Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Details, Salt Treatments, and Sampling Layout

2.2. Assessment of Phenotypic Traits of Two Grapevine Rootstocks under Salt Stress

2.3. Assessment of Leaf Photosynthetic Pigment Contents

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Indicators

2.5. RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

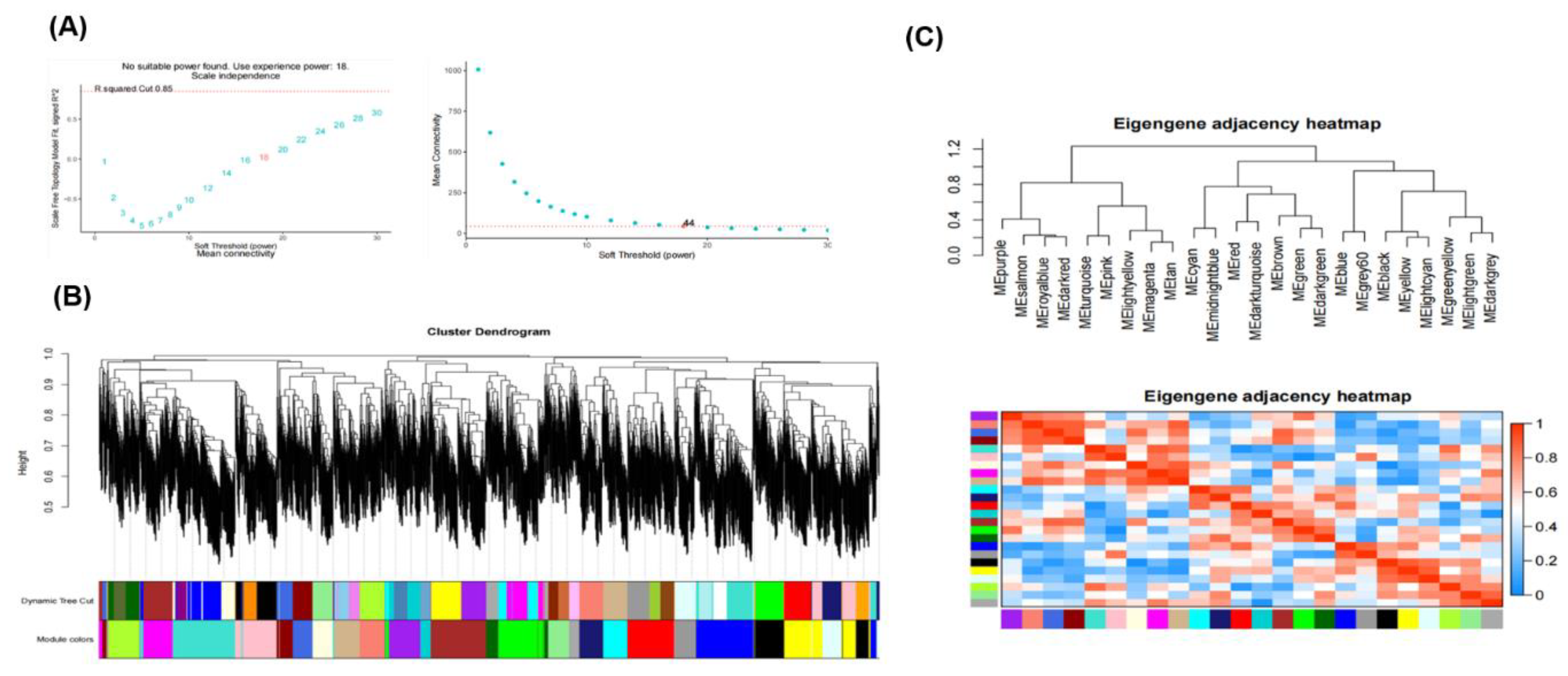

2.6. Construction of the Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

2.7. The Validation of RNA-Seq by RT-qPCR Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

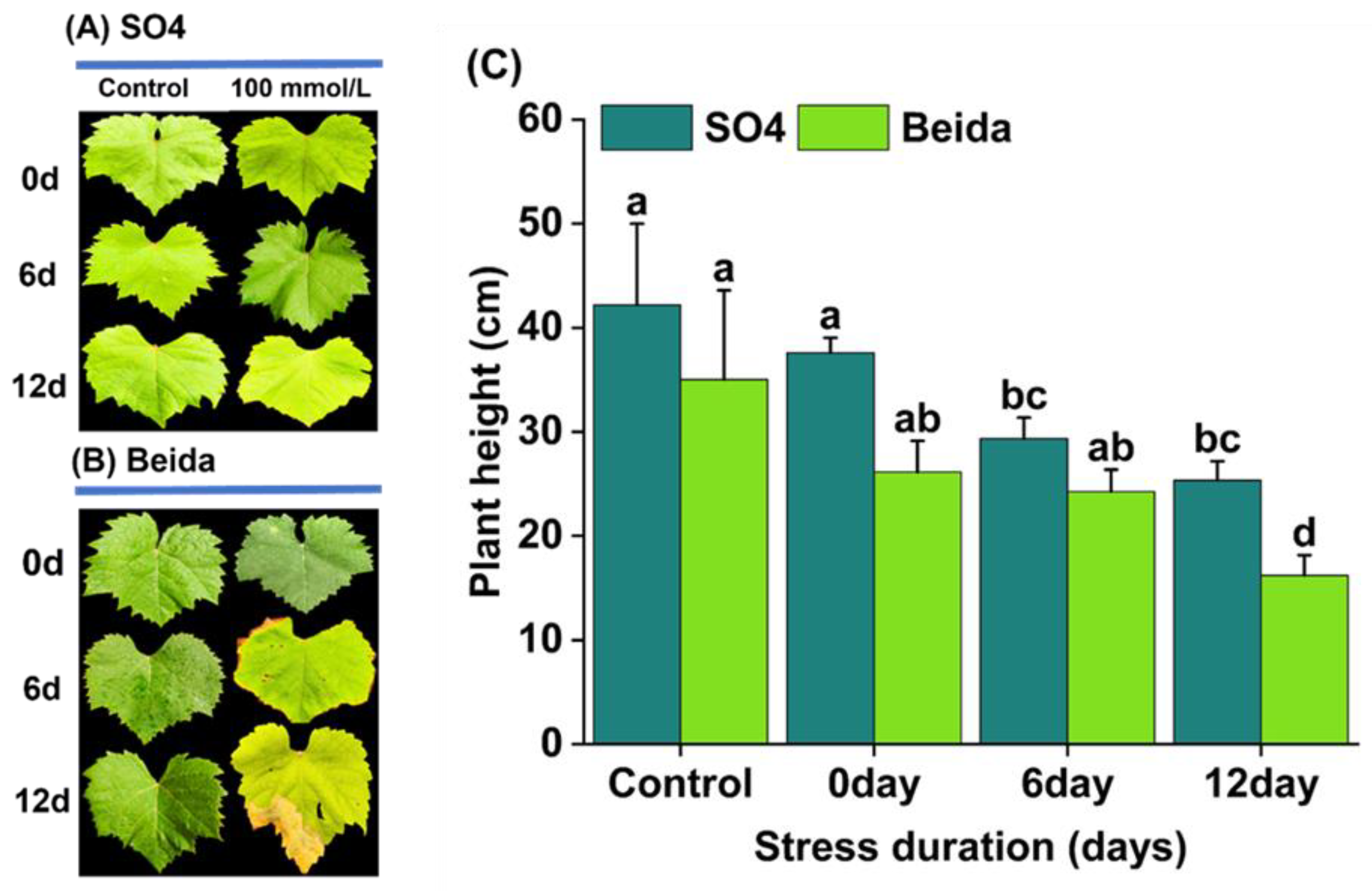

3.1. Effects of Salt Stress Treatments on Grapevine Rootstock Leaf Phenotypic Observation

