Submitted:

27 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

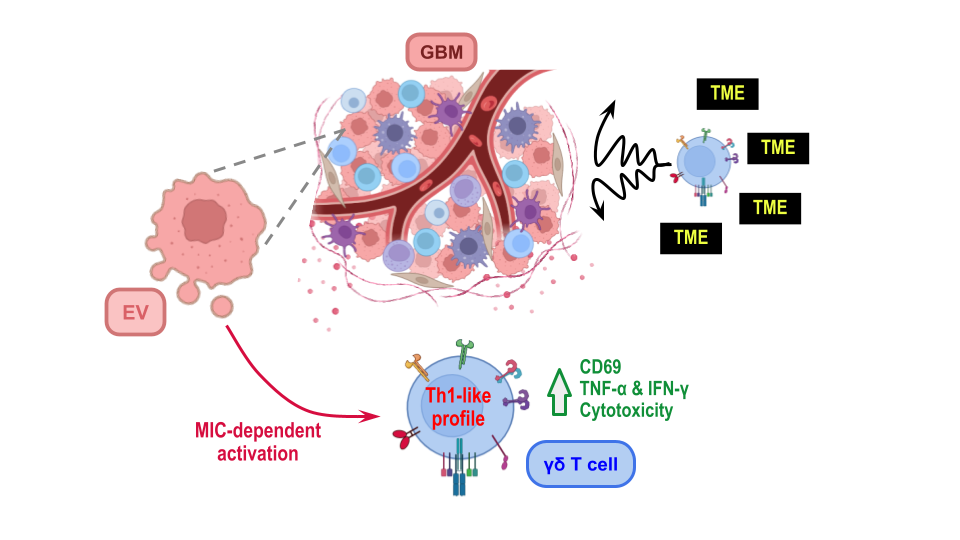

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

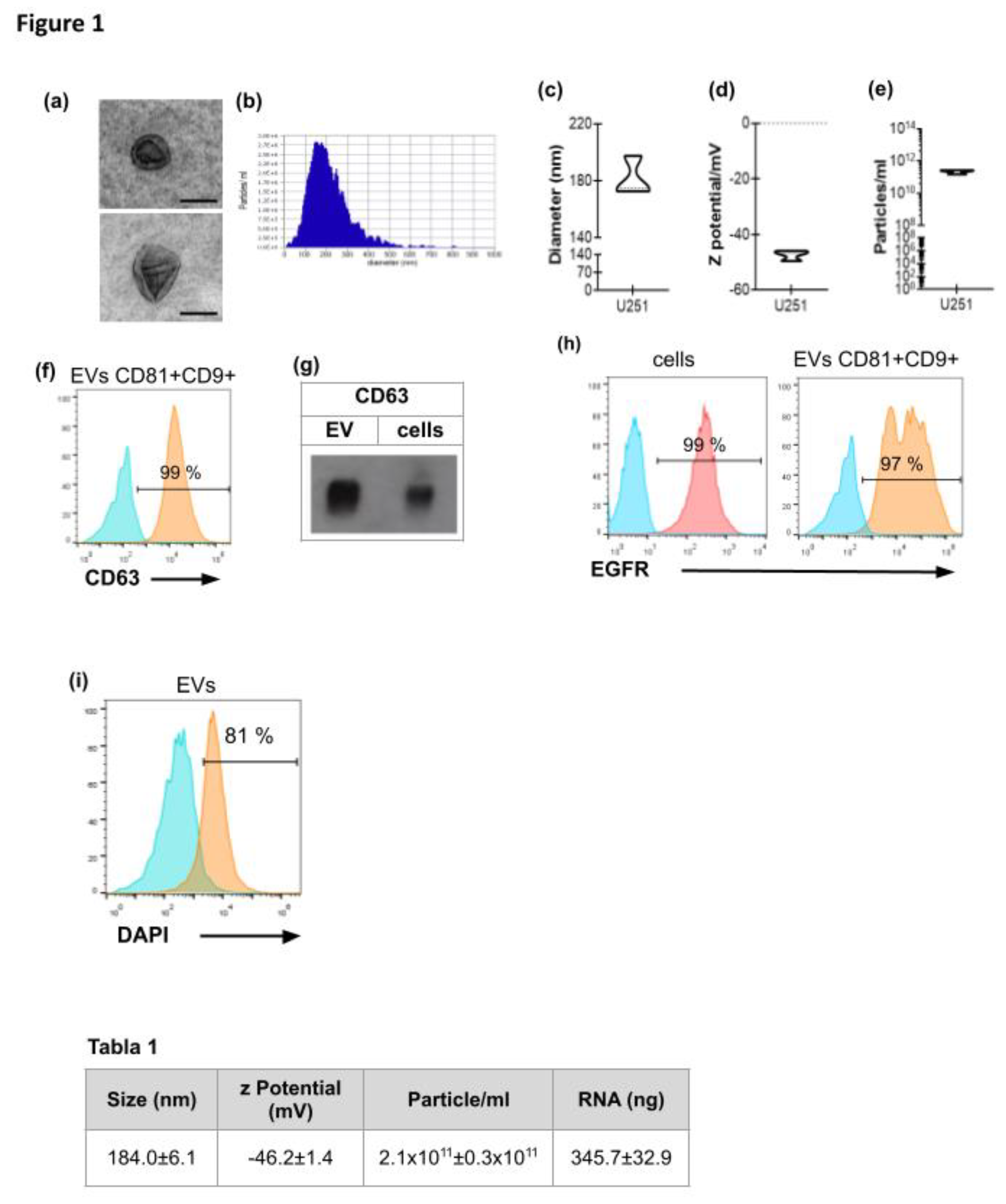

3.1. Characterization of EVs Derived from GBM Cell Line U251

- Table 1. Characterization of EVs derived from GBM cell line U251. EVs were obtained from confluent monolayers of 6x106 U251 cells after differential centrifugations. They were resuspended either in PBS for NTA analysis or in TRIzol for RNA quantification. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of the diameter, Z potential, particle concentration (n=4) and RNA concentration of EVs samples (n=3).

