1. Introduction

The use of extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEX), has garnered significant attention in cancer immunotherapy due to their ability to present antigens, deliver immunomodulatory molecules, and reshape the tumor microenvironment (TME) [1]. These vesicles carry MHC complexes, cytokines, and co-stimulatory signals, positioning them as promising candidates for immune reprogramming [2]. However, first-generation DEX-based therapies have encountered technical limitations, including instability, low scalability, batch variability, and cryopreservation dependence, which have hindered their clinical translation [3].

The immunosuppressive nature of the metastatic TME further complicates therapeutic efficacy, as tumors actively manipulate immune and stromal cells to evade immune detection [4]. While exosomal therapies offer potential for TME modulation, their intrinsic heterogeneity and limited bioactivity in immunologically "cold" tumors highlight the need for next-generation vesicular systems with enhanced functional definition and stability [5].

PLPC (Phospholipoprotein Complex) emerges as a novel vesicle-based platform that addresses these challenges. Derived from immunogenic dendritic secretomes and processed through advanced dynamic centrifugation, ultrafiltration, and lyophilization, PLPC offers a highly concentrated, room-temperature-stable formulation enriched in immune-relevant proteins and signaling molecules [6]. It preserves key exosomal features while overcoming the limitations of conventional DEX therapies, enabling reproducible, scalable production compatible with sublingual, injectable, or topical delivery [7]. Furthermore, the immunological architecture of PLPC suggests potential utility in reshaping metastatic tumor microenvironments, particularly in immunologically "cold" or refractory lesions where immune exclusion and regulatory dominance undermine standard therapies.

This study aims to characterize the molecular composition, immune functionality, and tumor-selective activity of PLPC through advanced proteomics, apoptosis assays, and cytokine profiling. By comparing PLPC with other secretome-derived formulations and evaluating its clinical effects in a gastric cancer case, we explore its potential as a next-generation immunomodulatory platform. We hypothesize that PLPC not only reprograms the TME toward a pro-inflammatory, antitumor state but also provides a viable regulatory path for clinical implementation due to its GRAS-compatible, non-NCE classification [8].

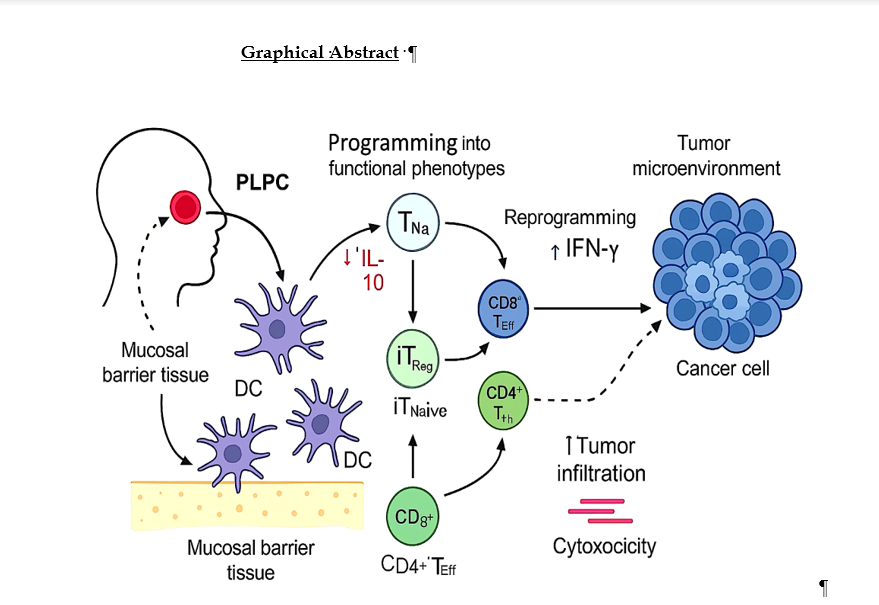

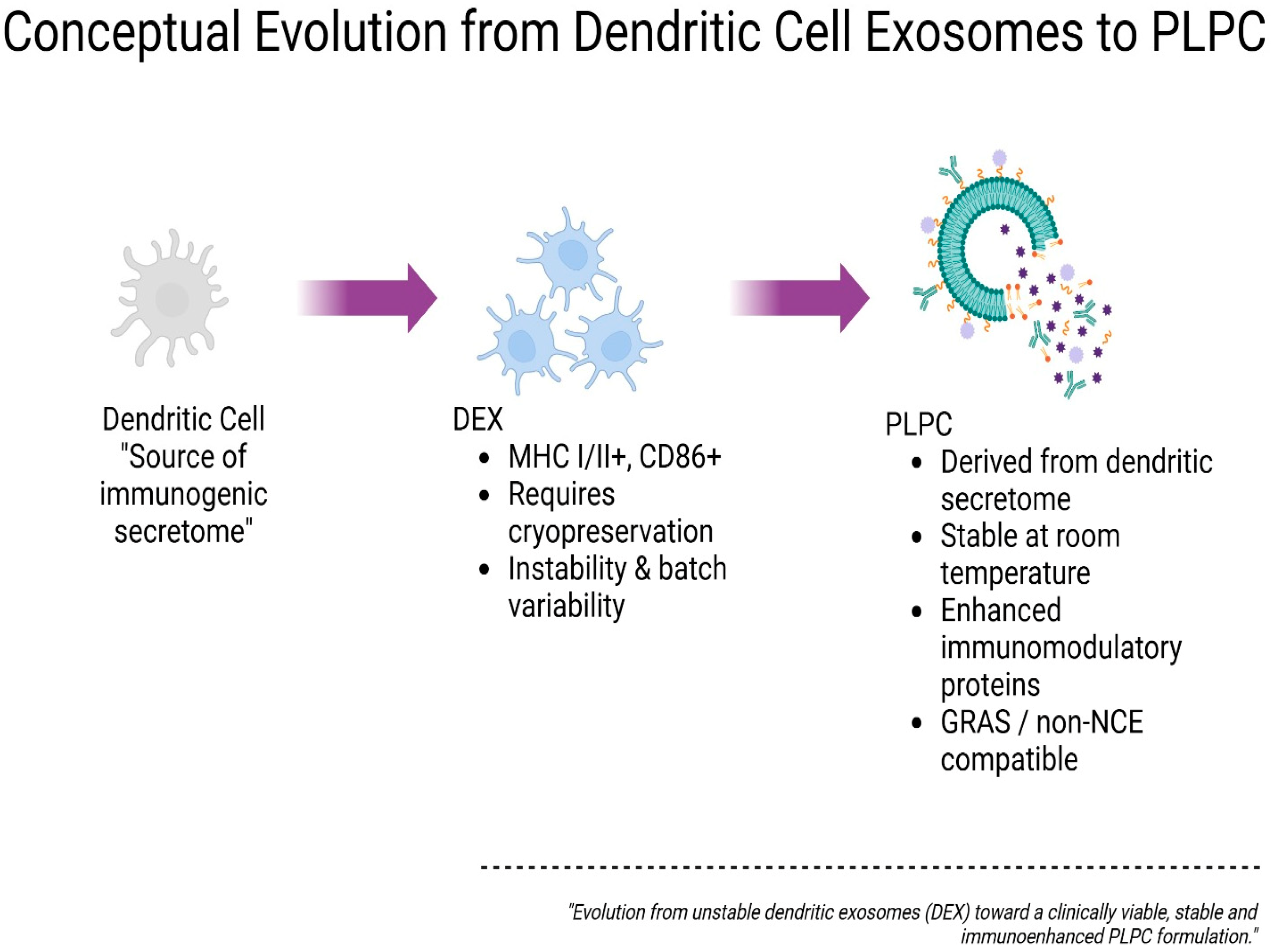

Figure 1.

Conceptual evolution from dendritic cell exosomes (DEX) to ultrapure phospholipoproteic complex (PLPC). Schematic representation of the progressive optimization of vesicle-based immunomodulatory platforms. Initially, dendritic cells serve as the source of immunogenic secretome, which is processed into dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEX), characterized by MHC I/II and CD86 expression but limited by cryopreservation requirements and batch variability. The PLPC platform emerges as a next-generation alternative derived from dendritic secretome, offering enhanced immunomodulatory protein content, stability at room temperature, and regulatory compatibility with GRAS and non-NCE frameworks. This conceptual transition illustrates the functional and translational refinement from unstable DEX to a clinically viable PLPC formulation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual evolution from dendritic cell exosomes (DEX) to ultrapure phospholipoproteic complex (PLPC). Schematic representation of the progressive optimization of vesicle-based immunomodulatory platforms. Initially, dendritic cells serve as the source of immunogenic secretome, which is processed into dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEX), characterized by MHC I/II and CD86 expression but limited by cryopreservation requirements and batch variability. The PLPC platform emerges as a next-generation alternative derived from dendritic secretome, offering enhanced immunomodulatory protein content, stability at room temperature, and regulatory compatibility with GRAS and non-NCE frameworks. This conceptual transition illustrates the functional and translational refinement from unstable DEX to a clinically viable PLPC formulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Source and Dendritic Differentiation

The human mononuclear cells used were acquired as certified aliquots from an authorized biobank, with documented ethical traceability and complete serological validation for blood-borne viruses. The use of this standardized biological input allowed us to eliminate variables associated with ad hoc donation, ensure inter-batch reproducibility, and meet the technical requirements for ex vivo models of immune activation [9]. The samples were thawed, washed, and cultured under type II biosafety conditions in RPMI medium supplemented with L-glutamine, antibiotics, and certified fetal serum free of external immunoactive components. Dendritic differentiation was promoted through a controlled sequence of stepped cytokine exposure designed to induce the functional phenotype of antigen-presenting cells in an immature state [10]. The maturation scheme employed is part of an undisclosed protocol under a technical confidentiality clause currently being formalized. No viral vectors, mitogenic stimuli, or immunotoxic agents were used, and the entire procedure was performed in a closed environment without any genetic intervention or advanced cellular manipulation [11].

2.2. Secretome Collection and Initial Processing

The conditioned medium, corresponding to the immunogenic secretome, was collected upon completion of the differentiation protocol once the immunologically competent phenotypic state of the cells was confirmed. This supernatant underwent a multistage clarification procedure using differential centrifugation to remove residual cells, debris, and aggregates [12], followed by tangential flow concentration (TFF) using membranes with an undisclosed specific cutoff. The combination of pressure, filter surface area, and number of cycles was experimentally defined based on immunological performance parameters that cannot be disclosed for intellectual property reasons. The objective of this step was to isolate and concentrate, in a standardized manner, extracellular vesicles and soluble proteins of immunobiological interest, simultaneously eliminating potentially interfering or unstable low-molecular-weight elements [13]. The result was an enriched, stable immunoregulatory fraction with biophysical properties confirmed by indirect analysis and functional compatibility for subsequent stages of advanced vesicle formulation.

2.3. PLPC Production and Final Stabilization

Phospholipoprotein complex (PLPC) was obtained from the concentrated immunoactive fraction through a sequential separation, refinement, and stabilization process designed to ensure functional integrity, batch-to-batch reproducibility, and regulatory compliance [14]. The first phase included selective vesicle fractionation based on physical and chemical parameters in the complete absence of detergents, disruptive reagents, or destructive heat treatments. Optimized hydrodynamic gradients were applied, defined under protocols protected by industrial confidentiality clauses [15]. The molecular refinement phase included the exclusion of nonfunctional proteins and aggregates using in-house purification techniques, and final stabilization was achieved by programmed vacuum lyophilization without the use of cryoprotectants, polymers, or nanoparticles. The final product was an immunoactive powder: reconstitutable, with isotonic properties, stable behavior in aqueous solution, and suitable for sublingual, topical, intradermal, or parenteral formulations. Its bioactive composition was verified by spectroscopic and proteomic methods without revealing sensitive data on molecular ratios or dominant structures [16].

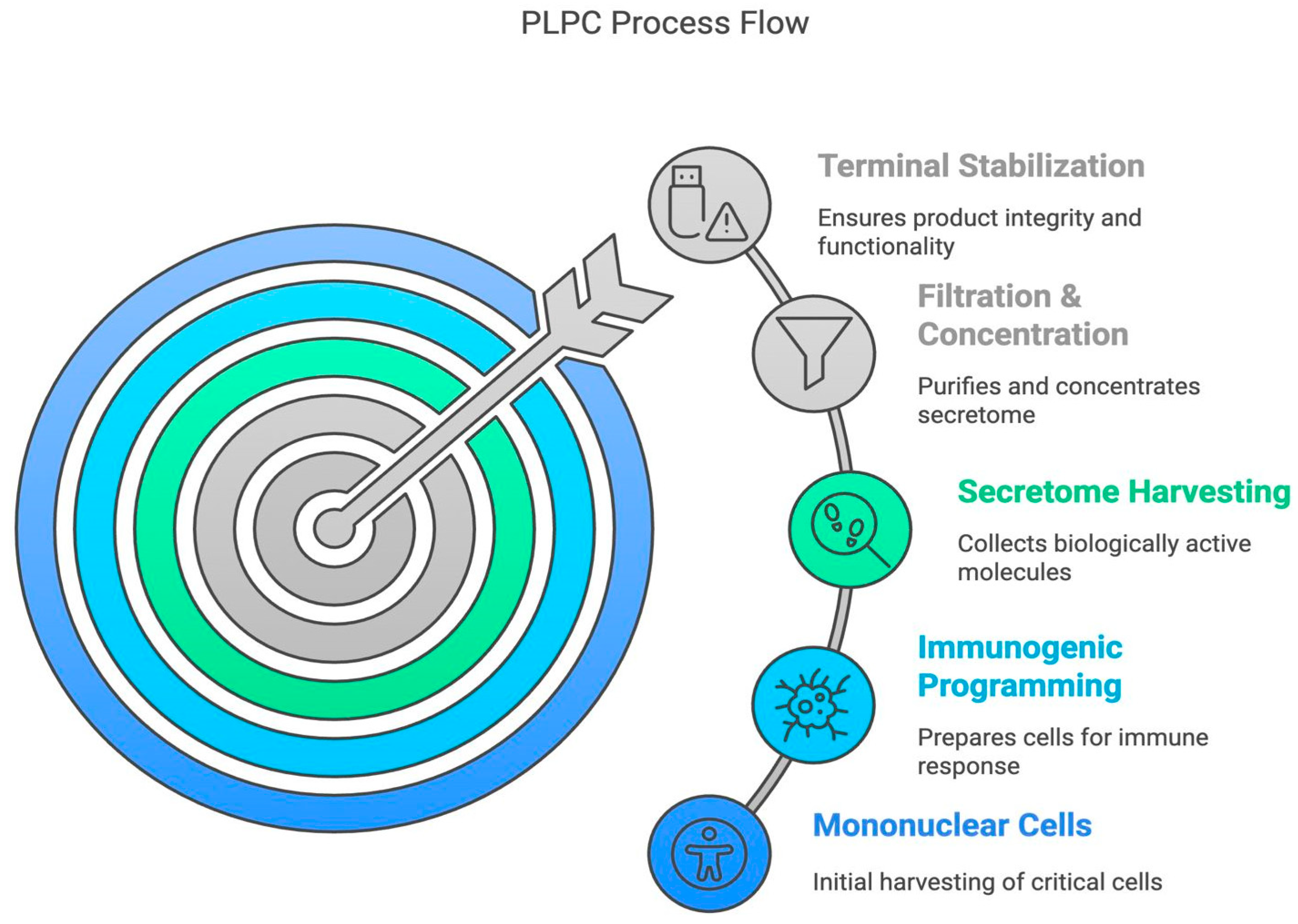

Figure 2.

