1. Introduction

In recent years,, heavy metal elements have accumulated in soil, water and the atmosphere, seriously affecting the cultivation and safe production of crops. Cadmium (Cd), as one of the main heavy metal elements in soil pollution, has the characteristics of wide range, wide distribution, non-degradability, strong toxicity, extremely strong mobility, easy absorption and accumulation by plants, and can also disrupt plant metabolism and damage plant growth [

1]. When the Cd absorbed by plants accumulates beyond the safety threshold of the plants themselves, it will cause varying degrees of toxic effects on plants at the morphological, physiological and molecular levels [

2]. The Cd toxicity response in plants is mainly manifested as inhibited growth, damaged root systems, curled and yellowed leaves, and even leaf drop [

2]. After excessive accumulation of Cd in plants, it induces the production of a large number of reactive oxygen species, causing lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, degradation of chloroplasts, and severe damage to the photosynthetic reaction center of plants, and seriously inhibits the growth and development of plants [

3]. Therefore, plants must quickly take a series of protective measures, mainly by enhancing the activity of the antioxidant enzyme system and promoting the production of osmotic adjustment substances, to ensure the rapid removal of accumulated reactive oxygen species in cells. Study has shown that Cd markedly increases the level of ROS in tomato. The plants enhance antioxidant enzymes’ activity to alleviate Cd phytotoxicity in tomato [

4].

Plant hormones (such as auxin, gibberellin, cytokinin, abscisic acid, ethylene, etc.) are trace organic substances synthesized within plants, which can regulate growth and development as well as adapt to environmental changes. They can influence plant life activities through either synergistic or antagonistic effects [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Studies have shown that plant hormones can assist in integrating endogenous and exogenous signals, helping plants cope with abiotic stresses, such as Cd stress [

10,

11,

12]. Gibberellins, abscisic acid, auxin, jasmonic acid, cytokinins, ethylene, salicylic acid, brassinosteroids, and polyamines have gained attention by botanical researchers as a sustainable phytohormones to induce tolerance in Cd stressed plants [

13]. 4-Benzoylphenylboronic acid (PPBa) is a specific and effective inhibitor of flavin monooxygenase (YUCCA) enzymes, which can inhibit the synthesis of IAA [

14]. The YUCCA plays a vital role in the synthesis pathway of IPA. If the activity of this enzyme is inhibited, it will affect the secretion of IAA, thereby regulating the accumulation of Cd [

15]. Physiologically, Cd affects the normal growth of plants by mainly inhibiting photosynthesis, influencing antioxidant enzymesand protein synthesis enzymes activities, regulating the synthesis and transportation of phytohormone in plants [

13]. At the molecular level, Cd stress also induces the expression of a series of genes, such as genes for plant chelators, genes for heavy metal ATPases, genes for YSL transport proteins, genes for ABC transport proteins, genes for antioxidant system activity and oxidative stress response, genes for chlorophyll synthesis or degradation [

13].

