Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Determination and Methods

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

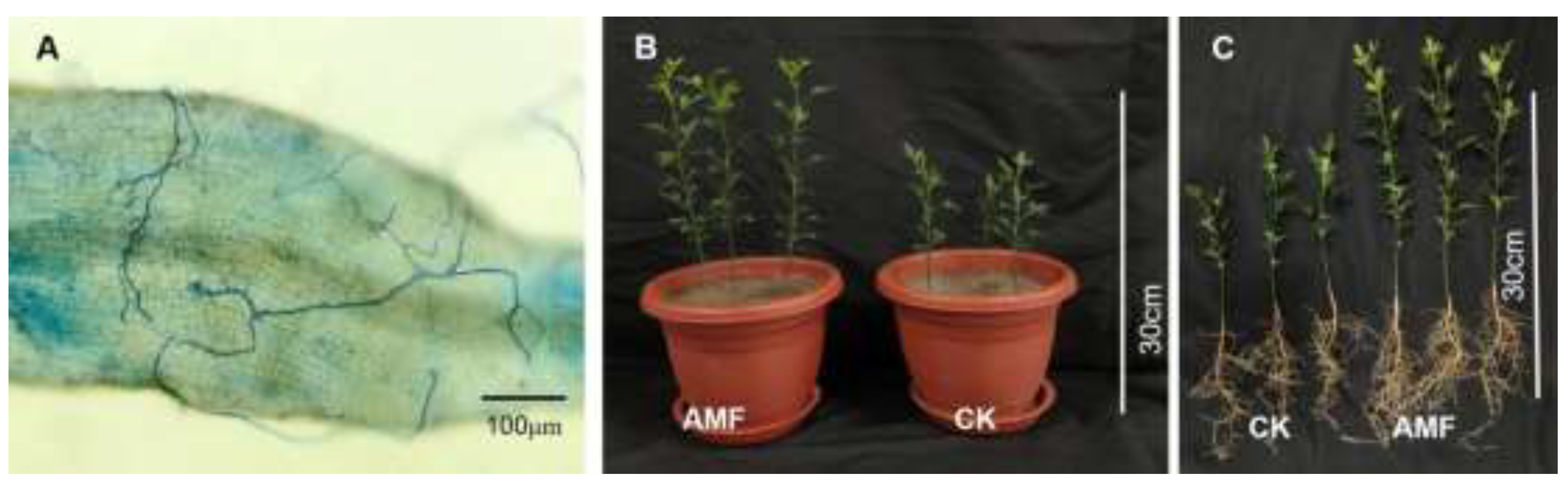

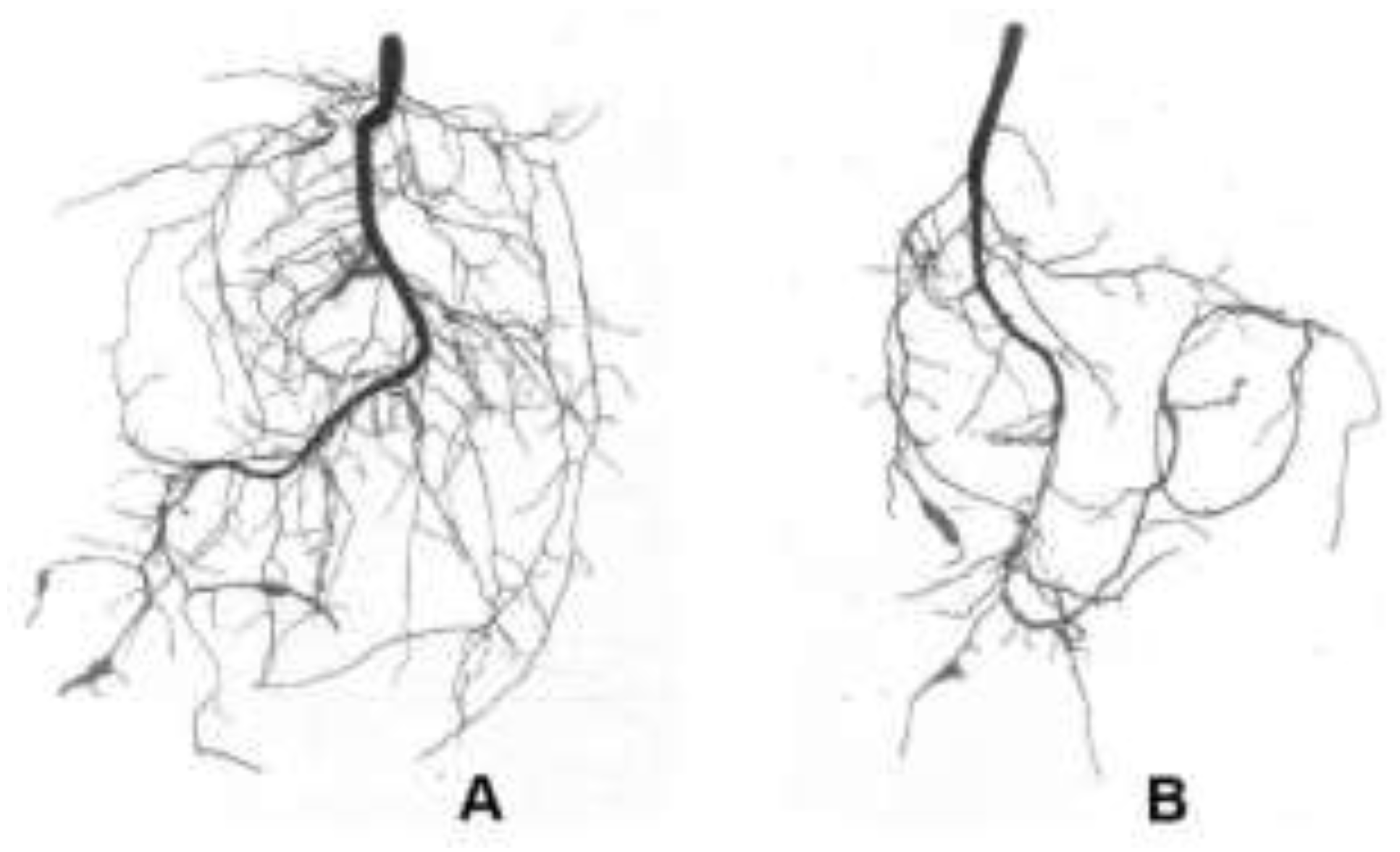

3.1. Effects of AMF on the Growth and Development of Trifoliate Orange Seedlings

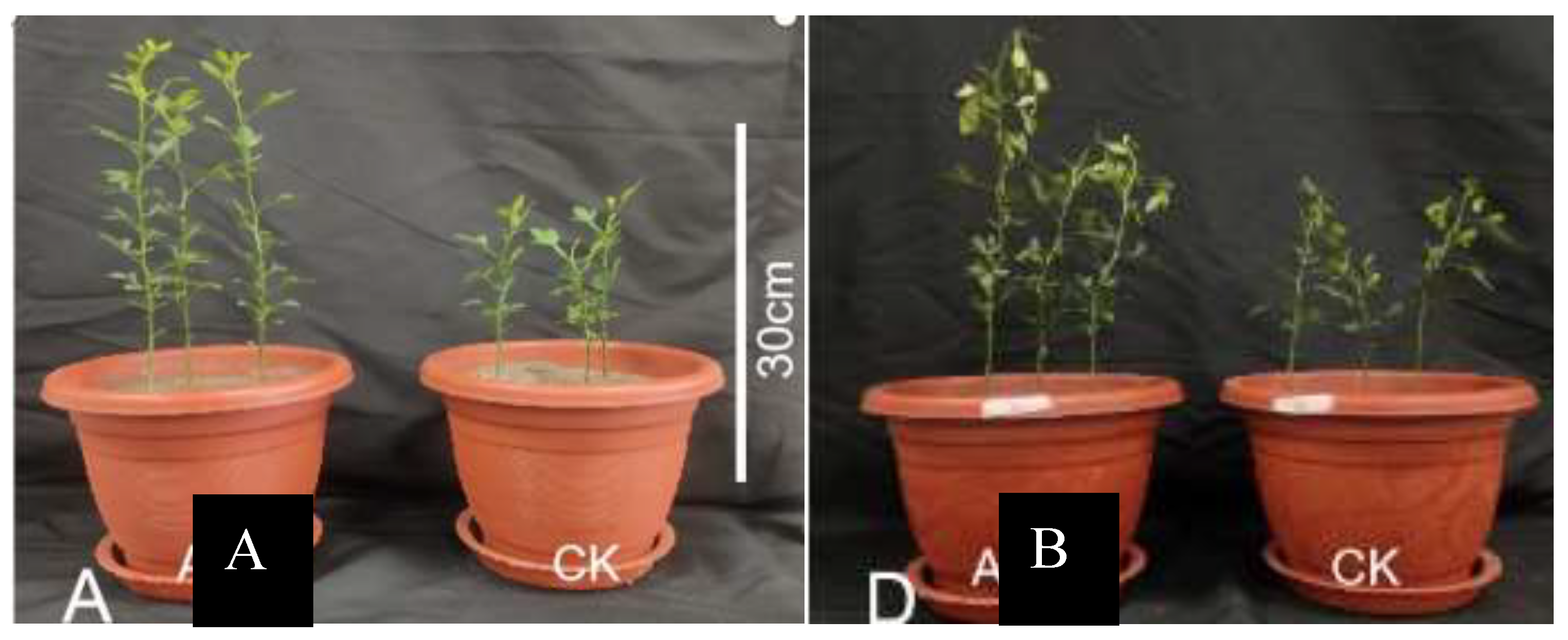

3.2. Effect of Low Temperature on the Morphology of Trifoliate Orange

3.3. Effect of AMF on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters of Trifoliate Orange Leaves at Low Temperature

3.4. Effect of AMF on Photosynthesis of Trifoliate Orange Leaves at Low Temperature

3.5. Effects of AMF on Relative Water Content And Relative Electrical Conductivity Of Trifoliate Orange Leaf At Low Temperature

3.6. Effect of AMF on the Content of Malondialdehyde and Hydrogen Peroxide in Trifoliate Orange Leaves at Low Temperature

