1. Introduction

Cadmium is a non-essential element for plants and a highly toxic heavy metal that poses a serious threat to plant growth, agricultural productivity, and human health due to its strong mobility and bioaccumulation potential in the food chain. Even at low concentrations, Cd interferes with photosynthetic metabolism, nutrient uptake, and redox homeostasis, leading to growth inhibition and yield loss in crops [

1,

2].

Cd toxicity disrupts cellular metabolism by inducing the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and superoxide radicals (O₂•⁻), which damage membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids through lipid peroxidation [

2]. Excessive Cd accumulation also disrupts chlorophyll biosynthesis, inhibits root elongation, alters the uptake of essential mineral nutrients (e.g., K⁺, Ca²⁺, Fe, Zn, Mn), and reduces enzymatic activity, impairing plant physiology and growth [

3,

4].

Plants have evolved multiple defense strategies to mitigate Cd toxicity, including the activation of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), synthesis of metal-chelating molecules (phytochelatins, metallothioneins), and regulation of metal transporters to limit Cd translocation [

5,

6]. However, the efficiency of these mechanisms may vary among species and cultivars, and exogenous application of signaling molecules could often be required to enhance tolerance. Among these, NO has emerged as a key signaling mediator involved in plant responses to abiotic stress, including heavy-metal exposure [

7,

8,

9].

NO regulates a broad range of physiological processes by modulating gene expression [

10], antioxidant activity, and ion homeostasis [

9]. Under metal stress, NO has been shown to alleviate oxidative damage by scavenging ROS, stabilizing membranes, and enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes [

11]. Additionally, NO interacts with sulfur metabolism and promotes phytochelatin biosynthesis, facilitating Cd sequestration in roots and vacuoles [

12]. Exogenous application of NO donors such as SNP has proven effective in mitigating Cd toxicity in several crops, including mung bean [

12], rice [

13,

14], and castor bean [

15]. However, information on the physiological and biochemical roles of Cd in lettuce, a leafy vegetable highly sensitive to Cd accumulation, is still limited.

Lettuce is among the most commonly consumed vegetables globally. Despite being naturally low in calories, fats, and sodium, it provides considerable nutritional value, serving as an important source of dietary fiber, iron, folate, vitamin C, and various health-promoting bioactive compounds [

16]. However, lettuce is also recognized for its tendency to accumulate heavy metals within its edible tissues [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Variations in Cd accumulation and tolerance among lettuce varieties have been reported [

20,

21]. Yet, limited information is available regarding the interactive effects of Cd and SNP on different morphological types, such as the curly (var.

crispa), the romaine (var.

longifolia), and the iceberg (var.

capitata) lettuces. Understanding these responses is crucial not only for improving crop tolerance but also for ensuring food safety under conditions of increasing soil contamination.

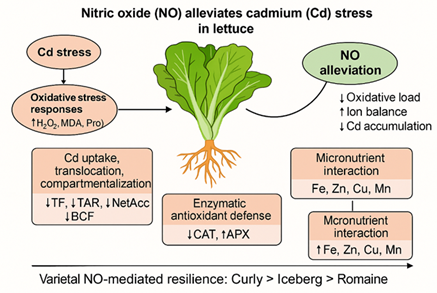

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the physiological, biochemical, and ionic responses of three lettuce varieties to Cd-induced stress and to evaluate the potential protective role of exogenous NO supplied as SNP. Specifically, we examined changes in (i) growth and photosynthetic pigments, (ii) oxidative stress markers (H₂O₂, MDA, proline, membrane permeability), (iii) antioxidant enzyme activities (CAT, APX), (iv) ionic homeostasis (K⁺, Ca²⁺, Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn), and (v) Cd accumulation and detoxification indices (TF, TAR, BCF, NetAcc). The findings provide mechanistic insight into the NO-mediated alleviation of Cd toxicity and reveal varietal differences in tolerance mechanisms, contributing to the development of Cd-resilient leafy vegetables with improved nutritional and physiological stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted during the 2023–2024 summer season in the experimental greenhouses of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kocaeli University (40°40′47″N, 30°01′37″E). The greenhouse conditions were maintained at an average temperature of 27 °C (day) and 17 °C (night) and a relative humidity ranging from 48% to 76%.

Three lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) varieties were utilized in this study: the curly lettuce (var. crispa, cv. “Maritima”), the romaine lettuce (var. longifolia, cv. “Yedikule”), and the iceberg lettuce (var. capitata, cv. “Saula”). Uniform three-week-old seedlings, corresponding to the 3–4 leaf stage, were procured from a commercial nursery (PAK Fide, Yalova, Türkiye). Just before transplantation, the roots of all seedlings were carefully rinsed with distilled water to remove residual peat and other debris, ensuring a clean root system. Each plant was then transplanted individually into a two-liter plastic pot containing perlite as an inert growth medium. The use of perlite provided a uniform and well-aerated medium, minimizing the potential effects of soil variability on plant growth and physiological responses.

After transplanting, seedlings were watered first with quarter-strength (five days) and then half-strength (three days) modified Hoagland’s nutrient solution for acclimatization. In the following days, they were watered with full-strength modified Hoagland’s nutrient solution until the end of the study.

The composition of the full-strength Hoagland solution was as follows: (in mM) 5 Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O, 5 KNO₃, 2 MgSO₄·7H₂O, 1 KH₂PO₄, and (in µM) 45.5 H₃BO₃, 44.7 FeSO₄·7H₂O, 30 NaCl, 9.1 MnSO₄·H₂O, 0.77 ZnSO₄·7H₂O, 0.32 CuSO₄·5H₂O, 0.10 (NH₄)₂Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O, and 54.8 Na₂EDTA·2H₂O [

22]. The nutrient solution pH was adjusted to 6.5 using NaOH or HCl.

Plants were subjected to six treatments for 28 days using full-strength modified Hoagland’s solution: i) Control (nutrient solution only), ii) Cd100 (100 µM Cd as CdCl₂), ii) Cd500 (500 µM Cd as CdCl₂), iv) SNP (200 µM sodium nitroprusside, Na₂ [Fe (CN) ₅NO]·2H₂O), v) Cd100 + SNP (100 µM Cd + 200 µM SNP), and vi) Cd500 + SNP (500 µM Cd + 200 µM SNP).

2.2. Sampling and Harvest of Plants

After 28 days from treatments, plants were harvested at the end of the vegetative growth phase (approximately 6–8 weeks for lettuce). Shoots were carefully cut at the substrate surface and weighed to determine fresh weight (FW). Roots were separated from the perlite medium, rinsed thoroughly, and weighed to obtain root FW.

All plant tissues were washed with tap water, followed by three rinses with deionized water to remove surface contaminants. All samples were oven-dried at 70 °C until constant weight and then cooled in a desiccator before determining dry weight (DW). The dried materials were ground into fine powder and stored in airtight containers for further elemental and physiological analyses.

2.3. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

Chlorophyll (Chl

a, Chl

b, Chl

a+b) and carotenoid (Car) contents were determined in fully expanded young leaves before harvest. Fresh leaf tissue (0.25 g) was homogenized in 10 mL of 90% (v/v) acetone and filtered. Absorbance was recorded at 663, 645, 652, and 470 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1201, Kyoto, Japan). Pigment concentrations were calculated according to [

23].

2.4. Determination of Membrane Damage

Membrane permeability (MP) was assessed by electrolyte leakage following [

24]. Fresh leaves were washed, cut into 1 cm pieces, and incubated in 10 mL of deionized water at 30 °C for 3 h. The electrical conductivity (C1) was measured, after which the samples were boiled for 2 min, cooled to room temperature, and re-measured (C2). The MP was calculated by using equation 1.

where: C1 and C2 are the electrolyte conductivities measured before and after boiling, respectively.

Lipid peroxidation was quantified as malondialdehyde (MDA) content following [

25]. Leaf tissue (0.25 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of 0.1% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 min. To 1 mL of supernatant, 4 mL of 20% TCA containing 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was added. The mixture was heated at 95 °C for 15 min, cooled, and centrifuged again. Absorbance was measured at 532 nm and corrected at 600 nm. MDA content was calculated using an extinction coefficient of ε = 155 mM⁻¹ cm⁻¹.

2.5. Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide Content and Proline Accumulation

Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) was quantified according to [

26]. Leaf samples (0.25 g) were homogenized in 5 mL of cold acetone and filtered. A 1 mL aliquot was mixed with 4 mL of titanium reagent [0.06% TiO₂ (w/v), 0.6% K₂SO₄ (w/v), and 10% H₂SO₄ (v/v)] followed by 5 mL of concentrated ammonia solution. After centrifugation (10,000 5 min), the absorbance of the yellow supernatant was measured at 415 nm. H₂O₂ concentration was determined using a standard curve (100–1000 nmol H₂O₂).

Free proline content was determined using the ninhydrin method [

27]. Fresh leaf tissue (0.25 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of 3% (w/v) sulfosalicylic acid, and the reaction product was quantified colorimetrically.

