Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

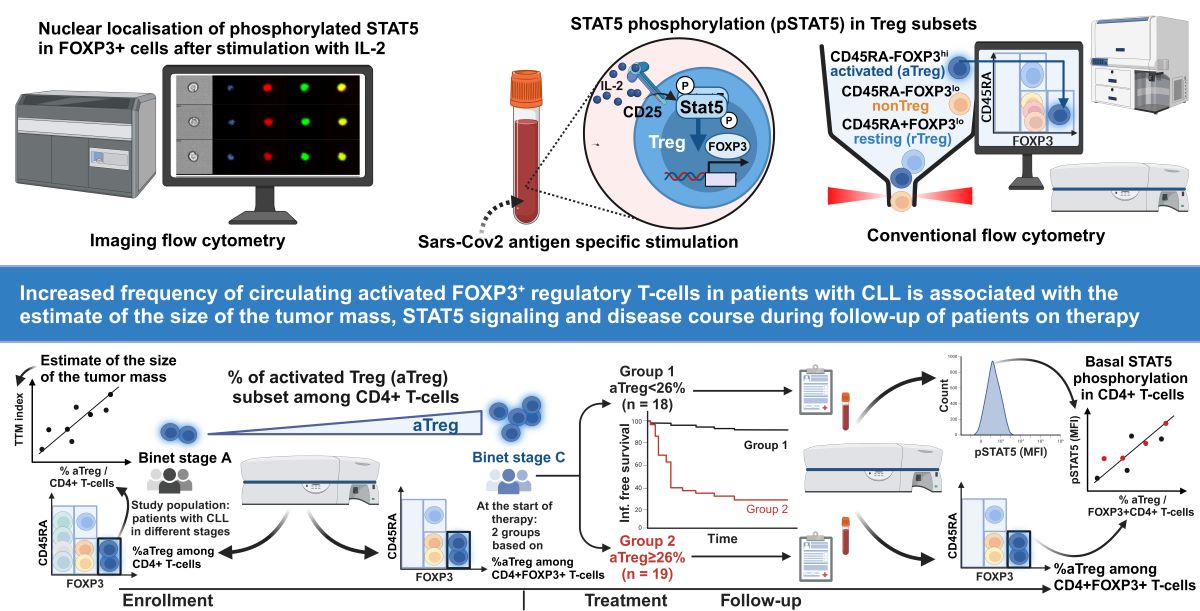

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Preparation of Whole Blood Samples for Analysis of STAT5 Phosphorylation

2.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis after Staining with Antibodies Specific to T-Cell Subsets and Phosphorylated STAT5 Tyrosine

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis of pSTAT5 in Treg Subsets after Whole Blood Stimulation with SARS-CoV2-Specific Antigens

