Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

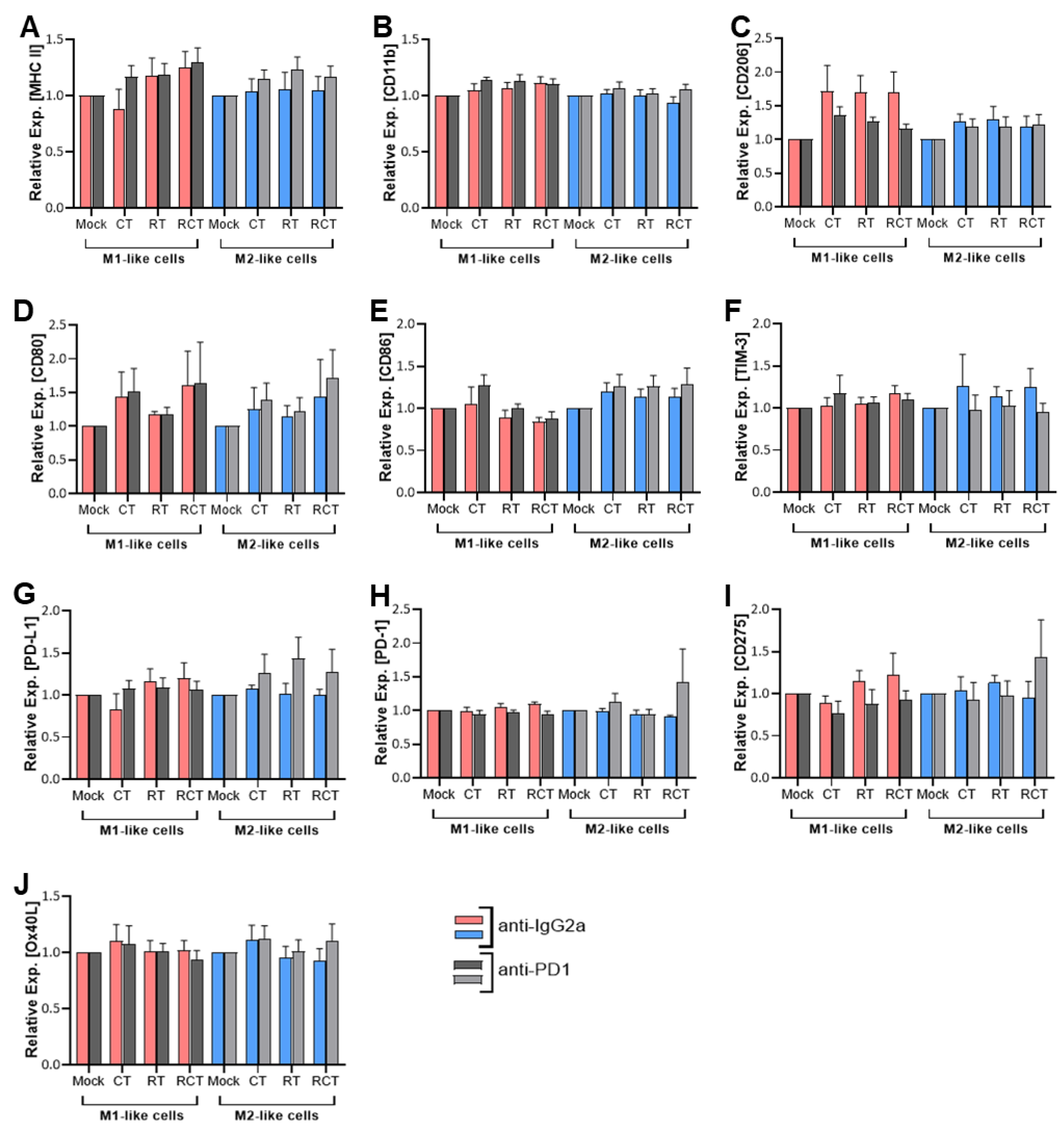

2.1. Neither Chemoradiation of Glioblastoma Cells nor PD-1 Blockade Affects the Differentiation Status or Immune Checkpoint Expression of M1- and M2-Like Cells

