Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

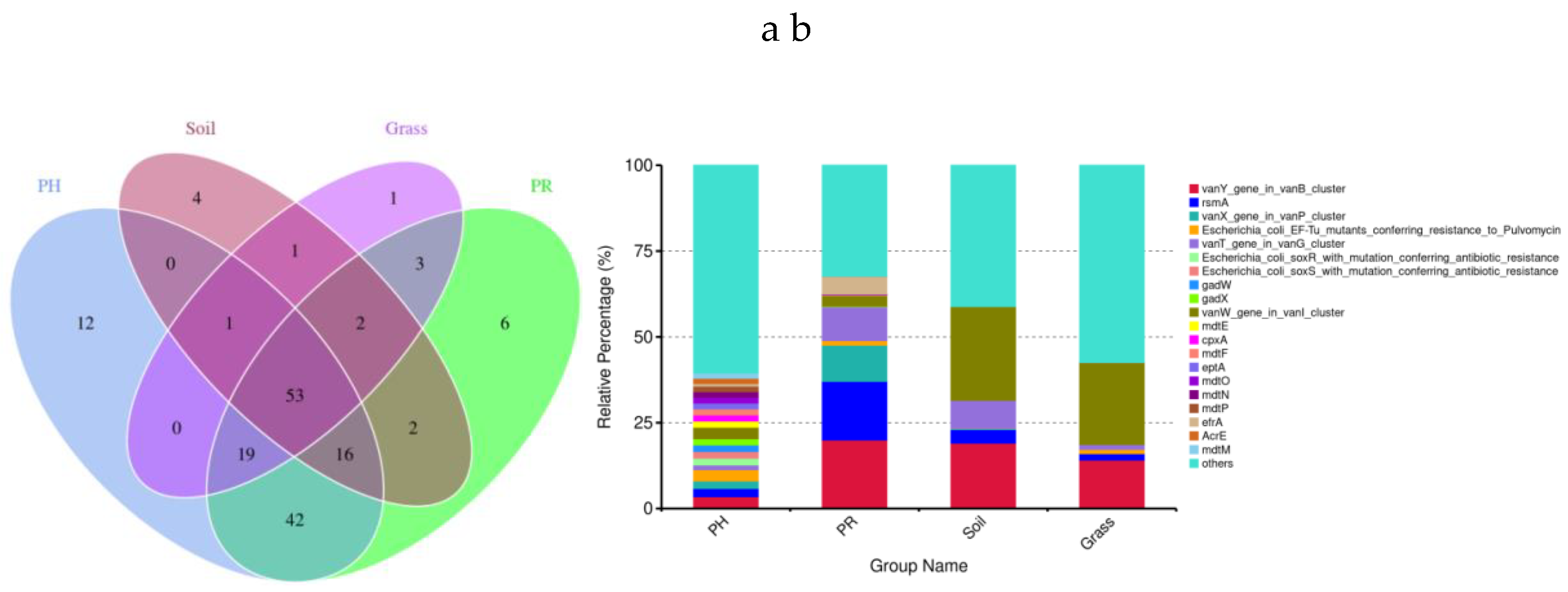

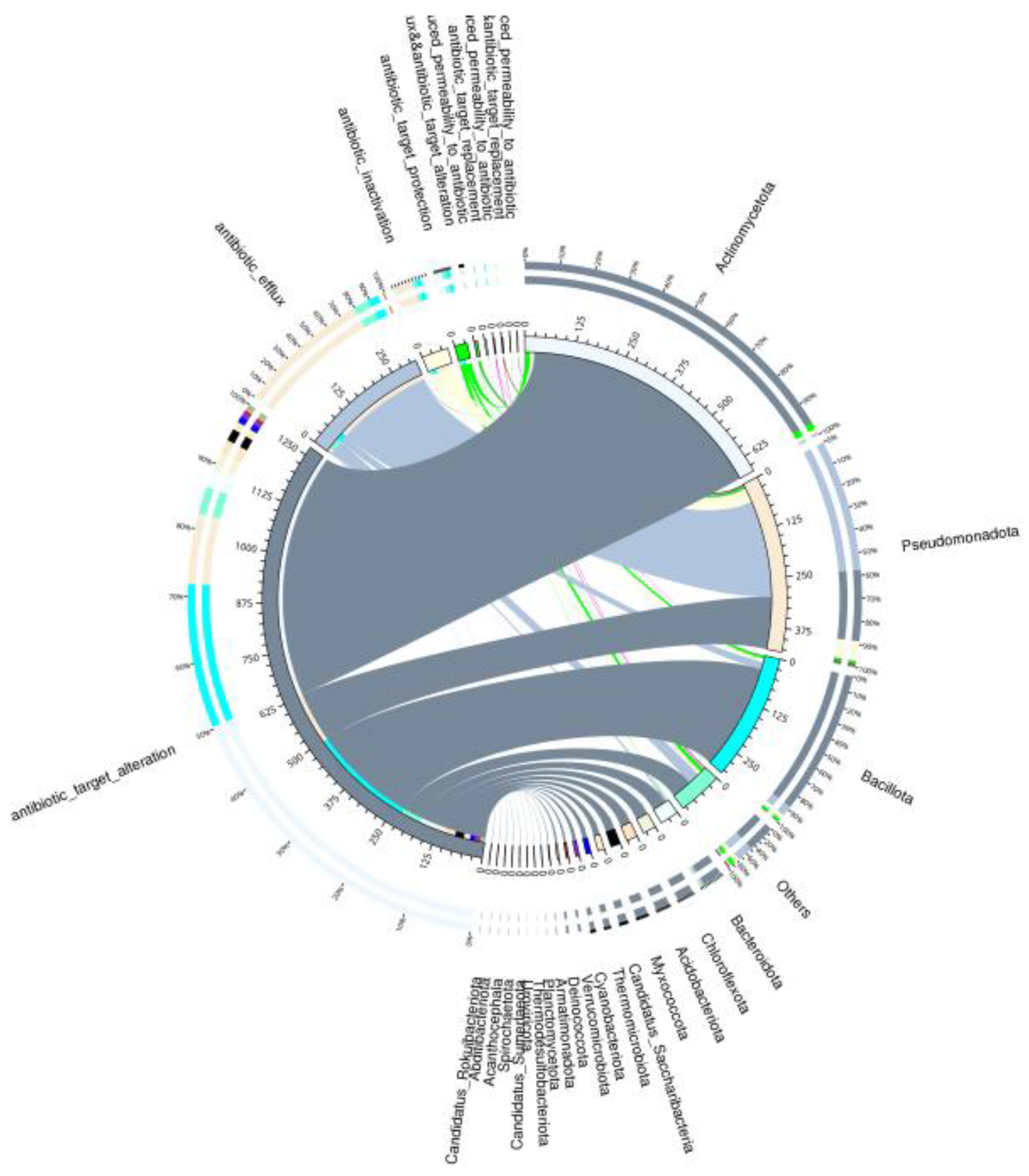

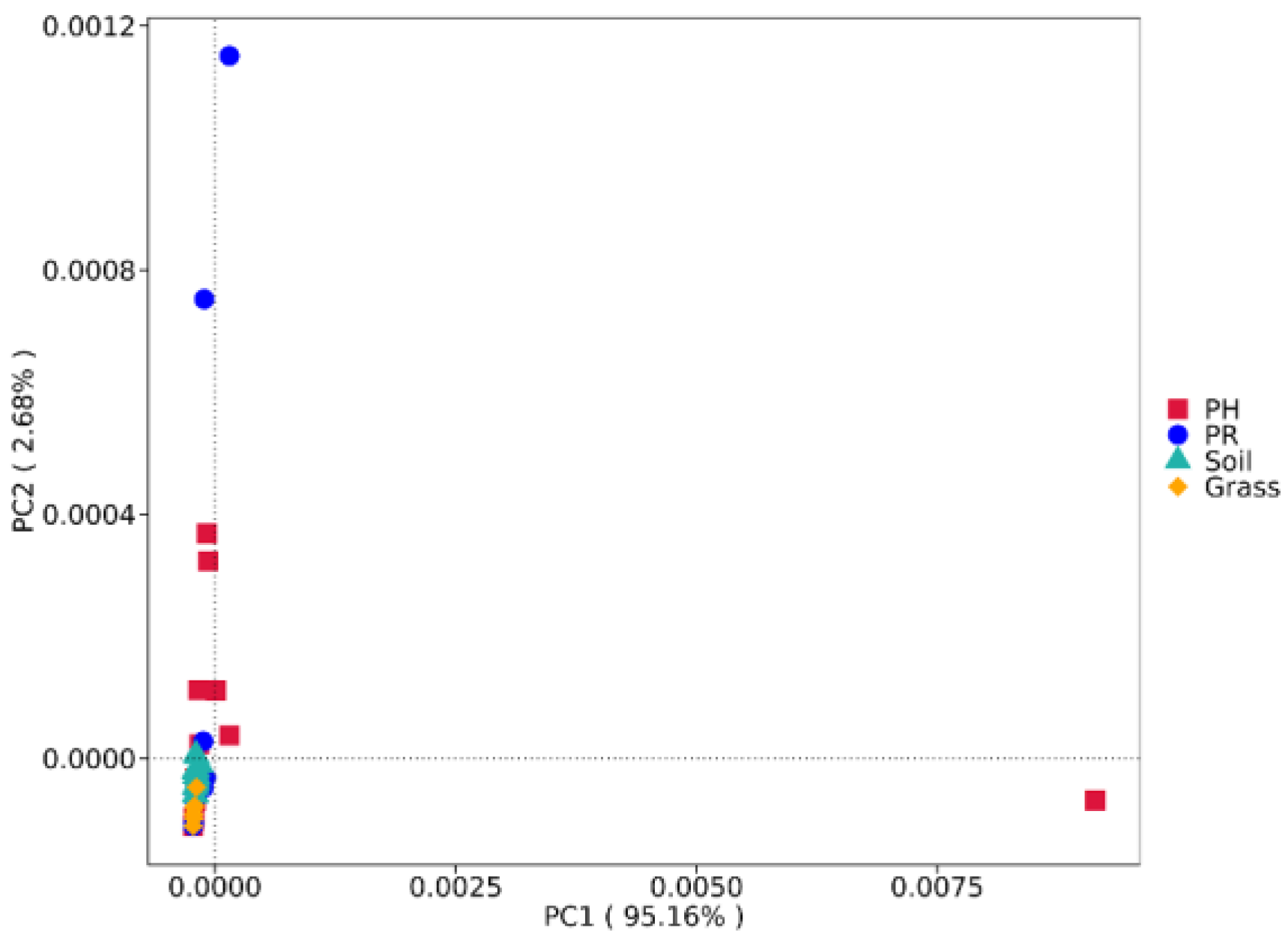

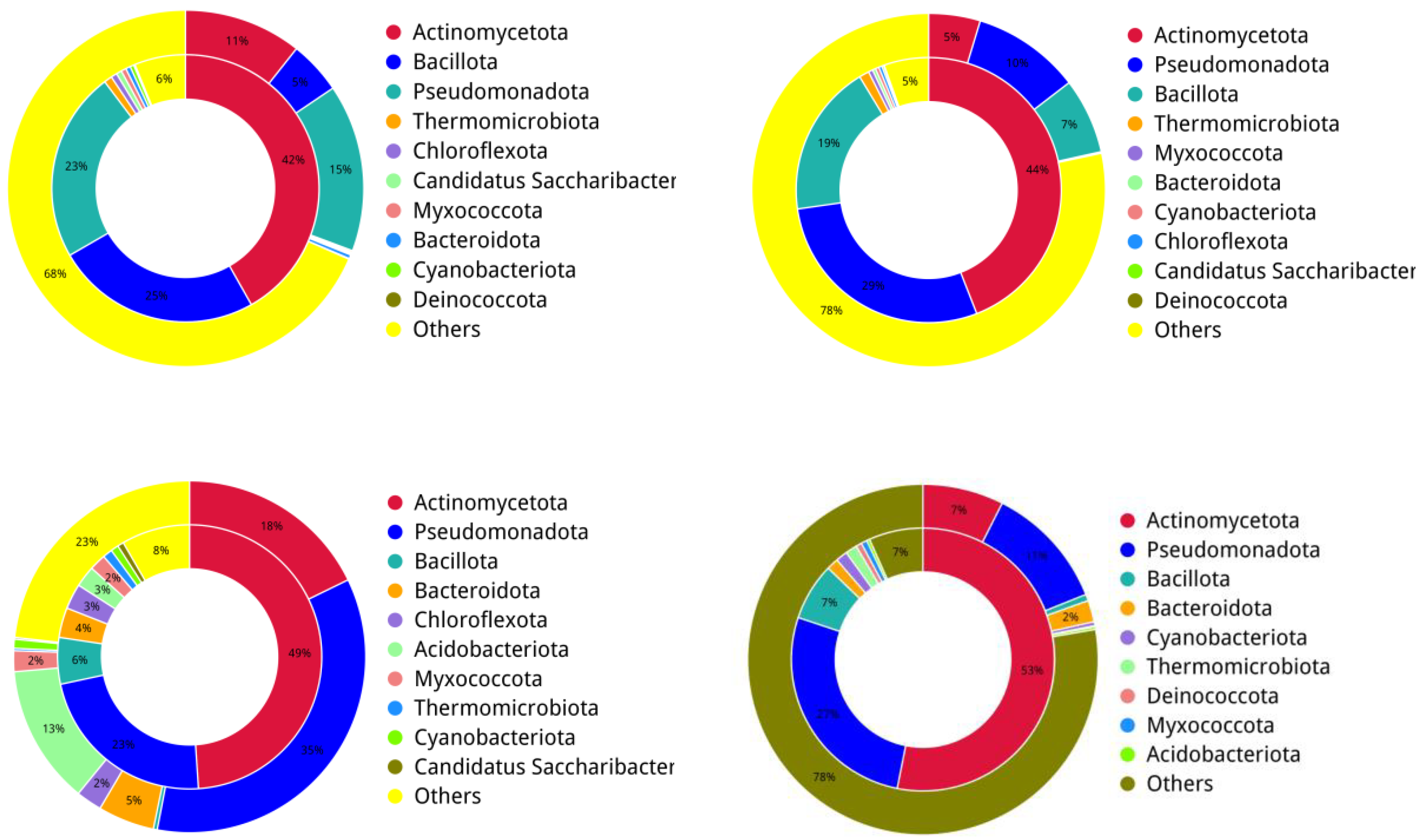

Metagenomic analysis of nonmigratory passerines (Pseudopodoces humilis and Pyrgilauda ruficollis) and their habitats on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau revealed convergent adaptations in gut microbial composition and function dominated by Bacillota and Pseudomonadota. Functional enrichment in carbohydrate metabolism and genetic information processing underpins host energy optimization in extreme high-altitude environments. Critically, these birds constitute a major reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), harbouring 162 antibiotic resistance ontologies (AROs) with nearly universal resistance to clinical antibiotic classes. The core resistome—comprising glycopeptide (van clusters), fluoroquinolone, and tetracycline resistance genes—reflects anthropogenic contamination amplified by environmental persistence. Environmental transmission pathways were unequivocally demonstrated via 53 AROs shared between avian hosts and proximal matrices (soil/grass), coupled with livestock-derived antibiotic influx through excreta, establishing the plateau as a hotspot for resistance gene flux. Strikingly, "low-abundance-high-resistance" taxa (Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, and Bacillota; ≤20% abundance but >90% ARG contribution) drive resistome plasticity, potentially facilitated by horizontal gene transfer. Our findings redefine resident passerines as sentinels of ecosystem health and bridges for cross-boundary antimicrobial resistance (AMR) spread. Mitigating global AMR thus necessitates interdisciplinary strategies targeting environmental reservoirs (e.g., regulating livestock antibiotic use) and monitoring avian-mediated gene flow.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Sequence Analyses and Metagenome Assembly

