Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

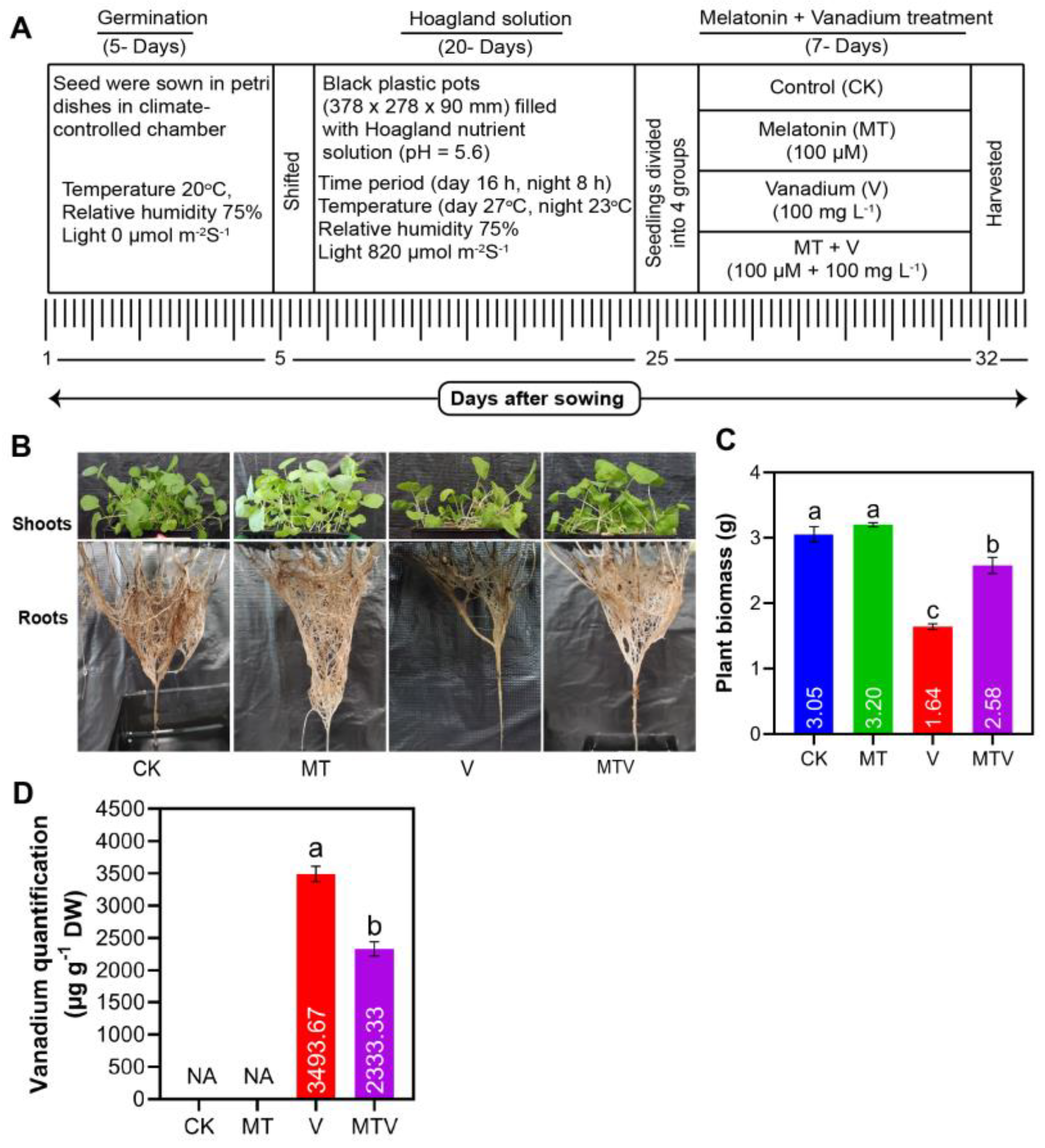

2.1. B. napus Phenotype Attributes Under V Stress and MT Supplementation

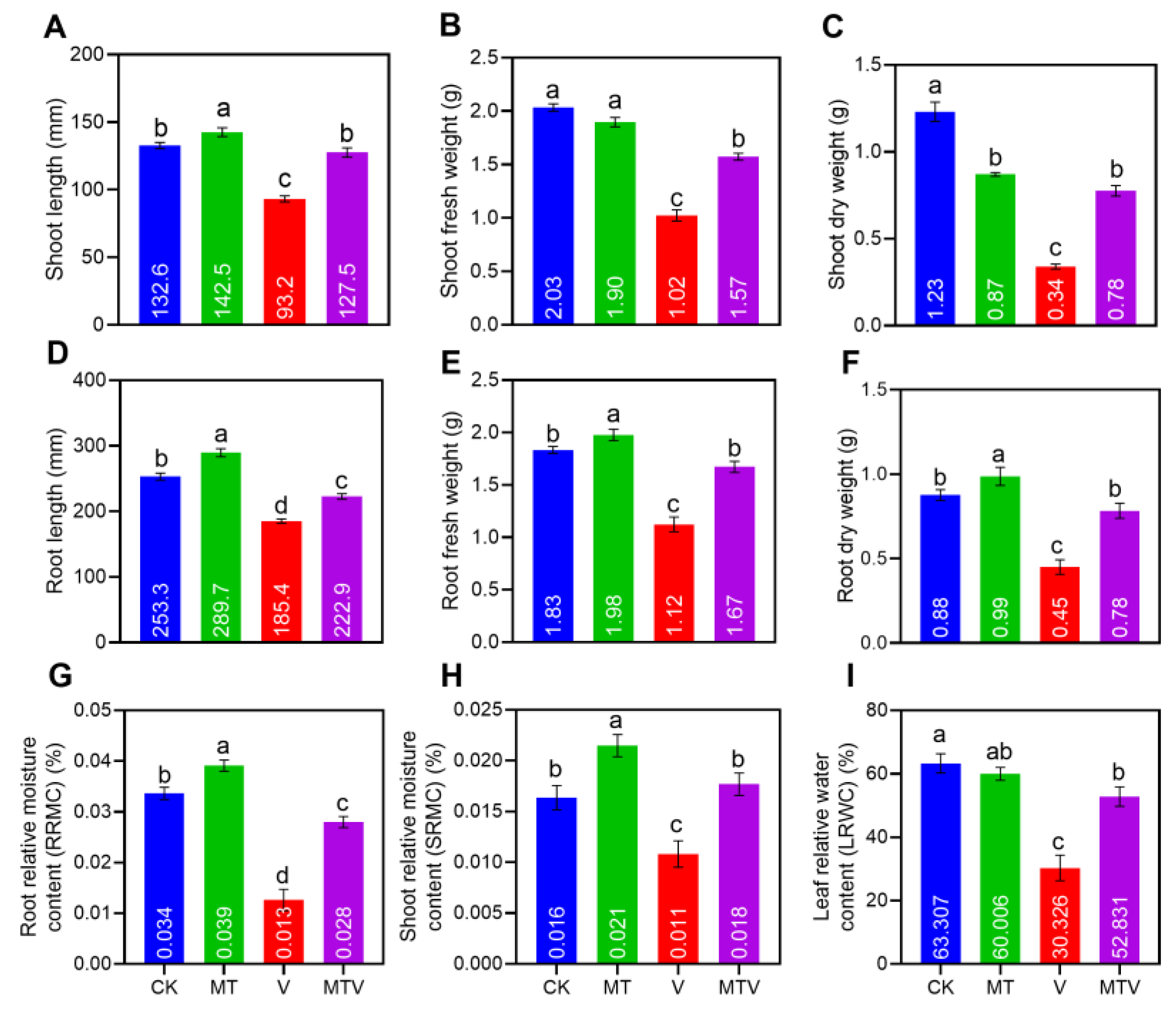

2.2. Analyses of B. napus Seedlings Phenotypic Attributes

