1. Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukemia in Western countries and is characterized by the clonal accumulation of mature CD5⁺ B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and secondary lymphoid organs [

1]. Early studies emphasized that CLL pathogenesis is strongly shaped by chronic antigenic stimulation and by B-cell receptor (BCR) biology, which plays a central role in determining leukemic cell survival and clonal evolution [

2,

3,

4]. Subsequent work further redefined CLL as a dynamic disease in which measurable leukemic cell turnover and continuous trafficking between lymphoid tissues and peripheral blood, rather than passive accumulation alone, contribute to disease progression [

5,

6]. Although many patients experience an indolent clinical course and may not require therapy for years, a significant subset exhibits aggressive disease requiring early treatment. This marked clinical heterogeneity reflects both intrinsic features of leukemic clones and extrinsic signals provided by the tumor microenvironment, which is pivotal for sustaining survival, activation, and proliferation of CLL cells [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

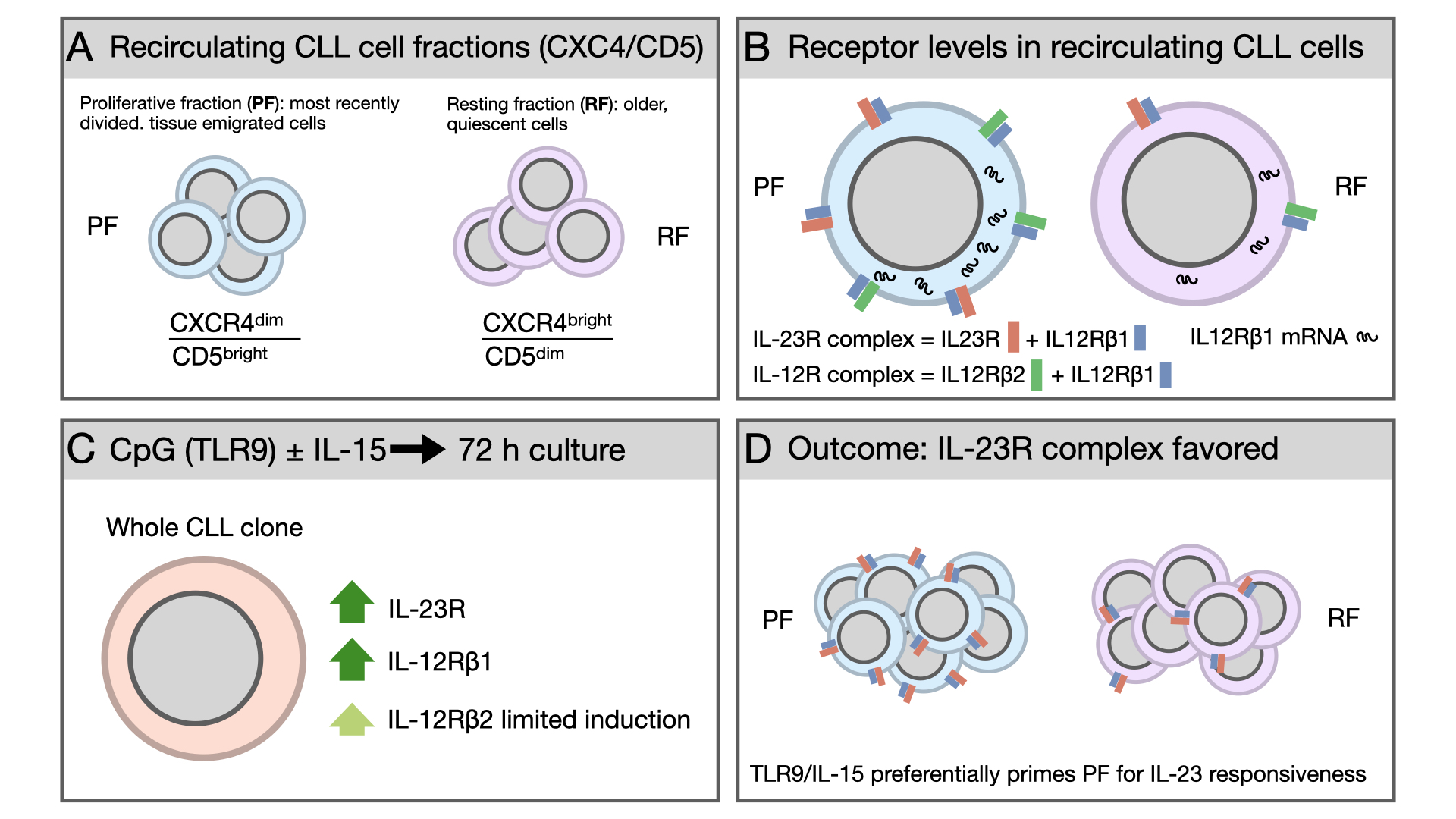

Beyond interpatient variability, CLL displays marked intraclonal heterogeneity. The leukemic population comprises subfractions with distinct proliferative histories and biological properties [

12]. A well-established framework to dissect this complexity relies on the reciprocal surface expression of CD5 and the chemokine receptor CXCR4, which identifies CLL subpopulations differing by time since last division. CXCR4^dim/CD5^bright cells represent the most recently divided, tissue-emigrated cells (proliferative fraction, PF), whereas CXCR4^bright/CD5^dim cells correspond to older, quiescent cells (resting fraction, RF). Intermediate fractions reflect transitional stages in this trafficking cycle [

13]. These subpopulations differ not only phenotypically but also functionally, displaying distinct transcriptional programs, telomere length, activation markers, and sensitivity to microenvironment-derived signals. Importantly, the CXCR4^dim/CD5^bright fraction is enriched for cells recently stimulated in proliferation centers within lymph nodes, suggesting heightened susceptibility to additional activating signals upon re-entry into supportive niches.

Among microenvironmental mediators influencing CLL biology, cytokines of the interleukin-12 (IL-12) family play key roles in immune regulation and inflammation [

14]. IL-12 signals through a heterodimeric receptor composed of the IL-12Rβ1 and IL-12Rβ2 subunits, whereas IL-23 signals via a receptor consisting of IL-12Rβ1 paired with IL-23R [

15,

16]. Functionally, IL-12 typically promotes Th1 differentiation and cytotoxic immune responses [

17], whereas IL-23 supports Th17 polarization, bridges innate and adaptive immunity and sustains chronic inflammatory responses [

18].

