1. Introduction

Phytolacca americana L. (pokeweed) is an invasive plant, native to eastern North and South America, whose proliferation has now expanded across the entire globe. The spread of invasive species poses a significant threat to biodiversity and can negatively affect native species. In general, such invasions are neither geographically nor climatically uniform, tending to be uncommon in harsh environments but widespread in temperate regions.

In Europe,

P. americana commonly colonizes forest edges, open woodlands, and a variety of other habitats, where it forms dominant and dense stands [

1]. Portugal is no exception: the species is now widespread not only on the mainland but also across the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores. The growing spread of this species in near-natural habitats has led to evaluating its invasive capacity and associated ecological risks [

2], as well as assessing its possible application in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries [

3,

4]. Given its invasive status and broad distribution throughout Europe, strategies that simultaneously mitigate its ecological impact and harness its potential value are increasingly necessary to support ecological balance.

P. americana has been used in folk medicine, although its therapeutic applications have been limited by its toxicity, particularly among some varieties [

5]. In turn,

Phytolacca species with white flowers and white roots are considered edible and safe, whereas those bearing red flowers and reddish roots can be harmful, toxic, or even hallucinogenic [

5,

6]. Several toxic constituents including phytolaccin (alkaloid), phytolactoxin (resin), phytolacagenin (saponin), and lectin (protein), have been identified in its different organs, although mostly concentrated in the roots, fruits, and seeds [

4]. Nevertheless,

P. acinosa,

P. esculenta, and

P. americana (all characterized by white flowers) are classified as edible plants and are recognized for a range of biological activities, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [

5,

7]. Furthermore, the edibility of these berries may improve following thermal treatments such as cooking, blanching, or even more intensive technological processing. Ethnobotanical knowledge has frequently guided the search for novel bioactive molecules, and the

Phytolacca genus is particularly rich in triterpenoid saponins (e.g., phytolaccosides A–D, acinosolic acid methyl ester, phytolaccagenin, jaligonic acid, phytolaccagenic acid, and esculenic acid), as well as flavonoids, phenolic acids, sterols, and polysaccharides [

8,

9,

10]. These compounds have been associated with additional bioactivities, such as diuretic and anti-hyperplasia actions on mammary tissue [

11,

12].

P. americana berries also contain high concentrations of betalains (betacyannins and betaxanthins), which has supported their use as food additives and natural colorants [

13]. Their characteristic dark purple color is mainly attributed to phytolaccanin, a non-toxic chromoalkaloid and betalain pigment. These pigments show strong potential for use in food systems that benefit from improved coloration and added functional properties [

14]. Consequently, exploring

P. americana berries as food or ingredient in multifunctional formulations (spanning the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic sectors) represents a promising and timely opportunity for health-promoting product development.

In this work, we present the first comprehensive evaluation of the nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and antioxidant activity of P. americana berries grown in Portugal. Besides analyzing their nutritional, mineral, fatty acid, and vitamin E profiles, the phytochemical characterization included the quantification of total phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins. Antioxidant capacity was determined by DPPH and FRAP assays, and hemolytic activity was evaluated to assess potential cytotoxicity.

2. Results

2.1. Nutritional Composition

The proximal analysis of the

P. americana berries is presented in

Table 1. The previously lyophilized berries exhibited a residual moisture of 8.42 ± 0.37 g/ 100 g dw. Carbohydrates (67.31 ± 0.61 g/ 100 g dw) were the major macronutrient, followed by fat (14.07 ± 0.53 g/ 100 g dw), crude protein (10.71 ± 0.18 g/ 100 g dw), and ash (7.90 ± 0.21 g/ 100 g dw). Among carbohydrates, total dietary fiber reached 35.12 ± 2.19 g/ 100 g dw, mostly in the insoluble fraction (23.18 ± 0.85 g/ 100 g dw).

The nutritional profile resulted in an energy value of 368.53 ± 1.51 kcal/ 100 g dw.

2.2. Mineral Profile

The mineral composition of

P. americana berries is summarized in

Table 2, which is structured in three horizontal sections to distinguish macro (mg/ g), micro (µg/ g), trace (µg/ g), and ultra trace (ng/ g) elements, providing a clear overview of the mineral composition. Potassium was the predominant macro element (21.63 ± 0.28 mg/ g dw), followed by magnesium (1.69 ± 0.12 mg/ g dw) and calcium (1.15 ± 0.07 mg/ g dw). Essential trace elements such as iron (87.15 ± 11.63 µg/ g dw), manganese (13.75 ± 0.15 µg/ g dw), zinc (10.8 ± 0.3 µg/ g dw), and copper (4.33 ± 0.03 µg/ g dw) were also detected.

2.3. Fatty Acid Profile by GC-FID

The percentage of fatty acids of berries extracted oils from

P. americana berries was evaluated by GC-FID, and results presented in

Table 3.

A total of 17 fatty acids were identified. The lipid fraction was dominated by polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA, 67 ± 1%), mainly linoleic acid (C18:2n6c, 37 ± 1%) and α-linolenic acid (C18:3n3, 30 ± 1%), which represented two-thirds of the total FA pool. Oleic acid (C18:1n9c, 20 ± 1%) was the most abundant MUFA, while palmitic acid (C16:0, 9.5 ± 0.4%) dominated the SFA group, followed by stearic acid (C18:0, 2.3 ± 0.1%). Minor amounts of medium-chain FAs such as caprylic (C8:0) and capric acid (C10:0) were also detected.

2.4. Vitamin E Profile by HPLC-DAD-FLD

Among the 8 naturally occurring homologues (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol and α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocotrienol), only the vitamers α- and γ -tocopherol were detected (

Table 4). Their concentrations were 4.1 ± 0.5 mg/ 100 g dw and 2.7 ± 0.3 mg / 100 g dw, respectively, giving a total vitamin E content of 6.8 ± 0.4 mg/ 100 g dw. (4.1 ± 0.5 mg/ 100 g and 2.7 ± 0.3 mg/ 100 g, respectively).

2.5. Bioactive Compounds

The phenolic content was studied using various assays, including total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC) and total saponins content (TSC). Thus, identification, quantification and characterization of tannins and flavonoids were achieved by HPLC-DAD.

2.5.1. Total Phenolics, Flavonoids and Saponins Contents

The quantification of major bioactive classes (

Table 5) in the hydroalcoholic extracts supports the functional potential of

P. americana berries.

The hydroalcoholic extract exhibited a total phenolic content (TPC) of 91.0 ± 0.4 mg/ g extract and a total flavonoid content of (TFC) of 52.1 ± 7.0 mg/ g extract. Additionally, the extract contained substantial levels of total saponins (TSC) (63.4 ± 4.0 mg/ g).

2.5.2. Phenolic Profile by HPLC-DAD

Five major phenolic compounds were identified (

Table 6). Quercetin was the predominant compound (18.5 ± 0.3 mg/ g extract), followed by ellagic acid (14.9 ± 0.5 mg/ g extract), quercetin-3-

O-rutinoside (4.25 ± 0.05 mg/ g extract), gallic acid (1.37 ± 0.01 mg/ g extract), and catechin (0.88 ± 0.02 mg/ g extract).