2.5. Imaging Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

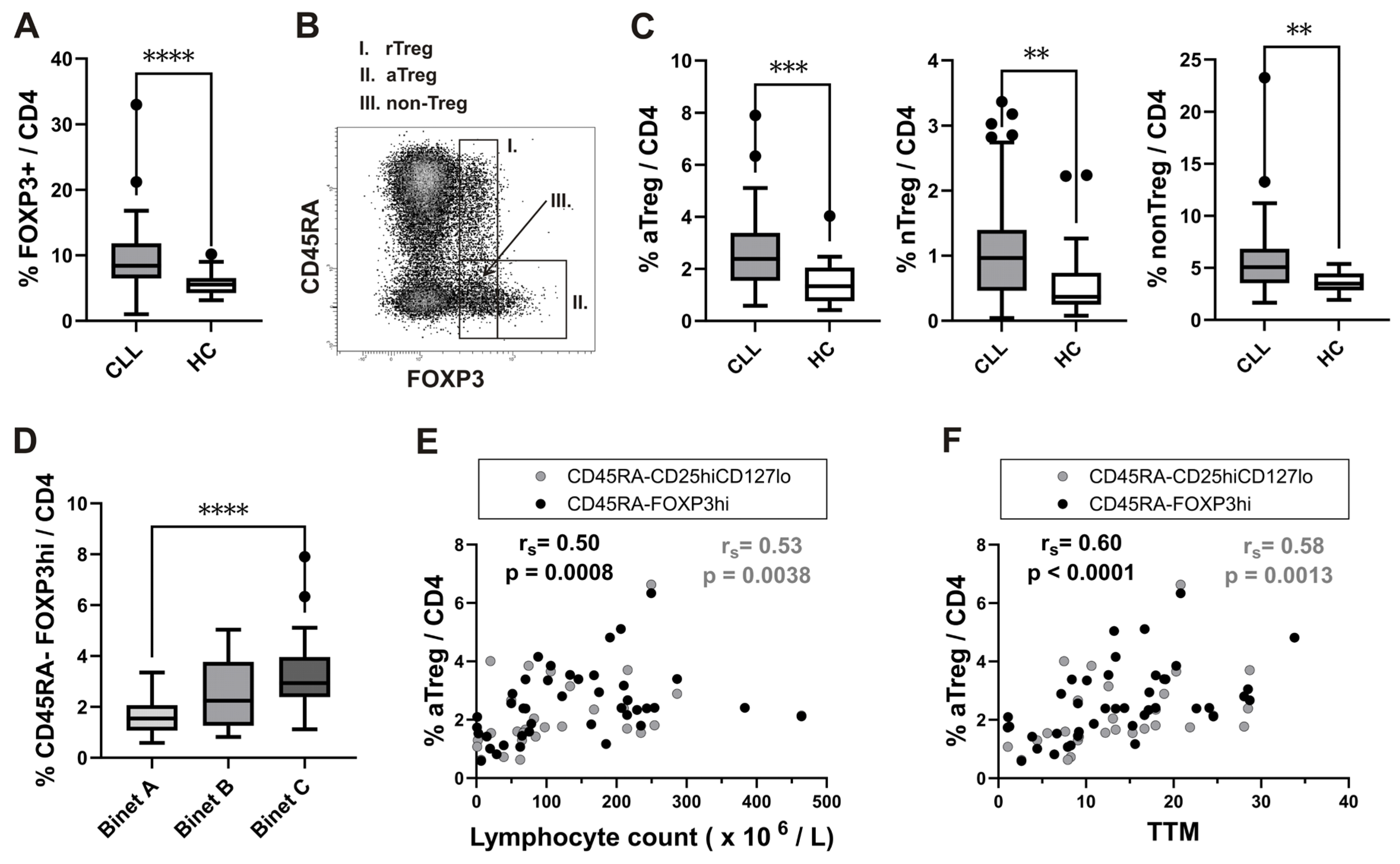

3.1. The Increase in Activated Treg Subset in Peripheral Blood from CLL Patients with Untreated Advanced Disease Correlates with Total Tumor Mass (TTM) Scoring

