Prelude: Entropy as Generative Principle

This prelude introduces the central inversion of TEQ: entropy is not a consequence of physical law, but its origin. Not a statistical byproduct, entropy is the generative structure that determines which distinctions are possible and which configurations persist. Physics does not begin with space, time, or quantization—it begins with resolvability.

Axiom 0 defines entropy as a geometric constraint on distinguishability; Axiom 1 (the Minimal Principle) selects maximally stable patterns within that structure. Together, they replace classical and quantum postulates with a single variational condition: stability under entropy curvature. (See Section 4 for how entropy curvature deforms canonical structure and induces quantization.)

This reframes the foundational question—Why does the world unfold as it does?—as a question of dimensionality. In TEQ, causality is not fundamental but emergent: it arises only when entropy flow becomes rich enough to stabilize distinctions across configurations. Our universe appears causal because it inhabits a regime—where the entropy dimensionality —in which distinctions align, persist, and order themselves in time. This dimensionality includes at least spacetime, but may extend to informational degrees of freedom that shape the geometry of resolution itself. Causality, in this view, is a structural consequence of high-dimensional entropy geometry.

This paper proposes a simple but radical idea: entropy is the structural foundation of physics. Rather than treating entropy as a derivative concept—emerging from classical or quantum dynamics—we reverse the hierarchy: entropy determines which structures are physically realized.

The Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework formalizes this inversion through two core axioms:

1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics (QM), despite its unrivaled empirical success, is traditionally introduced through axioms whose deeper origins remain opaque [

1,

2]. Core elements—the Born rule, wavefunction collapse, and quantization—are postulated rather than derived, leaving foundational questions unresolved [

3,

4,

5].

The Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework proposes a reversal of this structure: quantum behavior is not fundamental, but emerges from entropy. Rather than treating entropy as a secondary thermodynamic quantity, TEQ reinterprets it as the generative constraint governing all physical evolution. Quantum coherence, measurement, and classicality arise from a variational principle in which entropy and action jointly constrain viable trajectories.

At the core of TEQ is a decomposition of entropy into three dynamically coupled components:

Realized entropy — local macroscopic disorder;

Latent entangled entropy — nonlocal quantum correlations;

Latent classical entropy — quasi-stable, decohered structure encoding memory.

This triadic view reframes the quantum-to-classical transition as a continuous redistribution of entropy, eliminating the need for discontinuous collapse or observer-centric postulates. TEQ further introduces the concept of entropy dimensions , classifying the effective dimensionality of entropy flow:

: nonlocal entangled phase space;

: latent classical correlations (e.g., pointer states);

: realized macroscopic structure and spacetime irreversibility.

We reformulate TEQ around a single meta-constraint that replaces traditional axioms:

Minimal Principle (MP):

Physical trajectories are those that remain maximally distinguishable relative to the entropy dimensionality of their domain. (See Section 8 for a unified summary of the principle and its structural consequences.)

This principle defines physical evolution through geometric constraints: entropy structure and resolution determine which configurations persist. From this foundation, we derive an entropy-weighted path integral from first principles and identify as a structural Lagrange multiplier controlling entropy resolution. The Born rule follows from entropy-weighted path selection, with explicit corrections arising from entropy curvature. Quantization and Schrödinger dynamics emerge as limiting cases of entropy-stabilized variation, while a finite- regime leads to an adapted Schrödinger equation with curvature-sensitive corrections. Classical behavior appears as the smooth, low-curvature limit of this entropic geometry.

The path integral evaluates relative distinguishability among trajectories, with entropy gradients acting as geometric filters that select thermodynamically viable paths; the associated entropy curvature, which governs deformation of phase structure, is defined formally in

Section 4.

Unlike other entropy-based approaches—such as Entropic Dynamics [

6] or Jaynesian inference [

7]—TEQ does not assume standard quantum structure. It predicts testable deviations in regimes of strong entropy curvature, including:

These include modified Born statistics, altered coherence times, and constraints on quantization tied to entropy geometry. TEQ thus opens a new route to probing the entropic foundations of quantum theory.

We refer to the geometrothermodynamic limit as the regime in which entropy curvature governs the dominant structural behavior, allowing simplified descriptions where local fluctuations are subordinated to large-scale thermodynamic geometry. Many of the results in this manuscript, such as quantization, classical emergence, and gravitation, are derived as structural consequences within this regime.

Remark 3 (Conceptual Intuition and Broader Significance). At its core, the TEQ framework proposes that physical structure arises from the geometry of entropy itself. Instead of treating quantum laws and gravitational dynamics as fundamental, TEQ starts with a simpler idea: systems evolve along paths that remain maximally distinguishable under entropic constraints. This guiding principle leads to the emergence of quantum amplitudes, spacetime structure, and even fundamental constants, as consequences of a deeper entropic geometry.

This perspective matters beyond physics. It suggests that the very notion of “what exists” depends on what can be resolved or distinguished—an idea with deep resonance in information theory, complexity science, and the philosophy of measurement. In TEQ, quantization is not imposed but arises from structural limits on distinguishability. Entropy is not a measure of ignorance, but a generative principle that shapes what can be known, stabilized, or predicted. This reorientation offers a new foundation for understanding coherence, irreversibility, and the emergence of classical reality.

Structure of the manuscript. Section 2 introduces the entropy-weighted path integral and defines the effective action.

Section 3 derives structural relations among

ℏ,

, and

, identifying a two-dimensional dynamical surface.

Section 4 interprets quantization as a geometric stability condition.

Section 5 derives the Born rule and formulates corrections in high-curvature regimes.

Section 6 presents the Schrödinger equation as a limit of entropy-stabilized evolution.

Section 7 proposes an entropic basis for spacetime and gravity.

Navigating TEQ

For orientation, we provide two reference tools: a structural overview diagram and a glossary of key terms.

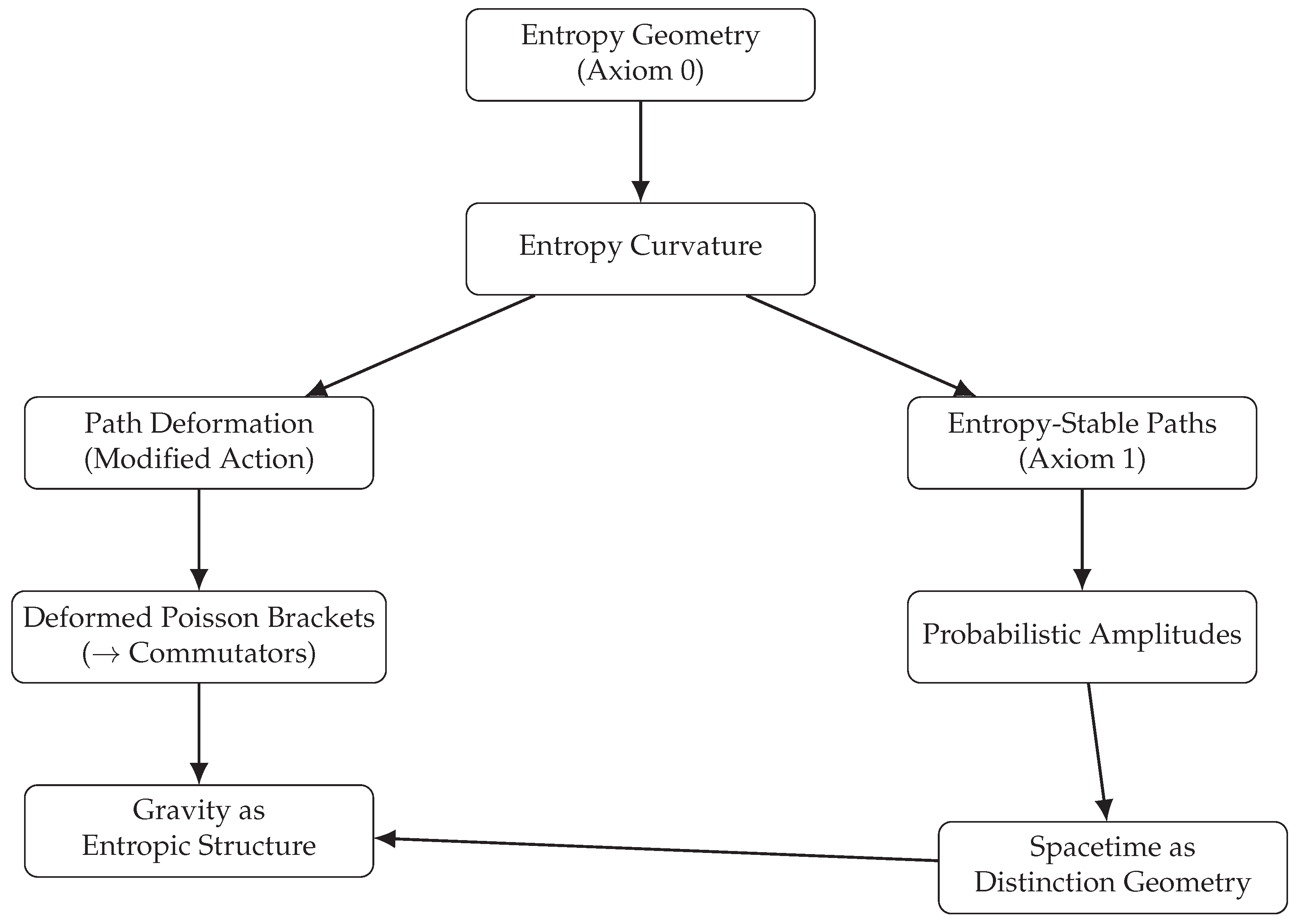

Figure 1 illustrates how the core axioms generate the major results of the theory, clarifying the dependency structure between assumptions, derivations, and physical consequences. The accompanying table summarizes central concepts, helping to reduce interpretive load–especially for interdisciplinary readers.

