Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

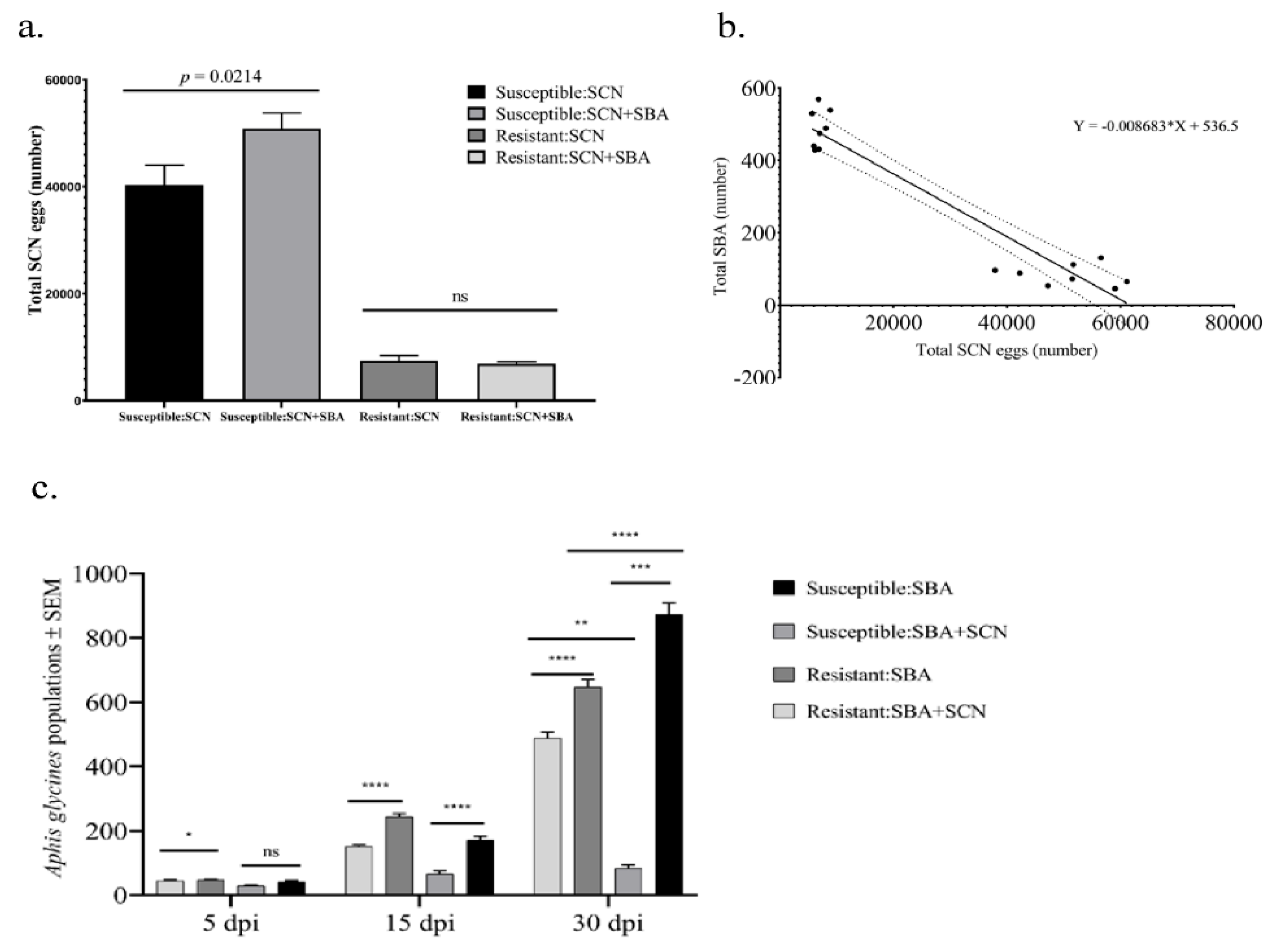

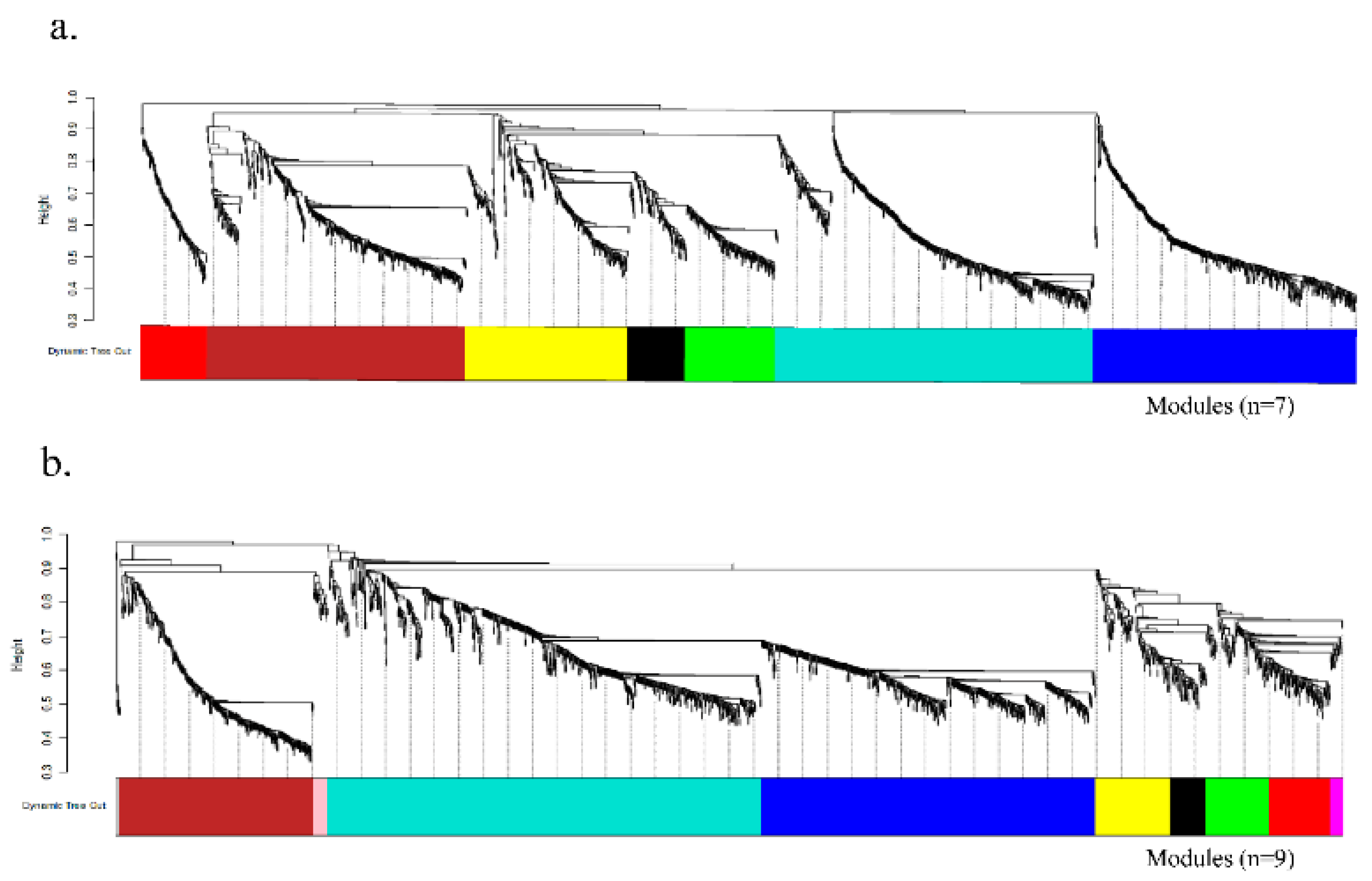

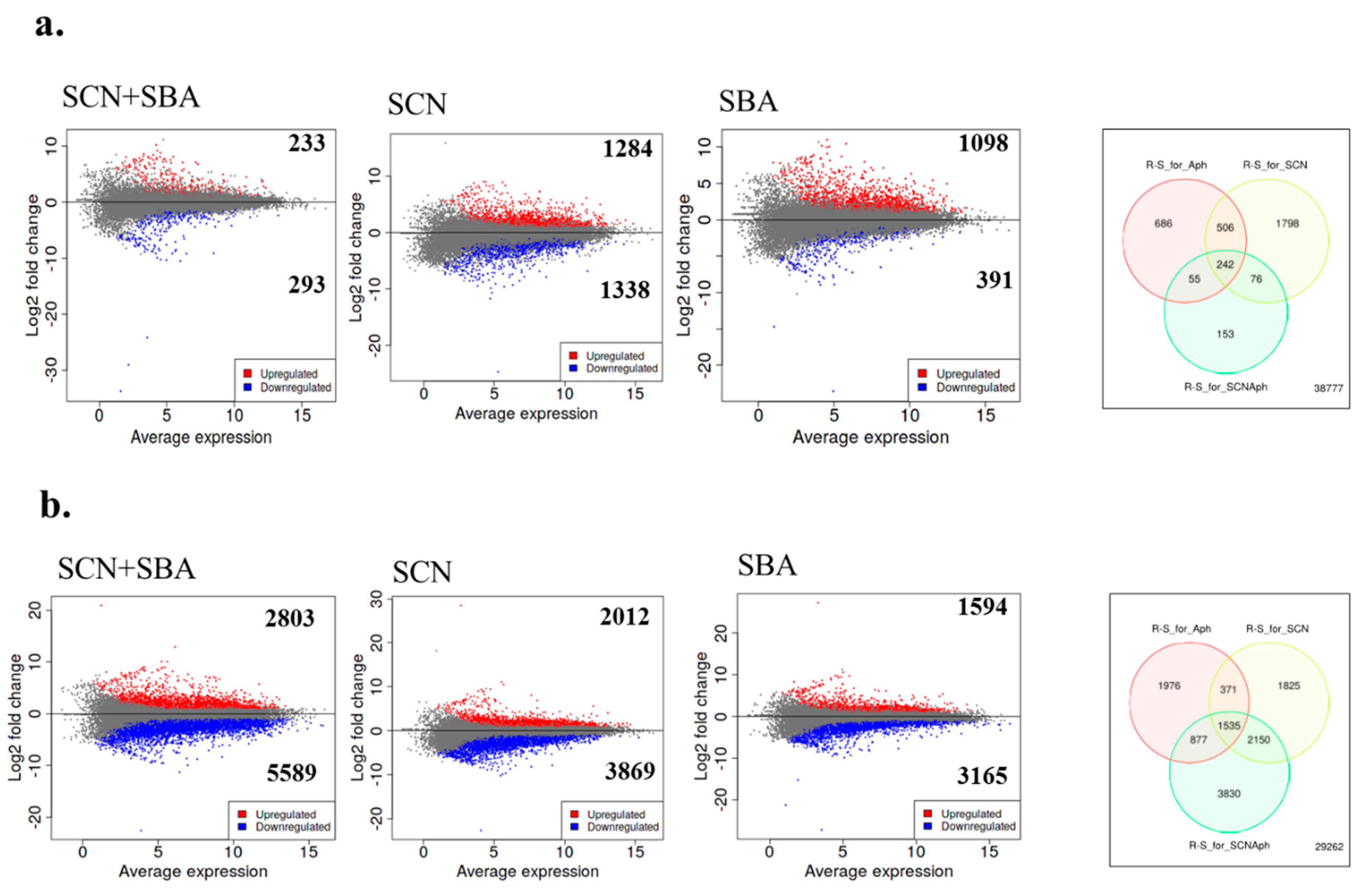

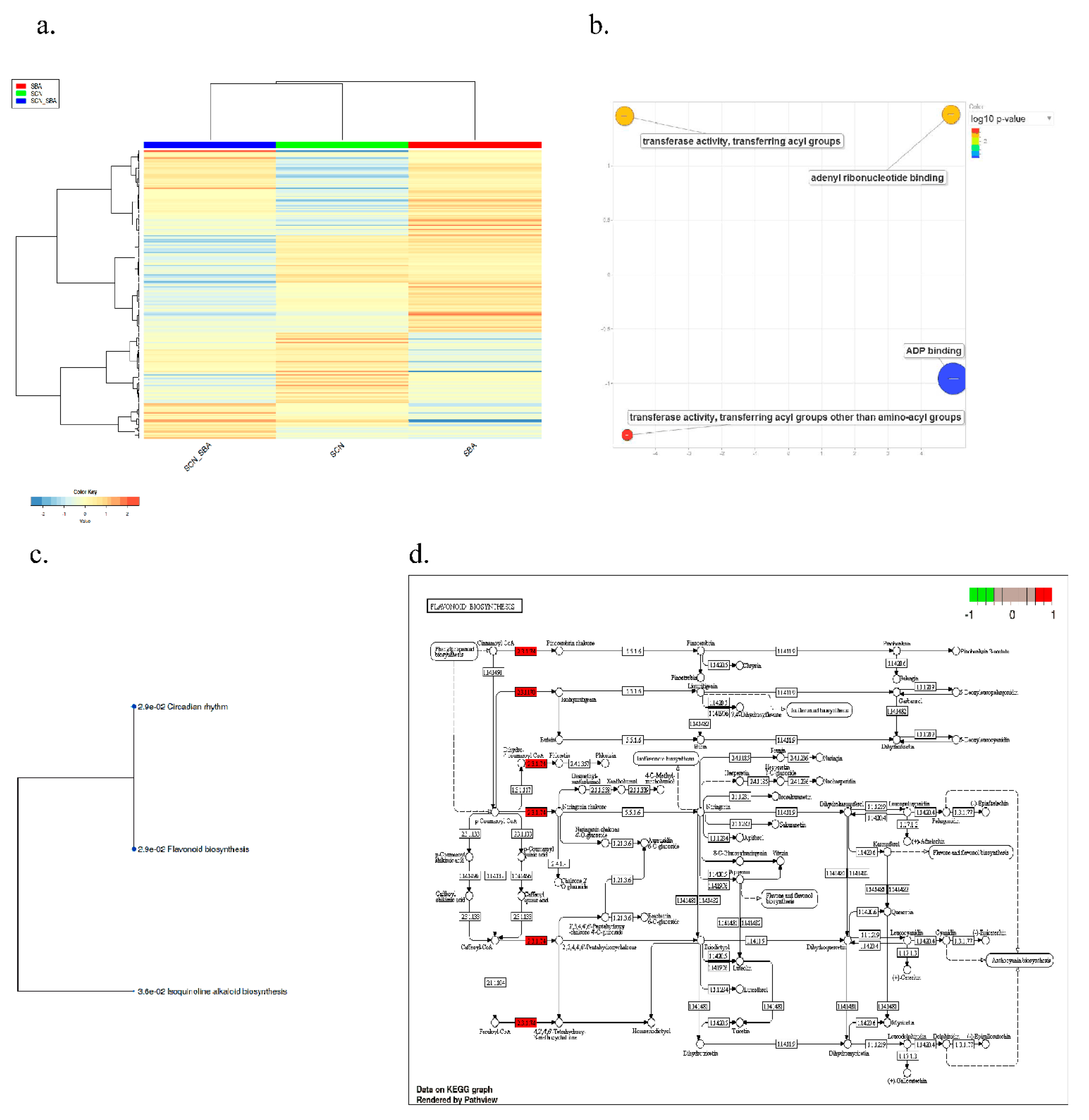

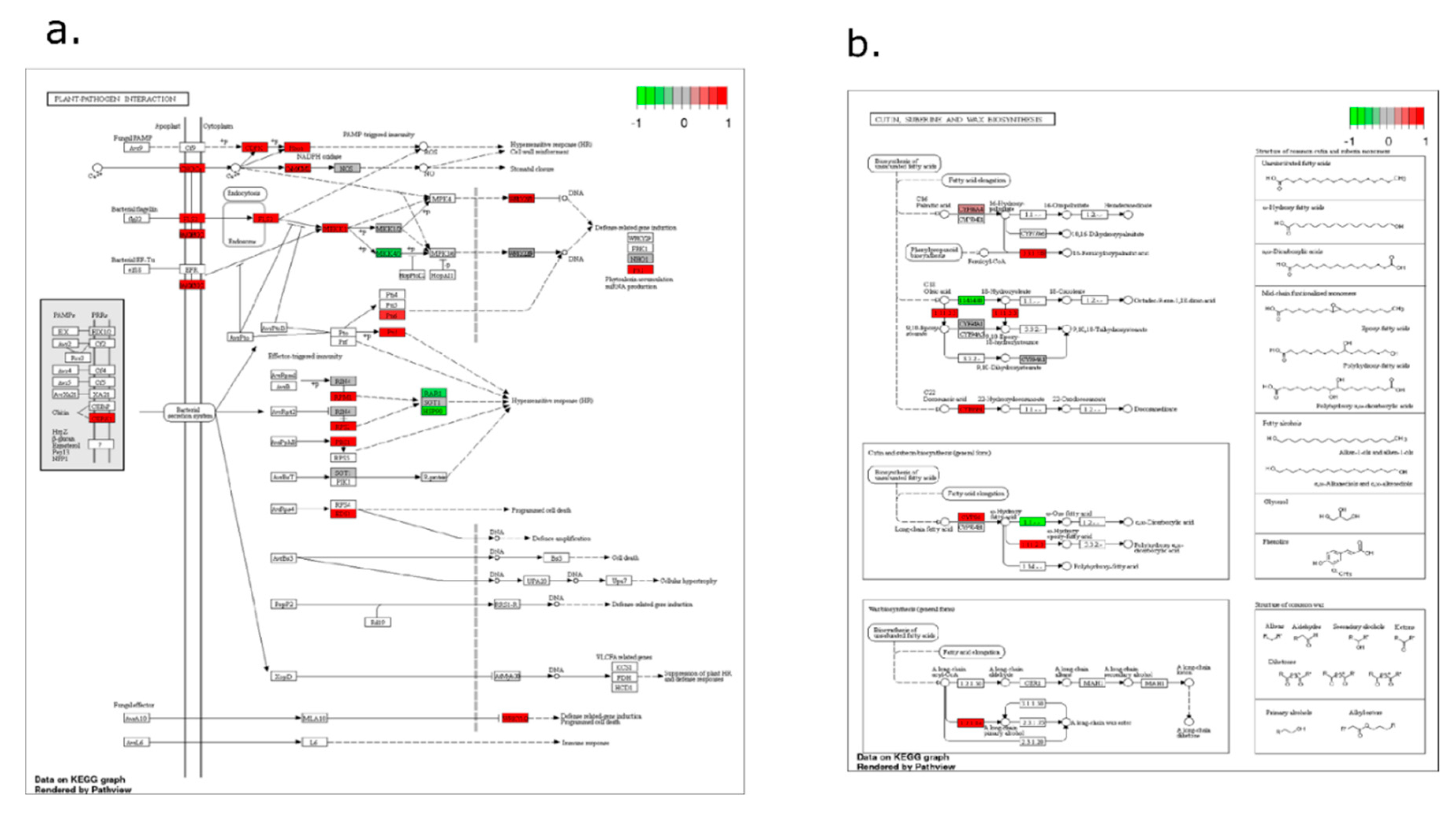

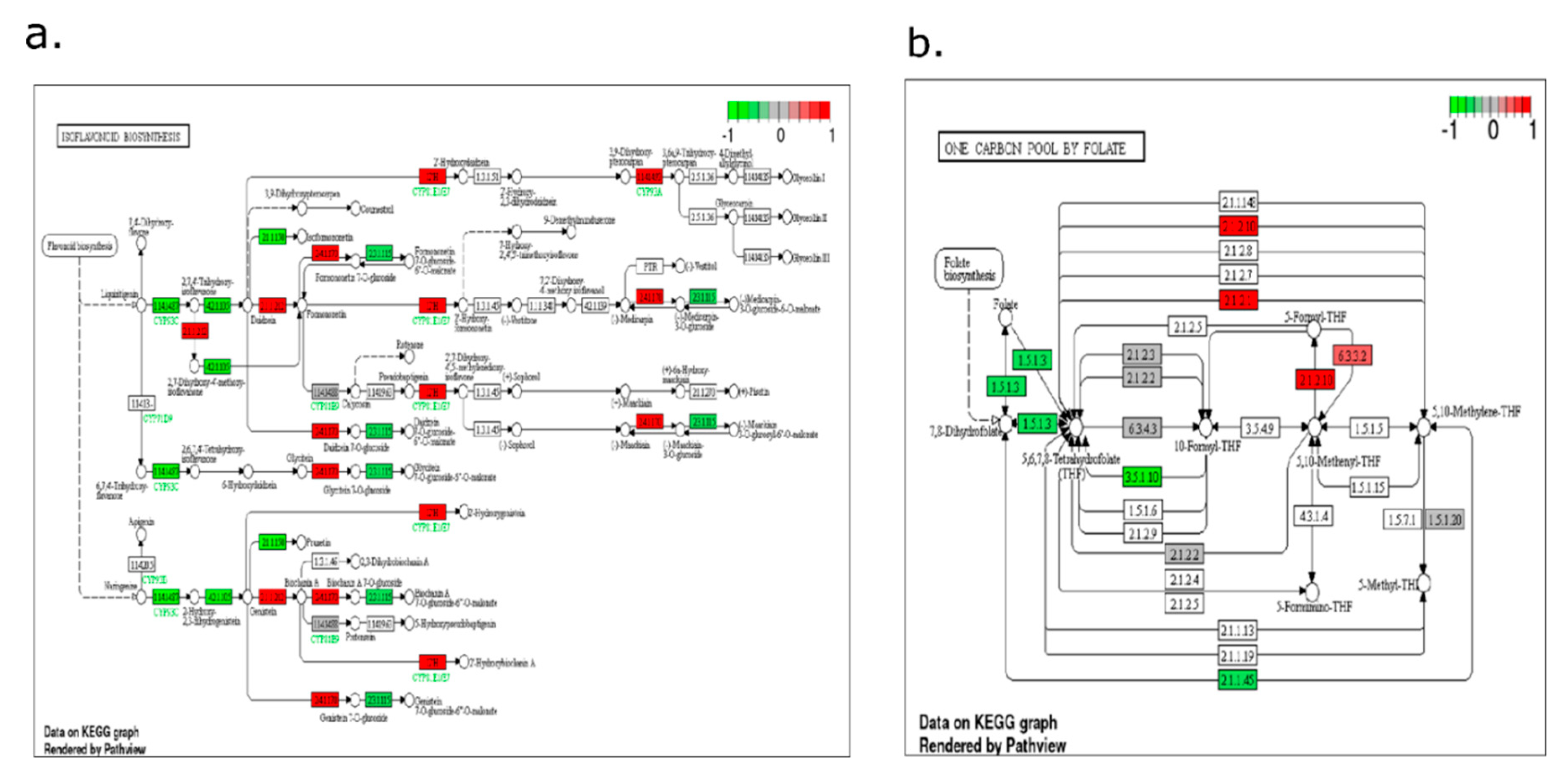

Soybean aphid (SBA), Aphis glycines Matsumura (Hemiptera: Aphididae), and soybean cyst nematode (SCN), Heterodera glycines Ichinoe (Tylenchida: Heteroderidae), are major pests of soybean, Glycine max L. Merr., in the U.S. Midwest. This study examined three-way interactions among soybean, SBA, and SCN using demographic and transcriptomic analyses. SCN-resistant and