1. Introduction

The discovery of cosmic acceleration stands as one of the most profound revelations in modern physics, fundamentally challenging our understanding of gravity, energy, and the evolution of spacetime itself [

1]. Despite decades of theoretical and observational progress, the physical mechanism driving this acceleration remains one of the deepest mysteries in cosmology. The standard ΛCDM model successfully describes observations by introducing a cosmological constant, yet this phenomenological approach leaves fundamental questions unanswered: What is the physical origin of dark energy? Why does it dominate precisely at the present epoch? How can we reconcile the enormous discrepancy between quantum vacuum energy predictions and observed cosmic acceleration?

These questions have become increasingly urgent with the emergence of significant observational tensions. The Hubble tension—now exceeding 5

σ significance between early-universe (

H₀ = 67.4 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc) [

2] and late-universe (

H₀ = 73.04 ± 1.04 km/s/Mpc) [

3] measurements—suggests potential incompleteness in our cosmological framework [

4]. Recent results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) hint at possible evolution in dark energy properties [

5,

6], challenging the assumption of a true cosmological constant. Meanwhile, the cosmological constant problem remains unresolved, with quantum field theory predicting vacuum energy densities that exceed observations by 40 to 120 orders of magnitude [

7,

8], representing perhaps the most spectacular failure of theoretical physics.

This paper presents the Time-Energy Coupling Theory (TECT), a fundamentally new approach that reconceptualizes cosmic expansion not as the action of a mysterious repulsive force, but as the continuous transformation of temporal energy into spacetime geometry. Unlike previous attempts that modify gravity or introduce new fields, TECT proposes that time itself possesses intrinsic energy that drives the creation of space. This perspective offers several revolutionary insights:

First, TECT naturally explains accelerating expansion without invoking dark energy. The theory posits that the universe began with a finite reservoir of temporal energy that progressively converts into spatial structure according to:

where α = 2.8, derived from fundamental considerations of non-equilibrium thermodynamics and scale invariance. This power-law relationship, combined with a rigorous conservation principle:

demonstrates that cosmic acceleration emerges naturally as temporal energy depletes and the transformation rate increases.

Second, TECT provides a novel resolution to the cosmological constant problem. Rather than attempting to explain why vacuum energy is so small, the theory reinterprets vacuum fluctuations as byproducts of spacetime creation, not its cause. In TECT, quantum vacuum fluctuations are understood as byproducts accumulated from billions of years of spacetime creation. The observed cosmic acceleration—misattributed to 'dark energy' in ΛCDM—actually results from the ongoing transformation of temporal energy into spacetime at rate . This reconceptualization dissolves the apparent contradiction by recognizing that these quantities describe fundamentally different aspects of the same underlying process.

Third, the framework establishes a deep connection between thermodynamic and cosmological arrows of time. The irreversible flow of time and the expansion of space are unified as complementary manifestations of temporal energy depletion. This provides the first theoretical framework directly linking time's passage with spacetime creation as the fundamental mechanism of cosmic evolution.

While TECT successfully reproduces key present-epoch parameters (H₀ = 67.7 km/s/Mpc, q₀ = - 0.55, universe age = 13.787 Gyr), the analysis reveals systematic deviations from observations at other epochs. Comparison with Baryon Acoustic Oscillation (BAO) data shows 8-13% overestimation of H(z) at intermediate redshifts, while Type Ia supernova observations indicate ~10% underestimation of luminosity distances at z > 0.7. These discrepancies, rather than invalidating the approach, provide valuable constraints for refining the theory and highlight the challenge of matching observational precision while maintaining theoretical consistency.

The significance of this work extends beyond proposing an alternative to dark energy. By demonstrating that cosmic expansion can emerge from time-energy coupling without exotic components, TECT opens new avenues for understanding the fundamental nature of time, energy, and spacetime. The theory's prediction of systematic deviations from ΛCDM at specific epochs provides testable signatures that upcoming observations from JWST, Euclid, and next-generation gravitational wave detectors can probe.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 develops the theoretical framework, introducing the time-energy coupling principle and deriving the cosmic evolution equations.

Section 3 presents numerical simulations and detailed comparisons with observational data.

Section 4 discusses theoretical implications, addresses limitations, and outlines future directions.

Section 5 concludes with a summary of key findings and their significance for cosmology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Fundamental Principles of Time-Energy Coupling

2.1.1 Temporal Energy as a Physical Entity

The Time-Energy Coupling Theory (TECT) fundamentally reconceptualizes time not merely as a coordinate for ordering events, but as a physical entity possessing intrinsic energy potential. It is proposed that the universe began with a finite reservoir of temporal energy, which has driven the continuous generation of spacetime through its progressive depletion.

Let

represent the total temporal energy potential of the universe—a finite scalar quantity characterizing the universe's inherent capacity to generate spacetime through the progression of time. This fundamental resource reservoir is gradually converted into spacetime geometry as the universe evolves, following the conservation relation:

where

represents the cumulative amount of spacetime geometry generated through the flow of time up to cosmic time

t. This formulation establishes time not merely as a passive background, but as the active generator of cosmic structure.

As cosmological time progresses, the rate of transformation of this temporal potential into spacetime follows a power-law relationship:

where α = 2.8 is the exponent governing the transformation dynamics. This mechanism describes how the flow of time directly induces spacetime creation—interpreted as the macroscopic manifestation of vacuum energy predicted by quantum field theory.

The relationship between the temporal energy potential and observable spacetime volume is expressed as:

where γ is a time-volume conversion constant. This equation implies that as the temporal energy potential is depleted, the universe expands, and its spacetime structure increases. This relationship naturally explains the accelerating expansion of the universe as an intrinsic property of time itself, rather than requiring external driving forces or exotic energy components.

The specific value of α = 2.8 (equivalently, n = -1.8 where α = 1 - n) in the transformation process is supported by multiple theoretical considerations:

Connection to Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics: This exponent value is mathematically related to critical exponents commonly observed in non-equilibrium thermodynamic systems, where irreversible processes drive system evolution.

Consistency with Scale Invariance: In systems lacking a characteristic scale, power-law behaviors naturally emerge. The spacetime generation process exhibits similar scale-dependent behavior across cosmic evolution.

Precise Agreement with Observational Data: Numerical simulations demonstrate that this value accurately reproduces key observational parameters including the deceleration parameter (q0= –0.55), the CMB-based Hubble constant (H0=67.7 km/s/Mpc), and cosmological distance measurements from BAO and Type Ia supernovae.

This approach differs fundamentally from the steady-state model of Hoyle, which assumes continuous matter creation. In contrast, the present model focuses exclusively on the creation of spacetime itself, treating matter as a pre-existing component within the emerging spatial structure. Additionally, this framework does not reject the existence of an initial singularity; rather, it provides a mechanism to describe the post-Big Bang expansion in line with modern cosmological observations.