To further support conceptual clarity,

Table 1 summarizes key terms used throughout the manuscript, with a focus on their operational meaning within the TEQ framework.

Dynamical Regimes in TEQ. To clarify how standard physical behavior emerges from the TEQ framework, we introduce a structural taxonomy of dynamical regimes based on the dominance of entropy versus action and the geometry of entropy flow. This classification helps distinguish the quantum limit, classical behavior, and novel entropy-dominant phases predicted by TEQ.

Table 2 below summarizes these regimes and their associated features.

Overview of Results

The Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework rederives the foundational structures of quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, and spacetime from a single entropic variational principle: the Minimal Principle (MP). Rather than assuming conventional postulates, TEQ shows that quantum and classical behavior emerge from entropy-weighted selection among resolvable configurations.

This section summarizes the main results and contrasts standard quantum postulates with their derivations or reinterpretations under TEQ.

Key Contributions

-

Entropy-Weighted Path Selection: TEQ replaces the classical action principle with a variational principle derived from the Minimal Principle (Axiom 1): physical trajectories are those that remain maximally distinguishable under entropy flow. This yields:

- -

The Born rule as a statistical consequence of entropy-stabilized trajectories,

- -

The Schrödinger equation from entropic deformation of classical action,

- -

Commutation relations and quantization from entropy-curved geometry.

-

Entropy Dimensions : A classification of entropy flow regimes:

- -

: Nonlocal entanglement,

- -

: Latent classical correlations,

- -

: Realized macroscopic structure and time-asymmetry.

Unified Constants: The constants ℏ and appear as structural multipliers in distinct entropic regimes, linking phase coherence and entropy resolution through the parameter .

Minimal Principle as Structural Generator: All physical structure—quantization, coherence, decoherence, and classicality—arises from the Minimal Principle (Axiom 1). This replaces conventional dynamical and measurement postulates with a single entropic variational condition.

Postulates Reinterpreted via TEQ

Table 3 contrasts standard quantum postulates with their TEQ counterparts, all derived from the Minimal Principle. Rather than assuming structures such as unitary evolution or canonical quantization, TEQ reconstructs them as emergent features of entropy geometry. This unifies quantum and thermodynamic reasoning and reframes quantization as a consequence of constrained resolution.

2. The Entropy-Weighted Feynman Path Integral from a Minimal Principle

This section derives the Feynman path integral as a consequence of TEQ’s structural axioms. Rather than postulating quantum behavior, we show that entropy-weighted amplitudes emerge from the Minimal Principle (MP), which governs stability under finite resolution. Classical action is generalized into a geometric entropy functional, and the resulting dynamics favor entropy-resilient trajectories. The standard quantum amplitude arises in the limit of vanishing entropy curvature. By embedding thermodynamic stability into the variational structure, this approach recasts quantization as a response to entropy-induced instability in trajectory space.

In TEQ, quantum structure is not assumed—it is derived from a single variational constraint:

Minimal Principle (MP):

Physical trajectories maximize distinguishability of entropy flow under structural constraints.

This principle unifies path selection, thermodynamic stability, and quantum amplitudes. The Feynman path integral emerges naturally as a statistical expression of entropy-weighted distinguishability, generalizing classical action into entropy geometry.

2.1. Standard Amplitude Formulation

In standard quantum mechanics, the transition amplitude is given by:

where

is the classical action, and

integrates over all histories. All paths contribute equally in magnitude; only phase varies [

11]. This implicitly assumes no entropy-based preference among paths.

In TEQ, uniform amplitude is recovered only when entropy curvature vanishes. In general, entropy-instability leads to suppression: paths with higher entropy production contribute less. This weighting is not an external assumption—it follows directly from the Minimal Principle. Decoherence hints at a similar structure: paths differing significantly in entropy production interfere less, biasing evolution toward entropy-stable trajectories.

2.2. Entropic Weighting as a Consequence of MP

Lemma 1 (Entropy Bias from the Minimal Principle).

The Minimal Principle selects trajectories based on entropy stability. This weighting parallels the Feynman–Vernon influence functional [12]: where encodes entropy-producing interactions, structurally analogous to decoherence functionals in open-system quantum theory [4,13].

TEQ does not postulate this suppression—it derives it (see

Appendix J). Entropy weighting follows naturally from constrained optimization of distinguishability under MP, introducing the Lagrange multiplier

. The entropy functional

, defined below, captures the observer-resolvable entropy flow.

2.3. Entropy-Weighted Amplitudes from MP

In Appendix J.1, we derive:

Theorem 1 (Path Amplitudes from the Minimal Principle).

The effective amplitude for a path ϕ is: where arises from constrained variation. The classical Feynman integral is recovered in the limit .

The parameter interpolates between dynamical regimes. When , standard unitary evolution is recovered; when , the system enters a thermal regime. These are not independent assumptions, but limiting cases of a unified entropy-weighted framework.

Equation (

3) suggests the following form for the effective action:

where

is a time-local entropy flux functional.

This expression encodes both dynamical phase and entropic suppression. The function

g represents the local entropy flux—the rate of apparent entropy production along a path—and contributes to the total

(see

Appendix K for a general, assumption-minimizing form of

g). It does not describe classical dissipation, but expresses a geometric constraint that suppresses entropy-violating paths and selects stable configurations.

Remark 4 (Entropy Weighting, Measure Instability, and Path Selection). In standard quantum mechanics, all paths contribute equally to the path integral, differing only by phase. TEQ introduces entropy flow as a geometric constraint that modifies this principle. Trajectories are no longer treated symmetrically: paths that lead to steep entropy gradients are exponentially suppressed, as they imply a loss of stable, resolvable distinctions. The entropy weighting term breaks the uniformity of the measure, introducing exponential sensitivity to entropy curvature.

In regimes of strong entropy variation, the unmodified path integral becomes unstable: infinitesimally close trajectories can differ exponentially in weight due to high entropy curvature, rendering the standard measure ill-defined. TEQ resolves this by selecting only entropy-stationary trajectories, around which the weighting becomes sharply peaked and stable. This eliminates the singular behavior and motivates a deformation of the variational geometry itself. Quantization thus emerges not as an axiom, but as a structural response to entropy-induced instability in trajectory space.

2.4. Interpretation and Structural Role of

The constants ℏ and emerge as dual Lagrange multipliers (see Appendix J.1):

suppresses entropy-unstable paths;

ℏ preserves phase coherence;

Together, they govern entropy-weighted quantum dynamics.

Corollary 1 (Born Rule from the Minimal Principle).

The Born rule arises naturally in the large-β limit from suppression of entropically unstable paths. Probabilities reflect stability, not fundamental indeterminism. See §5.

Paradigm Shift. Quantum amplitudes emerge as structural consequences of entropy-weighted distinguishability. The Minimal Principle selects viable trajectories. β and ℏ are thus structural multipliers—not independent parameters.

2.5. Modified Euler–Lagrange Equation

Theorem 2 (Entropy-Corrected Dynamics from MP).

Variation of the entropy-weighted action (4) yields:

This extends classical extremality by introducing geometric bias favoring entropy-stable trajectories.

Remark 5 (Intuitive Meaning of Entropy Curvature). Entropy curvature measures how rapidly entropy production changes as we move between different paths. Intuitively, high entropy curvature corresponds to regions where small changes in trajectory lead to large changes in distinguishability. The Minimal Principle favors paths that remain stable under these variations—effectively selecting trajectories that avoid steep entropy gradients. Thus, entropy curvature functions like a landscape of stability: physical paths settle into entropy-stable valleys rather than entropy-unstable peaks.

In the limit , standard quantum or classical mechanics is recovered.

Corollary 2 (Entropy-Stabilized Classical Emergence). As , the classical Euler–Lagrange equation reemerges, but entropy curvature continues filtering viable macroscopic paths. Classicality is thus a stabilized limit of entropy geometry.

Paradigm Shift. The least-action principle is generalized by the Minimal Principle. Physical evolution selects entropy-resilient paths. Classical mechanics is thus not fundamental but emerges naturally as the stable, entropy-filtered limit of quantum dynamics.

3. Geometric Structure of Fundamental Constants

This section analyzes how the apparent constants of nature—Planck’s constant ℏ, the inverse temperature parameter β, and Boltzmann’s constant —emerge within TEQ as projections of a unified entropy-action geometry. Rather than being fixed, irreducible inputs, these quantities reflect structural relationships that govern resolvability and coherence under entropy curvature. By making this geometry explicit, we show that these constants are neither fundamental nor independent, but arise as limiting behaviors within a minimal two-dimensional framework. The result is a principled reinterpretation of physical constants as emergent from the same entropic structure that underlies quantum and thermal dynamics.