2.4. Gene Prediction and Construction of the Nonredundant Gene Set

2.5. Gene Taxonomic Prediction

2.6. Functional Gene Annotation

3. Results

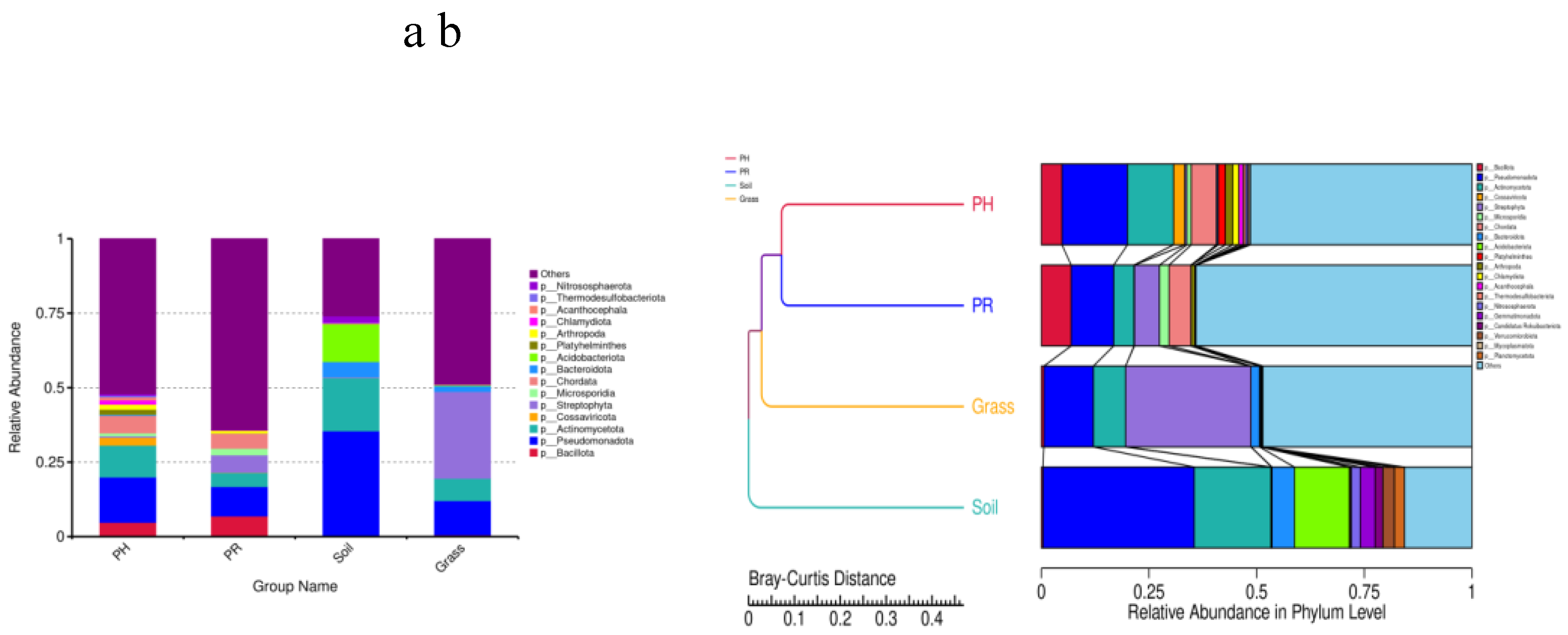

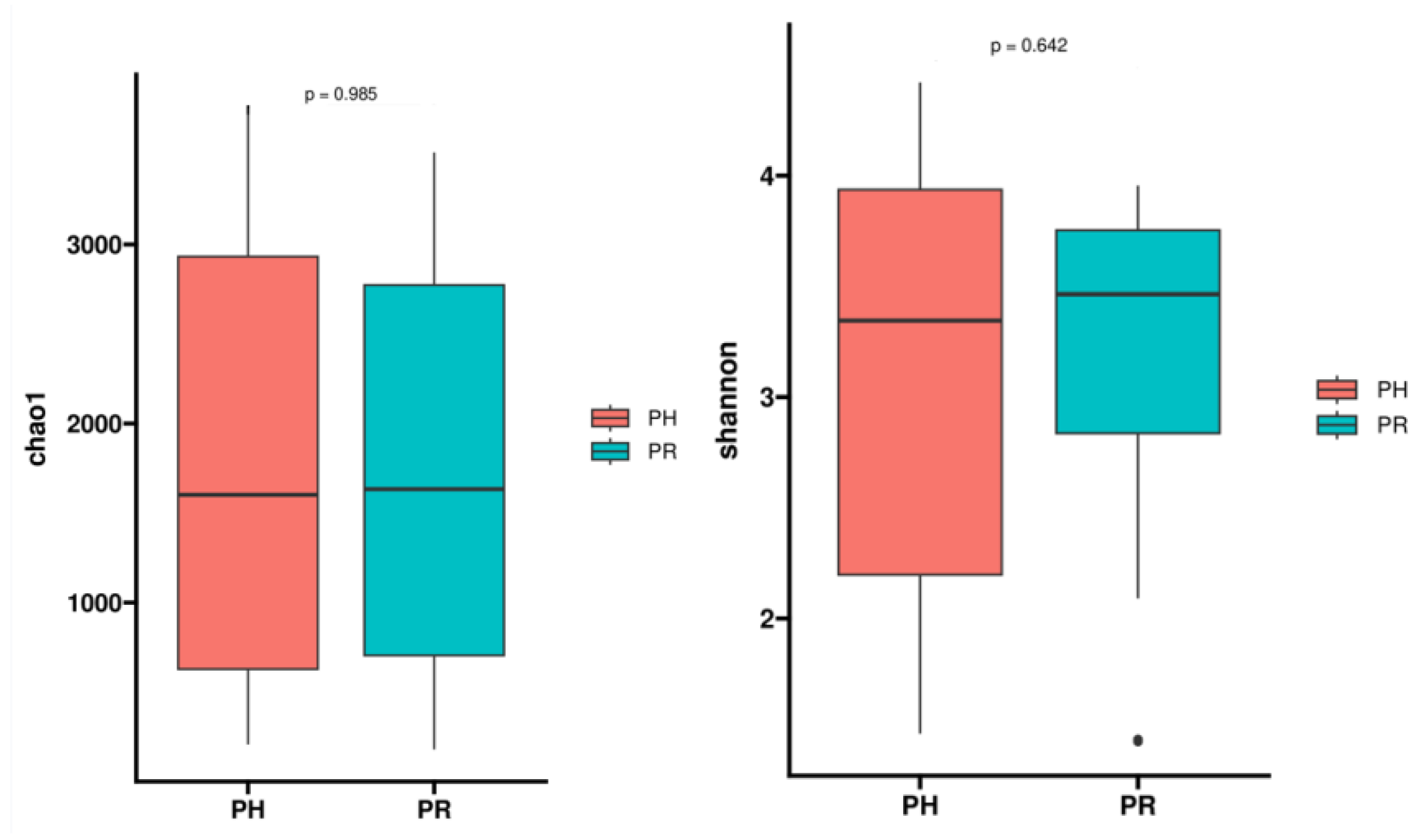

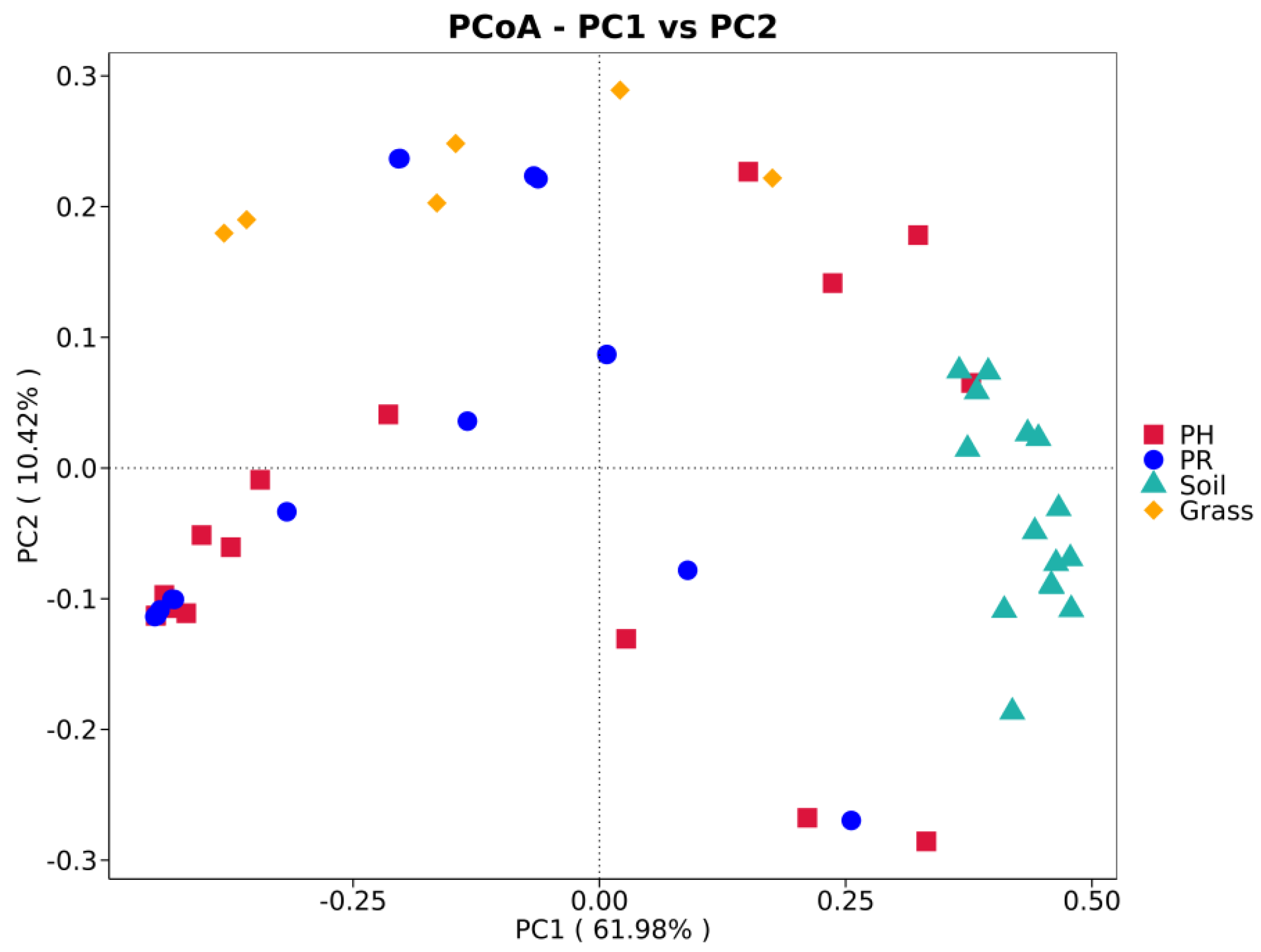

3.1. Bacterial Community Profile

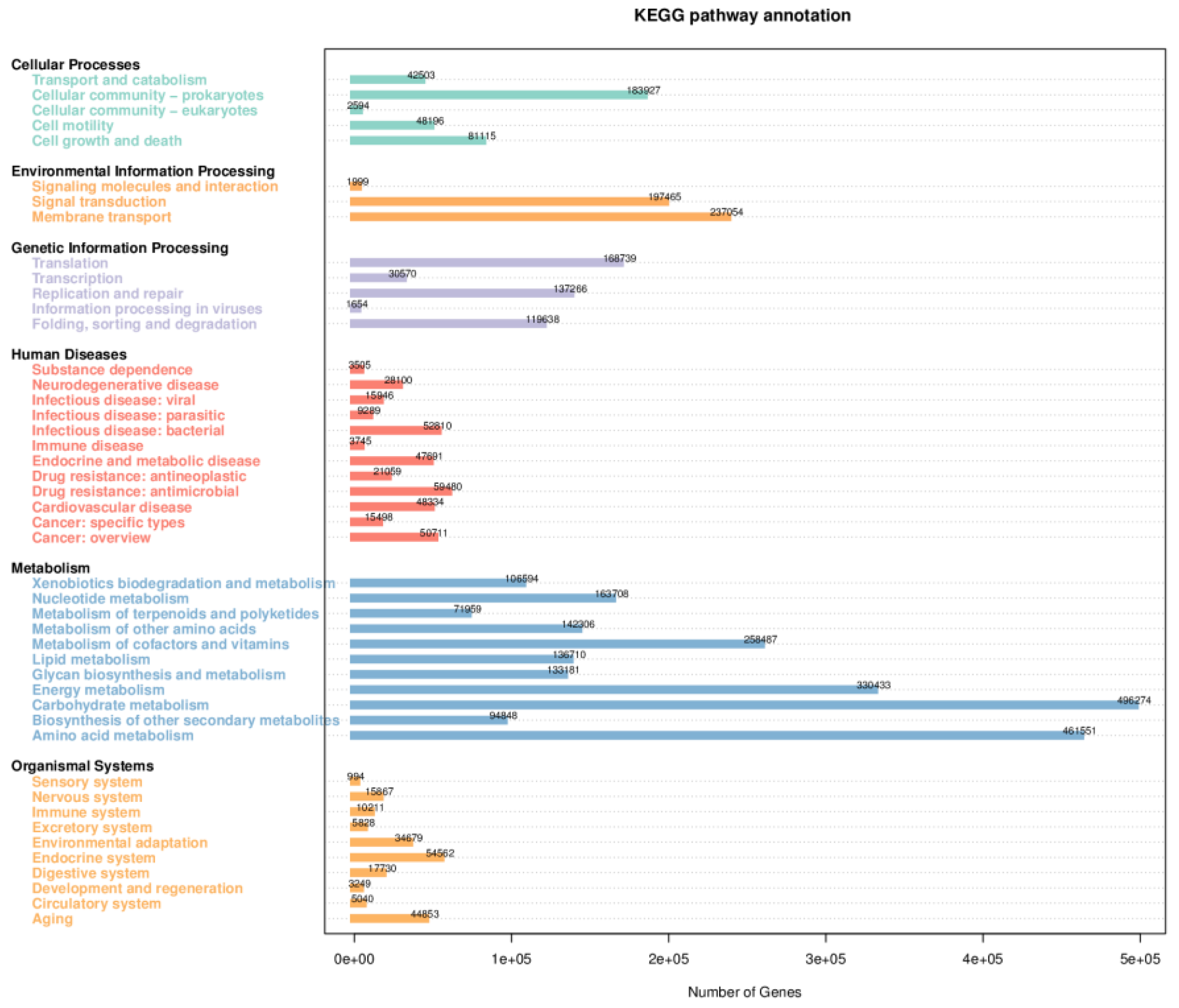

3.2. Functional Profiling of the Gut Metagenome

3.3. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest statement

References

- Li JT, Gao YD, Xie L, et al. Comparative genomic investigation of high-elevation adaptation in ectothermic snakes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(33):8406-8411. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Priscu JC, Yao T, et al. Bacterial responses to environmental change on the Tibetan Plateau over the past half century. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(6):1930-1941. [CrossRef]

- Tang B, Wang Y, Dong Y, et al. The Catalog of Microbial Genes and Metagenome-Assembled Genomes from the Gut Microbiomes of Five Typical Crow Species on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Microorganisms. 2024;12(10):2033. Published 2024 Oct 8. [CrossRef]

- Fragiadakis GK, Smits SA, Sonnenburg ED et al. (2019).Links between environment, diet, and the huntergatherer microbiome. Gut Microbes 10, 216–27.

