Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

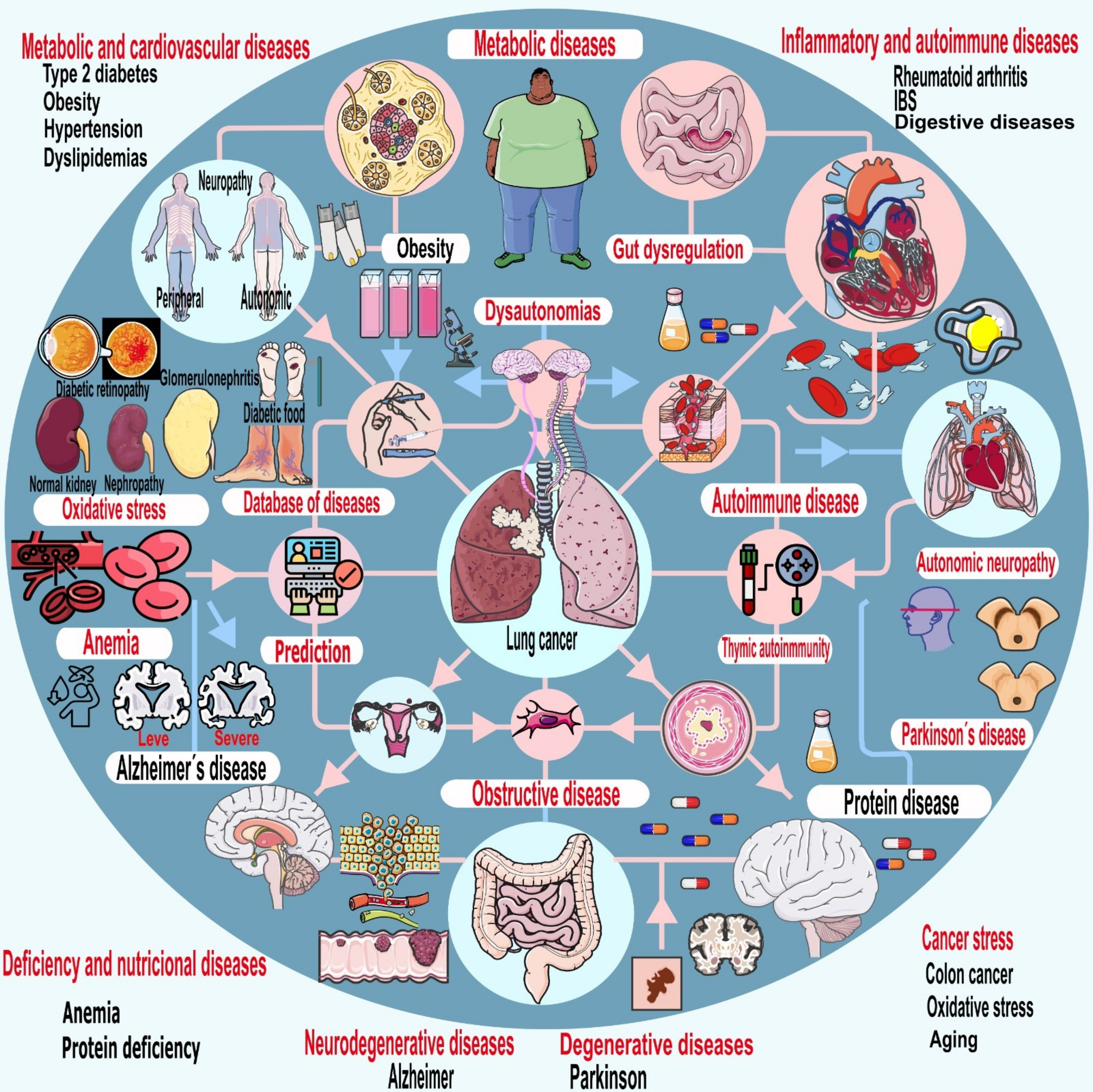

1. Introduction

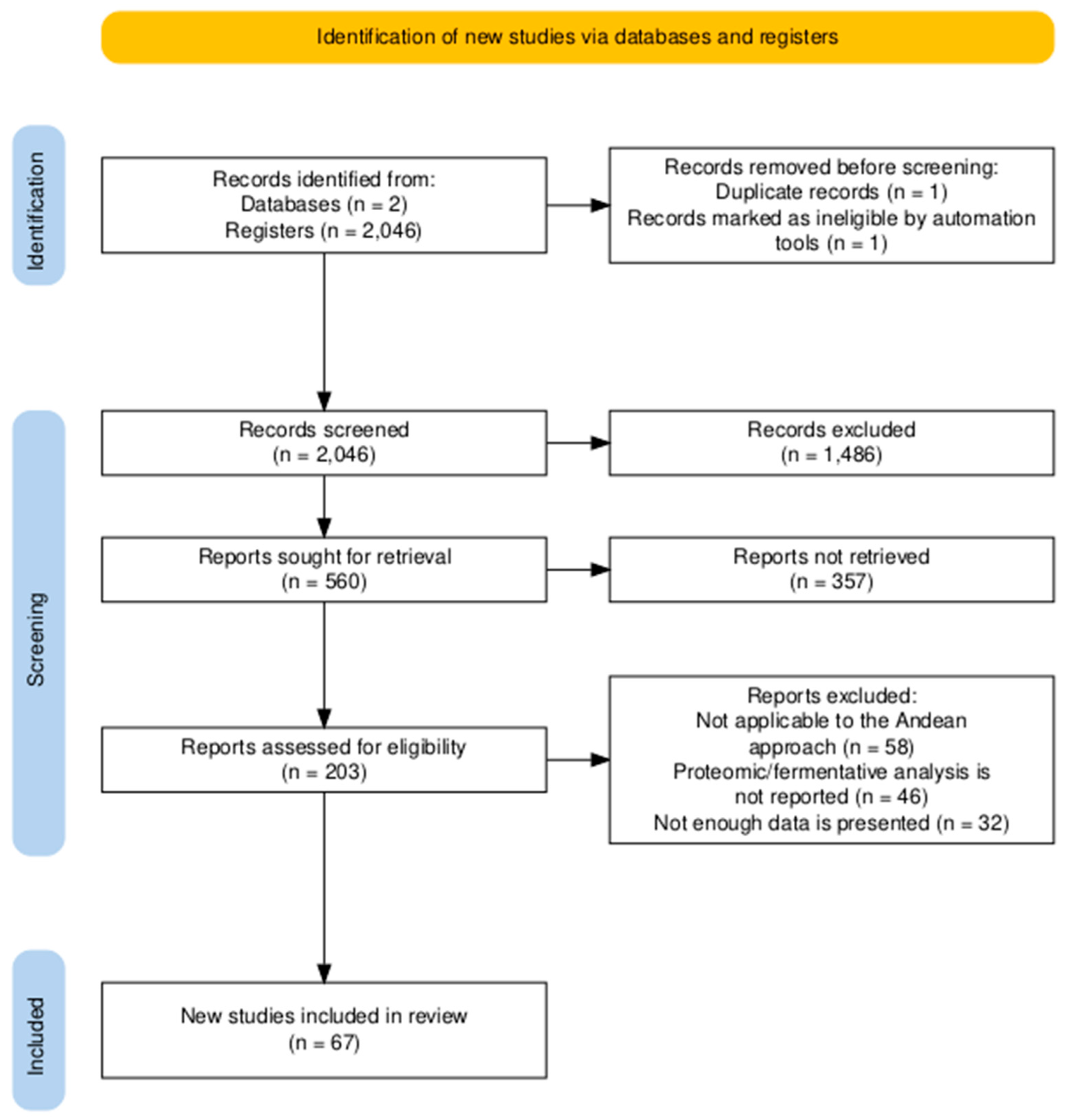

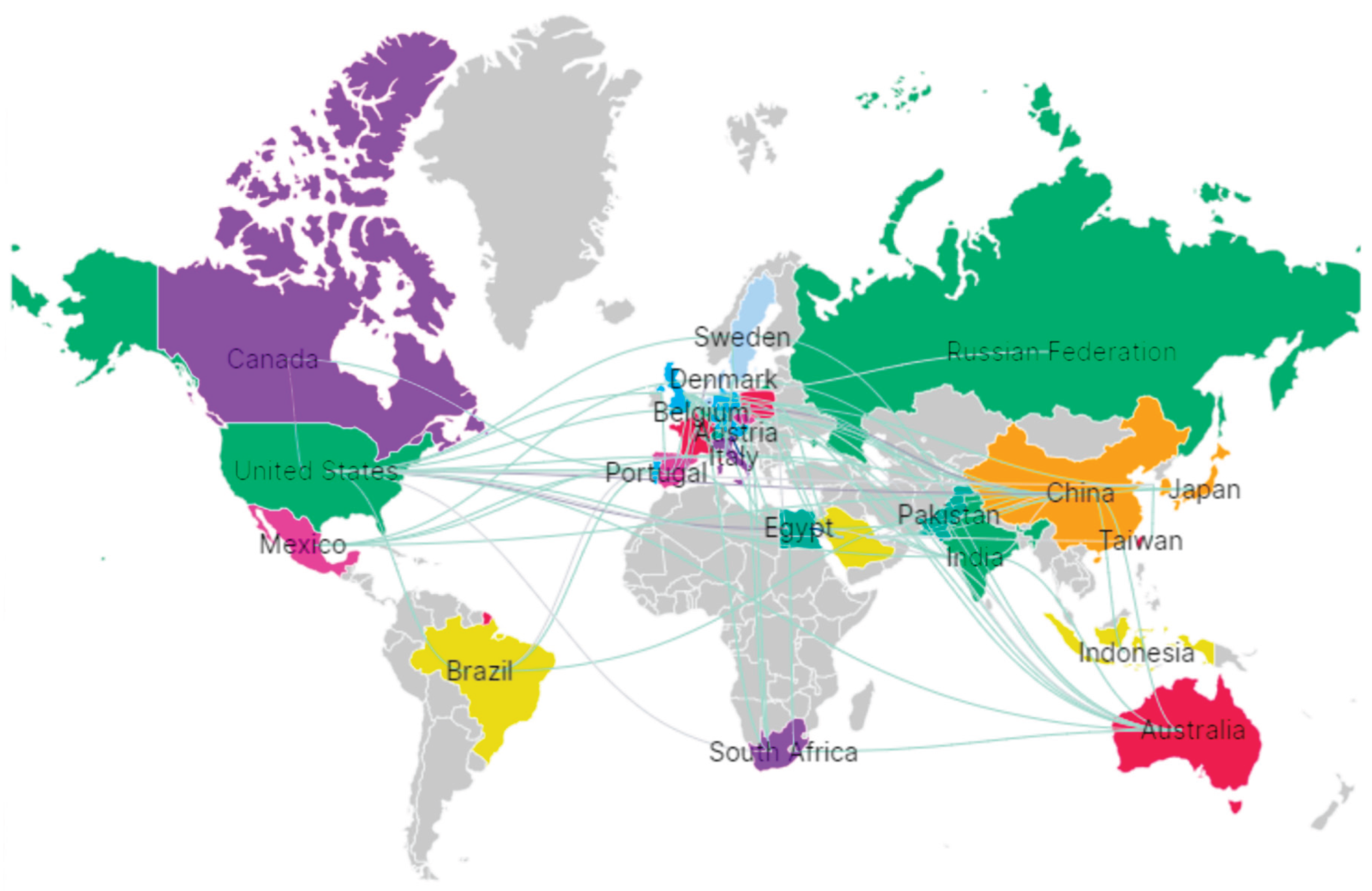

2. Materials and Methods

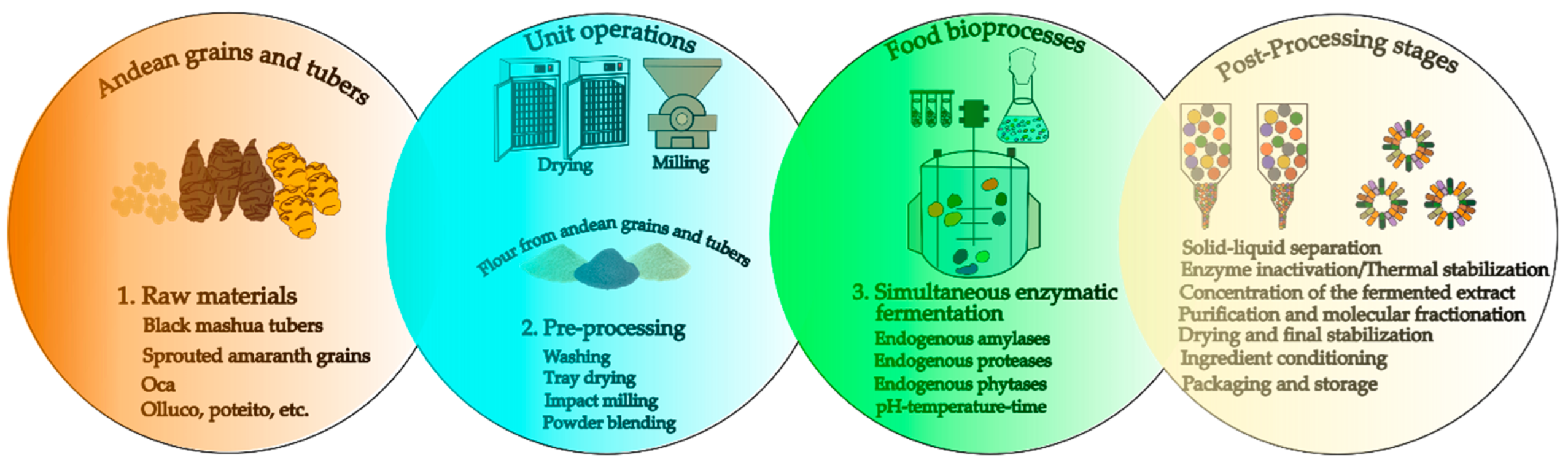

3. Fermentation of Andean Grains and Tubers

3.1. Enzymatic Fermentation of Andean Grains

3.2. Andean Matrices Based on Traditional and Non-Traditional Tubers

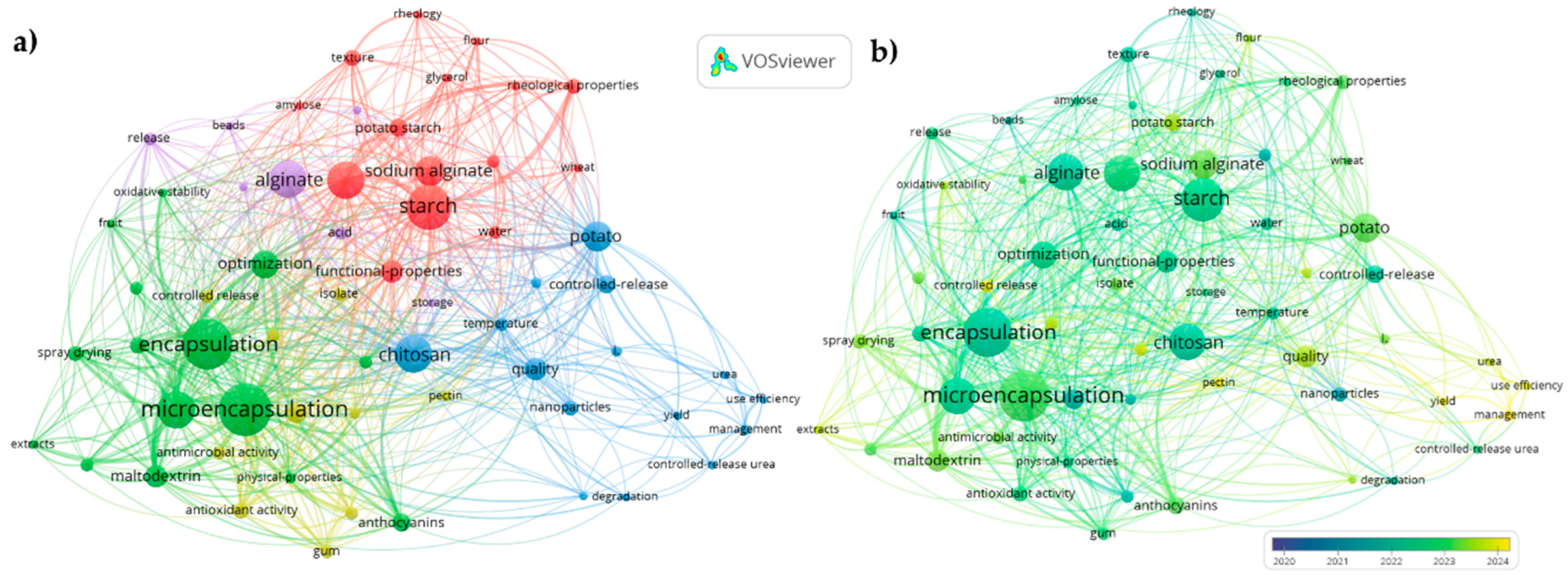

4. Bioencapsulation in Andean Functional Foods

4.1. Microencapsulation and Nanoencapsulation Strategies

4.2. Controlled Release Systems of Bioactive Compounds

4.3. Stability and Bioavailability of Encapsulated Metabolites

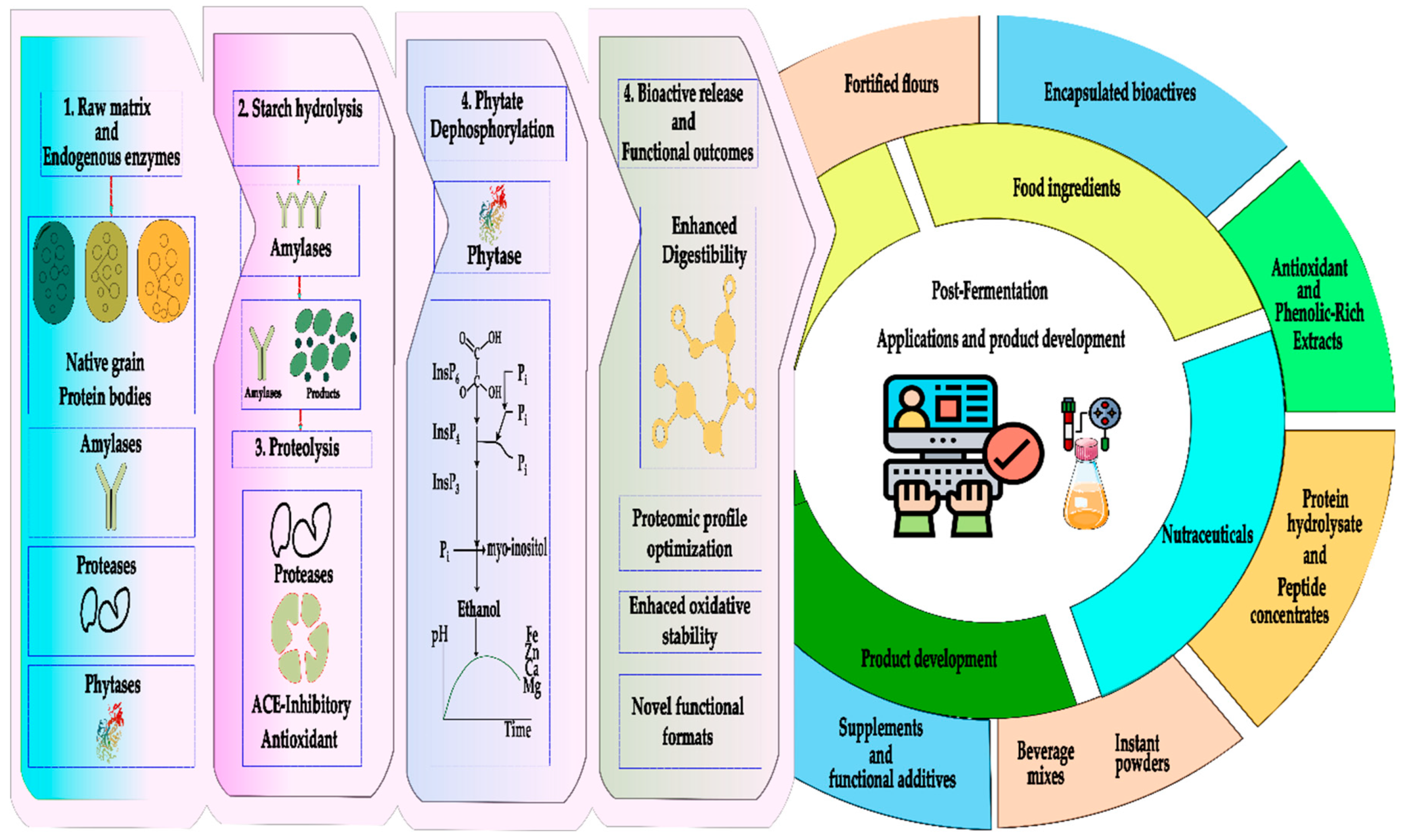

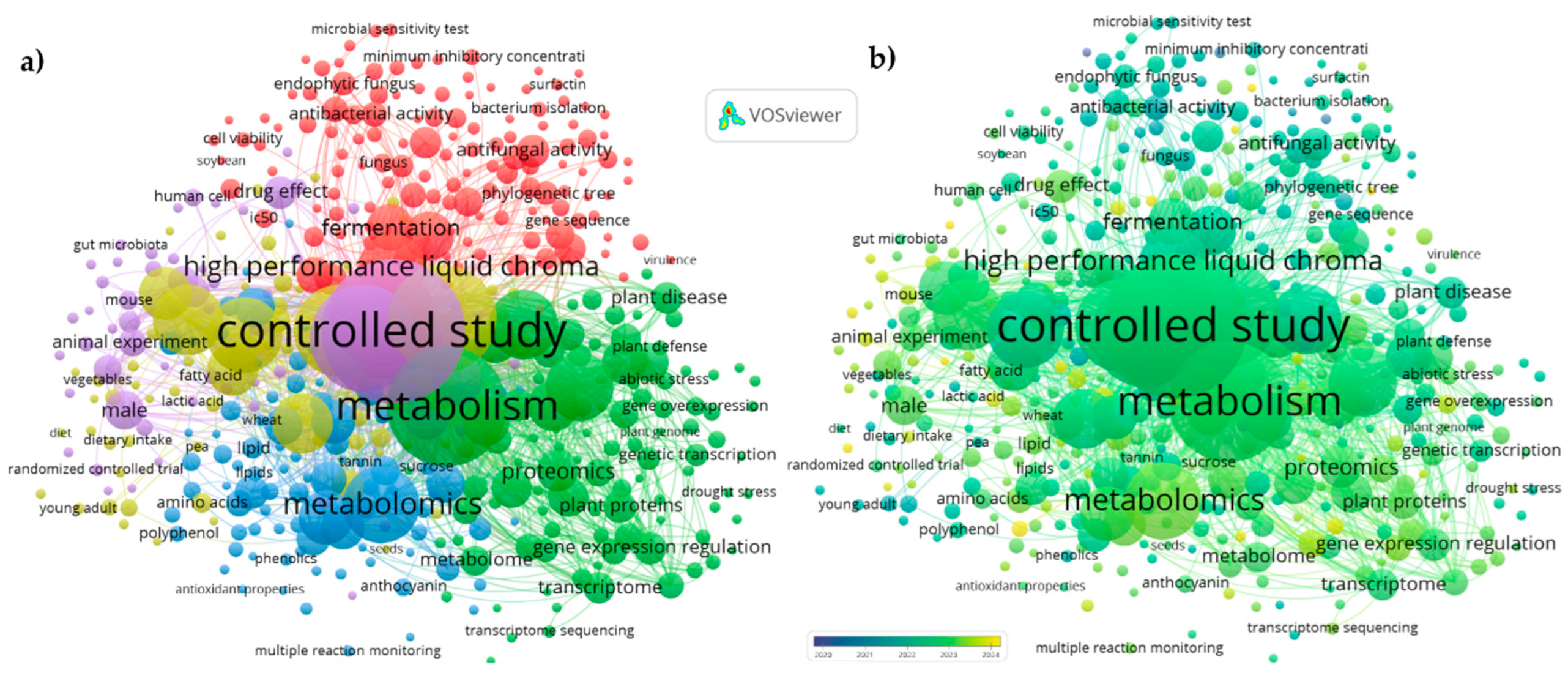

5. Proteomic Advances in Fermented Grains and Tubers

5.1. Identification of Bioactive Peptides

5.2. Enzymatic Proteomics and Protein Digestibility

5.3. Relationship Between Proteomics and Functional Properties

6. Food Applications of Fermented and Bioencapsulated Products

6.1. Development of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

6.2. Use in Traditional and Modern Food Matrices

6.3. Implications for the Healthy Food Industry

7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

7.1. Technological Challenges in Fermentation and Bioencapsulation of Grains and Tubers

7.2. Limitations in the Industrial Scalability of Bioprocesses Applied to Andean Matrices

7.3. Analytical Limitations and Gaps in Metabolomic and Proteomic Characterization

7.4. Regulatory Barriers and Standardization of Functional Ingredients

7.5. Innovative Perspectives for the Development of Functional Foods Based on Biotransformation

