1. Introduction

The Humboldt penguin (

Spheniscus humboldti), a species within the order Sphenisciformes and the family Spheniscidae, is distributed along the Pacific coasts of Peru and Chile, ranging from La Foca Island (05°12′ S, 81°12′ W) to Guafo Island (43°32′ S, 74°42′ W) [

1]. The largest breeding colonies are in Chile [

9,

13]. The diet of this species consists primarily of fish, including anchovy (

Engraulis ringens), Araucanian herring (

Strangomera bentincki), silverside (

Odontesthes regia), common hake (

Merluccius gayi), Inca scad (

Trachurus murphyi), South American pilchard (

Sardinops sagax), and garfish (

Scomberesox saurus scombroides), as well as cephalopods and crustaceans, mainly malacostracans and isopods [

8].

Globally, the Humboldt penguin is classified as Vulnerable, with a declining population estimated at approximately 23,800 mature individuals, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [

1]. Approximately 80 breeding colonies have been reported throughout its distribution range, including 42 in Peru and 38 in Chile [

17]. The species is also listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). In Chile, the Humboldt penguin is likewise classified as Vulnerable, and its Recovery, Conservation, and Management Plan (RECOGE) identifies seven major threats: invasive exotic species, fisheries interactions, anthropogenic disturbance, harmful productive practices and civil works, human consumption, free-roaming dogs, and emerging diseases. These emerging diseases include ocular pathologies and highly pathogenic avian influenza [

12] (Decreto N°1, 25 July 2024, Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, Chile).

Despite the recognized impact of infectious diseases on this species, trematode-associated renal and ureteral damage has not previously been reported in Humboldt penguins. Our research group frequently observed this condition during necropsies performed between July and November 2025. Therefore, this study presents the first report of trematode infection associated with severe tubular, interstitial, and ureteral lesions, as well as marked renal fibrosis, in stranded Humboldt penguins along the Chilean coast during 2025.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stranding Records

The study included five Humboldt penguins (

Spheniscus humboldti) that stranded alive or dead along the Chilean coast in 2025. All animals were donated under official authorization issued by the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service (SERNAPESCA), Coquimbo, Chile. Recorded data included individual identification number, stranding condition (alive or dead), age category, sex, body condition score [

3], stranding date, date of death, and geographic location.

2.2. Necropsy and Histopathology

Necropsies were performed at the Laboratory of Veterinary Sciences Research (LiCiVet), Universidad del Alba, La Serena campus, Chile. A complete gross examination of all organs was conducted. Multiple representative tissue samples from different organs were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (DiaPath, Italy). Formalin-fixed tissues were submitted to the Veterinary Histopathology Center (VeHiCe), Puerto Montt, Chile, for routine histological processing. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), and Masson’s trichrome. Histological slides were subsequently digitized using a Motic Easy Scan system at magnifications of up to 80×.

2.3. Analysis and Identification of Parasitic Structures

Parasites were morphologically analyzed, and their distinct anatomical structures were identified [

6,

7,

14]. The developmental stage of the trematodes was evaluated based on morphological criteria and the presence of mature reproductive structures, including a uterus filled with eggs [

14]. Morphological and morphometric analyses were performed on adult parasites, including measurements of body length and width. In addition, eggs were quantified and measured within the uterus of individual adult trematodes. A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted, including mean values, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum measurements for both adult parasites and eggs, as well as egg counts per individual parasite [

14,

15].

3. Results

3.1. Stranding Records

Of the five Humboldt penguins analyzed, one stranded dead and four stranded alive between July and November 2025. Both adult and juvenile individuals were included, comprising males and females, with body condition scores ranging from emaciated to normal. The four live-stranded penguins were transferred to the Humboldt Conservation Rehabilitation Center, where they subsequently died of natural causes within 0–14 days post-admission (

Table 1).