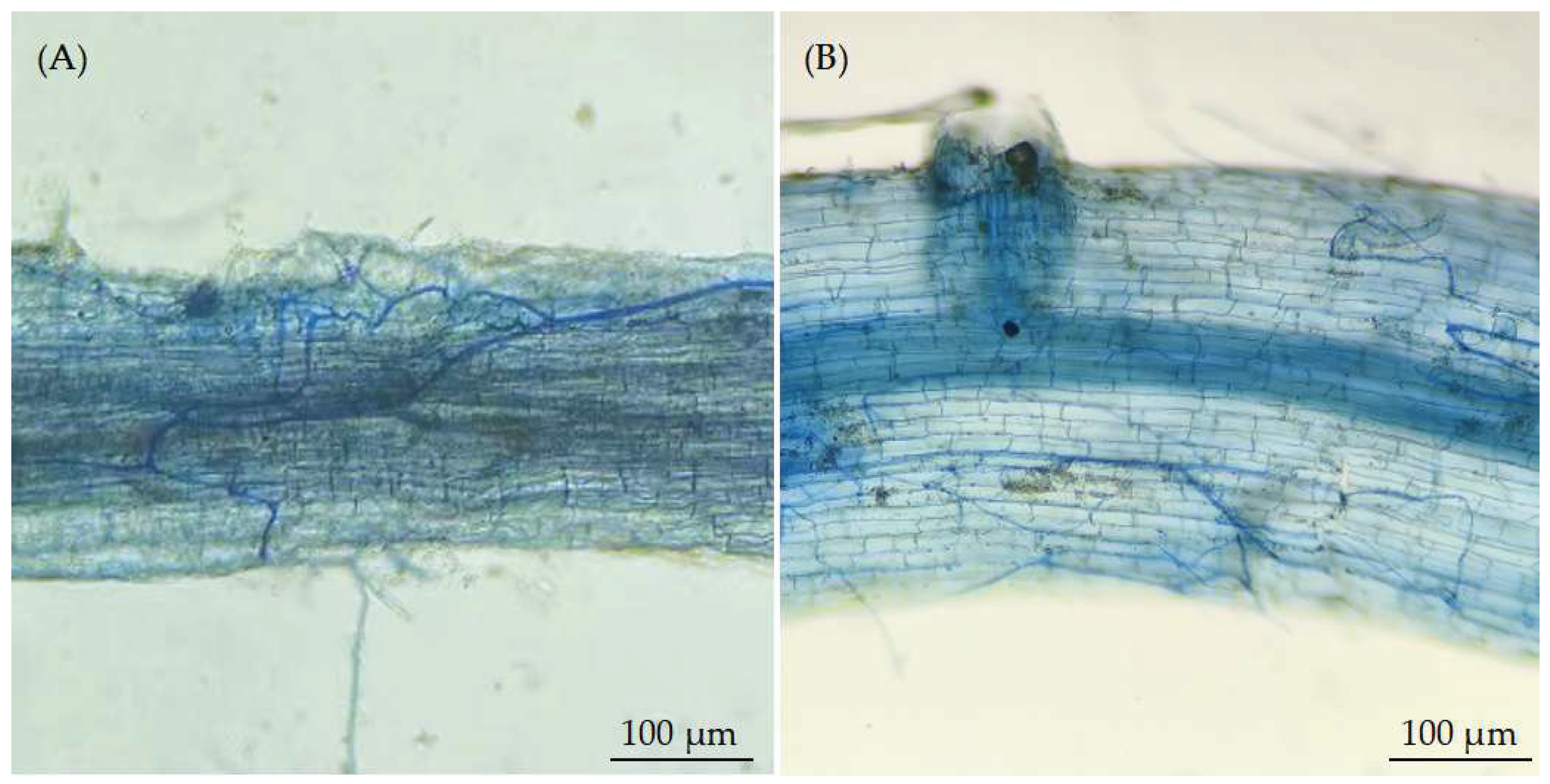

As a type of symbiotic fungus, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) widely present in the soil, capable of forming symbiotic relationships with most terrestrial plants [

16]. Under heavy metal stress, AMF can infect plant roots to form mycorrhizal symbioses. In particular, the AMF exogenous hyphal network can enhance the plant’s absorption of mineral nutrients, and alleviate the negative effects from heavy metal to plant growth [

17,

18]. Hristozkova et al. [

19] have demonstrated that AMF alleviated the toxic of heavy metals (Cd and Pb) by promoting the nutrient absorption and secondary metabolite accumulation of

Calendula officinalis. AMF (

Rhizophagus irregularis) inoculation lowered Cd influx in in Perennial Ryegrass (

Lolium perenne L.), enhanced the availability of nutrients in the rhizosphere, and mitigated Cd phytotoxicity [

20]. AMF also causes changes in the root exudates of plants. For instance, low-molecular organic acids can form “heavy metal-low molecular organic acid” complexes with soil heavy metals, thereby reducing the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals and alleviating heavy metals’ phytotoxicity [

21]. The influence process of low-molecular organic acids on the availability of heavy metals is relatively complex. It is not only related to the types and properties of organic acids themselves, but also to factors such as soil conditions and planting patterns [

22]. Under Cd stress, AMF affected the secretion amounts of different types of low-molecular organic acids, thereby causing changes in the forms of heavy metals [

23]. The root systems of plants can alter the redox potential and pH in soil by secreting low-molecular organic acids (such as malic acid and citric acid), reducing the solubility and mobility of heavy metal elements, thereby alleviating the growth conditions of plants under heavy metal stress [

23]. Therefore, after AMF establishes a symbiotic relationship with plants, it can improve the morphology of the roots. At the same time, it affects the low-molecular organic acids secreted by the roots, thereby facilitating the host plants’ absorption of nutrient elements, inhibiting heavy metals’ mobility, and regulating the transport process of heavy metals in the host plants through the mycorrhizal structure and the complex mycelial network. As a result, it reduces the heavy metals’ phytotoxicity on the host plants, promotes the growth of the host plants, and helps them resist non-biological adverse conditions such as heavy metal stress [

17,

18,

24].