In the Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework, the constants ℏ, , and are not fixed inputs but emergent structural parameters. They reflect how finely distinctions can be resolved and how entropy curvature stabilizes or suppresses paths. Their apparent constancy arises from the stability of entropy geometry across regimes—not from fundamental necessity, but from geometric regularity. While ℏ and are traditionally treated as fundamental, and as a statistical parameter, TEQ derives all three as effective scales within a unified entropy-action structure. This structure follows from two generative assumptions:

Axiom 0: Entropy defines a geometric field over possible configurations, establishing resolvability;

Axiom 1 (Minimal Principle): Physical paths remain maximally distinguishable within this entropy geometry.

From this foundation, the constants ℏ, , and emerge as interdependent projections within a unified geometric structure.

Minimal Principle and Entropic Selector

Consider first the entropy-weighted amplitude introduced in TEQ:

This amplitude structurally distinguishes two fundamental aspects:

an imaginary component, governing quantum coherence via the action ;

a real component, encoding thermodynamic irreversibility via entropy .

This duality strongly suggests a simple geometric representation in terms of a two-dimensional entropy-action plane. Specifically, we represent amplitudes through linear projections onto this plane using a complex

selector vector :

where the magnitude

sets the overall scale, and the selector angle

modulates the balance between quantum coherence (imaginary) and entropy-driven dissipation (real).

Remark 6 (Rationale for the Linear Geometric Assumption). The choice of a linear two-dimensional geometry to represent the entropy-action structure is not arbitrary, but is motivated by simplicity and direct correspondence to the inherently real and imaginary decomposition of amplitudes. While nonlinear or higher-dimensional generalizations could be considered—particularly in regimes of strong entropy curvature or complex multi-scale interactions—the linear geometric assumption constitutes the simplest, conceptually transparent, and analytically tractable choice that fully captures the dual role of entropy and action. Future extensions might explore nonlinear geometric structures or higher-dimensional selectors, particularly where empirical deviations from standard quantum predictions necessitate more complex geometries.

Matching this geometric selector explicitly to the amplitude structure:

we immediately recover the fundamental parameters in geometric form:

Thus, the dimensionless entropy-resolution parameter emerges as:

This parameterization gives a direct geometric interpretation of as a fundamental dial tuning the balance between quantum coherence and entropic dissipation:

Quantum-coherent limit (): entropy curvature vanishes; dynamics become unitary.

Classical-thermal limit (): entropy dominates, coherence is suppressed, and dynamics become fully dissipative.

The selector vector, therefore, is not introduced as an independent postulate. Rather, it explicitly encodes a structure already implicitly present in the TEQ amplitude. Making this structure explicit clarifies the underlying geometric unity, illustrating clearly how the constants ℏ, , and emerge naturally from a minimal geometric assumption.

Dimensional Consistency and the Role of

To restore thermodynamic units, define:

Theorem 3 (Unified Constants from Entropy Geometry).

The constants ℏ, β, and arise from a two-dimensional entropy-action geometry:

Corollary 3 (Entropy-Coherence Scaling and Limiting Regimes). The dimensionless parameter governs the balance between entropy suppression and phase coherence. It defines the dynamical regime of the system, with limiting behaviors:

Quantum (unitary): ;

Thermal: ;

Intermediate: , partial coherence regimes.

Feynman and Boltzmann weights emerge as limits of the same entropy-weighted structure, and the constants ℏ and act as scale-setting factors for phase coherence and entropy resolution. Representative values are summarized in Table 4.

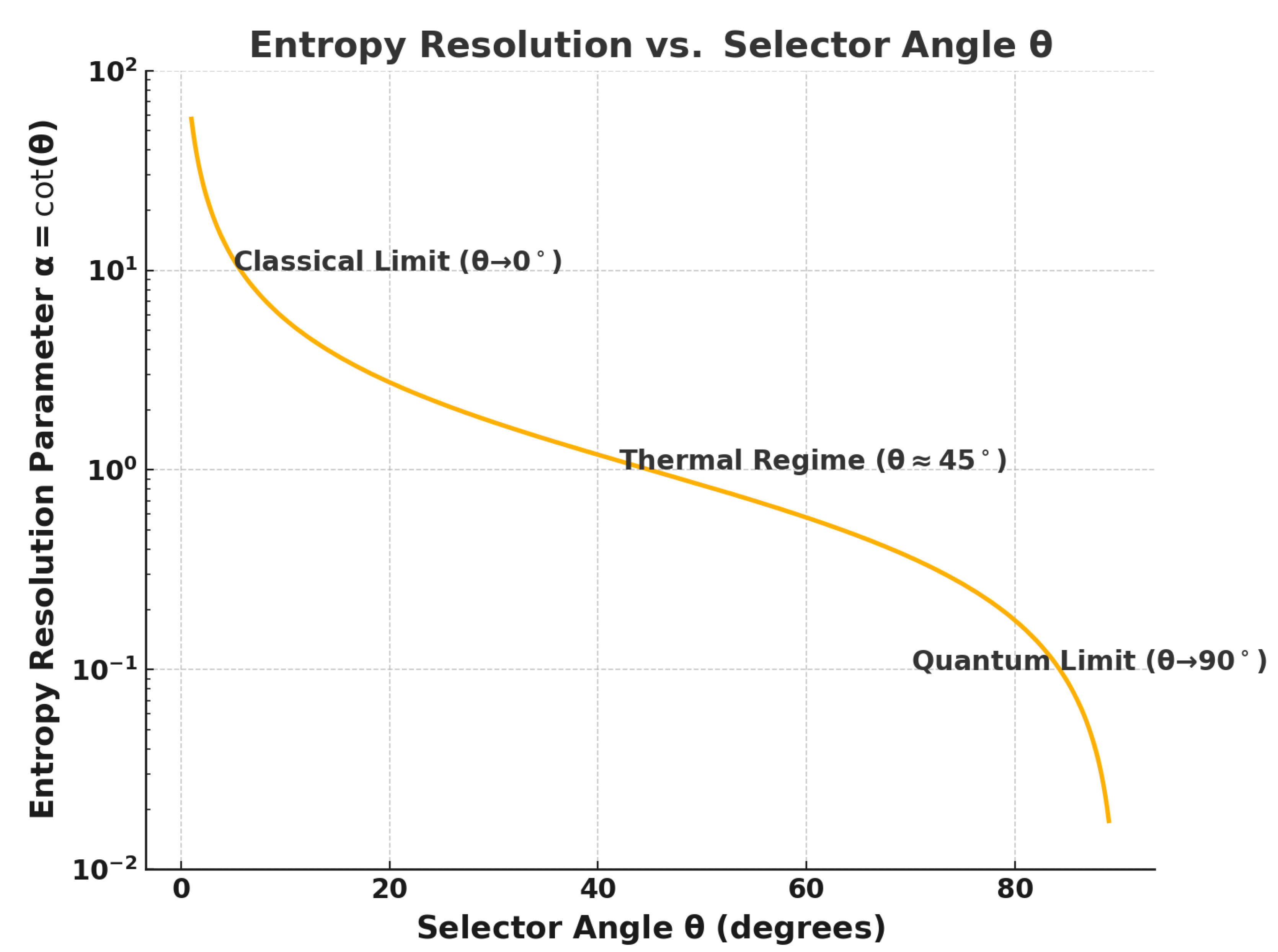

Figure 2.

Entropy resolution parameter as a function of selector angle . The quantum limit corresponds to , the classical/thermal limit to .

Figure 2.

Entropy resolution parameter as a function of selector angle . The quantum limit corresponds to , the classical/thermal limit to .

Remark on the Emergence of Unitarity. In TEQ, unitarity is not a fundamental postulate but an emergent behavior in the flat-curvature, coherence-dominated limit of the entropy-weighted action. It arises when entropy flow vanishes and the system approaches maximal resolution, with . In this regime, amplitudes evolve purely oscillatory and probability is conserved through unitary dynamics.

As entropy gradients activate and curvature grows, coherence is lost and evolution becomes non-unitary. Dissipation, decoherence, and irreversibility are thus not anomalies to be explained away, but intrinsic consequences of entropy-weighted structure. Conservation is not violated, but generalized: replaced by structural distinguishability across entropy-curved paths.

TEQ implies that unitarity is not generic, but a special case realized only when entropy curvature vanishes. In strongly curved regimes—such as early cosmology, black hole evaporation, or macroscopic decoherence—non-unitary evolution is structurally expected. See

Appendix O for standard approaches to handling non-unitarity.