3.7. Effects of AMF on Contents of Soluble Sugar, Soluble Protein and Trifoliate Orange leaf at Low Temperature

3.8. Effects of AMF On The Activities Of Superoxide Dismutase And Catalase In Trifoliate Orange At Low Temperature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhaliwal, L.K.; Shim, J.; Auld, D.; Angeles-Shim, R.B. Fatty acid unsaturation improves germination of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) under cold stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1286908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, A.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Physiological and molecular changes in plants grown at low temperatures. Planta 2012, 235, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, P. PbrCSP1, a pollen tube-specific cold shock domain protein, is essential for the growth and cold resistance of pear pollen tubes. Mol Breeding. 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Ma, C.L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Cao, H.L.; Kong, Y.M.; Yue, C.; Ha, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, J.Q.; et al. Global transcriptome profiles of Camellia sinensis during cold acclimation. Bmc Genomics. 2013, 14, 415–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Kong, X.J.; Khan, A.; Ullah, N.; Zhang, X. Plant coping with cold stress: molecular and physiological adaptive mechanisms with future perspectives. Cells 2025, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preet, M.; Parneeta, C.; Renu, D. Photosynthesis regulation, cell membrane stabilization and methylglyoxal detoxification seems major altered pathways under cold stress as revealed by integrated multi-omics meta-analysis. Physiol Mol Biol Pla. 2023, 29, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Kang, R.; Liu, C.H.; Xing, L.Y.; Wu, S.B.; Wang, Z.H.; Wu, C.L.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Zhao, R.L. Exogenous calcium alleviates the photosynthetic inhibition and oxidative damage of the tea plant under cold stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, L.; Muneer, M.A.; Aihua, S.; Guo, Q.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Huang, Z.R.; Li, W.Q.; Zheng, C.Y. Magnesium application improves the morphology, nutrients uptake, photosynthetic traits, and quality of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) under cold stress. Fronti Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1078128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saand, M.A.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, L.X.; Cao, H.X.; Yang, Y.D. Ntegrative omics analysis of three oil palm varieties reveals (Tanzania × Ekona) TE as a cold-resistant variety in response to low-temperature stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.; Zha, Q.; Hui, X.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. Research progress of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improving plant resistance to temperature stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.J.; Tong, C.L.; Wang, Q.S.; Bie, S. Mycorrhizas Affect physiological performance, antioxidant system, photosynthesis, endogenous hormones, and water content in cotton under salt stress. Plants 2024, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.J.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhang, F.; Hu, W.; Gong, S.B.; Wu, Q.S. Auxin modulates root-hair growth through its signaling pathway in citrus. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2018, 236, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.F.; Yuan, D.; Hu, X.C.; Zhang, D.J.; Li, Y.Y. Effects of mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth, nutrient absorption and phytohormones levels in tea under shading condition. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2020, 48, 2006–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Jin, L.F.; Wang, P.; Liu, F.; Huang, B.; Wen, M.X.; Wu, S.H. Effects of interaction of protein hydrolysate and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi effects on citrus growth and expressions of stress-responsive genes (Aquaporins and SOSs) under salt stress. J Fungi. 2023, 9, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.Y.; Zha, Q.; Hui, X.R.; Tong, C.L.; Zhang, D.J. Research progress of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improving plant resistance to temperature stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, P.; Jin, L.F.; Yv, X.F.; Wen, M.X.; Wu, S.L.; Liu, F.; Xu, J.G. Methylome and transcriptome analysis of flowering branches building of citrus plants induced by drought stress. Gene 2023, 880, 147595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Qu, J.; Wang, Y.; Fang, T.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Khan, M.; Chen, Q.; Xu, X.; et al. Transcriptome and metabolome atlas reveals contributions of sphingosine and chlorogenic acid to cold tolerance in Citrus. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Miao, X.C.; Deng, N.Y.; Liang, M.G.