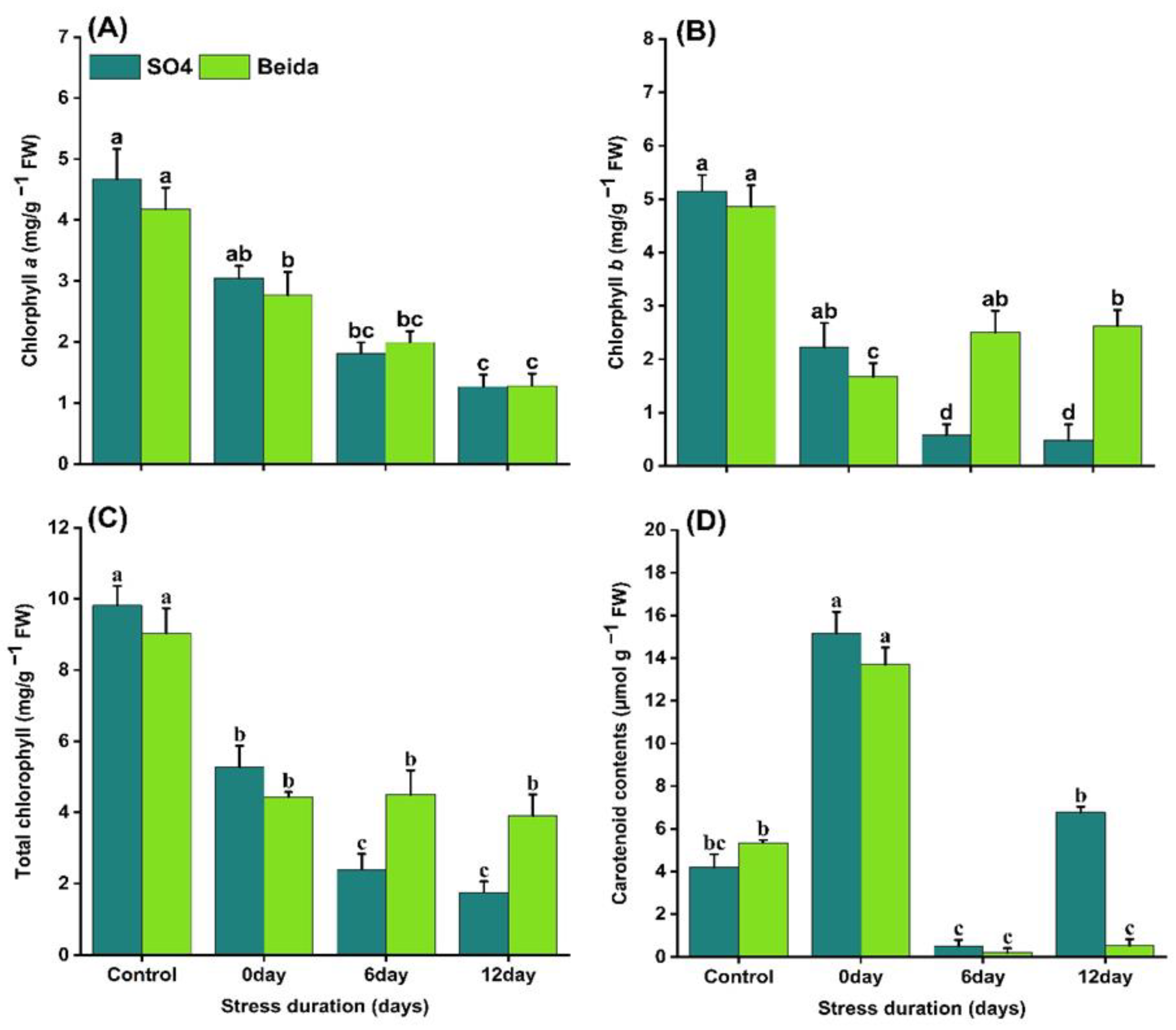

3.2. Effects of Salt Stress on Photosynthetic Pigmsnt Content of Grapevine Rootstocks Leaves

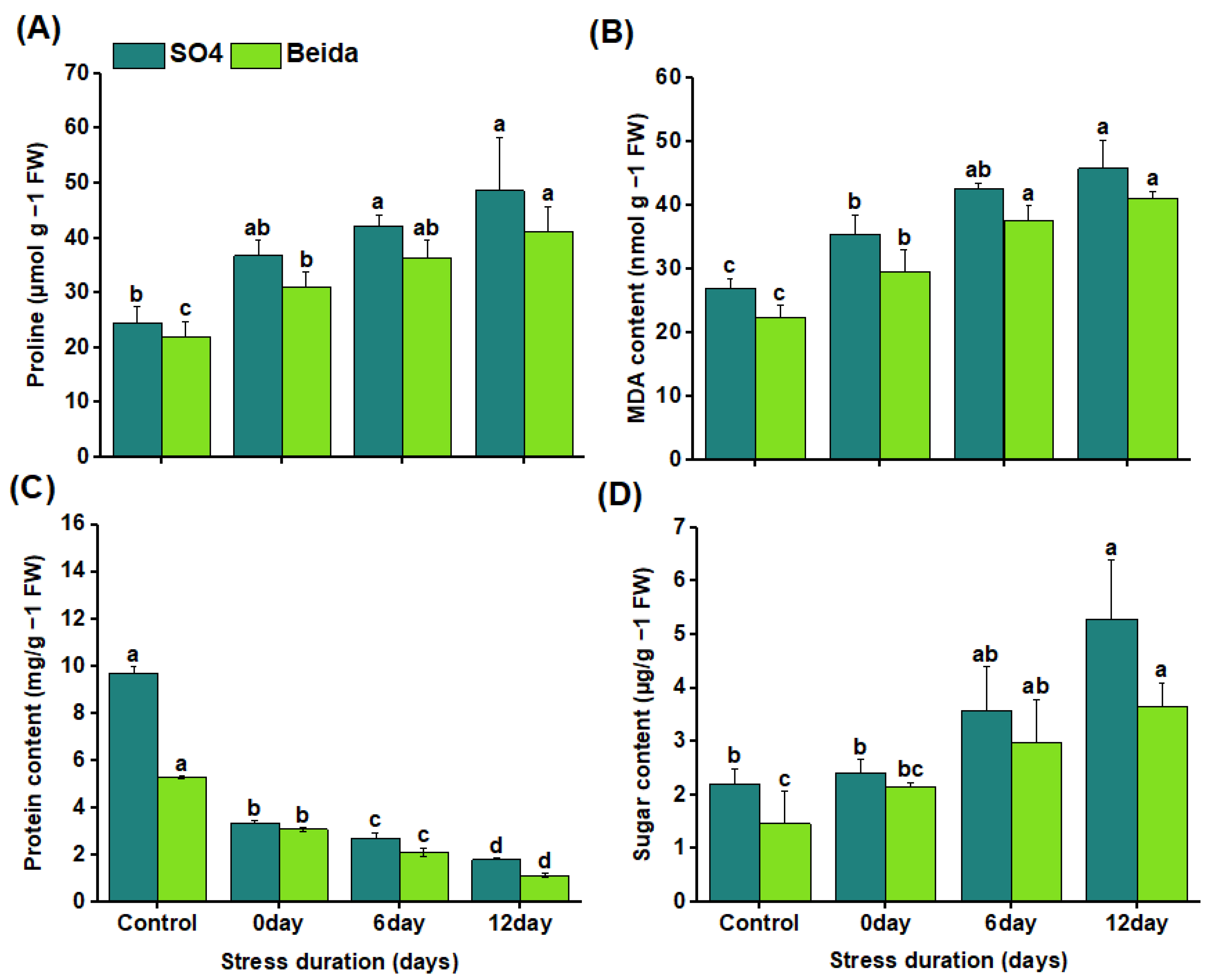

3.3. Effects of Salt Stress Treatments on Proline, Malondialdehyde, Protein, and Soluble Sugar Contents of Grapevine Rootstocks

