Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Framework

2.1. Finite Element Method

2.2. Finite Element Formulation for Stiffened Panels under Torsional Loads

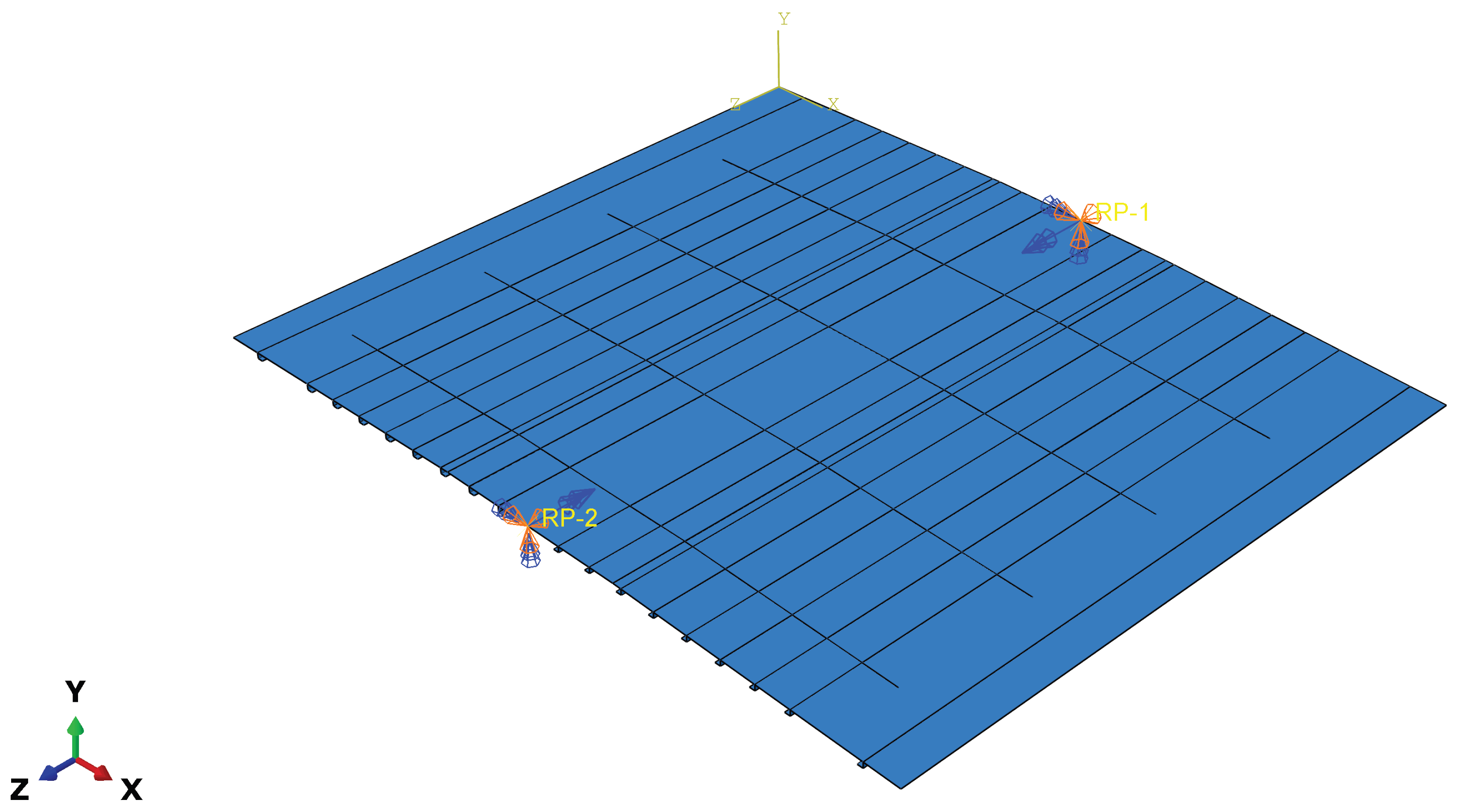

2.3. Boundary Conditions and Load Application

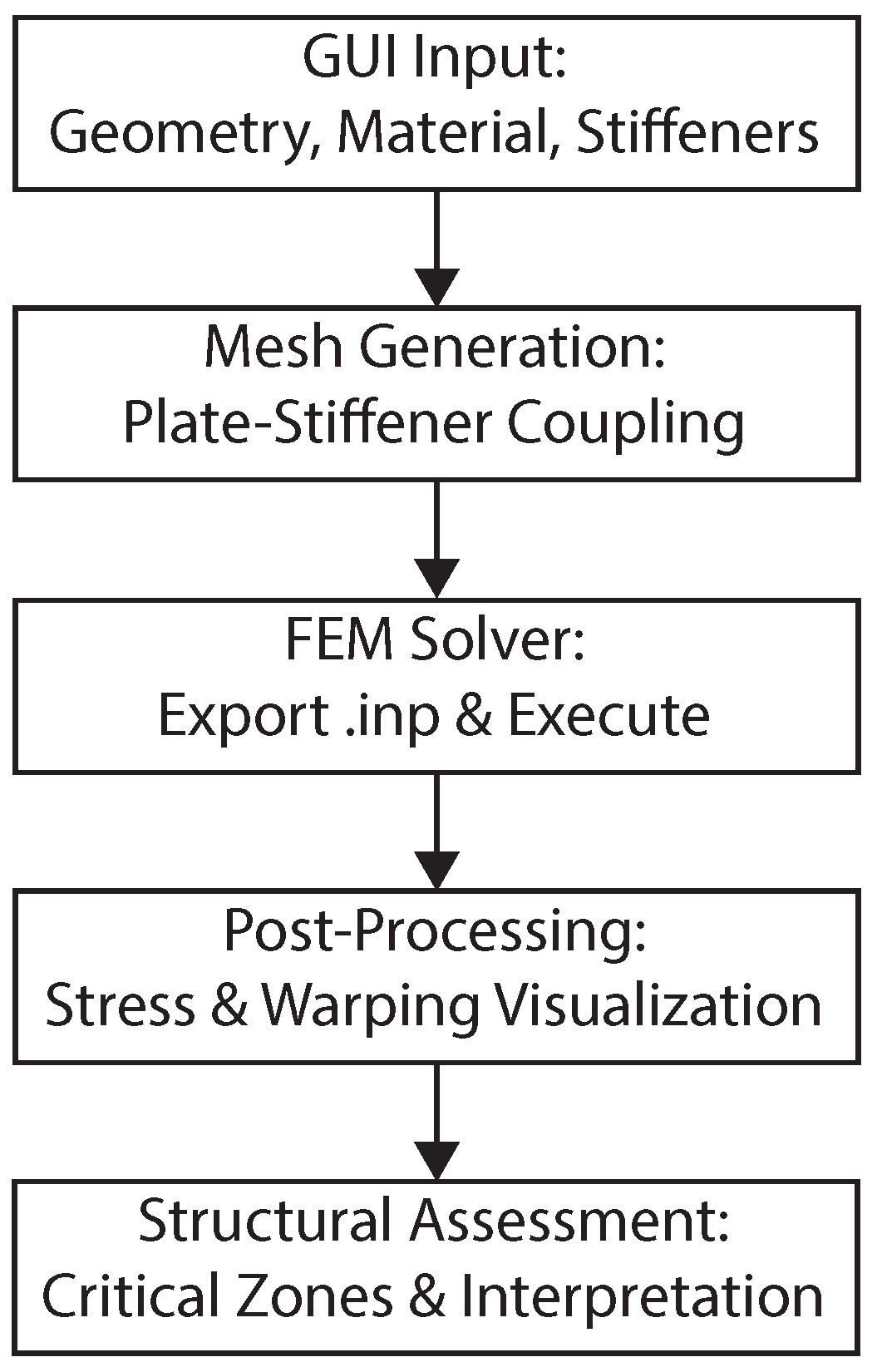

2.4. GUI-Based Numerical Implementation

| Parameter | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Plate length () | Dimension in x-direction | mm |