As an annual or perennial herbaceous plant of the Solanaceae family, tomatoes (

Solanum lycopersicum) are rich in lycopene, vitamins and polyphenolic compounds, and are one of the widely cultivated fruits and vegetables worldwide. Non-biological stress mainly refers to adverse conditions caused by environmental factors, which include not only temperature stress, light stress, drought stress, and salt stress, but also various heavy metal stress, such as Pb and Cd stress [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Currently, most studies on non-biological stress in tomatoes focus on the effects of salt stress, drought stress, and high-temperature stress on tomatoes. However, existing studies have shown that tomatoes are sensitive to Cd. Moreover, the problem of Cd pollution is becoming increasingly severe, which not only reduces the yield and quality of vegetables such as tomatoes, but also poses a threat to human health [

4]. A considerable amount of research has focused on the response mechanisms of vegetables such as cucumber, lettuce, and pepper under Cd stress. However, few studies focus on the mechanism of tomato’s tolerance to Cd stress from the perspective of microorganisms (such as AMF). Therefore, it is of certain significance to study the growth and physiological and biochemical changes of tomato under Cd condition from the perspective of AMF. This study used tomato (

Ailsa Craig) as the material and applied AMF (

Diversispora versiformis) and CdSO

4 to interactively treat tomato seedlings. It explored the growth and physiological-biochemical responses of tomato plants to AMF and CdSO

4, and further analyzed the mechanism by which AMF enhances tomato’s tolerance to Cd stress. This study provides a theoretical basis for using microorganisms to remediate heavy metal-contaminated soil and improving plant stress resistance.

4. Discussion

The phytotoxicity of Cd refer to photosynthesis, growth, secondary metabolism, oxidative stress responses, and so on [