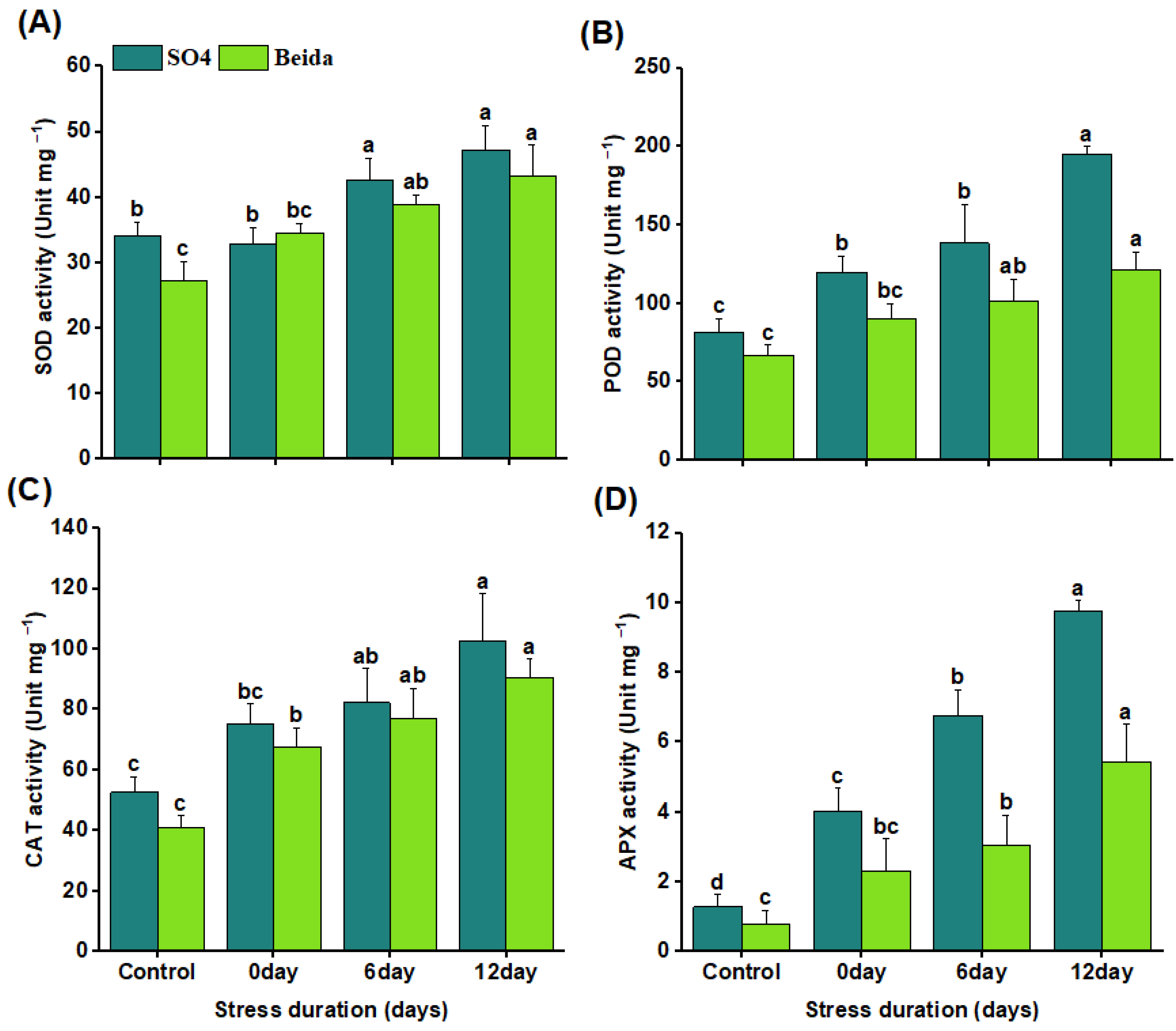

3.4. Effects of Salt Stress Treatments on Antioxidant Enzyme Activity on Grapevine Rootstocks

3.5. Morphological Indices, and Plant Growth Promotion Genes in Response to Salt Stress Treatment in the Grapevine Root

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed Potential Response Mechanims of Two Grapevine Rootstocks under Salt Stress

3.7. Principal Component Analysis and Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.8. Interpretation of the Coexpression by WGCNA Analysis and Identification of Module Involved in Two Grapevine Rootstocks Under Salt Stress