| Plate width () | Dimension in y-direction | mm |

| Plate thickness () | Plate thickness | mm |

| Stiffener spacing (s) | Distance between stiffeners | mm |

| Stiffener height () | Web or flange height | mm |

| Material modulus (E) | Young’s modulus | MPa |

| Poisson’s ratio () | Elasticity parameter | – |

| Applied torque (T) | Torsional loading | N·mm |

| Twist angle () | Imposed boundary rotation | rad |

| Mesh density () | Number of finite elements | – |

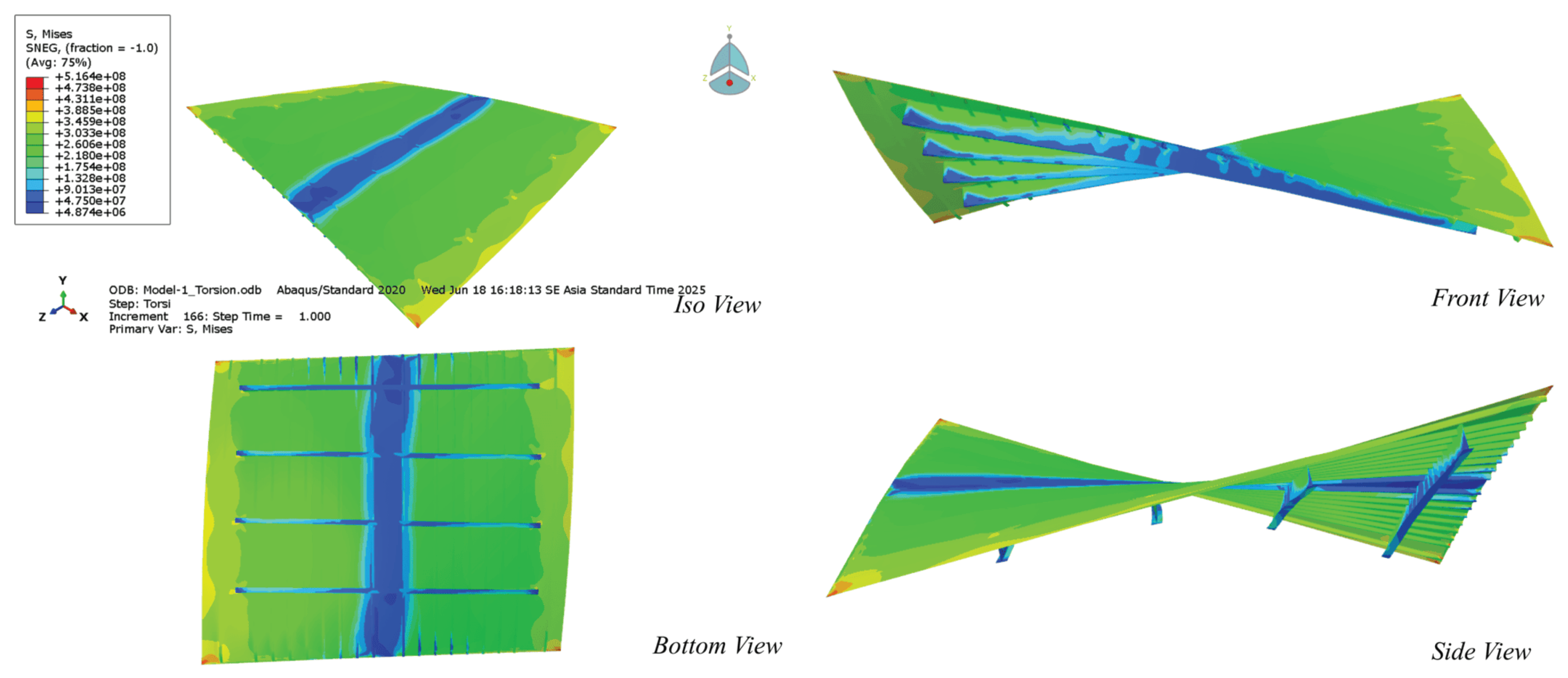

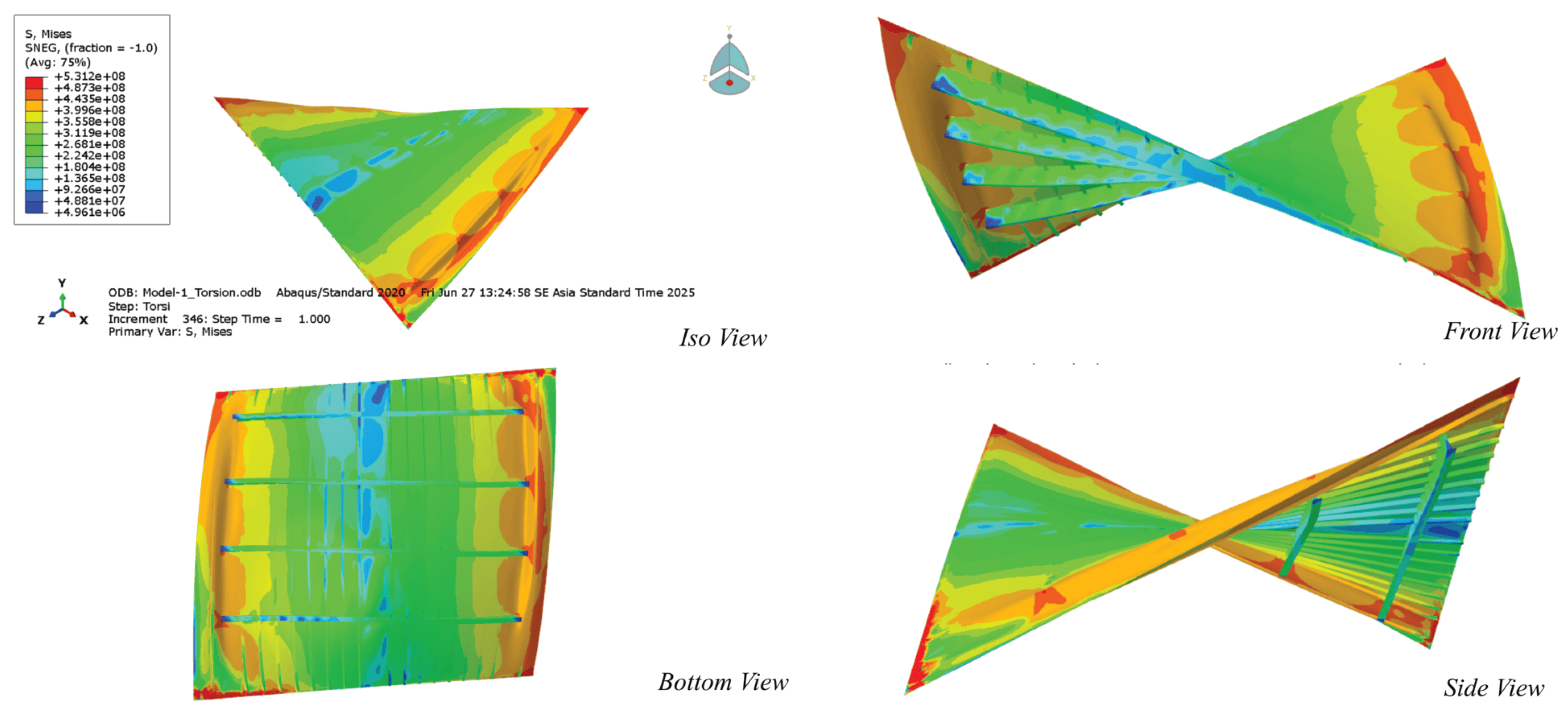

2.5. Post-Processing and Stress Evaluation

- contour plots of principal and von Mises stresses,

- distribution of maximum shear stress and warping deformation,

- critical stress paths along stiffener–plate connections.