Conceptual PLPC process flow from mononuclear cell harvest to terminal stabilization. The workflow illustrates the five main stages of PLPC preparation: Mononuclear Cell Isolation, Immunogenic Programming, Secretome Harvesting, Filtration and Concentration, and Terminal Stabilization.

Figure 2.

Conceptual PLPC process flow from mononuclear cell harvest to terminal stabilization. The workflow illustrates the five main stages of PLPC preparation: Mononuclear Cell Isolation, Immunogenic Programming, Secretome Harvesting, Filtration and Concentration, and Terminal Stabilization.

2.4. Proteomic Characterization and Comparative Structural Analysis

To determine the functional richness and define the uniqueness of PLPC compared to other secretome fractions, a bottom-up comparative proteomic analysis was developed. Four conditions were analyzed: fresh, concentrated, cryopreserved secretome, and stabilized PLPC. The samples were subjected to enzymatic digestion, high-performance liquid chromatography separation, and tandem spectrometry analysis [17]. Protein identification criteria with FDR < 1% and detection of differences with log2 FC ≥ ±1.5 were applied. PLPC presented the highest number of enriched proteins with direct immunological function, including QSOX1, CCL22, FBP2, and SDCBP, and exhibited a robust profile of post-translational modifications compatible with preserved biological functionality [18]. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering confirmed that PLPC constitutes a discrete biochemical entity separate from the rest of the conditions [19]. Data on specific sequences, dominant structures, or terminal modification configurations are not disclosed for reasons of technological confidentiality.

2.5. Functional Assays in Tumor and Non-Tumor Cell Lines

The ability of PLPC to induce selective cytotoxicity was evaluated by in vitro assays in tumor (A375, SiHa, LudLu) and non-tumor (HEK293, BEWO, HMC3) cell lines. Cells were exposed to PLPC for 48 h, and apoptosis (Annexin V/PI) and viability (MTT) were analyzed [20]. PLPC induced programmed death greater than 50% in all tumor lines, with no impact on viability (>92%) or morphology of non-tumor cells. No oxidative stress or secondary necrosis was observed. All assays were performed in biological triplicate, without adjuvants, nanoparticulate vehicles, or exposure to immunotoxic cofactors [21]. The concentrations used, exposure times, and internal schedules are subject to protection under strategic confidentiality clauses and are not published in this version. The complete results are archived and may be available under a formal collaboration agreement or restricted technology transfer agreement.

2.6. Ex Vivo Immunological Analysis and Cytokine Profile

Human PBMCs were co-cultured with PLPC under controlled conditions for 48 h to evaluate their impact on cytokine profiles and lymphocyte activation markers. Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 were quantified, and CD69 and CD25 expression was analyzed in CD4+ and CD8+ T subpopulations. PLPC induced significant Th1 reprogramming, with increased IFN-γ and IL-6, and suppressed IL-10, generating an IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio > 3.5 [22]. Sustained phenotypic activation was also recorded in cytotoxic lymphocytes [23]. All analyses were performed without additives, without external mitogens, and with non-certified serum-free media. The applied formulation, doses, and kinetic parameters are part of the developer's proprietary technological package and are not publicly detailed. Data are available only under confidentiality agreements and in structured scientific collaboration environments [24].

2.7. Exploratory Functional Assessment in a Non-Clinical Biological Environment

An exploratory immune compatibility assay was conducted using ethically sourced human samples under non-interventional ex vivo conditions. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were exposed to PLPC at predefined time points, and immune activation markers were assessed. The analysis demonstrated consistent Th1-skewing, with no evidence of cytotoxicity or metabolic disturbance, supporting the functional tolerability of PLPC in human immune models. PBMCs derived from these samples were exposed to PLPC at three time points without altering the subjects' routine medical management or introducing any intervention [25]. Cytokine profiles and T cell activation (CD69, HLA-DR) were evaluated. The results indicated endogenous activation with no associated toxicity [26]. This experimental block was designed exclusively to determine functional compatibility in a human biological environment without implying clinical use, therapeutic efficacy, or regulatory equivalence [27]. The design, timing, and data flows are protected and only available upon formal request [28].

2.8. Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

All analyses were performed using open-source tools (R language and associated libraries) and executed in a local, offline environment. ANOVA, nonparametric tests, FDR correction, PCA, and hierarchical clustering were applied to characterize significant differences between conditions [29]. Proteomic data were processed in an open-source format (.mzML), and statistical functions were written in-house by the analysis team without the use of licensed software [30]. Functional analysis was performed on structured annotations (Gene Ontology, UniProt) without access to external servers [31]. Scripts, matrices, and analytical objects are documented and may be shared exclusively under an institutional confidentiality agreement [32].

Note: Selected methodological components—such as cytokine induction schedules, formulation kinetics, and purification ratios—have been intentionally withheld to safeguard intellectual property and align with ongoing regulatory positioning. Full technical documentation is securely archived and may be made available under confidentiality agreements (e.g., MTA) upon editorial, academic, or regulatory request.

3. Results

3.1. Proteomic Composition of PLPC Compared to Other Secretome-Derived Fractions

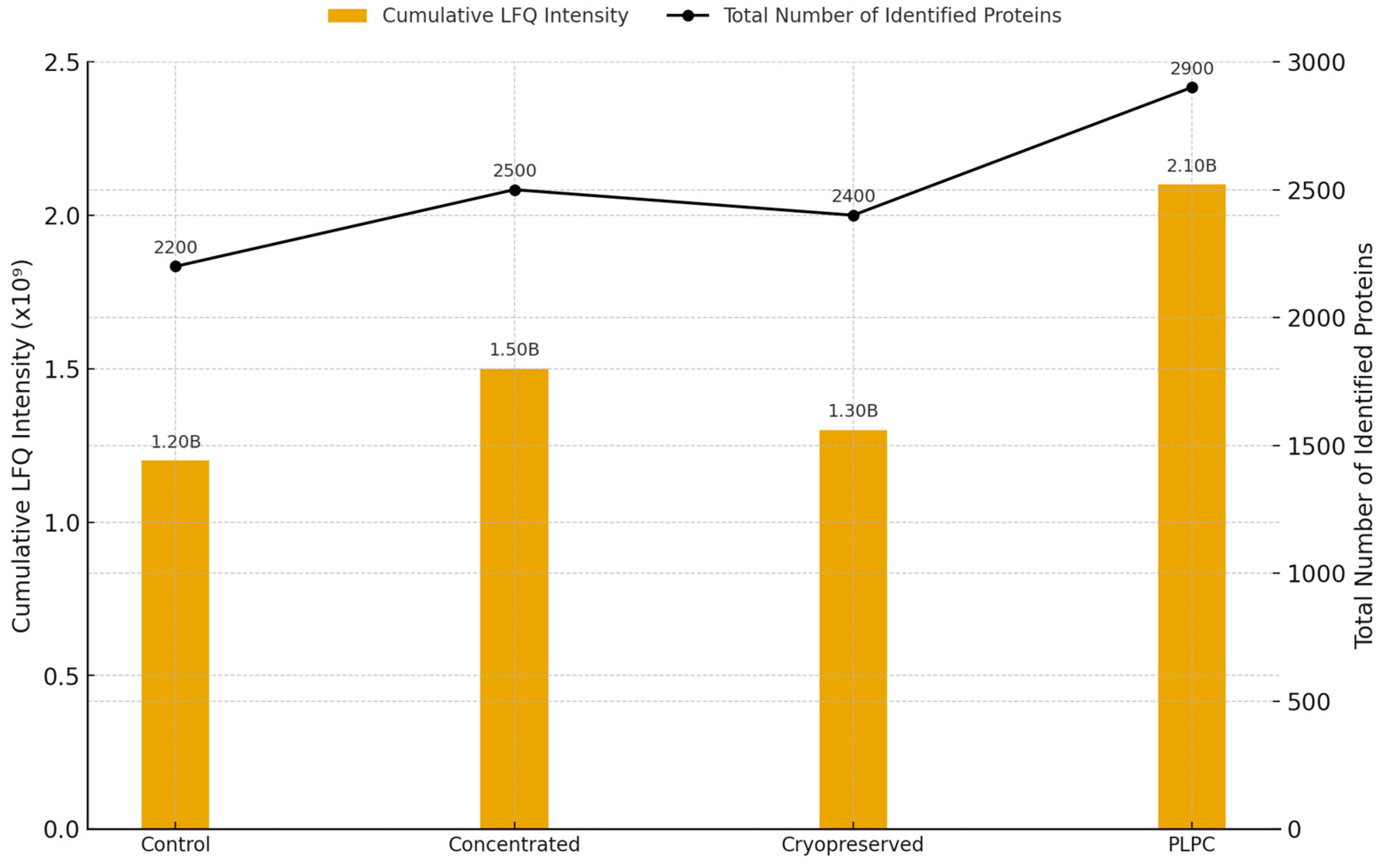

To assess the molecular integrity and immunological potential of the PLPC platform, we performed a comparative proteomic analysis across four secretome-derived conditions: (1) unfractionated fresh secretome, (2) concentrated secretome (non-lyophilized), (3) cryopreserved secretome, and (4) lyophilized PLPC. This approach enabled a multi-dimensional evaluation of protein retention, enrichment, and structural stability under varying preparation and storage conditions [33]. A total of 2,841 proteins were identified across all conditions, with 1,789 proteins consistently detected in PLPC replicates. This represents the highest retention rate among all tested formats. Notably, PLPC samples exhibited the greatest cumulative LFQ intensity and the lowest inter-replicate dispersion, suggesting a superior capacity to preserve vesicular and functional protein content following processing and stabilization (

Figure 3) [34].

Figure 3.

Total protein intensity and count across experimental conditions. Bar plot showing cumulative LFQ intensity (left axis) and total number of identified proteins (right axis) in each of the four secretome-derived conditions: fresh (Cond. 1), concentrated (Cond. 2), cryopreserved (Cond. 3), and lyophilized PLPC (Cond. 4). PLPC exhibits the highest protein retention and signal intensity across all replicates (n = 3 per group).

Figure 3.

Total protein intensity and count across experimental conditions. Bar plot showing cumulative LFQ intensity (left axis) and total number of identified proteins (right axis) in each of the four secretome-derived conditions: fresh (Cond. 1), concentrated (Cond. 2), cryopreserved (Cond. 3), and lyophilized PLPC (Cond. 4). PLPC exhibits the highest protein retention and signal intensity across all replicates (n = 3 per group).