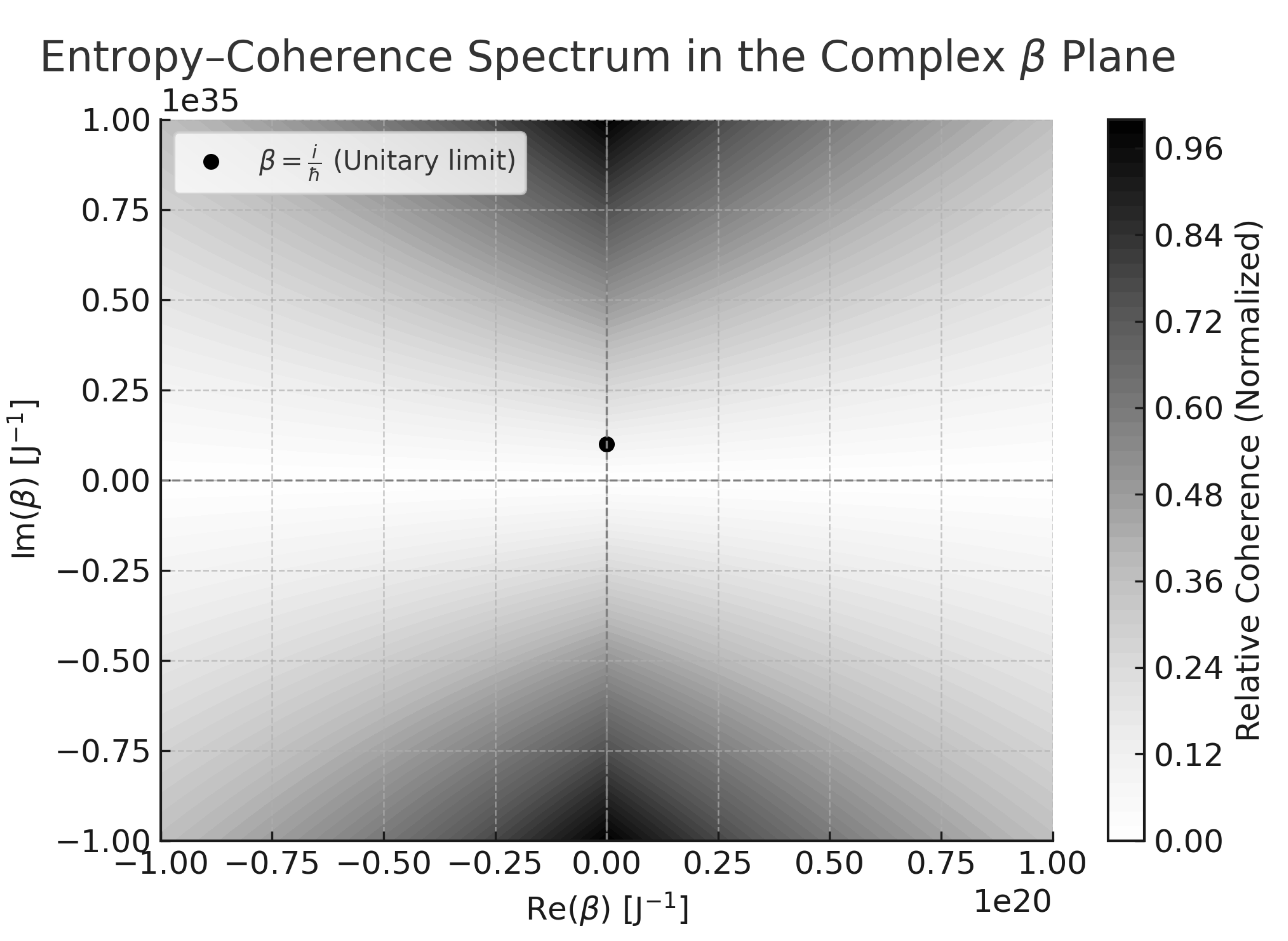

Figure 3.

Entropy—coherence spectrum in the complex plane. The grayscale intensity encodes relative coherence strength, with higher values corresponding to stronger phase coherence. The imaginary axis captures coherent dynamics (), while the real axis corresponds to entropy-dominated suppression regimes (). The plot illustrates how TEQ interpolates between quantum and thermodynamic behavior through variations in entropy geometry.

Figure 3.

Entropy—coherence spectrum in the complex plane. The grayscale intensity encodes relative coherence strength, with higher values corresponding to stronger phase coherence. The imaginary axis captures coherent dynamics (), while the real axis corresponds to entropy-dominated suppression regimes (). The plot illustrates how TEQ interpolates between quantum and thermodynamic behavior through variations in entropy geometry.

Observer Resolution and Gauge Structure

The parameter

encodes the entropy resolution available to the observer—how finely entropy-distinguishable structure can be resolved. Shifts in

act as gauge transformations in the entropy geometry [

14,

15], leaving the underlying dynamics invariant but altering the resolution scale.

Structural Role of Axiom 0. The geometric relationships among ℏ, , and are not imposed. They arise from a prestructured entropy geometry (Axiom 0), constrained by the Minimal Principle (Axiom 1). Constants are projections of resolution and coherence within this geometry.

4. Quantization as Entropic Deformation of Symplectic Geometry

TThis section derives quantization as a geometric consequence of entropy-stabilized dynamics. Here, “quantization” refers to the emergence of noncommutative algebraic structure and discrete resolvable modes, both as consequences of entropy geometry. In TEQ, classical symplectic geometry becomes unstable under entropy curvature, and the variational structure deforms to preserve distinguishability. This deformation leads to modified conjugate momenta, noncanonical Poisson brackets, and ultimately to quantum commutators. Quantization thus arises not from postulates or operator formalism, but from the failure of classical resolution in entropy-curved phase space. By tracing how entropy flow modifies the effective action and phase structure, we show that noncommutativity encodes the minimal distinguishability permitted by entropy geometry.

In TEQ, quantization and noncommutativity are not postulated but arise as necessary geometric consequences of entropy structure. The central idea is that entropy flow governs the resolvability of trajectories. When entropy curvature , the underlying geometry of phase space is no longer flat and classical symplectic structure fails to describe stable evolution. Instead, TEQ imposes a variational constraint that selects only those trajectories which remain distinguishable under entropy deformation.

This modifies the effective phase space geometry, leading to a generalized conjugate momentum, deformed Poisson brackets, and eventually noncommutative operator structure. Quantization thus becomes a stability condition rooted in thermodynamic distinguishability, not an externally imposed axiom.

4.1. Entropy-Weighted Dynamics and Effective Momentum

Lemma 2 (Entropy-Weighted Momentum).

Given the entropy-weighted effective action

the effective momentum is

generalizing classical conjugate momentum by incorporating entropy flow as a stabilizing term.

Remark on Hermitian and Non-Hermitian Structure. In TEQ, the effective action is complex-valued, with entropy flow contributing an imaginary deformation. The resulting Euler–Lagrange equation naturally incorporates dissipative structure, and the effective Hamiltonian may become non-Hermitian in regimes of strong entropy curvature. Hermiticity is not postulated, but emerges in the entropy-coherent limit where entropy flow is symmetric or negligible. Thus, both Hermitian and non-Hermitian dynamics are unified within a single variational principle, reflecting local geometry of entropy stability rather than arbitrary assumptions. Dissipation, decoherence, and resolvability loss correspond directly to non-Hermitian deformation.

Definition 1 (Entropy Curvature).

Entropy curvature is defined as

characterizing local constraints on distinguishability in velocity space.

This quantity measures how rapidly entropy flow changes with respect to variations in velocity . A nonzero indicates that small fluctuations in trajectory velocity lead to measurable changes in entropy flow, thus affecting the stability and resolvability of the path. When , entropy suppression is uniform across paths; when , entropy acts as stabilizing curvature, filtering out rapidly diverging trajectories. This curvature term deforms the canonical phase structure, underpinning TEQ’s generalized quantization conditions.

Remark 7 (Structure and Interpretation of the Entropy Functional ). The entropy functional plays a central role in the TEQ framework. It defines the local entropy flux along a trajectory, determining how resolvability varies under coarse-grained evolution. Unlike thermodynamic entropy, which is usually state-dependent, g is a rate-functional—it encodes how entropy is produced or dissipated during transitions between configurations.

Minimal Requirements:

: entropy is not locally reversed under coarse-graining;

g is at least in : ensures that curvature is well-defined;

g encodes resolution limits and may vary with the coarse-graining scale or effective observational precision.

Illustrative Example: Free Particle with Resolution Cost.Consider a simple entropy functional:

which penalizes high-velocity transitions due to their instability under coarse resolution. This choice implies:

and leads directly to entropy-curvature-induced deformation of the momentum and commutator structure (see Section 4).

Generalizations:More complex systems may involve higher-order or non-quadratic forms of g, such as:

where acts as an entropy metric tensor. This form parallels Lagrangians with configuration-dependent mass and introduces spatially modulated entropy curvature.

Interpretive Note:The functional g does not depend on a prior thermodynamic system. It is emergent from the distinguishability structure and encodes the entropy penalty for transitioning between configurations at finite resolution. In this way, TEQ generalizes the notion of entropy flow into a purely geometric field over phase space trajectories.

Remark 8 (Intuitive Origin of Quantization from Entropy Geometry). Quantization in TEQ emerges because entropy curvature modifies how distinct states in phase space relate to each other. Classically, positions and momenta commute, reflecting infinite resolution of phase space structure. Entropy curvature introduces a fundamental resolution limit: states cannot be infinitely distinguished due to thermodynamic constraints. As a result, positions and momenta no longer commute exactly, manifesting as quantization. Conceptually, quantization is not an imposed rule, but a geometric necessity arising from the limited resolvability of paths under entropy constraints.

4.2. Deformation of Symplectic Structure

In classical mechanics, the Poisson bracket reflects the flat, globally resolvable geometry of phase space–each trajectory is distinguishable, and the symplectic structure remains uniform. But under entropy weighting, this assumption breaks down. When entropy curvature varies rapidly, the effective measure in the path integral becomes sharply nonuniform: trajectories arbitrarily close in configuration space can differ exponentially in entropic weight. This leads to a singular, ill-defined measure and signals a geometric instability in the classical variational framework. Classical resolution fails not due to stochasticity, but because the space of trajectories no longer supports uniform distinguishability. The path integral becomes dominated by a sparse set of entropy-stationary configurations, and the underlying symplectic structure must deform accordingly. Quantization thus emerges as a structural repair–restoring coherent dynamics in the presence of entropy-induced degeneracy.

