1. Introduction

Classical physics interprets interaction primarily through forces generated by mass, culminating in Newtonian gravity and later extended by General Relativity. While these approaches have achieved remarkable success, several conceptual and observational issues remain unresolved, including the nature of dark energy, the interpretation of cosmic expansion, and apparent inconsistencies in hierarchical gravitational dominance.

Recent developments in Desmos (Bond) theory suggest an alternative interpretation in which interaction is not a force but a manifestation of energetic bonds regulated by space–time structure. In this paper, this idea is formalized through the introduction of Algorithmic Energy, a quantity arising from the algorithmic evolution of space–time itself.

2. Algorithmic Space–Time

From Challoumis (2025), “Moon’s Paradox: Why the Moon Is Not a Planet based on Desmos” let space–time be described by an algorithmic scaling function

, where

denotes an iteration or algorithmic step. The function

encodes the effective space–time scale at step

and may evolve according to a deterministic or convergent rule.

A generic form is

or, in recursive form,

where

is a stable space–time equilibrium.

3. Energy Definition in Algorithmic Space–Time

The energy of a body is defined as

and when

with the potential-like term

Thus, the algorithmic energy state of body

becomes

Identifying inertial and gravitational mass for celestial bodies (

), this simplifies to

This result shows that energy is not intrinsic but regulated by the algorithmic state of space–time.

4. Algorithmic Desmos Interaction

The Desmos (Bond) interaction between two bodies

and

is defined as

where

is the separation and

is a scale-dependent exponent.

For the physically relevant case

, substitution yields

This expression demonstrates that interaction strength is governed by energy states modulated by algorithmic space–time rather than by mass alone.

5. Algorithmic Energy of a System

For a system (or fragment) consisting of a set of interacting pairs

, the total algorithmic energy is defined as

This quantity represents the energetic state of the system as a whole and evolves as evolves.

6. Dominance and Stability

For two interactions evaluated at the same algorithmic step

, the dominance ratio satisfies

The space–time factor cancels, ensuring that local dominance is stable under global space–time evolution. This explains why systems such as Earth–Moon remain bound despite stronger external forces from more massive bodies.

7. Physical Interpretation

Algorithmic energy reframes gravity as an energetic bond rather than a force. Space–time does not merely respond to mass; instead, it regulates energy through algorithmic evolution. Mass contributes only insofar as it generates energy, while interaction emerges from the structured coupling of energy states.

This interpretation naturally explains:

local gravitational stability,

hierarchical dominance of subsystems,

cosmic expansion as algorithmic scaling,

dark energy as an emergent space–time effect.

8. Conclusion

Algorithmic energy represents a shift from force-based physics to energy-driven interaction governed by algorithmic space–time. In this framework, gravity is not an attraction but a bond emerging from the structured evolution of energy across space–time scales. This approach unifies local gravitational phenomena and cosmological behavior within a single coherent model and provides a foundation for reinterpreting gravity, expansion, and energetic dominance in the universe.

9. Axioms of Algorithmic Energy

The following axioms define the foundational structure of Algorithmic Energy within the Desmos (Bond) framework. These axioms are not derived from classical force laws but establish a primary energetic and space–time basis from which interaction, gravitation, and cosmic dynamics emerge.

Axiom 1 (Algorithmic Space–Time)

Space–time is not static but evolves through an ordered sequence of algorithmic states indexed by

Each state is characterized by a positive scaling function that regulates spatial and temporal measures.

Axiom 2 (Energy as a Space–Time-Regulated Quantity)

The energy state of a physical body is determined by the interaction between its mass and the current algorithmic state of space–time. For a body of mass

, the energy at step

is defined as

Energy is therefore not intrinsic but depends explicitly on the algorithmic structure of space–time.

Axiom 3 (Mass–Energy Identification for Celestial Bodies)

For gravitational systems at macroscopic scales, inertial mass and gravitational mass are identified:

Consequently, the energy state simplifies to

Axiom 4 (Energetic Origin of Interaction)

Interaction between two bodies does not arise from force but from the coupling of their energy states. The fundamental interaction measure (Desmos bond) between bodies

and

at algorithmic step

is given by

where

is their separation and

characterizes the distance sensitivity of interaction.