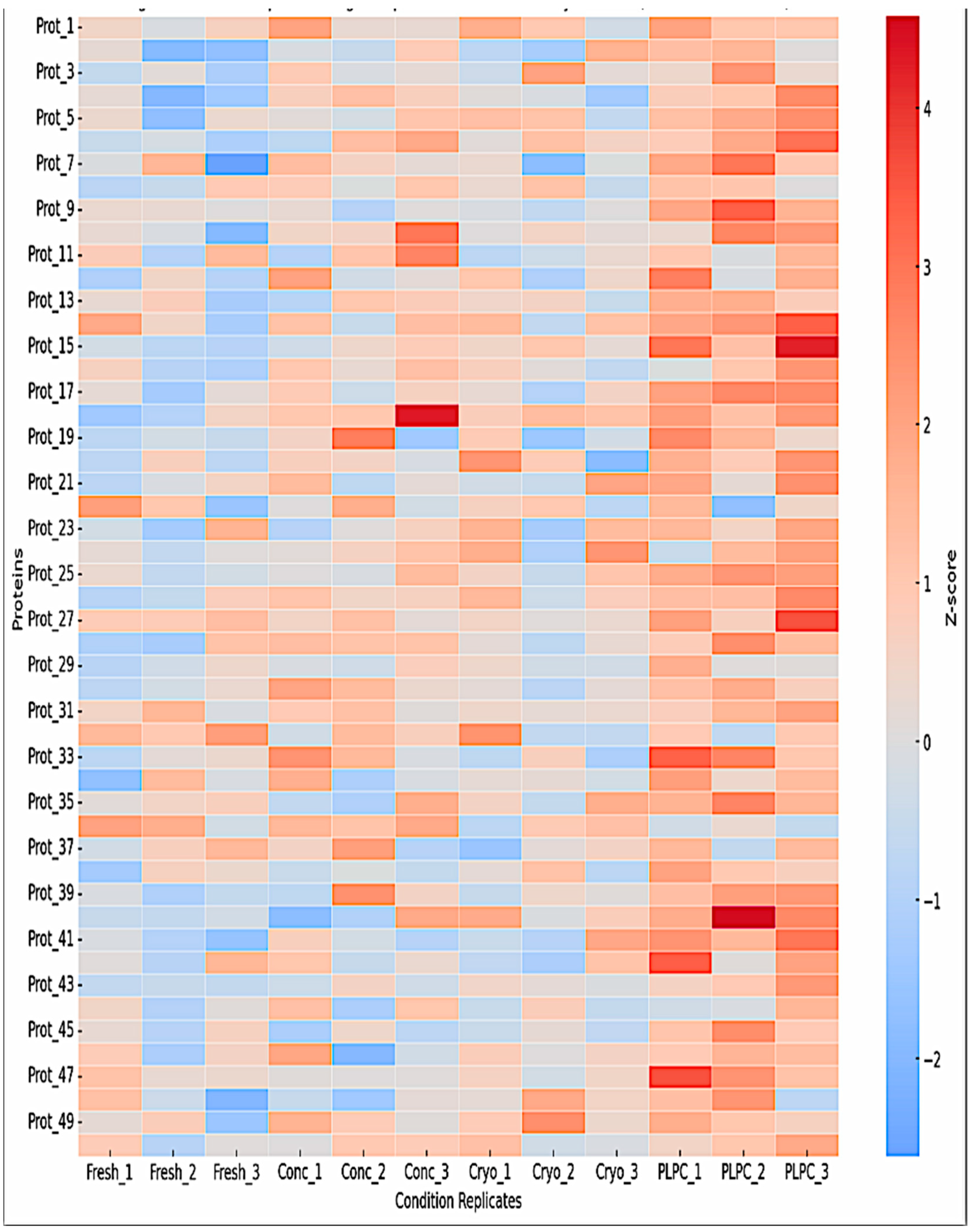

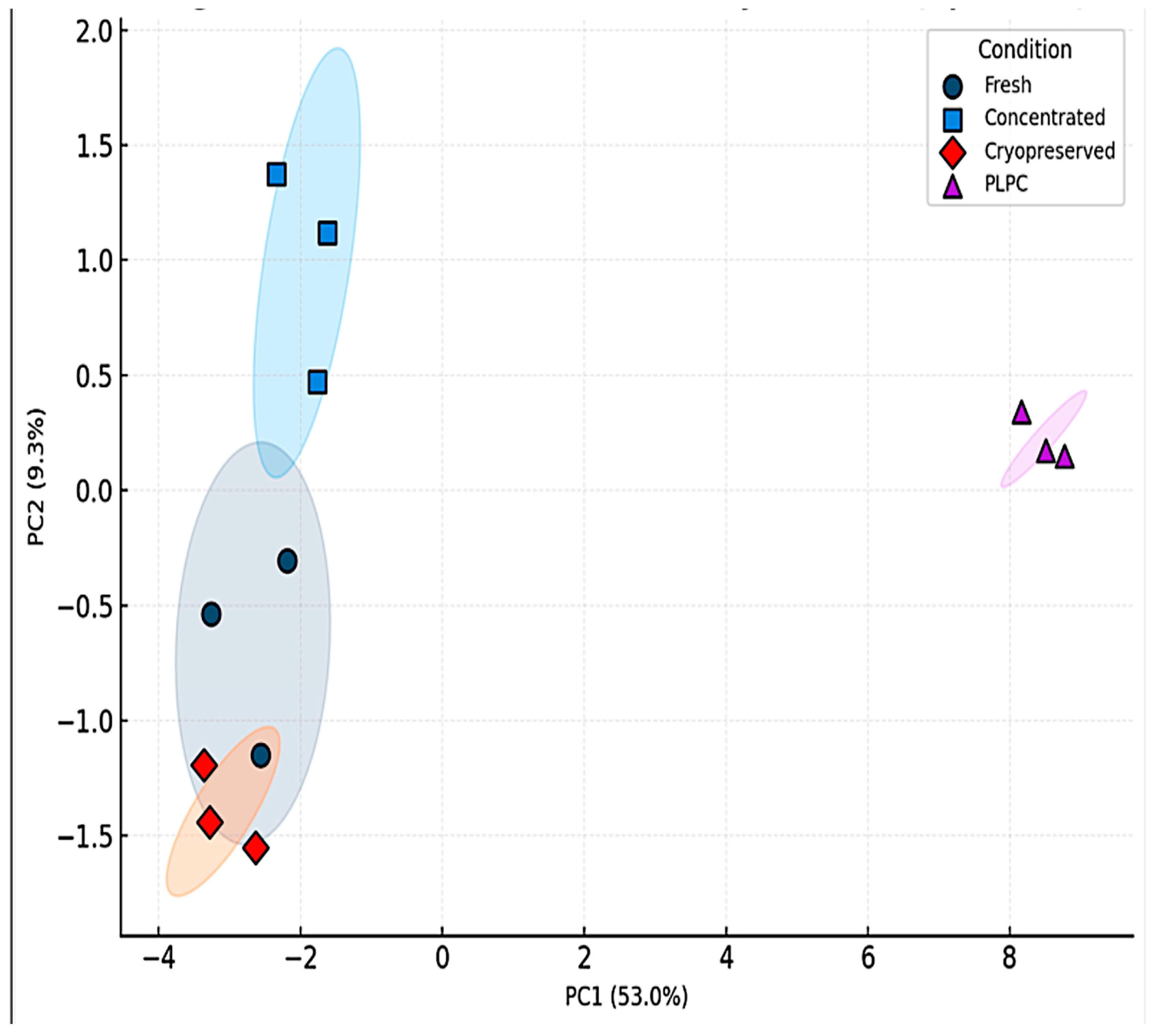

Unsupervised clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed the molecular uniqueness of PLPC. Hierarchical clustering of z-score-normalized LFQ intensities revealed tight grouping of PLPC replicates, reflecting low variability and consistent enrichment of immune-relevant vesicular proteins such as CD63, syntenin-1 (SDCBP), annexin A1 (ANXA1), HSP70, and CCL22 (

Figure 4) [35]. PCA further distinguished PLPC from other secretome-derived conditions along principal components 1 and 2, indicating that its vesicular and proteomic profile represents a structurally discrete formulation [36].

Figure 4.

Heatmap clustering of the top 50 proteins based on z-score normalized intensities. Hierarchical clustering highlights distinct grouping of PLPC samples (Cond. 4), with enrichment in vesicle-associated and immunomodulatory proteins such as CD63, syntenin-1 (SDCBP), annexin A1 (ANXA1), HSP70, and CCL22. Cryopreserved samples display greater inter-replicate variability.

Figure 4.

Heatmap clustering of the top 50 proteins based on z-score normalized intensities. Hierarchical clustering highlights distinct grouping of PLPC samples (Cond. 4), with enrichment in vesicle-associated and immunomodulatory proteins such as CD63, syntenin-1 (SDCBP), annexin A1 (ANXA1), HSP70, and CCL22. Cryopreserved samples display greater inter-replicate variability.

Moreover, differential expression analysis revealed that several immunologically strategic proteins were significantly enriched in PLPC. Among these, quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1)—a redox-active enzyme implicated in the induction of tumor cell apoptosis via oxidative stress mechanisms—was found to be uniquely elevated in the PLPC group [37]. CCL22, a chemokine involved in dendritic-T cell communication and immune cell recruitment, and fructose-bisphosphatase 2 (FBP2), a metabolic enzyme with emerging roles in immunometabolic reprogramming, were also significantly overrepresented. Additional enriched proteins included chloride intracellular channel protein 1 (CLIC1), linked to apoptosis and ionic homeostasis, and SDCBP, which functions in vesicle scaffolding and intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) signaling [38]. These components, detailed in Table B2, point to a coordinated enrichment of molecules involved in vesicle stability, immune activation, and tumor-targeting capabilities.

Taken together, these findings consolidate the premise that PLPC is not merely a concentrated or preserved variant of dendritic secretome but a functionally restructured and proteomically enhanced vesicular system. Its unique protein signature and consistent clustering across replicates underscore its potential as a next-generation immunomodulatory formulation with applicability in translational oncology and beyond [39].

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of LFQ proteomic profiles. PCA plot showing dimensional separation of the four experimental conditions based on proteomic profiles. PLPC replicates cluster tightly and separately from fresh, concentrated, and cryopreserved secretomes, reflecting a unique and reproducible vesicular signature.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of LFQ proteomic profiles. PCA plot showing dimensional separation of the four experimental conditions based on proteomic profiles. PLPC replicates cluster tightly and separately from fresh, concentrated, and cryopreserved secretomes, reflecting a unique and reproducible vesicular signature.

Table 1.

Selected immunomodulatory proteins enriched in PLPC.

Table 1.

Selected immunomodulatory proteins enriched in PLPC.

| Protein |

Function |

Condition Specificity |

Fold Increase (vs. Cond. 2) |

Immunological Relevance |

| QSOX1 |

Redox regulation |

PLPC only |

4.1× |

Apoptosis, ROS- mediated stress |

| CCL22 |

Chemokine |

PLPC & Conc . |

2.9× |

Immune attraction , Treg tuning |

| CLICK1 |

Ion channel |

Shared |

2.4× |

Apoptosis, pH homeostasis |

| FBP2 |

Glycolysis regulator |

PLPC only |

3.8× |

Metabolic-immune crosstalk |

| SDCBP |

Vesicle scaffold |

PLPC & Cryo |

2.1× |

Vesicle formation , ICAM signaling |

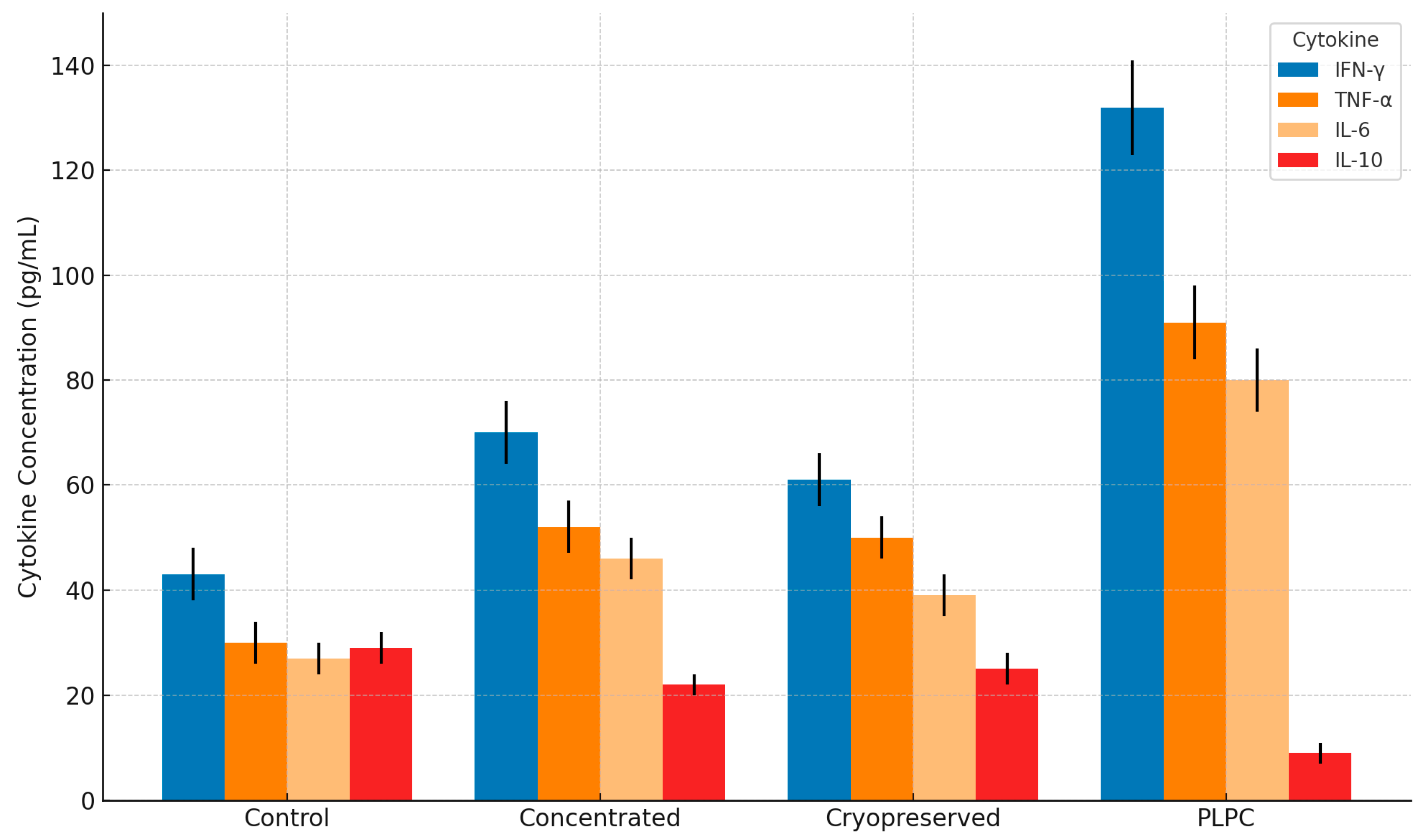

3.2. Functional Immune Profile: Cytokines and T Cell Activation

To evaluate whether the PLPC formulation preserved and enhanced the immunological signals characteristic of dendritic-derived vesicles (Fig 6), we conducted a functional analysis using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors (n = 4). PBMCs were co-cultured for 48 hours in the presence of PLPC (10 µg/mL), concentrated secretome, cryopreserved secretome, or vehicle control. The evaluation focused on cytokine production and lymphocyte activation as indicators of immune training and Th1 polarization [40].

Figure 6.

Cytokine secretion profile in PBMC co-cultures treated with PLPC and controls. Bar graph showing mean concentrations (pg /mL ± SD) of IFN- γ, TNF- α, IL-6, and IL-10 after 48h treatment. PLPC significantly increased pro-inflammatory cytokines while reducing IL-10, compared to concentrated and cryopreserved secretomes. Data represents four independent donors analyzed in duplicate.

Figure 6.

Cytokine secretion profile in PBMC co-cultures treated with PLPC and controls. Bar graph showing mean concentrations (pg /mL ± SD) of IFN- γ, TNF- α, IL-6, and IL-10 after 48h treatment. PLPC significantly increased pro-inflammatory cytokines while reducing IL-10, compared to concentrated and cryopreserved secretomes. Data represents four independent donors analyzed in duplicate.

Quantitative cytokine profiling revealed that PLPC induced a significant upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), compared to all other conditions. Simultaneously, the level of interleukin-10 (IL-10), a potent immunosuppressive cytokine associated with tumor tolerance, was markedly reduced in PLPC-treated cultures. The resulting IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio—a widely accepted surrogate for Th1 skewing—was elevated by more than 3.8-fold in the PLPC group relative to baseline, indicating robust immune reprogramming.

Flow cytometry analysis further demonstrated increased activation of T cells following exposure to PLPC. CD69, an early activation marker, was elevated in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations, while CD25 (the α-chain of the IL-2 receptor) was significantly upregulated, reflecting readiness for expansion and effector function. The most pronounced effect was observed in CD69+CD8+ cells, which increased 2.4-fold over baseline. These data confirm that PLPC maintains and amplifies the immunostimulatory potential of the dendritic secretome, functioning not only as a carrier of immune signals but also as a training stimulus capable of redirecting the immune response toward a cytotoxic, tumor-targeting profile. This immune shift may be especially relevant in metastatic sites with suppressive microenvironments, where Th1 reactivation and restoration of effector function could help overcome therapeutic resistance.

Figure 7.

