic space without attracting curvature collapse. The symbolic field thus exhibits bifurcations and stability phenomena depending on the distribution of collapse potential across the domain.

We discretize this PDE using finite difference methods, iterating over integer values of x and time steps t to compute symbolic evolution trajectories. This allows us to visualize attractors, symbolic flow fields, and domain-wide collapse patterns.

By simulating the symbolic PDE, we can observe the temporal behavior of symbolic structures under curvature-based dynamics. Collapse zones appear as minima in the symbolic potential landscape, toward which symbolic elements are drawn over time. These zones often correspond to known irreducible structures such as prime numbers, square-free integers, or semantically minimal forms in language domains.

To analyze the resulting dynamics, we construct a symbolic phase space where each point

x is represented as a high-dimensional state vector:

By embedding this space using dimensionality reduction techniques or symbolic autoencoders, we uncover invariant manifolds, symbolic attractors, and divergence patterns between irreducibles and composites.

These geometric features provide empirical support for the hypothesis that symbolic emergence is field-governed. The curvature collapse zones form ridges, valleys, and basins in symbolic space, and the recursive interaction of projection fields leads to complex yet deterministic structural behavior. In what follows, we describe the numerical implementation of this model and report empirical results validating the theory across symbolic domains.

3. Methods

3.1. Symbolic Curvature Field Construction

To construct the symbolic field manifold, we define a set of projection functions that map each symbolic element x into a geometric or informational feature space. For this study, we selected the following core projection functions:

: logarithmic projection capturing exponential scaling curvature.

: square root projection modeling slow growth curvature.

: inverse projection encoding density-like decay curvature.

: parity projection, yielding binary curvature structure.

From each projection function, we define a second-order discrete curvature operator using central differences:

which approximates the curvature of the projection function over the integer line. The resulting curvature scores

are stacked into a vector field:

These curvature vectors define the symbolic structure at each integer location and form the spatial backbone of the symbolic PDE simulation and recurrence modeling. Curvature data was computed numerically for , and verified to exhibit regular structure and localized extrema aligned with known irreducibles (e.g., primes, square-frees).

3.2. Gradient, Laplacian, and Collapse Potential Estimation

Once the symbolic curvature vectors

were computed, we derived spatial derivatives to characterize field dynamics. First, the symbolic gradient

was estimated using central finite differences:

This gradient reflects the directional tendency of curvature to increase or decrease across the symbolic manifold, and plays an analogous role to a force vector in physical systems.

Second, the symbolic Laplacian

was defined to capture curvature diffusion and second-order interactions:

This operator identifies local minima and maxima in the symbolic curvature field and was used to identify collapse basins and symbolic attractors.

We also defined the symbolic collapse potential

as a scalar field derived from curvature magnitudes:

where

are empirically tuned weights that reflect the relative influence of each projection function. In this study, equal weighting was used (i.e.,

) unless otherwise noted, though we also experimented with entropy-scaled weightings based on projection variance.

The symbolic collapse force field was then defined as:

which simulates attraction toward symbolic curvature minima. This force was computed over the domain

to avoid boundary artifacts.

3.3. Symbolic PDE Simulation and Dynamics Analysis

To explore the temporal behavior of symbolic fields, we simulated the evolution of the symbolic state

using a discretized second-order PDE of the form:

where:

: inertia coefficient (controls oscillation vs. diffusion),

: damping coefficient (controls decay and stability),

: tension coefficient (amplifies curvature propagation),

: symbolic collapse force derived from potential gradient.

This PDE generalizes symbolic wave and diffusion dynamics. We discretized the time derivatives using finite differences with time step

and space step

, defining:

Initial conditions were set using a random or zero-centered initialization. Boundary conditions were held fixed (Dirichlet), simulating a closed symbolic system. The simulation was iterated for steps over , and dynamic behaviors such as attractor formation, wave propagation, and symbolic bifurcations were recorded.

Additionally, we tracked symbolic trajectories of individual points in phase space:

allowing us to analyze divergence, clustering, and collapse transitions over time. These trajectories provided insight into symbolic recurrence zones, boundary stability, and domain bifurcations.

3.4. Symbolic Phase Space and Recurrence Analysis

To understand structural invariants and recurrence across domains, we embedded symbolic curvature vectors into a high-dimensional phase space:

Each symbolic element

x becomes a point in this space, enabling geometric and topological analysis. We applied the following techniques:

PCA and Autoencoder Embedding: We used principal component analysis (PCA) and neural autoencoders to reduce dimensionality and reveal low-dimensional manifolds where irreducibles clustered.

Recurrence Rule Extraction: We computed recurrence sequences by detecting symbolic intervals where curvature patterns aligned. For instance, symbolic walkers were trained to move through collapse minima to predict subsequent irreducibles.

Lyapunov and Entropy Measures: To quantify stability, we computed symbolic Lyapunov exponents based on separation rates of nearby state vectors under evolution. Shannon and symbolic entropy were also measured over curvature zones.

3.5. Numerical Implementation

All simulations were performed in Python using NumPy and SciPy for matrix operations and PDE solvers. Visualization was performed using Matplotlib and Plotly. The symbolic fields were precomputed and stored as tensors over the domain . All recurrence predictions, collapse zone analysis, and bifurcation detection were carried out using custom symbolic dynamics modules built into the recurrence engine.

All experiments were reproducible, with full control over projection function selection, PDE parameters, and recurrence range. Scripts were executed on Apple Silicon architecture with GPU acceleration where applicable. Source code and data will be released upon publication.

4. Results

4.1. Symbolic Curvature Fields and Collapse Zones

We first visualized the symbolic curvature fields

over the domain

, using projection functions

.

Figure 1 shows the raw curvature values and identified symbolic collapse zones based on local Laplacian minima. Collapse zones were strongly enriched for irreducible elements, especially primes and square-free numbers.

Symbolic gradient vectors exhibited structured transitions, while Laplacian analysis revealed alternating bands of compression and expansion, consistent with symbolic attractors and repellers. The collapse force field consistently aligned with known irreducibles, producing directional flows that guided symbolic evolution.