2.6. Enzyme Extraction and Assay

Fully expanded leaves (1.0 g) were homogenized in 5 mL of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM EDTA-Na₂ and 1 mM ascorbic acid (to stabilize ascorbate peroxidase activity [

28]. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for enzyme assays. All spectrophotometric measurements were performed at 25 °C.

Catalase (CAT; EC 1.11.1.6) activity was determined according to [

29]. The reaction mixture (2.5 mL) contained 50 mM KH₂PO₄ buffer (pH 7.0) and 1.5 mM H₂O₂. The decrease in absorbance at 240 nm was recorded for 1 min, and activity was calculated using ε = 40 mM⁻¹ cm⁻¹.

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX; EC 1.11.1.11) activity was assayed according to [

30]. The reaction mixture (3 mL) contained 50 mM KH₂PO₄ buffer (pH 7.0), 0.05 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 mM EDTA-Na₂, and 1.5 mM H₂O₂. The decrease in absorbance at 290 nm was monitored for 1 min, using ε = 2.8 mM⁻¹ cm⁻¹.

2.7. Determination of Concentrations, Accumulations, and Translocations

For Cd analysis, 0.5 g of dried shoot or root tissue was ashed at 500 °C for 6 h in a muffle furnace. After cooling, the ash was dissolved in 5 mL of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution [

31] for ion analysis. The ion concentrations were quantified using an inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES; PerkinElmer Optima 2100 DV, Waltham, MA, USA).

The Cd accumulation capacity of plants was evaluated based on the bioconcentration factor (BCF), the translocation factor (TF), and the total accumulation rate (TAR). The BCF is defined as the ratio of the total metal concentration in the aerial parts to the metal concentration in the rooting media, and it is accepted as an indicator of the ability to absorb metals and transport them to the shoots [

32]. The BCF was calculated by using Equation 2. The TF value is defined as the ratio of heavy metal concentration in the shoot to that in the root [

32] and is calculated using Equation 3. The TAR, a useful parameter for bioaccumulation studies, measures plants’ heavy metal uptake [

33] and is calculated using Equation 4.

where: Cd

shoot and Cd

root denote the Cd concentrations in shoot and root tissues, respectively. Total Cd

growth media respect concentration is added to the modified Hoagland nutrient solution.

where: [

Cd shoot] and [

Cd root] are the Cd concentrations in shoot and root tissues, respectively. [

DWshoot] and [

DWroot] denote shoot and root dry weights. [

Growth day] respects the vegetative growth phase for lettuce (48 days).

The net ion accumulation (NetAcc) via roots is the rate of total ion quantities in the whole plant to root DW and was calculated by using Equation 5 [

34].

where: [

DWroot] denotes root dry weights. [

Total ion] reflects the total amount of ions in the whole plant.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design with three replications. Data normality was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using MINITAB (Version 16; Minitab Inc., State College, Pennsylvania, USA). Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to evaluate the relationships among physiological and biochemical parameters in shoots and roots. Correlation matrices were generated using XLSTAT 2023. Mean separations were conducted using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a 5% significance level (α = 0.05). Significance levels were denoted as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), and ns (not significant).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Cd and SNP on Biomass Accumulation in Lettuce Varieties

The Cd exposure caused a dose-dependent reduction in biomass accumulation in all lettuce varieties. Both FW and DW of shoots and roots were markedly suppressed under Cd stress, reflecting the metal’s strong phytotoxic effects (

Figure 1).

In the curly lettuce, shoot FW declined by 28.4% (Cd100) and 57.4% (Cd500) relative to the control. SNP application alone showed a slight decrease (-19.7%), whereas the Cd+SNP combinations improved shoot FW by 22.3% (Cd500+SNP) compared with Cd500 alone. Similarly, in the romaine lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 reduced shoot FW by 45.2% and 65.1%, respectively; however, SNP co-treatment restored biomass substantially, with increases of 47.5% (Cd100+SNP) and 84.6% (Cd500+SNP) compared with Cd100 and Cd500, respectively. Additionally, in the iceberg, the decreases were the most pronounced (-40.7% and -71.3% for Cd100 and Cd500), yet SNP improved shoot FW by 6.2% and 46.7% under Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively (

Figure 1A).

The Cd stress also suppressed root growth, but SNP alleviated this inhibition. In the curly lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 caused reductions of 12.4% and 28.3%, while Cd+SNP treatments enhanced root FW by 6.4% and 34.6%, respectively. In the romaine lettuce, Cd exposure caused stronger inhibition (-35.4% and -56.6%), but SNP addition resulted in striking recoveries of 46.9% (Cd100+SNP) and 80.8% (Cd500+SNP). The roots of the iceberg lettuce were particularly sensitive, showing a 57.2% decline under Cd500, yet improved by 13.5% and 61.2% with SNP supplementation under Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively (

Figure 1B).

The Cd treatments substantially reduced shoot DW in all varieties. In the curly lettuce, shoot DW decreased by 31.5% and 56.4% at Cd100 and Cd500, respectively, while the applied SNP with Cd increased it by 39.0% under Cd500+SNP application. The romaine lettuce exhibited a sharper decline (-55.7% and -64.7%), which was ameliorated by 36.3% and 37.4% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively. The iceberg lettuce showed reductions of 49.2% (Cd100) and 72.5% (Cd500), but the combined treatments improved shoot DW by 11.4% and 52.4% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively (

Figure 1C).

Root DWs followed similar patterns with applications. In the curly lettuce, Cd exposure reduced root DW by 13.3% and 18.0% with Cd100 and Cd500, respectively, while SNP improved it by 6.5% and 19.7% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively. The romaine lettuce experienced a 33.8% and 52.7% decrease with Cd100 and Cd500, respectively, mitigated by 28.5–41.4% alleviation after SNP addition (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively). In the iceberg lettuce, Cd application caused up to 45.1% loss (Cd500) in root DW, but SNP mitigated 1.8% and 18.9% of the reduction with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively (

Figure 1D).

3.2. Effects of Cd and SNP on Photosynthetic Pigment Contents in Lettuce Varieties

The Cd exposure caused a considerable decline in photosynthetic pigment contents in all lettuce varieties (

Figure 2). The degree of reduction was dose-dependent and varied among varieties. Excess Cd significantly depressed Chl

a in all varieties. The curly lettuce showed 30.5% and 47.8% decreases in Chl

a with Cd100 and Cd500, respectively, while SNP ameliorated Chl

a by 93.6% and 131.6% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively. The romaine lettuce displayed 46.0% declines under both Cd application (Cd100 and Cd500), but mitigated 47.5% and 59.9% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively. The iceberg lettuce experienced 47.3% and 63.7% decreases with Cd500, respectively; however, SNP supplementation led to remarkable recovery (89.6% and 169.6% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively) (

Figure 2A).

Similar patterns were observed for Chl

b in all lettuce varieties. Applied Cd100 and Cd500 caused a significant reduction of 45.6% and 43.7% in the curly lettuce, of 28.0% and 24.7% in the romaine, and of 49.6% and 68.8% in the iceberg. SNP co-application (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP) mitigated pigment levels by 72.4% and 118.8% in the curly, by 11.9% and 21.4% in the romaine, and by 62.0% and 200.6% in the iceberg (

Figure 2B).

Applied Cd100 and Cd500 stress lowered Chl

a+b content by 34.0% and 46.9% in the curly, by 42.4% and 41.9% in the romaine, and by 47.8% and 64.9% in the iceberg lettuce. SNP addition (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP) improved Chl

a+b by 98.2% and 117.4% in the curly, by 38.8% and 51.0% in the romaine, and by 83.3% and 176.3% in the iceberg lettuce, compared to the Cd100 and Cd500 alone (

Figure 2C).

Carotenoid content also declined under Cd stress by 12.1%–5.4% across all varieties. Applied SNP with Cd100 and Cd500 alleviated these reductions, enhancing Car by 52.0% and 81.2% in the curly, by 42.8% and 42.5% in the romaine, and 83.3% and 125.3% in the iceberg lettuce, respectively (

Figure 2D).

3.3. Effects of Cadmium and SNP on Oxidative Stress Markers in Lettuce Varieties

The Cd exposure markedly increased oxidative stress indicators, including H₂O₂ and MDA, while SNP partially modulated these responses, influenced osmolyte accumulation, and membrane permeability in a genotype-dependent manner (

Figure 3).

