1. Introduction

The stability and sustainability of the entire farmland ecosystem function can be maintained by ensuring the stability and health of the natural enemy community, thereby realizing the sustainable development of agricultural production [

1,

2]. The diversity of parasitoid wasp communities in rice fields is the basis for controlling pest outbreaks. A wide variety of parasitoids, such as Trichogrammatidae and Mymardiae, play an important role in controlling agricultural pests such as

Cnaphalocrocis medinalis,

Nilaparvata lugens, and

Sogatella furcifera [3-5]. However, management measures, seasonal and environmental changes affect the balance between rice pests and their natural enemies, and the diversity of parasitoids is constantly changing [6-8] . In a subtropical smallholder agroecosystem of typical rice, vegetable and sugarcane in southern China, the insect diversity of different types of strips was studied. It was found that pesticides, ridge vegetation or crop heterogeneity had significant effects on the biodiversity of beneficial insects [9-11]. Therefore, it is urgent to monitor and understand the diversity of natural enemies in the field to achieve the purpose of making full use of natural enemies.

The diversity of parasitoid wasps in the major rice ecosystems across Asia is exceptionally high, with approximately 240 species. Among these, 65 species use Hemiptera insects as hosts and 145 species attack Lepidoptera insects [

12,

13]. The latest survey found that there were 109 species of parasitoid wasps corresponding to Hemiptera insects in rice fields, with the most species in the family Mymaridae (31 species), followed by the family Dryinidae (21 species) [

14]. The small size and morphological similarities among closely related and cryptic species pose challenges in distinguishing many parasitoid wasps, and professional taxonomic experts are needed to help. The classification and identification based on morphological characteristics, such as external morphology and external genitalia, require a lot of professional knowledge, time and funds [

15,

16]. Due to this limitation, some studies only identified the taxonomic units of genus and family. Therefore, a method that can be applied quickly and effectively in various situations is needed.

In recent years, with the development of sequencing technology, the metabarcoding technology combining barcode and high-throughput sequencing has been more deeply and widely used in species diversity survey research [

17,

18]. Compared with the Sanger sequencing method, high-throughput sequencing retains the advantages of high sensitivity of first-generation sequencing, which can realize the rapid identification of a large number of species, and the sequencing fragment is small, which can reduce the situation that the target sequence can’t be amplified due to DNA degradation. The amplification range is wide, and the universal primers using DNA barcode are suitable for most insects [

19].

At present, there are few studies on the diversity of parasitoids in rice field based on molecular identification, only the first-generation sequencing of COI gene is used to identify a few parasitoids [

20], and the research on the diversity of parasitoids in rice field based on the high-throughput second-generation sequencing of metabarcoding technology needs to be further studied.

The extraction of samples for metabarcoding sequencing is usually a destructive method of tissue grinding and a non-destructive method of extracting DNA from the sample preservation solution [

21]. The destructive method of tissue grinding can directly obtain a large amount of DNA, but it will lead to sample destruction, thus losing the evidence of species morphological identification [

22,

23]. The method of extracting DNA from the ethanol of the preserved samples has been used in many studies [

12]. It is reported that this method is fast and does not lose diversity compared with other sample processing methods [

24]. However, it has been reported that the DNA extracted from ethanol only recovers 15.9% of the genera and 11.2% of the families of the morphological classification [

25], which will lose a lot of information. Based on this, in this study, from 2022 to 2023, the methods of Malaise traps and sweep netting were used to collect insects from double-cropping rice fields with different management modes.

Firstly, DNA was directly extracted from the ethanol of the preserved samples, followed by subsequent extraction through grinding the parasitoid wasp samples. The universal primers of DNA barcode region were used for amplification, and the sequencing library was prepared by using the Illumina platform for high-throughput sequencing. The data obtained by the two methods were analyzed and compared, to provide reliable information and methods for in-depth understanding and rapid monitoring of the species diversity of parasitoid wasps in rice fields.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection and storage

The specimens were collected from rice paddy field at the Wushan farm of the South China Agricultural University (WS) (23.162239N, 113.360629E), Conghua district (CH) (23.552548N, 113.583478E) and Zengcheng district (ZC) (23.275373N,113.699062E) in Guangdong Province, China, from March 2022 to November 2023. Samples were collected by sweep netting , and Malaise traps.

Five sampling areas were randomly established in each location. For each sampling area, 50 swings of the net along the 100 m along the ridge, used an insect net (handle length: 100 cm; net diameter: 38 cm). The sweeping approach achieved robust sampling by forcefully sweeping the net through the rice canopy[

26,

27]. The collecting jar of Malaise traps were replaced with a new jar full of 95% ethanol each month.

All sweep netting and Malaise trap samples from one location in March to June(early rice cropping) or August to November (late rice cropping) were mixed together, finally total twelve samples were collected. After the collected insect samples were brought back to the laboratory and kept in 95% ethanol and stored at -20℃.

2.2. DNA extraction and amplification

The total of preservative ethanol from samples were filtered through 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filters, connected to a gas-vacuum pump[

28]. Filters were torn into small pieces with fine tweezers and dried. Subsequently, DNA was extracted from the filters with the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Insect samples were covered with new 95% ethanol and stored at −20°C until further processing.

100 parasitic wasps were randomly taken from each sample. Those parasitoid wasps from each site were mixed together and divided into two samples. Each sample was homogenized by grinding the tissue using a sterilized electrical grounding rod. Subsequently, DNA extraction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions as mentioned above. Extraction success and DNA quality was checked on a 1% agarose gel.

PCR amplification was performed using the barcode universal primer mlCOlintF-jgHCO2198 [

29], which is suitable for high-throughput sequencing, to amplify mitochondrial COI gene fragments about 300bp in length. PCR was performed with Taq DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). The 50 μL PCR reaction mixture contained 0.25 μL of rTaq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL), 5 μL of 10×PCR Buffer (Mg2+, plus), dNTP mixture 4 μL, 2 μL F primer (10 μM), 2 μL R primer (10 μM), 5 μL of DNA and 35.75 μL of water. The PCR cycling conditions were 94 ◦C for 1 min, 35 cycles of 98 ◦C for 10 s, 55 ◦C for 30 s and 72 ◦C for 30s, and finally,72 ◦C for 5 min. The PCR products were used for NGS sequencing.

2.3. High throughput sequencing and data analyses

Purified PCR products were quantifiedC by Qubit 3.0 (Life Invitrogen). The pooled DNA product was used to construct Illumina Pair-End library following Illumina’s genomic DNA library preparation procedure. Then the amplicon library was paired-end sequenced (2 × 250) on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Shanghai BIOZERON Co., Ltd ) according to the standard protocols.

Raw fastq files were first demultiplexed using in-house perl scripts according to the barcode sequences information for each sample with the following criteria: (i) The 250 bp reads were truncated at any site receiving an average quality score <20 over a 10 bp sliding window, discarding the truncated reads that were shorter than 50 bp. (ii) exact barcode matching, 2 nucleotide mismatch in primer matching, reads containing ambiguous characters were removed. (iii) only sequences that overlap longer than 10 bp were assembled according to their overlap sequence. Reads which could not be assembled were discarded.