7.6. Integration of Emerging Technologies for Future Applications in Andean Grains and Tubers

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Gao, X.; Xu, H.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, D.; Wang, Y. A Simple and Effective Method to Enhance the Level of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid in Chinese Yam Tubers While Preserving Its Original Appearance. Food Chem X 2025, 27. [CrossRef]

- Marcel, M.R.; Chacha, J.S.; Ofoedu, C.E. Nutritional Evaluation of Complementary Porridge Formulated from Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato, Amaranth Grain, Pumpkin Seed, and Soybean Flours. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10, 536–553. [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.; Beccari, G.; Vella, G.F.; Filippucci, R.; Buldini, D.; Onofri, A.; Sulyok, M.; Covarelli, L. Marketed Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Seeds: A Mycotoxin-Free Matrix Contaminated by Mycotoxigenic Fungi. Pathogens 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Baltacıoğlu, C.; Yetişen, M.; Baltacioǧlu, H.; Karacabey, E.; Buzrul, S. Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) Treatment Prior to Hot-Air and Microwave Drying of Yellow- and Purple-Fleshed Potatoes. Potato Res 2025, 68, 1171–1188. [CrossRef]

- Jamanca Gonzales, N.C.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Eguilas-Caushi, Y.M.; Padilla-Fabian, R.A.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Technofunctional Properties and Rheological Behavior of Quinoa, Kiwicha, Wheat Flours and Their Mixtures. Molecules 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Marroquín, L.A.; Yucra Condori, H.R.; Gárate Delgado, J.; Mendoza, C.; de Florio Ramírez, E. Effect of Heat Processing on Bioactive Compounds of Dehydrated (Lyophilized) Purple Mashua (Tropaeolum Tuberosum). Scientia Agropecuaria 2023, 14, 321–333. [CrossRef]