3. Materials and Methods

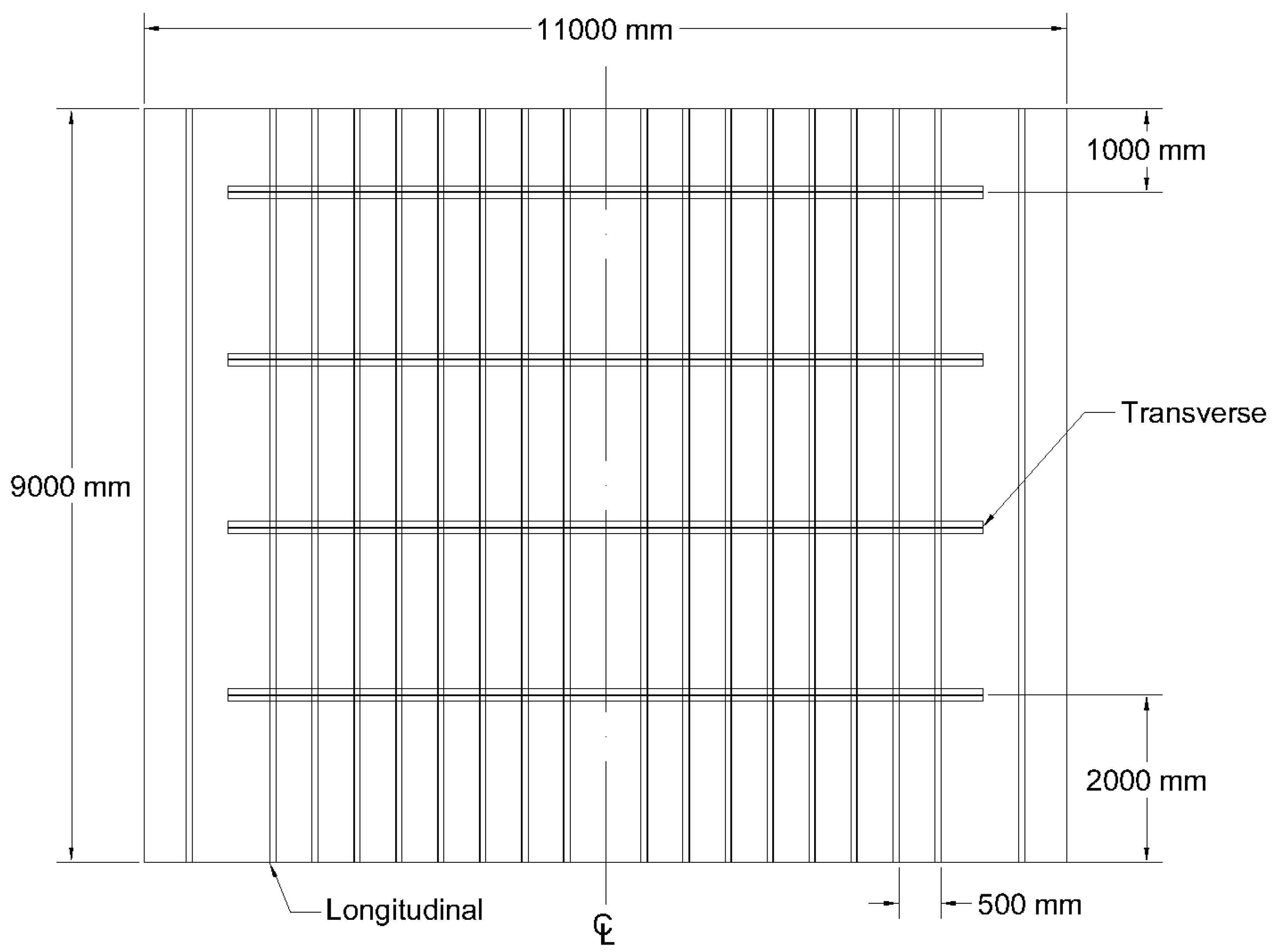

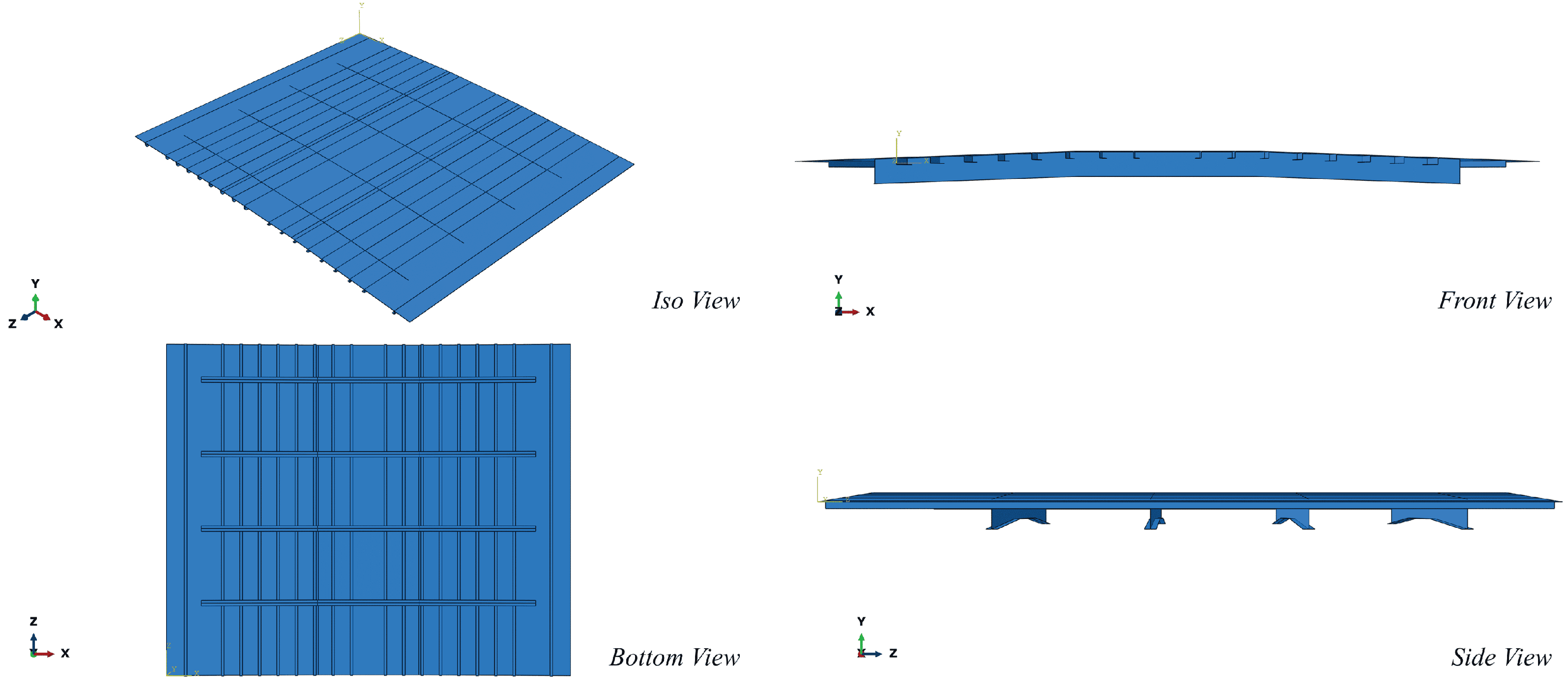

3.1. Stiffened Panel Configuration

3.2. Scripting and GUI-Based Automation Framework

3.3. Loading Application

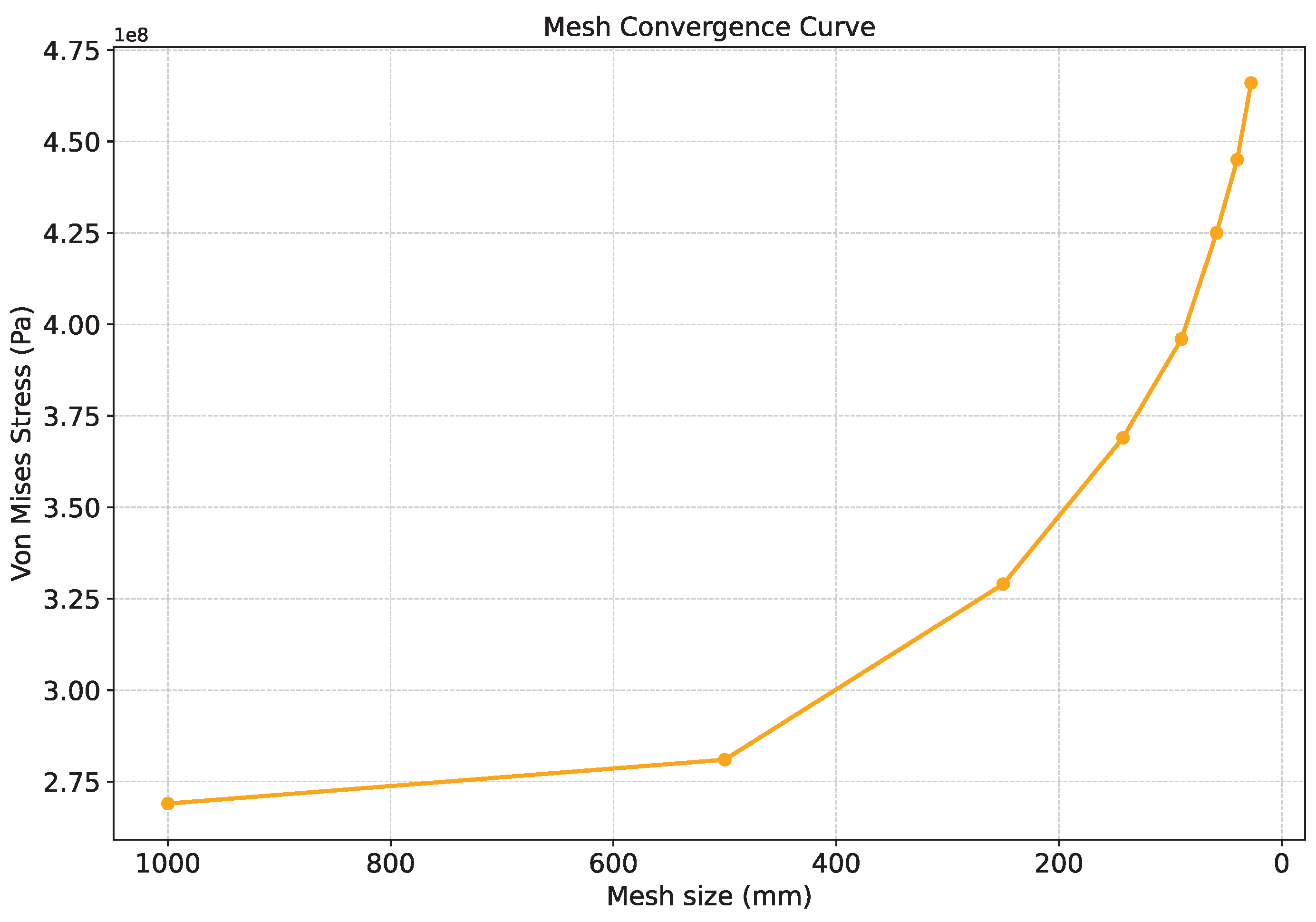

3.4. Mesh Convergence Studies

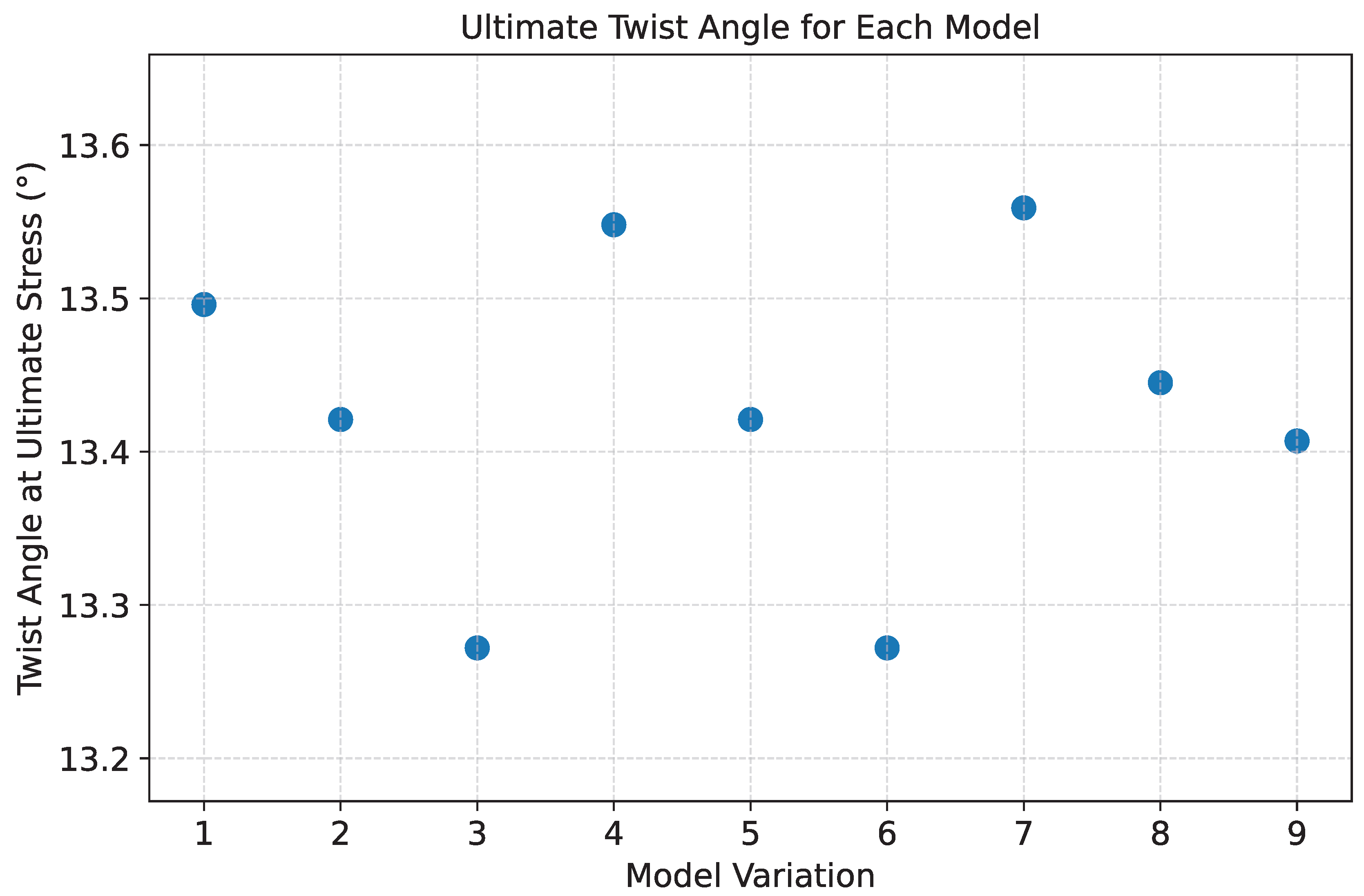

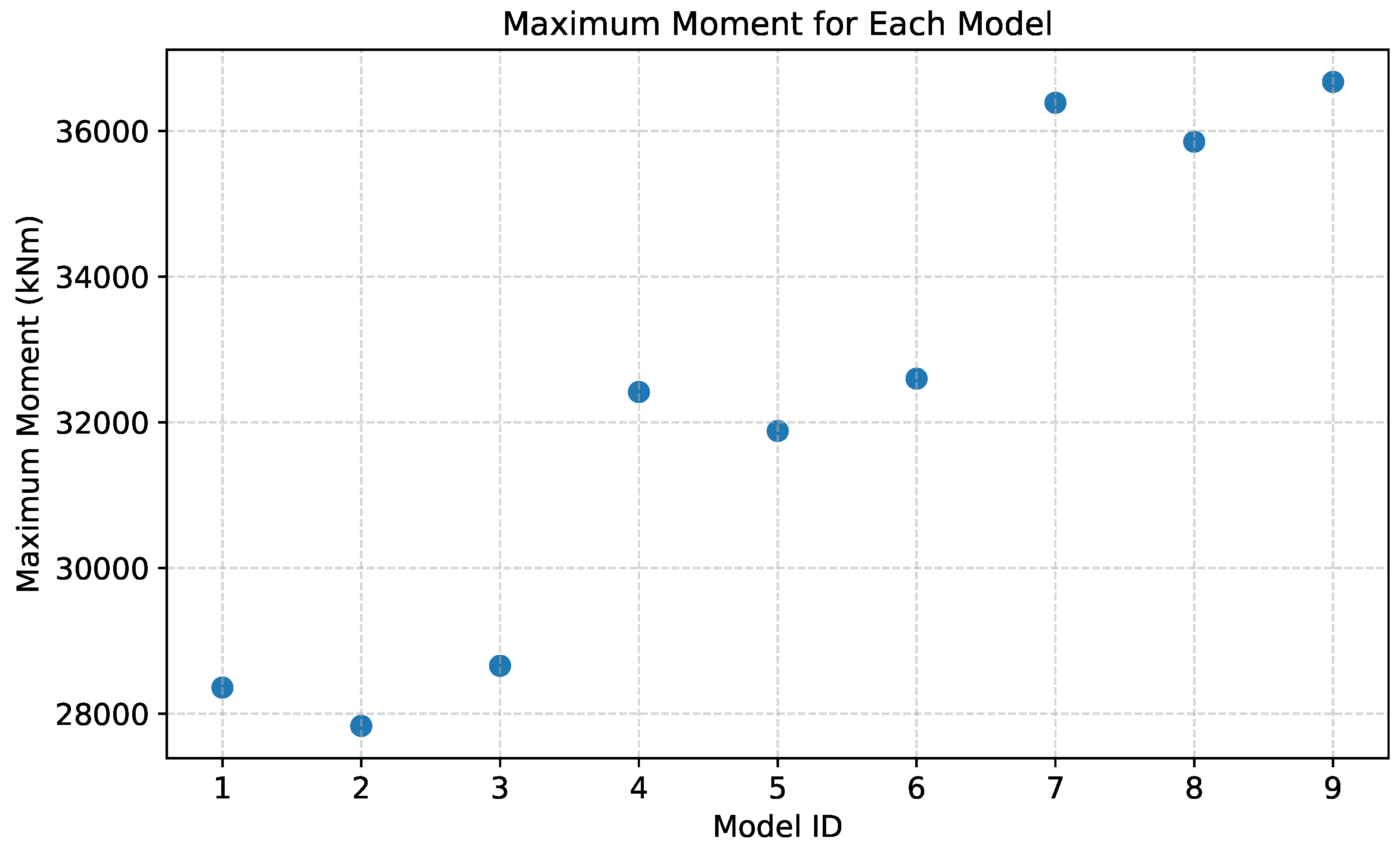

3.5. Structural Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

4. Results

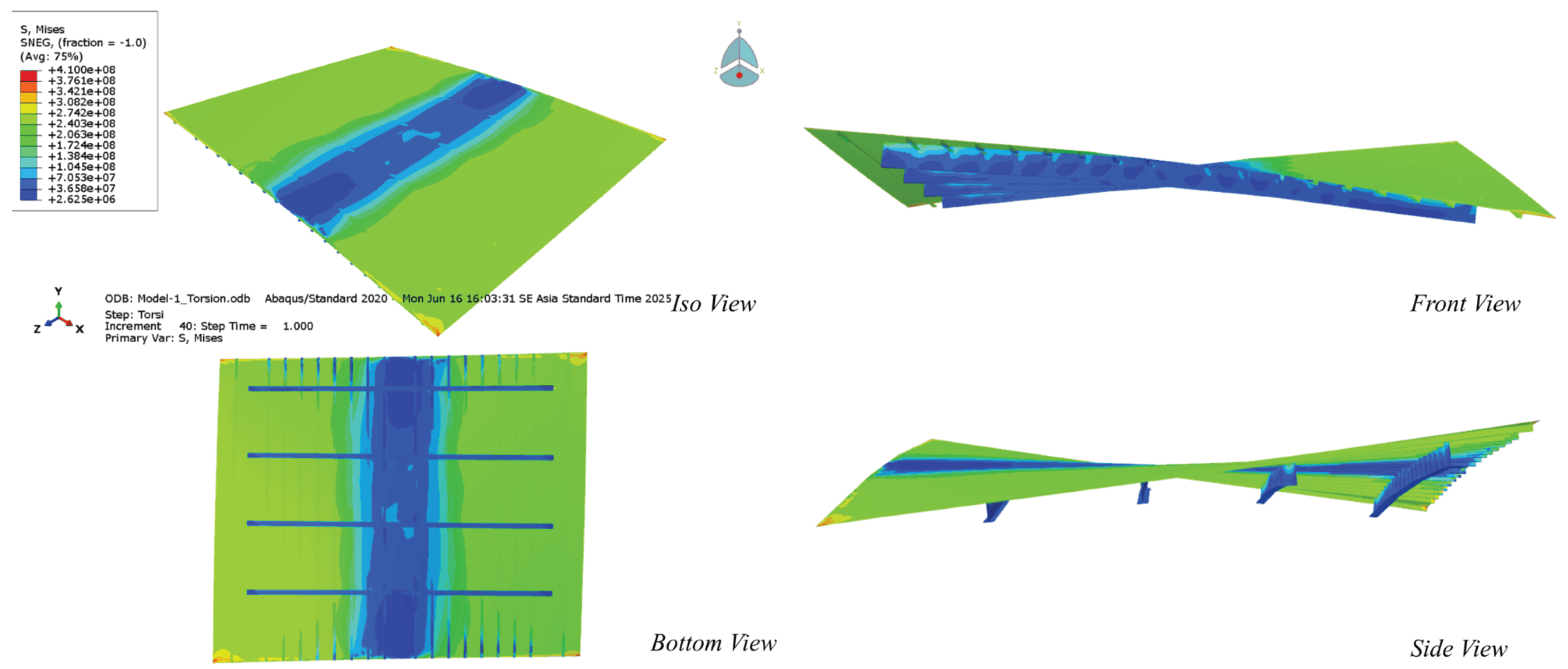

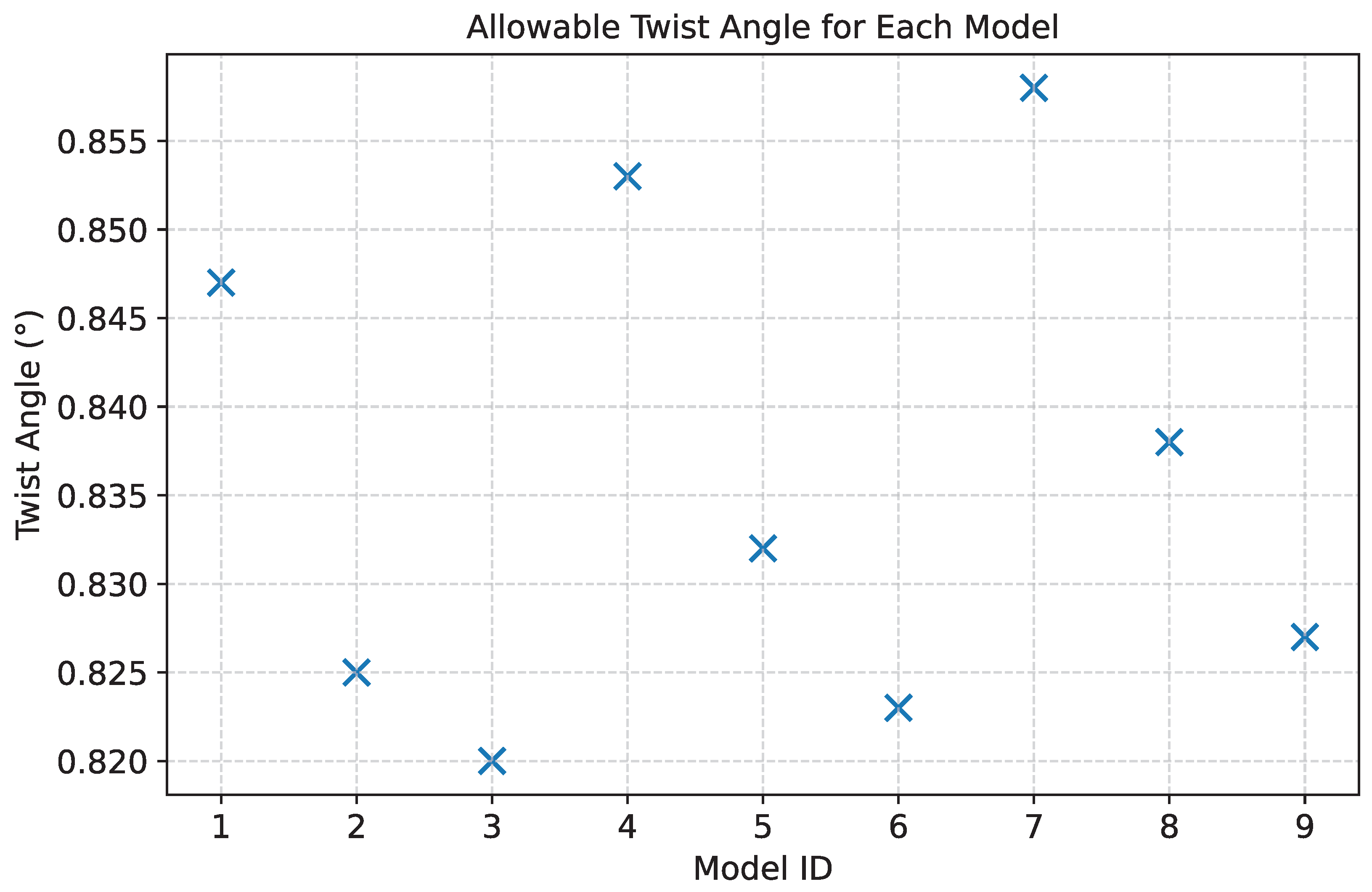

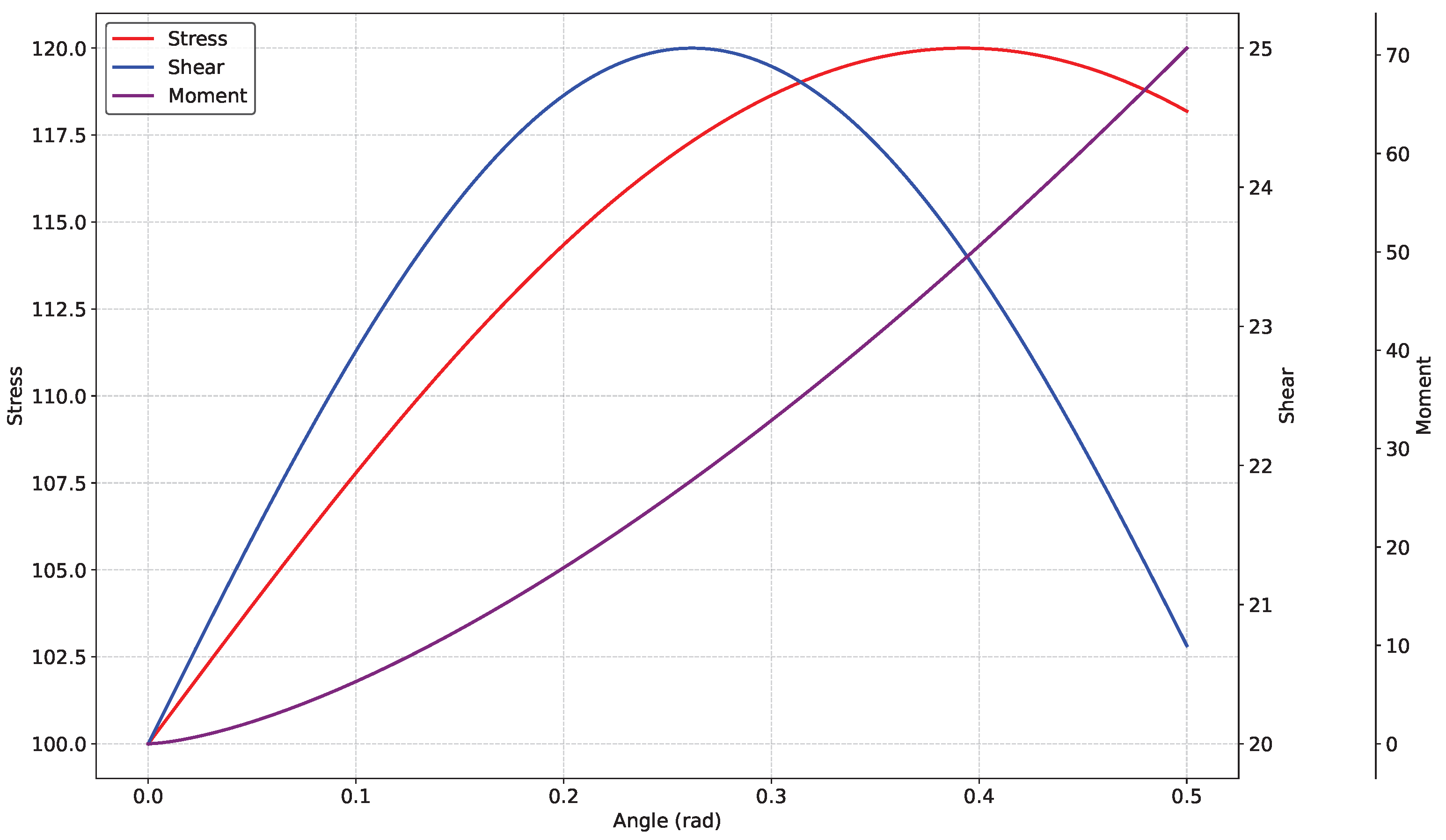

4.1. Stress Limit Assessment

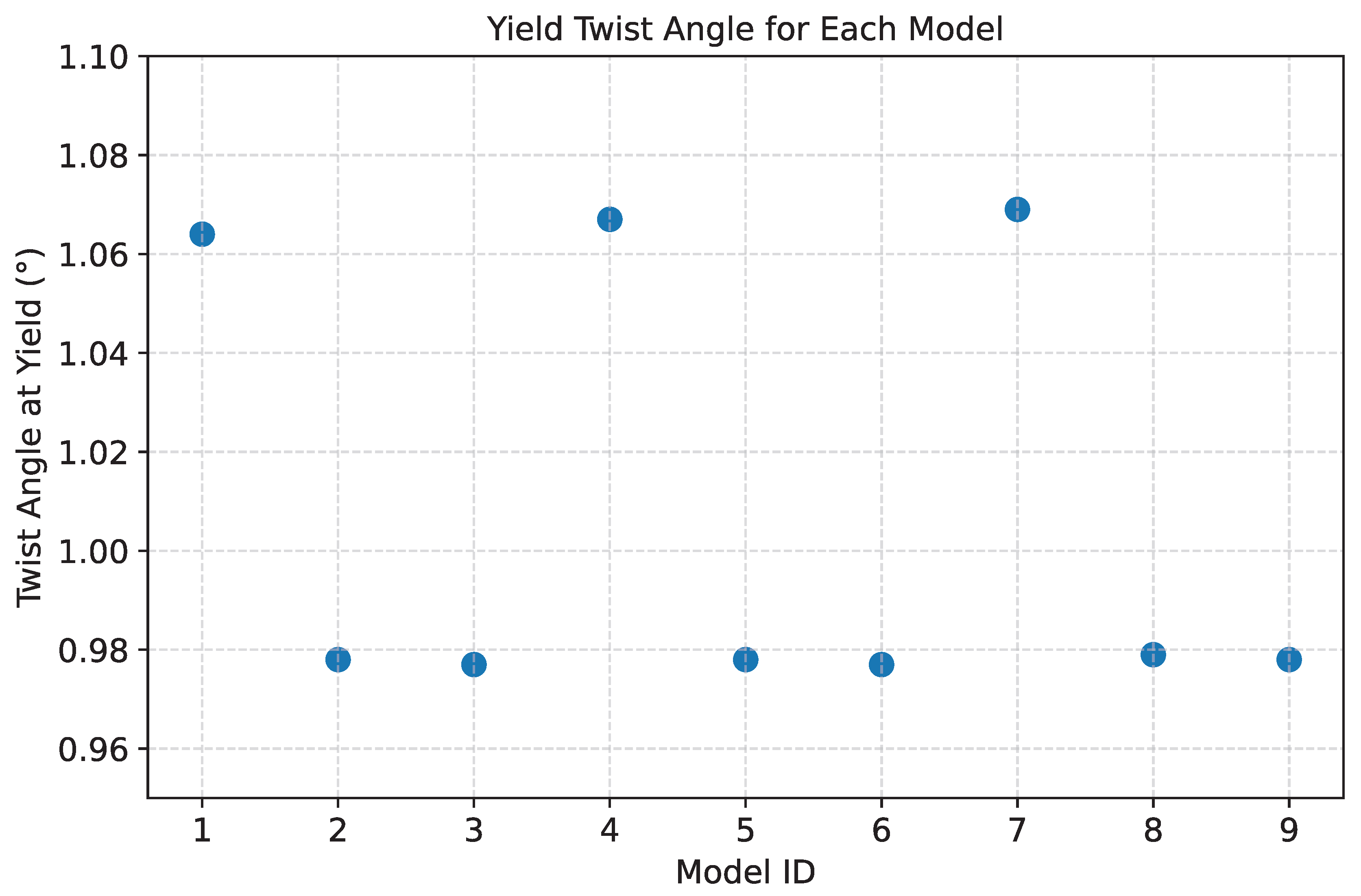

4.2. Torsional Yield Capacity Evaluation

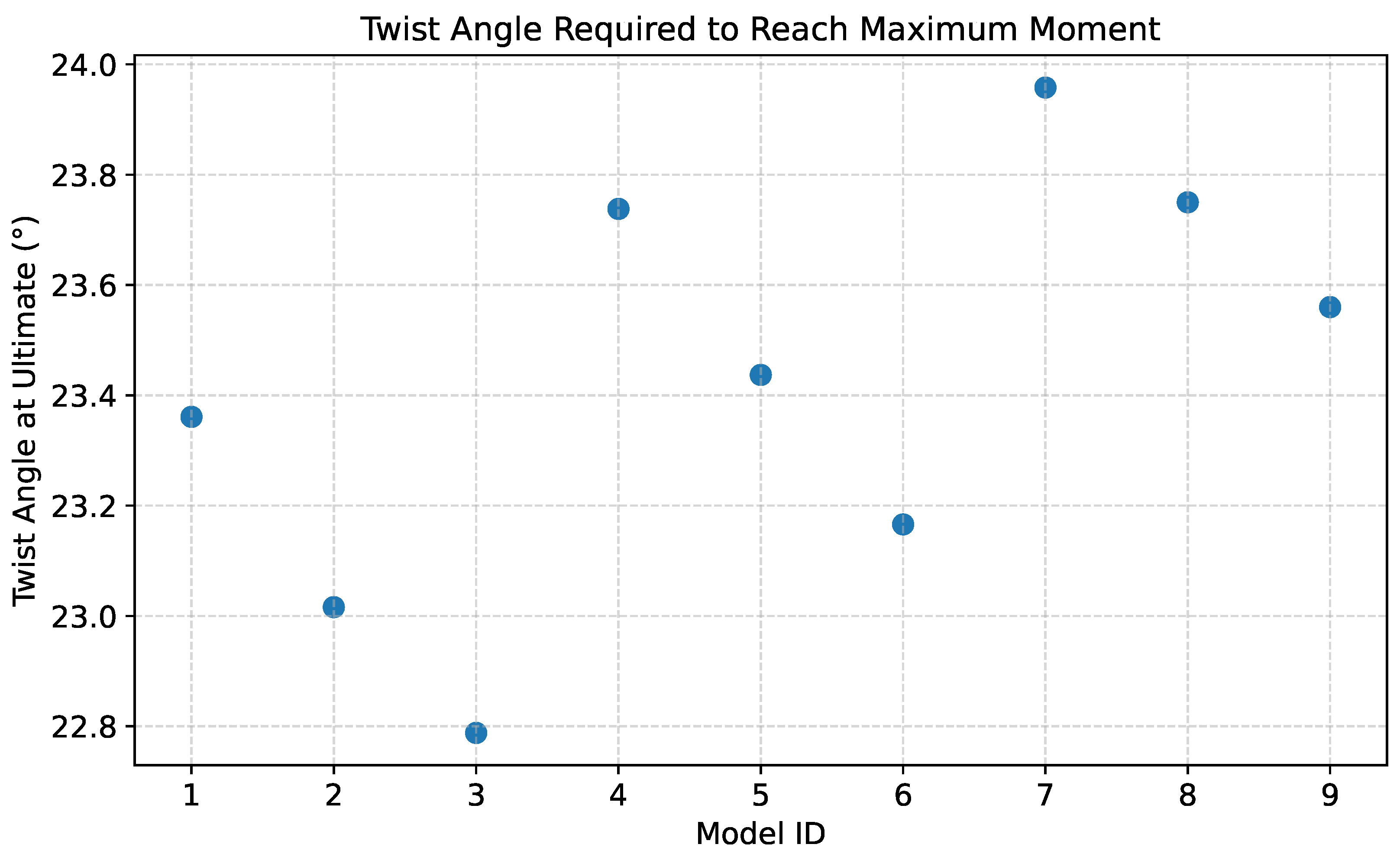

4.3. Ultimate Torsional Capacity Assessment

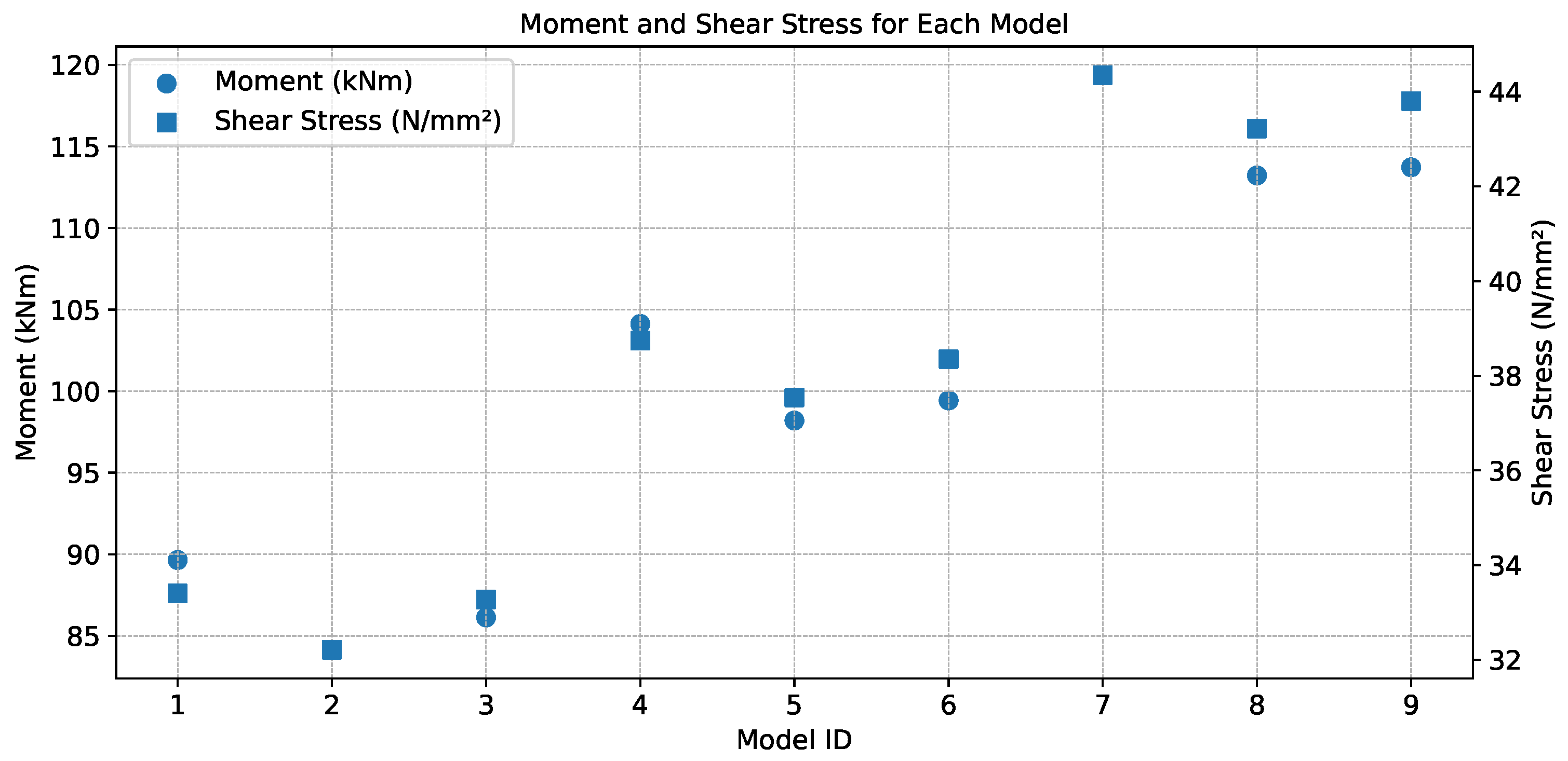

4.4. Evaluation of Torsional Moment Capacity

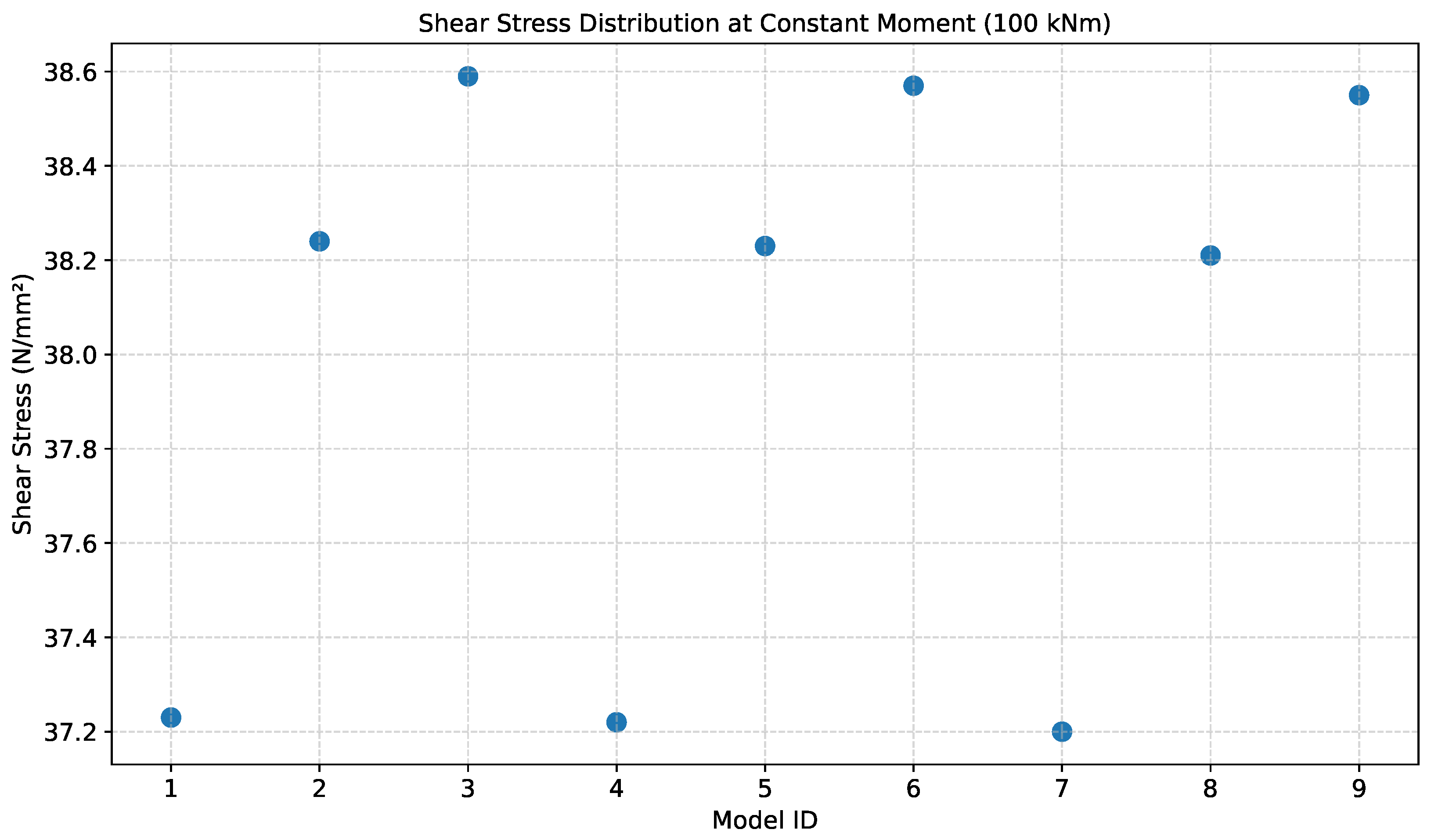

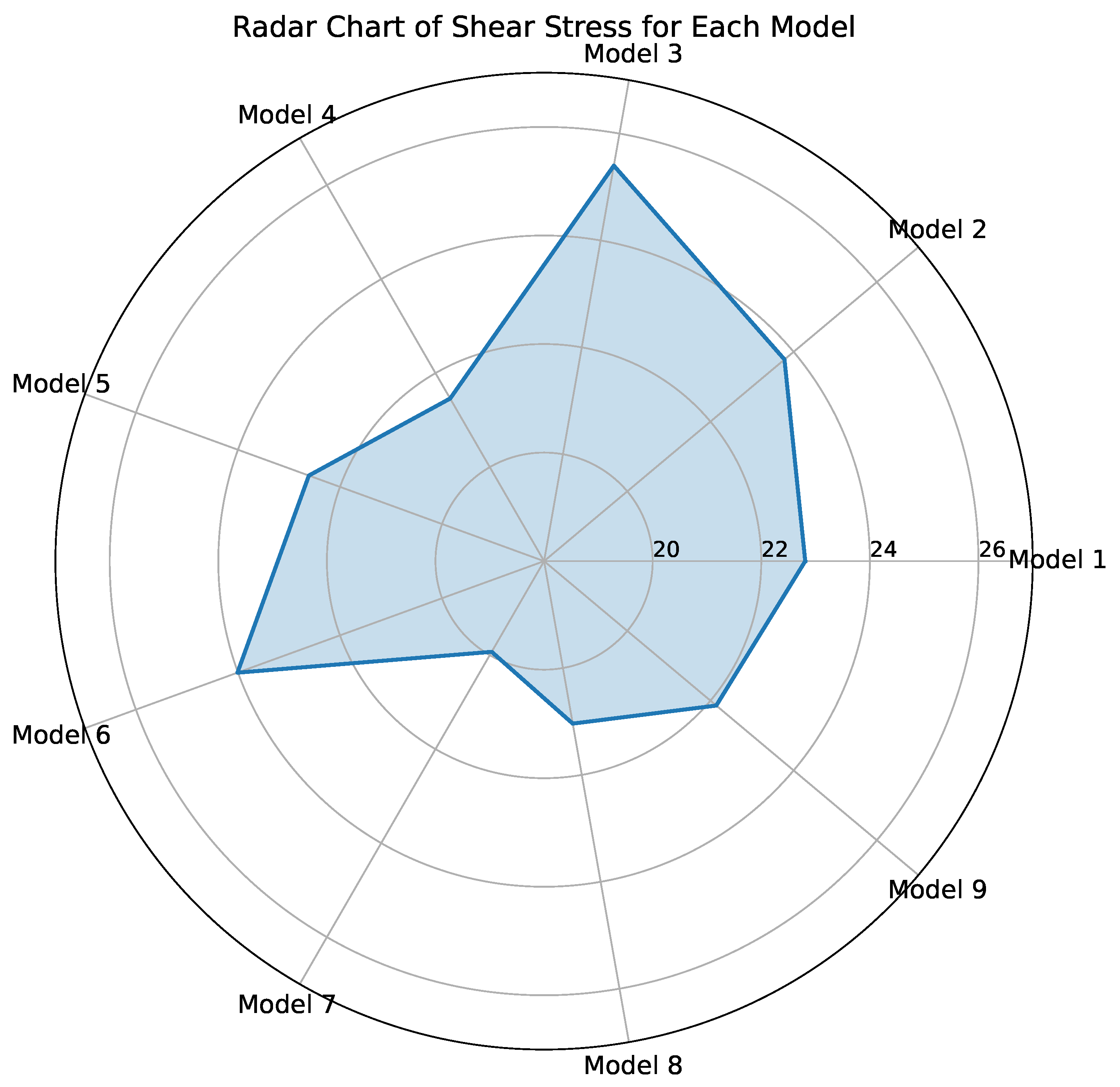

4.5. Shear Stress Analysis

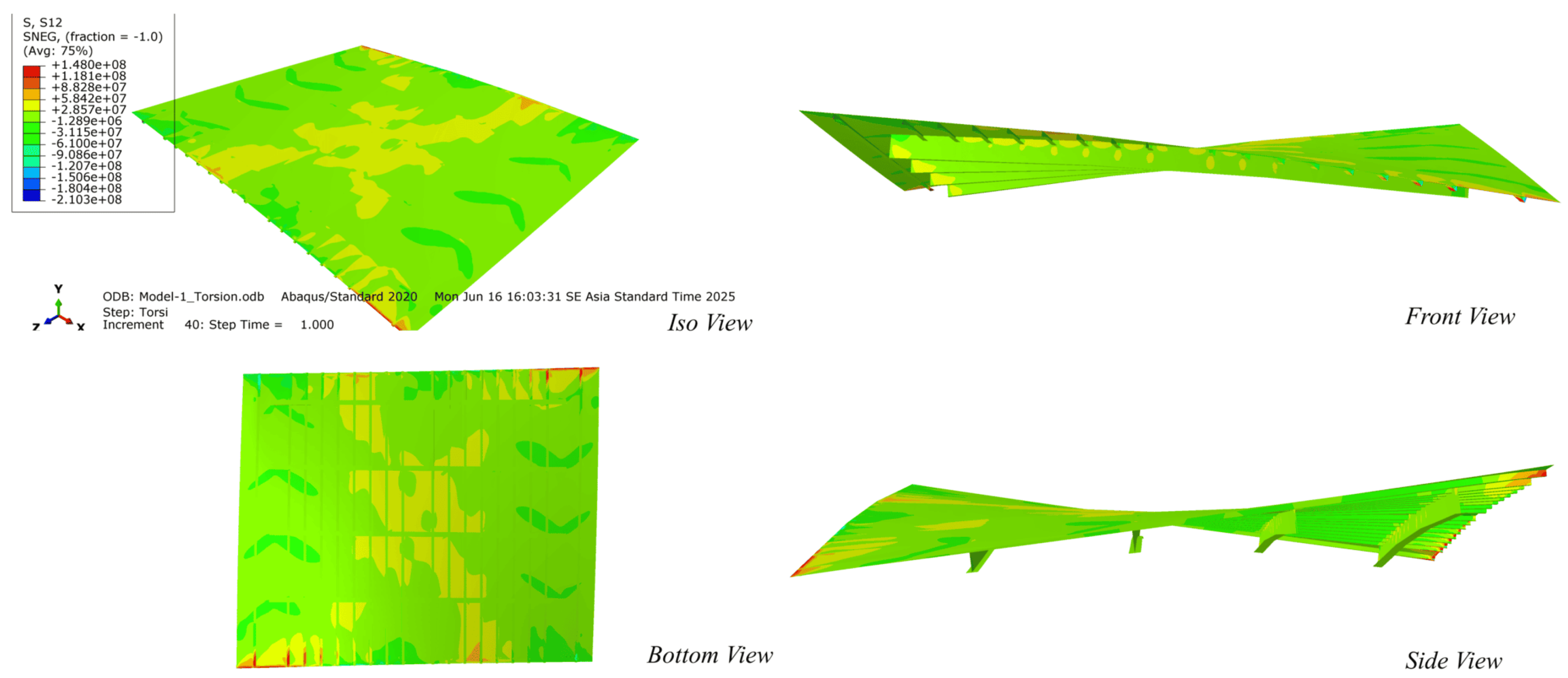

4.6. Structural Response Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, W.; Liang, Y.; Huang, Y. A Study on the Ultimate Strength and Failure Mode of Stiffened Panels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Qin, D. A Study on the Ultimate Strength and Failure Mode of Stiffened Panels. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 17, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Remes, H.; Romanoff, J. On the modelling of distorted thin-walled stiffened panels via a scale reduction approach for a simplified structural stress analysis. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 197, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Song, X.; Liao, C.