3.2. Necropsy and Histopathology:

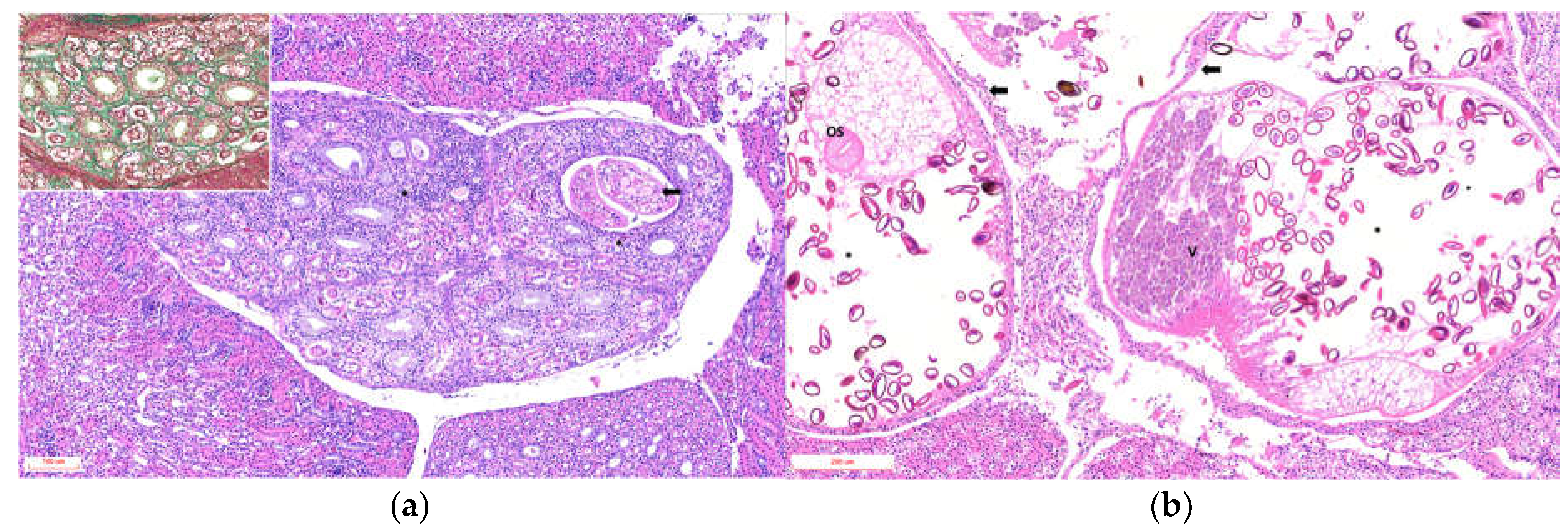

On gross examination, the kidneys (fresh tissue) from the animals exhibited marked vascular congestion with hyperemic vessels, whitish intratubular structures, and mucopurulent exudate, which were most evident in animal ID:1 (

Figure 1a). The renal pelvis was markedly distended and contained urate deposits; the ureters were dilated and showed pronounced wall thickening. During the selection of areas for microscopic analysis in animal ID:4, rounded blackish areas measuring up to 0.2 cm in diameter were observed, with a multifocal to coalescing distribution within the renal parenchyma (

Figure 1b). Animals ID:2, 3, and 4 exhibited serous atrophy of fat, with up to 15 mL of free translucent fluid in the pericardial sac (hydropericardium).

Histological analysis was performed on 5 penguins, and the finding summarized in Supplementary Table (Pathology). The main tubular lesions were characterized by degeneration of the epithelial cells of the collecting tubules, cystic dilatations containing one or two parasitic structures (

Figure 2a), and adult parasites with uteri containing variable numbers of eggs (

Figure 2b). Tubules containing urate crystals surrounded by lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with heterophils were observed in 3 of 5 animals. The interstitium exhibited moderate to marked diffuse fibrosis, with bands of mature collagenous tissue between tubular components (

Figure 2a, Inset). The vascular component was hyperemic and congested, with multiple hemorrhagic foci.