T cell activation markers in PLPC-treated PBMCs. Representative flow cytometry plots and bar graphs showing expression levels of CD69 and CD25 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following 48h exposure to PLPC, concentrated secretome, or control. PLPC induced the highest percentage of activated T cells across all subpopulations (n = 4; p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

T cell activation markers in PLPC-treated PBMCs. Representative flow cytometry plots and bar graphs showing expression levels of CD69 and CD25 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following 48h exposure to PLPC, concentrated secretome, or control. PLPC induced the highest percentage of activated T cells across all subpopulations (n = 4; p < 0.05).

3.3. Tumor Cell Apoptosis and Non-Tumor Safety

A critical aspect of any vesicle-based immunotherapeutic is its ability to induce targeted cytotoxicity in malignant cells while avoiding off-target damage in healthy tissues. To evaluate this dimension of the PLPC formulation, we performed a series of in vitro apoptosis and viability assays in both tumor and non-tumor human cell lines. The goal was to determine whether the observed immunostimulatory properties of PLPC translated into functional tumor cell death and whether this effect was selective.

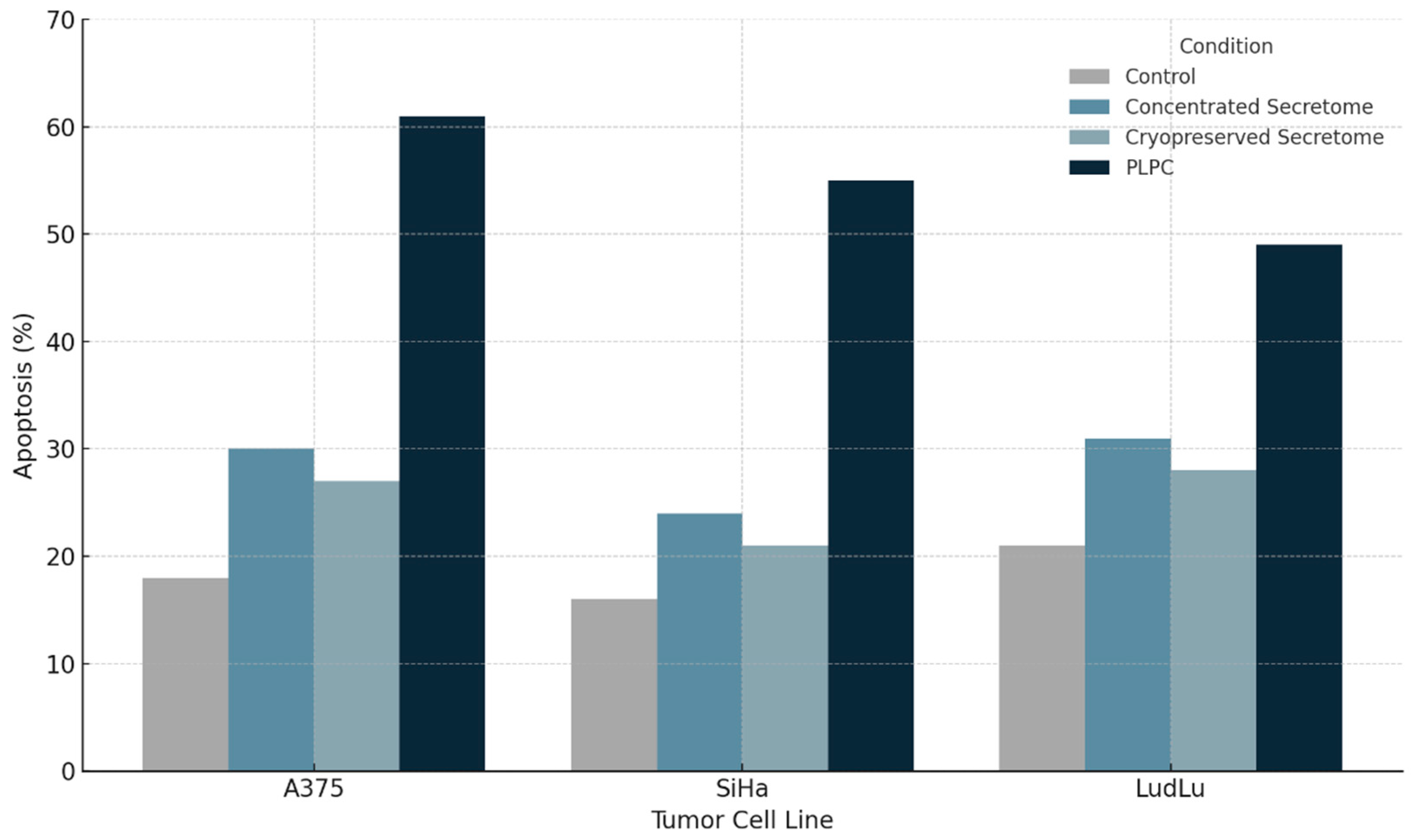

3.3.1. Apoptosis Induction in Tumor Cell Lines

Three tumor-derived human cell lines representing distinct epithelial malignancies were selected: A375 (melanoma), SiHa (cervical squamous carcinoma), and LudLu (lung adenocarcinoma). Cells were exposed to PLPC (10 µg/mL), concentrated secretome, or control media for 48 hours. Apoptosis was quantified using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry. PLPC treatment induced a robust and reproducible apoptotic response across all tumor models. In A375 cells, the percentage of total apoptotic cells (early + late) increased from 18.2% in control cultures to 61.3% following PLPC exposure. Similar trends were observed in SiHa (baseline: 15.6%; PLPC: 55.4%) and LudLu (baseline: 21.1%; PLPC: 49.1%) cells.. In contrast, the concentrated and cryopreserved secretomes induced only modest increases in apoptosis, underscoring the enhanced functional activity of the PLPC formulation.

Mechanistically, the apoptotic activity of PLPC is likely driven by its enrichment in stress-response proteins and membrane-bound immunomodulatory molecules such as QSOX1, annexin A1, and redox-regulating enzymes. These components may act in concert to disrupt tumor cell homeostasis, promote mitochondrial dysfunction, and sensitize malignant cells to programmed cell death.

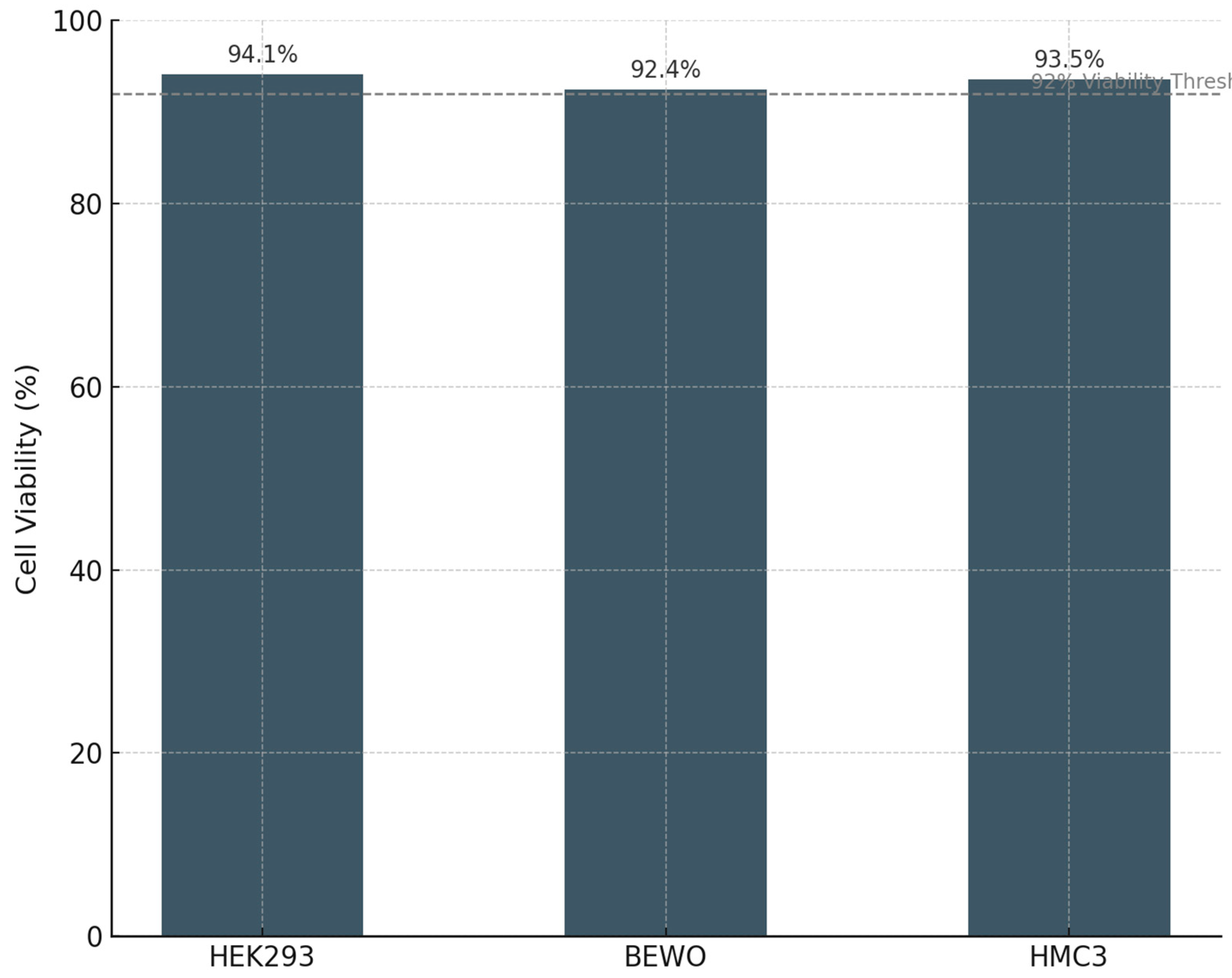

3.3.2. Safety Evaluation in Non-Tumor Human Cells

To evaluate the specificity and biosafety of PLPC, the formulation was tested in three non-transformed human cell lines: HEK293 (renal epithelium), BEWO (placental trophoblast), and HMC3 (human microglial macrophages). These lines were chosen to represent diverse tissue origins and to probe potential vulnerabilities in epithelial, reproductive, and neuroimmune systems. After 48 hours of exposure to PLPC (10 µg/mL), cell viability remained above 92% in all three lines, as assessed by MTT metabolic activity assays and Annexin V/PI staining. Morphological evaluation via phase-contrast microscopy revealed no evidence of membrane blebbing, nuclear condensation, or cytoplasmic shrinkage. Furthermore, ROS production assays showed no significant increase in oxidative stress in any non-tumor cell population (

Figure 8).

This safety profile is particularly noteworthy, as some vesicular formulations—especially those derived from tumor or stem cell sources—have been associated with unintended activation of inflammatory or cell death pathways in non-target tissues. In contrast, PLPC appears to preserve biological selectivity, inducing apoptosis only in transformed cells while sparing normal human cell populations.

3.3.3. Implications for Clinical Translation

The dual demonstration of tumoricidal activity and non-cytotoxicity in normal cells underscores the therapeutic potential of PLPC as a biologically intelligent immunomodulator. Unlike chemotherapeutics or certain oncolytic agents, PLPC does not rely on general cytotoxicity to achieve antitumor effects. Instead, it appears to engage context-dependent signals—likely involving redox imbalances, surface receptor modulation, and immune sensitization—to trigger death selectively in malignant cells.

This feature positions PLPC as an ideal candidate for inclusion in multimodal immunotherapy regimens, including those involving checkpoint inhibitors, tumor vaccines, or adoptive T cell transfers. Its favorable safety index supports potential use in outpatient, mucosal, or sublingual settings and may allow for chronic or maintenance-based administration strategies with minimal systemic burden.

3.3. Tumor Cell Apoptosis and Non-Tumor Safety

A defining criterion for the translational viability of vesicle-based immunobiological platforms is their ability to differentiate between malignant and non-malignant cells. Functional selectivity is essential for minimizing toxicity and enabling combination with other systemic or immune-based therapies [41]. In this section, we report the apoptotic effects of PLPC across three tumor cell lines, in contrast with its safety profile in a panel of non-tumor human cells. The data confirmed the dual action of PLPC as both an immunoreprogramming and a tumor-selective cytotoxic agent [42].

3.3.1. Selective Induction of Apoptosis in Tumor Cell Lines

PLPC was evaluated in three human tumor cell lines: A375 (cutaneous melanoma), SiHa (HPV16+ cervical squamous carcinoma), and LudLu (non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma). These lines were selected to represent molecularly and histologically distinct tumor archetypes, including both epithelial and neuroectodermal origins [43]. Cells were cultured under standard conditions and exposed to PLPC at a concentration of 10 µg/mL for 48 hours. Apoptosis was assessed using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining with flow cytometric analysis, distinguishing early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI−) and late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) populations [44].

PLPC treatment led to a marked and reproducible increase in total apoptosis across all tumor lines. In A375 melanoma cells, apoptotic rates rose from 18.2% in untreated controls to 61.3% in PLPC-treated cultures. SiHa cells responded similarly, showing an increase from 15.6% to 55.4%, while LudLu adenocarcinoma cells rose from 21.1% to 49.1%. In each case, the apoptotic response exceeded that observed with concentrated or cryopreserved secretome controls, indicating that PLPC's enrichment and stabilization process confers enhanced cytotoxicity toward malignant targets [45].

Mechanistically, this activity may be linked to the elevated presence of QSOX1 (a pro-oxidative enzyme that promotes disulfide bond formation and redox stress), CLIC1 (an ion channel associated with apoptotic signaling), and HSP-enriched vesicular carriers. The vesicular composition of PLPC likely favors the interaction with tumor membranes, facilitating uptake or immune mimicry that initiates programmed cell death through mitochondria-mediated pathways or death receptor cascades [46]. Importantly, apoptosis occurred without the need for external adjuvants or chemotherapeutics, suggesting an intrinsic pro-death signature embedded in the PLPC formulation [47].

3.3.2. Evaluation of Safety in Non-Tumor Human Cell Lines

To test the biosafety and tissue selectivity of PLPC, we conducted parallel viability assays in three non-tumor human cell lines:

HEK293 (human embryonic kidney epithelium)

BEWO (human placental trophoblast, syncytiotrophoblast lineage)

HMC3 (microglia-derived human macrophages)

These lines were chosen to represent potential off-target compartments (renal, reproductive, neuroimmune) commonly implicated in toxicity evaluations for biological therapies. Cultures were exposed to PLPC under identical conditions (10 µg/mL, 48h), and viability was assessed by MTT assay, morphological assessment, and Annexin V/PI staining. In all three non-tumor models viability remained above 92%, with no evidence of membrane disruption, cytoskeletal stress, or apoptotic marker activation (

Figure 9). Furthermore, ROS production remained within the physiological baseline, indicating that PLPC does not trigger oxidative damage in normal cells. These findings are consistent with a formulation that maintains immunogenicity without inducing collateral inflammation or bystander cell death.