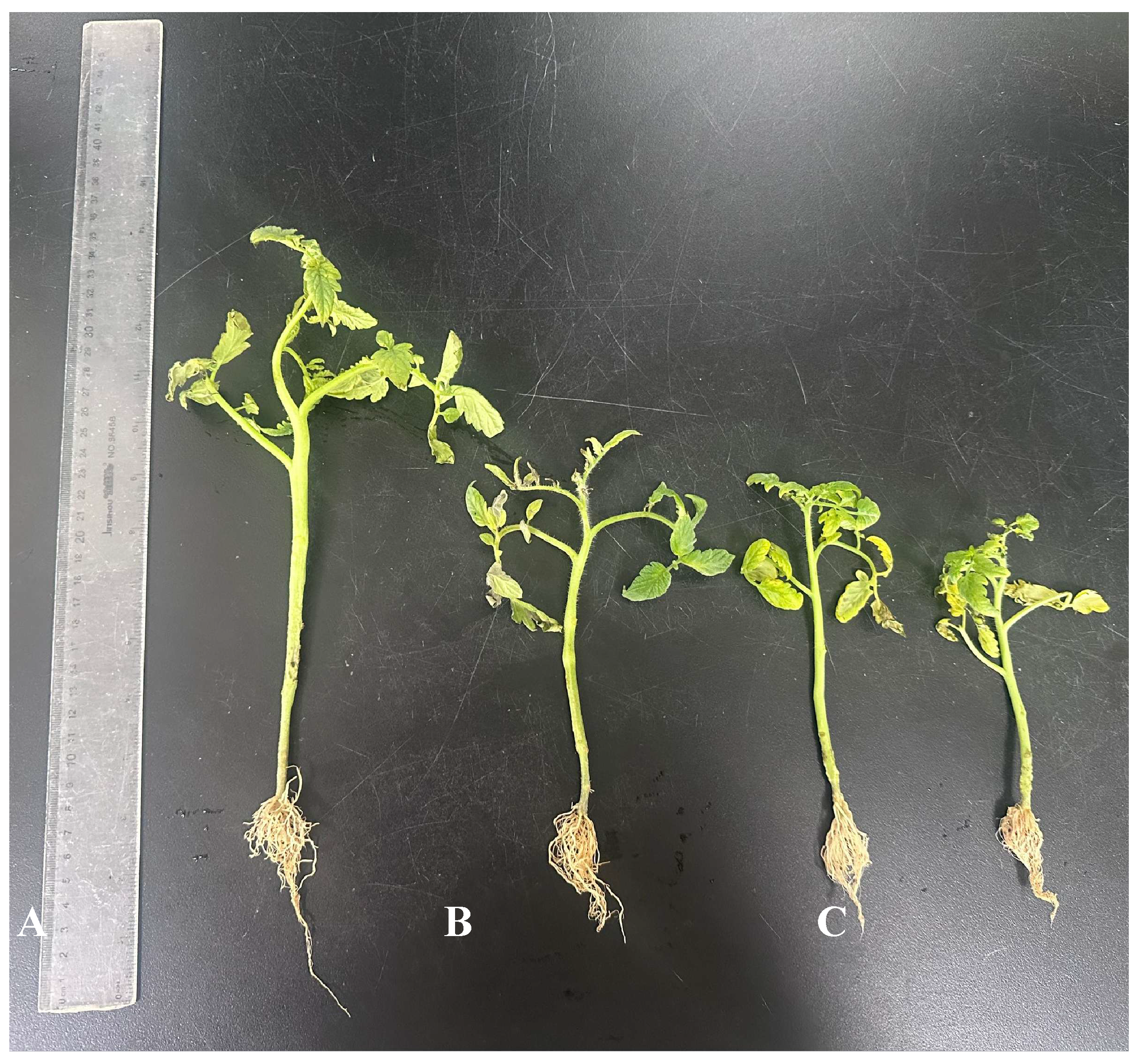

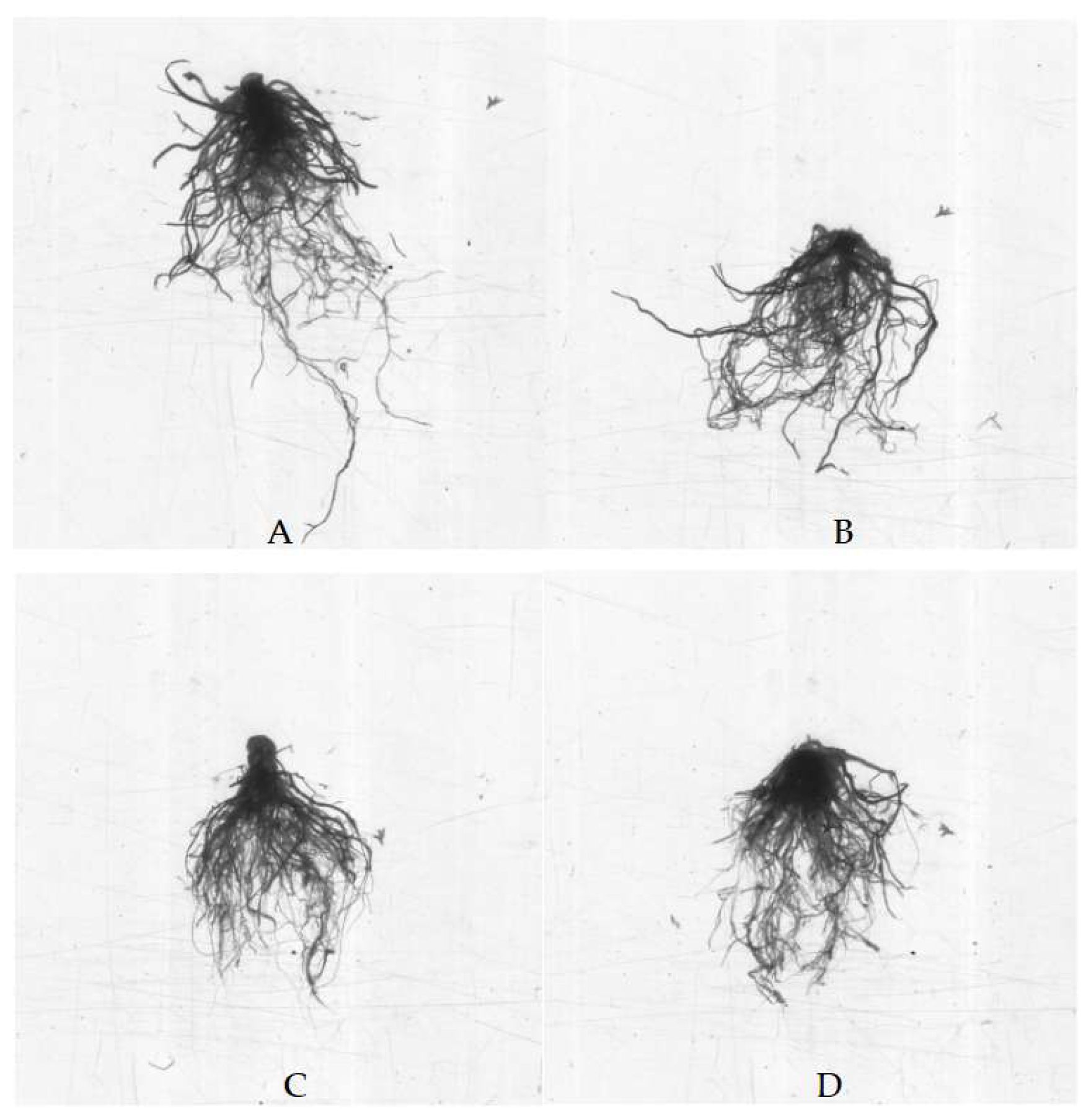

18]. The morphological indicators of plants include total plant weight, leaf number, plant height, fresh weight of root system, fresh weight of aboveground part, total root length, and total root surface area, etc., which can reflect the response of the plants to Cd toxicity [