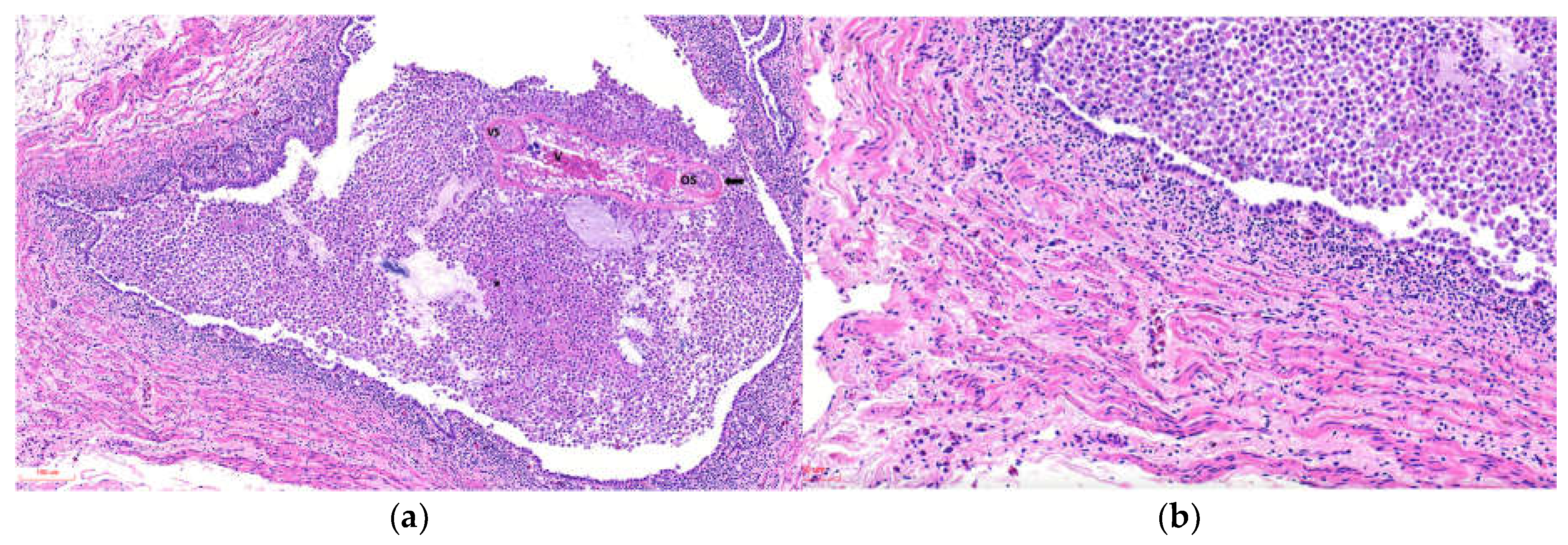

Glomeruli occasionally showed expansion of the urinary space with areas of increased cellularity. The ureters exhibited luminal dilation, epithelial hyperplasia, epithelial cell sloughing, squamous metaplasia, and necrosis, with multiple intraluminal parasitic structures surrounded by abundant macrophages, cellular debris, and heterophils in all cases, varying in severity (

Figure 3a). The smooth muscle tissue adjacent to the ureters showed variable damage, mainly degenerative and necrotic lesions of muscle fibers, with moderate mononuclear inflammation on a pale proteinaceous background and edema (

Figure 3b).