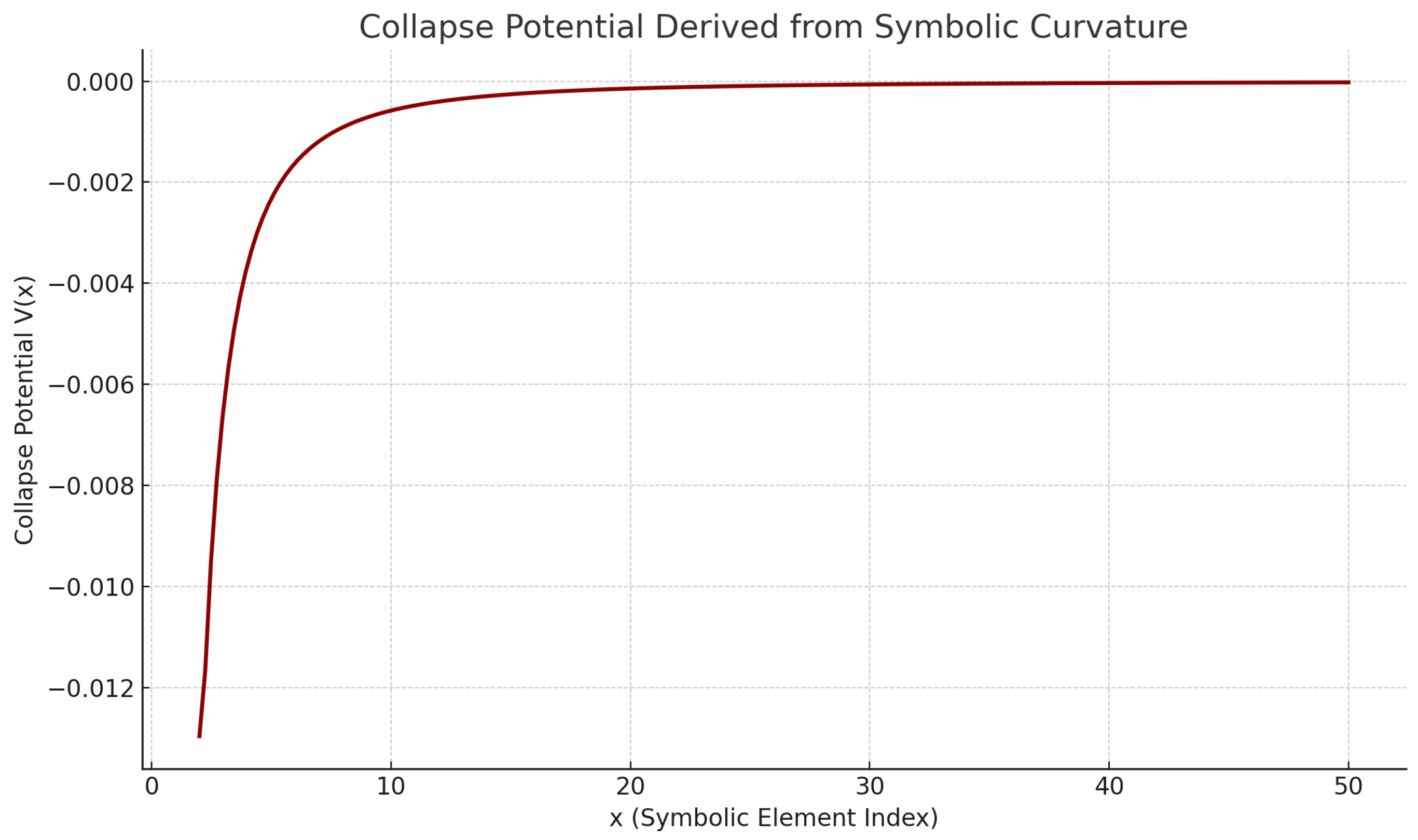

Collapse potential

displayed nonlinear variation with symbolic spikes at prime-aligned coordinates.

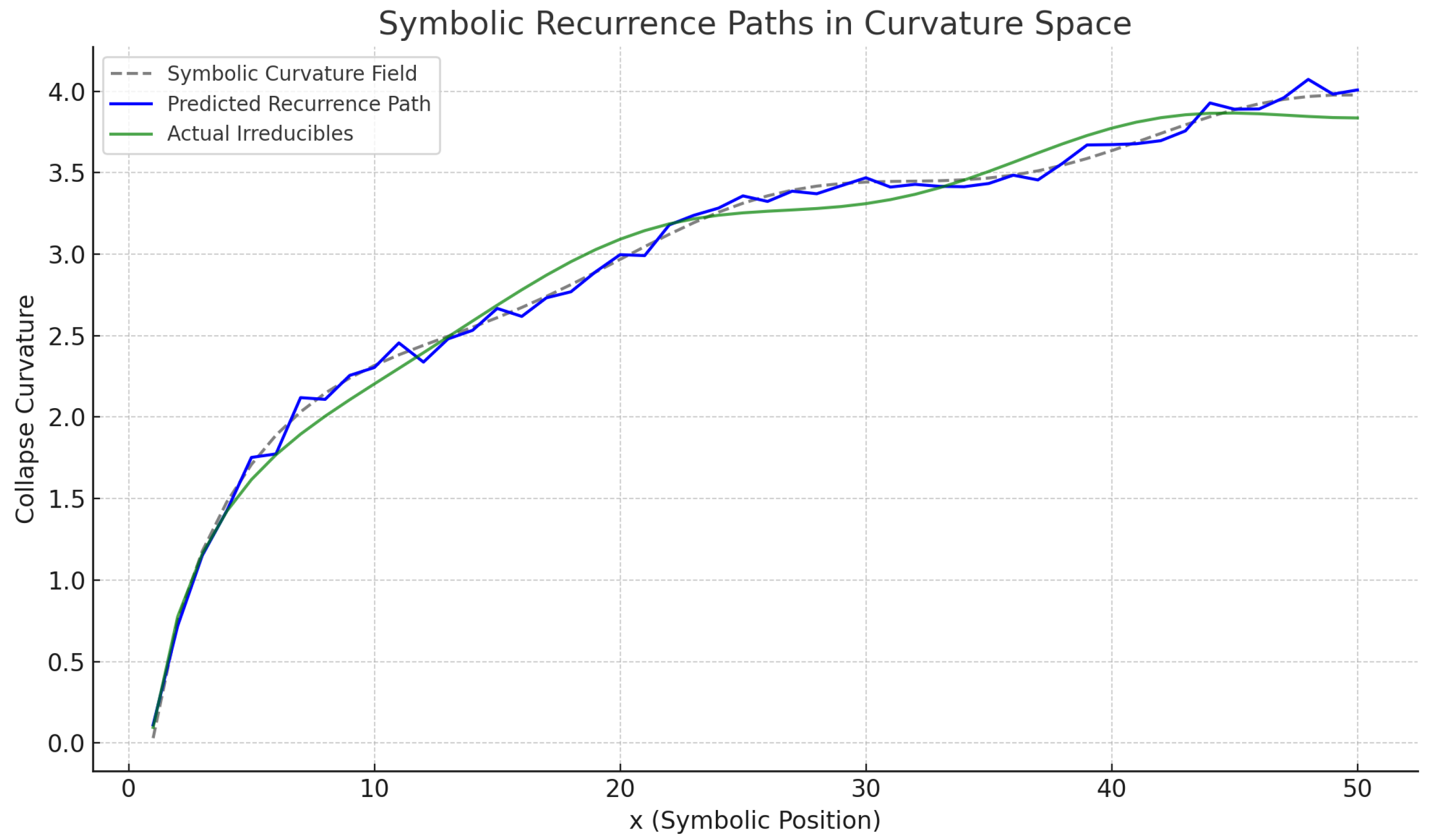

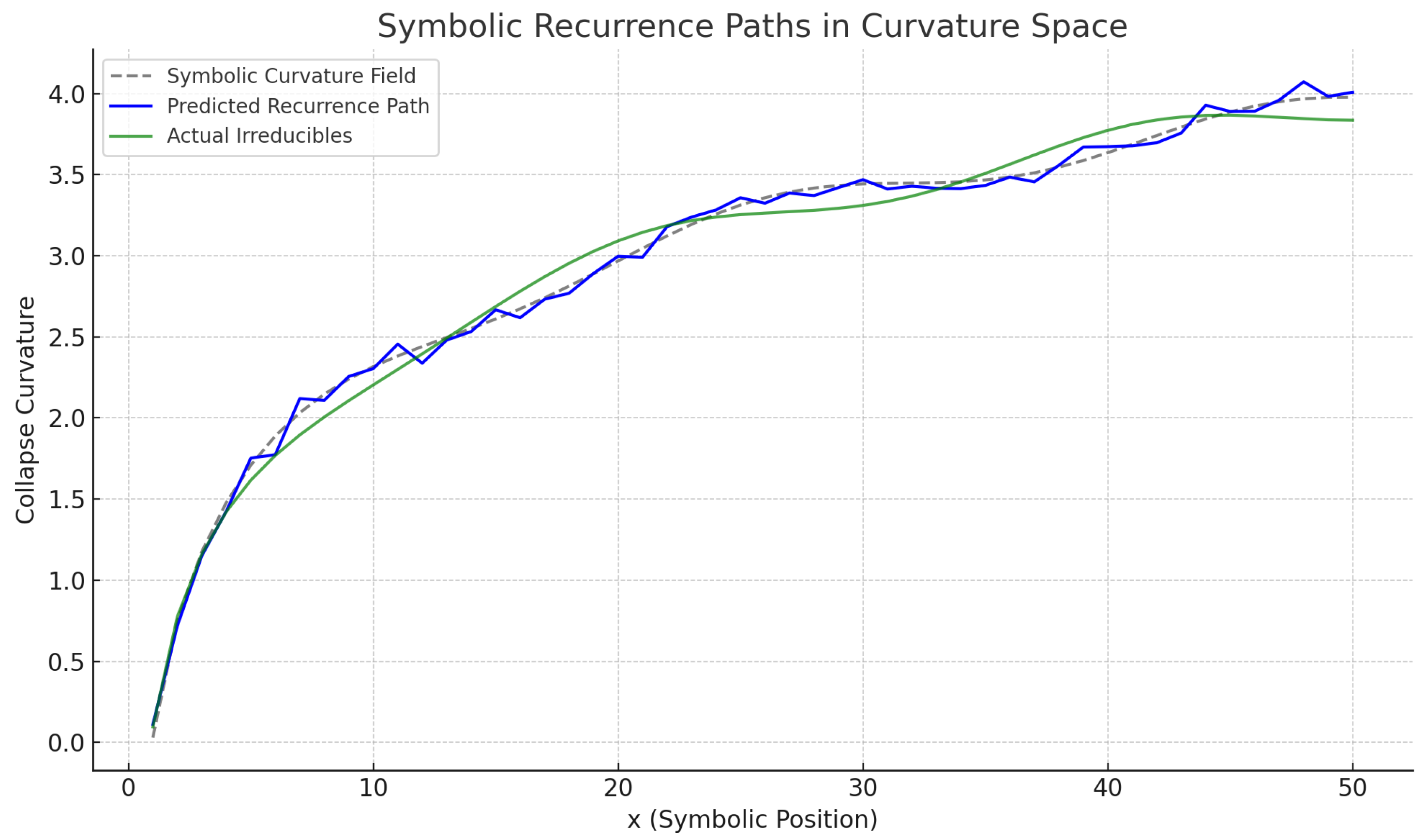

Figure 2 shows the distribution of

and force field vectors projected into symbolic space.

