Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

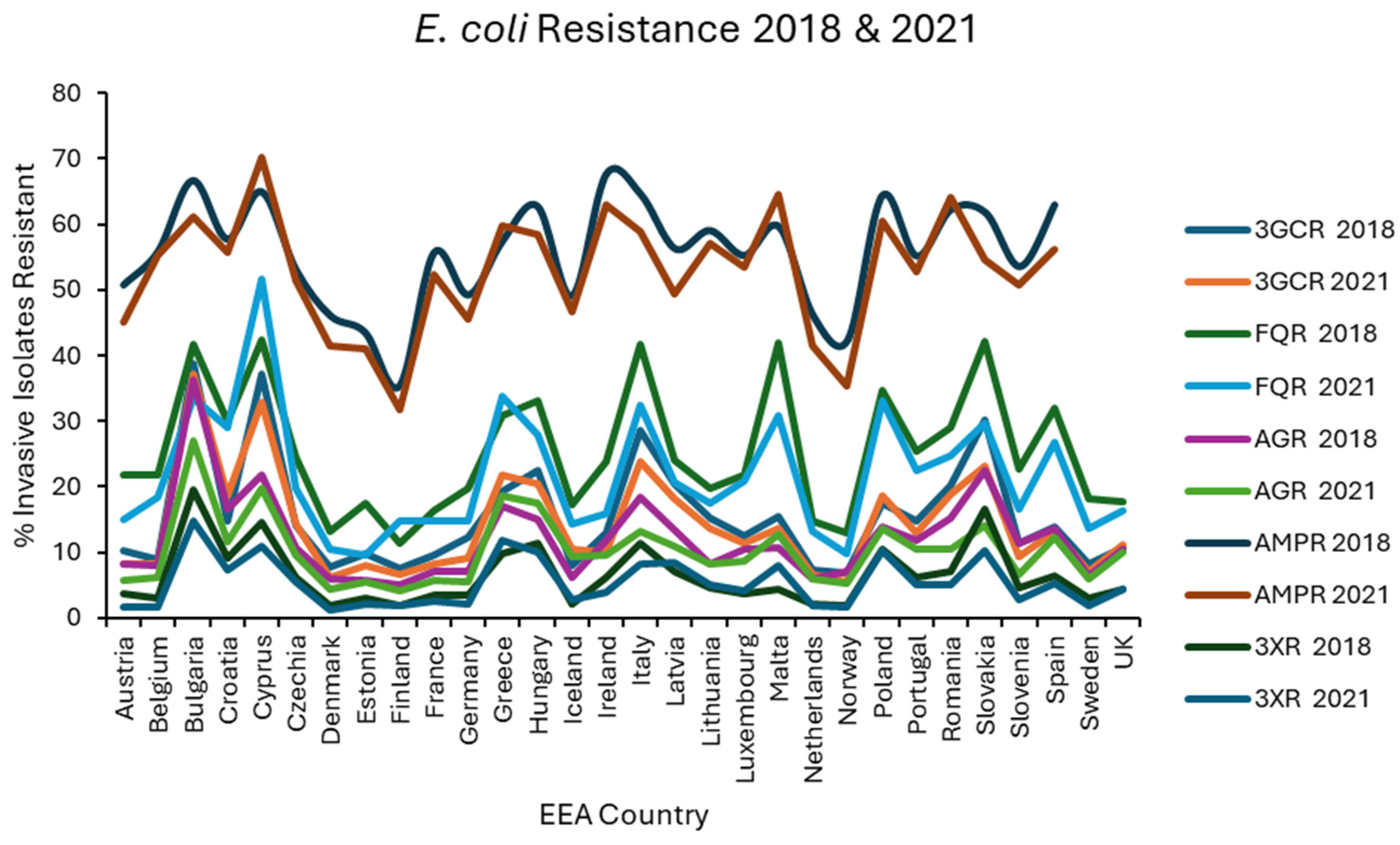

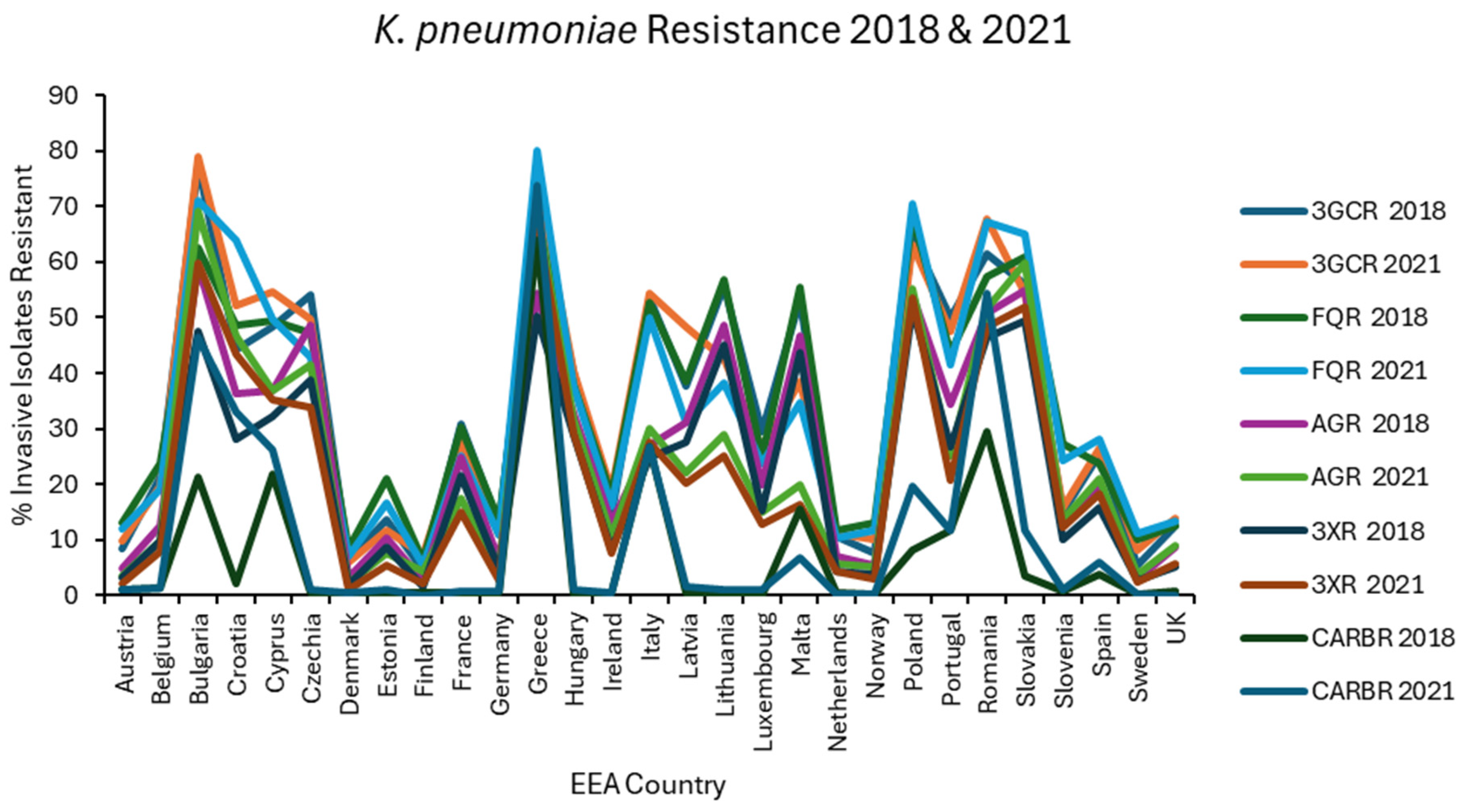

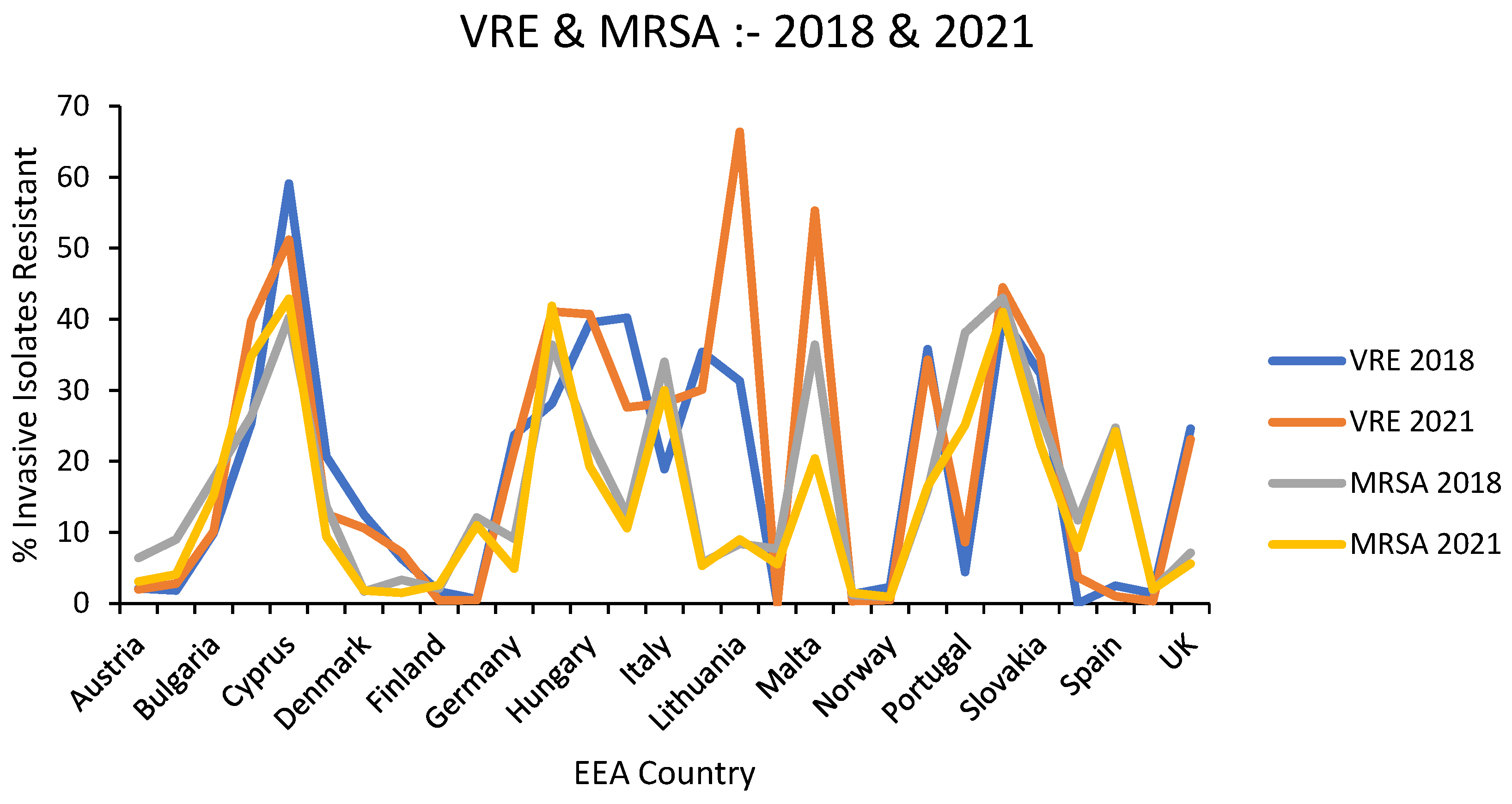

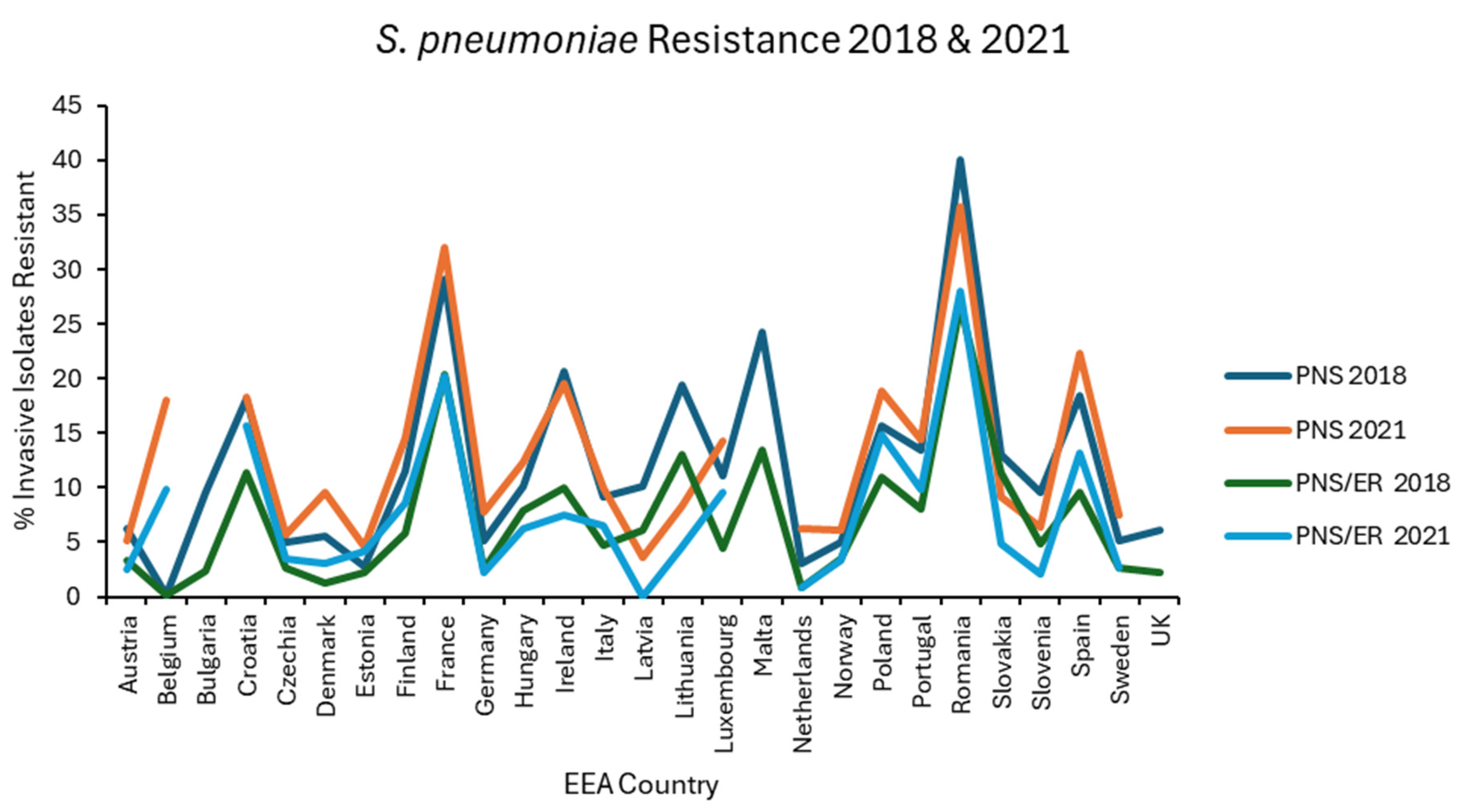

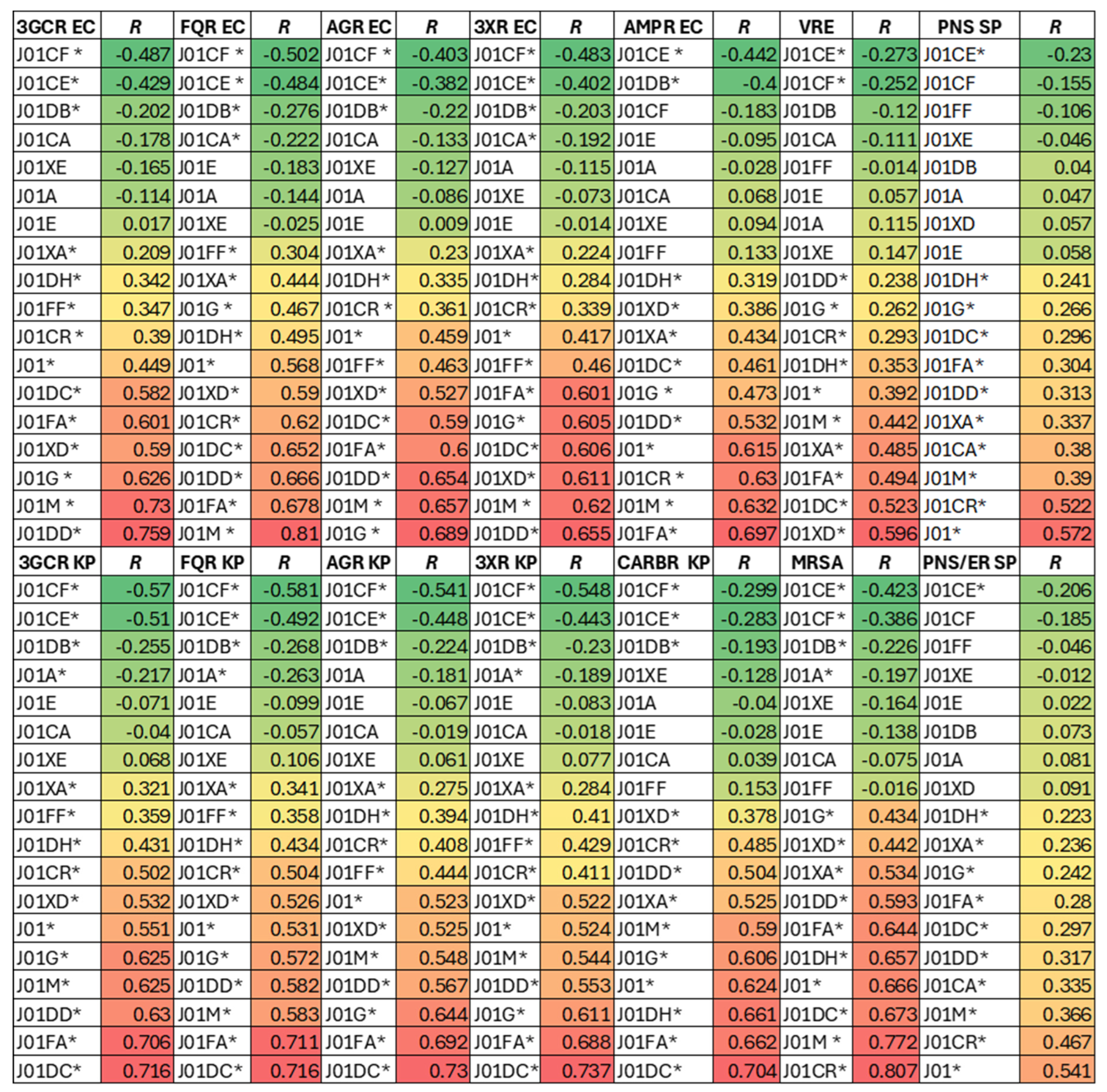

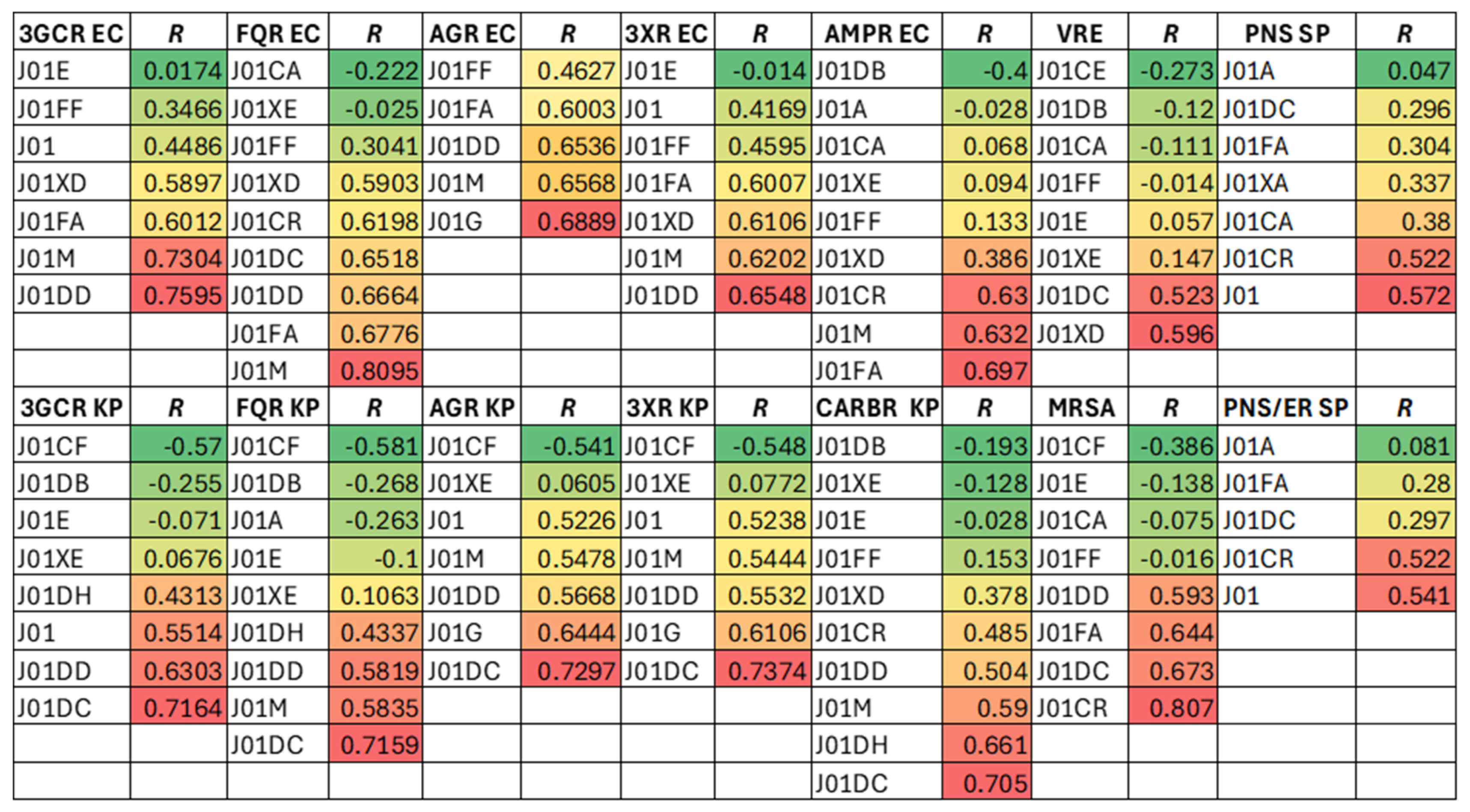

Background Antimicrobial resistance is one of the foremost global health concerns of today and could offset much of the progress accrued in healthcare over the last century. Excessive antibiotic use accelerates this problem but it is recognised that specific agents differ in their capacity to promote resistance, a concept recently promoted by the World Health Organisation in the form of its Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) schema. Which, if any, agents should be construed as having a high proclivity for selection of resistance, has been contested. The European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-NET) and European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network (ESAC-NET) curate population level data over time and throughout the European Economic Area (EEA). EARS-NET monitors resistance to antimicrobials amongst invasive isolates of sentinel pathogens whereas ESAC-NET tracks usage of systemic antimicrobials. Methods Using univariate and multivariate regression analyses, spatiotemporal associations between the use of specific antimicrobial classes and 14 key resistance phenotypes in 5 sentinel pathogens were assessed methodically for 29 EEA countries. Results Use of 2ndand 3rd generation cephalosporins, extended spectrum penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, nitroimidazoles and macrolides strongly correlated with key resistance phenotypes. Conclusions The data obtained mostly support the WHO AWaRe schema with critical caveats. They have the potential to inform antimicrobial stewardship initiatives in the EEA, highlighting obstacles and shortcomings which may be modified in future to minimise positive selection for problematic resistance.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Associations Between Overall Antibiotic USE and Resistance