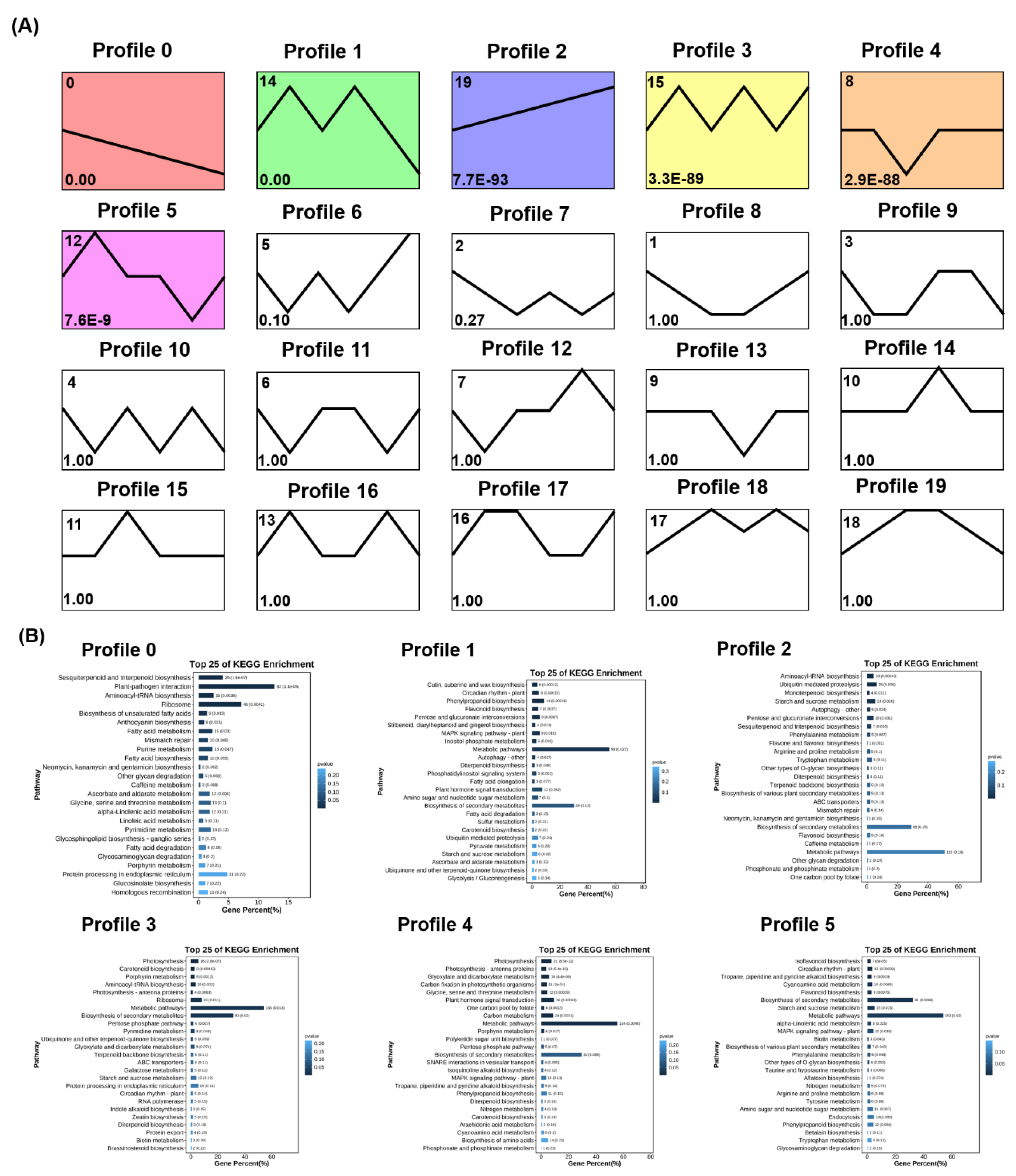

3.9. Expression Pattern of DEGs and Transcription Factors Families in Two Grapevine Rootstocks under Salt Stress

3.10. Transcription Factors in Grapevine Rootstocks under Salt Stress

3.11. Validation of RNA-Seq Data by RT-qPCR Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tripathy, S.K.; Nayak, G.; Naik, J.; Patnaik, M.; Dash, A.; Sahoo, D.; Prusti, A.M. Signal Transduction in Plants under Drought and Salt Stress-An Overview. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2019, 8, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Wang, S.; Qin, J.; Zhang, G.; Na, X.; Wang, X.; Bi, Y. Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic, and Metabolomic Analyses Revealed Molecular Mechanism for Salt Resistance in Soybean Roots. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zheng, T.; Liu, Z.; Fu, W.; Fang, J.J.P. Transcriptomic analysis elaborates the resistance mechanism of grapevine rootstocks against salt stress. 2022, 11, 1167.

- Rengasamy, P. World salinization with emphasis on Australia. Journal of experimental botany 2006, 57, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y.J.J.o.G.; Genomics. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. 2024, 51, 16-34.

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H.J.F.i.P.S. Plant salt response: Perception, signaling, and tolerance. 2023, 13, 1053699.

- Van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C.J.A.r.o.p.b. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. 2020, 71, 403-433.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V.J.A. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. 2020, 9, 681.

- Liang, W.; Ma, X.; Wan, P.; Liu, L.J.B.; communications, b.r. Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: A review. 2018, 495, 286-291.

- Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; Fang, X.; Ren, Y.; You, Z.; Xia, J.; Hakeem, A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fang, J.J.P.P. The physiology of drought stress in two grapevine cultivars: Photosynthesis, antioxidant system, and osmotic regulation responses. 2023, 175, e14005.