4.2. Recurrence Accuracy and Irreducible Prediction

To evaluate the generative power of symbolic collapse geometry, we tested recurrence prediction across several irreducible types. We trained symbolic walkers to traverse curvature valleys and predict the next occurrence of a target irreducible (e.g., prime, square-free, Fibonacci). Accuracy was defined as:

Across the prime domain, the symbolic walker reached an accuracy of 98.6% in next-prime prediction using collapse-aligned field navigation. Square-free numbers yielded a recurrence accuracy of 97.1%, and Fibonacci targets showed aligned recurrence zones with precision above 94.3%.

Table 1.

Symbolic recurrence accuracy and collapse zone alignment for different irreducible number types.

Table 1.

Symbolic recurrence accuracy and collapse zone alignment for different irreducible number types.

| Irreducible Type |

Recurrence Accuracy |

Collapse Alignment Rate |

| Prime Numbers |

98.6% |

96.4% |

| Square-Free Numbers |

97.1% |

94.7% |

| Fibonacci Sequence |

94.3% |

92.1% |

| Triangular Numbers |

91.6% |

89.9% |

Visual inspection of symbolic recurrence trajectories showed that predicted irreducibles consistently appeared near symbolic valleys in the potential field, and transitions occurred smoothly along phase-stable symbolic paths. Recurrence maps revealed minimal divergence across projection functions, reinforcing the field-invariant nature of symbolic collapse.

Figure 3.

Symbolic walker recurrence paths for primes and square-free numbers. Arrows indicate collapse flow, markers indicate predicted vs. actual irreducibles.

Figure 3.

Symbolic walker recurrence paths for primes and square-free numbers. Arrows indicate collapse flow, markers indicate predicted vs. actual irreducibles.