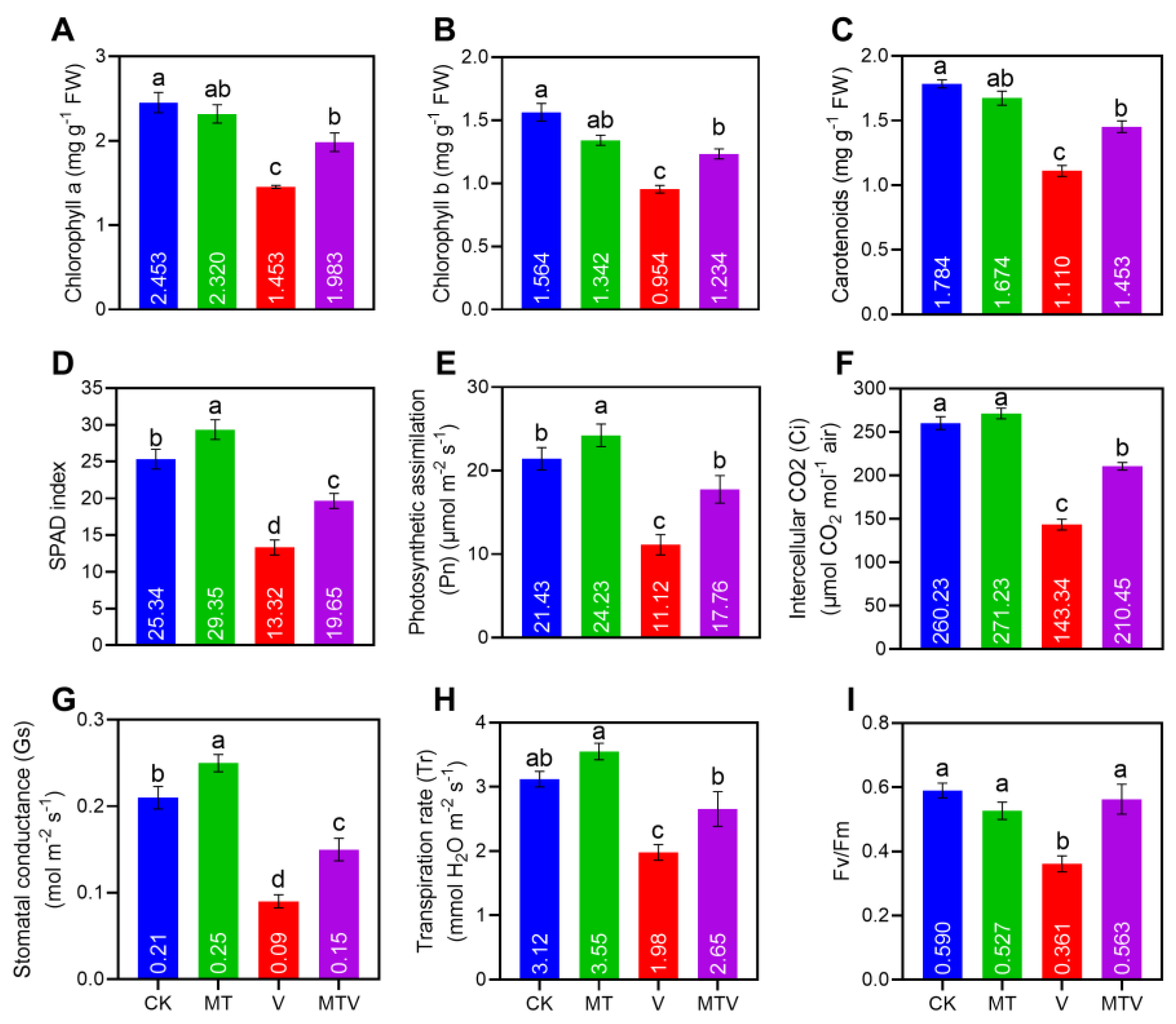

2.3. SPAD Index, Photosynthesis, and Leaf Gas Exchange Parameters

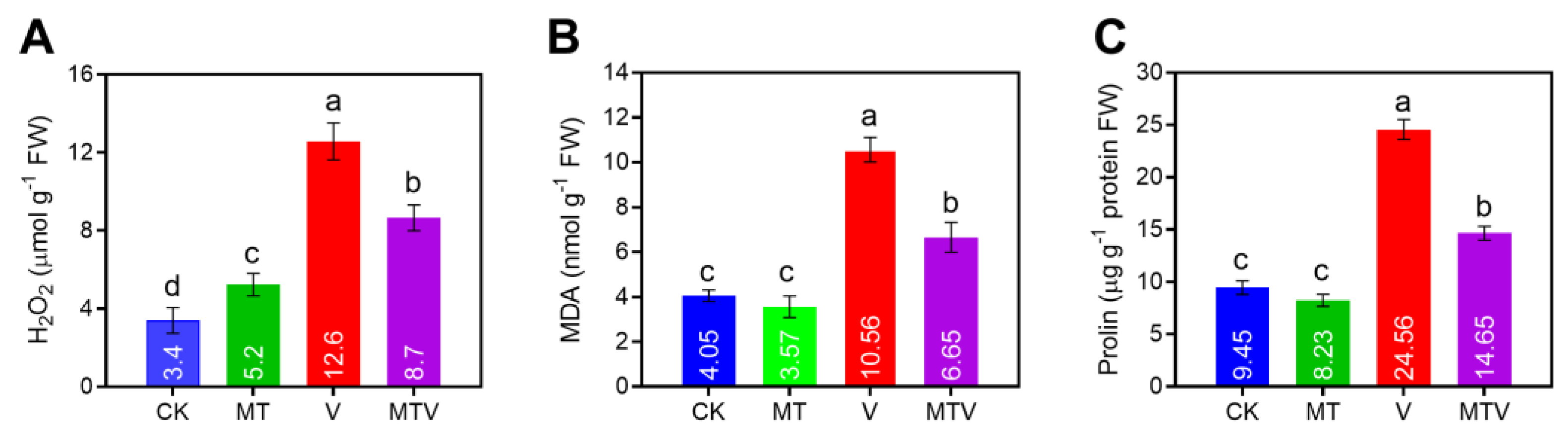

2.4. Vanadium (V) Induced Oxidative Stress and Proline Accumulation