- Orkin JD, Campos FA, Myers MS et al. (2019). Seasonality of the gut microbiota of free-ranging white-faced capuchins in a tropical dry forest. The ISME Journal 13, 183–96.

- Kešnerová L, Emery O, Troilo M et al. (2020). Gut microbiota structure differs between honeybees in winterand summer. The ISME Journal 14, 801–14.

- Fan C, Zhang L, Jia S, et al. Seasonal variations in the composition and functional profiles of gut microbiota reflect dietary changes in plateau pikas. Integr Zool. 2022;17(3):379-395. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Ma S, Chang L, et al. Gut microbiota adaptation to high altitude in indigenous animals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516(1):120-126. [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(18):5649-5654. [CrossRef]

- Knapp CW, Dolfing J, Ehlert PA, Graham DW. Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(2):580-587. [CrossRef]

- Sommer MOA, Dantas G, Church GM. Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science. 2009;325(5944):1128-1131. [CrossRef]

- Smillie CS, Smith MB, Friedman J, Cordero OX, David LA, Alm EJ. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature. 2011;480:241–4.

- Allen HK, Donato J, Wang HH, Cloud-Hansen KA, Davies J, Handelsman J. Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(4):251-259. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Yang X, Qin J, et al. Metagenome-wide analysis of antibiotic resistance genes in a large cohort of human gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2151. [CrossRef]

- Hird SM. Evolutionary Biology Needs Wild Microbiomes [J]. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:725. [CrossRef]

- García-Amado MA, Shin H, Sanz V, et al. Comparison of gizzard and intestinal microbiota of wild neotropical birds [J/OL]. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194857. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Dong X, Sun R, et al. Migratory birds-one major source of environmental antibiotic resistance around Qinghai Lake, China. Sci Total Environ. 2020;739:139758. [CrossRef]

- Yang SJ, Yin ZH, Ma XM, Lei FM. Phylogeography of ground tit (Pseudopodoces humilis) based on mtDNA: evidence of past fragmentation on the Tibetan Plateau. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;41(2):257-265. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Halimubieke N, Fang B, et al. Gut microbiome in two high-altitude bird populations showed heterogeneity in sex and life stage. FEMS Microbes. 2024;5:xtae020. Published 2024 Jul 4. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Hao Y, Zhang Q, et al. Coping with extremes: Alternations in diet, gut microbiota, and hepatic metabolic functions in a highland passerine. Sci Total Environ. 2023;905:167079. [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K.D. Diversity and function of the avian gut microbiota. J Comp Physiol B 182, 591–602 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Turaev D, Rattei T. High definition for systems biology of microbial communities: metagenomics gets genome-centric and strain-resolved. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;39:174-181. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson FH, Fåk F, Nookaew I, et al. Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1245. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498(7452):99-103. [CrossRef]

- Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife. 2013;2:e01202. Published 2013 Nov 5. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen HB, Almeida M, Juncker AS, et al. Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):822-828. [CrossRef]

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59-65. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Liu CM, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam TW. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(10):1674-1676. [CrossRef]

- Mende DR, Waller AS, Sunagawa S, et al. Assessment of metagenomic assembly using simulated next generation sequencing data [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e114063]. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31386. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Jia H, Cai X, et al. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):834-841. [CrossRef]

- Oh J, Byrd AL, Deming C, et al. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature. 2014;514(7520):59-64. [CrossRef]

- Qin N, Yang F, Li A, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature. 2014;513(7516):59-64. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(12):e132. [CrossRef]

- Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10(11):766. Published 2014 Nov 28. [CrossRef]

- Sunagawa S, Coelho LP, Chaffron S, et al. Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science. 2015;348(6237):1261359. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658-1659. [CrossRef]

- Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3150-3152. [CrossRef]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):59-60. [CrossRef]

- Huson DH, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh HJ, Weber N, Schuster SC. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 2011;21(9):1552-1560. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Hattori M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D354-D357. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353-D361. [CrossRef]

- Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6528. Published 2015 Mar 11. [CrossRef]

- Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55-60. [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(6):852. [CrossRef]

- Martínez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F. What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(2):116-123. [CrossRef]

- Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D566-D573. [CrossRef]

- McArthur AG, Waglechner N, Nizam F, et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3348-3357. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Ju F, Cai L, Zhang T. Profile and fate of bacterial pathogens in sewage treatment plants revealed by high-throughput metagenomic approach.Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:10492–502. [CrossRef]

- Kropáčková L, Pechmanová H, Vinkler M, Svobodová J, Velová H, Těšičký M, et al. Variation between the oral and faecal microbiota in a free-living passerine bird, the great tit (Parus major) PLoS ONE. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lewis WB, Moore FR, Wang S. Characterization of the gut microbiota of migratory passerines during stopover along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. J Avian Biol. 2016;47:659–668. [CrossRef]

- Joakim RL, Irham M, Haryoko T, et al. Geography and elevation as drivers of cloacal microbiome assemblages of a passerine bird distributed across Sulawesi, Indonesia. Anim Microbiome. 2023;5(1):4. Published 2023 Jan 16. [CrossRef]

