Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Antimicrobial Resistance [AMR] and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes [ARGs]

2.1. Mechanisms of Resistance

2.1.1. Enzymatic Degradation and β-Lactamases

2.1.2. Target Modification and Efflux Systems

2.1.3. Mobile Genetic Elements: Plasmids, Integrons, and Transposons

2.2. Diminished Permeability and Limited Uptake

2.3. Horizontal Gene Transfer [HGT]

| Mechanism of Resistance | Representative Genes or Enzymes | Mechanism of Action | Representative Antibiotics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enzymatic inactivation | blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M[ESBLs]; blaNDM, blaKPC, blaOXA-48 | Hydrolysis of β-lactam ring or other structural modification that inactivates the antibiotic | Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems | [31,32,33,45,46] |

| 2. Target modification | ermB [23S rRNA methylation]; qnrA/B/S [DNA gyrase protection]; tetM [ribosomal protection protein] | Alteration or protection of antibiotic binding sites reduces affinity for the drug target | Macrolides, Quinolones, Tetracyclines | [34] |

| 3. Efflux pump activation | Multidrug efflux systems — ABC, MFS, RND families [acrAB-tolC, norA, mexAB-oprM] | Active transport of antibiotics out of the cell, lowering intracellular concentration | Fluoroquinolones, Tetracyclines, Chloramphenicol | [47,48,49,50] |

| 4. Mobile genetic elements | Broad-host-range and conjugative plasmids [IncF, IncI, IncA/C types] | Horizontal transfer of ARGs via conjugation between bacteria | Multidrug resistance [across classes] | [51,52,53,54,55] |

| 5. Integrons | intI1 and associated gene cassettes | Site-specific recombination | Multiple antibiotic classes | [39,40] |

| 6. Transposons | Tn3, Tn21, and related insertion sequences | Movement of ARGs between plasmids and chromosomes | Multiple antibiotic classes. | [41,42] |

3. Environmental Interface and Migratory Birds in AMR Dissemination

4. Evidence of AMR in Migratory Birds and Associated Pathogens

4.1. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase [ESBL] Producers

4.2. Other Clinically Relevant Pathogens

4.2.1. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae [CRE]

4.2.2. Colistin Resistance [mcr Genes]

4.2.3. Zoonotic Pathogens

| Pathogen | Host group | Resistance category | Antibiotics affected | Tropical region / flyway interface | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Gulls, waterfowl, pigeons | ESBLs; MDR common; sporadic mcr | β-lactams, third-generation cephalosporins; colistin | Sub-Saharan Africa; South Asia [primary]; Europe [comparative] | [82,83,105,106,108] |

| Salmonella entericaserovar Corvallis | Raptors [black kite] | Carbapenemase [blaNDM-1] | Carbapenems | Africa–Eurasia flyway interface | [103,104] |

| Salmonellaspp. | Waterfowl, mixed wild birds | MDR; ESBL-associated | Multiple antibiotic classes | South Asia; Middle East | [85,86,87,158] |

| Campylobacterspp. | Shorebirds, waterfowl | Fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance | Fluoroquinolones, macrolides | East Asia [tropical–subtropical interface] | [125,160] |

