1. Introduction and Scientific Goals

Understanding the mechanisms behind technological evolution is a central challenge in technology analysis, particularly in markets characterized by rapid change and increasing complexity. Studies show that technologies do not evolve in isolation; rather, they interact within systems composed of interrelated components, each contributing to the overall functionality and performance of the host technology (Coccia, 2018; Coccia and Watts, 2020; Utterback et al., 2019). This study addresses two fundamental research questions:

How does the microevolution of embedded technological subsystems drive the macroevolution of host technological systems?

What are the temporal patterns and statistical relationships between subsystem advancements and the innovation trajectory, performance, and pricing of technologies?

These questions are critical for clarifying the mechanisms through which technological evolution supports the strategic management for competitive advantage of firms (Basalla, 1988; Porter, 1980). Technological development is shaped by both “technical choices” which reflect economic, social, and political factors, and “technical requirements,” which are imposed by material properties (Hosler, 1994, p. 3; cf. Magee, 2012). Arthur (2009, pp. 18–19) states that technologies emerge as fresh combinations of existing components, organized into systems with hierarchical and recursive structures.

In this context, Sahal (1981) emphasizes that technological evolution pertains to the structure and function of the object system, governed by internal dynamics and equilibrium processes (pp. 64–69). Evolution is driven by both major and minor innovations, problem driven, that interact within complex technological systems (Barton, 2014; Coccia, 2017; 2019; Dosi, 1988). Arthur (2009, p. 15ff) identifies the explanation of technological evolution as one of the most important problems in the field. Various theories in economics and management attempt to explain technological evolution, including models of competitive substitution, where new technologies replace older ones (Fisher & Pry, 1971; Sahal, 1981; Coccia, 2019a). However, despite extensive literature, a significant gap remains in understanding how subsystems interact with host technologies to drive systemic innovation. Specifically, there is limited research on how embedded subsystems—such as connectivity modules, display technologies, or energy systems—co-evolve with the main technological system, influencing its trajectory in markets and socioeconomic systems.

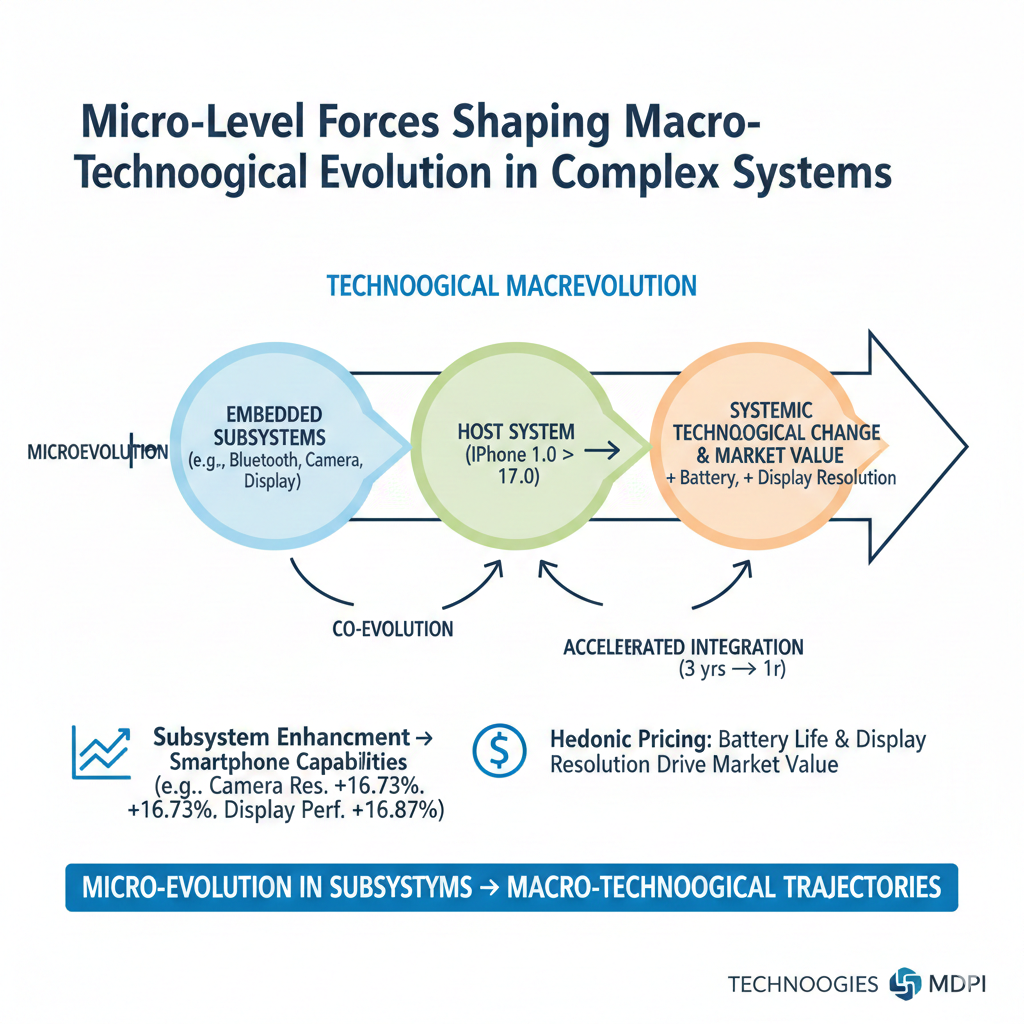

Addressing this gap, the present study develops a theory of macroevolution in technological systems driven by the evolution of their embedded subsystems. This approach extends existing theories of technological change by introducing new dimensions of interaction and co-evolution. The conceptual framework is grounded in Generalized Darwinism (Hodgson & Knudsen, 2006), which views technological evolution as a process of variation, selection, and retention within complex systems.

The scientific inquiry endeavors to support the hypothesis that microevolution in subsystems drives macroevolution in host technologies. To validate this theory, the study employs a case study research of iPhone technology from 2007 to 2025, examining its relationship with Bluetooth and other parasitic subsystems. The iPhone serves as a host technology, integrating successive versions of Bluetooth (2.0 to 6.0), which precede and enable macroevolutionary advances in smartphone models (cf., Coccia, 2019, 2019b).

This study contributes to innovation theory by proposing a systemic model of technological evolution, where subsystems act as drivers of macro-level change. It integrates insights from evolutionary economics, systems theory, and technology management, offering a more understanding of how technologies evolve through internal interactions and external pressures.

For managers and innovation strategists, the findings can offer actionable insights. Firms can enhance product evolution by investing in high-impact subsystems, such as battery life or display resolution in smartphone technology. Monitoring subsystem trends enables better forecasting of market shifts and consumer expectations. Moreover, hedonic pricing models, used in this study, can inform pricing strategies by quantifying the value contribution of specific subsystems. This approach supports co-evolution of product and process families with effective modular design strategies, agile R&D planning, and long-term innovation road mapping. Overall, than, this study advances the understanding of technological evolution by highlighting the role of embedded subsystems in shaping the trajectory of host (principal) technologies. It bridges a critical gap in the literature and provides both theoretical depth and practical relevance for scholars, R&D managers and analysts in innovation management.

