2.1. The Basics

The present analysis builds upon the fundamental relationship introduced in [

7], which defines the Hubble parameter H(t) as the relative expansion rate of the Universe at cosmic time t after the Big Bang,

where a(t) denotes the cosmic scale factor.

Εquation (1) is claimed to be valid from Plack epoch. For the current epoch, the Hubble parameter may be well approximated by Equation (1) i.e.,

where

is the present age of the universe.

Solving Equation (1) yields a linear evolution of the scale factor with cosmic time,

As a consequence, any characteristic physical length scale R(t) in the Universe evolves according to Equation (4) :

where denotes an initial reference time and t the corresponding later epoch.

Following the Big Bang, any length scale generated at the Planck epoch may be assumed to originate at

, the Planck time. Setting this value in Equation (4) and taking into consideration that

, The physical radius of the Universe evolves linearly with cosmic time, as given by Equation (5) :

indicating a linear expansion with cosmic time.

This result, implied by Equations (5) and (6), indicates that the Universe expands without acceleration, with an effective expansion rate equal to the speed of light. Importantly, this “speed” refers to the growth of the cosmological length scale rather than to the local motion of matter through spacetime. In this sense, the expansion remains consistent with the principles of special relativity, which constrain local signal propagation but not metric expansion.

This behavior is consistent with the second Friedmann acceleration equation for a flat FLRW universe, which reduces in this case to Equation (6):

leading to the fundamental relationship for the total pressure (P) given by Equation (7)

:

We now consider the total energy content of the Universe, approximated as:

where ρ=ρ(t) represents the universe’s energy density and R is given by the relationship (5).

where ρ(t)\rho(t)ρ(t) represents the average cosmic energy density and R(t)

is given by Eq. (5).

The differentiation of Equation (8) and the application of the 3rd Friedmann energy equation lead to following relationship for the total energy rate (

:

A key result reported in Bartzis (2025) is that the rate of energy inflow into the expanding Universe exhibits a constant expectation value (ER) ,

Details of the derivation of Equations (9) and (10) are provided in [

7]

In summary, the set of equations presented above, constitutes a closed and self-consistent dynamical system. This system can be written in a form formally equivalent to the standard Friedmann equations for a spatially flat FLRW universe without an explicit cosmological constant, while adopting a different physical interpretation of the energy budget and its evolution. Although the field equations retain their standard Friedmann form, the underlying physical interpretation differs from ΛCDM due to the presence of a constant energy inflow and non-adiabatic energy exchange among cosmic components, leading in particular to modified early-universe behavior. This alternative perspective will be explored further in the following sections.

2.2. The Universe Composition Evolution

Unless otherwise stated, all quantities refer to spatial averages within a flat FLRW cosmology.

Recall that the total pressure

P is the sum of the partial pressures of its constituents, namely

where

m,

rad, and

de denote matter, radiation, and dark energy, respectively.

Following the state of the art, the corresponding equations of state , for the attractive gravity constituents are given by (e.g., [

8]):

In the present conceptual framework ([

7]), dark energy is treated as a perfect fluid :

Having defined the equations of state for each constituent, we may now examine the universe’s composition and its transformation.

Concerning the energy conservation per each constituent, energy exchange among the cosmic components is described phenomenologically through internal energy exchange terms, as expressed by Equations (13a) and (13b)

, while preserving local covariant conservation:

under the condition that :

The source term allows for internal energy exchange among constituents.

In cosmological modeling, the inclusion of an additional source term in the 3rd Friedmann equation has been widely employed to describe internal energy exchange among the different constituents of the Universe (e.g., [

9]). The standard adiabatic conservation law (i.e.,

assumes that each component (e.g., radiation, matter, or dark energy) evolves independently, without exchanging energy or particles. However, both theoretical and observational considerations motivate departures from this idealization. In the early universe, phenomena such as reheating and particle creation after inflation ([

10,

11]) require modeling energy transfer between fields, while in the late universe, interacting dark energy–dark matter scenarios have been proposed to alleviate the

coincidence problem—the question of why the energy densities of dark matter and dark energy are of the same order of magnitude today despite evolving differently[

12,

13]. Similarly, within the framework of nonequilibrium thermodynamics, source terms have been introduced to account for particle production or bulk viscous dissipation in the cosmic fluid [

14,

15]. In other words, the introduction of such a source term (

) provides a phenomenological and sometimes field-theoretic means to describe realistic, non-adiabatic cosmic evolution where internal energy exchange plays a role.