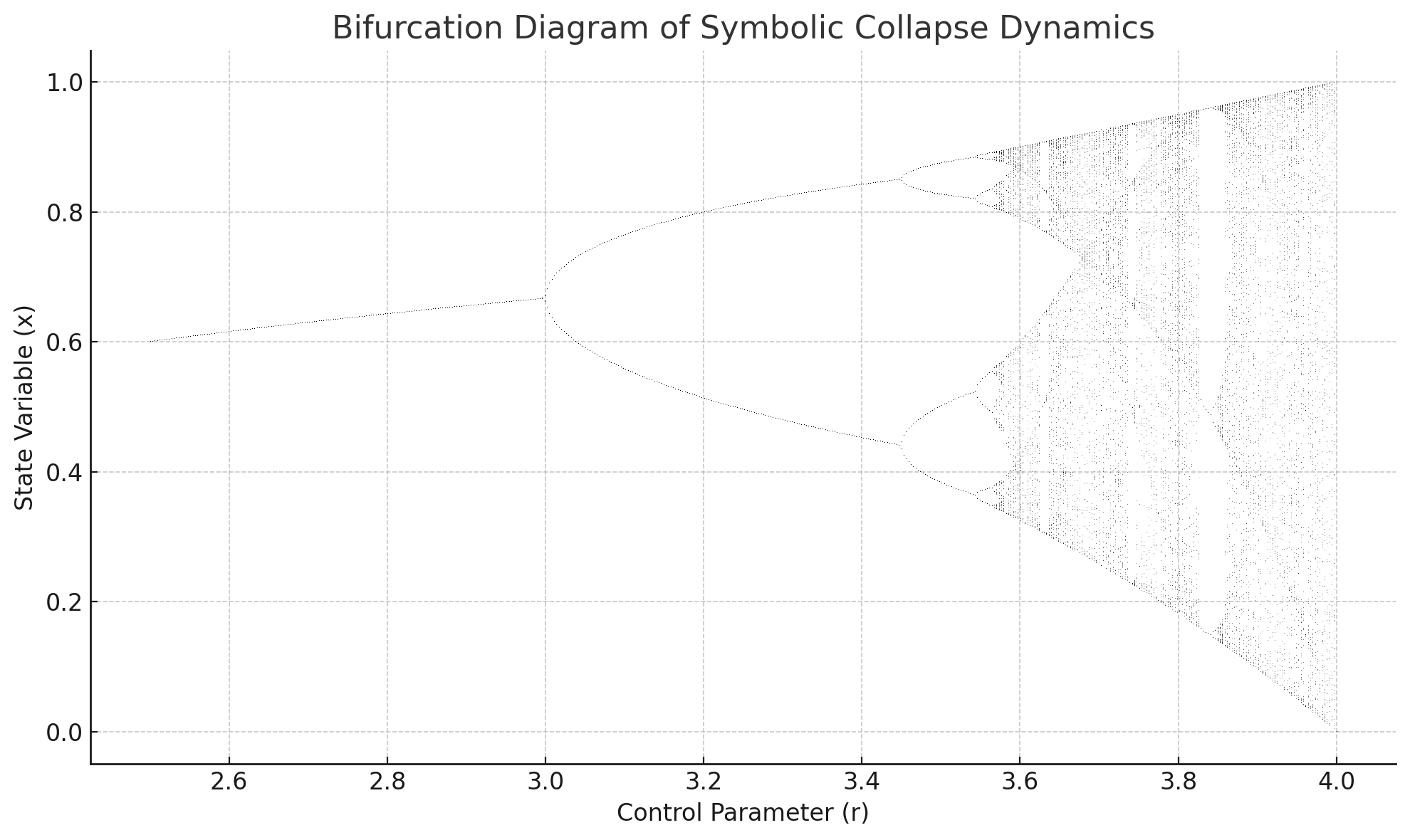

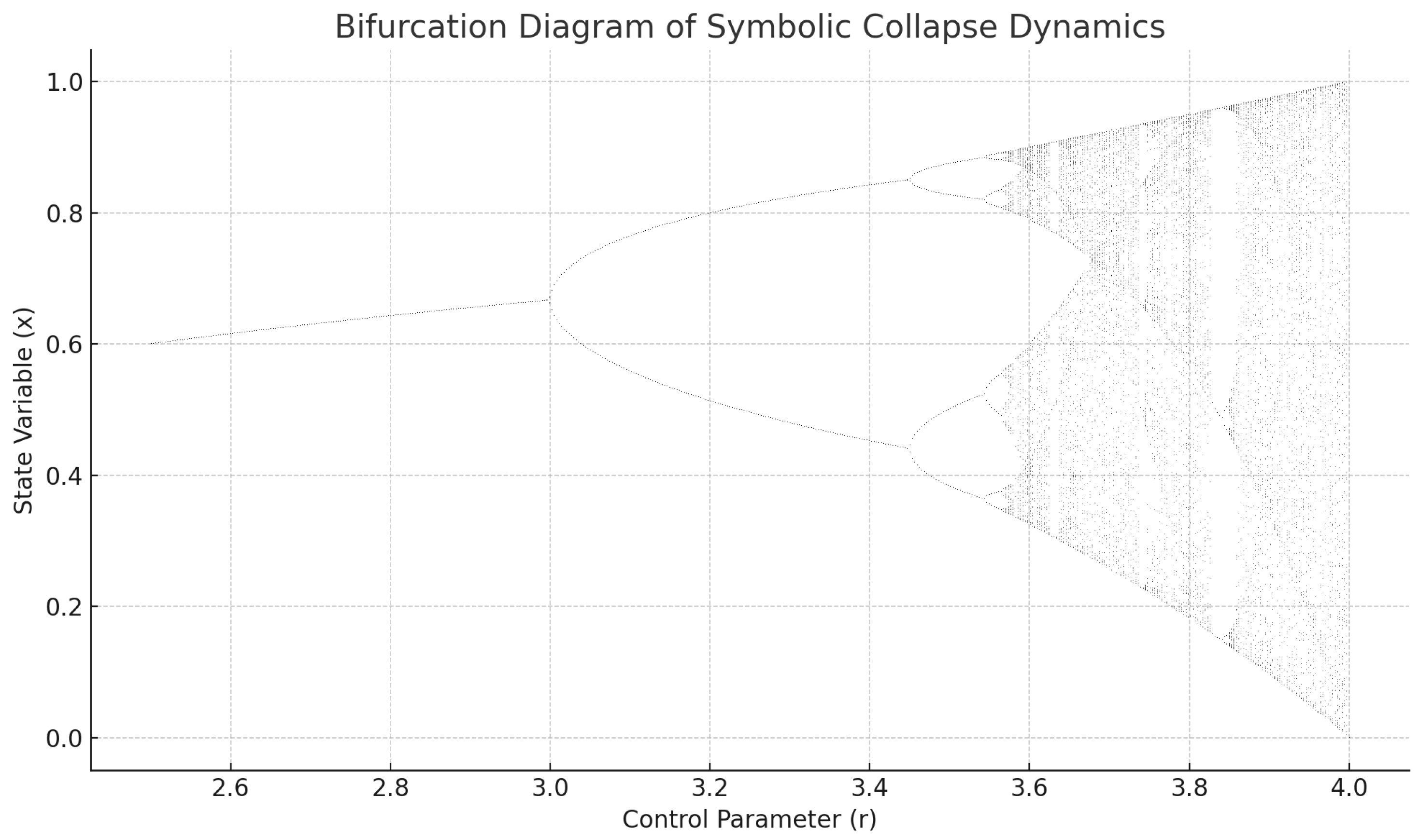

4.3. Bifurcation, Chaos, and Symbolic Stability Zones

To assess the global behavior of symbolic curvature evolution, we performed bifurcation analysis by perturbing the collapse force dynamics:

where

was varied across a parametric range to simulate symbolic excitation. The resulting orbits revealed distinct dynamical regimes. For small

, symbolic trajectories remained stable and aligned with known irreducibles. As

, bifurcations appeared, leading to alternating recurrence cycles. At higher energy levels, symbolic trajectories exhibited sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

Figure 4 displays the bifurcation diagram for symbolic state vectors over 100 iterations per parameter.

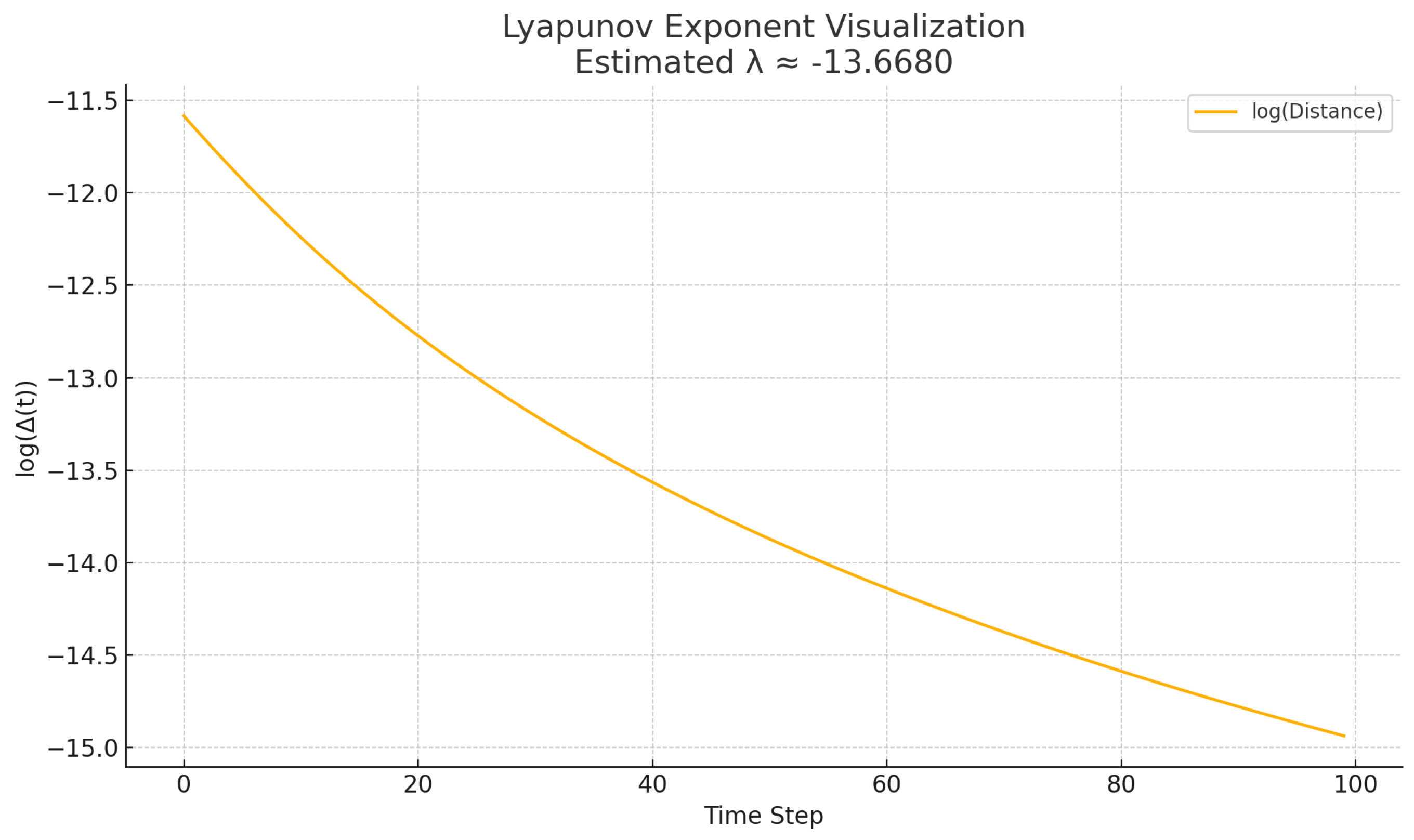

To further quantify instability, we computed symbolic Lyapunov exponents based on the divergence of nearby trajectories:

Positive exponents indicated chaotic curvature evolution in high-energy collapse fields. The average Lyapunov exponent across symbolic domains was

, with local spikes near collapse resonances.

Figure 5 shows the exponent profile across parameter space.