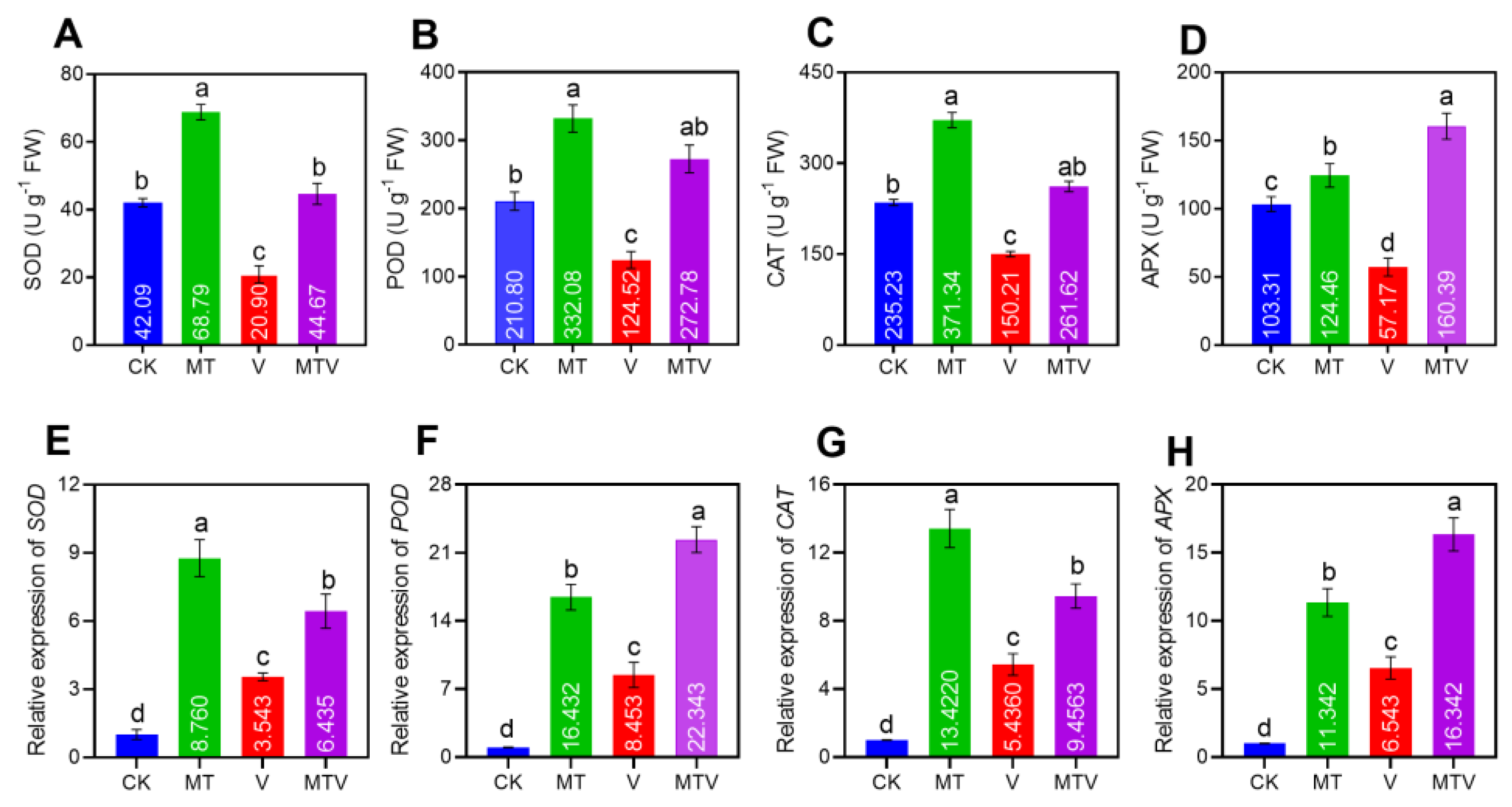

2.5. Analyses of Antioxidant Enzymes and Genes Activities

2.6. Transcriptome Assembly and Data Analyses Under V Stress and MT Supplementation

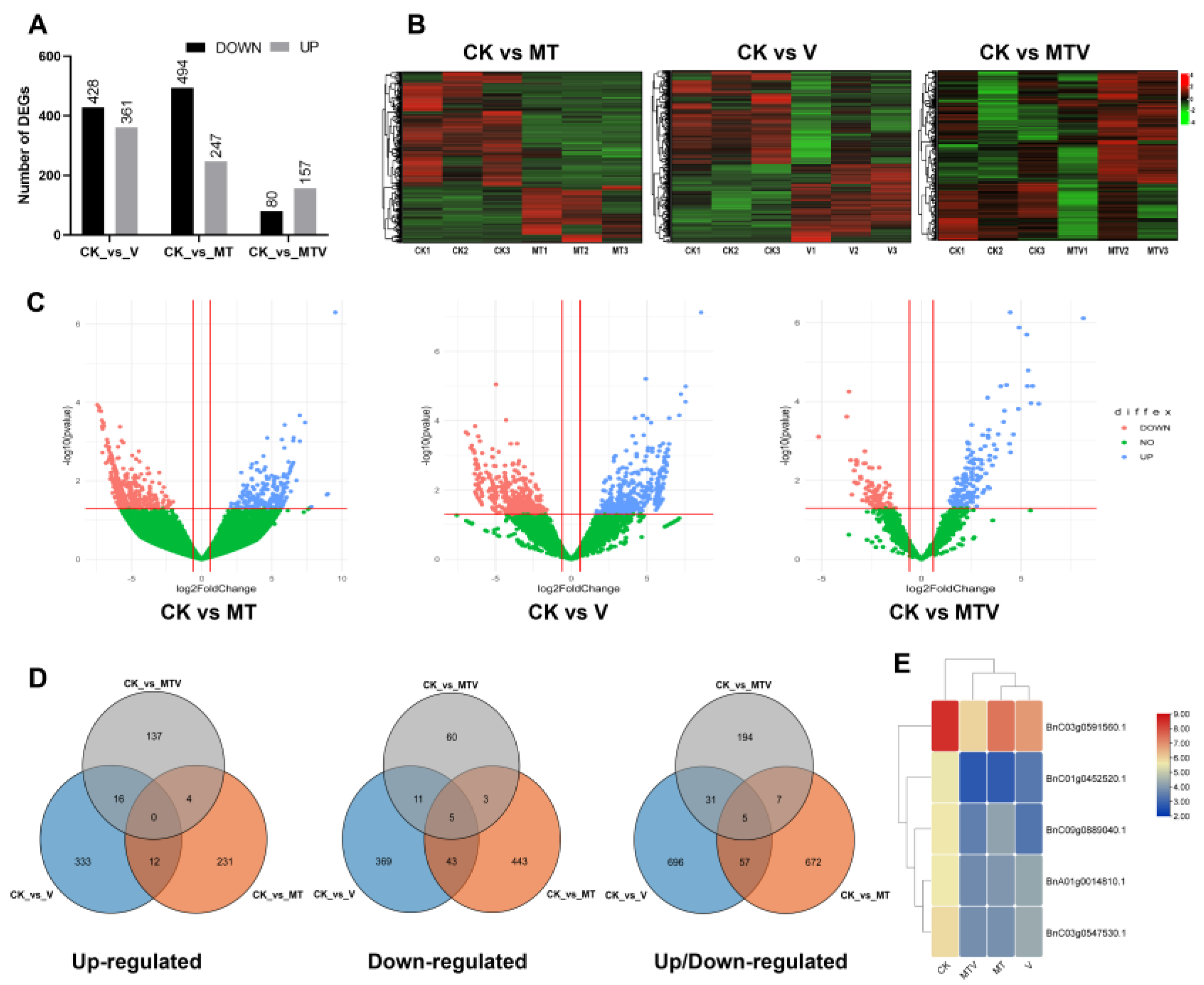