The volume-integrated version of Equation (13a) can be derived analogously to Equation (9)

, yielding Equation (14):

Where is the energy rate for the component i.

Dividing Equation (14) by Equation (9), we obtain Equation (15a)

:

The dimensionless parameters represent the fractional internal energy exchange rates among the cosmic components. obeying to constraint (15c).

We can define the corresponding density parameters:

In this case , if we take into consideration that under the present conceptual framework, ER is a constant and consequently E ~ t , the Equation (15a) can be rewritten:

Applying the individual equations of state (12) and the total pressure equation of state (7) to the equation (17), we obtain per constituent:

By adding Equations (18a)–(18c)

, we derive the relationship given by Equation (19a):

Taking into consideration that

we estimate

:

The differentiation of Equations (19a) and (19b) leads to the additional relationships:

In summary, the coupled system of Equations (18)–(20) provides a self-consistent frame for quantitatively investigating how the proposed conceptual model describes the temporal evolution of the universe’s individual components. In particular, this formulation allows one to follow the time dependence of the parameters, starting near the boundary of the Planck epoch and extending into later cosmological eras.

It should be emphasized, however, that such an analysis is subject to several inherent limitations. These include: (i) the scarcity and largely indirect nature of observational constraints on the very early universe; (ii) uncertainties associated with the modeling assumptions and parameterizations employed within the theoretical framework; and (iii) the sensitivity of the results to the choice of initial conditions, which may amplify small deviations when extrapolated from Planck-scale physics to cosmological times. Additional challenges arise from the possible breakdown of classical spacetime descriptions at ultra-high energies, as well as from degeneracies among competing cosmological models that can lead to similar late-time observables. [e.g., [

16,

17]).

In light of these considerations, the present study is deliberately restricted to a first-order approximation scheme. The aim is not to derive precise numerical predictions, but rather to obtain quantified estimates that reveal qualitative trends and to assess the extent to which the resulting behavior is consistent with the standard cosmological paradigm. Where additional empirical or theoretical input is required, the most relevant and currently established results available in the literature are employed.

For the purposes of the present analysis, the evolution of the universe is divided into three distinct eras: (a) the post-radiation era; (b) the radiation-dominated era; and (c) the intermediate transition era between radiation and matter domination.

2.2.1. The Universe Post-Radiation Era

Let us examine first, the post-radiation era when the radiation has become negligible compared to matter.

In this case. we can take for this analysis .

It is noted that the today’s universe is considered to be well within this the post-radiation era.

The approximate density parameters values for the present period

and

are taken as follows [

7] :

The equations (19), by setting

lead to constant values for both

and

i.e.,

In other words, an expanding, not accelerating universe entails nearly constant density parameters for both matter and dark energy, as long as radiation parameter remains negligible.

The above constant density parameters modify the terms in the Equations (18a) and (18c) for the post radiation era as follows :

Equations (23) allow for the estimation of both source terms :

We can write explicitly now, the energy rates for dark energy (

) and matter (

) starting from Equations (18a) and (18c) and incorporating the relationships (22) and (24) :

These relations represent the era when radiation can be considered negligible. They are significant for two main reasons:

They support the interpretation that, during this regime, vacuum energy manifests entirely as dark energy.

They indicate that matter draws its energy for existence and growth from dark energy, with a corresponding energy flow estimated to be roughly one-third of the incoming energy rate.