Cd treatment led to a strong accumulation of H₂O₂ in all lettuce varieties. In the curly lettuce variety, H₂O₂ increased by 3.2-fold (Cd100) and 5.4-fold (Cd500) compared to the control. SNP co-application slightly mitigated these increases, reducing H₂O₂ by 58.9% at Cd100+SNP, while at Cd500+SNP levels remained close to Cd alone. In the romaine variety, Cd exposure unexpectedly reduced H₂O₂ content by 16.4% (Cd100) and 29.2% (Cd500), whereas SNP supplementation caused minor recoveries of 24.3% and 29.9% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications, respectively, compared to the Cd100 and Cd500 alone. In the iceberg variety, H₂O₂ accumulation increased by 3.3-fold and 3.7-fold more under Cd stress (Cd100 and Cd500, respectively) and slightly decreased with SNP co-treatment (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP), improving the toxic effect of Cd100 and Cd500 by 9.7% and 4.7%, respectively, indicating limited modulation of ROS levels by NO (

Figure 3A).

The Cd stress significantly elevated MDA content in all varieties. In the curly lettuce, MDA content increased by 38.9% (Cd100) and 87.9% (Cd500), while SNP co-application decreased MDA by 17.1–39.1% relative to Cd100 and Cd500 alone. In the romaine, Cd100 and Cd500 increased MDA content by 25.4% and 24.0%, respectively; Cd100+SNP reduced this parameter by 8.2%, compared to Cd100 alone. The iceberg lettuce exhibited the highest peroxidation, with 2.2-fold and 2.6-fold more than the control groups under Cd100 and Cd500, respectively; however, SNP application lowered MDA by 6.8% and 19.9% under Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP treatments, respectively (

Figure 3B).

The Cd exposure markedly affected proline accumulation and membrane permeability across all lettuce varieties, although the magnitude of these responses varied among genotypes (

Figure 4). In the curly lettuce, proline content increased substantially under Cd stress, reaching 82.7% and 103.0% above control levels at 100 and 500 µM Cd, respectively. The application of SNP alone also increased proline by 50.5%, indicating that NO is involved in osmotic adjustment. When combined with Cd, SNP alleviated Cd-induced proline accumulation, reducing it by 28.3% and 4.3% at Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively. In contrast, the romaine lettuce showed a considerable decline in proline levels under Cd stress (71.3% and 60.5%). SNP treatment promoted proline accumulation compared to the Cd-only treatments, particularly at Cd100+SNP (+26.5%), implying an ameliorative NO-mediated effect. In the iceberg lettuce, proline contents decreased under Cd100 and Cd500 applications (43.6% and 53.9%, respectively), while SNP applications (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP) moderately counteracted these reductions (-35.1% and -51%, respectively) (

Figure 4A). Similarly, Cd exposure significantly affected MP percentage, a key indicator of cellular integrity. In the curly lettuce, MP increased by 37.0% at Cd100 but only 4.6% at Cd500. The presence of SNP reduced MP by 14.4% and 3.8% under Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively. The romaine lettuce showed decreased MP under Cd100 and Cd500 treatments (22.7% and 25.6%, respectively), while further reduction occurred with SNP (Cd100+SNP: −39.9%; Cd500+SNP: −34.4%). In the iceberg lettuce, applying Cd100 and Cd500 reduced MP slightly (18.1% and 15.7%, respectively), whereas SNP alone had a minor influence. Notably, SNP co-application at Cd100+SNP increased MP by 18.2%, while Cd500+SNP decreased it by 16.3% (

Figure 4B).

3.4. Effects of Cadmium and SNP on Catalase (CAT) and Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) Activities

Applied Cd levels substantially influenced the activities of antioxidant enzymes, CAT and APX, in all lettuce varieties (

Figure 5). In the curly lettuce, CAT activity markedly increased under Cd stress, with increases of 125.3% and 96.0% over control values at 100 and 500 µM Cd, respectively. However, the application of SNP alone caused a drastic decline (99.9%). When combined with Cd100 and Cd500, SNP slightly reduced CAT activity (10.0% and 8.6%, respectively). In the romaine lettuce, CAT activity also increased significantly under Cd100 and Cd500 stress (114.2% and 101.4%, respectively), and SNP co-application further enhanced the activity, particularly at Cd500+SNP (44.5%). In the iceberg lettuce, Cd exposure induced a dose-dependent (Cd100 and Cd500) increase in CAT (39.2 and 137.5%, respectively), while SNP co-treatments promoted further activation (Cd100+SNP: 50.5%; Cd500+SNP: 1.0%) (

Figure 5A).

A similar genotype-dependent response was observed for APX activity. In the curly lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 applications slightly reduced APX activity (14.5% and 15.7%, respectively), while SNP alone caused a sharp inhibition (−97.8%). Notably, SNP co-application improved APX activity compared with Cd alone (Cd100+SNP: +21.1%; Cd500+SNP: +8.5%). In the romaine lettuce, Cd stress elevated APX by 60.6% at Cd100 but only 7.1% at Cd500, whereas SNP co-application (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP) caused a pronounced decrease (55.1% and 30.2%). Conversely, the iceberg lettuce exhibited slight declines under Cd100 and Cd500 by 14.7% and 16.4%, respectively, and SNP supplementation, particularly at Cd500+SNP, dramatically increased APX activity (71.4%) (

Figure 5B).

3.5. Effects of Cadmium and SNP on Concentration, Translocation, and Accumulation Parameters of Cadmium

The effects of Cd and SNP on concentrations and accumulation of cadmium in the curly, romaine, and iceberg lettuce varieties were significant (

Table 1). The Cd exposure caused an exceptionally high increase in shoot Cd concentrations in the curly lettuce. Cd100 increased shoot Cd 208-fold, while Cd500 resulted in a 411-fold increase compared to the control, indicating extremely high shoot mobility of Cd in this variety. The SNP application alone also had a notable effect on shoot Cd concentrations (+51.9%). Under Cd stress, SNP reduced shoot Cd accumulation by 55.4% at Cd100 and 19.0% at Cd500, limiting the increases to 93-fold and 332-fold, respectively. On the other hand, root Cd concentrations were found to be highly interesting, and all applications caused a considerable increase in root Cd concentrations in the curly lettuce. Cd100 increased root Cd by 67-fold, and Cd500 by 208-fold. SNP alone lowered root Cd by 21.4%. Since the SNP applied with Cd significantly mitigated Cd concentration, reducing root Cd by 32.1% at Cd100 and 22.3% at Cd500, compared to Cd levels alone.

The romaine lettuce showed lower shoot Cd accumulation than the curly lettuce. Cd100 increased shoot Cd 315-fold, and Cd500 increased it 371-fold. For Cd and SNP applications, Cd100+SNP lowered shoot Cd by 41.1% (from 315-fold to 185-fold), whereas Cd500+SNP showed only a mild mitigation (3.7%), decreasing the increase from 371-fold to 357-fold. The romaine roots accumulated considerably more Cd than the shoots. Cd100 caused a 99-fold increase, while Cd500 reached 243-fold. SNP alone slightly increased root Cd (21.3%). Strong mitigation occurred with SNP: 38.5% reduction at Cd100 and 36.8% at Cd500, lowering the increases to 61-fold and 154-fold, respectively (

Table 1).

In the iceberg lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 caused a 210-fold and 418-fold increase in shoot Cd concentration, respectively. SNP application alone caused a notable change (+21.6%). However, applied SNP together with Cd mitigated Cd concentrations strongly: Cd100+SNP reduced shoot Cd by 66.0%, and Cd500+SNP lowered it by 41.0%. On the other hand, the iceberg variety showed the lowest root Cd accumulation among the three varieties. Cd100 increased root Cd by 53-fold, and Cd500 by 156-fold. Remarkably, SNP alone reduced root Cd by 79.9%. Under Cd exposure, Cd100+SNP lowered root Cd by 52.9% (increased 25-fold), and Cd500+SNP reduced it by 16.3% (increased 130-fold) (

Table 1).

Both shoot and root BCF declined markedly under Cd stress, illustrating the metal’s inhibitory impact on uptake efficiency (

Table 1). In the curly lettuce, applied Cd levels (Cd100 and Cd500) decreased the shoot BCF (81.5% and 91.9%, respectively) and root BCF (94.0% and 64.3%, respectively). SNP alone increased shoot BCF (51.7%) but decreased root BCF (22.0%), while Cd+SNP combinations caused further reductions in shoot BCF (Cd100+SNP: 91.7% and Cd500+SNP: 94.1%) and in root BCF(Cd100+SNP: -95.9% and Cd500+SNP: 97.1%), demonstrating a strong NO-induced suppression of Cd uptake and internal transport. In the romaine, shoot BCF and root BCF decreased by 72% to 95%, and SNP intensified this decline (83% to 97%) compared to the control, suggesting that NO restricted Cd influx and translocation through transporter inhibition or cell-wall binding. The iceberg lettuce also exhibited sharp decreases in shoot BCF (81% to 93%) and root BCF (79% to 97%) under Cd100 and Cd500 stress, respectively; SNP co-application further suppressed both indices (to -97.8% and -97.7%), indicating an effective NO-mediated control of Cd entry into plant tissues.