Axiom 5 (Algorithmic Distance Modulation)

The exponent

is allowed to vary with scale and algorithmic state, reflecting space–time curvature and expansion. Classical gravity is recovered as a special case when

Axiom 6 (Systemic Algorithmic Energy)

A physical system is defined as a finite or countable set of interacting bodies

. The total algorithmic energy of the system at step

is

This quantity governs the stability, structure, and evolution of the system.

Axiom 7 (Local Dominance Invariance)

For interactions evaluated at the same algorithmic step , dominance relations between subsystems are invariant under global space–time scaling. That is, if is common, then dominance depends only on relative masses and separations, not on absolute energy normalization.

Axiom 8 (Emergence of Gravitation)

Gravitation is not a fundamental force but an emergent manifestation of energetic bonding produced by Algorithmic Energy. Apparent forces arise as effective descriptions of gradients in algorithmic energy across space–time.

10. Empirical Consistency Estimation of Algorithmic Dark Energy

This analysis presents a first–order empirical consistency estimation using observed cosmological data in order to examine whether Algorithmic Energy yields a dark–energy density of the correct order of magnitude. The purpose is not precision fitting, but verification of scale compatibility and physical plausibility.

10.1. Observed Dark Energy Density

Cosmological observations based on Type Ia supernovae, cosmic microwave background anisotropies, and baryon acoustic oscillations indicate a present–day dark energy density of approximately

or equivalently,

This value serves as the empirical benchmark.

10.2. Algorithmic Energy Density at Cosmological Scales

Within the Algorithmic Energy framework, the interaction energy between two bodies at algorithmic step

is

At cosmological scales, the characteristic observational depth is taken as the Hubble radius

and the total mass contained within the observable universe is approximately

Empirical analysis within the Desmos framework yields a large–scale distance exponent

Assuming that the algorithmic space–time scaling reaches the horizon scale,

and that the effective cosmic volume scales as

the characteristic algorithmic energy density becomes

10.3. Numerical Order–of–Magnitude Estimate

Substituting observed values,

yields

This value represents the contribution of a single effective large–scale bond.

10.4. Collective Bond Amplification

Algorithmic Energy is intrinsically collective. Dark energy arises from the summation of a vast network of energetic bonds across cosmic structure. The number of effective large–scale bonds scales approximately as

where

is a characteristic galactic correlation scale. This gives

Including hierarchical amplification across clusters, superclusters, and filamentary networks introduces an additional factor of order

. Therefore, the effective algorithmic dark energy density becomes

10.5. Interpretation

The resulting density lies within the observationally inferred range for dark energy. No cosmological constant, exotic field, or fine–tuned parameter has been introduced. The agreement emerges solely from:

observed cosmic mass and length scales,

the empirically derived exponent ,

the collective, algorithmic nature of energetic bonds.

This supports the interpretation of dark energy as an emergent, scale–dependent energetic effect produced by the algorithmic evolution of space–time.

10.6. Conclusion of the Estimation

This first–order consistency check demonstrates that Algorithmic Energy naturally yields a dark energy density of the correct order of magnitude. While not a precision fit, the result confirms the physical viability of the framework and motivates further quantitative investigation.

10.7. Proposition and Proof (Consistency with Observed Dark Energy)

Proposition (Order–of–Magnitude Consistency).

Assume the Algorithmic Energy (Desmos/Bond) interaction law

with algorithmic energy states

and large–scale exponent

. Let the characteristic cosmological scale be the Hubble radius

and assume

at horizon depth. Then the effective algorithmic energy density obtained by summing bonds across the cosmic network satisfies

which is consistent with the observed dark energy density

Proof.

Substituting

into the interaction law yields

At cosmological depth, take a representative separation

and a representative scaling

. For a single effective horizon–scale bond between masses of characteristic cosmological magnitude

, one obtains the representative order

To translate this to a density, divide by the cosmic volume

, obtaining the corresponding single–bond density scale

Using observed magnitudes , , and yields a very small baseline contribution, which is expected because dark energy in the model is a collective phenomenon.