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.J.; Zeng, S.H. Identification of ascorbate oxidase genes and their response to cold stress in citrus sinensis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.L.; Xu, F.Q.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Tashkandi, M.A.; Wu, Q.S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, especially Rhizophagus intraradices as a biostimulant, improve plant growth and root columbin levels in Tinospora sagittata. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hao, Z.H.; Shao, H.; Feng, G.Z.; Chen, F.J.; Mi, G.H. Root growth, root senescence and root system architecture in maize under conservative strip tillage system. Plant and Soil. 2024, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.J.; LIU, C.Y.; Yang, Y.J.; Wu, Q.S.; Li, Y.Y. Plant root hair growth in response to hormones. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2019, 47, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, D.J.; Deng, X.Z. Phosphorus-induced change in root hair growth is associated with IAA accumulation in walnut. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2021, 49, 12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.H.; Li, H.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D.J. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal the effect of mycorrhizal colonization on trifoliate orange root hair. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2024, 336, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.H.; Li, H.; Tong, C.L.; Zhang, D.J.; Lu, Y.M. Ethylene modulates root growth and mineral nutrients levels in trifoliate orange through the auxin-signaling pathway. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2023, 51, 13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Ullah, H.; Ishfaq, M.; Khan, R.; Gul, S.L.; Gulfraz, A.; Wang, C.W.; Li, Z.F. Genotypic variation of tomato to AMF inoculation in improving growth, nutrient uptake, yield, and photosynthetic activity. Symbiosis 2024, 92, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.H.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, C.L.; Zhang, D.J. Effects of exogenous melatonin on plant growth, root hormones and photosynthetic characteristics of trifoliate orange subjected to salt stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 97, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huo, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, N.; Jiang, M.; Kong, R.; Mi, Q.; Li, M.; Wu, H. Construction of indicators of low-temperature stress levels at the jointing stage of winter wheat. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaškinová, J.; Tomaškin, J.; Drimal, M.; Bellido, J. The Impact of Abiotic Environmental Stressors on Fluorescence and Chlorophyll Content in Glycine max (L.) Merrill. Agronomy 2025, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, U.; Habib, U.; Muhammad, I.; Rahmatullah, K.; Syeda, L.G.; Ashrit, G.; Wang, C.W.; Li, Z.F. Genotypic variation of tomato to AMF inoculation in improving growth, nutrient uptake, yield, and photosynthetic activity. Symbiosis 2023, 92, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.G.; Kong, C.C.; Wang, S.X.; Xie, Z.H. Enhanced phytoremediation of uranium contaminated soils by arbuscular mycorrhiza and rhizobium. Chemosphere 2019, 217, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, V.; Snider, J.L.; Awori, K.J.; Pilon, C.; Brown, N.; Almeida, I.B.; Tishchenko, V. Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) growth and photosynthetic response to high and low temperature extremes. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2025, 220, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setua, G.C.; Kar, R.; Ghosh, J.K.; Das, K.K.; Sen, S.K. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on growth, leaf yield and phosphorus uptake in mulberry (morus alba L.) to VA-mycorrhizal inoculation under rainfed,lateritic soil condition. Biol Fertil Soil. 1999, 29, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Ullah, H.; Ishfaq, M.; Khan, R.; Gul, S.L.; Gulfraz, A.; Wang, C.W.; Li, Z.F. Genotypic variation of tomato to AMF inoculation in improving growth, nutrient uptake, yield, and photosynthetic activity. Symbiosis 2024, 92, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Bian, J.; He, Z. Application of AMF Alleviates Growth and Physiological Characteristics of Impatiens walleriana under Sub-Low Temperature. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, H.; Liang, K.; Huang, G.H.; Pinyopusarerk, K. Improved Tolerance of Teak (Tectona grandis L.f.) Seedlings to Low-Temperature Stress by the Combined Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza and Paclobutrazol. J Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 31, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.D.; Meng, S.Q.; Fu, M.R.; Chen, Q.M. Near-Freezing Temperature Storage Improves Peach Fruit Chilling Tolerance by Regulating the Antioxidant and Proline Metabolism. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhu, X.; Hou, M.; Luo, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, H.; Huang, X.; Hua, J. Effects of Low-Temperature Stress on Cold Resistance Biochemical Characteristics of Dali and Siqiu Tea Seedlings. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, T.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, N. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) YTH Domain-Containing RNA-Binding Protein (YTP) Family Members Participate in Low-Temperature Treatment and Waterlogging Stress Responses. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, J.X.; Qiu, C.Y.; Wei, W.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Deng, W.; Mo, R.L.; Lin, Q. Multivariate Analysis of the Phenological Stages, Yield, Bioactive Components, and Antioxidant Capacity Effects in Two Mulberry Cultivars under Different Cultivation Modes. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Biagioni, A.; Squeri, C.; Tombesi, S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Grafting cv. Grechetto Gentile Vines to New M4 Rootstock Improves Leaf Gas Exchange and Water Status as Compared to Commercial 1103P Rootstock. Agronomy 2020, 10, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liang, X.; Yang, Z. Effects of Low-Temperature Stress on Physiological Characteristics and Microstructure of Stems and Leaves of Pinus massoniana L. Plants 2024, 13, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P.; Li, Y.; Cui, C.; Huo, Y.; Lu, G.; Yang, H. Proteomic and metabolic profile analysis of low-temperature storage responses in Ipomoea batata Lam. tuberous roots. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Jin, W.J.; Liu, A.R.; Zhang, S.J.; Liu, D.L.; Wang, F.H.; Lin, X.M.; He, C.X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) increase growth and secondary metabolism in cucumber subjected to low temperature stress. Scientia Hortic-Amsterdam. 2013, 160, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Chen, S.S.; Wang, M.M.; Liu, D.L.; Chang, R.; Wang, Z.H.; Lin, X.M.; Bai, B.; Ahammed, G.J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Alleviates Chilling Stress by Boosting Redox Poise and Antioxidant Potential of Tomato Seedlings. J Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 35, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Jin, L.; Tong, C.L.; Liu, F.; Huang, B.; Zhang, D.J. Research Progress on the Growth-Promoting Effect of Plant Biostimulants on Crops. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024, 93, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Beneficial Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Overcoming Salt Stress in Sugar Beets (Beta vulgaris L.). Plants 2021, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swigonska, S.; Badowiec, A.; Mostek, A.; Krol, A.; Weidner, S. Formation and stability of polysomes and polysomal populations in roots of germinating seeds of soybean (Glycine max L.) under cold, osmotic and combined cold and osmotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol Plant. 2014, 36, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Liu, M. Humic Acid Alleviates Low-Temperature Stress by Regulating Nitrogen Metabolism and Proline Synthesis in Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Seedlings. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Jia, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Zou, D.; Wang, J.; Gong, W.; Han, Y.; Dang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Effects of Low-Temperature Stress During the Grain-Filling Stage on Carbon–Nitrogen Metabolism and Grain Yield Formation in Rice. Agronomy 2025, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Mao, Q.; Wang, J. Physiological Response to Low Temperature of Four Genotypes of Cyclocarya paliurus and Their Preliminary Evaluation to Cold Resistance. Forests 2023, 14, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, G.; Shen, J.; Xu, X.; Shou, W.; Xuan, Z.; He, Y. A SMALL AUXIN UP-REGULATED RNA gene isolated from watermelon (ClSAUR1) positively modulates the chilling stress response in tobacco via multiple signaling pathways. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.N.; Naraikina, N.V. Change of antioxidant enzyme activity during low-temperature hardening of Nicotiana tabacum L. and Secale cereale L. Russ J Plant Physl. 2020, 67, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, X.F.; Zu, Y.G. Production of reactive oxygen species and changes of protective enzymes in red pine seedlings under low temperature stress. Acta Bot anica Sinica 2000, 42, 148–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Song, F.B.; Liu, F.L.; Tian, C.J.; Liu, S.Q.; Xu, H.W.; Zhu, X.C. Effect of different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and physiology of maize at ambient and low temperature regimes. The Scientific World J. 2014, 2014, 956141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Mycorrhiza development | Plant growth | Biomass (g FM/plant ) |