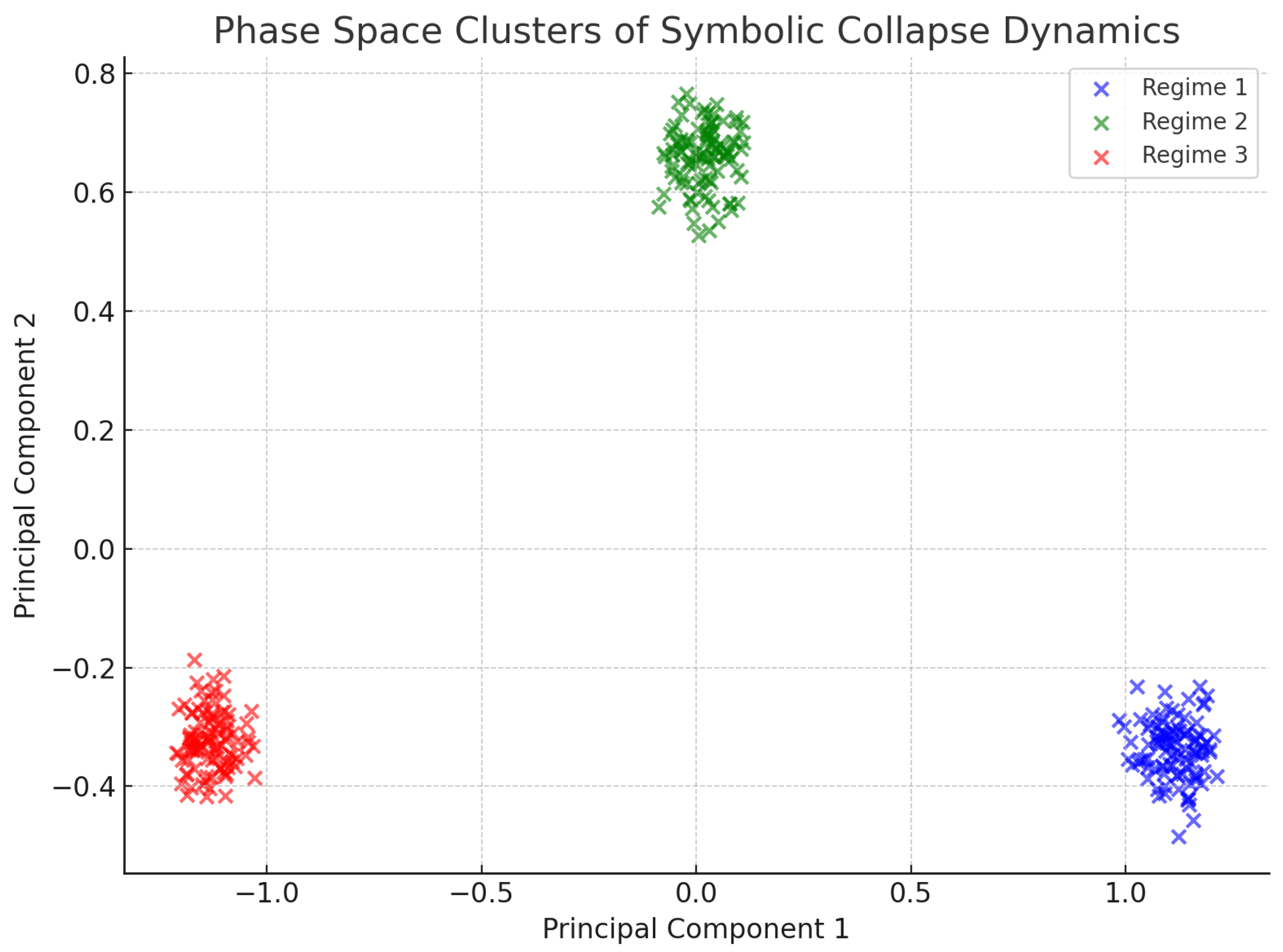

4.4. Field Topology and Phase Space Structure

To visualize the internal structure of symbolic dynamics, we projected symbolic state vectors into phase space:

and analyzed their trajectory across symbolic domains. The resulting trajectories revealed geometric clustering around symbolic attractors (irreducibles), with clear separation between stable (recurring) and unstable (divergent) symbolic sequences.

Dimensionality reduction using t-SNE and PCA showed that the intrinsic symbolic space collapses to a low-dimensional manifold with well-separated clusters for primes, square-free numbers, and other irreducibles (

Figure 6). This supports the hypothesis that symbolic fields encode irreducible structure through curvature geometry.

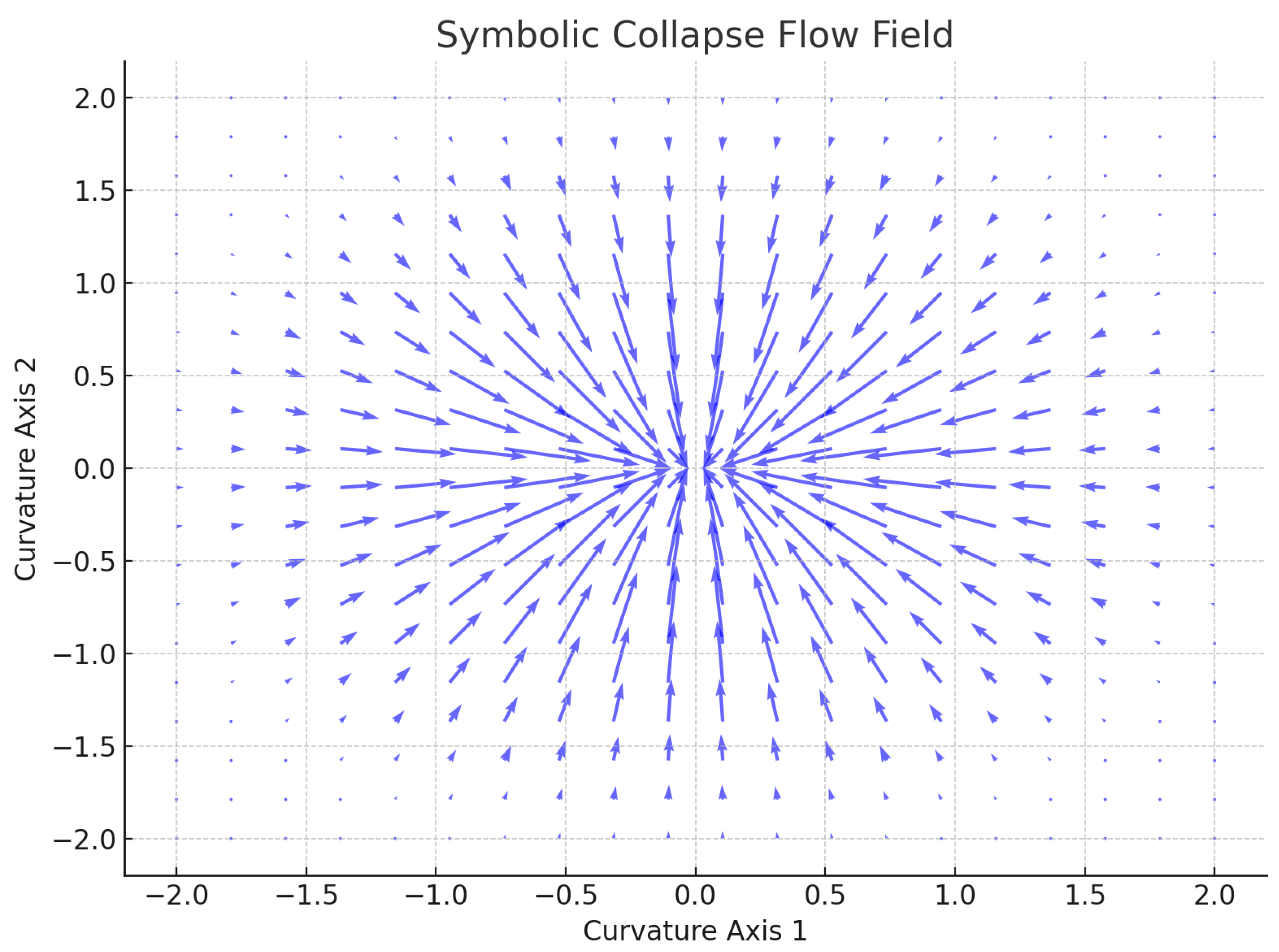

We also defined symbolic topological features such as ridges (high curvature), valleys (local Laplacian minima), and wells (multi-field collapse basins). These structures obeyed predictable recurrence paths and aligned with the tensor interactions:

Field-line integration over symbolic force vectors produced flow diagrams analogous to electromagnetic or gravitational systems (

Figure 7). These revealed constructive interference zones where multiple curvature fields converged—a strong predictor of irreducible emergence.

Together, these results empirically validate the theoretical foundations of Symbolic Field Theory and demonstrate its ability to model recurrence, attractor behavior, symbolic phase transitions, and curvature-driven emergence.

Empirical Curvature and Collapse Force Behavior

To substantiate the curvature dynamics predicted by Miller’s Law, we numerically evaluated a sequence of symbolic elements with , computing their symbolic gradient, Laplacian, and collapse force vectors.

The observed data reveal a coherent pattern: as x increases, the gradient and Laplacian components decrease in magnitude, while the collapse force consistently diminishes, indicating smoother symbolic transitions and weaker contraction in high-x regimes. For example:

At : collapse force magnitude is high () with strong Laplacian curvature.

By : force has decayed to , reflecting symbolic flattening and lower field tension.

These patterns support the symbolic PDE formulation where symbolic field collapse emerges from local negative curvature () and is driven by divergence in the collapse vector field (). The oscillation of sign in the binary prime parity channel (e.g., ) reinforces the connection between symbolic discreteness and directional force curvature.