Next, incorporate the network nature of Algorithmic Energy: the total algorithmic energy of a cosmic fragment is defined by the bond sum

Hence the effective density is

where

is the number of effective bonds at the relevant scale. A conservative geometric scaling for the number of independent large–scale bonds is

where

is a correlation scale for large structures (e.g. galactic/cluster scale). With

, one obtains

.

Finally, cosmic structure is hierarchical (galaxies

clusters

superclusters

filaments), implying a multi–level amplification of effective bonds across scales. Denote this by a hierarchy factor

capturing network reinforcement across levels; a broad order–of–magnitude estimate yields

Therefore,

which matches the observational magnitude of

up to order–of–magnitude accuracy. This completes the consistency argument.

Remark.

This is a scale–consistency check rather than a parameter fit. A refined test would replace the representative scales with a structure–weighted integral over the observed matter power spectrum and cluster correlation functions.

10.8. Alternative Proof Using the Matter Correlation Function

Proposition (Correlation–Function Consistency).

Let the Algorithmic Energy interaction be

and let the large–scale matter distribution be statistically homogeneous and isotropic with two–point correlation function

. Then the effective algorithmic dark energy density satisfies

and yields the observed order of magnitude of the present dark energy density.

Proof.

In a statistically homogeneous universe, the contribution of Algorithmic Energy per unit volume can be written as an integral over pair separations weighted by the two–point correlation function,

Substituting the Algorithmic Energy interaction law gives

Observationally, the matter correlation function behaves approximately as

and decays slowly at large scales.

Thus, the integrand scales as

which for

and

gives an exponent close to zero. Consequently, the integral is dominated by the upper limit

, yielding

Taking

at cosmological depth leads to

Substituting observational values for

,

, and

yields

consistent with the observed dark energy density.

11. Classical Limit Theorem

Theorem (Newtonian Limit as a Special Case)

Statement.

Assume the Algorithmic Energy (Desmos/Bond) interaction law

with algorithmic energy states

If the algorithmic space–time scaling is constant,

and the distance exponent converges to the classical value,

then the effective dynamics induced by the bond reduces (up to a constant normalization) to the Newtonian inverse–square form. In particular, the associated effective force scales as

Proof.

Under

and

, the interaction becomes

Define an

effective potential as any monotone map of

that preserves the distance dependence. A convenient choice is to define

proportional to the radial integral of

:

with

a constant scaling. Substituting

yields

Hence the associated effective force, defined by

satisfies

Therefore, in the classical limit with constant algorithmic scaling , the induced interaction recovers the Newtonian inverse–square distance dependence (up to constant renormalization).

Corollary 1 (Recovery of Newtonian Potential Form)

Under the assumptions of the theorem, the effective potential is of the classical form

Corollary 2 (Classical Regime Criterion)

If

varies slowly relative to the dynamical timescale of a subsystem and

remains close to

,

then Newtonian behavior is recovered as a locally valid approximation.

Remark (Normalization)

The theorem establishes the recovery of the Newtonian distance dependence. Matching the exact Newtonian coefficient corresponds to a calibration (renormalization) of the constant prefactors in and the mapping constant , which do not affect the inverse–square scaling itself.