2.7. Analyses of Deferentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Under V Stress and MT Supplementation

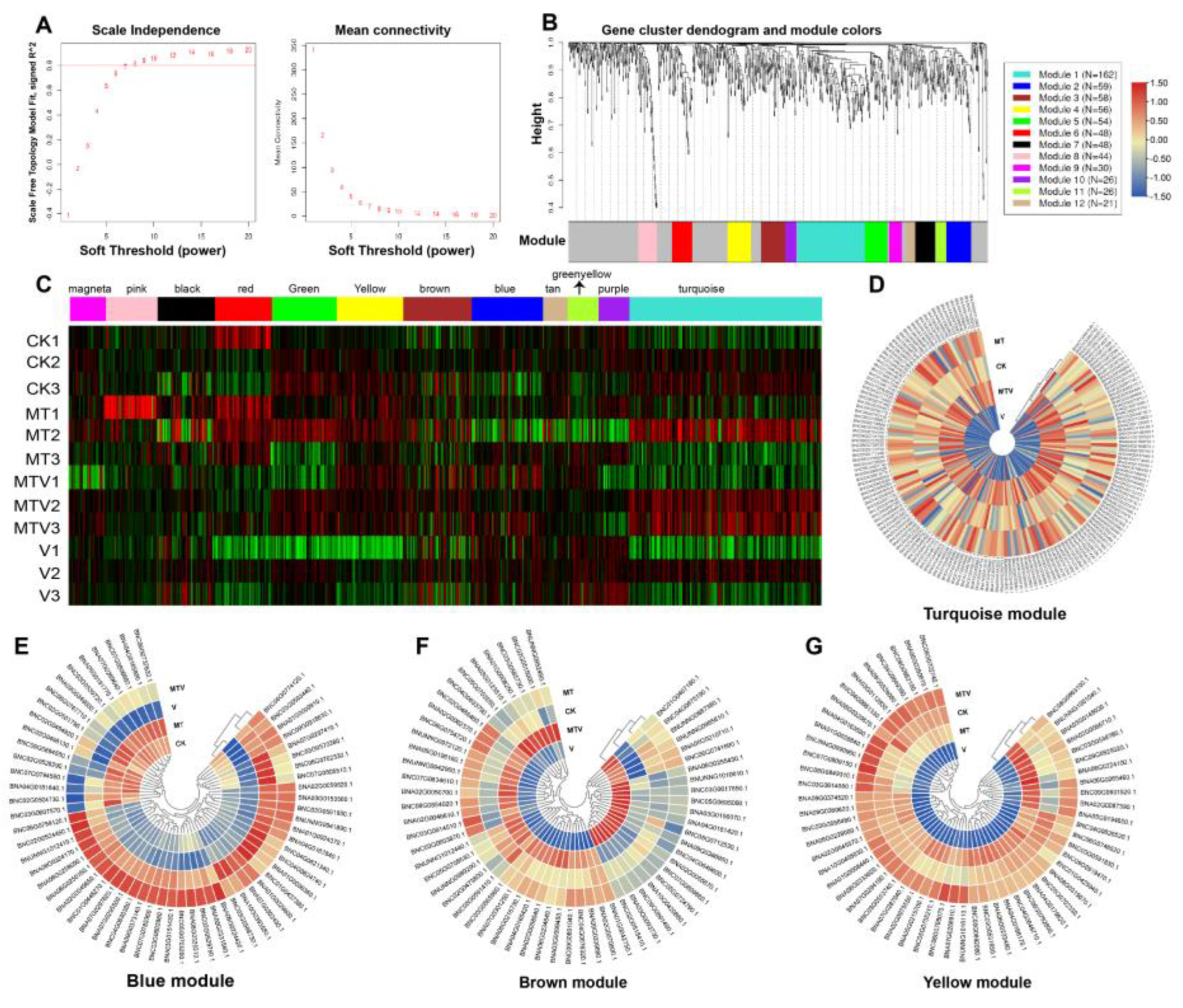

2.8. Construction of Weighted Genes Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) and Identification of Key Modules