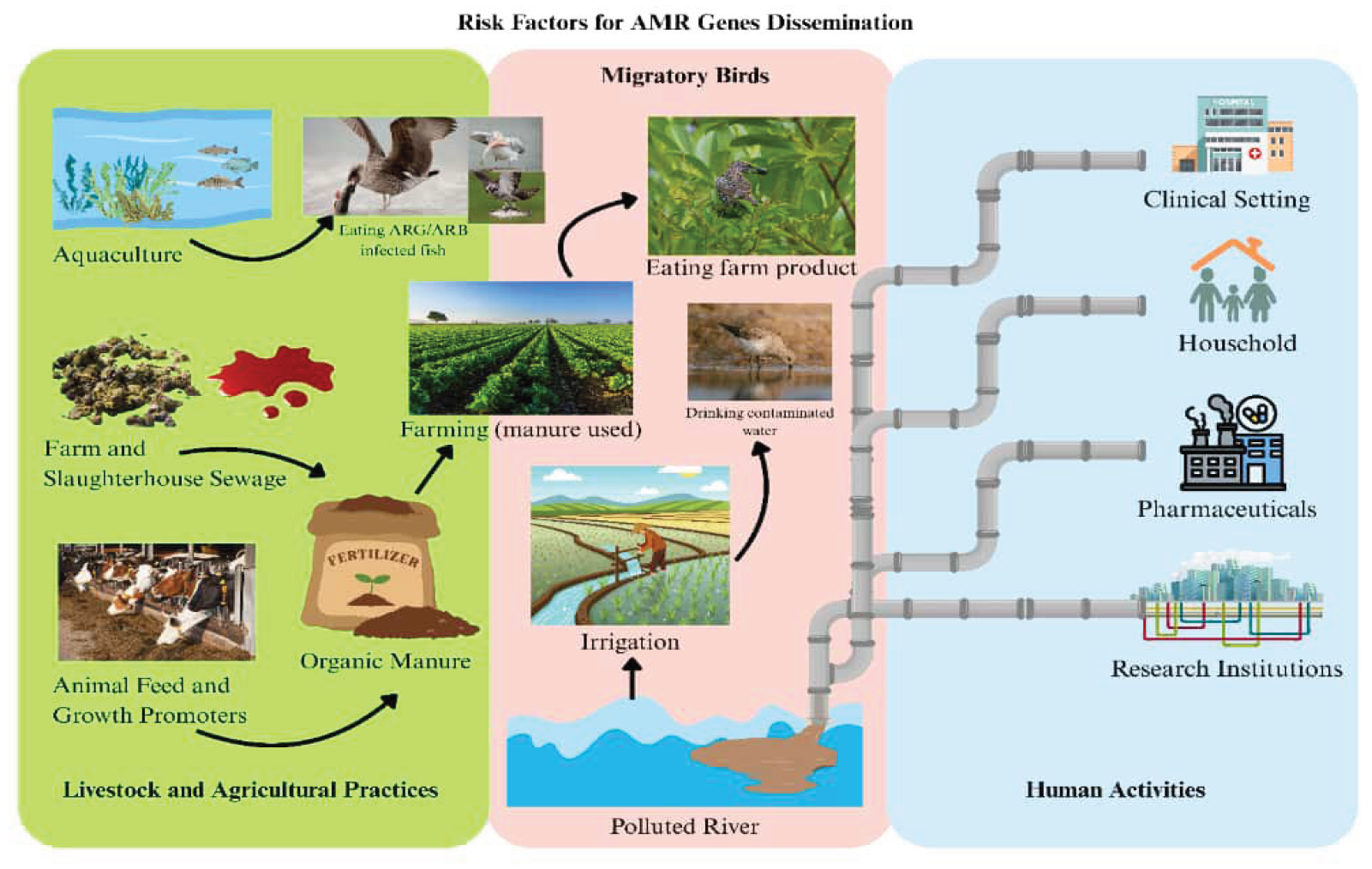

5. Risk Factors for Antimicrobial Resistance Genes [ARGs] Dissemination

5.1. Human Activity

5.1.1. Antibiotic Misuse in Clinical Settings

5.1.2. Urban Wastewater and Sewage as Hotspots

5.1.3. Ecotourism and Bird–Human Contact Zones

5.2. Livestock and Agricultural Practices

5.2.1. Antibiotics in Animal Feed and Aquaculture

5.2.2. Interaction Between Migratory Birds and Farm Environments

5.2.3. Spillover of Resistance Genes into the Food Chain

6. One Health Implications

6.1. Human Health

6.1.1. Spillover of Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens

6.1.2. Public Health Surveillance Gaps

6.2. Animal Health

6.2.1. Exposure of Domestic and Wild Animals

6.2.2. AMR Threat to Biodiversity and Veterinary Medicine

6.3. Environmental Health

6.3.1. Ecosystems as Persistent ARG Reservoirs

6.3.2. Long-Term Cycling and Evolution of Resistance

7. Perspective Piece: Recommendations and Future Directions

7.1. Strengthening AMR Surveillance in Migratory Bird Populations

7.2. Genomic and Metagenomic Approaches to Track ARGs

7.3. Integrated One Health Policies for AMR Control

7.4. Mitigation Strategies and Sustainable Interventions

7.5. Practical, Low-Cost Veterinary and Farm Biosecurity Measures

7.6. Integrating Climate-Sensitive Monitoring into AMR Surveillance

7.7. Ethical Considerations for Habitat-Level Interventions

8. Limitations

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Generative AI statement

Publisher’s note

References

- Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. p. 1946. [CrossRef]

- Barron M. The antimicrobial resistance pandemic: Breaking the silence. https://asm.org/articles/2024/october/antimicrobial-resistance-pandemic-breaking-silence.

- Naghavi M, Vollset SE, Ikuta KS, Swetschinski LR, Gray AP, Wool EE, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet. [2024] .

- Horefti E. The Importance of the One Health Concept in Combating Zoonoses. [CrossRef]

- Horvat O, Kovačević Z. Human and Veterinary Medicine Collaboration: Synergistic Approach to Address Antimicrobial Resistance Through the Lens of Planetary Health. Antibiotics. [2025] 14:38. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS microbiology reviews. [2018] 42:68–80. [CrossRef]

- James R, Hardefeldt LY, Ierano C, Charani E, Dowson L, Elkins S, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship from a One Health perspective. Nature reviews. Microbiology. [2025] . [CrossRef]

- Bustamante M, Mei S, Daras IM, Doorn GS, Falcao Salles J, Vos MGJ. An eco-evolutionary perspective on antimicrobial resistance in the context of One Health. iScience. [2024] 28:111534. [CrossRef]

- Tokuda M, Shintani M. Microbial evolution through horizontal gene transfer by mobile genetic elements. Microbial biotechnology. [2024] 17:14408. [CrossRef]

- Goh YX, Anupoju SMB, Nguyen A. Evidence of horizontal gene transfer and environmental selection impacting antibiotic resistance evolution in soil-dwelling Listeria. Nat Commun. [2024] 15:10034. [CrossRef]

- Johansson MHK, Aarestrup FM, Petersen TN. Importance of mobile genetic elements for dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in metagenomic sewage samples across the world. PloS one. [2023] 18:0293169. [CrossRef]

- Jarma D, Sánchez MI, Green AJ, Peralta-Sánchez JM, Hortas F, Sánchez-Melsió A, et al. Faecal microbiota and antibiotic resistance genes in migratory waterbirds with contrasting habitat use. Science of The Total Environment. [2021] 783:146872. [CrossRef]

- Franklin AB, Ramey AM, Bentler KT, Barrett NL, McCurdy LM, Ahlstrom CA, et al. Gulls as Sources of Environmental Contamination by Colistin-resistant Bacteria. Scientific Reports. [2020] 10:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mbuthia CW, Hoza AS. Wild birds as potential reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli: A systematic review. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2025] 16:1615826. [CrossRef]