30]. Yang et al. [

20]used

Lolium perenne L. as the material to study the impact of 100 mg/kg Cd stress on its growth and found that Ca significantly inhibited the growth indicators such as leaf fresh weight and root fresh weight. 400 mg·kg

−1 Cd severely reduced the growth indicators of

Rosa rugosa, and also caused chlorosis and leaf desiccation [

34]. In this study, the growth of the aboveground parts and roots of tomato plants treated with 50 μmol/L Cd was significantly inhibited. At the same time, phenomena such as leaf wilting, edge curling, darkening of color, chlorosis, slow addition of new leaves, and shedding of old leaves occurred. The study suggests that Cd competes with mineral nutrients for the same transport pathways, thereby altering the absorption and distribution of mineral nutrients in plants, resulting in nutrient deficiency in the plants and inhibition of plant growth [

35].

AMF is an important functional microorganism widely present in the soil. After AMF infects plants and forms a mycorrhizal symbiotic structure, it can improve the host plants nutrients and water absorption, thereby promoting the growth of the host plants and enhancing their stress resistance [

26,

36]. In this study, AMF significantly enhanced tomato growth. Especially under Cd stress conditions, AMF had a better recovery effect on the growth potential of tomato seedlings. This is similar to Yang et al. [

20] in their study on AMF under Cd stress on Perennial Ryegrass (

Lolium perenne L.) that AMF reduced Cd influx in plants, enhanced nutrient availability, and then mitigated Cd phytotoxicity. This is also consistent with the research results of Zhuang et al. [

12]: AMF (

Rhizophagus intraradices) can effectively alleviate the negative effects of Cd stress (300 μM) on the growth characteristics and nutrient element content of

Malus hupehensis Rehd. Furthermore, the results of this study also indicate that after AMF inoculation, the Cd content in the root systems of tomato seedlings under Cd stress conditions decreased significantly from 19.32 mg/kg to 11.54 mg/kg. This is consistent with the results of previous studies. AMF dramatically reduced Cd level in the root and shoot, which weaken the phytotoxicity of excessive Cd in the maize (

Zea mays L.) [

37]. AMF significantly increased the maize height and biomas and decreased the available Cd content in soil and maize [

38]. Mycorrhization (

Rhizophagus intraradices) could avoid Cd-induced growth inhibition and reduce Cd accumulation in roots of

Glycine max (L.) Merr [

39]. AMF (

D. eburnea) markedly altered soil Cd speciation by increasing the proportion of exchangeable Cd and decreasing residual Cd, resulting in Cd change in the root of

L. perenne and

A. fruticosa [

40]. AMF inoculation reduced the Cd level in

P. yunnanensis [

41].

The toxic effects of heavy metals also manifest in the destruction of the chloroplast structure in plant leaves. Chloroplasts are the crucial sites for photosynthesis in plants, and chlorophyll, as an important photosynthetic pigment, plays a decisive role in the accumulation of plant biomass [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Li et al. [

17] subjected

Medicago truncatula to Cd Stress (20 mg/g), they found that the chlorophyll content in the leaves significantly decreased. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll levels in ‘Baizizhi’ and ‘Zizhi’ decreased with increasing Cd contents [

34]. The chlorophyll pigments were significantly reduced in 100 mg/kg Cd-contaminated

Brassica chinensis L. seedlings, when compared to non-Cd treatment [

42]. The damage of Cd to chloroplasts and thylakoid membranes occurs concurrently with the activities of enzymes involved in chlorophyll synthesis, and it will activate enzymes related to chlorophyll degradation and ROS production, then lead to a decrease in chlorophyll synthesis and content [

46]. In this study, Cd dramatically lowered chlorophyll b, chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll concentrations in tomato seedlings leaves, indicating that Cd stress would damage the chlorophyll in tomato seedlings and inhibit the synthesis of chlorophyll. It is notable that AMF significantly increased chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and total chlorophyll levels in tomato seedlings. Especially under Cd stress conditions, AMF had a better recovery effect on chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and total chlorophyll levels in tomato seedlings. This is similar to the research results of Wang et al. [

47] on AMF’s effect on tomato under Cd stress: after AMF inoculation, the agronomic traits of tomato significantly improved in moderately Cd contaminated soil, specifically manifested as increased plant height, stem diameter, and chlorophyll content. Therefore, Cd stress significantly inhibited the synthesis of chlorophyll, while AMF could effectively alleviate the Cd phytotoxicity on the chlorophyll synthesis in tomato.

