Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seedling Treatment

2.2. Selection of Cd Levels

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Plant Sample Collection and Measurements

2.5. Growth Parameter Measurements

2.6. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

2.7. MDA Determination

2.8. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.9. Determination of Oxidative Substances

2.10. Determination of Cd and Ca Content in Plants

2.11. Data Processing

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Effects of Different Calcium Levels on Growth Characteristics of Maize Seedlings Under Cadmium Stress

3.2. Effects of Different Calcium Levels on Photosynthetic Pigment Content in Maize Seedlings Under Cd Stress

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) |

Root Length (cm) |

Shoot Dry Weight (g) |

Root Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 45.27±0.23a | 31.98±0.23c | 15.46±0.26b | 3.57±0.13a |

| K-1 | 43.55±0.15b | 30.75±0.36b | 14.23±0.32c | 3.39±0.19a |

| K-2 | 45.19±0.81a | 33.72±0.09b | 16.03±0.38b | 3.47±0.09a |

| K-3 | 46.17±0.20a | 35.37±0.13a | 17.89±0.31a | 3.70±0.11a |

3.3. Effects of Different Calcium Levels on MDA Content in Maize Under Cd Stress

3.4. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.5. Cd and Ca Accumulation in Plant Tissues Under Varying Calcium Levels

3.6. Correlation Matrix

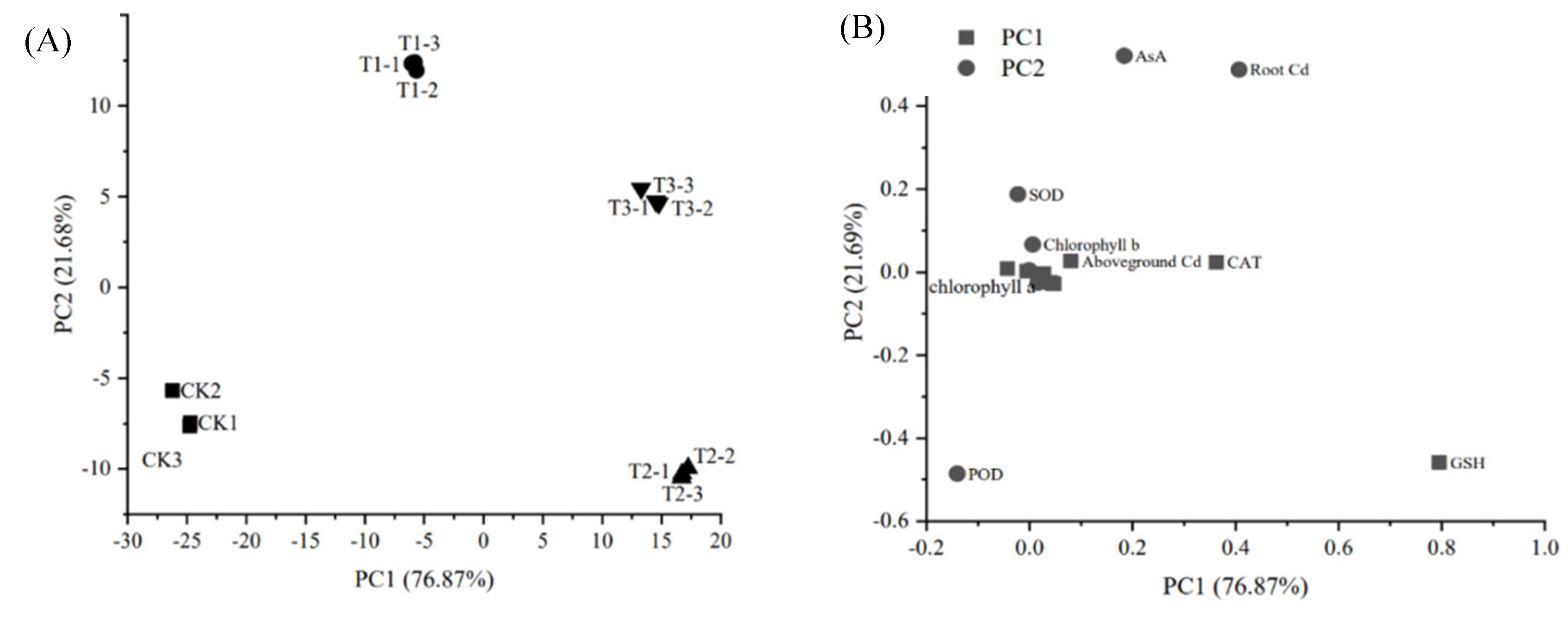

3.7. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Li, Y.N.; Tan, M.T.; Wu, H.F.; Zhang, A.Y.; Xu, J.S.; Meng, Z.J. Transfer of Cd along the food chain: The susceptibility of Hyphantria cunea larvae to Beauveria bassiana under Cd stress. Journal of HazardousMaterials. 2023, 453, 131420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Naz, S.; Kumar, R.; Sardar, H.; Nawaz, M.A.; Kumar, A. Unraveling the mechanisms of cadmium toxicity in horticultural plants: implications for plant health. South African Journal Of Botany. 2023, 12, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasafi, T.E.; Oukarroum, A.; Haddioui, A.; Song, H.; Rinklebe, J.; Nanthi, B. Cadmium stress in plants: a critical review of the effects, mechanisms, and tolerance strategies. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 2022, 52, 675–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.K.; Zhu, L.N.; Yang, Q.Y. Effects of Silicon-Calcium-Magnesium Fertilizer and Modified Humic Acid on Soil Cadmium Chemical Fractions and Accumulation in Wheat. Journal of Ecology and Rural Environment. 2021, 37, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Kariman, K. Physiological and antioxidative responses of medicinal plants exposed to heavy metals stress. Plant Gene. 2017, 11, 247–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.X.; Wu, X.; Cao, Y.; Yan, X.Y.; Li, L. Research Progress on Effect and Mechanism of Exogenous Calcium Induced Plant Response to Cadmium Stress. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jiang, W.