- Shan, C.; Liu, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.J.B.p. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on the redox states of ascorbate and glutathione in maize leaves under salt stress. 2014, 58, 169-173.

- Kaya, C.; Tuna, A.; Yokaş, I.J.S.; efficiency, w.s.i.c. The role of plant hormones in plants under salinity stress. 2009, 45-50.

- Zhang, M.; Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Niu, H.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Lv, G.; Yang, H.; Li, M. Melatonin and Indole-3-Acetic Acid Synergistically Regulate Plant Growth and Stress Resistance. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.J.I.J.o.M.S. Plant mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in environmental stresses. 2021, 22, 1543.

- Huang, X.-S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.-H.J.P.p. A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, PtrbHLH, of Poncirus trifoliata confers cold tolerance and modulates peroxidase-mediated scavenging of hydrogen peroxide. 2013, 162, 1178-1194.

- Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Niu, L.; Jameson, P.E.; Zhou, W.J.P.P. Transcription-associated metabolomic adjustments in maize occur during combined drought and cold stress. 2021, 186, 677-695.

- Prinsi, B.; Negri, A.S.; Failla, O.; Scienza, A.; Espen, L.J.B.p.b. Root proteomic and metabolic analyses reveal specific responses to drought stress in differently tolerant grapevine rootstocks. 2018, 18, 1-28.

- Xia, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Fang, X.; Hakeem, A.; Fang, J.; Shangguan, L.J.P.; Plants, M.B.o. VvATG6 contributes to copper stress tolerance by enhancing the antioxidant ability in transgenic grape calli. 2024, 30, 137-152.

- Hanana, M.; Hamrouni, L.; Hamed, K.; Abdelly, C.J.J.P.B.P. Influence of the rootstock/scion combination on the grapevines behavior under salt stress. 2015, 3, 1000154.

- Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Zheng, T.; Zhongjie, L.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pervaiz, T.; Shangguan, L.; Fang, J. Whole-genome re-sequencing, diversity analysis, and stress-resistance analysis of 77 grape rootstock genotypes. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viala, P.; Ravaz, L. American vines: their adaptation, culture, grafting and propagation; Government Printer, South Africa: 1901.

- Wang, F.-P.; Zhao, P.-P.; Zhang, L.; Zhai, H.; Du, Y.-P.J.H.R. Functional characterization of WRKY46 in grape and its putative role in the interaction between grape and phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae). 2019, 6.

- Ferris, H.; Zheng, L.; Walker, M.J.J.o.n. Resistance of grape rootstocks to plant-parasitic nematodes. 2012, 44, 377.

- Lowe, K.; Walker, M.J.T.; Genetics, A. Genetic linkage map of the interspecific grape rootstock cross Ramsey (Vitis champinii)× Riparia Gloire (Vitis riparia). 2006, 112, 1582-1592.

- Reisch, B.I.; Owens, C.L.; Cousins, P.S.J.F.b. Grape. 2012, 225-262.

- Riaz, S.; Pap, D.; Uretsky, J.; Laucou, V.; Boursiquot, J.-M.; Kocsis, L.; Andrew Walker, M.J.T.; Genetics, A. Genetic diversity and parentage analysis of grape rootstocks. 2019, 132, 1847-1860.

- Jellouli, N.; Jouira, H.B.; Skouri, H.; Ghorbel, A.; Gourgouri, A.; Mliki, A.J.J.o.p.p. Proteomic analysis of Tunisian grapevine cultivar Razegui under salt stress. 2008, 165, 471-481.

- Tillett, R.L.; Ergül, A.; Albion, R.L.; Schlauch, K.A.; Cramer, G.R.; Cushman, J.C.J.B.p.b. Identification of tissue-specific, abiotic stress-responsive gene expression patterns in wine grape (Vitis viniferaL.) based on curation and mining of large-scale EST data sets. 2011, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y.J.P. Ectopic expression of VpALDH2B4, a novel aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Chinese wild grapevine (Vitis pseudoreticulata), enhances resistance to mildew pathogens and salt stress in Arabidopsis. 2012, 236, 525-539.

- Zhao, F.; Zheng, T.; Zhongjie, L.; Fu, W.; Fang, J. Transcriptomic Analysis Elaborates the Resistance Mechanism of Grapevine Rootstocks against Salt Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Singh, S.; Patel, V.; Bhattacharya, R.; Yadav, B.J.B.P. In vitro responses of grape rootstocks to NaCl. 2010, 54, 381-385.

- Suarez, D.L.; Celis, N.; Anderson, R.G.; Sandhu, D.J.A. Grape rootstock response to salinity, water and combined salinity and water stresses. 2019, 9, 321.

- Walker, R.R.; Blackmore, D.H.; Clingeleffer, P.R.; Tarr, C.J.A.j.o.g.; research, w. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana). 3. Fresh fruit composition and dried grape quality. 2007, 13, 130-141.

- WALKER, R.R.; BLACKMORE, D.H.; CLINGELEFFER, P.R.; CORRELL, R.L.J.A.J.o.G.; Research, W. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana) 2. Ion concentrations in leaves and juice. 2004, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WALKER, R.R.; BLACKMORE, D.H.; CLINGELEFFER, P.R.; CORRELL, R.L.J.A.J.o.G.; Research, W. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana).: 1. Yield and vigour inter-relationships. 2002, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Bhirangi, R.J.B.p. Expression of Na+/H+ antiporter gene in response to water and salinity stress in grapevine rootstocks. 2012, 56, 762-766.

