Submitted:

05 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Mitochondrial Genome Sequencing Analysis

2.2. Analysis of the Characteristics, Genetic Distances, and Phylogenetic Relationships of the Mitochondrial Genome

2.3. Collection and Processing of Distribution Data

2.4. Optimization and Construction of MaxEnt

2.5. Analysis of Potential Distribution

3. Results

3.1. Mitochondrial Genome Characteristics of H. rhodope

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationship and Genetic Distance between H. rhodope and Lepidopteran Moths

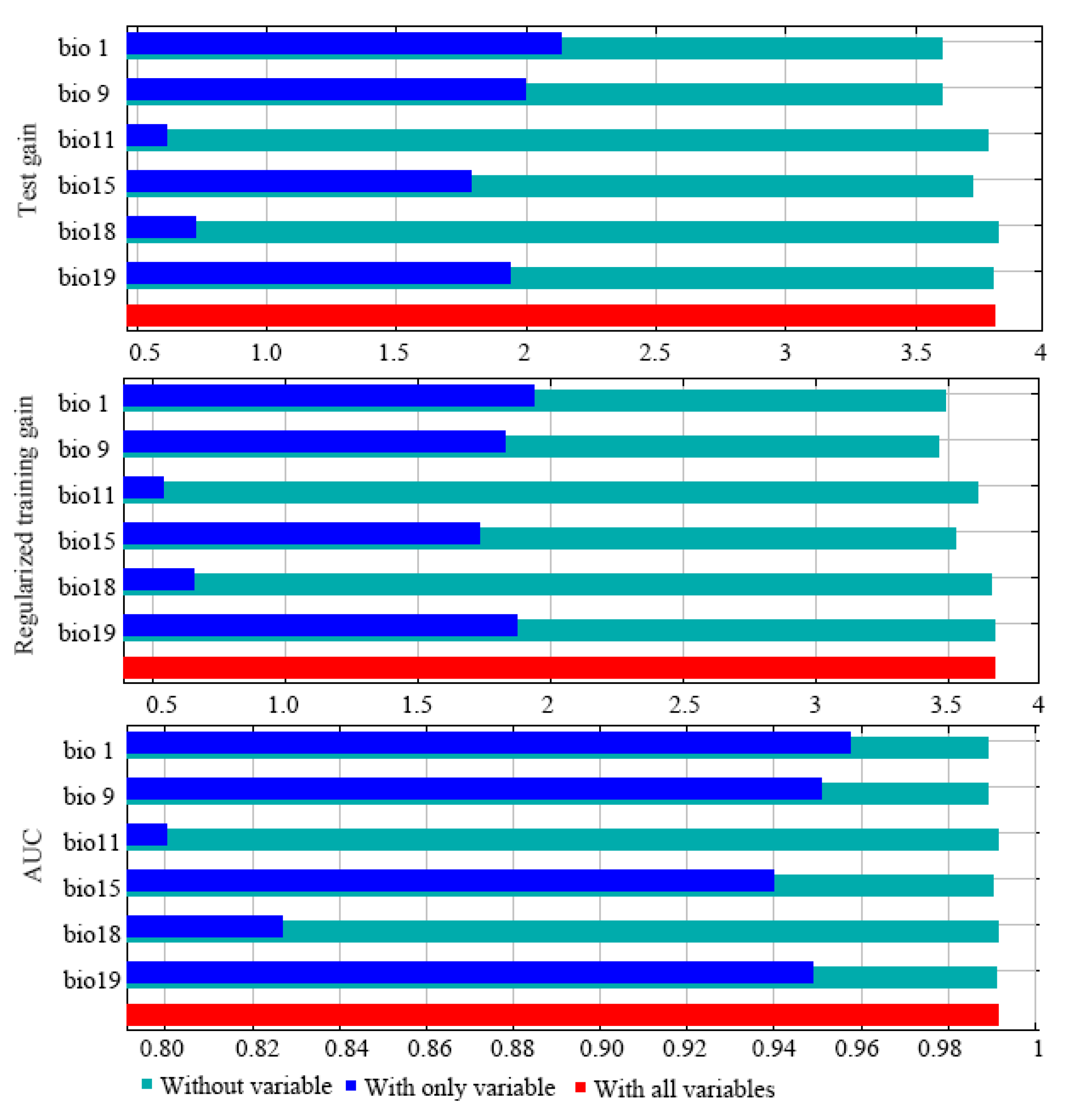

3.3. Screening of Key Environmental Factors and Suitable Area Predictions

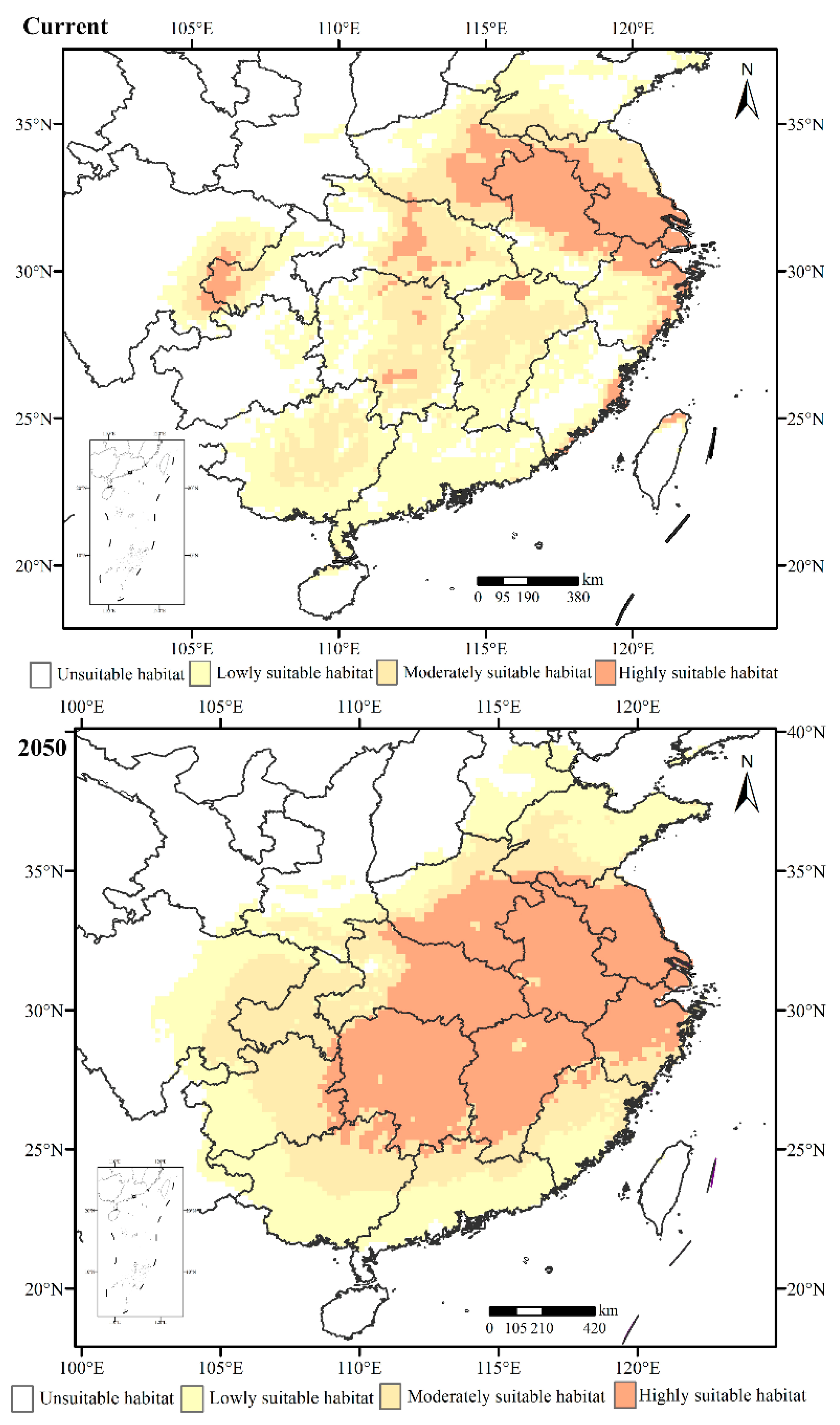

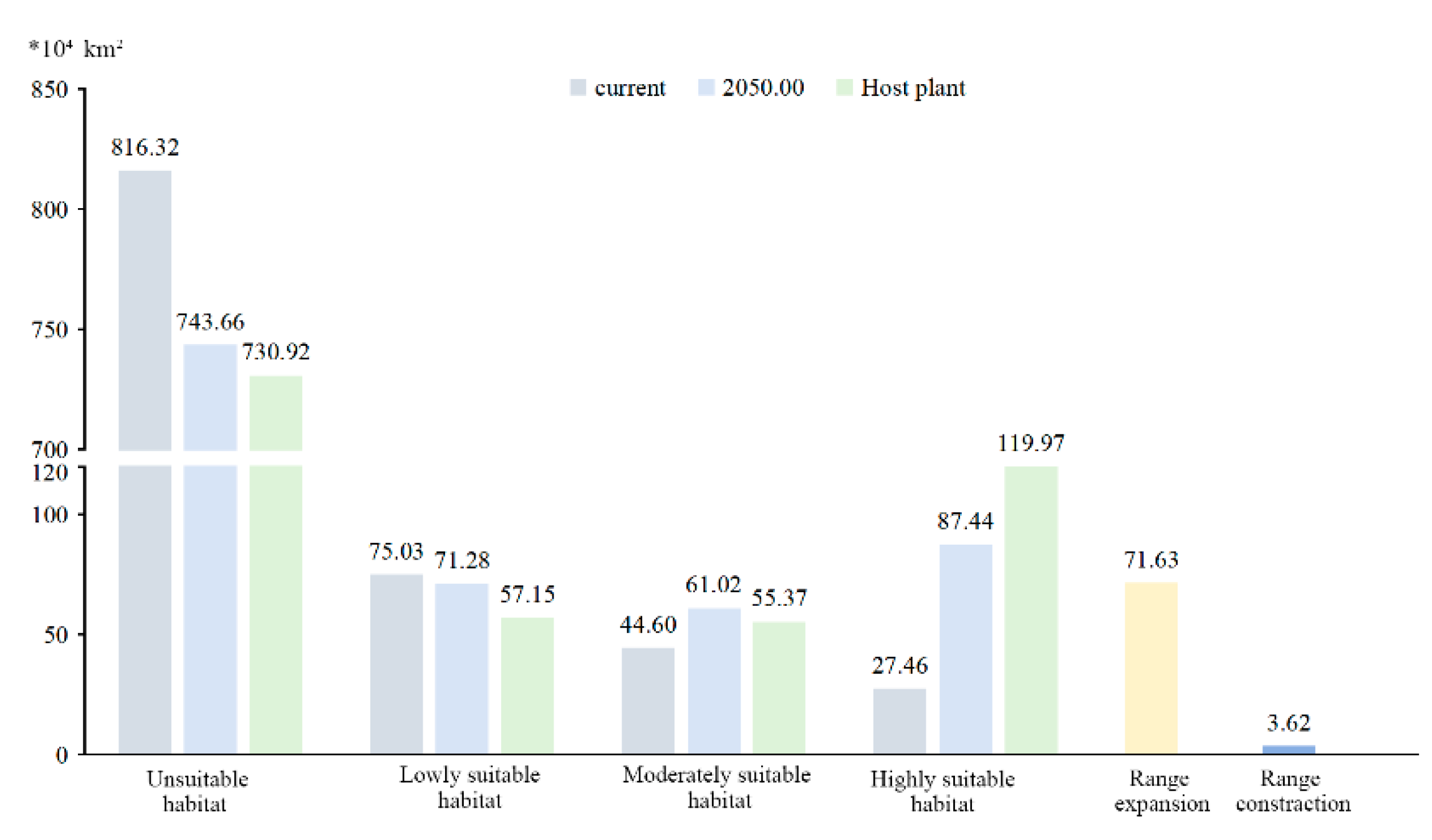

3.4. Forecasting Suitable Distribution of H. rhodope in Current Year and 2050

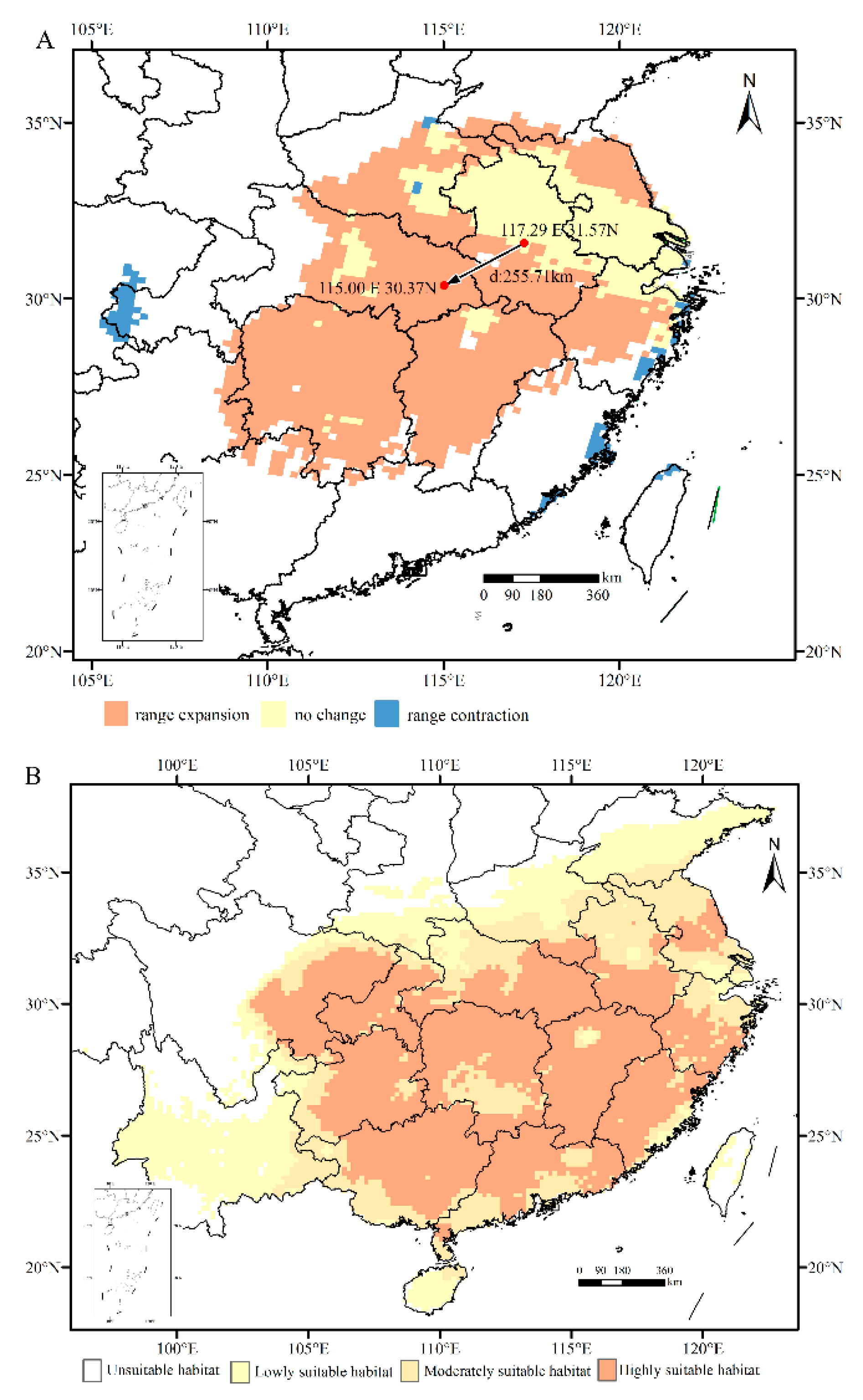

3.5. Centroid migration and current host plant B. polycarpa distribution of H. rhodope

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, B.K. A study on the bionomic characteristics and control of the Bischofia burnet Histia rhodope Cramer. J. Fujian Agric. Coll. 1980, 1, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.B.; Dong, J.F.; Sun, Y.L.; Hu, Z.J.; Lv, Q.H.; Li, D.X. Antennal transcriptome analysis and expression profiles of putative chemosensory soluble proteins in Histia rhodope Cramer (Lepidoptera: Zygaenidae). Comp. Biochem. Phys. D. 2020, 33, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.B.; Hu, Z.J.; Dong, J.F.; Zhu, P.H.; Li, D.X. Changes in the cold hardiness of overwintering larvae of Histia rhodope (Lepidoptera: Zygaenidae). Acta. Entomol. Sin. 2019, 62, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Dong, J.; Sun, Y.L.; Hu, Z.; Lu, Q.H.; Li, D. Identification and expression profiles of candidate chemosensory receptors in Histia rhodope (Lepidoptera: Zygaenidae). PeerJ 2020, 8, e10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Davis, D.R.; Cummings, M.P. Phylogeny and Evolution of Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.Y.; Zhang, Q.W.; Liang, L.L.; Qin, Y.T.; Li, S.; Bian, X. Comparative Mitogenomics and Phylogenetic Implications for Nine Species of the Subfamily Meconematinae (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae). Insects 2024, 15, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Hassan, M.A.; Xie, B.Q.; Wu, K.Q.; Naveed, H.; Yan, M.; Dietrich, C.; Duan, Y.N. Mitogenomic Analysis and Phylogenetic Implications for the Deltocephaline Tribe chiasmini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Deltocephalinae). Insects 2024, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.C.; Fang, J.X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.F.; Liu, F.; Yu, C.M.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, X.B. Comparative analysis of eight mitogenomes of bark beetles and their phylogenetic implicaitons. Insects 2021, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Yan, L.P.; Pape, T.; Gao, Y.Y.; Zhang, D. Evolutionary insight into bot flies (Insecta: Diptera: Oestridae) from comparative analysis of the mitochondrial genomes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.C.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.X.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, S.F.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, X.B. Sequencing and analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Dendrolimus punctatus (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Sci. Silvae Sin. 2019, 12, 16–172. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.F.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, X.B. Lineage divergence of Dendrolimus punctatus in Southern China based on mitochondrial genome. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.Y.; Hasegawa, H.; Cooley, J.R.; Simon, C.; Yoshimura, J.; Cai, W.Z.; Li, H. Mitochondrial genomics reveals shared phylogeographic patterns and demographic history among three periodical cicada species groups. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.Y.; Zhu, D.H.; Abe, Y.; Ide, T.; Liu, Z.W. The complete mitochondrial genome and gene rearrangements in a gall wasp species, Dryocosmus liui (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea: Cynipidae). PeerJ 2023, 11, e15865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, T.; Heng, X.; Ao, T.C.; Gu, Z.F.; Wang, A.M.; Liu, C.S.; Yang, Y. The Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Two Rock Scallops (Bivalvia: Spondylidae) Indicate Extensive Gene Rearrangements and Adaptive Evolution Compared with Pectinidae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Tan, M.; Meng, G.; Yang, S.; Su, X.; Liu, S.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, A.; et al. Multiplex sequencing of pooled mitochondrial genomes- a crucial step toward biodiversity analysis using mito-metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.P.; Song, G.J.; Liu, P.; Li, G.P.; Liang, X.; Wang, H.T. Test on chemical control of Histia rhodope. Shandong For. Sci. Technol. 2018, 5, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.Y.; Jia, W.R.; Huang, Z.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, X.; Ding, J.H.; Geng, X.X.; Li, J. Complete mitochondrial genome of Histia rhodope Cramer (Lepidoptera: Zygaenidae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 2017, 2, 636–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.H.; Nix, H.A.; Busby, J.R.; Huchinson, M.F. Bioclim: the first species distribution modeling package, its early applicationsand relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y, Johnson AJ, Gao L, Wu CX, Hulcr J. Two new invasive Ips bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculiionidae) in mainland China and their potential distribution in Asia. Pest Manag. Sci. 4008.