3. Results

3.1. OTUs taxonomic assignment

ethanol samples : After splicing and removing impurity, 7391894 sequences were obtained by high-throughput sequencing, with a total of 2311835324 bp and an average fragment size of 312.753 bp. Operational taxonomic units (OTU) clustering was carried out according to 97% similarity, and 243783 OTUs were obtained by removing chimera and repeat sequences. The OTUs abundance of 12 samples was flattened out for subsequent analysis. The coverage of this sequencing was calculated by subtracting the ratio of the number of OTUs containing only one sequence and the number of all sequences. The coverage of 12 samples was between 0.93-0.99 (

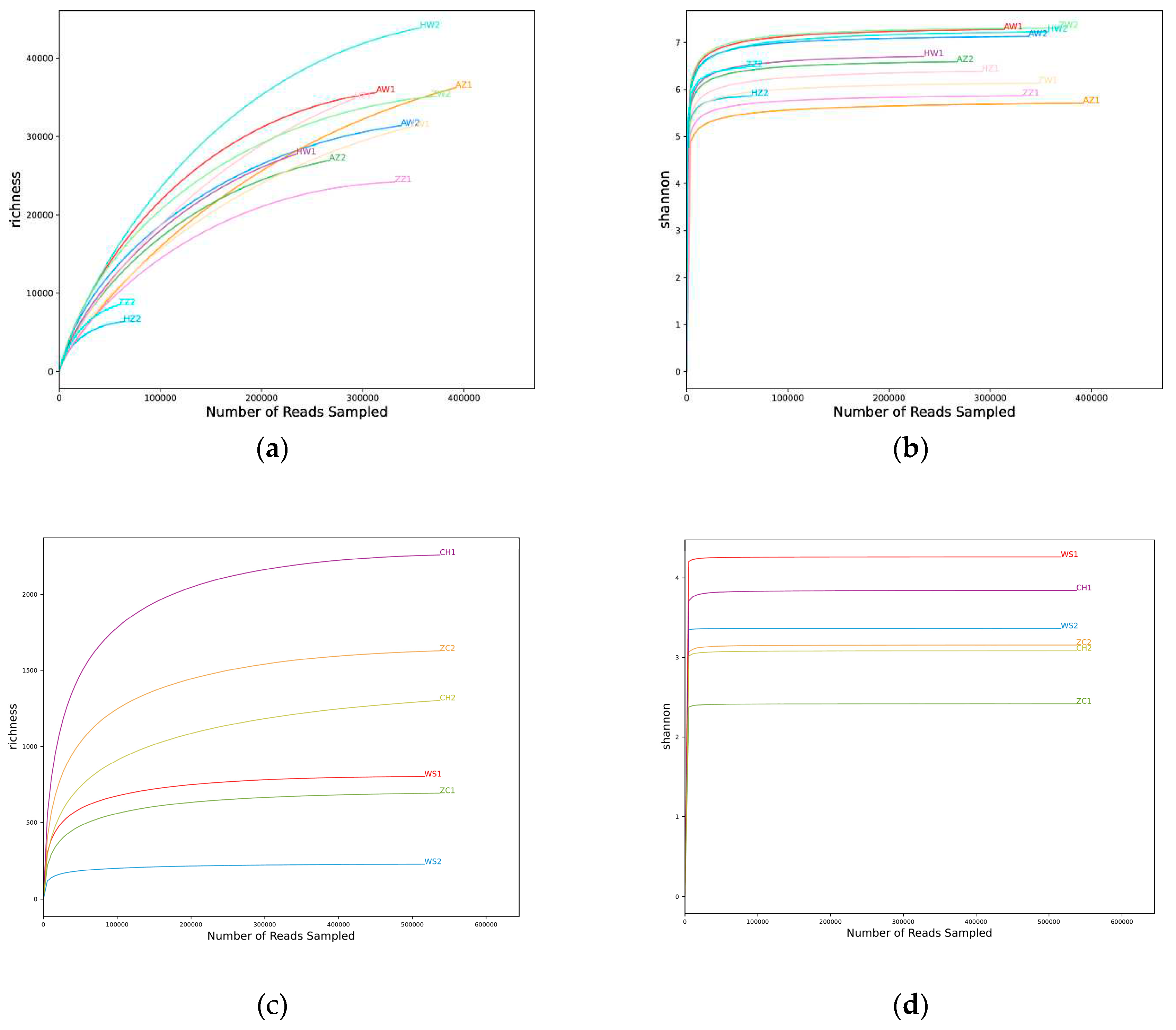

Table S1), indicating that the depth of sequencing was reasonable and could fully reflect the richness of samples. Both the Rarefaction curve (

Figure 1a) and Shannon-Wiener curve (

Figure 1b) tended to be flat, indicating that the sequencing data was large enough to reflect most of the biological information in the sample;

separated parasitoid wasp samples: 2444490 sequences were obtained by high-throughput sequencing with a total of 745281495 bp and an average fragment size of 304.88bp. OTUs clustering was carried out according to 97% similarity, and 4446 OTUs were obtained by removing chimera and repeat sequences in the clustering process. The OTUs abundance of 4 samples was flattened out for subsequent analysis. The coverage of this sequencing was calculated by subtracting from 1 the number of OTUs containing only one sequence and the ratio of all sequences. The coverage of 4 samples was greater than 0.999 (

Table S1), indicating that the depth of sequencing was reasonable and could fully reflect the richness of samples. Both the Rarefaction curve (

Figure 1c) and Shannon-Wiener curve (

Figure 1d) tend to be flat.