- Ajbli, N.; Zine-eddine, Y.; Laaraj, S.; Ait El Alia, O.; Elfazazi, K.; Bouhrim, M.; Herqash, R.N.; Shahat, A.A.; BenBati, M.; Kzaiber, F. Effect of Quinoa Flour on Fermentation, Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Goat Milk Yogurt. Front Sustain Food Syst 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, C.; Alvarado, R.; Ortiz, J.; Campos-Vargas, R.; Cornejo, P. Alginate–Bentonite Encapsulation of Extremophillic Bacterial Consortia Enhances Chenopodium Quinoa Tolerance to Metal Stress. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Ramos-González, R.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Rodríguez, R.; Iliná, A.; Esparza-González, S.C.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Antihypertensive Amaranth Protein Hydrolysates Encapsulation in Alginate/Pectin Beads: Influence on Bioactive Properties upon In Vitro Digestion. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 450–462. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Bao, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, P.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Ge, G. Utilisation of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum and Propionic Acid to Improve Silage Quality of Amaranth before and after Wilting: Fermentation Quality, Microbial Communities, and Their Metabolic Pathway. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Morán, D.; Loṕez-Carballo, G.; Gavara, R.; Gutiérrez, G.; Matos, M. Starch-Silver Hybrid Nanoparticles: A Novel Antimicrobial Agent. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2025, 717. [CrossRef]