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Liao, J.; Liang, X.L.; Wang, H.J. Physiological response and cadmium accumulation and translocation characteristics of Aster subulatus Michx. to cadmium stress. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2022, 35, 2860–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zeng, Q.R.; Deng, X. Effect of Combined Application of Calcium Magnesium Phosphate-potassium Carbonate-lime on Cadmium Accumulation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chinese Journal of Soil Science. 2024, 55, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Mohamed, H.I. Alleviation of cadmium toxicity in Pisum sativum L. seedlings by calcium chloride. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2013, 41, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z., Afzal, S., Danish, M., Abbasi, G.H., Bukhari, S.A.H., Khan, M.I., 2020. Role of nitric oxide and calcium signaling in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress: Biochemical and Molecular Perspectives 2020, 563–581. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X. 2019. Toxicity of cadmium on roots of different genotypes of rice and regulation of calcium [D]. Chengdu: Sichuan Agricultural University.

- Wang, F.; Li, Y.S.; Wang, H.N.; Peng, Y.L.; Fang, Y.F.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.Z. Effect of calcium on growth and physiological characteristics of maize seedling under lead stress. Shuitu Baochi Xuebao (Journal of Soil and Water Conservation) 2016, 30, 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Meng, H.L.; Wang, T.T.; Tang, Y.H. Effects of Bacterial fertilizer on the Growth and Absorption of Cadmium and Lead in Maize. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2024, 53, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Parveen, A.; Khan, S.; Hussain, I.; Wang, X.K.; Alshaya, H. Silicon Fertigation Regimes Attenuates Cadmium Toxicity and Phytoremediation Potential in Two Maize (Zea mays L.) Cultivars by Minimizing Its Uptake and Oxidative Stress. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B. Chemistry and biochemistry of plant pigments. London: Academic Press. 1976, 38-165.

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.S.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, S.J. Experimental Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry [M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press. 2000, 167-169.

- Chen, J.X.; Wang, X.F. . Plant Physiology Experiment Guidance [M]. Guangzhou: South China University of Technology Press. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nino, H.; Shah, W. Vitamins In: Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry. Tietz, NW. WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

- Lamia, S.; Muhammad, H.; Yoshiyuki, M. Role of calcium signaling in cadmium stress mitigation by indol-3-acetic acid and gibberellin in chickpea seedlings. Environmental Science & Pollution Research. [CrossRef]