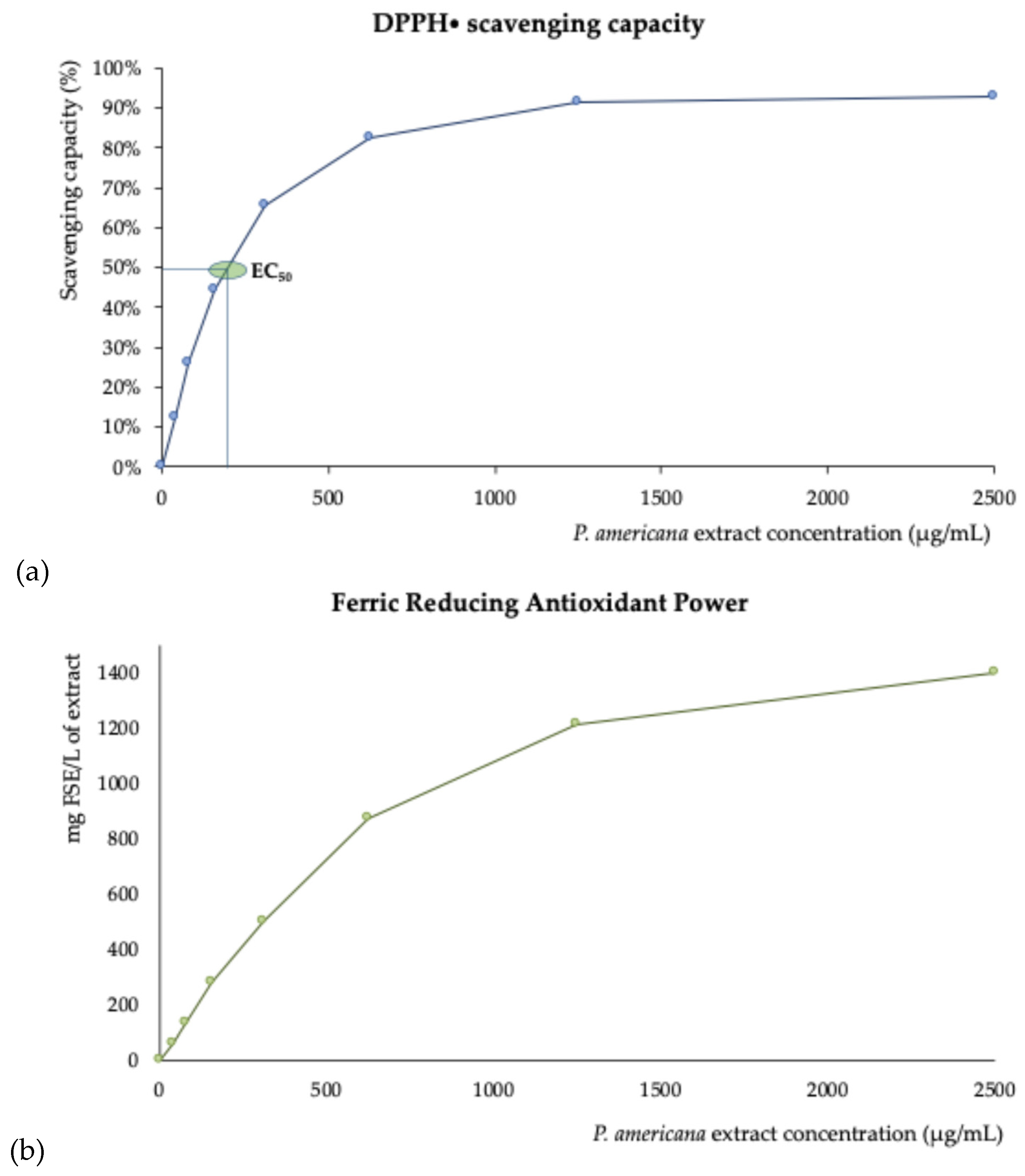

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of

P. americana berry extracts at different concentrations (39, 78, 156, 313, 625, 1250, and 2500 μg/ mL) was evaluated by the DPPH

• scavenging and FRAP inhibition assays and is presented in

Figure 1. Both assays revealed a clear dose-response relationship characterized by a sharp increase in antioxidant activity at low extract concentrations, followed by a progressive approach to a plateau as the concentration increased. For the DPPH

• assay, an EC

50 = 196 ± 8 μg/ mL extract was obtained.

