1. Introduction

The Chicken infectious anaemia (CIA) is an immunosuppressive disease caused by the chicken infectious anaemia virus (CIAV) [

1]. Since its initial identification in Japan in 1970, CIAV has achieved a global distribution [

2]. In recent years, China has faced particularly severe outbreaks driven by the emergence of highly pathogenic strains, making the virus a major threat to its poultry industry [

3]. The virus primarily affects the bone marrow haematopoietic cells and pre-T lymphocytes in the thymus of chicks [

4], leading to anaemia and immunosuppression in chickens typically exhibiting yellowish-white bone marrow, atrophy of thymic lymphoid tissue, and hemorrhagic lesions [

5]. Beyond these clinical signs, CIAV infection is known to induce extensive apoptosis of thymocytes [

6], which profoundly impairs the generation of pathogen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes [

7]. In atrophied thymuses, haematopoietic cells are gradually replaced by adipocytes or proliferating stromal cells [

8], while the cortex and medulla are progressively replaced by proliferating reticular cells and fibroblast cells. CAV infection often occurs concurrently with, exacerbates, or complicates infections caused by other viruses, bacteria, or fungi, posing a serious threat to the health of chicken flocks [

9]. For instance, it has been observed that CIAV can depress vaccinal immunity to other diseases, such as Marek’s disease [

10], further increasing economic risks.

Currently, commercially available live attenuated vaccines are widely used in breeder flocks outside of China [

11]. However, these vaccines retain residual virulence and can cause damage to the immune organs of chickens [

8]. Specifically, it has been reported that vaccinal strains can persist in the spleen and thymus of young chicks, inducing thymic lymphoid cell disorders and causing significant atrophy of lymphoid tissues, which may compromise the host’s immune status [

8]. Although inactivated vaccines offer moderate protection for breeders [

12], their large-scale commercial production is hindered by the inability to propagate CIAV to high titers in vitro [

13]. While innovative strategies like DNA vaccines [

14] or virus-like particles (VLPs) [

15] have been investigated to address these issues, they often face challenges related to high production costs and complex manufacturing processes. Consequently, the development of safer and more efficacious vaccines is crucial for the effective control of CIAV.

The viral genome of CIAV contains three overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) [

16]. These ORFs encode three functionally distinct proteins: VP1, VP2, and VP3. VP1 is the major capsid protein. It carries DNA-binding activity [

17] and contains a hypervariable region located at amino acids 139–151 [

18]. However, VP1 expressed in isolation often fails to adopt its native immunogenic conformation, especially in prokaryotic systems [

18]. VP2 acts as a scaffold protein that assists in the proper folding of VP1 [

19]. It also exhibits dual-specificity phosphatase activity [

20], which is essential for viral replication. VP3 localizes to the nucleus of infected cells and functions to induce apoptosis [

21]. Based on these functional attributes, the co-expression or combined use of VP1 and VP2 has emerged as a rational strategy for developing genetically engineered vaccines against CIAV [

22].

In this study, we aimed to develop a cost-effective subunit vaccine by expressing CAV VP1 and VP2 in E. coli [

23]. To solve the problem of VP1 predominantly forming insoluble inclusion bodies, we established a refolding methodology to recover VP1 from inclusion bodies using soluble VP2 as a molecular chaperone. This “VP2-assisted co-refolding” strategy leverages VP2’s natural function to restore critical conformational epitopes. The immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the refolded protein complex were subsequently evaluated in a chicken model, providing a promising and economical alternative for the prevention and control of CIAV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Ethical Statement

The specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens used in this experiment were obtained from the National Poultry Animal Laboratory Resource Centre (Harbin, China). This study was conducted strictly in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Experimental chickens were anaesthetised via CO2 inhalation prior to dissection, then euthanised by exsanguination. Dissection was performed to examine thymus tissue. All animal experiments were approved by the HVRI Animal Ethics Committee and conducted under an authorised scheme (No. 241206-03-GR, 06 December, 2024).

2.2. Viruses and Plasmids

The virus isolated from liver samples of diseased chickens at a Jilin Province farm was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum. MDCC-MSB1 cells were maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2 conditions. Following inoculation, the virus underwent serial passage until pronounced viral replication characteristics emerged. This isolate was ultimately designated CIAV JL17P10 strain and employed as the challenge virus for subsequent experiments. The HeN/193001 strain, obtained from a poultry farm in Henan Province using the same method, served as the parental virus and template for subsequent PCR amplification sequences. The complete genomes of both isolated viruses were ligated to the pMD™ 18-T vector (Takara, Beijing, China) for sequencing validation, yielding the full viral sequences.