2. Theoretical Framework

Firstly, it is important to clarify the concept of complex system to support theoretical framework here. Simon (1962, p. 468) states that: “a complex system [is]… one made up of a large number of parts that interact in a nonsimple way …. complexity frequently takes the form of hierarchy, and …. a hierarchic system … is composed of interrelated subsystems, each of the latter being, in turn, hierarchic in structure until we reach some lowest level of elementary subsystem.” McNerney et al. (2011, p. 9008) argue that: “The technology can be decomposed into n components, each of which interacts with a cluster of d − 1 other components”. Technology is defined here as a complex system that is composed of more than one component and a relationship that holds between each component and at least one other element in the system (Coccia, 2019). A technology interacts in a system with other inter-related technologies to achieve goals, satisfy needs and/or solve problems or more broadly to serve a human purpose or multiple purposes (Coccia and Watts, 2020). In this context, Sahal (1981) points out that systems innovations are due to integration of two or more symbiotic technologies. The analogy between biological and technological evolution has generated a substantial body of literature (Arthur, 2009; Basalla, 1988; Wagner & Rosen, 2014; Ziman, 2000). Recent literature challenges the traditional view that technological evolution is driven solely by competitive substitution. Utterback et al. (2019) propose abandoning this zero-sum perspective, introducing the concept of symbiotic competition, where the growth of one technology stimulates the development of interrelated technologies. Technologies, therefore, evolve not only through rivalry but also through mutual reinforcement, forming complex ecosystems of innovation (Coccia, 2019). Pistorius and Utterback (1997) further argue that multi-mode interactions between technologies offer a richer framework for analyzing technological change, especially in fast-moving markets. These interactions mirror biological evolution, where species co-adapt and evolve together. Sandén and Hillman (2011) categorize technological interactions into six types: neutralism, commensalism, amensalism, symbiosis, competition, and parasitism. These categories, borrowed from ecology, help explain how technologies influence each other’s evolution. Coccia (2019) applies this framework, showing that interactions often begin as parasitic but evolve toward mutualism and symbiosis over time. This dynamic is evident in the relationship between Bluetooth technology and smartphones. Moreover, this body of work highlights that parasite technologies (subsystems)—such as connectivity modules, sensors, etc.—can significantly influence the macroevolution of host technologies (Coccia and Watts, 2020). Macroevolution is essentially the long-term outcome of microevolutionary dynamics. This conceptual continuity is central to evolutionary biology and can also be applied to technological evolution (Coccia, 2019).

The biological analogy is supported by a rich body of literature. Alphey et al. (2020) describe evolutionary drives at the genetic level, such as mutational and reparational pressures, which influence the direction and rate of change. Mutations, while random in their phenotypic impact, are influenced by molecular structure, replication dynamics, and environmental factors. Similarly, technological subsystems evolve under constraints imposed by material properties, user demands, and systemic compatibility (Magee, 2012). Moreover, macroevolutionary patterns—such as rates of species diversification—are influenced by ecological and demographic factors that are difficult to model (Erwin & Krakauer, 2004; Schuster, 2016). In technology, similar challenges arise. While subsystem improvements can forecast host system evolution, external factors such as market dynamics, regulatory environments, and user behavior also play critical roles (Coccia, 2019b).

Technological evolution, like biological evolution, exhibits patterns of radiation, stasis, extinction, and novelty (Andriani & Cohen, 2013; Valverde et al., 2007; Solé et al., 2013). Subsystems may undergo rapid innovation (radiation), periods of incremental change (stasis), become obsolete (extinction), or introduce entirely new capabilities (novelty). These patterns are observable in the evolution of smartphone components, where certain technologies (e.g., physical keyboards) have disappeared, while others (e.g., facial recognition) have emerged as novel features and support macroevolution of these devices.

The integration of subsystem evolution into host technologies is not merely additive but transformative. As subsystems improve, they redefine the capabilities and user experience of the host system. For instance, advancements in display technology—from LCD to OLED to high-refresh-rate panels—have not only improved visual quality but also enabled new applications such as gaming. Similarly, battery improvements have extended device usage, enabling more complex and power-intensive functionalities (Watanabe et al., 2009; Coccia, 2018a).

Understanding these dynamics is essential for both theorists and managers, as it enables better forecasting of technological trends and strategic planning for innovation dynamics in ecosystems. This perspective opens new avenues for research and managerial practice, emphasizing the importance of subsystem evolution in shaping the future of complex technological systems.

3. Materials and Methods

The main goal of this study is to clarify how the microevolution of embedded technological subsystems drives the macroevolution of host technological systems, offering a new perspective on innovation and technological development. The theoretical foundation of this study is rooted in the concept of Generalized Darwinism, which extends Darwinian principles—variation, selection, and retention—beyond biological evolution to explain change in complex systems such as technologies, organizations, and economies (Hodgson & Knudsen, 2006). Hodgson (2002, p. 260) defines Darwinism as a general theory applicable to all open, complex systems. This framework of Generalized Darwinism and evolutionary ecology provides a powerful lens for analyzing how technological systems evolve through the interaction and transformation of their embedded subsystems for a comprehensive understanding of technological change in modern markets.

3.1. Conceptual Structure of Proposed Theory

The following premises support the proposed theory here:

- a)

Technology T is a complex system that is composed of more than one entity or sub-technological systems t

i (t

1, t

2, …, t

i, … t

n) and a relationship that holds between each entity and at least one other entity in the system to satisfy a need, solve a problem, or more broadly to serve a human purpose (or multiple purposes). The behavior and evolution of any technology is dependent from the behavior and evolution of inter-related technologies (Coccia, 2019, 2019a, 2019b).

- b)

Evolution of a technological sub-system t is a consequential modification and/or improvement δ of technology t over time concerning its performance and/or efficiency.

Temporal evolution of technology

t is:

t = technological sub-system

t1 = technological evolution of t

t2 = technological evolution of t1, etc.

δt= modification and/or improvement of technology t

Evolution of technology Δ can be at different scale. If technology t is a sub-system or element of a main-host technology T , technological change and improvement of t is a MICROevolution in T; Technological change and improvement of T is a MACROevolution.

We suggest a simple mechanism to link technological evolution at micro- and macro scale. Some basic concepts structure the theoretical framework.

Let Let ΔT=Macroevolution of the technological system T

Let Δt=Microevolution of the sub-system t

Let Postulates

- −

Microevolutionary scale of technological subsystems is linked to the macroevolution of its technological system.