- Ramey AM. Antimicrobial resistance: Wildlife as indicators of anthropogenic environmental contamination across space and through time. Current Biology. [2021] 31:R1385–R1387. [CrossRef]

- Łopińska A, Nowak-Zaleska A, Kosicki JZ, Jerzak L, Węgrzyn A, Węgrzyn G. Reassessing the role of wild birds in the spread of antibiotic resistance: the white stork as a model species in studying populations from Central European river valley. Microbiology Spectrum. [2025] . [CrossRef]

- Lisovski S, Hoye BJ, Conklin JR, Battley PF, Fuller RA, Gosbell KB, et al. Predicting resilience of migratory birds to environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [2024] 121:2311146121. [CrossRef]

- Elsohaby I, Samy A, Elmoslemany A, Alorabi M, Alkafafy M, Aldoweriej A, et al. Migratory Wild Birds as a Potential Disseminator of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria around Al-Asfar Lake, Eastern Saudi Arabia. Antibiotics. [2021] 10:260. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Dong X, Sun R, Wu J, Tian L, Rao D, et al. Migratory birds-one major source of environmental antibiotic resistance around Qinghai Lake, China. Science of the Total Environment. [2020] 739:139758. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Y, Liang B, Jiang BW, Zhu LW, Wang TC, Li YG, et al. Migratory wild birds carrying multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli as potential transmitters of antimicrobial resistance in China. PloS one. [2021] 16:0261444. [CrossRef]

- Danasekaran R. One Health: A Holistic Approach to Tackling Global Health Issues. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. [2024] 49:260–263. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ruiz S, Santos N, Barasona JA, Fine AE, Jori F. Pathogen transmission at the domestic-wildlife interface: a growing challenge that requires integrated solutions. Frontiers in veterinary science. [2024] 11:1415335. [CrossRef]

- Guardia T, Varriale L, Minichino A, Balestrieri R, Mastronardi D, Russo TP, et al. Wild birds and the ecology of antimicrobial resistance: an approach to monitoring. Journal of Wildlife Management. [2024] 88:. [CrossRef]

- Skarżyńska M, C Z, M. B, A. B, Ł. K, W. P, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Glides in the Sky-Free-Living Birds as a Reservoir of Resistant Escherichia coli With Zoonotic Potential. Frontiers in microbiology. [2021] 12:656223. [CrossRef]

- Zeballos-Gross D, Rojas-Sereno Z, Salgado-Caxito M, Poeta P, Torres C, Benavides JA. The Role of Gulls as Reservoirs of Antibiotic Resistance in Aquatic Environments: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2021] 12:. [CrossRef]

- Reygaert WC. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiology. [2018] 4:482–501. [CrossRef]

- Christaki E, Marcou M, Tofarides A. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria: mechanisms, evolution, and persistence. Journal of molecular evolution. [2020] Jan;88[1]:26-40:.

- Varela MF, Stephen J, Lekshmi M, Ojha M, Wenzel N, Sanford LM, et al. Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents. Antibiotics. [2021] 10:593. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Luo J, Chen X, Liu W, Chen T. Cell Membrane Coating Technology: A Promising Strategy for Biomedical Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. [2019] 11:100. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ochomogo M, Lohans CT. β-Lactam Antibiotic Targets and Resistance mechanisms: from Covalent Inhibitors to Substrates. RSC Medicinal Chemistry. [2021] 12:1623–1639. [CrossRef]

- Sawa T, Kooguchi K, Moriyama K. Molecular Diversity of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases, and Antimicrobial Resistance. Journal of Intensive Care. [2020] 8:. [CrossRef]

- Bush K, Jacoby GA. Updated Functional Classification of -Lactamases. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. [2010] 54:969–976. [CrossRef]

- Philippon A, Arlet G, Labia R, Iorga BI. Class C β-Lactamases: Molecular Characteristics. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. [2022] 35:. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Zhou D, Steitz TA, Polikanov YS, Gagnon MG. Ribosome-Targeting Antibiotics: Modes of Action, Mechanisms of Resistance, and Implications for Drug Design. Annual Review of Biochemistry. [2018] 87:451–478.

- Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. [2018] 31:. [CrossRef]

- Galgano M, Pellegrini F, Catalano E, Capozzi L, Sambro LD, Sposato A, et al. Acquired Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics and Resistance Genes: From Past to Future. Antibiotics. [2025] 14:222. [CrossRef]

- Vrancianu CO, Popa LI, Bleotu C, Chifiriuc MC. Targeting Plasmids to Limit Acquisition and Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2020] 11:. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Barba S, Top EM, Stalder T. Plasmids, a molecular cornerstone of antimicrobial resistance in the One Health era. Nature Reviews Microbiology. [2023] 22:. [CrossRef]

- Bhat BA, Mir RA, Qadri H, Dhiman R, Almilaibary A, Alkhanani M, et al. Integrons in the development of antimicrobial resistance: critical review and perspectives. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2023] 14:. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy EE, ElNaghy WS, Shalaby MM, Shoeib SM, Abdeen NSM, Fouda MH, et al. Study of Class 1, 2, and 3 Integrons, Antibiotic Resistance Patterns, and Biofilm Formation in Clinical Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Hospital-Acquired Infections. Pathogens. [2025] 14:705. [CrossRef]

- Babakhani S, Oloomi M. Transposons: the agents of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Journal of Basic Microbiology. [2018] 58:905–917. [CrossRef]

- Shintani M, Vestergaard G, Milaković M, Kublik S, Smalla K, Schloter M, et al. Integrons, transposons and IS elements promote diversification of multidrug resistance plasmids and adaptation of their hosts to antibiotic pollutants from pharmaceutical companies. Environmental Microbiology. [2023] 25:3035–3051. [CrossRef]

- Sinha S, Upadhyay LS. Understanding antimicrobial resistance [AMR] mechanisms and advancements in AMR diagnostics. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. [2025] 16:.