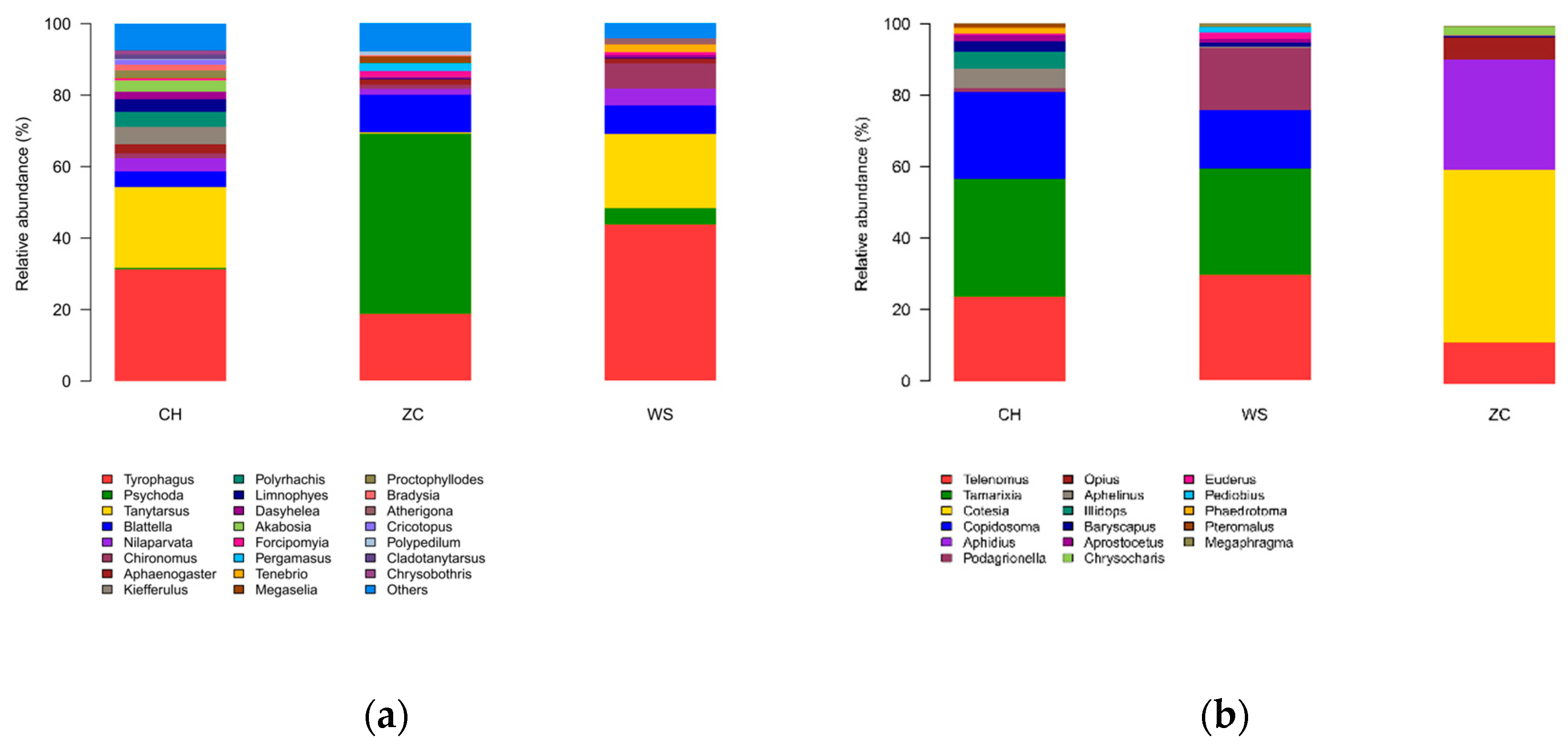

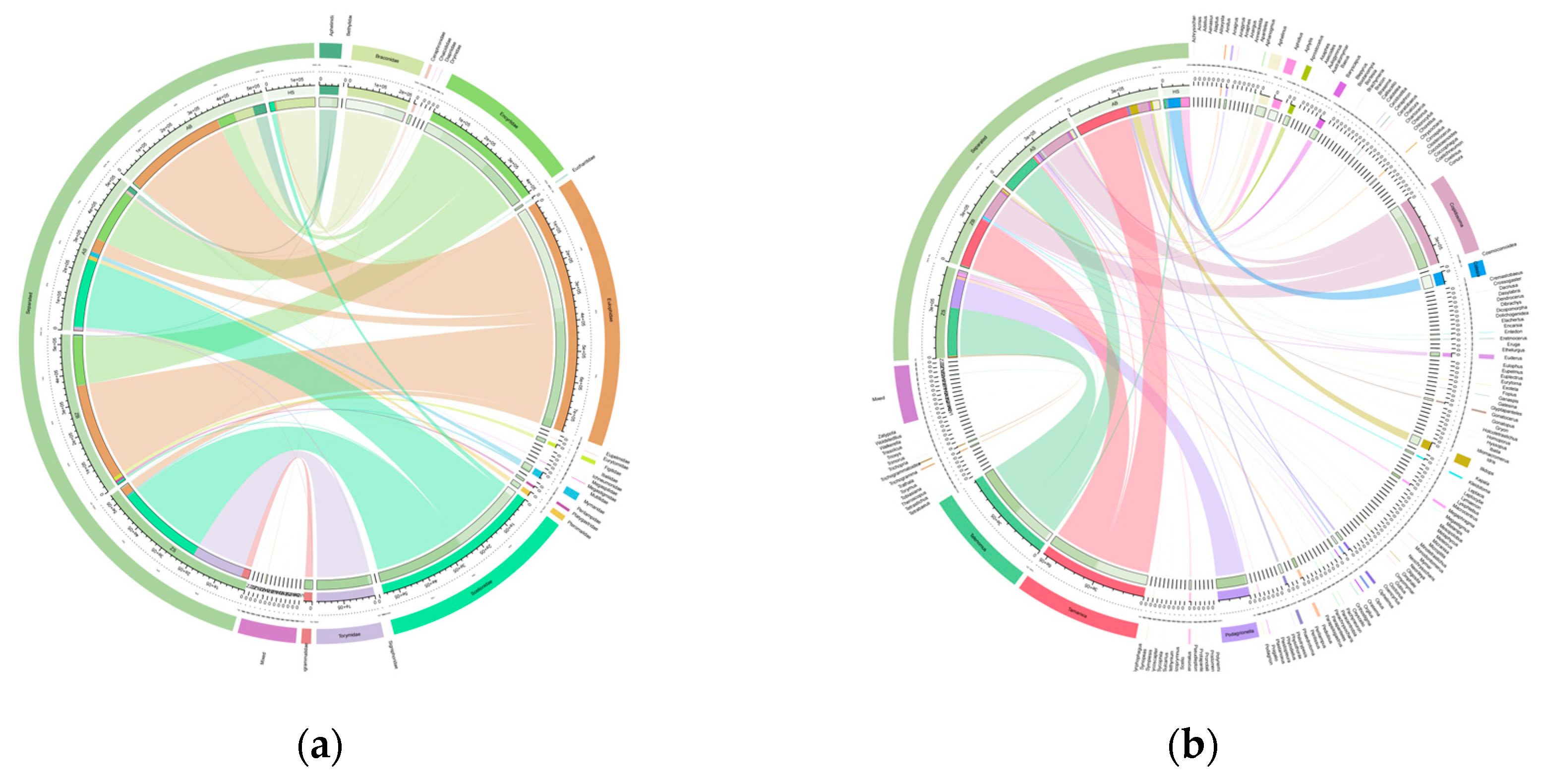

3.2. Species composition analysis

From the ethanol samples, 243783 OTUs were recorded in 9 classes, 35 orders, 320 families, 1358 genera, and 2796 species of arthropods (

Figure 2a). A total of 576 species in 9 orders, 89 families, 243 genera were identified in the tissue samples (

Figure 2b).

Among the ethanol samples, Diptera is the most abundant insect, comprising 48% of all OTUs, followed by Sarcoptiformes (31%), Blattodea (7%), Hymenoptera (4%), and Hemiptera (3%) (

Figure 2a). Diptera also exhibits the highest species richness with 1778 species, while Lepidoptera has 300 species, Coleoptera has 243 species, and Hemiptera has 73 species. Hymenoptera represent the most prevalent taxon among the tissue samples with a frequency of 98%, whereas Diptera and Lepidoptera annotations account for less than one percent (

Figure 2b).