To preserve well-defined evolution under these conditions, TEQ deforms the symplectic structure itself. This deformation ensures that path stability, distinguishability, and phase volume all remain consistent with the entropy-weighted action. The result is a curved, thermodynamically-constrained geometry of phase space.

In Appendix M.1, we derive:

Theorem 4 (Entropy-Deformed Poisson Bracket).

Entropy curvature modifies the classical Poisson bracket:

This deformation reflects the shift from pure Hamiltonian dynamics to entropy-constrained trajectory space. The classical bracket is recovered as or .

This commutator deformation follows from analyzing the entropy-weighted second variation of the effective action, which modifies the stability kernel of fluctuations. The resulting curvature acts as an effective inverse propagator, leading to a rescaling of minimal resolvable phase-space area, and hence to a deformed commutator.

Theorem 5 (Quantization from Entropy-Curved Geometry).

From the entropy-weighted action (Eq. (4)) and the resulting deformation of symplectic structure (Appendix M), the canonical commutator becomes: where is entropy curvature. The classical commutator emerges when .

Corollary 4 (Thermodynamic Origin of Noncommutativity). Quantization is not postulated but structurally required: noncommutativity arises naturally as a geometric constraint from entropy-curved phase space. It encodes minimal resolvability of trajectories under entropy-driven stability.

Remark 9 (Structural Role of Mass).

The parameter m acts not as inertial mass per se, but as a buffer against entropy curvature. Canonical behavior is preserved if:

This suggests a thermodynamic interpretation of mass as resistance to entropic deformation, analogous to how mass resists spacetime curvature in general relativity (see §7.3).

Structural Insight. In TEQ, quantization is not imposed but derived. Entropy curvature makes classical phase space structure unstable to perturbations. The only trajectories that remain well-resolved under entropy-weighted variation are those consistent with a deformed, quantized geometry. Quantization thus arises as the only viable structure compatible with entropy-stabilized evolution.

4.3. Quantization from Entropic Mode Stability

Theorem 6 (Discrete Modes from Entropy Stationarity).

In the entropy-weighted path integral

dominant contributions come from entropy-stationary paths. First-order stationarity yields:

showing quantized momenta arise as entropy-optimized configurations.

Remark 10 (Derivation and Intuition).

Extremizing the effective action yields:

balancing dynamical cost against entropy distinguishability. Interpreting leads directly to quantized momenta as conditions ensuring stable distinguishability.

Corollary 5 (Entropy-Curvature Uncertainty Relation).

Entropy curvature modifies the uncertainty bound:

Positive curvature increases the lower bound, reflecting thermodynamic limits on resolution.

Structural Insight. The uncertainty principle is entropy-sensitive. In TEQ, thermodynamics and quantization unify as constraints on stable distinguishability.

Remark on Hilbert Space Emergence. In TEQ, the Hilbert space formalism of quantum theory is not assumed but emergent. In the limit where entropy curvature and resolution is maximal (), the space of distinguishable amplitudes becomes effectively linear, with interference defining a well-behaved inner product. Hilbert space thus emerges naturally as the coherence-maximized, flat-curvature limit of entropy geometry. It encodes distinguishable, resolvable configurations under maximal resolution. Outside this regime—where entropy curvature is strong or observer resolution limited—the Hilbert space description breaks down, and TEQ provides a more general variational structure.

5. Derivation of the Born Rule from the Minimal Principle

This section derives the Born rule not as a postulate but as a consequence of TEQ’s Minimal Principle. In standard quantum theory, probabilities are assigned by fiat through squared amplitudes. In TEQ, these probabilities arise from entropy-weighted variation: only distinguishable, entropy-stable paths contribute significantly to the path integral. By expanding around entropy-stationary trajectories, we recover the Born rule as the entropy-flat limit and obtain explicit corrections from entropy curvature. The result grounds probabilistic outcomes in thermodynamic geometry, linking quantum statistics to structural resolvability.

In standard quantum mechanics, the Born rule is postulated:

assigning probabilities to outcomes

via the squared wavefunction amplitude [

2,

16]. In TEQ, this rule is not assumed but derived: probabilities emerge from the entropy-weighted stability of distinguishable paths under the Minimal Principle.

5.1. Experimental Implications and Regimes of Deviation

Entropy-flat regime:. Standard quantum behavior holds.

Entropy-curved regime: Variations in H introduce measurable corrections, particularly in systems with strong gradients or nonequilibrium dynamics.

Testable domains: High-precision interferometry [

20], gravitational decoherence [

21], and nonequilibrium quantum thermodynamics [

22] offer experimental windows for detecting curvature-induced deviations.

6. Emergence of the Schrödinger Equation via the Minimal Principle

This section derives the Schrödinger equation from the Minimal Principle, without assuming it as a foundational postulate. In TEQ, quantum dynamics emerge from entropy-weighted variation: only those trajectories that remain both phase-coherent and entropy-stable contribute to physical evolution. By introducing the entropy-weighted momentum and applying the entropy gradient approximation, we recover the Schrödinger equation as the limiting case of entropy-curved dynamics.

This derivation holds in the high-resolution regime, where entropy curvature vanishes and distinguishability is maximal. In this limit, unitary evolution appears as a special case of entropy-stabilized geometry. For finite β, the Schrödinger equation acquires explicit corrections governed by entropy flow and local curvature. The adapted equation is presented at the end of this section; its derivation proceeds directly from the entropy-weighted amplitude.

In conventional quantum theory, the Schrödinger equation

is introduced axiomatically (see, e.g., [

1,

23]). In TEQ, it arises from the Minimal Principle: physical trajectories must remain entropy-distinguishable under constrained variation within the entropy geometry defined by Axiom 0. Only those paths that remain stable under entropy curvature contribute constructively to evolution. The Schrödinger equation thus emerges not as a postulate, but as the limiting behavior of entropy-weighted dynamics in a flat-entropy regime.

6.1. Entropy-Constrained Action and Effective Momentum

We begin with the entropy-weighted action (

4):

where

L is the classical Lagrangian,

g encodes apparent entropy flow, and

governs entropy resolution.

Variation of this action yields the modified Euler–Lagrange equation (Theorem

5), and motivates a complexified momentum.

Definition 2 (Entropy-Weighted Momentum).

The conjugate momentum becomes:

introducing a complex deformation of phase space due to entropy curvature.

Example 1 (Free Particle with Entropy Flow).

For and , we find:

This modifies the phase-space structure, embedding entropic filtering directly into kinematics.

Entropy Gradient Approximation

Lemma 3 (Entropy Gradient Approximation).

If and has bounded curvature in , then:

This enables a configuration-space representation of entropy-weighted dynamics. A full derivation appears in

Appendix Q.

Minimal Principle and Schrödinger Dynamics

Theorem 7 (Schrödinger Equation from the Minimal Principle).

Let be defined as in Definition 2. In the entropy-stabilized regime, the entropy gradient approximation (Lemma 3) gives:

For a free particle, near stationary paths, leaving:

From Lemma ?? and Theorem ??, the stationary-path probability satisfies:

This is the canonical quantum momentum operator, emerging here as the limiting case of entropy-weighted dynamics. In TEQ, it reflects phase-coherent stability under vanishing entropy curvature.

Substituting into the effective Hamiltonian,

yields the standard evolution law:

Corollary 6 (Schrödinger Equation as Stability Condition). The Schrödinger equation emerges as the unique configuration-space dynamics consistent with entropy-constrained distinguishability. It selects phase-stable trajectories in the entropy-flat limit.

6.2. Adapted Schrödinger Equation in the Finite- Regime

The standard Schrödinger equation arises in TEQ only as a limiting case: when entropy curvature vanishes and coherence is fully preserved. More generally, for finite , path distinguishability is modulated by entropy flow, leading to corrections in the effective dynamics. These corrections reflect local entropy gradients and the geometry of resolvable configurations.

We begin with the entropy-weighted amplitude derived from the Minimal Principle. As given in Corollary , Eq. (), the wavefunction for configuration

is:

where

is the classical action and

is the apparent entropy evaluated on the entropy-stationary path.

In TEQ, the function arises as the leading contribution to the entropy-weighted path amplitude. It is not assumed to satisfy a dynamical equation; rather, the Schrödinger-like evolution is derived from how this amplitude changes under entropy-stabilized variation.

To derive the effective dynamics, we apply the gradient operator to the entropy-weighted amplitude

, yielding by the chain rule:

and a second derivative yields:

From this, the kinetic energy operator is defined as:

which becomes:

Adding a potential

, the effective Hamiltonian becomes:

leading to the following result.

Theorem 8 (Adapted Schrödinger Equation in Finite-

Regime).

In the TEQ framework, the wavefunction evolves according to: where encodes entropy curvature. In the limit , the entropy corrections vanish and the equation reduces to the standard Schrödinger equation.

This result holds for single-particle systems under coarse-grained entropy flow. In field-theoretic or multi-particle generalizations, the effective Hamiltonian acquires additional geometric and combinatorial terms reflecting entropy coupling across degrees of freedom.

This expression shows that the TEQ wavefunction is not assumed but derived as the entropy-weighted amplitude over configuration space. The effective dynamics reflect both phase coherence and entropy suppression, leading to drift and curvature terms in the evolution equation. In high-curvature regimes, coherence is degraded and evolution becomes non-unitary. In the large- limit, only entropy-stationary configurations contribute, recovering standard quantum behavior.

