Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

01 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study reports the fabrication of chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose (C/M) nanocomposites by electrolyte gelation-spray drying and the evaluation of their antibacterial performance as carriers for the antibiotic ampicillin. Chitosan (C), a cationic biopolymer derived from chitin, was combined with the anionic polysaccharide carboxymethyl cellulose (M) at different mass ratios to form stable nanocomposites via electrostatic interactions and then collected by a spraying dryer. The resulting particles exhibited mean diameters ranging from 800 to 1500 nm and zeta potentials varying from +90 to −40 mV, depending on the C:M ratio. The optimal formulation (C:M = 2:1 ratio) achieved a high recovery yield (71.1%) and ampicillin encapsulation efficiency EE (82.4%). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) confirmed the presence of hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions among C:M, and ampicillin within the nanocomposite matrix. The nano-microcomposites demonstrated controlled ampicillin release and pronounced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values of 3.2 µg/mL and 5.3 µg/mL, respectively, which were lower than those of free ampicillin. These results indicate that the chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose nano-microcomposites are promising, eco-friendly carriers for antibiotic delivery and antibacterial applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Preparation of Ampicillin-Loaded Chitosan/CMC Nanocomposites

Characterization of Nanocomposites

Ampicillin Encapsulation Efficiency and Release Kinetics

Antibacterial Activity Assay

Determination of MIC and MBC

Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Ratio on the Properties of Chitosan/Cellulose Nanocomposites Prepared by Spray Drying