Cd stress significantly increased the TF of Cd in all lettuce varieties, though the magnitude of increase varied by genotype (

Table 1). In the curly lettuce, TF of Cd increased sharply under Cd100 (3-fold) and Cd500 (2.2-fold) compared with the control. SNP alone moderately increased TF of Cd (1.9-fold), while co-application with Cd reduced it (Cd100+SNP: 34.2%; Cd500+SNP: 5.9%). In the romaine lettuce, TF of Cd increased markedly under Cd100 (3.1-fold) but less under Cd500 (1.5-fold). SNP alone increased this parameter by 99.6%, whereas Cd+SNP treatments caused variable responses: a slight reduction at Cd100+SNP (4.5%) and a notable increase at Cd500+SNP (50%), compared to Cd100 and Cd500 alone. In the iceberg lettuce, TF of Cd showed the highest increases among varieties (4.0-fold at Cd100 and 2.7-fold at Cd500). However, compared to Cd100 and Cd500 alone, SNP co-application significantly reduced TF of Cd (Cd100+SNP: -26.3%; Cd500+SNP: -28.1%) (

Table 1).

The TAR of Cd exhibited dramatic Increases In all lettuce varieties following Cd exposure, confirming the strong uptake potential of lettuce plants. In the curly lettuce, TAR increased by 63.5-fold and 87.8-fold under Cd100 and Cd500, respectively. SNP alone slightly reduced TAR of Cd (26.3%), and its co-application caused contrasting responses, compared to Cd100 and Cd500 alone: a decline at Cd100+SNP (43.3%) and a moderate increase at Cd500+SNP (26.2%). In the romaine lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 stress sharply increased the TAR of Cd by 43.5-fold and 46.0-fold, respectively, while SNP alone decreased it (18.3%). The combination with Cd slightly increased TAR of Cd at Cd100+SNP (10.5%) and strongly at Cd500+SNP (58.4%). In the iceberg lettuce, TAR of Cd increased by 39.0-fold and 31.7-fold under Cd100 and Cd500 stress, whereas SNP alone reduced it (71.5%). Co-application with Cd showed contrasting results compared to the Cd100 and Cd500 applications and represented a decline at Cd100+SNP (52.7%) and a substantial increase at Cd500+SNP (46.1%) (

Table 1).

Applied Cd levels caused a pronounced increase in the NetAcc of Cd in all lettuce varieties, with the curly and iceberg varieties showing the most intense responses (

Table 1). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of Cd increased by 112.8-fold (Cd100) and 223.5-fold (Cd500), indicating extensive Cd accumulation. Compared to the Cd100 and Cd500 applications, the SNP application reduced these values by 48.2% (Cd100+SNP) and 15.2% (Cd500+SNP), confirming NO’s inhibitory effect on Cd deposition in shoots. In the romaine, the NetAcc of Cd values increased by Cd100 (132.1-fold) and Cd500 (257.8-fold), compared to the control, while SNP co-treatment (Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP) decreased the NetAcc (37.9% and 28.7%, respectively), compared to Cd alone, revealing partial NO-mediated mitigation. Iceberg lettuce displayed similarly dramatic increases by 85.5-fold and 179.7-fold under Cd exposure (Cd100 and Cd500, respectively), with SNP reducing the NetAcc of Cd considerably (Cd100+SNP: 59.2%; Cd500+SNP: 20.6%), compared to the Cd levels alone, suggesting that NO effectively restrained Cd accumulation even in the most sensitive genotype (

Table 1).

3.6. Effects of Cadmium and SNP on Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Metallic Ions

Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Potassium (K) and Calcium (Ca) via Roots

The Cd exposure considerably affected the uptake and translocation of essential mineral nutrients, particularly K and Ca, in all lettuce varieties (

Figure 6). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of K decreased by 9.3% and 33.6% under Cd100 and Cd500 treatments, respectively, compared with the control, indicating dose-dependent inhibition of K⁺ transport. SNP application alone slightly enhanced the NetAcc of K (13.8%). However, under Cd+SNP treatments, the NetAcc of K levels remained lower than control (Cd100+SNP: -22.3%; Cd500+SNP: -34.3%). Similarly, the romaine lettuce exhibited minor reductions in the NetAcc of K under Cd100 and Cd500 applications (11.3% and 7.1%, respectively), while SNP alone increased this parameter by 24.3%. Co-application with Cd caused a slight amelioration and restored the NetAcc of K (Cd100+SNP: -10.2%; Cd500+SNP: -3.7%). In the iceberg lettuce, the NetAcc of K decreased significantly in Cd100 and Cd500 applications by 3.1% and 38.3%, respectively, and SNP alone had a little effect (2.5%). Under the Cd500+SNP application, the NetAcc of K partially improved by 15%, compared to the Cd500 alone (

Figure 6A).

The NetAcc of Ca followed a similar trend. In the curly lettuce, Cd100 and Cd500 applications reduced the NetAcc of Ca by 4.4% and 30.0%, while SNP alone increased this parameter by 9.0%. Cd+SNP treatments led to further reductions (Cd100+SNP: -25.6%; Cd500+SNP: -34.4%). The romaine lettuce also showed notable Ca accumulation losses under Cd100 and Cd500 applications (24.8% and 23.9%, respectively), while SNP increased the NetAcc of Ca by +10.7%. Cd100+SNP treatment partially alleviated Ca accumulation by 16.5%, but Cd500+SNP still exhibited an inhibition (31.2%). In the iceberg lettuce, the NetAcc of Ca decreased by 17.5% and 42.0% under Cd100 and Cd500 exposure, respectively. SNP alone had almost no effect, but Cd500+SNP combinations slightly improved Ca accumulations by 30.6%.

Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Iron (Fe) via Roots

On the other hand, Cd exposure considerably affected the NetAcc of Fe in all lettuce varieties (

Table 2). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of Fe decreased by 23.9% (Cd100) and 37.4% (Cd500) compared to the control. SNP application alone strongly enhanced Fe accumulation (74%), and its co-application with Cd further amplified the NetAcc of Fe (Cd100+SNP: 87.8%; Cd500+SNP: 65.2%). In the romaine lettuce, NetAcc of Fe declined sharply under Cd stress (Cd100: 50.9% and Cd500: 43.9%), while SNP increased remarkably in the NetAcc of Fe (100.9%). The Cd+SNP treatments significantly enhanced the NetAcc of Fe (Cd100+SNP: 83.3%; Cd500+SNP: 39.4%) relative to the control. Similarly, the iceberg lettuce showed notable reductions in the NetAcc of Fe under Cd stress (Cd100: 25.7% and Cd500: 48.7%) but marked increases with SNP (74.5%). Combined Cd+SNP treatments reversed the Cd-induced decline (Cd100+SNP: 52.9%; Cd500+SNP: 45.1%) (

Table 2).

Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Zinc (Zn) via Roots

The NetAcc of Zn displayed variable trends under Cd stress (

Table 2). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of Zn slightly increased under Cd100 (12.9%) but declined under Cd500 (10%) compared to the control, likely reflecting concentration-dependent interference of Cd²⁺ with Zn²⁺ uptake channels. SNP alone decreased Zn (14.5%), and its combination with Cd reduced levels further (Cd100+SNP: -14.5%; Cd500+SNP: -17.2%), suggesting antagonistic interaction between NO and Zn transport. In the romaine variety, the NetAcc of Zn decreased under Cd (Cd100: 36.7% and Cd500: 13.0%), but it increased significantly under SNP (66.5%). Co-application of Cd100+SNP caused notable amelioration by 31.4%, whereas Cd500+SNP made the NetAcc of Zn worse by 29.9%, compared to Cd500 alone. In the iceberg lettuce, Cd exposure (Cd100 and Cd500) drastically reduced Zn accumulation (58.9% and 67.1%, respectively), while SNP alone decreased it modestly by 42.8%, compared to the control. Cd+SNP combinations slightly reduced the NetAcc of Zn at Cd100+SNP (18.4%), but improved the NetAcc of Zn at Cd500+SNP by 77.7%, highlighting NO’s mild compensatory influence (

Table 2).

Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Copper (Cu) via Roots

The NetAcc of Cu was also disrupted by Cd toxicity (

Table 2). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of Cu declined under Cd stress (18.2% at Cd100; 34.7% at Cd500), while this parameter tended to increase with SNP alone (6.7%). Cd+SNP combinations mitigated the NetAcc of Cu slightly (Cd100+SNP: 13.1% and Cd500+SNP: 2.9%), compared to Cd levels alone. In romaine, the NetAcc of Cd caused severe reductions in Cd stress (Cd100: 88.4% and Cd500: 83.8%), confirming a strong antagonism between Cd and Cu transport. SNP alone also decreased the NetAcc of Cu (77.3%). Similarly, Cd+SNP treatments caused a reduction in the NetAcc of Cu (Cd100+SNP: -89.4%; Cd500+SNP: -87.4%), compared to the control.

In the iceberg lettuce, Cd levels considerably reduced the NetAcc of Cu (C100: 36.5% and Cd500: 24.8%), while the effects of SNP remained close to the control. Cd100+SNP treatments improved this parameter significantly by 31.6% however, Cd500+SNP affected this parameter negatively by 9.5%, compared to Cd alone.