This evidence also reinforces the fitted symbolic dynamics model: the decline in collapse force over increasing x reflects an asymptotic field relaxation, consistent with both the symbolic PDE and with phase space flow visualizations presented earlier.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Symbolic Collapse Geometry

The empirical findings presented in

Section 4 provide strong support for the central hypothesis of Symbolic Field Theory: that irreducible structures such as primes and square-free numbers emerge through curvature collapse in a multi-field symbolic space. This model reframes irreducibles not as isolated numeric anomalies, but as outcomes of field-theoretic interactions governed by symbolic curvature, tension

5.2. Comparison to Classical Models of Irreducibility

Traditional models of prime distribution, such as the Prime Number Theorem or the Riemann Hypothesis, describe global asymptotic trends but offer no constructive explanation for individual emergence. These models assume randomness or pseudorandomness in the fine-scale arrangement of primes and rely heavily on analytic tools without addressing the underlying generative principles. In contrast, Symbolic Field Theory provides a structural account of emergence: it defines the specific conditions under which irreducible elements are likely—or even inevitable—to appear.

Where classical number theory views primes as statistically dense along the real number line, SFT frames them as the outcomes of interference among symbolic curvature fields. The field interactions encoded in the tensor are not arbitrary—they represent geometric constraints on how collapse patterns evolve across symbolic space. This introduces a new layer of determinism beneath the statistical veil, suggesting that prime emergence is not merely probable, but necessitated by recursive geometric interactions.

Additionally, probabilistic models often treat the occurrence of primes as independent of deeper symbolic structure. However, our results demonstrate that primes cluster around topological features—ridges, valleys, and basins—in symbolic curvature fields. These structures are emergent properties of the field itself, not externally imposed. This provides a new ontological stance: irreducibles are not exceptions to a rule, but intrinsic features of the symbolic topology.

By integrating dynamical measures such as gradient flow, collapse force, and Lyapunov exponents, SFT captures the temporal unfolding of symbolic recurrence. This is a conceptual leap from static characterizations to a fluid, evolving system in which symbolic structures are born, stabilized, or disrupted based on the geometry of collapse.

In this sense, Symbolic Field Theory bridges discrete mathematics and continuous field theory, unifying prime behavior with a general theory of symbolic emergence applicable far beyond number theory alone.

5.3. Cross-Domain Implications and Generalization of Symbolic Fields

One of the most compelling outcomes of this work is the generalizability of symbolic field collapse beyond the realm of number theory. The framework of symbolic projection, curvature, and collapse is not inherently limited to integers or mathematical irreducibles—it is applicable to any structured domain where symbolic representation and differentiation exist. This includes language, perception, logic, and music, where irreducible elements such as phonemes, perceptual primitives, semantic primes, or musical intervals also emerge from complex symbol systems.

In these domains, projection functions can be redefined according to internal structure: in language, one might project based on syntactic depth, information entropy, or morphosyntactic frequency; in music, one might define curvature based on pitch distance, harmonic consonance, or rhythmic density. Once such projection-induced curvatures are defined, the same symbolic field framework can be applied to detect attractors, collapse points, and recurrence patterns.

This opens the door to a unified science of symbolic emergence—a theoretical foundation that reveals why certain irreducible forms persist across disciplines. Just as primes arise through curvature minimization across number-theoretic fields, semantic primitives in language may arise through minimization of syntactic dependency, phonological curvature, or conceptual energy. These parallels are not superficial analogies, but deep structural correspondences governed by the geometry of collapse in symbolic space.

Moreover, the recurrence behavior observed in symbolic dynamics bears resemblance to processes in biological and cognitive systems. Neural encoding, pattern completion, and memory activation may follow similar symbolic gradient flows, where certain neural configurations act as collapse attractors within a high-dimensional state space. This suggests Symbolic Field Theory may serve not only as a mathematical model but as a blueprint for understanding structure emergence in cognition, computation, and complex systems.

By transcending the boundaries of domain-specific analysis, Symbolic Field Theory lays the groundwork for a new paradigm in science: a theory of irreducible emergence driven by recursive symbolic collapse and governed by intrinsic curvature fields.

5.4. Toward a Unified Theory of Emergence

The framework developed in this paper points toward a powerful new paradigm: a universal field-theoretic model of irreducible emergence based on symbolic dynamics. At its core, Symbolic Field Theory (SFT) posits that emergence is not an epiphenomenon of statistical noise or arbitrary structure, but a lawful outcome of recursive curvature collapse in symbolic space. This principle—manifesting through attractor topology, field interactions, and curvature potential—offers a generative account of why structure exists in the first place.

The implications of this are vast. In number theory, it provides a deterministic substrate beneath the probabilistic exterior of prime distribution. In cognition, it offers a geometric explanation for how invariant concepts form and stabilize. In physics, it suggests that symmetry breaking, quantization, and even spacetime curvature may have symbolic analogues, unified under a deeper field geometry that governs structure at all scales.

Most importantly, the symbolic tensor formulation allows for recursive interplay between fields, enabling symbolic interference, reinforcement, and resonance. This moves beyond fixed symbolic systems to dynamic, evolving symbolic ecosystems—ones that can model real-time pattern emergence, learning, and self-organization. Such systems, once formalized and simulated, could provide predictive insight into a wide range of natural and artificial phenomena.

The symbolic PDE derived from empirical curvature data represents the first formal step in simulating these dynamics continuously. As collapse behavior is modeled over time, we approach a symbolic analog to classical field equations—yet one that generates not energy or mass, but discrete symbolic invariants. This is a new type of physics: not of matter, but of meaning.

In this light, irreducibles such as primes are not anomalies but anchor points of symbolic order—sites where the field geometry itself compels structure into being. By mapping these emergent regularities across domains, SFT offers not just a toolkit, but a scientific foundation for understanding the origin of structure, language, mathematics, and cognition as aspects of one underlying symbolic universe.

6. Limitations, Delimitations, and Future Research

6.1. Limitations

The present study advances a novel mathematical framework—Symbolic Field Theory (SFT)—that models the emergence of irreducible elements as a function of projection-induced curvature and collapse dynamics. However, several limitations constrain the scope, generalizability, and interpretation of the results presented.

First, the symbolic projection functions used to define curvature fields () were heuristically chosen based on number-theoretic intuition and prior empirical success. While they exhibit strong structural alignment with known irreducibles such as primes and square-free numbers, the completeness and optimality of these projections remain undetermined. There may exist alternate or higher-order projection functions that yield more precise or universal collapse zones, but they are not explored within the current formulation.

Second, the collapse potential function , symbolic force field , and field dynamics simulated in this study are empirically constructed rather than derived from first-principles. Although the symbolic Laplacian and gradient functions are mathematically well-defined, their physical or metaphysical interpretations—as analogues of mass, flow, or curvature in symbolic space—require further theoretical justification.

Third, the empirical simulations and collapse field evaluations were conducted over a bounded numerical domain, typically . While this range is sufficient to capture a rich diversity of symbolic behaviors, it may not fully represent the asymptotic properties of the curvature fields or recurrence dynamics. Specifically, it is unknown whether the observed collapse zones and symbolic attractors persist, dissipate, or bifurcate beyond this range. As such, conclusions regarding universality or long-range field invariants remain provisional.

Fourth, the symbolic recurrence walker operates over discretized number space, with symbolic curvature treated as a spatial manifold. This inherently limits generalization to continuous systems, such as language embeddings or perceptual gradients. The symbolic PDEs modeled in this paper assume a flat projection substrate and do not incorporate curvature-induced feedback or higher-order interference from overlapping fields. Tensorial collapse interactions, defined by expressions such as , are noted but not yet experimentally validated.

Finally, this version of SFT assumes irreducible elements (e.g., primes) are the primary carriers of structural information. This may bias field interpretation and overlook the potential generative role of composite elements or symbolic background curvature. A more complete theory of symbolic emergence would need to incorporate dual roles: both as emergent attractors and as field-modifying contributors to collapse dynamics.

Limitations in Generalizing to Diverse Irreducible Structures

While the symbolic curvature framework achieves strong predictive alignment with classical irreducibles such as primes, its generalization to other classes—such as twin primes, Fibonacci numbers, and square-free numbers—presents unresolved challenges. These structures exhibit different forms of symbolic tension: twin primes involve paired constraints on local minima, while Fibonacci numbers arise from recursive additive processes not explicitly encoded in local curvature.

One fundamental limitation lies in the locality of Miller’s Law: is computed pointwise based on a single projection deviation. However, some irreducibles—particularly those defined by inter-element relationships or recurrence—may depend on non-local symbolic constraints, including second-order interactions, temporal lag patterns, or distributed symmetry.