In other words, dark energy acts as the sustainable component that, on one hand, provides the energy necessary to maintain a non-accelerating expansion of the universe and, on the other, determines decisively the fate of matter as a whole.

Concerning consistency with relevant observations, the interpretation often depends on the theories used as bases. It could be quite useful to look such observations using the present conceptual framework as a basis in order to be clarified, to what degree there are agreements or contradictions. On the positive side for such an initiative, is that the present conceptual framework does not seem to face the cosmological constant Problem or the Hubble Tension Problem.

2.2.2. The Radiation-Dominated Era

It is noticed that in the very early universe, all relativistic species—photons, neutrinos, and any other light particles—are expected to form a nearly homogeneous radiation field. As the universe expanded and cooled, non-relativistic matter began to dominate. However, when considering the contemporary radiation density, we are in practice estimating only the cosmic microwave background (CMB) photons, since neutrinos, initially behaving as radiation, gradually transitioned to matter-like behavior, contributing to the matter-dominated era [

18].

Focusing on the very early universe i.e., when time is still scaled by the Planck time (

. the only attractive gravitational constituent can be classified as radiation. In this case, we can assume

and the Equations (19) yield:

It should be noted here that, if the present conceptual framework is valid, as we move from the present epoch toward the very early universe, the dark energy fraction shows a mild increase from 0.7 to 0.8, while the radiation fraction stays below a maximum of about 0.2 corresponding to Planck regime.

Feeding those values to the Equations (18) we end up with the following relationships for

:

In terms of energy rates , the ones for dark energy (

) and radiation (

), Equations (14) and (23) give :

These relations represent the epoch when matter is negligible. They are also significant since they support the interpretation that, during this regime, vacuum energy manifests as a mixture of repulsive dark energy and attractive radiation energy in analogy 6:1.

It is also interesting to note that looking at the Equations (27a) and (28), in both cases, nearly half of the dark energy is transferred to the attractive gravity constituents. This seems to happen at least when the dark energy rate remains nearly constant, i.e., when .

2.2.3. The Radiation – Matter Transition Era

The radiation–matter transition era represents the period during which all three cosmic components—radiation, matter, and dark energy—contribute non-negligibly to the total energy density.

In order to propose a simple but physically reasonable function for

, we adopt the following empirical relation, given by Equation (29):

For the estimation of parameter λ we will exploit the present knowledge concerning the time when

. This time has been estimated to be roughly

[

19].

Under the present conceptual frame , the Equations (19) give:

Substituting the above values into the Equation (29) we end up with the following value for λ :

The

is derived from Equations (19b) :

It should be emphasized that the above parametrization is not derived from first principles, but is introduced as a deliberately simplified and phenomenological representation of the transition era. At this stage, the objective is not to obtain a unique or exact solution, but rather to explore whether a deliberately simplified phenomenological description can capture the main qualitative features of the Universe’s compositional evolution. In this respect, Equation (29) satisfies several essential consistency requirements: (a) it qualitatively follows the expected monotonic growth of the matter density parameter during the radiation–matter transition; (b) in the limit of sufficiently large cosmic time, it correctly asymptotes to the constant values of parameter and given by Equations (22); (c) it yields equal values of parameter and at t≈51 kyrs, in agreement with the standard cosmological estimate for radiation–matter equality; and (d) with respect to the radiation density parameter , it is intended to apply only within the transition regime, where radiation remains dynamically significant. At later times, when becomes relatively negligible, its evolution is treated separately, as discussed in subsection 2.3. Alternative parametrizations satisfying the same consistency conditions are possible, but their detailed comparison lies beyond the scope of this first-order investigation.

An additional and independent consistency check of Equation (29) is provided by its implications for the thermal history of the Universe. When combined with the present formulation of energy exchange among cosmic components, this simplified parametrization leads to temperature estimates across major cosmological epochs that closely track widely accepted benchmark values, as summarized in

Table 1. This level of agreement, achieved without the introduction of additional free parameters or epoch-specific fine tuning, suggests that Equation (29), despite its phenomenological nature, captures essential features of the radiation–matter transition relevant for the thermal evolution of the Universe.