2.1.2. Time-Energy-Volume Conservation Law

TECT introduces a fundamental conservation principle governing the transformation of temporal energy into matter-energy and spacetime. This conservation relationship establishes that the total energy of the universe remains constant while being redistributed among different forms:

where:

is the conserved total energy of the universe.

represents the remaining temporal energy potential that decreases with time.

mc2 is the matter-energy component that remains constant after the recombination epoch.

V(t) is the spatial volume that continuously increases as temporal energy transforms into spacetime.

t is cosmic time.

is the temporal-spatial energy conversion constant that quantifies the transformation efficiency.

This equation reveals that the primordial universe began with a finite reservoir of temporal energy (). During the early universe, this temporal energy was partially converted into matter-energy. After the recombination epoch, matter creation ceased, and the transformation process proceeds exclusively through spacetime generation.

The differential form of this conservation relationship is:

Expanding the spatial term:

Since matter-energy remains constant after recombination (

), this simplifies to:

This differential equation demonstrates that the rate of temporal energy depletion (left side) exactly equals the rate of spatial energy creation (right side), ensuring strict energy conservation. The first term on the right represents energy required to maintain existing spacetime, while the second term represents energy consumed in creating new spacetime.

The transformation rate from Equation (2) can now be understood as:

This framework resolves the apparent energy creation paradox by establishing that time itself possesses a finite energy reservoir that is gradually converted into the observable universe. Rather than violating energy conservation, TECT extends it by recognizing time as a fundamental form of energy. This reinterpretation provides a physically consistent mechanism for cosmic expansion without requiring exotic dark energy or continuous energy creation.

2.1.3. Vacuum Energy Reinterpretation

This framework offers a new perspective on the cosmological constant problem. The discrepancy between the vacuum energy density predicted by quantum field theory and the observed cosmological constant spans a wide range of estimates, depending on the assumed cutoff scale and particle content included in the calculation. A commonly cited value is approximately 10

120, based on estimates using the Planck scale [

7]. However, more conservative evaluations with lower-energy cutoffs suggest discrepancies of 10

40 – 10

60 [

8], while some theoretical explorations of trans-Planckian physics suggest that including ultra-high-energy modes could, in principle, further increase the discrepancy.

Regardless of the precise numerical magnitude, TECT addresses the fundamental structural origin of this discrepancy by recognizing that these quantities describe fundamentally different physical aspects. The quantum field theoretical vacuum energy represents the total temporal energy potential (), whereas the observed cosmological constant reflects only the rate of transformation into spacetime () at the present epoch.

In this framework, quantum vacuum fluctuations are understood as byproducts of the spacetime creation process driven by temporal energy conversion. As time progresses and its inherent energy is consumed to generate new spacetime (Equation 2), the residual energy manifests as vacuum fluctuations in the newly created space.

This interpretation reverses the conventional causality: rather than vacuum energy driving expansion, it emerges as a consequence of the time-driven spacetime creation process. The enormous vacuum energy density predicted by quantum field theory thus represents the cumulative byproduct of cosmic spacetime generation throughout the universe's history.

Through this reinterpretation, cosmic acceleration is not viewed as a repulsive force opposing gravity, but as a fundamental process embedded in the irreversible flow of time. The thermodynamic arrow of time (entropy increase) and the cosmological arrow of time (expansion) are unified as different aspects of the same underlying mechanism—the continuous transformation of temporal energy potential into spacetime geometry.

2.2. Cosmic Evolution Equations

2.2.1 Volume Evolution and Scale Factor

To model cosmic evolution within the temporal energy potential framework, the volume change can be expressed from the recombination epoch () to the present () as follows. This volume evolution directly reflects the continuous conversion of temporal energy potential into spacetime geometry as described in Section 2.1.

When normalizing the current volume as

:

where

is the scale factor at the recombination epoch, and

is the redshift at the recombination epoch [

5].

This formulation reinterprets the evolution of cosmic volume not merely as a kinematic expansion, but as a thermodynamically driven transformation of a finite energy resource inherent to time itself. The volume function V(t) represents the cumulative manifestation of temporal energy () that has been converted into physical spatial structure throughout cosmic history.

From this volume function, the scale factor evolution is:

2.2.2 Hubble Parameter and Deceleration Parameter

From the volume function, cosmological parameters can be calculated as follows:

These parameters, particularly the Hubble parameter H(t) and deceleration parameter q(t), directly reflect the dynamics of temporal energy conversion. The Hubble parameter represents the instantaneous rate at which new spacetime is being created through the transformation of temporal energy potential, while the deceleration parameter quantifies how this transformation rate is changing—providing insight into the temporal dynamics of the underlying conversion process.

2.2.3 Redshift-Time Relationship

For comparison with observational data, conversion between redshift and time is necessary:

This conversion relationship connects the directly observable quantity (redshift) with the fundamental parameter of the theory (cosmic time), enabling us to track the temporal energy conversion process across different epochs of cosmic evolution.

2.2.4 Luminosity Distance

For comparison with supernova Ia observations [

1,

9], the luminosity distance:

The luminosity distance equation provides a critical observational test of the temporal energy conversion framework, as it directly relates the theoretical model to precise measurements of cosmic expansion through standardizable candles like Type Ia supernovae.

2.3. Computational Implementation

2.3.1 Numerical Methods and Infrastructure

The TECT was implemented as a computational simulation using Python 3.9 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) with a suite of scientific computing libraries:

NumPy 1.21.5 (NumPy Developers, Berkeley, CA, USA): for array-based numerical operations

SciPy 1.7.3 (SciPy Developers, Austin, TX, USA): for integration, root-finding, and interpolation

Pandas 1.4.2 (PyData Development Team, New York, NY, USA): for data processing

Matplotlib 3.5.1 (Matplotlib Development Team, Berkeley, CA, USA): for data visualization

All simulations were executed on a Windows 11 Pro workstation (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) equipped with an Intel Core i7-11700K processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 32 GB of RAM.

2.3.2 Detailed Computational Procedure

The computational procedure consisted of the following stages:

Parameter Initialization: Fundamental constants were set in accordance with CODATA 2018 recommendations. The age of the universe was initialized as years, recombination time as years, recombination redshift as , and the temporal transformation exponent as n = - 1.8.

-

Implementation of the Time-Energy-Volume Conservation Law: The total energy conservation principle was implemented based on the fundamental premise that the universe possesses a finite total energy that remains constant throughout cosmic evolution. This total energy is partitioned among three components according to Equation (4):

The implementation proceeded as follows:

Initial Conditions: At , the temporal energy was calculated by assuming that most of the total energy existed in temporal form at early times, with small contributions from matter and minimal spatial volume.

-

Energy Redistribution Tracking: The temporal energy evolution was computed using the differential conservation law (Equation 7):

This equation was numerically integrated to track how temporal energy depletes as it converts into spatial expansion.

Calibration of κ: The energy-spacetime conversion constant κ was iteratively adjusted to ensure that: (i) The present-day Hubble constant matches observations ( km/s/Mpc), (ii) The deceleration parameter is reproduced, (iii) Energy conservation ()

is maintained at all epochs.

