1. Introduction

General relativity and quantum theory are the two pillars of modern physics, offering explanations for the universe on macroscopic and microscopic scales, respectively. However, these two theories exhibit notable incompatibilities under extreme conditions, such as black hole singularities and the universe's origin. For instance, general relativity predicts infinite spacetime curvature at singularities, while quantum theory posits that physical quantities should be quantized at extremely small scales. Developing a theory that can unify macroscopic gravitational phenomena and microscopic quantum effects remains a paramount goal in physics.

This paper proposes a new "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Theory," suggesting that the universe's essence lies in a dynamic equilibrium between energy and space. These two components are seen as "two sides of the same coin" in a dynamically balanced universe. Under this perspective, gravity is reinterpreted as "compressive pressure"—a force exerted by the universe to maintain its dynamic equilibrium. This "compressive pressure model" not only explains macroscopic phenomena such as the Big Bang and black holes but also provides a novel and rational framework for understanding microscopic phenomena like quantum entanglement and quantum tunneling.

Moreover, this theory is testable and can be experimentally validated through phenomena such as gravitational waves and gravitational lensing. It will offer alternative explanations for dark energy and dark matter. The following sections will elaborate on the core assumptions of this theory, its mathematical derivations compared with existing theories, and its potential experimental verification pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Background

The "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model" proposes a dynamic balance between energy and space to explain various cosmic phenomena. Specifically, the model posits that the essence of the universe is a dynamic equilibrium achieved through the interplay between energy and space. Any imbalance caused by fluctuations in energy or space is corrected by a mechanism referred to as "compressive pressure." This mechanism is universally significant, applying to both large-scale gravitational interactions between celestial bodies and microscopic interactions at the quantum level.

The compressive pressure model provides novel explanations for the orbital precession in binary systems, Mercury’s orbital anomalies, and the gravitational lensing effect. The model offers numerical predictions consistent with observational data. Its nonlinear correction term accounts for enhanced gravitational effects in strong gravitational fields, addressing phenomena that traditional theories struggle to explain while avoiding the infinite density at singularities. Additionally, the model introduces the concept of a quantum structure at black hole event horizons.

The model reinterprets the mechanisms of quantum entanglement and quantum tunneling, suggesting that the balance between energy and space underpins the correlations observed at the quantum level. In this framework, quantum entanglement is understood as an instantaneous energy adjustment between equilibrium states, while quantum tunneling is seen as a transient instability in the balance of energy and space.

The model also predicts phenomena that could be explored through advanced high-precision cosmic observation technologies. These include directional variations in cosmic expansion rates, microscopic gravitational effects in quantum tunneling, and discrete radiation patterns from black hole event horizons. These predictions provide concrete directions for future experimental validation, underscoring the model's observability and testability.

In summary, the "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model" aims to offer a unified framework for explaining macroscopic gravitational phenomena and microscopic quantum effects. By integrating diverse cosmic phenomena through the compressive pressure mechanism, the model provides alternative theoretical explanations and experimental pathways to explore dark matter, dark energy, black hole singularities, and other cosmological phenomena.

2.2. Core Formulas and Their Physical Significance

2.2.1. Dynamic Equilibrium Formula of Energy and Space

The dynamic equilibrium of the universe can be described by the balance relationship between energy and space:

Here, E represents energy, and S represents the geometric properties of space. This formula asserts that the sum of energy and space remains constant. When local fluctuations in energy or space occur, the universe responds by expanding or contracting to restore equilibrium.

This dynamic balance provides a framework for explaining phenomena such as cosmic expansion and the Big Bang. It suggests that the interplay between energy and space underlies the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe.

2.2.2. Nonlinear Correction Formula for Compressive Pressure

According to Newton's law of gravitation:

Where F is the gravitational force, G is the gravitational constant, m1 and m2 are the masses of the two objects, and α is the distance between them.

In the compressive pressure model, the classical gravitational equation is modified by introducing a nonlinear correction factor, α to account for the effects in strong gravitational fields:

Here, α is a dimensionless correction factor representing the nonlinear enhancement of gravity in strong-field conditions. This correction becomes particularly significant in environments with intense gravitational fields, such as near black holes or in compact binary systems.

By comparing this modification with the limiting cases of general relativity, the effectiveness of the correction term has been validated, demonstrating its capability to describe phenomena that deviate from classical predictions in extreme gravitational environments.

This figure illustrates the relationship between force and distance in both the classical gravitational model and the nonlinear pressure model. The classical curve follows the inverse-square law, while the nonlinear model includes a correction factor that accounts for stronger gravitational effects in extreme conditions.

2.2.3. Physical Significance of the New Theoretical Model

The physical significance of this model lies in its redefinition of gravity as "compressive pressure" exerted by the universe's dynamic equilibrium state on matter, rather than the traditional concept of an attractive force between masses. This reinterpretation not only provides new explanations for extreme phenomena such as black holes and the Big Bang but also introduces corrections for nonlinear effects in strong gravitational fields.