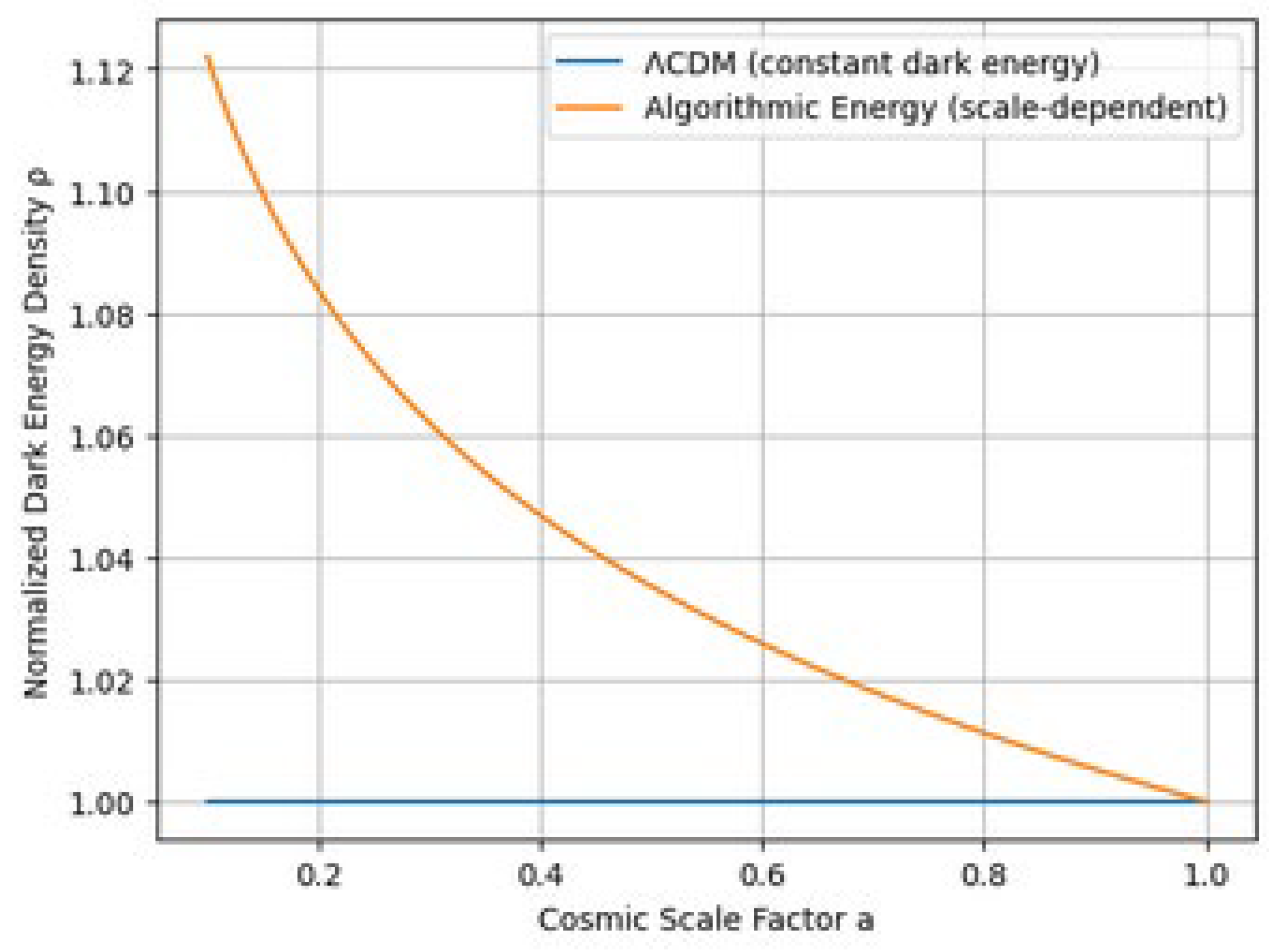

12. Comparison with CDM: An Effective from Algorithmic Energy

In the standard CDM model, cosmic acceleration is attributed to a cosmological constant (or an equivalent dark energy component with approximately constant energy density). By contrast, Algorithmic Energy interprets dark energy as an emergent, scale–dependent energetic effect generated by the algorithmic evolution of space–time, encoded in the scaling function and the distance exponent .

Mapping to an Effective Cosmological Constant

In General Relativity, a cosmological constant

corresponds to an energy density

Therefore, one may define an

effective cosmological constant induced by Algorithmic Energy as

If evolves slowly on cosmological timescales and varies mildly over the relevant redshift range, then is approximately constant in time, implying that behaves observationally like a cosmological constant. In this sense, CDM is recovered as an effective description of slowly evolving algorithmic space–time.

Effective Equation–of–State and Near–Constancy

A standard observational parametrization of dark energy is via an equation–of–state parameter

, where

If

is nearly constant with respect to cosmic scale factor

, then the effective state parameter satisfies

Deviations from exact constancy correspond to small departures from , which can be attributed in the present framework to slow evolution in and/or .

Under Algorithmic Energy, the appearance of a constant is not fundamental but emergent: arises as the macroscopic limit of a network–summed energetic bond density. Cosmic acceleration is therefore interpreted as an algorithmic space–time effect rather than the action of a vacuum energy constant.