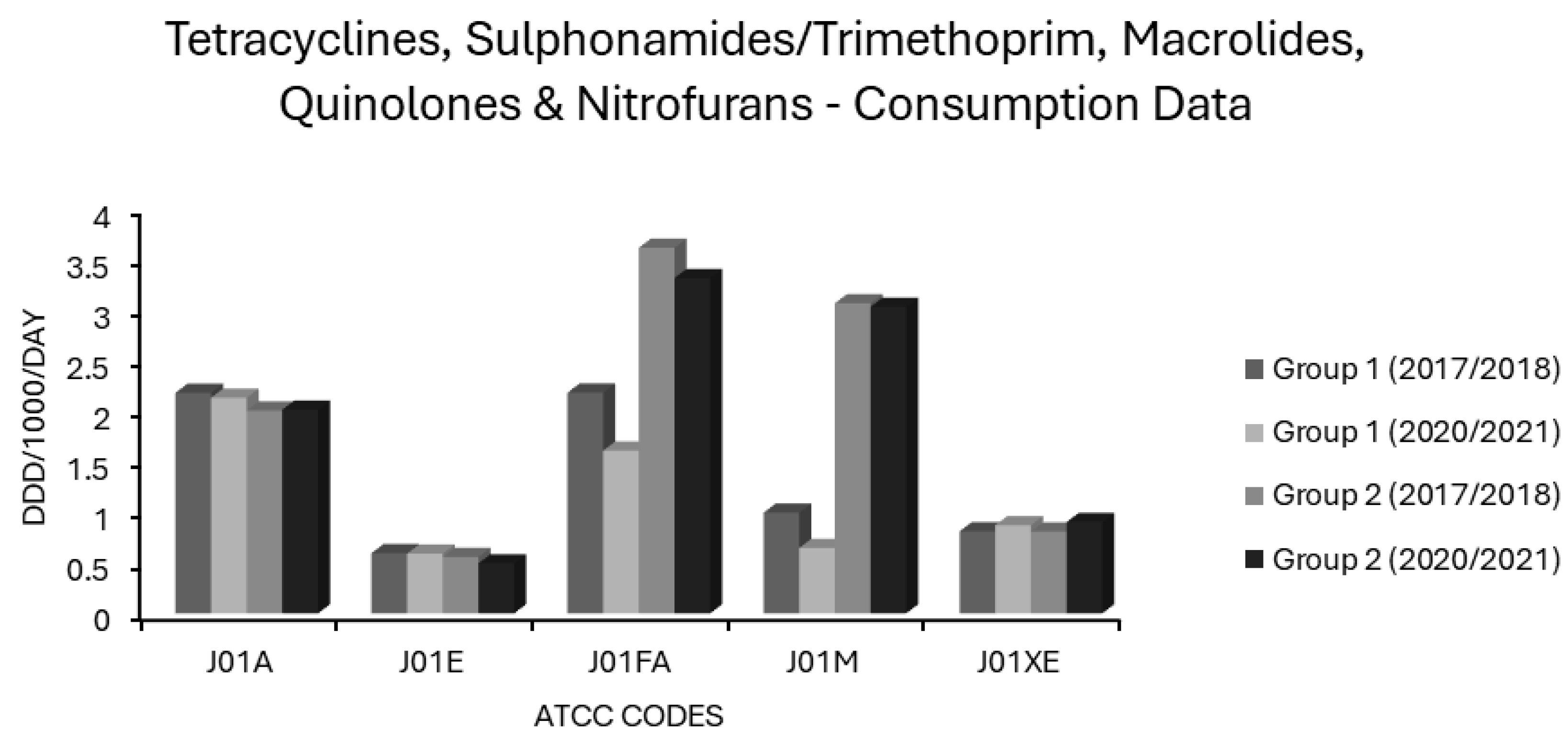

Associations Between Tetracycline Use and Resistance

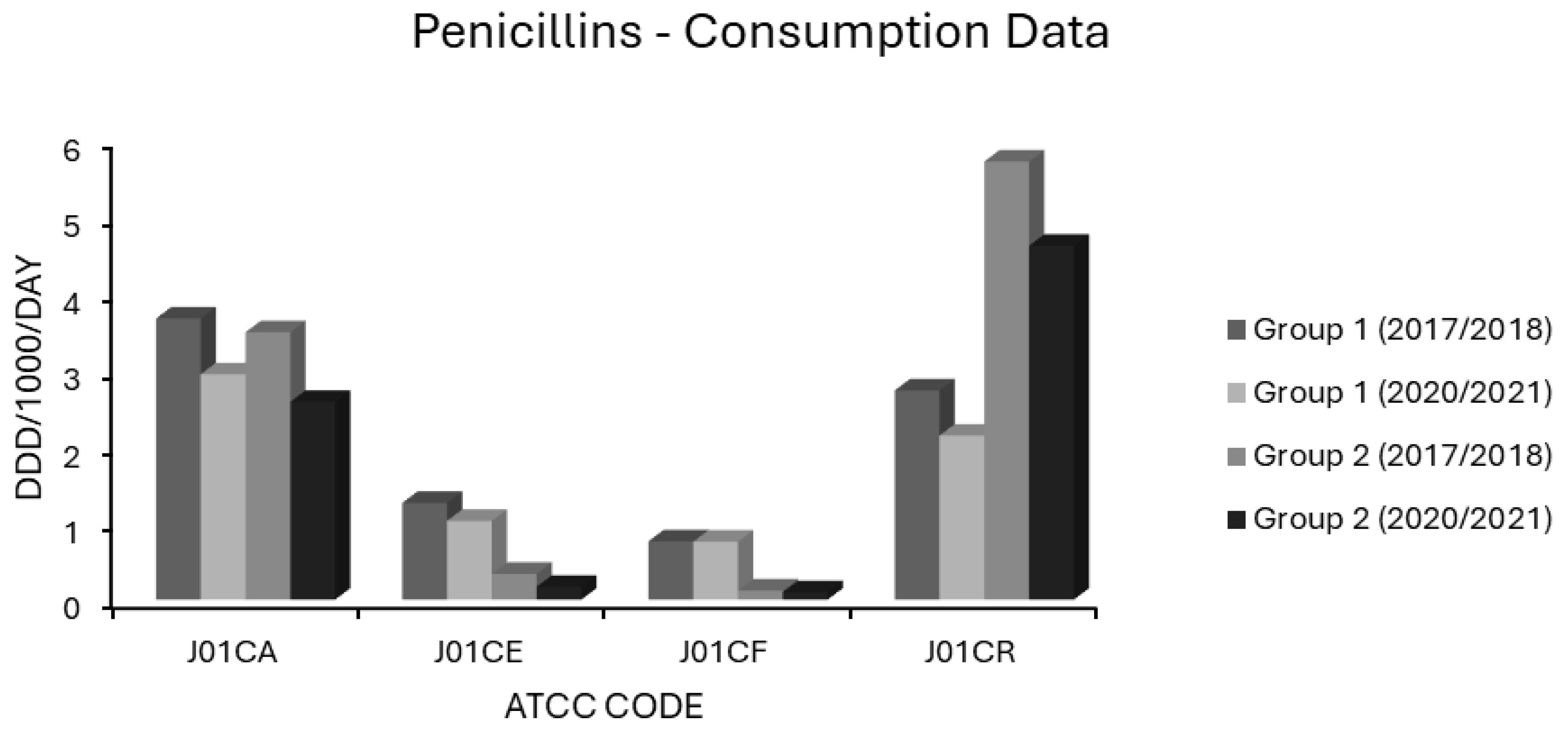

Associations Between Penicillin Use and Resistance

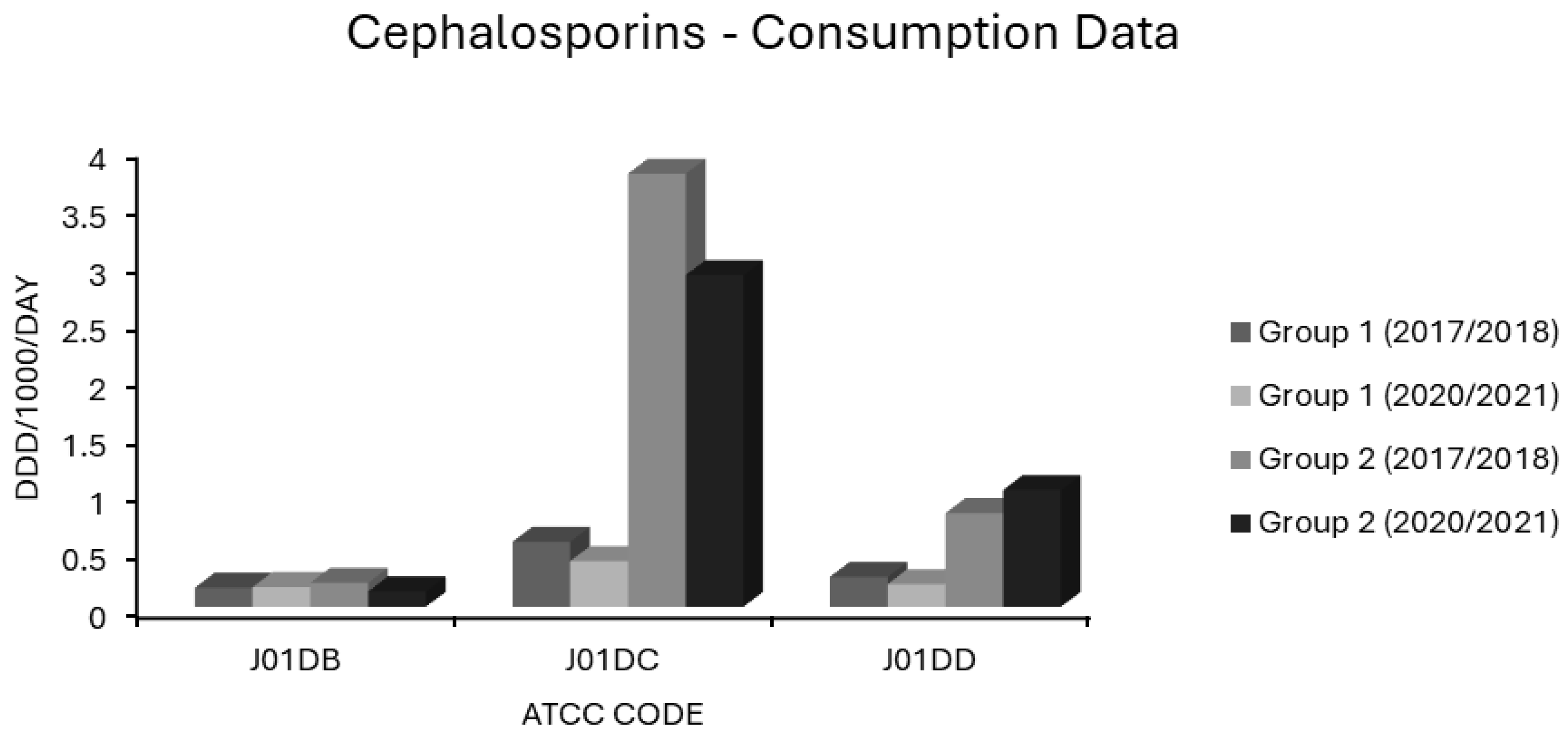

Associations Between Cephalosporin Use and Resistance

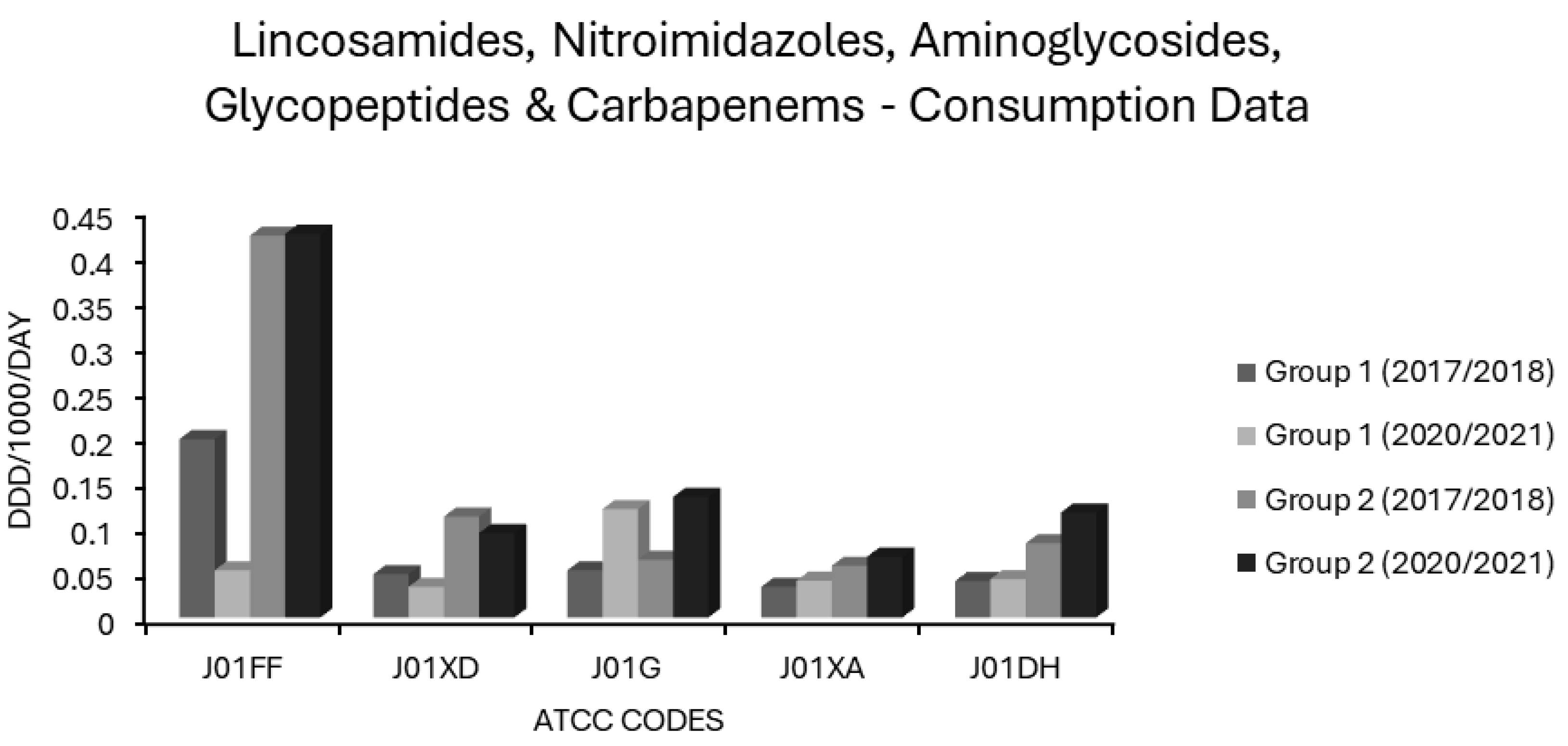

Associations Between Carbapenem Use and Resistance

Associations Between Sulphonamide/Trimethoprim Use and Resistance

Associations Between Macrolide Use and Resistance

Associations Between Lincosamide Use and Resistance

Associations Between Aminoglycoside Use and Resistance

Associations Between Quinolone Use and Resistance

Associations Between Glycopeptide Use and Resistance

Associations Between Nitroimidazole Use and Resistance

Associations Between Nitrofuran Use and Resistance

Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Ombajo, L.A.; Bazira, J.; Chitatanga, R.; Chuki, P.; Gandra, S.; Harbarth, S.; Loeb, M.; Mendelson, M.; et al. The WHO AWaRe Antibiotic Book: providing guidance on optimal use and informing policy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1528–1530. [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Huttner, B.; Moja, L.; Pulcini, C.; Zeng, M.; Mendelson, M.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.; Magrini, N.; et al. Encouraging AWaRe-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use—the new 2019 Essential Medicines List becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1278–1280. [CrossRef]

- Moja, L.; Zanichelli, V.; Mertz, D.; Gandra, S.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.S.; Chuki, P.; Harbarth, S.; Pulcini, C.; Mendelson, M.; et al. WHO's essential medicines and AWaRe: recommendations on first- and second-choice antibiotics for empiric treatment of clinical infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, S1–S51. [CrossRef]

- Zanichelli, V.; Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Moja, L.; Getahun, H.; Pessoa-Silva, C.; Sati, H.; van Weezenbeek, C.; Balkhy, H.; Simão, M.; et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 2023, 101, 290–296. [CrossRef]

- Yonga, P.; Pulcini, C.; Skov, R.; Paño-Pardo, J.R.; Schouten, J. The case for the access, watch, and reserve (AWaRe) universal guidelines for antibiotic use. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 848–849. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.A., 1998. Antibiotic resistance: control strategies. Critical care clinics, 14(2), pp.309-327.

- Cunha, B. Strategies to control antibiotic resistance. Semin. Respir. Infect. 2002, 17, 250–258. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L. Squeezing the antibiotic balloon: the impact of antimicrobial classes on emerging resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 4–16. [CrossRef]

- Heritage, J., Wilcox, M. and Sandoe, J., 2001. Antimicrobial resistance potential. The Lancet, 358(9287), pp.1099-1100.

- Levy, S.B., 2001. Antimicrobial resistance potential. The Lancet, 358(9287), pp.1100-1101.

- Cunha, B.A., 2001. Antimicrobial resistance potential. The Lancet, 358(9287), p.1101.

- Musser, J.M., Beres, S.B., Zhu, L., Olsen, R.J., Vuopio, J., Hyyryläinen, H.L., Gröndahl-Yli-Hannuksela, K., Kristinsson, K.G., Darenberg, J., Henriques-Normark, B. and Hoffmann, S., 2020. Reduced Susceptibility of Streptococcus pyogenes to β-Lactam Antibiotics Associated with Mutations in the Gene Is Geographically Widespread.

- Vannice, K.S.; Ricaldi, J.; Nanduri, S.; Fang, F.C.; Lynch, J.B.; Bryson-Cahn, C.; Wright, T.; Duchin, J.; Kay, M.; Chochua, S.; et al. Streptococcus pyogenes pbp2x Mutation Confers Reduced Susceptibility to β-Lactam Antibiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 71, 201–204. [CrossRef]