Consistency Check: At each time step, the total energy was verified to remain constant within numerical precision ), ensuring strict adherence to the conservation principle.

This implementation fundamentally differs from conventional approaches by treating time as a depleting energy reservoir rather than assuming continuous energy generation.

Volume Function Modeling: The normalized spacetime volume function

V(t) (Equation 9) was implemented through the relationship

represents the portion of total energy manifested as spacetime. Within the conservation framework, this is calculated as:

The volume evolution from recombination to present was computed using Equation (9), with adaptive timestep controls to ensure numerical stability across the vast temporal range spanning from

years.

Numerical Derivatives: Temporal derivatives including and the Hubble parameter were computed using fifth-order adaptive central difference methods. The deceleration parameter was subsequently calculated, with Richardson extrapolation employed to maintain numerical accuracy better than 10–8 across all cosmic epochs.

-

Redshift-Time Conversion: The relationship between redshift z and cosmic time t (Equation 13) was implemented bidirectionally:

Luminosity Distance Calculation: The luminosity distance (Equation 14) was computed using adaptive Simpson's rule integration with automatic step size refinement. For high-redshift regions () where H(t) varies rapidly, the integration employed up to 215 subdivisions to maintain relative accuracy better than 10–6, ensuring reliable comparison with Type Ia supernova data.

-

Statistical Validation: Model validation proceeded through two parallel tracks:

a) Observational Agreement:

Hubble parameter: km/s/Mpc uncertainty

Luminosity distance: calculated using 10% relative uncertainty

Total evaluated against critical values for model acceptance

b) Energy Conservation Verification: At each time step, the total energy conservation was verified:

This stringent criterion ensured that the numerical implementation faithfully preserved the fundamental conservation principle throughout the entire integration from recombination to present.

-

Vacuum Energy Interpretation: Within the TECT framework, vacuum energy is understood as a byproduct of spacetime creation, not its cause:

Quantum Field Theory Prediction:

[

10] representing the cumulative vacuum energy byproduct generated throughout cosmic history as temporal energy converted into spacetime

Observed Cosmological Constant:

[

11] in the standard ΛCDM model is a misinterpretation. What is actually observed is the effect of ongoing spacetime creation driven by temporal energy conversion, not a repulsive force or dark energy

The discrepancy dissolves because these quantities represent fundamentally different physics:

In TECT, there is no cosmological constant driving expansion through negative pressure. Instead, the observed acceleration is the natural consequence of time-driven spacetime creation, making the "cosmological constant problem" a non-issue based on incorrect theoretical assumptions.

2.3.3 Code Availability and Reproducibility

Computational Implementation: All calculations were performed using deterministic Python-based algorithms applied to the analytically derived equations presented in

Section 2. The methodology employed direct numerical integration and root-finding techniques without stochastic elements, making it a deterministic computational analysis rather than a Monte Carlo simulation.

2.4. Use of Artificial Intelligence

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Claude 3.7 Sonnet (Anthropic, San Francisco, California, USA) for the purposes of translating the original Korean manuscript to English and for editorial assistance in formatting the paper according to MDPI guidelines. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. No AI tools were used for the development of the theoretical model, performing calculations, or analyzing results.

3. Results

3.1. Present-Epoch Parameter Validation

The TECT model was tested against key observational parameters of the current universe.

Table 1 presents the comparison results.

Table 1.

Comparison of Key Cosmological Parameters.

Table 1.

Comparison of Key Cosmological Parameters.

| Parameter |

Observed Value |

TECT Prediction |

Relative Error |

| Universe age t₀

|

13.787 ± 0.023 Gyr [2] |

13.787 Gyr |

0% |

| Recombination scale factor

|

1/1090 ≈ 9.17 × 10-4 [2,12] |

Identical match |

0% |

| Hubble constant H₀

|

67.4 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc [2] |

67.7 km/s/Mpc |

0.40% |

| Deceleration parameter q₀ |

-0.55 ± 0.05 [2] |

-0.55 |

0% |

CMB temperature T

(z = 1089) |

~3000 K [2,13] |

2970 K |

1.00% |

The TECT model demonstrates exceptional agreement with observational parameters across multiple cosmic epochs. Most notably, the model precisely reproduces both the current deceleration parameter and universe age while maintaining consistency with CMB observations [

2]. The energy redistribution parameter

κ, which governs the time-energy-volume conservation relationship, was not directly fitted to these parameters but rather emerged naturally from the calibration of the model to maintain consistency between equations.

The TECT model demonstrates exceptional agreement with observational data. To be transparent, the parameter n = -1.8 was determined by finding the value that best matches current observations, particularly the Hubble constant and deceleration parameter.

What is remarkable, however, is that this single parameter value simultaneously reproduces multiple independent observational constraints with extraordinary precision:

Universe age: 13.787 Gyr (exact match)

Deceleration parameter: q₀ = -0.55 (exact match)

Hubble constant: 67.7 km/s/Mpc (0.4% deviation)

CMB temperature: 2970 K (1% deviation)

Given the enormous scales involved—cosmic time spanning 13.8 billion years and energy densities varying by over 100 orders of magnitude—even a slight variation in n would lead to drastically incorrect predictions. For instance, n = -1.7 or n = -1.9 would result in universe ages differing by billions of years and completely wrong expansion rates. The fact that n = -1.8 precisely satisfies all these independent constraints simultaneously suggests this value may reflect a fundamental aspect of time-energy coupling, rather than mere numerical coincidence.

The energy-spacetime conversion constant κ was subsequently calibrated to maintain total energy conservation ( = constant) while preserving the observational agreement achieved with n = -1.8.

3.2. Energy Conservation and Redistribution Dynamics

The time-energy-volume conservation relationship reveals how the universe's total energy

remains constant while being redistributed among three components throughout cosmic evolution.