- −

Microevolutionary drives are basic for macroevolution of technological systems

- −

Macroevolution of technology is a multi-dimensional change of its sub-systems:

- −

Macroevolution of technological systems =f(microevolutionary drives of subsystems)

Predictions of theory of microevolutionary drives in the macroevolution of technological systems

Some testable implications of the theory are:

Let κ= chronological or sequential time, κ-1 is a previous period of time

Macroevolution of technological system ΔTκ at the time κ is the addition microevolution of technological sub-systems ti(κ-1) developed in a previous period κ-1. In addition, macroevolution of technological system is a temporal dynamics (growth, development and change) based on coevolution of technologies at different scale in a process of reciprocal adaptations to be more functional and efficient to satisfy changing needs and/or solve consequential problems of adopters (Coccia, 2017).

3.2. Case Study

The predictions of proposed theory is verified, initially, with a case study research based on Bluetooth technology as one of the technological subsystems of smartphone. The narrative approach is applied to analyze the link between evolution of a sub-system (microevolution) and an inter-related technological system to clarify pattern of macroevolution over time. Narratives connect past, present, and future, enabling us to understand innovation as a temporal journey rather than a mere chronology (Ricoeur, 1984). In particular, the temporal dimension is captured by chronos, the linear unfolding of events, and kairos, the opportune moment for change (Garud et al., 2010). Future technological trajectories are often shaped by projective narratives rooted in the past (Garud et al., 2010).

In the case study here the sub-system under study is Bluetooth technology, whereas the interrelated technological system is the iPhone. Bluetooth short-range wireless technology is introduced in 1998. This technology enables two information technology devices (e.g., such as wireless headphones, keyboards, mouse, speakers to PCs, gaming console and mobile device) to connect directly without a network infrastructure, such as a wireless router (Bluetooth, 2025; Intel, 2025). Bluetooth technology operates on radio frequencies in the 2.4 GHz range and has two current Bluetooth standards currently:

- −

Bluetooth Classic supports basic rate and enhanced data rate.

- −

Bluetooth Low Energy is a version that optimizes power consumption of battery in host devices, such as smartphone. It supports higher audio quality and more diverse listening options than Bluetooth Classic.

Initially, host devices (i.e., PCs) needed external dongles to connect to Bluetooth peripherals, by USB port. Since 2011, Intel corporate has included integrated Bluetooth functionality in Wi-Fi. Now Information Technology devices have networking cards with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth functionality for improved performance and coordination across both radio capabilities.

About the iPhone, under study here, is a line of smartphones originated by R&D investments in Apple (an American multinational corporation and technology company) that run operating system iOS. The first-generation of the iPhone was presented in 2007 and introduced in worldwide markets in 2008. Apple has developed this innovative products and every years has launched new iPhone models and iOS versions (Verizon, 2025). The innovative iPhone was the first mobile phone with multi-touch technology. Technological evolution is directed to higher-resolution displays, video-recording functionality, waterproofing, high-tech camera, Face ID facial recognition. New advanced models in 2025 include Apple Intelligence, A18prochip with 6-core CPU, camera control, 48MP fusion camera, 5x telephoto camera, visual intelligence, more than 32 hours video playback, etc. (Apple, 2025). Since the first iPhone in 2007, it supported Bluetooth technology version 2.0. In 2014, iPhone 6 introduces Bluetooth Low Energy. Apple company has developed an innovation ecosystem of Bluetooth accessories that seamlessly integrate with the iPhone, such as AirPods, Air Tags, Apple Watch, etc. Apple (2025) continually improves iPhone Bluetooth technology with each iOS updates, to improve audio quality, and new features are the "Find My » application to locate compatible Bluetooth devices (Levesque, 2023).The evolution of iPhone Bluetooth technology shows how Apple’s innovation is transforming the interaction between wireless devices. Future technological developments are directed to higher integration with a perspective of coevolution of inter-related wireless technology, such as improvements of Wi-Fi connectivity and a new wireless technology of the Ultra-Wideband.

Now, the goal is to explain the link between evolution of Bluetooth technological (as a sub-system), other technological sub-systems and iPhone (technological system), in a perspective of host-parasite interaction (Coccia and Watts, 2020). This inductive analysis can clarify the link between evolution of a sub-system (microevolution) and an inter-related host technological system to clarify pattern of macroevolution over time.

3.3. Data Sources and Data Analysis Procedure

Firstly, these case studies are narrated mainly by using the use of secondary data that play more and more a vital role in scientific research (Kozinets, 2002). Secondary data of cases study here are investigated in terms of chronological events for the development of innovative technological applications of Bluetooth technology considering chronos and kairos aspects (Garud et al., 2010). Following Ansari et al. (2016), a narrative for technology analysis of cases study is based on a range of secondary data sources given by different articles in relevant journals, by identifying the chronologies of major events and dates of occurrence. In particular, data from these different sources of journals, in a historical perspective, are described in narrative and represented with a chronological events, from which intertwined past, present, and future notions are analyzed to suggest general prepositions of technological evolution.

The first data that are analyzed are about evolution of Bluetooth technology from the Classic Bluetooth versions (1.0-3.0) to Bluetooth low energy versions (4.0-5.4) and future directions (MOKOSmart, 2024). The second data analyzed are the evolution of different models of iPhone from the first model having OS1.0 announced in January 2007 to iPhone 17 having IOS 18.3, announced on 9 September, 2025 (Everyi.com, 2025). The chronological technological analysis considers which iPhone models support specific versions of Bluetooth technology (Everyi.com, 2025). Other data analyzed are camera characteristics (SANDMARC-California 2025), screen resolutions and sizes (Appmysite, 2025) and battery technology (UGREEN, 2021; Apple, 2025) embodied in different versions of iPhone models. This study also considers the price of iPhone that includes the value of technological evolution. Data of price are from (CNET, 2025). The goal is to explain the link between temporal microevolution of technological subsystems underlying a technological systems as a whole (iPhone in this case) in a perspective to host-parasite interaction (Coccia and Watts, 2019).

Secondly, in order to detect the evolution of specific technological subsystems in smartphone, the arithmetic and exponential rates of growth are calculated (i=1, …, n).

Let Technological characteristics (TC) over 2007-2025, in particular,

TCi 2007= level of technological subsystem i in 2007

TCi 2025= level of technological subsystem i in 2025

If the development of technological subsystem i is assumed to be of arithmetic type, the rate of growth is given by:

If the development of technological subsystem is assumed to be of exponential type, the exponential rate of growth is given by:

= rate of exponential growth of technological subsystem i

Thirdly the pattens of temporal change are analyzed with Pearson bivariate correlation with test of significance with one-tailed. This analysis supports the next analysis about the estimation of the parameters in a relationship between variables under study with the following linear model of regression to assess the temporal evolution of technological subsystems into the host-system. The model considers the time as dependent variables to analyze statistically the trends represented graphically. The basic model is:

y = technological evolution of subsystems

time= explanatory variable

α = constant

β = coefficient of regression

u = error term

ln= logarithm with base e = 2.718281828

Finally, the hedonic pricing method offers a valuable analytical approach for understanding the relationship between technological characteristics and market valuation, integrating both economic and technical dimensions (Saviotti, 1985). In innovation studies, it serves to detect and quantify technical changes that enhance product performance (Triplett, 1985). The core assumption of the hedonic approach is that a product’s market price reflects the value of its individual attributes. By quantifying the contribution of each subsystem to product value, the hedonic model reveals how subsystem innovations drive macroevolutionary shifts in technological systems. It thus supports a novel perspective on innovation dynamics, showing how the evolution of parts shapes the trajectory of the whole. Thus, the hedonic method offers a dynamic perspective on innovation, showing how subsystem-level changes shape broader technological transformation. Variables under study are:

- −

Price P of iPhone (current U$) sold from 2007 to 2025. This measure of price is consistent with a stable inflation during the period under study.