Net Accumulation (NetAcc) of Manganese (Mn) via Roots

The NetAcc of Mn responded distinctly in all varieties and increased at Cd100 (33.4%) but decreased at Cd500 (27.9%) in the curly lettuce, suggesting low-dose stimulation followed by high-dose inhibition (

Table 2).

SNP alone enhanced Mn (51.2%), but in Cd+SNP treatments, the NetAcc of Mn decreased significantly (Cd100+SNP: 12.4%; Cd500+SNP: 35.3%), showing limited NO protection under combined stress. In the romaine, the NetAcc of Mn declined under Cd (Cd100: 29.2% and Cd500: 38.2%), while SNP significantly increased Mn uptake (54.2%). Co-application of Cd+SNP ameliorated the NetAcc of Mn (Cd100+SNP: 35.5%; Cd500+SNP: 57.6%) compared to the Cd levels alone, demonstrating great NO-mediated improvement of Mn homeostasis. The iceberg lettuce showed a stable Mn accumulation profile, with minimal change under Cd100 (2.2%) but a notable reduction at Cd500 (45.5%). The SNP slightly increased the NetAcc of Mn (11.6%), whereas the Cd100+SNP combination further decreased it to 17.1%. The Cd500+SNP combination did not cause any significant change in this parameter.

3.7. Correlation Analyses

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant relationships among growth traits, photosynthetic pigments, oxidative stress indicators, antioxidant enzymes, and cobalt accumulation/transport indices in lettuce varieties (

Figure 7).

In curly lettuce, Cd exhibited strong negative correlations with all growth parameters, including shoot and root FWs and DWs (r = –0.70 to –0.59). Pigment contents showed strong negative Correlations with Cd (r = –0.70 to –0.90). Cd exhibited powerful positive correlations with all oxidative stress markers (H₂O₂ = +0.87, MDA = +0.67, proline = +0.85, and MP = +0.96). CAT and APX displayed a strong positive correlation (r ≈ +0.87), and shoot and root Cd concentrations were strongly correlated (r ≈ +0.75). In addition, accumulation parameters (sCd, rCd, BCF, TAR) were positively associated with each other and with TF. Especially, the NetAcc of K and (NA-K) and the NetAcc of Ca (NA-Ca) showed positive Correlations with growth traits (

Figure 7A).

In the romaine lettuce, Cd displayed strong negative correlations with shoot and root FWs and DWs (r = –0.70 to –0.80). Cd shows strong negative correlations with pigments (r = –0.70 to –0.90). Cd had robust positive correlations with these stress markers (H₂O₂ = +0.88, MDA = +0.65, proline = +0.85, MP = +0.96). Strong positive correlations exist among sCd, rCd, BCF, TF, and TAR. Cd exhibits mostly negative correlations with nutrient absorption parameters (the NetAcc of metallic ions) (

Figure 7B).

In the iceberg lettuce, Cd displayed strong negative correlations with biomass traits (shoot and root FWs and DWs) and pigment contents (Chl

a, Chl

b, Chl

a+b, Car) with ratios ranging from approximately –0.71 to –0.83 and r = –0.70 to –0.87, respectively. The Cd application had powerful positive correlations with oxidative stress indicators (H₂O₂ = +0.88, MDA = +0.70, proline = +0.88, MP = +0.96). Strong positive correlations were observed among all Cd accumulation and transport parameters (r = 0.70–0.95). In addition, the NetAcc of K and Ca (NA-K and NA-Ca) exhibit a positive correlation with growth traits (

Figure 7C).

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth and Oxidative Stress Responses

Excessive Cd interferes with vital physiological and metabolic processes such as photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and water relations, leading to stunted growth and biomass decline [

1,

2]. Cd toxicity is known to promote excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to lipid peroxidation, membrane damage, and metabolic dysfunctions in plants [

9]. The exogenous NO can mitigate most of these detrimental effects by (i) modulating oxidative metabolism, (ii) restoring ionic homeostasis, and (iii) restricting Cd mobility within plant tissues [

35,

36,

37].

The present findings show that Cd toxicity triggered oxidative stress, disrupted antioxidant enzyme activities, inhibited nutrient uptake, and promoted Cd accumulation and translocation, with the severity of responses varying among lettuce varieties (the curly, romaine, and iceberg). Cd exposure reduced both shoot and root FWs and DWs in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 1), indicating that the metal interfered with cellular metabolism, water relations, and carbon assimilation. Biomass inhibition was most severe in the curly and romaine lettuce, while the iceberg maintained relatively higher growth performance. These findings are consistent with earlier reports in lettuce and other leafy vegetables, where Cd exposure reduced shoot biomass by more than 50% due to chlorophyll degradation and impaired nutrient translocation [

17,

18].

The reductions in biomass were closely linked to elevated oxidative stress markers (H₂O₂, MDA, and MP percentage), confirming that Cd-induced ROS generation underlies growth suppression [

2]. SNP application alleviated these effects, markedly improving biomass accumulation by restoring redox balance and stabilizing membranes. The observed recovery of shoot FW and root DW under Cd+SNP treatments reflects NO-mediated enhancement of photosynthetic performance and osmotic regulation, similar to observations in wheat roots [

35,

36,

38].

Among the varieties, curly lettuce exhibited a relatively lower biomass reduction, indicating stronger tolerance to Cd toxicity, while the romaine and iceberg lettuce showed greater growth inhibition (

Figure 1). Such varietal differences are often linked to genotypic variations in Cd uptake efficiency, antioxidant enzyme activities, and the ability to maintain photosynthetic integrity [

12,

39]. The pronounced declines in shoot FW (28% to 71%) and root FW (12% to 57%) suggest that Cd toxicity directly affected meristematic tissues, leading to reduced cell division and elongation (

Figure 1). Similar inhibitory effects of Cd on root elongation have been attributed to cell wall rigidity and oxidative damage at the root tips [

4].

Cd is known to interfere with chlorophyll biosynthesis, impair carbon assimilation, and increase the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H₂O₂ and superoxide radicals, which collectively limit plant growth and biomass production [

2]. Excessive ROS accumulation damages membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to cell death and growth retardation [

40]. In this study, the strong decline in root biomass indicates that Cd toxicity primarily affected root metabolism, decreasing water absorption and nutrient transport to shoots. The romaine and iceberg lettuce varieties exhibited greater sensitivity to Cd stress than the curly variety (

Figure 1C and 1D), likely due to their lower antioxidant capacity and weaker ionic regulation mechanisms. Such varietal differences have been previously reported in lettuce and other leafy vegetables exposed to heavy metals [

18,

39].

The Cd was strongly and negatively correlated with all pigment variables at variety-specific intensities (

Figure 7). Both the iceberg and romaine varieties showed the steepest pigment declines, while the curly variety maintained its pigments relatively well under Cd stress (

Figure 2). This suggests that Cd stress disrupts chlorophyll synthesis and accelerates pigment degradation most severely in the iceberg, likely due to greater ROS accumulation and membrane damage [

41].

However, SNP application significantly mitigated these growth reductions in all varieties, reflecting the protective role of NO in alleviating heavy metal stress. Exogenous NO donors are known to enhance biomass accumulation by improving photosynthetic carbon assimilation, promoting nutrient uptake, and reducing oxidative injury [

42]. In this study, SNP co-treatment notably restored shoot FW by up to 84.6% in the romaine lettuce and root FW by more than 60% in the iceberg lettuce compared with Cd-only treatments, indicating that NO improved growth through ROS detoxification and membrane stabilization (

Figure 4B). The observed enhancement in shoot and root DW under Cd+SNP treatments supports the hypothesis that NO contributes to maintaining turgor, protein synthesis, and carbohydrate metabolism under Cd stress [

11].

The alleviatory effect of NO could also involve modulation of hormonal signaling and Cd sequestration. NO has been reported to interact with auxin and cytokinin pathways, promoting root architecture and nutrient acquisition under stress conditions [

13]. Moreover, NO can induce the synthesis of phytochelatins and metallothioneins that chelate Cd²⁺ in the cytosol, thus lowering its bioavailability and toxicity [

40]. Consequently, the improved biomass observed in Cd+SNP treatments in the present study can be attributed to both direct antioxidant activity and indirect regulation of metal detoxification mechanisms.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that NO supplementation effectively counteracts Cd-induced growth inhibition by preserving cellular redox homeostasis, enhancing root functionality, and promoting physiological resilience. The magnitude of SNP-induced improvement followed the order “Romaine” > “Iceberg” > “Curly”, indicating that genotypic differences in NO sensitivity and Cd uptake capacity play crucial roles in determining the extent of mitigation (

Figure 1C and 1D).