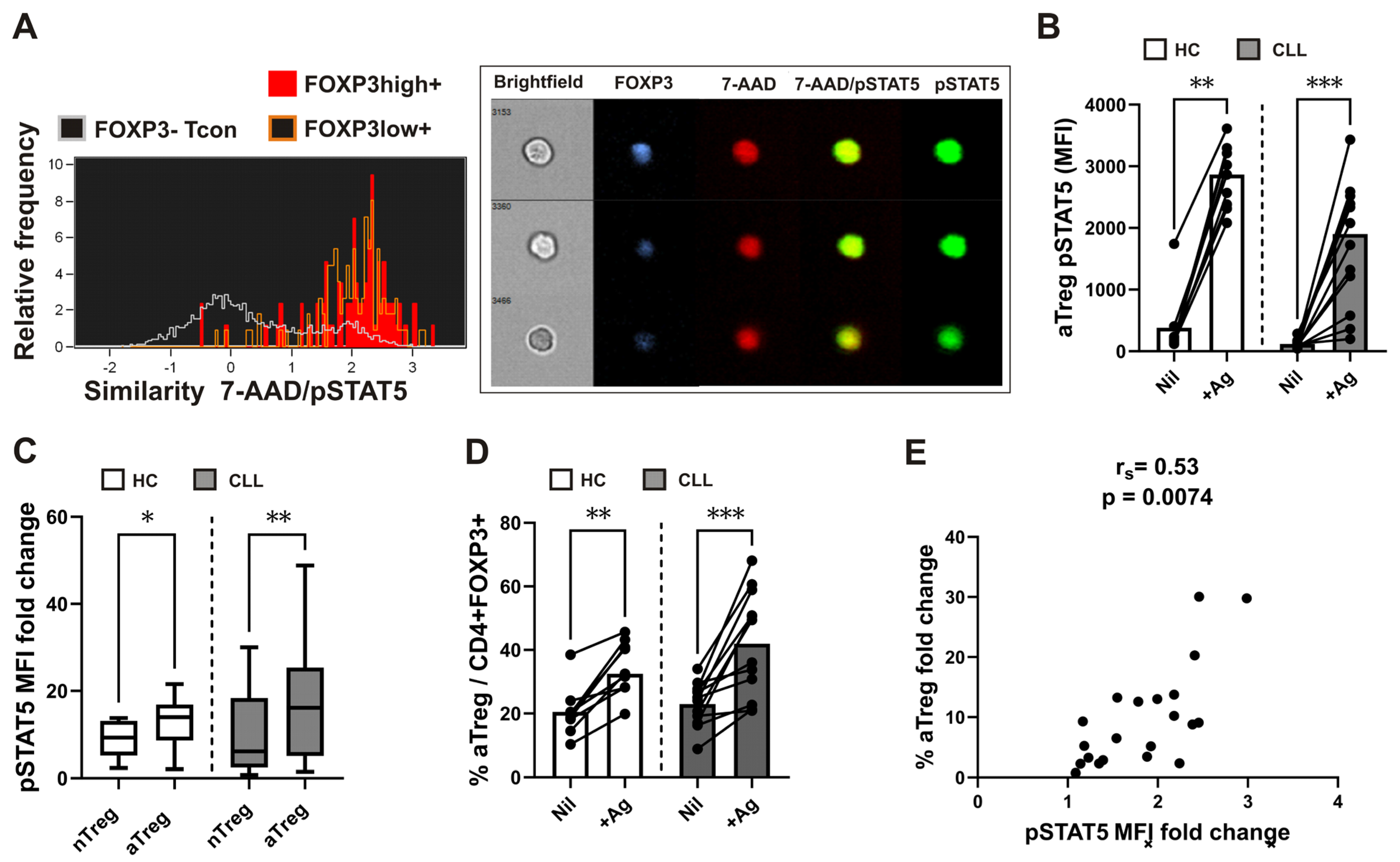

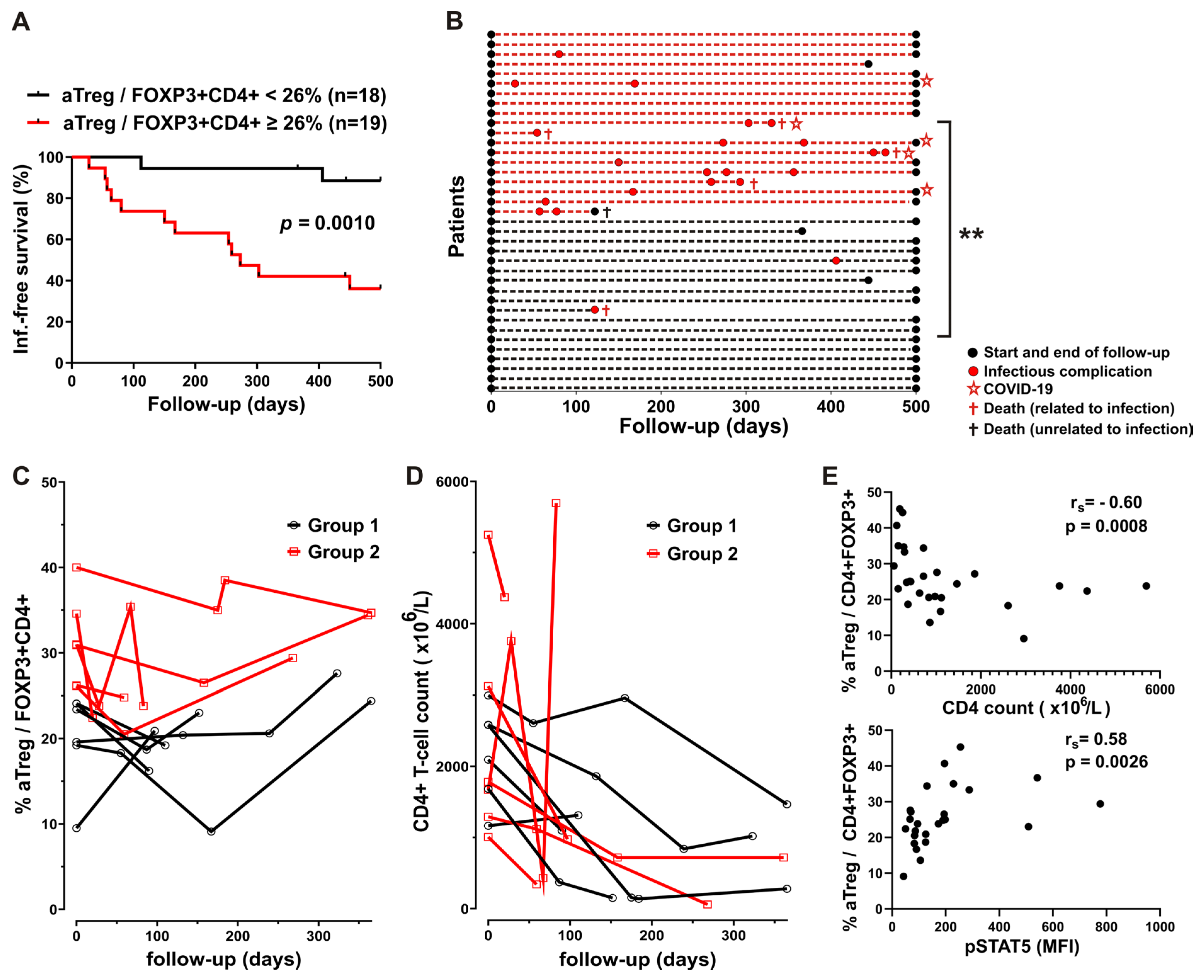

3.2. Increased Proportions of aTregs among FOXP3+CD4+ T Cells are Associated with Their Augmented STAT5 Signaling Responses following Whole Blood SARS-CoV-2 Antigen-Specific Stimulation

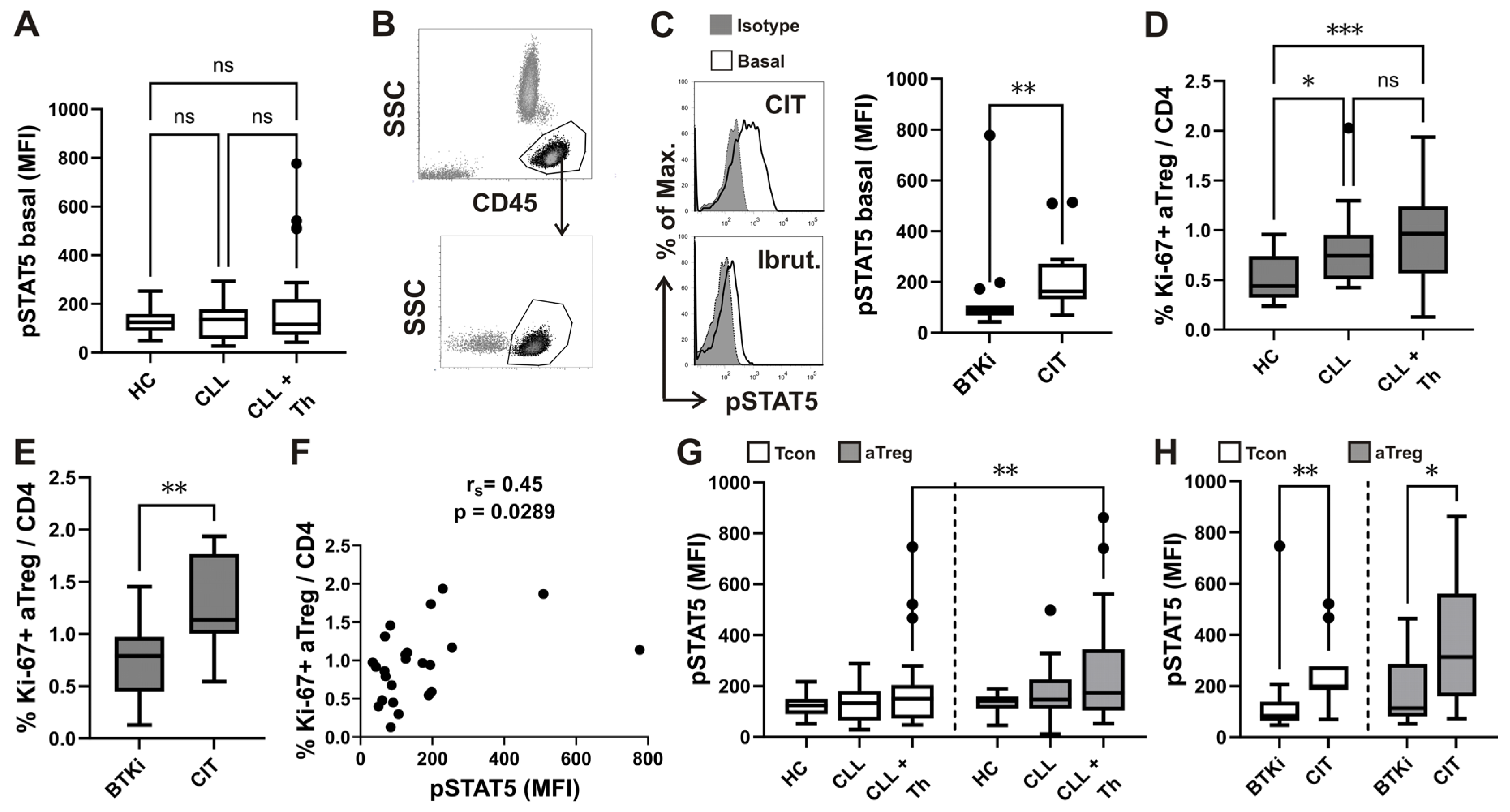

3.4. Higher Basal STAT5 Phosphorylation Levels in CD4 T Cells from Patients with CLL Treated with Chemo-Immunotherapy

3.5. Relationship between STAT5 Phosphorylation and Ki-67 Expressing CD4 T Cell Subsets

3.6. Differences in Basal STAT5 Phosphorylation between aTreg and Conventional T-Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois N, Crompot E, Meuleman N, Bron D, Lagneaux L, Stamatopoulos B. Importance of Crosstalk between Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and the Stromal Microenvironment: direct contact, soluble factors, and Extracellular vesicles. Front Oncol. 2020; 10, 1422. [CrossRef]

- Scarfò L, Chatzikonstantinou T, Rigolin GM, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a joint study by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL, and CLL Campus. Leukemia, 2020; 34, 2354–2363. [CrossRef]

- Hospital P, Alliance CC, York N, Hospital P, Hospital B, Cornell W. Outcomes of COVID-19 in Patients with CLL: A Multicenter, International Experience. 2021.

- Hilal T, Gea-Banacloche JC, Leis JF. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and infection risk in the era of targeted therapies: Linking mechanisms with infections. BloodRev. 2018; 32, 387–399. [CrossRef]

- Arruga F, Gyau BB, Iannello A, Vitale N, Vaisitti T, Deaglio S. Immune Response Dysfunction in Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: dissecting Molecular Mechanisms and Microenvironmental Conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21, 1825. [CrossRef]

- Langerbeins P, Eichhorst B. Immune Dysfunction in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Challenges during COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Haematol, 2021; 144, 508–518. [CrossRef]

- Teh BW, Tam CS, Handunnetti S, Worth LJ, Slavin MA. Infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Mitigating risk in the era of targeted therapies. Blood Rev. 2018; 32, 499–507. [CrossRef]

- Parry H, McIlroy G, Bruton R, et al. Antibody responses after first and second Covid-19 vaccination in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11(7), 136. [CrossRef]

- Benda M, Mutschlechner B, Ulmer H, et al. Serological SARS-CoV-2 antibody response, potential predictive markers and safety of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in haematological and oncological patients. Br J Haematol, 2021; 195, 523–531.

- Shevach, E. M. , Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity. Annu. Rev.Immunol. 2000, 18, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 241, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004; 22, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh R, Elkord E. FoxP3+ T regulatory cells in cancer: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2020; 490, 174–185. [CrossRef]

- Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009, 30, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Simons DL, Lu X, Tu TY, Solomon S, Wang R, Rosario A, Avalos C, Schmolze D, Yim J, Waisman J, Lee PP. Connecting blood and intratumoral Treg cell activity in predicting future relapse in breast cancer. Nat Immunol. 2019, 20(9), 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’arena, G.; Laurenti, L.; Minervini, M.M.; Deaglio, S.; Bonello, L.; De Martino, L.; De Padua, L.; Savino, L.; Tarnani, M.; De Feo, V.; et al. Regulatory T-cell number is increased in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients and correlates with progressive disease. Leuk. Res. 2011, 35, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpakou, V.E.; Ioannidou, H.-D.; Konsta, E.; Vikentiou, M.; Spathis, A.; Kontsioti, F.; Kontos, C.K.; Velentzas, A.D.; Papageorgiou, S.; Vasilatou, D.; et al. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of regulatory T cells in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2017, 60, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arena, G.; D’Auria, F.; Simeon, V.; Laurenti, L.; Deaglio, S.; Mansueto, G.; Del Principe, M.I.; Statuto, T.; Pietrantuono, G.; Guariglia, R.; et al. A shorter time to the first treatment may be predicted by the absolute number of regulatory T-cells in patients with Rai stage 0 chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, 628–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; Melchardt, T.; Egle, A.; Grabmer, C.; Greil, R.; Tinhofer, I. Regulatory T cells predict the time to initial treatment in early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2010, 117, 2163–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrvold IK, Cremaschi A, Hermansen JU, Tjønnfjord GE, Munthe LA, Taskén K, Skånland SS. Single cell profiling of phospho-protein levels in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2018; 9, 9273–9284. [CrossRef]