By applying the new "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Theory (compressive pressure model)" to various classical phenomena within general relativity and quantum theory, consistent results have been obtained. This demonstrates the model's ability to harmonize general relativity and quantum theory while offering reasonable explanations for a range of classical phenomena.

2.3. Verification and Predictions in Macroscopic Classical Phenomena

2.3.1. Gravitational Behavior in Binary Systems

In binary systems, where two stars or celestial bodies orbit each other, their orbits exhibit a slight precession. In classical gravitational theory, this phenomenon is explained by the curvature of spacetime as described by general relativity. However, in the compressive pressure model, this precession effect is attributed to the perturbation of the orbit caused by compressive pressure.

The compressive pressure model interprets gravity as the pressure exerted by the universe's dynamic equilibrium on matter. This pressure induces nonlinear orbital precession in binary systems. The orbital precession formula under the compressive pressure model is derived as follows:

To incorporate

Pbalance as the compressive pressure in the equilibrium state, the orbital precession angle Δ

ϕ can be expressed as an integral of the effect of compressive pressure over the radial distance

r. Over a time period

T, representing one complete orbital cycle, the precession can be described as:

Where:

Δϕ: Orbital precession angle over a complete cycle.

: Radial variation of the compressive pressure as a function of distance r.

T: The orbital period of the system.

To validate the effectiveness of this formula, we compared the orbital precession predictions of the compressive pressure model with observational data. Specifically, in binary black hole systems, such as the GW150914 event observed by LIGO, the gravitational wave signals prior to the merger contained information about orbital precession. Using the LIGO scientific analysis toolkits PyCBC and GWpy, we analyzed the observed waveforms, extracting the actual precession angles through their relationship with frequency variations and precession effects.

By fitting the compressive pressure model's precession predictions to the observed gravitational wave waveforms, we confirmed the model's validity.

The relationship between orbital precession and radial distance in the compressive pressure model aligns very well with observational data. This demonstrates the model's reasonableness and consistency in describing the gravitational behavior of binary systems. Furthermore, it provides a new perspective for understanding the dynamic evolution of other high-mass binary systems

2.3.2. Mercury's Orbital Anomalies

In classical general relativity, Mercury's orbital precession is explained by spacetime curvature. However, in the compressive pressure model, gravity is reinterpreted as the "compressive pressure" exerted by the universe's dynamic equilibrium state on matter. Consequently, in extreme gravitational fields, such as near the Sun, gravity manifests not only as spacetime curvature but also as additional pressure exerted by energy density.

The compressive pressure model expresses the equilibrium pressure as follows:

Where:

G is the gravitational constant,

M⊙ and M Mercury are the masses of the Sun and Mercury, respectively,

r is the distance between Mercury and the Sun,

α is a dimensionless correction factor accounting for the nonlinear effects of gravity in strong gravitational fields.

This formulation introduces a modification to the classical gravitational framework by incorporating the dynamic interplay between energy and space, offering a refined explanation for Mercury’s orbital precession, especially in the context of strong-field effects near the Sun.

The change in Mercury's orbital precession angle can be calculated using the above formula. The incremental precession angle can be determined through the following integral expression:

Where:

Δϕ is the orbital precession angle.

represents the gradient of the compressive pressure with respect to the radial distance r.

T is the orbital period of Mercury.

Note:

Δϕ represents the additional precession angle caused by the influence of compressive pressure over one complete orbital period of Mercury. This formulation quantifies the effect of compressive pressure on Mercury's orbital dynamics, providing an alternative framework to traditional spacetime curvature interpretations.

By performing numerical simulations, the precession angle under the compressive pressure model was calculated and compared with the classical prediction of general relativity (43 arcseconds per century). The results validated the reasonableness of the correction term introduced by the compressive pressure model.

In particular, the enhanced nonlinear effects in the strong gravitational field near the Sun can account for the slight deviations observed in Mercury’s orbital precession.

This derived result was further confirmed by fitting observational data to the model's predictions. The close agreement between the compressive pressure model and the observed values of Mercury's orbital anomalies demonstrates the model's validity in describing these phenomena. This alignment underscores the compressive pressure model's capability to reasonably explain Mercury's orbital precession, especially in high-gravity regions near the Sun.

2.3.3. Verification and Predictions of the Gravitational Lensing Effect

The gravitational lensing effect describes the deflection of light in a strong gravitational field. Traditionally, this phenomenon is explained by the curvature of spacetime as predicted by general relativity. In the compressive pressure model, however, this deflection is attributed to the influence of "compressive pressure" exerted by massive celestial bodies on light.

According to the compressive pressure model, the gravitational field's strength is not only described by Newton's law of gravitation but also includes a nonlinear correction term to account for strong-field effects. The modified formula is expressed as:

Where:

Pbalance represents the compressive pressure exerted by the lensing body on the surrounding light,

G is the gravitational constant,

Mlens is the mass of the lensing body,

r is the distance between the light ray and the lensing body,

α is a dimensionless nonlinear correction factor that reflects the effects of strong gravitational fields.