4.2. Enzymatic Antioxidant Defense

The Cd exposure triggered significant alterations in antioxidant enzyme activities in all lettuce varieties, reflecting the plant’s physiological attempt to counteract oxidative stress. The enzymatic defense system, particularly CAT and APX, plays a vital role in scavenging H₂O₂, one of the major reactive oxygen species generated under Cd stress. The sharp increase in CAT activity observed under Cd100 and Cd500 treatments in all varieties indicates an enhanced detoxification response to excessive ROS (

Figure 3A). This pattern is consistent with previous studies showing that Cd stimulates H₂O₂ production, which subsequently induces CAT synthesis as part of the primary antioxidative defense [

2,

9].

In the curly and iceberg lettuce, CAT activity rose by over 100% compared with the control, demonstrating a strong enzymatic response to oxidative stress (

Figure 5A). Conversely, the romaine lettuce exhibited a similar increase in CAT under Cd exposure but with greater variability at higher Cd concentrations, suggesting potential enzyme inactivation due to prolonged oxidative load. The decline in APX activity under Cd stress, particularly in curly and iceberg, supports this notion, as APX is highly sensitive to redox imbalance and may be inhibited by Cd binding to its active site [

43]. However, the transient increase in APX activity observed in the romaine at Cd100 suggests an early defense activation, which likely diminished under prolonged or higher Cd exposure.

The application of SNP significantly modulated these antioxidant responses, highlighting NO’s regulatory role in maintaining redox homeostasis. SNP alone caused a mild reduction in CAT and APX activities, reflecting a lowered oxidative demand in the absence of Cd stress. However, under Cd+SNP treatments, CAT activity remained elevated but more stable than in Cd-only plants, while APX activity showed a significant recovery, particularly in the curly and iceberg varieties (

Figure 5A). This indicates that NO fine-tuned the antioxidant system, preventing excessive activation while enhancing ROS scavenging efficiency. Similar NO-mediated modulation of antioxidant enzymes has been reported in

Brassica napus [

35] and

Oryza sativa [

13], where NO not only acts as a direct ROS scavenger but also regulates antioxidant enzyme expression through signaling pathways.

The dual role of NO as both a signaling and protective molecule can explain the differential enzyme responses among varieties. In curly lettuce, NO appeared to balance CAT hyperactivity and restore APX function, thereby achieving effective H₂O₂ detoxification. In the romaine, NO improved CAT activity at higher Cd concentrations, but APX was not fully restored, indicating partial protection (

Figure 5B). The iceberg lettuce displayed a dose-dependent enhancement of APX under Cd+SNP, suggesting stronger activation of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle under NO regulation.

These results collectively suggest that SNP-mediated NO signaling mitigates Cd-induced oxidative stress by optimizing the antioxidant machinery rather than simply amplifying enzyme activities. By maintaining the dynamic equilibrium between ROS production and scavenging, NO ensures cellular redox stability, protecting biomolecules from oxidative injury. The extent of this enzymatic regulation followed the order “Iceberg” > “Curly” > “Romaine”, reflecting the greater NO sensitivity and adaptive antioxidant capacity of the iceberg lettuce under Cd stress (

Figure 5).

4.3. Ion and Nutrient Homeostasis

Cd stress significantly disrupted the ionic equilibrium and nutrient accumulation patterns in lettuce, indicating its strong interference with essential element uptake and translocation. The reduction in both macronutrient (K⁺ and Ca²⁺) and micronutrient (Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn) accumulation levels under Cd exposure reflects the element’s ability to compete for common transport sites and impair membrane transport systems (

Table 2 and

Figure 6. Such ionic disturbances are characteristic of Cd toxicity and are closely associated with reduced growth and metabolic performance [

1,

4]. Under Cd stress, the NetAcc of both K and Ca markedly declined in all lettuce varieties (

Figure 6). In the curly lettuce, the NetAcc of K decreased (up to 34%) and Ca (up to 30%), while the romaine and iceberg varieties showed even stronger reductions, up to 38% in K and 42% in Ca. These findings align with previous studies indicating that Cd competes with essential cations for uptake channels such as Ca²⁺-permeable channels and disrupts the function of H⁺-ATPases and Ca²⁺-ATPases at the plasma membrane. The resulting ionic imbalance could affect osmotic adjustment, stomatal regulation, and photosynthetic efficiency [

5].

The deceleration of the NetAcc of K in the iceberg variety (up to 15%) and Ca (up to 30%) under Cd+SNP treatments suggests that NO improved ion transport and membrane integrity (

Figure 6). NO is known to activate plasma membrane H⁺-ATPase activity, thereby maintaining electrochemical gradients that facilitate selective ion uptake [

14]. Moreover, NO may regulate Ca²⁺ signaling by promoting the synthesis of calcium-binding proteins and enhancing cytosolic Ca²⁺ buffering, preventing Cd-induced Ca²⁺ leakage. These mechanisms collectively can explain the improved ion homeostasis observed under SNP co-treatments [

7].

On the other hand, Cd stress also interfered with micronutrient accumulation, reflecting its antagonistic interactions with essential metals. the NetAcc of Fe and Zn declined sharply in lettuce (by up to 51% in the romaine and 67% in the iceberg, respectively), while the curly lettuce exhibited a moderate decrease in the NetAcc of Fe and slight fluctuations in the NetAcc of Zn (

Table 2). Such responses are typical of Cd–Fe and Cd–Zn competition for transporters like IRT1 and ZIP family proteins, which have limited metal selectivity. Cd may also impair Fe translocation to shoots by disturbing ferric chelate reductase activity and Fe–S cluster formation [

44].

Interestingly, the NetAcc of Cu and Mn showed more variable responses (

Table 2). The NetAcc of Cu decreased in all lettuce varieties (up to 34.7% in the curly, 88.4% in the romaine, and 36.5% in the iceberg), indicating that Cd blocked Cu transport or replaced Cu in metalloproteins such as plastocyanin. In contrast, Mn accumulation increased significantly under Cd100 exposure in curly (33.4%), suggesting a compensatory mechanism to stabilize redox metabolism [

45]. However, higher Cd concentrations (Cd500) caused Mn depletion in all varieties, possibly highlighting the progressive collapse of ionic balance under prolonged stress.

SNP supplementation effectively mitigated these disruptions by enhancing the NetAcc of Fe and Mn while moderating the NetAcc of Zn and Cu fluctuations. In curly lettuce, Fe accumulation increased with Cd100+SNP by 87.8% compared with Cd100 alone, demonstrating NO’s capacity to restore Fe homeostasis. Similarly, Mn accumulation improved in romaine (35.5 to 57.6% with Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP, respectively), confirming NO’s positive influence on divalent metal uptake systems (

Table 2). The ability of NO to upregulate Fe and Mn transporters (e.g., NRAMPs) and to stabilize membrane permeability likely contributed to these effects [

11,

46]. Conversely, the limited recovery of Zn and Cu indicates that NO’s regulation is selective and may prioritize redox-active metals essential for antioxidant enzyme function.

4.4. Integrated Ionic Regulation under NO

The overall pattern of ion homeostasis restoration suggests that SNP-derived NO enhanced membrane integrity, preserved transport selectivity, and prevented excessive Cd interference. NO may interact with signaling cascades involving Ca²-dependent protein kinases and reactive nitrogen species, thereby fine-tuning ion transport activity [

12]. Moreover, by mitigating oxidative membrane damage, NO indirectly improved nutrient uptake efficiency and root absorption capacity (

Figure 1D and 4B).

Our findings indicated that Cd-induced ionic imbalance was significantly alleviated by SNP application through NO-mediated regulation of membrane transport, ion selectivity, and redox stabilization. The Cd accumulations in the shoots and roots were seen to decrease in the Cd100+SNP and Cd500+SNP applications (up to 66.0% in shoots and 52.9% in roots) (

Table 1). Moreover, Cd100+SNP exposure caused decreases in accumulations of Zn (24.3% in the curly and 18.4% in the iceberg) and Mn (34.3% in the curly and 18.8% in the iceberg) (

Table 2). These results emphasize the central role of NO in preserving both macro- and microelement homeostasis under heavy metal stress, which directly contributes to improved growth and physiological stability in lettuce [

11].

4.5. Cd Uptake, Translocation, and Detoxification Mechanisms

The dose-dependent Cd accumulation and partitioning within plant tissues are crucial indicators of heavy-metal tolerance. In the present study, Cd exposure markedly increased Cd concentration, translocation, and accumulation in all lettuce varieties, as reflected by the sharp rises in the TF, TAR, NetAcc, and BCF values (

Table 1). However, SNP co-application significantly modulated these parameters, demonstrating the regulatory influence of NO on Cd transport and detoxification pathways.

Correlation patterns among sCd, rCd, BCF, TF, and TAR revealed that all varieties possess consistent internal distribution mechanisms for Cd (

Figure 7). The iceberg variety displayed the strongest internal coherence among these indices, suggesting highly efficient metal uptake and accumulation, which likely contributes to its heightened sensitivity (

Figure 7C). The curly variety showed slightly weaker correlations among metal indices, which may reflect limited metal uptake or improved internal regulation, contributing to its greater tolerance (

Figure 7A). TF of Cd (TF) was generally lower in the iceberg, implying greater retention of Cd in roots, possibly as a partial defense strategy to restrict its movement toward photosynthetically active tissues (

Table 1 and

Figure 7C).