- −

The evolution of smartphone technology is measured with Technological characteristics (FMT) of subsystems over 2007-2025 (cf., Sahal, 1981, pp. 27-29). FMTs in iPhone used here are given by:

- −

Wide Camera Resolution (megapixel, Mpix, refers to a unit of measurement equal to one million pixels, used to describe the resolution and detail of digital images and camera sensors)

- −

Display resolution in ppi, measures the pixel density of a screen, indicating the number of individual pixels packed into each inch of the display. A higher ppi means more pixels, which results in sharper, more detailed, and smoother images and text on the screen.

- −

Battery h of video playback (hours).

This study considers a log-log model of hedonic pricing, in which iPhone prices are regressed with respect to technological characteristics of subsystems. The specification of log-log model (considering data in natural logarithms) is the following equation:

a0= constant

ai= coefficient of regression (i=1,2,3)

A t-test is performed for each coefficient in the hedonic price equation. Standardized values of the coefficients of regression ai provide information about the most important technological subsystems driving the macro technological evolution of the host system of a given product (iPhone here) over time. This study also applies an alternative model in which iPhone version are regressed with respect to technological characteristics of subsystems for a comparative analysis with previous model.

4. Results

This study focuses on Bluetooth technology that is considered a parasitic technology (Coccia and Watts, 2019; 2020) acting as sub-system for manifolds technologies, such as smartphone, speakers, smartwatch, etc. Bluetooth version 1.0 is introduced in July 1999 as wireless communication between mobile and computing devices. In 2004 it is released Bluetooth 2.0 with the EDR (Enhanced Data Rate) technology that increased the data transfer rates up to 3 Mbps and bandwidth to the transfer of large files. The technological and user utility of Bluetooth technology has emerged with the invention and introduction in market of the radical innovation of the iPhone in 2007 that has generated a market shift in information and communication technologies (iPhone, 2025). The first generation 1.0 of iPhone model is designed to support Bluetooth 2.0 with the EDR. In the technological system of iPhone, Bluetooth technology is a main technological sub-system supporting the evolution of overall host technology. A main assumption in our theory is that Macroevolution of technological system =f(evolution of its subsystems). In the context of these technologies given by Bluetooth as a parasite sub-system of main host technologies, the observation is that the technological evolution of Bluetooth technology 2.0 in 2004 has supported the innovation of technological system in iPhone 1.0 (year 2007). Initially temporal lag between the evolution of this parasite technology and the introduction in the main host technology given by iPhone is 3 years. As a consequence the evolution of technological subsystem (Bluetooth 2.0), temporally antecedent , is supporting the evolution of the host system in which it is embedded for the macroevolution of technological system (iPhone). This technological regularity is also for the next versions of Bluetooth (parasitic sub-system) and iPhone technology (host technological systems), i.e., evolution in sub-systems (called here microevolution) drives the macroevolution of the host technological systems. In fact, Bluetooth 4.0 is presented in 2009 having a comprehensive multiple-mode integration of classic Bluetooth, high speed, and the innovative Bluetooth low energy extension. This technological advancement (evolution) in Bluetooth 4.0 contributes to technological advancement (macroevolution) of the new iPhone model 5.0 in 2011 that combines this new technology in its technological system and other families of Apple products (Bryan et al., 2007). Hence the evolution of Bluetooth technology (in 2009), as parasitic sub-system, contributes, after 2 years, to the macroevolution of its host system in 2011. The combined process between sub-systems and macrosystem continues over time: Bluetooth 5.0 is released in 2016, improving the message capacity to 255 bytes – 8 times more than Bluetooth 4.2 and the rate of data transfer that achieves 2 Mbps in low power mode, twice the earlier rates. In addition, the communication range is about 300m. New iPhone version 8.0 in 2017, as host system, implements Bluetooth 5.0, after one year. Instead, Bluetooth 5.3 is introduced in 2021 having main advances in transmission efficiency, improved interference resistance, and battery life. Other incremental innovations are encryption key size control, periodic advertising and channel classification enhancements. The evolution in this sub-system in 2021 supports the macroevolution of the host technological system iPhone 14 model in 2022. Bluetooth 6.0, launched in September 2024, boosts precision with centimeter-level distance tracking, smarter ad filtering, and improved device monitoring. It enhances audio with lower latency, strengthens security, and optimizes power management for longer battery life—delivering faster, more reliable, and energy-efficient wireless connectivity. New version of iPhone 17, released in September 2025, introduces this Bluetooth 6.0 with a time delay of 1 year, contributing to the incremental macroevolution in the host system of smartphone. These interrelationships between evolution in parasitic subsystem and macroevolution of the host system is presented in

Table 1. In short, evolution in sub-systems is a driver of the evolution of host-macrosystems. Moreover, the time lag from evolution of the sub-system and its implementation in host technological macrosystem has reduced from 3 year to 1 year, suggesting an acceleration process of the evolution of technological macrosystems, driven by the evolution of this and other sub-systems.

