Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.3.2. Regression Analysis

2.3.3. Assessing Co-Resistance Patterns

2.3.3.1. Clustering Analysis

2.3.3.2. Network Analysis

3. Results

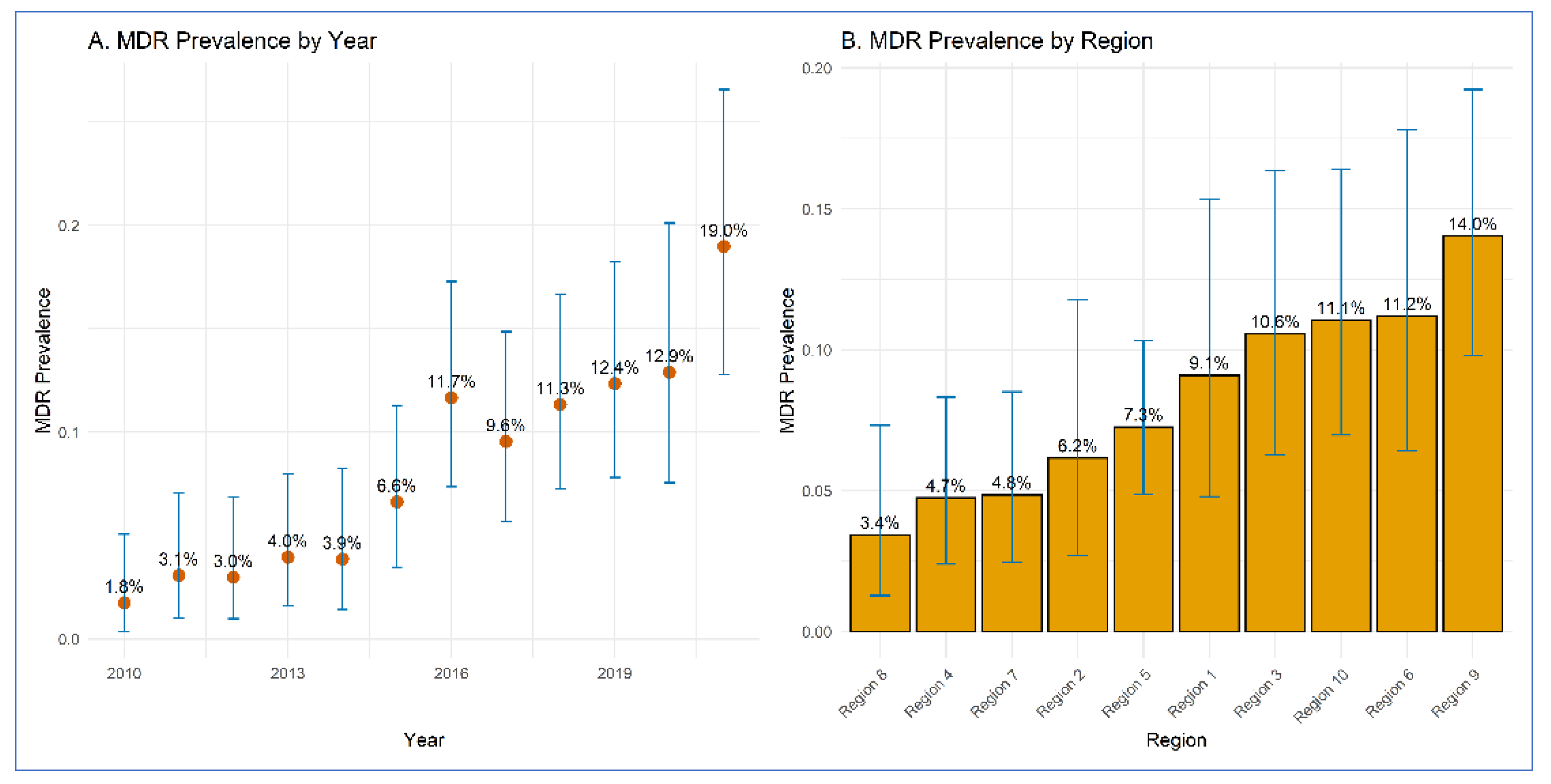

3.1. Prevalence of MDR E. coli O157 by Year and Region

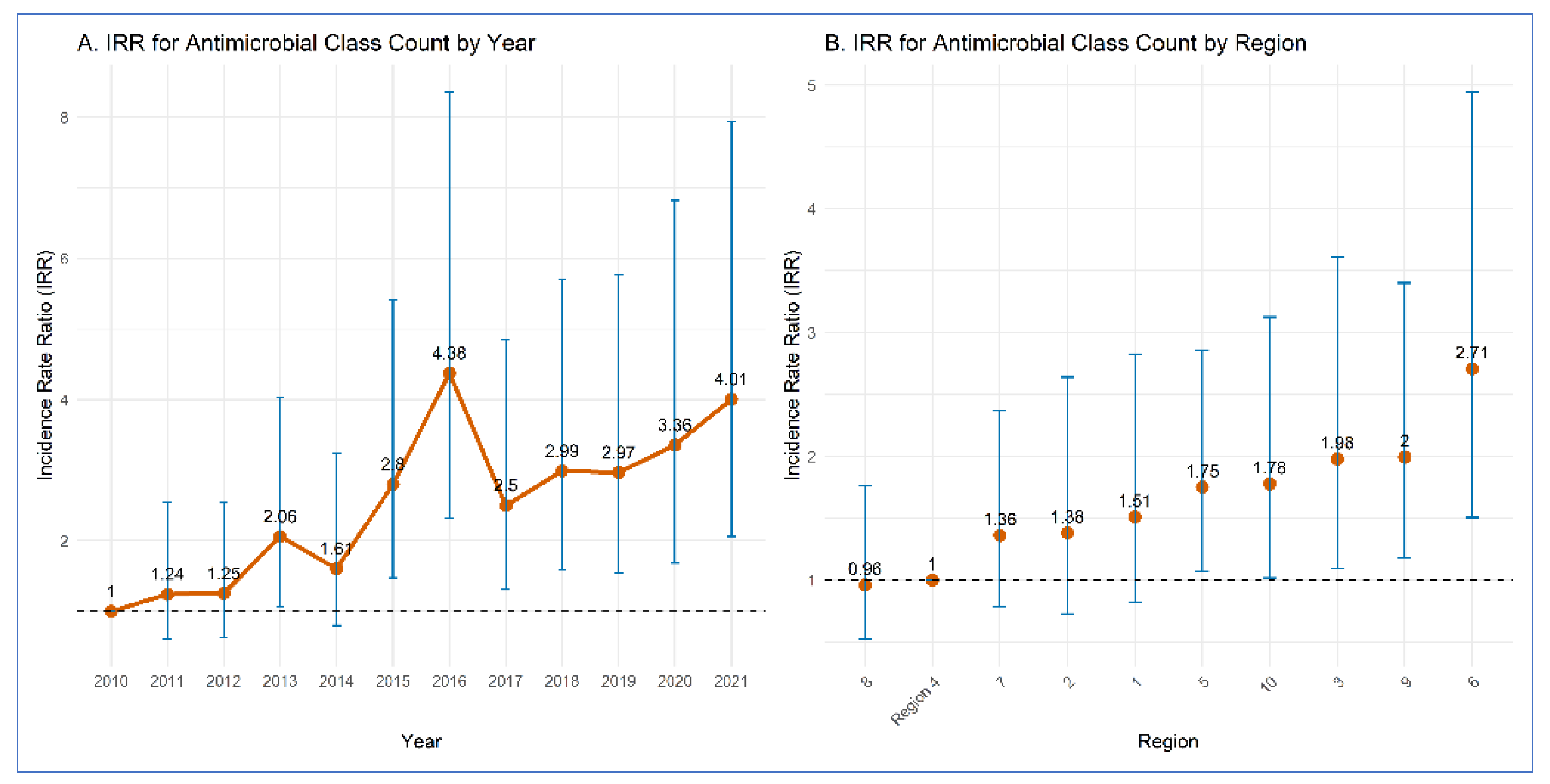

3.2. Regression Analysis

2.3.3. Assessing Co-Resistance Patterns

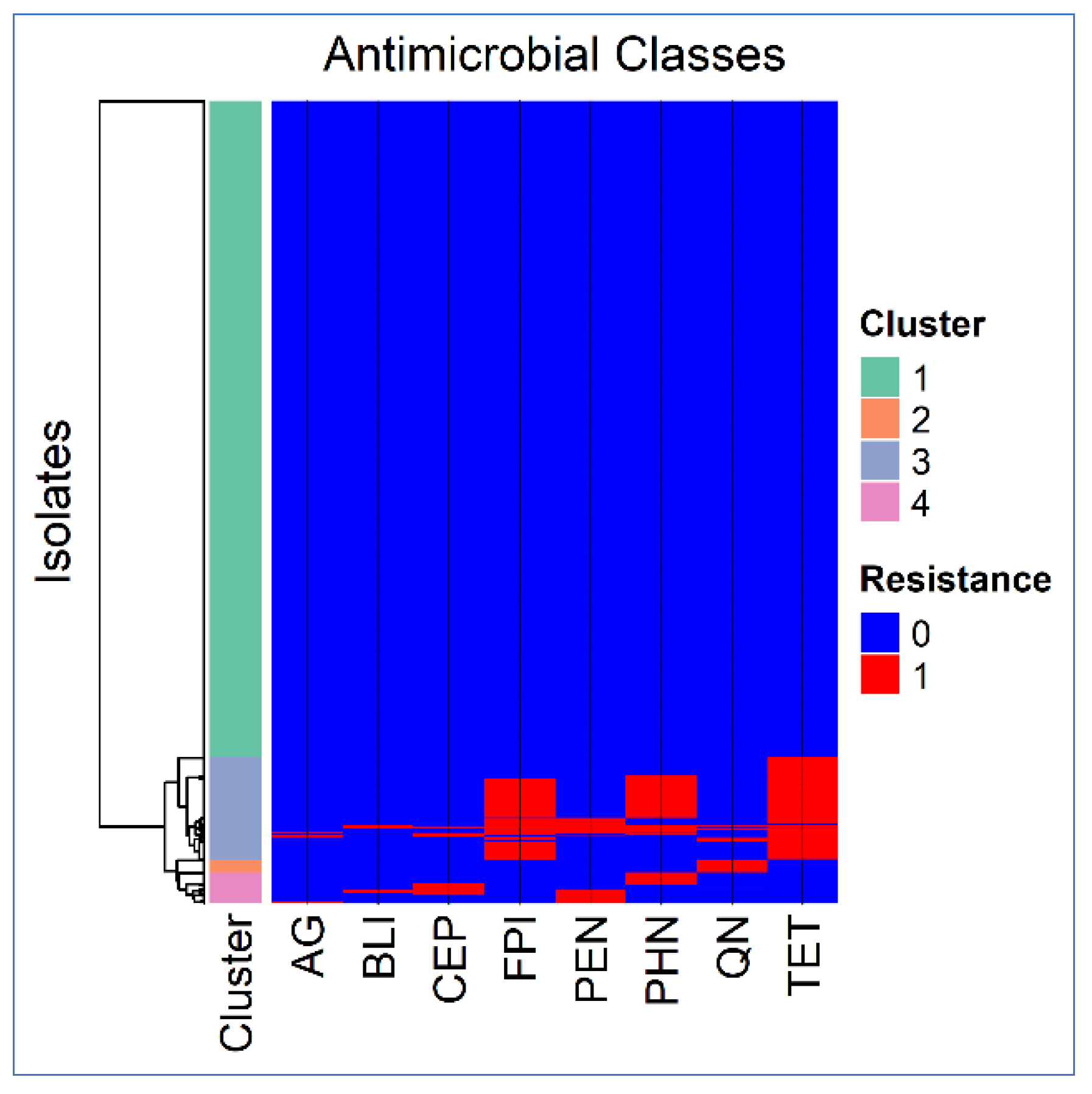

2.3.3.1. Cluster Analysis

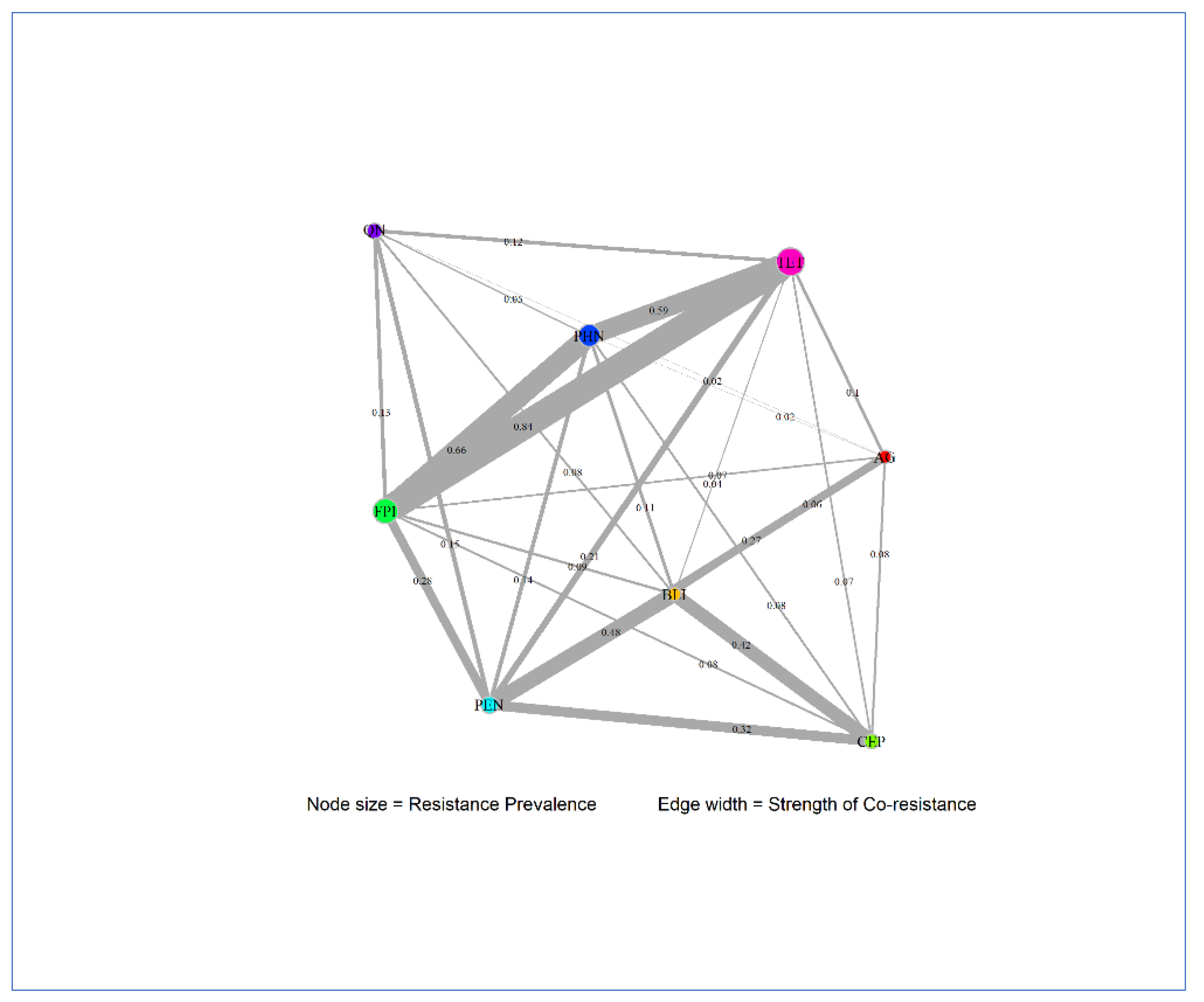

2.3.3.2. Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majowicz, S.E.; Scallan, E.; Jones-Bitton, A.; et al. Global Incidence of Human Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infections and Deaths: A Systematic Review and Knowledge Synthesis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.; Varga, C.; Cooke, M.; Majowicz, S.E. Incidence, Demographic, and Seasonal Risk Factors of Infections Caused by Five Major Enteric Pathogens, Ontario, Canada, 2010-2017. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2022, 19, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Cointe, A.; Mariani Kurkdjian, P.; Rafat, C.; Hertig, A. Shiga Toxin-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Technical Information | E. coli Infection. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/php/technical-info/index.html.

- Dornbach, C.W.; Hales, K.E.; Gubbels, E.R.; Wells, J.E.; Hoffman, A.A.; Hanratty, A.N.; Line, D.J.; Smock, T.M.; Manahan, J.L.; McDaniel, Z.S.; Kohl, K.B.; Burdick Sanchez, N.C.; Carroll, J.A.; Rusche, W.C.; Smith, Z.K.; Broadway, P.R. Longitudinal Assessment of Prevalence and Incidence of Salmonella and Escherichia coli O157 Resistance to Antimicrobials in Feedlot Cattle Sourced and Finished in Two Different Regions of the United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughini-Gras, L.; van Pelt, W.; van der Voort, M.; Heck, M.; Friesema, I.; Franz, E. Attribution of Human Infections with Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli (STEC) to Livestock Sources and Identification of Source-Specific Risk Factors, The Netherlands (2010-2014). Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, e8–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devleesschauwer, B.; Pires, S.M.; Young, I.; Gill, A.; Majowicz, S.E.; Study Team. Associating Sporadic, Foodborne Illness Caused by Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli with Specific Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.J.; Scheftel, J.M.; Smith, K.E. Raw Milk Consumption among Patients with Non-Outbreak-Related Enteric Infections, Minnesota, USA, 2001-2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kintz, E.; Byrne, L.; Jenkins, C.; McCarthy, N.; Vivancos, R.; Hunter, P. Outbreaks of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Linked to Sprouted Seeds, Salad, and Leafy Greens: A Systematic Review. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, C.; John, P.; Cooke, M.; Majowicz, S.E. Area-Level Clustering of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infections and Their Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors in Ontario, Canada: An Ecological Study. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2021, 18, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.; Varga, C.; Cooke, M.; Majowicz, S.E. Temporal, Spatial and Space-Time Distribution of Infections Caused by Five Major Enteric Pathogens, Ontario, Canada, 2010-2017. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodwell, E.V.; Simpson, A.; Chan, Y.W.; Godbole, G.; McCarthy, N.D.; Jenkins, C. The Epidemiology of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O26:H11 (Clonal Complex 29) in England, 2014–2021. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Shiga Toxin-Induced Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome and the Role of Antibiotics: A Global Overview. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Thaker, H.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; Dong, M. Diagnosis and Treatment for Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mukherjee, S.; Blankenship, H.M.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Mosci, R.E.; Rudrik, J.T.; Manning, S.D. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles and Frequency of Resistance Genes in Clinical Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates from Michigan over a 14-Year Period. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0118921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, D.R.; Do Nascimento, V.; Olonade, I.; Swift, C.; Nair, S.; Jenkins, C. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistant Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli O157:H7 in England, 2016–2020. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karp, B.E.; Tate, H.; Plumblee, J.R.; Dessai, U.; Whichard, J.M.; Thacker, E.L.; Hale, K.R.; Wilson, W.; Friedman, C.R.; Griffin, P.M.; McDermott, P.F. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: Two Decades of Advancing Public Health Through Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2017, 14, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/narms/about/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). BEAM (Bacteria, Enterics, Ameba, and Mycotics) Dashboard. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/BEAM-dashboard.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC’s Role in NARMS. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/narms/about/cdc-role.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Regional Offices. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/iea/regional-offices/index.html.