3.3. Analysis and Identification of Parasitic Structures

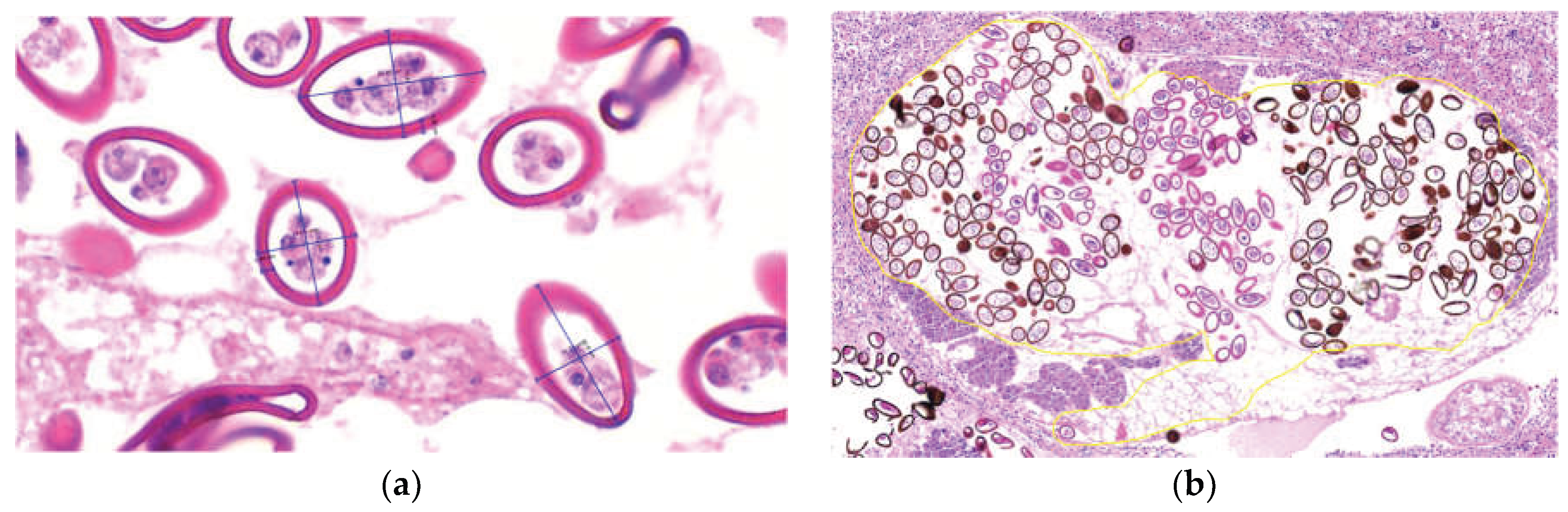

Morphologically, the parasites exhibited an eosinophilic tegument with abundant tegumentary spines, a clearly identifiable digestive tract, and reproductive structures including testes, uterus, and vitellaria, as well as a muscular pharynx and both oral and ventral suckers. Based on these features, the parasites were classified as trematodes. Parasites were observed at different developmental stages, in stages 3, 4, and 5, eggs were identified within the uterus, with or without visible miracidia. Adult parasites (n = 20) measured 1,175 ± 319.77 × 811.33 ± 303.70 µm (length × width; mean ± SD). Egg morphometric data are summarized in Supplementary Table (Eggs). Eggs within renal lesions (n = 583) measured 45.9 ± 8.51 × 26.14 ± 3.55 µm, with a capsular (opercular) thickness of 3.68 ± 0.60 µm (length × width × capsule thickness) (

Figure 4a). Egg counts were manually performed in the uterus of adult parasites located within the renal tubules. A total of 457 eggs were counted, with a mean of 201.55 ± 100.12 eggs per parasite (n = 33) (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

Renal trematodes affecting seabirds mainly belong to the genus

Renicola and are commonly associated with the consumption of bivalves, mollusks, and fish [

15]. Despite this well-recognized host–parasite relationship, reports of renal trematodiasis in free-ranging penguins remain scarce. Documented cases are limited to African penguins (

Spheniscus demersus) in South Africa [

10], Magellanic penguins (

Spheniscus magellanicus) in Brazil [

11], and little penguins (

Eudyptula novaehollandiae) and Fiordland crested penguins (

Eudyptes pachyrhynchus) in New Zealand [

14]. These studies indicate that lesion severity and distribution vary among penguin species. In

S. demersus,

Renicola soleni infection was associated with minimal gross and microscopic alterations [