The TF values increased sharply under Cd stress (Cd100), reaching 3.0-fold in the curly lettuce, 3.1-fold in the romaine, and 4.0-fold in the iceberg lettuce. This suggests that Cd was efficiently mobilized from roots to shoots through the xylem stream. However, excessive Cd transport to aerial parts enhances toxicity by disrupting photosynthetic metabolism and oxidative balance. Cd100+SNP treatment markedly reduced TF values by 26.3-34.2% compared to Cd100 alone, indicating that NO effectively restricted Cd translocation (

Table 1). This suppression likely occurred through enhanced Cd retention in roots or inhibition of xylem loading, consistent with reports that NO reduces long-distance Cd transport by strengthening apoplastic barriers and modulating transporter expression [

5,

46,

47].

The TAR and NetAcc values of Cd also exhibited substantial increases under Cd exposure, reflecting accelerated Cd absorption and storage. The curly lettuce recorded the highest TAR (87.8-fold) and the NetAcc (223.5-fold) at Cd500 application, followed by the iceberg and romaine varieties. SNP application, however, decreased the NetAcc significantly by up to 48.2% in the curly and 37.9% in the romaine, suggesting that NO either inhibited Cd uptake or enhanced its sequestration in root tissues (

Table 1). Similar reductions in Cd accumulation after NO treatment have been documented in

Oryza sativa [

13] and

Brassica napus [

35], where NO-induced thiol-rich peptides bind Cd²⁺ in the cytosol, preventing further translocation to shoots.

Both shoot and root BCF decreased significantly under Cd stress, implying that Cd uptake efficiency declined due to transporter inhibition and membrane injury. The observed decreases in shoot BCF (up to 95.6%) and root BCF (up to 97.8%) in all varieties are consistent with Cd-induced downregulation of metal transporters and cellular damage [

44]. SNP application further reduced both BCF indices, particularly in the curly and iceberg lettuce, confirming NO’s inhibitory effect on Cd absorption and mobility (

Table 1). This reduction may be associated with NO-mediated reinforcement of cell wall binding sites through cross-linking of pectic polysaccharides, limiting Cd entry into the symplast [

38]. Similarly, a decrease in the BCF of safflower with increasing Cd concentrations was reported [

34].

The modulation of Cd uptake and transport by NO involves both physiological and molecular mechanisms. NO has been reported to induce the expression of phytochelatin synthase (PCS) and metallothionein genes, facilitating Cd chelation and vacuolar sequestration [

12,

48]. Moreover, NO interacts with glutathione metabolism, increasing the pool of reduced thiols (GSH) that bind Cd and minimize cytotoxicity. These mechanisms together prevent Cd from reaching the photosynthetic tissues and alleviate oxidative stress.

The varietal differential responses in Cd accumulation indicate genotype-dependent control of NO-mediated detoxification. Curly lettuce displayed the strongest NO responsiveness, as evidenced by large reductions in the TF, TAR, and NetAcc, implying efficient Cd retention in roots and limited translocation. The romaine variety showed moderate NO-induced regulation, while the iceberg variety exhibited partial recovery, suggesting that its barrier mechanisms were less effective. Such varietal differences may reflect variations in root apoplastic structure, vacuolar sequestration capacity, or NO signaling sensitivity [

12].

The collective results confirm that SNP-derived NO alleviates Cd toxicity by integrating three primary mechanisms. Firstly, inhibiting Cd uptake by downregulating or blocking root Cd transporters, thus reducing overall Cd efflux. Secondly, providing strengthening of root apoplastic barriers and modulation of xylem load by restricting Cd translocation, and lastly increasing Cd sequestration and enabling phytochelatin and metallothionein-mediated binding and activation of vacuolar compartmentalization.

Through these coordinated processes, NO effectively limits Cd mobility, prevents systemic toxicity, and protects photosynthetically active tissues. This outcome is in accordance with reports in mung bean, rice, and lettuce, indicating that NO acts as a molecular switch in Cd detoxification networks [

12,

13,

19].

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that nitric oxide, supplied via sodium nitroprusside, plays a pivotal role in alleviating cadmium-induced stress in lettuce by integrating redox regulation, ion homeostasis, and metal detoxification mechanisms. Cadmium exposure disrupted antioxidant enzyme coordination, mineral nutrient balance, and membrane integrity, leading to pronounced oxidative damage and growth inhibition. Exogenous NO application effectively restored antioxidant balance, particularly through re-establishing CAT–APX coordination, reduced oxidative stress markers, and stabilized cellular membranes. Furthermore, NO markedly restricted cadmium uptake and root-to-shoot translocation by enhancing root sequestration and vacuolar detoxification, thereby limiting Cd mobility within the plant. The improvement of essential ion homeostasis, especially K⁺, Ca²⁺, Fe²⁺, and Mn²⁺, highlights the role of NO in maintaining selective ion transport under metal stress conditions. Notably, the magnitude of NO-mediated protection was genotype-dependent, with curly lettuce exhibiting the highest tolerance, followed by iceberg and romaine varieties. Collectively, these findings identify nitric oxide as a central signaling regulator that enhances physiological resilience and reduces cadmium accumulation in lettuce, offering a promising strategy for mitigating heavy metal stress in leafy vegetables and improving food safety.

Funding information

This study did not receive any financial support.

CRediT Authorship contribution statement

Samet Halil: Writing – original & draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Software, Visualization, Resources; Çıkılı Yakup: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors state that they have no financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have influenced the research presented in this paper.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the manuscript preparation process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used OpenAI ChatGPT (GPT-5) for language refinement and improvement of textual clarity. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

References

- Benavides, M. P.; Gallego, S. M.; Tomaro, M.L. Cadmium toxicity in plants. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17(1), 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48(12), 909–930. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, J.; Chatterjee, C. Phytotoxicity of cobalt, chromium, and copper in cauliflower. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 109(1), 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Martinka, M.; Vaculík, M.; White, P.J. Root responses to cadmium in the rhizosphere: A review. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, X.; Qiu, G.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Guo, B. Inhibition roles of calcium in cadmium uptake and translocation in rice: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(14), 11587. [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22(1), 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek, M.; Floryszak-Wieczorek, J.; Gwóźdź, E. A. The message of nitric oxide in cadmium-challenged plants. Plant Sci. 2011, 181(5), 612-620. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Neill, S.J. Nitric oxide: Its generation and interactions with other reactive signaling compounds. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42(3), 782–794. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Inafuku, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M.; Oku, H. Nitric oxide regulates plant growth, physiology, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis to confer salt tolerance in the mangrove species, Kandelia obovata. Antioxidants 2021, 10(4), 611. [CrossRef]

- Grün, S.; Lindermayr, C.; Sell, S.; Durner, J. Nitric oxide and gene regulation in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57(3), 507-516. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Soares, C.; Sousa, B.; Martins, M.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Bali, A.S.; Asgher, M.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thukral, A.K.; Fidalgo, F.; Zheng, B. Nitric oxide-mediated regulation of oxidative stress in plants under metal stress: a review on molecular and biochemical aspects. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 168(2), 318-344. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N. I.; Yun, B.W. Nitric oxide acts as a key signaling molecule in plant development under stressful conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(5), 4782. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; An, L.; Lu, H.; Zhu, C. Exogenous nitric oxide enhances cadmium tolerance of rice by regulating antioxidative capacity. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 68, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, C. Endogenous nitric oxide mediates alleviation of cadmium toxicity induced by calcium in rice seedlings. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24(5), 940-948. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, R.M.; Dhakar, M.K.; Kumar, M. Exogenous nitric oxide enhances cadmium tolerance and uptake in Ricinus communis L. through improved photosynthesis and antioxidant defense. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2025, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Moon, Y.; Tou, J.C.; Mou, B.; Waterland, N.L. Nutritional value, bioactive compounds, and health benefits of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 49, 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Loi, N.N.; Sanzharova, N.I.; Shchagina, N.I.; Mironova, M.P. The effect of cadmium toxicity on the development of lettuce plants on contaminated sod-podzolic soil. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2018, 44(1), 49-52. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.; Santos, C.; Pinho, S.; Oliveira, H.; Pedrosa, T.; Dias, M.C. Cadmium-induced cyto-and genotoxicity are organ-dependent in lettuce. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25(7), 1423-1434. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sun, G.;Tan, H.; Lin, L.; Li, H.; Liao, M.; Wang, Z.; Lv, X.; Liang, D.; Xia, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Xiong, B.; Zheng, Y.; He, Z.; Tu, L. Cadmium-accumulator straw application alleviates cadmium stress of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) by promoting photosynthetic activity and antioxidative enzyme activities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25(30), 30671-30679. [CrossRef]

- Zorrig, W.; Cornu, J.Y.; Maisonneuve, B.; Rouached, A.; Sarrobert, C.; Shahzad, Z.; Abdelly, C.; Davidian, J.; Berthomieu, P. Genetic analysis of cadmium accumulation in lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019. 136, 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Altas, S.; Uzal, O. Mitigation of negative impacts of cadmium stress on physiological parameters of curly lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. Crispa) by proline treatments. J. Elem. 2022, 27(2), 351-365. [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. California Agricultural Experiment Station. 1950, Circ. 347, 1–32.