- CDC NARMS. Antibiotics Tested by NARMS. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/narms/about/antibiotics-tested.html#.

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; Paterson, D.L.; Rice, L.B.; Stelling, J.; Struelens, M.J.; Vatopoulos, A.; Weber, J.T.; Monnet, D.L. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, L.P.; Souza, R.F.; Belfiore, P.; Corrêa, H.L.; Haddad, M.F.C. Count Data Regression Analysis: Concepts, Overdispersion Detection, Zero-Inflation Identification, and Applications with R. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 2019, 26. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/13/.

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csárdi, G.; Nepusz, T.; Traag, V.; Horvát, S.; Zanini, F.; Noom, D.; Müller, K. igraph: Network Analysis and Visualization in R. R package version 2.1.4. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=igraph. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Bal, M.; Pati, S.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Toxigenic E. coli: A Severe Threat to Global Health. Discov. Med. 2024, 1, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwono, B.; Eckmanns, T.; Kaspar, H.; Merle, R.; Zacher, B.; Kollas, C.; Weiser, A.A.; Noll, I.; Feig, M.; Tenhagen, B.A. Cluster Analysis of Resistance Combinations in Escherichia coli from Different Human and Animal Populations in Germany 2014–2017. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sodagari, H.R.; Varga, C. Evaluating Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Commensal Escherichia coli Isolated from Cecal Samples of Swine at Slaughter in the United States, 2013–2019. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sodagari, H.R.; Agrawal, I.; Yudhanto, S.; Varga, C. Longitudinal Analysis of Differences and Similarities in Antimicrobial Resistance Among Commensal Escherichia coli Isolated from Market Swine and Sows at Slaughter in the United States of America, 2013–2019. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 407, 110388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, R.A.; Kudva, I.T. Antibiotic-Resistant Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli: An Overview of Prevalence and Intervention Strategies. Zoonoses Public Health 2019, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, J.; Mir, N.A.; Dev, K.; Khan, I.A. Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistance with Special Reference to Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infections. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amézquita-López, B.A.; Soto-Beltrán, M.; Lee, B.G.; Yambao, J.C.; Quiñones, B. Isolation, Genotyping and Antimicrobial Resistance of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018, 51, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, M.; Doumith, M.; Jenkins, C.; Dallman, T.J.; Hopkins, K.L.; Elson, R.; Godbole, G.; Woodford, N. Antimicrobial Resistance in Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Serogroups O157 and O26 Isolated from Human Cases of Diarrhoeal Disease in England, 2015. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greig, D.R.; Do Nascimento, V.; Olonade, I.; Swift, C.; Nair, S.; Jenkins, C. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistant Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli O157:H7 in England, 2016–2020. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierz, L.; Cernela, N.; Hauser, E.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Stephan, R. Characteristics of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Strains Isolated during 2010–2014 from Human Infections in Switzerland. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naidoo, N.; Zishiri, O.T. Comparative Genomics Analysis and Characterization of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 Strains Reveal Virulence Genes, Resistance Genes, Prophages, and Plasmids. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dwivedi, A.; Kumar, C.B.; Kumar, A.; Soni, M.; Sahu, V.; Awasthi, A.; Rathore, G. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant E. coli of Fish Origin Reveals the Dissemination of NDM-5 in Freshwater Aquaculture Environment by the High-Risk Clone ST167 and ST361. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 49314–49326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mencía-Ares, O.; Ramos-Calvo, E.; González-Fernández, A.; Aguarón-Turrientes, Á.; Pastor-Calonge, A.I.; Miguélez-Pérez, R.; Gutiérrez-Martín, C.B.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Insights into the Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus hyicus Isolates from Spanish Swine Farms. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | MDR Isolates | Total Isolates | Proportion (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||