4.1. Pattens of Temporal Technological Evolution

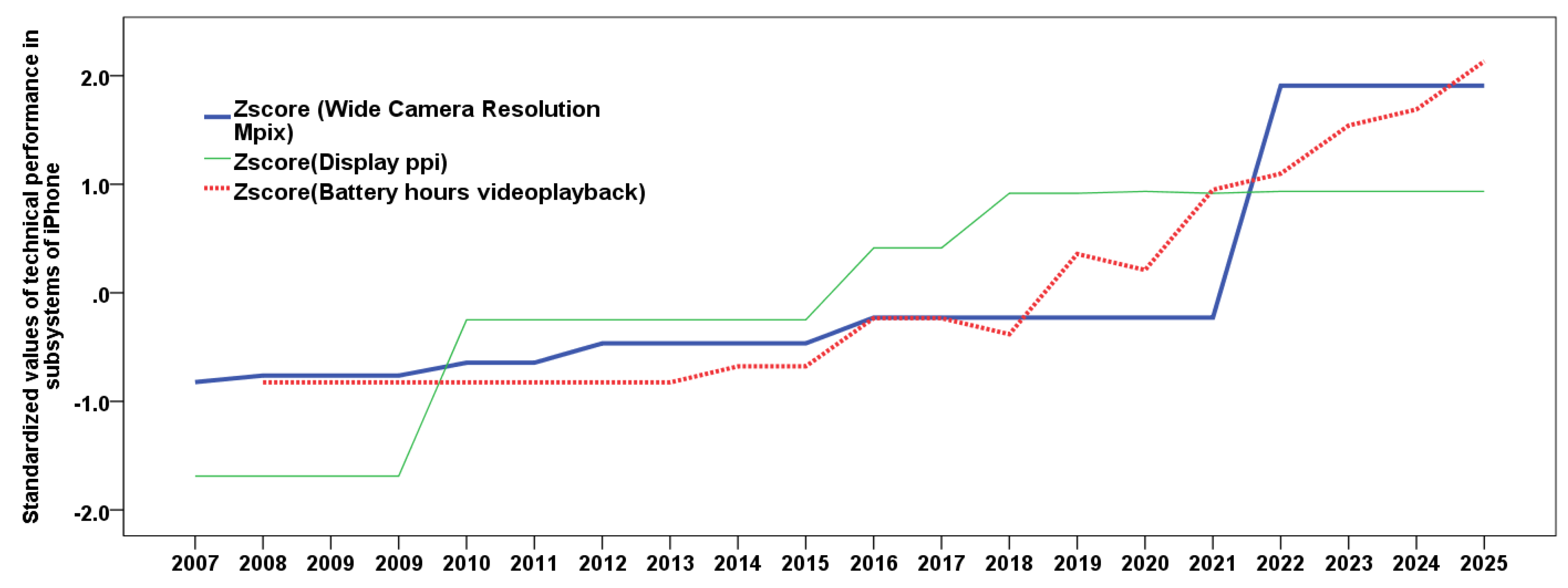

Figure 1 shows the evolutionary dynamics of main technological sub-systems included in the iPhone over 2007-2025. Graphical representation shows the increasing technical performance and quality of two main technological sub-systems supporting the macroevolution of new versions in iPhone technology: higher Mpixel in wide camera resolution and hours of video playback in battery.

Table 2 shows the rate of growth in technological characteristics of these sub-systems incorporated into iPhone technology that indicates their contribution to technological macroevolution. According to the arithmetic and exponential rates of growth over time, higher technological advances that support the macroevolution of the iPhone are due to the sub-systems of wide camera resolution (exponential rate of growth r exp =16.73%, 2007-2025), hours of battery for video playback (r exp =5.78%, 2007-2025), and finally display ppi (exponential rate of growth r exp =5.46%, 2007-2025).

The results are also supported by statistical analyses of regression models having time as explanatory variable (

Table 3). In fact, parametric estimates of the linear model as function of time in

Table 3 show that the highest temporal growth is by Wide Camera Resolution Mpix (b=0.16, p-value 0.001), whereas Display ppi and Battery (h, video playback) have a similar temporal growth of about b=0.06 (p-value 0.001). The coefficient R

2 is high and explains about 90% of the variance in the data for the model having as response variable Camera Resolution Mpix and Battery (h, video playback), whereas regression models explain more than 74% of the variance in the data for response variables of Display ppi as function of time. The F test has a significance of the p-value<0.001.

4.2. Pattens of Morphological Technological Change

Bivariate correlation in

Table 4 shows that iPhone Models has a high significant correlation at the 0.01 level with Wide Camera Resolution (r=92) , Display ppi (r=89) and Battery h video playback (r=93). Similarly, U

$ price of iPhone models has a high significant correlation at the 0.01 level with Wide Camera Resolution (r=90) , Display ppi (r=79) and Battery hour video playback (r=93), respectively. This result show a main association of the macroevolution of the system of iPhone technology with main embedded sub-systems.

Table 5 shows that the evolutionary pathways of the iPhone technology based on main embedded sub-systems in order to show what are the main sub-systems driving the macroevolution of the overall host system. If the hedonic price method is applied, results suggest that main drivers of the evolution of iPhone technology are, in average, given by increasing hours of battery for playback as suggested by standardized coefficients of regression b= 0.77, having also a significant b=0.29 (p-value 0.01) and by increasing ppi in Display (ppi=pixels, which results in sharper, more detailed, and smoother images and text on the screen) with std. b=0.15. In this model 1, a 1% higher level of technology performance in battery the expected price of iPhone by about 0.3% (p-value<.01). Moreover, regression model 1 explains more than 85% of the variance in the data and the F test has a significance of the p-value<0.001. Model 2 uses increasing versions of iPhone from 2007 to 2025 and confirms basic results. Findings also suggest that main drivers of the evolution of iPhone technology are given by increasing hours of battery for video playback as suggested by standardized coefficients of regression b= 0.58, also having a significant coefficient of regression b=0.88 (p-value=0.001) and by increasing ppi in Display with std. b=0.44 and a significant coefficient of regression b=0.73 (p-value 0.001). Regression model 2 has a goodness of fit very high with a coefficient of determination R2 adj. =97% and the F test (the ratio of the variance explained by the model to the unexplained variance) has a significance of the p-value<0.001.

This empirical evidence can be systematized in logical manner as follows:

In synthesis, these results of inductive analysis can be generalized suggesting that macroevolution of the overall system is driven by evolution of basic embedded sub-systems as emerged in the iPhone technology, in which main sub-systems support technical macroevolution of iPhone technology, such as higher technological performance in Bluetooth with case study research and Display with higher ppi and battery with higher hours for video playback in statistical analysis.

5. Discussion

5.1. Explanation of Results in Reference to Previous Literature

This conceptual framework and empirical investigation reveals a dynamic interplay between host technologies and their embedded subsystems directed to technological micro-macroevolution between subsystems and main host system (Coccia, 2019; Coccia and Watts, 2020). The evolution of the iPhone, under study here, is a main case study, illustrating how incremental advancements in subsystems—such as Bluetooth, camera resolution, display quality, and battery life—collectively drive and shape the evolutionary trajectory of the overarching technology. The temporal alignment between successive Bluetooth versions and iPhone models suggests a pattern of accelerating integration and co-evolution, where subsystem innovations increasingly precede and enable evolution of host technology. Results in

Table 1 shows a decreasing lag between subsystem development and host adoption, highlighting a shift toward tighter coevolutionary coupling, driven by learning processes for an accelerated pathway of evolution (Bryan et al., 2007). In this context, the strong statistical associations observed in

Table 3 between subsystem improvements and iPhone model progression underscore the significance of micro-level changes. For instance, enhancements in camera resolution, display pixel density, and battery performance exhibit robust correlations with the evolution of iPhone generations (

Table 3). These relationships are further substantiated by hedonic pricing models, which demonstrate that attributes like battery life and display resolution are not only key determinants of consumer value but also pivotal drivers of macro-technological innovation in main host system (cf. Coccia, 2018). In particular, Coccia (2018a) applies hedonic pricing to identify the technical features most influential in smartphone evolution. The findings here extend this approach by demonstrating that battery life and display resolution are not only significant in pricing but also serve as proxies for technological advancement. Moreover, the explanatory power of these models in

Table 5 reinforces the notion that subsystem evolution is central to the functional macro evolution of host technologies.