3.3. Group comparison analyses

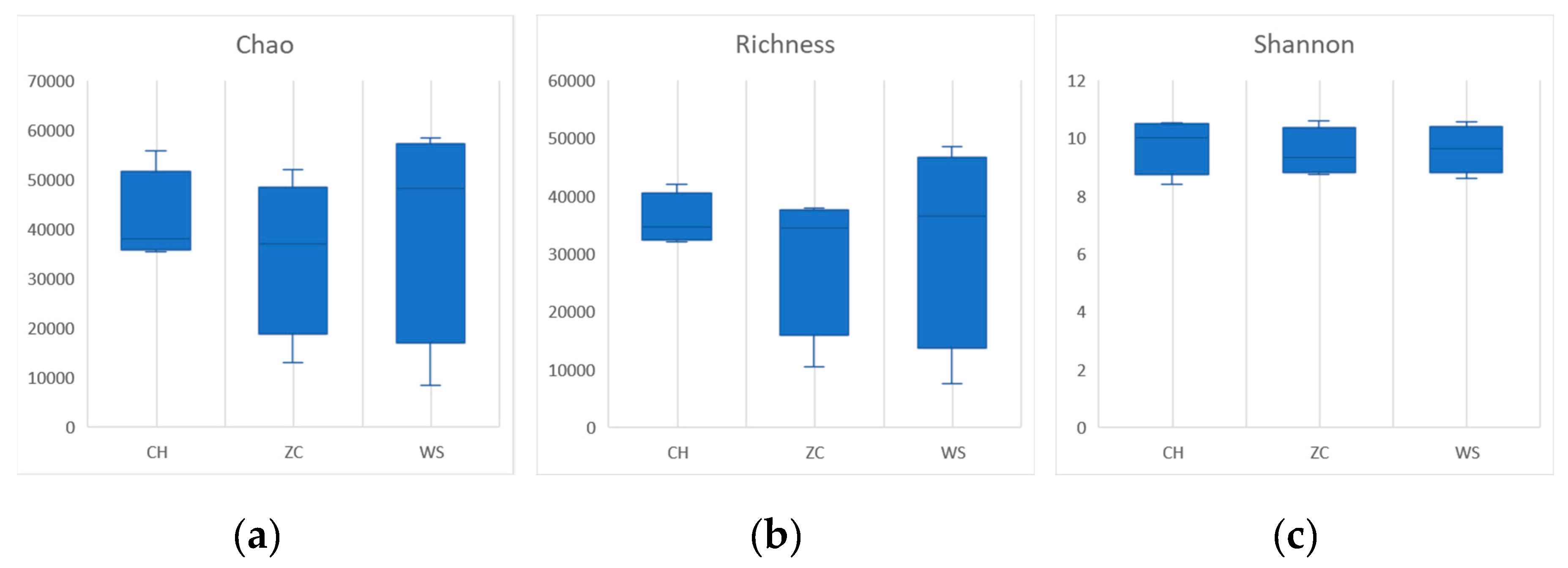

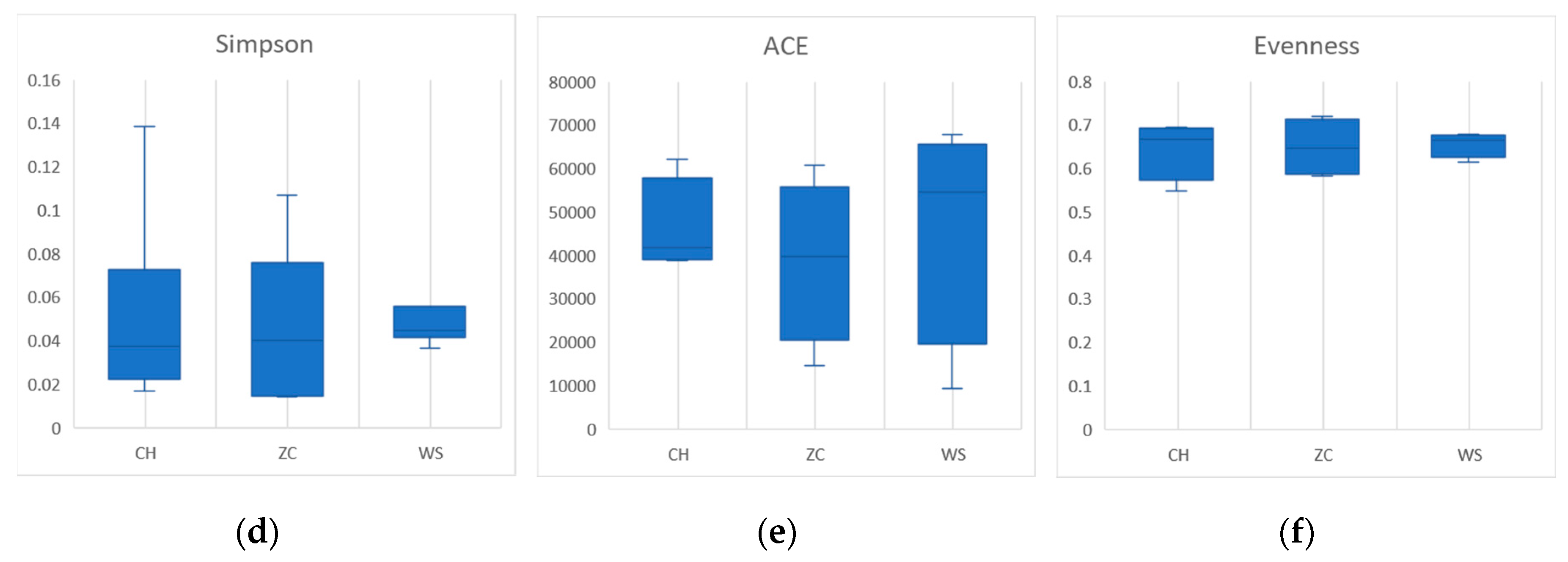

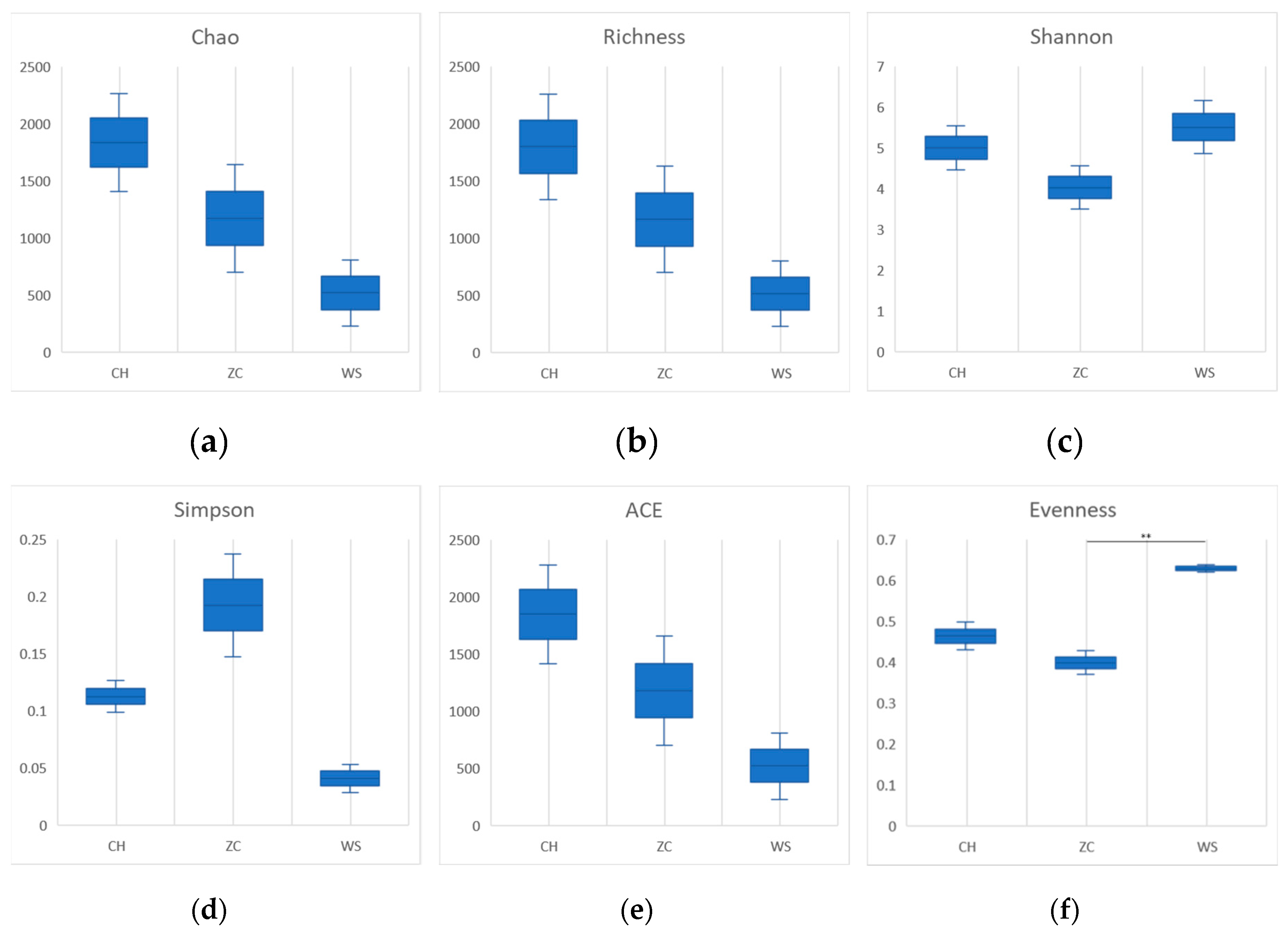

The samples of the two methods were grouped and compared according to the collection site, and the diversity index was calculated by mothur software[

30]. In the ethanol sample, there were no significant differences in species richness, diversity, or evenness(

Figure 3). The community richness calculated by Chao and Richness index of CH was higher than that of the other two groups in tissue samples, and the community diversity calculated by Shannon, Simpson and index is higher in WS (

Figure 4).

3.4. Differences in species diversity of parasitoid wasps noted in the two treatments

All OTUs annotated to the parasitic part of Hymenoptera were selected and grouped according to sample processing method for comparison. A total of 748 OTUs of 7 families and 31 genera of parasitoids were annotated from all the ethanol samples, while 4208 OTUs of 143 genera of 25 families were annotated from the tissue samples. The ethanol samples lost at least 72% of the families (

Figure 5a), 78% of the genera (

Figure 5b) and 82.2% of the OTUs. The species diversity of parasitoids in tissue samples was much higher than that in ethanol samples.

The highest abundance in ethanol sample is Braconidae (69%), followed by Mymaridae (17%), Scelionidae (10%) and other (4%) (

Figure 5a). The most abundant species were Braconidae (16 species), followed by Scelionidae (11 species) and Mymaridae (9 species).

In tissue samples, the highest abundance was Eulophidae (35%), followed by Scelionidae (25%), Encyrtidae (18%), Braconidae (3%), with Mymaridae and Trichogramtidae accounted for 1% (