- Nazir A, Nazir A, Zuhair V, Aman S, Sadiq SUR, Hasan AH, et al. The Global Challenge of Antimicrobial Resistance: Mechanisms. Case Studies, and Mitigation Approaches. Health Science Reports. [2025] 8:71077.

- Paudel R, Shrestha E, Chapagain B, Tiwari BR. Carbapenemase producing Gram negative bacteria: Review of resistance and detection methods. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. [2024] 110:116370. [CrossRef]

- Halat DH, Moubareck CA. The Current Burden of Carbapenemases: Review of Significant Properties and Dissemination among Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics. [2020] 9:186. [CrossRef]

- Nishino K, Yamasaki S, Nakashima R, Zwama M, Hayashi-Nishino M. Function and Inhibitory Mechanisms of Multidrug Efflux Pumps. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2021] 12:. [CrossRef]

- Huang YS, Zhou H. Breakthrough Advances in Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: New Synthesized Compounds and Mechanisms of Action Against Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Pharmaceuticals. [2025] 18:206. [CrossRef]

- Gaurav A, Bakht P, Saini M, Pandey S, Pathania R. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology. [2023] 169:001333. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Gupta VK, Pathania R. Efflux pump inhibitors for bacterial pathogens. Indian J Med Res. [2019] 149:129–145. [CrossRef]

- Brown CJ, Sen D, Yano H, Bauer ML, Rogers L, Van, et al. Diverse Broad-Host-Range Plasmids from Freshwater Carry Few Accessory Genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. [2013] 79:7684–7695. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay JP, Kwong SM, Murphy RJT, Yui Eto K, Price KJ, Nguyen QT, et al. An updated view of plasmid conjugation and mobilization in Staphylococcus. Mobile Genetic Elements. [2016] 6:. [CrossRef]

- Tokuda M, Suzuki H, Yanagiya K, Yuki M, Inoue K, Ohkuma M, et al. Determination of Plasmid pSN1216-29 Host Range and the Similarity in Oligonucleotide Composition Between Plasmid and Host Chromosomes. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2020] 11:. [CrossRef]

- Foley SL, Kaldhone PR, Ricke SC, Han J. Incompatibility Group I1 [IncI1] Plasmids: Their Genetics, Biology, and Public Health Relevance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. [2021] 85:. [CrossRef]

- Virolle C, Goldlust K, Djermoun S, Bigot S, Lesterlin C. Plasmid Transfer by Conjugation in Gram-Negative Bacteria: From the Cellular to the Community Level. Genes. [2020] 11:1239. [CrossRef]

- Atmakuri A, Yadav B, Tiwari B, Drogui P, Tyagi RD, Wong JW. Nature’s architects: a comprehensive review of extracellular polymeric substances and their diverse applications. Waste Disposal & Sustainable Energy. [2024] Dec;6[4]:529-51:.

- Liu W, Huang Y, Zhang H, Liu Z, Huan Q, Xiao X, et al. Factors and Mechanisms Influencing Conjugation In Vivo in the Gastrointestinal Tract Environment: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. [2023] 24:5919. [CrossRef]

- Boyd SE, Holmes A, Peck R, Livermore DM, Hope WW. OXA-48-Like β-Lactamases: Global Epidemiology, Treatment Options, and Development Pipeline. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. [2022] 66:. [CrossRef]

- Xia C, Yan R, Liu C, Zhai J, Zheng J, Chen W, et al. Epidemiological and genomic characteristics of global blaNDM-carrying Escherichia coli. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. [2024] 23:. [CrossRef]

- Baquero F, Martínez JL. Interventions on metabolism: Making antibiotic-susceptible bacteria. mBio. [2017] 8:. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer MUG, Reiner Jr RC, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Gilbert M, Pigott DM, et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nature microbiology. [2019] 4:854–863. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang M, Yan W, Xiong Y, Wu Z, Cao Y, Sanganyado E, et al. Horizontal plasmid transfer promotes antibiotic resistance in selected bacteria in Chinese frog farms. Environment International. [2024] 190:108905. [CrossRef]

- Allen R, Yokota T. Endosomal Escape and Nuclear Localization: Critical Barriers for Therapeutic Nucleic Acids. Molecules [Basel. [2024] 29:5997. [CrossRef]

- Wellington EMH, Boxall ABA, Cross P, Feil EJ, Gaze WH, Hawkey PM, et al. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. [2013] 13:155–165. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Huang J, Zhao Z, Cao Y, Li B. Hospital Wastewater as a Reservoir for Antibiotic Resistance Genes: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Public Health. [2020] 8:574968. [CrossRef]

- Huijbers PMC, Blaak H, De Jong MCM, Graat EAM, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, De Roda Husman AM. Role of the Environment in the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance to Humans: A Review. Environmental science & technology. [2015] 49:11993–12004. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo L, Manaia C, Merlin C, Schwartz T, Dagot C, Ploy MC, et al. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Science of the Total Environment. [2013] 447:345–360. [CrossRef]