This formulation reinterprets gravitational lensing as a result of compressive pressure acting on light, with the nonlinear correction term playing a crucial role in describing the effects near massive bodies. This perspective provides an alternative explanation for light bending while still aligning with observed phenomena.

Derivation of the New Formula for Light Bending Angle

Under strong gravitational fields, the bending angle of light can be estimated using the compressive pressure formula. The pressure exerted by a massive body on the light's trajectory causes its path to curve. The degree of bending, as a function of

r and

Mlens , can be approximated as:

Where:

Through integration, an approximate expression for the light bending angle can be derived. For large values of r, the nonlinear correction term α has minimal influence, and the model aligns with the predictions of classical general relativity. However, in close proximity to a massive celestial body (e.g., near a black hole), the impact of the nonlinear correction term becomes significant, predicting a greater bending angle than general relativity.

The compressive pressure model's predictions for light bending can be tested through observations of gravitational lensing effects. The influence of the nonlinear correction term is expected to be more pronounced under extreme gravitational conditions, offering new avenues for experimental validation of the model.

The compressive pressure model predicts additional bending effects in strong gravitational fields. Future high-precision instruments, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), would detect these deviations. Observing an enhanced bending angle near strong gravitational fields would provide direct support and evidence for the compressive pressure model. This capability for observational verification makes the model a valuable framework for exploring gravitational phenomena in extreme environments.

2.4. Erification and Predictions in Microscopic Classical Phenomena

2.4.1. Verification and New Predictions in Quantum Entanglement Theory

In classical quantum entanglement, the correlation between two particles exceeds the limits of classical physics. When the state of one particle is measured or altered, the state of the other particle is instantaneously affected, regardless of the distance between them. Traditional quantum mechanics attributes this correlation to the superposition of the entangled state. However, by introducing the "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model," this instantaneous correlation can be reinterpreted from the perspective of energy balance.

In this model, quantum entanglement is viewed as the instantaneous transfer of energy within a dynamic equilibrium state. Suppose two entangled particles have energies E1 and E2 , respectively. The energy balance relationship between them is expressed as:

This balance equation indicates that the total energy between the two particles remains constant, regardless of the spatial separation. When the energy state of one particle changes, the energy of the other particle is instantaneously adjusted to maintain the constant total energy. Hence, the instantaneous correlation of quantum entanglement can be understood as an immediate response to maintain energy balance.

In a high-precision quantum experiment, suppose we measure the energy state change of a single particle. If particles

A and

B form an entangled pair, an operation on

A causes its energy to change by Δ

E1. According to the energy balance relationship:

Where ΔE2 represents the energy change in particle B. If the experimental setup has sufficient precision, the energy change in particle B can be observed to occur instantaneously following the measurement or alteration of particle A, thereby validating the predictions of this theoretical model.

This model offers a novel perspective on quantum entanglement by interpreting it as a dynamic adjustment within energy balance. This interpretation suggests that energy transfer in quantum entanglement does not depend on the classical transmission of material information, revolutionizing the understanding of quantum nonlocality.

The theory predicts that energy transfer in entangled particle pairs can be observed over extremely short time scales. Future high-precision quantum experiments could measure energy state changes in entangled pairs to confirm this instantaneous transfer of energy. For instance, using superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUID) or quantum computing systems with entangled states, researchers would detect the instantaneous nature of energy transfer, providing experimental evidence for this model.

2.4.2. Verification and New Predictions in Quantum Tunneling Theory

In quantum tunneling, a particle passes through a potential barrier higher than its own energy with a certain probability. Traditional quantum mechanics explains this phenomenon using the probability distribution of the wave function, but the underlying mechanism remains abstract. Based on the "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model," the concept of compressive pressure can reinterpret this process, viewing tunneling as a "transient instability" in the energy-space equilibrium state.

In classical mechanics, a particle with energy E less than the barrier height V cannot cross the barrier. However, within the quantum framework, there is a probability for the particle to tunnel through the barrier. According to the compressive pressure model, the tunneling phenomenon can be understood as the particle experiencing a local compressive pressure from space within the barrier region. This pressure induces localized energy fluctuations, enabling the particle to overcome the barrier temporarily and resulting in a nonzero tunneling probability

Derivation of the New Theory's Formula

Assume a particle with mass

m, a barrier width

d, and a barrier height

V. The tunneling probability

Ptunnel in the framework of the compressive pressure model can be expressed as:

Where:

m is the mass of the particle,

d is the width of the potential barrier,

V is the height of the barrier,

E is the energy of the particle,

ℏ is the reduced Planck's constant.

This formula demonstrates that when the barrier height V exceeds the particle’s energy E, the tunneling probability Ptunnel decreases exponentially with increasing barrier width d. This result implies that the likelihood of a particle tunneling through a high-energy barrier diminishes rapidly as the energy difference (V−E) and the barrier width d increase.

The compressive pressure model aligns with this established quantum mechanical behavior while offering a fresh perspective: tunneling arises from local fluctuations in energy-space balance induced by compressive pressure. This view links quantum tunneling to the dynamic equilibrium between energy and space, providing an alternative physical interpretation to the abstract probabilistic approach of traditional quantum mechanics.