2.3. Construction of the Expression Plasmid and VP1, VP2 Proteins

The nucleic acid sequences of CAV VP1 and VP2 were optimised for E. coli codons and synthesised by Harbin Seven Bioscience Co., Ltd. (Harbin, China) in the pGEX-6P-1 prokaryotic expression vector. The prokaryotic expression vectors pET32a and pET24b were obtained from laboratory stocks. The entire VP1 gene sequence was amplified using primers VP1-F1 and VP1-F2, and inserted into pET32a vector digested with restriction enzymes BamHⅠ and XhoⅠ. Homologous recombination ligation with C112 (Takara, Beijing, China) for homologous recombination to construct the complete plasmid. The vector carries a 6×His tag at the N-terminus to facilitate SaI1 purification. The entire VP2 gene sequence was amplified using primers VP2-F1 and VP2-F2 and inserted into the pET24b vector digested with restriction enzymes SalⅠ and XhoⅠ. A Sumo tag was introduced at the C-terminus of the construct to promote proteolytic expression. Upon completion, the two plasmids were designated pET32a-VP1 and pET24b-VP2 respectively.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer name |

Primer sequence(5′-3′) |

| VP1-F1 |

GCCATGGCGATATCGGATCCGATGGCACGTCGTGCACGTCG |

| VP1-R1 |

AGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGCGGCTGGCTACCCCA |

| VP2-F1 |

GGATCCGAATTCGAGCTCCGTCGACATGCACGGTAACGGC |

| VP2-R1 |

CATCGGACACCTTTAAATTGATGTGAGTCTCAGGC |

2.4. Expression and Purification of VP1 and VP2 Proteins

The constructed plasmids pET32a-VP1 and pET24b-VP2 were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells (WEIDI, Shanghai, China) to induce expression of the VP1 and VP2 proteins. The E. coli strains harbouring these two plasmids were inoculated into LB broth containing the corresponding antibiotic. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm for 2–3 hours until an OD600 of 0.8 was reached, at which point 1 mM IPTG was added for induction. Cultures were then transferred to shaking incubators maintained at 16 °C, 20 °C, and 27 °C respectively. Following incubation, bacteria were centrifuged from LB medium and resuspended in PBS. The suspension was subjected to pulsed ultrasonication at 39% intensity on ice until translucency was achieved. Centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes yielded supernatant and inclusion body pellet. Specified volumes of each fraction were mixed with 5× sample buffer and boiled for 10 minutes. Protein expression was confirmed via SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

After determining the expression temperature, large-scale induction of protein expression was performed. A 1:100 dilution of the bacterial culture was inoculated into 500 ml LB broth for induction. Following centrifugation to collect the culture, the cells were resuspended in Binding Buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM sodium chloride, 30 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). Following ultrasonic disruption using the aforementioned method, separate the supernatant and inclusion bodies. Precipitate the VP1 inclusion bodies and dissolve them in 8M urea to form a clear, transparent liquid for subsequent experimental use. For VP2, directly collect the supernatant. Load the solutions containing the target protein onto Ni NTA resin columns, incubate overnight for 12 hours to ensure maximum binding, and purify using gravity column elution. The Ni NTA resin column precipitate containing VP1 protein was washed three times with 5 CV of 50 mM imidazole binding buffer. Elution with 1 CV of elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.4) yielded purified VP1 protein. The VP2 protein-bound Ni NTA resin column was precipitated, washed three times with 5 CV of 90 mM imidazole binding buffer, and eluted with 1 CV of elution buffer to obtain purified VP2 protein. GST-VP1 protein was expressed using the prokaryotic expression plasmid pGEX-6P-1. The supernatant was loaded onto Glutathione Sepharose 4B and incubated overnight for 12 hours. Glutathione elution buffer (10 mM reduced glutathione, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0). Add 1 CV of glutathione elution buffer to the pellet, gently agitate at room temperature for 10 minutes to elute the protein bound to the gel. Centrifuge at 500 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. Transfer the supernatant (containing the eluted fusion protein) to a tube. Repeat the elution three times and pool the three supernatants. The three purified proteins obtained were quantified using the Bradford method. The purified proteins were stored at -80 °C until further use.

2.5. Inclusion Body Protein Gradient Dialysis Reproteinisation

In vitro renaturation of VP1 protein from recombinant inclusion bodies was performed using gradient dialysis. The specific procedure is as follows: First, the preliminarily purified inclusion body protein was fully dissolved in a denaturing buffer containing 8 M urea. Subsequently, the entire protein solution was transferred into a pre-treated dialysis bag (Biosharp, Guangzhou, China), ensuring a tight seal. Subsequently, the dialysis bag was sequentially placed in urea-containing renaturation buffers of decreasing concentration for stepwise dialysis: Dialysis in 6 M urea solution at 4 °C for 6–8 hours to achieve initial unfolding of the protein; followed by transfer to 4 M urea solution for a further 4 hours of dialysis, during which pre-purified VP2 protein was added to promote assembly of the hetero-complex; Finally, transfer to 2 M urea solution and perform overnight dialysis (approximately 12–16 hours) at 4 °C under gentle stirring to progressively remove the denaturant, allowing the protein to slowly refold to its native conformation. Two experimental groups were established based on the ratio of VP1 to VP2 protein added: a 1:1 group and a 2:1 group. Upon completion of dialysis, collect the reduced samples from the dialysis bags and analyse protein expression via SDS-PAGE electrophoresis.