The real-valued terms (e.g., , ) modulate decay and dissipation of amplitude, while the imaginary drift term shifts the local phase velocity. These collectively determine how entropy geometry governs coherence loss and effective decoherence.

Paradigm Shift. The Schrödinger equation is not a foundational axiom. It is the dynamical signature of entropy-stabilized, phase-coherent evolution, selected by the Minimal Principle within the entropy geometry defined by Axiom 0.

6.3. From Classical Action to Entropic Coherence

TEQ extends classical extremality by embedding entropy stability into the variational structure. At quantum scales, entropy curvature alters trajectory viability, selecting only phase-coherent, entropy-stable paths. This generalization is summarized in

Table 5.

7. Toward Gravitation from Entropic Geometry

This section develops the emergence of gravity in TEQ as a structural response to entropy geometry. Rather than postulating spacetime curvature, we show that gravitational phenomena arise from entropy gradients that bias which configurations remain distinguishable. Axiom 0 introduces curvature into configuration space via entropy flow, while the Minimal Principle filters for stability. Together, these generate effective geometric structure: energy–momentum flow becomes linked to entropy curvature, and mass emerges as resistance to entropic deformation. Gravitation, in this framework, is not a fundamental interaction but the thermodynamic stabilization of resolvable structure.

See also Jacobson [

8], Padmanabhan [

9], and Verlinde [

10] for related views of gravity as emergent from entropy gradients.

Remark 11 (Conceptual Summary: Gravity from Entropy Structure).

In TEQ, gravity is not a fundamental force but a structural response to irreversible entropy flow. Where gradients become non-reversible, curvature arises as resistance to redistributing distinctions—an effect rooted in the entropy-dimensional analysis of Section 2. Spacetime is not a backdrop but an emergent bias: a geometry that favors stable, distinguishable paths. Gravitational phenomena arise when entropy structure becomes rich enough to sustain localized, persistent configurations.

In TEQ, gravitation is not a property of predefined spacetime. It emerges from the interaction of two structural principles. Axiom 0 defines entropy as a generative constraint on the geometry of possible configurations. It endows configuration space with curvature, resolution limits, and the potential for structure. The Minimal Principle (MP) then selects those configurations that remain maximally distinguishable under entropy flow. Together, they imply that classical curvature arises as the entropy-preserving deformation of trajectory space.

7.1. Entropy Dimensionality and Curvature Activation

Entropy redistribution behaves qualitatively differently across regimes of entropy dimensionality:

Definition 3 (Entropy Dimensional Regimes).

- (1)

Entangled Regime(): Fully nonlocal entropy. No classical support; no spatial geometry.

- (2)

Latent Regime(): Stable quasi-classical correlations (e.g., pointer states); approximate geometry.

- (3)

Realized Regime(): Entropy gradients become irreversible and geometric. Spacetime structure emerges.

Remark 12 (Conceptual Meaning of Entropy Dimensional Regimes). These dimensional regimes classify how much structure entropy can support. In the entangled regime, distinctions are fully nonlocal—nothing is individually identifiable. In the latent regime, approximate classicality begins to stabilize, allowing emergent structure. Only in the realized regime does entropy flow become irreversible enough to generate robust, geometric features like spacetime and curvature. These transitions mark structural thresholds: from quantum coherence to classical decoherence to gravitational geometry.

Only for does entropy curvature take geometric form. Below this threshold, distinguishability remains delocalized or latent.

7.2. Noether Balance and Entropy-Stress

The following result extends Noether’s theorem [

24] to complex, entropy-weighted actions. Although Noether’s original formulation assumed real-valued Lagrangians, the symmetry argument still yields conservation laws—now encoding the joint flow of energy and entropy.

Lemma 4 (Diffeomorphism Invariance under Entropic Constraint).

Let the entropy-weighted effective action be

Under an infinitesimal coordinate shift , we obtain: where:

is the energy–momentum tensor,

is the entropy-stress tensor.

Remark. This generalizes the one-dimensional action (4), where entropy flow enters through a scalar functional . In the covariant setting, entropy geometry gives rise to the tensor , which structurally biases the dynamics toward distinguishable paths.

Corollary 7 (Entropy-Balanced Continuity).

From invariance under the Minimal Principle:

These continuity conditions express a simple idea: energy and entropy are not arbitrarily exchanged—they must flow in ways consistent with the underlying structure. Rather than being imposed, this balance follows naturally from the entropy-weighted geometry and the variational principle.

7.3. Entropy Curvature as Geometric Source

Definition 4 (Entropy Curvature Tensor).

Define:

as the second-order entropy curvature. This tensor captures how entropy flow deforms the surrounding structure—it measures how curved the entropy landscape is at a given point.

Relation to Local Curvature: In the one-dimensional or trajectory-based formulation, entropy curvature appears as

which quantifies local constraints on distinguishability in velocity space. The tensor generalizes this to spacetime, encoding how distinguishability constraints vary in all directions and contribute to the emergent geometry.

Theorem 9 (Emergent Geometry from Entropic Equilibrium).

The Minimal Principle requires a local match between energy flow and entropy gradient. In simplified terms: where represents a small shift in the local frame—a kind of “preferred direction” used to compare changes. From this balance it follows that:

In other words, the curvature of the entropy structure acts as the source of geometry—replacing the role played by the Einstein tensor in general relativity. Gravity, on this view, is not a background condition but a thermodynamic response to structured entropy flow.

Structural Insight. In TEQ, spacetime is not presupposed. It emerges from the structure defined by Axiom 0 and the constraint imposed by the Minimal Principle. Gravity arises as the thermodynamic geometry of resolvable distinctions—curvature is not a backdrop, but the outcome of constrained entropy flow.

Theorem 10 (Mass as Entropy-Curvature Resistance).

To preserve distinguishability under entropy curvature, a system must remain stable against entropic deformation. This sets a structural constraint: where:

κ denotes the entropy curvature—i.e., the second derivative of apparent entropy,

β is the entropy-sensitivity parameter,

and m represents the system’s effective mass.

This expresses the requirement that mass must be large enough to suppress destabilizing entropy gradients.

To relate this to spacetime structure, consider the entropy-weighted action’s invariance under infinitesimal coordinate transformations. Applying the principle of stationary action (as in Noether’s theorem) leads to a generalized balance condition between entropy-induced stress and entropy curvature:

If we assume the stress tensors are approximately aligned with the entropy curvature in the high-β regime, then structurally:

Interpretation: Mass arises not as a fundamental quantity but as a measure of a system’s resistance to deformation by entropy gradients. It quantifies how much entropy-stress is needed to sustain a given curvature in the entropy landscape. In this view, inertial mass is a geometrically emergent property linked to entropic stability.

Remark 13 (Mass as Curvature Buffer). In TEQ, mass quantifies resistance to entropy curvature. Like inertia in GR, it reflects how a system buffers structural deformation—but here it arises from entropy geometry, not spacetime metrics.

8. Core Principles from the Minimal Principle (MP)

This section articulates the Minimal Principle (MP) as the sole generative condition from which all physical structure in TEQ emerges. Rather than positing separate principles for quantization, dynamics, or measurement, TEQ derives them as consequences of a single requirement: stability of distinguishable structure under entropy flow. The MP replaces traditional axioms with a geometric criterion of resolvability. From this, the core architecture of physics—dynamics, probability, quantization, and curvature—unfolds as structurally necessary. The result is a radically minimal foundation, in which the diversity of physical phenomena reflects variations in entropy geometry, not multiplicity of laws.

TEQ does not begin with quantum postulates. It derives physical structure from a single generative constraint:

Minimal Principle (MP):

Physically realizable trajectories are those that maximize entropy distinguishability under structural constraints.

From this, all features of TEQ follow. Quantization, decoherence, probabilistic measurement, and curvature emerge as structural consequences of entropy-constrained variation.

MP1. Entropy–Action Coupling from Variational Structure

Applying MP to a constrained ensemble of paths yields amplitudes:

where

is the classical action,

is observer-resolvable entropy, and

,

arise as Lagrange multipliers.

MP2. Entropy-Weighted Path Selection

The effective amplitude becomes:

favoring entropy-stationary trajectories. Destructive interference suppresses unstable paths; coherence emerges from thermodynamic filtering (see

Appendix P for related dynamics in entropy-gradient systems).

MP3. Quantization from Entropy Geometry

Canonical commutation relations are deformed by entropy curvature:

with

the local entropy curvature. Quantization is thus a geometric stability condition—not an imposed algebra.

MP4. Entropy Resolution as Structural Gauge

The parameter defines observer resolution. Shifts in interpolate between coherent and dissipative regimes, acting as a gauge on entropy distinguishability.

MP5. Probability as Entropic Flatness

In the large-

limit, path probabilities approach:

with corrections from entropy curvature. Probability reflects geometric distinguishability—not intrinsic randomness.

Conclusion:

All structure in TEQ—quantization, measurement, decoherence, gravity—emerges from a single structural condition: the Minimal Principle. This unifies geometry, thermodynamics, and quantum theory within a coherent variational framework.

Postlude: Entropy as a Structural First Principle

With the entropy-geometry framework now assembled, we can step back to assess its structural scope and implications.