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350-382. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Dai, Q.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z. Flooding-induced membrane damage, lipid oxidation, and activated oxygen generation in corn leaves. Plant Soil 1996, 179, 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; De Long, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604-611. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.P.; Choudhuri, M.A. Implications of water stress-induced changes in the levels of endogenous ascorbic acid and hydrogen peroxide in Vigna seedlings. Physiol. Plant 1983, 58(2), 166-170. [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. 1973. Rapid Determination of Free Proline for Water-Stress Studies. Plant Soil. 1973, 39, 205-207. [CrossRef]

- Shigeoka, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Tamoi, M.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takeda, T.; Yabuta, Y.; Yoshimura, K. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53(372), 1305-1319. [CrossRef]

- Chance, B.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 1955, 2, 764-775. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867-880. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.O. High-temperature oxidation: dry ashing. 1998, p. 66-69. In Kalra, P.Y. (ed.) Handbook of reference methods for plant analysis. Taylor and Francis/CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

- Cikili, Y.; Samet, H.; Dursun, S. Cadmium toxicity and its effects on growth and metal nutrient ion accumulation in Solanaceae plants. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 576-587. [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Liu, C.; Cai, Q.; Liu, Q.; Hou, C. Cadmium accumulation and tolerance of two safflower cultivars in relation to photosynthesis and antioxidative enzymes. B. Environ. Contam. Tox. 2010, 85, 256-263. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, L.; Ehsanzadeh, P. Effects of Cd on photosynthesis and growth of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) genotypes. Photosynthetica 2015, 53(4), 506-518. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.T.; Kao, C.H. Cadmium toxicity is reduced by nitric oxide in rice leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 2004, 42, 227–238. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Kaur, G.; Arora, K.; Kohli, R.K. Nitric oxide (as sodium nitroprusside) supplementation ameliorates Cd toxicity in hydroponically grown wheat roots. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63(1-3), 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yin, H. X.; Liu, X. J.; Yuan, T.; Mi, Q.; Yang, L. L.; Xie, Z.X.; Wang, W. Y. Nitric oxide alleviates Fe deficiency-induced stress in Solanum nigrum. Biol. Plant. 2009, 53(4), 784-788. [CrossRef]

- Besson-Bard, A.; Gravot, A.; Richaud, P.; Auroy, P.; Duc, C.; Gaymard, F.; Taconnat, L.; Renou, J.; Pugin, A.; Wendehenne, D. Nitric oxide contributes to cadmium toxicity in Arabidopsis by promoting cadmium accumulation in roots and by up-regulating genes related to iron uptake. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149(3), 1302-1315. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Cui, H.; Fan, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, J. Soil and foliar applications of silicon and selenium effects on cadmium accumulation and plant growth by modulation of antioxidant system and Cd translocation: Comparison of soft vs. durum wheat varieties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123546. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Serrano, M.; Romero-Puertas, M.C.; Pazmino, D.M.; Testillano, P.S.; Risueño, M.C.; Del Río, L.A.; Sandalio, L.M. Cellular response of pea plants to cadmium toxicity: cross-talk between reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, and calcium. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150(1), 229-243. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, M.; Guo, L.; Huang, L. Effect of cadmium on photosynthetic pigments, lipid peroxidation, antioxidants, and artemisinin in hydroponically grown Artemisia annua. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24(8), 1511-1518. [CrossRef]

- Esringu, A.; Aksakal, O.; Tabay, D.; Kara, A. A. Effects of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) pretreatment on UV-B stress tolerance in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23(1), 589-597. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dubey, R.S. Lead toxicity induces lipid peroxidation and alters antioxidant enzymes in growing rice plants. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 645–655. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S. Metal ligands in plant metal homeostasis and detoxification. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42(10), 2909–2923. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.N.; An, H.; Yang, Y.J.; Liang, Y.; Shao, G.S. Effects of Mn-Cd antagonistic interaction on Cd accumulation and major agronomic traits in rice genotypes by different Mn forms. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 82(2), 317-331. [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Nie, W.; Yan, Y.; Gao, Z.; Shi, Q. Unravelling cadmium toxicity and nitric oxide-induced tolerance in Cucumis sativus: insight into regulatory mechanisms using proteomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 336, 202-213. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Á.; Williams, L. E. Transition metal transporters in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54(393), 2601-2613. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Serrano, M.; Romero-Puertas, M. C.; Pazmino, D. M.; Testillano, P. S.; Risueño, M.C.; Del Río, L.A.; Sandalio, L. M. Cellular response of pea plants to cadmium toxicity: cross talk between reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, and calcium. Plant physiology, 2009, 150(1), 229-243. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on shoot fresh weight (A) and dry weight (B); root fresh weight (C) and dry weight (D) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 1.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on shoot fresh weight (A) and dry weight (B); root fresh weight (C) and dry weight (D) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 2.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), chlorophyll a+b (C), and carotenoid (D) contents of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 2.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), chlorophyll a+b (C), and carotenoid (D) contents of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 3.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on H2O2 (A) and MDA (B) contents of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 3.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on H2O2 (A) and MDA (B) contents of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 4.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on proline accumulation (A) and membrane permeability (B) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 4.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on proline accumulation (A) and membrane permeability (B) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 5.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on CAT (A) and APX (B) activity of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 5.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on CAT (A) and APX (B) activity of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 6.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on NetAcc of potassium (A) and calcium (B) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 6.

The effects of the Cd and SNP on NetAcc of potassium (A) and calcium (B) of lettuce varieties (Values are the mean of three replicates, means ± SE, n=3. Different letters in bars indicate significant differences according to the DMRT, p <0.05).

Figure 7.

The correlation matrix illustrates the relationships among parameters measured in the roots and shoots of the curly (A), romaine (B), and iceberg (C) lettuce varieties. In the matrix, the circles’ color and size reflect the strength and direction of the correlations: blue circles indicate positive correlations, while red circles denote negative correlations. Larger circles correspond to stronger correlation coefficients. (Abbreviations: Cd, cadmium; s, shoot; r, root; Chl, chlorophyll; Car, carotenoids; MP, membrane permeability; BCF, bio concentration factor; TF, translocation factor; TAR, total accumulation rate; NA, net ion accumulation via roots; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MDA, lipid peroxidation; Pro, proline; CAT, catalase; APX, ascorbate peroxidase).

Figure 7.

The correlation matrix illustrates the relationships among parameters measured in the roots and shoots of the curly (A), romaine (B), and iceberg (C) lettuce varieties. In the matrix, the circles’ color and size reflect the strength and direction of the correlations: blue circles indicate positive correlations, while red circles denote negative correlations. Larger circles correspond to stronger correlation coefficients. (Abbreviations: Cd, cadmium; s, shoot; r, root; Chl, chlorophyll; Car, carotenoids; MP, membrane permeability; BCF, bio concentration factor; TF, translocation factor; TAR, total accumulation rate; NA, net ion accumulation via roots; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MDA, lipid peroxidation; Pro, proline; CAT, catalase; APX, ascorbate peroxidase).

Table 1.

The effects of Cd and SNP on concentrations and accumulation of cadmium in the curly, romaine, and iceberg lettuce varieties.

Table 1.

The effects of Cd and SNP on concentrations and accumulation of cadmium in the curly, romaine, and iceberg lettuce varieties.

| Treatments |

Cd concentration (mg kg-1) |

BCF of Cd |

TF of Cd

% |

TAR of Cd (μg g-1 DW day-1) |

| Shoot |

Root |

Shoot |

Root |

|

Curly lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa) |

| Control |

0.81±0.16 e |

5.60±0.21 e |

80.9±15.7 b |

561.5±21.1 a |

14.6±3.26 c |

0.22±0.08 |

| Cd100

|

168.03±2.52 c |

377.10±4.49 c |

15.0±0.23 c |

33.6±0.40 c |

44.6±0.71 a |

13.98±2.67 |

| Cd500

|

332.52±39.20 a |

1162.2±58.50 a |

6.6±0.14 c |

20.7±1.04 c |

31.9±1.12 b |

19.32±4.82 |

| SNP |

1.23±0.05 e |

4.40±0.14 e |

122.73±4.4 a |

438.0±13.7 b |

28.1±1.71 b |

0.16±0.02 |

| SNP+Cd100

|

75.13±0.49 d |

256.80±10.40 d |