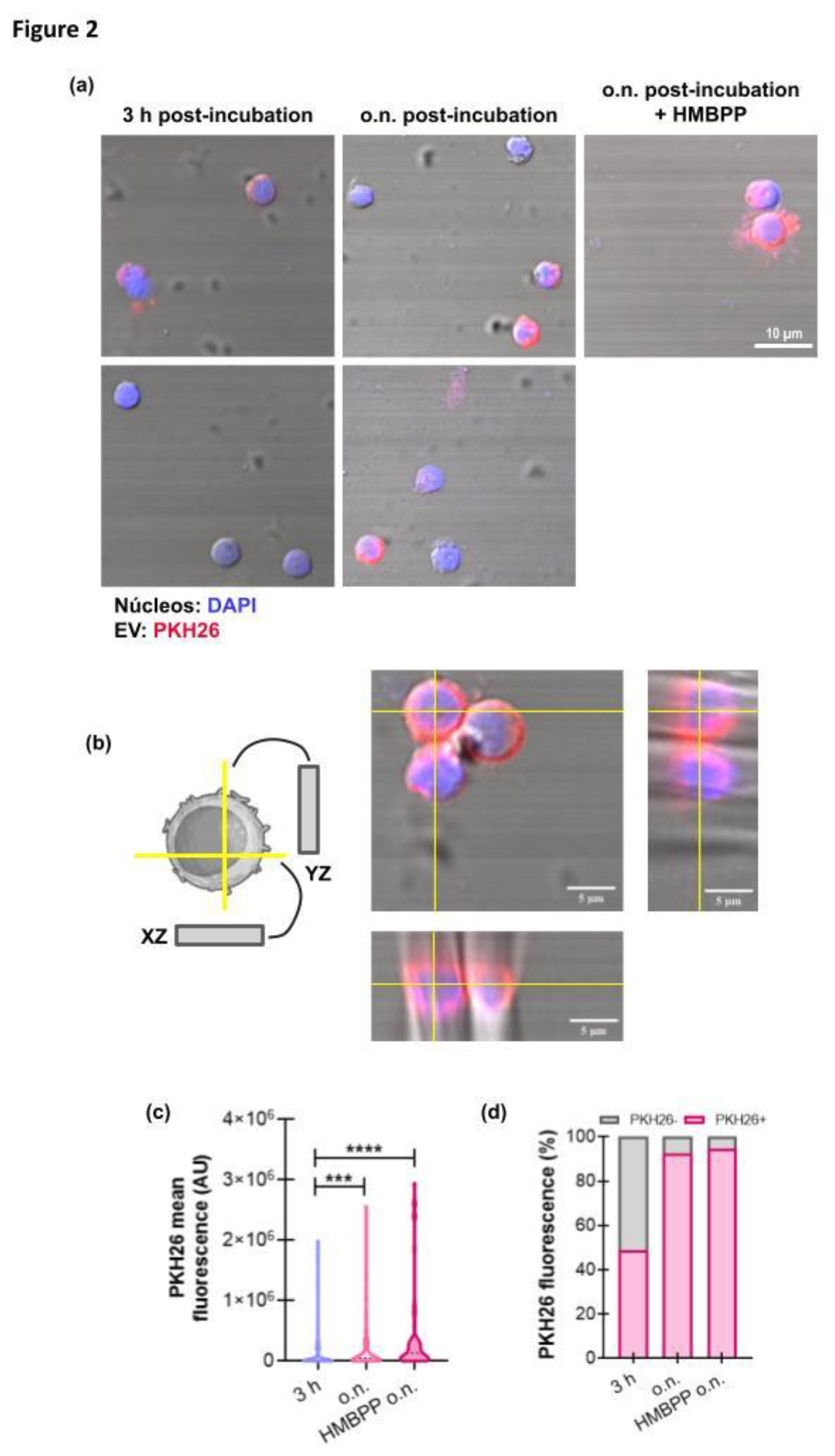

3.2. GBM−Derived EVs Interact with γδ T Cells