- Karkman A, Pärnänen K, Larsson DGJ. Fecal pollution can explain antibiotic resistance gene abundances in anthropogenically impacted environments. Nature Communications 2019 10:1. [2019] 10:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Sun R, Yu P, Alvarez PJJ. High levels of antibiotic resistance genes and opportunistic pathogenic bacteria indicators in urban wild bird feces. Environmental Pollution. [2020] 266:115200. [CrossRef]

- Atterby C, Börjesson S, Ny S, Järhult JD, Byfors S, Bonnedahl J. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in Swedish gulls-A case of environmental pollution from humans? PloS One. [2017] 12:. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Li R, Xiao X, Wang Z. Molecules that Inhibit Bacterial Resistance Enzymes. Molecules. [2018] 24:43. [CrossRef]

- Muteeb G, Rehman T, Shahwan M, Aatif M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals. [2023] 16:1615. https://doi.org/https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10675245/.

- Meradji S, Basher NS, Sassi A, Ibrahim NA, Idres T, Touati A. The Role of Water as a Reservoir for Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Antibiotics. [2025] 14:763. [CrossRef]

- Adekanmbi AO, Akinpelu MO, Olaposi A V, Oyelade AA. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase encoding gene-fingerprints in multidrug resistant Escherichia coli isolated from wastewater and sludge of a hospital treatment plant in Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Studies. [2020] 78:140–150. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim E, Mkwanda C, Masoambeta E, Scudeller L, Kostyanev T, Twabi HH, et al. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae in Wastewater Effluent in Blantyre, Malawi. Antibiotics. [2025] 14:562. [CrossRef]

- Nwankwoala HO, Okujagu DC. A REVIEW OF WETLANDS AND COASTAL RESOURCES OF THE NIGER DELTA: POTENTIALS, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS. Environment & Ecosystem Science. [2021] 5:37–46. [CrossRef]

- Monsalves N, Leiva AM, Gómez G, Vidal G. Antibiotic-Resistant Gene Behavior in Constructed Wetlands Treating Sewage: A Critical Review. Sustainability. [2022] 14:8524. [CrossRef]

- Mei X. Effect of Climate Change and Loss of Habitat on Migratory Birds. Transactions on Environment, Energy and Earth Sciences. [2024] 3:288–293. [CrossRef]

- Blanco G, López-Hernández I, Morinha F, López-Cerero L. Intensive farming as a source of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents in sedentary and migratory vultures: Implications for local and transboundary spread. The Science of the Total Environment. [2020] 739:140356. [CrossRef]

- Anjum MF, Schmitt H, Börjesson S, Berendonk TU, Donner E, Stehling EG, et al. The potential of using E. coli as an indicator for the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance [AMR] in the environment. Current Opinion in Microbiology. [2021] 64:152–158. [CrossRef]

- Anjum MF, Duggett NA, AbuOun M, Randall L, Nunez-Garcia J, Ellis RJ, et al. Colistin resistance in Salmonella and Escherichia coli isolates from a pig farm in Great Britain. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. [2016] 71:2306–2313. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed ZS, Elshafiee EA, Khalefa HS, Kadry M, Hamza DA. Evidence of colistin resistance genes [mcr-1 and mcr-2] in wild birds and its public health implication in Egypt. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control. [2019] 8:. [CrossRef]

- Mohsin M, Raza S, Schaufler K, Roschanski N, Sarwar F, Semmler T, et al. High prevalence of CTX-M-15-Type ESBL-Producing E. coli from migratory avian species in Pakistan. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2017] 8:285845. [CrossRef]

- Vergara A, Pitart C, Montalvo T, Roca I, Sabaté S, Hurtado JC, et al. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase- and/or Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Yellow-Legged Gulls from Barcelona, Spain. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. [2017] 61:e02071-16. [CrossRef]

- Card RM, Chisnall T, Begum R, Sarker MS, Hossain MS, Sagor MS, et al. Multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella of public health significance recovered from migratory birds in Bangladesh. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2023] 14:1162657. [CrossRef]

- Shalaby AG, Erfan M, Nasef S. Surveillance for Salmonella in migratory, feral and zoo birds. Suez Canal Veterinary Medical Journal. SCVMJ. [2014] 19:85–101. [CrossRef]

- Al-baqir A, Hussein A, Ghanem I, Megahed M. Characterization of Paratyphoid Salmonellae Isolated from Broiler Chickens at Sharkia Governorate. Egypt. Zagazig Veterinary Journal. [2019] 47:183–192. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer S, Globig A, Bachmann L, Schütz AK, Schaufler K, Homeier-Bachmann T. Longitudinal Study on Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-E. coli in Sentinel Mallard Ducks in an Important Baltic Stop-Over Site for Migratory Ducks in Germany. Microorganisms. [2022] 10:. [CrossRef]

- Segawa T, Takahashi A, Kokubun N, Ishii S. Spread of antibiotic resistance genes to Antarctica by migratory birds. Science of The Total Environment. [2024] 923:171345. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z, Chen Y, Li M, Lv C, Zhou N, Chen W, et al. An Unusual “Gift” from Humans: Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Enterobacterales in migratory birds along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. Environment International. [2025] 197:109320. [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom CA, Bonnedahl J, Woksepp H, Hernandez J, Olsen B, Ramey AM. Acquisition and dissemination of cephalosporin-resistant E. coli in migratory birds sampled at an Alaska landfill as inferred through genomic analysis. Scientific Reports. [2018] 8:7361. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Jia R, Ma R, Li J, Wu S, Fan Y, et al. High throughput screening for human disease associated-pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in migratory birds at ten habitat sites in China. BMC Microbiology. [2025] 25:355. [CrossRef]