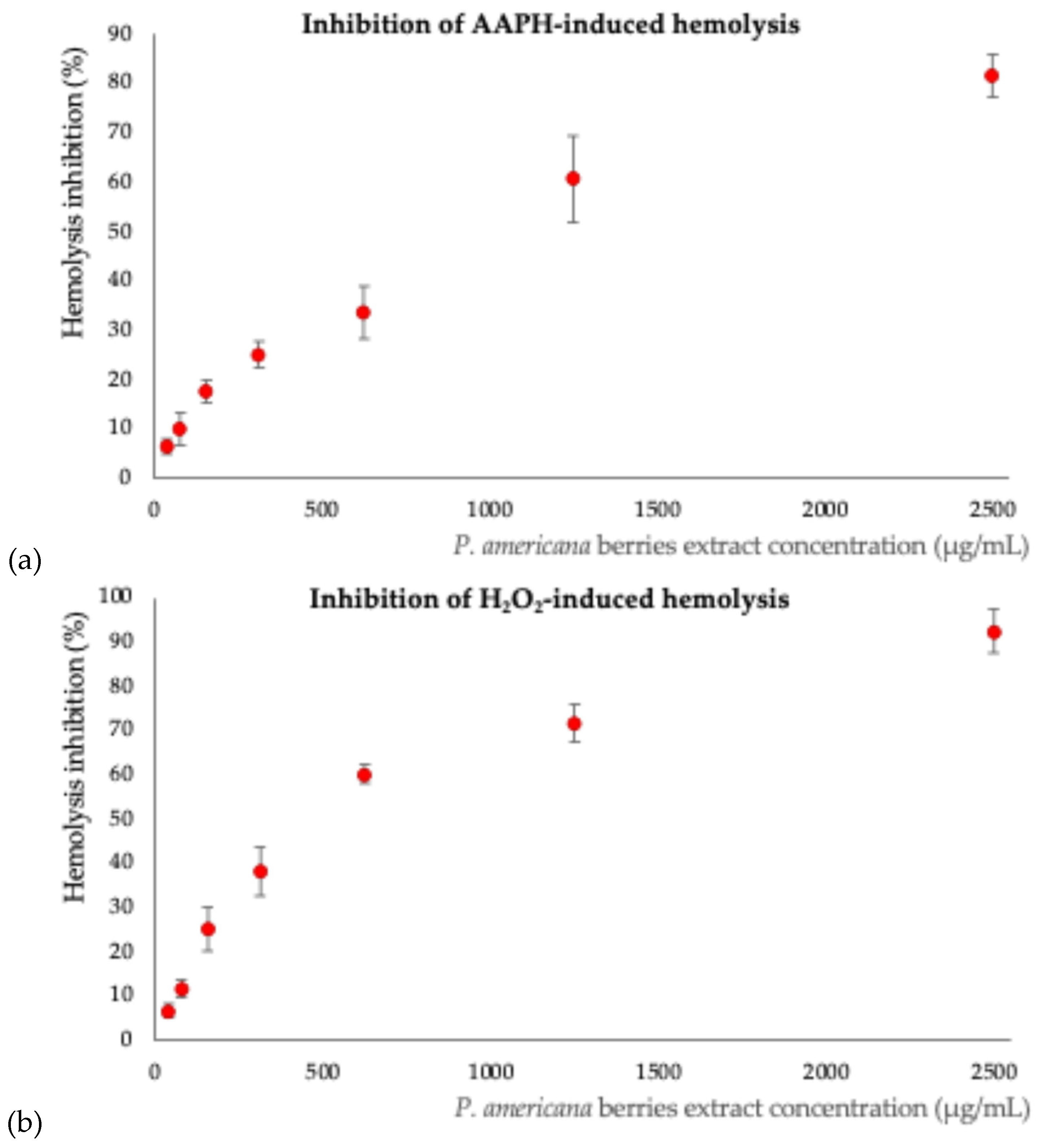

Additional and complementary mechanisms of antioxidant activity were also evaluated. For the first time, the ability of

P. americana berries to inhibit induced oxidative hemolysis in human erythrocytes was analyzed using two distinct pro-oxidant initiators: radical 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 2.

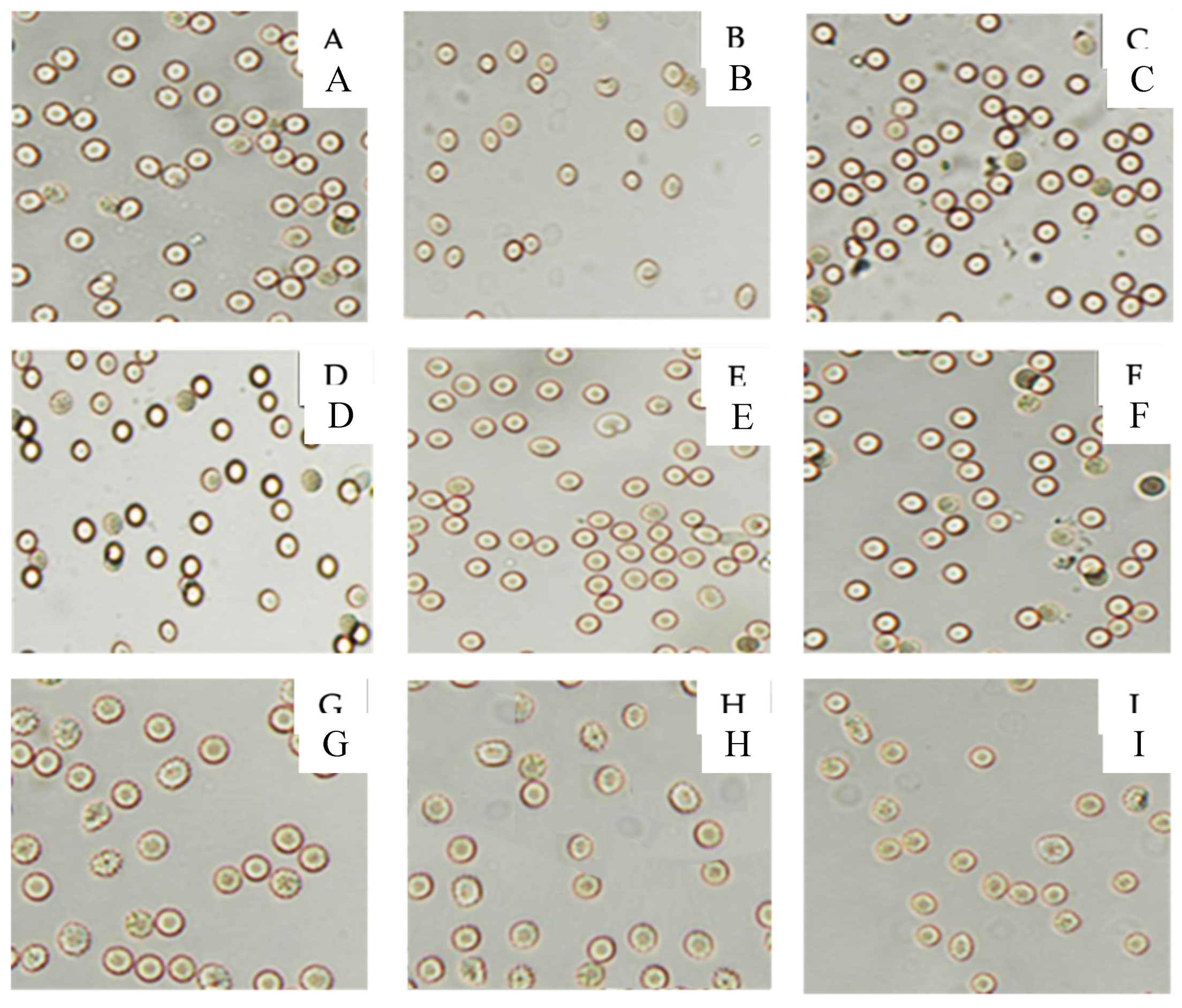

At the end of the incubation period, the hydroalcoholic extract of

P. americana berries showed a protective effect on erythrocyte membranes at all tested concentrations, reaching a maximum hemolysis inhibition value at the highest assayed extract concentration (2500 μg/ mL). After 2 hours of incubation, erythrocyte morphology was examined, revealing the presence of ghost cells (cell remnants lacking hemoglobin) (

Figure 3). The

P. americana berries extract demonstrated a concentration-dependent protective effect against erythrocyte lysis, with greater protection observed at higher concentrations.

Morphological analysis of erythrocytes confirmed the oxidative action of AAPH, as evidenced by the presence of ghost cells and a lower cell count in the positive control compared to the negative control.

3. Discussion

This study provides the first integrated assessment of the nutritional, mineral, phytochemical, and antioxidant characteristics of P. americana berries collected in Portugal. The overall results highlight a chemically rich and functionally promising berry matrix.

3.1. Nutritional Composition and Mineral Profile

P. americana berries presented a favorable macronutrient distribution, with high carbohydrate and dietary fiber contents. The nutritional profile resulted in an energy value of 368.53 ± 1.51 kcal/ 100 g dw, significantly lower than the values reported for other wild berries, including

Nitraria retusa (490.33 Kcal/ 100 g),

Ficus palmata (565.67 Kcal/ 100 g), and

Arbutus pavarii (790 Kcal/ 100g) [

15].