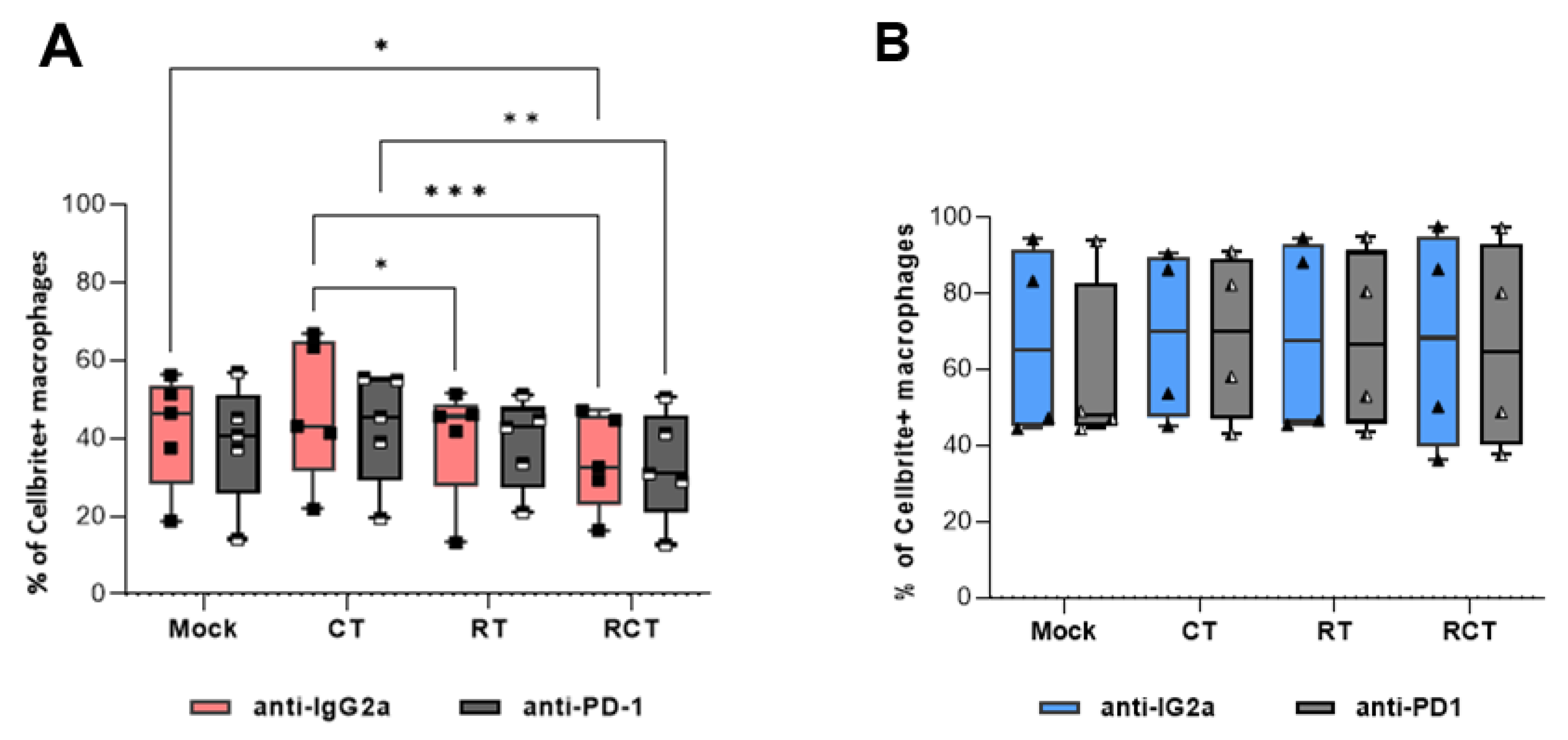

2.2. M2-Like Macrophages Have a Higher Capacity to Phagocytize Tumor Cells Than M1-Like Macrophages, Regardless of Tumor Cell Treatment