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Yan, S.; Li, X. In-plane compressive responses and failure behaviors of composite sandwich plates with resin reinforced foam core. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, L.A.; Harding, J.E. Torsional buckling of outstands in longitudinally stiffened panels. Thin-Walled Struct. 1996, 24, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Moan, T. Ultimate strength of stiffened aluminium panels with predominantly torsional failure modes. Thin-Walled Struct. 2001, 39, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, R.; Wang, S. Optimal Design of Stiffened Panels Considering Torsion of Supporting Stiffeners. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 616, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zeng, Y.; Bai, X.; Lyu, F. Research on torsion deformation of integral stiffened panel by pre-stress shot peen forming. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 50, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D. Ultimate strength envelope of a 10,000TEU large container ship subjected to combined loads: From compartment model to global hull girder. Ocean Eng. 2020, 213, 107767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu, C.; Bekdaş, G.; Kim, S.; Geem, Z.W. Optimisation of Shear and Lateral–Torsional Buckling of Steel Plate Girders Using Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-R.; Muttaqie, T.; Do, Q.T.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.M.; Han, D.-H. Experimental investigations on the failure modes of ring-stiffened cylinders under external hydrostatic pressure. Appl. Sci. 2018, 10, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, R.F.; Das, P.K. Torsional buckling behaviour of stiffened cylinders under combined loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2000, 38, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bisagni, C. Buckling-driven mechanisms for twisting control in adaptive composite wings. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Shao, Y.-B.; Hassanein, M.F. Experimental shear testing of corrugated web girders with compression tubular flanges used in conventional buildings. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 179, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Hong, K.; Li, D.; Shi, H.; Hassanein, M.F. Ultimate torsional strength assessment of large deck opening stiffened box girder subjected to pitting corrosion. Ocean Eng. 2022, 251, 111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woloszyk, K.; Garbatov, Y.; Kowalski, J. Experimental ultimate strength assessment of stiffened plates subjected to marine immersed corrosion. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 138, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanadedy, H.; Sezen, H.; Abbas, H.; Almusallam, T.; Al-Salloum, Y. Progressive collapse risk of steel framed building considering column buckling. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 35, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.K.; Thayamballi, A.K.; Pedersen, P.T.; Park, Y.I. Ultimate strength of ship hulls under torsion. Ocean Eng. 2001, 28, 1097–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papangelis, J. On the Stresses in Thin-Walled Channels Under Torsion. Buildings 2024, 14, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikan, M.; Krasheninnikov, M.; Eremeyev, V.A. Torsional stability capacity of a nano-composite shell based on a nonlocal strain gradient shell model under a three-dimensional magnetic field. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 148, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, D. Experimental and numerical investigations of the ultimate torsional strength of an ultra large container ship. Mar. Struct. 2020, 70, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, D. Design similar scale model of a 10,000 TEU container ship through combined ultimate longitudinal bending and torsion analysis. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 88, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovini, A.; Li, C.X.; Paz Mendez, J.; Jin, B.C.; Manes, A.; Bisagni, C. Post-buckling behavior and collapse of Double-Double composite single stringer specimens. Compos. Struct. 2024, 327, 117699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, V.; Suthenthiraveerappa, V.; David, J.S.; Subramanian, J.; Annamalai, A.R.; Jen, C.-P. Experimental and Numerical Analyses on the Buckling Characteristics of Woven Flax/Epoxy Laminated Composite Plate under Axial Compression. Polymers 2021, 13, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Li, F.; Liu, B.; Zhao, N.; Deng, J. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of the Collapse Behaviour of a Cracked Box Girder Under Bidirectional Cyclic Bending Moments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongthanapanich, S.; Dechaumphai, P. EasyFEM—An object-oriented graphics interface finite element/finite volume software. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2006, 37, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Nahar, T.T.; Kim, D. FeView: Finite element model (FEM) visualization and post-processing tool for OpenSees. SoftwareX 2021, 15, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Lin, Y.-C. Web-FEM: An internet-based finite-element analysis framework with 3D graphics and parallel computing environment. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2008, 39, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, P.; Wang, B. CAD-integrated stiffener sizing-topology design via force flow members (FFM). Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 415, 116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryumin, S.; Tryaskin, V.; Plotnikov, K. Algorithms for the Recognition of the Hull Structures’ Elementary Plate Panels and the Determination of Their Parameters in a Ship CAD System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Functional Capabilities | |

| Geometry Input | Parametric generation of plate and stiffener configurations |

| Mesh Generator | Automated meshing and element type selection |

| Local System Assignment | Definition of coordinate systems for stiffener orientation |

| Load Application | Specification of torsional loading and boundary conditions |

| Post-Processing | Stress, displacement, and warping visualization |

| 2. Numerical Workflow | |

| User-defined Input | Geometry, stiffener layout, material properties, mesh density, loading parameters |

| Model Generation | FEM model creation with automatic element assignment and plate–stiffener coupling |