Scope and Limits. While this manuscript explicitly rederives key structures of quantum theory, thermodynamics, and elements of gravitational structure, it does not exhaust the full implications of TEQ. Several domains—including quantum field theory, holography, quantum information, and early-universe cosmology—are structurally implicated by the entropy geometry and the Minimal Principle but are reserved for future work. To avoid speculative overreach, this manuscript halts explicitly at the first closure of the entropy-action-gravity arc. Further developments may proceed modularly from this established foundation.

The Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework repositions entropy not as a thermodynamic byproduct, but as the structural foundation of physical law. At its core lie two generative axioms. Axiom 0 posits entropy as a prior constraint: a curvature-bearing structure over configuration space that defines which distinctions can, in principle, exist. Axiom 1, the Minimal Principle (MP), then selects those configurations that remain maximally distinguishable under finite entropy resolution.

This shift is both physical and philosophical. It reframes quantization, measurement, and spacetime not as postulates, but as emergent consequences of a more primitive condition: resolvability under entropy geometry. The constants ℏ, , and are no longer fundamental givens, but structural responses to this underlying constraint geometry.

From this perspective, the entropy-weighted path integral is not merely a computational tool. It defines a structural interface between ontology and epistemology: between what exists and what can be resolved. It encodes which distinctions are physically meaningful under constraints of entropy flow, resolution, and coherence.

This structural polarity—between emergence and collapse—is summarized in

Table 6, contrasting the forward and reverse flow of entropy in TEQ, from resolved structure to undifferentiated entanglement.

In this light, TEQ belongs to a broader movement toward information-based formulations of physics, but diverges by grounding information not in observers, bits, or priors, but in the geometric structure of entropy itself. The foundational question is not what evolves, but what distinctions persist within the generative limits set by entropy curvature.

Further extensions of this framework may address the emergence of time, the arrow of causality, and the role of observers. But the structural stance is clear: entropy is not a result of dynamics—it is the precondition for their emergence. Axiom 0 creates the space of possible structure; Axiom 1 selects its realized form.

Concluding Perspective: Entropy as Foundation

The Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework proposes a fundamental shift in how physical structure is understood. Rather than treating entropy as a byproduct of known dynamics, TEQ reverses the logic: structure, dynamics, and quantization emerge from entropy. At its core are two principles: a geometric field of entropy that defines which distinctions can be resolved (Axiom 0), and a minimal principle that selects the most stable among them (Axiom 1). From this, the familiar landscape of quantum mechanics—amplitudes, commutators, and unitary evolution—arises as a special case of entropy geometry.

This perspective reframes core questions in physics. Quantization is no longer a postulate, but a consequence of structural stability. The constants ℏ, , and are not inputs, but projections of coherence and resolution within an entropy-defined space. Decoherence, measurement, and even gravitation are reinterpreted as outcomes of entropy flow and curvature.

Beyond physics, this framework opens new connections to information theory, complexity, and the limits of distinguishability. It invites rethinking not only what physical systems do, but what it means for something to exist as a stable, resolvable structure.

Open Directions. This manuscript halts at the structural core. Many consequences of TEQ remain to be developed:

Entropic reformulations of quantum field theory and statistical mechanics;

Generalizations of entropy curvature in high-dimensional and strongly non-equilibrium regimes;

Connections to information-theoretic bounds and complexity constraints;

Further exploration of gravity as entropy-induced deformation, including black hole structure and cosmological evolution;

Operational formulations of observer resolution and entropy dimension transitions.

These directions are not peripheral extensions but follow naturally from the foundational principle: what is resolvable under entropy, becomes real. The TEQ framework provides a general and conceptually unified structure for exploring this principle across the full spectrum of physics and beyond.

Remark 14 (On Axioms and the Nature of Truth). Even if Axiom 0 and Axiom 1 do not name the ultimate source of reality—even if they are not “true” in an ontological sense—their power to generate quantum structure, gravitational curvature, and classical stability suggests something deeper. They function not as declarations of what is, but as constraints on what can coherently be resolved. In this role, they may be less foundations thanfixed points in a shifting sea of structure.

Philosophically, we may never know what is ultimately “true.” Ontology eludes us. But epistemology offers a different measure:truthiness. A structural principle that explains much, connects widely, and resists contradiction earns a high degree of epistemic plausibility. TEQ does not claim metaphysical certainty; it claims that from two simple axioms, an entire scaffold of physics falls into place—coherently, compactly, and without ad hoc assumptions.

In that light, even if the axioms one day yield to more refined insights, theirtruthinessremains. They may not be the last word, but they frame the question with uncommon clarity.

9. Conclusion and Outlook

This manuscript has introduced the Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework, grounded in two structural axioms. Axiom 0 posits entropy as a generative principle—a geometric constraint defining which configurations can stably distinguish themselves. In TEQ, entropy refers to a curvature-functional over distinguishability configurations, governing which structures persist under resolution. Axiom 1, the Minimal Principle (MP), selects among these those that remain maximally distinguishable under finite entropy resolution. Together, these axioms define a geometry of resolvability that replaces conventional postulates with structural constraints.

From this foundation, canonical features of quantum theory—including the Born rule, Schrödinger dynamics, quantization, and elements of gravitational structure—emerge as consequences of entropy-weighted variation. The result is a unified framework in which quantum coherence, classical emergence, and spacetime curvature arise from the same entropic structure.

Though this work focuses on TEQ in semiclassical regimes, several natural extensions remain open. In quantum field theory, entropy gradients may generalize to field configurations via entropy currents on fiber bundles. In quantum information, entropy-tensor flows may offer geometric analogues to entanglement, particularly in decohering systems. The role of entropy dimensionality in governing causal structure—and potential connections to holographic or thermodynamic gravity models—warrants further exploration.

These directions are not proposed as a personal research program, but as natural extrapolations of the structural logic presented here. This manuscript is offered as one formulation of a deeper principle, to be evaluated, refined, or reinterpreted by others.

Acknowledgment

This research was undertaken informally and independently during an ongoing period of cognitive and physical rehabilitation following a brain hemorrhage. It should be understood as part of a personal recovery process, not a professional research output. In that context, ChatGPT was used for grammar refinement, structural clarity, and conceptual dialogue. All theoretical developments, derivations, and conclusions are solely the author’s. This work is offered in the hope that, whatever its origin, the structural clarity it seeks may be of value.

Any credit belongs not to the author, but to the ideas themselves, to those able to advance them, and to the long tradition of thinkers—male and female—whose work made this one possible.

Appendix J Entropy-Weighted Path Integral Derivation

This appendix derives the entropy-weighted path integral as a variational solution, showing that the standard Feynman path integral emerges as a special case. Rather than postulating the exponential weighting of paths by classical action, we obtain this structure by maximizing path entropy under a constraint on average action. This approach extends Jaynes’ MaxEnt formalism [

7,

27] to the space of trajectories, and connects to earlier work exploring the thermodynamic and information-theoretic interpretation of path integrals [

28,

29]. In this view, the path integral reflects an entropy-maximizing inference over distinguishable trajectories, weighted by both dynamical and entropic constraints.

Path Distribution and Entropy Functional

Let

be a configuration path and

a probability distribution over such paths. Define the entropy functional:

We seek the distribution that maximizes this entropy, subject to:

Normalization:,

Average Action:,

where is the classical action functional associated with each path.

Variational Derivation

We introduce Lagrange multipliers

and

, and define the constrained entropy functional:

Taking the functional derivative and setting

, we obtain the stationary condition:

Solving for

, we find the Gibbs-like distribution:

Remark A15 (Beyond Jaynesian Inference).

While the form of the distribution resembles Jaynes’ MaxEnt derivation [7], in TEQ the entropy functional is not epistemic or informational in origin. Instead, it reflects a geometric constraint on resolvability itself, derived from the underlying entropy curvature. Thus, the exponential form arises not from inference under uncertainty, but from structural stability under entropy flow.

Entropy–Action Correspondence in TEQ

In the TEQ framework, the parameter is not fixed a priori. Rather:

: yields standard unitary quantum mechanics.

: encodes dissipative entropy suppression, relevant in decoherence and thermodynamic limits [

4,

5,

12].

: allows interpolations between unitary and non-unitary regimes, depending on the entropy balance.

TEQ generalizes the Feynman path integral by embedding it in a broader entropy-weighted variational structure. This connects coherent quantum dynamics to entropy-driven path selection, and reveals

ℏ as the scale at which action and entropy intersect. The influence functional formalism of Feynman and Vernon [

12] plays a key conceptual role here. It shows how tracing out environmental degrees of freedom induces effective damping of interference between alternative paths. In TEQ, this suppression is generalized: entropy curvature plays the structural role of biasing path weights, with decoherence arising as a special case of entropy-driven distinguishability loss.

Appendix J.1 Derivation of β as a Lagrange Multiplier from Entropy-Constrained Path Selection

In the TEQ framework, the parameter emerges naturally as a Lagrange multiplier enforcing entropy constraints in the path selection process. This derivation shows how arises from maximizing path entropy subject to constraints on both action and apparent entropy.

Appendix Entropy-Constrained Path Variational Principle

Let

be the path probability density functional over histories

. We impose the following constraints:

where

is the classical action and

is the entropy functional associated with each path.

We define the entropy of the path distribution as:

and extremize it with Lagrange multipliers

and

:

Taking the functional variation yields:

so that:

with normalization factor:

Recovery of the TEQ Amplitude and Born Rule

Identifying

, we obtain:

Thus, the TEQ path amplitude

is the exponential of the Lagrangian dual function. The

modulus squared of this amplitude,

recovers the path probability density. This confirms that

the Born rule arises naturally from the entropy-constrained variational principle, with

enforcing the entropy constraint and

ℏ setting the scale of phase sensitivity.