- Munch-Petersen, E.; Boundy, C. Yearly incidence of penicillin-resistant staphylococci in man since 1942. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1962, 26, 241–52.

- Wilson, R.; Cockcroft, W.H. The problem of penicillin resistant staphylococcal infection. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1952, 66, 548–51.

- Barber, M.; Rozwadowska-Dowzenko, M. INFECTION BY PENICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCI. Lancet 1948, 252, 641–644. [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, P.C. Antimicrobial Resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: An Overview. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992, 15, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Warren, R.M. Incidence of gonococci relatively resistant to penicillin occurring in the Southampton area of England during 1958 to 1965. British Journal of Venereal Diseases 1968, 44, 80–81. [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, B.A. Antibiotic Resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 24, S98–S101. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.S., John, J.F., Pai, M.S. and Austin, T.L., 1985. Gentamicin vs cefotaxime for therapy of neonatal sepsis: relationship to drug resistance. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 139(11), pp.1086-1089.

- De Champs, C.; Sauvant, M.P.; Chanal, C.; Sirot, D.; Gazuy, N.; Malhuret, R.; Baguet, J.C.; Sirot, J. Prospective survey of colonization and infection caused by expanded-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing members of the family Enterobacteriaceae in an intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989, 27, 2887–90. [CrossRef]

- de Champs, C.; Sirot, D.; Chanal, C.; Poupart, M.-C.; Dumas, M.-P.; Sirot, J. Concomitant dissemination of three extended-spectrum β-lactamases among different Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a French hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1991, 27, 441–457. [CrossRef]

- Pechère, J.-.-C. Resistance to third generation cephalosporins: the current situation. Infection 1989, 17, 333–337. [CrossRef]

- Ballow, C.H. and Schentag, J.J., 1992. Trends in antibiotic utilization and bacterial resistance. Report of the National Nosocomial Resistance Surveillance Group. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 15(2 Suppl), pp.37S-42S.

- Finnström, O.; Isaksson, B.; Haeggman, S.; Burman, L. Control of an outbreak of a highly beta-lactam-resistant Enterobacter cloacae strain in a neonatal special care unit. Acta Paediatr. 1998, 87, 1070–1074. [CrossRef]

- Dancer, S.J., 2001. The problem with cephalosporins. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 48(4), pp.463-478.

- Fukatsu, K.; Saito, H.; Matsuda, T.; Ikeda, S.; Furukawa, S.; Muto, T. Influences of Type and Duration of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis on an Outbreak of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and on the Incidence of Wound Infection. Arch. Surg. 1997, 132, 1320–1325. [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; De Angelis, G.; Cataldo, M.A.; Pozzi, E.; Cauda, R. Does antibiotic exposure increase the risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 61, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Righi, E.; Ansaldi, F.; Molinari, M.; Rebesco, B.; Mcdermott, J.; Fasce, R.; Mussap, M.; Icardi, G.; Pallavicini, F.B.; et al. Impact of Limited Cephalosporin Use on Prevalence of Methicillin-ResistantStaphylococcus aureusin the Intensive Care Unit. J. Chemother. 2009, 21, 633–638. [CrossRef]

- Washio, M., Mizoue, T., Kajioka, T., Yoshimitsu, T., Okayama, M., Hamada, T., Yoshimura, T. and Fujishima, M., 1997. Risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in a Japanese geriatric hospital. Public health, 111(3), pp.187-190.