- Shumayla, T.S.; Sharma, Y. Expression of TaNCL2—a ameliorates cadmium toxicity by increasing calcium and enzymatic antioxidants activities in Arabidopsis. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, M.H.; Yi, L.T. Effects of exogenous calcium on growth and physiological characteristics of poplars under cadmium stress. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, (in Chinese). 2024, 19, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zheng, W.Y.; Hou, L.; Liu, C.T.; bHe, C.Z.; Chen, Z.X. Study on Physiological Response and Tolerance of Populus yunnanensis Seedlings to Cadmium and Zinc Stress. Journal of southwest foredtry university, 2024, 44, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Sangwan, R.S.; Mishra, S.; Jadaun, J.S.; Sabir, F.; Sangwan, N.S. Effect of cadmium stress on inductive enzymatic and nonenzymatic responses of ROS and sugar metabolism in multiple shoot cultures of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera Dunal). Protoplasma 2014, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Liu, H.; Nie, Z.; Gao, W.; Li, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, P. AsA-GSH Cycle and Antioxidant Enzymes Play Important Roles in Cd Tolerance of Wheat. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2018, 101, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, F.; Xu, X.X.; Qi, X.; Zhang, S. Effect of Foliar Spraying Calcium Oxide Nanoparticles on Cadmium Accumulation and Physiological Response in Coriander and Spinach under Cadmium Stress. Journal of Agro-Environment Science. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Long, C.Y. Release effects of exogenous SA,GSH,Ca and CA on Stachys lanata under Cd stress, Sichuan Agricultural University, 2019. 6.

- Mazhar, M.W.; Ishtiaq, M.; Maqbool, M.; Ajaib, M.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, T.; Parveen, A. Synergistic application of calcium oxide nanoparticles and farmyard manure induces cadmium tolerance in mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) by influencing physiological and biochemical parameters. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0282531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Li, T.; Mei, X.Y.; Ruan, M.J.; Wu, Y.Q.; Zu, Y.Q. Effects of Two Exogenous Calcium on Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics and Cadmiun Accumulation of Panax notoginseng of Cadmium Stress. Guizhou Agricultural Sciences China. 2019, 47, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Y.; Pan, Q.W.; Muhammad, F.; Zhang, L.l.; Gong, H.; Liu, L.J.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.T.; Pu, Y.Y.; Fang, Y.; Ma, L.; Sun, W.C. Effects of exogenous calcium and calcium inhibitor on physiological characteristics of winter turnip rape (Brassica rapa) under low temperature stress. Junyan et al. BMC Plant Biology. 2024, 24, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourato, M.; Reis, R.; Louro, L.M. Characterization of plant antioxidative system in response to abiotic stresses: a focus on heavy metal toxicity[M]. Advances in Selected Plant Physiology Aspects. 2012, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L.; Feng, X.Y.; Qiu, G.Y. Inhibition Roles of Calcium in Cadmium Uptake and Translocation in Rice: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treesubsuntorn, C.; Thiravetyan, P. Calcium acetate-induced reduction of cadmium accumulation in Oryza sativa: expression of auto-inhibited calcium-ATPase and cadmium transporters. Plant Biology. 2019, 21, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.K.; Chen, L. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defense mechanisms. Frontiers in plant science. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Wang, N.; Liu, R.X. Cinnamaldehyde Facilitates Cadmium Tolerance by Modulating Ca2+ in Brassica rapa. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2021, 232. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, G.Y.; Fang, Q.; Lu, H.J.; Hu, H.X. Calcium decreases cadmium concentration in root but facilitates cadmium translocation from root to shoot in rice. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Chl a (mg g-1 FW) | Chl b (mg g-1 FW) | Caro. (mg g-1 FW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 14.37±0.10a | 3.02±0.12b | 2.20±0.10a |

| K-1 | 13.17±0.30b | 4.13±0.06a | 1.83±0.11b |

| K-2 | 12.08±0.37c | 2.96±0.18b | 1.71±0.11b |

| K-3 | 13.11±0.68d | 4.29±0.13a | 2.25±0.12a |

| Treatment CK |

Cd Concentration(μg g-1) | Transfer Coefficient(IF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Above-Ground Parts | Roots | Cd Above-Ground Parts/Cd Roots | |

| K-1 | 2.18±0.04c | 18.13±0.31b | 0.1201±0.0025b |

| K-2 | 3.37±0.11b | 19.88±0.21c | 0.1695±0.0005a |

| K-3 | 3.43±0.10a | 20.71±0.14a | 0.1656±0.0010a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).