Introduction

Rosen re-stated Curie’s symmetry principle [

1], (p. 308):

“If an ensemble of causes is invariant with respect to any transformation, the ensemble of their effects is invariant with respect to the same transformation”. Symmetry has become a critically important principle in science. Gross observed [

2], (p. 14256):

“In the latter half of the 20th century symmetry has been the most dominant concept in the exploration and formulation of the fundamental laws of physics. Today it serves as a guiding principle in the search for further unification and progress” Kotoky notes symmetry principles are now applied not only in physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, engineering, and computer science, but also in architecture, art and design, crystallography, nature, and even cognitive sciences such as psychology and linguistics [

3]. In applied measurement theory this principle can be expressed as follows: the symmetries in a transformation group acting on a frequency distribution of scores must be preserved in the transformed distribution, which may also exhibit additional invariances. This formulation parallels Rosen’s statement [

4], (p. 104):

“The symmetry group of the cause is a subgroup of the symmetry group of the effect”.

Nugent recently developed a matrix Lie group measurement model and demonstrated that several measurement symmetries are implied by this Lie-theoretic framework [

5]. Lie group theory is the mathematics of continuous symmetries. Lie algebras—examples of which are derived below—serve as the infinitesimal generators of the symmetries expressed by Lie groups. This article expands on Nugent’s model by identifying additional symmetries not included in his 2024 work. Practical examples are provided, including symmetries relevant for meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is widely regarded as one of the highest levels of evidence for identifying evidence-based outcomes. Foundational to meta-analysis is the assumption that scores from different measures can be placed onto a common metric using effect sizes, such as the standardized mean difference (SMD). The author will show that the population standardized mean difference (SMD), a commonly used effect size in meta-analysis, remains invariant across different measures if and only if specific measurement conditions—contained within Nugent’s matrix Lie group model—are satisfied [

5].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section develops the Lie group measurement framework, derivations, and symmetries not identified in Nugent’s model [

5]. The following section presents a simulation study, followed by implications for meta-analysis, and longitudinal and cross-cultural research. The paper concludes with broader reflections on the role of symmetry in applied measurement theory in the social and behavioral sciences.

Materials and Methods

Review and Further Development of Nugent’s (2024) Model

Following Nugent [

5], assume a set of

measures of a construct of interest. Let the relationship between true scores on any measure

, denoted

, and true scores on any measure

, denoted

, from the k measures be defined as,

with

and

a real number. Similarly, assume the relationship between the standard deviation of errors of measurement is,

This transformation consists of two components:

Rosen notes both are symmetry transformations, and the combination of (1) and (2) is also a symmetry transformation [

4]. Both transformations involve a uniform rescaling by the same parameter, γ. Another symmetry is that ratios such as,

where

and

are population mean true scores, are invariant, which accounts for many of the symmetries identified by Nugent [

5].

Now define the measurement vector:

where

represents the true scores on measure

, and

represents the standard deviation of errors of measurement on measure

. The homogeneous coordinate, the 1 in the third row of the vector, anchors the vector in a two-dimensional affine space. A transformation group acts on this vector to model relationships between scores on any two measures

and

from the

measures. The transformation matrix

is:

This matrix transforms the measurement vector as follows:

The transformation matrix

is a member of a matrix Lie group [

6].

Rosen introduced the notion of “approximate symmetry”, its potential use in science, and recommended the development indices of approximate symmetry [

4]. Nugent suggested an index of approximate symmetry (IAS) [

5],

where

is the reliability coefficient for observed scores Y

A. It will now be shown that this IAS index is proportional to the standardized Euclidean distance between two distributions of observed scores

and

. From above, the relationship between true scores on two measures

and

is given by eqn. (1),

with

and

a real number, and the relationship between the standard deviation of errors of measurement is given by eqn. (2),

Following [

7], the observed scores are:

where

and

are error scores. It follows the reliability of scores on measure A,

, is,

The z-scores for a person

on measures

and

are:

The standardized Euclidean distance (SED) between the distributions of z-scores is:

Let

Then,

For observed scores

,

Therefore, it follows that,

This is another symmetry associated with the conjunction (1) and (2).