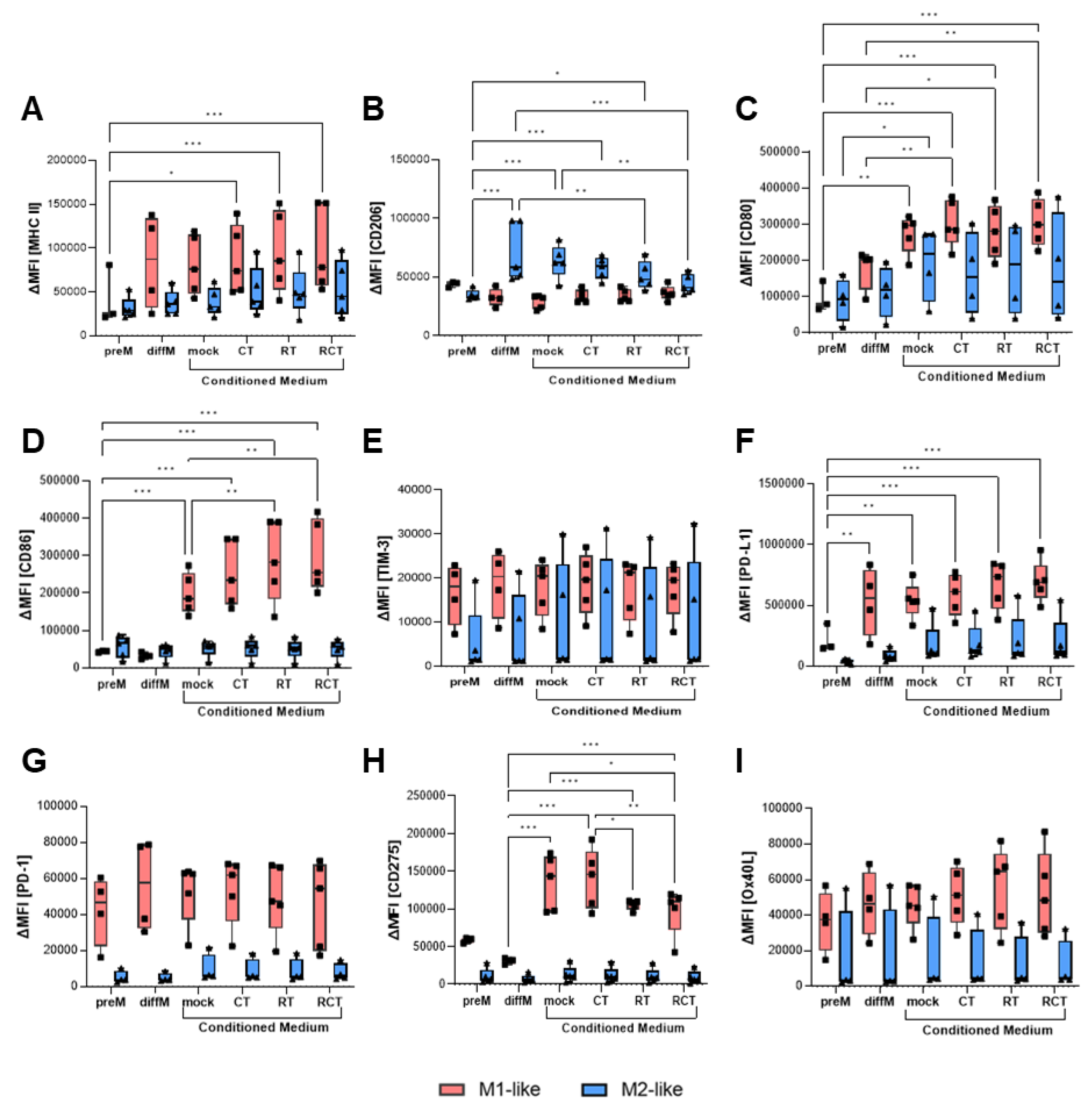

2.3. The Altered Micromilieu of Treated Tumor Cells Significantly Impacts M1-Like Macrophage Activation and Immune Checkpoint Surface Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Line Culture and Treatment of Glioblastoma Cells

4.2. Animals

4.3. Generation of M1-Like and M2-Like Macrophages

4.4. Conditioned Medium Assay of M1-Like and M2-Like Macrophages

4.5. Phagocytosis Assay

4.6. Flow Cytometric Analyses

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | blood brain barrier |

| C57BL/6 | wildtype mouse strain |

| CD | cluster of differentiation |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CT | chemotherapy |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Antigen 4 |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| GBM | glioblastoma multiforme |

| ICOS-L | Inducible costimulator-ligand |

| IFN-γ | interferon-gamma |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MDSC | myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| MFI | mean fluorescence intensity |

| MHC II | Major Histocompatibility Complex II |

| OS | overall survival |

| OX40L | CD252 |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein Ligand 1 |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| RCT | combination of RT and CT/ chemoradiation |

| RT | radiotherapy |

| TAM | tumor-associated macrophage |

| TIM-3 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TMZ | temozolomide |