10]. In contrast,

S. magellanicus exhibited microscopic lesions comparable to those observed in

S. humboldti in the present study, including tubular dilation, squamous metaplasia, epithelial hyperplasia, fibrosis, and interstitial inflammation [

11]. These findings suggest that trematode-associated renal pathology in penguins may present with variable severity, potentially influenced by parasite burden and host condition. Large numbers of renal trematodes have been reported to debilitate affected birds, contributing to mortality and potentially influencing stranding events [

5]. In the present cases, up to two parasites were observed within a single renal tubule.Increased parasitic burden in animals with poor body condition may exacerbate tissue damage due to an imbalance between host immune response and parasite virulence [

2,

4]. A similar pattern has been described in Atlantic puffins (

Fratercula arctica), in which severe trematode-associated nephropathy, ureteritis, and muscle and fat atrophy were reported in 96.3% of affected individuals [

16]. Regarding squamous metaplasia, although this lesion has been documented in birds and is commonly associated with hypovitaminosis A—which may have been present in emaciated animals (Animal IDs 2, 3, and 4)—the severity and distribution of the lesions observed in this study support a direct association with trematode-induced damage [

11]. Notably, the smooth muscle lesions observed in the ureters have not been previously reported in penguins and are likely related to the severity of the parasitic infection, potentially impairing ureteral function. Morphometric analyses demonstrated that adult parasites exhibited lengths comparable to those reported for other

Renicola species, as did egg dimensions [

11,

14,

15]. However, species-level identification using published taxonomic keys remains challenging due to the large number of eggs occupying the uterus of adult parasites, which limits the morphological assessment of diagnostic structures.

5. Conclusions

This study supports that stranding and mortality in Humboldt penguins are likely multifactorial processes, in which renal trematode infection may represent a contributing factor. The severity of renal and ureteral lesions observed suggests that trematodiasis should be considered within the context of emerging diseases affecting this species and may be relevant to conservation frameworks such as the national RECOGE plan. Morphological evaluation of adult parasites and eggs provides useful preliminary information for taxonomic assessment; however, definitive species identification requires molecular analyses, including PCR and sequencing. Such approaches are essential for accurate classification of these trematodes and for improving the understanding of their life cycle.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A-F.O.; methodology, C.A-F.O., J.P-R.; validation, C.S.; formal analysis, C.S.; investigation, G.C., S.M., T.P., M.S.; resources, G.C., S.M., T.P., M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A-F.O., J.P-R.; funding acquisition, C.A-F.O., C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad del Alba.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All analyses were performed under the authorization and supervision of SERNAPESCA, and within the framework of a collaboration agreement between the Regional Directorate of Coquimbo of SERNAPESCA and Universidad del Alba, La Serena campus, Exempt Resolution No. Coq-0061/2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to legal reasons and privacy regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service (SERNAPESCA), Coquimbo; the Director of the School of Veterinary Medicine, La Serena campus, Rubí Gatica; the Dean of Universidad del Alba, Dr. Cecilia Echeverría; and the Director General of Research and Innovation of Universidad del Alba, Dr. María Raquel Ibáñez, for their support and contribution to this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CITES |

Convention on International Trade

in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| RECOGE |

Recovery, Conservation, and Management

Plan |

References

- BirdLife International. 2020 Spheniscus humboldti. IUCN Red List Threat. Species 8235, e.T22697817A182714418.