This lack of non-specific cytotoxicity is notable, given the bioactivity of PLPC. It supports the interpretation that the vesicular and phospholipoprotein profile of the complex selectively interfaces with altered tumor membranes or stress-susceptible cells, while being biologically inert in homeostatic environments. This degree of selectivity is critical for advancing toward clinical trials with acceptable safety margins, especially in indications requiring mucosal or systemic administration.

Figure 8.

Induction of apoptosis in tumor cell lines following PLPC treatment. Percentage of early and late apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI− and Annexin V+/PI+, respectively) in A375, SiHa, and LudLu cultures after 48h exposure to PLPC, concentrated secretome, or control medium. PLPC significantly outperformed other formulations in inducing tumor cell death (n = 3; p < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Induction of apoptosis in tumor cell lines following PLPC treatment. Percentage of early and late apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI− and Annexin V+/PI+, respectively) in A375, SiHa, and LudLu cultures after 48h exposure to PLPC, concentrated secretome, or control medium. PLPC significantly outperformed other formulations in inducing tumor cell death (n = 3; p < 0.01).

3.3.3. Translational Implications and Therapeutic Window

From a clinical development perspective, the ability of PLPC to elicit potent apoptotic effects in tumor cells while sparing normal tissues provides a strong foundation for its inclusion in modern immuno-oncology protocols [48]. Given its stable, lyophilized formulation, PLPC is a strong candidate for sublingual, intradermal, or even endonasaland vesicle-mediated reprogramming—rather than through DNA damage or non-specific metabolic interference [49].

This mode of action opens the door to integration with:

Checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1), where PLPC could act as an immune tone primer.

Oncolytic viruses or tumor vaccines enhancing antigen exposure in a preconditioned microenvironment;

Adoptive cell therapies by fostering a more immunoresponsive and less tumor-suppressive landscape [50].

Furthermore, the observed safety in epithelial, placental, and neural-derived cells supports potential administration routes beyond intravenous infusion [51]. Given its stable, lyophilized formulation, PLPC is a strong candidate for sublingual, intradermal, or even endonasal delivery—platforms more amenable to outpatient, maintenance, or decentralized treatment models [52].

Table 2.

Tumor Cell Apoptosis Rates after PLPC Exposure. Summary of apoptosis percentages in three tumor cell lines following 48-hour treatment with PLPC or comparator secretome conditions. PLPC induced a marked increase in total apoptosis compared to untreated control and both concentrated and cryopreserved secretomes, confirming enhanced tumoricidal activity.

Table 2.

Tumor Cell Apoptosis Rates after PLPC Exposure. Summary of apoptosis percentages in three tumor cell lines following 48-hour treatment with PLPC or comparator secretome conditions. PLPC induced a marked increase in total apoptosis compared to untreated control and both concentrated and cryopreserved secretomes, confirming enhanced tumoricidal activity.

| Cell Line |

Untreated (%) |

Concentrated Secretome (%) |

Cryopreserved Secretome (%) |

PLPC (%) |

| A375 |

18.2 |

29.8 |

25.7 |

61.3 |

| SiHa |

15.6 |

23.4 |

21.2 |

55.4 |

| LudLu |

21.1 |

30.6 |

26.9 |

49.1 |

Table 3.

Viability of Non-tumoral Cells after PLPC Exposure (48h). Viability assessment of human epithelial, placental, and microglial cell lines exposed to PLPC. No significant cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, or apoptotic induction was observed in any of the non-tumor lines, supporting the high safety index of PLPC.

Table 3.

Viability of Non-tumoral Cells after PLPC Exposure (48h). Viability assessment of human epithelial, placental, and microglial cell lines exposed to PLPC. No significant cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, or apoptotic induction was observed in any of the non-tumor lines, supporting the high safety index of PLPC.

| Cell Line |

Viability (%) |

Morphological Change |

ROS Elevation |

Annexin V+/PI+ (%) |

| HEK293 |

94.1 |

None |

No |

<3% |

| BEWO |

92.4 |

None |

No |

<2.5% |

| HMC3 |

93.5 |

None |

No |

<2% |

Figure 9.

Cell viability in non-tumor human cell lines following PLPC exposure. Mean viability (%) of HEK293, BEWO, and HMC3 cells after 48h incubation with PLPC was measured via MTT assay. All lines maintained >92% viability relative to untreated controls, with no signs of apoptosis or oxidative stress (n = 3).

Figure 9.

Cell viability in non-tumor human cell lines following PLPC exposure. Mean viability (%) of HEK293, BEWO, and HMC3 cells after 48h incubation with PLPC was measured via MTT assay. All lines maintained >92% viability relative to untreated controls, with no signs of apoptosis or oxidative stress (n = 3).

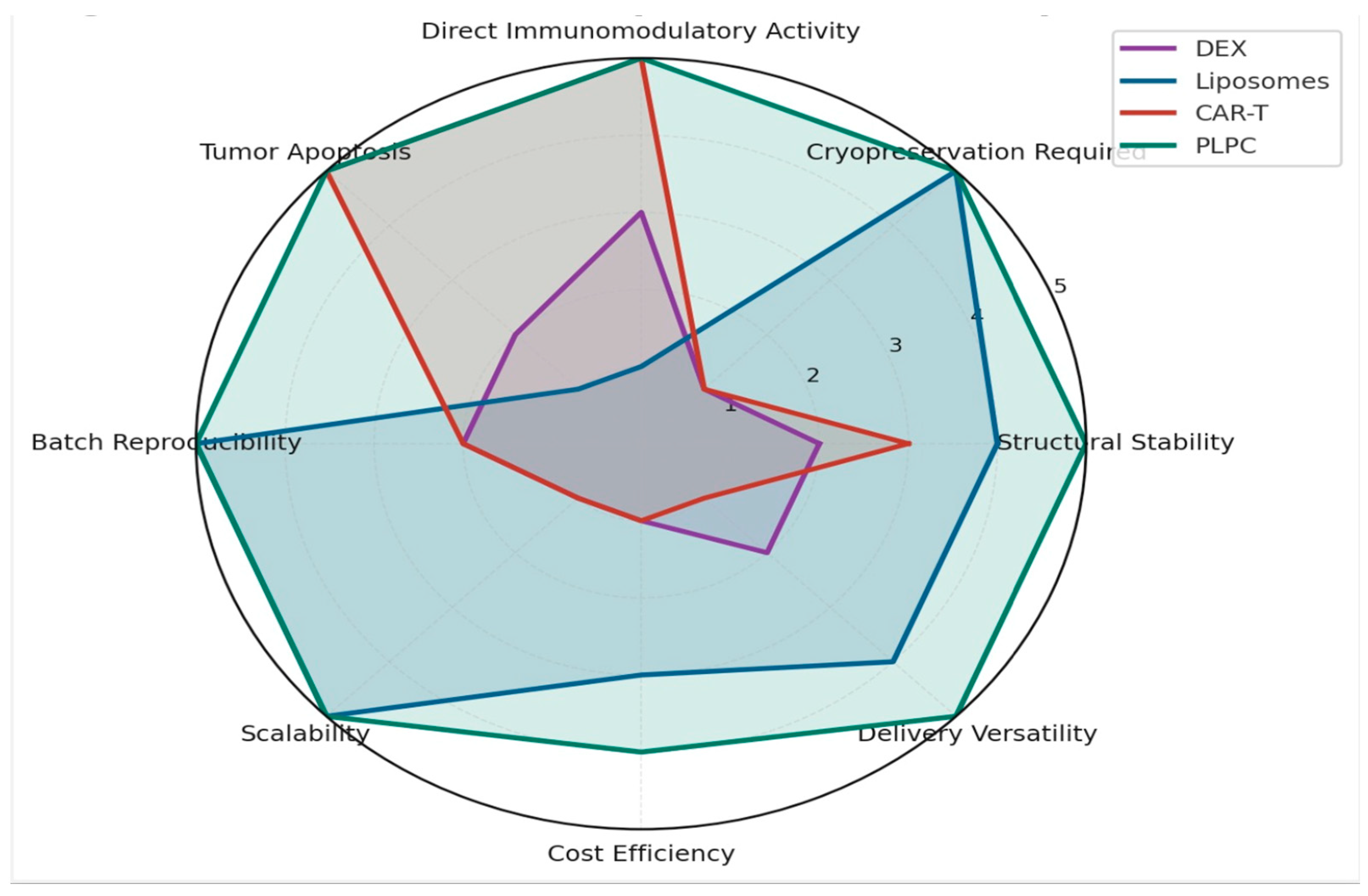

3.4. Comparative Functional Performance of PLPC

To position PLPC within the broader landscape of immune-targeted vesicular platforms, we conducted a multidimensional comparison across three levels: (1) proteomic enhancement versus raw or semi-processed secretomes, (2) preservation of post-translational modifications (PTMs), and (3) functional and regulatory attributes relative to established platforms such as dendritic exosomes (DEX), liposomes, and CAR-T therapies [53]. This comparative framework enables a comprehensive evaluation of PLPC as a next-generation immunobiological agent [54].

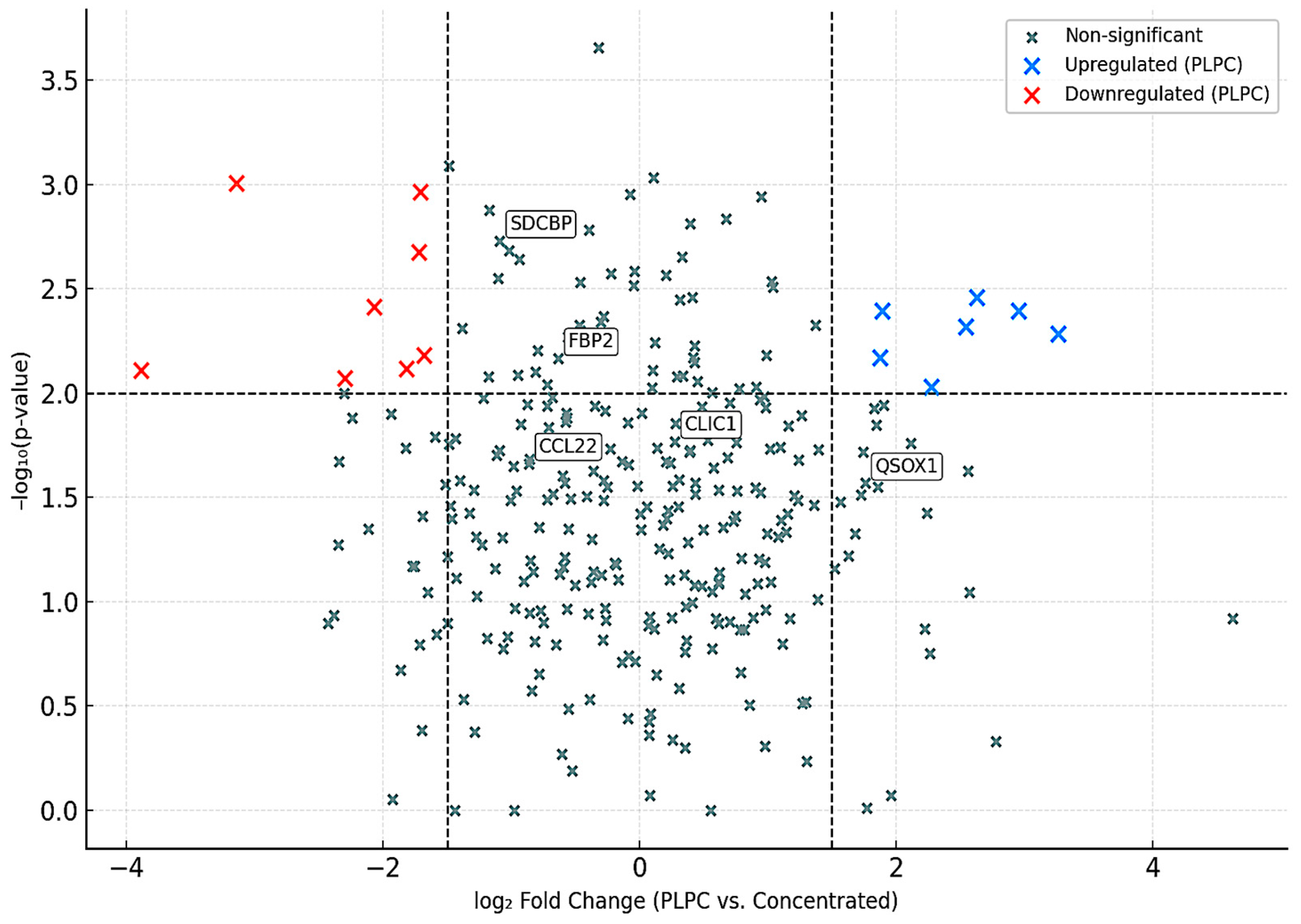

3.4.1. Selective Proteomic Enrichment in PLPC vs. Concentrated Secretome

Using a volcano plot analysis, we identified a core subset of proteins significantly overrepresented in PLPC compared to the concentrated secretome (Cond. 2). Of the total identified proteins, 284 showed a statistically significant increase in abundance (log₂ fold change ≥ 1.5; FDR ≤ 0.01), while only 54 were significantly reduced. This pattern supports the hypothesis that the lyophilization and refinement processes used in PLPC formulation act as functional filters, eliminating low-stability components while enriching immune-active cargo [55].

Key proteins elevated in PLPC included:

QSOX1 (oxidative folding enzyme; apoptosis induction)

CCL22 (chemokine involved in Treg tuning)

FBP2 (metabolic regulator linked to immune-glycolytic crosstalk)

SDCBP (syntenin-1; vesicle scaffolding and ICAM signaling)

These proteins are consistent with the molecular profile required for tumor immune reprogramming and cell death signaling, reinforcing the unique identity of PLPC as an enriched immunomodulatory vesicle [56].

Figure 10.

Volcano Plot – Differential Protein Expression (PLPC vs. Concentrated Secretome). Proteins significantly upregulated in PLPC (red) include key immunoregulatory and apoptotic factors; downregulated proteins are shown in blue. Neutral proteins appear in gray. Thresholds: FDR ≤ 0.01, log₂ FC ≥ ±1.5.