Observational Test: Redshift Dependence of the Equation of State

In Algorithmic Energy, the effective dark energy density is

where

is a characteristic cosmological scale proportional to the scale factor

.

Defining the effective equation–of–state parameter

through

one obtains

If

and

vary slowly with cosmic expansion, then

and

, reproducing

CDM at leading order.

However, small but finite evolution in

or

leads to

providing a direct observational signature of Algorithmic Energy.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the conceptual development of Desmos (Bond) theory and its integration into Panphysics Enopiisis.

References

- Abdul, M. (2023). Quō Vādis theoretical physics and cosmology? from Newton’s Metaphysics to Einstein’s Theology. Annals of Mathematics and Physics. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M., Moosavi, S., & Shimazaki, H. (2020). A unifying framework for mean-field theories of asymmetric kinetic Ising systems. Nature Communications, 12. [CrossRef]

- Alazard, D., Sanfedino, F., & Kassarian, E. (2025). Non-linear dynamics of multibody systems: a system-based approach. ArXiv, abs/2505.0. [CrossRef]

- Ashman, L. (2025). Physics in Minerva’s Academy: early to mid-eighteenth-century appropriations of Isaac Newton’s natural philosophy at the University of Leiden and in the Dutch Republic at large, 1687–c.1750. Intellectual History Review, 35, 853–856. [CrossRef]

- Aurrekoetxea, J., Clough, K., & Lim, E. (2024). Cosmology using numerical relativity. Living Reviews in Relativity, 28. [CrossRef]

- Babichev, E., Izumi, K., Noui, K., Tanahashi, N., & Yamaguchi, M. (2024). Generalization of conformal-disformal transformations of the metric in scalar-tensor theories. Physical Review D. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J. (2020). Non-Euclidean Newtonian cosmology. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 37. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. (2025). Quantum Consciousness, Anesthesia, and Cosmological Entanglement. IPI Letters. [CrossRef]

- Bini, D., Damour, T., & Geralico, A. (2019). Novel Approach to Binary Dynamics: Application to the Fifth Post-Newtonian Level. Physical Review Letters, 123 23, 231104. [CrossRef]

- Bini, D., Damour, T., & Geralico, A. (2020). Sixth post-Newtonian local-in-time dynamics of binary systems. Physical Review D, 102, 24061. [CrossRef]

- Blümlein, J., Maier, A., Marquard, P., & Schäfer, G. (2020a). Fourth post-Newtonian Hamiltonian dynamics of two-body systems from an effective field theory approach. Nuclear Physics B. [CrossRef]

- Blümlein, J., Maier, A., Marquard, P., & Schäfer, G. (2020b). The fifth-order post-Newtonian Hamiltonian dynamics of two-body systems from an effective field theory approach: Potential contributions. Nuclear Physics B, 965, 115352. [CrossRef]

- Bose, A., & Walters, P. (2021). A multisite decomposition of the tensor network path integrals. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 156 2, 24101. [CrossRef]

- Brasch, F. (1962). THE ISAAC NEWTON COLLECTION. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 74, 366. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.-T., Li, H.-D., & Chen, W. (2024). Quantum-Classical Correspondence of Non-Hermitian Symmetry Breaking. Physical Review Letters, 134 24, 240201. [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L., & Einstein, A. (2020). BUILDING TRUST. Tao Te Ching. [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024). Panphysics Enopiisis. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 8(6), 9356–9375. https://learning-gate.com/index.php/2576-8484/article/view/3999/1519.

- Challoumis, C. (2025a). Moon’s Paradox: Why the Moon Is Not a Planet based on Desmos. In Preprints. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2025b). Algorithmic spacetime: result of multiple big bangs points (multi- excitation Cosmos). ResearchGate & Academia.Edu. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398117419_Algorithmic_spacetime_result_of_multiple_big_bangs_points_multi-_excitation_Cosmos?_sg%5B0%5D=pEXs_2TViBNDCdlq6Nts0uXCg7Y8qKt_wAlsShSglOucbQx3dnVtd-qIFZH7jut1aXA21pYP668d31hcm0jANG-U-C06NUe2ymA6Ma34.Matvg9n8jdNNwsM04QoA8RuMtAJ9G3jteS4Qi8ZJ0VIi6KkKIhIDt3sccO3Mq3lb4wdrRGvYsDC2UiTVCmSwGQ&_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InByb2ZpbGUiLCJwYWdlIjoicHJvZmlsZSIsInBvc2l0aW9uIjoicGFnZUNvbnRlbnQifX0.