- Mehanna, H.; Fayed, T.; Rashedy, A.J.J.H.S.; Plants, O. Response of two grapevine rootstocks to some salt tolerance treatments under saline water conditions. 2010, 2, 93-106.

- Wooldridge, J.; Olivier, M.J.S.A.J.o.E.; Viticulture. Effects of weathered soil parent materials on Merlot grapevines grafted onto 110 Richter and 101-14Mgt rootstocks. 2014, 35, 59-67.

- Gan, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Okita, T.; Yan, Y.; Tian, L. RNA-seq analysis reveals transcriptome reprogramming and alternative splicing during early response to salt stress in tomato root. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Mo, J.; Zhou, H.; Shen, X.; Xie, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, S. Comparative transcriptome analysis of gene responses of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive rice cultivars to salt stress. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.L.; Li, M.; Zhou, 周.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, J. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into the stress response crosstalk in apple (Malus × domestica) subjected to drought, cold and high salinity. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Chen, C.; Fu, L.; Chen, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ provides insights into the crucial factors and signaling pathways in salt stress response. Agronomy Journal 2021, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; gu, M.; Yuan, Z. Transcriptomic Profiling of Pomegranate Provides Insights into Salt Tolerance. Agronomy 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefirad, S.; Soltanloo, H.; Ramezanpour, S.; Nezhad, K.; Shariati, V. The RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis reveals genes mediating salt tolerance through rapid triggering of ion transporters in a mutant barley. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Muhammad Salman, H.; Khan, N.; Nasim, M.; Jiu, S.; Fiaz, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, K.; Fang, J. Transcriptome Sequence Analysis Elaborates a Complex Defensive Mechanism of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) in Response to Salt Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, W.; Jaskani, M.J.; Maqbool, R.; Khan, A.S.; Ali, Z.J.I.J.A.B. Evaluation of citrus rootstocks against drought, heat and their combined stress based on growth and photosynthetic pigments. 2019, 22, 1001-1009.

- Du, Z.; Bramlage, W. Modified thiobarbituric acid assay for measuring lipid oxidation in sugar-rich plant tissue extracts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry - J AGR FOOD CHEM 1992, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution *. Journal of Plant Physiology 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzi, C.; Flores, É.; Nóbrega, J.; Souza da Silva, J.; Schmidt, L.; Mortari, S. Evaluation of a digestion procedure based on the use of diluted nitric acid solutions and H2O2 for the multielement determination of whole milk powder and bovine liver by ICP-based techniques. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2014, 29, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.; Ries, S. Superoxide Dismutases: I. Occurrence in Higher Plants. Plant physiology 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.-R.; Zhang, G.P.; Zhou, M.; Wu, F.; Chen, J. Effects of aluminum and cadmium toxicity on growth and antioxidant enzyme activities of two barley genotypes with different Al resistance. Plant and Soil 2004, 258, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durner, J.; Klessig, D. Salicylic Acid Is a Modulator of Tobacco and Mammalian Catalases. The Journal of biological chemistry 1996, 271, 28492–28501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Jiang, Y. Waterlogging Tolerance of Kentucky Bluegrass Cultivars. HortScience 2007, 42, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Zhang, P.; Hakeem, A.; Liu, Z.; Su, L.; Ren, Y.; Pei, D.; Xuan, X.; Li, S.; Fang, J.J.E.; et al. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals the physiological and molecular mechanisms of grape seedlings in response to red, green, blue, and white LED light qualities. 2023, 213, 105441.

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.J.B. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. 2010, 26, 136-138.

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.J.N.a.r. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. 2000, 28, 27-30.

- Langfelder, P.; Wgcna, S.H.J.D.h.d.o.-.-.-. An R package for weighted correlation network analysis., 2008, 9, 559.

- Ge, M.; Sadeghnezhad, E.; Hakeem, A.; Zhong, R.; Wang, P.; Shangguan, L.; Fang, J.J.S.H. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolic analyses unveil anthocyanins biosynthesis metabolism in three different color cultivars of grape (Vitis vinifera l.). 2022, 305, 111418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Hao, T.; Hakeem, A.; Ren, Y.; Fang, J.J.F.C. Synergistic variation in abscisic acid and brassinolide treatment signaling component alleviates fruit quality of ‘Shine Muscat’grape during cold storage. 2024, 141584.

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D.J.m. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. 2001, 25, 402-408.

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R.J.M.p. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. 2020, 13, 1194-1202.

- Gan, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Okita, T.W.; Yan, Y.; Tian, L.J.F.i.P.S. RNA-seq analysis reveals transcriptome reprogramming and alternative splicing during early response to salt stress in tomato root. 2024, 15, 1394223.

- Soltabayeva, A.; Ongaltay, A.; Omondi, J.O.; Srivastava, S.J.P. Morphological, physiological and molecular markers for salt-stressed plants. 2021, 10, 243.