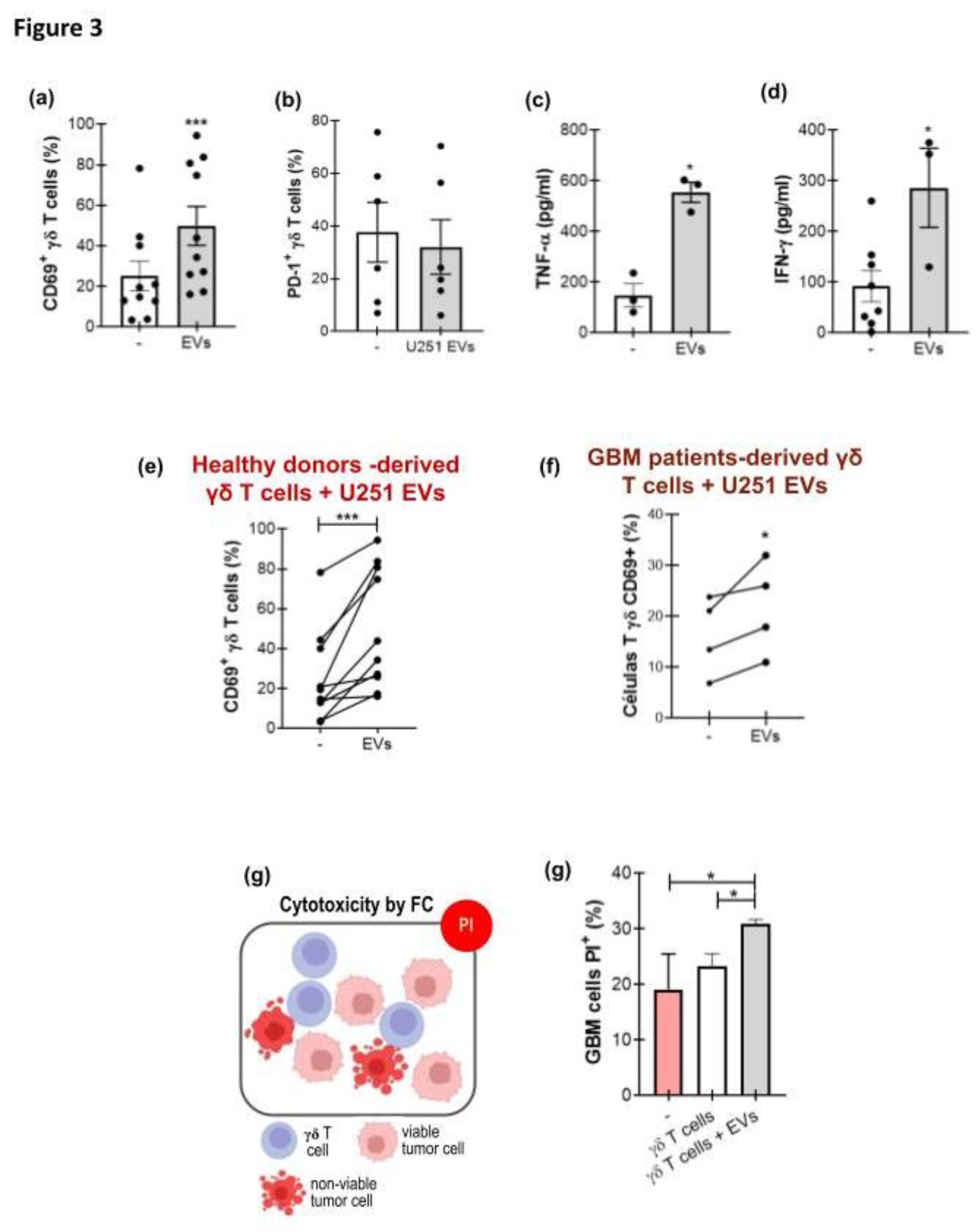

3.3. GBM-Derived EVs Activate γδ T Cells

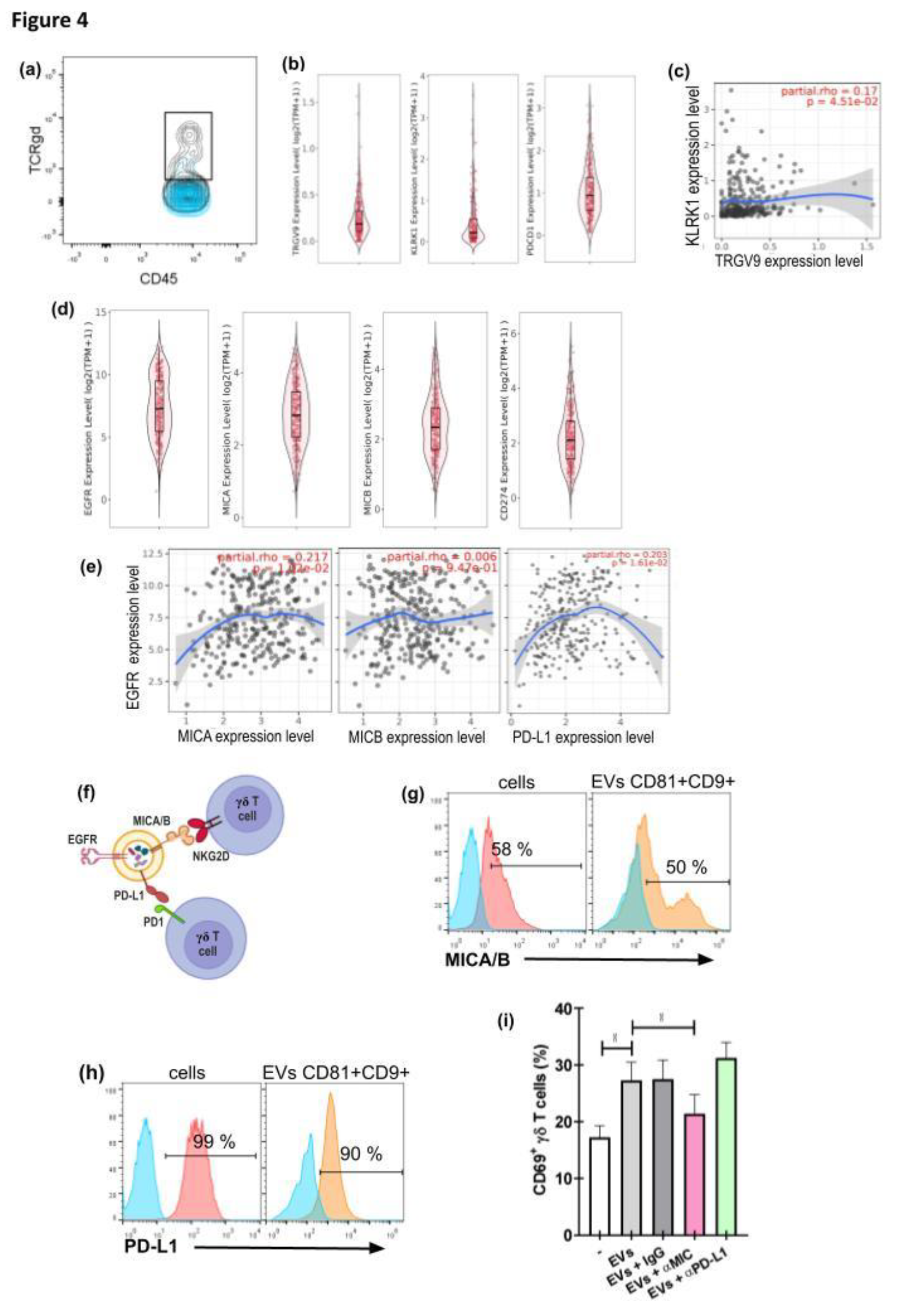

3.4. γδ T Cell Activation by GBM−Derived EVs Is Dependent on the Presence of MICA/B on the EVs

