Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Indicators of Hospital Activity

2.2. Antimicrobial Consumption Trends in the Period 2017-2021

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Setting and Study Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Statistics Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241509763 (accessed on May 19, 2024).

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance. (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- World Health Organization. GLASS | Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) report. https://www.who.int/glass/resources/publications/early-implementation-report-2017-2018/en/. (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- CDC 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report Available online:. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html (accessed on May 21, 2024).

- Hassoun, N.; Kassem, I.I.; Hamze, M.; El Tom, J.; Papon, N.; Osman, M. Antifungal Use and Resistance in a Lower–Middle-Income Country: The Case of Lebanon. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Association of Infectology. Guide for the implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at a Hospital Level. Asociación Panamericana de Infectología: https://www.apiinfectologia.org/guia-para-la-implementacion-del-proa-a-nivel-hospitalario/. 2020.

- How to measure and monitor antimicrobial consumption and resistance. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica 2013, 31, 16–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondevilla, E.; Grau, S.; Echeverría-Esnal, D.; Gudiol, F.; Group, on behalf of the Vinc.P. Antibiotic consumption trends among acute care hospitals in Catalonia (2008–2016): impact of different adjustments on the results. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health- World Health Organization. ATCDDD - ATC/DDD Index. https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/. 19 May 2024.

- Gutiérrez-Urbón, J.M.; Gil-Navarro, M.V.; Moreno-Ramos, F.; Núñez-Núñez, M.; Paño-Pardo, J.R.; Periáñez-Párraga, L. Indicators of the hospital use of antimicrobial agents based on consumption. Farm. Hosp.

- National Institute of Statistic and Census-INEC. Total population of Costa Rica. https://inec.cr/noticias/poblacion-total-costa-rica-5-044-197-personas (accessed on 19 May 2024 ).

- The National Health System in Costa Rica. Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social: https://www.binasss.sa.cr/opacms/media/digitales/El%20Sistema%20nacional%20de%20salud%20en%20Costa%20Rica.%20Generalidades.pdf. (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Pan American Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines 2021. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/22a-lista-modelo-oms-medicamentos-esenciales-ingles. (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Official List of Medicines- CCSS. https://www.ccss.sa.cr/flip/lom/#pag/1. (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- National action plan to fight antimicrobial resistance 2018-2025. Ministry of Health-Costa Rica 2018. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/biblioteca-de-archivos-left/documentos-ministerio-de-salud/vigilancia-de-la-salud/normas-protocolos-guias-y-lineamientos/resistencia-a-los-antimicrobianos/1861-plan-de-accion-nacional-de-lucha-contra-la-resistencia-a-los-antimicrobianos-costa-rica-2018-2025/file. (accessed 20 May 2024).

- Marin, G.H.; Giangreco, L.; Dorati, C.; Mordujovich, P.; Boni, S.; Mantilla-Ponte, H.; Alfonso Arvez, Ma.J.; López Peña, M.; Aldunate González, Ma.F.; Ching Fung, S.M.; et al. Antimicrobial Consumption in Latin American Countries: First Steps of a Long Road Ahead. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221082346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado Borrell, R.; Losa García, J.E.; Alba Álvaro, E.; Toro Chico, P.; Moreno, L.; Pérez Encinas, M. Evaluación del consumo de antimicrobianos mediante DDD/100 estancias versus DDD/100 altas en la implantación de un Programa de Optimización del Uso de Antimicrobianos. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2015, 28, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kuster, S.P.; Ruef, C.; Ledergerber, B.; Hintermann, A.; Deplazes, C.; Neuber, L.; Weber, R. Quantitative Antibiotic Use in Hospitals: Comparison of Measurements, Literature Review, and Recommendations for a Standard of Reporting. Infection 2008, 36, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.M. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Appropriate Measures and Metrics to Study their Impact. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2014, 6, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filius, P.M.G.; Liem, T.B.Y.; van der Linden, P.D.; Janknegt, R.; Natsch, S.; Vulto, A.G.; Verbrugh, H.A. An additional measure for quantifying antibiotic use in hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 55, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2022. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240062702. (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Ajulo, S.; Awosile, B. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS 2022): Investigating the relationship between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption data across the participating countries. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0297921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-antimicrobial-consumption-europe-2022. (accessed on 2014 June 15).

- Miranda-Novales, M.G.; Flores-Moreno, K.; López-Vidal, Y.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, M.; Solórzano-Santos, F.; Soto-Hernández, J.L.; Ponce de León-Rosales, S.; Miranda-Novales, M.G.; Flores-Moreno, K.; López-Vidal, Y.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic consumption in Mexican hospitals. Salud Pública México 2020, 62, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenxuan Cao, Hu Feng, Yongheng Ma, et al. Long-term trend of antibiotic use at public health care institutions in northwest China, 2012–20 —— a case study of Gansu Province. BMC Public Health (2023) 23:27.