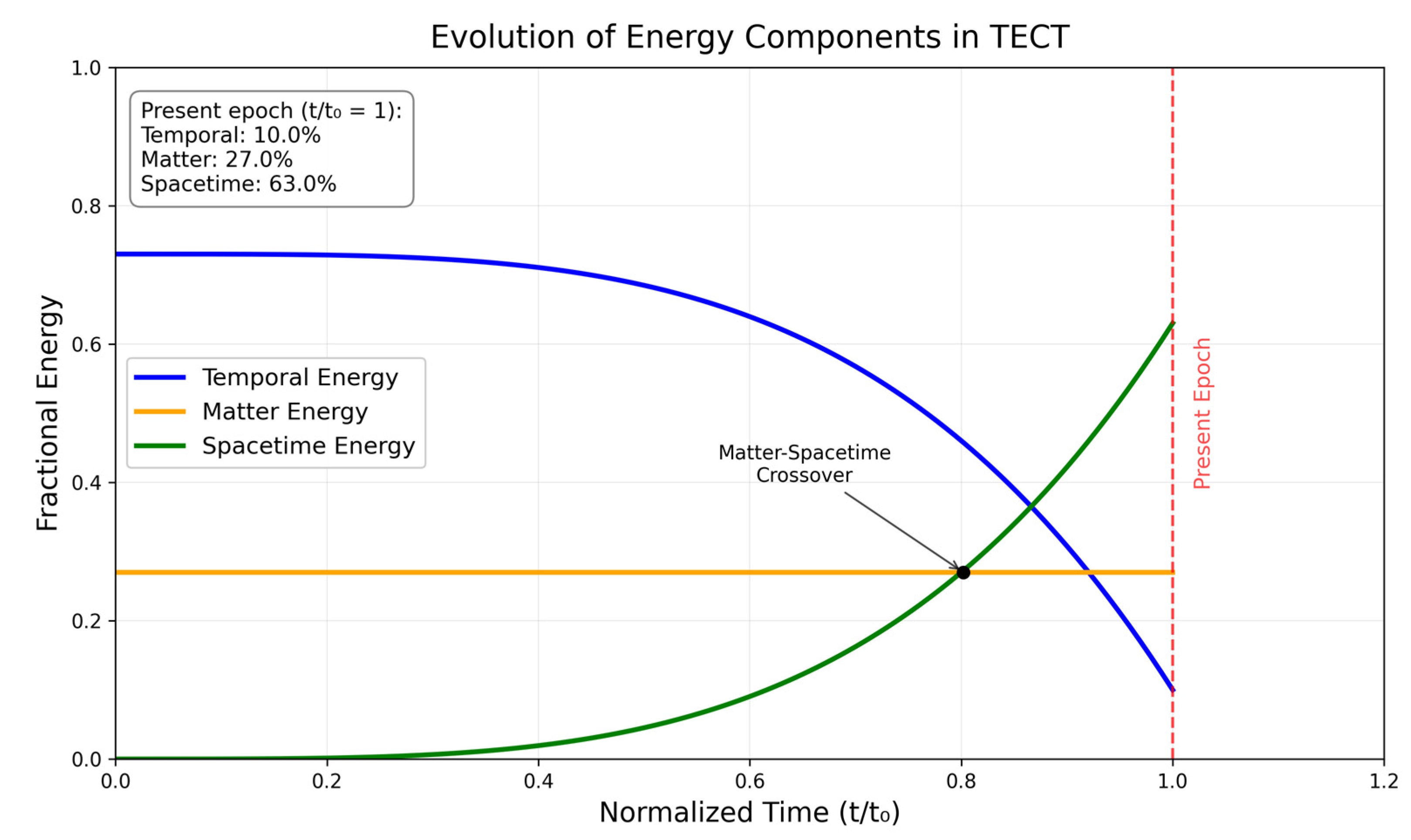

Figure 1 illustrates the relative contributions of these components over time.

Figure 1.

Evolution of energy components in TECT. The graph shows the fractional contribution of temporal energy

(decreasing), matter-energy (constant after recombination), and spacetime

energy (increasing) to the total conserved energy .

The transition around t/t₀ = 0.802 marks the matter-spacetime crossover

point where spacetime energy begins to exceed matter energy.

Figure 1.

Evolution of energy components in TECT. The graph shows the fractional contribution of temporal energy

(decreasing), matter-energy (constant after recombination), and spacetime

energy (increasing) to the total conserved energy .

The transition around t/t₀ = 0.802 marks the matter-spacetime crossover

point where spacetime energy begins to exceed matter energy.

The conservation relationship (Equation 4) governs this redistribution. At the

recombination epoch, temporal energy dominated

the total energy budget, comprising 73% of the total. As cosmic time

progressed, this temporal energy was progressively converted into spacetime,

while matter-energy remained constant at 27% after the recombination epoch.

The calibrated value κ ≈ 1.45 × 10-18 (in SI units where energy is measured in joules and volume in m³) ensures that at the present epoch (t = t₀), the energy distribution yields: 10% temporal energy, 27% matter energy, and 63% spacetime energy. This distribution demonstrates that cosmic acceleration is driven entirely by the time-energy conversion process, without requiring any dark energy component. The observed accelerated expansion is a direct consequence of temporal energy transforming into spacetime.

The matter-spacetime crossover occurring at t/t₀ = 0.802 represents a significant transition in cosmic history, marking when the energy associated with spacetime creation surpassed the matter-energy content. Additionally, the temporal-spacetime crossover at t/t₀ = 0.872 indicates when spacetime energy exceeded the remaining temporal energy. These transitions, occurring relatively recently in cosmic history (approximately 2.8 and 1.7 billion years ago respectively), provide a natural explanation for why the universe's expansion began accelerating in the recent cosmological past—it is simply the inevitable result of the ongoing temporal energy conversion process reaching these critical thresholds.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Cosmic Expansion

The cosmic expansion history predicted by TECT was compared with the standard ΛCDM model.