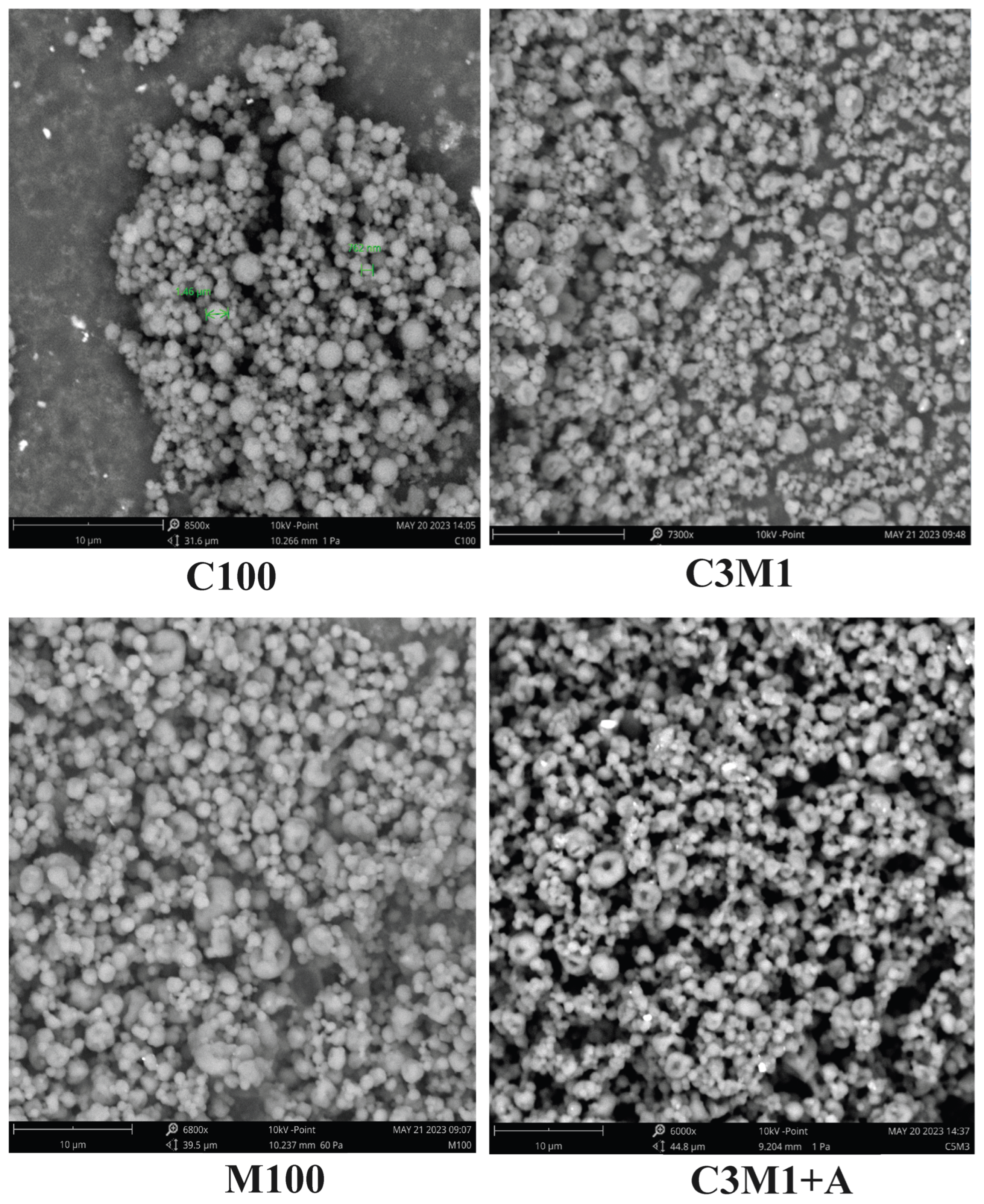

3.1.1. Particle Size and Morphology

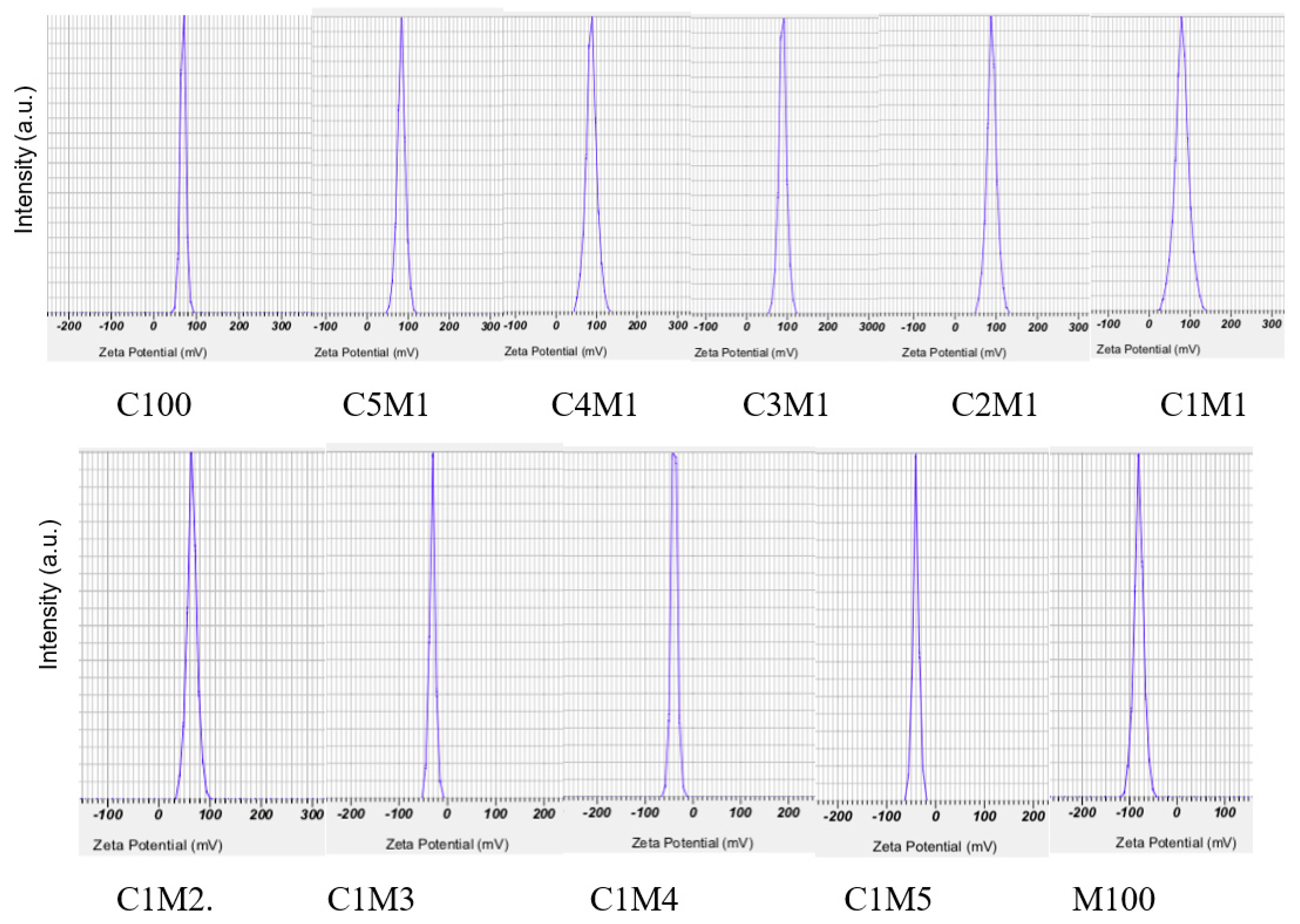

3.1.2. Zeta Potential and Colloidal Stability

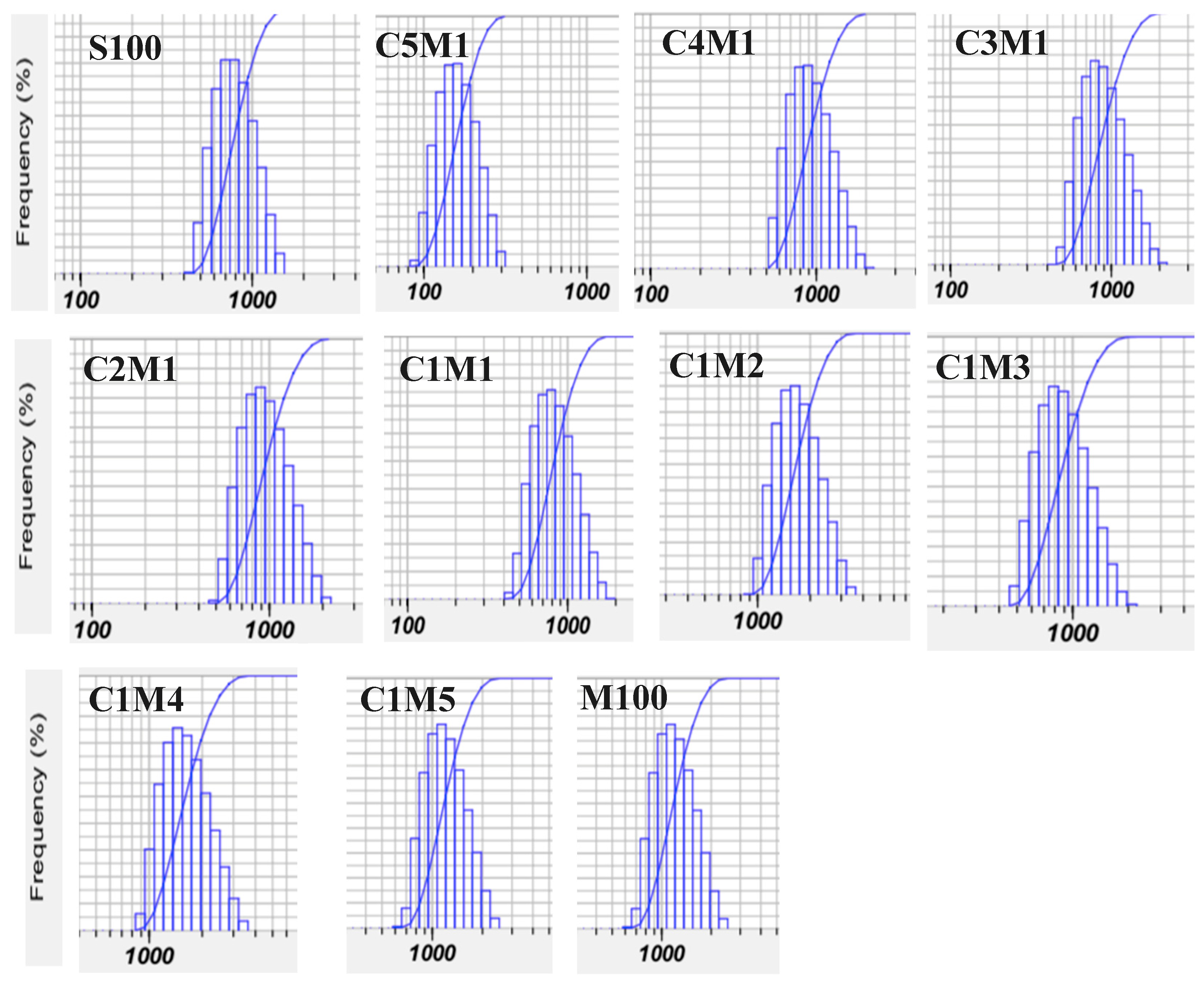

3.1.3. Particle Size Distribution and Recovery Yield

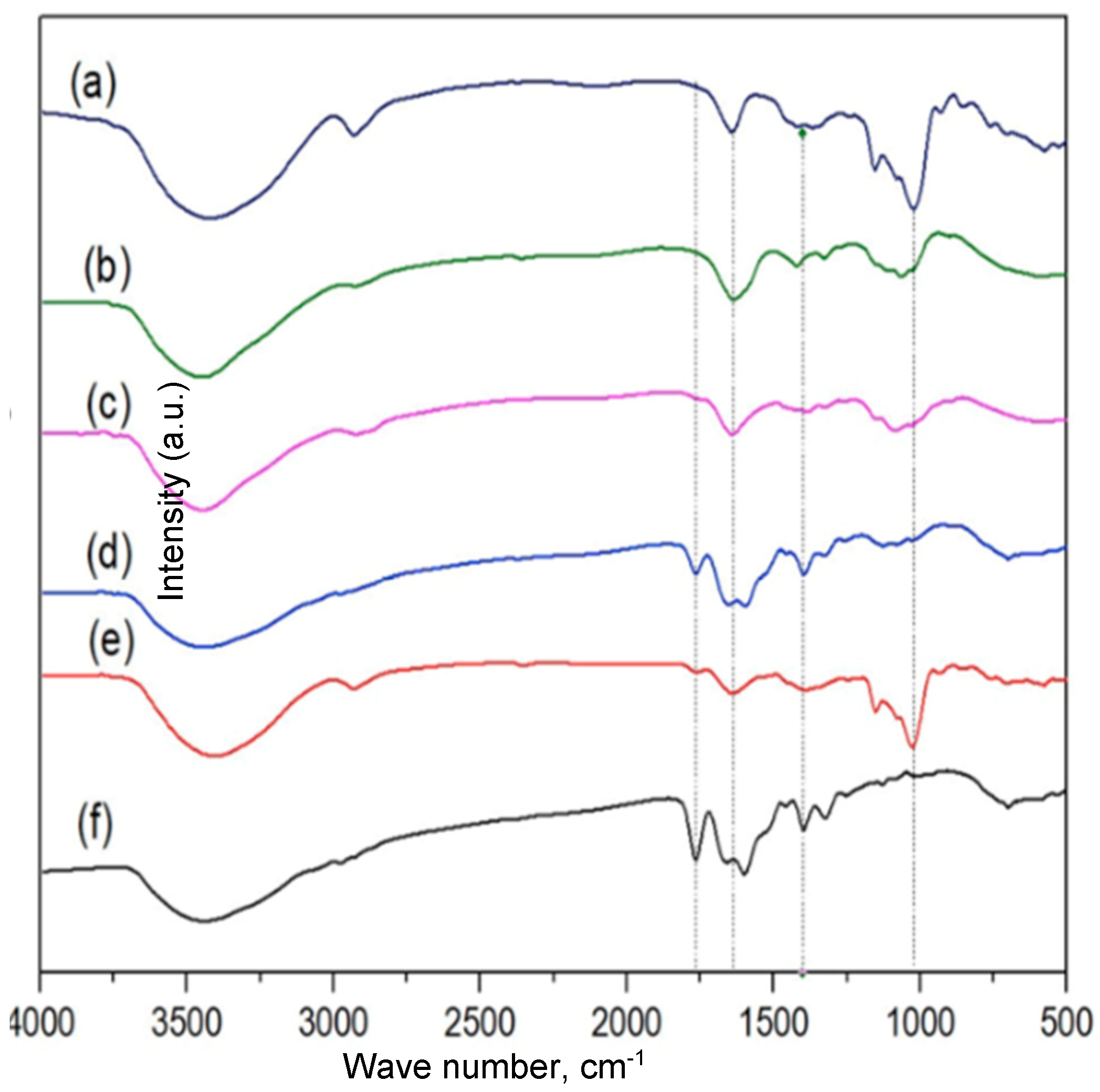

3.1.4. FT-IR Analysis of Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Nanocomposites

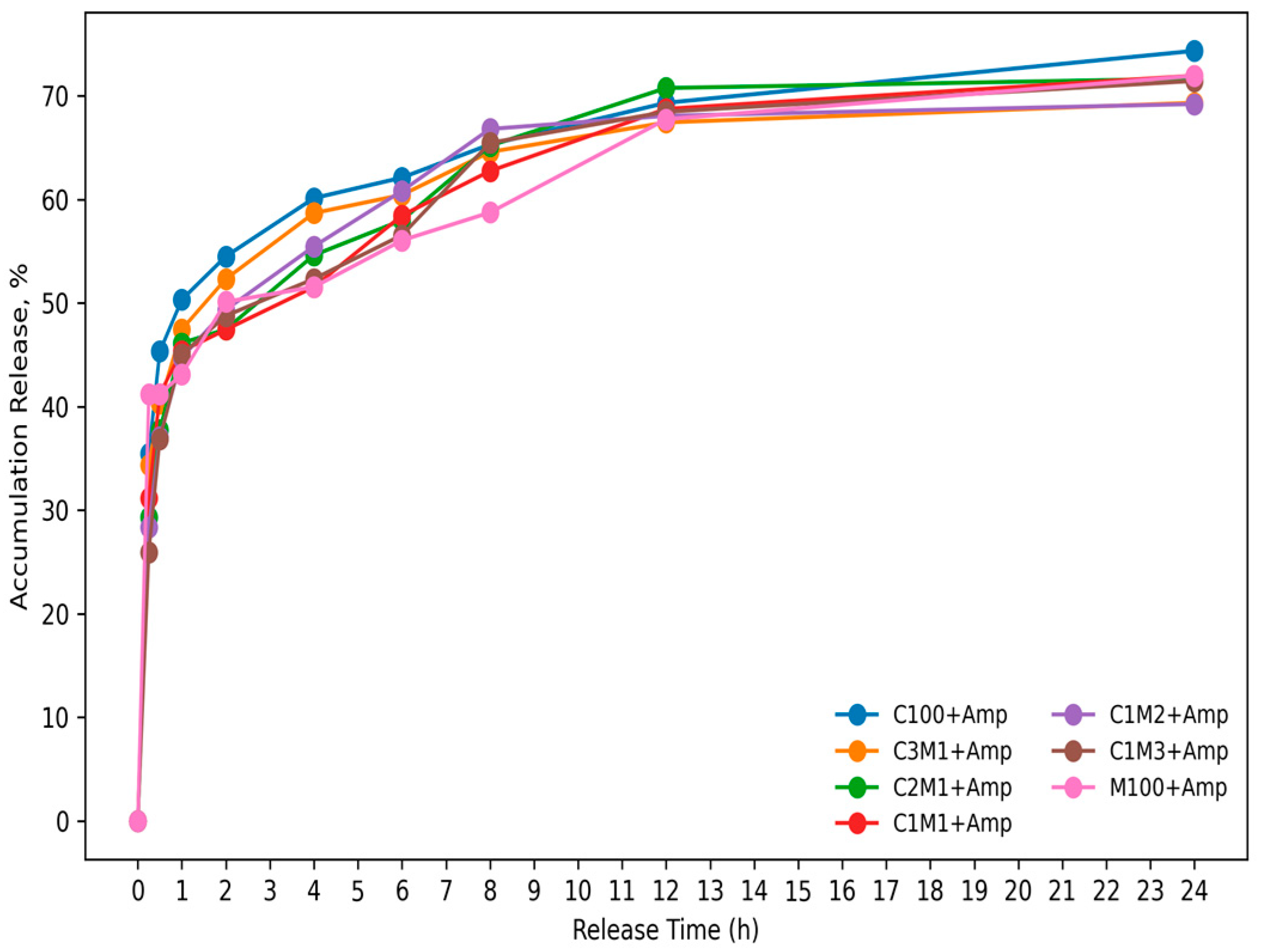

3.1.5. The Release Profile of Ampicillin from Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Nanocomposite

3.2. Antibacterial Activity of Ampicillin-Loaded Chitosan/Cellulose Nanocomposites Against Staphylococcus aureus

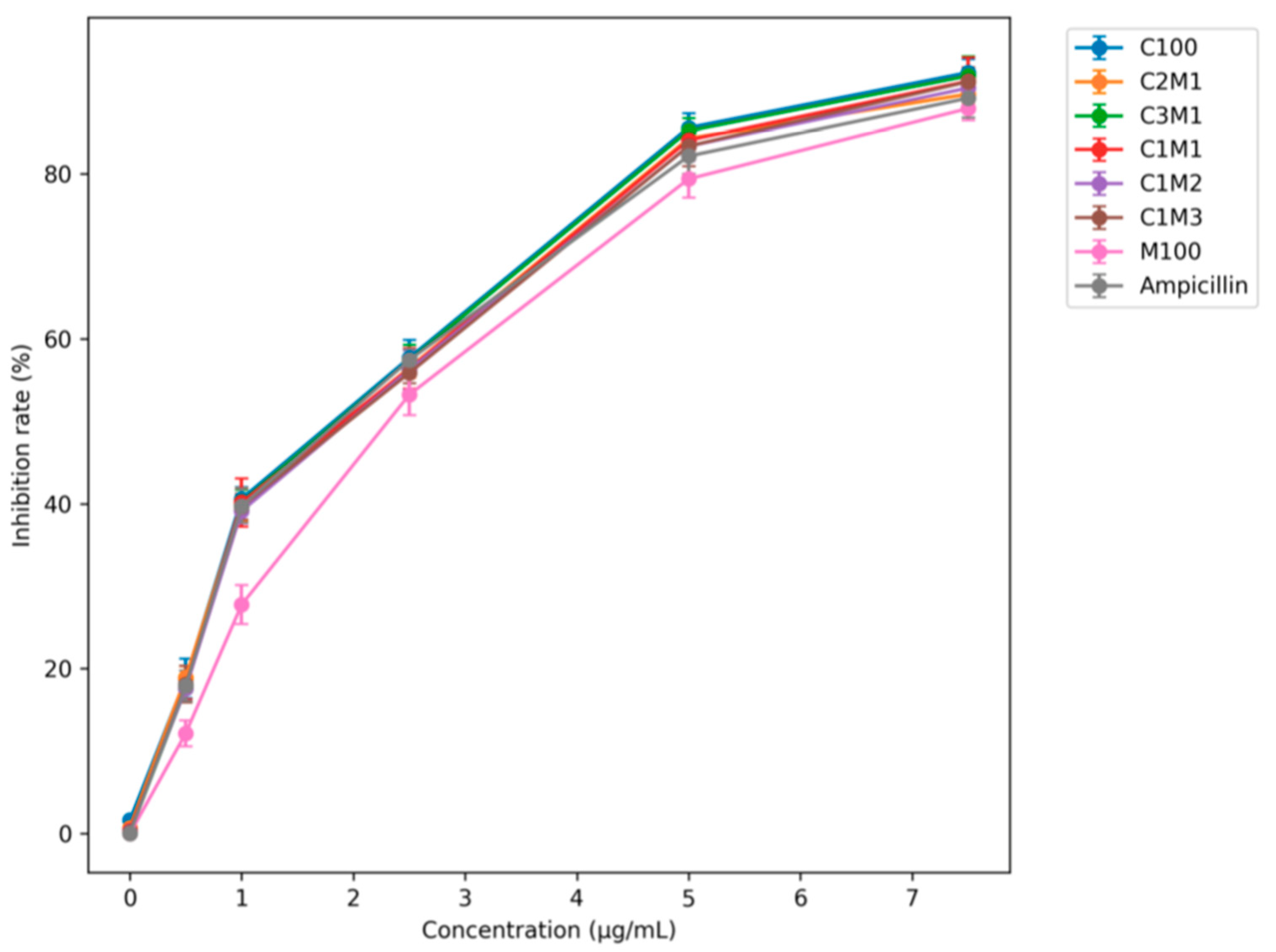

3.2.1. Effect of Ampicillin Loading on Antibacterial Activity

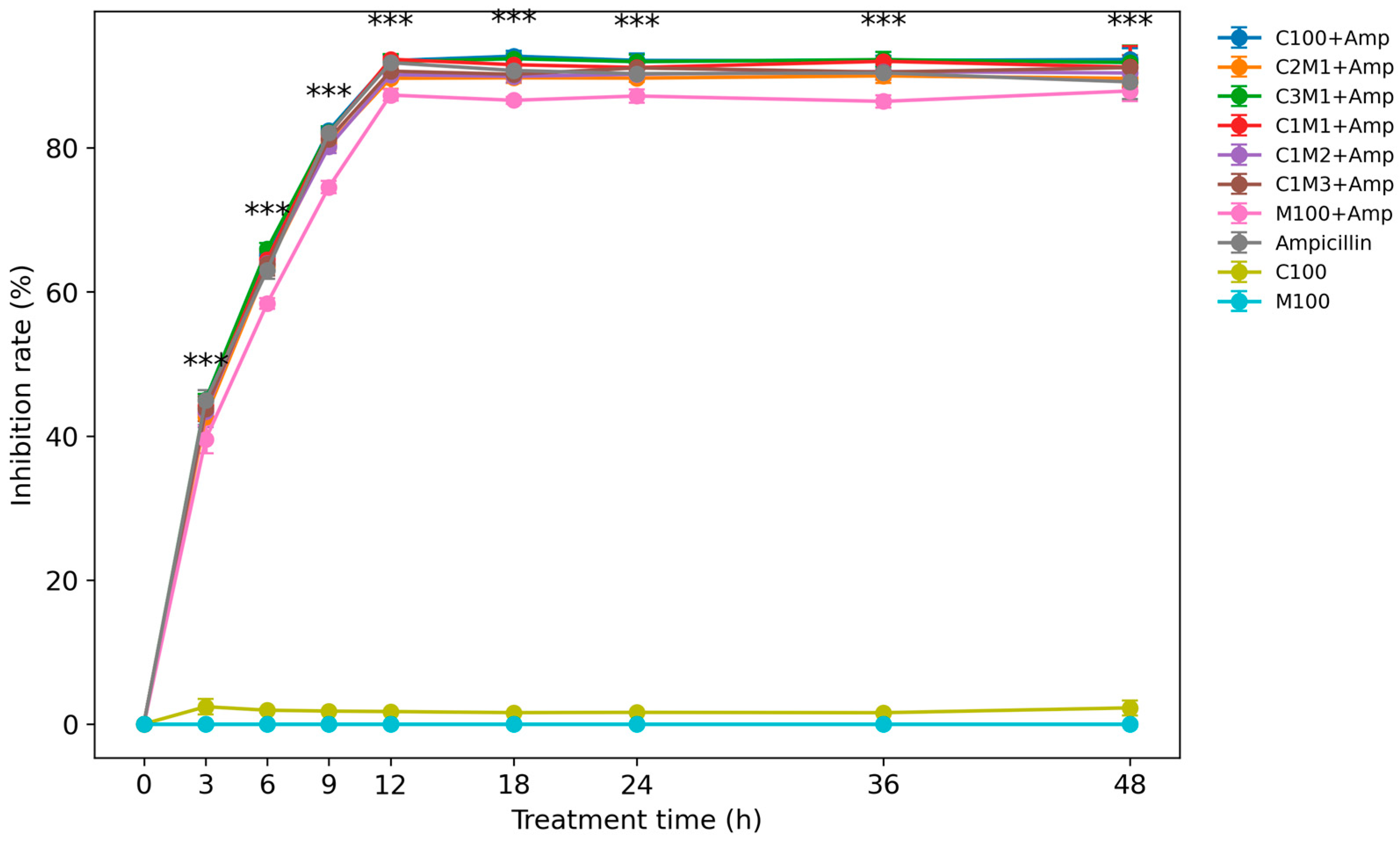

3.2.2. Time-Dependent Antibacterial Performance and Anti-Resistance Effect

3.2.3. MIC and MBC Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stefanache, A.; Lungu, I.I.; Anton, N.; Damir, D.; Gutu, C.; Olaru, I.; Plesea Condratovici, A.; Duceac, M.; Constantin, M.; Calin, G.; et al. Chitosan Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polymers 2025, 17, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Mondal, S.; Ansari, M.A.; Sarkar, T.; Condiuc, I.P.; Trifas, G.; Atanase, L.I. Chitosan and Its Derivatives as Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2025, 30, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Mahboubi, A.; Vatanara, A.; Mortazavi, A.S. Preparation of an Optimized Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Chitosan Nanomicelle with Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssekatawa, K.