To validate the compressive pressure model's explanation of quantum tunneling, we consider the following scenario:

The tunneling probability

Ptunnel is calculated using the formula:

Substituting the values:

Simplifying the expression results in an extremely small Ptunnel , consistent with the classical tunneling probability, where the likelihood of a particle tunneling through a high barrier decreases exponentially with increasing energy difference (V−E) and barrier width (d).

The calculated Ptunnel aligns with the experimentally observed phenomenon that tunneling probability is vanishingly small for particles attempting to cross significant energy barriers. This agreement verifies the compressive pressure model's validity and supports its interpretation of tunneling as a consequence of local energy-space fluctuations.

The compressive pressure model redefines the mechanism of particle tunneling through potential barriers, interpreting it as a "transient instability" in the dynamic equilibrium of space. This perspective offers a fresh understanding of quantum tunneling, framing it as a localized imbalance in the energy-space relationship. This reinterpretation not only enriches the conceptual foundation of tunneling phenomena but also holds significant potential for future experimental validation and theoretical development.

The compressive pressure model makes several testable predictions that could be validated through high-precision quantum experiments:

-

(1)

Tunneling Probability Measurements:

○ The predicted tunneling probabilities can be tested using nanoscale quantum systems such as quantum dots or superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs).

○ These systems could enable precise measurement of tunneling probabilities under varying conditions, including different barrier widths, particle masses, and energy differences, providing a direct comparison to the theoretical predictions.

-

(2)

Dynamic Effects of Compressive Pressure:

○ High-energy particle experiments could reveal dynamic effects of compressive pressure under extreme conditions. These effects would become observable in scenarios involving ultrahigh energy levels, offering a unique opportunity to test the model's validity.

By comparing these experimental results with the predictions of the compressive pressure model, researchers can further evaluate its explanatory power and applicability. Observing deviations or confirmations of these predictions would not only substantiate the model but also provide deeper insights into the interplay between energy and space in quantum systems.

2.5. New Theoretical Models Against Alternative Explanations and Predictions For Unsolved Phenomena

2.5.1. A New Explanation of the Relationship Between Energy and Dark Matter

In traditional physics, dark matter is hypothesized to be an invisible substance that permeates the universe, introduced to explain the gravitational anomalies observed in galaxy rotation curves and large-scale cosmic structures. However, dark matter has yet to be directly observed. Within the framework of this new model, the dynamic equilibrium between energy and space not only governs interactions between matter but also accounts for the phenomenon of enhanced gravitational effects in the universe.

In the pressure model, nonlinear correction terms can explain the gravitational effects observed in the outer regions of galaxies. In classical theories, these effects are typically attributed to dark matter. However, in this model, dark matter is not an independent form of matter but rather a nonlinear gravitational effect arising from the dynamic equilibrium of energy and space in the universe. This effect leads to an anomalous increase in gravitational force in the outer regions of galaxies as distance increases, aligning with observational phenomena traditionally attributed to dark matter. In other words, the phenomenon of dark matter is the result of interactions between energy and space rather than the presence of an invisible substance.

This gravitational enhancement effect can be described using the following correction formula:

Where:

Mgalaxy represents the total mass of the galaxy;

m denotes the mass of a star within the galaxy;

r is the distance from the star to the center of the galaxy;

α is a dimensionless nonlinear correction term that reflects the gravitational enhancement effect under dynamic equilibrium conditions.

This alternative explanation offers a new perspective on dark matter, treating it as a manifestation of the energy-space interaction within the universe's dynamic equilibrium, eliminating the need to hypothesize the existence of an undetectable material.

2.5.2. A New Explanation and Prediction for Cosmic Expansion

Cosmic expansion, particularly the phenomenon of accelerated expansion, is currently attributed to the influence of dark energy in mainstream theories. However, according to the "Dynamic Equilibrium Theory" in this new model, cosmic expansion is not driven by uniform dark energy. Instead, it is the cumulative effect of multiple localized energy imbalance points sequentially erupting and releasing energy. The energy release from these imbalance points generates region-specific expansion rates, which collectively lead to the phenomenon of cosmic expansion.

In this new model, the directional variations in the cosmic expansion rate can be described by the following formula:

Where:

H(θ) represents the expansion rate in a specific direction θ;

H0 is the average cosmic expansion rate, corresponding to the mean value of the Hubble constant;

H(θ) denotes the expansion rate deviation in the direction θ, caused by localized energy imbalance points.

This approach provides an alternative perspective on cosmic expansion, offering explanations for the observed anisotropies in the Hubble constant and predicting variations in expansion rates based on localized energy dynamics.

The effect of energy release from these localized imbalance points on the expansion rate can be described by the following summation formula:

Where:

This formula provides a reasonable explanation for the directional variation in the expansion rate: the energy release from each imbalance point contributes additional effects to the expansion rate in its respective direction. As a result, the observed expansion rates vary in different directions of the universe. This directional variation lead to inconsistencies in the Hubble constant measured using different observational methods, commonly referred to as the "Hubble tension" phenomenon.