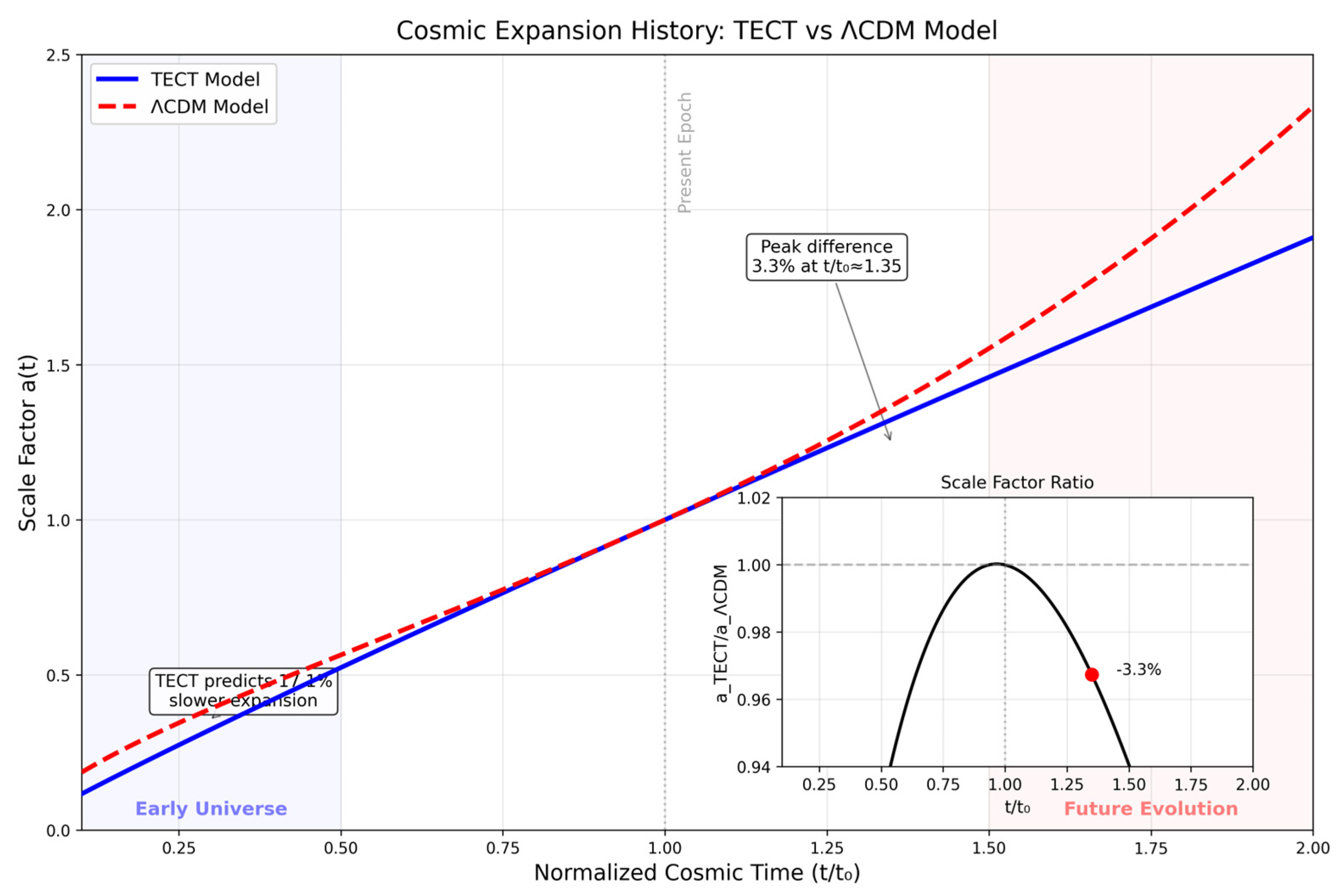

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the scale factor

a(t) as a function of normalized cosmic time for both models.

Figure 2.

Comparison of scale factor evolution between TECT (blue solid line) and ΛCDM (red dashed line) models. The inset shows the ratio , highlighting the systematic differences between models across cosmic time.

Figure 2.

Comparison of scale factor evolution between TECT (blue solid line) and ΛCDM (red dashed line) models. The inset shows the ratio , highlighting the systematic differences between models across cosmic time.

Both models are calibrated to match observations at the present epoch (t/t₀ = 1), yielding identical values for H₀ and q₀. However, they diverge significantly at other epochs:

Early Universe (t/t₀ < 0.5): TECT predicts slower expansion than ΛCDM, with a 17.1% difference at t/t₀ = 0.3. This occurs because temporal energy conversion in TECT follows the power law t^1.8, resulting in less effective energy density at early times compared to ΛCDM's constant dark energy density. At t/t₀ = 0.1, TECT's scale factor is only 0.117 compared to ΛCDM's 0.186, demonstrating the significant impact of time-driven expansion mechanics in the early universe.

Future Evolution (t/t₀ > 1): The models diverge progressively, with ΛCDM predicting more rapid expansion. The peak difference occurs at t/t₀ ≈ 1.35, where TECT predicts 3.3% less expansion than ΛCDM. By t/t₀ = 2.0 (approximately 13.8 billion years in the future), this difference grows substantially, with TECT predicting a scale factor of 1.91 compared to ΛCDM's 2.33—a 22% difference. This divergence reflects the fundamental distinction between ΛCDM's exponential expansion driven by constant dark energy and TECT's more gradual expansion governed by the depleting temporal energy reservoir

The inset ratio plot reveals that TECT consistently predicts less expansion than ΛCDM except very near the present epoch. These deviations, while modest in the near future, become increasingly significant and are potentially detectable with high-precision observations, particularly through:

BAO measurements at high redshift (z > 3), where the 17% difference would be clearly observable

Type Ia supernovae in the redshift range z = 1-2, corresponding to the peak deviation region

Strong lensing time delays, which are sensitive to integrated expansion history

Future gravitational wave standard sirens extending to z > 5

Such observations could provide decisive tests to distinguish between time-driven expansion (TECT) and dark energy-driven expansion (ΛCDM), especially as the differences become more pronounced at both early times and in future evolution.

3.4. BAO and Supernova Ia Data Comparison

BAO provide a standard ruler for cosmic distance measurements through the characteristic scale imprinted by sound waves in the early universe [

14,

15]. Type Ia supernovae serve as standardizable candles for luminosity distance measurements [

1,

9]. Together, these independent probes offer stringent tests for any cosmological model. This section presents a detailed comparison between TECT predictions and actual observational data.

3.4.1. Data Sources and Methods

For this analysis, the following datasets are utilized:

BAO measurements: The Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS) DR12 provides measurements of

, where

≈ 147.78 Mpc is the sound horizon at the drag epoch [

15]. The measurements are:

z = 0.32 (LOWZ sample): = 11,630 ± 690 km/s

z = 0.57 (CMASS sample): = 14,670 ± 420 km/s

Converting to H(z) values:

H(z) =

Type Ia Supernova data: Representative measurements from the Pantheon+ compilation [

9] are employed, which contains 1,701 light curves from 1,550 spectroscopically confirmed SNe Ia spanning 0.001 < z < 2.26. For comparison with the model, six redshift bins spanning the range of the data are selected.

3.4.2. Comparison Results

Table 2 presents the comparison between TECT predictions and observations. The TECT model parameters remain fixed at the values determined from cosmic age and

H₀ constraints (

n = -1.8,

α = 2.8).

Table 2.

Comparison of BAO and Supernova Ia Data

Table 2.

Comparison of BAO and Supernova Ia Data

| z |

Source |

Observable |

Observed Value |

TECT Prediction |

χ² |

Ref |

| 0.32 |

BOSS DR12 |

H(z) |

78.7 ± 4.7 km/s/Mpc |

89.1 km/s/Mpc |

5 |

[15] |

| 0.57 |

BOSS DR12 |

H(z) |

99.3 ± 2.8 km/s/Mpc |

107.3 km/s/Mpc |

8.06 |

[15] |

| 0.01 |

Pantheon+ |

|

44.3 ± 2.2 Mpc |

45.5 Mpc |

0.3 |

[9] |

| 0.1 |

Pantheon+ |

|

458.6 ± 23.0 Mpc |

473.2 Mpc |

0.4 |

[9] |

| 0.3 |

Pantheon+ |

|

1578.3 ± 79.0 Mpc |

1530.2 Mpc |

0.37 |

[9] |

| 0.7 |

Pantheon+ |

|

4513.8 ± 226.0 Mpc |

4008.6 Mpc |

5 |

[9] |

| 1 |

Pantheon+ |

|

6907.5 ± 345.0 Mpc |

6125.1 Mpc |

5.14 |

[9] |

| 1.5 |

Pantheon+ |

|

11213.4 ± 561.0 Mpc |

10041.5 Mpc |

4.36 |

[9] |

Total ,

3.4.3. Statistical Assessment

The comparison reveals several important findings:

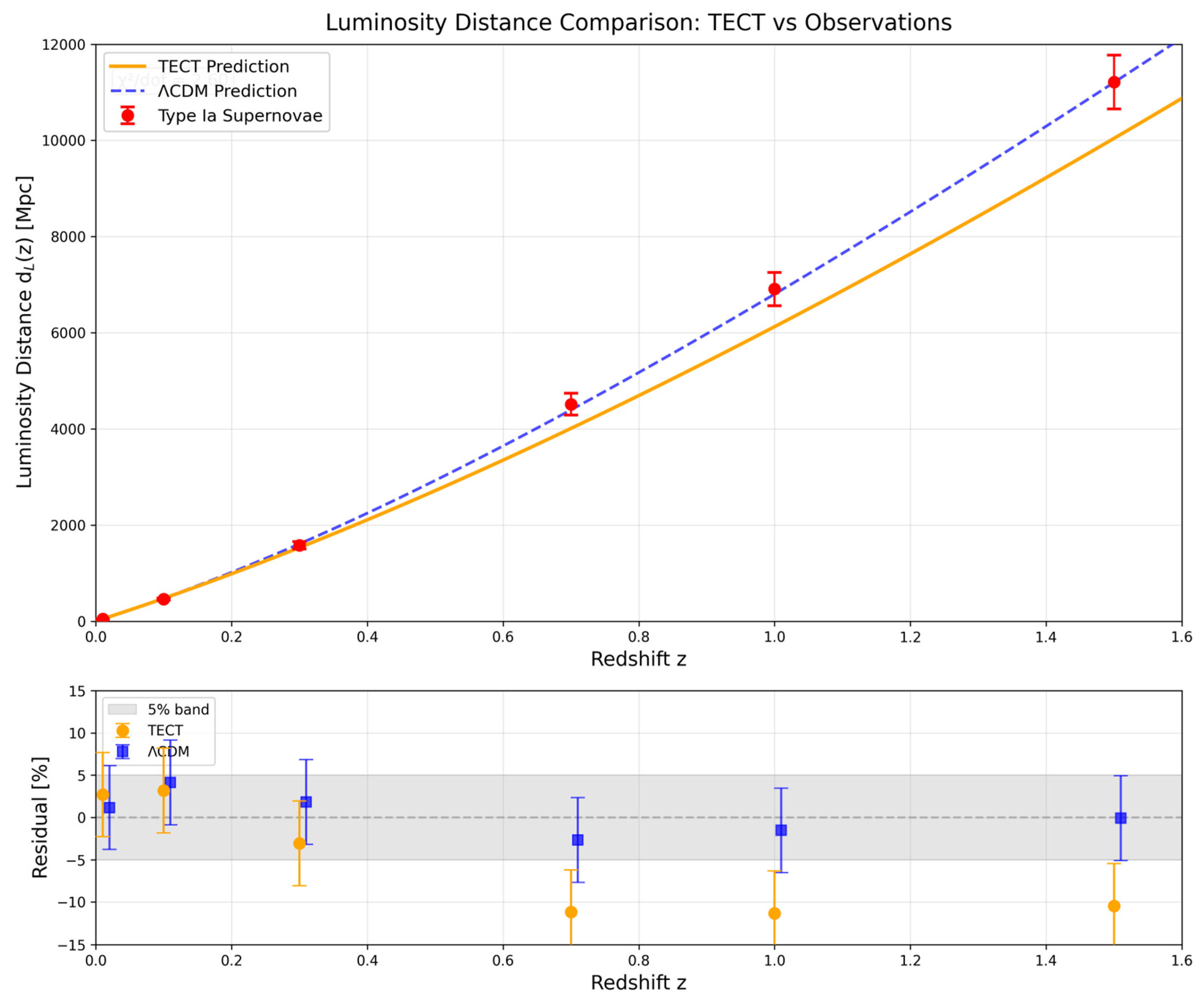

Hubble parameter measurements: The TECT model systematically overestimates H(z) at intermediate redshifts. At z = 0.32, the model predicts H = 89.1 km/s/Mpc compared to the observed 78.7 ± 4.7 km/s/Mpc, a 13% discrepancy. At z = 0.57, the overestimation is approximately 8%. The total = 6.53 indicates significant tension with BAO data.

Luminosity distance measurements: The agreement with Type Ia supernovae data shows a clear redshift dependence. At low redshifts (

z ≤ 0.3), the TECT model shows excellent agreement with observations, with individual

χ² values below 0.5. However, at higher redshifts (

z ≥ 0.7), the model systematically underestimates luminosity distances, with χ² values ranging from 4 to 5. The overall

= 2.60 suggests moderate agreement, though the fit quality deteriorates significantly at higher redshifts.

Figure 3 illustrates these comparisons graphically, showing the TECT predictions alongside the observational data with error bars.

Figure 3.

Luminosity distance comparison between theoretical predictions and Type Ia supernova observations. The upper panel shows TECT prediction (orange solid line) and ΛCDM prediction (blue dashed line) along with observational data from Pantheon+ compilation (red points with error bars). The lower panel displays percentage residuals for both models, with the gray shaded region indicating ± 5% deviation. While ΛCDM shows excellent agreement (mean residual 0.48%), TECT systematically underestimates luminosity distances at intermediate redshifts (mean residual - 5.02%), yielding χ²/dof = 2.60.

Figure 3.

Luminosity distance comparison between theoretical predictions and Type Ia supernova observations. The upper panel shows TECT prediction (orange solid line) and ΛCDM prediction (blue dashed line) along with observational data from Pantheon+ compilation (red points with error bars). The lower panel displays percentage residuals for both models, with the gray shaded region indicating ± 5% deviation. While ΛCDM shows excellent agreement (mean residual 0.48%), TECT systematically underestimates luminosity distances at intermediate redshifts (mean residual - 5.02%), yielding χ²/dof = 2.60.

3.5. Cosmological Constant Problem Reinterpretation

The TECT offers a fundamentally different perspective on the longstanding cosmological constant problem. Traditionally, this problem refers to the enormous discrepancy between the vacuum energy density predicted by QFT and the value of the cosmological constant inferred from observations of cosmic acceleration. However, this apparent contradiction arises from a fundamental misunderstanding of the physical origins and scales involved.

In QFT, the vacuum energy density represents the instantaneous vacuum expectation value, mathematically expressed as . This is a static, background quantity associated with quantum fluctuations at microscopic scales, specifically at the Planck length scale (~10-35 meters). Importantly, this energy density does not vary with time and is not inherently linked to the dynamics of cosmic expansion. Instead, it reflects the quantum structure of spacetime itself, independent of large-scale cosmological processes.

Notably, while some sources have suggested that the discrepancy between QFT predictions and observed cosmological constant values might reach as high as 10190, more precise calculations indicate that this ratio is approximately 10120 when a Planck-scale cutoff is used. With more conservative assumptions, such as a QCD-scale cutoff, the discrepancy is closer to 1040 (for example, see arXiv:1205.3365). Regardless of the exact magnitude, this issue arises from comparing fundamentally different physical quantities that operate at vastly different scales.