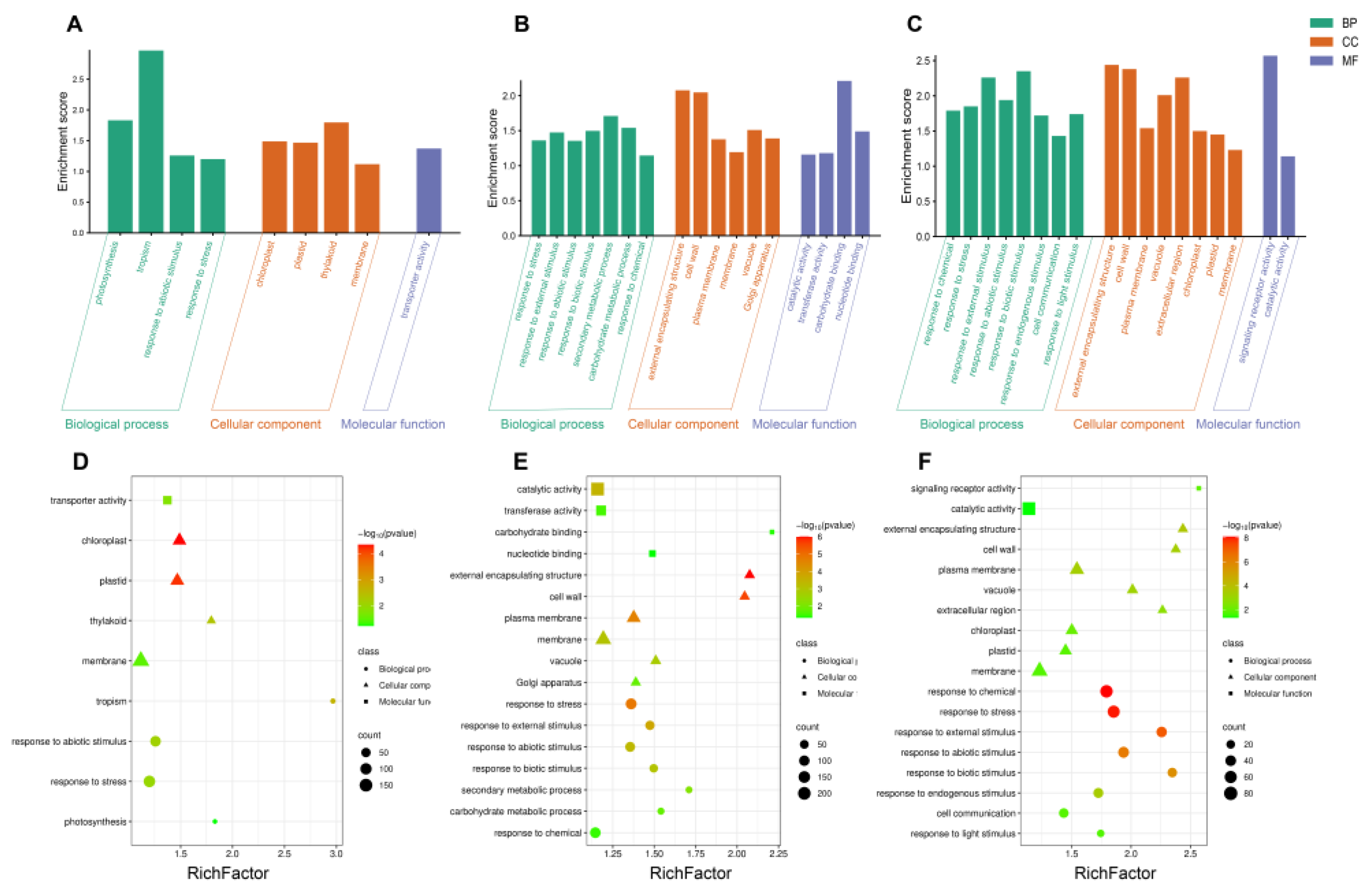

2.9. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses of DEGs

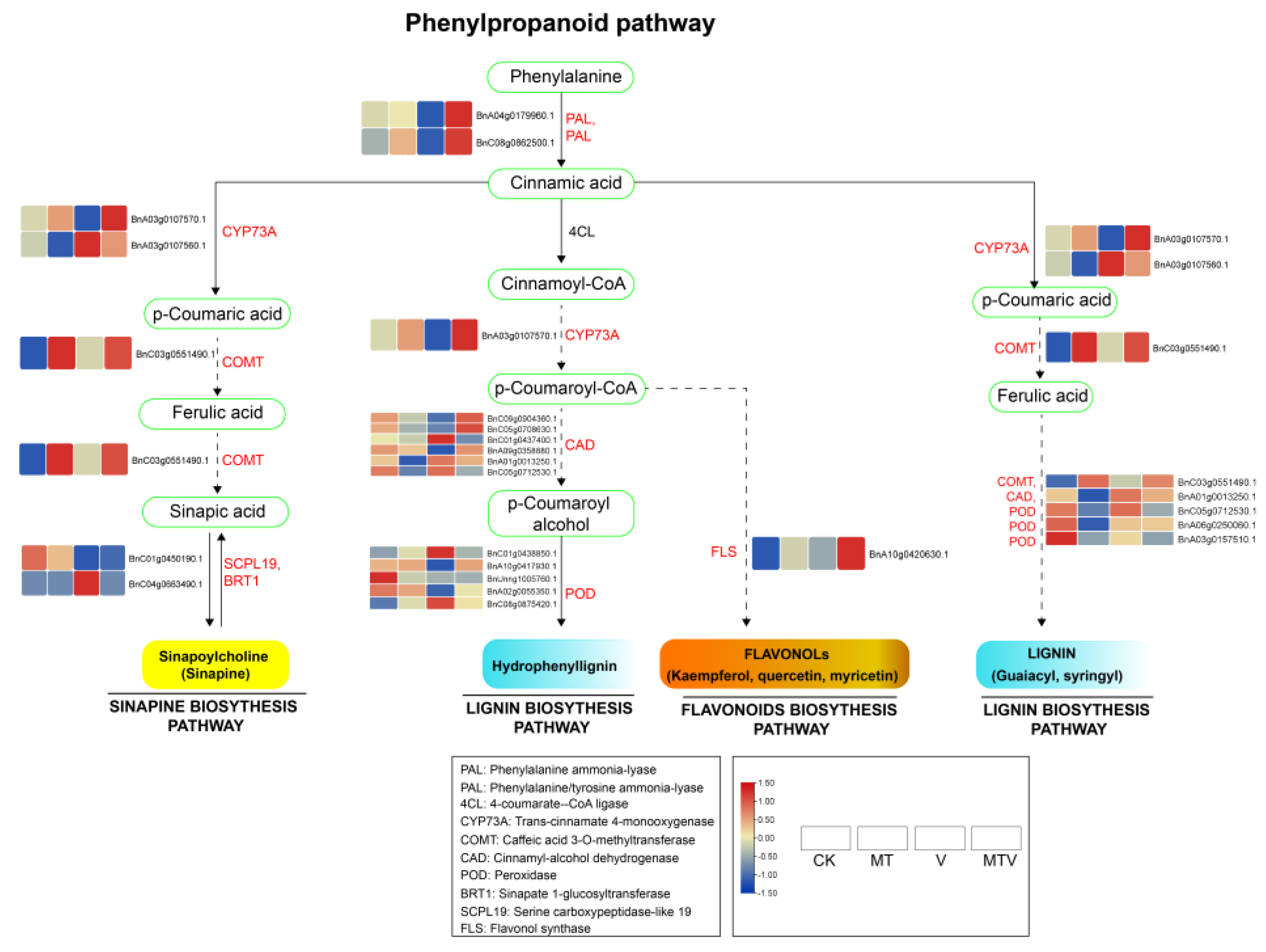

2.10. Genes Involved in Phenylpropanoid Pathway

2.10.1. Flavonoids Biosynthesis

2.10.2. Liginin Biosynthesis

2.10.3. Sinapine Biosynthesis

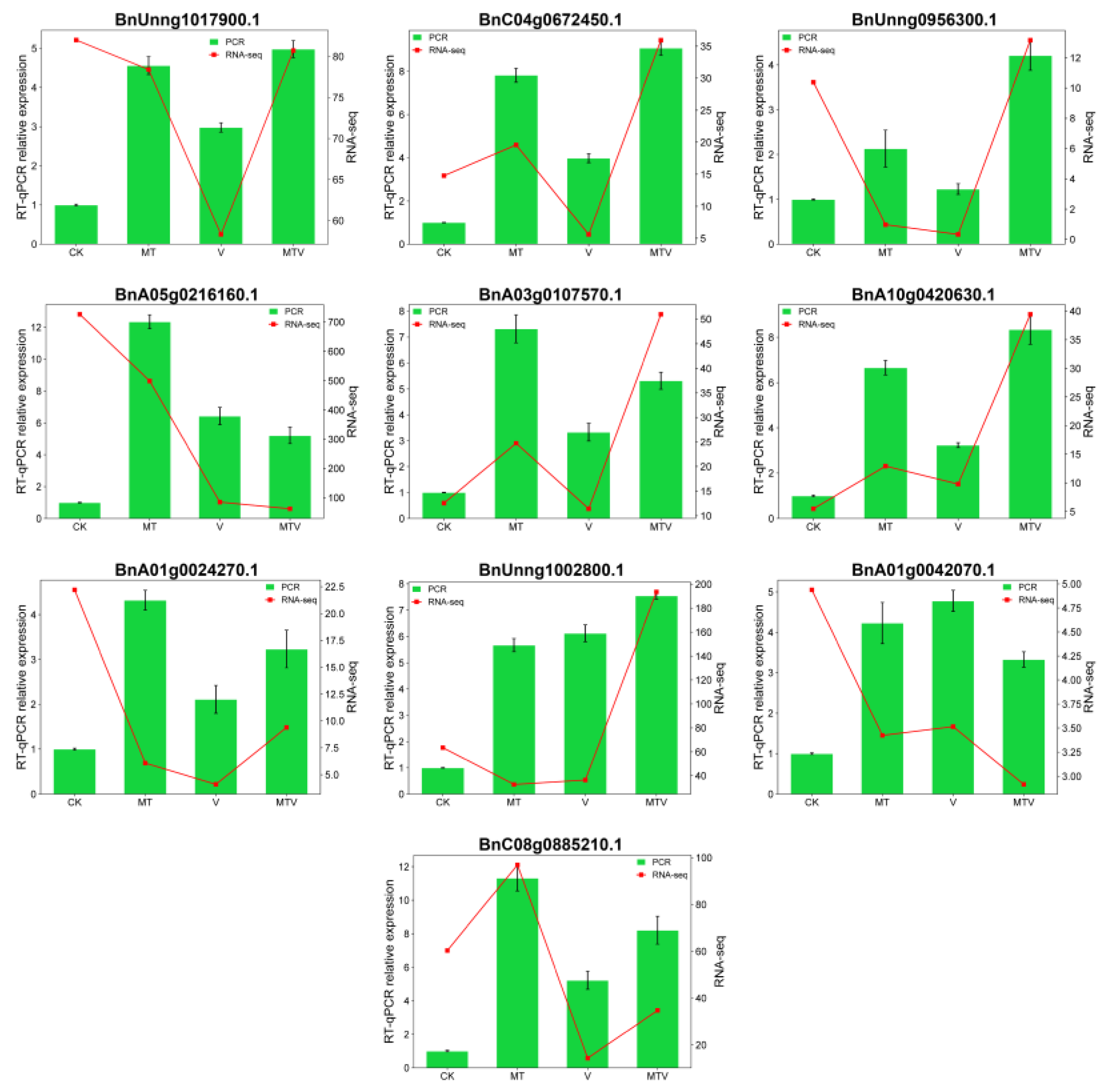

2.11. RT-qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Data

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Setup and Growing Conditions

4.2. Measurement of V Accumulation

4.3. Plant Biomass and Relative Water Contents (RWCs) Parameters

4.4. Leaf Pigments, Chlorophyll Florescence, and Gassious Exchange Parameters

4.5. Quantification of Oxidative Stress Markers; MDA, H2O2, and Proline

4.6. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Accumulation

4.7. RNA Extraction, Library Construction and RNA-Seq

4.8. RNA-Seq Data Processing, De Novo Transcriptome Assembly, and Functional Annotation

4.9. Genes Co-Expression Network Analysis

4.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, D., Chen, Q., Chen, W., Guo, Q., Xia, Y., Wang, S., ... & Liang, G. (2021). Physiological and transcription analyses reveal the regulatory mechanism of melatonin in inducing drought resistance in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) seedlings. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 181, 104291. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M. A., Huang, Y., Luo, D., Mehmood, S. S., Raza, A., Duan, L., ... & Lv, Y. (2025). Integrative analyses reveal Bna-miR397a–BnaLAC2 as a potential modulator of low-temperature adaptability in Brassica napus L. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 23(6), 1968-1987. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Xia, Y.; Li, R.; Bai, G.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Guo, P. Non-Coding RNAs: Functional Roles in the Regulation of Stress Response in Brassica Crops. Genomics 2020, 112, 1419–1424. [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V. Molecular Genetic Perspectives on Cross-Talk and Specificity in Abiotic Stress Signalling in Plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2003, 55, 225–236. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Q. U., Garg, V., Raza, A., Nazir, M. F., Hui, L., Khan, D., ... & Varshney, R. K. (2024). Unique regulatory network of dragon fruit simultaneously mitigates the effect of vanadium pollutant and environmental factors. Physiologia plantarum, 176(4), e14416. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. A., Shahid, R., Ren, M. X., Altaf, M. M., Jahan, M. S., & Khan, L. U. (2021). Melatonin mitigates nickel toxicity by improving nutrient uptake fluxes, root architecture system, photosynthesis, and antioxidant potential in tomato seedling. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 21(3), 1842-1855. [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M., Mushtaq, M. A., Nawaz, M. A., Ashraf, M., Rizwan, M. S., Mehmood, S., ... & Coleman, M. D. (2018). Physiological and anthocyanin biosynthesis genes response induced by vanadium stress in mustard genotypes with distinct photosynthetic activity. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 62, 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M., Mushtaq, M. A., Rizwan, M. S., Arif, M. S., Yousaf, B., Ashraf, M., ... & Tu, S. (2016). Comparison of antioxidant enzyme activities and DNA damage in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes exposed to vanadium. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(19), 19787-19796. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Z. (2018). New-demand oriented oilseed rape industry developing strategy. Chinese Journal of Oil Crop Sciences, 40(5), 613-617.

- Chen, L., Zhu, Y. Y., Luo, H. Q., & Yang, J. Y. (2020). Characteristic of adsorption, desorption, and co-transport of vanadium on humic acid colloid. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 190, 110087. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Z., Zhang, Y. X., Yang, J. Y., Zhou, Y., & Wang, C. Q. (2021). Effect of vanadium on testa, seed germination, and subsequent seedling growth of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 40(4), 1566-1578. [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M., Rizwan, M. S., Xiong, S., Li, H., Ashraf, M., Shahzad, S. M., ... & Tu, S. (2015). Vanadium, recent advancements and research prospects: A review. Environment international, 80, 79-88. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. M., Diao, X. P., Altaf, M. A., ur Rehman, A., Shakoor, A., Khan, L. U., ... & Ahmad, P. (2022). Silicon-mediated metabolic upregulation of ascorbate glutathione (AsA-GSH) and glyoxalase reduces the toxic effects of vanadium in rice. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 436, 129145. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. A., Shahid, R., Ren, M. X., Khan, L. U., Altaf, M. M., Jahan, M. S., ... & Shahid, M. A. (2022). Protective mechanisms of melatonin against vanadium phytotoxicity in tomato seedlings: insights into nutritional status, photosynthesis, root architecture system, and antioxidant machinery. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 41(8), 3300-3316. [CrossRef]

- Aihemaiti, A., Jiang, J., Gao, Y., Meng, Y., Zou, Q., Yang, M., ... & Tuerhong, T. (2019). The effect of vanadium on essential element uptake of Setaria viridis’ seedlings. Journal of Environmental Management, 237, 399-407. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Z., Yang, J. Y., Zhang, Y. X., Wang, C. Q., Guo, S. S., & Yu, Y. Q. (2021). Growth responses, accumulation, translocation and distribution of vanadium in tobacco and its potential in phytoremediation. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 207, 111297. [CrossRef]

- Vachirapatama, N., Jirakiattikul, Y., Dicinoski, G., Townsend, A. T., & Haddad, P. R. (2011). Effect of vanadium on plant growth and its accumulation in plant tissues. Sonklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology, 33(3), 255.