The ash content reflects a substantial mineral contribution. The P. americana berries contained relatively high quantities of potassium, and considerable amounts of many other nutritionally essential elements, including iron, zinc, manganese, and copper.

Iron content, in particular, exceeded levels commonly reported for fruits such as banana (7.39 µg/ g), mango (6.44 µg/ g), and grapes (7.10 µg/ g) [

16]. On the other hand, the presence of low but detectable levels of non-essential and toxic trace elements (Pb, Cd, Tl) is not unusual among wild berries. Lead (Pb), for instance, can be found in several other berries, including rose hips and blackberries, although its concentration is also dependent on environmental factors such as soil composition [

17].

3.2. Fatty Acids and Vitamin E Profiles

The lipid fraction was dominated by PUFA, particularly linoleic and α-linolenic acids. This is notable because wild berries seldom exhibit PUFA levels approaching two-thirds of total fatty acids. When compared to other invasive

Phytolacca species, such as

P. acinosa, similar FA classes were reported, but with higher ω-6/ω-3 ratios [

18]. Such differences may be related to geographical origin, cultivation environment, or ripeness stage at harvest.

The presence of α- and γ-tocopherols is important for the valorization of

P. americana berries, since α-tocopherol is recognized as the most biologically active form of vitamin E and γ -tocopherol showed health benefits beyond the normal nutritional effects and because vitamin E has significant applications in several industries, including food and cosmetics [

19].

3.3. Bioactive Compounds and Phenolic Profile

The high total phenolic and flavonoid contents, both groups well-known for their synergistic antioxidant effects and for their metal-chelating and membrane-stabilizing capacities [

20], are consistent with the phenolic profile revealed by HPLC-DAD.

The predominance of quercetin might explain the bioactivity observed in

P. americana berries, given the well-established antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and vasoprotective properties of this flavonoid and its glycosides [

21].

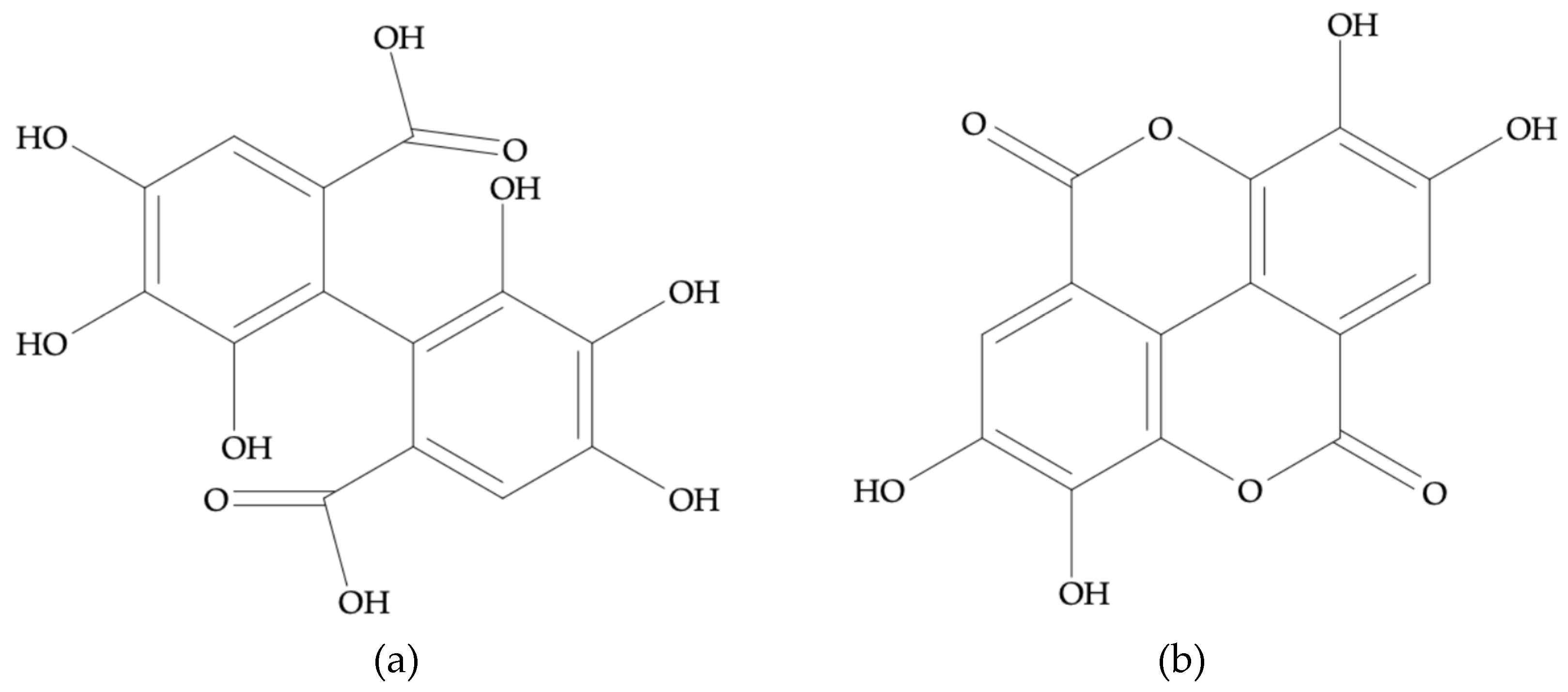

The detection of ellagic acid is particularly noteworthy. Although this polyphenol is widely distributed in berries, it has not been previously reported in

P. americana. Ellagic acid arises predominantly from the hydrolysis of ellagitannins and is structurally defined as a dimeric gallic acid derivative, as it constitutes a dilactone of hexahydroxydiphenic acid (

Figure 4).

Its presence in relevant concentrations (14.9 ± 0.5 mg/ g extract) represents a significant opportunity for valorizing

P. americana, considering its broad spectrum of biological activities, including antioxidant, antitumoral, anti-inflammatory, and antimutagenic properties, besides contributing to regulate specific cell signaling pathways that prevent or mitigate the progression of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, and cancer [

22].

The detection of quercetin-3-

O-rutinoside (rutin) at moderate levels (4.25 ± 0.05 mg/ g extract) further supports the functional potential of

P. americana berries. Rutin is recognized for its radical scavenging capacity, metal chelation activity, and membrane stabilizing effects [

23].

Gallic acid (1.37 ± 0.01 mg/ g extract) and catechin (0.88 ± 0.02 mg/ g extract), although present at lower concentrations, remain relevant due to their well-documented bioactivities. Gallic acid exhibits strong antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [

24], whereas catechin is a key contributor to radical-scavenging activity in berry matrices and is linked to cardioprotective effects [

25]. Their presence reinforces the indication that

P. americana berries contain both hydrolyzable tannins and flavan-3-ols, contributing to the antioxidant response attributed to this species.