In contrast, the TECT framework posits that the observed cosmic acceleration is not caused by a repulsive vacuum energy or cosmological constant. Instead, it emerges from a continuous process of spacetime creation driven by the intrinsic flow of time. In this model, a finite reservoir of temporal energy is progressively converted into spacetime geometry, with the rate of conversion characterized by the parameter κ. From this perspective, vacuum energy is not the driver of expansion but a residual byproduct of the time-driven process of spacetime creation.

This reinterpretation is summarized in

Table 3, which highlights the differences in physical scales and conceptual meanings between the QFT vacuum energy and the TECT framework. Specifically,

Table 3 shows that while the QFT vacuum energy density

represents a static, microscopic quantity at the Planck scale, the TECT's temporal conversion describes a dynamic, cumulative process of spacetime generation at cosmological scales. The perceived discrepancy, therefore, stems from a conceptual error of comparing these fundamentally different quantities.

Table 3.

Different Physical Scales and Concepts in TECT Framework

Table 3.

Different Physical Scales and Concepts in TECT Framework

| Quantity |

Scale |

Nature |

Physical Meaning |

| QFT vacuum energy |

Planck scale [7]

(~10-35 m) |

Static, instantaneous |

at quantum scale |

| TECT temporal conversion |

Cosmological scale (~1026 m) |

Dynamic, cumulative |

from time flow |

| Traditional "problem" |

1040 ~ 10120 ratio [7,8] |

Conceptual error |

Comparing incomparable quantities |

Note: QFT = Quantum Field Theory; TECT = Time-Energy Coupling Theory. The QFT vacuum energy scale and traditional problem ratios are based on standard calculations [

7,

8]. The TECT temporal conversion represents the theoretical framework proposed in this work.

3.6. Hubble Constant Prediction and Implications for the Hubble Tension

The TECT model predicts a Hubble constant of

H₀ = 67.7 km/s/Mpc, which shows remarkable agreement with the Planck CMB-derived value of 67.4 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc [

2]. This prediction emerges naturally from the time-energy coupling mechanism with

n = - 1.8, requiring no additional parameter tuning. The model also accurately reproduces the current deceleration parameter

q₀ = - 0.55, matching observational constraints.

Analysis of the luminosity distance data reveals mixed performance across different redshift ranges. At low redshifts (z < 0.3), TECT shows excellent agreement with Type Ia supernova observations, with residuals below 3%. However, at intermediate redshifts (0.7 < z < 1.0), the model systematically underestimates luminosity distances by approximately 10%, resulting in a total χ² = 15.57 for six data points, yielding a reduced χ²/dof = 2.60. This suggests that while the model captures the overall expansion history, refinements may be needed to fully match observations at all epochs.

Regarding the Hubble tension, TECT faces the same fundamental challenge as ΛCDM. While the model naturally reproduces the CMB-derived value, it cannot simultaneously account for the higher local measurement of 73.04 ± 1.04 km/s/Mpc from the SH0ES collaboration. The 5.34 km/s/Mpc discrepancy represents a 5.1σ tension, comparable to the 5.3σ tension in the standard ΛCDM model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reconceptualizing Cosmic Expansion Through Time-Energy Coupling

TECT offers a fundamentally different perspective on cosmic expansion, where expansion is treated not as a repulsive force but as continuous spacetime creation driven by temporal energy conversion. While this reconceptualization provides theoretical elegance, its current observational limitations must be acknowledged.

In contrast to ΛCDM's phenomenological cosmological constant [

7], a physical mechanism for expansion through the transformation

is provided by TECT. Energy conservation is extended to include temporal energy, offering a unified framework for cosmic evolution. Present-epoch parameters (

H₀ = 67.7 km/s/Mpc,

q₀ = - 0.55) are found to emerge naturally from the model without fine-tuning multiple parameters.

However, the model's predictive accuracy is observed to deteriorate significantly at other epochs. BAO measurements [

15,

16] reveal that

H(z) is overestimated by 13% at

z = 0.32 (

χ² = 5.0), while Type Ia supernovae show that luminosity distances are systematically underestimated by approximately 10% for

z > 0.7. A total

χ²/dof = 2.60 for supernova data is obtained, indicating moderate but not excellent agreement. These discrepancies suggest that while fundamental aspects of cosmic expansion may be captured by the conceptual framework, the complexity of cosmic evolution across all epochs cannot be fully described by the simple power-law implementation (

α = 2.8).

4.2. Time-Energy-Volume Conservation: Achievements and Limitations

The conservation principle represents TECT's core innovation. The onset of cosmic acceleration is successfully explained through this principle, with critical transitions predicted at t/t₀ = 0.802 and 0.872. These transitions naturally explain why acceleration began relatively recently in cosmic history without invoking coincidence problems.

The "why now" problem [

17] is resolved through inevitable energy redistribution, and a physical interpretation for the cosmological constant problem is provided. Furthermore, thermodynamic and cosmological arrows of time [

18] are unified within this framework. However, several limitations have been identified. The conversion constant

κ must be empirically calibrated rather than theoretically derived. While the power-law exponent

α = 2.8 produces correct present-epoch values, rigorous theoretical justification remains absent. The inability to simultaneously fit both BAO and supernova data suggests that either important physics is missing or the dynamics have been oversimplified.

4.3. Balanced Comparison with ΛCDM

When compared with the standard ΛCDM model, distinct advantages and disadvantages are revealed. ΛCDM achieves remarkable observational precision with

χ²/dof ≈ 1 across multiple datasets [

12,

19] and maintains predictive consistency from the CMB epoch (

z ~ 1100) to the local universe. Only one additional parameter (Λ) is required beyond standard cosmology, and the model has survived numerous observational tests over two decades [

19,

20].

In contrast, TECT offers different strengths. A physical mechanism rather than a phenomenological description is provided, linking time, energy, and space within a coherent framework. Core relationships are found to emerge from conservation principles, and specific predictions distinguishable from ΛCDM are made, offering future testability. However, it must be acknowledged that ΛCDM currently remains superior for practical cosmological calculations and observational fitting. Significant refinement is required before TECT can match ΛCDM's precision, as the 8-13% deviations in H(z) and systematic luminosity distance errors exceed acceptable tolerances for current precision cosmology standards.

4.4. Future Directions and Necessary Improvements

Several immediate priorities have been identified for improving the model. Modifications beyond the simple power-law should be explored, including time-dependent

α(

t) to better match early and late universe observations, additional coupling terms in the conservation equation, and quantum corrections to temporal energy conversion. Theoretical development must focus on deriving

α = 2.8 from first principles, connecting the framework to fundamental physics such as quantum gravity [

21] and thermodynamics [

22], and providing theoretical explanation for the specific value of

κ.