- El-Sohaimy, S.A.; Mehany, T.; Shehata, M.G.; Zeitoun, A.A.; Alharbi, H.M.; Alwutayd, K.M.; Zeitoun, M.A.M. Optimizing Functional, Stability, and Sensory Attributes of Quinoa Beverages through Bioprocessing, Ultrasonication, and Hydrocolloids. Food Chem X 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Schmiele, M.; Vásquez Guzmán, J.C.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Smart Pasta Design: Tailoring Formulations for Technological Excellence with Sprouted Quinoa and Kiwicha Grains. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kuzhithariel Remanan, M.K.; Zhu, F. Encapsulation of Chrysin and Rutin Using Self-Assembled Nanoparticles of Debranched Quinoa, Maize, and Waxy Maize Starches. Carbohydr Polym 2024, 337. [CrossRef]

- Manhokwe, S.; Musarurwa, T.; Jombo, T.Z.; Mugadza, D.T.; Mugari, A.; Bare, J.; Mguni, S.; Chigondo, F.; Muchekeza, J.T. Development of a Quinoa-Based Fermentation Medium for Propagation of Lactobacillus Plantarum and Weissella Confusa in Opaque Beer Production. Int J Microbiol 2025, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sakoui, S.; Derdak, R.; Jouga, F.; Dagni, A.; Pop, O.L.; Cristian Vodnar, D.C.; Teleky, B.-E.; Chiş, M.S.; Pop, C.R.; Stan, L.; et al. The Impact of Fermented Quinoa Sourdough with Enterococcus Strains on the Nutritional, Textural, and Sensorial Features of Gluten-Free Muffins. Fermentation 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Llaguno, N.S.; Guzmán, J.P.M.; Neira-Mosquera, J.A.N.; Aldas-Morejon, J.P.A.; Revilla Escobar, K.Y.R. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fermented Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) for Use in Vegetable Biopreservation. Biodiversitas 2025, 26, 3174–3182. [CrossRef]

- Valerio, F.; Bavaro, A.R.; Di Biase, M.; Lonigro, S.L.; Logrieco, A.F.; Lavermicocca, P. Effect of Amaranth and Quinoa Flours on Exopolysaccharide Production and Protein Profile of Liquid Sourdough Fermented by Weissella Cibaria and Lactobacillus Plantarum. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, C.-J.; Bai, Z.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, W.-Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.-Y.; Liao, A.-M.; Hou, Y.-C. Effects of Different Strains Fermentation on Nutritional Functional Components and Flavor Compounds of Sweet Potato Slurry. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.J.; Kim, A.-J.; Park, M.-J.; Kang, K.; Soung, D.Y. Nutritional and Functional Properties of Fermented Mixed Grains by Solid-State Fermentation with Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens 245. Foods 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, G.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y. Preparation of Antihypertensive Peptides from Quinoa via Fermentation with Lactobacillus Paracasei. eFood 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Olaya, J.L.; Schmiele, M.; Correa, M.J. Potential of Andean Grains as Substitutes for Animal Proteins in Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: A Nutritional and Functional Analysis. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liao, J.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H. Enhancement of Nutritional Value and Sensory Characteristics of Quinoa Fermented Milk via Fermentation with Specific Lactic Acid Bacteria. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Šulc, M.; Rysová, J. Quantification of Seventeen Phenolic Acids in Non-Soy Tempeh Alternatives Based on Legumes, Pseudocereals, and Cereals. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Feng, Y.P.; Xiao, J.H.; Sun, C.; Tu, J.; Niu, L.Y. Sweet Potato Protein Hydrolysates Solidified Calcium-Induced Alginate Gel for Enhancing the Encapsulation Efficiency and Long-Term Stability of Purple Sweet Potato Anthocyanins in Beads. FOOD CHEMISTRY-X 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F.; Mudgil, P.; Gan, C.-Y.; Maqsood, S. Identification and Characterization of Cholesterol Esterase and Lipase Inhibitory Peptides from Amaranth Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chem X 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cen, Q.; Fan, J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, H.; Hui, F.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.; Qin, L. Impact of Ganoderma Lucidum Fermentation on the Nutritional Composition, Structural Characterization, Metabolites, and Antioxidant Activity of Soybean, Sweet Potato and Zanthoxylum Pericarpium Residues. Food Chem X 2024, 21. [CrossRef]

- Altikardes, E.; Guzel, N. Impact of Germination Pre-Treatments on Buckwheat and Quinoa: Mitigation of Anti-Nutrient Content and Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties. Food Chem X 2024, 21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ma, S.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W. An Integrated Physiology and Proteomics Analysis Reveals the Response of Wheat Grain to Low Temperature Stress during Booting. J Integr Agric 2025, 24, 114–131. [CrossRef]

- Hamdin, N.E.; Hussain, H.; Chong, N.F.-M.; Zulkharnain, A. Differentially expressed protein profiles of bario upland and mr219 lowland rice cultivars. J Sustain Sci Manag 2025, 20, 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Serikawa, J.; Okutsu, K.; Yoshizaki, Y.; Futagami, T.; Tamaki, H.; Takamine, K. Impact of Fermentation Temperature on the Quality and Sensory Characteristics of Imo-Shochu. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 2021, 127, 417–423. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Gao, X.; Yan, P. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions and Product Identification of a Saponin-Producing Endophytic Fungus. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Portillo, S.; Salazar-Sánchez, M.R.; Campos-Muzquiz, L.G.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Badillo, C.M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Rodríguez, R. Proximal Characteristics, Phenolic Compounds Profile, and Functional Properties of Ullucus Tuberosus and Arracacia Xanthorrhiza. Exploration of Foods and Foodomics 2024, 2, 672–686. [CrossRef]

- Conti, F. V; Trossolo, E.; Filannino, P.; Lanciotti, R.; Patrignani, F.; D’Alessandro, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Verni, M. Bioprocessing of Food Industry Surplus to Obtain Novel Food Ingredients Enriched in Bioactive Peptides. Future Foods 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Olaya, J.L.; Schmiele, M.; Correa, M.J. Potential of Andean Grains as Substitutes for Animal Proteins in Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: A Nutritional and Functional Analysis. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yavuz-Düzgün, M.; Ayar, E.N.; Sensu, E.; Topkaya, C.; Özçelik, B. A Comparative Study on the Encapsulation of Black Carrot Extract in Potato Protein-Pectin Complexes. JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY-MYSORE 2023, 60, 2628–2638. [CrossRef]

- D’Aniello, A.; Koshenaj, K.; Ferrari, G. A Preliminary Study on the Release of Bioactive Compounds from Rice Starch Hydrogels Produced by High-Pressure Processing (HPP). GELS 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Kamaldeen, O.S.; Ariahu, C.C.; Yusufu, M.I. Application of Soy Protein Isolate and Cassava Starch Based Film Solutions as Matrix for Ionic Encapsulation of Carrot Powders. JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY-MYSORE 2020, 57, 4171–4181. [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, N.; Galante, M.; Spelzini, D. Emulsion Gels Based on Quinoa Protein Hydrolysates, Alginate, and High-Oleic Sunflower Oil: Evaluation of Their Physicochemical and Textural Properties. Food Biophys 2023. [CrossRef]

- Travičić, V.; Ćetković, G.; Ĉanadanović-Brunet, J.; Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Vulić, J.; Stajčić, S. Encapsulation and Degradation Kinetics of Bioactive Compounds from Sweet Potato Peel during Storage. Food Technol Biotechnol 2020, 58, 314–324. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Chen, C.; Zhu, F. Encapsulation of Ferulic Acid in Quinoa Protein and Zein Nanoparticles Prepared through Antisolvent Precipitation: Structure, Stability and Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Biosci 2025, 68. [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Pino, M.T.; Zamora, O.; Parada, J.; Pérez-Dïaz, R.; Uribe, M.; Kalazich, J. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanin Extracted from Purple Flesh Cultivated Potatoes by Spray Drying and Its Effects on in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Munoz, L.; Nielsen, S.D.-H.; Corredig, M. Changes in Potato Peptide Bioactivity after Gastrointestinal Digestion. An in Silico and in Vitro Study of Different Patatin-Rich Potato Protein Isolate Matrices. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Barba-Ostria, C.; Carrero, Y.; Guamán-Bautista, J.; López, O.; Aranda, C.; Debut, A.; Guamán, L.P. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanins from Zea Mays and Solanum Tuberosum: Impacts on Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Cytotoxic Activities. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E. Microencapsulation of Bioactive Compounds from Hesperomeles Escalloniifolia Schltdl (Capachu) in Quinoa Starch and Tara Gum. CYTA-JOURNAL OF FOOD 2025, 23. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Barreto, F.F.; Velezmoro-Sánchez, C.E. Microencapsulation of Purple Mashua Extracts Using Andean Tuber Starches Modified by Octenyl Succinic Anhydride. Int J Food Sci 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Taipe-Pardo, F.; Aguirre Landa, J.P.A.; Arévalo Quijano, J.C.; Muñoz-Saenz, J.C.; Quispe-Quezada, U.R.; Huamán-Carrión, M.L. Nanoencapsulation of Phenolic Extracts from Native Potato Clones (Solanum Tuberosum Spp. Andigena) by Spray Drying. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F.F.; Mudgil, P.; Jobe, A.; Antony, P.; Vijayan, R.; Gan, C.-Y.; Maqsood, S. Novel Plant-Protein (Quinoa) Derived Bioactive Peptides with Potential Anti-Hypercholesterolemic Activities: Identification, Characterization and Molecular Docking of Bioactive Peptides. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.F.; Fan, X.; Wang, Z.D.; Wu, Y.M. Replacing Acetone with Ethanol to Dehydrate Yeast Glucan Particles for Microencapsulating Anthocyanins from Red Radish (Raphanus Sativus L.). LWT-FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 2023, 182. [CrossRef]