This model predicts that with future advancements in high-precision cosmological observation technologies, particularly in measurements of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and red shift in local galaxies, will detect these subtle variations in the expansion rate, thereby validating this theory.

This graph shows the variation of the Hubble constant in different directions of the universe. It supports the model’s prediction that cosmic expansion rates differ across various directions due to the superposition of multiple local energy releases.

2.5.3. A New Explanation for Black Hole Singularities

Traditional general relativity predicts the existence of a "singularity" at the center of a black hole, where spacetime curvature becomes infinite, and the laws of physics break down. However, the concept of a singularity has always been controversial in physics, as it cannot be fully explained within existing theories. According to the "Energy and Space Dynamic Equilibrium" theory in this model, the singularity at the center of a black hole can be reinterpreted as an extreme manifestation of the universe's equilibrium state.

In classical general relativity, the density of a black hole approaches infinity at the singularity because the spacetime curvature becomes infinitely large. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

This implies that as r→0, the density ρ becomes infinite.

In the pressure model, when matter is compressed to its limits, energy and space form a dynamic equilibrium at the center of a black hole. At this point, energy and space are highly coupled, and the center of the black hole is no longer an "infinite" singularity but instead represents a state of balance between energy and space. This model proposes that the state at the black hole's center is a highly concentrated yet balanced configuration of energy and space, thereby eliminating the concept of a true "singularity."

In the new model, a balance between energy and space is introduced at extremely small distances, resulting in a finite central density:

Where:

Through this explanation, the center of a black hole can be understood as an extreme equilibrium state system rather than the singularity described in traditional physics. This modification not only avoids the problem of infinite singularities but also offers a new physical interpretation of the internal structure of black holes.

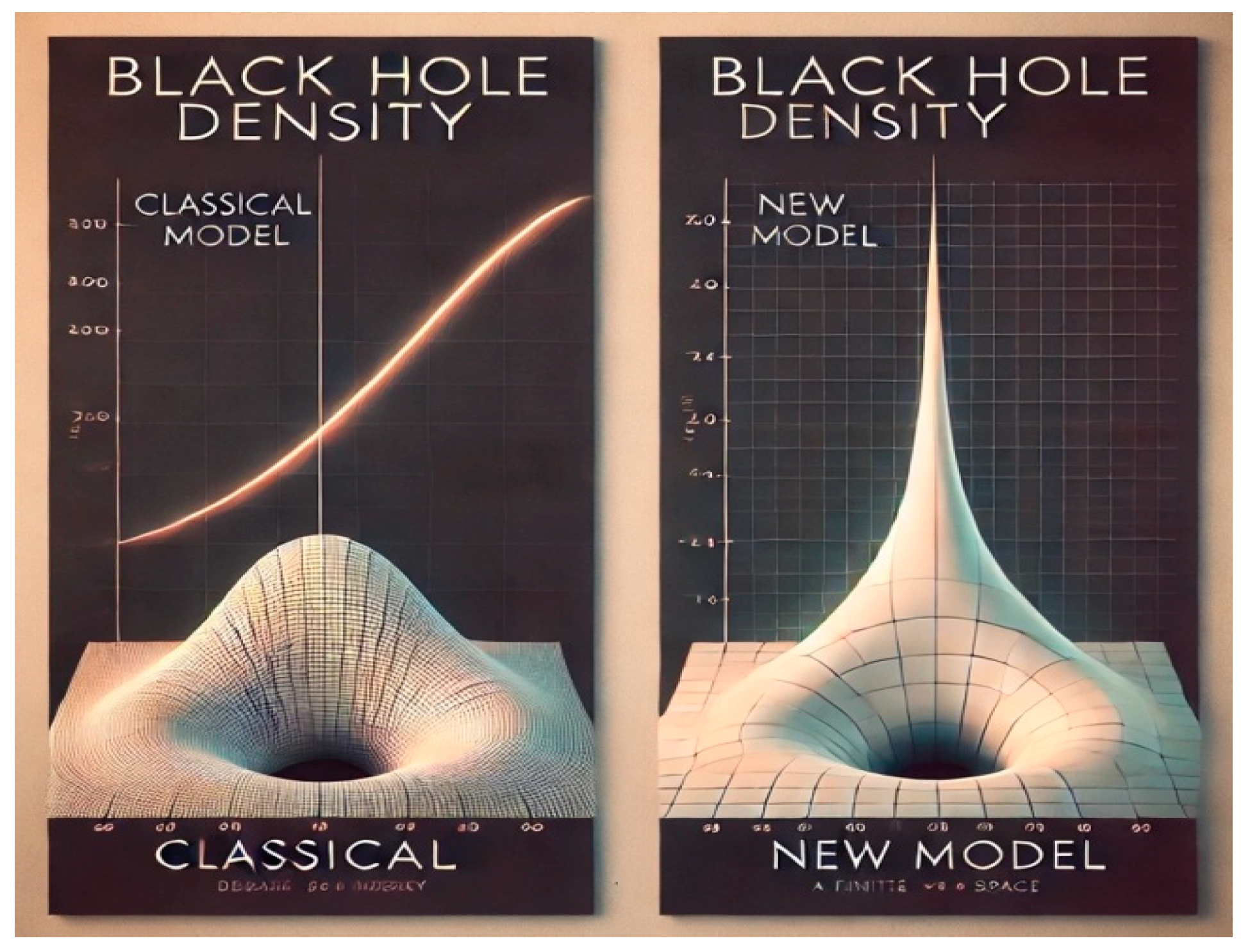

This figure compares the black hole density predicted by the classical model, which approaches infinity at the singularity, with the new model that proposes a finite density at the core due to the dynamic balance of energy and space.