Saponin levels were also considerable, aligning with previous reports of the genus. Although they are not major radical scavengers, their membrane-active and anti-inflammatory behavior can enhance the overall bioactivity of

P. americana [

26]. On the other hand, their presence also relates to the known toxicity of pokeweed berries, which can, however, be reduced by appropriate processing (e.g., cooking or parboiling) [

4].

In general, the predominance of ellagic acid and quercetin derivatives, and the coexistence of high phenolic, flavonoid, and saponin contents, highlight P. americana berries as a promising natural source of bioactive molecules with potential applications in functional foods, nutraceuticals, and health-promoting formulations.

3.4. Antioxidant Behavior

The measured antioxidant response is consistent with the phenolic composition of the berries, particularly the high levels of ellagic acid and quercetin derivatives, supporting the coherence between chemical composition and functional activity., indicating lower activity than previously reported for methanolic extracts of

P. americana berries [

27].

The exponential dose-response curves obtained in DPPH

• and FRAP assays confirm potent antioxidant properties even at low extract concentrations. The rapid increase in activity at low doses reflects the high reactivity of dominant phenolics such as quercetin and ellagic acid. The plateau observed at higher concentrations is characteristic of saturation kinetics, where most available radicals are already neutralized. The EC₅₀ obtained in DPPH

• indicates moderate activity relative to methanolic extracts reported previously, highlighting the influence of extraction solvent on phenolic recovery [

28].

This study demonstrated that the use of erythrocytes to evaluate the antioxidant activity of

P. americana berries offers significant advantages. Erythrocytes lack cytoplasmic organelles and have inadequate repair and biosynthetic capabilities, making them highly susceptible to oxidative damage under stress conditions [

29], despite containing endogenous antioxidants such as glutathione, α-tocopherol, and ascorbate. When reactive oxygen species are produced in excess, or when endogenous antioxidant defenses are compromised, erythrocytes experience oxidative stress that can damage membrane lipids and hemoglobin, ultimately leading to hemolysis [

30].

Given their role as oxygen carriers and their high concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, erythrocytes represent a primary target for free radical attack [

31]. Our results show that the extracts protected erythrocytes in a significant and dose-dependent manner.

P. americana berries demonstrated a protective effect at all concentrations tested, with a maximal hemolysis inhibition value at 2500 μg/ mL.

Moreover, the antioxidant behavior observed in erythrocytes suggests that the phenolic constituents of

P. americana berries may exert protective effects beyond direct radical scavenging. Compounds such as quercetin and ellagic acid have been reported to modulate endogenous defense pathways, including Nrf2-associated cytoprotective responses, which could contribute to the broader cellular resilience observed under oxidative stress. The extract’s ability to limit hemolysis triggered by two mechanistically distinct oxidizing agents (peroxyl radicals from AAPH and reactive oxygen species generated from H₂O₂) further indicates a multifunctional mode of action that may involve both membrane stabilization and enhancement of intracellular antioxidant capacity [

32].

Overall, the demonstrated antioxidant activity, particularly in erythrocytes, provides preliminary evidence that P. americana phenolics remain effective in a biological environment, supporting their translational value into nutraceutical applications. Future investigations should evaluate the bioaccessibility and metabolic stability of the dominant phenolics, as well as potential synergistic effects among extract components, to better define their contribution to the overall antioxidant profile. In addition, establishing structure–activity relationships may help identify the phenolic subclasses primarily responsible for the protective effects and guide optimization of extraction procedures for standardized applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material and Sample Preparation

The present study was conducted on berries of Phytolacca americana L. (pokeweed). The fruits were manually harvested on the northern coast of Portugal, municipality of Amarante (41º 13’ 1’’ N, 8º 4’ 11’’ W) in August 2022. During the harvesting process, several factors were considered, including appropriate stage of development, harvest region, berries ripeness, and exposure to solar radiation to ensure a representative sample. After, sample was stored in bottles at -80 ºC, and subsequently lyophilized (Telstar Cryodos-80 Terrassa, Barcelona, Spain). After lyophilization, the sample was ground in a mill (Grindomix GM200, Rech, Germany). All determinations were carried out in triplicate.

4.2. Nutritional Analysis

Initially, pokeweed berries were measured for moisture content using an infrared balance (Scaltec model SMO01, Scaltec Instruments, Heiligenstadt, Germany) (AOAC, 925.09). Ash content was measured after incineration at 500 ºC (AOAC, 935.42). Total lipids were measured using the Soxhlet procedure (AOAC, 989.05), and crude protein was measured using the Kjeldahl methodology (AOAC, 991.02). Total and insoluble fiber content was obtained using an enzymatic-gravimetric technique [

33]. Thus, soluble fiber and total carbohydrates were measured by their differential. The results were expressed in grams per 100 grams of dry weight (dw). The energy value was determined as follows: Energy value (kcal/100 g) equals (g protein × 4) + (g fat × 9) + (g carbs × 4) + (g fiber × 2) [

34].

4.3. Macro and Trace Elements Composition

Mineral analysis was performed according to the procedure described by Pinto et al. [

35]. Firstly, about 250 mg of sample was digested in an MLS-1200 Mega microwave digestion machine with an HPR-1000/10 S rotor (Milestone, Sorisole, Italy) using 65% nitric acid and 30% hydrogen peroxide solutions. After digestion, the resulting solution was diluted with 25 mL of ultrapure water. The macro and trace element contents were measured using a Perkin Elmer 3100 flame (air-acetylene) atomic absorption spectrometer (Überlingen, Germany). Calibration standards were obtained by diluting standard stock solutions containing 1000 mg/L of Ca, Na, Mg, Fe, or K. The elemental analysis was performed using an iCAP™ Q ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Calibration standards ranging from 0.5-200 µg/L were derived using the commercial 10 mg/L PlasmaCAL SCP-33-MS multi-element standard solution. AccuTrace

TM ICP MS-200.8-IS-1 solution (100 mg/L of Sc, Y, In, Tb, and Bi) was suitably diluted to provide an Internal Standards (IS) solution with a concentration of 100 µg/L. Elements observed were 7Li, 9Be, 11B, 27Al, 48Ti, 51V, 52Cr, 55Mn, 59Co, 60Ni, 65Cu, 66Zn, 75As, 82Se, 85Rb, 88Sr, 90Zr, 98Mo, 111Cd, 118Sn, 121S, 133Cs, 137Ba, 182W, 208Pb, and 209Bi. The data were collected in triplicate and expressed in dry weight (dw).