In normal B-cell physiology, expression of the IL-23 receptor complex has been detected in early B lymphocytes, germinal center B cells, and plasma cells, but is usually expressed at low or undetectable levels in mature circulating B cells [

19]. In malignant contexts, IL-23R/IL-23 biology has been investigated in childhood B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-cell lymphomas, and in plasma-cell neoplasia [

20,

21,

22].

In CLL, our group previously showed that circulating leukemic cells frequently exhibit an incomplete IL-23 receptor phenotype, characterized by IL-23R expression in the absence of IL-12Rβ1. CD40/CD40L interactions provided by activated T cells can induce expression of the complete IL-23 receptor complex, enabling responsiveness to IL-23 and supporting autocrine/paracrine signaling loops [

23]. Importantly, these events occur independently of BCR engagement, underscoring the relevance of non–antigen-driven microenvironmental signals in shaping cytokine responsiveness. In contrast, IL-12 has been associated with growth-inhibitory and tumor-suppressive effects. Genetic IL-12Rβ2 deficiency predisposes murine models to autoimmunity and spontaneous lymphoid malignancies, highlighting a protective role for IL-12 signaling in lymphoid homeostasis [

24]. Consistently, reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression has been reported in several hematologic malignancies, suggesting selective pressure against intact IL-12 signaling during tumor evolution [

20,

21,

22].

Despite these insights, the distribution of IL-12 family receptor subunits across intraclonal CLL subfractions remains poorly defined. Specifically, it is unclear whether most recently divided, tissue-emigrated cells differ from older, quiescent cells in the co-expression of receptor subunits defining the IL-23 and/or IL-12 receptor complexes, and whether this contributes to intraclonal specialization. We therefore examined IL-12 family receptor subunit expression and co-expression in recirculating CLL cells ex vivo and after antigen-independent stimulation.

2. Results

2.1. The Proliferative Fraction Shows Higher Expression of IL-23R and IL-12R Receptor Complexes in Recirculating CLL Cells

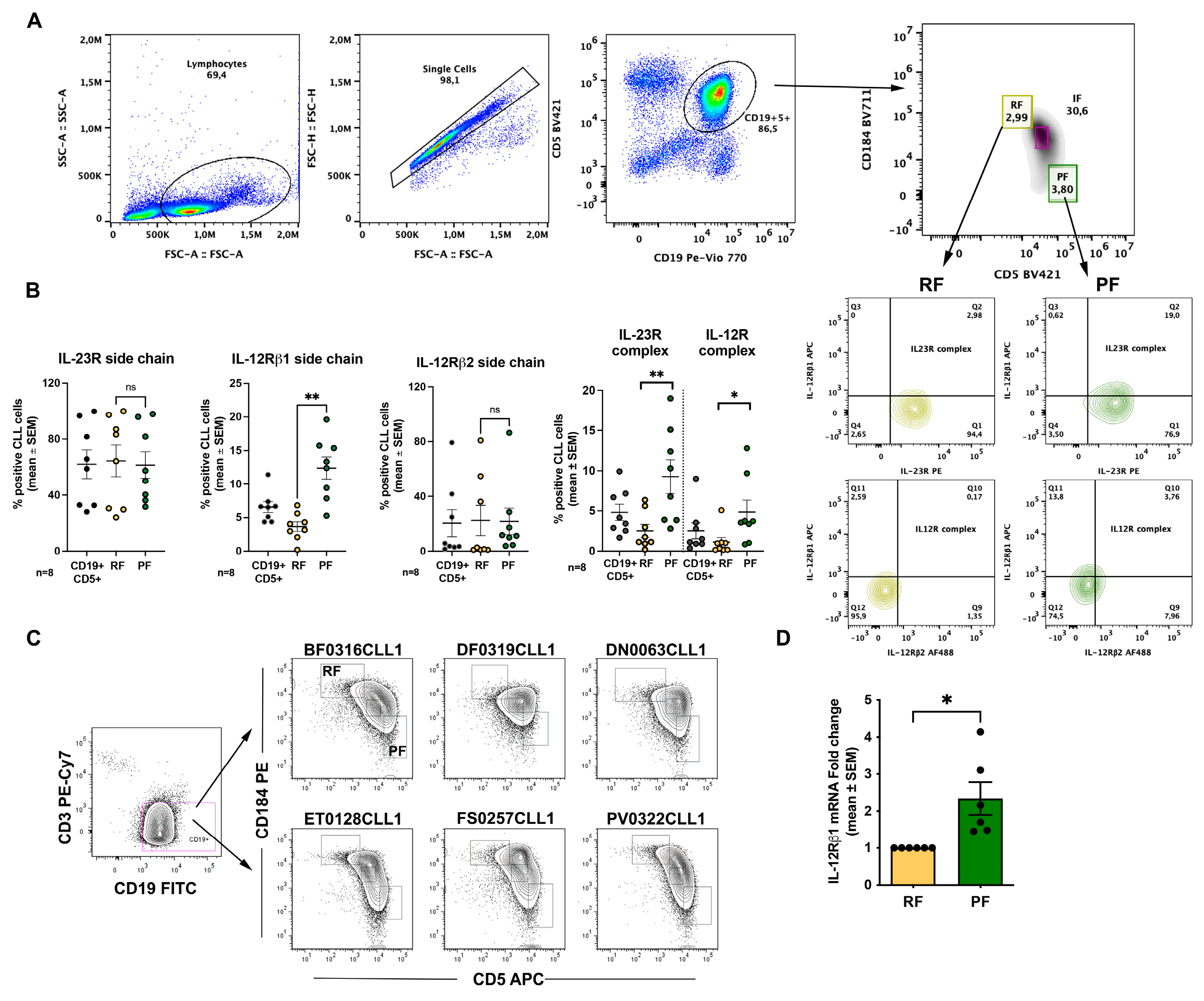

We first analyzed expression of the IL-23R and IL-12R receptor complexes across phenotypically distinct CLL fractions defined according to Calissano et al. [

13] (see also Introduction). In our flow-cytometry analyses, data are presented as the percentage of positive cells; however, in this experimental setting this readout also provides an indirect proxy for changes in mean fluorescence intensity, because shifts in signal intensity translate into changes in the fraction of events exceeding the positivity threshold. Thus, receptor complexes were quantified as double-positive populations for the relevant subunits (IL-23R⁺IL-12Rβ1⁺ for the IL-23R complex and IL-12Rβ1⁺IL-12Rβ2⁺ for the IL-12R complex). The gating strategy used to identify these fractions by flow cytometry is shown in

Figure 1A. For analysis of IL-23R and IL-12R expression, we focused on RF and PF.