SCN-susceptible cultivars were evaluated under three treatments (SBA, SCN, SCN+SBA) in a randomized complete block design with six replicates, repeated eight times in greenhouse cone-tainers. Plants were infested with 2,000 SCN eggs at planting or 15 SBA at the V2 stage. Aphid populations were counted at 5-, 15-, and 30-days post-infestation (dpi), and SCN eggs sampled at 30 dpi. SCN egg density increased significantly in the susceptible cultivar but remained unchanged in the resistant cultivar in the presence of SBA, while SBA populations declined under SCN infestation. RNA-seq identified 4,637 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at 5 dpi and 19,032 DEGs at 30 dpi. Analyses focused on DEGs shared across treatments but discordantly expressed in resistant cultivars during SBA–SCN interactions. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis revealed seven and nine modules at 5 and 30 dpi, respectively. Enrichment analyses identified ‘Plant–Pathogen Interaction’ and ‘Cutin, Suberin, and Wax Biosynthesis’ at 5 dpi, and ‘Isoflavonoid Biosynthesis’ and ‘One-Carbon Pool by Folate’ at 30 dpi. Several DEGs overlapped with SCN resistance QTLs, identifying candidate genes for cross-resistance breeding.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Greenhouse Experiment Reveals Asymmetric Above–Belowground Interactions