- Quale, J.; Landman, D.; Saurina, G.; Atwood, E.; DiTore, V.; Patel, K. Manipulation of a Hospital Antimicrobial Formulary to Control an Outbreak of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 1020–1025. [CrossRef]

- May, A.K.; Melton, S.M.; McGwin, G.; Cross, J.M.; Moser, S.A.; Rue, L.W. REDUCTION OF VANCOMYCIN-RESISTANT ENTEROCOCCAL INFECTIONS BY LIMITATION OF BROAD-SPECTRUM CEPHALOSPORIN USE IN A TRAUMA AND BURN INTENSIVE CARE UNIT. Shock 2000, 14, 259–264. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, N.; Vonberg, R.-P.; Gastmeier, P. Outbreaks caused by vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in hematology and oncology departments: A systematic review. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00473. [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.T., Hsu, L.Y., Kurt, K., Weinert, L.A., Mather, A.E., Harris, S.R., Strommenger, B., Layer, F., Witte, W., De Lencastre, H. and Skov, R., 2013. A genomic portrait of the emergence, evolution, and global spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pandemic. Genome research, 23(4), pp.653-664.

- Wilcox, M.H., Chalmers, J.D., Nord, C.E., Freeman, J. and Bouza, E., 2016. Role of cephalosporins in the era of Clostridium difficile infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 72(1), pp.1-18.

- Gerding, D.N., 2004. Clindamycin, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea: this is an antimicrobial resistance problem. Clinical infectious diseases, 38(5), pp.646-648.

- Nelson, D.E., Auerbach, S.B., Baltch, A.L., Desjardin, E., Beck-Sague, C., Rheal, C., Smith, R.P. and Jarvis, W.R., 1994. Epidemic Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: role of second-and third-generation cephalosporins. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 15(2), pp.88-94.

- Owens Jr, R.C., Donskey, C.J., Gaynes, R.P., Loo, V.G. and Muto, C.A., 2008. Antimicrobial-associated risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46(Supplement_1), pp. S19-S31.

- Deshpande, A.; Pant, C.; Jain, A.; Fraser, T.G.; Rolston, D.D.K. Do fluoroquinolones predispose patients to Clostridium difficile associated disease? A review of the evidence. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 2007, 24, 329–333. [CrossRef]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Katukoori, S.; Bollam, N.; George, I.; Yaeger, L.H.; Chavez, M.A.; Tetteh, E.; Yarrabelli, S.; Pulcini, C.; et al. Exposure to World Health Organization's AWaRe antibiotics and isolation of multidrug resistant bacteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1193–1202. [CrossRef]

- Acar, J. Broad- and narrow-spectrum antibiotics: an unhelpful categorization. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1997, 3, 395–396. [CrossRef]

- van Saene, R.; Fairclough, S.; Petros, A. Broad- and narrow-spectrum antibiotics: a different approach. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1998, 4, 56–57. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Cesar, A.; Snow, T.A.C.; Saleem, N.; Arulkumaran, N.; Singer, M. Efficacy of Doxycycline for Mild-to-Moderate Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Cevik, M.; Russell, C.; Evans, M.; Mackintosh, C. Doxycycline for the empiric treatment of low-severity hospital acquired pneumonia. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, 76. [CrossRef]

- Ailani, R.K.; Agastya, G.; Ailani, R.K.; Mukunda, B.N.; Shekar, R. Doxycycline Is a Cost-effective Therapy for Hospitalized Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 266–270. [CrossRef]

- Mokabberi, R.; Haftbaradaran, A.; Ravakhah, K. Doxycycline vs. levofloxacin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009, 35, 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Ludlam, H.A. and Enoch, D.A., 2008. Doxycycline or moxifloxacin for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in the UK? International journal of antimicrobial agents, 32(2), pp.101-105.

- Jones, R.N.; Sader, H.S.; Fritsche, T.R. Doxycycline use for community-acquired pneumonia: contemporary in vitro spectrum of activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae (1999–2002). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 49, 147–149. [CrossRef]

- Musher, D.M. Doxycycline to Treat Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 692–693. [CrossRef]

- Duggar, B.M., 1948. Aureomycin-a New Antibiotic.

- Finlay, A.C., Hobby, G.L., P’an, S.Y., Regna, P.P., Routien, J.B., Seeley, D.B., Shull, G.M., Sobin, B.A., Solomons, I.A., Vinson, J.W. and Kane, J.H., 1950. Terramycin, a new antibiotic. Science, 111(2874), pp.85-85.

- Ehrlich, J.; Bartz, Q.R.; Smith, R.M.; Joslyn, D.A.; Burkholder, P.R. Chloromycetin, a New Antibiotic From a Soil Actinomycete. Science 1947, 106, 417. PMID: 17737966. [CrossRef]

- Petrikkos, G.; Markogiannakis, A.; Papapareskevas, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Stefanakos, G.; Zissis, N.P.; Avlamis, A. Differences in the changes in resistance patterns to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins and piperacillin/tazobactam among Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli clinical isolates following a restriction policy in a Greek tertiary care hospital. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2007, 29, 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Bantar, C.; Vesco, E.; Heft, C.; Salamone, F.; Krayeski, M.; Gomez, H.; Coassolo, M.A.; Fiorillo, A.; Franco, D.; Arango, C.; et al. Replacement of Broad-Spectrum Cephalosporins by Piperacillin-Tazobactam: Impact on Sustained High Rates of Bacterial Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 392–395. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Pai, H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, N.H.; Eun, B.W.; Kang, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Choi, E.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Kim, E.C.; et al. Control of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a children's hospital by changing antimicrobial agent usage policy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 629–637. [CrossRef]

- Carrié, C.; Bardonneau, G.; Petit, L.; Ouattara, A.; Gruson, D.; Pereira, B.; Biais, M. Piperacillin-tazobactam should be preferred to third-generation cephalosporins to treat wild-type inducible AmpC-producing Enterobacterales in critically ill patients with hospital or ventilator-acquired pneumonia. J. Crit. Care 2020, 56, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Stearne, L.E., van Boxtel, D., Lemmens, N., Goessens, W.H., Mouton, J.W. and Gyssens, I.C., 2004. Comparative study of the effects of ceftizoxime, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam concentrations on antibacterial activity and selection of antibiotic-resistant mutants of Enterobacter cloacae and Bacteroides fragilis in vitro and in vivo in mixed-infection abscesses. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 48(5), pp.1688-1698.

- Gamage, H.K.A.H.; Venturini, C.; Tetu, S.G.; Kabir, M.; Nayyar, V.; Ginn, A.N.; Roychoudhry, B.; Thomas, L.; Brown, M.; Holmes, A.; et al. Third generation cephalosporins and piperacillin/tazobactam have distinct impacts on the microbiota of critically ill patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.W., 1999. Decreased antimicrobial resistance after changes in antibiotic use. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 19(8P2), pp.129S-132S.

- Barry, A.L.; Pfaller, M.A.; Fuchs, P.C. The antibacterial activity of co-amoxiclav. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1993, 31, 612–615. [CrossRef]

- Gerding, D.N., 1997. Is there a relationship between vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infection and Clostridium difficile infection? Clinical Infectious Diseases, 25(Supplement_2), pp. S206-S210.

- Al-Nassir, W.N.; Sethi, A.K.; Li, Y.; Pultz, M.J.; Riggs, M.M.; Donskey, C.J. Both Oral Metronidazole and Oral Vancomycin Promote Persistent Overgrowth of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci during Treatment of Clostridium difficile -Associated Disease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2403–2406. [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, A.; Pultz, N.J.; Ray, A.J.; Hoyen, C.K.; Eckstein, E.C.; Donskey, C.J. Antianaerobic Antibiotic Therapy Promotes Overgrowth of Antibiotic-Resistant, Gram-Negative Bacilli and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in the Stool of Colonized Patients. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2003, 24, 644–649. [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; Empson, M.; Boardman, C.; Sindhusake, D.; Lokan, J.; Brown, G.V. Risk Factors for Colonization With Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in a Melbourne Hospital. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2001, 22, 624–629. [CrossRef]

- Donskey, C.J.; Rice, L.B. The influence of antibiotics on spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci: the potential role of selective use of antibiotics as a control measure. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 1999, 21, 57–65. [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Y.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Samore, M.H. Antecedent Treatment with Different Antibiotic Agents as a Risk Factor for Vancomycin-ResistantEnterococcus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 802–807. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Nachamkin, I.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Coffin, S.E.; Linkin, D.R.; Fishman, N.O.; Weiner, M.G.; Hu, B.; Tolomeo, P.; Lautenbach, E. Risk Factors for Gastrointestinal Tract Colonization with Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)–Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella Species in Hospitalized Patients. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2012, 33, 1242–1245. [CrossRef]

- Vibet, M.A., Roux, J., Montassier, E., Corvec, S., Juvin, M.E., Ngohou, C., Lepelletier, D. and Batard, E., 2015. Systematic analysis of the relationship between antibiotic use and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in a French hospital: a time series analysis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 34, pp.195 Boutrot, M., Azougagh, K., Guinard, J., Boulain, T. and Barbier, F., 2019. Antibiotics with activity against intestinal anaerobes and the hazard of acquired colonization with ceftriaxone-resistant Gram-negative pathogens in ICU patients: a propensity score-based analysis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 74(10), pp.3095-3103.7-1963.

- Boutrot, M.; Azougagh, K.; Guinard, J.; Boulain, T.; Barbier, F. Antibiotics with activity against intestinal anaerobes and the hazard of acquired colonization with ceftriaxone-resistant Gram-negative pathogens in ICU patients: a propensity score-based analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3095–3103. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.C.; Arakkal, A.T.; Sewell, D.K.; Segre, A.M.; Tholany, J.; Polgreen, P.M.; CDC MInD-Healthcare Group Comparison of Different Antibiotics and the Risk for Community-Associated Clostridioides difficile Infection: A Case–Control Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad413. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Khanafer, N.; Daneman, N.; Fisman, D.N. Meta-Analysis of Antibiotics and the Risk of Community-Associated Clostridium difficile Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2326–2332. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Pasupuleti, V.; Thota, P.; Pant, C.; Rolston, D.D.K.; Sferra, T.J.; Hernandez, A.V.; Donskey, C.J. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 1951–1961. [CrossRef]

- EARS-NET Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2023–2021 data. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and World Health Organization; 2023. Available at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2023-2021-data.

- ESAC-NET Antimicrobial consumption dashboard. Available at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/surveillance-and-disease-data/database.

- Levy, S.B., 1984. Resistance to the tetracyclines. Antimicrobial drug resistance, pp.191-240.

- Leflon-Guibout, V.; Jurand, C.; Bonacorsi, S.; Espinasse, F.; Guelfi, M.C.; Duportail, F.; Heym, B.; Bingen, E.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.-H. Emergence and Spread of Three Clonally Related Virulent Isolates of CTX-M-15-Producing Escherichia coli with Variable Resistance to Aminoglycosides and Tetracycline in a French Geriatric Hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3736–3742. [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, N., Scott, H.M., Norby, B., Loneragan, G.H., Vinasco, J., McGowan, M., Cottell, J.L., Chengappa, M.M., Bai, J. and Boerlin, P., 2013. Effects of ceftiofur and chlortetracycline treatment strategies on antimicrobial susceptibility and on tet (A), tet (B), and bla CMY-2 resistance genes among E. coli isolated from the feces of feedlot cattle. PloS one, 8(11), p.e80575.