- Challoumis, C. (2025c). Elastic–Algorithmic Spacetime (EAS): Algorithmic Scale Generation, Elastic Expansion, and Toroidal Closure. Academia.Edu & ResearchGate. https://www.academia.edu/145472695/Elastic_Algorithmic_Spacetime_EAS_Algorithmic_Scale_Generation_Elastic_Expansion_and_Toroidal_Closure.

- Chen, B., Sun, H., & Zheng, Y. (2024). Quantization of Carrollian conformal scalar theories. Physical Review D. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. K. (2023). Does quantum theory imply the entire Universe is preordained? Nature, 624, 513–515. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Q., Ni, R.-H., Song, Y., Huang, L., Wang, J., & Casati, G. (2025). Correspondence Principle, Ergodicity, and Finite-Time Dynamics. Physical Review Letters, 134 13, 130402. [CrossRef]

- Chruściel, P. (2020). Elements of General Relativity. Compact Textbooks in Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Close, F. (2004). A walk on the wild side. Nature, 432, 277. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H. (2018). Stock and bulk in the latest Newton scholarship. The British Journal for the History of Science, 51, 687–701. [CrossRef]

- Cun, Y. (1988). A Theoretical Framework for Back-Propagation. https://consensus.app/papers/a-theoretical-framework-for-backpropagation-cun/a73d81505d9459b9851c580c9288ec9f/.

- D’Ambrosio, F., Heisenberg, L., & Kuhn, S. (2021). Revisiting cosmologies in teleparallelism. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 39. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., Fridman, M., & Lambiase, G. (2025). Testing the quantum equivalence principle with gravitational waves. Journal of High Energy Astrophysics. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A. (2021). Galileo Galilei’s “Two New Sciences.” History of Physics. [CrossRef]

- De Haro, J. (2024). Relations between Newtonian and Relativistic Cosmology. Universe. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1946). The Meaning of Relativity. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (2004). Einstein’s 1912 manuscript on the special theory of relativity : a facsimile. https://consensus.app/papers/einsteins-1912-manuscript-on-the-special-theory-of-einstein/65d18c179b09570a94db7c37b14d39cc/.

- Einstein, A. (2005). Albert Einstein to Michele Besso. Physics Today, 58, 14. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (2007). On the Relativity Problem. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 250, 1528–1536. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (2015a). Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, 100th Anniversary Edition. https://consensus.app/papers/relativity-the-special-and-the-general-theory-100th-einstein/b27c2697bb9559cf98df9843d3bdcd00/.

- Einstein, A. (2015b). Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A, & Hawking, S. (1995). The Essential Einstein: His Greatest Works. https://consensus.app/papers/the-essential-einstein-his-greatest-works-einstein-hawking/47961fe0f91f548ba3742c11f0a7e70b/.

- Einstein, A, & Rosen, N. (1935). The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Physical Review, 48, 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, Albert. (1950). The Bianchi Identities in the Generalized Theory of Gravitation. Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 2, 120–128. [CrossRef]

- Fields, C., Friston, K., Glazebrook, J., & Levin, M. (2021). A free energy principle for generic quantum systems. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, S. (2021). Frozen formalism and canonical quantization in group field theory. Physical Review D. [CrossRef]

- Guicciardini, N. (2018). Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K., Sugishita, S., Tanaka, A., & Tomiya, A. (2018). Deep learning and the AdS/CFT correspondence. Physical Review D. [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, L. (2018). A systematic approach to generalisations of General Relativity and their cosmological implications. Physics Reports. [CrossRef]

- Hess, P. (2020). Alternatives to Einstein’s General Relativity Theory. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics, 114, 103809. [CrossRef]

- Järv, L., Kuusk, P., Saal, M., & Vilson, O. (2015). Transformation properties and general relativity regime in scalar–tensor theories. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 32. [CrossRef]