- Bush, O; Fernández, J.C.; Esch, G.W; Seed, J.R. Parasitism: The Diversity and Ecology of Animal Parasites; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 0521662788. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.; Sanchez, J. N. Creation and validation of a novel body condition scoring method for the Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) in the zoo setting. Zoo Biology 2015, 34(6), 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornet, S.; Bichet, C.; Larcombe, S.; Faivre, B.; Sorci, G. Impact of host nutritional status on infection dynamics and parasite virulence in a bird-malaria system. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, D. E.; Kearns, M. P. Northern little blue penguin mortality in Northland. 1975, 22, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaktionov, K.; Solovyeva, A.; Miroliubov, A.; Regel, K.; Romanovich, A. Renicola spp. (Digenea, Renicolidae) of the “Duck Clade” with description of the Renicola mollisima Kulachova, 1957, Life Cycle. Diversity 2025, 17(8), 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneberg, P.; Sitko, J.; Bizos, J.; Horne, E. Central European parasitic flatworms of the family Renicolidae Dollfus, 1939 (Trematoda: Plagiorchiida): molecular and comparative morphological analysis rejects the synonymization of Renicola pinguis complex suggested by Odening. Parasitology 2016, 143(12), 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herling, C.; Culik, B. M.; Hennicke, J. C. Diet of the Humboldt penguin (Spheniscus humboldti) in northern and southern Chile. Marine Biology 2005, 147(1), 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiriart-Bertrand, L.; Simeone, A.; Reyes-Arriagada, R.; Riquelme, V.; Pütz, K.; Luthi, B. Descripción de una colonia mixta de pingüino de Humboldt (Spheniscus humboldti) y de Magallanes (S. magellanicus) en Isla Metalqui, Chiloé, sur de Chile. Bol. Chil. Ornitol. 2010, 16, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, E. C.; Bray, R. A.; Bousfield, B. The presence of the trematodes Cardiocephaloides physalis and Renicola sloanei in the African Penguin Spheniscus demersus on the east coast of South Africa. Ostrich 2011, 82(2), 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerdy, H.; Baldassin, P.; Werneck, M. R.; Bianchi, M.; Ribeiro, R. B.; Carvalho, E. C. Q. First report of kidney lesions due to Renicola sp. (Digenea: Trematoda) in free-living Magellanic Penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus Forster, 1781) found on the coast of Brazil. J. Parasitol. 2016, 102(6), 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, G.; Ulloa, M.; Alegría, R.; Quezada, B.; Bennett, B.; Enciso, N.; Atavales, J.; Johow, M.; Aguayo, C.; Araya, H.; Neira, V. Stranding and mass mortality in humboldt penguins (Spheniscus humboldti), associated to HPAIV H5N1 outbreak in Chile. Prev. Vet. Med. 2024, 227, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, R.; Zavalaga, C.; Battistini, G.; Majluf, P.; McGill, P. Status of the Humboldt penguin in Peru, 1999-2000. Waterbirds 2003, 26, 129–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presswell, B.; Bennett, J. Two new species of kidney fluke (Trematoda: Renicolidae) from New Zealand penguins (Spheniscidae), with a description of Renicola websterae n. sp. Syst. Parasitol. 2025, 102(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rorato Nascimento de Matos, A.; Pereira Lavorente, F.; Lorenzetti, E.; Castro Meira Filho, M.; Farias da Nóbrega, D.; Lazaros Chryssafidis, A.; Goncalves de Oliveira, A.; Domit, C.; Rodrigues Loureiro Bracarense, A. Molecular identification and histological aspects of Renicola sloanei (Digenea: Renicolidae) in Puffinus puffinus (Procellariiformes): a first record. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28(3), 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Santana, C. M.; Marrero-Ponce, L.; Quesada-Canales, Ó.; Colom-Rivero, A.; Pino-Vera, R.; Cabrera-Pérez, M. A.; Miquel, J.; Melián-Melián, A.; Foronda, P.; Rivero-Herrera, C.; Caballero-Hernández, L.; Velázquez- Wallraf, A.; Fernandez, A. Unusual Mass Mortality of Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica) in the Canary Islands Associated with Adverse Weather Events. Animals 2025, 15(9), 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianna, J.; Cortes, M.; Ramos, B.; Sallaberry-Pincheira, N.; González-Acuña, D.; Dantas, G.; Morgante, J.; Simeone, A.; Luna-Jorquera, G. Changes in abundance and distribution of Humboldt penguin Spheniscus humboldti. Mar. Ornithol. 2014, 42, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |