Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

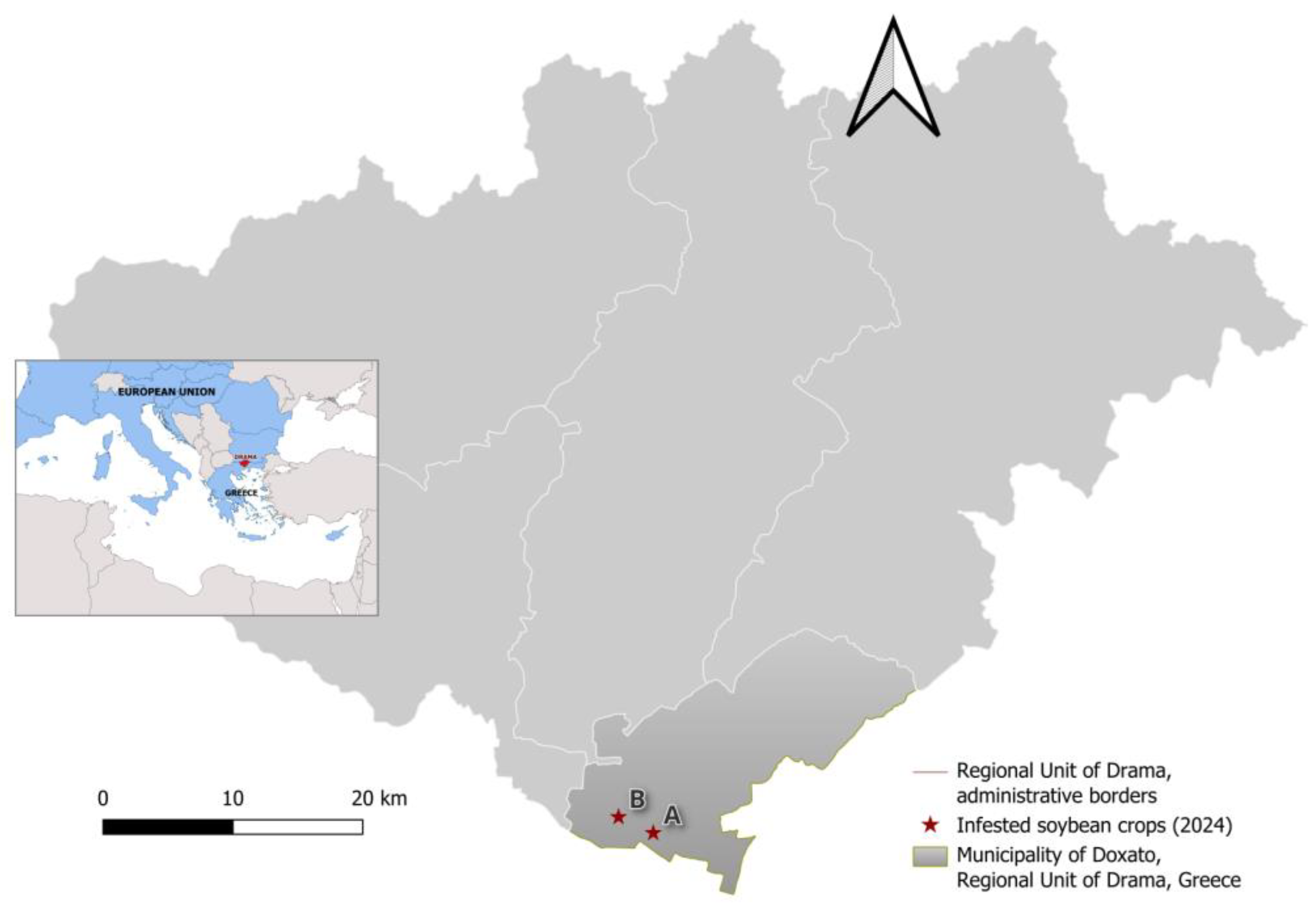

2.1. Location of Infestation and Sampling

2.2. Species Identification

2.3. Assessment of the Damage Extent

3. Results

3.1. Species Identification

3.2. Description of the Damage

3.3. Estimation of the Damage Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aitken, A.D. A Key to the Larvae of Some Species of Phycitinae (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) Associated with Stored Products, and of Some Related Species. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1963, 54, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplehorn, C.A.; Johnson, N.F.; Borror, D.J. Borror and DeLong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects; 7th ed.; Thomson, Brooks/Cole: Australia, 2005; ISBN 978-0-03-096835-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Yang, M.; Li, M.; Jin, Z.; Yang, N.; Yu, H.; Liu, W. Climate Change Facilitates the Potentially Suitable Habitats of the Invasive Crop Insect Ectomyelois Ceratoniae (Zeller). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K.B.; Topalidis, I.; Avtzis, D.N.; Kaltsidis, A.; Roditakis, E. Cryptoblabes gnidiella Millière (Pyralidae, Phycitinae): An Emerging Grapevine Pest in Greece. Insects 2025, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K.B.; Karataraki, A.; Roditakis, N.E.; Roditakis, E. Euzophera Bigella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and Dasineura Oleae (F. Low) (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae): Emerging Olive Crop Pests in the Mediterranean? J. Pest. Sci. 2012, 85, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutytska, N.V.; Stankevych, S.; Romanov, O.; Mikheev, V.G.; Balan, O. Harmfulness of pea pod borer (Etiella zinckenella Tr. 1832) in soybeans in the eastern Forest-Steppe of Ukraine. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2021, 11, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taphizadeh, R.; Talebi, A.A.; Fathipour, Y.; Khalghani, J. Effect of ten soybean cultivars on development and reproduction of lima bean pod borer, Etiella zinckenella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) under laboratory conditions. Appl. Ent. Phytopath. 2012, 79, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, R.P.; Borden, J.H.; Angerilli, N.P.D.; Rauf, A. A Comparison of the Developmental and Reproductive Biology of Two Soybean Pod Borers, Etiella spp. in Indonesia. Entomologia Exp Applicata 2000, 97, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, H.; Shepard, B.M. ; Nasikin Damage Incidence by Etiella Zinckenella in Soybean in East Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Pest Management 1998, 44, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, H.; Aziz, A.; Machrus, M. On-Farm Evaluation of Measures to Monitor and Control Soybean Pod-Borer Etiella Zinckenella in East Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Pest Management 2000, 46, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballanger, Y. , Bernard, F., Segura, R., Lecomte, V., Duroueix, U. 2005. La pyrale des haricots (Etiella zinckenella Treitschke): Nouveau ravageur du soja en France. AFPP – 7e Conférence Internationale sur les Ravageurs en Agriculture, Montpellier; 26 et 27 Octobre 2005. Available at: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20093018583.