This empirical evidence also aligns with Sahal’s (1981) theoretical framework, which posits that technological evolution unfolds through a process of equilibrium shaped by internal system dynamics. Sahal’s view of stepwise development, where major innovations emerge from the cumulative effect of minor ones, finds resonance in the study’s demonstration of how subsystem innovations catalyze macro-level transformation. The increasing integration between Bluetooth and iPhone technologies exemplifies Sahal’s emphasis on systemic cohesion, particularly in the transition from loosely coupled components to symbiotic relationships and by Coccia (2019, 2019a) of symbiotic interaction between technologies that support coevolutionary processes. Moreover, the analogy of technological parasitism by Coccia and Watts (2020), inspired by evolutionary ecology, offers a rich conceptual lens for interpreting these dynamics. Drawing from the work by Poulin (2006), the evolution of Bluetooth from a parasitic to a symbiotic subsystem mirrors biological coevolution, where the fitness of the parasite becomes intertwined with the host’s success. This framework is further supported by Coccia (2019a), who argues that host technologies embedded with numerous parasitic subsystems tend to evolve more rapidly. This study exemplifies this principle, showing how the proliferation and refinement of subsystems accelerate the pace of host innovation.

The concept of System Generation Engineering, as articulated by Pfaff et al. (2023), provides additional context for understanding innovation within the iPhone lineage. Their work suggests that successful innovation often arises from strategic variation rather than radical redesign. This study complements this view by showing that subsystem evolution enables such strategic variation, reinforcing the idea that innovation is cumulative and context-sensitive. The study here also draws a parallel with recent discussions in evolutionary biology, particularly the “paradox of predictability” explored by Tsuboi et al. (2024). This paradox highlights how microevolutionary variation can forecast macroevolutionary divergence. The technological analogy demonstrates that standing variation in subsystems—such as successive Bluetooth versions—can indeed predict broader evolutionary outcomes in host technologies like the iPhone. Taken together, this study offers an extension of evolutionary theory by integrating concepts of technological parasitism and symbiosis into a systemic model of innovation. In fact, the conceptualization of Bluetooth as a parasitic technology embedded within host systems such as smartphones, smartwatches, and speakers is well-grounded in the theory of technological parasitism developed by Coccia and Watts (2020). This framework posits that parasitic technologies, while initially dependent on host systems, can evolve toward mutualistic or symbiotic relationships, ultimately accelerating the evolution of the host. The empirical timeline in

Table 1 —from Bluetooth 2.0 supporting iPhone 1.0 to Bluetooth 6.0 integrated into iPhone 17—illustrates this evolutionary process, where subsystem innovation precedes and enables host system macroevolution. In addition, the identification here from case study research of a shrinking time lag between subsystem innovation and host system adoption is consistent with models of technological evolution that incorporate time-delay dynamics. Georgalis and Aifantis (2013) explore how time delays—akin to biological maturation periods—affect the stability and growth of emerging technologies. Their adaptation of logistic growth models with delay parameters provides a mathematical foundation for the empirical observation: as subsystem technologies mature faster and are adopted more rapidly, the host systems evolve more efficiently and predictably. This concept is further supported by integrated approaches to mapping technology evolution paths, which highlight the importance of synchronizing scientific and technological developments to forecast innovation trends. The convergence of subsystem and host evolution is seen as a key factor in identifying future opportunities and guiding strategic innovation and R&D strategy, suggesting that identifying subsystems with high evolutionary potential can inform investment and design decisions (Coccia et al., 2024; Coccia and Roshani, 2024).

5.2. Theoretical and Technological Management Implications

The theoretical framework and empirical analyses presented in this study advance the understanding of technological change as an evolutionary process characterized by the following properties:

- −

Coevolution: Subsystems and host technologies evolve in tandem, with increasing integration and mutual dependence, forming a dynamic technological ecosystem.

- −

Acceleration: The pace of macroevolution intensifies as subsystem innovations become more frequent and impactful, reducing integration lags and accelerating systemic advancement.

- −

Predictability: Standing variation in subsystems (e.g., successive Bluetooth versions) provides a basis for forecasting host system capabilities and long-term technological trajectories.

- −

Symbiosis: Initially parasitic technologies evolve toward symbiotic roles, enhancing the adaptability and performance of host systems, driven by microevolutionary mechanisms that underpin macroevolution in technological systems.

These properties align with broader evolutionary theories in technology studies, including patterns of technological innovation described by Sahal (1981) and Coccia (2019, 2019a). The findings can be generalized across diverse technological systems, demonstrating that embedded subsystem evolution is a critical driver of macro-level technological change. This coevolutionary dynamic—marked by decreasing time lags and increasing symbiotic integration—suggests a fundamental principle: innovations in subsystems often precede and enable evolutionary transformations in complex technological systems.

For innovation management, these findings offer actionable insights for designing technological strategies in fast-moving markets. From an ambidextrous strategy perspective, firms should balance exploration of emerging subsystem innovations (e.g., Bluetooth advancements) with exploitation of existing host technologies. This dual approach enables organizations to sustain competitive advantage by leveraging incremental subsystem improvements to enhance current offerings while preparing for disruptive changes (Coccia, 2024, 2025). Recognizing the accelerating integration between subsystems and host systems allows managers to optimize R&D resource allocation, shorten development cycles, and align product roadmaps with evolving technological ecosystems (Daim et al., 2018). Furthermore, systematic tracking of subsystem advancements enables researchers and industry leaders to anticipate innovation trajectories, convergence patterns, and coevolutionary dynamics, thereby optimizing R&D investments and designing adaptive, future-ready technologies across markets (Kauffman and Macready, 1995).

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This study addresses a central challenge in innovation research: understanding how technologies evolve within rapidly changing environments. By adopting a systemic perspective, it proposes that technological macroevolution is driven by the microevolution of embedded subsystems. Using the iPhone and Bluetooth technologies as a case study, the research demonstrates how successive Bluetooth versions have consistently preceded and enabled macroevolution and advances in performance of iPhone models. The decreasing time lag between subsystem innovation and host system integration—from three to one year—indicates an accelerating coevolutionary process. Statistical analyses reveal strong correlations between iPhone evolution and improvements in subsystems such as camera resolution, display quality, and battery life. Regression and hedonic pricing models confirm that these subsystems significantly influence both technological capabilities and market value. The findings suggest that subsystem innovations are not merely supportive but are central drivers of host technology macroevolution. This conceptual framework extends existing theories of technological change by highlighting the evolutionary interdependence between subsystems and host systems. It also introduces new insights into how learning processes and subsystem enhancements shape the trajectory of complex technologies. Overall, the study argues that macroevolution in technological systems is fundamentally dependent on the progressive microevolution of their interrelated and embedded subsystems.

Main lessons learned from the study are:

- −

Subsystem Innovation Drives Systemic Evolution: The evolution of embedded technologies like Bluetooth plays a foundational role in shaping the trajectory of host systems such as the iPhone. Micro-level advancements in data transfer, energy efficiency, and connectivity consistently precede and enable macro-level innovation.