- Alshiekheid, M.A.; Dwiningsih, Y.; Alkahtani, J. Analysis of morphological, physiological, and biochemical traits of salt stress tolerance in Asian rice cultivars at different stages. 2023.

- Shin, Y.K.; Bhandari, S.R.; Jo, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Cho, M.C.; Yang, E.Y.; Lee, J.G.J.A. Response to salt stress in lettuce: Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activities. 2020, 10, 1627.

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Root dynamic growth strategies in response to salinity. Plant, Cell & Environment 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel Henschel, J.; Dias, T.; de Moura, V.; Silva, A.; Lopes, A.; da Silva Gomes, D.; Araujo, D.; Silva, J.; Cruz, O.; Batista, D. Hydrogen peroxide and salt stress in radish: effects on growth, physiology, and root quality. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalazez, F.; El-Gazzar, A.; Mansour, N.; Samaan, M. Biochemical and Physiological Responses of Some Grape Rootstocks to Salt Stress. Egyptian Journal of Horticulture 2023, 51, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandonnet, J.-P.; Cookson, S.; Vivin, P.; Ollat, N. Scion genotype biomass allocation and root development in grafted grapevine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2010, 16, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.; Shahid, R.; Ren, M.-X.; Altaf, M.; Khan, L.; Shahid, S.; Shah Jahan, M. Melatonin alleviates salt damage in tomato seedling: A root architecture system, photosynthetic capacity, ion homeostasis, and antioxidant enzymes analysis. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 285, 110145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Saleem, M.; Fariduddin, Q. Melatonin Influences Stomatal Behavior, Root Morphology, Cell Viability, Photosynthetic Responses, Fruit Yield, and Fruit Quality of Tomato Plants Exposed to Salt Stress. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2022, 42, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- yıldırım, K.; Yağci, A.; Sucu, S.; Tunç, S. Responses of grapevine rootstocks to drought through altered root system architecture and root transcriptomic regulations. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Salman, H.; Jogaiah, S.; Pervaiz, T.; Zhao, Y.; Khan, N.; Fang, J. Physiological and Transcriptional Variations Inducing Complex Adaptive Mechanisms in Grapevine by Salt Stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, L.; Wang, B.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Grapevine Rootstock in Response to Waterlogging Stress. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 749184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lu, R.; Dai, Z.; Yan, A.; Tang, Q.; Cheng, C.; Xu, Y.; Yang, W.; Su, J.J.G. Salt-stress response mechanisms using de novo transcriptome sequencing of salt-tolerant and sensitive Corchorus spp. genotypes. 2017, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracasso, A.; Trindade, L.M.; Amaducci, S.J.B.P.B. Drought stress tolerance strategies revealed by RNA-Seq in two sorghum genotypes with contrasting WUE. 2016, 16, 1-18.

- Muthusamy, M.; Uma, S.; Backiyarani, S.; Saraswathi, M.S.; Chandrasekar, A.J.F.i.p.s. Transcriptomic changes of drought-tolerant and sensitive banana cultivars exposed to drought stress. 2016, 7, 1609.

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, G.; Du, L.; Shang, X.; Cheng, C.; Yang, B.; Hu, Y.; Cai, C.; Guo, W.J.S.r. Genetic regulation of salt stress tolerance revealed by RNA-Seq in cotton diploid wild species, Gossypium davidsonii. 2016, 6, 20582.

- Dalal, M.; Inupakutika, M.J.M.b. Transcriptional regulation of ABA core signaling component genes in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench). 2014, 34, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojosnegros, S.; Alvarez, J.M.; Grossmann, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Quintanilla, L.G.; Grossniklaus, U.; Fernández, H.J.I.J.o.M.S. Proteome and interactome linked to metabolism, genetic information processing, and abiotic stress in gametophytes of two woodferns. 2023, 24, 12429.

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Ma, H.; Zhao, C.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Jin, M. Comparative transcriptome and coexpression network analysis revealed the regulatory mechanism of Astragalus cicer L. in response to salt stress. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, A. Abiotic Stress Tolerance Boosted by Genetic Diversity in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Li, W. Gene-coexpression network analysis identifies specific modules and hub genes related to cold stress in rice. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Cao, W.; Fang, H.; Xu, S.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.J.F.i.p.s. Transcriptomic profiling of the maize (Zea mays L.) leaf response to abiotic stresses at the seedling stage. 2017, 8, 290.

- Song, X.; Duan, Y.-Y.; Tan, F.-Q.; Ren, J.; Cao, H.-X.; Xie, K.-D.; Wu, X.-M.; Guo, W.-W.J.S.H. Comparative transcriptome analysis of salt tolerance of roots in diploid and autotetraploid citrus rootstock (C. junos cv. Ziyang xiangcheng) and identification of salt tolerance-related genes. 2023, 317, 112083. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Q.; Asim, M.; Zhang, R.; Khan, R.; Farooq, S.; Wu, J.J.B. Transcription factors interact with ABA through gene expression and signaling pathways to mitigate drought and salinity stress. 2021, 11, 1159.

- Joshi, R.; Wani, S.H.; Singh, B.; Bohra, A.; Dar, Z.A.; Lone, A.A.; Pareek, A.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.J.F.i.p.s. Transcription factors and plants response to drought stress: current understanding and future directions. 2016, 7, 1029.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).