4.4. Lipidic Fraction Extraction

The lipidic fraction of pokeweed berries was extracted following the procedure established by Alves et al. [

36], with a few adjustments. In short, 75 μL of 0.1% (w/v) BHT, 50 μL of tocol (internal standard, 0.1 mg/mL), and 1 mL of 100% ethanol were mixed with ~150 mg of sample. The solution was homogenized for 30 minutes using an orbital vortex mixer (VV3, VWR International, Darmstadt, Germany). Next, 2 mL of n-hexane (HPLC grade) was added followed by a homogenization for another 30 minutes. After centrifugation (5000 rpm for 5 min) using a Heraeus Labofuge A (Hanau, Germany), the supernatant was gathered and stored. Then, after 30 minutes of re-extraction with 2 mL of n-hexane, the residue was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 5000 rpm. After that, the supernatant was gathered and combined with the earlier extract. After adding enough anhydrous sodium sulphate (Na

2SO

4), the solution was centrifuged for five minutes at 5000 rpm. After being evaporated to dryness, the supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of solvent and injected into an HPLC-DAD-FLD (high-performance liquid chromatography connected to a diode array detector and fluorescence detector) system for assessment of the vitamin E profile.

4.4.1. Vitamin E Profile by HPLC-DAD-FLD

The vitamin E profile of lipid fractions was determined using HPLC-DAD-FLD, following Alves et al. approach [

36]. An HPLC system (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) with an MD-2015 multiwavelength diode array detector (DAD) connected to an FP-2020 fluorescence detector (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) set up for excitation at 290 nm and emission at 330 nm was used for the chromatographic analysis. The compounds were separated chromatographically using a SupelcosilTM LC-SI normal phase column (75 mm × 3.0 mm, 3.0 µm) (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The eluent used was 1.2% 1,4-dioxane in n-hexane (HPLC grade), with a flow rate of 0.600 mL/min. All vitamers were identified by comparing their retention times to those of standards (α, β, γ, δ-tocopherols and α, β, γ, δ-tocotrienols) using UV spectra. Quantitative determination was obtained by converting fluorescence signals to concentration units using calibration curves based on commercial standards and the internal standard approach. The results were presented as mg per 100 g of sample (dry weight).

4.4.2. Fatty Acid Profile

The fatty acid profile of the pokeweed berries was determined from their methyl esters, obtained according to ISO 12966-2017 [

37], using a gas chromatograph coupled with

flame ionization detector (GC-FID). For the analysis, it was used a gas chromatograph GC-2010 Plus (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with an automatic sampler and a split/splitless auto injector (AOC-20i Shimadzu) operating with a 50:1 split ratio at 250 °C (injection), a CP-Sil 88 silica capillary column 50.0 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter and 0.20 µm film thickness from Varian (Middelburg, The Netherlands) and a Flame Ionization Detector (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) at 270 °C. Helium (3.0 mL/min) was used as carrier gas and the injection volume was 1.0 µL. Analyses were performed using the following programmed temperature: 120 °C held for 5 min, 2 °C/min at 160 °C held for 15 min and 2 °C/min at 220 °C held for 10 min. Relative peak areas were used to examine the data after the FA methyl esters were identified by comparison with a standard combination (FAME 37, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The relative proportion of total FA was used to express the FA results.

4.5. Bioactive Contents and Antioxidant Activity

4.5.1. Extracts

Powered berries (~0.5 g) were extracted with 50 mL of a hydroalcoholic solution (50:50 v/v) for one hour, on a stirring (600 rpm) plate with controlled temperature (40 °C). The extracts were filtered were collected and filtered through a PTFE syringe filter of 0.2 µm and kept at -20 °C for later evaluation of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity.

4.5.2. Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content of the hydroalcoholic pokeweed berries extract was determined by Folin-Ciocalteu method with minor modifications [

38]. In brief, 30 μL of extract was combined with 150 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1:10) and 120 μL of Na

2CO

3 aqueous solution (7.5%, m/v). The mixture was kept at 45 °C for 15 min; followed by 30 min of incubation without the presence of light at room temperature. A Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to obtain absorbance measurements (765 nm). The amount of total phenolics was calculated using a gallic acid calibration curve, and the total phenolic content was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per gram extract (mg GAE/ g extract) of dry weight (dw).

4.5.3. Total Flavonoids Content

The total flavonoids content was determined using a colorimetric method as previously reported by Costa et al. [

39]. First, 1 mL of sample extract was mixed with 300 µL of 5% sodium nitrite (NaNO

2) in 4 mL of distilled water to create a solution. 300 µL of 10% aluminum chloride (AlCl

3) was added after 5 minutes at room temperature. One minute later, 2 mL of sodium hydroxide (NaOH 1M) and 2.4 mL of distilled water were added to the mixture. A standard curve was plotted using catechin as standard. A Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 510 nm. Results were expressed as mg catechin equivalents (CE) per gram of dry weight (dw).

4.5.4. Total Saponin Content

The total saponin content followed the experimental procedure described by Helaly et al. [

40], with slight modifications. Briefly, hydroalcoholic extract was mixed with 0.5 mL of vanillin (8%) in ethanol and 5.0 mL of 72% sulfuric acid (H

2SO

4) and stored in an ice bath. After homogenization the mixture was placed in a thermostatic bath at 60 °C for 20 minutes. Subsequently, the solution was cooled in the same ice bath and then spectrophotometric readings were taken at 544 nm using a Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Merck saponin was used to prepare the calibration curve. Results were expressed as mg saponin equivalents (SE) per gram of dry weight (dw).

4.5.5. Individual Phenolics Profile

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of individual phenolics was performed by employing a direct injection method. The chromatographic analysis was performed using an HPLC system equipped with an AS-4050 autosampler, a PU-4180 pump and a MD-4010 multiwavelength diode array detector (DAD) of the same brand. The following fused-core stationary-phase column was used: ThermoScientificHypersil Gold C18 (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 3 μm). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/ min and the injection volume was 10 μL. The gradient program for the mobile phase composed of water containing 0.5% acetic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) was as follows: 0-10 min: 0% B (to ensure the reproducibility of the analysis), 10-28 min: 0 to 25% B, 28-30 min: 25% B, 30-35 min: 25 to 50% B, 35-40 min 50 to 80% B, 40-45 min: 80 to 0% B. Detection was performed in the near UV region, from 200 to 400 nm. Rutin, quercetin, and ellagic acid were quantified using peak areas at 254 nm, while gallic acid and catechin were quantified using peak areas at 280 nm.

Method Validation

The following parameters were evaluated: linearity, precision, detection limit (LOD) and quantification limit (LOQ). The LOD and LOQ were determined at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3 and 10, respectively. Linear calibration curve for standard was constructed over six calibration levels ranging from 1 µg/ L to 1000 µg/ L, each injected in triplicate. The precision was evaluated in terms of repeatability (within-day relative standard deviation, R.S.D.) and in terms of intermediate precision (between-day R.S.D.) at the same concentration level in three non-consecutive days (results displayed in

Table 7). The results demonstrated good linearity within the tested concentrations, with the tested concentrations, with determinations coefficients (

R2) above 0.99 for all analytes.

4.5.6. Antioxidant Activity

4.5.6.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging

The DPPH scavenging ability of the different extracts was determined according to the method validated by Costa et al. [

39], with modifications. Briefly, 30 μL of Trolox standard (562 μg/ L)/blank solution or different extract concentrations (39-2500 μg/ mL) were mixed with 270 μL of the DPPH

• solution (6.1 × 10

−5 M) and left to stand for 60 min protected from light. Absorbance was measured using a Synergy HT Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at 515 nm. The scavenging capacity (SC) was calculated as the percentage of DPPH discoloration using the equation % SC = [(

ADPPH −

AS)/

ADPPH] × 100, where

AS is the absorbance of the solution mixed with the extract and

ADPPH is the absorbance of the DPPH solution. Trolox was used to obtain the standard calibration curve (2.5-1000 μg/ mL, R

2 > 0.996). The extract concentration providing 50% of SC (EC

50) was calculated from the graph of SC percentage against extract concentration.

4.5.6.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

The FRAP assay was performed according to a previously applied methodology [

39]. Concisely, 90 μL of diluted extract (1:10) were mixed with 270 μL of distilled water and 2.7 mL of the FRAP solution (containing 0.3 M acetate buffer, 10 mM TPTZ solution, and 20 mM of ferric chloride). After homogenization, the mixture was kept for 30 min at 37 °C protected from light. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm. A calibration curve was prepared with ferrous sulfate (50–450 mg/ L, r = 0.9998) and ferric reducing antioxidant power was expressed as mg of ferrous sulfate equivalents (FSE)/ L of extract.

4.5.6.3. Effect on Erythrocyte Oxidative-Induced Hemolysis.

The extracts prepared in

Section 4.5.1 were evaporated under a nitrogen stream, respectively, and the residue was resuspended in PBS at different concentrations: 2500, 1250, 625, 313, 156, 78, and 39 μg/ mL. To promote hemolysis, AAPH or H

2O

2 were used as oxidants. Each set of tests included both negative (erythrocytes in PBS) and positive (erythrocytes in PBS with AAPH or H

2O

2) as control. To assess hemolysis inhibition, the erythrocyte solution was incubated with an extract aliquot at a final concentration of 60 mM AAPH or 1mM H

2O

2, with a hematocrit of 2.0%. To suppress catalase activity, 1 mM of sodium azide was added to the H

2O

2 test solution. Incubation was conducted at 37 °C for 2 hours with gentle shaking. This approach tested individual extracts against each initiator radical (AAPH or H

2O

2).

Hemolysis level was assessed spectrophotometrically, according to Costa et al. [

41]. Following a two-hour incubation period, an aliquot of the erythrocyte solution was diluted with twenty volumes of PBS and centrifuged for ten minutes at 1200 g. At 540 nm, the supernatant’s absorbance (A) was measured. After centrifuging an aliquot of erythrocyte suspension that had previously been treated with 20 liters of ice-cold distilled water, the absorption (B), which corresponds to a full hemolysis, was determined. Next, the hemolysis percentage (A/B x 100) was determined. The hemolysis of the positive control tube was taken into consideration as 0% of inhibition when calculating the percentage of hemolysis inhibition. Every control and sample test was examined three times. Thus, erythrocyte morphologic changes associated with hemolysis were evaluated. For that, aliquots (50 μL) of incubated erythrocyte suspensions with AAPH (in the presence or absence of