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Kato, C.D.; Ejobi, F.; Tweyongyere, R.; Lubwama, M.; Kirabira, J.B.; Wampande, E.M. Nanotechnological Solutions for Controlling Transmission and Emergence of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria: Future Prospects and Challenges. J. Nanopart. Res. 2020, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, M.A.; Maksoud, A.I.A.; Aladhadh, M.A.; Almuryif, K.A.; Elsanhoty, R.M.; Elebeedy, D. Gentamicin–Ascorbic Acid Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Improved in Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Minimized Cytotoxicity. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalek, I.; Svahn, I.; Mesli, S.; Simonneaux, G.; Mesli, A. Formulation, Evaluation and Microbiological Activity of Ampicillin and Amoxicillin Microspheres. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2014, 5, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Alarfaj, A.A. Preparation, Characterization and Antibacterial Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles against Food Spoilage Bacteria. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwaan, I.M.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Kelaby, K.K.A.; Allebban, Z.S.M. Starch–Chitosan Modified Blend as Long-Term Controlled Drug Release for Cancer Therapy. Pak. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 15, 947–955. [Google Scholar]

- Yanat, M.; Schoen, K. Preparation Methods and Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles with an Outlook toward Reinforcement of Biodegradable Packaging. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 161, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehyaeirad, N.; Babolanimogadam, N.; Dadkhah, M.; Shirmard, L.R. Polylactic Acid Films Incorporated with Nanochitosan, Nanocellulose, and Ajwain Essential Oil. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotie, G.; Limbo, S.; Piergiovanni, L. Manufacturing of Food Packaging Based on Nanocellulose: Current Advances and Challenges. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Ferrante, M.; Gende, L.; Alvarez, V.A.; Gonzalez, J.S. Polyelectrolyte Complex-Based Chitosan/Carboxymethylcellulose Powdered Microgels Loaded with Eco-Friendly Silver Nanoparticles. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; El-Bisi, M.K.; Taha, G.M.; El-Alfy, E.A. Preparation of Biocompatible Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Antibiotics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, Z.; Samani, S.M.; Montaseri, H.; Khezri, E. Nanoparticles of Chitosan Loaded with Ciprofloxacin: Fabrication and Antimicrobial Activity. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, R.; Abbas, S.R. Evaluation of Amygdalin-Loaded Alginate–Chitosan Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Wang, S.L.; Vo, T.T.H.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles by TPP Ionic Gelation Combined with Spray Drying. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 3527–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, I.; Margalit, R. Liposome-Encapsulated Ampicillin. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpoor, M.; Varasteh, S.; Pieters, R.J.; Folkerts, G.; Braber, S. Differential Effects of Oligosaccharides on Ampicillin Activity. PharmaNutrition 2021, 16, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, T.K.N.; Phung, M.L.; Wang, S.L.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles by Spray Drying. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2014, 40, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudih, S.B.; Tahtat, D.; Khodja, A.N.; Mahlous, M.; Hammache, Y.; Guittoum, A.E.; Gana, S.K. Chitosan Nanoparticles with Controlled Size and Zeta Potential. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Tran, M.D.; Doan, M.D.; Nguyen, D.S.; Nguyen, T.H.; Doan, C.T.; Wang, S.L.; Nguyen, A.D. Enhancing the Antibacterial Activity of Ampicillin-Loaded Chitosan/Starch Nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Res. 2024, 545, 109274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Doan, M.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Wang, S.L.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/Starch Nanocomposites Loaded with Ampicillin. Polymers 2024, 16, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, N.M.C.; Nguyen, T.H.; Wang, S.L.; Nguyen, A.D. Preparation of NPK Nanofertilizer Based on Chitosan Nanoparticles. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhani, A.R.; Kosaraju, S.L. Bioadhesive Chitosan Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašpar, O.; Jakubec, M.; Štěpánek, F. Characterization of Spray-Dried Chitosan–TPP Microparticles. Powder Technol. 