2.2. RNA-seq Dataset Quality and Overall Structure of the Transcriptome Signal

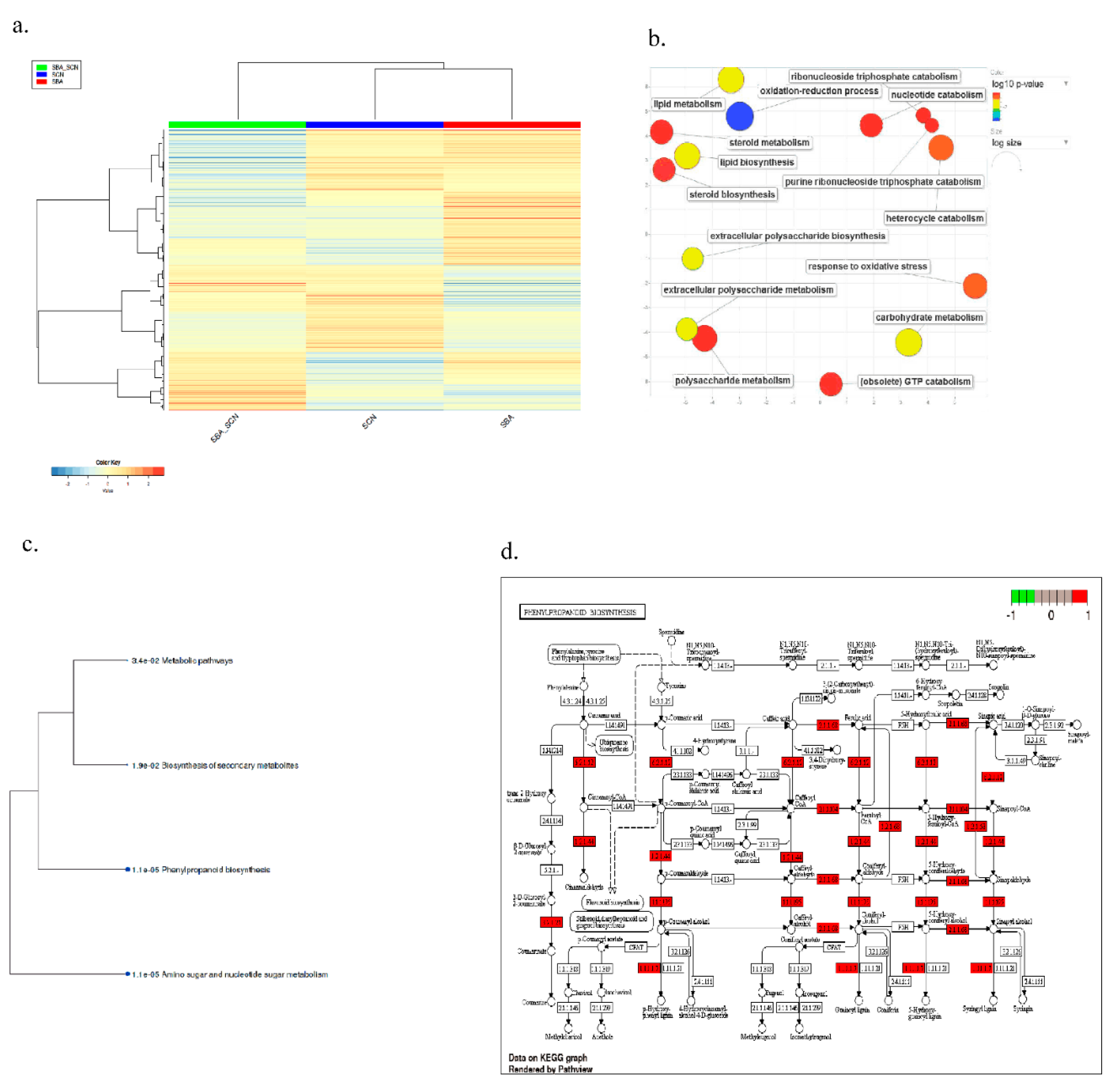

2.3. Co-Expression Network Analysis Highlights Late Oxidative-Stress Programs

2.4. Large, Time-Dependent Cultivar Contrasts Reveal Shared Core Responses to SCN, SBA, and Their Combination

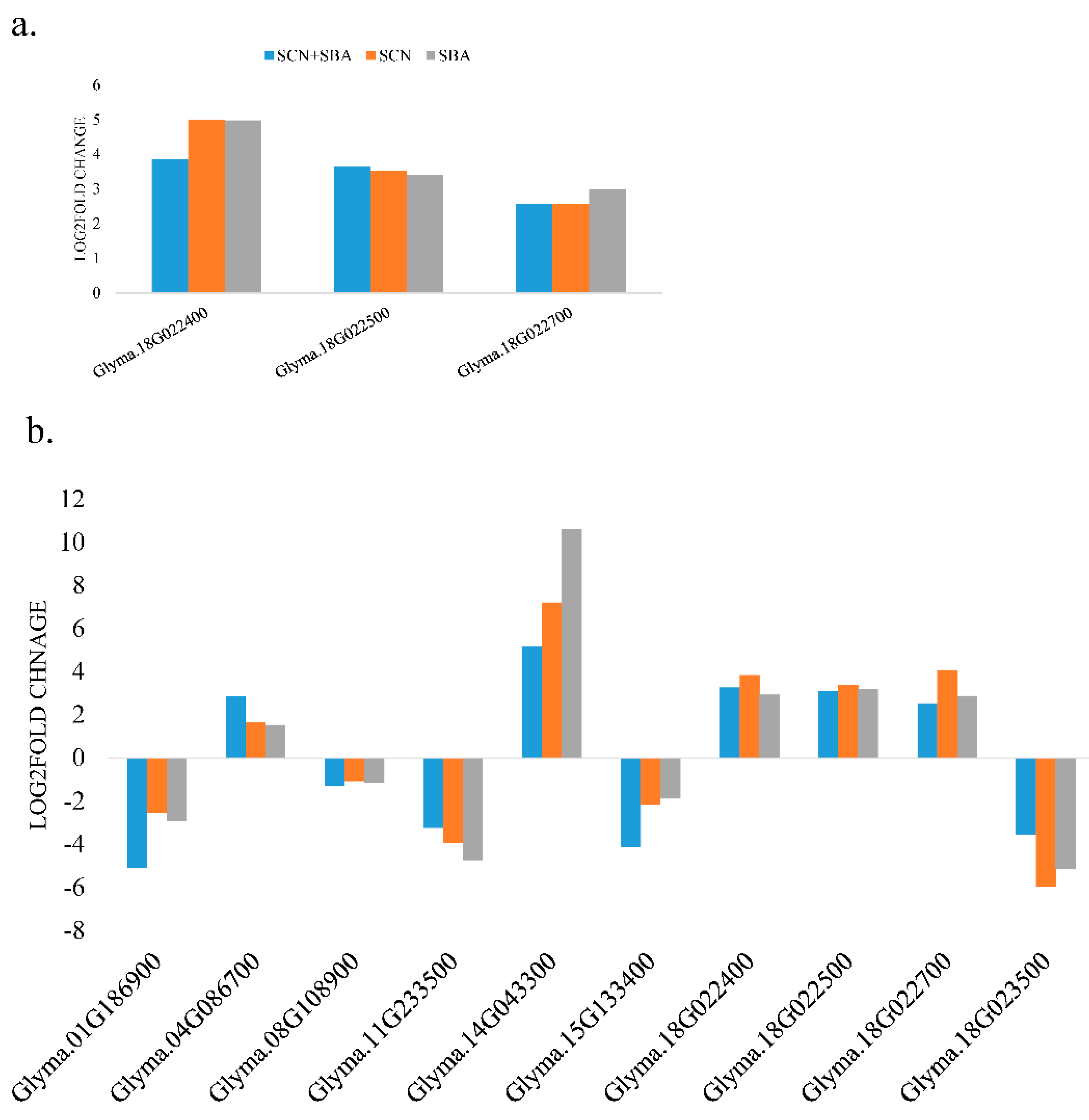

2.5. A Subset of DEGs Coincide with Known SCN Resistance QTL Regions (QTL-Coincident Signals)

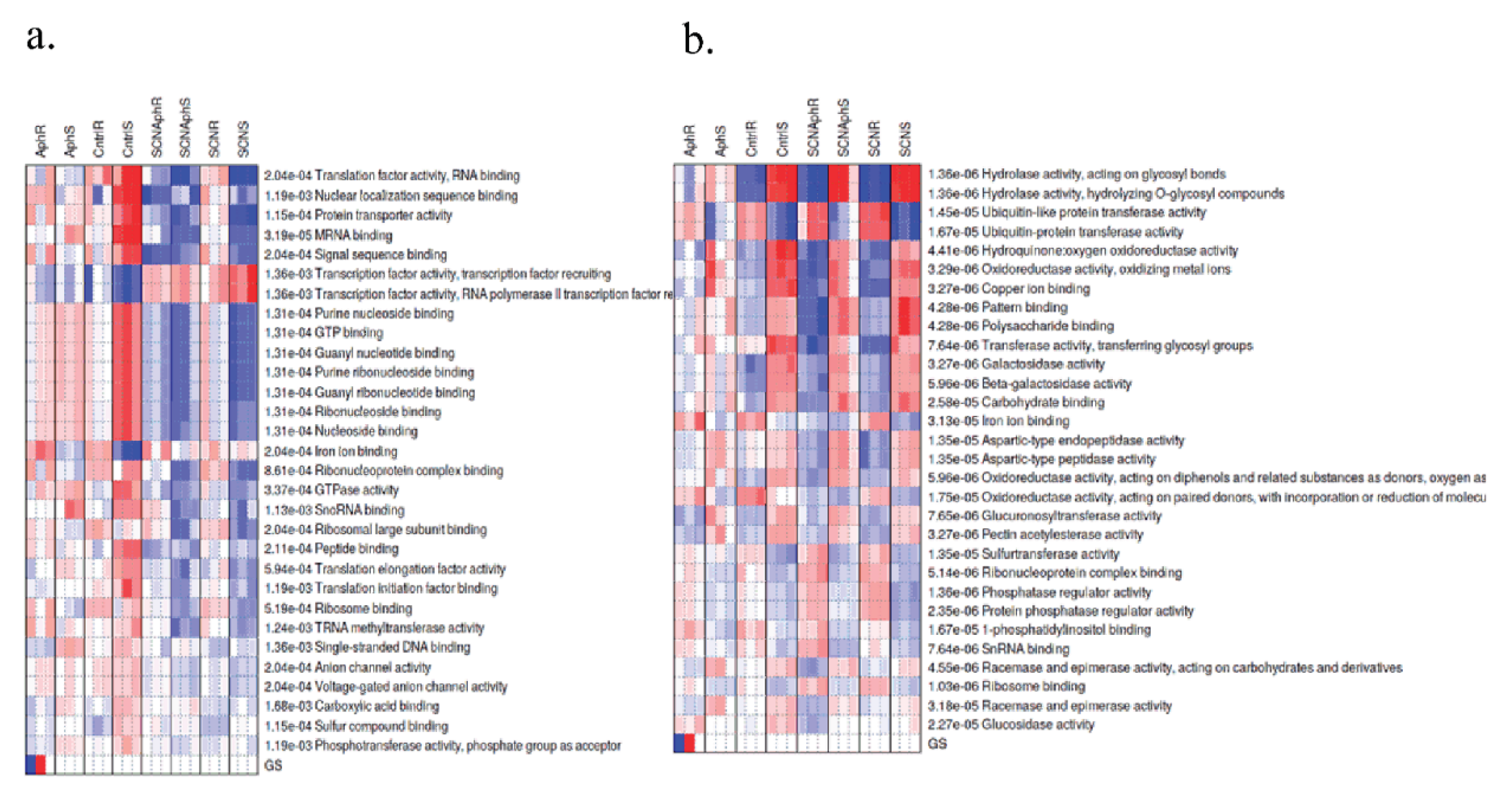

2.6. Within-Cultivar Contrasts Show Fewer DEGs in the Resistant Genotype and Identify Interaction-focused Candidates

2.7. Transcription Factor Motif Enrichment Suggests Distinct Regulatory Regimes in Early vs. Late Responses

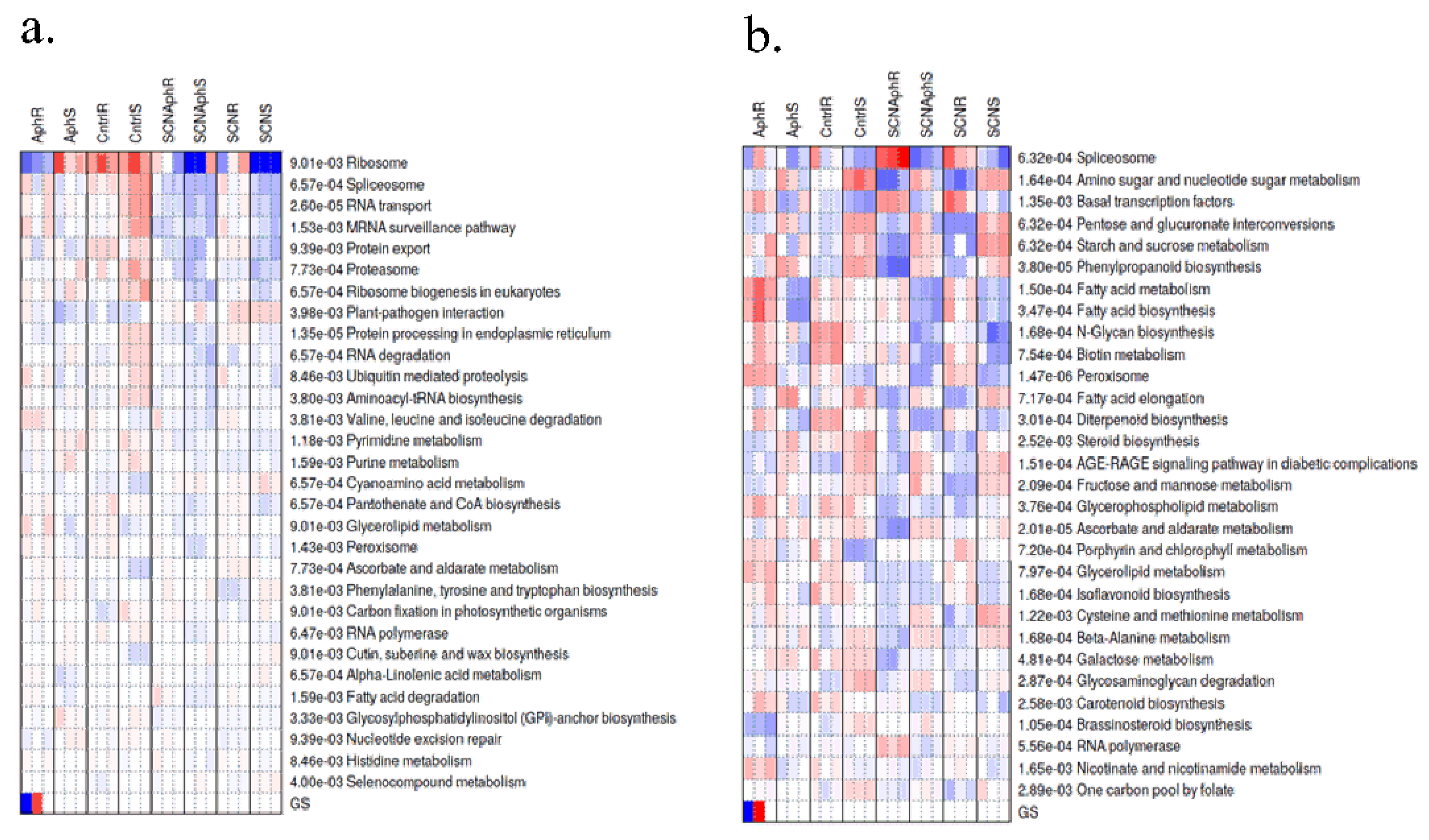

2.4. Pathway-Level Analysis Separates Early Lipid/Defense Signaling from Late Carbohydrate and Specialized Metabolism—

3. Discussion

3.1. Host Genotype Shapes the Direction of SCN–SBA Interactions

3.2. Time-Resolved Transcriptomes Reveal an Early Signaling Phase and a Late Metabolic/Redox Phase

3.3. Candidate Mechanisms for MN1806CN Resilience Under Combined SCN: SBA Pressure

3.4. Expression Patterns at SCN QTL-Linked Genes Support Known Resistance Biology

3.5. Pathway Enrichment Supports a Working Model Integrating Defense Signaling and Resource Dynamics

3.6. Practical Implications and Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Pest Populations

4.2. Greenhouse Experimental Design and Inoculation/Infestation

4.3. Aphid Counts and SCN Egg Quantification

4.4. Root Sampling, RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

4.5. RNA-Seq Preprocessing, Mapping, Quantification, and Normalization