- Rapi MC, Filipe J, Filippone Pavesi L, Raimondi S, Addis MF, Franciosini MP, et al. Resisting the Final Line: Phenotypic Detection of Resistance to Last-Resort Antimicrobials in Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from Wild Birds in Northern Italy. Animals. [2025] 15:2289. [CrossRef]

- Benavides JA, Salgado-Caxito M, Torres C, Godreuil S. Public Health Implications of Antimicrobial Resistance in Wildlife at the One Health Interface. Medical Sciences Forum. [2024] 25:1. [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom CA, Toor ML, Woksepp H, Chandler JC, Reed JA, Reeves AB, et al. Evidence for continental-scale dispersal of antimicrobial resistant bacteria by landfill-foraging gulls. Science of The Total Environment. [2021] 764:144551. [CrossRef]

- Atterby C, Ramey AM, Hall GG, Järhult J, Börjesson S, Bonnedahl J. Increased prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in gulls sampled in Southcentral Alaska is associated with urban environments. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. [2016] 6:32334. [CrossRef]

- Stedt J, Bonnedahl J, Hernandez J, McMahon BJ, Hasan B, Olsen B, et al. Antibiotic resistance patterns in Escherichia coli from gulls in nine European countries. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. [2014] 4:21565. [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Hu Y, Liu F, Wang Y, Bi Y, Lv N, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals the microbiome and resistome in migratory birds. Microbiome. [2020] 8:26. [CrossRef]

- Katale BZ, Misinzo G, Mshana SE, Chiyangi H, Campino S, Clark TG, et al. Genetic diversity and risk factors for the transmission of antimicrobial resistance across human, animals and environmental compartments in East Africa: A review. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. [2020] 9:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Laborda P, Sanz-García F, Ochoa-Sánchez LE, Gil-Gil T, Hernando-Amado S, Martínez JL. Wildlife and Antibiotic Resistance. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. [2022] 12:873989. [CrossRef]

- Blount JD, Horns JJ, Kittelberger KD, Neate-Clegg MHC, Şekercioğlu ÇH. Avian Use of Agricultural Areas as Migration Stopover Sites: A Review of Crop Management Practices and Ecological Correlates. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. [2021] 9:. [CrossRef]

- Carattoli A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. [2013] 303:298–304. [CrossRef]

- Villa L, Guerra B, Schmoger S, Fischer J, Helmuth R, Zong Z, et al. IncA/C Plasmid Carrying blaNDM-1 , blaCMY-16 , and fosA3 in a Salmonella enterica Serovar Corvallis Strain Isolated from a Migratory Wild Bird in Germany. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. [2015] 59:6597–6600. [CrossRef]

- Fischer J, Schmoger S, Jahn S, Helmuth R, Guerra B. NDM-1 carbapenemase-producing Salmonella enterica subsp. Enterica serovar Corvallis isolated from a wild bird in Germany. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. [2013] 68:2954–2956. [CrossRef]

- Ruzauskas M, Vaskeviciute L. Detection of the mcr-1 gene in Escherichia coli prevalent in the migratory bird species Larus argentatus. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. [2016] 71:2333–2334. [CrossRef]

- Liakopoulos A, Mevius DJ, Olsen B, Bonnedahl J. The colistin resistance mcr-1 gene is going wild: Table 1. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. [2016] 71:2335–2336. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee P, Chauhan N, Jain U. Confronting antibiotic-resistant pathogens: Distinctive drug delivery potentials of progressive nanoparticles. Microbial Pathogenesis. [2024] 187:106499. [CrossRef]

- Fashae K, Engelmann I, Monecke S, Braun SD, Ehricht R. Molecular characterisation of extended-spectrum ß-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in wild birds and cattle, Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Veterinary Research. [2021] 17:33. [CrossRef]

- Luangtongkum T, Jeon B, Han J, Plummer P, Logue CM, Zhang Q. Antibiotic Resistance in Campylobacter: Emergence, Transmission and Persistence. Future Microbiology. [2009] 4:189–200. [CrossRef]

- Smith JL, Fratamico PM. Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Campylobacter. Journal of Food Protection. [2010] 73:1141–1152. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis K, Allende A, Álvarez-Ordóñez A, Bolton D, Bover-Cid S, Chemaly M, et al. Role played by the environment in the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance [AMR] through the food chain. EFSA Journal. [2021] 19:06651. [CrossRef]

- Lan L, Wang Y, Chen Y, Wang T, Zhang J, Tan B. A Review on the Prevalence and Treatment of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Hospital Wastewater. Toxics. [2025] 13:263. [CrossRef]

- Gao P, Munir M, Xagoraraki I. Correlation of tetracycline and sulfonamide antibiotics with corresponding resistance genes and resistant bacteria in a conventional municipal wastewater treatment plant. Science of The Total Environment. [2012] 421–422:173–183. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Shuai XY, Lin ZJ, Sun YJ, Zhou ZC, Meng LX, et al. Landscape of genes in hospital wastewater breaking through the defense line of last-resort antibiotics. Water Research. [2022] 209:. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Wang Z, Chen Z, Liang H, Li X, Li B. Occurrence and Removal of Antibiotic Resistance in Nationwide Hospital Wastewater Deciphered by Metagenomics Approach — China, 2018–2022. China CDC Weekly. [2023] 5:1023. [CrossRef]