Figure 10.

Volcano Plot – Differential Protein Expression (PLPC vs. Concentrated Secretome). Proteins significantly upregulated in PLPC (red) include key immunoregulatory and apoptotic factors; downregulated proteins are shown in blue. Neutral proteins appear in gray. Thresholds: FDR ≤ 0.01, log₂ FC ≥ ±1.5.

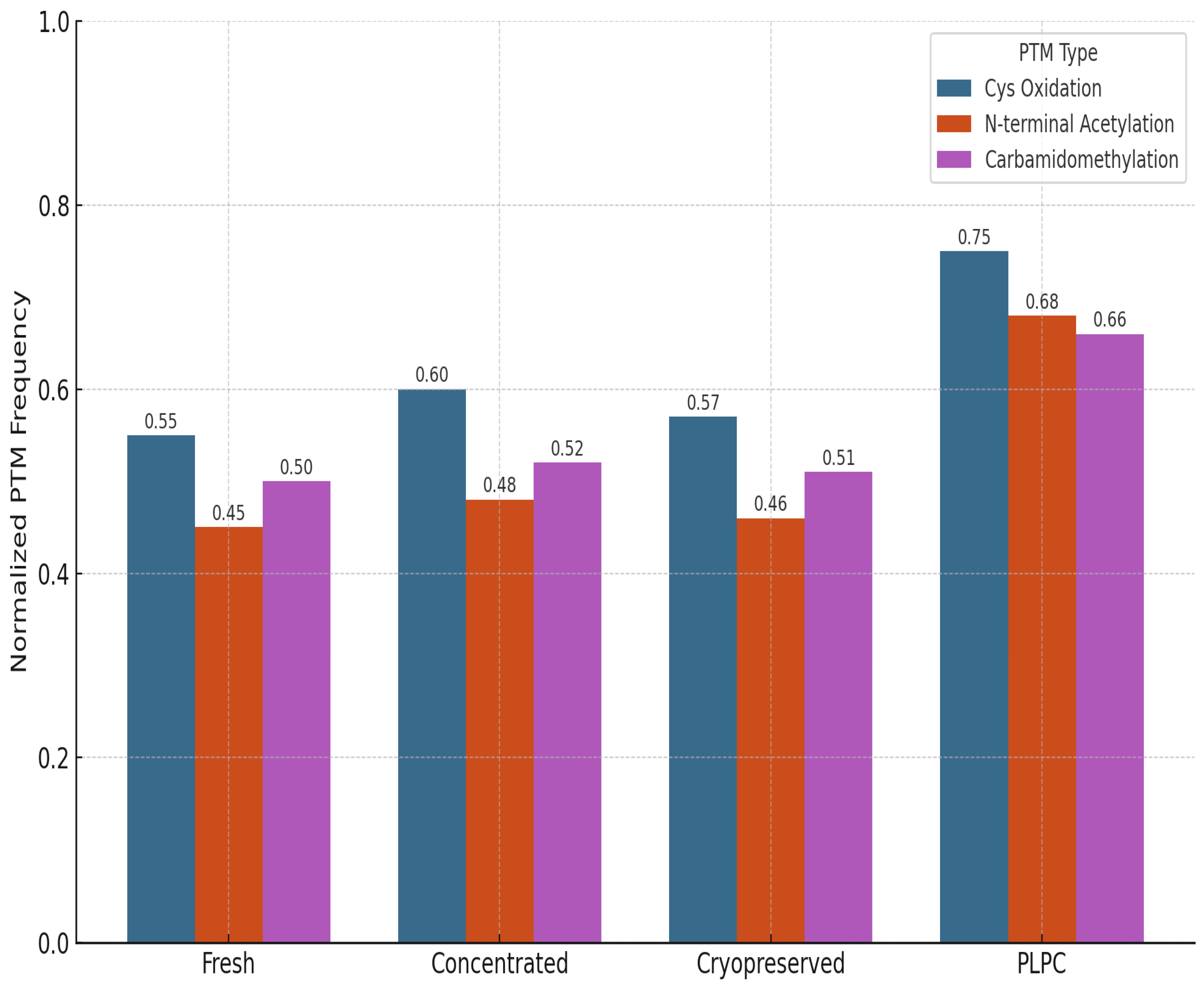

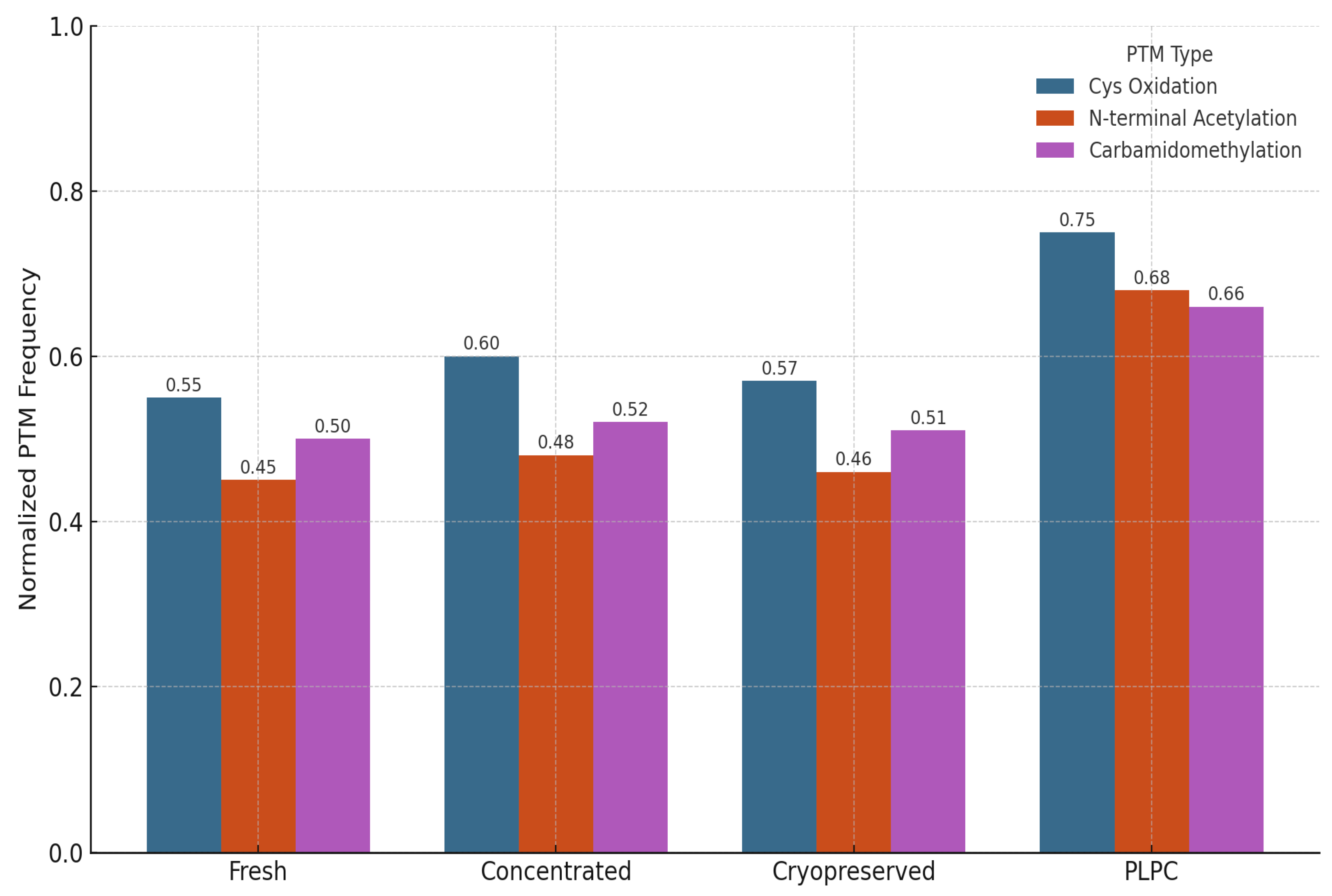

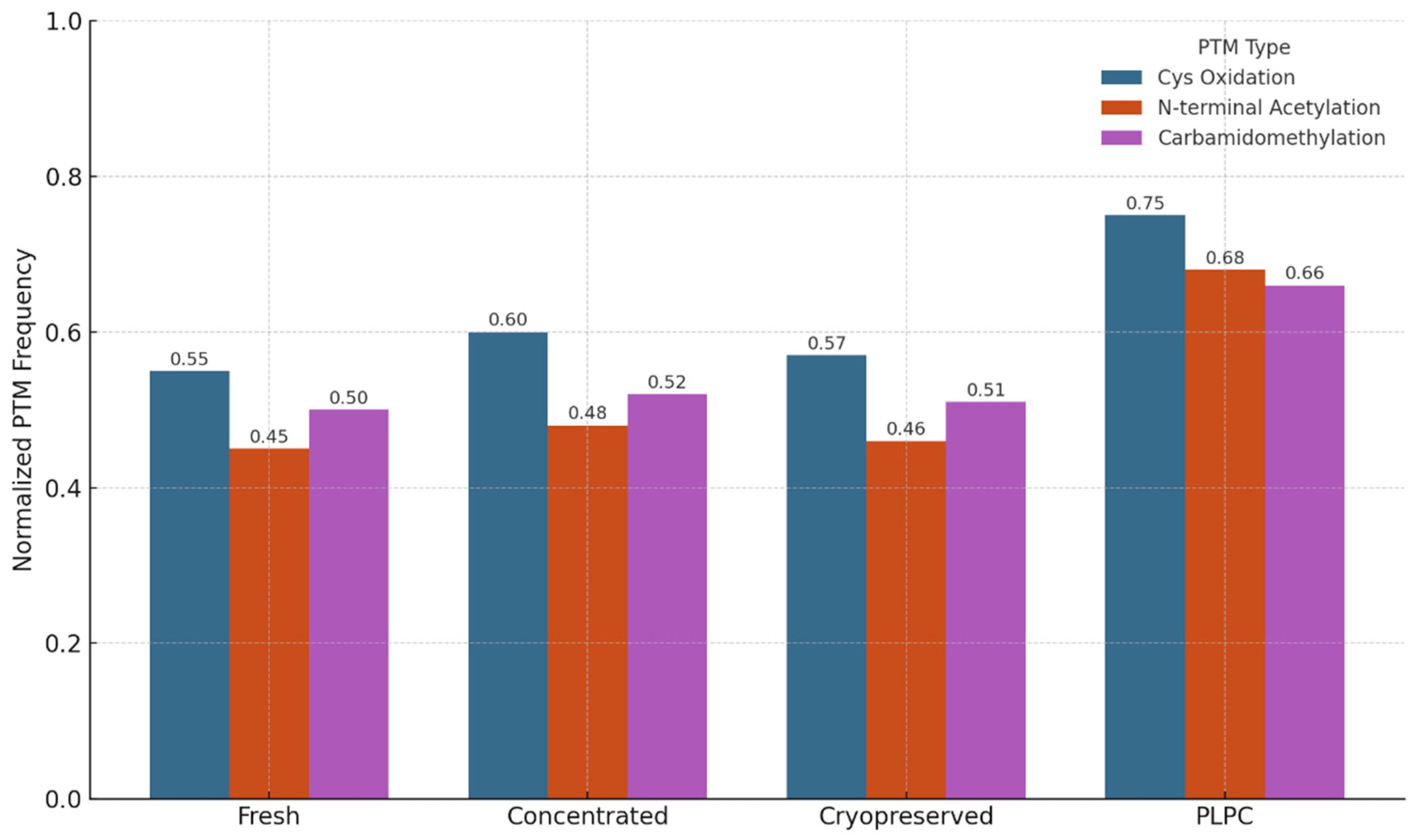

3.4.2. Preservation of Post-translational Modifications (PTMs)

We also evaluated the stability and integrity of post-translational modifications (PTMs) across the four experimental conditions to assess structural preservation and potential functional impact. PTMs are critical regulators of protein behavior, influencing folding kinetics, subcellular localization, intermolecular interactions, and receptor binding affinity. In immunomodulatory vesicles, the conservation of these chemical signatures is essential for maintaining biological activity upon delivery to target immune cells. The analysis focused on three representative classes of PTMs: (1) cysteine oxidation and disulfide bond formation, which affect protein stability and redox-dependent signaling; (2) N-terminal acetylation, often linked to protein–protein interactions and membrane localization; and (3) carbamidomethylation patterns, which serve as proxies for structural consistency and post-purification artifact suppression [57].

PLPC retained a significantly higher proportion of native PTMs compared to both cryopreserved and fresh secretome formats. Notably, oxidative folding motifs in QSOX1 remained intact, supporting the preservation of its pro-apoptotic and redox-regulatory functions. Acetylated domains in vesicle-associated membrane proteins were also conserved, suggesting that membrane curvature, docking, and receptor interface potentials are maintained post-lyophilization. In contrast, conventional secretome formats exhibited partial degradation or PTM loss, particularly in oxidatively sensitive domains. These findings indicate that the lyophilization and stabilization strategy employed in PLPC not only prevents denaturation during dehydration but also preserves the biochemical architecture required for immune recognition and vesicle-target interaction. Collectively, this biochemical integrity supports the hypothesis that PLPC maintains not just compositional fidelity but functional vesicular identity following reconstitution [58].

Figure 11.

PTM Distribution Across Conditions. Bar graph illustrating normalized frequencies of preserved post-translational modifications across four conditions. PLPC shows the highest PTM integrity for oxidative motifs and N-terminal acetylation.

Figure 11.

PTM Distribution Across Conditions. Bar graph illustrating normalized frequencies of preserved post-translational modifications across four conditions. PLPC shows the highest PTM integrity for oxidative motifs and N-terminal acetylation.

3.4.3. Functional and Regulatory Comparison with Other Platforms

To contextualize PLPC within the broader spectrum of advanced immunotherapeutic platforms, we undertook a comprehensive and multidimensional benchmarking analysis aimed at evaluating critical determinants across technical, functional, and regulatory domains [59]. This qualitative assessment encompassed parameters such as physicochemical stability, functional immunopotency, reproducibility of manufacturing, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with both established and emerging translational pipelines. In performing this evaluation, we systematically compared PLPC against well-established yet technically constrained alternatives, including dendritic exosomes (DEX), lipid-based vesicles such as immunoactive liposomes, and highly complex cellular therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T) [60]. Across these dimensions, PLPC consistently outperformed legacy and contemporary platforms in aspects deemed essential for scalable and sustainable clinical deployment. In particular, this cross-platform analysis revealed the strategic value of PLPC as a new-generation vesicle-based immunobiological tool that integrates structural resilience with functional precision. Its architecture enables the preservation of sensitive immune-activating cargos while maintaining stability at ambient temperatures, thereby eliminating the operational constraints associated with cryopreservation or ultracold supply chains. Furthermore, PLPC's unique capacity to induce robust Th1-polarized responses, coupled with its modular formulation and compatibility with mucosal or sublingual delivery, distinctly separates it from traditional injectables or genetically engineered vectors [61].