Figure 5a). There were 92 species belonging to Eulophidae, 79 species belonging to Scelionidae, 63 species belonging to Braconidae, 61 species belonging to Mymaridae, 36 species belonging to Pteromalidae, and 29 species belonging to Trichogramtidae.

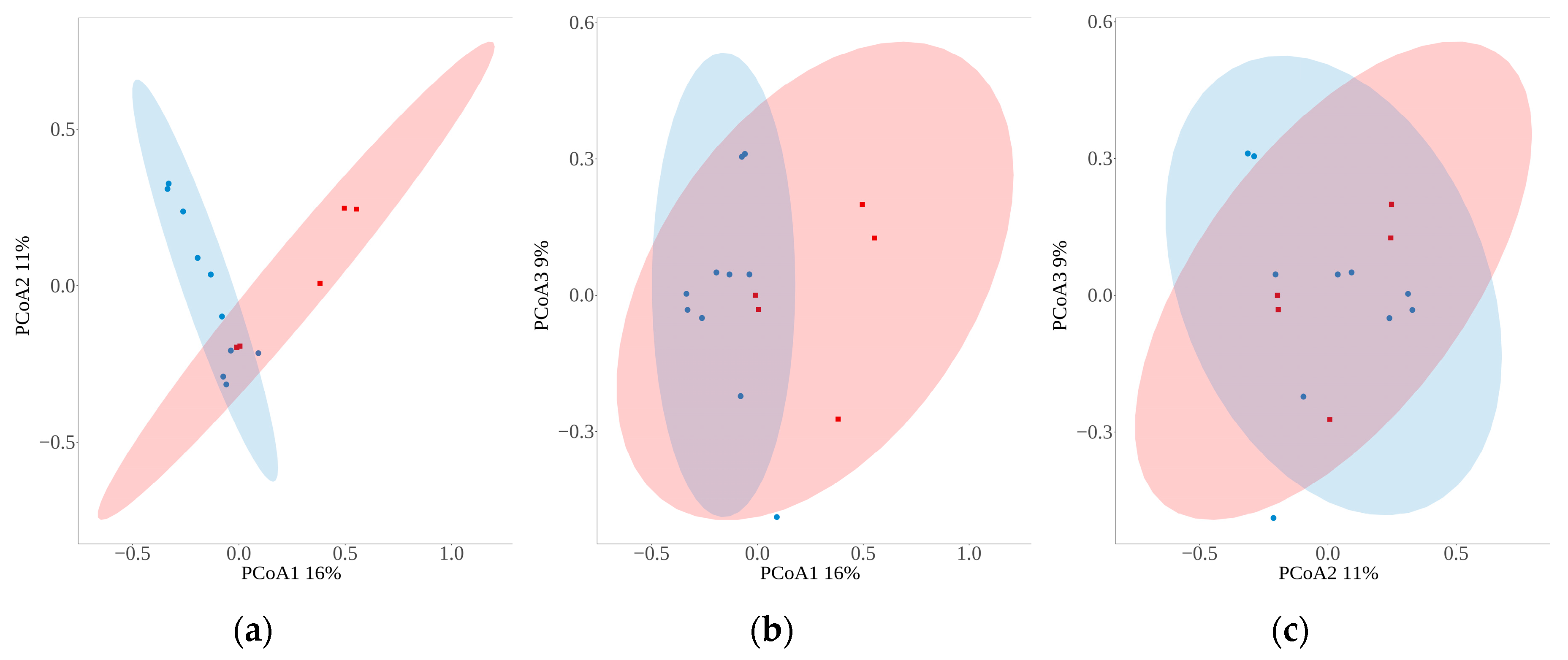

The OTUs abundance table of parasitoid wasps from all sample was analyzed by Principal co-ordinates analysis, the distance between samples was calculated by bray_curtis, and the confidence ellipse was drawn with the confidence level of 0.95(

Figure 6). PC1 can explain 16% of the variation between samples, PC2 can explain 11% of the variation between samples, and PC3 can explain 9% of the variation between samples. The sample confidence ellipses of both groups were not significantly separated, but the projections on different principal components were significantly different, with PC3 separating samples from different locations and PC1 separating samples from different sampling methods.

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity of parasitic wasp communities under different management measures in paddy fields

Based on the second-generation sequencing results obtained from two sampling methods, a total of 4956 OTUs belonging to 174 genera and 32 families of parasitoid wasps were annotated. This number is obviously larger than the previously reported 240 species, indicating that the current estimation of parasitic wasp species diversity in paddy fields is likely underestimated. As there were significant differences in agricultural management practices at the three sites, samples of parasitic wasps from the three sites also showed significant differences (

Figure 4f).