2013, 240, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murei, A.; Ayinde, W.B.; Gitari, M.W.; Samie, A. Functionalization and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Antibiotics with Silver Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairi, V.; Medda, L.; Monduzzi, M.; Salis, A. Adsorption and Release of Ampicillin from Mesoporous Silica. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 497, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of Infrared Spectroscopy in Polysaccharide Structural Analysis. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustriane, C.; Dwivany, F.M.; Suendo, V.; Reza, M. Effect of Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticles on Banana Fruits. J. Plant Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein-Al-Ali, S.H.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Hussein, M.Z.; Geilich, B.M.; Webster, T.J. Ampicillin-Conjugated Magnetic Nanoantibiotic. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 3801–3814. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; El-Bisi, M.K.; Taha, G.M.; El-Alfy, E.A. Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded Antibiotics. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). High Levels of Antibiotic Resistance Found Worldwide. In WHO News Release; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, P.; Ma, Z.; Partow, A.J.; Kim, M.; Grace, M.; Shoemaker, G.M.; Tan, R.; Tong, Z.; Nelson, C.D.; Jang, Y.; Jeong, K.C. A Novel Combination Therapy Using Chitosan Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 195, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anal, A.K.; Stevens, W.F.; Remuñán-López, C. Ionotropically Cross-Linked Chitosan Microspheres. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 312, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxley, M.A.; Friedline, A.W.; Jensen, J.M.; Nimmo, S.L.; Scull, E.M.; Strange, S.; Xiao, M.T.; Smith, B.E.; King, J.B.; Rice, C.V. Efficacy of Ampicillin against MRSA. J. Antibiot. 2016, 69, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, C.A.; Balic, I.; Moreno, A.A.; Diaz, O.; Arenas Colarte, C.; Bruna Larenas, T.; Gamboa, A.; Caro Fuentes, N. Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Chiellini, F.; Ottenbrite, R.M.; Chiellini, E. Chitosan in Biomedical Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 981–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.A.; Aljaeid, B.M. Chitosan-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2016, 10, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.M.; Ferreira, S.O.; de Alvarenga, E.S.; de Fátima Ferreira Soares, N.; Coimbra, J.S.S.; de Oliveira, E.B. Polyelectrolyte Complexes of Chitosan and CMC. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100197. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.; Karakasyan, C.; Jouenne, T.; Le Cerf, D.; Dé, E. Polymeric Nanocarriers for Antibiotic Delivery. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Samples | Chitosan/CMC ratio (w/w) | Zeta potential (mV) | Mean particle size (nm) | Yield (%) |