- Emragi, E.; Jayanty, S.S. Skin Color Retention in Red Potatoes during Long-Term Storage with Edible Coatings. FOODS 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, J.; Hu, L.; Xiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Meng, Y.; Yang, L. Potato Starch/Sodium Alginate Composite Film Containing Lycopene Microcapsules for Extending Blueberry Shelf Life. Food Packag Shelf Life 2025, 50. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Z.; Shao, S.; Han, X.C.; Zhang, Y.R. Preparation and Characterization of Methyl Jasmonate Microcapsules and Their Preserving Effects on Postharvest Potato Tuber. MOLECULES 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Vaskina, V.A.; Mashkova, I.A.; Bykov, A.A.; Rogozkin, E.N.; Shcherbakova, E.I.; Ruschits, A.A.; Salomatov, A.S. The effect of encapsulated sunflower oil in hydrocolloids shells on the quality and structure of oatmeal cookies. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences of belarus-agrarian series 2024, 62, 68–81. [CrossRef]

- Tadda, S.A.; Kui, X.H.; Yang, H.J.; Li, M.; Huang, Z.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Qiu, D.L. The Response of Vegetable Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas Lam) Nodes to Different Concentrations of Encapsulation Agent and MS Salts. AGRONOMY-BASEL 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.M.; Faria, C.; Madalena, D.; Genisheva, Z.; Martins, J.T.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Valorization of Amaranth (Amaranthus Cruentus) Grain Extracts for the Development of Alginate-Based Active Films. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Moscoso-Moscoso, E.; Pozo, L.M.F.; Ramos-Pacheco, B.S.; Palomino-Rincón, H.; Guzmán Gutiérrez, R.J.G.; Peralta-Guevara, D.E. Effect of Inlet Air Temperature and Quinoa Starch/Gum Arabic Ratio on Nanoencapsulation of Bioactive Compounds from Andean Potato Cultivars by Spray-Drying. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Emragi, E.; Kalita, D.; Jayanty, S.S. Effect of Edible Coating on Physical and Chemical Properties of Potato Tubers under Different Storage Conditions. LWT-FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 2022, 153. [CrossRef]

- Chit, C.S.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Park, J.J.; Lee, W.Y. Effect of Composite Chitosan/Sodium Alginate Gel Coatings on the Quality of Fresh-Cut Purple-Flesh Sweet Potato. GELS 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- GanjiVtan, B.; Hosseini Ghaboos, S.H.; Sadeghi Mahoonak, A.; Shahi, T.; Farzin, N. Spray-Dried Wheat Gluten Protein Hydrolysate Microcapsules: Physicochemical Properties, Retention of Antioxidant Capability, and Release Behavior Under Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Conditions. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tagudin, N.M.F.B.A.; Ibrahim, N.B. Synthesis of Polylactic Acid from Apple, Pineapple, and Potato Residues. ASEAN Journal of Chemical Engineering 2025, 25, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Fu, Q.; Tang, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; et al. Dynamic Changes of Quality Characteristics during Fermentation of Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato Alcoholic Beverage. LWT 2025, 218. [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Peng, J.; Zhang, J.; Ran, S.; Cai, C.; Yu, L.; Ni, S.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X. The Cysteine-Rich Peptide Snakin-2 Negatively Regulates Tubers Sprouting through Modulating Lignin Biosynthesis and H2o2 Accumulation in Potato. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Araujo-León, J.A.; Aguilar-Hernández, V.; del Pino, I.S.; Brito-Argáez, L.; Peraza-Sánchez, S.R.; Xingú-López, A.; Ortiz-Andrade, R. Analysis of Red Amaranth (Amaranthus Cruentus L.) Betalains by LC-MS. J Mex Chem Soc 2023, 67, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Fang, G.; Wang, J. Combined Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses Reveals Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Profiles Between Purple and White Potatoes. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Zaccarelli, A.; Mattina, B.; Galindo-Luján, R.; Pont, L.; Benavente, F.; Zanotti, I.; Elviri, L. Comparative LC-MS Proteomics of Quinoa Grains: Evaluation of Bioactivity and Health Benefits by Combining In Silico Techniques With In Vitro Assays on Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2025, 69. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Q. Comparative Metabolomic Analysis of the Nutrient Composition of Different Varieties of Sweet Potato. Molecules 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Resjö, S.; Willforss, J.; Large, A.; Siino, V.; Alexandersson, E.; Levander, F.; Andréasson, E. Comparative Proteomic Analyses of Potato Leaves from Field-Grown Plants Grown under Extremely Long Days. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 215. [CrossRef]

- Pandya, A.; Thiele, B.; Zurita-Silva, A.; Usadel, B.; Fiorani, F. Determination and Metabolite Profiling of Mixtures of Triterpenoid Saponins from Seeds of Chilean Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) Germplasm. Agronomy 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Zhang, S. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of the Quinoa Seedling Response to High Relative Humidity Stress. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, L.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Guo, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, L.; et al. Integrative Analysis of the Metabolome and Transcriptome Provides Insights into the Mechanisms of Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Quinoa Seeds at Different Developmental Stages. Metabolites 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Sharma, G.; Tomer, N.; Sahaya Shibu, B.S.; Moin, S. Isolation, purification, and characterization of bioactive peptide from chenopodium quinoa seeds: therapeutic and functional insights. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Research 2024, 12, 184–191. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hao, L.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, N.; Zhao, P. Itraq-Based Proteomics Analysis of Response to Solanum Tuberosum Leaves Treated with the Plant Phytotoxin Thaxtomin a. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Tomlekova, N.; Mladenov, P.; Dincheva, I.; Nacheva, E. Metabolic Profiling of Bulgarian Potato Cultivars. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Ma, X.; Sun, W.; Yang, W.; He, R.; Atia-tul-Wahab, A.-T. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Accumulation Patterns of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids in Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Grains of Different Colors. Food Chem X 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dang, B.; Lan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Kuang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. Metabolomics Characterization of Phenolic Compounds in Colored Quinoa and Their Relationship with In Vitro Antioxidant and Hypoglycemic Activities. Molecules 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Q.; Qin, P. Transcriptome and Metabolome Combined to Analyze Quinoa Grain Quality Differences of Different Colors Cultivars. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Huang, T.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Qin, P. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of the Response of Quinoa Seedlings to Low Temperatures. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Kong, Z.; Huan, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, W.; Qin, P. Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Analyses of the Mechanism of Flavonoid Synthesis in Seeds of Differently Colored Quinoa Strains. Genomics 2022, 114, 138–148. [CrossRef]

- Chikida, N.N.; Razgonova, M.; Bekish, L.P.; Zakharenko, A.; Golokhvast, K. Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis Reveals Changes in Metabolome Profile in Triticosecale Seeds Based on Harvesting Time. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2023, 47, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Szajko, K.; Ciekot, J.; Wasilewicz-Flis, I.; Marczewski, W.; Soltys-Kalina, D. Transcriptional and Proteomic Insights into Phytotoxic Activity of Interspecific Potato Hybrids with Low Glycoalkaloid Contents. BMC Plant Biol 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Polyphenol and Flavonoid Profiles and Radical Scavenging Activity in Leafy Vegetable Amaranthus Gangeticus. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Diaz, J.M.; Sulyok, M.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Jouppila, K.; Nathanail, A. V Comparative Study of Mycotoxin Occurrence in Andean and Cereal Grains Cultivated in South America and North Europe. Food Control 2021, 130. [CrossRef]

- Al-Theyab, N.; Alrasheed, O.; Abuelizz, H.A.; Liang, M. Draft Genome Sequence of Potato Crop Bacterial Isolates and Nanoparticles-Intervention for the Induction of Secondary Metabolites Biosynthesis. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2023, 31, 783–794. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.V.B.; Milstead, M.; Thomas, O.; McGlasson, T.; Green, L.; Kreider, R.; Jones, R. Investigating Nutrient Intake during Use of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Nutr 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Akbar Ali, M.; Thripati, S. Computational Prediction for the Formation of Amides and Thioamides in the Gas Phase Interstellar Medium. Front Chem 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.Y.; Arju, G.; Nisamedtinov, I. Nitrogen Availability and Utilisation of Oligopeptides by Yeast in Industrial Scotch Grain Whisky Fermentation. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 2025, 83, 88–100. [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Muneer, F.; America, A.H.; Kuktaite, R. Polymeric Gluten Proteins as Climate-Resilient Markers of Quality: Can LC-MS/MS Provide Valuable Information about Spring Wheat Grown in Diverse Climates? J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 1844–1854. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Poursalehi, D.; Mohammadi, S.; Shahdadian, F.; Hajhashemy, Z.; Rouhani, P.; Mokhtari, E.; Saneei, P. Association between Mediterranean Diet and Metabolic Health Status among Adults Was Not Mediated through Serum Adropin Levels. BMC Public Health 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Zaccarelli, A.; Mattina, B.; Galindo-Luján, R.; Pont, L.; Benavente, F.; Zanotti, I.; Elviri, L. Comparative LC-MS Proteomics of Quinoa Grains: Evaluation of Bioactivity and Health Benefits by Combining In Silico Techniques With In Vitro Assays on Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2025, 69. [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Muneer, F.; America, A.H.; Kuktaite, R. Polymeric Gluten Proteins as Climate-Resilient Markers of Quality: Can LC-MS/MS Provide Valuable Information about Spring Wheat Grown in Diverse Climates? J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 1844–1854. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Geng, G.; Qiao, F.; Han, S. Integrated Metabolomics and Proteomics Analyses of the Grain-Filling Process and Differences in the Quality of Tibetan Hulless Barleys. Plants 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.-W.; Dawood, M.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.-H.; Wu, F. Differential Physiological and Proteomic Responses of Barley Genotypes to Sulfur Availability. Plant Growth Regul 2025, 105, 1591–1604. [CrossRef]

- Rusbjerg-Weberskov, C.E.; Foley, J.D.; Yang, L.; Terp, M.; Gregersen Echers, S.; Orlien, V.; Lübeck, M. Combined Rhizopus Oryzae Fermentation and Protein Extraction of Brewer’s Spent Grain Improves Protein Functionality. Food Bioproc Tech 2025, 18, 9574–9593. [CrossRef]

- Gregersen Echers, S.; Mikkelsen, R.K.; Abdul-Khalek, N.; Queiroz, L.S.; Hobley, T.J.; Schulz, B.L.; Overgaard, M.T.; Jacobsen, C.; Yesiltas, B. Residual Barley Proteins in Brewers’ Spent Grains: Quantitative Composition and Implications for Food Ingredient Applications. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2025, 106. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, B.; Yan, Y.; Liang, J.; Guan, X. Bound Polyphenols from Red Quinoa Prevailed over Free Polyphenols in Reducing Postprandial Blood Glucose Rises by Inhibiting α-Glucosidase Activity and Starch Digestion. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, X.; Shi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Ren, H.; Zhang, B. Proteomic Profiling Reveals Important Regulators of Photosynthate Accumulation in Wheat Leaves during Grain Development. BMC Plant Biol 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Alrosan, M.; al-Massad, M.; Obeidat, H.J.; Maghaydah, S.; Alu’datt, M.H.; Tan, T.-C.; Liao, Z.; Alboqai, O.; Ebqa’ai, M.; Dheyab, M.A.; et al. Fermentation-Induced Modifications to the Structural, Surface, and Functional Properties of Quinoa Proteins. Food Sci Biotechnol 2025, 34, 3317–3329. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.A.; Carrasco, C.; Romero-Soto, L.; Lundqvist, J.; Sundman, O.; Hedenström, M.; Gorzsás, A.; Broström, M.; Jönsson, L.J.; Martin, C. Sustainable Production of Exopolysaccharides from Quinoa Stalk Hydrolysates Using Halotolerant Bacillus Swezeyi: Fermentation Kinetics and Product Characterization. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2025, 19, 1326–1348. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, L.F.; Cheng, M.Y.; Ngoo, Y.T. Quality Management and Its Impact on Promoting Academics’ Innovation in Malaysian Higher Education. Asian Journal of University Education 2025, 21, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Garafonova, O.; Dvornyk, O.; Sharov, V.; Zhosan, H.; Yankovoi, R.; Lomachynska, I. Digitization Process in a Changing Global Environment. TEM Journal 2025, 14, 251–265. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.M.M.; Lechuga Sancho, M.P.L.; Szelągowski, M.; Medina-Garrido, J.A. Is User Perception the Key to Unlocking the Full Potential of Business Process Management Systems (BPMS)? Enhancing BPMS Efficacy Through User Perception. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing 2025, 37. [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, L.; Pöhnl, T.; Alhussein, M.; John, M.; Neugart, S. Changes in Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Three Amaranthus L. Genotypes from a Model to Household Processing. Food Chem 2023, 429. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Mu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, X.; Huang, R. Effects of Sodium Selenate on Energy Metabolism of Amaranth Inoculated with Glomus Mosseae Based on Targeted Metabolomics. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Cui, L.; Xiao, Q. Accumulation Patterns of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids in Different Colored Sweet Potato Flesh Revealed Based on Untargeted Metabolomics. Food Chem X 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Sarengaowa; Feng, K.; Li, Y.Z.; Long, Y.; Hu, W.Z. Effect of Alginate-Based Edible Coating Containing Thyme Essential Oil on Quality and Microbial Safety of Fresh-Cut Potatoes. Horticulturae 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, M.; Xia, X.; Zhu, Y. Improving Structural, Physical, and Sensitive Properties of Sodium Alginate–Purple Sweet Potato Peel Extracts Indicator Films by Varying Drying Temperature. Foods 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Karonen, M.; Pihlava, J.-M. Identification of Oxindoleacetic Acid Conjugates in Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Seeds by High-Resolution UHPLC-MS/MS. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Habinshuti, I.; Mu, T.-H.; Zhang, M. Ultrasound Microwave-Assisted Enzymatic Production and Characterisation of Antioxidant Peptides from Sweet Potato Protein. Ultrason Sonochem 2020, 69. [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, K.G.; Hernández-Rodriguez, L.; Lobato-Calleros, C.; Vernon-Carter, E.J.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C. Amaranth Protein-Cacao Pectin/Phenolic Extract Complex. ITALIAN JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE 2025, 37, 279–294. [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, S.; Balasubramanian, R.; Ambalavanan, N.; Subramanian, A.; Shalini, H.; Chandrasekaran, R. Antibacterial Effectiveness of Zinc Oxide and Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles Against Enterococcus Faecalis: An In Vitro Study. Journal of International Oral Health 2025, 17, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Si, F.; Lu, F.; Yang, L.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Li, G.; Lu, Z.-Q.; Lin, H.-X. Competitive Binding of Small Antagonistic Peptides to the OsER1 Receptor Optimizes Rice Panicle Architecture. Plant Commun 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Diowksz, A.; Pawłowska, P.; Kordialik-Bogacka, E.; Leszczynska, J. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Immunoreactivity of Oat Beers. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Cabezón, A.; García-Fandiño, R.; Piñeiro, A. MA(R/S)TINI 3: An Enhanced Coarse-Grained Force Field for Accurate Modeling of Cyclic Peptide Self-Assembly and Membrane Interactions. J Chem Theory Comput 2025, 21, 5724–5735. [CrossRef]

| Base de datos | Estrategia | Variables de búsqueda |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | Encapsulation and Andean Matrices | (“Bioencapsulation”) AND (“Andean grains) |

| Scopus | Proteomics, Functionality, and Fermentation Systems Applied to Andean Matrices | (“Proteomics”) AND (“Fermentation”) AND (“Andean grains”) |

| Matrix or Species | Type of Fermentation / Microorganism | Results | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranth and quinoa (flours) | Liquid sourdough fermentation with Weissella cibaria C43-11 and Lactobacillus plantarum ITM21B for 15 h. | High exopolysaccharide production (~20.79 g/kg at 250 DY); significant protein degradation (~51%); increase in organic acids and improved sourdough texture. | [18] |

| Sweet potato (slurry) | Submerged fermentation with various strains: B. coagulans, S. cerevisiae, L. plantarum, B. subtilis, B. breve, L. acidophilus. | 49 volatile compounds produced; B. coagulans yielded the richest ester profile and highest total acidity; aromatic profile shifted toward fermentative alcohols and aldehydes. | [19] |

| Grain mixture: wheat, oats, brown rice, barley, quinoa, lentils | Solid-state fermentation (SSF) with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 245. | Increased essential amino acids, higher amylase and protease activity, increased phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity after 36 h. | [20] |

| Quinoa (proteins) | Fermentation to obtain bioactive peptides with Lactobacillus paracasei CICC 20241. | 91 peptides identified; several showed ACE-inhibitory activity; IC50 between 40–80 μM for functional medium-chain peptides. | [21] |

| Sweet potato (protein gel) | Controlled fermentation prior to protein gel formation. | Improved color stability and anthocyanin retention against oxidation; efficiency increased to 87,27%. | [25] |

| Amaranth (proteins) | Fermentation to release enzyme-inhibitory peptides — Lactobacillus spp. | Increased peptides with inhibitory capacity IC50 = 0,47 mg/mL; peptide profiles associated with antioxidant and antihypertensive pathways. | [26] |

| Sweet potato, soybean, and agroindustrial residues | Fermentation with medicinal fungus Ganoderma lucidum. | Increased antioxidant compounds and bioactive polysaccharides in substrates: sweet potato and soybean residues at 11,43, 32,64, 40,19 μmol Trolox/100 g and 19,29, 17,7, 32,35 μmol Trolox/100 g, respectively. | [27] |

| Buckwheat + quinoa | Germination followed by co-fermentation (controlled co-fermentation). | Improved phenolic profile, increased antioxidants, and reduced antinutrients; tannin reduction: buckwheat 83%, quinoa 20%. | [28] |