When plants are subjected to heavy metal stress during their growth process, the inner membrane of the chloroplasts will be damaged, which affects the photosynthesis and the production of assimilates in the plants [

12,

48]. In PSII, when plants are subjected to abiotic stress, the ratio Fv’/Fm’ decreases, indicating that the photosystem II has been damaged [

49]. Under Cd stress (20 mg/Kg), chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (φPSII and qP) of Medicago truncatula Gaertn decreased significantly, which indicates that Cd

2+ stress damaged the photosynthetic organ [

17]. Shaari et al. [

42] study found that 100 mg/kg Cd presented the lowest Fv’/Fm’ ratio (0.73), indicating the

Brassica chinensis L. seedlings were stressed as compared to control. This study found that Cd stress significantly reduced φPSII, Fv’/Fm’ and qP in the leaves of tomato seedlings. However, after inoculation with AMF, these indicators returned to normal levels. This is consistent with the results of other studies. In response to Cd stress (300 μM), Fv’/Fm’ was signiffcantly increased in mycorrhizal (

R. intraradices) compared to non-mycorrhizal

M. hupehensis Rehd seedlings [

12]. Under Cd stress conditions (20 mg/kg), after inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (φPSII and NPQ) of alfalfa (

Medicago truncatula) were significantly improved, effectively alleviating the damage to the PSII reaction center caused by Cd stress [

17]. This indicates that AMF can alleviate and even restore the damage to PSII caused by Cd stress. Under Cd condition, AMF (

R. irregularis) observably increase Fv’/Fm’, φPSII, and qP in

Eucalyptus grandis [

48]. The above results indicate that Cd stress weakens the efficiency of light energy utilization by reducing the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. However, AMF can effectively alleviate the reduction effect of Cd stress on the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, thereby improving the adverse effects of Cd on the PSII reaction center and enhancing the light energy utilization efficiency.

Photosynthesis is the process by which plants synthesize compounds rich in energy. It is the ultimate carbon synthesis pathway in various biochemical and physiological processes of plants, and it forms the basis of plant life activities [

50]. Photosynthesis is highly sensitive to many adverse environmental conditions, including water stress, high temperature, salt damage, and heavy metal stress [

18,

51]. All these stresses will reduce the photosynthetic efficiency of plants and thereby affect growth and development. The parameters of photosynthetic intensity could precisely reflect the photosynthetic intensity in plants. As the degree of Cd stress increases, the Pn, Tr and Gs of Rosa rugosa leaves show a gradually decreasing trend [

34]. This is in agreement to this study: Cd acts as an effective inhibitor of photosynthesis, suppressing plant photosynthesis through stomatal closure, damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, and destruction of the light-harvesting complexes and photosystems I and II [

52]. There have been some reports on the effect of AMF vaccination in alleviating the negative impact of Cd stress on plant photosynthesis. AMF could mitigate Cd induced photosynthesis and growth phytotoxicity and nutrient ion disorders in

Malus hupehensis Rehd [

12]. AMF mediated mitigation of Cd phytotoxicity and their influence on photosynthesis efficiency in

Cicer arietinum [

53]. These results are consistent with those of this study: Under the condition of no AMF inoculation, Cd dramatically lowered the values of Pn, Gs, Ci and Tr. However, after AMF inoculation, these indicators returned to levels close to those without Cd stress. Therefore, Cd has a certain inhibitory effect on the photosynthetic intensity and efficiency of plants. However, AMF effectively alleviate the negative effects of Cd on photosynthesis, thereby increasing photosynthetic products and alleviating the damage caused by Cd to plants.