When analyzing individual receptor subunits, we observed a significant difference between RF (3.7 ± 0.7% mean and SEM) and PF (12.4 ± 1.7% mean and SEM) only for IL-12Rβ1 (

Figure 1B). However, when receptor complexes were considered, PF displayed a higher percentage of cells co-expressing the IL-23R complex (2.5± 0.8% vs 9.3± 2% mean and SEM) and the IL-12R complex (1.1± 0.6% vs 4.8± 1.5%). Given the higher representation of IL-12Rβ1 at the cell surface, we evaluated IL-12Rβ1 mRNA levels by RT-qPCR in sorted RF and PF populations. Consistent with the flow cytometry data, this analysis confirmed higher IL-12Rβ1 expression in PF (

Figure 1C,D).

Figure 1.

IL-23R and IL-12R expression in ex vivo CLL cells. A. Gating strategy used to identify lymphocytes, single cells, CD19⁺ CLL cells, and to discriminate proliferative fraction (PF) and resting fraction (RF); B. Surface expression of IL-23R, IL-12Rβ1, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunits in ex vivo CLL cells, shown for CD19⁺ PF and RF populations; C. Representative flow cytometry plots showing sorting of PF and RF populations from six CLL samples according to the gates indicated; D. IL-12Rβ1 mRNA expression in sorted RF and PF cells, measured by RT-qPCR. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

Figure 1.

IL-23R and IL-12R expression in ex vivo CLL cells. A. Gating strategy used to identify lymphocytes, single cells, CD19⁺ CLL cells, and to discriminate proliferative fraction (PF) and resting fraction (RF); B. Surface expression of IL-23R, IL-12Rβ1, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunits in ex vivo CLL cells, shown for CD19⁺ PF and RF populations; C. Representative flow cytometry plots showing sorting of PF and RF populations from six CLL samples according to the gates indicated; D. IL-12Rβ1 mRNA expression in sorted RF and PF cells, measured by RT-qPCR. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

2.2. CpG + IL-15 Stimulation Induces IL-23R and IL-12R Receptor Complexes in CLL Cells

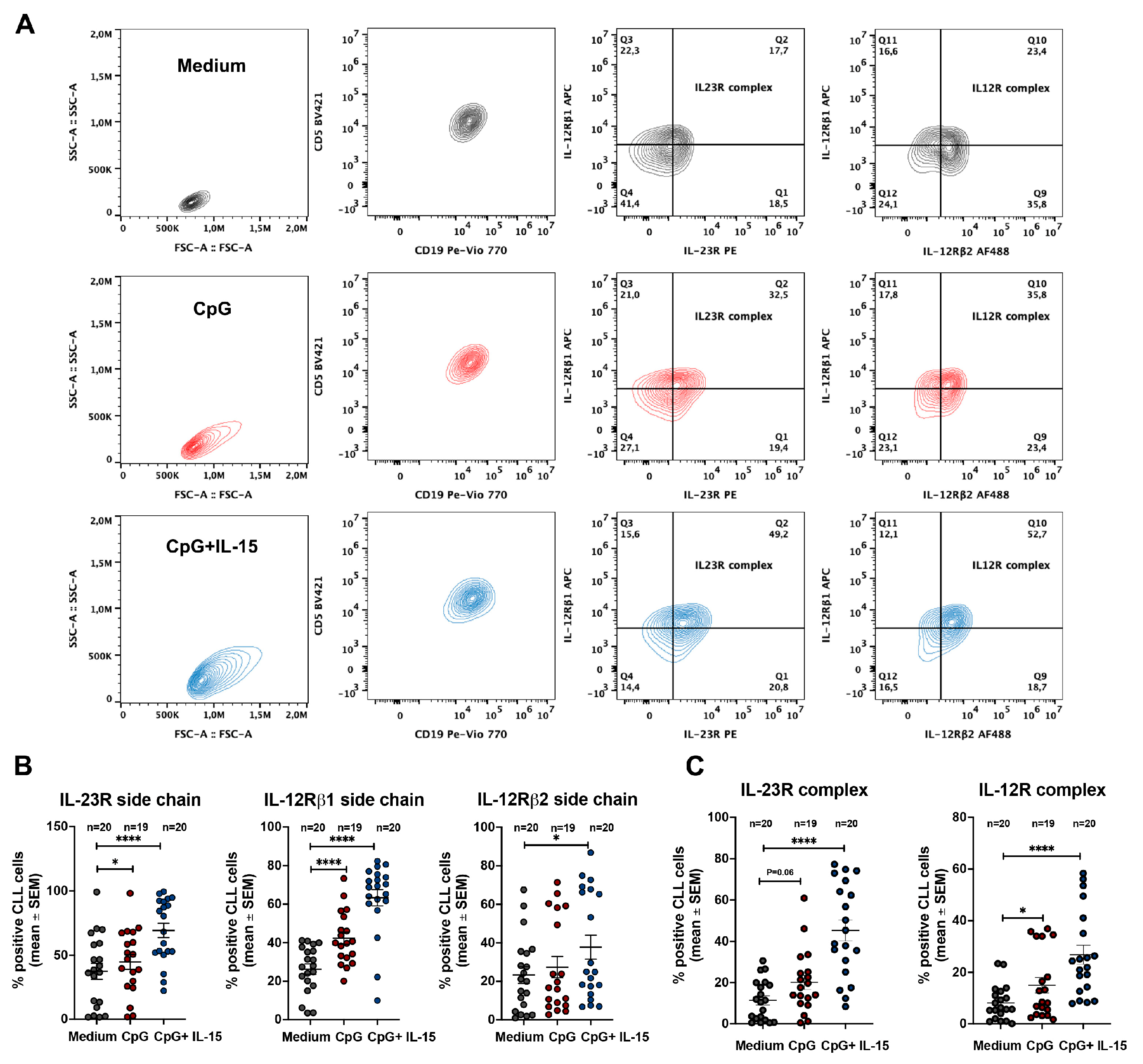

We next investigated whether expression of the IL-23R complex and the IL-12R complex could be induced in CLL cells following TLR9 activation.