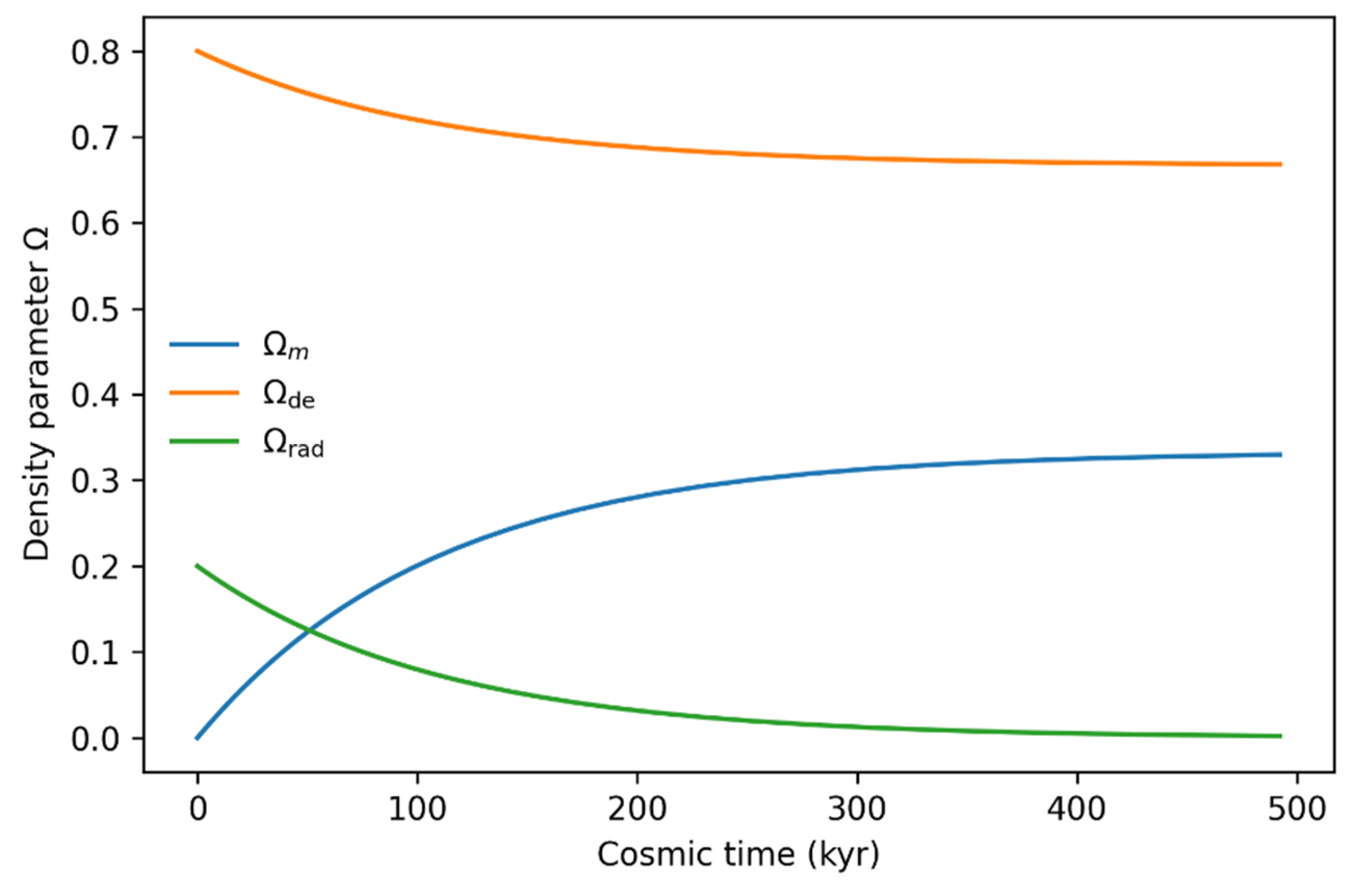

By adopting those relationships, we are able to produce a rough estimate of the individual constituent density parameters. The results are shown in

Figure 1.