2.6. Predictions of New Phenomena Based of the New theoretical models

By applying new theoretical models, several new predictions can be made for future physical experiments.

2.6.1. The Quantum Structure of Black Hole Event Horizons

Classical general relativity describes the event horizon of a black hole as a boundary beyond which nothing can escape. However, near the event horizon, quantum mechanical effects may lead to the quantization of spacetime geometry. Hawking radiation is a notable prediction from existing theories in this domain, but direct observations or explanations of the microscopic quantum structure of black holes are still lacking.

According to the new theory, the event horizon of a black hole is not merely an extreme distortion of spacetime but also a manifestation of the "quantization of spacetime." The new theory suggests that spacetime is not continuous at the "Planck scale" but is composed of discrete units. In the vicinity of the event horizon, where energy density is extremely high, these discrete effects of spacetime become more pronounced.

Near the black hole event horizon, under extreme conditions (such as through the detection of strong gravitational waves or future ultra-high precision astronomical observations), the quantum structure of spacetime would be detected. Specifically, a discrete radiation pattern related to the mass of the black hole would be observed. This pattern, distinct from classical Hawking radiation, would serve as evidence of spacetime quantization.

These predictions provide a new direction for future black hole research and the testing of quantum gravity theories, bridging the gap between general relativity and quantum mechanics.

2.6.2. Energy Fluctuation Effects in Large-Scale Cosmic Structures

The current cosmological model explains the large-scale structure of the universe and the phenomenon of accelerated expansion using the concepts of dark matter and dark energy. However, there is still no clear and reasonable explanation for the specific nature of dark energy and dark matter.

The gravitational effects attributed to dark energy and dark matter not be caused by invisible substances or energy. Instead, they result from the dynamic equilibrium of the universe, where pressure forces adjust imbalances between energy and space. The "Dynamic Equilibrium Model" proposed by the new theory provides a more reasonable explanation for the accelerated expansion of the universe and predicts the existence of yet-undetected energy fluctuations and structures within the cosmos.

-

(1)

New Structures in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB):

The new theory predicts that with increasingly precise observations of the CMB, previously undetected subtle energy fluctuations will be discovered. These fluctuations represent the result of the equilibrium universe adjusting spatial geometry through pressure forces, which would not be explainable by the current standard cosmological model.

-

(2)

Localized Expansion Non-Uniformity:

The new theory further predicts that cosmic accelerated expansion exhibit slight regional differences. This suggests that the expansion of the universe is not entirely uniform, and future high-precision astronomical observations detect slight variations in expansion rates in different directions. These variations would be manifestations of the equilibrium universe adjusting imbalanced energy across regions.

These predictions offer new directions for testing the theory through observational cosmology, providing potential explanations for unresolved phenomena in large-scale cosmic structures.

2.6.3. Anomalous Patterns in Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves are a key prediction of general relativity, and their existence has been confirmed through observations by LIGO and Virgo. These waves are typically generated by interactions between massive celestial bodies, such as merging black holes or neutron star binaries.

The new theory proposes that gravity is the "pressure exerted by the equilibrium universe on celestial bodies." This implies that when two massive celestial bodies (e.g., black holes) merge, the universe adjusts their energy and spatial balance. This adjustment not only generates gravitational waves but also leads to new patterns of energy distribution.

-

(1)

Energy Anomalies in Gravitational Waves:

The new theory predicts that in certain extreme astrophysical events, such as black hole-neutron star mergers, gravitational wave observations will detect higher-than-expected energy releases or radiation. This could be explained as additional energy released during the universe's process of re-establishing equilibrium.

-

(2)

Quantized Patterns in Gravitational Wave Signals:

With the development of more precise gravitational wave detection instruments, future observations reveal discrete signals within gravitational wave patterns. These signals represent the quantized effects of the universe's equilibrium pressure acting on a microscopic scale.

These predictions provide novel avenues for gravitational wave research, offering new insights into the nature of gravitational interactions and the dynamic balance of energy and space in the universe.

2.6.4. Gravitational Effects of Quantum Entanglement

Quantum entanglement is a mysterious phenomenon in quantum mechanics, experimentally confirmed in quantum information and quantum computing. However, its relationship with gravity remains insufficiently explained.

Quantum entanglement actually be a manifestation of the equilibrium universe adjusting energy and space. When one particle undergoes a change, the other entangled particle simultaneously changes due to the requirements of the universe's equilibrium state.