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Abbreviations

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 2021, 23, 1231–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, H. Current understanding of the human microbiome in glioma. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 781741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafii, S.; Ghouzlani, A.; Naji, O.; Ait Ssi, S.; Kandoussi, S.; Lakhdar, A.; et al. A2AR as a prognostic marker and a potential immunotherapy target in human glioma. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Patil, N.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro Oncol 2020, 22 Supplement_1, iv1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariah, R.; Pallavi, P.; Khush, J. Unlocking glioblastoma: breakthroughs in molecular mechanisms and next-generation therapies. Med Oncol 2025, 42(7), 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Hasegawa, R.; Imaida, K.; Hirose, M.; Asamoto, M.; Shirai, T. Concepts in multistage carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1995, 21(1–3), 105–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulhen, C.; Ssi, S.A.; Benthami, H.; Razzouki, I.; Lakhdar, A.; Karkouri, M.; et al. TMIGD2 as a potential therapeutic target in glioma patients. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1173518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouzlani, A..; Lakhdar, A.; Rafii, S.; Karkouri, M.; Badou, A. The immune checkpoint VISTA exhibits high expression levels in human gliomas and associates with a poor prognosis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira de Castro, J.; Gonçalves, C.S.; Hormigo, A; Costa, B.M. Exploiting the complexities of glioblastoma stem cells: Insights for cancer initiation and therapeutic targeting. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(15), 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassman, A.B.; Joanta-Gómez, A.E.; Pan, P.C.; Wick, W. Current usage of tumor treating fields for glioblastoma. Neurooncol Adv 2020, 2(1), vdaa069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Durden, D.L.; Van Meir, E.G.; Brat, D.J. “Pseudopalisading” necrosis in glioblastoma: a familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006, 65, 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, B.N.; Albert, G.P.; Halterman, M.W. Expression profiling of the MAP kinase phosphatase family reveals a role for DUSP1 in the glioblastoma stem cell niche. Cancer Microenviron 2017, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weenink, B.; French, P.J.; Sillevis Smitt, P.A. E.L.; Debets, R.; Geurts, M. Immunotherapy in glioblastoma: current shortcomings and future perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 2(3), 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzas, E.I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23(4), 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicle 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skog, J.; Würdinger, T.; van Rijn, S.; Meijer, D.H.; Gainche, L.; Curry, W.T.; et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol 2008, 10, 1470–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Lavieu, G.; Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.G.; Pink, R.C.; Erdbrügger, U.; Siljander, P.R.; Dellar, E.R.; Pantazi, P.; et al. In sickness and in health: The functional role of extracellular vesicles in physiology and pathology in vivo: Part II: Pathology. J Extracell Vesicle 2022, 11, e12190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankov, S.; Walker, P.R. Glioma-derived extracellular vesicles – far more than local mediators. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 679954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camussi, G.; Deregibus, M.C.; Bruno, S.; Cantaluppi, V.; Biancone, L. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int 2010, 78, 838–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marar, C.; Starich, B.; Wirtz, D. Extracellular vesicles in immunomodulation and tumor progression. Nat Immunol 2021, 22(5), 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, E.U.; Visus, C.; Szajnik, M.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Storkus, W.J.; Whiteside, T. L. Tumor-derived microvesicles promote regulatory T cell expansion and induce apoptosis in tumor-reactive activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2009, 183, 3720–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, V.; Fais, S.; Iero, M.; Lugini, L.; Canese, P.; Squarcina, P.; Zaccheddu, A.; et al. Human colorectal cancer cells induce T-cell death through release of proapoptotic microvesicles: role in immune escape. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, T.L. The role of tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) in shaping anti-tumor immune competence. Cells 2021, 10, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Long, X.; Liu, J.; Cheng, P. Glioblastoma microenvironment and its reprogramming by oncolytic virotherapy. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16, 819363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, B.; Harmak, Z.; Rghioui, M.; Kone, A-S.; El Ghanmi, A.; Badou, A. Decoding the secret of extracellular vesicles in the immune tumor microenvironment of the glioblastoma: on the border of kingdoms. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1423232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Ren, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. γδT cells, a key subset of T cell for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1562188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.B.; McLean, J.; Dialynas, D.P.; Strominger, J.L.; Smith, J.A.; Owen, F.L.; et al. Identification of a putative second T-cell receptor. Nature 1986, 322(6075), 145–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Lim, P.Y.; Tan, A.H-M. Gamma/delta T cells as cellular vehicles for anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol 2024, 14, 1282758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhi-Issa, N.; Manzano, D.T.; Pereiro Rodríguez, A.; Sanchez Ramon, S.; Perez Segura, P.; Ocaña, A. γδ T Cells: Game changers in immune cell therapy for cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17(7), 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Santos, B.; Serre, K.; Norell, H. γδ T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15(11), 683–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puan, K.J.; Jin, C.; Wang, H.; Sarikonda, G.; Raker, A.M.; Lee, H.K.; Samuelson, M.I.; Märker-Hermann, E.; Pasa-Tolic, L.; Nieves, E.; Giner, J. L.; Kuzuyama, T.; Morita, C.T. Preferential recognition of a microbial metabolite by human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Int Immunol 2007, 19(5), 657–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.V.; Lópes, A.C.; Silva-Santos, B. Tumor cell recognition by γδ T lymphocytes: T-cell receptor vs. NK-cell receptors. OncoImmunology 2013, 2(1), e22892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitadze, G.; Lettau, M.; Luecke, S.; Wang, T.; Janssen, O.; Fürst, D.; et al. NKG2D- and T-cell receptor-dependent lysis of malignant glioma cell lines by human γδ T cells: modulation by temozolomide and A disintegrin and metalloproteases 10 and 17 inhibitors. OncoImmunology 2016, 5(4), e1093276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, M.A.; Platten, M.; Lutz, S.Z.; Naumann, U.; Aulwurm, S.; Bischof, F.; et al. MICA/NKG2D-mediated immunogene therapy of experimental gliomas. Cancer Res 2003, 63(24), 8996–9006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisch, P.; Malkovsky, M.; Kovats, S.; Sturm, E.; Braakman, E.; Klein, B.; et al. Recognition by human Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells of a GroEL homolog on Daudi Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Science 1990, 250(4985), 1269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towstyka, N.Y.; Shiromizu, C.M.; Keitelman, I.A.; Sabbione, F.; Salamone, G.V.; Geffner, J.R.; Trevani, A.S.; Jancic, C.C. Modulation of γδ T-cell activation by neutrophil elastase. Immunology 2018, 153, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbione, F.; Gabelloni, M.L.; Ernst, G.; Gori, M.S.; Salamone, G.V.; Oleastro, M.; Trevani, A.S.; Geffner, J.R.; Jancic, C.C. Neutrophils suppress γδ T-cell function. Eur J Immunol 2014, 44, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, D.A.; Rosato, M.; Iturrizaga, J.; González, N.; Shiromizu, C.M.; Keitelman, I.A.; Coronel, J.V.; Gómez, F.D.; Amaral, M.M.; Rabadan, A.T.; Salamone, G.V.; Jancic, C.C. Glioblastoma cells potentiate the induction of the Th1-like profile in phosphoantigen-stimulated γδ T lymphocytes. J Neurooncol 2021, 153(3), 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, K.; Jo, A.; Giedt, J.; Vinegoni, C; Yang, K.S.; Peruzzi, P.; Chiocca, E.A.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lee, H.; Weissleder, R. Characterization of single microvesicles in plasma from glioblastoma patients. Neuro Oncol 2019, 21(5), 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G.; Clayton, A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2006, Chapter 3, Unit 3.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Arkesteijn, G. J.A.; Bremer, M.; Cimorelli, M.; Dignat-George, F.; Giebel, B.; Görgens, A.; Hendrix, A.; Kuiper, M.; Lacroix, R.; Lannigan, J.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Lozano-Andrés, E.; Rao, S.; Robert, S.; de Rond, L.; Tang, V.A.; Tertel, T.; Yan, X.; Wauben, M.; et al. A Compendium of single extracellular vesicle flow cytometry. J Extracell Vesicles 2023, 12(2), e12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhao, G.; Lu, Y.; Zuo, S.; Duan, D.; Luo, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, Q.; Li, T. TIMER3: an enhanced resource for tumor immune analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53(W1), W534–W541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles Erratum in: J Extracell Vesicles. 2024, 13(5):e12451. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12451. 2024, 13(2), e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).