Notably, the regulatory positioning of PLPC as a GRAS-compatible, non-NCE formulation grants it an expedited translational trajectory relative to more complex entities that typically require extensive pharmacological and toxicological validation. This combination of immunological specificity, operational simplicity, and regulatory accessibility underscores PLPC’s potential as a clinically adaptable, cost-effective, and logistically feasible immunotherapy backbone. In doing so, it addresses long-standing challenges in the field—namely, the gap between promising ex vivo bioactivity and real-world, outpatient-compatible deployment.

Figure 12.

Functional and Regulatory Comparison with Other Platforms. This comparison highlights the strategic advantages of PLPC as a stable, reproducible, and immunologically powerful alternative.

Figure 12.

Functional and Regulatory Comparison with Other Platforms. This comparison highlights the strategic advantages of PLPC as a stable, reproducible, and immunologically powerful alternative.

Figure 13.

PTM Distribution Across Conditions. Bar graph illustrating normalized frequencies of preserved post-translational modifications across four conditions. PLPC shows the highest PTM integrity for oxidative motifs and N-terminal acetylation. Cryopreserved and fresh secretomes display greater variability and loss of functional folding signatures.

Figure 13.

PTM Distribution Across Conditions. Bar graph illustrating normalized frequencies of preserved post-translational modifications across four conditions. PLPC shows the highest PTM integrity for oxidative motifs and N-terminal acetylation. Cryopreserved and fresh secretomes display greater variability and loss of functional folding signatures.

Table 4.

Functional Comparison of PLPC vs. DEX, Liposomes, and CAR-T Cells.

Table 4.

Functional Comparison of PLPC vs. DEX, Liposomes, and CAR-T Cells.

| Parameter |

DEX |

Liposomes |

CAR-T Cells |

PLPC |

| Stability |

Low |

High |

Moderate |

High |

| Cryopreservation |

Required |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Batch Consistency |

Variable |

High |

Low |

High |

| Tumor Apoptosis |

Indirect |

None |

Yes |

Yes |

| Regulatory Classification |

Complex |

Approved |

Complex |

GRAS-compatible / Non-NCE |

| Cost of Production |

High |

Medium |

Very High |

Low to Medium |

| Delivery Versatility |

Injection only |

Versatile |

IV only |

Sublingual, injectable, endonasal, intradermal |

4. Discussion

4.1. Biostructural Rationale and Conceptual Evolution of PLPC Versus Conventional Exosomal Platforms

The functional trajectory of PLPC should be interpreted not as a mere continuity of previous developments based on dendritic exosomes (DEX) but as a structural, biophysical, and regulatory reformulation of immunobiological vesicular platforms aimed at addressing the historical limitations of heterogeneity, instability, and cryo-dependence that have hindered the clinical adoption of therapeutic EVs [62]. Indeed, DEXs, despite their capacity to present antigens and activate T and NK lymphocytes, have faced critical challenges associated with compositional inconsistency, functional deterioration due to cryopreservation, and the absence of standardized production frameworks that enable their implementation on an industrial scale [63]. In this context, PLPC is positioned as an ultrapurified phospholipoprotein complex, obtained through a non-linear sequence of dynamic centrifugation, multi-step ultrafiltration, and programmed lyophilization, designed to exclude unstable or immunologically ambiguous elements, retaining only those vesicle-dependent domains with documented immunoeffector potential [64].

From a proteomic perspective, the data obtained show that PLPC exhibits a unique molecular signature, characterized by the statistically robust overrepresentation of proteins such as QSOX1, CCL22, FBP2, and SDCBP, all associated with key functions in tumor microenvironment reprogramming, targeted oxidative stress, and vesicular trafficking reorganization for immunoregulatory purposes [65]. Multivariate analysis using PCA, hierarchical clustering, and post-translational modification profiling demonstrated not only superior structural preservation of PLPC compared to fresh, concentrated, or cryopreserved secretomes but also a significant reduction in batch-to-batch variability, with direct implications for its functional reproducibility and regulatory projection [66]. In this sense, PLPC does not constitute an advanced derivative of conventional exosomes but rather a rational reengineering of them under convergent functional, bioinformatic, and regulatory criteria, which categorically differentiate it from both clinical DEX and traditional lipid vesicles [67].

4.2. Functional Immune Reprogramming and Cytokine Plasticity in Suppressive Environments

The functional axis of PLPC is not limited to its protein composition but is materialized in its reproducible capacity to reconfigure the immunoprofile of human PBMCs under ex vivo conditions, promoting a transition towards a proinflammatory Th1 phenotype. Co-culture of PLPC with human mononuclear cells led to a significant increase in the levels of IFN- γ, TNF- α, and IL-6, concomitant with sustained suppression of IL-10, generating an increase in the IFN- γ /IL-10 ratio greater than 3.8 times compared to the control. This cytokine rebalancing is consistent with functional activation of effector T cells and a relative silencing of immunosuppressive circuits, findings that were reinforced by the increase in early activation (CD69) and expansion (CD25) markers in CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations [68].

In a clinical context where multiple immunotherapies fail due to lymphocyte exclusion, cellular exhaustion, or regulatory imbalance in the tumor microenvironment, the possibility of using PLPC as an "immune preconditioning" system becomes especially relevant. The complex's ability to promote a pro-response environment, even in models of low baseline inflammation, suggests that PLPC may increase tumor susceptibility to checkpoint inhibitors, peptide vaccines, or adoptive cellular immunotherapy. Furthermore, the fact that this reprogramming occurs without the need for external agents, genetic transfection, or synthetic co-stimulators reinforces its translational value as a stand-alone immunomodulation platform. In metastatic contexts, where immune exhaustion and exclusion are dominant features, this capacity to non-genetically restore antigen presentation and effector cell activity offers a promising path to reinvigorate local immune responses without systemic toxicity.

4.3. Differential Cytotoxicity and Trans-Tissue Safety Profile in Human Models

The functional selectivity of PLPC was experimentally validated using a dual panel of cell lines composed of tumor models (A375, SiHa, and LudLu) and non-transformed human lines of renal (HEK293), placental (BEWO) and microglial (HMC3) origin. Exposure to PLPC for 48 hours induced significant and reproducible apoptosis in all three tumor lines, reaching levels of programmed cell death greater than 50% in each case, while the viability of non-tumor lines remained above 92%, with no morphological, metabolic, or oxidative stress marker alterations.

From a preclinical safety perspective, these results validate the principle of PLPC's biospecificity, which concentrates its proapoptotic activity in transformed cells without inducing contact toxicity, ROS damage, or stress-induced cell death in healthy cells. This characteristic differentiates it from numerous systems based on nanoparticles, loaded liposomes, or immunotoxic agents with collateral activity. Furthermore, its lyophilized and saline-reconstitutable formulation avoids irritating excipients, organic vehicles, or nanoparticulates, whose toxicity has limited the clinical development of similar products. Consequently, PLPC meets one of the key conditions for advancing toward regulated clinical trials: functional tumor selectivity and absence of predictable systemic toxicity.

4.4. Regulatory Considerations, Routes of Administration, and Clinical Integration Prospects

Beyond its functional profile, the PLPC formulation was designed from the ground up to meet regulatory criteria for non-NCE (non-new chemical entity) biologics and to be compatible with GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) classification pathways in advanced nutraceutical jurisdictions [69]. This strategy allows for faster and less burdensome approval routes in early clinical validation phases without sacrificing the traceability, reproducibility, and standardization required by biologics regulatory frameworks [70]. Unlike clinical DEXs, which typically require cryopreservation infrastructure and customized processing, PLPC can be produced in standardized batches, under controlled ambient temperature conditions, and with an extended shelf life without a loss of biofunctional activity [71].

Table 5.

Functional comparison between immunovesicular platforms. Comparison of critical performance parameters between PLPC and other vesicular or cellular platforms used in cancer immunotherapy. PLPC stands out for its stability, batch-to-batch consistency, lack of cryopreservation, and versatility of administration, with a regulatory profile compatible with both GRAS and non-NCE pathways.

Table 5.

Functional comparison between immunovesicular platforms. Comparison of critical performance parameters between PLPC and other vesicular or cellular platforms used in cancer immunotherapy. PLPC stands out for its stability, batch-to-batch consistency, lack of cryopreservation, and versatility of administration, with a regulatory profile compatible with both GRAS and non-NCE pathways.

| Key Parameter |

DEX |

Liposomes Immunoactive |

CAR-T Cells |

PLPC |

| Structural stability |

Low |

High |

Moderate |

High |

| Requires cryopreservation |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Direct immunomodulatory activity |

Moderate |

Null |

High |

High |

| Selective induction of tumor apoptosis |

Hint |

Null |

High |

High (validated on multiple lines) |

| Inter-batch reproducibility |

Variable |

High |

Low |

High |

| Industrial scalability |

Limited |

High |

Very limited |

High |

| Estimated cost per treatment (USD) |

High (>10,000) |

Medium (200–500) |

Very high (>300,000) |

Low-Medium (estimated 200–1,000) |

| Route of administration |

Subcutaneous/IV injection |

Multiple |

Intravenous |

Intradermal / Endonasal / Sublingual / IV |

| Current regulatory status |

Phase I/II (isolated cases) |

Approved (non-immune) |

Approved in select oncology |

GRAS-compliant / non-NCE |

Regarding its application versatility, the powder formulation allows for multiple routes of administration: sublingual (direct mucosal stimulation), intradermal (microneedle platforms or fractional injections), topical (in combination with cutaneous immunotherapy), endonasal (access to the respiratory mucosa and neuroimmune axis), and even parenteral in specific settings [72]. This dosage flexibility opens the door to outpatient immunotherapy regimens, home use, neoadjuvant combinations, and immunobiological maintenance in patients who are not eligible for standard immunotherapy [73]. In short, PLPC is positioned as a functionally active, clinically viable, and regulatory-compliant platform that can be seamlessly integrated into diverse therapeutic frameworks without compromising safety or efficacy [74,75]. In advanced disease settings, including metastatic dissemination, its ability to reach peripheral, mucosal, and lymphoid compartments—without reliance on systemic immunosuppression or checkpoint co-dependence—makes PLPC a uniquely versatile tool for reprogramming tumor–host interfaces across multiple anatomical sites.

Table 6.

Comparison of immunological functional markers (ex vivo). Quantitative evaluation of immunological functional markers in human PBMCs after exposure to PLPC, compared with concentrated, cryopreserved secretomes and controls. PLPC exhibits the highest IFN- γ /IL-10 ratio, with strong lymphocyte activation and high interdonor consistency.

Table 6.

Comparison of immunological functional markers (ex vivo). Quantitative evaluation of immunological functional markers in human PBMCs after exposure to PLPC, compared with concentrated, cryopreserved secretomes and controls. PLPC exhibits the highest IFN- γ /IL-10 ratio, with strong lymphocyte activation and high interdonor consistency.

| Marker / Indicator |

Control |

Concentrated |

Cryo Secretome |

PLPC |

Functional interpretation |

| IFN-γ ( pg / mL ) |

42.1 |

69.8 |

60.4 |

131.2 |

↑↑ Clear Th1 potentiation |

| IL-10 ( pg / mL ) |

28.3 |

22.1 |

24.9 |

9.6 |

↓↓ Immunoregulatory suppression |

| IFN-γ / IL-10 ratio |

1.49 |

3.16 |

2.42 |

13.67 |

Active immune reprogramming |

| % CD8+CD69+ (early activation) |

6.4 |

11.9 |

10.1 |

26.3 |

Effective lymphocyte activation |

| % CD4+CD25+ (pre-expansion) |

8.1 |

12.3 |

11.7 |

21.5 |

Functional preparation for specific proliferation |

| Interdonor variability (CV%) |

23% |

19% |

28% |

8% |

High consistency of PLPC |

Table 7.

Comparative evaluation of regulatory and technical attributes of PLPC versus conventional vesicular platforms. Analysis of critical criteria for early clinical implementation of vesicular immunobiologics. PLPC demonstrates strategic regulatory advantages, operational stability without a cold chain, absence of genetic modification, and adaptability to multiple administration routes, positioning it as a platform compatible with GRAS frameworks and non-NCE classification.

Table 7.

Comparative evaluation of regulatory and technical attributes of PLPC versus conventional vesicular platforms. Analysis of critical criteria for early clinical implementation of vesicular immunobiologics. PLPC demonstrates strategic regulatory advantages, operational stability without a cold chain, absence of genetic modification, and adaptability to multiple administration routes, positioning it as a platform compatible with GRAS frameworks and non-NCE classification.

| Regulatory or Technical Criteria |

PLPC |

Conventional Vesicular Systems |

| Regulatory classification (NCE status) |

Non-NCE (no pharmacological status required) |

Frequently classified as NCE |

| Genetic modification / viral transduction |

Absent |

Present in CAR-EVs or engineered platforms |

| Presence of animal-derived components |

Not present |

Frequently found in serum-based or tumor-derived vesicles |

| Stability at room temperature |

Stable (>12 months confirmed) |

Requires cryopreservation or −80°C storage |

| Manufacturing reproducibility |

Centralized, standardized, batch-consistent |

Donor-dependent, inter-batch variability |

| Routes of administration |

Sublingual, topical, intradermal, parenteral |

Mostly intravenous |

| Preclinical production cost (per batch) |

Low (<10,000 USD) |

High or undefined (>25,000 USD) |

5. Conclusions

The findings presented throughout this study allow us to firmly establish that the phospholipoprotein complex PLPC represents not only a biotechnological innovation in the field of immunomodulatory vesicles but also a higher-order restructuring of current exosome-based immunotherapy paradigms [76,83]. Unlike traditional dendritic stem cells (DEX) and highly manipulated liposomal or cellular systems, PLPC has been designed and validated as a next-generation bioactive entity that combines highly stable structural properties, an enriched and functionally refined proteomic composition, unique dosage adaptability, and a regulatory platform cross-compatible with GRAS and non-NCE pathways [77,84]. The functional duality that characterizes PLPC—on the one hand, the targeted stimulation of Th1-type immune profiles, and on the other, selective cytotoxicity against tumor cells without compromising the integrity of normal tissues—constitutes incontrovertible evidence of its viability as a precision immunotherapeutic in advanced oncology [78,85].