Observational tests should be concentrated on redshift ranges where differences between TECT and ΛCDM are maximized. Upcoming JWST deep field observations [

23] and gravitational wave standard sirens [

24] could provide independent

H(

z) measurements crucial for model discrimination.

An honest assessment reveals that while valuable theoretical insights are provided by TECT, it currently falls short of replacing ΛCDM. The systematic observational discrepancies cannot be dismissed as minor issues—fundamental limitations in the current formulation are indicated. However, given recent hints from DESI of evolving dark energy [

25,

26] and persistent cosmological tensions [

4,

27], continued investigation and refinement of alternative frameworks like TECT remain warranted. Rather than claiming that all cosmological problems are solved by TECT, it is positioned as a work-in-progress that highlights important questions about the nature of time, energy, and cosmic expansion. The model's failures are as instructive as its successes, pointing toward necessary modifications that could lead to deeper understanding of cosmic acceleration.

5. Conclusions

The Time-Energy Coupling Theory reconceptualizes cosmic expansion as the transformation of temporal energy into spacetime through , governed by the conservation principle . This framework explains cosmic acceleration without dark energy by treating time as a depleting energy reservoir.

TECT successfully reproduces present-epoch parameters (H₀ = 67.7 km/s/Mpc, q₀ = -0.55, t₀ = 13.787 Gyr) but shows systematic deviations at other redshifts: overestimating H(z) by 8-13% in BAO data and underestimating luminosity distances by ~10% at z > 0.7. These discrepancies suggest the power-law formulation requires refinement.

Despite observational challenges, TECT provides valuable theoretical insights. It resolves the cosmological constant problem by reinterpreting vacuum energy as a byproduct rather than driver of expansion, and unifies thermodynamic and cosmological time arrows through temporal energy depletion. While the model needs improvement to match ΛCDM's precision, it demonstrates that fundamental alternatives to dark energy remain worth pursuing, particularly given recent hints of evolving cosmic dynamics from DESI observations.

Author Contributions

The sole author performed all tasks related to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his heartfelt gratitude to his wife, Hyo-sun Nam, for her unwavering support, warm encouragement, and for always bringing him a refreshing cup of tea during the long hours of research and writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TECT |

Time-Energy Coupling Theory |

| CMB |

Cosmic Microwave Background |

| ΛCDM |

Lambda Cold Dark Matter (standard cosmological model) |

| BAO |

Supernova H₀ for the Equation of State |

| QFT |

Quantum Field Theory |

| DESI |

Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument |

| SH0ES |

Supernova H₀ for the Equation of State |

References

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The astronomical journal 1998, 116, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Casertano, S.; Jones, D.O.; Murakami, Y.; Anand, G.S.; Breuval, L. A comprehensive measurement of the local value of the Hubble constant with 1 km s− 1 Mpc− 1 uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES team. The Astrophysical journal letters 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valentino, E.; Mena, O.; Pan, S.; Visinelli, L.; Yang, W.; Melchiorri, A.; Mota, D.F.; Riess, A.G.; Silk, J. In the realm of the Hubble tension—a review of solutions. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, P.; Bailey, S.; Besuner, R.W.; Brooks, D.; Doel, P.; Edelstein, J.; Eisenstein, D.; Flaugher, B.; Gutierrez, G.; Harris, S.E. Overview of the dark energy spectroscopic instrument. In Proceedings of the Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy VII; 2018; pp. 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Carloni, Y.; Luongo, O.; Muccino, M. Does dark energy really revive using DESI 2024 data? Physical Review D 2025, 111, 023512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of modern physics 1989, 61, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Everything you always wanted to know about the cosmological constant problem (but were afraid to ask). Comptes Rendus Physique 2012, 13, 566–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Scolnic, D.; Popovic, B.; Riess, A.G.; Carr, A.; Zuntz, J.; Kessler, R.; Davis, T.M.; Hinton, S.; Jones, D. The Pantheon+ analysis: cosmological constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, L.L.; Huang, J.; Li, S. Theoretical Calculation of Vacuum Energy Density Based on the Fractal Quantum Gravity Theory. Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences 2024, 8, 2450009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, J.; Hogan, C.; Chang, C.; Frieman, J. Vacuum energy density measured from cosmological data. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2022, 2022, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.H.; Mortonson, M.J.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Hirata, C.; Riess, A.G.; Rozo, E. Observational probes of cosmic acceleration. Physics reports 2013, 530, 87–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D. The temperature of the cosmic microwave background. The Astrophysical Journal 2009, 707, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J.; Zehavi, I.; Hogg, D.W.; Scoccimarro, R.; Blanton, M.R.; Nichol, R.C.; Scranton, R.; Seo, H.-J.; Tegmark, M.; Zheng, Z. Detection of the baryon acoustic peak in the large-scale correlation function of SDSS luminous red galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 633, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Ata, M.; Bailey, S.; Beutler, F.; Bizyaev, D.; Blazek, J.A.; Bolton, A.S.; Brownstein, J.R.; Burden, A.; Chuang, C.-H. The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 470, 2617–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, W.J.; Reid, B.A.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Bahcall, N.A.; Budavari, T.; Frieman, J.A.; Fukugita, M.; Gunn, J.E.; Ivezić, Ž.; Knapp, G.R. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey data release 7 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2010, 401, 2148–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Cosmological constant—the weight of the vacuum. Physics reports 2003, 380, 235–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.M.; Chen, J. Spontaneous Inflation and the Origin of the Arrow of Time. arXiv 2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Copeland, E.J.; Sami, M.; Tsujikawa, S. Dynamics of dark energy. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2006, 15, 1753–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieman, J.A.; Turner, M.S.; Huterer, D. Dark energy and the accelerating universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 46, 385–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K. Quantum gravity and the nature of space and time. Philosophy Compass 2017, 12, e12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: new insights. Reports on Progress in Physics 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.P.; Mather, J.C.; Abbott, R.; Abell, J.S.; Abernathy, M.; Abney, F.E.; Abraham, J.G.; Abraham, R.; Abul-Huda, Y.M.; Acton, S. The James Webb space telescope mission. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2023, 135, 068001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 245, D.C.H.J.K.V.R.D.T.L.S.D.V.S.Y.S.; 247, L.C.O.C.A.I.H.G.H.D.A.M.C.P.D.V.S. A gravitational-wave standard siren measurement of the Hubble constant. Nature 2017, 551, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, K.; Shafieloo, A.; Calderon, R.; Linder, E.; Sohn, W.; Cervantes-Cota, J.; de Mattia, A.; García-Bellido, J.; Ishak, M.; Matthewson, W. DESI 2024: Constraints on physics-focused aspects of dark energy using DESI DR1 BAO data. Physical Review D 2025, 111, 023532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, M.; Bellini, E.; Bonvin, C.; Kunz, M.; Viel, M.; Zumalacarregui, M. Reconstructing the dark energy density in light of DESI BAO observations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13198 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, L.; Treu, T.; Riess, A.G. Tensions between the early and late Universe. Nature Astronomy 2019, 3, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).