2.6. Vaccine Immunisation and Animal Experiments

Following quantitative dialysis, the two pooled protein fractions and GST-VP1 protein were diluted to 100 μg/mL. Each was mixed 1:1 with liquid paraffin oil adjuvant and subjected to high-speed shear emulsification using a disperser (IKA, Germany) [

19]. The emulsions were stored at 4 °C for subsequent use. Thirty-five day-old SPF chickens were randomly divided into five groups of seven birds each. Three groups served as the immunisation groups, each receiving an intramuscular injection of 100 μL oil-adjuvanted vaccine on day 7. Two weeks post-vaccination, the three experimental groups were challenged with 10

5.5 TCID

50 of the virulent CIAV strain JL17 P10. The CIAV challenge control group (n=7) received a subcutaneous injection of 10

5.5 TCID

50 of the virulent CIAV strain JL17 P10 on day 21. The healthy control group (n=10) received the corresponding solvent during the experimental period as a sham control. Thirteenth day post-challenge, thymuses were collected from each group and weighed. Thymus indices were calculated using the formula (TBIX): (thymus:body weight ratio)/(thymus:body weight ratio of healthy group).

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Prokaryotic Expression Vectors and Protein Expression

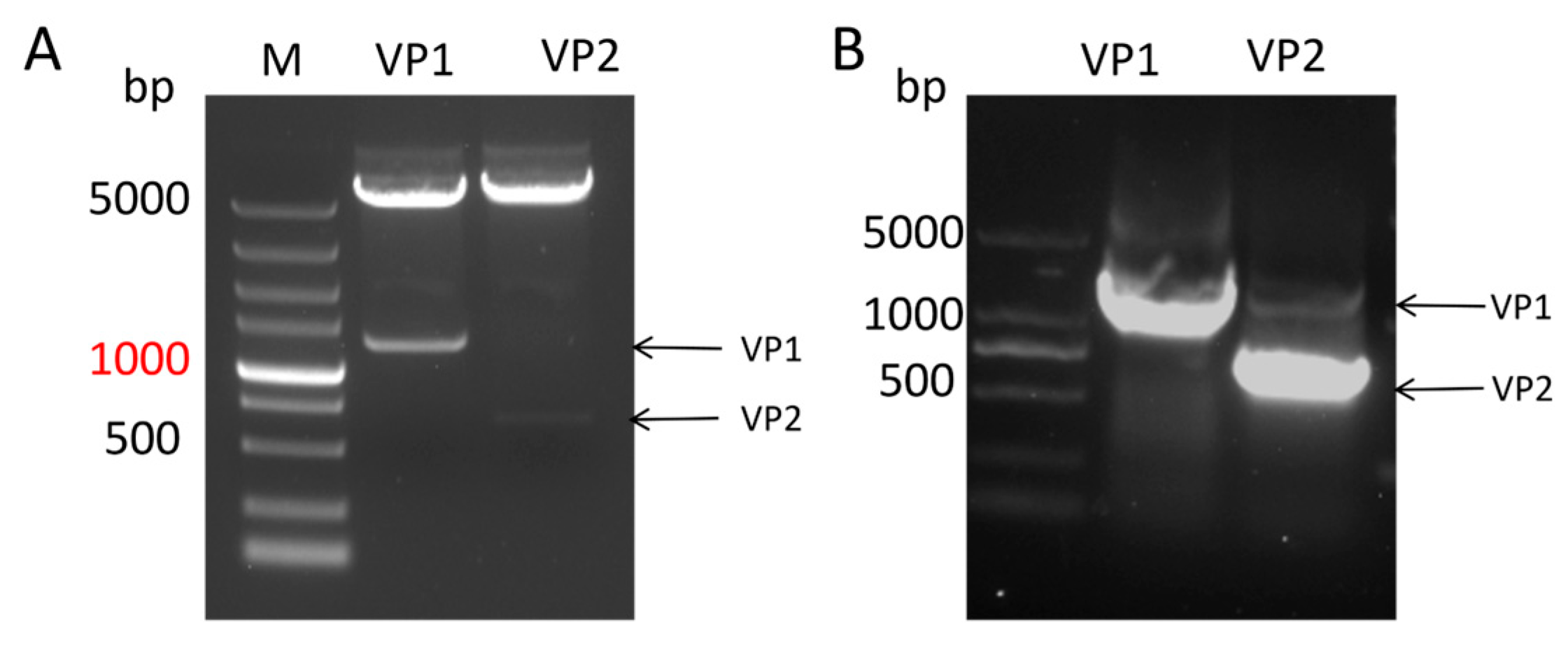

To obtain CIAV VP1 and VP2 proteins, the VP1 and VP2 genes were cloned into the prokaryotic expression vectors pET32a and pET24b, respectively, successfully constructing the recombinant plasmids pET32a-VP1 and pET24b-VP2 (