4.6. Differential Expression and Candidate-Gene Analyses

4.7. Co-Expression Networks, Functional Enrichment, and Motif Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analyses for Phenotypes

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.; Yuan, F.; Fu, X.; Zhu, D. Profiling and relationship of water-soluble sugar and protein compositions in soybean seeds. Food chemistry 2016, 196, 776–782.

- USDA-ERS. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Soybeans and Oil Crops. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/soybeans-and-oil-crops (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Hartman, G.; Domier, L.; Wax, L.; Helm, C.; Onstad, D.; Shaw, J.; Solter, L.; Voegtlin, D.; d’Arcy, C.; Gray, M. Occurrence and distribution of Aphis glycines on soybeans in Illinois in 2000 and its potential control. Plant Health Progr. doi 2001, 10.

- Wrather, J.A.; Koenning, S.R. Estimates of disease effects on soybean yields in the United States 2003 to 2005. Journal of nematology 2006, 38, 173.

- McCarville, M.T.; O’Neal, M.; Tylka, G.L.; Kanobe, C.; MacIntosh, G.C. A nematode, fungus, and aphid interact via a shared host plant: implications for soybean management. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2012, 143, 55–66.

- McCarville, M.T.; Soh, D.H.; Tylka, G.L.; O’Neal, M.E. Aboveground feeding by soybean aphid, Aphis glycines, affects soybean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines, reproduction belowground. PloS one 2014, 9.

- Hill, C.; Chirumamilla, A.; Hartman, G. Resistance and virulence in the soybean-Aphis glycines interaction. Euphytica 2012, 186, 635–646.