- Carpenter, L.; Miller, S.; Flynn, E.; Choo, J.M.; Collins, J.; Shoubridge, A.P.; Gordon, D.; Lynn, D.J.; Whitehead, C.; Leong, L.E.; et al. Exposure to doxycycline increases risk of carrying a broad range of enteric antimicrobial resistance determinants in an elderly cohort. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106243. [CrossRef]

- Truong, R.; Tang, V.; Grennan, T.; Tan, D.H.S. A systematic review of the impacts of oral tetracycline class antibiotics on antimicrobial resistance in normal human flora. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022, 4, dlac009. [CrossRef]

- Kantele, A.; Lääveri, T.; Mero, S.; Vilkman, K.; Pakkanen, S.H.; Ollgren, J.; Antikainen, J.; Kirveskari, J. Antimicrobials Increase Travelers' Risk of Colonization by Extended-Spectrum Betalactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 837–846. [CrossRef]

- Ruppé, E.; Armand-Lefèvre, L.; Estellat, C.; Consigny, P.-H.; El Mniai, A.; Boussadia, Y.; Goujon, C.; Ralaimazava, P.; Campa, P.; Girard, P.-M.; et al. High Rate of Acquisition but Short Duration of Carriage of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae After Travel to the Tropics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 593–600. [CrossRef]

- Lauhio, A.; Tervahartiala, T.; Leppilahti, J.; Golub, L.M.; Ryan, M.E.; Sorsa, T. The Use of Doxycycline and Tetracycline in Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Colonization.. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1031–1031. [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.-M.; Bercot, B.; Assoumou, L.; Rubenstein, E.; Algarte-Genin, M.; Pialoux, G.; Katlama, C.; Surgers, L.; Bébéar, C.; Dupin, N.; et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis and meningococcal group B vaccine to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted infections in France (ANRS 174 DOXYVAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial with a 2 × 2 factorial design. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1093–1104. [CrossRef]

- Vanbaelen, T.; Manoharan-Basil, S.S.; Kenyon, C. Studies of post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline should consider population-level selection for antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e606–e607. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.G.; Bustetter, L.A.; Gorbach, S.L.; Onderdonk, A.B. Comparative Effect of Tetracycline and Doxycycline on the Occurrence of Resistant Escherichia coli in the Fecal Flora. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1975, 7, 55–57. [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Koch, O.; Laurenson, I.; O'Shea, D.; Sutherland, R.; Mackintosh, C. Diagnosis and features of hospital-acquired pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2015, 92, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mohammed, T.; Metersky, M.; Anzueto, A.; A Alvarez, C.; Mortensen, E.M. Effectiveness of Beta-Lactam plus Doxycycline for Patients Hospitalized with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 75, 118–124. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, Y.Y.; Sohn, Y.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Han, M.S.; Yun, K.W.; Kim, K.; Park, J.Y.; Choi, J.H.; Cho, E.Y.; et al. Clinical Efficacy of Doxycycline for Treatment of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia in Children. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 192. [CrossRef]

- Reda, C.; Quaresima, T.; Pastoris, M.C. In-vitro activity of six intracellular antibiotics against Legionella pneumophila strains of human and environmental origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1994, 33, 757–764. [CrossRef]

- Jasper, A.S.; Musuuza, J.S.; Tischendorf, J.S.; Stevens, V.W.; Gamage, S.D.; Osman, F.; Safdar, N. Are Fluoroquinolones or Macrolides Better for Treating Legionella Pneumonia? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 1979–1989. [CrossRef]

- Isenman, H.; Anderson, T.; Chambers, S.T.; Podmore, R.G.; Murdoch, D.R. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of clinical Legionella longbeachae isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 73, 1102–1104. [CrossRef]

- White, C.R.; Jodlowski, T.Z.; Atkins, D.T.; Holland, N.G. Successful Doxycycline Therapy in a Patient With Escherichia coli and Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infection. J. Pharm. Pr. 2016, 30, 464–467. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.A. Oral doxycycline for non-systemic urinary tract infections (UTIs) due to P. aeruginosa and other Gram negative uropathogens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 2865–2868. [CrossRef]

- Chastain, D.B.; King, S.T.; Stover, K.R. Rethinking urinary antibiotic breakpoints: analysis of urinary antibiotic concentrations to treat multidrug resistant organisms. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 497. [CrossRef]

- Benavides, T.M.; Aden, J.K.; Giancola, S.E. Evaluating outcomes associated with revised fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Enterobacterales urinary tract infections: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 741–749. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, M.; Verbon, A.; Lous, J.; Goessens, W.; Stricker, B.H. Use of other antimicrobial drugs is associated with trimethoprim resistance in patients with urinary tract infections caused by E. coli. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 2283–2290. [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, K.B.; Freeman, R.; Muller-Pebody, B.; Rooney, G.; Henderson, K.L.; Robotham, J.V.; Smieszek, T. Association between use of different antibiotics and trimethoprim resistance: going beyond the obvious crude association. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1700–1707. [CrossRef]

- Steinke, D.T.; Seaton, R.A.; Phillips, G.; MacDonald, T.M.; Davey, P.G. Prior trimethoprim use and trimethoprim-resistant urinary tract infection: a nested case-control study with multivariate analysis for other risk factors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 781–787. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S.; Roberts, Z.; Dunstan, F.; Butler, C.; Howard, A.; Palmer, S. Prior antibiotics and risk of antibiotic-resistant community-acquired urinary tract infection: a case–control study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 92–99. [CrossRef]

- Skarpeid, P.L.; Høye, S. Phenoxymethylpenicillin Versus Amoxicillin for Infections in Ambulatory Care: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 81. [CrossRef]

- Plejdrup Hansen, M., Høye, S. and Hedin, K., 2024. Antibiotic treatment recommendations for acute respiratory tract infections in Scandinavian general practices—time for harmonization? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, pp.1-4.

- Rhedin, S.; Kvist, B.; Osvald, E.C.; Karte, G.; Smew, A.I.; Nauclér, P.; Lundholm, C.; Almqvist, C. Penicillin V versus amoxicillin for pneumonia in children—a Swedish nationwide emulated target trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1418–1425. [CrossRef]

- Rhedin, S.; Galanis, I.; Granath, F.; Ternhag, A.; Hedlund, J.; Spindler, C.; Naucler, P. Narrow-spectrum ß-lactam monotherapy in hospital treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: a register-based cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Pérez, A.; Carandell, E.; García-Sangenís, A.; Rezola, J.; Llorente, M.; Gestoso, S.; Bobé, F.; Román-Rodríguez, M.; Cots, J.M.; et al. Efficacy of high doses of penicillin versus amoxicillin in the treatment of uncomplicated community acquired pneumonia in adults. A non-inferiority controlled clinical trial. Atencion primaria 2019, 51, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Thegerström, J.; Månsson, V.; Riesbeck, K.; Resman, F. Benzylpenicillin versus wide-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics as empirical treatment of Haemophilus influenzae-associated lower respiratory tract infections in adults; a retrospective propensity score-matched study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 1761–1775. [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.; Kolsum, U.; Jackson, S.; Barraclough, R.; Maschera, B.; Simpson, K.D.; Pascal, T.G.; Durviaux, S.; Hessel, E.M.; Singh, D. Ampicillin resistance in Haemophilus influenzae from COPD patients in the UK. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, ume 12, 1507–1518. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.F., Brauer, A.L., Grant, B.J. and Sethi, S., 2005. Moraxella catarrhalis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: burden of disease and immune response. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 172(2), pp.195-199.

- Geddes, A.M. and Gould, I.M., 2010. Ampicillin, amoxicillin and other ampicillin-like penicillins. Kucers’ the use of antibiotics. 6th ed. London (UK): Hodder Arnold, p.65.

- Sonne, M. and Jawetz, E., 1968. Comparison of the action of ampicillin and benzylpenicillin on enterococci in vitro. Applied Microbiology, 16(4), pp.645-648.

- Murray, B.E., 1990. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clinical microbiology reviews, 3(1), pp.46-65.

- Briggs, S.; Broom, M.; Duffy, E.; Everts, R.; Everts, G.; Lowe, B.; McBride, S.; Bhally, H. Outpatient continuous-infusion benzylpenicillin combined with either gentamicin or ceftriaxone for enterococcal endocarditis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2168–2171. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Enoki, Y.; Uno, S.; Uwamino, Y.; Iketani, O.; Hasegawa, N.; Matsumoto, K. Stability of benzylpenicillin potassium and ampicillin in an elastomeric infusion pump. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 856–859. [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M. and Tulkens, P.M., 2009. Temocillin revived. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 63(2), pp.243-245.

- Jules, K.; Neu, H.C. Antibacterial activity and beta-lactamase stability of temocillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 22, 453–460. [CrossRef]

- Van Landuyt, H.W.; Pyckavet, M.; Lambert, A.; Boelaert, J. In vitro activity of temocillin (BRL 17421), a novel beta-lactam antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 22, 535–540. [CrossRef]

- Godtfredsen, W.O., 1977. An introduction to mecillinam. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 3(suppl_B), pp.1-4.

- Reeves, D.S., 1977. Antibacterial activity of mecillinam. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 3(suppl_B), pp.5-11.

- Giske, C. Contemporary resistance trends and mechanisms for the old antibiotics colistin, temocillin, fosfomycin, mecillinam and nitrofurantoin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 899–905. [CrossRef]

- Frimodt-Møller, N.; Simonsen, G.S.; Larsen, A.R.; Kahlmeter, G. Pivmecillinam, the paradigm of an antibiotic with low resistance rates in Escherichia coli urine isolates despite high consumption. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 78, 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Jansåker, F.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Benfield, T.L.; Knudsen, J.D. Mecillinam for the treatment of acute pyelonephritis and bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae: a literature review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, ume 11, 761–771. [CrossRef]

- Boel, J.B., Antsupova, V., Knudsen, J.D., Jarløv, J.O., Arpi, M. and Holzknecht, B.J., 2021. Intravenous mecillinam compared with other β-lactams as targeted treatment for Escherichia coli or Klebsiella spp. bacteraemia with urinary tract focus. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 76(1), pp.206-211.

- Neu, H.C. Penicillin-binding proteins and role of amdinocillin in causing bacterial cell death. Am. J. Med. 1983, 75, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.C., Sanders Jr, W.E., Goering, R.V. and McCloskey, R.V., 1987. Leakage of beta-lactamase: a second mechanism for antibiotic potentiation by amdinocillin. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 31(8), pp.1164-1168.

- A Craig, W.; Ebert, S.C. Continuous infusion of beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992, 36, 2577–2583. [CrossRef]

- Everts, R.J.; Begg, R.; Gardiner, S.J.; Zhang, M.; Turnidge, J.; Chambers, S.T.; Begg, E.J. Probenecid and food effects on flucloxacillin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 42–53. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Arkell, P.; Riezk, A.; Gilchrist, M.; Wheeler, G.; Hope, W.; Holmes, A.H.; Rawson, T.M. Addition of probenecid to oral β-lactam antibiotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 2364–2372. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Moreno, M.; Katargina, O.; Carulla, M.; Rubio, C.; Jardí, A.; Zaragoza, J. Mechanisms of reduced susceptibility to amoxycillin-clavulanic acid in Escherichia coli strains from the health region of Tortosa (Catalonia, Spain). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Waltner-Toews, R.I., Paterson, D.L., Qureshi, Z.A., Sidjabat, H.E., Adams-Haduch, J.M., Shutt, K.A., Jones, M., Tian, G.B., Pasculle, A.W. and Doi, Y., 2011. Clinical characteristics of bloodstream infections due to ampicillin-sulbactam-resistant, non-extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and the role of TEM-1 hyperproduction. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 55(2), pp.495-501.