- −

Technological Coevolution Accelerates Over Time: The decreasing time lag between subsystem development and host system integration—from three years to one—reveals a pattern of accelerating coevolution. This suggests that technological ecosystems are becoming more tightly coupled and responsive to subsystem changes.

- −

Subsystems Influence Market and Functional Value: Improvements in subsystems such as camera resolution, display quality, and battery life are strongly correlated with both technological capabilities and pricing of host devices. These components are not peripheral but central to innovation and consumer valuation.

Key theoretical implications derived from the study are the critical role of subsystem-driven macroevolution. The study reinforces the idea that technological macroevolution is not solely the result of radical innovations in host systems, but is significantly shaped by the cumulative microevolution of embedded subsystems. This challenges linear models of innovation and supports a systemic, layered view of technological change. Moreover, underlying technological evolution there is a main mechanism of technological parasitism and symbiosis (Coccia and Watts, 2020). By conceptualizing technologies like Bluetooth as parasitic subsystems that evolve toward symbiosis, the study extends evolutionary theory in technology. It introduces a framework where subsystem-host relationships evolve dynamically, influencing innovation speed, integration, and system complexity. In addition the technology analysis shows some main temporal dynamics in innovation ecosystems: The decreasing time lag between subsystem innovation and host system adoption suggests an acceleration in coevolutionary processes. This implies that innovation ecosystems are becoming more synchronized, and that subsystem maturity can serve as a predictive indicator of host system evolution—offering a new lens for forecasting technological trajectories.

Considering this case study research and results of the statistical analysis, best practices for strategic management of innovation development based on the study’s results can be to adopt ambidextrous innovation strategies: a balance exploration of emerging subsystems with exploitation of existing host technologies. This dual approach allows firms to remain agile, leveraging incremental innovations to enhance current products while preparing for disruptive shifts in the technological landscape.

Overall, then, this study addresses a significant gap in the literature on technological innovation: the lack of a systemic framework explaining how technologies evolve through the interaction of embedded subsystems within host systems. By introducing the proposed theory of macroevolution driven by subsystem microevolution, this research offers a novel perspective that captures the complexity and interdependence of technological ecosystems (Coccia, 2019). The case study of the iPhone and Bluetooth technologies demonstrates how subsystem advancements precede and enable host system evolution, with decreasing time lags indicating accelerated coevolution. These findings are important because they provide empirical evidence for a layered model of technological change, where subsystem innovation acts as a predictive and driving force in families of technologies. This has implications for forecasting innovation, guiding R&D investment, and refining theories of technological evolution. The study also highlights the role of learning processes and integration dynamics in shaping technological macroevolution, offering a more vital understanding of how technologies adapt and evolve in fast-changing markets.

6.1. Limitations and Development of Future Research

These conclusions are, of course, tentative. This study provides some interesting but preliminary results in these complex fields. Although this study is offering a novel framework for understanding technological macroevolution through subsystem microevolution, presents some limitations that open avenues for future research. First, the analysis is based on a single case study—the iPhone and Bluetooth technologies—which may limit generalizability across other technological domains. Future research should apply this framework to diverse host technologies (e.g., electric vehicles, smart homes, medical devices) to validate and refine the theory. Second, the study focuses primarily on quantitative indicators such as resolution, battery life, and pricing. A broader set of qualitative factors—such as user experience, design integration, and ecosystem compatibility—could enrich the understanding of subsystem influence. Future studies could explore how subsystem-host relationships evolve in open versus closed innovation environments, and how organizational strategies (e.g., modular design, platform thinking, Bryan et al., 2007) mediate these dynamics. Finally, longitudinal studies incorporating real-time data and machine learning models could enhance predictive capabilities, helping firms anticipate subsystem-driven innovation trends. Overall, expanding the scope, metrics, and theoretical depth of this research will strengthen its relevance for innovation theory and strategic technology management.

To conclude, the proposed approach retains strong explanatory power in identifying how specific technological characteristics—particularly those of embedded subsystems—support the macroevolutionary pathways of complex technologies such as smartphones. This study’s originality lies in its integration of evolutionary theory, subsystem analysis, and empirical modeling to explain how technologies evolve not in isolation, but through dynamic interactions within broader systems. As a consequence, this study contributes original insights to the literature by advancing a systemic theory of technological macroevolution driven by the microevolution of subsystems.

This conceptual framework lays the groundwork for more sophisticated models in technology analysis and forecasting, particularly in turbulent markets. By demonstrating that subsystem evolution can predict and shape the evolution of host technologies, the study offers a new perspective for anticipating innovation patterns and guiding strategic R&D investments. Moreover, these findings here can encourage further theoretical exploration in the terra incognita of the interaction between subsystem of parasitic-symbiotic technologies and main host technologies for improving the prediction of evolutionary pathways and supporting R&D investments towards new technologies and innovations having a high potential of growth and of impact on the socioeconomic system. Yet, identifying critical mechanisms in evolutionary pathways of technologies remains a complex task. Technological systems are influenced by diverse, context-dependent factors that vary across time, space, and domains. As Wright (1997, p. 1562) aptly notes, “In the world of technological change, bounded rationality is the rule.” This underscores the need for flexible, systemic approaches that account for interdependencies between different inter-related technological systems to clarify emergent dynamics in technological evolution.

Author Contributions

Mario Coccia has done: Conceptualization.; methodology.; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; visualization; supervision; project administration.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alphey, LS; Crisanti, A; Randazzo, FF; Akbari, OS. Opinion: Standardizing the definition of gene drive. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117(49), 30864–30867. [Google Scholar]

- Andriani, P.; Cohen, J. From exaptation to radical niche construction in biological and technological complex systems. Complexity 2013, vol. 18(n. 5), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.S.; Garud, R.; Kumaraswamy, A. The disruptor’s dilemma: TiVo and the U.S. Television ecosystem. Strategic Management Journal 2016, 37(9), 1829–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple. iPhone. 2025. Available online: https://www.apple.com/iphone/.

- Apple 2025. iPhone. Available online: https://www.apple.com/it/?afid=p240%7Cgo~cmp-213292967~adg-13999330967~ad-733796428214_kwd-49065841~dev-c~ext-~prd-~mca-~nt-search&cid=aos-it-kwgo-brand-- (accessed on June 2025).

- Appmysite. The complete guide to iPhone screen resolutions and sizes (Updated 2025). 2025. Available online: https://www.appmysite.com/blog/the-complete-guide-to-iphone-screen-resolutions-and-sizes/.

- Arthur, B. W. The Nature of Technology. What it is and How it Evolves; Allen Lane–Penguin Books: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, C. M. Complexity, Social Complexity, and Modeling. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2014, 21(2), 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalla, G. The History of Technology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bluetooth 2025. Bluetooth technology. Available online: https://www.bluetooth.com/.