- Koenning, S.R.; Wrather, J.A. Suppression of soybean yield potential in the continental United States by plant diseases from 2006 to 2009. Plant Health Progress 2010, 10.

- Niblack, T.; Lambert, K.; Tylka, G. A model plant pathogen from the kingdom animalia: Heterodera glycines, the soybean cyst nematode. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 283–303.

- Olson, K.D.; Badibanga, T.M.; DiFonzo, C. Farmers’ awareness and use of IPM for soybean aphid control: report of survey results for the 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007 crop years; 2008.

- Niblack, T.J.P.d. Soybean cyst nematode management reconsidered. 2005, 89, 1020–1026.

- Ragsdale, D.W.; Landis, D.A.; Brodeur, J.; Heimpel, G.E.; Desneux, N. Ecology and management of the soybean aphid in North America. Annual review of entomology 2011, 56, 375–399.

- Koch, R.L.; Potter, B.D.; Glogoza, P.A.; Hodgson, E.W.; Krupke, C.H.; Tooker, J.F.; DiFonzo, C.D.; Michel, A.P.; Tilmon, K.J.; Prochaska, T.J. Biology and economics of recommendations for insecticide-based management of soybean aphid. Plant Health Progress 2016, 17, 265–269.

- Varenhorst, A.J.; O’Neal, M.E. The response of natural enemies to selective insecticides applied to soybean. Environmental entomology 2012, 41, 1565–1574.

- Tylka, G.L. Understanding soybean cyst nematode HG types and races. Plant Health Progress 2016, 17, 149–151.

- Mitchum, M.G.; Wrather, J.A.; Heinz, R.D.; Shannon, J.G.; Danekas, G. Variability in distribution and virulence phenotypes of Heterodera glycines in Missouri during 2005. Plant Dis 2007, 91, doi:10.1094/pdis-91-11-1473.

- Hesler, L.S.; Chiozza, M.V.; O’neal, M.E.; MacIntosh, G.C.; Tilmon, K.J.; Chandrasena, D.I.; Tinsley, N.A.; Cianzio, S.R.; Costamagna, A.C.; Cullen, E.M. Performance and prospects of R ag genes for management of soybean aphid. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2013, 147, 201–216.

- Mitchum, M.G. Soybean resistance to the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines: an update. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1444–1450.

- Megías, A.G.; Müller, C. Root herbivores and detritivores shape above-ground multitrophic assemblage through plant-mediated effects. Journal of Animal Ecology 2010, 79, 923–931.

- Hong, S.; Donaldson, J.; Gratton, C. Soybean cyst nematode effects on soybean aphid preference and performance in the laboratory. Environmental Entomology 2010, 39, 1561–1569.

- Hong, S.; MacGuidwin, A.; Gratton, C. Soybean aphid and soybean cyst nematode interactions in the field and effects on soybean yield. Journal of Economic Entomology 2011, 104, 1568–1574.

- Heeren, J.; Steffey, K.; Tinsley, N.; Estes, R.; Niblack, T.; Gray, M. The interaction of soybean aphids and soybean cyst nematodes on selected resistant and susceptible soybean lines. Journal of applied entomology 2012, 136, 646–655.

- Lewis, M.T.; Poelstra, J.W.; Michel, A.P. Host plant flooding stress in soybeans differentially impacts avirulent and virulent soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) biotypes. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 4897, doi:10.1038/s41598-025-87561-z.

- Qiu, S.; Wu, N.; Sun, X.; Xue, Y.; Xia, J. Chromosome-level genome assembly of soybean aphid. Scientific Data 2025, 12, 386.

- Hesler, L.S.; Beckendorf, E.A. Soybean aphids per plant among soybean lines containing various Rag genes. Ag Data Commons 2020.

- Lakhssassi, N.; Chhapekar, S.S.; Devkar, V.; Knizia, D.; El Baze, A.; Ye, H.; Vuong, T.; Patil, G.B.; Nguyen, H.T.; Meksem, K. Discovery of two tightly linked soybean genes at the qSCN10 (O) locus conferring broad-spectrum resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Communications Biology 2025, 8, 259, doi:10.1038/s42003-025-07633-8.

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Fan, F.; Qi, S.; Wang, M.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Q.; Duan, Y.; et al. Cyclo (Pro-Tyr) upregulates GmPOD53L to enhance soybean resistance to cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe). Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, Volume 16 - 2025, doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1628555.

- Ghavami, N.; Tenuta, M.; Tenuta, A.; Lange, D. Survey and first report of the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe) in soybean fields in the province of Manitoba, Canada. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2025, 47, 183–198, doi:10.1080/07060661.2024.2429537.

- Extention, I.S.U. Integrated Crop Management, Iowa State University Extension. SCN-resistant soybean varieties for 2025, including expanded Peking resistance sources. Available online: https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2024/10/scn-resistant-soybeans-varieties-2025-including-200-peking-resistance (accessed on December 30 2025).

- USDA-NIFA. USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Detecting insecticide-resistant soybean aphids before field failures cost farmers. Project Information, mid-2020s. Available online: https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1024320-detecting-insecticide-resistant-aphids-before-field-failures-cost-farmers.html (accessed on December 30 2025).

- Griffith, M.; Walker, J.R.; Spies, N.C.; Ainscough, B.J.; Griffith, O.L. Informatics for RNA sequencing: a web resource for analysis on the cloud. PLoS computational biology 2015, 11, e1004393.

- Shan, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Hao, W.; Yuan, Y. Transcriptome profile analysis of maize seedlings in response to high-salinity, drought and cold stresses by deep sequencing. Plant molecular biology reporter 2013, 31, 1485–1491.

- Neupane, S.; Varenhorst, A.J.; Nepal, M.P. Transcriptome profiling of induced susceptibility effects on soybean–soybean aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) interaction. BMC Research Notes 2019, 12, 325, doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4372-3.

- Soler, R.; Erb, M.; Kaplan, I. Long distance root–shoot signalling in plant–insect community interactions. Trends in Plant Science 2013, 18, 149–156.

- Thompson, M.N.; Grunseich, J.M.; Marmolejo, L.O.; Aguirre, N.M.; Bradicich, P.A.; Behmer, S.T.; Suh, C.P.-C.; Helms, A.M. Undercover operation: belowground insect herbivory modifies systemic plant defense and repels aboveground foraging insect herbivores. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 10, 1033730.

- Topalović, O.; Bak, F.; Santos, S.; Sikder, M.M.; Sapkota, R.; Ekelund, F.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Vestergård, M. Activity of root-knot nematodes associated with composition of a nematode-attached microbiome and the surrounding soil microbiota. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2023, 99, fiad091.

- Van Dam, N.M.; Raaijmakers, C.E.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Root herbivory reduces growth and survival of the shoot feeding specialist Pieris rapae on Brassica nigra. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2005, 115, 161–170.

- Bezemer, T.; De Deyn, G.; Bossinga, T.; Van Dam, N.; Harvey, J.; Van der Putten, W. Soil community composition drives aboveground plant–herbivore–parasitoid interactions. Ecology Letters 2005, 8, 652–661.

- Wurst, S.; van der Putten, W.H. Root herbivore identity matters in plant-mediated interactions between root and shoot herbivores. Basic and Applied Ecology 2007, 8, 491–499.

- Hol, W.G.; De Boer, W.; Termorshuizen, A.J.; Meyer, K.M.; Schneider, J.H.; Van Dam, N.M.; Van Veen, J.A.; Van Der Putten, W.H.J.E.l. Reduction of rare soil microbes modifies plant–herbivore interactions. 2010, 13, 292–301.

- Vandegehuchte, M.L.; De La Peña, E.; Bonte, D.J.O. Interactions between root and shoot herbivores of Ammophila arenaria in the laboratory do not translate into correlated abundances in the field. 2010, 119, 1011–1019.

- Kuhlmann, F.; Müller, C. UV-B impact on aphid performance mediated by plant quality and plant changes induced by aphids. Journal of Plant Biology 2010, 12, 676–684.

- Huberty, A.F.; Denno, R.F. Plant water stress and its consequences for herbivorous insects: a new synthesis. Ecology 2004, 85, 1383–1398.

- Kaplan, I.; Halitschke, R.; Kessler, A.; Rehill, B.J.; Sardanelli, S.; Denno, R.F. Physiological integration of roots and shoots in plant defense strategies links above-and belowground herbivory. Ecology Letters 2008, 11, 841–851.

- Kutty, N.N.; Mishra, M. Dynamic distress calls: volatile info chemicals induce and regulate defense responses during herbivory. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1135000.

- Jiang, L.; Romero-Carvajal, A.; Haug, J.S.; Seidel, C.W.; Piotrowski, T. Gene-expression analysis of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, E1383–E1392.

- Nissan, N.; Puchacz, N.; Hooker, J.C.; Ste-Croix, D.T.; Zapata, G.; Lefebvre, F.; Charette, M.; Golshani, A.; Cober, E.; Mimee, B. Dynamic transcriptomic responses to soybean cyst nematode infection in soybean genotypes with contrasting resistance profiles. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 16, 1618387.

- Ralph, S.G.; Jancsik, S.; Bohlmann, J. Dirigent proteins in conifer defense II: Extended gene discovery, phylogeny, and constitutive and stress-induced gene expression in spruce (Picea spp.). Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1975–1991.

- Moura, J.C.M.S.; Bonine, C.A.V.; de Oliveira Fernandes Viana, J.; Dornelas, M.C.; Mazzafera, P. Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. Journal of integrative plant biology 2010, 52, 360–376.

- Wu, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Shang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, D.; Deng, X. Cloning and expression analysis of a dirigent protein gene from the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica. Progress in Natural Science 2009, 19, 347–352.

- Effenberger, I.; Zhang, B.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Klaiber, I.; Pfannstiel, J.; Wang, Q.; Schaller, A. Dirigent proteins from cotton (Gossypium sp.) for the atropselective synthesis of gossypol. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2015, 54, 14660–14663.

- Li, N.; Zhao, M.; Liu, T.; Dong, L.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Lu, W.J.F.i.p.s. A novel soybean dirigent gene GmDIR22 contributes to promotion of lignan biosynthesis and enhances resistance to Phytophthora sojae. 2017, 8, 1185.

- He, B.; Guo, W. The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Current opinion in cell biology 2009, 21, 537–542.

- Yun, H.S.; Sul, W.J.; Chung, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kwon, C. Secretory membrane traffic in plant–microbe interactions. New Phytologist 2023, 237, 53–59.

- Cook, D.E.; Lee, T.G.; Guo, X.; Melito, S.; Wang, K.; Bayless, A.M. Copy number variation of multiple genes at Rhg1 mediates nematode resistance in soybean. Science 2012, 338, doi:10.1126/science.1228746.

- Bayless, A.M.; Smith, J.M.; Song, J.; McMinn, P.H.; Teillet, A.; August, B.K.; Bent, A. Disease resistance through impairment of α-SNAP–NSF interaction and vesicular trafficking by soybean Rhg1. 2016, 113, E7375–E7382.

- Cook, D.; Bayless, A.; Wang, K.; Guo, X.; Song, Q.; Jiang, J.; Bent, A.J.P.p. Distinct copy number, coding sequence and locus methylation patterns underlie Rhg1-mediated soybean resistance to soybean cyst nematode. 2014, pp. 114.235952.

- Mahmood, A.; Bilyeu, K.D.; Škrabišová, M.; Biová, J.; De Meyer, E.J.; Meinhardt, C.G.; Usovsky, M.; Song, Q.; Lorenz, A.J.; Mitchum, M.G. Cataloging SCN resistance loci in North American public soybean breeding programs. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1270546.

- Cheng, A.-X.; Han, X.-J.; Wu, Y.-F.; Lou, H.-X. The Function and Catalysis of 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Oxygenases Involved in Plant Flavonoid Biosynthesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 1080–1095.

- Yang, Q.; Wang, G. Isoflavonoid metabolism in leguminous plants: an update and perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1368870.

- Suty, L.; Lequeu, J.; Lançon, A.; Etienne, P.; Petitot, A.-S.; Blein, J.-P. Preferential induction of 20S proteasome subunits during elicitation of plant defense reactions: towards the characterization of “plant defense proteasomes”. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2003, 35, 637–650.

- Liu, Y.; Jackson, E.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; van der Hoorn, R.A.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Proteolysis in plant immunity. The Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3099–3115.

- Martínez, M.; Cambra, I.; González-Melendi, P.; Santamaría, M.E.; Díaz, I. C1A cysteine-proteases and their inhibitors in plants. Physiologia Plantarum 2012, 145, 85–94, doi:doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01569.x.

- Meresa, B.K.; Matthys, J.; Kyndt, T. Biochemical Defence of Plants against Parasitic Nematodes. Plants 2024, 13, 2813.

- Lilley, C.; Urwin, P.; McPherson, M.; Atkinson, H. Characterization of intestinally active proteinases of cystnematodes. Parasitology 1996, 113, 415–424.

- Papolu, P.K.; Dutta, T.K.; Tyagi, N.; Urwin, P.E.; Lilley, C.J.; Rao, U. Expression of a Cystatin Transgene in Eggplant Provides Resistance to Root-knot Nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01122.

- Bruckhoff, V.; Haroth, S.; Feussner, K.; König, S.; Brodhun, F.; Feussner, I. Functional Characterization of CYP94-Genes and Identification of a Novel Jasmonate Catabolite in Flowers. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0159875, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159875.

- Latunde-Dada, A.O.; Cabello-Hurtado, F.; Czittrich, N.; Didierjean, L.; Schopfer, C.; Hertkorn, N.; Werck-Reichhart, D.; Ebel, J. Flavonoid 6-Hydroxylase from Soybean (Glycine maxL.), a Novel Plant P-450 Monooxygenase. 2001, 276, 1688–1695, doi:10.1074/jbc.M006277200.

- Zhang, H.; Kjemtrup-Lovelace, S.; Li, C.; Luo, Y.; Chen, L.P.; Song, B.-H. Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis Uncovers a Complex Regulatory Network for Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance in Wild Soybean (Glycine soja). Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 9699.

- Schaff, J.E.; Nielsen, D.M.; Smith, C.P.; Scholl, E.H.; Bird, D.M. Comprehensive Transcriptome Profiling in Tomato Reveals a Role for Glycosyltransferase in Mi-Mediated Nematode Resistance. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1079–1092, doi:10.1104/pp.106.090241%J Plant Physiology.

- Egelund, J.; Skjøt, M.; Geshi, N.; Ulvskov, P.; Petersen, B.L. A Complementary Bioinformatics Approach to Identify Potential Plant Cell Wall Glycosyltransferase-Encoding Genes. 2004, 136, 2609–2620, doi:10.1104/pp.104.042978%J Plant Physiology.

- Liu, S.; Kandoth, P.K.; Lakhssassi, N.; Kang, J.; Colantonio, V.; Heinz, R.; Yeckel, G.; Zhou, Z.; Bekal, S.; Dapprich, J.J.N.c. The soybean GmSNAP18 gene underlies two types of resistance to soybean cyst nematode. 2017, 8, 14822.

- Usovsky, M.; Gamage, V.A.; Meinhardt, C.G.; Dietz, N.; Triller, M.; Basnet, P.; Gillman, J.D.; Bilyeu, K.D.; Song, Q.; Dhital, B.; et al. Loss-of-function of an α-SNAP gene confers resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7629, doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43295-y.

- Macho, A.P.; Zipfel, C. Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Molecular cell 2014, 54, 263–272.

- Hewezi, T.; Piya, S.; Qi, M.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Rice, J.H.; Baum, T.J. Arabidopsis miR827 mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing of its ubiquitin E3 ligase target gene in the syncytium of the cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii to enhance susceptibility. Plant J. 2016, 88, 179–192, doi:doi:10.1111/tpj.13238.

- Walter, A.J.; Willforss, J.; Lenman, M.; Alexandersson, E.; Andreasson, E.J.E.J.o.P.P. RNA seq analysis of potato cyst nematode interactions with resistant and susceptible potato roots. 2018, 152, 531–539.

- Davis, E.L.; Hussey, R.S.; Mitchum, M.G.; Baum, T.J. Parasitism proteins in nematode–plant interactions. Current opinion in plant biology 2008, 11, 360–366.

- Howe, G.A. Jasmonates as signals in the wound response. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2004, 23, 223–237.

- Li, Y.; Beisson, F.; Koo, A.J.; Molina, I.; Pollard, M.; Ohlrogge, J.J.P.o.t.N.A.o.S. Identification of acyltransferases required for cutin biosynthesis and production of cutin with suberin-like monomers. 2007, 104, 18339–18344.

- Dixon, R.A.; Achnine, L.; Kota, P.; Liu, C.-J.; Reddy, M.S.S.; Wang, L. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence—a genomics perspective. 2002, 3, 371–390, doi:doi:10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00131.x.

- Alon, M.; Malka, O.; Eakteiman, G.; Elbaz, M.; Moyal Ben Zvi, M.; Vainstein, A.; Morin, S. Activation of the Phenylpropanoid Pathway in Nicotiana tabacum Improves the Performance of the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci via Reduced Jasmonate Signaling. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e76619, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076619.

- Li, Y.; Zhen, S.; Shan, S.; Sun, B.; Li, J.; Hu, F.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, L.; Gu, X.; Cheng, W. Modulation of above-belowground plant-herbivore interactions by entomopathogenic nematodes. Applied Soil Ecology 2020, 148, 103479.