Figure 1A). Identification by restriction enzyme digestion and PCR confirmed the correct construction of the vectors (

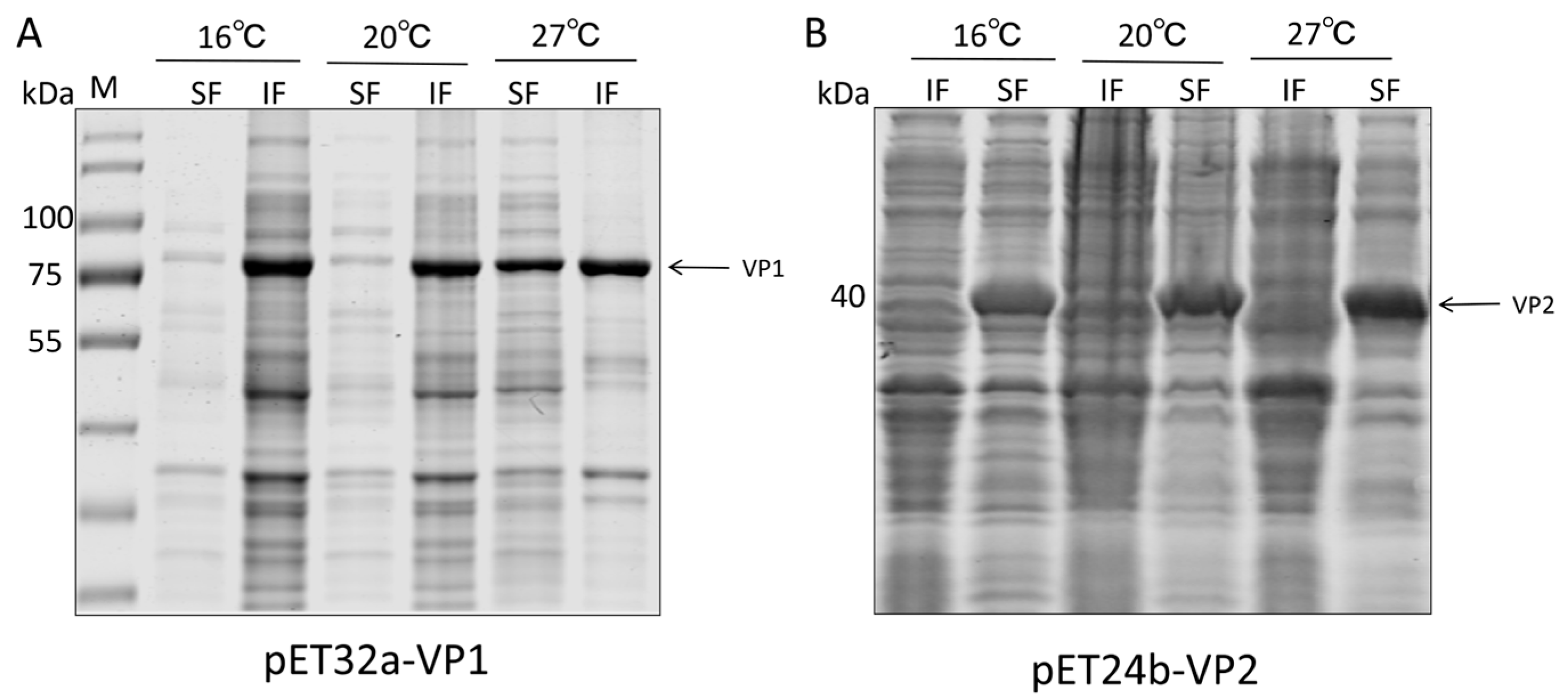

Figure 1B). After transforming these recombinant plasmids into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells, expression was induced with IPTG at different temperatures (16 °C, 20 °C, and 27 °C). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed distinct specific bands at approximately 72 kDa (VP1) and 53 kDa (VP2, containing the Sumo tag) (

Figure 2), which were consistent with the theoretical molecular weights calculated from their amino acid sequences. Expression analysis indicated that the VP1 protein was predominantly expressed as insoluble inclusion bodies at all tested temperatures, with the highest total expression level observed at 27 °C, thus establishing 27 °C as the optimal induction condition for maximizing antigen yield. In contrast, the VP2 protein exhibited favorable soluble expression at 16 °C, 20 °C, and 27 °C, with the highest soluble yield achieved at 20 °C. This high solubility of VP2 was crucial for the subsequent refolding strategy, as it allowed VP2 to function effectively as a chaperone in the liquid phase.