- Maritan E, Quagliariello A, Frago E, Patarnello T, Martino ME. The role of animal hosts in shaping gut microbiome variation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2024;379(1901):20230071. [CrossRef]

- Moeller AH, Caro-Quintero A, Mjungu D, et al. Cospeciation of gut microbiota with hominids. Science. 2016;353(6297):380-382. [CrossRef]

- Berry D. The emerging view of Firmicutes as key fibre degraders in the human gut [published correction appears in Environ Microbiol. 2016 Dec;18(12):5305. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13590.]. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(7):2081-2083. [CrossRef]

- Tap J, Mondot S, Levenez F, et al. Towards the human intestinal microbiota phylogenetic core. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11(10):2574-2584. [CrossRef]

- Flint HJ, Bayer EA, Rincon MT, Lamed R, White BA. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:121–31.

- Fujii A, Kawada-Matsuo M, Nguyen-Tra Le M, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility and genome analysis of Enterococcus species isolated from inpatients in one hospital with no apparent outbreak of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus in Japan. Microbiol Immunol. 2024;68(8):254-266. [CrossRef]

- Isnansetyo A, Kamei Y. Bioactive substances produced by marine isolates of Pseudomonas. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;36(10):1239-1248. [CrossRef]

- Mikaelyan A, Dietrich C, Köhler T, Poulsen M, Sillam-Dussès D, Brune A. Diet is the primary determinant of bacterial community structure in the guts of higher termites. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(20):5284-5295. [CrossRef]

- Barns, S. M., Takala, S. L., and Kuske, C. R. (1999) Wide distri bution and diversity of members of the bacterial kingdom Acidobacteria in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microb. 65, 1731–1737.

- Cole, J. R., Chai, B., Farris, R. J., Wang, Q., Kulam, S. A., McGarrell, D. M., Garrity, G. M., and Tiedje, J. M. (2005) The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D294–D296.

- N. Fierer, & R.B. Jackson, The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (3) 626-631. (2006).). [CrossRef]

- Lyu J, Yang L, Zhang L, Ye B, Wang L. Antibiotics in soil and water in China-a systematic review and source analysis. Environ Pollut. 2020;266(Pt 1):115147. [CrossRef]

- Phan TG, Vo NP, Boros Á, et al. The viruses of wild pigeon droppings. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72787. Published 2013 Sep 4. [CrossRef]

- Wille M, Shi M, Hurt AC, Klaassen M, Holmes EC. RNA virome abundance and diversity is associated with host age in a bird species. Virology. 2021;561:98–106. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Martinez LA, Loza-Rubio E, Mosqueda J, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Garcia-Espinosa G. Fecal virome composition of migratory wild duck species. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0206970. [CrossRef]

- Li L.G., Huang Q., Yin X., Zhang T. Source tracking of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment—Challenges, progress, and prospects. Water. Res. 2020;185:116127. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I. Withdrawal of growth-promoting antibiotics in Europe and its effects in relation to human health. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30, 101–107 (2007).

- Manson JM, Keis S, Smith JM, Cook GM. A clonal lineage of VanA-type Enterococcus faecalis predominates in vancomycin-resistant Enterococci isolated in New Zealand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(1):204-210. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I. et al. Does the use of antibiotics in food animals pose a risk to human health? A critical review of published data. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53, 28–52 (2004).

- D'Costa, V. M. et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477, 457–461 (2011).

- Wright, G. D. & Poinar, H. Antibiotic resistance is ancient: implications for drug discovery. Trends Microbiol. 20, 157–159 (2012).

- Nesme, J. et al. Large-Scale Metagenomic-Based Study of Antibiotic Resistance in the Environment. Curr. Biol. 24, 1096–1100 (2014).

- Bhatt S, Chatterjee S. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: Occurrence, mode of action, resistance, environmental detection, and remediation - A comprehensive review. Environ Pollut. 2022;315:120440. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Cui Q, Hou Y, et al. Metagenomic Insights into the Diverse Antibiotic Resistome of Non-Migratory Corvidae Species on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Vet Sci. 2025;12(4):297. Published 2025 Mar 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhai J, Wang Y, Tang B, et al. A comparison of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in wild and captive Himalayan vultures. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17710. Published 2024 Jul 9. [CrossRef]

- Zubair et al. (2023).Zubair M, Li Z, Zhu R, Wang J, Liu X, Liu X. The antibiotics degradation and its mechanisms during the livestock manure anaerobic digestion. Molecules. 2023;28:4090. [CrossRef]

- Zhang QQ, Ying GG, Pan CG, Liu YS, Zhao JL. A comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modelling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:6772–6782. [CrossRef]

- Bonnedahl J, Jarhult JD. Antibiotic resistance in wild birds. Upsala J Med Sci. 2014;119:113–116. [CrossRef]

- Munk P., Knudsen B.E., Lukjancenko O., Duarte A.S.R., Van Gompel L., Luiken R.E.C., Smit L.A.M., Schmitt H., Garcia A.D., Hansen R.B., et al. Abundance and diversity of the faecal resistome in slaughter pigs and broilers in nine European countries. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:898–908. [CrossRef]

- Larsson DGJ, Flach CF. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(5):257-269. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).