- Imtiaz, M., Rizwan, M. S., Mushtaq, M. A., Yousaf, B., Ashraf, M., Ali, M., ... & Tu, S. (2017). Interactive effects of vanadium and phosphorus on their uptake, growth and heat shock proteins in chickpea genotypes under hydroponic conditions. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 134, 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. K., Saha, R., & Saha, B. (2015). Toxicity of inorganic vanadium compounds. Research on Chemical Intermediates, 41(7), 4873-4897. [CrossRef]

- Khan, D., Yang, X., He, G., Khan, R. A. A., Usman, B., Hui, L., ... & Wang, H. F. (2024). Comparative physiological and transcriptomics profiling provides integrated insight into melatonin mediated salt and copper stress tolerance in Selenicereus undatus L. Plants, 13(24), 3602. [CrossRef]

- Bose, S. K., & Howlader, P. (2020). Melatonin plays multifunctional role in horticultural crops against environmental stresses: A review. Environmental and experimental botany, 176, 104063. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., Xu, X., Li, L., Sun, Q., Wang, Q., Huang, H., ... & Zhang, J. (2023). Melatonin-mediated development and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1100827. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A. B., Case, J. D., Takahashi, Y., Lee, T. H., & Mori, W. (1958). Isolation of melatonin, the pineal gland factor that lightens melanocyteS1. Journal of the american chemical society, 80(10), 2587-2587.

- Niazi Khogeh, M., Rezaei, M., & Ghasimi Hagh, Z. (2022). Effect of salicylic acid and melatonin on chlorophyll fluorescence and initial growth of greenhouse tomatoes in salinity stress. Journal of Plant Production Research, 29(2), 265-282.

- Arnao, M. B., & Hernández-Ruiz, J. (2019). Melatonin: a new plant hormone and/or a plant master regulator?. Trends in Plant Science, 24(1), 38-48. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. A., Shahid, R., Ren, M. X., Altaf, M. M., Khan, L. U., Shahid, S., & Jahan, M. S. (2021). Melatonin alleviates salt damage in tomato seedling: A root architecture system, photosynthetic capacity, ion homeostasis, and antioxidant enzymes analysis. Scientia Horticulturae, 285, 110145. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F., Wei, H., Ding, Y., Li, W., Liu, Z., Chen, L., ... & Li, G. (2021). Melatonin regulates antioxidant strategy in response to continuous salt stress in rice seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 165, 239-250. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G., Zhao, Y., Yu, X., Kiprotich, F., Han, H., Guan, R., ... & Shen, W. (2018). Nitric oxide is required for melatonin-enhanced tolerance against salinity stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(7), 1912. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M. H., Alamri, S., Al-Khaishany, M. Y., Khan, M. N., Al-Amri, A., Ali, H. M., ... & Alsahli, A. A. (2019). Exogenous melatonin counteracts NaCl-induced damage by regulating the antioxidant system, proline and carbohydrates metabolism in tomato seedlings. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(2), 353. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Li, Q. T., Chu, Y. N., Reiter, R. J., Yu, X. M., Zhu, D. H., ... & Chen, S. Y. (2015). Melatonin enhances plant growth and abiotic stress tolerance in soybean plants. Journal of experimental botany, 66(3), 695-707. [CrossRef]

- Jia, C., Yu, X., Zhang, M., Liu, Z., Zou, P., Ma, J., & Xu, Y. (2020). Application of melatonin-enhanced tolerance to high-temperature stress in cherry radish (Raphanus sativus L. var. radculus pers). Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 39(2), 631-640. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R. K., Lal, M. K., Kumar, R., Chourasia, K. N., Naga, K. C., Kumar, D., ... & Zinta, G. (2021). Mechanistic insights on melatonin-mediated drought stress mitigation in plants. Physiologia Plantarum, 172(2), 1212-1226. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C., Okant, M., Ugurlar, F., Alyemeni, M. N., Ashraf, M., & Ahmad, P. (2019). Melatonin-mediated nitric oxide improves tolerance to cadmium toxicity by reducing oxidative stress in wheat plants. Chemosphere, 225, 627-638. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B., Sikdar, A., Islam, S., Hasan, K., Li, M., & Qiu, D. (2021). Physiological and molecular responses to acid rain stress in plants and the impact of melatonin, glutathione and silicon in the amendment of plant acid rain stress. Molecules, 26(4), 862. [CrossRef]

- Hahlbrock, K., & Scheel, D. (1989). Physiology and molecular biology of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Annual review of plant physiology and plant molecular biology, 40(1), 347-369. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C. M., & Chapple, C. (2011). The phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis. The Arabidopsis Book/American Society of Plant Biologists, 9, e0152.

- Nawaz, M. A., Huang, Y., Bie, Z., Ahmed, W., Reiter, R. J., Niu, M., & Hameed, S. (2016). Melatonin: current status and future perspectives in plant science. Frontiers in plant science, 6, 1230. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H., Ni, Z., Hu, R., Lin, L., Deng, H., Wang, J., ... & Liang, D. (2020). Melatonin alleviates drought stress by a non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidative system in kiwifruit seedlings. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(3), 852. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Dai, L., Wei, Y., Deng, Z., & Li, D. (2020). Melatonin enhances salt stress tolerance in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) seedlings. Industrial crops and products, 145, 111990. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. A., Shahid, R., Ren, M. X., Naz, S., Altaf, M. M., Khan, L. U., ... & Ahmad, P. (2022). Melatonin improves drought stress tolerance of tomato by modulating plant growth, root architecture, photosynthesis, and antioxidant defense system. Antioxidants, 11(2), 309. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M. S., Guo, S., Sun, J., Shu, S., Wang, Y., Abou El-Yazied, A., ... & Hasan, M. M. (2021). Melatonin-mediated photosynthetic performance of tomato seedlings under high-temperature stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 167, 309-320. [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A., Mohammad, F., Wani, S. H., & Siddique, K. M. (2019). Salicylic acid enhances nickel stress tolerance by up-regulating antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in mustard plants. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 180, 575-587. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. U., Li, Y., Hussain, S., Hussain, B., Khan, W. U. D., Riaz, L., ... & Cheng, H. (2023). Role of phytohormones in heavy metal tolerance in plants: A review. Ecological Indicators, 146, 109844. [CrossRef]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Effects of Drought Stress on the Seedling Growth, Development, and Metabolic Activity in Different Cultivars of Canola. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2018, 64, 360–369. [CrossRef]

- He, W. Y., Liao, W., Yang, J. Y., Jeyakumar, P., & Anderson, C. (2020). Removal of vanadium from aquatic environment using phosphoric acid modified rice straw. Bioremediation Journal, 24(1), 80-89. [CrossRef]