||||

| Mycorrhizal infection rate AMF (%) |

Hyphal length (cm/g) |

Plant height (cm) | Stem diameter (mm) |

Leaf number | Shoot | Root | |

| AMF | 60.40±4.63a | 20.48±0.60a | 25.17±0.92a | 2.19±0.11a | 17.53±1.04a | 1.48±0.12a | 0.86±0.07a |

| CK | 0.00±0.00b | 0.00±0.00b | 13.13±1.10b | 1.53±0.09b | 12.07±1.11b | 0.64±0.05b | 0.57±0.04b |

| Treatments | Overall length (cm) | Projected area (cm2) |

Total surface area(cm2) | Diameter (mm) | Root volume (cm3) |

| AMF | 174.37±6.71a | 14.10±0.87a | 13.72±1.17a | 0.59±0.02a | 0.59±0.04a |

| CK | 150.82±9.04b | 13.43±1.29a | 9.33±0.64b | 0.58±0.04a | 0.41±0.03b |

| -5°C treated | QY_max | QY_Lss | NPQ_Lss | |

| CK | 0 h | 0.30±0.03b | 0.13±0.01b | 0.20±0.02b |

| 9 h | 0.14±0.01c | 0.05±0.00c | 0.26±0.02a | |

| AMF | 0 h | 0.35±0.02a | 0.21±0.02a | 0.17±0.01b |

| 9 h | 0.24±0.01b | 0.12±0.01b | 0.28±0.02a | |

| -5°C treated | Pn | Gs | Ci | Tr | |

| CK | 0 h | 4.31±0.37b | 0.14±0.01a | 330.65±14.61ab | 3.25±0.12b |

| 9 h | 0.74±0.06d | 0.02±0.00c | 243.22±22.86c | 0.15±0.01d | |

| AMF | 0 h | 6.67±0.57a | 0.16±0.01a | 355.35±32.14a | 4.20±0.39a |

| 9 h | 1.28±0.11c | 0.04±0.00bc | 302.67±29.33bc | 0.19±0.02c | |

| -5°C treated | Relative water content (%) | Relative electrical conductivity (%) | |

| CK | 0 h | 0.80±0.04b | 10.21±0.81c |

| 9 h | 0.63±0.05c | 48.01±2.25a | |

| AMF | 0 h | 0.91±0.08a | 10.22±0.72c |

| 9 h | 0.64±0.04c | 32.04±2.01b | |

| -5°C treated | Malondialdehyde (nmol/g) | Hhydrogen peroxide (umol/g) | |

| CK | 0 h | 0.58±0.04b | 55.26±4.89b |

| 9 h | 0.78±0.04a | 68.21±5.21a | |

| AMF | 0 h | 0.31±0.02c | 32.44±2.78d |

| 9 h | 0.56±0.03b | 48.23±2.45c | |

| -5°C treated | The soluble sugar (g/L) | The soluble protein (mg/g) | The content of Pro (ug/L) | |

| CK | 0 h | 8.08±0.34d | 2.56±0.19c | 310.54±21.12d |

| 9 h | 15.98±1.22b | 4.21±0.21a | 394.26±22.78b | |

| AMF | 0 h | 9.31±0.62c | 3.44±0.26b | 345.89±19.52c |

| 9 h | 17.52±1.43a | 4.23±0.35a | 418.28±32.37a | |

| -5°C treated | SOD (U/g) | CAT (U/g) | |

| CK | 0 h | 3008.22±198.31b | 152.51±10.12d |

| 9 h | 4755.92±354.24a | 215.28±13.26b | |

| AMF | 0 h | 3409.32±192.64b | 173.44±12.51c |

| 9 h | 5017.52±389.48a | 244.26±19.31a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).