| 2010 | 3 | 170 | 1.80 | 0.4–5.1 |

| 2011 | 5 | 162 | 3.10 | 1.0 - 7.1 |

| 2012 | 5 | 167 | 3.00 | 1.0 - 6.8 |

| 2013 | 7 | 177 | 4.00 | 1.6 - 8.0 |

| 2014 | 6 | 155 | 3.90 | 1.4 - 8.2 |

| 2015 | 12 | 181 | 6.60 | 3.5 - 11.3 |

| 2016 | 21 | 180 | 11.70 | 7.4 - 17.3 |

| 2017 | 17 | 178 | 9.60 | 5.7 - 14.9 |

| 2018 | 22 | 194 | 11.30 | 7.2 - 16.7 |

| 2019 | 21 | 170 | 12.40 | 7.8 - 18.3 |

| 2020 | 16 | 124 | 12.90 | 7.6 - 20.1 |

| 2021 | 26 | 137 | 19.00 | 12.8 - 26.6 |

| Region | ||||

| Region 1 | 12 | 132 | 9.10 | 4.8-15.3 |

| Region 2 | 8 | 130 | 6.20 | 2.7 - 11.8 |

| Region 3 | 17 | 161 | 10.60 | 6.3 - 16.4 |

| Region 4 | 11 | 232 | 4.70 | 2.4 - 8.3 |

| Region 5 | 28 | 386 | 7.30 | 4.9 - 10.3 |

| Region 6 | 15 | 134 | 11.20 | 6.4 - 17.8 |

| Region 7 | 11 | 227 | 4.80 | 2.4 - 8.5 |

| Region 8 | 6 | 175 | 3.40 | 1.3 - 7.3 |

| Region 9 | 32 | 228 | 14.00 | 9.8 - 19.2 |

| Region 10 | 21 | 190 | 11.10 | 7.0 - 16.4 |

| Variable | IRRa | 95% CIb (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||

| 2010 (Referent) | 1 | - | - | - |

| 2011 | 1.24 | 0.61 | 2.55 | 0.550 |

| 2012 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 2.54 | 0.531 |

| 2013 | 2.06 | 1.07 | 4.03 | 0.033 |

| 2014 | 1.61 | 0.80 | 3.24 | 0.183 |

| 2015 | 2.80 | 1.47 | 5.41 | 0.002 |

| 2016 | 4.38 | 2.33 | 8.35 | <0.001 |

| 2017 | 2.50 | 1.31 | 4.85 | 0.006 |

| 2018 | 2.99 | 1.59 | 5.70 | 0.001 |

| 2019 | 2.97 | 1.55 | 5.77 | 0.001 |

| 2020 | 3.36 | 1.68 | 6.82 | 0.001 |

| 2021 | 4.01 | 2.06 | 7.94 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||

| Region 4 (Referent) | 1 | - | - | - |

| Region 1 | 1.51 | 0.82 | 2.83 | 0.195 |

| Region 10 | 1.78 | 1.02 | 3.13 | 0.044 |

| Region 2 | 1.38 | 0.73 | 2.64 | 0.326 |

| Region 3 | 1.98 | 1.10 | 3.61 | 0.022 |

| Region 5 | 1.75 | 1.07 | 2.86 | 0.025 |

| Region 6 | 2.71 | 1.50 | 4.94 | 0.001 |

| Region 7 | 1.36 | 0.78 | 2.37 | 0.272 |

| Region 8 | 0.96 | 0.52 | 1.76 | 0.896 |

| Region 9 | 2.00 | 1.17 | 3.40 | 0.011 |

| (Intercept) | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Antimicrobial class1 | Degree | Betweenness | Closeness | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.007 |

| BLI | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.009 |

| CEP | 6 | 0.0 | 0.125 | 0.0185 |

| FPI | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.0987 |

| PEN | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.0376 |

| PHN | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.0782 |

| QN | 6 | 0.0 | 0.125 | 0.0271 |

| TET | 7 | 0.1667 | 0.1429 | 0.1238 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).