| Moromi and shochu | Fermentation with temperature variation (technological reference). | Regulation of lactic acid kinetics and enzymatic activity; amino acids higher in moromi fermented at 38 °C, while shochu at 25 °C exhibited more fruity notes. | [31] |

| Saponins + fungi — fermentation optimization | Fermentation to degrade saponins with specialized fungi. | Reduced bitterness; kinetic parameters optimized secondary metabolites; potato concentration 97.3 mg/mL, glucose 20.6 mg/mL, pH 2.1 at 29.2 °C for 6 days. | [32] |

| Ulluco and arracacha | Fermentation as a process to intensify bioactive compounds. | Increased phenolic content and antioxidant capacity; transformation of structural carbohydrates; fiber content: ulluco 14%, xanthorrhiza 4.07%. | [33] |

| Matrix / System | Technology / Encapsulating Material | Results | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrot (phenolic extract) + Potato (protein matrix) | Potato protein–pectin coacervate; emulsification. | Average particle size ranged from 65.05–152.47 µm. Encapsulation efficiency (EE) increased (69.26–90.15%), while apparent retention (AR) decreased (53.90–102.16%) upon emulsification. | [36] |

| Starch hydrogels (model application) | High-pressure processed (HPP) starch hydrogels. | HPP starch hydrogels (600 MPa, 15 min) showed stable gelatinization. The extract affected color and released polyphenols in a controlled manner, confirmed by FT-IR and Franz diffusion. | [37] |

| Amaranth hydrolysates (peptides) | Alginate–pectin beads (ionic gel) | AG–PC beads showed increasing sizes with higher PC content. Encapsulation reached 95.57%. ACE-inhibitory activity reached 97.97% and was maintained after in vitro digestion. | [9] |

| Carrot (protein matrix: soy/potato) | Protein matrices + starch; film/spray-drying encapsulation. | Beads showed EE of 70.93–82.59% and sizes of 2.18–2.64 mm. 50% IPS–50% starch blends provided superior carotenoid protection, extending shelf life up to 106 days. | [38] |

| Potato (peptidic) — digestion / stability | Protein matrices and release systems. | Structures showed DPPH activity of 3–20%. Heated gels exhibited notable antioxidant capacity. | [43] |

| Quinoa (proteins) — emulsion gels | Quinoa protein-based emulsion gels. | QPH increased S₀ (p = 0.006) and emulsifying activity (p = 0.002), but reduced stability (p < 0.000). Water-holding capacity ≈ 70%. Hardness decreased (p < 0.000). Concentrations 0.5–2% formed well-defined 3D networks. | [39] |

| Sweet potato compounds (extracts) | Beads / alginate / ionic gelation; active films. | Encapsulation reached 60% carotenoids and 61–64% phenolics. Retention after 60 days: 43–59% under light/dark conditions. Degradation kinetics: k = 0.0149–0.0106 d⁻¹. | [40] |

| Ferulic acid (antioxidant) in quinoa (nanoformulation) | Quinoa protein + zein nanoparticles (antisolvent precipitation). | Quinoa prolamin showed higher EE (81.2%) and loading capacity (LC, 29.7%). Zein reached 70.7% EE and 18.5% LC. Enhanced gastric resistance and intestinal release of ferulic acid. | [41] |

| Anthocyanins (purple potato) | Spray-drying microencapsulation (quinoa starch / gum arabic). | Encapsulation achieved 86% EE, reduced degradation, and increased anthocyanin bioaccessibility by 20%, maintaining stability during storage and digestion. | [42] |

| Anthocyanins (maize + potato) | Microencapsulation in mixed matrices (starch/gum). | S. tuberosum CI50 = 0.070 mg/mL; minimum viability. Z. mays CI50 = 0.275 mg/mL; gradual reduction, slopes −41.83 vs. −7.32, respectively. | [44] |

| Extract (quinoa starch + tara gum) | Quinoa starch + tara encapsulation (spray/coacervation). | Capachu microcapsules contained 9.60 mg GAE/g phenolics, 211.40 mg C3G/g anthocyanins, 142.43 µmol/g DPPH, releasing 24.04 mg GAE/g. | [45] |

| Mashua (extracts) | Microencapsulation with modified Andean starches (OSA). | Optimized mashua extract (160 °C, 2% OSA) achieved higher EE, phenolics, and antioxidants, with low aw and hygroscopicity using pink oca OSA. | [46] |

| Native potato phenolics | Nanoencapsulation (spray-drying / nanoprecipitation) | Optimal encapsulation (120 °C, 141 L/h) yielded high EE, elevated DPPH, particle size 133–165 nm, negative ζ, low aw/moisture, and maximum release 9.86 mg GAE/g. | [47] |

| Quinoa bioactive peptides (applications) | Peptide formulation for stability and release (micro/nano). | Quinoa hydrolysates with chymotrypsin showed strong inhibition: CEase CI50 = 0.51 mg/mL; PL CI50 = 0.78 mg/mL; 4–12 active peptides identified. | [48] |

| Plant matrices with yeast (microencapsulation) | Microencapsulation using yeast particles + polysaccharide matrices. | YGP water showed 37.8% lower RR; acid/alkaline hydrolysis increased ARR 14.8–27.8%; organic solvents released more anthocyanins than control. | [49] |

| Edible coatings on fresh potato | Alginate + essential oils / chitosan. | Formulations F1–F2 increased chroma; F1–F4 elevated anthocyanins after 3 months (p < 0.05); alginate improved color, gloss, and sensory acceptability. | [50] |

| Composite films with microcapsules (potato) | Film-forming with microcapsules (alginate/biopolymer). | Microcapsules achieved 87% EE; film with 4.5% LM showed 46% antioxidant activity, improved stability, blocked UV, and extended blueberry freshness. | [51] |

| Jasmonate microcapsules (agro) | Microcapsules for post-harvest regulation. | MeJA 300 μmol/L was optimal; microcapsules with 2.5% alginate + 0.5% chitosan enhanced preservation using lower dose than solution. | [52] |

| Functional oil encapsulated in hydrocolloids | Oil-in-hydrocolloid microcapsules for product reformulation. | Encapsulated oil increased thermal diffusivity and reduced baking time, boosting productivity 17%; gluten-free cookies showed higher porosity and improved lipid profile. | [53] |

| Potato — response to encapsulating agents in culture | Encapsulation agents in culture stations. | Encapsulation with 4% alginate, 100 mM CaCl₂ and ½ MS achieved 99% conversion, 17% abscission, and rapid shoot development, optimizing micropropagation. | [54] |

| Active films based on amaranth | Active films (amaranth protein/hydrolysates + additives). | Glycerol increased EB to 12.19% and reduced TS to 1.12 MPa; 2% phenolics decreased EB and TS due to agglomeration. | [55] |

| Nanoencapsulation of potato compounds (various formulations) | Nano-/microencapsulation (spray / nanoemulsion). | At 116 °C and 15% encapsulant, higher phenolic retention, improved antioxidant capacity, and lower moisture and aw were achieved, outperforming 96 °C–25% conditions. | [56] |

| Industrial coatings and related technologies | Edible coatings and drying processes. | Coatings improved weight loss and firmness in RG and PM at 55±5% RH and 5±1 °C; inhibited sprouting under storage. | [57] |

| Fresh cut purple sweet potato. | Surface bioencapsulation with chitosan (Ch) and sodium alginate (SA) composite gel. | ChCSA coating reduced color change to ΔE = 8.97, versus Ch (16.86), SA+C (13.05) and control (22.90), forming a barrier limiting light and oxygen, preserving color for 12–18 days. | [58] |

| Gluten hydrolysate obtained with pancreatin | Spray-drying using maltodextrin, potato starch, and blends (30:70). | Higher aw (0.36), high encapsulation efficiency (85.79%), moisture 8.2%; increased solubility and density with more maltodextrin; spherical and rough microcapsules; improved antioxidant stability and controlled release under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. | [59] |

| Matrix or Species | Proteomic and Omics Technique | Results | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranth (seeds) | LC-MS (betalains). | LC-MS identified 30 betacyanins and 13 betaxanthins in A. cruentus with <5 ppm accuracy, confirming its value as a pigment source. | [63] |

| Potato (white vs. purple flesh) | Metabolomics + Transcriptomics (UHPLC-MS/MS + RNAseq). | UPLC-MS/MS identified 18 anthocyanins associated with 12 genes; St5GT showed strong overexpression in purple potato, confirming its key pigment role. | [64] |

| Quinoa (grains) | Comparative proteomics LC-MS/MS. | LC-MS/MS quantified 13 apoptotic biomarkers; 12 responded to quinoa proteins, showing increases similar to paclitaxel after 72 h. | [65] |

| Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) | Metabolomics (LC-MS). | LC-MS/MS identified 527 amino acids, 556 organic acids, and 39 lipids; CS showed more essential amino acids, ZS notable for succinic acid. | [66] |

| Potato leaves (field-grown) | Comparative proteomics. | LC-MS analyzed samples using 2 µL injection, 2.1×50 mm column, flow 0.5–0.8 mL/min, m/z range 70–1700, acquisition 4 scans/s. | [67] |

| Quinoa (seeds) | Saponin profiling (metabolomics). | 114 accessions evaluated; saponins ranged 0.22–15.04 mg/g; 75% were low; 12 oleanane saponins and one novel compound were identified. | [68] |