During normal physical metabolism, plants produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, the generation and clearance of ROS are in a dynamic equilibrium. Once plants are subjected to adverse stress, this dynamic equilibrium is disrupted, leading to the accumulation of ROS, which causes membrane lipid peroxidation, damaging the cell membrane structure and causing damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [

54,

55]. During the evolution of plants, there is a set of protective enzyme systems within the plant cells that prevent ROS from causing damage to the cells, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione reductase (GR), etc [

54]. Dixit et al. [

56] research indicates that Cd stress increases the activity of lipoxygenase and NADPH oxidase, thereby causing a significant accumulation of ROS (such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion radicals), which subsequently leads to membrane lipid peroxidation in plants, resulting in the disruption of the cell membrane system, cell damage, and electrolyte leakage. Cd treatment caused a significant increase in H

2O

2 contents and trigger membrane lipid peroxidation in Perennial Ryegrass (

Lolium perenne L.) [

20]. The results of this study also indicate that Cd stress triggered an outbreak of ROS in tomato roots, causing damage to the cell membranes and the outflow of cytoplasm, and subsequently leading to membrane lipid peroxidation. This study also found through inoculation with AMF that it significantly increased antioxidant enzymes activities (POD, SOD, CAT, etc.) to reduce ROS level (such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion radicals, etc.), thereby alleviating the damage caused by Cd stress to tomato seedlings. AMF alleviated Cd phytotoxicity mainly by promoting immobilization and sequestration of Cd, reducing ROS production and accelerating their scavenging in wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) [

57]. AMF improved ROS scavenging efficiency (by enhanced the activity of POD and CAT) and alleviated oxidative stress in Perennial Ryegrass (

Lolium perenne L.), thereby mitigating Cd poisoning [

20]. These research are in agreement with our study that Cd induce the production of excessive ROS in plants. However, AMF could availably enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants under Cd conditions, improve their antioxidant defense ability to reduce the content of ROS, maintain the redox balance within the cells, protect cell membrane’ function and structure, strengthen the antioxidant capacity, and mitigate Cd phytotoxicity to the cell membrane. AMF penetration and colonization involve a series of cytological and biochemical sequence of events and intracellular changes, including anti-oxidative damaging effect and ROS promotion [

58]. At early stages of AMF-plant interaction, the mechanism of suppression or induction associated with plant defense hold the key to AMF and the plant-fungus compatibility in the context of this mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship [

39,

59]. These physiological processes include changes in the activation of plasma membrane-bound enzymes and of kinases, phosphatases, phospholipases, the permeability of the plasma membrane, and production of signal molecules, including ROS. Regarding Cd stresses, our study in conjunction with previous studies jointly demonstrated that AMF is also involved in defense processes and mechanisms, potentially with effects on the induction of abiotic stress tolerance [

59].

Under heavy metal stress conditions, plants will produce a large amount of osmotic regulatory substances. These osmotic regulatory substances not only maintain the cell turgor pressure and prevent excessive water loss of the protoplasm, but also stabilize the structure of organelles, thereby regulating certain physiological functions and alleviating the damage caused by heavy metal stress to plants [

60]. Proline (Pro), malondialdehyde (MDA), soluble proteins, soluble sugars, etc. are all osmotic regulatory substances in plants [

60]. The content of MDA was significantly increased 2.5-fold under Cd

2+ stress in

M. truncatula, indicating that Cd

2+ significantly caused the oxidative damage of cell membrane [

17]. It is consistent with the conclusion of this study: Cd stress increased the content of osmotic regulatory substances (Pro, MDA, Soluble protein, and Soluble sugar) in the root systems of tomato seedlings. The increase in the concentration of these osmotic regulatory substances is an adaptive response of tomatoes under heavy metal Cd stress. It reduces lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane, alleviates membrane damage, and provides protection for tomatoes. This study also found through inoculation with AMF that it could significantly reduce the accumulation of these osmotic regulatory substances in the root systems of tomatoes, thereby alleviating the damage caused by Cd stress to tomato seedlings. This is in agreement with the previous research results and further confirms that reduced lipid peroxidation in AMF-inoculated seedlings supports the beneficial role of AMF in plants subjected to Cd stress [

17,

39]. Therefore, AMF can effectively alleviate the abnormal accumulation of osmotic regulatory substances induced by Cd, reduce the damage caused by membrane lipid peroxidation, and enhance the Cd tolerance of plants.

AMF also certainly change phytohormones levels such as strigolactone (SL), IAA, tZR, GA3, and ABA, which confer resistance to abiotic stress including drought, salt, and heavy metal stress in host plants by coordinating multiple signal transduction pathways [

57]. Strigolactone (SL) induces spore germination and promotes hyphal growth in AMF [

62]. Application of the strigolactone GR24 improved Cd tolerance by regulating its Cd uptake and antioxidant metabolism in

Hordeum vulgare L. [

63]. The high SL level in AMF tearted seedlings could lower Cd toxic action by regulating Cd accumulation and scavenging ROS in

M. hupehensis [

12]. AMF could increase seedlings biomass under Cd condition, possibly by increasing IAA level both in leaf and root of

M. hupehensis [

12]. In this research, the increase effect of IAA level in the mycorrhizal tomato under Cd condition have strengthened the mutualism between AMF and the host plants. AMF could inhibit the expression of Cd transport and absorption genes, increase Cd content in cell walls, promote antioxidant enzyme biosynthesis, and alleviate Cd-mediated growth inhibition [

18]. Relatively high root IAA levels were associated with higher plant Cd tolerance in mycorrhizal tomato under Cd condition.