- Cuevas, O.; Oteo, J.; Lázaro, E.; Aracil, B.; de Abajo, F.; García-Cobos, S.; Ortega, A.; Campos, J.; on behalf of the Spanish EARS-Net Study Group; Fontanals, D.; et al. Significant ecological impact on the progression of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli with increased community use of moxifloxacin, levofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 66, 664–669. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Casanova, J.; Gómez-Zorrilla, S.; Prim, N.; Molin, A.D.; Echeverría-Esnal, D.; Gracia-Arnillas, M.P.; Sendra, E.; Güerri-Fernández, R.; Durán-Jordà, X.; Padilla, E.; et al. Risk Factors for Amoxicillin-Clavulanate Resistance in Community-Onset Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae: The Role of Prior Exposure to Fluoroquinolones. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 582. [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M., 2014. Of stewardship, motherhood and apple pie. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 43(4), pp.319-322.

- Dancer, S.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Corcoran, D.; Christison, F.; Farmer, D.; Robertson, C. Approaching zero: temporal effects of a restrictive antibiotic policy on hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing coliforms and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Liebowitz, L.; Blunt, M. Modification in prescribing practices for third-generation cephalosporins and ciprofloxacin is associated with a reduction in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia rate. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008, 69, 328–336. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.D., McGregor, J.C., Johnson, J.A., Strauss, S.M., Moore, A.C., Standiford, H.C., Hebden, J.N. and Morris Jr, J.G., 2007. Risk factors for colonization with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing bacteria and intensive care unit admission. Emerging infectious diseases, 13(8), p.1144.

- Tanaka, A.; Takada, T.; Kawarada, Y.; Nimura, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Miura, F.; Hirota, M.; Wada, K.; Mayumi, T.; Gomi, H.; et al. Antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surg. 2007, 14, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.K.-T.; Chow, K.M.; Cho, Y.; Fan, S.; E Figueiredo, A.; Harris, T.; Kanjanabuch, T.; Kim, Y.-L.; Madero, M.; Malyszko, J.; et al. ISPD peritonitis guideline recommendations: 2022 update on prevention and treatment. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2022, 42, 110–153. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, N.D.; Irvine, S.C.; Helps, A.; Robb, F.; Jones, B.L.; Seaton, R.A. Restrictive antibiotic stewardship associated with reduced hospital mortality in gram-negative infection. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2016, 110, hcw134–161. [CrossRef]

- Enoch, D.A.; Phillimore, N.; Mlangeni, D.A.; Salihu, H.M.; Sismey, A.; Aliyu, S.H.; Karas, J.A. Outcome for Gram-negative bacteraemia when following restrictive empirical antibiotic guidelines. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2010, 104, 411–419. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, A.L.V.; Shea, K.M.; Daley, M.J.; Huth, R.G.; Jaso, T.C.; Bissett, J.; Hemmige, V. Are first-generation cephalosporins obsolete? A retrospective, non-inferiority, cohort study comparing empirical therapy with cefazolin versus ceftriaxone for acute pyelonephritis in hospitalized patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1665–1671. [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, M.; Zadka, H.; Weiss-Meilik, A.; Ben-Ami, R. Effectiveness and safety of an institutional aminoglycoside-based regimen as empirical treatment of patients with pyelonephritis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 2307–2313. [CrossRef]

- Leman, P.; Mukherjee, D. Flucloxacillin alone or combined with benzylpenicillin to treat lower limb cellulitis: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg. Med. J. 2005, 22, 342–346. [CrossRef]

- Brindle, R.; Williams, O.M.; Davies, P.; Harris, T.; Jarman, H.; Hay, A.D.; Featherstone, P. Adjunctive clindamycin for cellulitis: a clinical trial comparing flucloxacillin with or without clindamycin for the treatment of limb cellulitis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013260. [CrossRef]

- Quirke, M.; O’sullivan, R.; Mccabe, A.; Ahmed, J.; Wakai, A. Are two penicillins better than one? A systematic review of oral flucloxacillin and penicillin V versus oral flucloxacillin alone for the emergency department treatment of cellulitis. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 170–174. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.B.; Veve, M.P.; Wagner, J.L. Cephalosporins: A Focus on Side Chains and β-Lactam Cross-Reactivity. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 103. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.K.; Vivier, E.; Bouziad, K.A.; Zahar, J.-R.; Pommier, C.; Parmeland, L.; Pariset, C.; Misslin, P.; Haond, C.; Poirié, P.; et al. A hospital-wide intervention replacing ceftriaxone with cefotaxime to reduce rate of healthcare-associated infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the intensive care unit. Intensiv. Care Med. 2018, 44, 672–673. [CrossRef]

- Wendt, S.; Ranft, D.; Rodloff, A.C.; Lippmann, N.; Lübbert, C. Switching From Ceftriaxone to Cefotaxime Significantly Contributes to Reducing the Burden of Clostridioides difficile infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Pilmis, B.; Jiang, O.; Mizrahi, A.; Van, J.-C.N.; Lourtet-Hascoët, J.; Voisin, O.; Le Lorc’h, E.; Hubert, S.; Ménage, E.; Azria, P.; et al. No significant difference between ceftriaxone and cefotaxime in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in the gut microbiota of hospitalized patients: A pilot study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 617–623. [CrossRef]

- Burdet, C.; Grall, N.; Linard, M.; Bridier-Nahmias, A.; Benhayoun, M.; Bourabha, K.; Magnan, M.; Clermont, O.; D’Humières, C.; Tenaillon, O.; et al. Ceftriaxone and Cefotaxime Have Similar Effects on the Intestinal Microbiota in Human Volunteers Treated by Standard-Dose Regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.; Bertrand, X.; Rogues, A.-M.; Péfau, M.; Alfandari, S.; Gauzit, R.; Dumartin, C.; Gbaguidi-Haore, H.; on behalf of the ATB-RAISIN network steering committee; Berger-Carbonne, A.; et al. Higher third-generation cephalosporin prescription proportion is associated with lower probability of reducing carbapenem use: a nationwide retrospective study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018, 7, 11. [CrossRef]

- Guidance on the use of co-trimoxazole in secondary care in NHS Scotland. Available at https://www.sapg.scot/media/7364/20230116-sapg-statement-in-support-of-co-trimoxazole.pdf.

- Monnet, D.L., MacKenzie, F.M., López-Lozano, J.M., Beyaert, A., Camacho, M., Wilson, R., Stuart, D. and Gould, I.M., 2004. Antimicrobial drug use and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Aberdeen, 1996–2000. Emerging infectious diseases, 10(8), p.1432.

- Dancer, S.J. The effect of antibiotics on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 61, 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, K.G.; Lu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Walensky, R.P.; Choi, H.K. Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study. BMJ 2018, 361, k2400. [CrossRef]

- Graffunder, E.M.; Venezia, R.A. Risk factors associated with nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection including previous use of antimicrobials. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 999–1005. [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, R. Mechanisms of Resistance to Macrolides and Lincosamides: Nature of the Resistance Elements and Their Clinical Implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 482–492. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.C.P.; Woerther, P.-L.; Bouvet, M.; Andremont, A.; Leclercq, R.; Canu, A. Escherichia colias Reservoir for Macrolide Resistance Genes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1648–1650. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Komiya, K.; Ichihara, S.; Nagaoka, Y.; Yamanaka, M.; Nishiyama, Y.; Hiramatsu, K.; Kadota, J.-I. Factors Associated with Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteria Isolated from Respiratory Samples. Intern. Med. 2023, 62, 2043–2050. [CrossRef]

- Dualleh, N.; Chanchiri, I.; Skjøt-Arkil, H.; Pedersen, A.K.; Rosenvinge, F.S.; Johansen, I.S. Colonization with multiresistant bacteria in acute hospital care: the association of prior antibiotic consumption as a risk factor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3675–3681. [CrossRef]

- Charles, P.G.P.; Whitby, M.; Fuller, A.J.; Stirling, R.; Wright, A.A.; Korman, T.M.; Holmes, P.W.; Christiansen, K.J.; Waterer, G.W.; Pierce, R.J.P.; et al. The Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Australia: Why Penicillin plus Doxycycline or a Macrolide Is the Most Appropriate Therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1513–1521. [CrossRef]

- Teh, B.; Grayson, M.L.; Johnson, P.D.R.; Charles, P.G.P. Doxycycline vs. macrolides in combination therapy for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E71–E73. [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, A.; Remmelts, H.H.F.; Rijkers, G.T.; Hoepelman, A.I.M.; Biesma, D.H.; Oosterheert, J.J. Immunomodulatory effects of macrolides during community-acquired pneumonia: a literature review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 67, 530–540. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Feldman, C. The Global Burden of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults, Encompassing Invasive Pneumococcal Disease and the Prevalence of Its Associated Cardiovascular Events, with a Focus on Pneumolysin and Macrolide Antibiotics in Pathogenesis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11038. [CrossRef]

- Burki, T.K. β-lactam monotherapy is non-inferior to combination treatment for community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 347. [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam, A.; Aliberti, S.; Cillóniz, C.; Torres, A.; Blasi, F.; Chalmers, J.D. Evaluation of severity score-guided approaches to macrolide use in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602306. [CrossRef]

- Klugman, K.P.; Lonks, J.R. Hidden Epidemic of Macrolide-resistant Pneumococci. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 802–807. [CrossRef]

- Principi, N.; Esposito, S. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae: its role in respiratory infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 68, 506–511. [CrossRef]

- Montagnani, F.; Zanchi, A.; Stolzuoli, L.; Croci, L.; Cellesi, C. Clindamycin-resistantStreptococcus pneumoniae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 801–802. [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, N.; Ohkoshi, Y.; Okubo, T.; Sato, T.; Kuwahara, O.; Fujii, N.; Tamura, Y.; Yokota, S.-I. High Prevalence of Cross-Resistance to Aminoglycosides in Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates. Chemotherapy 2013, 59, 379–384. [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Woosley, L.N.; Serio, A.W.; Krause, K.M.; Flamm, R.K. Activity of plazomicin compared with other aminoglycosides against isolates from European and adjacent countries, including Enterobacteriaceae molecularly characterized for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and other resistance mechanisms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 3346–3354. [CrossRef]

- Paltansing, S.; Kraakman, M.E.M.; Ras, J.M.C.; Wessels, E.; Bernards, A.T. Characterization of fluoroquinolone and cephalosporin resistance mechanisms in Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a Dutch teaching hospital reveals the presence of an Escherichia coli ST131 clone with a specific mutation in parE. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 68, 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M., Serio, A.W., Kane, T.R. and Connolly, L.E., 2016. Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 6(6), p.a027029.

- Eliopoulos, G.M.; Drusano, G.L.; Ambrose, P.G.; Bhavnani, S.M.; Bertino, J.S.; Nafziger, A.N.; Louie, A. Back to the Future: Using Aminoglycosides Again and How to Dose Them Optimally. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 753–760. [CrossRef]

- Neu, H.C. Antibiotics in the second half of the 1980s: Areas of future development and the effect of new agents on aminoglycoside use. Am. J. Med. 1986, 80, 195–203. [CrossRef]

- Naparstek, L.; Carmeli, Y.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Banin, E. Biofilm formation and susceptibility to gentamicin and colistin of extremely drug-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 1027–1034. [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.C., 1999, October. The fluoroquinolones. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 74, No. 10, pp. 1030-1037). Elsevier.