The radiation density parameter decreases, becoming relatively insignificant roughly after 300 kyrs, a logical time, given that the radiation matter equality is set at 51 kyrs. After this period, the matter and dark energy are mutually adjusted to reach nearly steady state. The transition period seems to start after roughly 10kyrs. After this period , the dark energy starts gradually to be reduced reaching the steady state after 300kyrs.

Figure 1 shows that at early cosmic times, the radiation density parameter dominates and decreases rapidly with time, reflecting the strong dilution of relativistic components. The matter density parameter increases and approaches a quasi-constant value, indicating the transition to a matter-dominated regime. Dark energy remains the dominant component at late times, varying slowly compared to matter and radiation.

The radiation density parameter becoming relatively insignificant roughly after 300kyrs, a logical time, given that the radiation matter equality is set at 51kyrs. After this period, the matter and dark energy are mutually adjusted to reach nearly steady state. The transition period seems to start after roughly 10kyrs. After this period, the dark energy starts gradually to be reduced reaching the steady state after 300kyrs.

We can also estimate the internal energy exchange fraction (

) for each constituent (i), obeying to the equations (18):

The differentiation of Equation (32) yields Equation (34):

From Equations (20) we derive :

Then Equations (33) become :

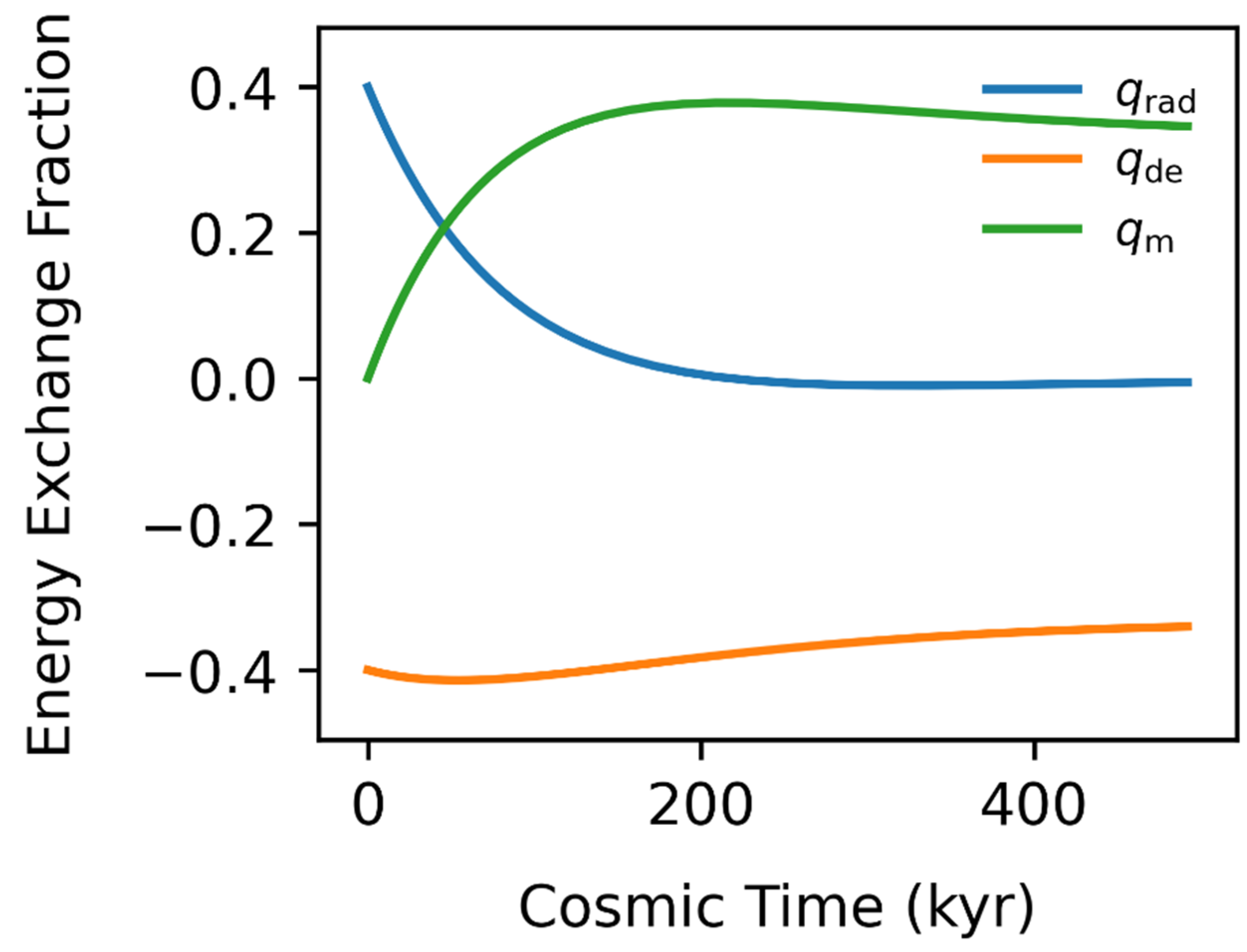

By adopting those relationships, we are able to produce a rough estimate of the individual energy exchange rate fractions individual constituent density parameters. The results are shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that at early cosmic times, the radiation exchange fraction dominates, reflecting the strong coupling of the radiation sector in the primordial