The covariance between scores is,

Thus, the correlation between observed scores Y

A and Y

B is,

another symmetry. Since z-scores are linear transformations of observed scores, this correlation is preserved,

Now, the variance of the difference between z-scores is,

Since both z-score distributions are standardized,

Therefore, the standardized Euclidean distance between z-score distributions is proportional to Nugent’s suggested IAS [

5], with proportionality constant

. This result provides evidence for the validity of Nugent’s suggested measure of approximate symmetry by linking it directly to the SED between z-score distributions.

Results

Derivation of Γ from Its Lie Algebra

This section explains how the Lie group transformation

arises from its Lie algebra using the exponential map, within the context of affine space. To aid understanding, a cooking metaphor is used: the ultimate “dish” to be cooked is the Lie group transformation Γ. The Lie algebra provides the directions, the exponential map gives the recipe, the associated differential equations are the specific recipe instructions, and the final solution is the finished dish,

[

6,

8,

9,

10].

Consider again the measurement vector (3):

where

represents the true scores on measure

, and

represents the standard deviation of errors of measurement on measure

. The homogeneous coordinate - the 1 in the third row of the vector - anchors the vector in a two-dimensional affine space. A transformation group, Γ, acts on this vector to model relationships between scores on any two measures

and

from the k measures. From above, the transformation matrix

is,

This matrix transforms the measurement vector as follows,

Following Stillwell [

6], the transformation matrix

is a member of a matrix Lie group.

Affine Space Context

Affine space generalizes Euclidean space by allowing transformations such as translations and scalings, but without a fixed origin. In the current context, the homogeneous coordinates enable linear algebraic operations to represent affine transformations.

Lie Group and Lie Algebra

Using the cooking metaphor, the final “dish,” again, is the Lie group transformation acting on affine space, Γ. This represents a transformation in 2D affine space combining,

The associated Lie algebra—the “recipe” for the transformation—is:

Following Stillwell [

6], this Lie algebra matrix encodes the infinitesimal generator of the affine transformation

.

The Lie bracket, an important part of the Lie algebra [

6], is given by the matrix equation,

Following Stillwell [

6], this result shows the Lie algebra is non-commutative: the order of multiplication matters. The generators do not commute. Yet, the final term reveals a symmetry—specifically, a translation symmetry [

4].

Step-by-Step Derivation via the Matrix Exponential

To derive the full transformation—the “cooked dish”

—we compute the matrix exponential,

where the parameter

, which ranges from 0 to 1, represents the path of the transformation. At

, no transformation has occurred (the identity), and at

, the transformation is complete. Given the upper triangular structure of

, the exponential is:

This is the one-parameter subgroup generated by

, describing how the affine transformation evolves from

to

.

Differential Equations

The evolution of

satisfies the matrix differential equation [6, 8 - !0],

From this, we extract component-wise differential equations:

These equations describe how the affine transformation evolves from infinitesimal steps—the specific instructions in the recipe for “cooking”

. Solving the differential equations with initial conditions

and

, as described by Boyce & DiPrima [

11], we get,

At

, we obtain the original transformation group Γ,

Implications

A former colleague of the author’s often asked, when presented with theoretical ideas like the above,

“So what?” He inquired about the practical significance of the theoretical notions. The above symmetries imply further symmetries. One important symmetry implied is that the population standardized mean difference (SMD), a commonly used effect size in meta-analysis [

12,

13], will be invariant across any measures

and

from the

measures if and only if conditions (1) and (2) above hold for the scores from measures A and B in the two populations being compared,

and

. In other words, full measurement equivalence must hold in all subpopulations of both populations

and

; that is, the conjunction of assumptions (1) and (2) must hold in all subpopulations of

and

. While this follows from the symmetry principle, a proof follows.

First define:

a term that allows direct inclusion of reliability in subsequent derivations.

Assumptions (1) and (2) together imply,

so

and

Invariance of the Standardized Mean Difference

The standardized mean difference (SMD) based on scores from measure

is [

12,

13]:

Substituting the transformations (1) and (2),

Thus, the population SMD remains invariant across measures

and

from the k measures under the specified measurement equivalence conditions, i.e., the conjunction of assumptions (1) and (2) in both P

1 and P

2.

Invariance of Population SMD Implies Assumptions (1) and (2)

Now assume that the population SMD is invariant across scores from measures A and B,

For this equality to hold, both the numerator and denominator of the SMD must be scaled by the same factor

. That is:

which represents a uniform scaling of both numerator and denominator by

. This is a symmetry transformation [

4].