| Treg | regulatory T cell |

References

- Politis, A.; Stavrinou, L.; Kalyvas, A.; Boviatsis, E.; Piperi, C. Glioblastoma: molecular features, emerging molecular targets and novel therapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2025, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, P.; Penninger, J.M.; Timms, E.; Wakeham, A.; Shahinian, A.; Lee, K.P.; Thompson, C.B.; Griesser, H.; Mak, T.W. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science 1995, 270, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derer, A.; Spiljar, M.; Baumler, M.; Hecht, M.; Fietkau, R.; Frey, B.; Gaipl, U.S. Chemoradiation Increases PD-L1 Expression in Certain Melanoma and Glioblastoma Cells. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, J.; Ladinig, A.; Fietkau, R.; Putz, F.; Gaipl, U.S.; Frey, B.; Derer, A. Normofractionated irradiation and not temozolomide modulates the immunogenic and oncogenic phenotype of human glioblastoma cell lines. Strahlenther Onkol 2023, 199, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, J.S.; Paliwal, S.; Singhvi, G.; Taliyan, R. Immunological challenges and opportunities in glioblastoma multiforme: A comprehensive view from immune system lens. Life Sci 2024, 357, 123089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, X.; Herting, C.J.; Garcia, V.A.; Nie, K.; Pong, W.W.; Rasmussen, R.; Dwivedi, B.; Seby, S.; Wolf, S.A.; et al. Cellular and Molecular Identity of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 2266–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Beumer-Chuwonpad, A.; Westerman, B.; Garcia Vallejo, J. P02.05.A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF TUMOR-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGES IN GLIOBLASTOMA. Neuro-Oncology 2024, 26, v35–v35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvisten, M.; Mikkelsen, V.E.; Stensjoen, A.L.; Solheim, O.; Van Der Want, J.; Torp, S.H. Microglia and macrophages in human glioblastomas: A morphological and immunohistochemical study. Mol Clin Oncol 2019, 11, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, T.; Wei, H.; Xu, X.; He, S.; Chen, S.; Shi, Z.; et al. Corrigendum to "New Mechanisms of Tumor-Associated Macrophages on Promoting Tumor Progression: Recent Research Advances and Potential Targets for Tumor Immunotherapy". J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 6728474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoultre, M.; Dutoit, V.; Walker, P.R. Phagocytic function of tumor-associated macrophages as a key determinant of tumor progression control: a review. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, A.J.; Elsawa, S.F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.R.; Maute, R.L.; Dulken, B.W.; Hutter, G.; George, B.M.; McCracken, M.N.; Gupta, R.; Tsai, J.M.; Sinha, R.; Corey, D.; et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature 2017, 545, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.S.; Chew, V.; Sieow, J.L.; Goh, S.; Yeong, J.P.; Soon, A.L.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P. PD-1 expression on dendritic cells suppresses CD8(+) T cell function and antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1085146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, M.; Xiao, P.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, K. Targeting immune checkpoints on tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1199631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, T.; Lawrence, T.; McNeish, I.; Charles, K.A.; Kulbe, H.; Thompson, R.G.; Robinson, S.C.; Balkwill, F.R. "Re-educating" tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutolo, M.; Campitiello, R.; Gotelli, E.; Soldano, S. The Role of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovitis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 867260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melichar, B.; Nash, M.A.; Lenzi, R.; Platsoucas, C.D.; Freedman, R.S. Expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and their receptors CD28, CTLA-4 on malignant ascites CD3+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) from patients with ovarian and other types of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2000, 119, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.H.; Hernández-Verdin, I.; Bielle, F.; Verreault, M.; Lerond, J.; Alentorn, A.; Sanson, M.; Idbaih, A. Expression and Prognostic Value of CD80 and CD86 in the Tumor Microenvironment of Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. Can J Neurol Sci 2023, 50, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrilo, J.; Velde, S.V.; Henin, C.; Denanglaire, S.; Azouz, A.; Boon, L.; Van den Eynde, B.J.; Moser, M.; Goriely, S.; Leo, O. Interferon-γ driven differentiation of monocytes into PD-L1+ and MHC II+ macrophages and the frequency of Tim-3+ tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells within the tumor microenvironment predict a positive response to anti-PD-1-based therapy in tumor-bearing mice. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, L.M.; Peyret, V.; Viano, M.E.; Geysels, R.C.; Chocobar, Y.A.; Volpini, X.; Pellizas, C.G.; Nicola, J.P.; Motran, C.C.; Rodriguez-Galan, M.C.; et al. TIM3 Expression in Anaplastic-Thyroid-Cancer-Infiltrating Macrophages: An Emerging Immunotherapeutic Target. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagata, M.; Okayama, H.; Nakajima, S.; Saito, K.; Sato, T.; Sakuma, M.; Fukai, S.; Endo, E.; Sakamoto, W.; Saito, M.; et al. TIM-3 Expression and M2 Polarization of Macrophages in the TGFbeta-Activated Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, P.; Liang, T.; Wang, L.; Hu, L. TIM-3 is a potential prognostic marker for patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 31705–31713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Dong, B.; Yi, M.