- Majumder A, Gupta AK, Ghosal PS, Varma M. A review on hospital wastewater treatment: A special emphasis on occurrence and removal of pharmaceutically active compounds, resistant microorganisms, and SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. [2020] 9:104812. [CrossRef]

- Venter H, Henningsen ML, Begg SL. Antimicrobial resistance in healthcare, agriculture and the environment: the biochemistry behind the headlines. Essays in Biochemistry. [2017] 61:1. [CrossRef]

- Singer AC, Shaw H, Rhodes V, Hart A. Review of antimicrobial resistance in the environment and its relevance to environmental regulators. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2016] 7:219380. [CrossRef]

- Sabri NA, Schmitt H, Zaan B, Gerritsen HW, Zuidema T, Rijnaarts HHM, et al. Prevalence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater effluent-receiving river in the Netherlands. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. [2020] 8:102245. [CrossRef]

- Oteo J, Menciá A, Bautista V, Pastor N, Lara N, González-González F, et al. Colonization with Enterobacteriaceae-Producing ESBLs, AmpCs, and OXA-48 in Wild Avian Species, Spain 2015-2016. Microbial Drug Resistance. [2018] 24:932–938. [CrossRef]

- Ikuta LA, Blumstein DT. Do fences protect birds from human disturbance? Biological Conservation. [2003] 112:447–452. [CrossRef]

- Steven R, Pickering C, Guy Castley J. A review of the impacts of nature based recreation on birds. Journal of Environmental Management. [2011] 92:2287–2294. [CrossRef]

- Muehlenbein MP. Human-Wildlife Contact and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Human-Environment Interactions. [2012] 1:79. [CrossRef]

- Tawakol MM, Nabil NM, Samir A, Hassan HM, Reda RM, Abdelaziz O, et al. Role of migratory birds as a risk factor for the transmission of multidrug resistant Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli to broiler poultry farms and its surrounding environment. BMC Research Notes. [2024] 17:314. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Jia R, Wang Y, Li J, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Prevalence, Diversity, and Virulence of Campylobacter Carried by Migratory Birds at Four Major Habitats in China. Pathogens. [2024] 13:230. [CrossRef]

- Allcock S, Young EH, Holmes M, Gurdasani D, Dougan G, Sandhu MS, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in human populations: challenges and opportunities. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics. [2017] 2:4. [CrossRef]

- Rahman AU, Valentino V, Sequino G, Ercolini D, Filippis F. Comparative analysis of antibiotic-administered vs. antibiotic-free farming in meat production: Implications for health, environment, and antibiotic resistance. Food Microbiology. [2025] 133:104877. [CrossRef]

- Berendsen BJA, Wegh RS, Memelink J, Zuidema T, Stolker LAM. The analysis of animal faeces as a tool to monitor antibiotic usage. Talanta. [2015] 132:258–268. [CrossRef]

- Karami N, Martner A, Enne VI, Swerkersson S, Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Transfer of an ampicillin resistance gene between two Escherichia coli strains in the bowel microbiota of an infant treated with antibiotics. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. [2007] 60:1142–1145. [CrossRef]

- Wichmann F, Udikovic-Kolic N, Andrew S, Handelsman J. Diverse antibiotic resistance genes in dairy cow manure. MBio. [2014] 5:1017–1030. [CrossRef]

- Smith SD, Colgan P, Yang F, Rieke EL, Soupir ML, Moorman TB, et al. Investigating the dispersal of antibiotic resistance associated genes from manure application to soil and drainage waters in simulated agricultural farmland systems. PLOS ONE. [2019] 14:0222470. [CrossRef]

- Cong X, Krolla P, Khan UZ, Savin M, Schwartz T. Antibiotic resistances from slaughterhouse effluents and enhanced antimicrobial blue light technology for wastewater decontamionation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. [2023] 30:109315. [CrossRef]

- Savin M, Bierbaum G, Hammerl JA, Heinemann C, Parcina M, Sib E, et al. ESKAPE Bacteria and Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Wastewater and Process Water from German Poultry Slaughterhouses. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. [2020] 86:. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Mi J, Yan Q, Wen X, Zhou S, Wang Y, et al. Animal manures application increases the abundances of antibiotic resistance genes in soil-lettuce system associated with shared bacterial distributions. Science of The Total Environment. [2021] 787:147667. [CrossRef]

- Vezeau N, Kahn L. Spread and mitigation of antimicrobial resistance at the wildlife-urban and wildlife-livestock interfaces. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. [2024] 262:741–747. [CrossRef]

- Osińska A, Korzeniewska E, Harnisz M, Felis E, Bajkacz S, Jachimowicz P, et al. Small-scale wastewater treatment plants as a source of the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in the aquatic environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials. [2020] 381:121221. [CrossRef]

- Founou LL, Founou RC, Essack SY. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology. [2016] 7:232834. [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty E, Solimini AG, Pantanella F, De Giusti M, Cummins E. Human exposure to antibiotic resistant-Escherichia coli through irrigated lettuce. Environment International. [2019] 122:270–280. [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira A, Silva J, Teixeira P. Lettuce and fruits as a source of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter spp. Food Microbiology. [2017] 64:119–125. [CrossRef]

- Ramey AM, Hernandez J, Tyrlöv V, Uher-Koch BD, Schmutz JA, Atterby C, et al. Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia coli in Migratory Birds Inhabiting Remote Alaska. EcoHealth. [2018] 15:72–81. [CrossRef]