- Bryan, A.; Ko, J.; Hu, S.J.; Koren, Y. Co-evolution of product families and assembly systems. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 56(1), 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNET. Apple event-Tech-Mobile. iPhone Prices (Patrick Holland). 2025. Available online: https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/i-studied-iphone-prices-going-back-to-2007-tariff-or-not-were-due-for-a-price-hike/.

- Coccia, M. A Theory of classification and evolution of technologies within a Generalized Darwinism. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2019, vol. 31(n. 5), 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Watts, J. A theory of the evolution of technology: technological parasitism and the implications for innovation management. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 2020, vol. 55, n. 101552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Destructive Creation of New Invasive Technologies: Generative Artificial Intelligence Behaviour. Technologies 2025, vol. 13(no. 7), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daim, T. U.; Byung-Sun, Y; Lindenberg, J.; Grizzi, R.; Estep, J.; Oliver, T. Strategic roadmapping of robotics technologies for the power industry: A multicriteria technology assessment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2018, vol. 131, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, G. Sources, Procedures, and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation. Journal of Economic Literature 1988, 26(3), 1120–1171. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2726526.

- Erwin, D. H.; Krakauer, D. C. Evolution. Insights into innovation. Science 2004, 304(5674), 1117–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everyi.com. iPhone Q&A, Does the iPhone support Bluetooth? Which iPhone models support which versions of Bluetooth? 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J. C.; Pry, R. H. A Simple Substitution Model of Technological Change. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 1971, vol. 3(n. 2-3), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Dunbar, R. L. M.; Bartel, C. A. Dealing with Unusual Experiences: A Narrative Perspective on Organizational Learning. Organization Science 2010, 22, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgalis, Evangelos E.; Aifantis, Elias C. Introducing time delay in the evolution of new technology: the case study of nanotechnology. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Materials 2013, vol. 22(no. 5-6), 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G. M. Darwinism in economics: from analogy to ontology. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 2002, vol. 12, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G. M.; Knudsen, T. Why we need a generalized Darwinism, and why generalized Darwinism is not enough. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 2006, 61(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosler, D. The Sounds and Colors of Power: The Sacred Metallurgical Technology of Ancient West Mexico; MIT Press: Cambridge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Intel. What Is Bluetooth® Technology? 2025. Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/products/docs/wireless/what-is-bluetooth.html.

- Kauffman, S.; Macready, W. Technological evolution and adaptive organizations: Ideas from biology may find applications in economics. Complexity 1995, 1(2), 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. The field behind the screen: using ethnography for marketing research in online communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39(1), 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, M. TECHBROWSER. The Evolution of iPhone Bluetooth Technology: A Timeline. 2023. Available online: https://techbrowser.co/apple/iphone/evolution-iphone-bluetooth-timeline/#the-expanding-iphone-bluetooth-ecosystem.

- Levit, G.; Hossfeld, U.; Witt, U. Can Darwinism be “Generalized” and of what use would this be? Journal of 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, C.L. Towards quantification of the role of materials innovation in overall technological development. Complexity 2012, 18(1), 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, J.; Farmer, J. D.; Redner, S.; Trancik, J. E. Role of design complexity in technology improvement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108(22), 9008–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Comprehensive Guide on Different Bluetooth Versions. 2024. Available online: https://www.mokosmart.com/guide-on-different-bluetooth-versions/.

- Pfaff, F.; Götz, G. T.; Rapp, S.; Albers, A. Evolutionary perspective on system generation engineering by the example of the iPhone. Proceedings of the Design Society ICED23 2023, vol. 3, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius, C.W.I.; Utterback, J.M. Multi-mode interaction among technologies. Research Policy 1997, 26(1), 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive strategy; Free Press: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin, R. Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P. Time and narrative; Blamey, K.; Pellauer, D., Translators; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sahal, D. Patterns of Technological Innovation; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.: Reading, Massachusetts, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sandén, B. A.; Hillman, K. M. A framework for analysis of multi-mode interaction among technologies with examples from the history of alternative transport fuels in Sweden. Research Policy 2011, vol. 40(n. 3), 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANDMARC-California 2025. How has the iPhone Camera Evolved? Available online: https://www.sandmarc.com/blogs/articles/how-has-the-iphone-camera-evolved?srsltid=AfmBOorw3Qv2Is5OAYBYokjkhTbRpBkb53dFE7_ubioFQnvRhqaeFW2y.

- Saviotti, P. An Approach to the Measurement of Technology Based on the Hedonic Price Method and Related Methods. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 1985, vol. 27(n. 2-3), 309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, P. Major Transitions in Evolution and in Technology. Complexity 2016, 21(4), 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. The architecture of complexity. Proceeding of the American Philosophical Society 1962, 106(6), 476–482. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, R. V.; Valverde, S.; Casals, M. R.; Kauffman, S. A.; Farmer, D.; Eldredge, N. The Evolutionary Ecology of Technological Innovations. Complexity 2013, 18(4), 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, J. E. Measuring technological change with characteristics-space techniques. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 1985, vol. 27(n. 2–3), 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi, M.; Sztepanacz, Jacqueline; De Lisle, Stephen; Voje, Kjetil L; Grabowski, Mark; Hopkins, Melanie J; Porto, Arthur; Balk, Meghan; Pontarp, Mikael; Rossoni, Daniela; Hildesheim, Laura S; Horta-Lacueva, Quentin J-B; Hohmann, Niklas; Holstad, Agnes; Lürig, Moritz; Milocco, Lisandro; Nilén, Sofie; Passarotto, Arianna; Svensson, Erik I; Villegas, Cristina; Winslott, Erica; Hsiang Liow, Lee; Hunt, Gene; Love, Alan C; Houle, David. The paradox of predictability provides a bridge between micro- and macroevolution. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2024, 37(Issue 12), 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Evolution of the iPhone Battery and Charging Tech. 2021. Available online: https://blog.ugreen.com/the-iphone-battery-charger/ (accessed on June 2025).

- Utterback, J. M.; Pistorius, Calie; Yilmaz, Erdem. The Dynamics of Competition and of the Diffusion of Innovations. In MIT Sloan School Working Paper; 2019; pp. 5519–18. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/117544.

- Valverde, S.; Solé, R.V.; Bedau, M.A.; Packard, N. Topology and evolution of technology innovation networks. Physical Review. E, Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2007, vol. 76 n. 5 Pt 2, pp. 056118-1-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A timeline: Notable milestones in the history of iPhone from Apple. 2025. Available online: https://www.verizon.com/articles/Smartphones/milestones-in-history-of-apple-iphone/.

- Wagner, A.; Rosen, W. Spaces of the possible: universal Darwinism and the wall between technological and biological innovation. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 2014, 11(97), 20131190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, C.; Moriyama, K.; Shin, J. Functionality development dynamism in a diffusion trajectory: a case of Japan’s mobile phones development. Technol. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 2009, 76(6), 737–753. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G. Towards A More Historical Approach to Technological Change. The Economic Journal 1997, vol. 107, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Technological innovation as an evolutionary process; Ziman, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |