1. Introduction

Nanotechnology has transformed the landscape of modern medicine, offering innovative solutions for drug delivery systems (DDS) [

1]. Among these, nanoparticles (NPs) have gained prominence due to their unique properties, such as biocompatibility, controlled release, and enhanced targeting capabilities [

2]. The integration of biopolymers like chitosan (CS) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) into nanoparticle systems further expands their potential applications in therapeutic and antimicrobial treatments [

3,

4]. Despite the advantages, challenges such as poor solubility and stability of drugs continue to hinder effective therapeutic outcomes, necessitating new delivery systems to address these limitations [

5,

6].

Natural products, such as honey bee and propolis, and synthetic compounds like bis-tetrahydro-1,3,5-thiadiazine-2-thione (bis-THTT, JH1, and JH2), are known for their biological activity, including antimicrobial and antimalarial effects [

7,

8]. However, their clinical application is often limited by rapid degradation and suboptimal bioavailability [

9]. Encapsulating these compounds in biopolymer-based nanoparticles can significantly enhance their stability, targeted delivery, and therapeutic efficacy [

10].

The current study addresses these challenges by exploring CS-PVP-based nanoparticles as carriers for both synthetic and natural compounds. Previous research highlights the potential of CS for its mucoadhesiveness and antimicrobial activity and PVP for its stabilizing properties, yet the synergistic combination of these polymers remains underexplored.

This work aims to synthesize, optimize, and characterize CS-PVP-based nanoparticles for the encapsulation of bis-THTT´s (JH1, JH2), and natural products (Honey bee, and Propolis). Investigate their physicochemical properties, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and drug release profiles. This study could establish a robust platform for developing multifunctional drug delivery systems (DDS), advancing treatments for microbial infections and malaria, and demonstrating the potential of integrating natural resources into cutting-edge nanotechnology [

11,

12].

2. Materials and Methods

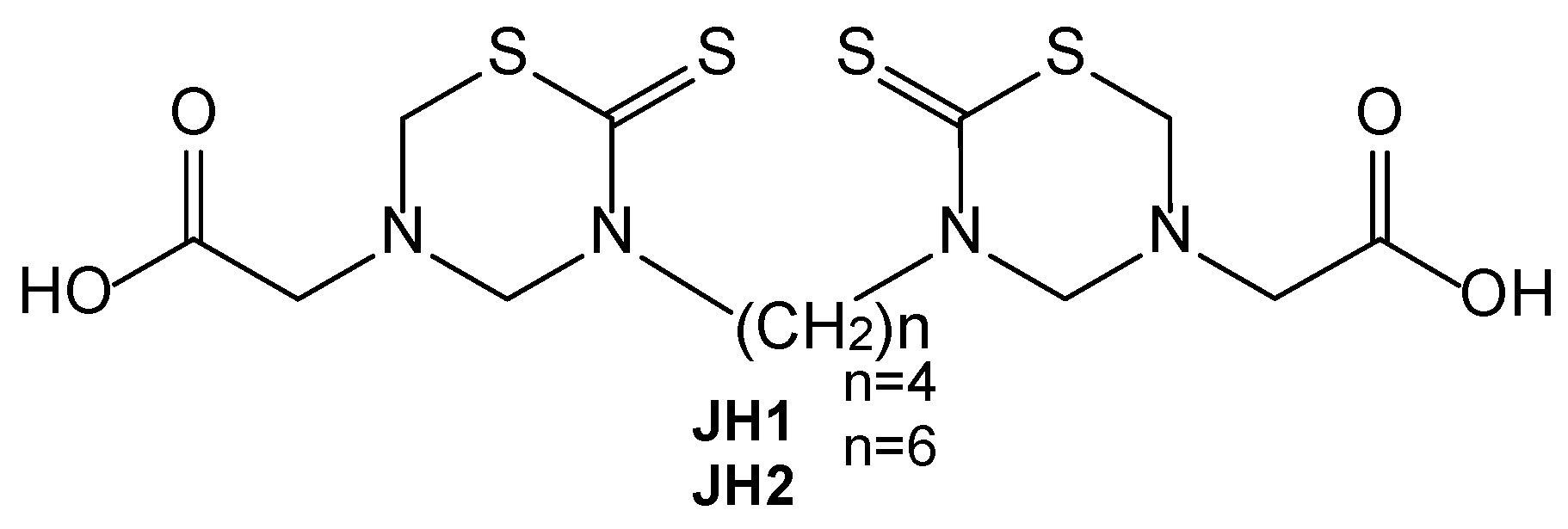

Raw materials used for the preparation of NPs include low molecular weight chitosan (LMWCS) and high molecular weight chitosan (HMWCS) from Sigma Aldrich (United States). Glacial acetic acid (AA) ACS grade 100% pure (Fisher Chemical, United States), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (M.W.: 40,000 kDa), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets (Sigma Aldrich, United States), sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP), and type I distilled water were used in this research. JH1 and JH2 (

Figure 1) were synthesized in the Organic Synthesis Laboratory at the University of Havana and kindly donated by Professors Hortensia Rodriguez and Julieta Coro. Honey bees and Propolis were sourced from the community of Iruguincho, located in San Miguel de Urcuquí, Ecuador.

2.1. Chitosan (CS)-Based Nanoparticles (CS-NPs)

Both high and low-molecular-weight CS were separately dissolved in 10 ml of a 10% acetic acid solution under magnetic stirring. The resulting solution was then diluted with type I water to obtain a final chitosan concentration of 0.2% (w/v) [

13]. The pH of the chitosan solution was adjusted to 5.85 using 2 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). A 0.07% (w/v) TPP solution was prepared [

14] and added dropwise to the chitosan solution at volumetric ratios of CS:TPP of 1:0.5, 1:0.75, 1:1, and 1:1.25 under magnetic stirring at 1000 rpm for 2 hours at room temperature. The ionic gelation process was initiated by the addition of TPP, leading to the formation of CS NPs. The NPs were then separated by centrifugation [

15] at 6000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was ultra-frozen at –80°C and freeze-dried for 72 hours.

2.2. Chitosan (CS)-Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-Based Nanoparticles (CS-PVP NPs)

LMWCS (M.W.: 150-250 kDa, 76% deacetylation degree, Sigma Aldrich, United States) was mixed with PVP at LMWCS:PVP ratios of 1:0.5, 1:0.75, 1:1, and 1:1.25. The mixture was dissolved in 10 ml of a 10% acetic acid solution and further diluted with type I water to reach a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v). The pH was adjusted to 5.79 with 2 M NaOH. A 0.07% (w/v) TPP solution was added in a volumetric ratio of 1:0.5 under continuous stirring at 1000 rpm for 1.5 hours. The nanoparticles were separated by centrifugation and processed as described above.

2.3. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds

The synthetic derivatives bis-THTT (JH1 and JH2) were pre-dissolved in DMSO to enhance their solubility in the acidic CS-PVP solution, whereas the natural products (Honey bee and Propolis) were directly dissolved into the solution before the ionic gelation method [

16,

17]. The final concentration of each compound was 0.1% (w/v). TPP was added to the solution at a 1:1 volumetric ratio under continuous stirring at 1000 rpm for 1.5 hours. The NPs were separated by centrifugation and freeze-dried as described above.

2.4. Nanoparticles Characterization

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): FTIR spectra were recorded using a Spectrum Two FTIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Inc., United States) with a diamond ATR accessory. The spectra were collected in the range of 4000 to 650 cm⁻¹.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): TGA was performed using a TGA 55 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, United States) with a heating rate of 20°C per minute from room temperature to 850°C in a nitrogen atmosphere.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): XRD analysis was conducted using a Minifelx 600 diffractometer (Rigaku Analytical Instruments, United States) with CuKα radiation. The diffraction pattern was recorded in the 2θ range from 20° to 90°.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): AFM imaging was performed using an AFM NX7 (Park Systems, Korea) to study the surface morphology of the NPs. Samples were prepared at a concentration of 0.0001% and deposited onto 1 cm² silicon plates.

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the NPs was evaluated using the disk diffusion method. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 were cultured in nutrient broth and plated on Mueller-Hinton agar. The nanoparticles were applied to sterile paper disks, and inhibition zones were measured after 24 hours of incubation at 35°C. The positive controls used were ampicillin for E. coli and vancomycin for S. aureus.

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity was evaluated using the MTT colorimetric assay. 3T3 mouse fibroblasts were cultured in a 96-well microplate and incubated with NP solutions at concentrations of 5 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml. The MTT reagent was added to each well, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm after 72 hours of incubation at 37°C.

2.7. In Vitro Cumulative Release Study

The controlled release of the encapsulated compounds was studied by dispersing 15 mg of lyophilized NP in 15 ml of artificial gastric fluid (AGF), simulating gastrointestinal conditions. The release profile was monitored by measuring the absorbance of the solution at 280 nm using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

Polymer nanoparticles were prepared using CS and PVP as scaffold structures. The synthetical procedures were optimized to establish better options related to CS/TPP, and CS/PVP ratios. Besides, NPs encapsulated bis-THTT (JH1 and JH2), Honey bees, and Propolis were prepared to test the potential of CS- and CS-PVP-based nanoparticles to be efficient carriers for synthetic compounds (JH1 and JH2) and natural products (Honey bees and Propolis).

3.1. CS-PVP-Based NPs Synthesis and Cargos Encapsulation

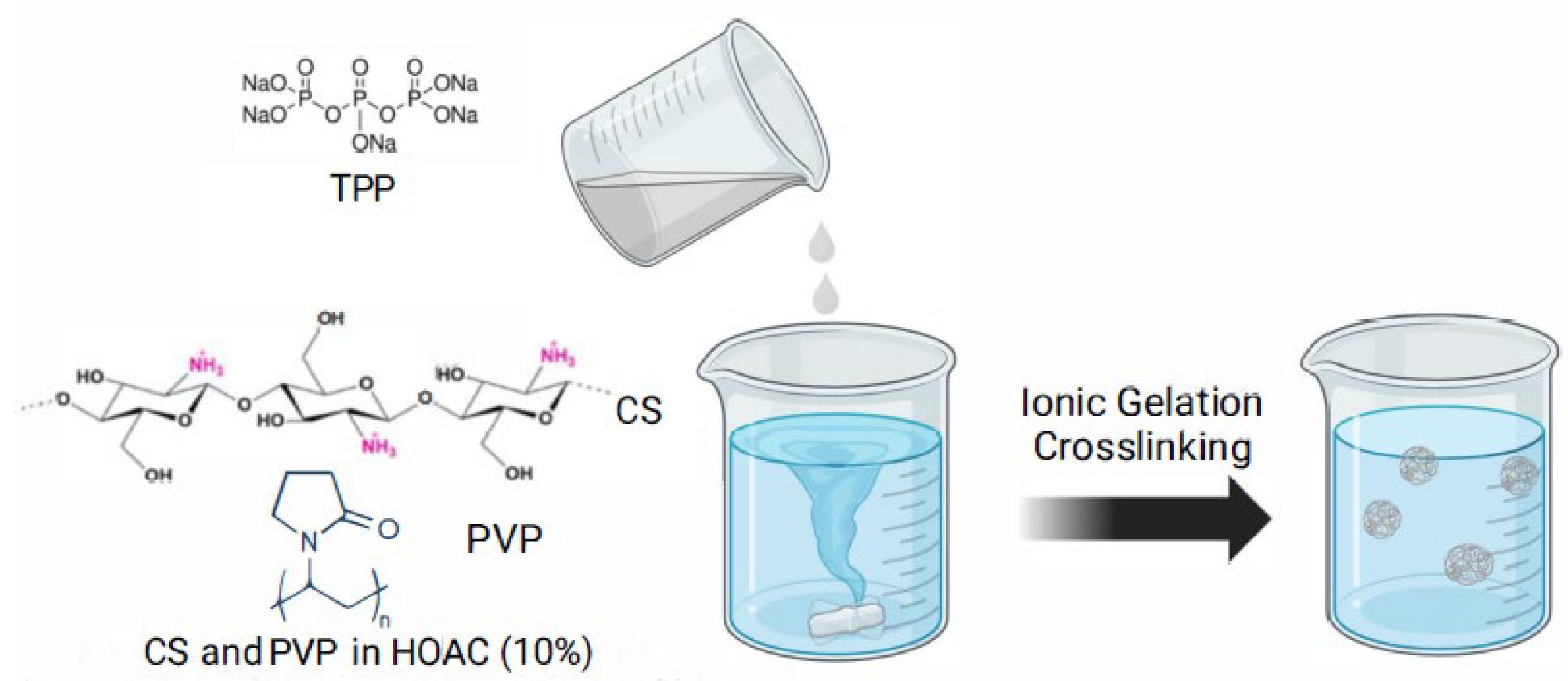

LMWCS was selected to optimize CS-PVP-based NPs. HMWCS was also tested exhibiting early material agglomerations and phase separation, leading to its exclusion in this research. The CS-PVP-based NPs were prepared using the ionic gelation method, which

is based on ionic crosslinking in the presence of the inversely charged groups of the protonated amino groups of CS and negatively charged groups of the TPP (

Figure 2), as it

has been previously used [

18]

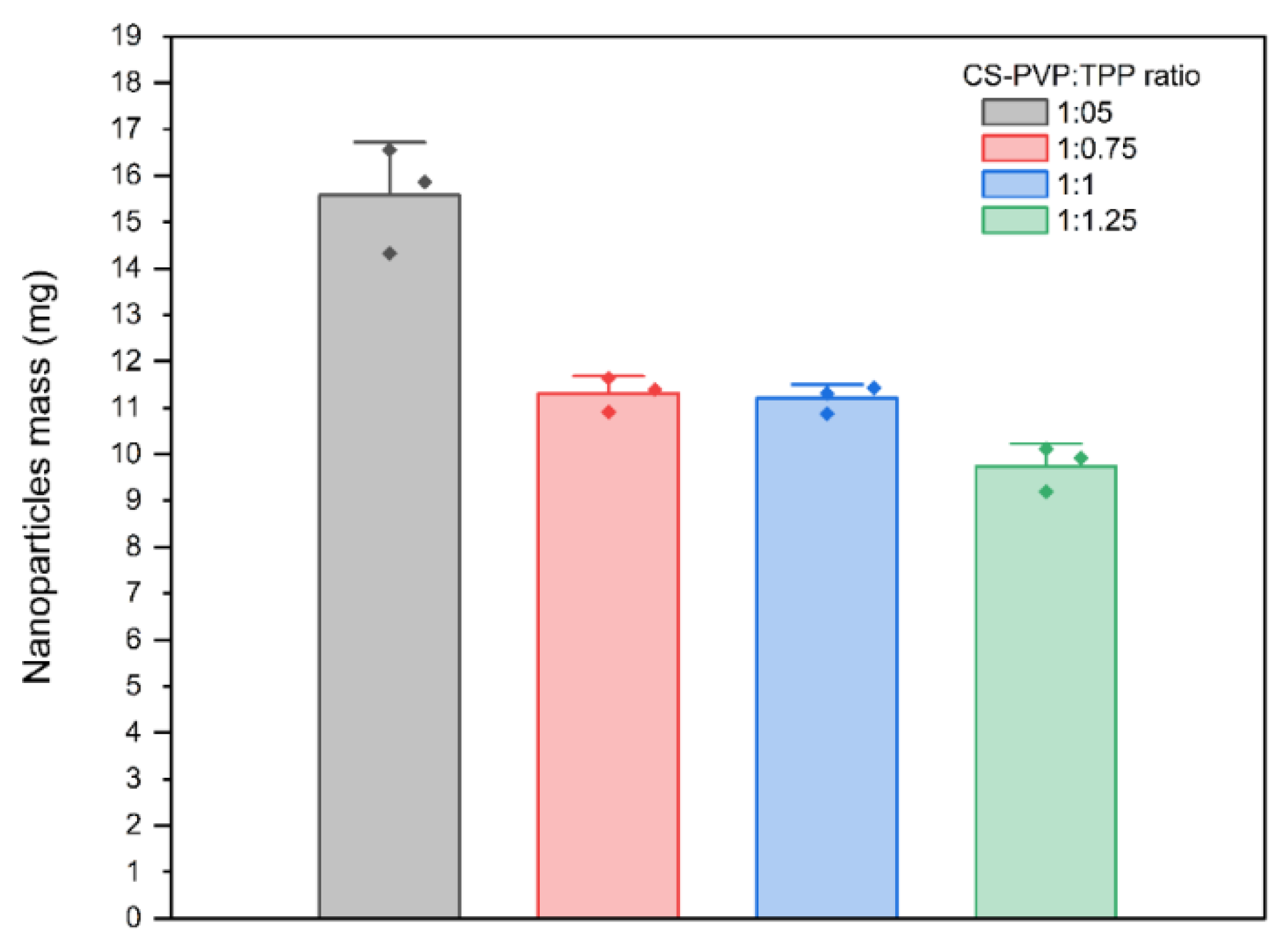

. In this context, different CS:PVP ratios were tested, starting from 1:0.5 and increasing the PVP proportion to 1:0.75, 1:1, and 1:1.25. It was found that the CS:PVP ratio that gives the best result was 1:0.5. Also, different ratios between the CS-PVP solution and the cross-linking agent (TPP) were tested, finding that the CS-PVP:TPP ratio of 1:0.5 shows the best results in terms of NP formation and quantity (

Figure 3).

As the CS:TPP ratio increases, the resulting NPs exhibit larger sizes and a propensity to form agglomerates that precipitate at the bottom of the reaction vessel, consistent with previously reported findings [

14].

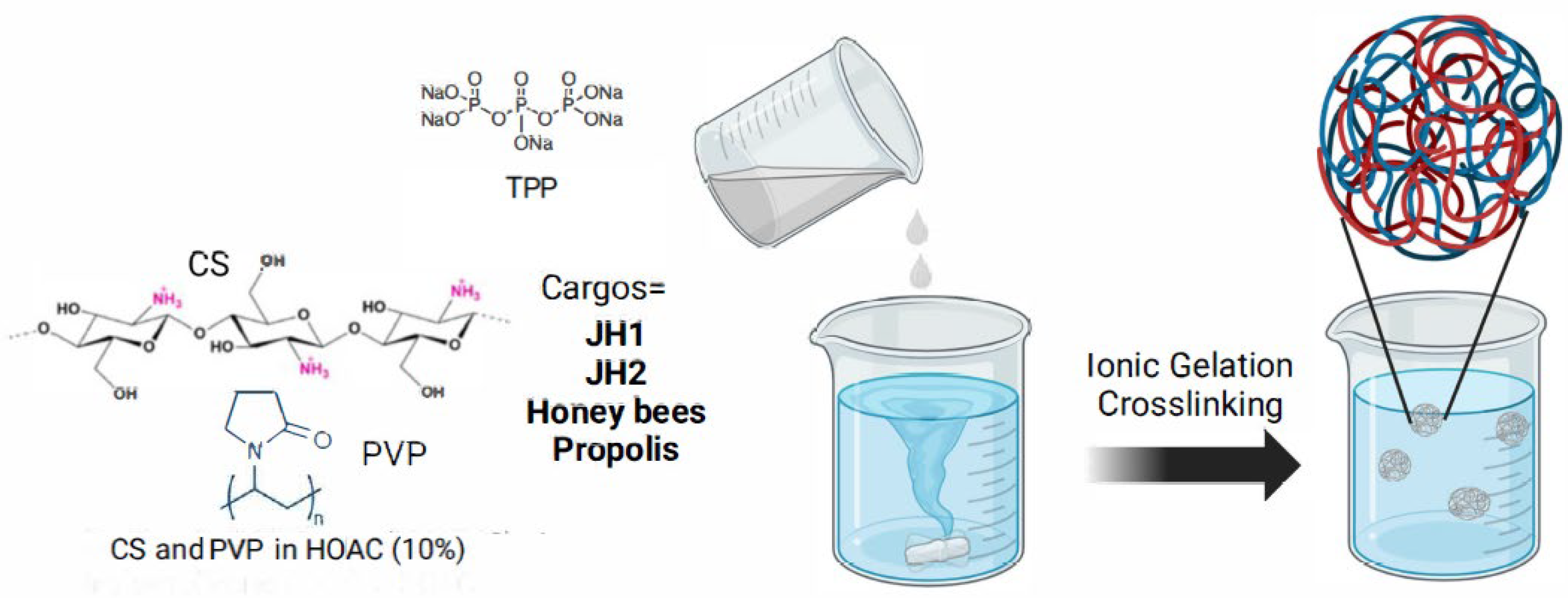

To leverage the synergistic properties of CS and PVP, NPs loaded with cargos (JH1, JH2, honey, and propolis) were prepared (

Figure 4). The dissolution of the cargos in the CS-PVP matrix caused the cross-linking agent ratio to also change, obtaining a new optimal CS-PVP:TPP ratio of 5:2. This is because the addition of the new molecules into the CS-PVP matrix which also implies more interactions of the different functional groups present in the chemical structure of the cargos.

CS-PVP NPs encapsulating both, synthesized compounds (bis-THTT, JH1, and JH2), and natural products (Honey bee and Propolis) were obtained, and their full physicochemical characterization was carried out to corroborate their formation and main features. The CS-PVP-based NPs can leverage the advantages of both materials, resulting in NPs with enhanced properties. The biocompatibility, mucoadhesiveness, and antimicrobial activity of CS complement the solubility and stability provided by PVP.

3.3. CS-PVP NPs Characterization

3.3.1. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

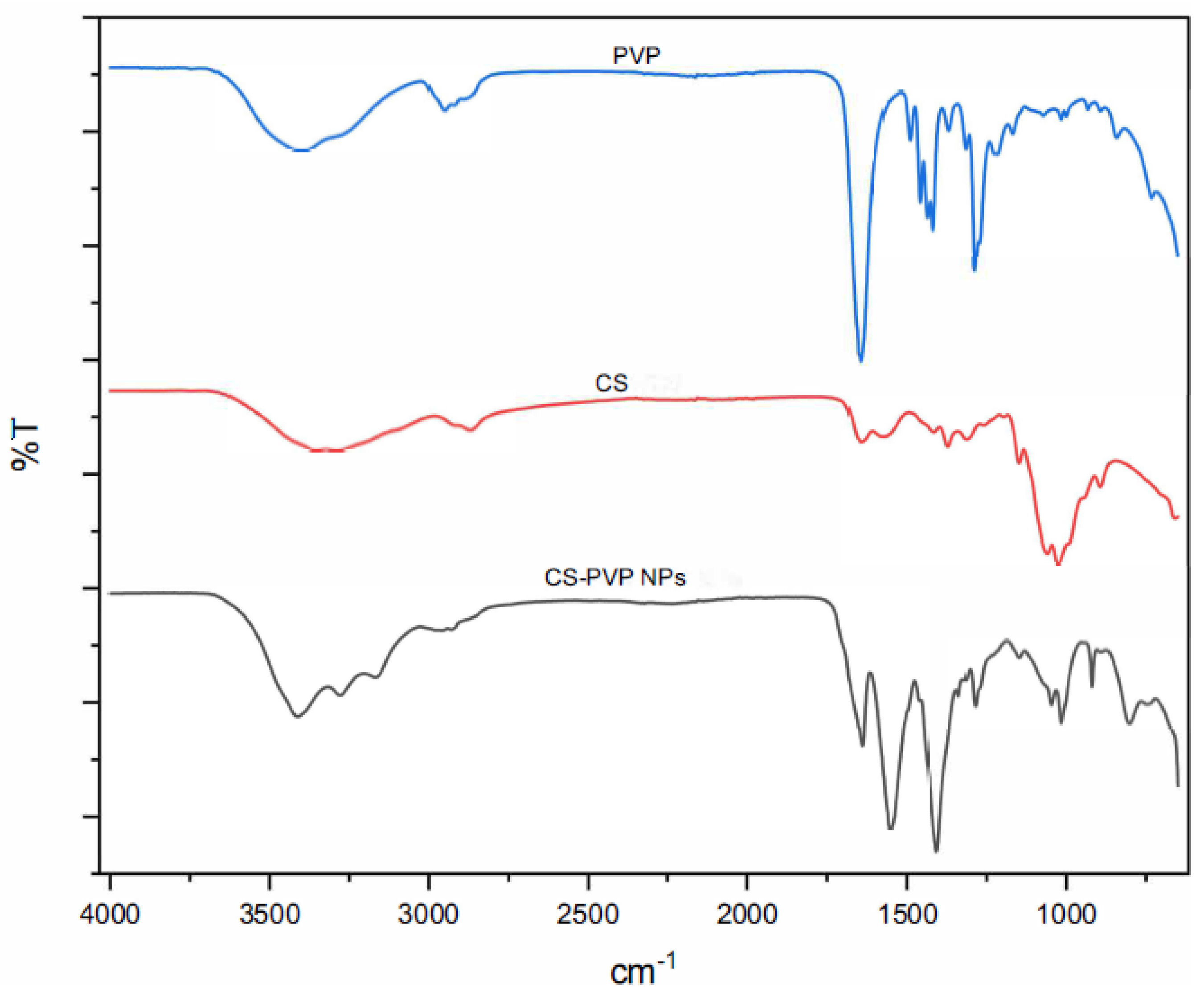

FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of characteristic bands of the precursors: CS, and PVP (

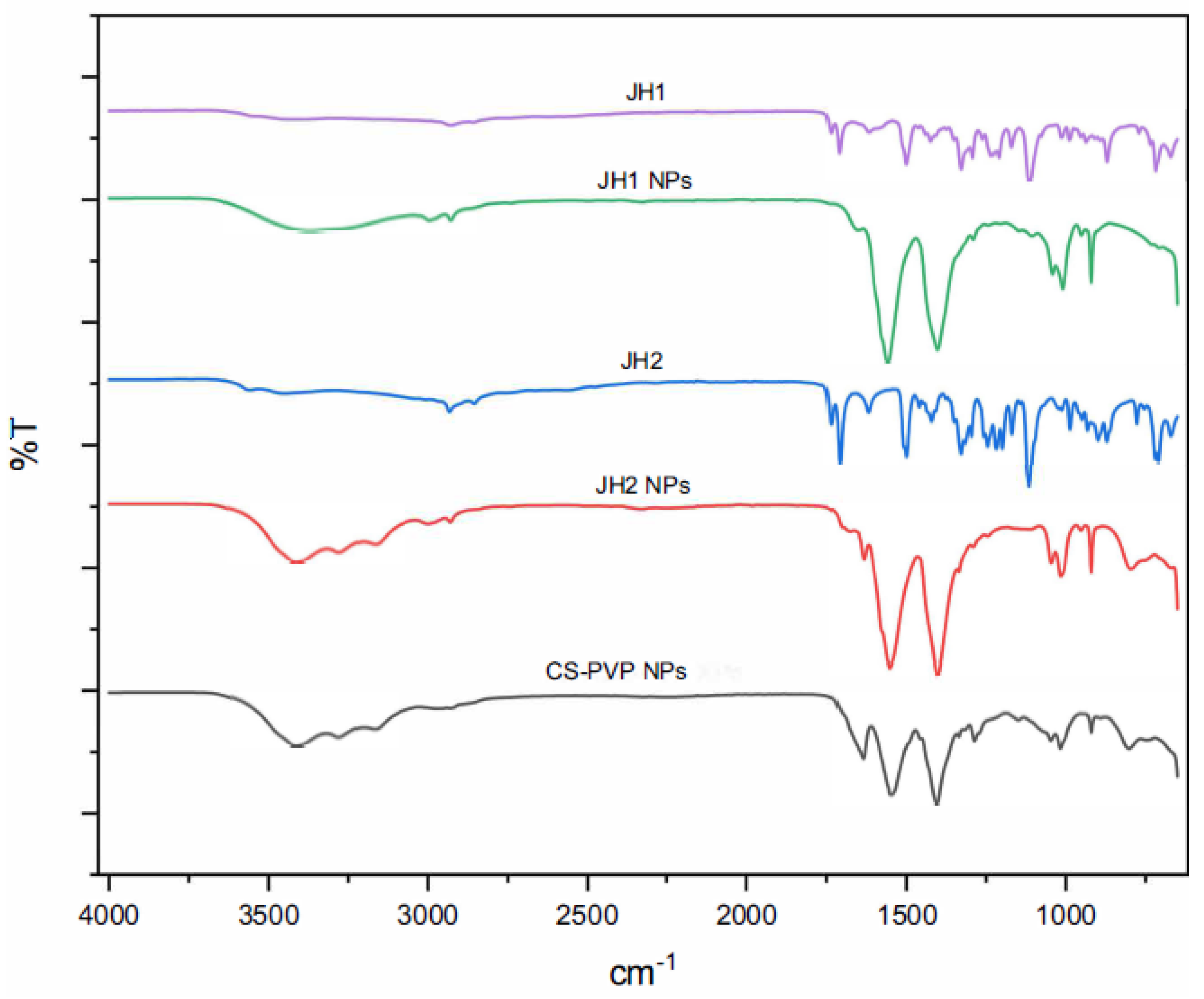

Figure 5), and the encapsulated compounds: bis-THTTs (JH1 NPs and JH2 NPs) (

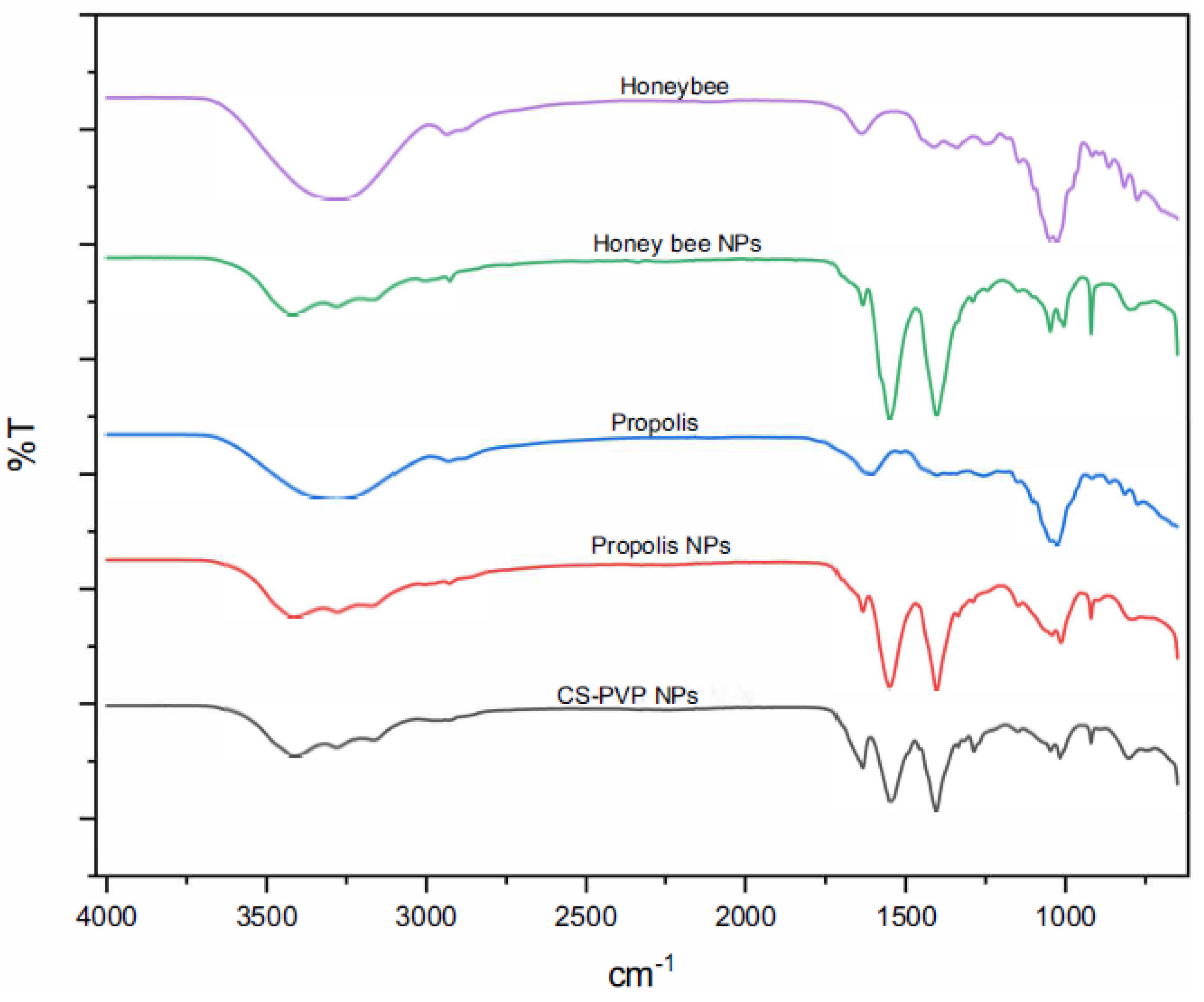

Figure 6), honey bee NPs and propolis NPs (

Figure 7). Bands attributed to the amide bond (-NH) and hydroxyl groups (-OH) were observed in the range of 3200-3400 cm⁻¹ [

19], indicating hydrogen bond interactions. The specific bands of PVP, such as those corresponding to the C=O groups, were found at 1660-1680 cm⁻¹ [

20], confirming the integration of PVP into the NPs matrix (

Figure 5). On the other hand, the spectra of bis-THTT NPs (JH1 NPs and JH2 NPs) showed characteristic peaks [

21,

22] of the C=N bond at 1520 cm⁻¹ and the C-S bond at 700-750 cm⁻¹ [

23], indicating their incorporation into the NPs (

Figure 6).

The spectra of honey bee NPs and propolis NPs presented bands at 3200-3300 cm⁻¹, associated with hydroxyl groups (-OH) [

24], and peaks at 1400-1600 cm⁻¹, corresponding to phenols and flavonoids [

25], which confirmed their encapsulation (

Figure 7).

These results show the formation of NPs and the interaction between the components, highlighting the role of CS and PVP in the stabilization and encapsulation of the investigated compounds.

3.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

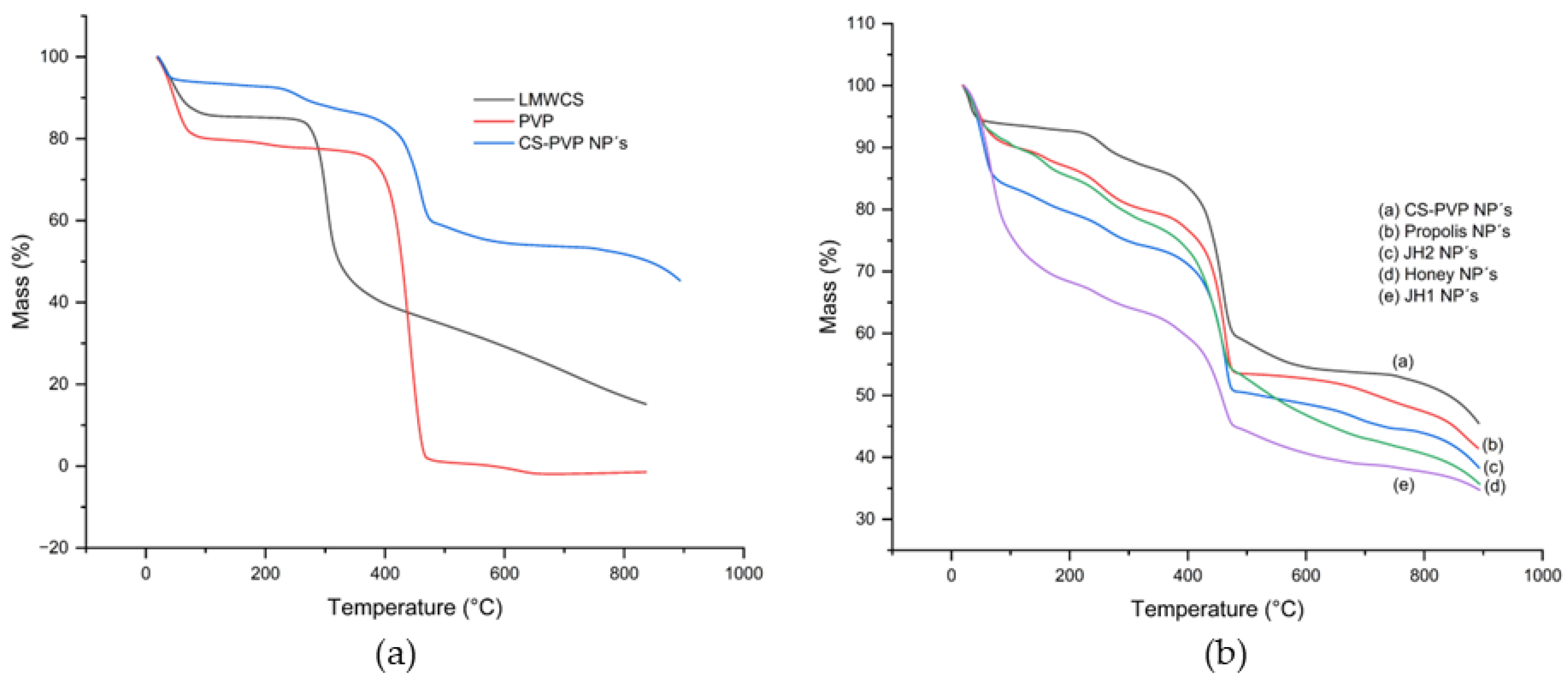

The thermogravimetric behavior of starting materials CS and PVP, and the CS-PVP NP´s were studied. In the case of CS, an initial mass loss of 10-12% was observed between 50-100 °C (

Figure 8a, black line), attributed to the removal of absorbed water [

26]. The main decomposition occurred in the range of 250-350 °C, associated with the degradation of the polysaccharide (

Figure 8a, black line) [

27]. On the other hand, PVP exhibited a gradual weight loss between 150-350 °C, with a significant degradation peak at 360 °C approximately, due to the breaking of C-N bonds and the decomposition of its polymeric structure (

Figure 8a, red line) [

28,

29]. CS-PVP NPs showed an improvement in thermal stability compared to the individual components (

Figure 8a, blue line). Water loss occurred at 50-100 °C, while the main degradation was observed in the range of 398-473 °C, reflecting a synergistic interaction between chitosan and PVP. On the other hand, the cargos (JH1, JH-2, Honey bee, and Propolis) induce a lower thermal stability of the CS-PVP NPs [

30] (

Figure 8b).

For JH1, the main decomposition range was 145–178 °C, while in JH1 NPs it was considerably broadened to 135–225 °C, indicating enhanced low-temperature resistance (

Figure 8b). The maximum decomposition temperature increased from 321 °C in JH1 to 456 °C in JH1 NPs, reflecting a significant improvement in thermal stability. For JH2, the initial decomposition range was 135–175 °C, while in JH2 NPs it shifted to a higher range of 410–480 °C, evidencing significant thermal stabilization. The decomposition temperature decreased from 521 °C in JH2 to 323 °C in JH2 NPs, which may be a result of chemical interactions between the compound and the NP matrix [

32]. Also, the residual mass increased from 0 % to non-encapsulated compounds (JH1 and JH2) to 38 % in loaded NPs, suggesting protection of the encapsulated material (

Figure 8b) [

31] (Supporting Information, Figure SI-A).

For Honey bees, the main decomposition range was 170-260 °C, while in Honey bee NPs it was extended to 400-470 °C, showing an improvement in thermal stability. The maximum decomposition temperature increased from 225 °C in Honey bee to 541 °C in Honey bee NPs. The residual mass increased from 0 % in pure honey to 36 % in NPs, demonstrating effective protection against complete decomposition. For propolis, the main decomposition range was 170-240 °C, while in propolis NPs it shifted to 420-480 °C. The decomposition temperature increased from 268 °C in Propolis to 719 °C in Propolis NPs and the residual mass also increased from 1 % to 41 %. Empty CS-PVP NPs showed the highest thermal stability (Supporting Information, Figure SI-A).

3.3.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Consistent with its amorphous nature [

33,

34], CS and PVP displayed a broad, diffuse diffraction pattern (Supporting Information, Figure SI-B (a)). A notable increase in intensity at 2θ was observed in the range of 20°-30°, attributed to the presence of semicrystalline regions within the CS and PVP structure respectively [

35]. A significant deviation in the XRD pattern was observed for CS-PVP NPs compared to their polymeric components [

36]. The presence of multiple sharp and well-defined peaks, notably within at 2θ in the range of 15°-30°, provided evidence for the formation of a highly crystalline structure within the nanoparticles [

17,

37]. These results suggest that hydrogen bond formation between the pyrrolidine rings of PVP and the amino and hydroxyl groups of CS during NP formation facilitated an increase in the degree of order and crystallinity within the material [

38].

The XRD results of cargos JH1 and JH2 showed that both are predominantly amorphous materials. JH1 exhibits a characteristic diffraction pattern of amorphous materials (Supporting Information, Figure SI-B (b)) and JH2 presents some weak peaks indicating a certain degree of crystalline order (Supporting Information, Figure SI-B (c)). Upon incorporating JH1 and JH2 into the NPs, a decrease in the intensity of the characteristic peaks of CS-PVP NPs and a slight shift towards higher 2θ angles was observed. As was expected, the presence of the synthetic cargo reduces the overall crystallinity of the system [

39,

40].

XRD analysis of loaded NPs with natural products (Honey bee NPs and Propolis NPs) also revealed a decrease in their crystallinity compared to empty CS-PVP NPs (Supporting Information, Figure SI-B (d)). While both Honey bee NPs and Propolis NPs presented multiple peaks at 2θ in the range of 15°-50°, the intensity and definition of these peaks were lower. This reduction in crystallinity is attributed to the presence of amorphous components and the more disordered nature of honey and propolis, in addition to the water content in these natural products. When comparing both, Propolis NPs showed a higher signal intensity, indicating a slightly higher degree of crystallinity compared to Honey bee NPs.

The decrease in crystallinity of CS-PVP NPs containing cargos (synthetic products JH1 and JH2, and natural products such as Honey bee and Propolis) could be attributed to the increased structural disorder due to the complexity of the cargos and their interactions with the CS and PVP during the formation of the NPs.

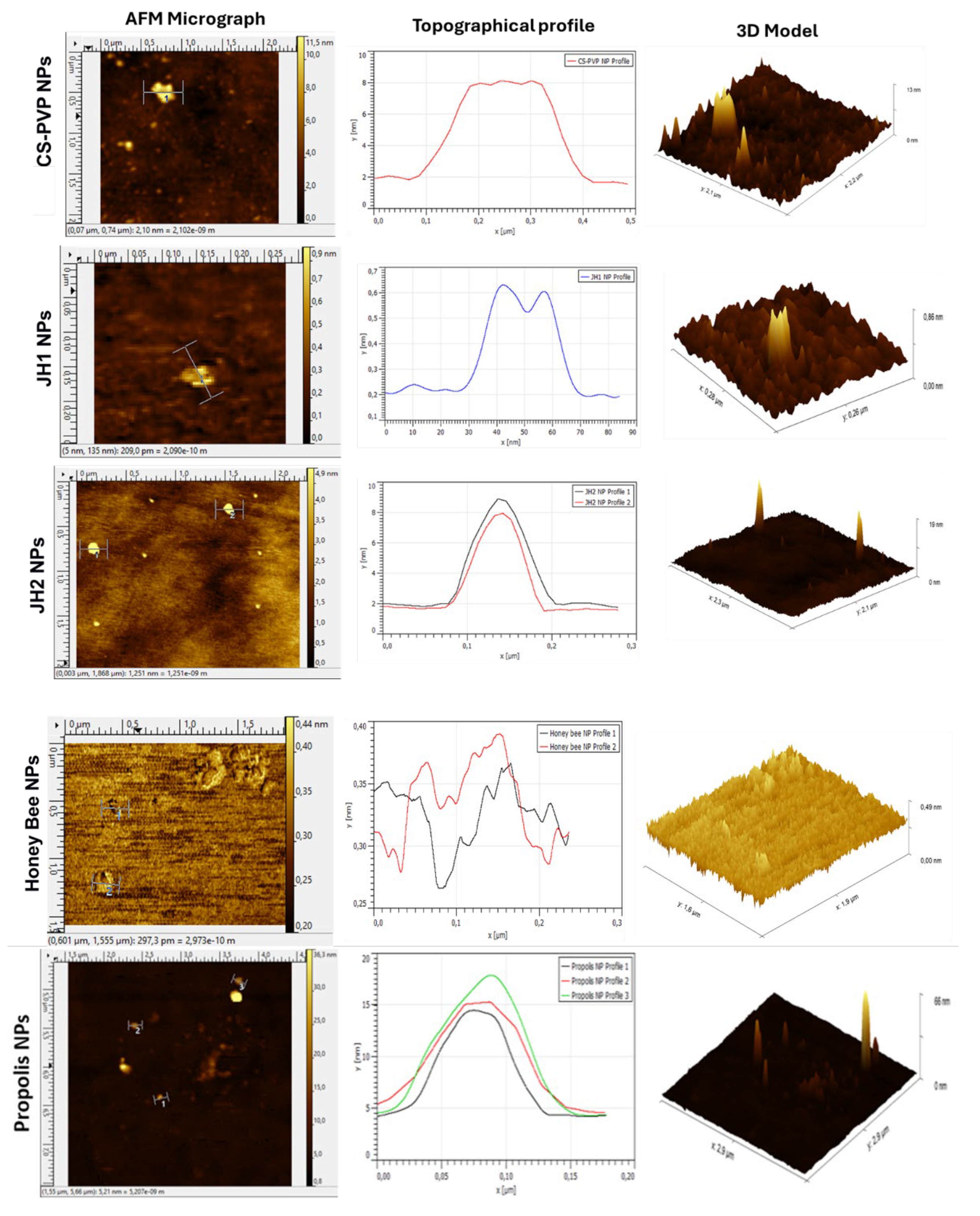

3.3.4. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Micrographs obtained by AFM (

Figure 9) confirmed the successful formation of nanoparticles by the ionic gelation method. For CS-PVP NPs, a concentration of 0.0001% allowed clear images to be obtained. In the 3D model, these nanoparticles presented a three-peak structure with a height of approximately 8 nm and a width of 0.3 µm.

JH1 NPs showed a smaller size compared to CS-PVP NPs, with an average height of 0.4 nm and a width of 40 nm, suggesting that interactions between components during ionic gelation reduced the particle size. On the other hand, JH2 NPs presented a more uniform morphology, with an approximate height of 6 nm and a width of 100 nm, which was also corroborated by the 3D model.

The NPs encapsulating natural products showed distinct characteristics. Honey bee NPs formed agglomerates due to the moist nature of honey, although isolated NPs with heights of 0.37 nm and 0.39 nm, and widths of 0.23 µm and 0.15 µm were identified. In the case of Propolis NPs, the agglomerates were attributed to the sugars and phenolic compounds present, but three isolated nanoparticles with heights of 14.5 nm, 15 nm, and 17 nm, and widths of 0.10 µm, 0.15 µm, and 0.12 µm, respectively, were also identified.

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activities against S. aureus 25923 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were established through the disk diffusion method. The CS-PVP-based nanoparticles did not display antibacterial activity toward S. aureus 25923, probably due to the high resistance of this strain [

41,

42]. On the other hand, the prepared NPs displayed antibacterial activity toward E. coli ATCC 25922 (Supporting Information, Figure SI-C). In general, the prepared NPs demonstrated higher efficacy than non-encapsulated cargos [

43], although ampicillin as positive control and chloroquine (CQ) were the most effective materials (Supporting Information, Figure SI-C).

JH1 NPs showed an inhibition halo of 0.52 mm (vs. 0.48 mm to JH1) and JH2 NPs showed 0.51 mm (vs. 0.49 mm to JH2). In contrast, Honey bee NPs with 0.46 mm and Propolis NPs with 0.43 mm of inhibition halo, were less effective than their non-encapsulated forms (0.47 mm and 0.49 mm, respectively) (Supporting Information, Figure SI-C).

The data followed a normal distribution according to the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05). ANOVA analysis revealed significant differences between at least nine types of nanoparticles (p < 0.05), confirmed in some cases by the Tukey test.

3.5. Cytotoxic Evaluation

Cytotoxicity analysis demonstrated that all investigated NPs have low cytotoxicity and maintain high cell viability in 3T3 mouse fibroblasts. JH1 NPs presented the highest average absorbances, with 1.38 ± 0.03 at 5 µg/ml and 1.27 ± 0.07 at 10 µg/ml. JH2 NPs also showed positive results, with absorbances close to those of JH1 NPs, although slightly lower, supporting their low cytotoxicity (Supporting Information, Figure SI-E).

Honey bee NPs presented absorbances of 1.25 ± 0.04 (5 µg/ml) and 1.22 ± 0.02 (10 µg/ml), while Propolis NPs maintained similar high absorbances. Although absorbances decreased at higher concentrations, all loaded NPs outperformed the positive control, confirming their safety for therapeutic applications [

44,

45,

46]. Empty NPs (CS-PVP NPs) showed very high absorbances, similar to the loaded ones, indicating that the CS and PVP matrix are not cytotoxic on their own and contribute to the biocompatibility of the evaluated systems. ANOVA statistical analysis at 2 hours of incubation revealed significant differences between JH1 NPs and Honey bee NPs at 5 µg/ml (p = 0.035), while at 10 µg/mL no significant differences were found between any of the nanoparticles (p > 0.05) (Supporting Information, Figure SI-D).

3.6. Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%), Load Capacity (LC%), and Cumulative Release

The NPs showed moderate encapsulation efficiencies (EE) and loading capacities (LC) according to the literature [

47]. Propolis NPs stood out with an EE of 60 % and an LC of 28 %, being the highest (Supporting Information, Figure SI-E). JH2 NPs reached an EE of 55 % and an LC of 25 %, while JH1 NPs presented the lowest values, with an EE of 44 % and an LC of 22 %. Honey bee NPs had an EE of 51 % and a LC of 26 %, reflecting good chemical compatibility with the polymeric matrix.

In the release study (Supporting Information, Figure SI-F), JH2 NPs released approximately 20% of the encapsulated compound after 180 minutes, showing a more controlled and sustained release profile compared to Propolis NPs and Honey bee NPs. Shapiro-Wilk statistical analysis confirmed a normal distribution of the data (p > 0.05). ANOVA and Tukey test revealed significant differences in EE and LC between most nanoparticles (p < 0.05), except between JH2 NPs and Honey bee NPs (p = 0.22) and between Propolis NPs and Honey bee NPs (p = 0.10), where no significant differences were found (Supporting Information, Figure SI-F).

NPs encapsulating natural products showed higher cumulative release. Propolis NPs achieved 28% release and Honey bee NPs achieved 26% at the end of the 180 min (Supporting Information, Figure SI-F). This behavior is related to the chemical composition of natural products: the multiple phenolic and flavonoid compounds in propolis, together with the sugars, proteins, and phenolic compounds in honey bees [

48,

49], facilitate their encapsulation and controlled release.

In NPs encapsulating synthetic compounds, JH2 NPs presented a higher cumulative release of 20%, while JH1 NPs, which had the lowest encapsulation efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) values, achieved only 15% cumulative release (Supporting Information, Figure SI-F).

4. Conclusions

Chitosan-polyvinylpyrrolidone (CS-PVP)-based nanoparticles (NPs) were successfully synthesized by ionic gelation method, using TPP as a cross-linking agent. The optimal proportions to control the size and avoid agglomeration of the NPs were CS:PVP (1:0.5) and CS-PVP:TPP (5:2). Characterization by FTIR, TGA, XRD, and AFM confirmed the formation of the NPs and the effective encapsulation of bis-THTT (JH1 and JH2) and natural antimicrobials (Honey bee and Propolis).

FTIR evidenced interactions between polymers and encapsulated compounds, while TGA showed higher thermal stability in encapsulated NPs, especially for natural products (honey and propolis), which outperformed synthetic compounds (JH1 and JH2) in stability before 450 °C. XRD analysis revealed more ordered systems after NP formation, although some loss of order was observed upon incorporation of compounds. AFM micrographs validated the morphological formation of NPs.

In terms of antimicrobial activity, NPs showed moderate efficacy against E. coli ATCC 25922, and none against S. aureus 25923, probably due to the higher intrinsic resistance of the latter. Chloroquine exhibited superior activity, while the inhibition zones observed for the NPs and their encapsulated compounds were significantly lower than that of the positive control.

Cytotoxicity assessment confirmed that the NPs are not cytotoxic at concentrations of 5 and 10 µg/ml in 3T3 fibroblasts after 4 hours of incubation, indicating their biocompatibility. Release studies demonstrated encapsulation efficiencies (44-60%) and loading capacities (22-28%), with Propolis NPs standing out in both parameters. The cumulative release did not exceed 30% in 180 minutes, which positions them as promising systems for the sustained release of therapeutic compounds.

As a conclusion, CS-PVP cross-linked with TPP-based NPs show promising properties for encapsulating other therapeutic molecules. It could be envisaged that the encapsulation of more biologically active molecules will allow us to highlight the benefits of these NPs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R. and L.S.; methodology, H.R., P.E. and L.S..; formal analysis and validation, H.R. P.E. and L.S..; investigation, P.E.; resources, H.R., P.E. and L.S.; data curation, P.E.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R. and P.E.; writing—review and editing, H.R. and F.A..; supervision and project administration, H.R. and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

To the School of Chemical Sciences and Engineering of the Yachay Experimental Technology Research University for providing the necessary laboratory equipment and materials for this experiment. Also, to the technical team of the institution's laboratories for their kind attention and support during the laboratory experiments. The research was partially supported by Yachay Tech Internal Project (CHEM-25-01).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boisselier E, Astruc D. Gold nanoparticles in nanomedicine: preparations, imaging, diagnostics, therapies and toxicity. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(6):1759-1782. [CrossRef]

- Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: Recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Jiao Y, Wang Y, Zhou C, Zhang Z. Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(15):1650-1662. [CrossRef]

- Bashir SM, Ahmed Rather G, Patrício A, et al. Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Versatile Platform for Biomedical Applications. Materials. 2022;15(19). [CrossRef]

- Cho CS, Hwang SK, Gu MJ, et al. Mucosal Vaccine Delivery Using Mucoadhesive Polymer Particulate Systems. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;18(5):693-712. [CrossRef]

- De Jong WH, Borm PJA. Drug delivery and nanoparticles: Applications and hazards. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3(2):133-149.

- Ortiz M, Rodríguez H, Lucci E, et al. Serological Cross-Reaction between Six Thiadiazine by Indirect ELISA Test and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Methods Protoc. 2023;6(2). [CrossRef]

- Niu Y. An Overview of Bioactive Natural Products-Based Nano-Drug Delivery Systems in Antitumor Chemotherapy. In: E3S Web of Conferences. Vol 271. ; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Zhang Y, Yu T, et al. Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(10). [CrossRef]

- Sohail M, Rabbi F, Younas A, et al. Herbal Bioactive-Based Nano Drug Delivery Systems.; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):941-951. [CrossRef]

- Kumari A, Yadav SK, Yadav SC. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles based drug delivery systems. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2010;75(1):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Hoang NH, Thanh T Le, Sangpueak R, et al. Chitosan Nanoparticles-Based Ionic Gelation Method: A Promising Candidate for Plant Disease Management. Polymers (Basel). 2022;14(4). [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar NEA, Shiha AM, Mahrous H, Mohammed ABA. Green synthesis of chitosan nanoparticles, optimization, characterization and antibacterial efficacy against multi drug resistant biofilm-forming Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Yuan Z, Ye Y, Gao F, et al. Chitosan-graft-β-cyclodextrin nanoparticles as a carrier for controlled drug release. Int J Pharm. 2013;446(1-2):191-198. [CrossRef]

- Hafizi T, Shahriari MH, Abdouss M, Kahdestani SA. Synthesis and characterization of vancomycin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery. Polymer Bulletin. 2023;80(5):5607-5621. [CrossRef]

- Ali SW, Rajendran S, Joshi M. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan and silver loaded chitosan nanoparticles for bioactive polyester. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83(2):438-446. [CrossRef]

- Yanat M, Schroën K. Preparation methods and applications of chitosan nanoparticles; with an outlook toward reinforcement of biodegradable packaging. React Funct Polym. 2021;161:104849. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford). 2006;31(7):603-632. [CrossRef]

- Silva MF, Da Silva CA, Fogo FC, Pineda EAG, Hechenleitner AAW. Thermal and ftir study of polyvinylpyrrolidone/lignin blends. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2005;79(2):367-370. [CrossRef]

- Coro J, Atherton R, Little S, et al. Alkyl-linked bis-THTT derivatives as potent in vitro trypanocidal agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(5):1312-1315. [CrossRef]

- Loachamin KS, Rodríguez HM. Effect of six bis-THTT derivatives in the control of parasitaemia in two rodent malaria species. Bionatura. 2019;02(Bionatura Conference Serie). [CrossRef]

- De P, Térmica M, Bitumenes EN, et al. ÍNDICES DE ABSORCIÓN POR ESPECTROSCOPIA INFRARROJA COMO. Vol 44.; 2013.

- Da Silva PM, Gauche C, Gonzaga LV, Costa ACO, Fett R. Honey: Chemical composition, stability and authenticity. Food Chem. 2016;196:309-323. [CrossRef]

- Kędzierska-Matysek M, Matwijczuk A, Florek M, et al. Application of FTIR spectroscopy for analysis of the quality of honey. BIO Web Conf. 2018;10:02008. [CrossRef]

- Corazzari I, Nisticò R, Turci F, et al. Advanced physico-chemical characterization of chitosan by means of TGA coupled on-line with FTIR and GCMS: Thermal degradation and water adsorption capacity. Polym Degrad Stab. 2015;112:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak A, Mucha M. Thermogravimetric and FTIR studies of chitosan blends. Thermochim Acta. 2003;396(1-2):153-166. [CrossRef]

- Jelić D, Liavitskaya T, Vyazovkin S. Thermal stability of indomethacin increases with the amount of polyvinylpyrrolidone in solid dispersion. Thermochim Acta. 2019;676:172-176. [CrossRef]

- Ben Osman Y, Liavitskaya T, Vyazovkin S. Polyvinylpyrrolidone affects thermal stability of drugs in solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2018;551(1-2):111-120. [CrossRef]

- Chang PR, Jian R, Yu J, Ma X. Fabrication and characterisation of chitosan nanoparticles/plasticised-starch composites. Food Chem. 2010;120(3):736-740. [CrossRef]

- Shetta A, Kegere J, Mamdouh W. Comparative study of encapsulated peppermint and green tea essential oils in chitosan nanoparticles: Encapsulation, thermal stability, in-vitro release, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;126:731-742. [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi Ghahfarokhi M, Barzegar M, Sahari MA, Azizi MH. Enhancement of thermal stability and antioxidant activity of thyme essential oil by encapsulation in Chitosan Nanoparticles. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. 2016;18:1781-1792.

- Govindan S, Nivethaa EAK, Saravanan R, Narayanan V, Stephen A. Synthesis and characterization of Chitosan–Silver nanocomposite. Applied Nanoscience (Switzerland). 2012;2(3):299-303. [CrossRef]

- Sankararamakrishnan N, Sanghi R. Preparation and characterization of a novel xanthated chitosan. Carbohydr Polym. 2006;66(2):160-167. [CrossRef]

- Chadha R, Kapoor VK, Kumar A. Analytical techniques used to characterize drug-polyvinylpyrrolidone systems in solid and liquid states - An overview. J Sci Ind Res (India). 2006;65(6):459-469.

- Salman, Ardiansyah, Nasrul E, Rivai H, Ben ES, Zaini E. Physicochemical characterization of amorphous solid dispersion of ketoprofen–polyvinylpyrrolidone K-30. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(2):209-212.

- Qi L, Xu Z, Jiang X, Hu C, Zou X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339(16):2693-2700. [CrossRef]

- Sizílio RH, Galvão JG, Trindade GGG, et al. Chitosan/pvp-based mucoadhesive membranes as a promising delivery system of betamethasone-17-valerate for aphthous stomatitis. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;190:339-345. [CrossRef]

- Epp J. X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques for materials characterization. Materials Characterization Using Nondestructive Evaluation (NDE) Methods. Published online January 1, 2016:81-124. [CrossRef]

- Hajimohammadi S, Momtaz H, Tajbakhsh E. Fabrication and antimicrobial properties of novel meropenem-honey encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles against multiresistant and biofilm-forming Staphylococcus aureus as a new antimicrobial agent. Vet Med Sci. 2024;10(3). [CrossRef]

- Onyango LA, Alreshidi MM. Adaptive Metabolism in Staphylococci: Survival and Persistence in Environmental and Clinical Settings. J Pathog. 2018;2018:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Peng Q, Tang X, Dong W, Sun N, Yuan W. A Review of Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Its Regulation Mechanism. Antibiotics. 2023;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual AM. Antibacterial action of nanoparticle loaded nanocomposites based on graphene and its derivatives: A mini-review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10). [CrossRef]

- Erejuwa OO, Sulaiman SA, Ab Wahab MS. Effects of honey and its mechanisms of action on the development and progression of cancer. Molecules. 2014;19(2):2497-2522. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi I El, Falcão SI, Harandou M, et al. Chemical, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory assessment of honey bee venom from apis mellifera intermissa. Antibiotics. 2021;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Qadirifard MS, Fathabadi A, Hajishah H, et al. Anti-Breast Cancer Potential of Honey: A Narrative Review. Vol 12.; 2022. www.oncoreview.pl5www.oncoreview.pl.

- Ryu S, Park S, Lee HY, Lee H, Cho CW, Baek JS. Biodegradable nanoparticles-loaded plga microcapsule for the enhanced encapsulation efficiency and controlled release of hydrophilic drug. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mandal MD, Mandal S. Honey: Its medicinal property and antibacterial activity. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1(2):154-160. [CrossRef]

- Arung ET, Ramadhan R, Khairunnisa B, et al. Cytotoxicity effect of honey, bee pollen, and propolis from seven stingless bees in some cancer cell lines. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(12):7182-7189. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).