| Quinoa (seeds / seedlings) | Integrated metabolomics + transcriptomics. | 1060 metabolites and 13,095 differential genes detected; lipids and flavonoids predominated, highlighting hormonal signaling and AP2/ERF in response to high humidity. | [69] |

| Quinoa (cultivars) | Metabolomics (targeted / untargeted). | 154 flavonoids and 39,738 genes identified; 11 metabolites and 22 genes explained biosynthetic variation across four developmental stages. | [70] |

| Quinoa (extracts) | Peptidomic análisis. | pH 2 fraction showed 2,451 U/mL protease and strong antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activity against A549 and HeLa cells. | [71] |

| Potato leaves (toxin response) | Quantitative iTRAQ proteomics. | 693 differential proteins identified: 460 upregulated, 233 downregulated, highlighting changes in metabolic pathways and plant defense against taxtomin A. | [72] |

| Potato (Bulgarian cultivars) | Metabolomics (profiling). | Total phenolics ranged: flesh 318–636 mg/100 g, skin 2847–4120 mg/100 g; flavonoids: flesh 1.21–2.26 mg/100 g, skin 32.5–84.4 mg/100 g. | [73] |

| Quinoa (colored varieties) | Non-targeted metabolomics (LC-MS). | 689 compounds identified; 251, 182, and 317 varied among groups. Notable: 22 flavonoids, 5 phenolic acids, and 1 differential betacyanin. | [74] |

| Quinoa (phenolics) | Spectrometry and chromatography (HPLC-MS) | 430 polyphenols identified; 121, 116, and 148 differential. Black quinoa had 643.68 mg/100 g phenolics; white quinoa IC50: 3.97 and 1.08 mg/mL. | [75] |

| Quinoa (colors / cultivars) | Metabolome + transcriptome. | Four cultivars showed distinct profiles; 6 enriched pathways; multiple amino acids, tannins, lipids, and alkaloids varied significantly among analyzed grains. | [76] |

| Quinoa (seeds/seedlings) | Transcriptomics and metabolomics (low-temperature stress). | Two quinoa variants evaluated at -2, 5, and 22 °C; 794 metabolites and 52,845 genes detected, including 6,628 novel. | [77] |

| Quinoa (flavonoids) | Integrated omics (transcriptomics + metabolomics). | Black, red, yellow, and white quinoa seeds analyzed; 90 flavonoids detected, 18 key metabolites, 25 regulatory genes identified. | [78] |

| Triticale / comparative cereal | Metabolomics (harvest / temporal changes). | Triticosecale ‘Bilinda’ showed 93 polyphenolic compounds, including 9 flavones, 7 flavonols, 2 flavan-3-ols, 5 hydroxybenzoic acids, and 4 carotenoids. | [79] |

| Potato (Snakin2 study) | Proteomics / functional (biochemistry). | RNAi7: COMT and CAD 5–10×, Prx10 maximum; OE27: minor changes; peroxidase, COMT, CAD activities ↑; StSN2 interacts with Prx2, Prx9, Prx10. | [62] |

| Potato hybrids (field) | Integrated proteomics + transcriptomics. | High α-solasonine and α-solamargine; SBT1.7 X2 and subtilisin protease ↑; carbonic anhydrase and miraculin ↓; endo-1,3-β-glucanase 47.96× higher. | [80] |

| Amaranth (polyphenols / flavonoids) | Metabolomics (profiling). | LS7 showed maxima: provitamin A 2–3×, high vitamin C, total phenolics and flavonoids elevated; antioxidant capacity (DPPH/ABTS) higher; LS9 slightly lower. | [81] |

| Cereals and Andean grains (oats, barley, quinoa QMM and QKU) | LC-MS/MS (mycotoxin metabolomics). | European cereals contained Fusarium mycotoxins —HT2, MON, NIV— in >50% samples, with INFE and non-specific metabolites (CTO, CDP-Tyr, CDP-Val, EMO, ENC). Andean grains: quinoa QMM showed low toxic load except some Fusarium and Alternaria mycotoxins; QKU had high non-specific metabolites AsG (89), AsP (90), and NBP (97). | [82] |

| Potato (bacterial isolates Priestia megaterium) | Oxford Nanopore genomic sequencing, bioinformatic annotation, and optimized MS/MS. | AuNPs increased metabolites of 254–270 Da depending on concentration, confirmed by genomic data and biosynthetic profiles of the isolate. | [83] |

| Matrix or Species | Method or Approach | Results | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinoa (red) | Enzymatic assays (α-glucosidase inhibition), phenolic analysis (HPLC). | Red quinoa BPE IC₅₀ α-glucosidase 10.295 mg/mL, higher antioxidant activity (DPPH/ABTS), delayed starch digestion, reduced postprandial glucose at 50 mg/kg. | [95] |

| Amaranth (grain/leaves) | Metabolomic profiling (LC-MS), bioactive compound analysis. | Caffeic and glucaric acids increased 2.9–5.2 % after cooking; domestic oxidation reduced phenolics 22–60 %; buns decreased TPC by up to 60 %. | [102] |

| Amaranth inoculated with Glomus (rhizosphere) | Targeted metabolomics. | PCA: PC1 explained 49.65 %; PC1+PC2 75.06 %; OPLS-DA clearly discriminated control vs treated; metabolites mainly affected energy metabolism pathways. | [103] |

| Sweet potato (varieties) | Untargeted metabolomics (UHPLC-MS) | 4,447 secondary metabolites identified; CS vs BS: 1,540, ZS vs BS: 1,949, ZS vs CS: 1,931; 20 flavonoids and 13 common phenolic acids. | [104] |

| Potato (functional coatings) | Evaluation of edible coatings + quality assays (firmness, color, microbial). | AEC-TEO 0.05 % increased L to 10.55, firmness to 8.24 N, reduced browning 4.19, decreased microbes 1.21–3.63 log CFU/g. | [105] |

| Sweet potato (indicator films) | Development of indicator films (sensory/colorimetric). | Optimal temperature 30 °C: elongation 98.46 %, tensile strength 95.73, ΔE and permeability decreased, excellent pH and NH₃ sensitivity, lighter color. | [106] |

| Quinoa (phytohormones / auxins) | Chemical-metabolomic analysis of auxins and derivatives. | 14 new oxindoleacetates identified in quinoa via UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS and UHPLC-QOrbitrap-MS/MS, present in conventional and organic crops. | [107] |

| Sweet potato (post-fermentation) | Fermentation studies and functional measurements (antioxidants, volatiles). | Fermented sweet potato: pH 3.28–5.95; sugars ↓; protein ↑; phenolics ↑ (A. niger); amino acids +64.83% (B. coagulans); lactic acid ↑; improved flavor. | [19] |

| Sweet potato (varieties by color) | Comparative nutrient and metabolomic profiling. | Metabolomic analysis of sweet potatoes: 527 amino acids, 556 organic acids, 39 lipids; CS had higher essential amino acids; ZS characterized by succinic acid. | [66] |

| Potato (encapsulated phenolics) | Micro/nanoencapsulation and functional activity assays. | Optimization of nanoencapsulation of native potato phenolic extracts: 120 °C, 141 L/h; nanocapsules 133–165 nm, maximum release 9.86 mg GAE/g. | [47] |

| Quinoa (peptides) | Isolation and characterization of bioactive peptides; molecular docking. | Chymotrypsin-derived bioactive peptides showed CI₅₀ of 0.51 mg/mL (CEase) and 0.78 mg/mL (PL); 4 CEase-inhibitory and 12 PL-inhibitory peptides identified, suggesting natural antihypercholesterolemic potential. | [48] |

| Amaranth (bioactive films) | Development of films incorporating extracts/hydrolysates; functional testing. | Glycerol at 0.37–1 % increased EB (12.19 % to 2.20 %), while 2 % phenolic compounds significantly decreased EB and TS. | [55] |

| Quinoa (auxins / bioactivity) | Auxin analysis and functional evaluation. | 14 new oxindoleacetate conjugates identified in quinoa seeds via UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS and UHPLC-QOrbitrap-MS/MS using methanol/water and acetone/water. | [107] |

| Potato (conservation via coatings) | Storage assays with edible coatings and quality measurements. | Edible coatings significantly improved the chroma of red potatoes; F1 and F2 notable, while F1 and F4 increased anthocyanins at 3 months. | [50] |

| Sweet potato (peptides via sonication) | Ultrasound + enzymatic hydrolysis; peptide characterization. | Ultrasonic hydrolysis generated <3 kDa peptides with high antioxidant activity, Fe²⁺ chelation, OH radical scavenging, and elevated ORAC values. | [108] |

| Tubers (encapsulation evaluation) | Encapsulation studies and functional assays | Encapsulation of sweet potato nodal segments with 4 % alginate, 100 mM CaCl₂, and ½ MS accelerated shoots, roots, growth, and genetic conservation. | [54] |

| Amaranth (protein) + cocoa pectin + phenolic extract | Coacervate complexes (AP: CP 2:1 and 5:1), phenolic extract (0–0.5% w/v), ζ-potential, FTIR, SEM. | ζ-potential near 0 mV (−1.8 to +0.9 mV); coacervation yield increased 35–48% depending on AP: CP ratio; antioxidant activity increased 20–45% with 0.5 % PE; more porous structures confirmed by SEM. | [109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).