The CH sample site exhibited rich vegetation cover with diverse flowering plants and no insecticide usage, while the WS sample site mainly consisted of cement structures with limited vegetation cover. These findings are consistent with previous multi-site studies conducted in Thailand, China, and Vietnam which demonstrated that planting nectar-producing plants on ridges significantly enhances parasitic wasp diversity within paddy ecosystems [

6,

10,

31]. Additionally, a study conducted in Vietnam revealed that heterogeneity in paddy land cover positively influences functional taxa diversity. A comparison between vegetated zones and unvegetated zones within Philippine paddy fields showed that weed zones and sesame/okra zones provide suitable habitats for parasitoids without resulting in higher pest populations compared to clearance zones [

32]. However, it should be noted that there was no significant difference observed when comparing diversity indices extracted from ethanol samples of three sample lands (

Figure 3), suggesting that sample treatment methods may greatly influence survey results. Therefore, careful selection of appropriate sampling methods is crucial for accurate assessment of biodiversity.

4.2. Limitations of ethanol DNA extraction methods

The results of this study demonstrate that the utilization of a filter for ethanol filtration enables rapid and extensive acquisition of biological information from Malaise trap samples. However, it leads to a reduction in resolution at specific taxonomic levels (

Figure 5). A total of 748 OTUs belonging to 7 families and 31 genera were identified across all combined samples using ethanol extraction method. Comparatively, the grinding tissue method significantly improves sequencing resolution, resulting in the annotation of 4208 OTUs from 143 genera within 25 families. Both the rarefaction curve (

Figure 1a)and the Shannon-Wiener curve (

Figure 1b) indicates sufficient sequencing depth for the entire sample set. It is hypothesized that the low DNA content per insect in the filtration method leads to loss of many non-dominant species during subsequent amplification and sequencing steps. In conclusion, DNA extraction through selective grinding allows researchers to achieve higher overall resolution and obtain more detailed information by targeting specific taxonomic levels within arthropod communities.

The diversity analysis of arthropod samples collected in Richmond Park, Surrey, UK yielded similar results, with only 40% of the species being recovered from ethanol samples compared to 92% from tissue samples [

33]. A comparative study conducted in Stockholm, Sweden, examining the metabarcoding diversity of Malaise trap tissue and ethanol demonstrated significant variations in estimates of community composition [

34]. Furthermore, a recent investigation revealed that ethanol extraction resulted in distinct species compositions when compared to tissue grinding [

28].

4.3. Species annotation and abundance

A total of 248,229 OTUs were annotated in this study, and a lot of new molecular information was obtained. Compared with traditional classification methods and DNA barcoding studies by generation sequencing, the high-throughput sequencing adopted in this study is cheaper and can quickly obtain all DNA barcoding information from samples.

Species annotation: The varying intraspecific variation of barcode sequences within each group, and in some cases, significant variations exist. For instance, certain COI sequences in

Chortoicetes terminifera exhibit an intraspecific difference ranging from 2-6% [

35]. Additionally, Hawaiian

Hylaeus bee species demonstrates intraspecific difference of 4% [

36]. It is important to note that mitochondrial heterogeneity can potentially mislead species identification by clustering sequences from the same species into OTUs and annotating them as distinct species. Consequently, this may lead to an overestimation of species diversity. To ensure accurate classification in macro barcoding studies, it is crucial to rely on a well-curated reference database that associates DNA marker sequences with morphologically verified specimens [

37]. In this study, annotations were made using the NCBI and BOLD databases [

38]. However, it should be noted that the accuracy of some species annotations has declined.

For example, some sequences identified in NCBI are misidentified as closely related species. And some of the results of microbial and human contamination during the experiment were mistakenly uploaded as animal barcode sequences. Some metabarcoding projects directly upload uncorrected and unadulterated comment results to the database, with many contaminated sequences of incorrect annotation; And incomplete annotation: there are many sequences in the database that are annotated only to the higher taxa, such as family name/genus name sp., which are only auxiliary references and cannot identify the species. These problems have also been found in many similar studies [

39,

40], so high-quality barcode databases still need to be improved by a large number of researchers.

Species abundance: In this study, an unnaturally high abundance of

Sarcoptes species was obviously found (

Figure 2), which may be due to the fact that mites parasitizing on other insects fell off, and some mites remained on the filter membrane during the filtration process, resulting in the subsequent DNA extracted by filter membrane containing too many mite samples. The problem of over-classification of microscopic insects has also been mentioned in studies using similar methods [

41], and filtration methods should be optimized to prevent microscopic insects from being retained on filters. In addition, the preference of PCR primers for different class groups may cause the results of macro barcodes to be inconsistent with the reality [

42]. Targeted optimization of primer design is required for amplifying target groups [

43]. Metabarcoding can be convenient to provide DNA information, but to accurately determine the species abundance still need improvement method. PCR-free sequencing may offer a potential solution to address those challenges [

44].

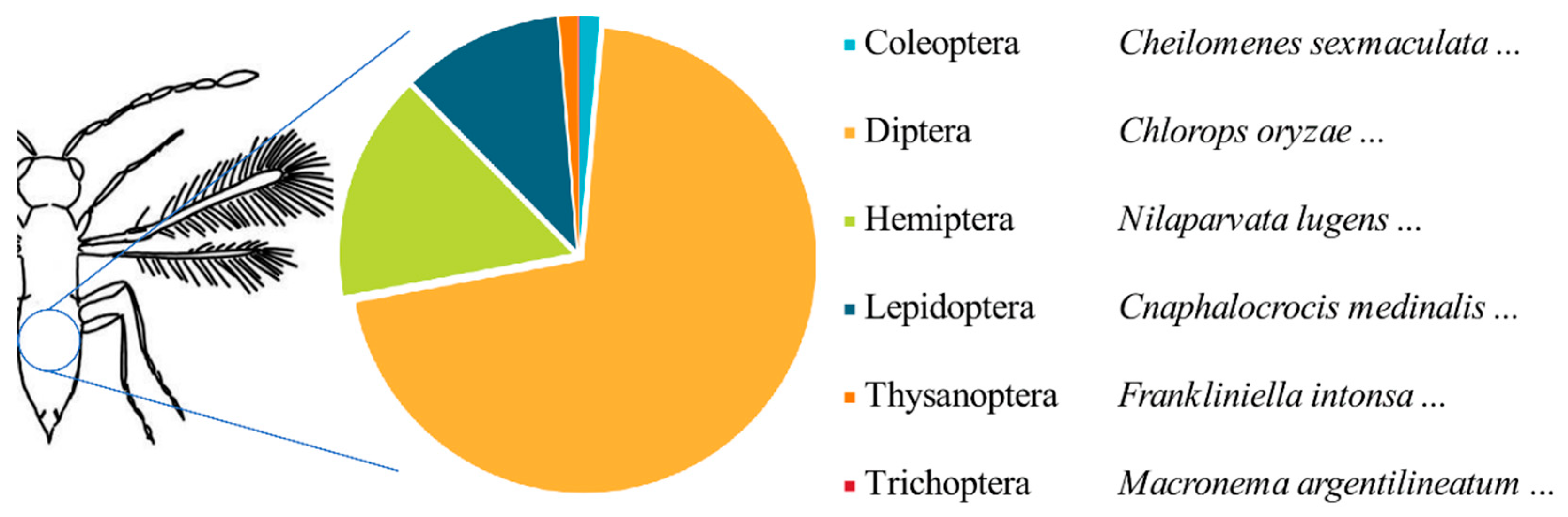

4.4. Potential trophic network of parasitic wasps

DNA in the gut of predators has been extensively documented. High-throughput sequencing methods have revealed the presence of various hexapod insects in spider guts [

45]and detected the dietary composition of ladybugs [

46]. Wilson, Looney et al. (2023) successfully identified prey from

Vespa mandarinia larvae feces [

47], and Berman and Inbar (2022) elucidated interactions between large mammalian herbivores and plant-dwelling arthropods[

48]. Previous studies on nutritional relationships between parasitic wasps and their hosts have primarily focused on species identification using host DNA detection techniques [

49]. By employing molecular detection techniques, Zhu et al. (2019) analyzed the quantitative food web structure of

Aphis spiraecola and its parasitoid on citrus plants[

50].