Additionally, a constant translation

may be added to both group means in the numerator,

Since

cancels out, the difference remains unchanged. Importantly, adding a constant does not affect the denominator, because the variance of a variable plus a constant equals the variance of the original variable [

7].

Therefore, for the SMD to remain invariant across transformed measures, the following conditions must hold:

Uniform scaling of true scores by γ and possible translation by :

And uniform scaling of SD of measurement error by γ:

Thus, the population SMD will be invariant across the scores from the measures if and only if the conjunction of these transformation conditions is satisfied.

Reverse Implication

Assume the population standardized mean difference

SMD(t) is invariant under a transformation flow whenever the numerator difference and the pooled standard deviation evolve with the same instantaneous multiplicative rate. The Lie algebra of the transformation matrix Γ corresponds to the special case where this rate is constant, α(t) = ln(γ), specifically:

If the transformation flow deviates from this condition—so that the numerator and denominator no longer share the same rate of change—the SMD will not remain invariant across the transformation.

The standardized mean difference at transformation parameter

is,

For simplicity, assume equal population sizes, so,

Suppose the transformation flow is governed by differential equations that differ from the Lie algebra–generated form. That is, assume:

Then the derivative of

is:

Unless both of the following conditions are satisfied,

the numerator will not cancel to zero, and therefore the population SMD will not be invariant across the measures

and

.

Effects of Breaking the Symmetry Expressed by (1) and (2)

The conjunction of conditions (1) and (2) represents a symmetry of uniform scaling of true scores and error standard deviations by γ, along with the translation symmetry of true scores by

. We now consider an important implication of the above explicated measurement model: the consequences of breaking this symmetry (1) and (2). First note that assumption (1) can be expressed as:

a special case of the more general expression:

This general expression introduces nonlinearity into the relationship between true scores. It is used in the simulation study below to examine the effects of small deviations from the symmetry, expressed by (1), on the population true-score-level SMD effect size.

For simplicity, throughout the simulation we assume

,

, and no measurement error. This allows us to focus on the true score SMD, representing the true score effect size. We begin with the assumption that the relationship between the true scores on measures

and

is:

in both populations

and

. In this case, as shown above, the population true score SMD will be the same whether based on scores from measure

or measure.

Simulation Study

Populations of true scores were created for populations

and

, each with 1,000,000 scores. The mean of

was 63.05 (

), and the mean of

was 63.04 (

). The relationship between these true scores was:

in both

and

. Next, varying degrees of lack of measurement equivalence were introduced in scores for population

by varying

in (1b) from

to

in steps of

. For example, in one simulation step the relationship between true scores in

was:

while in

it was:

The

term was not included in the simulation since it cancels out in the numerator of the SMD computation.

In each scenario across the simulations,

in

, while

varied slightly above 1.000 in

, representing a small lack of measurement equivalence. At each step, the population true score SMD comparing