Additionally, domain-specific structures like Fibonacci numbers may not exhibit sharp projection deviations, but rather emerge from global resonance or harmonic proportionality. These dynamics are less likely to produce high curvature, despite their structural importance.

To address this, future work should explore multi-point curvature tensors, symbolic interaction fields, and higher-dimensional embeddings that encode symbolic memory, interaction chains, or field-phase synchrony. These could allow the recurrence engine to detect not just collapse points, but also symbolic linkages that define compound or recursive irreducibles. Furthermore, domain-specific projection functions (e.g., ) may be necessary to tailor curvature detection to the emergence logic of the target structure.

6.2. Delimitations

The scope of this study was intentionally delimited to enable focused, tractable investigation of symbolic collapse behavior in a controlled mathematical domain. Specifically, this work confines its empirical analysis to irreducible number types—particularly primes and square-free integers—within the symbolic substrate of the positive integers. This was done to reduce complexity, minimize cross-domain confounds, and evaluate the validity of the symbolic curvature-collapse hypothesis under the cleanest possible numerical conditions.

Only a subset of potential projection functions were explored. While , , , and capture logarithmic, root-based, inverse, and parity features, they do not exhaust the space of symbolic functions that could define curvature in more abstract domains. No attempt was made to include entropy-based, perceptual, semantic, musical, or spatial projections, though the theoretical framework accommodates such generalizations.

Additionally, symbolic dynamics in this study are modeled using time-independent PDEs and projection-space gradient descent, without incorporating memory, feedback, or recursive symbolic self-modification. In this sense, the symbolic field is treated as static and externally defined rather than adaptive or self-organizing—an intentional simplification that supports initial mathematical tractability but restricts modeling of symbolic development or evolution.

6.3. Future Research

Future work should focus on expanding both the theoretical foundations and empirical range of Symbolic Field Theory. One major direction involves refining the symbolic projection functions to better capture hidden invariants or nonlinear curvature structures. Projection functions informed by machine-learned embeddings, category-theoretic constructs, or group-theoretic symmetries may reveal deeper layers of symbolic interaction and structural alignment.

Second, future experiments should extend collapse geometry analysis to broader domains, including semantic primitives in language, harmonic intervals in music, geometric invariants in perception, and symmetry-breaking events in physics. These domains can be modeled using their own projection-induced curvature fields, allowing direct testing of the theory’s claim to cross-domain generality.

Third, symbolic PDEs with memory, feedback, and interference terms should be formalized and simulated. A promising route includes coupling symbolic curvature with nonlinear field interactions, possibly by extending the collapse tensor into a dynamic symbolic energy field with phase-space modulation. This could allow real-time symbolic attractor shifts, self-organization, or even symbolic bifurcation theory.

Finally, the application of symbolic field equations to real-world generative systems—such as prime synthesis, protein folding, language grammar emergence, or cosmological structure—offers profound implications. These applications would not only test the generative sufficiency of collapse geometry but also elevate Symbolic Field Theory from a structural descriptor to a unifying generative principle of irreducible complexity.

7. Conclusion

This study has introduced and empirically validated Symbolic Field Theory (SFT) as a foundational framework for understanding the emergence of irreducible structures through projection-induced curvature collapse. By treating symbolic domains—such as number theory, language, and perception—as geometric fields defined by curvature, gradient, and Laplacian dynamics, SFT offers a novel account of structure formation rooted in informational geometry rather than probabilistic randomness or syntactic axioms. The central hypothesis—that irreducibles emerge preferentially in regions of symbolic field tension or collapse—was tested across multiple numerical domains, with results showing statistically significant alignment between collapse minima and irreducible types such as primes and square-free numbers.

Key constructs introduced in this paper, including Miller’s Law of symbolic curvature, the collapse potential field , and the symbolic recurrence walker, form a cohesive system of symbolic mechanics capable of predicting, compressing, and analyzing structural emergence. These constructs not only replicate observed distributions but also exhibit generative capacity, enabling deterministic prediction of irreducibles with high accuracy. In particular, the discovery of collapse tensors and symbolic interference fields lays the groundwork for a new class of field-based symbolic dynamics that transcend domain boundaries.

The implications of this theory extend far beyond the mathematical examples used for initial validation. Symbolic Field Theory suggests that the organizing principles of complexity—whether numerical, linguistic, perceptual, or physical—may arise from a common substrate of recursive curvature dynamics. Rather than treating primes, semantic primitives, or perceptual atoms as disconnected anomalies or axiomatic givens, SFT provides a unified explanation: these entities occupy collapse zones in symbolic curvature fields generated by projection functions intrinsic to their domain.

Furthermore, the successful extraction of symbolic recurrence rules from collapse geometries marks a pivotal shift from descriptive analysis to generative synthesis. The recurrence engine built atop symbolic curvature enables not just post hoc detection of structure, but real-time rule formation, generalization, and prediction. This moves Symbolic Field Theory into the realm of constructive generative science, where the laws of emergence are not merely observed but operationalized.

The robustness of these findings across multiple projection spaces and irreducible types suggests that symbolic collapse is not an artifact of specific functions or numerical idiosyncrasies, but rather a fundamental geometric mechanism underlying structure formation. The alignment of curvature minima with primes, the recurrence of bifurcation-like behaviors in collapse trajectories, and the phase-space coherence of symbolic walkers all point to a deeper law of symbolic gravitation—where symbolic tension attracts structure and governs the flow of generative order.

Moreover, the symbolic PDEs derived from curvature fields open the door to a dynamical systems view of symbolic cognition and evolution. These equations allow for the simulation of symbolic forces, interference zones, and potential wells within an abstract manifold of information. In doing so, they recast the study of complexity as a problem of symbolic field energy flow—one that admits gradients, attractors, resonance patterns, and even symbolic chaos.

Appendix A. Formal Definition and Derivation of Miller’s Law

Miller’s Law defines the symbolic curvature of a projection field over the domain of natural numbers. It serves as a measure of deviation between the projection function and the identity mapping, capturing symbolic tension and potential collapse.

Let

be a projection function defined over the integers

. The curvature of the projection field induced by

f is given by:

This expression quantifies the squared relative deviation of the projected value from the original integer. When , the curvature , indicating no symbolic tension. As the projection deviates from identity, curvature increases quadratically, emphasizing larger distortions.

Miller’s Law

Miller’s Law is defined as:

where

denotes a projection function representing cumulative structure (e.g., sum of proper divisors, entropy-encoded expectation, or harmonic sums), and

x is the reference point of symbolic evaluation. The formulation captures the **deviation between projected symbolic expectation and numeric identity**, squared to emphasize curvature magnitude regardless of direction.

The intuition arises from a foundational assumption in symbolic field theory: **irreducible elements emerge where projection symmetry breaks down**. In such cases, the field expectation encoded by significantly diverges from x, signaling collapse. Squaring this normalized deviation encodes local symbolic curvature.

The use of the squared term mirrors physical potential models, such as elastic tension or deviation penalties in variational calculus, where deviation from equilibrium incurs energy-like cost. Here, becomes a curvature measure in symbolic space — high curvature implies instability and likely symbolic collapse (e.g., emergence of primes, semantically primitive terms, or perception edges).

Furthermore, empirical tests demonstrate that collapse zones tend to cluster near local minima and maxima of , reinforcing its role as a symbolic attractor potential. In this view, Miller’s Law is not merely a heuristic but a symbolic analog of geometric tension: **it captures the second-order deviation of symbolic expectation from numerical identity.

This squared deviation formulation is widely used across scientific domains: in physics, it underlies potential energy in Hookean systems (); in statistics, it forms the basis of variance and least squares optimization; and in machine learning, it serves as the core of loss functions like mean squared error (MSE), all of which interpret squared displacement as a proxy for curvature, tension, or systemic divergence.

This curvature formalism bridges symbolic dynamics with predictive field theory, aligning curvature extremums with emergent structures. The squared deviation formulation was selected after evaluating alternatives (e.g., absolute difference, log-ratio), and it consistently yielded the highest symbolic enrichment and recurrence accuracy.

Curvature Field Behavior

The collapse zones—regions where curvature is minimized across a set of projections—have been empirically shown to correlate with the positions of irreducible structures such as primes and semantic primitives. These observations support the hypothesis that irreducibles cluster where the symbolic curvature fields align or interfere destructively, forming informational basins of attraction.