The normal functioning of respiratory metabolism plays a crucial role in the growth and development of plants. When plants are exposed to heavy metal stress, an appropriate amount of intermediate metabolic products serves as the foundation for their adaptation to heavy metal-contaminated soil [

64]. As intermediate products of plant respiratory metabolism, succinic acid and malic acid are closely related to the plant’s metabolic process. In this study, Cd stress significantly reduced the contents of malic acid and succinic acid in the roots, which is consistent with the research results in sunflower [

65]. The concentration of respiratory metabolites in the root system is memorably correlated with the root activity in the rhizosphere soil. Malic acid and succinic acid, as respiratory metabolites of the root system, could strengthen root activity and accelerate plant growth [

64]. In this study, Cd stress may inhibit tomato growth by reducing the levels of malic acid and succinic acid in the roots, thereby weakening the root respiration metabolism. AMF not only significantly promotes plant growth and nutrient absorption, but also promotes the secretion of low-molecular-weight organic acids (such as malic acid and succinic acid) by the roots. Low-molecular-weight organic acids have significant impacts on the physical and chemical properties of the soil and the toxicity of heavy metals to plants. Low-molecular organic acids play a positive role in the activation and absorption of insoluble nutrients in the rhizosphere, which can convert insoluble substances into usable active components through acidification and other pathways, thereby promoting plant growth [

66]. In this study, the AMF inoculation treatment significantly promoted the secretion of succinic acid and malic acid in root. Under Cd stress, low-molecular organic acids can alter the speciation and bioavailability of heavy metals, thereby affecting the absorption and accumulation of Cd by the plants [

67]. The biological toxicity of Cd in soil mainly depends on its existence form. It exists in various forms in the soil, including exchangeable form, iron-manganese oxide form and organic-bound form, etc. Some studies have shown that the inoculation of AMF reduces the content of exchangeable Cd. This might be because the change in the number of soil microorganisms improves the growth of plant roots and their absorption of nutrients, thereby altering the form of Cd [

68]. The low-molecular-weight organic acids secreted by the root system are also one of the factors that affect the form of Cd. Among them, citric acid and malic acid can increase the content of exchangeable heavy metals in the soil, thereby achieving the purpose of activating heavy metals. Lactic acid and malic acid can also cause changes in the form of Cd by altering the pH value. The content of iron-manganese complexed Cd in the soil treated with AMF increased significantly after inoculation. The possible reason is that under the space limitation of the root bags, organic acids were concentrated, making it easier to alter the pH value and redox potential of the soil, thereby promoting the formation of iron-manganese complexed Cd [

69]. The content of organic Cd was significantly reduced. The possible reason for this is that AMF, in order to provide more nutrients to the host, promotes the decomposition of organic matter into small molecules that are easily absorbed by the host, thereby reducing the combination of organic matter and Cd, and resulting in a decrease in the content of organic-bound Cd [

69]. This study indicate that AMF can to some extent alleviate the negative effects of Cd on the secretion of citric acid and malic acid by tomato roots, enhance the plant’s tolerance to heavy metals, and thereby alleviate the inhibitory effect of Cd stress on plant growth. In this study, the AMF treatment significantly reduced the Cd content in the plants, indicating that AMF may enhance the tolerance of tomatoes to Cd by increasing the contents of malic acid and citric acid in the roots, thereby promoting their growth. The main reasons are as follows: First, the mycelia of AMF contain sites that can provide for the binding of heavy metals, allowing the heavy metals to be adsorbed, bound, and fixed on the mycelia, thereby reducing the stress of heavy metals on the host plants; Second, the inoculation of AMF significantly increased the biomass of tomatoes and was much higher than that of the control, which indirectly led to a decrease in the Cd content of the plants under the dilution effect of growth. Yu et al. [

70] indicate that the mycelium has a strong ability to adsorb Cd. This also fully demonstrates the significance of the AMF ecological function in this study. This research fully utilized the role of the AMF root exudate mycelium and concentrated the low-molecular organic acids secreted by the root system. It better promoted the complexation and chelation reactions between organic acids and Cd, reducing the toxicity of Cd to the plants, thereby enhancing the tolerance of tomatoes to Cd and promoting their growth.