and

was computed. The results are plotted in

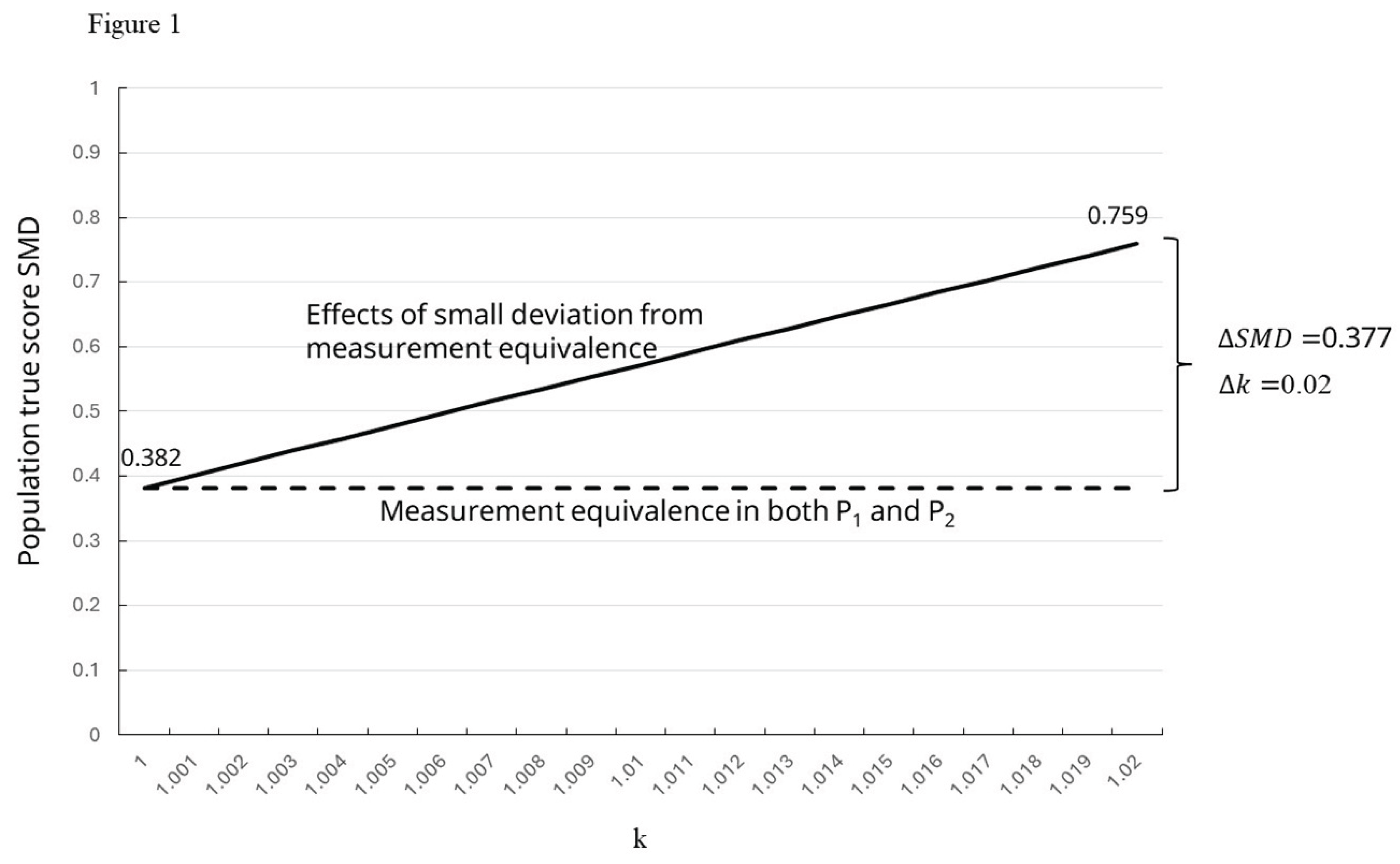

Figure 1.

In the Figure, the dashed line represents the case in which full symmetry holds, while the solid line shows how the population true score SMD changes as the deviation from symmetry increases. As shown in the figure, as the symmetry condition deviates further from perfect symmetry, the population SMD deviates further from invariance. As increases above 1.000, the population SMD deviates further from invariance.

Discussion

This paper has extended Nugent’s matrix Lie group measurement model by identifying additional symmetries and demonstrating their implications for effect size invariance in meta-analysis [

4]. Specifically, it was shown that the population true score standardized mean difference (SMD) remains invariant across different measures if and only if the transformations between those measures satisfy two key conditions:

A uniform linear scaling of true scores involving both a uniform scaling by γ and a translation, and

A uniform scaling of measurement error by γ.

These conditions define a symmetry group whose structure is captured by a Lie algebra, and whose global behavior is governed by the exponential map in affine space.

By deriving the transformation flow from the Lie algebra and solving the associated differential equations, it was shown that the SMD remains constant along this path—confirming that the invariance of the SMD effect size is not merely a statistical artifact but a geometric consequence of the measurement symmetry. Conversely, any deviation from this transformation flow results in a non-zero derivative of the SMD indicating a breakdown of invariance.

One of the symmetries identified by Nugent (2024) is the invariance of the relative ordering of scores in the true scores from measures A and B if the conjunction (1) and (2) holds for the scores on the k measures. This invariance is manifested by the true z-scores for true scores on measures A and B. It is this relative ordering that conveys information about the concept measured into data analyses. Thus, if the conjunction of (1) and (2) holds, in a sense the information contained in the z-score distribution is conserved across the k measures. This parallels Noether’s theorem which states, in general, that symmetries are associated with conserved quantities. Thus, analogously, the symmetries associated with the combination of transformations (1) and (2) are associated with conservation of information conveyed by true z-scores from the k measures. This conservation has important implications for validity.