Universe. As cosmic time increases, this contribution rapidly decreases, indicating a progressive decoupling of radiation from the energy transfer mechanism. Conversely, the matter exchange fraction grows monotonically during the early-to-intermediate epochs and approaches a quasi-saturated regime at late times. This behavior suggests that matter becomes the primary mediator of internal energy redistribution once radiation becomes dynamically subdominant. The dark energy exchange fraction remains negative throughout the entire cosmic evolution considered here, with only mild temporal variation. This persistent negative contribution indicates a net transfer of energy away from the dark energy sector, consistent with its effective role as an energy reservoir.

2.3. The Cosmic Temperature

The cosmic temperature T refers to the photon temperature, while the radiation energy density includes all relativistic species. It can be estimated from radiation density (

as follows, using Equation (36)

(e.g., [

10]

):

where

(T) is the effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom contributing to the

energy density [

20]

, and is the radiation constant [

19], i.e.,

. The parameter

(T) generally varies with the different cosmic epochs [

20].

In the present study for the time period up to t=100kyears we estimate the cosmic temperature from Equation (36). The radiation density

is estimated from

and the total density

derived in [

7].

Concerning later times (i.e., t > 100kyears) the selected approach is to use simple relationships such as

, starting from the temperature predicted by Equation (36) at 100kyears, to ensure continuation. The other end of the correlation is the contemporary temperature

The

fitting has led to following relationship:

In summary, Equations (36) and (37) are used to derive a first-order approximation for the cosmic temperature evolution, covering the whole time range up to the present time.