P. americana berries extracts) were diluted (1:10) and disposed of on a slide with a coverslip, for optical microscopy evaluation.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the chemical composition and antioxidant properties of Phytolacca americana berries, revealing a complex matrix rich in nutrients, minerals, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α- and δ-tocopherol, phenolics, flavonoids, and saponins. The predominance of quercetin and ellagic acid, together with substantial total phenolic and flavonoid contents, aligns with the strong antioxidant activities observed in DPPH•, FRAP and hemolysis inhibition assays. These findings suggest that P. americana berries possess meaningful functional potential and may represent a valuable source of health-relevant bioactive compounds. Nevertheless, the detection of considerable saponin levels and the well-documented toxicity of pokeweed berries underscore the importance of appropriate processing and cautious consideration of safety in future applications. Overall, the results support the potential of P. americana as a promising candidate for nutraceutical development and for sustainable valorization of invasive plant species, while also emphasizing the need for further studies addressing bioaccessibility, in vivo efficacy, and safe incorporation into food systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.V., and M.B.P.P.O.; methodology, L.E.S., D.M.F., T.F.S., S.M., E.C., R.A., E.M.C., and A.A.; validation, C.S.G.P.P., J.C.M.B., E.C., M.B.P.P.O., and A.F.V.; formal analysis, C.S.G.P.P., M.C.B., and A.A.; investigation, C.S.G.P.P., L.E.S., T.F.S., S.M., E.C., E.M.C., and A.F.V.; writing - original draft preparation, C.S.G.P.P., J.C.M.B., and A.FV.; writing - review and editing, A.F.V., M.C.B., E.C., J.C.M.B., and M.B.P.P.O.; supervision, M.B.P.P.O. and A.F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from the PT national funds (FCT/MECI, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação, Ciência e Inovação) through the project UID/50006-Laboratório Associado para a Química Verde- Tecnologias e Processos Limpos (LAQV-REQUIMTE), and through the projects UID/00690/2025 (10.54499/UID/00690/2025) and UID/PRR/00690/2025 - Centro de Investigação de Montanha (CIMO), and LA/P/0007/2020 (10.54499/LA/P/0007/2020) - Associate Laboratory for Sustainability and Technology in Mountain Regions (SusTEC). C.S.G.P.P. thanks FCT for her PhD grant (2021.09490.BD); L.E.S. is grateful to LAQV-Tecnologias e Processos Limpos-UIDB/50006/2020 for her grant (REQUIMTE 2023-49); J.C.M.B. acknowledges FCT for his contract (FCT-Tenure: 2023.11031.TENURE.023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Follak, S.; Schwarz, M.; Essl, F. Notes on the Occurrence of Phytolacca americana L. in Crop Fields and Its Potential Agricultural Impact. Bioinvasions Rec 2022, 11, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmel, J. Differential Effects of American Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) Invasion on Ground-Dwelling Forest Arthropods in Southwest Germany. Biol Invasions 2020, 22, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleșcu, I.D.; Crivei, I.C.; Balint, A.B.; Arsenoaia, V.N.; Robu, A.D.; Stoica, F.; Rațu, R.N. Valorization of Betalain Pigments Extracted from Phytolacca americana L. Berries as Natural Colorant in Cheese Formulation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, J.M.; Michalska, K.; Szuwarzyński, M.; Mazur, T.; Cholewa-Wójcik, A.; Kopeć, M.; Juszczak, L.; Kamińska, I.; Nowak, N.; Jamróz, E. Phytolacca americana Extract as a Quality-Enhancing Factor for Biodegradable Double-Layered Films Based on Furcellaran and Gelatin – Property Assessment. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 279, 135155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailly, C. Medicinal Properties and Anti-Inflammatory Components of Phytolacca (Shanglu). Digital Chinese Medicine 2021, 4, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.; Yáñez-Sánchez, M.; de la Fuente, F.; Ortega, A.; Figueroa-Carvajal, A.; Gangitano, D.; Scholz-Wagenknecht, O. Toxic and Hallucinogenic Plants of Southern Chile of Forensic Interest: A Review. Plants 2025, 14, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, L.F.; Brinza, I.; Gatea, F.; Badea, G.I.; Vamanu, E.; Oancea, S.; Hritcu, L. Enhancement of Cognitive Benefits and Anti-Anxiety Effects of Phytolacca americana Fruits in a Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Model of Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunjaruen, A.; Luecha, P.; Taratima, W. Micropropagation of Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana L.) and Comparison of Phenolic, Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity between Pokeweed Callus and Other Parts. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.Y.; Han, K.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Park, S.M.; Kim, S.; Lee, B.S.; Min, B.S.; Yoon, S.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, T.W. Subchronic Toxicity Assessment of Phytolacca americana L. (Phytolaccaceae) in F344 Rats. Nat Prod Commun 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, B.G.; Ramos-Milaré, Á.C.F.H.; Pereira, M.B.; Brustolin, A.Á.; Montaholi, D.C.; Lera-Nonose, D.S.S.L.; Negri, M.; de Lima Scodro, R.B.; Teixeira, J.J.V.; Lonardoni, M.V.C. Plants of the Phytolaccaceae Family with Antimicrobial Activity: A Systematic Review. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36, 3505–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikiran, G.; Raju, A.B.; Venugopal, Y. Phytolacca americana: A Review. Int J Res Pharm Biomed Sci 2011, 3, 942–946. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.C.; Wang, Q.H.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.; Kuang, H.X. Research Progress on Chemical Constituents, Pharmacological Effects, and Clinical Applications of Phytolaccae Radix. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs 2014, 45, 2722–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamar, H.A.; Hatem, N.A.; Dapson, R.W. Betacyanins Are Plant-Based Dyes with Potential as Histological Stains. Biotech Histochem 2022, 97, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Xjung, S.Y. Technical Approaches of a Natural Dye Extracted from Phytolacca americana L.-Berries with Chemical Mordants. Technol Health Care 2014, 22, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, A.K.; Al-Rowaily, S.L.; Faisal, M.; Alatar, A.A.; El-Bana, M.I.; Assaeed, A.M. Nutritive Value and Antioxidant Activity of Some Edible Wild Fruits in the Middle East. J Med Plants Res 2013, 7, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, T. An Assessment of Mineral Contents in Fruits. Prithvi Academic Journal 2023, 6, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Amin, M.R.; Khan, F.; Hassan, M.T.; Hasan, M.M.; Hanif, M.A.; Salam, S.M.A. Heavy Metal Contamination in Fruits and Human Health Risk Assessment in Northwestern Bangladesh. J Food Compos Anal 2025, 148, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblea, M.A.; Marian, M.C.; Aydin, T. A Comprehensive Review of the Invasive Species Phytolacca acinosa Roxb. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Chojnacka, A.; Górnicka, M. Tocopherols and Tocotrienols—Bioactive Dietary Compounds; What Is Certain, What Is Doubt? Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, C.; Nascimento, A.; Meghwar, P.; Lisboa, H.; Aires, A.; Rosa, E.; Ferreira, L.; Barros, A.N. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Edible Flowers: Insights from Synergistic Effects and Multivariate Analysis. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmannová, A.; Bojňanská, T.; Musilová, J.; Lidiková, J.; Cifrová, M. Quercetin as One of the Most Abundant Represented Biological Valuable Plant Components with Remarkable Chemoprotective Effects - A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, F.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, C. Ellagic Acid from Hull Blackberries: Extraction, Purification, and Potential Anticancer Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, H.; Wagner, A.; Alharbi, C.; Alshebremi, H.O.A.; Babiker, M.; Rahmani, A.Y.; Obaid, H.; Alharbi, A.; Alshebremi, M.; Yousif Babiker, A.; et al. The Role of Quercetin, a Flavonoid in the Management of Pathogenesis Through Regulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Biological Activities. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidi, M.; Liñán-Atero, R.; Tarahi, M.; Christodoulou, M.C.; Aghababaei, F. The Potential Health Benefits of Gallic Acid: Therapeutic and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Catechins: Protective Mechanism of Antioxidant Stress in Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1144878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwińska, A.A.; Tomiczak, K. Advancing the Potential of Polyscias fruticosa as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: Biotechnological and Pharmacological Perspectives. Molecules 2025, 30, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheleva-Dimitrova, D.Z. Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Properties of Amorpha fruticosa L. and Phytolacca americana L. Pharmacogn Mag 2013, 9, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z.; Subbiah, V.; Suleria, H.A.R. Extraction and Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Antioxidant Activities. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022, 29, 81112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.D.; Gagliardo, R.P.; Montalbano, A.M.; Profita, M. Overview of the Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress: Impact in Inflammation of the Airway Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Sousa, C.; Costa, C. Oxidative Stress, Antioxidants and Biomarkers: Appreciation for Analysis Methods for Health Promotion. Int Aca Res J Int Med Pub Heath 2023, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Daraghmeh, D.N.; Karaman, R. The Redox Process in Red Blood Cells: Balancing Oxidants and Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Samarasinghe, A. How to Assess Antioxidant Activity? Advances, Limitations, and Applications of in Vitro, in Vivo, and Ex Vivo Approaches. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2025, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL. AOAC 2012, 19st ed.

- Regulation - 1169/2011 - EN - Food Information to Consumers Regulation - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/1169/oj/eng (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Pinto, E.; Almeida, A.A.; Aguiar, A.A.R.M.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Changes in Macrominerals, Trace Elements and Pigments Content during Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.) Growth: Influence of Soil Composition. Food Chem 2014, 152, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.C.; Casal, S.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Determination of Vitamin e in Coffee Beans by HPLC Using a Micro-Extraction Method. Food Sci Technol Int 2009, 15, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 12966-2 Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters Part 2: Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids. ISO Standards 2017.

- Vinha, A.F.; Costa, A.S.G.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Pacheco, R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Chemical and Antioxidant Profiles of Acorn Tissues from Quercus Spp.: Potential as New Industrial Raw Materials. Ind Crops Prod 2016, 94, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.S.G.; Alves, R.C.; Vinha, A.F.; Barreira, S.V.P.; Nunes, M.A.; Cunha, L.M.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Optimization of Antioxidants Extraction from Coffee Silverskin, a Roasting by-Product, Having in View a Sustainable Process. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 53, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helaly, F.M.; Soliman, H.S.M.; Soheir, A.D.; Ahmed, A.A. Controlled Release of Migration of Molluscicidal Saponin from Different Types of Polymers Containing Calendula officinalis. Adv Poly Technol 2001, 20, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.S.G.; Alves, R.C.; Vinha, A.F.; Costa, E.; Costa, C.S.G.; Nunes, M.A.; Almeida, A.A.; Santos-Silva, A.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Nutritional, Chemical and Antioxidant/Pro-Oxidant Profiles of Silverskin, a Coffee Roasting By-Product. Food Chem 2018, 267, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).