- Wilson, C.; Seaton, R.A. Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Frail Elderly. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2024, 85, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Scheld, W.M. Maintaining Fluoroquinolone Class Efficacy: Review of Influencing Factors. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sahm, D.F., Thornsberry, C., Jones, M.E. and Karlowsky, J.A., 2003. Factors influencing fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 9(12), p.1651.

- Ofek-Shlomai, N., Benenson, S., Ergaz, Z., Peleg, O., Braunstein, R. and Bar-Oz, B., 2012. Gastrointestinal colonization with ESBL-producing Klebsiella in preterm babies—is vancomycin to blame? European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases, 31, pp.567-570.

- Lautenbach, E.; Bilker, W.B.; Brennan, P.J. Enterococcal Bacteremia: Risk Factors for Vancomycin Resistance and Predictors of Mortality. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 1999, 20, 318–323. [CrossRef]

- Peel, T.; Cheng, A.; Spelman, T.; Huysmans, M.; Spelman, D. Differing risk factors for vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-sensitive enterococcal bacteraemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 388–394. [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, M.A. and Riley, L.W., 2007. Does vancomycin prescribing intervention affect vancomycin-resistant enterococcus infection and colonization in hospitals? A systematic review. BMC infectious diseases, 7, pp.1-11.

- Carmeli, Y.; Samore, M.H.; Huskins, W.C. The Association Between Antecedent Vancomycin Treatment and Hospital-Acquired Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 2461–2468. [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N.N.; DePestel, D.D.; Fohl, A.L.; Eyler, R.; Carver, P.L. Risk Factors for Systemic Vancomycin Exposure Following Administration of Oral Vancomycin for the Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2015, 35, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.G. The Case for Vancomycin as the Preferred Drug for Treatment ofClostridium difficileInfection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1489–1492. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., Kotler, D.P., Schlievert, P.M. and Sordillo, E.M., 2010. Staphylococcal enterocolitis: forgotten but not gone? Digestive diseases and sciences, 55, pp.1200-1207.

- Laux, C.; Peschel, A.; Krismer, B. Staphylococcus aureus Colonization of the Human Nose and Interaction with Other Microbiome Members. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Krismer, B.; Weidenmaier, C.; Zipperer, A.; Peschel, A. The commensal lifestyle of Staphylococcus aureus and its interactions with the nasal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 675–687. [CrossRef]

- Guet-Revillet, H., Le Monnier, A., Breton, N., Descamps, P., Lecuyer, H., Alaabouche, I., Bureau, C., Nassif, X. and Zahar, J.R., 2012. Environmental contamination with extended-spectrum β-lactamases: is there any difference between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp? American journal of infection control, 40(9), pp.845-848.

- Puig-Asensio, M., Diekema, D.J., Boyken, L., Clore, G.S., Salinas, J.L. and Perencevich, E.N., 2020. Contamination of health-care workers’ hands with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species after routine patient care: a prospective observational study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 26(6), pp.760-766.

- Weber, A.; Neffe, L.; Thoma, N.; Aghdassi, S.; Denkel, L.; Maechler, F.; Behnke, M.; Häussler, S.; Gastmeier, P.; Kola, A. Analysis of transmission-related third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales by electronic data mining and core genome multi-locus sequence typing. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 140, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.T.; Nimmo, J.; Gregory, E.; Tiong, A.; De Almeida, M.; McAuliffe, G.N.; A Roberts, S. Predictors of hospital surface contamination with Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: patient and organism factors. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2014, 3, 5–5. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.T.; Rubin, J.; McAuliffe, G.N.; Peirano, G.; A Roberts, S.; Drinković, D.; Pitout, J.D. Differences in risk-factor profiles between patients with ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: a multicentre case-case comparison study. 2014, 3, 27–27. [CrossRef]

- Mäklin, T.; Thorpe, H.A.; Pöntinen, A.K.; Gladstone, R.A.; Shao, Y.; Pesonen, M.; McNally, A.; Johnsen, P.J.; Samuelsen, Ø.; Lawley, T.D.; et al. Strong pathogen competition in neonatal gut colonisation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, S.; Kim, S.; Carter, R.A.; Leiner, I.M.; Sušac, B.; Miller, L.; Kim, G.J.; Ling, L.; Pamer, E.G. Cooperating Commensals Restore Colonization Resistance to Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 592–602.e4. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, S.; Carter, R.; Ke, X.; Sušac, B.; Leiner, I.M.; Kim, G.J.; Miller, L.; Ling, L.; Manova, K.; Pamer, E.G. Distinct but Spatially Overlapping Intestinal Niches for Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium and Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005132. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, T.; Lellouche, J.; Nutman, A.; Temkin, E.; Frenk, S.; Harbarth, S.; Carevic, B.; Cohen-Percia, S.; Kariv, Y.; Fallach, N.; et al. The effect of prophylaxis with ertapenem versus cefuroxime/metronidazole on intestinal carriage of carbapenem-resistant or third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales after colorectal surgery. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1481–1487. [CrossRef]

- Hecker, M.T., Aron, D.C., Patel, N.P., Lehmann, M.K. and Donskey, C.J., 2003. Unnecessary use of antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: current patterns of misuse with an emphasis on the antianaerobic spectrum of activity. Archives of internal medicine, 163(8), pp.972-978.

- Moen, C.M.; Paramjothy, K.; Williamson, A.; Coleman, H.; Lou, X.; Smith, A.; Douglas, C.M. A systematic review of the role of penicillin versus penicillin plus metronidazole in the management of peritonsillar abscess. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2023, 137, 992–996. [CrossRef]

- Wikstén, J.E.; Pitkäranta, A.; Blomgren, K. Metronidazole in conjunction with penicillin neither prevents recurrence nor enhances recovery from peritonsillar abscess when compared with penicillin alone: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1681–1687. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.; Stankiewicz, N.; Sneddon, J.; Seaton, R.A.; Smith, A. Indications for the use of metronidazole in the treatment of non-periodontal dental infections: a systematic review. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022, 4, dlac072. [CrossRef]

- Vedamurthy, A.; Rajendran, I.; Manian, F. Things We Do for No Reason™: Routine Coverage of Anaerobes in Aspiration Pneumonia. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 15, 754–756. [CrossRef]

- Bai, A.D., Srivastava, S., Digby, G.C., Girard, V., Razak, F. and Verma, A.A., 2024. Anaerobic Antibiotic Coverage in Aspiration Pneumonia and the Associated Benefits and Harms: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Chest.

- Strohäker, J.; Wiegand, L.; Beltzer, C.; Königsrainer, A.; Ladurner, R.; Meier, A. Clinical Presentation and Incidence of Anaerobic Bacteria in Surgically Treated Biliary Tract Infections and Cholecystitis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 71. [CrossRef]

- Trienski, T.L.P.; Bhanot, N.M. Double Anaerobic Coverage—A Call for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pr. 2022, 30. [CrossRef]

- Rattanaumpawan, P.; Morales, K.H.; Binkley, S.; Synnestvedt, M.; Weiner, M.G.; Gasink, L.B.; Fishman, N.O.; Lautenbach, E. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship programme changes on unnecessary double anaerobic coverage therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 2655–2658. [CrossRef]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Stafylaki, D.; Kasimati, A. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of clinically significant Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria in a Greek tertiary-care hospital, 2017–2019. Anaerobe 2020, 64, 102245. [CrossRef]

- Brook, I., 2007. Treatment of anaerobic infection. Expert review of anti-infective therapy, 5(6), pp.991-1006.

- Brook, I. Spectrum and treatment of anaerobic infections. J. Infect. Chemother. 2015, 22, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.; Cani, E.; Zeana, C.; Lois, W.; Park, T.E. Clinical Outcomes of Single Versus Double Anaerobic Coverage for Intra-abdominal Infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pr. 2022, 30. [CrossRef]

- Heath, D.M.; Boyer, B.J.; Ghali, A.N.B.; Momtaz, D.A.B.; Nagel, S.C.B.; Brady, C.I. Use of Clindamycin for Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection Decreases Amputation Rate. J. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 36, 327–331. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bryant, A.E.; Hackett, S.P. Antibiotic Effects on Bacterial Viability, Toxin Production, and Host Response. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, S154–S157. [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, F.; Zürcher, C.; Tarnutzer, A.; Schilcher, K.; Neff, A.; Keller, N.; Maggio, E.M.; Poyart, C.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Clindamycin Affects Group AStreptococcusVirulence Factors and Improves Clinical Outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 215, 269–277. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.L., 1999. The flesh-eating bacterium: what’s next? The Journal of infectious diseases, 179(Supplement_2), pp. S366-S374.

- Stevens, D.L., 1997. Necrotizing clostridial soft tissue infections. In The Clostridia (pp. 141-151). Academic Press.

- Raja, N.S. Oral treatment options for patients with urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum βeta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2019, 12, 843–846. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.A.; Schoch, P.E.; Hage, J.R. Nitrofurantoin: Preferred Empiric Therapy for Community-Acquired Lower Urinary Tract Infections. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 1243–1244. [CrossRef]

- Meena, S., Sood, S., Dhawan, B., Das, B.K. and Kapil, A., 2017. Revisiting nitrofurantoin for vancomycin resistant enterococci. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 11(6), p. DC19.

- Vervoort, J.; Xavier, B.B.; Stewardson, A.; Coenen, S.; Godycki-Cwirko, M.; Adriaenssens, N.; Kowalczyk, A.; Lammens, C.; Harbarth, S.; Goossens, H.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of the impact of nitrofurantoin treatment on the human faecal microbiota. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1989–1992. [CrossRef]

- Stewardson, A.; Gaïa, N.; François, P.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Delémont, C.; de Tejada, B.M.; Schrenzel, J.; Harbarth, S.; Lazarevic, V. Collateral damage from oral ciprofloxacin versus nitrofurantoin in outpatients with urinary tract infections: a culture-free analysis of gut microbiota. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 21, 344.e1–344.e11. [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S.; Henderson, I.R.; Capon, R.J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline as of December 2022. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 431–473. [CrossRef]

- Uilmann, U. Bacteriological studies with cefsulodin (CGP 7174/E), the first antipseadomonal cephalosporin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1979, 5, 563–567. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N.; Falkiner, F.R.; Keane, C.T.; Murphy, M.; Fitzgerald, M.X. The in-vitro activity of three anti-pseudomonal cephalosporins against isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1981, 8, 175–178. [CrossRef]

- Theodosiou, A.A.; Jones, C.E.; Read, R.C.; Bogaert, D. Microbiotoxicity: antibiotic usage and its unintended harm to the microbiome. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 36, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.; Nath, G.; Bhargava, A.; Aseri, G.K.; Jain, N. Phage therapeutics: from promises to practices and prospectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 9047–9067. [CrossRef]

- Behrens, H.M.; Six, A.; Walker, D.; Kleanthous, C. The therapeutic potential of bacteriocins as protein antibiotics. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2017, 1, 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Dickey, S.W.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Otto, M. Different drugs for bad bugs: antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 457–471. [CrossRef]

- Theuretzbacher, U.; Outterson, K.; Engel, A.; Karlén, A. The global preclinical antibacterial pipeline. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 18, 275–285. [CrossRef]

- Donskey, C.J. Fluoroquinolone restriction to control fluoroquinolone-resistant Clostridium difficile. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 353–354. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, O., Rosendal, K., Bülow, P., Faber, V. and Eriksen, K.R., 1969. Changing staphylococci and staphylococcal infections: a ten-year study of bacteria and cases of bacteremia. New England Journal of Medicine, 281(12), pp.627-635.

- Reynolds, L.A. and Tansey, E.M., 2008. Superbugs and Superdrugs: A history of MRSA. Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).