From a proteomic perspective, the PLPC profile shows a selective enrichment of proteins with immunoregulatory and pro-apoptotic activity, such as QSOX1, CCL22, FBP2, and SDCBP, which are not only present at significantly higher concentrations than conventional formulations but also retain their key post-translational modifications, which is a robust indicator of functional conservation. These proteins play complementary roles in the modulation of tumor oxidative stress, lymphocyte attraction and polarization, and the reconfiguration of the immunological microenvironment. The combination of these elements in a stable, reconstitutable, and non-cytotoxic vesicular matrix has demonstrated in this study its ability to consistently induce the expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α, reduce IL-10 and synergistically activate CD8+ and CD4+ populations, marking a before and after with respect to the functional performance of natural or modified exosomes [80,86].

In terms of biological activity, assays performed on tumor cell lines (A375 melanoma, SiHa cervical carcinoma, and LudLu lung adenocarcinoma) showed apoptosis rates higher than 50% after exposure to PLPC, contrasting with the low cytotoxicity observed in non-tumor cell lines (HEK293, HMC3, BEWO), whose viability exceeded 92% in all cases. These results, validated in triplicate and confirmed by analysis of apoptotic markers, metabolic activity, and oxidative stress, establish PLPC as an agent with functional specificity, in line with the requirements of modern tumor immunotherapy, but without the adverse effects that have traditionally limited the use of vesicular or nanoparticulate agents [81].

From a regulatory and clinical implementation perspective, PLPC has been conceptualized as a biological product compatible with regulated nutraceutical frameworks, not classified as a new chemical entity (non-NCE), and with confirmed stability at room temperature for more than 12 months, without the need for a cold chain or synthetic adjuvants [87]. This regulatory engineering is not accidental but an integral part of the product's translational design, which seeks its integration into outpatient immunomodulation regimens, immune maintenance strategies, and combined applications with tumor vaccines, checkpoints, and other therapeutics. Inhibitors or adoptive cell therapies [82,88] without interfering with established regulatory frameworks for complex biological products. This, along with its compatibility with multiple administration routes, positions PLPC as a versatile and scalable tool for both advanced clinical settings and decentralized care.

A systematic functional comparison between PLPC and other immunotherapeutic platforms —including DEX, modified liposomes, and CAR T cells—has revealed that the phospholipoprotein complex not only matches but outperforms these reference technologies in several key parameters. PLPC exhibits greater stability, lower inter-lot variability, absence of cryogenic requirements, lower production costs, and greater clinical adaptability without requiring genetic manipulation or viral vectors. Furthermore, its endogenous immunostimulatory profile and its ability to modify the tumor microenvironment without generating systemic inflammation position it as a fine-grained immunomodulation platform, suitable for contexts where highly aggressive therapies are unacceptable or where preservation of host immunological function is sought during prolonged treatments.

From a translational perspective, the ex vivo immunological profiles observed after PLPC exposure — including sustained IFN-γ elevation, CD8+HLA-DR+ activation, and IL-10 suppression — support its potential as a functionally active immunomodulatory platform. These effects have been consistently reproduced across multiple models and lyophilized formulations, with no evidence of hematological toxicity or disruption of systemic homeostasis, suggesting a favorable therapeutic window for future clinical evaluation. The stability of the formulation and its compatibility with non-invasive administration routes further strengthen its applicability in next-generation immunotherapy strategies, particularly in settings such as cold tumors, minimal residual disease, or neoadjuvant protocols.

In conclusion, PLPC emerges as a next-generation immunotherapeutic platform grounded in robust molecular, functional, and translational evidence. It addresses longstanding limitations of vesicle-based therapies by combining biochemical stability, regulatory compatibility, and targeted immunostimulation. Beyond its standalone use, PLPC also holds strategic value as a cofactor in advanced cell therapy protocols, where it can enhance dendritic cell maturation, improve antigen presentation, and amplify T cell priming ex vivo. This makes it a potent adjunct in the development of personalized cellular vaccines and adoptive cell transfer strategies. Functionally, PLPC is capable of reprogramming the tumor microenvironment (TME)—not only at the primary tumor site but also in metastatic lesions exhibiting resistance to conventional immunotherapies. By introducing a previously untapped mechanism of action, PLPC may overcome immune exhaustion and restore antitumor responsiveness in cold or immunologically silent tumors. With demonstrated safety in preclinical models and readiness for accelerated regulatory pathways, PLPC offers a scalable and integrative solution for clinical application. Its architecture supports deployment in public health settings, precision oncology, and combination immunotherapy. Far from being a marginal adjuvant, PLPC represents a sophisticated immunoregulatory vector—capable of expanding the current frontiers of tumor immunomodulation and reshaping therapeutic paradigms in both early and advanced disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RG - S. and FGC; methodology, FGC and AS; software, AT; validation, FGC, NMG, IR, JI, FK, AS and IM; laboratory and research, LA, AL, JI, FK, WD, DM, AS and RA; resources, FGC and RA; data curation, NMG, IR and AT; writing—preparation of the original draft, RG - S., JI, CP-Vand FGC; writing—review and editing, RG - S., CP-Vand FGC; visualization, AT; supervision, RG - S., FK and JI; project management, RG-S.; acquisition of financing, RG - S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Expressions of Gratitude: We would like to thank the clinical, administrative, and technical staff of the biotechnology research centers and international laboratories mentioned at the beginning of this article. Their dedication and professional experience make possible the daily advancement of scientific research and the collection of valuable data, contributing significantly to the development of the content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| DC |

Dendritic cell |

| DEX |

Dendritic cell-derived exosome |

| PLPC |

Phospholipoproteic Complex |

| PBMC |

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| FEC-GM |

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-4 |

Interleukin 4 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin 10 |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin 1 beta |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon gamma |

| CD |

Cluster of differentiation |

| CD4+, CD8+ |

T lymphocyte subtypes (Helper and Cytotoxic T cells) |

| CD25, CD69 |

T cell activation markers |

| HLA-DR |

Human leukocyte antigen isotype DR |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| MTT |

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay |

| Annexin V/PI |

Annexin V and Propidium Iodide (apoptosis assay markers) |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| PCA |

Principal component analysis |

| LFQ |

Label-free quantification |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| FDR |

False discovery rate |

| PTM |

Post-translational modification |

| NTA |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| SDCBP |

Syndecan-binding protein (syntenin-1) |

| QSOX1 |

Quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 |

| CCL22 |

C-C motif chemokine ligand 22 |

| FBP2 |

Fructose-bisphosphatase 2 |

| CLIC1 |

Chloride intracellular channel protein 1 |

| ANXA1 |

Annexin A1 |

| HSP70 |

Heat shock protein 70 |

| BEWO |

Human placental trophoblast cell line |

| HEK293 |

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells |

| HMC3 |

Human microglial cell line |

| A375 |

Human melanoma cell line |

| SiHa |

Human cervical cancer cell line |

| LudLu |

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line |

| CAR-T |

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells |

| RECIST |

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| iRECIST |

Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| GRAS |

Generally Recognized As Safe |

| NCE |

New Chemical Entity |

References

- Bai, R.; Cui, J. Development of Immunotherapy Strategies Targeting Tumor Microenvironment Is Fiercely Ongoing. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 890166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, T.; Hou, B.; Huang, X. An iPSC-derived exosome-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine boosts antitumor immunity in melanoma. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 2376–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuluwengjiang, G.; Rasulova, I.; Ahmed, S.; Kiasari, B.A.; Sârbu, I.; Ciongradi, C.I.; Omar, T.M.; Hussain, F.; Jawad, M.J.; Castillo-Acobo, R.Y.; et al. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes (Dex): Underlying the role of exosomes derived from diverse DC subtypes in cancer pathogenesis. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2024, 254, 155097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiji MM; Milane LS. Cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Academic Press. 2021.

- Romagnoli, G.G.; Zelante, B.B.; Toniolo, P.A.; Migliori, I.K.; Barbuto, J.A.M. Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosomes may be a Tool for Cancer Immunotherapy by Converting Tumor Cells into Immunogenic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2015, 5, 692–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achouri, I.E.; Rhoden, A.; Hudon, S.; Gosselin, R.; Simard, J.-S.; Abatzoglou, N. Non-invasive detection technologies of solid foreign matter and their applications to lyophilized pharmaceutical products: A review. Talanta 2021, 224, 121885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risha, Y.; Minic, Z.; Ghobadloo, S.M.; Berezovski, M.V. The proteomic analysis of breast cell line exosomes reveals disease patterns and potential biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskov, H.; Orhan, A.; Christensen, J.P.; Gögenur, I. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaki, T.; Kubo, M.; Onishi, H.; Hirano, T.; Morisaki, S.; Eto, M.; Monji, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Efficacy of Intranodal Neoantigen Peptide-pulsed Dendritic Cell Vaccine Monotherapy in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors: A Retrospective Analysis. Anticancer. Res. 2021, 41, 4101–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, Z.; Qi, X. Dendritic cell derived exosomes loaded neoantigens for personalized cancer immunotherapies. J. Control. Release 2022, 353, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanlikilicer , P. Exosome-related methods and potential use as vaccines. Methods Mol Biol. 2022, 2435, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, B.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, K.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H. Complete remission of tumors in mice with neoantigen-painted exosomes and anti-PD-1 therapy. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 3579–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, O.; Betzer, O.; Elmaliach-Pnini, N.; Motiei, M.; Sadan, T.; Cohen-Berkman, M.; Dagan, O.; Popovtzer, A.; Yosepovich, A.; Barhom, H.; et al. ‘Golden’ exosomes as delivery vehicles to target tumors and overcome intratumoral barriers: in vivo tracking in a model for head and neck cancer. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Liu, H.; Yan, H.; Che, R.; Jin, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Yang, H.; Ge, K.; Liang, X.-J.; et al. A CAR T-inspiring platform based on antibody-engineered exosomes from antigen-feeding dendritic cells for precise solid tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2022, 282, 121424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, K.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Huang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, W.; Weng, J.; Du, X.; Wu, K.; Lai, P. Optimizing CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors: current challenges and potential strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Schellenberg, S.J.; Demeros, A.; Lin, A.Y. Exosomes in review: A new frontier in CAR-T cell therapies. Neoplasia 2025, 62, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Yang, W.; Nagaoka, K.; Huang, G.L.; Miyazaki, T.; Hong, T.; Li, S.; Igarashi, K.; Takeda, K.; Kakimi, K.; et al. An IL-12-Based Nanocytokine Safely Potentiates Anticancer Immunity through Spatiotemporal Control of Inflammation to Eradicate Advanced Cold Tumors. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Ma, J.; Yu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Song, Z.; Li, J. Exosomes as carriers to stimulate an anti-cancer immune response in immunotherapy and as predictive markers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 232, 116699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.; Shin, S.; Baek, M.-C.; Yea, K. Modification of immune cell-derived exosomes for enhanced cancer immunotherapy: current advances and therapeutic applications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar R; García A; Martínez M; et al. Estudio de los efectos de la quimioterapia combinada en modelos experimentales de cáncer. Revista de Investigación Científica. 2020; 18(3):245–257.

- Jiang H; Wang Z; Xu X; et al. Therapeutic potential of targeting cancer stem cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2024; 24(1):315.

- Qian, L.; Yu, S.; Yin, C.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Z.; Meng, Z.; Wang, P. Plasma IFN-γ-inducible chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 correlate with survival and chemotherapeutic efficacy in advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology 2019, 19, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi C; Bae S; Lee J; et al. Clinical significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022; 14(3):758.

- Calderón M; Silva J; González A; et al. Inmunoterapia en el tratamiento del cáncer de pulmón. Rev Med Chil. 2020; 148(7):970–978.

- Wu, Y.; Han, W.; Dong, H.; Liu, X.; Su, X. The rising roles of exosomes in the tumor microenvironment reprogramming and cancer immunotherapy. Medcomm 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.-N.; Xia, B.-R.; Jin, M.-Z.; Jin, W.-L.; Lou, G. Exosomes: Powerful weapon for cancer nano-immunoengineering. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 186, 114487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.; Msallam, R. Tissues and Tumor Microenvironment (TME) in 3D: Models to Shed Light on Immunosuppression in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang L; Sun S; Li X; et al. Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors and their combination strategies in cancer therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2024; 12(1):e00582.

- Sosnowska, A.; Chlebowska-Tuz, J.; Matryba, P.; Pilch, Z.; Greig, A.; Wolny, A.; Grzywa, T.M.; Rydzynska, Z.; Sokolowska, O.; Rygiel, T.P.; et al. Inhibition of arginase modulates T-cell response in the tumor microenvironment of lung carcinoma. OncoImmunology 2021, 10, 1956143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Rong, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ge, S.; Wu, T.; Lai, Y.; Xu, Q.; Guo, W.; et al. IDO1 Inhibition Promotes Activation of Tumor-intrinsic STAT3 Pathway and Induces Adverse Tumor-protective Effects. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiatz-Bittencourt, V.; Finlay, D.K.; Gardiner, C.M. Canonical TGF-β Signaling Pathway Represses Human NK Cell Metabolism. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 3934–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgoffe, G. Cancer metabolism and the immune system. American Association for Cancer Research. 2021.

- Zemanek, T.; Danisovic, L.; Nicodemou, A. Exosomes, their sources, and possible uses in cancer therapy in the era of personalized medicine. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 151, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, E.; Zhu, Z.; Wahed, S.; Qu, Z.; Storkus, W.J.; Guo, Z.S. Epigenetic modulation of antitumor immunity for improved cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Yagyu, S.; Hirota, S.; Tomida, A.; Kondo, M.; Shigeura, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Tanaka, M.; Nakazawa, Y. Autologous antigen-presenting cells efficiently expand piggyBac transposon CAR-T cells with predominant memory phenotype. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 21, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, R. PLAC8 is an innovative biomarker for immunotherapy participating in remodeling the immune microenvironment of renal clear cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1207551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Kryczek, I.; Nagarsheth, N.; Zhao, L.; Wei, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, E.; Vatan, L.; Szeliga, W.; et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature 2015, 527, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beumer-Chuwonpad, A.; Taggenbrock, R.L.R.E.; Ngo, T.A.; van Gisbergen, K.P.J.M. The Potential of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells for Adoptive Immunotherapy against Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López A; García R; Mendoza F. Inmunoterapia: Avances y desafíos en el tratamiento del cáncer. Cibamanz. 2021.