- Naito, A.; Harnoto; Iqbal, A. ; Hattori, I. Notes on the Morphology and Distribution of Etiella Hobsoni (BUTLER), a New Soybean Podborer in Indonesia, with Special Reference to Comparisons with Etiella Zinckenella (Treitschke): Lepidoptera: Pyralidae. Appl. entomol. Zool. 1986, 21, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Yadav, S.S. ; Manisha; Sindhu. Studies on Biology and Morphometrics of Etiella Zinckenella (Lepidoptera) on Lentil under Laboratory Conditions. IJPSS. [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I 273 from diverse Metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avtzis, D.N.; Markoudi, V.; Mizerakis, V.; Devalez, J.; Nakas, G.; Poulakakis, N.; Petanidou, T. The Aegean Archipelago as Cradle: Divergence of the Glaphyrid Genus Pygopleurus and Phylogeography of P. foina. Syst. Biodivers. 2021, 19, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanç, F.; Beyarslan, A. A Study on Microgastrinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) Species in Gökçeada and Bozcaada. Turk. J. Zool. 2021, 25, Article–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Yu, M.; Zhong, M. Warming Decreases Photosynthates and Yield of Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] in the North China Plain. The Crop Journal 2016, 4, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Sita, K.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Kumar, R.; Bhogireddy, S.; Varshney, R.K.; HanumanthaRao, B.; Nair, R.M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Nayyar, H. Drought or/and Heat-Stress Effects on Seed Filling in Food Crops: Impacts on Functional Biochemistry, Seed Yields, and Nutritional Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinod, M.; Patil, R.H. Seasonal Incidence of Pulse Pod Borer Etiella zinckenella (Treitschke) on Soybean and Its Relation with Abiotic Factors. Environ. Ecol. 2016, 35(1), 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, M. Oviposition Behavior of the Limabean Pod Borer, Etiella Zinckenella TREITSCHKE (Lepidoptera : Pyralidae) on the Soybean. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1986, 21, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, J. 1988. A survey of the European species of Apanteles Forst. (Hymenoptera, Braconidae: Microgastrinae) XI. "Homologization" of the species-groups of Apanteles s. 1. with Mason's generic taxa. Checklist of genera. Parasitoid / host list 1. Annls. Hist.-Nat. Mus. Natn. Hung. 1988, 80, 145–175. [Google Scholar]

- Karut, K.; Karaca, M.M.; Döker, İ.; Kazak, C. Two Promising Larval Parasitoids, Bracon (Habrobracon) Didemie and Dolichogenidea appellator (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) for Biological Control of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2023, 33, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, G.E.A.; Mohamed, S.A.; Khamis, F.; Du Plessis, H.; Ekesi, S. Biology and Performance of Two Indigenous Larval Parasitoids on Tuta Absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Sudan. Biocontrol Science and Technology 2018, 28, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowalter, T.D. Insect Ecology: An Ecosystem Approach; Fifth edition.; Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier: London San Diego, CA Cambridge, MA Oxford, 2022; ISBN 978-0-323-85673-7. [Google Scholar]

- Apriyanto, D.; Gunawan, E.; Sunardi, T. Resistance of Some Groundnut Cultivars to Soybean Pod Borer Etiella zinckenella Treit. (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Trop. Plant Pests Dis. 2008, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayu, M.S.Y.I.; Susanto, G.W.A.; Prayogo, Y.; Indiati, S.W. Antixenosis of Soybean Promising Lines and the Level of Resistance against Etiella Zinckenella, the Pod Borer. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 743, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patu, B.A.; Sarjan, M. ; Tarmizi; Tantawizal The Relationship of the Morphological Characteristics of Some Varieties of Soybean on the Attack Itensity of the Pod Borer (Etiella zinckenella Treitschke) in Two Different Cultivation Techniques. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 913, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patu, B.A.; Sarjan, M.; Tarmizi; Tantawizal. Comparison of the Number of Population and Attacks Intensity of the Pod Borer (Etiella Zinckenella) on Some Varieties of Soybean Crown with Two Cultivation Techniques in Dry Land. EJFOOD 2021, 3, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).