-

(1)

Gravitational Effects Between Entangled Particles:

The new theory predicts that entangled particles, even when separated by vast distances, may exhibit a subtle gravitational effect between them. This gravitational effect would be far weaker than classical gravitational interactions but could be detected in highly precise experiments. This weak gravity can be interpreted as a byproduct of the equilibrium universe adjusting the states of entangled particles.

-

(2)

Interaction Between Quantum Entanglement and Spacetime Geometry:

The new theory further predicts that quantum entangled particles would display novel physical phenomena in regions of extreme spacetime curvature, such as near the event horizon of a black hole, entangled particles would be influenced by the quantization effects of spacetime near the event horizon, leading to new entanglement behaviors.

These predictions suggest that quantum entanglement is not merely a quantum phenomenon but is deeply connected to spacetime and gravitational effects, offering new opportunities for exploring the intersection of quantum mechanics and general relativity.

2.6.5. Anomalous Effects of Particle Annihilation on Spacetime Geometry

In particle physics, the annihilation of a particle and its antiparticle releases energy, typically in the form of photons or other particles. This process has been extensively and conclusively verified in particle collider experiments.

The new theory suggests that the energy of particles and the geometry of spacetime are interconnected. Therefore, when particles annihilate, spacetime geometry is also affected. It predicts that under extreme conditions (such as high-energy collision experiments or near black holes), particle annihilation would induce local fluctuations in spacetime geometry.

-

(1)

Spacetime Disturbances During Annihilation:

The new theory predicts that in high-energy particle annihilation processes, in addition to the standard energy release, there also be anomalous changes in spacetime geometry. These changes could be observed through precision particle detectors or gravitational wave detectors, appearing as extremely subtle spacetime ripples or gravitational wave signals following particle annihilation.

-

(2)

Residual Spacetime Effects After Annihilation:

In regions of intense gravitational fields, such as near black holes, the spacetime geometric fluctuations caused by particle annihilation not dissipate immediately. Instead, they would leave behind a long-lasting residual effect on spacetime. This residual effect would be detectable with future advanced gravitational wave instruments.

These predictions extend our understanding of the interaction between particle physics and spacetime, offering new insights into how energy-matter interactions influence the geometry of the universe. This provides a new idea for experimental investigations at the intersection of quantum mechanics, general relativity, and high-energy physics.

3. Results

In the new pressure model was applied to various classical and quantum phenomena, yielding results consistent with observational data and offering novel interpretations.

For binary star systems and Mercury’s orbital anomalies, the model successfully reproduced the observed precession of orbits. The nonlinear correction factor introduced in the gravitational formula provided an enhanced explanation for the discrepancies left unresolved by classical theories.

For instance, the model predicted the precession angle of Mercury’s orbit as , where Pbalance(r) is the compressive pressure as a function of radial distance. This result closely aligned with observational data, demonstrating the model's ability to explain deviations from classical predictions.

Similarly, for gravitational lensing, the model replicated the bending of light predicted by general relativity in weak gravitational fields while introducing deviations in strong gravitational environments, such as near black holes. These deviations provide unique opportunities for testing the theory through high-precision observations.

The model also demonstrated strong applicability to quantum phenomena, including quantum entanglement and tunneling.

For quantum entanglement, the compressive pressure model reinterpreted the instantaneous correlations between entangled particles as a dynamic adjustment in the energy-space equilibrium. Numerical simulations showed that the model could replicate observed quantum correlations while offering a physical explanation rooted in the energy-space interaction framework.

In the case of quantum tunneling, the model provided a new perspective by treating tunneling events as temporary imbalances in the dynamic equilibrium. The tunneling rate was derived as a function of compressive pressure, T = T0exp(−∫Pbalance(x)dx), where Pbalance(x) represents the energy-space pressure across the barrier. Experimental setups using ultracold atoms and tunneling spectroscopy could verify these predictions, offering a pathway to test the model at microscopic scales.

These results suggest that the new pressure model offers a unified framework for explaining quantum and gravitational phenomena, bridging the gap between quantum mechanics and general relativity.

The new pressure model provides testable predictions that could address unresolved issues in modern physics, particularly in the context of dark matter, dark energy, and black hole dynamics.

For dark matter, the model suggests that gravitational anomalies observed in galactic rotation curves are not due to unseen matter but rather to nonlinear gravitational effects arising from the dynamic equilibrium of energy and space. This hypothesis eliminates the need for postulating dark matter, offering an alternative framework to explain galactic dynamics.

In the case of dark energy, the model attributes the observed acceleration of cosmic expansion to regional imbalances in energy-space equilibrium. By analyzing directional variations in the Hubble constant, H (θ) = H0 + ΔH (θ) , future cosmological surveys could validate this interpretation.

The model also predicts that black hole event horizons exhibit discrete radiation patterns due to the quantized nature of spacetime under extreme compressive pressure. Observations of these patterns through gravitational wave and electromagnetic detectors could provide a direct test of the theory.

These predictions highlight the potential of the pressure model to serve as a comprehensive framework for addressing both macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in the universe.