Figure 1B shows that, in line with previous observations [

23], the IL-23R complex was detectable only in a low percentage of unstimulated ex vivo CLL cells. At the whole-clone level, the IL-12R complex was generally expressed in a relatively low percentage of cells, with few exceptions, primarily due to limited expression of the IL-12Rβ2 subunit (

Figure 1B).

To activate leukemic B cells, purified CLL cells were cultured for 72 h with CpG alone or in combination with IL-15, a cytokine known to synergize with CpG in promoting CLL cell survival and proliferation [

25]. CpG + IL-15 was generally more efficient in inducing a significant upregulation of IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1 surface expression. In contrast, IL-12Rβ2 upregulation was detected only in a minority of samples (

Figure 2B) and did not yield a significant overall increase.

After 72 h of stimulation, both receptor complexes were detectable; however, IL-23R complex expression was consistently detected in a higher percentage of CLL cells than the IL-12R complex (

Figure 2C). This preferential induction of the IL-23R complex largely reflected the limited induction of the IL-12Rβ2 subunit. Nevertheless, IL-12R complex expression was higher in CpG + IL-15–stimulated CLL cells than in unstimulated cells.

Figure 2.

IL-23R and IL-12R expression in CLL cells after incubation with CpG and CpG + IL-15 for 72 h. A. Representative flow-cytometry gating strategy used to identify CLL cells and to assess IL-23R and IL-12R complex expression under the indicated culture conditions (medium alone, CpG, or CpG + IL-15) after 72 h; B. Percentage of CLL cells expressing the IL-23R receptor subunit, IL-12Rβ1 receptor subunit, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunit following 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions; C. Percentage of CLL cells expressing the IL-23R complex and the IL-12R complex following 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

Figure 2.

IL-23R and IL-12R expression in CLL cells after incubation with CpG and CpG + IL-15 for 72 h. A. Representative flow-cytometry gating strategy used to identify CLL cells and to assess IL-23R and IL-12R complex expression under the indicated culture conditions (medium alone, CpG, or CpG + IL-15) after 72 h; B. Percentage of CLL cells expressing the IL-23R receptor subunit, IL-12Rβ1 receptor subunit, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunit following 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions; C. Percentage of CLL cells expressing the IL-23R complex and the IL-12R complex following 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

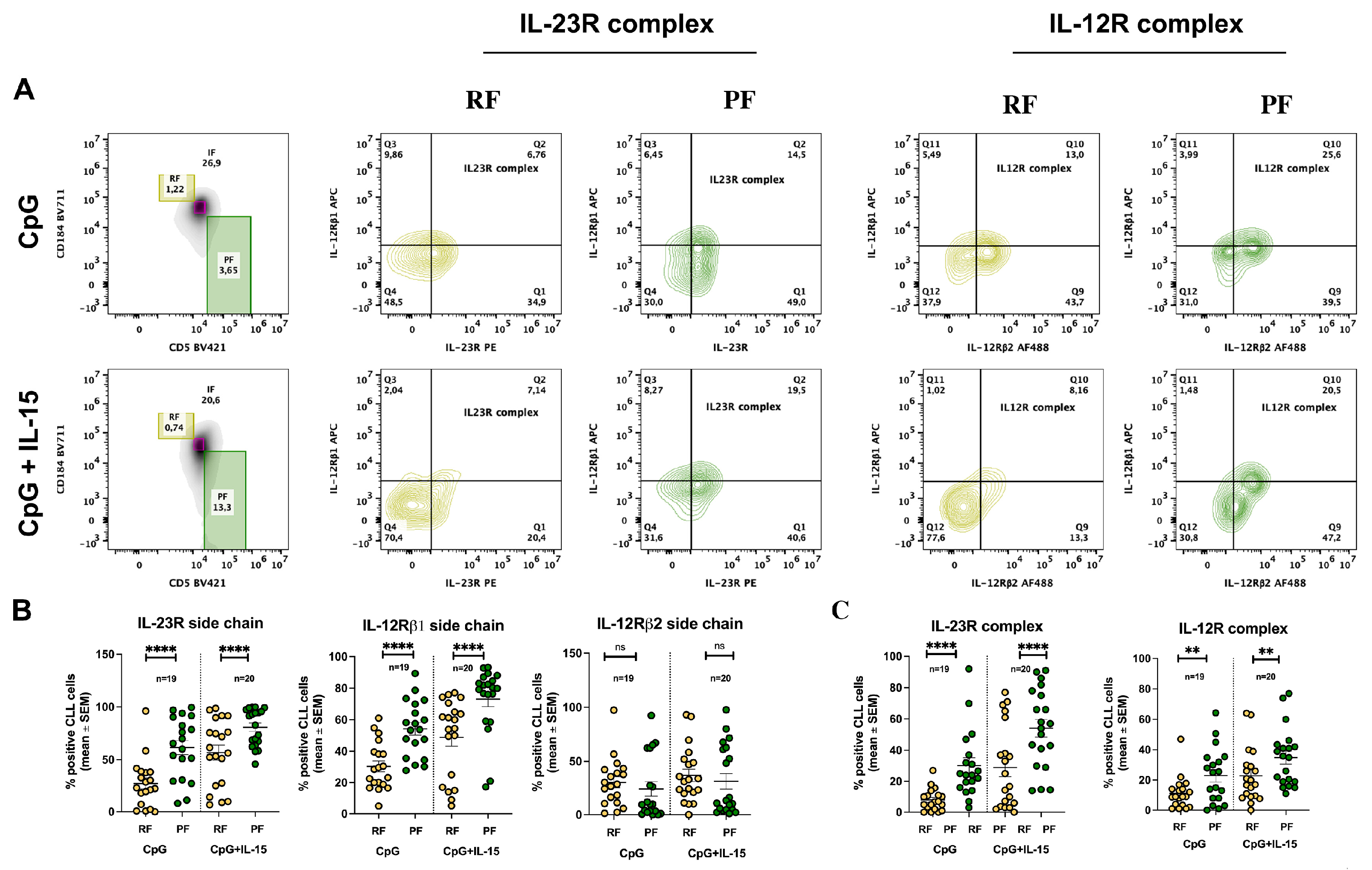

2.3. CpG + IL-15 Stimulation Differentially Upregulates IL-23R and IL-12R Receptor Subunits in Resting and Proliferative Fractions

We then assessed whether cells expressing IL-23R and IL-12R complexes differed between RF and PF following CpG + IL-15 stimulation. The gating strategy used to identify these fractions is shown in

Figure 3A and overlaps with that applied to ex vivo CLL cells. Using this approach, IL-23R and IL-12R receptor subunit expression was analyzed in RF and PF after 72 h of stimulation.

The percentage of IL-12Rβ1-positive cells increased in both fractions but remained consistently higher in PF. IL-12Rβ2 expression remained largely unchanged across fractions, showing only a modest increase in RF. In contrast, IL-23R expression was markedly induced by stimulation in both RF and PF, with a significantly higher percentage of IL-23R⁺ cells detected in PF compared with RF (

Figure 3B).

Analysis of the complete receptor complexes further supported these findings. IL-12R complex expression did not differ significantly between RF and PF under control, CpG, or CpG + IL-15 conditions. By contrast, IL-23R complex expression was significantly higher in PF compared with RF following CpG + IL-15 stimulation (

Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Differential expression of IL-23R and IL-12R in CLL RF and PF subsets after stimulation with CpG and CpG+IL-15. A. Representative flow-cytometry gating strategy used to identify CLL cells and to distinguish RF and PF subsets, followed by assessment of IL-23R and IL-12R complex expression after 72 h incubation with CpG or CpG + IL-15; B. Percentage of RF and PF CLL cells expressing the IL-23R receptor subunit, IL-12Rβ1 receptor subunit, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunit after 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions; C. Percentage of RF and PF CLL cells expressing the IL-23R complex and the IL-12R complex after 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions. Each symbol represents an individual CLL sample; horizontal bars indicate mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Differential expression of IL-23R and IL-12R in CLL RF and PF subsets after stimulation with CpG and CpG+IL-15. A. Representative flow-cytometry gating strategy used to identify CLL cells and to distinguish RF and PF subsets, followed by assessment of IL-23R and IL-12R complex expression after 72 h incubation with CpG or CpG + IL-15; B. Percentage of RF and PF CLL cells expressing the IL-23R receptor subunit, IL-12Rβ1 receptor subunit, and IL-12Rβ2 receptor subunit after 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions; C. Percentage of RF and PF CLL cells expressing the IL-23R complex and the IL-12R complex after 72 h incubation under the indicated conditions. Each symbol represents an individual CLL sample; horizontal bars indicate mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the difference is evaluated using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p 0.05; **p 0.01; ***p 0.001; ****p 0.0001.

3. Discussion

This study investigated the expression of IL-23R, IL-12Rβ1, and IL-12Rβ2 in recirculating CLL cells and in intraclonal subfractions defined by CD5 and CXCR4 co-expression (

Figure 1A). We also assessed whether expression of these receptors could be modulated by antigen-independent stimulation (CpG alone or CpG + IL-15). Analyses were performed on whole CLL cell populations and within CD5/CXCR4-defined subfractions. We focused primarily on RF and PF, as these fractions are best characterized and were the most informative in our dataset. Thus, the intermediate fraction was not included in representative figures (data not shown).

IL-12 family receptor expression was heterogeneous across CD5/CXCR4-defined intraclonal subfractions. Notably, IL-12Rβ1 was detected in a significantly higher percentage of PF cells (

Figure 1B), and RT-qPCR analysis in sorted RF and PF confirmed higher IL-12Rβ1 mRNA levels in PF (

Figure 1C,D). Consistent with these findings, PF also displayed a higher proportion of cells co-expressing the IL-23R and IL-12R receptor complexes compared with RF (

Figure 1B). Overall, these data indicate that IL-12Rβ1 availability is a key determinant of IL-23R and IL-12R complex assembly within recirculating CLL cells, and that its enrichment in PF may contribute to a phenotype more permissive to cytokine-driven clonal expansion.

We further show that stimulation with CpG + IL-15 induces IL-12 family receptor components (

Figure 2B). After 72 h of in vitro exposure, surface IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1 increased markedly, whereas IL-12Rβ2 remained largely unchanged (

Figure 2B). This pattern resulted in a robust increase in the IL-23R receptor complex and a more limited increase in the IL-12R receptor complex (

Figure 2C), consistent with a cytokine-responsiveness profile skewed toward IL-23.

When receptor expression was evaluated in the context of CD5/CXCR4-defined intraclonal heterogeneity, both RF (CXCR4^bright/CD5^dim) and PF (CXCR4^dim/CD5^bright) displayed increased IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1 surface expression following stimulation (

Figure 3B). However, the proportion of IL-23R complex–positive cells was higher in PF than in RF (

Figure 3C). These findings suggest that the potential for IL-23 responsiveness is higher in PF-phenotype CLL cells (most recently divided, tissue-emigrated cells), as reflected by their higher proportion of IL-23R-expressing cells, whereas RF cells (older, quiescent cells) displayed a significantly lower proportion of IL-23R-expressing cells.

It is noteworthy that the most consistent induction of IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1 occurred in the presence of IL-15. In our setting, CpG alone was generally less effective at inducing significant changes in IL-23R/IL-12Rβ1 expression. This is in line with the concept that IL-15 can prevent CpG/TLR9-associated apoptosis and allow significant CLL clonal expansion [

25], consistent with PF representing a fraction with higher proliferative competence. Beyond its known anti-apoptotic effects, IL-15 may also contribute to remodeling the cytokine receptor landscape of CLL cells, potentially facilitating preferential assembly of the IL-23 receptor complex in proliferative fraction cells.

The asymmetric distribution of IL-23R across intraclonal subfractions has several biological implications. First, it supports the concept that PF cells, enriched in most recently divided, tissue-emigrated cells, are particularly receptive to microenvironment-derived cytokine cues and may exploit IL-23 signaling to support expansion and survival within proliferation centers. Second, CpG/IL-15 stimulation effectively induced IL-23R complex expression (IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1) in CLL clones, and this induction was more pronounced in PF-phenotype cells.

A further relevant observation is the persistently limited induction of IL-12Rβ2 in response to CpG/IL-15 stimulation. Although recirculating CLL clones showed variable baseline IL-12Rβ2 expression, PF generally displayed a lower proportion of IL-12R complex-positive cells than IL-23R complex-positive cells, particularly after CpG/IL-15 stimulation (

Figure 3C). In this setting, the limited inducibility of IL-12Rβ2 emerges as a defining constraint on IL-12 receptor complex formation, while permitting preferential engagement of IL-23-associated pathways. Of note, IL-12Rβ2 availability has been reported to influence IL-12 responsiveness in other B-cell malignancies, and IL-12 family cytokine axes can be differentially configured across lymphoproliferative settings [

21,

22]. Beyond limiting IL-12 responsiveness, reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression has also been mechanistically linked to leukemogenesis: in murine models, genetic deficiency of IL-12Rβ2 predisposes to autoimmunity and spontaneous development of lymphoid malignancies, supporting a tumor-suppressive role for IL-12 signaling [

24]. Thus, failure to adequately upregulate IL-12Rβ2 may constrain IL-12 signaling and contribute to a permissive context for leukemic persistence and progression, whereas robust induction of IL-23R supports a shift toward pro-survival, pro-inflammatory pathways. Overall, this imbalance between IL-12 and IL-23 signaling may contribute to intraclonal specialization and to the selection of subclones favoring survival and expansion.

Together, these findings support a model in which intraclonal heterogeneity in CLL is associated with a functional bias toward IL-23 responsiveness, selectively enriched in recently divided, tissue-emigrated cells with a proliferative fraction phenotype.

From a therapeutic standpoint, our findings suggest two complementary avenues. First, targeting the IL-23/IL-23R axis may disrupt pro-survival and proliferative signaling that is preferentially enriched in PF-phenotype cells. In support of this concept, we previously reported that neutralizing IL-23 can restrain disease in CLL xenograft models [

23,

26]. Second, approaches aimed at restoring or enhancing IL-12Rβ2 expression and signaling could re-establish tumor-suppressive IL-12 functions, counteracting the leukemogenic predisposition associated with IL-12Rβ2 deficiency. The balance between impaired IL-12Rβ2-mediated restraint and enhanced IL-23R-driven activation may therefore represent a key pathogenic mechanism in CLL biology, and future interventions could be designed to shift this equilibrium toward an anti-leukemic immune environment.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. CLL Cell Samples

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Northwell Health and was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. CLL patients were diagnosed as recommended, and all subjects provided written informed consent at enrollment. In addition, part of the experiments was conducted using peripheral blood samples from newly diagnosed patients with Binet stage A CLL enrolled in the O-CLL1 protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00917540) [

27,

28]. A total of 27 CLL patients were included in this study (see

Table S1). All patients were treatment-naïve at the time of sample collection. Not all samples were used for every experimental assay due to cell number limitations; the number of patients analyzed in each experiment is indicated in the corresponding figure legends.

4.2. CLL Cell Isolation

CLL cells from each patient’s PB were isolated by negative selection using RosetteSep Human B Cell Enrichment Cocktail (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Whole PB was incubated with the enrichment cocktail, then diluted with 2% FBS in PBS and centrifuged over RosetteSep DM-L Density Medium (STEMCELL Technologies). Purity was assessed by the Center for CLL Research. Cells were resuspended in freezing solution and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. Samples containing ≥95% leukemic cells were considered eligible for the study.

4.3. CLL Cell Culture and Stimulation

Thawed CLL cells were seeded in an enriched medium used for long-term culture of normal B cells, supplemented with insulin/transferrin/selenium (Cat. #17-838Z; Lonza). Notably, this medium contains 2-ME (5 × 10−5 M), which supports cystine-to-cysteine reduction and thereby facilitates cysteine availability for glutathione synthesis required for retained viability. Fresh medium was prepared for each experiment using stock additives. Cultures were established in 96-well round-bottom plates at 4 × 10^5 cells per 200 µL, with duplicates for each condition. Recombinant human IL-15 (PeproTech Inc.) and CpG DNA TLR9 ligand (ODN-2006; InvivoGen) were added to final concentrations of 15 ng/mL and 0.2 µM (1.5 µg/mL), respectively, and cultures were incubated for 72 h. Features of the CLL samples used are reported in

Table S1.

4.4. Flow Cytometry: Cytokine Receptor Detection in Bulk CLL Cells

Live cells were identified using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Stains for flow cytometry (LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain Kit or Far-Red Dead Cell Stain Kit; Life Technologies). For surface membrane immunofluorescence, cells (2 × 10^5) in FACS buffer (PBS + 10% bovine serum albumin + 1% sodium azide) were incubated with primary antibodies for 20 min at 4 °C, followed by fixation with 0.1% formaldehyde in PBS. Isotype controls were processed in parallel. The following monoclonal antibodies were used: IL-23R (Cat. #FAB140019-100, R&D Systems), IL-12Rβ1 (Cat. #565043, BD Horizon), and IL-12Rβ2 (Cat. #FAB1959C, R&D Systems). Data were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer using the HTS plate reader and analyzed using FlowJo v10.6.2.

4.5. Flow Cytometry: Identification of RF/PF/IF and Receptor Detection in Intraclonal Fractions

PBMCs were thawed and stained for CXCR4 APC (Cat. #306510, BioLegend), CD5 PE-Cy7 (Cat. #300622, BioLegend), and CD19 Pacific Blue (Cat. #48-0199-42, eBioscience). For staining, cells (2 × 10^5) in FACS buffer (PBS + 10% bovine serum albumin + 1% sodium azide) were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C and fixed with 0.1% formaldehyde in PBS. This staining enabled identification of three fractions: PF (CXCR4^dim/CD5^bright), RF (CXCR4^bright/CD5^dim), and IF (CXCR4^int/CD5^int). Within each fraction, expression of IL-23R, IL-12Rβ1, and IL-12Rβ2 was assessed as described above.

4.6. RT-qPCR for Detection of IL-12Rβ1 RNA

Total RNA was extracted from sorted cell populations using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (QIAGEN, cat. no. 79306) and purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, cat. no. 74104). RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. A total of 50 ng RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified in a single reaction using the Reliance One-Step Multiplex RT-qPCR Supermix kit (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 12010220). Gene expression was assessed using TaqMan assays specific for human IL-12RB1 (Bio-Rad, qHsaCEP0057499) and HPRT1 (Bio-Rad, qHsaCIP0030549), used as the reference (housekeeping) gene. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the ΔCt method and normalized to HPRT1.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.3.1). Comparisons between resting and proliferative fractions within the same patient were performed using paired non-parametric tests (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). For multiple comparisons, correction was applied when indicated. Data are presented as median values with interquartile ranges unless otherwise specified. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Features of CLL samples used in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ma.C., Fr. F., A.N.M., M.C., M.F., G.C. F.M., M.G., E.A., F.G., A.I., V.C., F.F. and A.N.; Methodology, D.R, F.F., Ma.C.; Formal Analysis, D.R., Ma.C., G.C., E.N.; Investigation, Ma.C., R.M., M.C.C., G.C., N.B., F.F.; Data Curation, Ma.C., G.C., E.N., F.F.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Fr. F., Ma.C., G.C..; Writing – Review & Editing, A.N.M., G.C., V.C., Ma.C., F.M., M.F.; Visualization, F.G.; Supervision, M.C., Ma.C., Fr.F, M.F. G.C.; Funding Acquisition, G.C., Fr.F., E.A., E.N. M.C., N.B., A.N. A.N.M.

Funding

This research was supported by Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) Grant 5 × mille ID.9980, (M.F., A.N. and F.M.); AIRC I.G. ID.1426 (to M.F.), ID.15426 (to F.F.); Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie-Linfomi e Mieloma (AIL, Cosenza, to F.F.); Gilead fellowship program 2016 (M.C.) and 2017 (G.C.); Italian Ministry of Health 5 × 1000 funds 2014 (to G.C.), 2015 (to F.F.), 2016 (to F.F. and G.C.), 2020 (to G.C.), 2021 (to N.B.); Italian Ministry of Health RF-2021-12374376 (to E.A. and G.C.); by Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2024–2026 to F.F); 5X1000 Policlinico San Martino # 5M-2023-23687130 (to E.N.); Guido Berlucchi Foundation and Umberto Veronesi Foundation (to A.N.M.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of each Institution participating in the O-CLL1 Multicenter observational trial “Prospective Collection of Biological Data of Prognostic Relevance in Patients with B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia” (clinicaltrials.govidentifier NCT00917540) as mentioned in the Acknowledgments section. Specifically, the Ethics committee of the National Institute for Cancer Research-IST of Genoa-Italy (now called IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino) approved the study on 04/16/2007 with no. OMC007.002 for the centralized laboratory that processed and stored all the CLL samples for the subsequent biological studies. Since July 2020, the study for the Regional Ethics Committee has been identified as N. CER Liguria id 10115. The VIVO-CLL protocol “Caratterizzazione dei meccanismi patogenetici della Leucemia Linfatica Cronica (CLL) mediante studi in vitro ed in vivo: una ricerca per identificare nuovi fattori predittivi e target terapeutici” was approved by the Ethics committee of IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino on 03/04/2023 and for the Regional Ethics Committee is identified as N. CER Liguria 106/2023—DB id 13024.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

Generative AI (ChatGPT 5.2) was used to assist with English-language editing (grammar, clarity, and terminology harmonization) and to support reference formatting and renumbering. All changes were reviewed and validated by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

BCR, B-cell receptor; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CpG, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides; FBS, fetal bovine serum; IF, intermediate fraction; IL, interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PB, peripheral blood; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PF, proliferative fraction; RF, resting fraction; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TLR9, Toll-like receptor 9; 2-ME, 2-mercaptoethanol, SEM, standard error of the mean; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; APC = allophycocyanin; PE-Cy7 = phycoerythrin-cyanine 7; OD, oligodeoxynucleotide; HTS, high-throughput sampler.

References

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, Hillmen P, Keating M, Montserrat E, Chiorazzi N, Stilgenbauer S, Rai KR, Byrd JC, Eichhorst B, O’Brien S, Robak T, Seymour JF, Kipps TJ. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood 2018, 131, 2745–2760. [CrossRef]

- Chiorazzi, N.; Ferrarini, M. B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 841–894. [CrossRef]

- Chiorazzi, N.; Rai, K.R.; Ferrarini, M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 804–815. [CrossRef]

- Bagnara, D.; Mazzarello, A.N.; Ghiotto, F.; Colombo, M.; Cutrona, G.; Fais, F.; Ferrarini, M. Old and New Facts and Speculations on the Role of the B Cell Receptor in the Origin of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14249. [CrossRef]

- Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Kudalkar P, Cesar D, Murphy EJ, Koduru P, Ferrarini M, Zupo S, Cutrona G, Damle RN, Wasil T, Rai KR, Hellerstein MK, Chiorazzi N. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 755–764. [CrossRef]

- Burger JA, Li KW, Keating MJ, Sivina M, Amer AM, Garg N, Ferrajoli A, Huang X, Kantarjian H, Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Hellerstein MK, Turner SM, Emson CL, Chen SS, Yan XJ, Wodarz D, Chiorazzi N. Leukemia cell proliferation and death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients on therapy with the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e89904. [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A.; Ghia, P.; Rosenwald, A.; Caligaris-Cappio, F. The microenvironment in mature B-cell malignancies: a target for new treatment strategies. Blood 2009, 114, 3367–3375. [CrossRef]

- Ghia, P.; Chiorazzi, N.; Stamatopoulos, K. Microenvironmental influences in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: the role of antigen stimulation. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 264, 549–562. [CrossRef]

- Herishanu Y, Pérez-Galán P, Liu D, Biancotto A, Pittaluga S, Vire B, Gibellini F, Njuguna N, Lee E, Stennett L, Raghavachari N, Liu P, McCoy JP, Raffeld M, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan C, Sherry R, Arthur DC, Maric I, White T, Marti GE, Munson P, Wilson WH, Wiestner A. The lymph node microenvironment promotes B-cell receptor signaling, NF-κB activation, and tumor proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 563–574. [CrossRef]

- Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, Croce CM, Packham G, Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Gribben J, Rai K. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 16096. [CrossRef]

- Herndon TM, Chen SS, Saba NS, Valdez J, Emson C, Gatmaitan M, Tian X, Hughes TE, Sun C, Arthur DC, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM, Niemann CU, Marti GE, Aue G, Soto S, Farooqui MZH, Herman SEM, Chiorazzi N, Wiestner A. Direct in vivo evidence for increased proliferation of CLL cells in lymph nodes compared to bone marrow and peripheral blood. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1340–1347. [CrossRef]

- Calissano C, Damle RN, Hayes G, Murphy EJ, Hellerstein MK, Moreno C, Sison C, Kaufman MS, Kolitz JE, Allen SL, Rai KR, Chiorazzi N. In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 3059–3066. [CrossRef]

- Calissano, C.; Damle, R.N.; Marsilio, S.; Yan, X.-J.; Yancopoulos, S.; Hayes, G.; Emson, C.; Murphy, E.J.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Sison, C.; Kaufman, M.S.; Kolitz, J.E.; Allen, S.L.; Rai, K.R.; Ivanovic, I.; Dozmorov, I.M.; Roa, S.; Scharff, M.D.; Li, W.; Chiorazzi, N. Intraclonal complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Fractions enriched in recently born/divided and older/quiescent cells. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 1374–1382. [CrossRef]

- Trinchieri, G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 133–146. [CrossRef]

- 15 Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K, Zonin F, Vaisberg E, Churakova T, Liu M, Gorman D, Wagner J, Zurawski S, Liu Y, Abrams JS, Moore KW, Rennick D, de Waal-Malefyt R, Hannum C, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity 2000, 13, 715–725. [CrossRef]

- Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, To W, Wagner J, O’Farrell AM, McClanahan T, Zurawski S, Hannum C, Gorman D, Rennick DM, Kastelein RA, de Waal Malefyt R, Moore KW. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rβ1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 5699–5708. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.J.; Sullivan, B.M.; Peng, S.L.; Glimcher, L.H. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 713–758. [CrossRef]

- Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Mezghiche, H.; Yahia-Cherbal, H.; Rogge, L.; Bianchi, D. Interleukin-23 receptor: Expression and regulation in immune cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 54, e2250348. [CrossRef]

- Cocco C, Canale S, Frasson C, Di Carlo E, Ognio E, Ribatti D, Prigione I, Basso G, Airoldi I. Interleukin-23 acts as antitumor agent on childhood B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood 2010, 116, 3887–3898. [CrossRef]

- Pistoia V, Cocco C, Airoldi I. Interleukin-12 receptor beta2: from cytokine receptor to gatekeeper gene in human B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Oct 1;27(28):4809-16. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani N, Airoldi I. Novel insights into the role of interleukin-27 and interleukin-23 in human malignant and normal plasma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Nov 15;17(22):6963-70. [CrossRef]

- Cutrona G, Tripodo C, Matis S, Recchia AG, Massucco C, Fabbi M, Colombo M, Emionite L, Sangaletti S, Gulino A, Reverberi D, Massara R, Boccardo S, de Totero D, Salvi S, Cilli M, Pellicanò M, Manzoni M, Fabris S, Airoldi I, Valdora F, Ferrini S, Gentile M, Vigna E, Bossio S, De Stefano L, Palummo A, Iaquinta G, Cardillo M, Zupo S, Cerruti G, Ibatici A, Neri A, Fais F, Ferrarini M, Morabito F. Microenvironmental regulation of the IL-23R/IL-23 axis overrides chronic lymphocytic leukemia indolence. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Feb 14;10(428):eaal1571. [CrossRef]

- Airoldi I, Di Carlo E, Cocco C, Sorrentino C, Fais F, Cilli M, D’Antuono T, Colombo MP, Pistoia V. Lack of Il12rb2 signaling predisposes to spontaneous autoimmunity and malignancy. Blood. 2005 Dec 1;106(12):3846-53. [CrossRef]

- Mongini PK, Gupta R, Boyle E, Nieto J, Lee H, Stein J, Bandovic J, Stankovic T, Barrientos J, Kolitz JE, Allen SL, Rai K, Chu CC, Chiorazzi N. Toll-like receptor 9 and interleukin-15 promote CLL B-cell survival and proliferation: implications for disease progression. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Matis S, Grazia Recchia A, Colombo M, Cardillo M, Fabbi M, Todoerti K, Bossio S, Fabris S, Cancila V, Massara R, Reverberi D, Emionite L, Cilli M, Cerruti G, Salvi S, Bet P, Pigozzi S, Fiocca R, Ibatici A, Angelucci E, Gentile M, Monti P, Menichini P, Fronza G, Torricelli F, Ciarrocchi A, Neri A, Fais F, Tripodo C, Morabito F, Ferrarini M, Cutrona G. MiR-146b-5p regulates IL-23 receptor complex expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood Adv. 2022 Oct 25;6(20):5593-5612. [CrossRef]

- Molica, S.; Giannarelli, D.; Mirabelli, R.; Levato, L.; Gentile, M.; Lentini, M.; Morabito, F. Changes in the incidence, pattern of presentation and clinical outcome of early chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients using the 2008 International Workshop on CLL guidelines. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2014, 7, 691–695. [CrossRef]

- Monti, P.; Menichini, P.; Speciale, A.; Cutrona, G.; Fais, F.; Taiana, E.; Neri, A.; Bomben, R.; Gentile, M.; Gattei, V.; Ferrarini, M.; Morabito, F.; Fronza, G. Heterogeneity of TP53 Mutations and P53 Protein Residual Function in Cancer: Does It Matter? Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 593383. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).