- Blix ES, Irish JM, Husebekk A, Delabie J, Forfang L, Tierens AM, Myklebust JH, Kolstad A. Phospho-specific flow cytometry identifies aberrant signaling in indolent B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, Y.; Spolski, R.; Leonard, W.J. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Manlove, L.S.; Farrar, M.A. Interleukin-2 and STAT5 in regulatory T cell development and function. Jakstat. 2013, 2, e23154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, G.; Demaret, J.; Venet, F.; Malergue, F.; Malcus, C.; Poitevin-Later, F.; Morel, J.; Monneret, G. Comparative dose-responses of recombinant human IL-2 and IL-7 on STAT5 phosphorylation in CD4+FOXP3− cells versus regulatory T cells: A whole blood perspective. Cytokine, 2014; 69, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallek, M.; Cheson, B.D.; Catovsky, D.; Caligaris-Cappio, F.; Dighiero, G.; Döhner, H.; Hillmen, P.; Keating, M.; Montserrat, E.; Chiorazzi, N.; et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018, 131, 2745–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binet, J.L.; Auquier, A.; Dighiero, G.; Chastang, C.; Piguet, H.; Goasguen, J.; Vaugier, G.; Potron, G.; Colona, P.; Oberling, F.; et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981, 48, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksić B, Vitale B. Total tumour mass score (TTM): a new parameter in chronic lymphocyte leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1981; 49, 405–413. [CrossRef]

- Trapecar, M.; Goropevšek, A.; Gorenjak, M.; Gradisnik, L.; Rupnik, M.S. A Co-Culture Model of the Developing Small Intestine Offers New Insight in the Early Immunomodulation of Enterocytes and Macrophages by Lactobacillus spp. through STAT1 and NF-kB p65 Translocation. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9, e86297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.C.; Fanning, S.L.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P.; Medeiros, R.B.; Highfill, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Hall, B.E.; Frost, K.; Basiji, D.; Ortyn, W.E.; et al. Quantitative measurement of nuclear translocation events using similarity analysis of multispectral cellular images obtained in flow. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006, 311, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baecher-Allan, C. , Brown, J. A., Freeman, G. J., Hafler, D. A. CD4+ CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S. , Miyara, M., Costantino, C. M., Hafler, D. A. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roškar Z, Dreisinger M, Tič P, Homšak E, Bevc S, Goropevšek A. New Flow Cytometric Methods for Monitoring STAT5 Signaling Reveal Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Antigen-Specific Stimulation in FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells also in Patients with Advanced Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Biosensors (Basel). 2023; 13, 539.

- Krutzik, P.O.; Nolan, G.P. Intracellular phospho-protein staining techniques for flow cytometry: Monitoring single cell signaling events. Cytometry A. 2003, 55, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Peña S, Leon J, Chowdhary K, Michelson DA, Vijaykumar B, Yang L, Magnuson AM, Chen F, Manickas-Hill Z, Piechocka-Trocha A, Worrall DP, Hall KE, Ghebremichael M, Walker BD, Li JZ, Yu XG; MGH COVID-19 Collection & Processing Team; Mathis D, Benoist C. Profound Treg perturbations correlate with COVID-19 severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021; 118, e2111315118.36. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, E. F. , Lyons, P. A., Carr, E. J., Hollis, J. L., Jayne, D. R., Willcocks, L. C., Koukoulaki, M., Brazma, A., Jovanovic, V., Kemeny, D. M., Pollard, A. J., Macary, P. A., Chaudhry, A. N., Smith, K. G. A CD8+ T cell transcription signature predicts prognosis in autoimmune disease. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goropevšek, A.; Gorenjak, M.; Gradišnik, S.; Dai, K.; Holc, I.; Hojs, R.; Krajnc, I.; Pahor, A.; Avčin, T. STAT5 phosphorylation in CD4 T cells from patients with SLE is related to changes in their subsets and follow-up disease severity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 101, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, J. , Lemke, H., Baisch, H., Wacker, H. H., Schwab, U., Stein, H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J. Immunol. 1984, 133, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goral A, Firczuk M, Fidyt K, Sledz M, Simoncello F, Siudakowska K, Pagano G, Moussay E, Paggetti J, Nowakowska P, Gobessi S, Barankiewicz J, Salomon-Perzynski A, Benvenuti F, Efremov DG, Juszczynski P, Lech-Maranda E, Muchowicz A. A Specific CD44lo CD25lo Subpopulation of Regulatory T Cells Inhibits Anti-Leukemic Immune Response and Promotes the Progression in a Mouse Model of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Front Immunol. 2022; 28, 13:781364. [CrossRef]

- Piper KP, Karanth M, McLarnon A, Kalk E, Khan N, Murray J, Pratt G, Moss PA. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells drive the global CD4+ T cell repertoire towards a regulatory phenotype and leads to the accumulation of CD4+ forkhead box P3+ T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011; 166, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta A, Mahapatra M, Saxena R. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of regulatory T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: comparative assessment of various markers and use of novel antibody panel with CD127 as alternative to transcription factor FoxP3. Leuk Lymphoma, 2013; 54, 778–789. [CrossRef]

- Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008; 322, 271–275.

- Gorgun G, Ramsay AG, Holderried TA, Zahrieh D, Le Dieu R, Liu F, et al. E(mu)-TCL1 mice represent a model for immunotherapeutic reversal of chronic lymphocytic leukemia-induced T-cell dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106, 6250–6255.

- Saulep-Easton D, Vincent FB, Quah PS, Wei A, Ting SB, Croce CM, et al. The BAFF receptor TACI controls IL-10 production by regulatory b cells and CLL b cells. Leukemia. 2016; 30, 163–172. [CrossRef]

- Allegra A, Musolino C, Tonacci A, Pioggia G, Casciaro M, Gangemi S. Clinico-Biological Implications of Modified Levels of Cytokines in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Possible Therapeutic Role. Cancers (Basel). 2020; 12, 524. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi M, Movassaghpour AA, Shamsasenjan K, Ghalamfarsa G, Sadreddini S, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Hojjat-Farsangi M. The skewed balance between Tregs and Th17 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Future Oncol. 2015, 11(10), 1567–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancotto A, Dagur PK, Fuchs JC, Wiestner A, Bagwell CB, McCoy JP Jr. Phenotypic complexity of T regulatory subsets in patients with B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mod Pathol, 2012; 25, 246–259. [CrossRef]

- Gonder S, Fernandez Botana I, Wierz M, Pagano G, Gargiulo E, Cosma A, Moussay E, Paggetti J, Largeot A. Method for the Analysis of the Tumor Microenvironment by Mass Cytometry: Application to Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Front Immunol. 2020; 20, 11:578176. [CrossRef]

- Dikiy S, Li J, Bai L, Jiang M, Janke L, Zong X, Hao X, Hoyos B, Wang ZM, Xu B, Fan Y, Rudensky AY, Feng Y. A distal Foxp3 enhancer enables interleukin-2 dependent thymic Treg cell lineage commitment for robust immune tolerance. Immunity. 2021; 54, 931–946.e11. [CrossRef]

- O'Gorman WE, Dooms H, Thorne SH, Kuswanto WF, Simonds EF, Krutzik PO, Nolan GP, Abbas AK. The initial phase of an immune response functions to activate regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009, 183(1), 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer MC, Joosten SA, Ottenhoff TH. Regulatory T-Cells at the Interface between Human Host and Pathogens in Infectious Diseases and Vaccination. Front Immunol. 2015; 6, 217. [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos K, Schmitt M, Kowal M, Wlasiuk P, Bojarska-Junak A, Chen J, et al. Characterization of regulatory T cells in patients with b-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncol Rep 2008, 20(3), 677–682.

- Trujillo-Ochoa JL, Kazemian M, Afzali B. The role of transcription factors in shaping regulatory T cell identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023, 23(12), 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi VLD, Garaud S, De Silva P, Thibaud V, Stamatopoulos B, Berehad M, Gu-Trantien C, Krayem M, Duvillier H, Lodewyckx JN, Willard-Gallo K, Sibille C, Bron D. Age-related changes in the BACH2 and PRDM1 genes in lymphocytes from healthy donors and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. BMC Cancer, 2019; 19, 81. [CrossRef]

- Grant FM, Yang J, Nasrallah R, Clarke J, Sadiyah F, Whiteside SK, Imianowski CJ, Kuo P, Vardaka P, Todorov T, Zandhuis N, Patrascan I, Tough DF, Kometani K, Eil R, Kurosaki T, Okkenhaug K, Roychoudhuri R. BACH2 drives quiescence and maintenance of resting Treg cells to promote homeostasis and cancer immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 2020, 217(9):e20190711. [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo C, Szoltysek K, Zhou P, Pietrowska M, Marczak L, Willmore E, Enshaei A, Walaszczyk A, Ho JY, Rand V, Marshall S, Hall AG, Harrison CJ, Soundararajan M, Eswaran J. Low BACH2 Expression Predicts Adverse Outcome in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 14(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier M, Durrieu F, Martin E, Peres M, Vergez F, Filleron T, Obéric L, Bijou F, Quillet Mary A, Ysebaert L. Prognostic role of CD4 T-cell depletion after frontline fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19, 809. [CrossRef]

- Vodárek P, Écsiová D, Řezáčová V, Souček O, Šimkovič M, Vokurková D, Belada D, Žák P, Smolej L. A comprehensive assessment of lymphocyte subsets, their prognostic significance, and changes after first-line therapy administration in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Med. 2023; 12, 6956–6970.