In this study, several important agricultural pests such as

Cnaphalocrocis medinalis,

Chlorops oryzae,

Nilaparvata lugens, and

Sogatella furcifera were detected from tissue samples of parasitoid wasps (

Figure 7). After manually correcting some annotation results, we were able to eliminate classification errors and sample contamination. Moreover, the occurrence of cross-contamination in samples stored in 95% ethanol is extremely rare [

51], additional insects detected in the parasitoid samples in this study are mainly from parasitoid hosts. This demonstrates the feasibility of identifying host species through DNA analysis of adult parasitoid wasps, in contrast to the commonly used barcoding approach that relies on analyzing host samples to identify their associated parasitic wasps [

52].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we make three mainly conclusions. (i) Based on the second-generation sequencing results obtained from two sampling methods, a total of 4956 OTUs belonging to 174 genera and 32 families of parasitoid wasps were annotated. (ii) The ethanol filter method can efficiently capture a wide range of information diversity. However, it exhibits lower resolution and result in loss of species abundance. Selective selection of insects of a single taxonomic order from the Malaise traps helps to improve the overall resolution. (iii) Using high throughput sequencing from adult parasitoid wasps can be detected by the host information, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of host species and providing novel insights into food web construction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Table S1: Alpha diversity estimates of all samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and Q.Z.; Specimen collection and identification, L.W., L.G., J.L., S.L. and H.W.; soft-ware, L.W., H.W. and W.H.; validation, L.W., H.W., W.H. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, L.W. and H.W.; investigation, L.W., H.W., L.G., J.L. and W.H.; resources, L.W., H.W. and W.H..; data curation, L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W., H.W., W.H. and Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Agricultural Science and Technology Innovative and Promotion Program of Guangdong Province, grant number, 2023KJ113.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study have been deposited in the NCBI. database repository under the following accession numbers: PRJNA1069984.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Dunsong Li from the Plant Protection Research Institute, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, for his invaluable assistance in conducting field surveys. And we would like to express our gratitude to Xiangxiang Jin from the Institute of Zoology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, for her invaluable assistance in insect identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shields, M.W.; Johnson, A.C.; Pandey, S.; Cullen, R.; González-Chang, M.; Wratten, S.D.; Gurr, G.M. History, current situation and challenges for conservation biological control. Biol Control 2019, 131, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Entling, M.H.; Moonen, A.C.; Smith, B.M.; Jeanneret, P. Structure, function and management of semi-natural habitats for conservation biological control: a review of European studies. Pest Manag Sci 2016, 72, 1638–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurr, G.M.; Liu, J.; Read, D.M.Y.; Catindig, J.L.A.; Cheng, J.A.; Lan, L.P.; Heong, K.L. Parasitoids of Asian rice planthopper (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) pests and prospects for enhancing biological control by ecological engineering. Ann Appl Biol 2011, 158, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Desneux, N. Biological control with Trichogramma in China: history, present status, and perspectives. Annual review of entomology 2021, 66, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, T.F.; Tang, B.J.; Wang, B.Y.; Wang, L.Y.; Liu, J.B.; Zhou, Q. Transcriptome analysis and molecular characterization of soluble chemical communication proteins in the parasitoid wasp Anagrus nilaparvatae (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae). Ecol Evol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurr, G.M.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Xu, H.; Zhu, P.; Chen, G.; Yao, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Catindig, J.L.; et al. Multi-country evidence that crop diversification promotes ecological intensification of agriculture. Nat Plants 2016, 2, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drechsler, M.; Settele, J. Predator-prey interactions in rice ecosystems: effects of guild composition, trophic relationships, and land use changes - a model study exemplified for Philippine rice terraces. Ecol Model 2001, 137, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominik, C.; Seppelt, R.; Horgan, F.G.; Settele, J.; Vaclavik, T. Landscape heterogeneity filters functional traits of rice arthropods in tropical agroecosystems. Ecol Appl 2022, 32, e2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, F.G.; Crisol Martinez, E.; Stuart, A.M.; Bernal, C.C.; de Cima Martin, E.; Almazan, M.L.P.; Ramal, A.F. Effects of vegetation strips, fertilizer levels and varietal resistance on the integrated management of Arthropod biodiversity in a tropical rice ecosystem. Insects 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, C.; Gianuca, A.T.; Schweiger, O.; Franzén, M.; Settele, J. Pesticides and land cover heterogeneity affect functional group and taxonomic diversity of arthropods in rice agroecosystems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshana, T.S.; Lee, M.B.; Ascher, J.S.; Qiu, L.; Goodale, E. Crop heterogeneity is positively associated with beneficial insect diversity in subtropical farmlands. J Appl Ecol 2021, 58, 2747–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenly, K.G.; Barrion, A.T. Designing standardized and optimized surveys to assess invertebrate biodiversity in tropical irrigated rice using structured inventory and species richness models. Environ Entomol 2016, 45, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhang, Q.L.; Liu, Q.S.; Meissle, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Hua, H.X.; Chen, X.P.; Peng, Y.F.; Romeis, J. Rice in China - focusing the nontarget risk assessment. Plant Biotechnol J 2017, 15, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; We, Q. .; Li, B.; He, Y.T.; Wan, P.J.; Lai, F.X.; Wang, W.X.; Yu, W.J.; et al. Community structure and diversity of wasps which parasitize hemipteran pests in the rice-growing region of southern China. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology 2022, 59, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Triapitsyn, S.V.; Rugman-Jones, P.F.; Tretiakov, P.S.; Shih, H.T.; Huang, S.H. New synonymies in the Anagrus incarnatus Haliday 'species complex' (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae) including a common parasitoid of economically important planthopper (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) pests of rice in Asia. J Nat Hist 2018, 52, 2795–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijerathna, T.; Gunathilaka, N. Morphological identification keys for adults of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Sri Lanka. Parasite Vector 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.C.; Ulrich, W.; Segerer, A.H.; Greifenstein, T.; Knubben, J.; Morinière, J.; Bozicevic, V.; Günter, A.; Hausmann, A. Insect diversity in heterogeneous agro-environments of Central Europe. Biodivers Conserv 2023, 32, 4665–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, A.J.; Adams, S.A.; Gillespie, R.G. Invasion by an ecosystem engineer changes biotic interactions between native and non-native taxa. Ecol Evol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Frati, F.; Andrew, B.; Bernie, C.; Hong, L. Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, C.; Wemheuer, F.; Beaurepaire, A.; Daniel, R.; Erler, S.; Vidal, S. Preliminary investigation of species diversity of rice hopper parasitoids in southeast Asia. Insects 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, A.M.; Batovska, J.