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K. Prognostic Values of TIM-3 Expression in Patients With Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis and Database Evaluation. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solinas, C.; Gu-Trantien, C.; Willard-Gallo, K. The rationale behind targeting the ICOS-ICOS ligand costimulatory pathway in cancer immunotherapy. ESMO Open 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, F.; Shan, A. Transcriptome profile and clinical characterization of ICOS expression in gliomas. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 946967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Feldman, S.; Daana, B.; Elkis, L.; Mendelovic, S.; Avraham, A. 188P Expression of the co-stimulatory checkpoint protein OX40L (TNFSF4) in the melanoma micro-environment. Immuno-Oncology and Technology 2023, 20, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibahara, I.; Saito, R.; Zhang, R.; Chonan, M.; Shoji, T.; Kanamori, M.; Sonoda, Y.; Kumabe, T.; Kanehira, M.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. OX40 ligand expressed in glioblastoma modulates adaptive immunity depending on the microenvironment: a clue for successful immunotherapy. Molecular Cancer 2015, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badie, B.; Schartner, J.M. Flow cytometric characterization of tumor-associated macrophages in experimental gliomas. Neurosurgery 2000, 46, 957–961; discussion 961-952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol 2003, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, A.C.; Badie, B. Microglia and macrophages in malignant gliomas: recent discoveries and implications for promising therapies. Clin Dev Immunol 2013, 2013, 264124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, N.A.; Holland, E.C.; Gilbertson, R.; Glass, R.; Kettenmann, H. The brain tumor microenvironment. Glia 2012, 60, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komohara, Y.; Ohnishi, K.; Kuratsu, J.; Takeya, M. Possible involvement of the M2 anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in growth of human gliomas. J Pathol 2008, 216, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, J.; Jeong, M.; Nam, D.; Rhee, I. Emerging strategies for targeting tumor-associated macrophages in glioblastoma: A focus on chemotaxis blockade. Life Sci 2025, 376, 123762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Xue, L. Expression of tumor-associated macrophage in progression of human glioma. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014, 70, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fu, W.J.; Chen, X.Q.; Wang, S.; Deng, R.S.; Tang, X.P.; Yang, K.D.; Niu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.R.; et al. Autophagy-based unconventional secretion of HMGB1 in glioblastoma promotes chemosensitivity to temozolomide through macrophage M1-like polarization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, F.; Augello, F.R.; Artone, S.; Ciafarone, A.; Topi, S.; Cifone, M.G.; Cinque, B.; Palumbo, P. Involvement of Cyclooxygenase-2 in Establishing an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Tumorspheres Derived from TMZ-Resistant Glioblastoma Cell Lines and Primary Cultures. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tao, X.; Ji, B.; Gong, J. Hypoxia-Driven M2-Polarized Macrophages Facilitate Cancer Aggressiveness and Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 1614336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Li, L.; Hao, Y.; Tang, M.; Cao, C.; He, J.; Wang, L.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. NAD+ Metabolism Reprogramming Mediates Irradiation-Induced Immunosuppressive Polarization of Macrophages. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2025, 121, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Shen, Q.; Hou, Y.; Xia, Y.X.; Li, L.; Chang, L.; Li, W.H. Irradiated lung cancer cell-derived exosomes modulate macrophage polarization by inhibiting MID1 via miR-4655-5p. Mol Immunol 2023, 155, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becherini, C.; Lancia, A.; Detti, B.; Lucidi, S.; Scartoni, D.; Ingrosso, G.; Carnevale, M.G.; Roghi, M.; Bertini, N.; Orsatti, C.; et al. Modulation of tumor-associated macrophage activity with radiation therapy: a systematic review. Strahlenther Onkol 2023, 199, 1173–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, H.; Klug, F.; Nadella, V.; Mazumdar, V.; Schmitz-Winnenthal, H.; Umansky, L. Low doses of gamma irradiation potentially modifies immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by retuning tumor-associated macrophages: lesson from insulinoma. Carcinogenesis 2016, 37, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hutter, G.; Kahn, S.A.; Azad, T.D.; Gholamin, S.; Xu, C.Y.; Liu, J.; Achrol, A.S.; Richard, C.; Sommerkamp, P.; et al. Anti-CD47 Treatment Stimulates Phagocytosis of Glioblastoma by M1 and M2 Polarized Macrophages and Promotes M1 Polarized Macrophages In Vivo. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0153550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, R.; Hyoung Lee, J.; Hayashi, M.; Dianzani, U.; Ofune, K.; Maruyama, M.; Oe, S.; Ito, T.; Hashiba, T.; Yoshimura, K.; et al. ICOSLG-mediated regulatory T-cell expansion and IL-10 production promote progression of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2020, 22, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).