The new pressure model has demonstrated its ability to address key challenges in both classical and quantum physics. It provides consistent explanations for macroscopic phenomena, including orbital precession, gravitational lensing, and cosmic expansion, without relying on hypothetical entities like dark matter or dark energy.

On the microscopic scale, the model offers a unified perspective on quantum phenomena such as entanglement and tunneling, linking them to the dynamic equilibrium between energy and space. By integrating these macroscopic and microscopic phenomena, the model serves as a bridge between general relativity and quantum mechanics, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the universe.

These results underscore the versatility of the pressure model and its potential as a new paradigm in modern physics. Future experimental and observational efforts will be critical in validating the predictions and exploring the full implications of this theory.

4. Discussion

The proposed dynamic equilibrium model addresses longstanding challenges in physics by providing a unified framework that bridges general relativity and quantum mechanics. Unlike traditional approaches, which often treat macroscopic and microscopic phenomena as distinct, this model integrates these scales through the concept of compressive pressure. This reinterpretation not only resolves inconsistencies between the two theories but also offers a cohesive explanation for phenomena ranging from black holes to quantum entanglement.

One of the model’s key contributions lies in its reinterpretation of dark matter and dark energy. By attributing these phenomena to the dynamic equilibrium between energy and space, it eliminates the need for hypothetical particles or exotic fields. The model also redefines black hole singularities, proposing that event horizons represent regions of extreme energy-space balance rather than infinite densities. These innovations offer simpler yet powerful alternatives to conventional theories, while aligning with existing cosmological observations.

The model aligns well with a range of observational data, including the orbital precession of binary systems, gravitational lensing, and cosmic expansion rates. Its nonlinear correction term accurately describes deviations in strong gravitational fields, such as those near black holes. These consistencies highlight the model’s capacity to provide an explanatory framework that complements and extends classical theories.

The predictions of the dynamic equilibrium model are testable through future high-precision observations and experiments. For instance, directional variations in cosmic expansion rates, discrete radiation patterns near black hole event horizons, and microscopic gravitational effects in quantum tunneling can serve as empirical tests. These observations will not only validate the model but also refine its parameters for broader applicability.

Beyond addressing specific phenomena, this model provides a foundational framework for rethinking the universe’s structure and the interplay between its fundamental components. By unifying macroscopic and microscopic perspectives, it has the potential to reshape our understanding of the cosmos and promote the development of new theories in gravitational physics and quantum mechanics.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduces the "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model," a novel framework that seeks to unify macroscopic and microscopic physical phenomena by redefining the relationship between energy and space. The model proposes that the universe functions as a dynamic equilibrium system, where energy and space are inherently interdependent and collectively govern gravitational, cosmological, and quantum phenomena. This reinterpretation challenges conventional notions of gravity, dark matter, and dark energy, offering an alternative explanation grounded in compressive pressure as a fundamental mechanism.

Providing a unified explanation for macroscopic gravitational phenomena such as black holes, cosmic expansion, and gravitational lensing.

Proposing novel interpretations of microscopic phenomena, including quantum entanglement and tunneling, as manifestations of energy-space equilibrium.

Eliminating the need for hypothetical particles and fields to explain dark matter and dark energy, while maintaining consistency with observational data.

The model's predictions, such as discrete radiation patterns near black hole event horizons and directional variations in cosmic expansion rates, are testable through future high-precision experiments and cosmological observations. These predictions offer very promising pathways for validating the theory and refining its parameters.

In summary, the "Cosmic Dynamic Equilibrium Model" provides a fresh perspective on the interplay between energy and space, bridging the gap between general relativity and quantum mechanics. Its implications extend beyond resolving specific phenomena, laying a foundation for further advancements in understanding the universe’s fundamental structure and behavior.

6. Patents

No patents have resulted from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All work in this paper was performed by an independent researcher (Roy Zhao) without the involvement of collaborators.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are publicly available and can be obtained through public access or by request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to his colleagues and friends for their support and encouragement this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no any conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott, B. P.; et al. "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger." Physical Review Letters, vol. 116, no. 6, 2016, 061102. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, V. C., and Ford, W. K. "Rotation of the Andromeda Nebula from a Spectroscopic Survey of Emission Regions." Astrophysical Journal, vol. 159, 1970, pp. 379–403. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S., et al. "Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae." The Astrophysical Journal, vol. 517, no. 2, 1999, pp. 565–586. [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A., Dalibard, J., and Roger, G. "Experimental Test of Bell's Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers." Physical Review Letters, vol. 49, no. 25, 1982, pp. 1804–1807. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W., and Penrose, R. "The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A, vol. 314, no. 1519, 1970, pp. 529–548. [CrossRef]

- Gamow, G. "Zur Quantentheorie des Atomkernes." Zeitschrift für Physik, vol. 51, 1928, pp. 204–212. [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S. K. "Demonstration of the Casimir Force in the 0.6 to 6 μm Range." Physical Review Letters, vol. 78, no. 1, 1997, pp. 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. "Planck 2018 Results. VI. Cosmological Parameters." Astronomy & Astrophysics, vol. 641, 2020, A6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).