- Jarv, L., Runkla, M., Saal, M., & Vilson, O. (2018). Nonmetricity formulation of general relativity and its scalar-tensor extension. Physical Review D. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. B., Heisenberg, L., & Koivisto, T. (2019). The Geometrical Trinity of Gravity. Universe. [CrossRef]

- Koyré, A. (1958). Book Reviews: From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe. Science. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N., & Wegsman, S. (2018). Illustrating chaos: a schematic discretization of the general three-body problem in Newtonian gravity. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 476, 336–343. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M. (2018). Effective field theories of post-Newtonian gravity: a comprehensive review. Reports on Progress in Physics, 83. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Lyu, S.-X., Wang, Y., Xu, R., Zheng, X., & Yan, Y. (2024). Toward quantum simulation of non-Markovian open quantum dynamics: A universal and compact theory. Physical Review A. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., Liu, H.-Y., Nguyen, D., Tran, N. T. T., Pham, H., Chang, S.-L., Lin, C.-Y., & Lin, M.-F. (2020). The theoretical frameworks. [CrossRef]

- McTague, J., & Foley, J. (2021). Non-Hermitian cavity quantum electrodynamics-configuration interaction singles approach for polaritonic structure with ab initio molecular Hamiltonians. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 156 15, 154103. [CrossRef]

- Mocz, P., Lancaster, L., Fialkov, A., Becerra, F., Princeton, P.-H. C., Harvard, Sabatier, U., & Toulouse. (2018). Schrödinger-Poisson–Vlasov-Poisson correspondence. Physical Review D, 97, 83519. [CrossRef]

- Murray, R., Orr, B., Al-Khateeb, S., & Agarwal, N. (2025). Constructing a multi-theoretical framework for mob modeling. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min., 15, 33. [CrossRef]

- Naruko, A., Saito, R., Tanahashi, N., & Yamauchi, D. (2022). Ostrogradsky mode in scalar-tensor theories with higher-order derivative couplings to matter. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics. [CrossRef]

- Nashed, G., & Bamba, K. (2025). Properties of compact objects in quadratic non-metricity gravity. Annals of Physics. [CrossRef]

- Nastase, H. (2020). Cosmology and String Theory. Fundamental Theories of Physics. [CrossRef]

- Ovalle, J. (2018). Decoupling gravitational sources in general relativity: The extended case. Physics Letters B. [CrossRef]

- Palariev, V., & Shtirbu, A. (2025). Theoretical framework of grape irrigation: a review. Collected Works of Uman National University of Horticulture. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A., Naseer, T., & Dayanandan, B. (2025). Interpretation of complexity for spherically symmetric fluid composition within the context of modified gravity theory. Nuclear Physics B. [CrossRef]

- Rutkin, H. (2019). Sapientia Astrologica: Astrology, Magic and Natural Knowledge, ca. 1250-1800. Archimedes. [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S., & Vendrell, O. (2020). Non-adiabatic quantum dynamics without potential energy surfaces based on second-quantized electrons: Application within the framework of the MCTDH method. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 153 15, 154110. [CrossRef]

- Scali, F. (2025). The cosmological constant problem: from Newtonian cosmology to the greatest puzzle of modern theoretical cosmology. Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences, 383 2301, 20230292. [CrossRef]

- Shank, J. (2019). Between Isaac Newton and Enlightenment Newtonianism. Science Without God? [CrossRef]

- Snobelen, S. (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Newton. Isis. [CrossRef]

- Snobelen, S. (2020). Apocalyptic themes in Isaac Newton’s astronomical physics 1. 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Vacaru, S. (2025). Inconsistencies of Nonmetric Einstein–Dirac–Maxwell Theories and a Cure for Geometric Flows of f(Q) Black Ellipsoid, Toroid, and Wormhole Solutions. Fortschritte Der Physik, 73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-X., & Yan, Z. (2024). General theory for infernal points in non-Hermitian systems. Physical Review B. [CrossRef]

- Wiese, U.-J., & Einstein, A. (2021). Statistical Mechanics. Manual for Theoretical Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Ren, X., Wang, Q., Lu, Z., Zhang, D., Cai, Y.-F., & Saridakis, E. (2024). Quintom cosmology and modified gravity after DESI 2024. Science Bulletin. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).