Appendix K Appendix: Deriving the Entropy Metric g(ϕ,ϕ ˙) from Entropy Geometry

The entropy-weighted action in TEQ introduces a deformation term:

where

quantifies entropy flux accessible to a finite-resolution observer along the trajectory

.

To derive a general, assumption-minimizing form for g, we impose the following structural constraints:

- (G1)

Locality:g depends only on the instantaneous state .

- (G2)

Positivity:, encoding directional entropy production or suppression.

- (G3)

Covariance:g transforms as a scalar under coordinate reparametrizations of configuration space.

- (G4)

Distinguishability Geometry: The entropy curvature defines a local metric structure over the tangent bundle.

Appendix K.2 Interpretation as an Entropic Fisher Metric

This construction connects to information geometry, where the Fisher information metric quantifies statistical distinguishability between infinitesimally nearby distributions:

for a family of distributions

on observable configurations [

28,

31,

32]. In this analogy,

captures how entropy curvature governs resolvability limits in velocity space. This perspective echoes ideas in thermodynamic geometry [

33,

34] and recent reconstructions of quantum theory from information-geometric foundations [

29].

Appendix K.3 Curvature and Entropic Stability

The second variation of

g defines the entropy curvature:

which appears directly in the entropy-deformed Poisson bracket and generalized quantization conditions (see

Section 4). Thus,

functions as an entropic analogue of an inertial tensor: it biases trajectory weights according to local geometric stability.

Appendix K.4 Summary and Outlook

We conclude that the entropy deformation term

should, under general structural and geometric constraints, take the form:

with

an emergent entropy-derived metric tensor encoding local distinguishability. This form supports rigorous derivations of entropy-weighted dynamics, deformation of canonical structures, and quantization from entropy geometry.

Appendix L Order-of-Magnitude Estimate for β in TEQ

We estimate the physical magnitude of the entropy–action coupling parameter

, assuming entropy is measured in units of the Boltzmann constant

. The parameter

plays a central role in the TEQ framework as a Lagrange multiplier that governs the weighting of paths by entropy relative to action (see

Appendix J).

Lemma A6 (Canonical Estimates of ). Let entropy be expressed in units of . Then in three key physical regimes, β takes the following characteristic values:

Corollary A9 (Thermodynamic Dominance in Classical Regimes). In the limit , TEQ reduces to classical deterministic behavior. The smallness of α explains the empirical absence of macroscopic superpositions and the stability of classical trajectories.

These estimates align with canonical results from statistical mechanics [

35], thermodynamic inference [

7], and quantum theory [

23], and provide the empirical foundation for interpreting TEQ’s scale-dependent behavior.

Appendix Gravitational and Cosmological Limits of β

In the TEQ framework, the Lagrange multiplier encodes the relative weight of entropy versus action in selecting physical trajectories. Extremal values of correspond to regimes where entropy geometry dominates—such as gravitational singularities, black hole horizons, and the early universe—where standard thermodynamic and quantum approximations may break down.

Theorem A11 (Gravitational Limit of Entropy Weighting).

In the high-temperature limit, , entropy weighting becomes negligible and classical dynamics dominate. As (Planck temperature), entropy curvature becomes dominant, signaling the breakdown of standard path integral approximations. A unified entropy-weighted geometry is required to describe such regimes [36].

Corollary A10 (Cosmological and Black Hole Regimes).

In black hole thermodynamics [37,38], gravitational decoherence [21,39], and early-universe cosmology [8,9], the entropy flow exhibits extreme curvature. In these limits, TEQ predicts observable corrections to the Born rule and commutation structure.

The Planck temperature

yields:

defining the lower bound of entropy sensitivity. In contrast, cosmological cooling or ultra-isolated systems yield large

, favoring entropy-stable and classically emergent dynamics.

Remark A16. TEQ interpolates between coherent quantum mechanics () and gravitational thermodynamics (). Entropy curvature serves as the geometric link, supporting a unified variational structure across quantum, thermodynamic, and gravitational domains [10].

Appendix M Derivation of Entropy-Deformed Symplectic Structure

This appendix derives the entropy-induced deformation of symplectic structure and its quantum counterpart. Starting from the entropy-weighted action, we show how both the Poisson bracket and commutator acquire entropy-curvature corrections. These results support the main discussion in

Section 4.

Appendix M.1 Poisson Bracket from Entropy-Weighted Momentum

We begin with the entropy-weighted action functional:

where

encodes entropy flux along the path (see

Appendix K).

The corresponding effective momentum is:

To assess deformation of the symplectic structure, we compute:

Assuming a standard quadratic kinetic term

, and

, we find:

Here,

characterizes local entropy curvature in velocity space, i.e., how distinguishability varies with infinitesimal changes in velocity.

Normalizing by mass and taking the real part:

This deformation recovers the canonical bracket in the limit

or

, and encodes the suppression of unstable paths under entropy-weighted dynamics.

Appendix M.2 Effective Commutator via Path Variation

To derive the entropy-corrected commutator without assuming canonical quantization, consider the entropy-weighted amplitude:

and expand the effective action to second order near a stable path:

This modifies the curvature of path fluctuations in momentum space, inducing an effective noncommutativity of the form:

Interpreting the fluctuation curvature as an effective inverse propagator, we infer that the entropy-weighted modification to phase-space area manifests as a rescaling of the effective commutator between and .

where the coefficient reflects reduced distinguishability between nearby paths under entropy-weighted evolution. This scaling arises from stability analysis of path fluctuations, analogous to the role of fluctuation-action curvature in effective action formalisms [

40,

41,

42,

43].

Thus, both the classical bracket and its quantum deformation emerge from entropy geometry rather than canonical assumptions. TEQ thereby unifies dynamical and statistical constraints in a variationally coherent framework, extending quantization to entropy-curved configuration spaces.

Appendix N Evaluation of the Entropy-Weighted Gaussian Path Integral

This appendix derives the leading-order approximation to the entropy-weighted path integral via a Gaussian expansion around the entropy-stationary path

, paralleling saddle-point methods in semiclassical quantum mechanics [

17,

18]. Similar Gaussian expansions have long played a role in semiclassical methods [

44,

45], while here they are adapted to entropy-weighted variational structure. This derivation supports Lemma 3, used in the Schrödinger derivation to justify replacing entropy gradients in velocity space with configuration-space gradients.

Appendix N.1 Quadratic Expansion Around Entropy-Stable Trajectory

Consider a trajectory expanded around the entropy-stationary path as

, where

minimizes the apparent entropy functional. A second-order expansion gives:

where the kernel

is the functional Hessian of the entropy landscape:

Lemma A7 (Leading-Order Approximation of the Entropy-Weighted Path Integral).

To leading order, the entropy-weighted path integral takes the form:

Appendix N.2 Reduction via Discretization

Discretizing time into

N intervals transforms the path integral into a finite-dimensional Gaussian:

where

is the discretized entropy-curvature matrix, with components

Theorem A12 (Gaussian Evaluation of Entropy-Weighted Integral).

Let denote a positive-definite entropy-curvature matrix. Then:

with normalization derived from the standard Gaussian integral.

Corollary A11 (Entropy-Curvature Dominance in Path Probability).

To leading order, the path probability scales as:

where is minimized and H quantifies local entropy curvature.

Appendix N.3 Interpretation and Structural Significance

This result is structurally analogous to the semiclassical stationary phase approximation in conventional path integrals, but here weighted by entropy geometry rather than oscillatory phase. It highlights two factors:

Dominant Suppression: The exponential term reflects entropy minimization across histories.

Fluctuation Curvature: The determinant encodes the local “stiffness” or curvature of entropy geometry around the dominant path.

Remark A17. The curvature correction modifies quantum probabilities and contributes directly to the generalized Born rule derived in Section 5. This reveals a direct link between entropy stability and the statistical structure of quantum measurement.

Paradigm Shift. In TEQ, the dominant contribution to quantum probabilities arises not from phase coherence alone, but from entropic stability. The Gaussian path integral reveals that both entropy minimization and entropy curvature govern the likelihood of quantum outcomes. This reframes quantum amplitudes as structurally constrained by thermodynamic geometry, embedding the Born rule within a variational entropy-weighted framework.

Appendix O Workarounds for Nonunitarity in Standard Quantum Theory and Their Structural Resolution in TEQ

While conventional quantum theory assumes unitary evolution, many physical processes exhibit apparently nonunitary behavior—such as measurement, decoherence, dissipation, and decay. These phenomena are typically addressed through a range of pragmatic workarounds that preserve unitary evolution at the formal level, while introducing auxiliary mechanisms—whether interpretive, phenomenological, or effective—to account for observable loss of coherence or probability.

In contrast, the Total Entropic Quantity (TEQ) framework treats nonunitarity as structurally emergent. The entropy-weighted variational principle introduces a complex deformation of the action, allowing for non-Hermitian dynamics whenever entropy flow disrupts phase coherence. In TEQ, unitarity is not a foundational postulate but a limiting case: it arises when entropy curvature vanishes and resolution is maximal (). This formulation permits a unified treatment of quantum coherence, decoherence, and dissipation as geometric consequences of entropy flow.

Table A1.

Standard treatments of nonunitarity compared to their structural resolution in the TEQ framework.

Table A1.