- Government of Canada. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) Report 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-system-report-2022.html. (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Lopez, M.; Martinez, A.; Celis Bustos, Y.; Thekkur, P.; Nair, D.; Verdonck, K.; Perez, F. Antibiotic consumption in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Colombia: national surveillance from 2018–2020. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2023, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolović, D.; Drakul, D.; Vujić-Aleksić, V.; Joksimović, B.; Marić, S.; Nežić, L. Antibiotic consumption and antimicrobial resistance in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A single-center experience. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau, S.; Fondevilla, E.; Echeverría-Esnal, D.; Alcorta, A.; Limon, E.; Gudiol, F. Widespread increase of empirical carbapenem use in acute care hospitals in Catalonia, Spain. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica 2019, 37, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, B.E.; Mercado, E.H.; Pinedo-Bardales, M.; Hinostroza, N.; Campos, F.; Chaparro, E.; Del Águila, O.; Castillo, M.E.; Saenz, A.; Reyes, I.; et al. Increase of Macrolide-Resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae Strains After the Introduction of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Lima, Peru. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 866186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R. Emergence of resistant Candida auris. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, V.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Secaira, C.; Torrez, J.C.T.; Lessa, F.C.; Patel, T.S.; Quiros, R. Antimicrobial stewardship in Latin America: Past, present, and future. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | Year | % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2021 | |||

| DDD | 622.94 | 890.74 | 0.43 | 0.0004 |

| Bed days | 14478.46 | 12555.54 | -0.13 | 0.0010 |

| Discharges | 2011.75 | 1702.83 | -0.15 | 0.0004 |

| Length of stay | 7.33 | 7.48 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

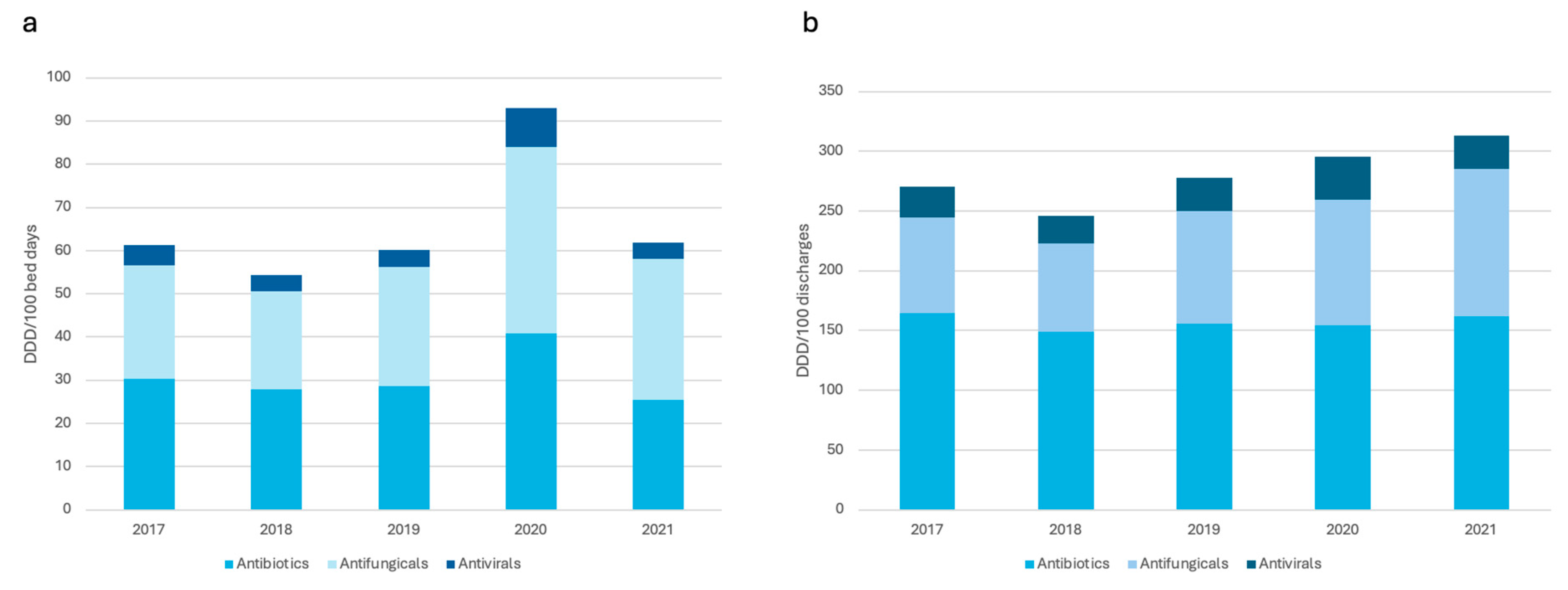

| Total | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | % increase | Trend | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total antimicrobials (J01, J02, J05) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 61.35 | 54.30 | 60.13 | 93.05 | 61.78 | 0.70 | 3.96 | 0.31 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 270.63 | 245.68 | 277.80 | 295.44 | 313.25 | 15.75 | 13.50 | 0.0007 |