- Mir, A. R., Pichtel, J., & Hayat, S. (2021). Copper: uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants and management of Cu-contaminated soil. Biometals, 34(4), 737-759. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M. S., Wang, Y., Shu, S., Zhong, M., Chen, Z., Wu, J., ... & Guo, S. (2019). Exogenous salicylic acid increases the heat tolerance in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L) by enhancing photosynthesis efficiency and improving antioxidant defense system through scavenging of reactive oxygen species. Scientia Horticulturae, 247, 421-429. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M. M., Diao, X. P., Wang, H., Khan, L. U., Rehman, A. U., Shakoor, A., ... & Farooq, T. H. (2022). Salicylic acid induces vanadium stress tolerance in rice by regulating the AsA-GSH cycle and glyoxalase system. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 22(2), 1983-1999. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Luo, A., Li, H., Chen, Z., Guan, Z., Escalona, V. H., ... & Yu, X. (2025). Variation in nutritional qualities and antioxidant capacity of different leaf mustard cultivars. Horticulturae, 11(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Hodzic, E., Galijasevic, S., Balaban, M., Rekanovic, S., Makic, H., Kukavica, B., & Mihajlovic, D. (2021). The protective role of melatonin under heavy metal-induced stress in Melissa Officinalis L. Turkish journal of chemistry, 45(3), 737-748. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Wang, Y., Ma, X., Ouyang, Z., Deng, L., Shen, S., ... & Sun, K. (2022). Melatonin alleviates copper toxicity via improving ROS metabolism and antioxidant defense response in tomato seedlings. Antioxidants, 11(4), 758. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Wang, J., Xu, D., Tao, S., Chong, S., Yan, D., ... & Zheng, B. (2020). Melatonin regulates the functional components of photosynthesis, antioxidant system, gene expression, and metabolic pathways to induce drought resistance in grafted Carya cathayensis plants. Science of the Total Environment, 713, 136675. [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M. S., Abdalla, A. M., Abd Elhamid, E. M., & Ezzo, M. I. (2020). Role of melatonin in improving growth, yield quantity and quality of Moringa oleifera L. plant under drought stress. Bulletin of the National Research Centre, 44(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Zhang, Z. K., Chai, H. K., Cheng, N., Yang, Y., Wang, D. N., ... & Cao, W. (2016). Melatonin treatment delays postharvest senescence and regulates reactive oxygen species metabolism in peach fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 118, 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M. A., Jiao, Y., Chen, C., Shireen, F., Zheng, Z., Imtiaz, M., ... & Huang, Y. (2018). Melatonin pretreatment improves vanadium stress tolerance of watermelon seedlings by reducing vanadium concentration in the leaves and regulating melatonin biosynthesis and antioxidant-related gene expression. Journal of Plant Physiology, 220, 115-127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Shi, Z., Zhang, X., Zheng, S., Wang, J., & Mo, J. (2020). Alleviating effects of exogenous melatonin on salt stress in cucumber. Scientia Horticulturae, 262, 109070. [CrossRef]

- Simlat, M., Ptak, A., Skrzypek, E., Warchoł, M., Morańska, E., & Piórkowska, E. (2018). Melatonin significantly influences seed germination and seedling growth of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. PeerJ, 6, e5009. [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. (2017). ROS are good. Trends in plant science, 22(1), 11-19.

- Ahammed, G. J., Xu, W., Liu, A., & Chen, S. (2019). Endogenous melatonin deficiency aggravates high temperature-induced oxidative stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 161, 303-311. [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M. B., & Hernández-Ruiz, J. (2015). Functions of melatonin in plants: a review. Journal of pineal research, 59(2), 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S., & Murata, N. (2008). How do environmental stresses accelerate photoinhibition?. Trends in plant science, 13(4), 178-182. [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S. M., Hosseini, M. S., Abadía, J., & Marjani, M. (2020). Melatonin foliar sprays elicit salinity stress tolerance and enhance fruit yield and quality in strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa Duch.). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 149, 313-323. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, B. M., Geisler, M., Bigler, L., & Ringli, C. (2011). Flavonols accumulate asymmetrically and affect auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 156(2), 585-595. [CrossRef]

- Peer, W. A., Blakeslee, J. J., Yang, H., & Murphy, A. S. (2011). Seven things we think we know about auxin transport. Molecular plant, 4(3), 487-504. [CrossRef]

- Buer, C. S., Kordbacheh, F., Truong, T. T., Hocart, C. H., & Djordjevic, M. A. (2013). Alteration of flavonoid accumulation patterns in transparent testa mutants disturbs auxin transport, gravity responses, and imparts long-term effects on root and shoot architecture. Planta, 238(1), 171-189. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, H., Tohge, T., Viehöver, P., Fernie, A. R., Weisshaar, B., & Stracke, R. (2016). Natural variation in flavonol accumulation in Arabidopsis is determined by the flavonol glucosyltransferase BGLU6. Journal of experimental botany, 67(5), 1505-1517. [CrossRef]

- Mouradov, A., & Spangenberg, G. (2014). Flavonoids: a metabolic network mediating plants adaptation to their real estate. Frontiers in plant science, 5, 620. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Dai, L., Wei, Y., Deng, Z., & Li, D. (2020). Melatonin enhances salt stress tolerance in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) seedlings. Industrial crops and products, 145, 111990. [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D. I., & Hoagland, D. R. (1944). The investigation of plant nutrition by artificial culture methods. Biological Reviews, 19(2), 55-67. [CrossRef]

- Sami, A., Shah, F. A., Abdullah, M., Zhou, X., Yan, Y., Zhu, Z., & Zhou, K. (2020). Melatonin mitigates cadmium and aluminium toxicity through modulation of antioxidant potential in Brassica napus L. Plant Biology, 22(4), 679-690. [CrossRef]

- Hou, M., Hu, C., Xiong, L., Lu, C., 2013. Tissue accumulation and subcellular distribution of vanadium in Brassica juncea and Brassica chinensis. Microchemical Journal. 110, 575–578. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M., Chakraborty, A., & Raychaudhuri, S. S. (2013). Ionizing radiation induced changes in phenotype, photosynthetic pigments and free polyamine levels in Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek. Applied Radiation and Isotopes, 75, 44-49. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H. K. (1987). [34] Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Methods in enzymology (Vol. 148, pp. 350-382). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A. R. (1994). The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of plant physiology, 144(3), 307-313. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, U. S. C. H. L. I. W. A., Schliwa, U., & Bilger, W. (1986). Continuous recording of photochemical and non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching with a new type of modulation fluorometer. Photosynthesis research, 10(1), 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Chen, Y., Shi, C., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, S., ... & Chen, Q. (2018). SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience, 7(1), gix120. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Wang, S., Wei, L., Huang, Y., Liu, D., Jia, Y., ... & Yang, Q. Y. (2023). BnIR: A multi-omics database with various tools for Brassica napus research and breeding. Molecular Plant, 16(4), 775-789. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Li, M. C., Konaté, M. M., Chen, L., Das, B., Karlovich, C., ... & McShane, L. M. (2021). TPM, FPKM, or normalized counts? A comparative study of quantification measures for the analysis of RNA-seq data from the NCI patient-derived models repository. Journal of translational medicine, 19(1), 269. [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T. C., Mendell, J. T., & Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology, 33(3), 290-295. [CrossRef]

- Ge, S. X., Son, E. W., & Yao, R. (2018). iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC bioinformatics, 19(1), 534. [CrossRef]

- Khan, L. U., Cao, X., Zhao, R., Tan, H., Xing, Z., & Huang, X. (2022). Effect of temperature on yellow leaf disease symptoms and its associated areca palm velarivirus 1 titer in areca palm (Areca catechu L.). Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 1023386. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J., & Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods, 25(4), 402-408.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).