An implication of the results concerning the invariance of the population true score SMD is that meta-analysts should consider evidence of measurement equivalence prior to assuming scores based on different measures are comparable in a meta-analysis. Lack of measurement equivalence would have implications not only in terms of direct comparability of score meaning, but also what differences in scores indicate, lack of measurement equivalence of differences in the construct inferred from the scores.

The simulation study illustrated how even infinitesimal violations of the linear symmetry condition—modeled by a nonlinear exponent k slightly deviating from 1—can lead to distortions in the population true score SMD. This finding underscores the sensitivity of effect size comparability to the underlying measurement structure and highlights the importance of verifying measurement equivalence when synthesizing results across studies.

It is also important to note that while uniform scaling of measurement error is a symmetry condition that guarantees invariance at the true score level, at the observed score level it attenuates effect sizes in a predictable manner. Specifically, observed SMDs are reduced relative to true SMDs in proportion to the reliability of the measures [

7],

This predictability is a consequence of symmetry. Thus, invariance at the latent construct level coexists with systematic attenuation at the observed level, underscoring the importance of considering measurement error when interpreting effect sizes.

These findings also have important implications for longitudinal research. Invariance under transformation flows implies that effect sizes can remain stable over time only if measurement conditions are symmetric across repeated waves. Even small deviations from symmetry can mimic or mask genuine developmental change, creating the appearance of growth or decline where none exists. This underscores the need for formal measurement equivalence testing across time points to ensure that observed changes in standardized mean differences reflect true developmental or treatment effects rather than artifacts of measurement structure.

Together, these results provide a mathematical foundation for understanding when and why effect sizes such as the SMD can be meaningfully compared across instruments and across time. They also offer a novel application of Lie group theory to psychometrics, opening new avenues for exploring symmetry, invariance, and transformation in measurement models. Similarly, in cross-cultural or cross-language research, ensuring that measurement transformations preserve symmetry is essential for meaningful comparison of effect sizes across populations.

Conclusions

At its core, this analysis is an application of the symmetry principle: the idea that symmetric structures yield symmetric outcomes. When measurement transformations, population sizes, and error variances are symmetrically aligned across groups, the population standardized mean difference remains invariant. This invariance is not coincidental—it emerges naturally from the underlying symmetries encoded in the Lie group transformation. Conversely, when these symmetries are broken, even infinitesimally, the SMD begins to deviate, revealing the sensitivity of statistical outcomes to structural asymmetries. Thus, the symmetry principle provides a unifying lens through which measurement equivalence, effect size comparability, and transformation invariance can be understood and explored. The symmetry principle also extends to measurement error: while uniform scaling preserves invariance at the true score level, it produces predictable attenuation at the observed score level, reinforcing that both invariance and attenuation are structured consequences of the same underlying symmetries.

Funding

There was no funding supporting this work.

Data Availability statement

The only data involved in this research was the two simulated populations of true scores. These are in SPSS files available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Rosen, J. (2005). The symmetry principle. Entropy, 7(4), 308-313. [CrossRef]

- Gross D. J. (1996). The role of symmetry in fundamental physics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(25), 14256–14259. [CrossRef]

- Kotoky, S. (2024). Use of symmetry in the field of mathematics and its application in various fields. International Education and Research Journal, 10(5), 45–48. http://ierj.in/journal.

- Rosen, J. (1995). Symmetry in science: An introduction to the general theory. Springer.

- Nugent, W. (2024). A Matrix Lie Group Formulation of Measurement Theory: Symmetries of Classical Measurement Theory. Measurement: Interdisciplinary research and perspectives, 22(3), 297-314. [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, J. (2008). Naïve Lie theory. Springer.

- Lord, F. M., & Novick, M. R. (1968). Statistical theories of mental test scores. Addison-Wesley.

- Falcone, G. (2017). Lie groups, differential equations, and geometry. Springer.

- Güngör, F. (2025). Lie symmetry methods for differential equations: A survey. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.01234.

- Olver, P. J. (1993). Applications of Lie groups to differential equations (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Boyce, W., & DiPrima, R. (1986). Elementary differential equations and boundary value problems (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE Publications.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).