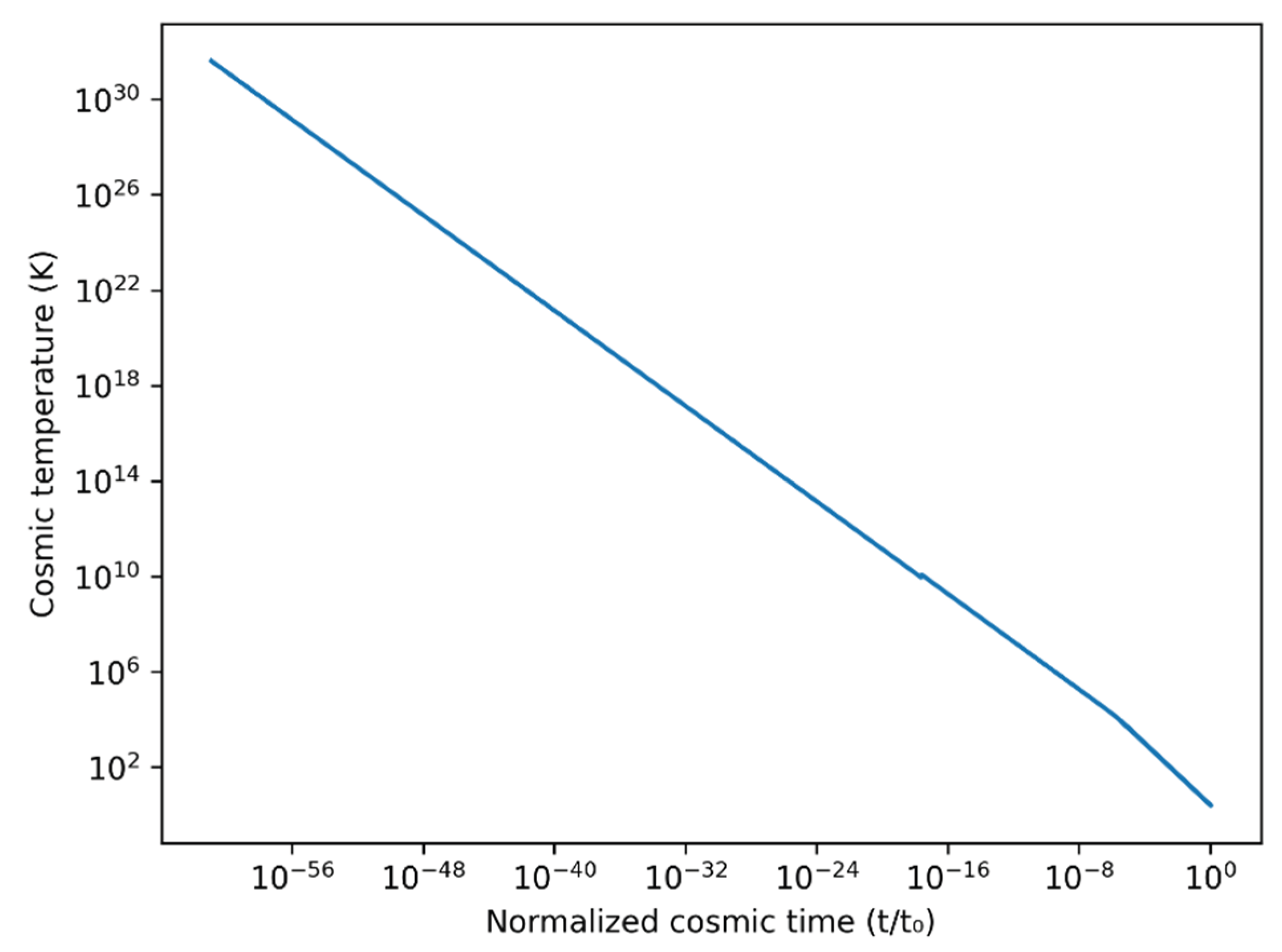

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the cosmic temperature as a function of the normalized time ratio (t/t₀) as given by Equations (36) and (37). The monotonic decline reflects the cooling of the Universe due to cosmic expansion, with early epochs characterized by extremely high temperatures and later times approaching present-day values.

It would be interesting at this stage to see how the present conceptual framework performs in predictions of key cosmic temperatures that characterize the Universe evolution. These estimations are as summarized in

Table 1 and compared with the data reflecting more or less the present state of the art.

Table 1 demonstrates a generally good level of agreement between the predictions of the present conceptual framework and representative state-of-the-art estimates. This agreement is particularly noteworthy given that (a) the present analysis is intentionally based on simplified, first-order approximations, and (b) the reference values reported in the literature themselves carry non-negligible uncertainties, both in the estimated temperatures and in the corresponding cosmic times associated with each epoch