- Wang, Y.J.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhao, G.H.; Zhang, F.G. Agastache rugosa Prediction of potential distribution areas and priority protected areas of based on Maxent model and Marxan model. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1200796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Huettmann, F.; Leathwick, J.R.; Lehmann, A.; et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Miroslav, D. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldock, C.; Stuart-Smith, R.D.; Albouy, C.; Cheung, W.L.; Edgar, G.J.; Mouillot, D.; Tjiputra, J.; Pellissier, L. A quantitative review of abundance-based species distribution models. Ecography 2022, 1, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.L.; Yao, D.D.; Jiang, H.X.; Qin, J.; Feng, Z. Predicting current and future potential distributions of the greater bandicoot rat (Bandicota indica) under climate change conditions. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 80,734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.L.; Liu, S.; Xu, C.Q.; Wei, H.S.; Guo, K.; Xu, R.; Qiao, H.L.; Lu, P.F. Prediction of Potential Distribution of Carposina coreana in China under the Current and Future Climate Change. Insect 2024, 15, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitry, A.; Anton, K.; McLean, J.S.; Pevzner, P.A. HYBRIDSPADES: An algorithm for hybrid assembly of short and long reads. Bioinformatics 2016, 7, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, S. MitoZ: A toolkit for animal mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, N.T.; Kocher, T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.M.; Chan, P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: Integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; IQ-TREE, R.L. 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clary, D.O.; Wolstenholme, D.R. The ribosomal RNA genes of Drosophila mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13, 4029–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F.; Nielsen, R.; Bollback, J.P. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science 2001, 294, 2310–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Gao, G.; Wei, J.F. Potential global distribution of Daktulosphaira vitifoliae under climate change based on MaxEnt. Insects 2021, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Boria, R.A.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; ENMeval, R.A. An R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for MAXENT ecological niche models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 12261, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, C.; Duan, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, G. Potentially suitable habitats of Daodi goji berry in China under climate change. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1279019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Soberón, J.; Pearson, R.; Anderson, R.; Martínezmeyer, E.; Nakamura, M.; Araújo, M. Ecological Niches and Geographic Distributions; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.K.; Fan, G.H.; Deng, C.R.; Duan, G.Z.; Li, J.L. Predicting the Distribution of Neoceratitis asiatica (Diptera: Tephritidae), a Primary Pest of Goji Berry in China, under Climate Change. Insects 2024, 15, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Despabiladeras, J.B.; Bautista, M.A.M. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Eggplant Fruit and Shoot Borer, Leucinodes orbonalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), and Comparison with Other Pyraloid Moths. Insects 2024, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Fang, L.J.; Zhang, Y.L. The Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Four Species in the Subfamily Limenitidinae (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae) and a Phylogenetic Analysis. Insects 2022, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Lee, E.M.; Seol, K.Y.; Yun, E.Y.; Lee, Y.B.; Hwang, J.S.; Jin, B.R. The mitochondrial genome of the Korean hairstreak, Coreana raphaelis (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Insect Mol. Biol. 2006, 15, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Cahill, V.; Ballment, E.; Benzie, J. The complete sequence of themitochondrial genome of the crustacean Penaeus monodom: Are malacostracancrustaceans more closely related to insects than to branchiopods? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, L.; Koutroumbas, G.; Kotsyfakis, M.; Louis, C. The mitochondrial genome of the mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Insect Mol. Biol. 2000, 9, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.E. Revision and phylogeny of the Limacodid-group families, with evolutionary studies on slug caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Zygaenoidea). Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 1996. 582, 1–102.

- Mutanen, M.; Wahlberg, N.; Kaila, L. Comprehensive gene and taxon coverage elucidates radiation patterns in moths and butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 2010, 277, 2839–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regier, J.C.; Mitter, C.; Zwick, A.; Bazinet, A.L.; Cummings, M.P.; et al. A large-scale, higher-level, molecular phylogenetic study of the insect order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e58568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Yonghen, Z.; Xing, G.; Yuefang, G.; Youben, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of Etersia aedea (Lepidoptera, Zygaenidae) and comparison with other zygaenid moth. Genomic 2019, 11, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, M.J.T.N.; Lees, D.C.; Simonsen, T.J. Towards a mitogenomic phylogeny of Lepidoptera using next generation sequence technology. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 79, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.N.; Xin, Z.Z.; Bian, D.D.; Chai, X.Y.; Zhou, C.L.; Tang, B.P. The first complete mitonchondrial genome for the subfamily Limacodidae and implications for the higher phylogeny of Lepidoptera. Sci. Rep-uk. 2016, 6, 35878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Lu, Y.Y.; Han, M.Y.; Li, L.L.; He, P.; Shi, A.; Bai, M. Using MaxEnt model to predict the potential distribution of three potentially invasive scarab beetles in China. Insects 2023, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Nawaz, Z. Predicting the impacts of climate change, soils and vegetation types on the geographic distribution of Polyporus umbellatus in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.C.; Fang, J.X.; Shi, X.; Yu, C.M.; Deng, M.; Zhang, S.F.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Han, F.Z.; Kong, X.B. ; Insights into the Divergence of Chinese Ips Bark Beetles during Evolutionary Adaptation. Biology 2022, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, O.F.; Souza, P.G.C.; Silva, R.S.; Santana, P.A.; Picano, M.C.; Kyerematen, R.; Sètamou, M.; Ekesi, S.; Borgemeister, C. Climate-induced range shifts of invasive species (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama). Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2534–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzitis, E.A.; Minigan, J.N.; Hallett, R.H.; Newman, J.A. Climate and host plant availability impact the future distribution of the bean leaf beetle (Cerotoma trifurcata). Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2778–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Xin, B.; Quinn, N.F.; Duan, J.J. Retrospective analysis of factors afecting the distribution of an invasive wood-boring insect using native range data: the importance of host plants. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).