| Mesh & Solver Export | Structured input file generation for FEM execution |

| FEM Solution | Computation of displacement fields and torsional stress responses |

| Post-Processing | Identification of critical stress regions and warping deformation assessment |

| Part Name | Size (mm) |

|---|---|

| Deck Plate | |

| Deck Longitudinal | |

| Deck Transverse | |

| Deck Longitudinal Spacing | 500 |

| Deck Transverse Spacing | 2000 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Linear Elastic Properties | |

| Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | 210 |

| Poisson’s Ratio, | 0.30 |

| Density, (kg/m3) | 7850 |

| Nonlinear / Plasticity Parameters | |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | 355 |

| Ultimate Strength (MPa) | 490–620 |

| Plastic Strain at Yield | 0.002–0.003 |

| Tangent Modulus, (GPa) | 1.5 |

| Hardening Rule | Isotropic |

| Material Model (FEM) | Elastic–plastic von Mises |

| Point | Strain (–) | Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.0017 | 355 |

| 3 | 0.0060 | 365 |

| 4 | 0.0150 | 390 |

| 5 | 0.0300 | 420 |

| 6 | 0.0500 | 450 |

| 7 | 0.0800 | 480 |

| 8 | 0.1200 | 510 |

| Interval | (Pa) | (Pa) | Absolute diff. (Pa) | Percent diff. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 → 500 | ||||

| 500 → 250 | ||||

| 250 → 142.5 | ||||

| 142.5 → 90 | ||||

| 90 → 58.5 | ||||

| 58.5 → 40 | ||||

| 40 → 27.5 |

| Plate Thickness (mm) | Longitudinal Stiffener Size (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 mm | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| 8 mm | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| 9 mm | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).