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Weiss, J.; Cunningham, J.P.; Rodoni, B.C.; Blacket, M.J. Prospects and challenges of implementing DNA metabarcoding for high-throughput insect surveillance. Gigascience 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.Q.; Ashton, L.; Pedley, S.M.; Edwards, D.P.; Tang, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Kitching, R.; Dolman, P.M.; Woodcock, P.; Edwards, F.A.; et al. Reliable, verifiable and efficient monitoring of biodiversity via metabarcoding. Ecol Lett 2013, 16, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Shokralla, S.; Porter, T.M.; King, I.; van Konynenburg, S.; Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W.; Hajibabaei, M. Simultaneous assessment of the macrobiome and microbiome in a bulk sample of tropical arthropods through DNA metasystematics. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 8007–8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajibabaei, M.; Spall, J.L.; Shokralla, S.; van Konynenburg, S. Assessing biodiversity of a freshwater benthic macroinvertebrate community through non-destructive environmental barcoding of DNA from preservative ethanol. Bmc Ecol 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdozain, M.; Thompson, D.G.; Porter, T.M.; Kidd, K.A.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Sibley, P.K.; Swystun, T.; Chartrand, D.; Hajibabaei, M. Metabarcoding of storage ethanol vs. conventional morphometric identification in relation to the use of stream macroinvertebrates as ecological indicators in forest management. Ecol Indic 2019, 101, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.P.; Kabir, M.M.M.; Haque, S.S.; Afrin, S.; Ahmed, N.; Pittendrigh, B.; Qin, X.H. Surrounding landscape influences the abundance of insect predators in rice field. Bmc Zool 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.N.; Chiu, M.C.; Jaung, L.M.; Lu, Y.J.; Lin, H.J. Effects of farming systems on insect communities in the paddy fields of a simplified landscape during a pest-control intervention. Zool Stud 2021, 60, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirse, A.; Bourlat, S.J.; Langen, K.; Zapke, B.; Zizka, V.M.A. Comparison of destructive and nondestructive DNA extraction methods for the metabarcoding of arthropod bulk samples. Mol Ecol Resour 2023, 23, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leray, M.; Yang, J.Y.; Meyer, C.P.; Mills, S.C.; Agudelo, N.; Ranwez, V.; Boehm, J.T.; Machida, R.J. A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity: application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Front Zool 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Gevers, D.; Westcott, S.L. Reducing the effects of pcr amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16s rrna-based studies. Plos One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, F.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G.; Lu, Z.; Johnson, A.C.; Gurr, G.M. Quantifying the respective and additive effects of nectar plant crop borders and withholding insecticides on biological control of pests in subtropical rice. J Pest Sci 2018, 91, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, F.G.; Martinez, E.C.; Stuart, A.M.; Bernal, C.C.; Martin, E.D.; Almazan, M.L.P.; Ramal, A.F. Effects of vegetation strips, fertilizer levels and varietal resistance on the integrated management of arthropod biodiversity in a tropical rice ecosystem. Insects 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linard, B.; Arribas, P.; Andújar, C.; Crampton-Platt, A.; Vogler, A.P. Lessons from genome skimming of arthropod-preserving ethanol. Mol Ecol Resour 2016, 16, 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquina, D.; Esparza-Salas, R.; Roslin, T.; Ronquist, F. Establishing arthropod community composition using metabarcoding: Surprising inconsistencies between soil samples and preservative ethanol and homogenate from Malaise trap catches. Mol Ecol Resour 2019, 19, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier, K.; Chapuis, M.P.; Moosavi, S.M.; Tohidi-Esfahani, D.; Sword, G.A. Nuclear insertions and heteroplasmy of mitochondrial DNA as two sources of intra-individual genomic variation in grasshoppers. Syst Entomol 2011, 36, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnacca, K.N.; Brown, M.J.F. Tissue segregation of mitochondrial haplotypes in heteroplasmic Hawaiian bees: implications for DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol Resour 2010, 10, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boykin, L.M.; Armstrong, K.; Kubatko, L.; De Barro, P. DNA barcoding invasive insects: database roadblocks. Invertebr Syst 2012, 26, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The barcode of life data system (www.barcodinglife.org). Mol Ecol Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioduchowska, M.; Czyz, M.J.; Goldyn, B.; Kur, J.; Sell, J. Instances of erroneous DNA barcoding of metazoan invertebrates: Are universal cox1 gene primers too "universal" ? Plos One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, T.M.; Hajibabaei, M. Scaling up: A guide to high-throughput genomic approaches for biodiversity analysis. Mol Ecol 2018, 27, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, M.M.; Specht, A.; Fonseca, V.G. Assessing insect biodiversity with automatic light traps in Brazil: Pearls and pitfalls of metabarcoding samples in preservative ethanol. Ecol Evol 2020, 10, 2352–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluczyk, M.; Weiss, J.; Links, M.G.; Aranguren, M.E.; Wilkinson, M.D.; Egea-Cortines, M. Quantitative evaluation of bias in PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing derived from metabarcoding samples. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.J.; Soubrier, J.; Weyrich, L.S.; Cooper, A. Environmental metabarcodes for insects: PCR reveals potential for taxonomic bias. Mol Ecol Resour 2014, 14, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Yang, Q.; Su, X.; Zhou, L.L.; Tang, M.; Fu, R.B.; Li, J.G.; Huang, Q.F. Ultra-deep sequencing enables high-fidelity recovery of biodiversity for bulk arthropod samples without PCR amplification. Gigascience 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toju, H.; Baba, Y.G. DNA metabarcoding of spiders, insects, and springtails for exploring potential linkage between above- and below-ground food webs. Zool Lett 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.N.; Bukhman, Y.V.; Jusino, M.A.; Scully, E.D.; Spiesman, B.J.; Gratton, C. Using high-throughput amplicon sequencing to determine diet of generalist lady beetles in agricultural landscapes. Biol Control 2022, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Looney, C.; Tembrock, L.R.; Dickerson, S.; Orr, J.; Gilligan, T.M.; Wildung, M. Insights into the prey of Vespa mandarinia (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in Washington state, obtained from metabarcoding of larval feces. Front Insect Sci 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, T.S.; Inbar, M. Revealing cryptic interactions between large mammalian herbivores and plant-dwelling arthropods via DNA metabarcoding. Ecology 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Marco, F.; Urbaneja, A.; Jaques, J.A.; Rugman-Jones, P.F.; Stouthamer, R.; Tena, A. Untangling the aphid-parasitoid food web in citrus: Can hyperparasitoids disrupt biological control? Biol Control 2015, 81, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.L.; Yang, F.; Yao, Z.W.; Wu, Y.K.; Liu, B.; Yuan, H.B.; Lu, Y.H. A molecular detection approach for a cotton aphid-parasitoid complex in northern China. Sci Rep-Uk 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, K.J.; Chapman, E.G.; Harwood, J.D. A tale of two fluids: does storing specimens together in liquid preservative cause DNA cross-contamination in molecular gut-content studies? Entomol Exp Appl 2017, 163, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varennes, Y.D.; Boyer, S.; Wratten, S.D. Un-nesting DNA Russian dolls - the potential for constructing food webs using residual DNA in empty aphid mummies. Mol Ecol 2014, 23, 3925–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).