- Jindal M, Stone H, Lim S, MacIntyre CR. A Geospatial Perspective Toward the Role of Wild Bird Migrations and Global Poultry Trade in the Spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1. GeoHealth. [2025] 9:1296–2024. [CrossRef]

- Mourkas E, Valdebenito JO, Marsh H, Hitchings MD, Cooper KK, Parker CT, et al. Proximity to humans is associated with antimicrobial-resistant enteric pathogens in wild bird microbiomes. Current Biology. [2024] 34:3955-3965 4. [CrossRef]

- Perrin A, Glaizot O, Christe P. Migratory birds spread their haemosporidian parasites along the world’s major migratory flyways. Oikos. [2025] 2025:e11012. [CrossRef]

- Farkas K, Knight ME, Woodhall N, Williams RC, Seerung W, Silvester R, et al. Monitoring of antimicrobial resistance genes and influenza viruses in avian-populated water bodies. Sustainable Microbiology. [2025] 2:013. [CrossRef]

- Blagodatski A, Trutneva K, Glazova O, Mityaeva O, Shevkova L, Kegeles E, et al. Avian Influenza in Wild Birds and Poultry: Dissemination Pathways, Monitoring Methods, and Virus Ecology. Pathogens. [2021] 10:630. [CrossRef]

- Gómez C, Hobson KA, Bayly NJ, Rosenberg K V, Morales-Rozo A, Cardozo P, et al. Migratory connectivity then and now: A northward shift in breeding origins of a long-distance migratory bird wintering in the tropics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. [2021] 288:2021–2188, 20210188. [CrossRef]

- Kiat Y, Izhaki I, Sapir N. The effects of long-distance migration on the evolution of moult strategies in Western-Palearctic passerines. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. [2019] 94:700–720. [CrossRef]

- Ramey AM, Hill NJ, DeLiberto TJ, Gibbs SEJ, Camille Hopkins M, Lang AS, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza is an emerging disease threat to wild birds in North America. The Journal of Wildlife Management. [2022] 86:22171. [CrossRef]

- Shi X, Soderholm J, Chapman JW, Meade J, Farnsworth A, Dokter AM, et al. Distinctive and highly variable bird migration system revealed in Eastern Australia. Current Biology. [2024] 34:5359-5365 3. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Lv C, Chen J, Sun Y, Tang T, Zhang Y, et al. The global distribution and diversity of wild-bird-associated pathogens: An integrated data analysis and modeling study. Med. [2025] 6:100553. [CrossRef]

- Zurfluh K, Albini S, Mattmann P, Kindle P, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Stephan R, et al. Antimicrobial resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in common wild bird species in Switzerland. MicrobiologyOpen. [2019] 8:845. [CrossRef]

- Lee NH, You S, Taghizadeh A, Taghizadeh M, Kim HS. Cell Membrane-Cloaked Nanotherapeutics for Targeted Drug Delivery. Int J Mol Sci. [2022] 23:2223. [CrossRef]

- Llaberia-Robledillo M, Balbuena JA, Sarabeev V, Llopis-Belenguer C. Changes in native and introduced host–parasite networks. Biological Invasions. [2022] 24:543–555. [CrossRef]

- Poulin R, Angeli Dutra D. Animal migrations and parasitism: Reciprocal effects within a unified framework. Biological Reviews. [2021] 96:1331–1348. [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [2015] 112:5649–5654. [CrossRef]

- Islam MS, Nayeem MMH, Sobur MA, Ievy S, Islam MA, Rahman S, et al. Virulence Determinants and Multidrug Resistance of Escherichia coli Isolated from Migratory Birds. Antibiotics. [2021] 10:190. [CrossRef]

- Esposito E, Scarpellini R, Celli G, Marliani G, Zaghini A, Mondo E, et al. Wild birds as potential bioindicators of environmental antimicrobial resistance: A preliminary investigation. Research in Veterinary Science. [2024] 180:105424. [CrossRef]

- Islam S, Md. P, A. T, M. R, K. AS, Md. I, et al. Migratory birds travelling to Bangladesh are potential carriers of multi-drug resistant Enterococcus spp., Salmonella spp., and Vibrio spp. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. [2021] 28:5963–5970. [CrossRef]

- Zeballos C, A. M, Gaj T. Next-Generation CRISPR Technologies and Applications. Trends Biotechnol. [2021] 39:692–705. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed NA, Gulhan T. Campylobacter in Wild Birds: Is It an Animal and Public Health Concern? Frontiers in Microbiology. [2022] 12:812591. [CrossRef]

- Nabil NM, Erfan AM, Tawakol MM, Haggag NM, Naguib MM, Samy A. Wild Birds in Live Birds Markets: Potential Reservoirs of Enzootic Avian Influenza Viruses and Antimicrobial Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Northern Egypt. Pathogens. [2020] 9:196. [CrossRef]

- Sambaza SS, Naicker N. Contribution of wastewater to antimicrobial resistance: A review article. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. [2023] 34:23–29. [CrossRef]

- Esposito MM, Turku S, Lehrfield L, Shoman A. The Impact of Human Activities on Zoonotic Infection Transmissions. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI. [2023] 13:1646. [CrossRef]

- Pereira GQ, Gomes LA, Santos IS, Alfieri AF, Weese JS, Costa MC. Fecal microbiota transplantation in puppies with canine parvovirus infection. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. [2018] 32:707–711. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).