- Thompson, M.N.; Grunseich, J.M.; Marmolejo, L.O.; Aguirre, N.M.; Bradicich, P.A.; Behmer, S.T.; Suh, C.P.-C.; Helms, A.M. Undercover operation: Belowground insect herbivory modifies systemic plant defense and repels aboveground foraging insect herbivores. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, Volume 10 - 2022, doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.1033730.

- Liu, S.; Kandoth, P.K.; Warren, S.D.; Yeckel, G.; Heinz, R.; Alden, J. A soybean cyst nematode resistance gene points to a new mechanism of plant resistance to pathogens. Nature 2012, 492, doi:10.1038/nature11651.

- Ros, R.; Muñoz-Bertomeu, J.; Krueger, S.J.T.i.p.s. Serine in plants: biosynthesis, metabolism, and functions. 2014, 19, 564–569.

- Wu, X.-Y.; Zhou, G.-C.; Chen, Y.-X.; Wu, P.; Liu, L.-W.; Ma, F.-F.; Wu, M.; Liu, C.-C.; Zeng, Y.-J.; Chu, A.E.J.F.i.p.s. Soybean cyst nematode resistance emerged via artificial selection of duplicated serine hydroxymethyltransferase genes. 2016, 7, 998.

- Neupane, S. Identification and Characterization of Stress Responsive Genes in Soybean and Sunflower. Electronic Theses and Dissertations., South Dakota State University, Brookings, South Dakota 2019.

| Gene ID | log2foldchange | p-value | Top Arabidopsis Hit | Gene Description | Gene Ontology Biological Process |

| Glyma.03g044900 | 8.04 | 7.16E-03 | AT5G49040.1 | Disease resistance-responsive (dirigent-like protein) family protein | GO:0006952, GO:0009807 |

| Glyma.13g147600 | -3.59 | 6.27E-03 | AT2G36690.1 | 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase superfamily protein | GO:0009058, GO:0055114 |

| Glyma.16g214400 | 7.50 | 4.90E-03 | AT5G58430.1; ATEXO70B1, EXO70B1 | exocyst subunit exo70 family protein B1 | GO:0006887, GO:0006904, GO:0009738, GO:0035556 |

| Glyma.20g089400 | -1.04 | 2.81E-04 | AT5G15610.2 | Proteasome component (PCI) domain protein | GO:0006302, GO:0006312, GO:0007062, GO:0007129, GO:0007131, GO:0008150, GO:0009560, GO:0009909, GO:0034968, GO:0042138, GO:0045132 |

| Enrichment FDR | Genes in list | Total genes | Functional Category | Genes |

| 0.000104666 | 6 | 236 | Quercetin 3-O-glucosyltransferase activity | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400, Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.000104666 | 6 | 236 | Quercetin 7-O-glucosyltransferase activity | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.000894105 | 6 | 371 | UDP-glucosyltransferase activity | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.002120752 | 6 | 458 | Glucosyltransferase activity | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.004252586 | 6 | 544 | UDP-glycosyltransferase activity | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.027351491 | 6 | 812 | Transferase activity, transferring hexosyl groups | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100 |

| 0.029538121 | 7 | 1139 | Transferase activity, transferring glycosyl groups | Glyma.01G046300, Glyma.09G128300, Glyma.09G162400 Glyma.11G000500, Glyma.14G175400, Glyma.16G158100, Glyma.20G004900 |

| 0.037769863 | 2 | 63 | Protein-disulfide reductase activity | Glyma.08G295600, Glyma.18G127400 |

| 0.049127578 | 2 | 78 | Thioredoxin-disulfide reductase activity | Glyma.08G295600, Glyma.18G127400 |

| 0.049127578 | 2 | 81 | Oxidoreductase activity, acting on a sulfur group of donors, disulfide as acceptor | Glyma.08G295600, Glyma.18G127400 |

| 0.049282369 | 4 | 478 | Calcium ion binding | Glyma.06G079900, Glyma.12G089800, Glyma.03G157800, Glyma.13G191200 |

| TF | Motif | TF family | FDR | TF | Motif | TF family | FDR | |

| 5 dpi (Upregulated) | 30 dpi (upregulated) | |||||||

| Glyma0041s00360.1 | GCTGTCA | Homeodomain | 2.50E-02 | Glyma03g04500.1 | ATA | TBP | 1.50E-08 | |

| Glyma01g42410.1 | GTCA | Homeodomain | 2.50E-02 | Glyma08g08220.1 | ACACGTG | bZIP | 2.80E-06 | |

| Glyma01g03450.1 | GTCA | Homeodomain | 2.50E-02 | Glyma19g30680.1 | GACGTG | bZIP | 4.30E-06 | |

| Glyma03g39040.1 | TGACGGC | Homeodomain | 2.50E-02 | Glyma01g01740.1 | ACGTGG | bZIP | 4.30E-06 | |

| Glyma01g43420.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 3.00E-02 | Glyma01g00600.1 | GGATAA | Myb/SANT | 1.30E-05 | |

| Glyma01g43130.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 3.00E-02 | Glyma01g38380.1 | ACGTGGC | bZIP | 1.30E-05 | |

| Glyma07g36640.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 3.10E-02 | Glyma13g43120.1 | GGATAA | Myb/SANT | 1.30E-05 | |

| Glyma15g37120.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 3.20E-02 | Glyma04g04170.1 | ACACGTG | bZIP | 1.30E-05 | |

| Glyma02g45530.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 3.20E-02 | Glyma06g01700.1 | ATATAATT | AT hook | 1.90E-05 | |

| Glyma10g13720.1 | GGTCAA | WRKY | 3.20E-02 | Glyma09g06770.1 | CACGTGT | bHLH | 1.90E-05 | |

| Glyma03g37870.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 3.20E-02 | Glyma02g00980.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 1.90E-05 | |

| Glyma02g15920.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 3.20E-02 | Glyma01g04610.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 2.60E-05 | |

| Glyma01g39600.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 3.80E-02 | Glyma01g39450.1 | CCACGTG | bHLH | 4.30E-05 | |

| Glyma07g05660.1 | TTACGTAA | NAC/NAM | 3.80E-02 | Glyma01g39360.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 4.80E-05 | |

| Glyma01g00510.1 | TGTCGG | B3 | 4.40E-02 | Glyma08g41620.1 | GCCACGTG | bHLH | 4.80E-05 | |

| Glyma09g06980.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 5.60E-02 | Glyma06g41620.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 6.20E-05 | |

| Glyma01g06150.1 | GTCAA | NAC/NAM | 5.60E-02 | Glyma01g02250.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 6.50E-05 | |

| Glyma01g21020.1 | TGACGTCA | bZIP | 5.60E-02 | Glyma03g04500.1 | GGAT | Myb/SANT | 6.50E-05 | |

| Glyma06g17690.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 6.00E-02 | Glyma08g08220.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 8.80E-05 | |

| Glyma04g06470.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 6.70E-02 | Glyma19g30680.1 | CGCGT | CG-1 | 8.80E-05 | |

| Glyma05g36290.1 | ATA | TBP | 1.50E-08 | |||||

| Glyma03g32740.1 | ACACGTG | bZIP | 2.80E-06 | |||||

| Glyma05g31190.1 | GACGTG | bZIP | 4.30E-06 | |||||

| 30 dpi (down regulated) | ||||||||

| Glyma09g06980.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 6.30E-08 | |||||

| Glyma04g08060.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 6.30E-08 | |||||

| Glyma01g06870.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 6.30E-08 | |||||

| Glyma03g04500.1 | ATA | TBP | 1.20E-07 | |||||

| Glyma02g15920.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 1.20E-07 | |||||

| Glyma01g43420.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 2.00E-07 | |||||

| Glyma09g39040.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 2.00E-07 | |||||

| Glyma01g09010.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 2.60E-07 | |||||

| Glyma03g37870.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 2.60E-07 | |||||

| Glyma19g30680.1 | GACGTG | bZIP | 3.00E-07 | |||||

| Glyma05g07490.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 3.00E-07 | |||||

| Glyma01g43130.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 3.10E-07 | |||||

| Glyma02g01420.1 | AGTCAACG | WRKY | 3.20E-07 | |||||

| Glyma09g39000.1 | AGTCAA | WRKY | 3.20E-07 | |||||

| Glyma01g39600.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 3.70E-07 | |||||

| Glyma03g32740.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 4.50E-07 | |||||

| Glyma02g45530.1 | GTCAA | WRKY | 4.50E-07 | |||||

| Glyma02g00980.1 | CACGTG | bHLH | 4.50E-07 | |||||

| Glyma01g05050.1 | GTCAACG | WRKY | 4.70E-07 | |||||

| Glyma06g17690.1 | GTCAAC | WRKY | 4.80E-07 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).