3.2. Protein Purification and Refolding

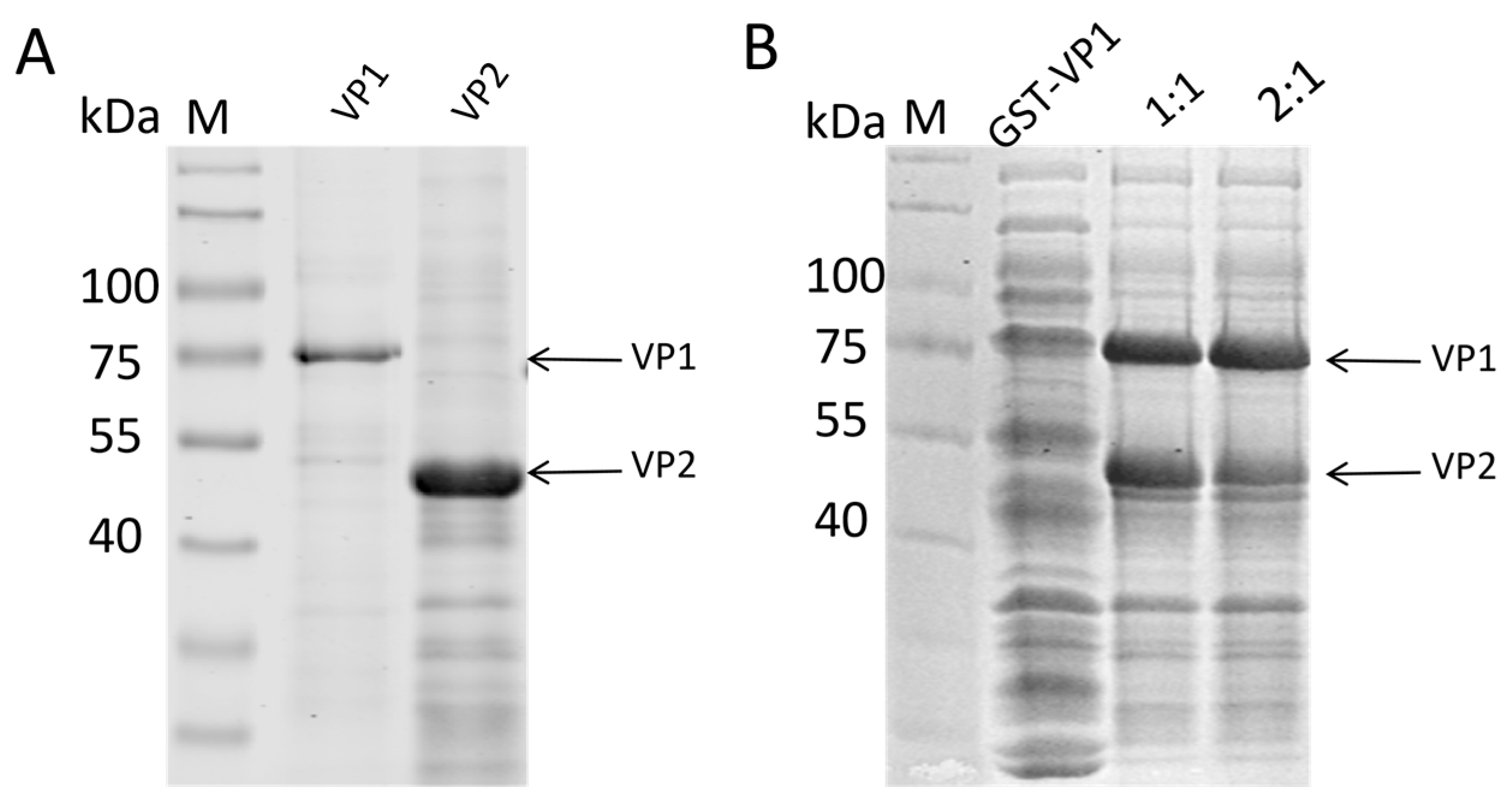

To purify the expressed proteins, nickel-affinity chromatography was first applied to the soluble VP2 fraction, yielding high-purity VP2 protein (

Figure 3A). For the VP1 protein, which was primarily present in inclusion bodies, it was first denatured with urea, purified via nickel-affinity chromatography, and then mixed with the soluble VP2 protein at different ratios. Refolding of the mixed proteins was performed using a gradient urea dialysis method to gradually remove the denaturant and allow hydrophobic interactions to re-establish in the presence of the scaffold protein. SDS-PAGE analysis of the refolded protein samples confirmed the successful refolding of both VP1 and VP2 proteins, which remained stable across the different mixing ratios (

Figure 3B). Crucially, no significant precipitation was observed in the dialysis bag after the removal of urea, particularly in the mixed groups. This indicates that the interaction between VP1 and VP2 prevented the aggregation of VP1, effectively maintaining it in a soluble state and suggesting the formation of stable VP1/VP2 hetero-complexes.

3.3. Protective Efficacy of the VP1/VP2 Subunit Vaccine Against CAV Challenge

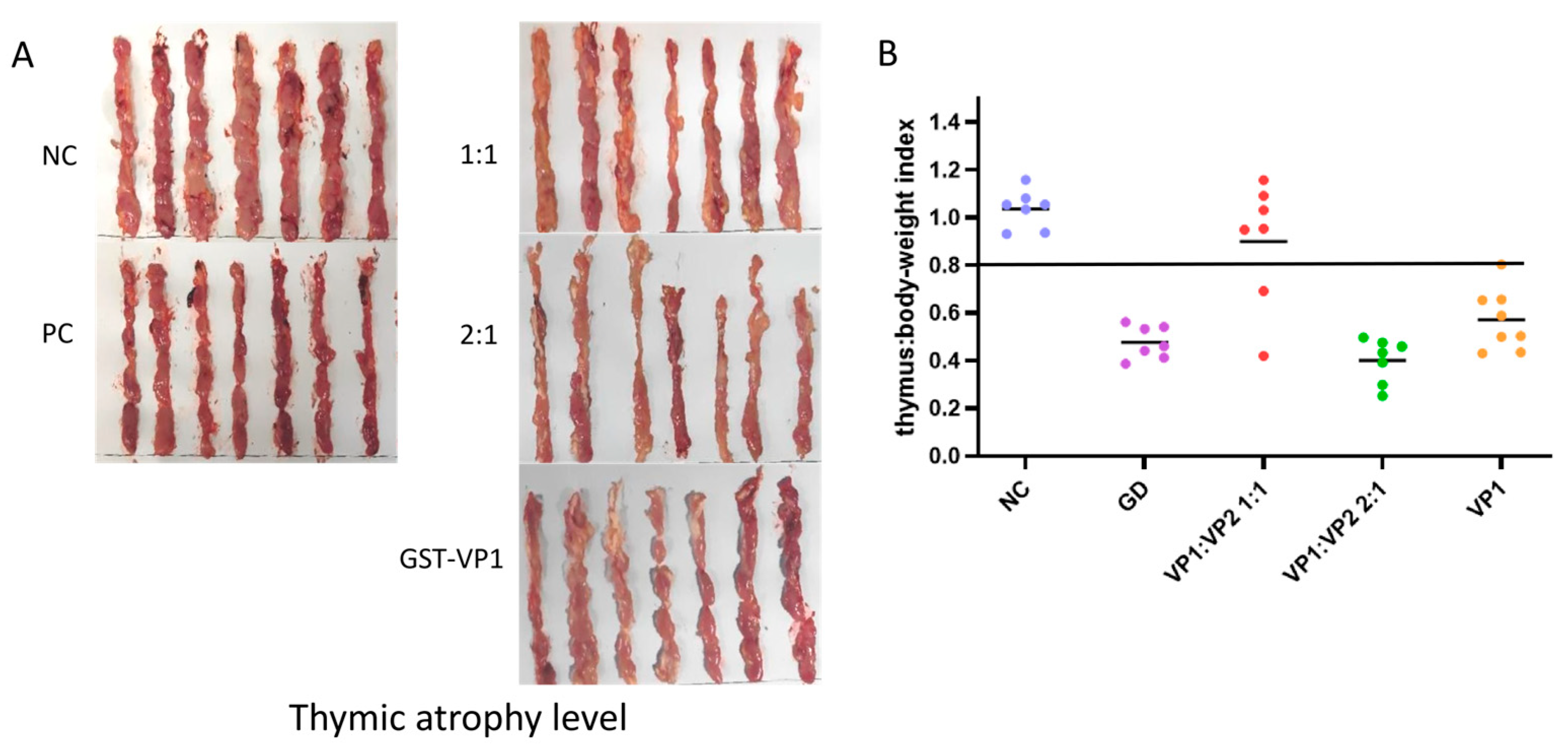

To evaluate the immunoprotective effect of the refolded VP1/VP2 complex proteins, the proteins were emulsified at different ratios and used to immunize 3-day-old SPF chickens. At 14 days post-immunization, the chickens were challenged with a virulent CAV strain. Necropsy results at 12 days post-challenge showed significant thymic atrophy in both the blank control and challenge control groups, characterized by a marked reduction in thymic lobe size and a change in color from healthy white to translucent or yellowish, indicating severe depletion of lymphoid cells. Among the experimental groups, the VP1:VP2 (1:1) immunized group performed best, with 5 out of 7 chickens showing no macroscopic thymic lesions and retaining normal thymic morphology similar to the healthy control group. In contrast, the other VP1:VP2 ratio groups and the VP1 protein control group exhibited varying degrees of thymic atrophy, demonstrating limited protective efficacy (

Figure 4A). This disparity highlights the critical role of the stoichiometric ratio in forming effective immunogens. Thymus index analysis further indicated that only the VP1:VP2 (1:1) immunized group had a thymus index significantly higher than that of the challenge control group (

Figure 4B), suggesting that this formulation effectively protected the immune organs from virus-induced damage. Comprehensive results demonstrate that, among all tested formulations, the subunit vaccine prepared at a 1:1 ratio of VP1 to VP2 proteins provided the optimal protective efficacy, achieving a protection rate of 71.4% (5/7) against challenge with the virulent CAV strain. This protection rate was superior to that of the VP1-only group, confirming that the VP2-assisted refolding strategy significantly enhances the immunogenicity of the subunit vaccine.

4. Discussion

The development of a vaccine that balances high safety with economic feasibility remains the central challenge in controlling Chicken Infectious Anemia Virus (CIAV) [

1,

2,

3]. While current live and inactivated vaccines have reduced disease incidence, they are persistently limited by safety risks regarding virulence reversion or prohibitive production costs [

8,

11,

12,

13]. Distinguishing from these traditional approaches, this study establishes a scalable prokaryotic platform that successfully overcomes the inclusion body bottleneck via a novel “VP2-assisted co-refolding” strategy. Our data demonstrates that the refolded VP1/VP2 complex not only recovers native immunogenicity but also confers significant protection (71.4%) in clinical challenge, providing a solid proof-of-concept for a safer, cost-effective next-generation subunit vaccine.

The design of this vaccine was based on the functional synergy between the capsid protein VP1, the primary target for neutralizing antibodies, and the scaffold protein VP2, which is essential for proper VP1 folding [

19]. To achieve cost-effective production crucial for future application, we employed an E. coli prokaryotic expression system over eukaryotic platforms. A central challenge was that VP1 predominantly formed insoluble inclusion bodies, losing its native immunogenic conformation [

18]. To solve this, we innovated a “VP2-assisted co-refolding” strategy. Leveraging VP2’s natural chaperone-like function, we added soluble VP2 during the gradient dialysis refolding of denatured VP1 inclusion bodies. The resulting VP1/VP2 (1:1) complex showed superior protective efficacy compared to other ratios, strongly indicating that VP2 actively guided the restoration of VP1’s correct, protective three-dimensional structure rather than merely acting as a physical mixture. This work validates a viable method for the economical production of conformational antigens using a prokaryotic system.

While the current “VP2-assisted co-refolding” strategy yielded a promising 71.4% protection rate, achieving the robust efficacy required for field application necessitates immediate refinements, such as optimizing the VP1:VP2 ratio and immunization protocol. However, the pivotal future direction lies in advanced antigen engineering to assemble Virus-Like Particles (VLPs). Unlike soluble complexes, true VLPs mimic the native virion’s T=1 icosahedral symmetry, presenting high-density conformational epitopes that effectively cross-link B-cell receptors to trigger potent neutralizing antibodies and cellular immunity [

15], while also ensuring superior safety by eliminating virulence reversion risks [

16]. Mechanistically, since VP1 assembly is strictly dependent on the scaffolding function of VP2, future work must focus on fine-tuning the interaction kinetics to transition from forming soluble hetero-complexes (as achieved in this study) to inducing self-assembly into intact capsids. The feasibility of this approach is strongly bolstered by the success of

E. coli-derived vaccines for Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2), a virus structurally analogous to CIAV [

24]. Studies confirm that prokaryotic PCV2 VLPs can induce robust humoral and cellular immune responses (e.g., elevated IFN-γ and TNF-α) and provide protection comparable to commercial vaccines [

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, advancing the research towards a VLP-based vaccine strategy represents a significant forward-looking direction. Combining the cost-efficiency of our E. coli expression system with optimized VLP assembly technology could ultimately yield a superior, next-generation vaccine that perfectly balances safety, efficacy, and affordability for global CIAV control.

Author Contributions

YZL and YLG supervised the project; YZL and SHL designed the experiments; MXH, YPZ, RG, HJS and WZM performed the experiments; YLD, XLQ, HYC, SYW, and YTC provided resources; YZL and SHL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; YZL and YLG provided funding. All authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-41-G15), the Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-CSLPDCP-202401).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval No. 241206-03-GR, 06 December 2024).

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested by writing to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- McNulty, M.S. Chicken anaemia agent: A review. Avian Pathol. 1991, 20, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Techera, C.; Marandino, A.; Tomás, G.; Grecco, S.; Hernández, M.; Hernández, D.; Panzera, Y.; Pérez, R. Origin, spreading and genetic variability of chicken anaemia virus. Avian Pathol. 2021, 50, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Jia, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Qi, L.; Zhao, P. Molecular characterization and pathogenicity study of a highly pathogenic strain of chicken anemia virus that emerged in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1171622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noteborn, M.H.; de Boer, G.F.; van Roozelaar, D.J.; Karreman, C.; Kranenburg, O.; Vos, J.G.; Jeurissen, S.H.; Hoeben, R.C.; Zantema, A.; Koch, G. Characterization of cloned chicken anemia virus DNA that contains all elements for the infectious replication cycle. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 3131–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.Y.; Dhama, K.; Malik, Y.S. Impact of virus load on immunocytological and histopathological parameters during clinical chicken anemia virus (CAV) infection in poultry. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 96, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen, S.H.; Wagenaar, F.; Pol, J.M.; van der Eb, A.J.; Noteborn, M.H. Chicken anemia virus causes apoptosis of thymocytes after in vivo infection and of cell lines after in vitro infection. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 7383–7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski-Grimsrud, C.J.; Schat, K.A. Infection with chicken anaemia virus impairs the generation of pathogen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology 2003, 109, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziry, A.; Silim, A.; Bleau, C.; Frenette, D.; Lamontagne, L. Chicken infectious anaemia vaccinal strain persists in the spleen and thymus of young chicks and induces thymic lymphoid cell disorders. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P.; Shukla, S.K.; Mahendran, M.; Dhama, K.; Chawak, M.M.; Kataria, J.M. Prevalence of chicken infectious anaemia virus (CIAV) in commercial poultry flocks of northern India: A serological survey. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, N.; Han, N.; Wu, J.; Cui, Z.; Su, S. Depression of vaccinal immunity to Marek’s disease by infection with chicken infectious anemia virus. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, J.K.; Cloud, S.S. The isolation and characterization of chicken anemia agent (CAA) from broilers in the United States. Avian Dis. 1989, 33, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, B.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Dai, Z.; Bi, Y.; Xie, Q. Assessing the efficacy of an inactivated chicken anemia virus vaccine. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1916–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.T.M.; Nguyen, G.V.; Do, L.D.; Dao, T.D.; Le, T.V.; Vu, N.T.; Cao, P.T.B. Chicken infectious anaemia virus infections in chickens in northern Vietnam: Epidemiological features and genetic characterization of the causative agent. Avian Pathol. 2020, 49, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, P.M.; Dhama, K.; Rawool, D.B.; Wani, M.Y.; Tiwari, R.; Singh, S.D.; Singh, R.K. Development of a DNA vaccine for chicken infectious anemia and its immunogenicity studies using high mobility group box 1 protein as a novel immunoadjuvant. Vaccine 2015, 33, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.-Y.; Liu, Y.-C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chang, P.-C.; Hsieh, M.-K.; Shien, J.-H.; Ou, S.-C. Preparation of chicken anemia virus (CAV) virus-like particles and chicken interleukin-12 for vaccine development using a baculovirus expression system. Pathogens 2019, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; van Roozelaar, D.J.; Verschueren, C.A.; van der Eb, A.J.; Noteborn, M.H. Immunogenic and protective properties of chicken anaemia virus proteins expressed by baculovirus. Vaccine 1995, 13, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, G.-H.; Lin, M.-K.; Lien, Y.-Y.; Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, F.-C.; Lee, M.-S.; Chen, H.-J.; Lee, M.-S. Characterization of the DNA binding activity of structural protein VP1 from chicken anaemia virus. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-S.; Hseu, Y.-C.; Lai, G.-H.; Chang, W.-T.; Chen, H.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Wang, M.-Y.; Kao, J.-Y.; You, B.-J.; et al. High yield expression in a recombinant E. coli of a codon optimized chicken anemia virus capsid protein VP1 useful for vaccine development. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.-H.; Lin, M.-K.; Lien, Y.-Y.; Fu, J.-H.; Chen, H.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Tzen, J.T.; Lee, M.-S. Expression and characterization of highly antigenic domains of chicken anemia virus viral VP2 and VP3 subunit proteins in a recombinant E. coli for sero-diagnostic applications. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A.; Jackson, D.C.; Crabb, B.S.; Browning, G.F. Chicken anemia virus VP2 is a novel dual specificity protein phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 39566–39573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallister, J.; Fahey, K.J.; Sheppard, M. Cloning and sequencing of the chicken anaemia virus (CAV) ORF-3 gene, and the development of an ELISA for the detection of serum antibody to CAV. Vet. Microbiol. 1994, 39, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Chang, W.C.; Yi, H.H.; Tsai, S.-S.; Liu, H.J.; Liao, P.-C.; Chuang, K.P. Development of a subunit vaccine containing recombinant chicken anemia virus VP1 and pigeon IFN-γ. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 167, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yin, M.; Li, Y.; Su, H.; Fang, L.; Sun, X.; Chang, S.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y. DNA prime and recombinant protein boost vaccination confers chickens with enhanced protection against chicken infectious anemia virus. Viruses 2022, 14, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.R.; Opriessnig, T. Epidemiology and vaccine efficacy of porcine circovirus type 2d (PCV2d). Vaccines 2020, 8, 587. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. Efficient expression and purification of porcine circovirus type 2 virus-like particles in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2016, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Optimized production of full-length PCV2d virus-like particles in Escherichia coli: A cost-effective and high-yield approach for potential vaccine antigen development. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2456–2465. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.C.; Lin, W.L.; Wu, C.M.; Wu, C.J.; Chi, J.N.; Chien, M.S.; Huang, C. Characterization of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) capsid particle assembly and its application to virus-like particle vaccine development. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).