| Total antibiotics (J01) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 30.36 | 27.92 | 28.67 | 40.86 | 25.51 | -15.97 | 0.32 | 0.84 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 164.29 | 149.18 | 155.53 | 154.64 | 161.92 | -1.44 | 0.072 | 0.96 |

| Total antifungicals (J02) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 26.30 | 22.68 | 27.60 | 43.21 | 32.49 | 23.53 | 3.29 | 0.05 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 80.41 | 73.59 | 94.49 | 104.61 | 123.52 | 53.61 | 11.72 | <0.0001 |

| Total antivirals (J05) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 4.69 | 3.70 | 3.87 | 8.98 | 3.77 | -19.61 | - 0.34 | 0.57 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 25.93 | 22.91 | 27.78 | 36.19 | 27.81 | 7.25 | 1.70 | 0.14 |

| Total | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | % | Trend | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracyclines (J01A) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 15.14 | 13.83 | 12.72 | 16.86 | 13.78 | -8.98 | 0.031 | 0.94 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 88.75 | 93.84 | 91.26 | 91.37 | 88.57 | -0.20 | -0.28 | 0.63 |

| Penicillins (J01C) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 264.03 | 218.55 | 233.13 | 339.47 | 221.26 | -16.20 | 3.53 | 0.80 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 1390.00 | 1165.89 | 1212.08 | 1278.22 | 1344.66 | -3,26 | 2.16 | 0.93 |

| Cephalosporis (J01D) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 430.66 | 405.92 | 369.09 | 485.73 | 296.08 | -31.24 | -18.93 | 0.29 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 2495.15 | 2313.39 | 2239.63 | 1999.53 | 1946.72 | -21.97 | -141.07 | <0.0001 |

| Carbapenems, monobactams (J01DH, J01DF) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 146.13 | 147.72 | 172.54 | 260.09 | 156.77 | 7.28 | 13.36 | 0.27 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 699.00 | 644.69 | 791.78 | 793.57 | 948.00 | 35.62 | 64.68 | <0.0001 |

| Marcolides, lincosamides (J01F) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 50.42 | 61.99 | 44.17 | 46.65 | 25.39 | -49.64 | -6.54 | 0.005 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 360.60 | 347.88 | 305.84 | 240.73 | 174.26 | -51.67 | -47.98 | <0.0001 |

| Sulfonamides and trimethoprim (J01E) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 74.42 | 77.82 | 100.60 | 176.83 | 107.19 | -44.03 | 16.45 | 0.06 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 475.60 | 515.66 | 616.71 | 780.73 | 772.85 | 62.50 | 85.95 | <0.0001 |

| Aminoglycosides (J01G) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 69.62 | 56.59 | 63.76 | 88.93 | 71.01 | 1.99 | 3.51 | 0.24 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 339.28 | 258.60 | 307.13 | 277.29 | 419.03 | 23.50 | 17.81 | 0.26 |

| Quinolones (J01M) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 68.01 | 56.02 | 59.38 | 113.04 | 84.09 | 23.64 | 8.91 | 0.08 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 389.65 | 332.23 | 329.36 | 424.43 | 527.55 | 35.39 | 36.80 | 0.02 |

| Other antibacterias (J01XA01): Vancomycin | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 176.02 | 166.40 | 181.72 | 241.48 | 139.66 | -20.65 | 0.23 | 0.98 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 814.88 | 773.91 | 820.56 | 809.67 | 878.52 | 7.80 | 16.30 | 0.03 |

| Other antibacterias (J01XX08): Linezolid | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 46.41 | 28.18 | 47.76 | 76.56 | 34.61 | -25.42 | 2.47 | 0.62 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 175.82 | 121.69 | 185.60 | 190.10 | 202.50 | 15.17 | 12.17 | 0.08 |

| Azole Antifungicals (J02AB, J02AC) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 116.52 | 105.78 | 124.21 | 179.35 | 163.64 | 40.43 | 16.78 | 0.0008 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 647.18 | 599.22 | 778.78 | 822.70 | 1045.72 | 61.58 | 102.05 | <0.0001 |

| Echinocandins Antifungicals (J02AX) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 41.26 | 30.28 | 41.36 | 79.92 | 31.33 | -24.06 | 2.97 | 0.59 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 156.94 | 136.72 | 166.16 | 223.39 | 189.48 | 20.73 | 15.17 | 0.01 |

| Antivirals (J05A) | ||||||||

| DDD/100 bed days | 23.45 | 18.49 | 19.34 | 44.88 | 18.86 | -19.57 | 1.72 | 0.57 |

| DDD/100 discharges | 25.93 | 22.91 | 27.78 | 38.19 | 27.81 | 7.25 | 1.70 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).