Loading efficiency of ampicillin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C100 | 1:0 | 67.67±0.92 | 816.9±24.5e | 75.49±0.35a | 68.6±1.2c |

| 2 | C5M1 | 5:1 | 82.70±0.45 | 954.2±20.3e | 72.03±0.06b | 78.8±0.9b |

| 3 | C4M1 | 4:1 | 85.07±1.81 | 1049.8±28.7d | 71.88±0.07b | 79.2±1.3b |

| 4 | C3M1 | 3:1 | 89.53±1.89 | 1144.4±32.0d | 71.17±0.04b | 81.8±0.7a |

| 5 | C2M1 | 2:1 | 90.37±1.05 | 1288.8±24.3c | 71.08±0.03b | 82.4±1.4a |

| 6 | C1M1 | 1:1 | 78.63±1.02 | 1290.4±35.0c | 71.04±0.05b | 80.1±0.9b |

| 7 | C1M2 | 1:2 | 61.67±2.45 | 1304.7±26.3c | 70.71±0.06c | 75.8±1.9c |

| 8 | C1M3 | 1:3 | -31.43±0.65 | 1313.0±18.2c | 69.15±0.03d | 58.6±0.7d |

| 9 | C1M4 | 1:4 | -39.17±0.05 | 1652.5±42.5b | 69.06±0.04d | 56.3±0.4d |

| 10 | C1M5 | 1:5 | -40.00±0.72 | 1906.8±40.4a | 68.72±0.60e | 50.8±0.8e |

| 11 | M100 | 0:1 | -81.73±0.90 | 1658.9±38.7b | 67.01±0.06e | 38.8±0.6f |

| No. | Samples | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) | MBC/MIC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C100 + Amp | 3.53c ± 0.12 | 6.47c ± 0.12 | 1.83 |

| 2 | C2M1 + Amp | 3.20a ± 0.00 | 5.33a ± 0.12 | 1.66 |

| 3 | C1M1 + Amp | 3.30ab ± 0.12 | 5.73b ± 0.12 | 1.70 |

| 4 | C1M2 + Amp | 3.47c ± 0.12 | 5.80b ± 0.00 | 1.67 |

| 5 | M100 + Amp | 4.27d ± 0.12 | 7.07e ± 0.12 | 1.65 |

| 6 | Ampicillin (Amp) | 4.23d ± 0.12 | 6.80d ± 0.00 | 1.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).