- Papazoglou D, Wang XV, Shanafelt TD, Lesnick CE, Ioannou N, De Rossi G, Herter S, Bacac M, Klein C, Tallman MS, Kay NE, Ramsay AG. Ibrutinib-based therapy reinvigorates CD8+ T cells compared to chemoimmunotherapy: immune monitoring from the E1912 trial. Blood. 2024; 143, 57–63.

- Lord, J. D. , McIntosh, B. C., Greenberg, P. D., Nelson, B. H. The IL-2 receptor promotes lymphocyte proliferation and induction of the c-myc, bcl-2, and bcl-x genes through the trans-activation domain of Stat5. J. Immunol. 2000; 164, 2533–2541. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cheng X, Yang H, Lian S, Jiang Y, Liang J, Chen X, Mo S, Shi Y, Zhao S, Li J, Jiang R, Yang DH, Wu Y. BCL-2 expression promotes immunosuppression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by enhancing regulatory T cell differentiation and cytotoxic T cell exhaustion. Mol Cancer. 2022; 21, 59. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Group1a | Group2a | P | Adjusted P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort size | 18 | 19 | NA | NA |

| Age (y) | 68 (3) | 70 (2) | 0.93 | NS |

| Gender | 5F / 13 M | 8F / 11M | 0.49 | NS |

| Ethnicity | 19 Slovene | 19 Slovene | NA | NA |

| Binet stage C | 10 / 18 | 15 / 19 | 0.17 | NA |

| Disease duration (mo) | 49 (15) | 60 (11) | 0.32 | NS |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 64 (3) | 65 (2) | 0.89 | NS |

| TTM score t0 | 16.4 (1.8) | 17.0 (1.7) | 0.81 | NS |

| TD score t0 | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.75 (0.04) | 0.69 | NS |

| LN t0 (cm) | 1.8 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.8) | 0.25 | NS |

| Spleen t0 (cm) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.1) | 0.60 | NS |

| Lymphocytes t0 (×109/L) | 170.8 (30.5) | 146.5 (19.2) | 0.68 | NS |

| Neutrophils t0 (×109/L) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.4) | 0.89 | NS |

| CD4 count t0 (×103/L) | 2129 (238) | 2445 (300) | 0.77 | NS |

| CD4% t0 (%) | 3.7 (1.6) | 2.1 (0.3) | 0.48 | NS |

| TP53 mutation | 4/18 | 1/19 | 0.18 | NS |

| Unmutated IGHV | 11/18 | 8/19 | 0.33 | NS |

| AIHA | 2/18 | 2/19 | >0.99 | NS |

| Preexisting CLL therapy | 7/18 | 5/19 | 0.49 | NS |

| Hgb t0 (g/L) | 104 (4) | 108 (7) | 0.96 | NS |

| Tr t0 (×109/L) | 158 (23) | 128 (12) | 0.43 | NS |

| Therapy | Combinations | Group1a | Group2a | P | Adjusted P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | ||||

| CIT | All | 4/18 | 25 | 8/19 | 42 | 0.29 | NS |

| FCR | 0/18 | 0 | 4/19 | 21 | 0.10 | NS | |

| Chlorambucil + Rituximab | 2/18 | 11 | 4/19 | 21 | 0.66 | NS | |

| Chlorambucil + Obinutuzumab | 1/18 | 5 | 0/19 | 0 | 0.49 | NS | |

| Bendamustine + Rituximab | 1/18 | 5 | 0/19 | 0 | 0.49 | NS | |

| BTKi | All | 11/18 | 61 | 8/19 | 42 | 0.33 | NS |

| Ibrutinib | 5/18 | 28 | 6/19 | 32 | >0.99 | NS | |

| Acalabrutinib | 4/18 | 22 | 2/19 | 10 | 0.40 | NS | |

| Acalabrutinib + Obinutuzumab | 2/18 | 11 | 0/19 | 0 | 0.23 | NS | |

| Venetoclax | All combinations | 3/18 | 17 | 3/19 | 16 | >0.99 | NS |

| + Rituximab | 0/18 | 0 | 2/19 | 10 | 0.49 | NS | |

| + Obinutuzumab | 1/18 | 5 | 0/19 | 0 | >0.99 | NS | |

| + Bendamustine + Obinutuzumab | 2/18 | 11 | 1/19 | 5 | 0.60 | NS | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).