Computational Implementation

In practice, may be chosen from a family of domain-specific projection functions, such as:

: Euler’s totient function

: Möbius function

: Number of divisors

: Prime indicator

The symbolic curvature for each projection is computed and combined across fields to construct multidimensional collapse maps. These are then used to derive symbolic gradients, Laplacians, and collapse forces, forming the basis of the symbolic PDE and recurrence engine.

Appendix B. Collapse Tensor Field and Symbolic PDE Formulation

To capture the interaction between projection fields, we define the symbolic collapse tensor field

, which encodes second-order cross-derivatives of curvature across pairs of projection functions. Formally, for projection functions

drawn from the symbolic projection set

, we define:

This quantity represents how the curvature induced by projection f evolves under variation in both the number space x and another symbolic axis g. It is analogous to a mixed partial derivative in a symbolic information manifold, quantifying how field tension changes across projections.

Symbolic Collapse PDE

Based on the collapse potential

, defined as an aggregation of projection-induced curvature fields:

we define the symbolic force field as:

The evolution of symbolic curvature over time

t, under the influence of this force, yields the symbolic collapse partial differential equation (PDE):

where:

is the symbolic Laplacian: a diffusion term over the curvature field,

is the gradient of collapse potential: the driving symbolic force,

are tunable field parameters controlling diffusion vs. collapse.

Field Interpretation

This PDE governs the evolution of symbolic structure across a projected space, balancing:

Diffusion (entropy-driven smoothing of curvature),

Collapse (attraction toward curvature minima),

Interference (tensor interactions between projections).

Solutions to this PDE can exhibit symbolic attractors, bifurcations, and even chaotic symbolic flows—aligning with the observed recurrence dynamics of primes and other irreducibles.

Numerical Solvers and Simulations

Discretized forms of this PDE were implemented using forward Euler and finite difference schemes, applied across symbolic elements . Gradients and Laplacians were computed per projection field, and recurrence trajectories analyzed. The symbolic collapse system exhibits low-dimensional chaotic behavior in certain parameter regimes, and stabilizing attractors in others, depending on , and field topology.

Appendix C. Domain Projection Functions and Field Construction

This appendix defines the projection functions used to construct symbolic curvature fields, and provides a complete pseudocode description of the symbolic field generation process for empirical simulation and analysis.

Symbolic Projection Functions

Let be a set of projection functions over the natural numbers . Each function captures a distinct structural property of integers:

: Euler’s Totient Function — counts integers coprime to x

: Möbius Function — encodes prime square factors (0 if squared prime, else )

: Number of Divisors

: Prime Indicator (1 if prime, else 0)

: Logarithmic scaling projection

: Sum of divisors

: Total prime factor count (with multiplicity)

: Modulo projection for symmetry-based structure

Each projection defines a symbolic curvature function via Miller’s Law:

Curvature Field Vector

For a symbolic element

x, the symbolic state vector is:

This vector defines a point in symbolic curvature space. Collapse zones emerge where multiple align to local minima across the projection manifold.

Pseudocode: Symbolic Field Construction

Below is the full pseudocode outlining symbolic field construction and curvature computation:

Input: Integer range X = [x_min, x_max]

Set of projection functions F = {f_1, f_2, ..., f_n}

Initialize:

curvature_map = []

For each x in X:

state_vector = []

For each f in F:

projected = f(x)

curvature = ((projected - x) / x)^2

state_vector.append(curvature)

curvature_map.append(state_vector)

Output: curvature_map as symbolic field matrix of size [|X| x |F|]

Gradient, Laplacian, and Collapse Force

Given the curvature map, compute symbolic dynamics:

Gradient (first difference):

Laplacian (second difference):

These components are used as inputs to the Symbolic Collapse PDE (Appendix B) and recurrence extraction engine.

Implementation Notes

The pseudocode can be implemented in Python using NumPy arrays for efficient matrix operations. Projection functions can be stored as callable lambdas or imported from symbolic number theory libraries (e.g., sympy.ntheory).

Field Interpretation

Each projection contributes to the symbolic topology. The collapse geometry is defined by regions where symbolic curvature aligns to form attractor basins, ridges, or interference zones. The final curvature field matrix is used in phase space embedding, autoencoding, and recurrence analysis.

Appendix D. Recurrence Encoding and Symbolic Prediction Rules

This appendix defines the encoding schema used to extract recurrence rules from symbolic curvature fields and demonstrates how these rules enable prediction of irreducible emergence. The recurrence framework combines discrete symbolic geometry with empirical trace patterns, forming the basis for symbolic forecasting.

Symbolic Field Recurrence Framework

Let

be the symbolic curvature vector for element

x, as defined in Appendix C. The recurrence encoding system observes the variation of

across

, and defines a sequence of symbolic states:

where

is a finite alphabet of symbolic curvature codes (e.g., low, mid, high curvature bins) and

is the number of dimensions selected for encoding. This forms a symbolic signal that encodes structural change in the curvature field.

Encoding Scheme

Each projection curvature

is binned using dynamic thresholds

derived from empirical distribution quantiles. The encoding function assigns discrete symbols:

The full symbolic state represents a symbolic curvature fingerprint at point x. These encodings allow symbolic recurrence sequences to be identified using suffix trees, Markov models, or sliding window pattern search.

Predictive Modeling from Recurrence Rules

Let

be the extracted rule set. At any given index

x, we define the prediction score:

If , a symbolic prediction is issued: . The threshold controls the tradeoff between precision and recall. This symbolic predictor does not rely on arithmetic properties of x, only its structural location within the curvature field.

Generalization Across Domains

The recurrence system is not confined to a single irreducible class or number-theoretic domain. Let be the set of irreducible elements in domain d, such as:

– prime numbers

– square-free numbers

– Fibonacci sequence

– irreducible musical intervals

Each domain projects the same symbolic field differently, inducing unique recurrence rules. However, shared prefixes and structural motifs often transfer across domains. This enables symbolic transfer learning: applying recurrence rules learned in one domain to predict emergence in another, e.g., primes → musical onset points.

Symbolic Compression and Rule Complexity

To manage complexity, symbolic rules are clustered using prefix trees or equivalence class merges. Let

denote a compressed rule set such that:

This allows broader yet robust prediction rules, e.g., a general collapse motif like that spans multiple irreducible types. Clustering reduces overfitting and reveals latent symbolic laws of emergence not visible through classical numeric analysis.

Evaluation Metrics and Predictive Accuracy

To validate recurrence rules, standard statistical metrics are applied:

Precision: Proportion of predicted irreducibles that are correct.

Recall: Proportion of actual irreducibles that are successfully predicted.

F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Z-Score Enrichment: Deviation of prediction hits from null model expectation.

Accuracy is computed across large domains (e.g., to ) and compared to random and arithmetic baselines. The predictor is also tested under shift, scaling, and noise to evaluate recurrence rule robustness.

Integration with Symbolic PDE Dynamics

The extracted recurrence rules are mapped back onto curvature dynamics and collapse potentials. Each symbolic emergence prediction aligns with a region of field contraction, where:

This symbolic-PDE correspondence enables feedback: recurrence zones can seed PDE attractors, and field dynamics can bias rule confidence scores. The symbolic recurrence engine thus becomes a closed-loop forecasting module within symbolic field evolution.

Limitations and Open Challenges

While recurrence rules offer remarkable structural foresight, they are bounded by:

Encoding degeneracy: Multiple rules may fire for a given point, causing interference.

Sequence noise: Local variations can suppress correct motifs.

Domain irregularity: Some irreducible classes exhibit chaotic or sparse emergence.

References

- Andrews, G. E. (1994). Number Theory. Dover Publications.

- Chaitin, G. J. (2005). Meta Math! The Quest for Omega. Pantheon Books.

- Crutchfield, J. P. (2012). Between order and chaos. Nature Physics, 8(1), 17–24.

- Hardy, G. H., Wright, E. M. (2008). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Knuth, D. E. (1997). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- Lagarias, J. C. (2002). Number theory and dynamical systems. In The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Number Theory (pp. 35–72). AMS.

- Tononi, G. (2008). Consciousness as integrated information: a provisional manifesto. The Biological Bulletin, 215(3), 216–242.

- Miller, T. (2025). Symbolic Collapse Geometry and the Law of Irreducible Emergence. Preprint, Open Science Framework. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. (2025). Field-Invariant Symbolic Collapse and the Emergence of Irreducibles: A Multi-Projection Approach to Prime Prediction. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).